Abstract

Professional quality of life (ProQOL) is affected by and affects professional well-being and performance. The objectives of this study are to identify risk factors of ProQOL among EM physicians in Zagazig University hospitals (ZUHs), to detect the relationship between ProQOL and coping strategies, and to measure the implication of the Worksite Wellness Education (WWE) program on improving knowledge skills, ProQOL, and coping. An intervention study was conducted among 108 EM physicians at ZUHs through two stages: assessing ProQOL subscales (CS, BO, and STS) and coping strategies and conducting the WWE program. A pre–post-test design was used in the evaluation. CS was higher among the older age group, smokers, nighttime sleepers, and hobbies’ practitioners. Coping strategies carried out by EM physicians to overcome stress and their ProQOL scores were improved significantly post program. ProQOL has multiple factors that affect it. Applying the WWE program will address this concept and may raise awareness about how to cope with work stressors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term professional quality of life (ProQOL) refers to both positive and negative emotions that an individual comes across in his/her job as a helper (Kim et al. 2015). ProQOL includes the positive emotion of compassion satisfaction (CS) and negative emotion compassion fatigue (CF). CF is composed of two parts: The first part is concerned with emotions, such as anger, exhaustion, depression, and frustration as a typical reaction of burnout (BO). Secondary traumatic stress (STS) is a negative emotion caused by fear and work-related trauma (Stamm 2010). This triad of CS, BO, and STS states the major aspects of ProQOL as it is affected by and affects professional well-being and performance (Yeela Haber et al. 2013) of workers in service industries that help distressed peoples may be affected by this (Kim et al. 2015).

Emergency care settings carry substantial psychological demands to physicians who suffer fatigue due to difficult work conditions, such as sleep deprivation, lack of the required resources, and poor support. These factors lead to irritability and health threats that could alter their QOL (Sand et al. 2016).

Stress leads to both emotional and physical pressures from which people react by carrying out activities that are inspired to reduce their stress levels. These activities are commonly known as coping strategies. Coping strategies are the specific efforts that individuals carry out to control, tolerate, ease, or minimize stressful events (Tavakoli et al. 2016). Coping is meant to moderate the relationship between environmental stressors and physiological responses which eventually affect health outcomes. Defensive coping can moderate the impact of hostile encounters on physiological functioning; hence, people with higher coping skills commonly have fewer depressive symptoms (Addison et al. 2007).

Unfortunately, medical malpractice has become a part of everyday life for working physicians. In particular, emergency medicine has been perceived as having a higher risk of malpractice due to the absence of control over patient volume, patient acuity, and limited window of interaction between patients and physicians which is caused by the absence of a well-established patient–physician relationship (Schmitz et al. 2012).

Like most developing countries, emergency medicine (EM) in Egypt is in its early development phase. Traffic accidents, which require emergency medicine, are a main cause of death in Egypt, as Egypt has one of the highest mortality rates worldwide (El Safa and El Khayat 2016). The difference in work environment at the EM departments, which could be more stressful in Egypt than in other countries, can be attributed to the deficiency of scheduled shift plans, when some of the residents in each specialty take about a month or more off for studying and exams resulting in low staff members managing the same work capacity. The high flow of patients exceeding the teamwork capacity and the lack of positive reinforcement during training, in addition to the lower physicians’ income in Egypt than that of physicians in many Western countries, lead to excessive stressful working environment among the Egyptian emergency physicians (Al-Sayed et al. 2016).

Creating a “culture of health” has been supported to promote the change of health behavior and improving people’s health (Shareck et al. 2013). This “culture of health” can be accomplished through setting-based health promotion (WHO 2011). The concept of wellness and well-being is a rising field of interest among healthcare professionals. The wellness education intervention is meant to improve the understanding of significant health behaviors (manifestations, causes, and consequences) and how employees and organizations can make efforts to improve and support a healthy lifestyle in the workplace (Blake and Gartshore 2016).

A paradigm shift is necessary to convince residents and educators that wellness is more than just “fluff” and plays a significant role in their education and future career. A primary step towards legitimizing wellness may be education on the effect of various important negative factors on EM physicians as substance abuse, sleep deprivation, circadian disruption, malpractice and fear of litigation, exposure to patient mortality, exposure to infectious disease (Schmitz et al. 2012), diet and nutrition, work-related stress, physical activity, musculoskeletal disorders, smoking and alcohol consumption, together with guidance on ways of promoting health and making lifestyle changes in the workplace setting (Blake and Gartshore 2016).

The Emergency Medical Services Department of the Ministry of Health (MOH) continues to supply Hospital Emergency departments over the country with new equipment and episodic short training programs for staff who are in charge of the care of trauma patients and cardiac life support. There is little public awareness of the fact that EM physicians’ job is the host of numerous occupational hazards particularly in developing countries such as Egypt (Montaser 2013). So, Egyptian EM physicians are in urgent need for stress management programs to prevent and alleviate these psychosocial health hazards with particular stress on the organizational role in promoting satisfaction levels (Khashaba et al. 2014).

This study was conducted to identify risk factors of ProQOL subscales among EM physicians in Zagzig University hospitals to detect the relationship between their ProQOL and coping strategies and to measure the implication of the WWE program on improving their knowledge, ProQOL, and coping strategies.

Study design and settings

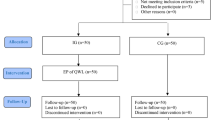

This study was conducted in two phases:

1st phase, a cross-sectional study was carried out at EM department at ZUHs, Zagazig City, Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, from April 1st to July 1st 2015.

2nd phase, an intervention study was conducted from July 1st 2015 until July 1st 2016 in the same setting.

Study population

A stratified random sample of 108 EM physicians was selected from those who were working at the EM department at the ZUHs for at least one year at the time of the study. Physicians were grouped into two strata according to their specialty “surgical & non-surgical;” then simple random sample was selected from each stratum. The sample size was calculated through Epi-Info (Epidemiological information package) software version 6.1. The total EM physicians at the ZUHs were about 236 workers, and the prevalence of BO among the EM physicians was 24.9% in a recent study carried out in Egypt (Abdo et al. 2016). So, the calculated sample size was 130; however, only 108 EM physicians accepted to participate in the current study.

Data collection

Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted during May 2015. It was carried out on 10% of the study sample (13 EM physicians) to assess the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. The reliability coefficients were generally high for all questionnaires and suitable for scientific purposes (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.78 to 0.92). All EM physicians of the pilot were excluded from the results of the study. According to the result of the pilot study, the questionnaire was assessed and some modification was done.

1st Phase

A self-administered questionnaire was introduced to the participant EM physicians through a 15-min face-to-face semi-structured interview. The questionnaire is composed of three parts as follows:

1st part: socio-demographic and occupational data, such as age, sex, marital status, specialty, current position, smoking, body mass index (BMI), history of chronic diseases, years of experience, time taken from home to work, shift work, and working hours per week.

2nd part: professional quality of life scale (ProQOL) version 5 (Stamm 2005). It is composed of three sub-scales; compassion satisfaction (CS), burnout (BO), and secondary traumatic stress (STS). The ProQOL is a 30-item self-report measure. Each subscale consists of 10 questions, with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = very often). It has been validated in several populations and shown to have high reliability and validity for assessing ProQOL. Scoring of each subcategory ranged from 5 to 50. A higher score on a subscale signifies a higher degree of the corresponding sub-factor. A score of 22 or less is considered “low,” “average” scores range from 23 to 41, and 42 or higher is considered a “high” score. Low CS will increase CF while low BO and STS will decrease it. For the purposes of the ProQOL 5 scale, each component is weighted as a third of the final score. The three components of CF can be interpreted individually and as combined.

3rd part: the coping strategies inventory (CSI) (Tobin et al. 1984): the coping strategies inventory is a self-report questionnaire that contains 72 items designed to assess coping thoughts and behaviors in response to a specific stressor. Each question is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “never,” 2 = “seldom,” 3 = “sometimes,” 4 = “often,” and 5 = “almost always”). The coping strategy inventory has 14 subscales on the CSI including eight primary scales, four secondary scales, and two tertiary scales. The focus was on the primary subscales which consist of specific coping strategies people use in response to stressful events. There are nine items in each of the primary subscales. Raw scale scores are calculated simply by adding the Likert responses of the items for a particular subscale together. These items include the following:

-

Problem solving (PS): behavioral and cognitive strategies designed to eliminate the source of stress by attempting to reach a solution for the cause.

-

Cognitive restructuring (CR): cognitive strategies that alter the meaning of the stressful transaction as it is less threatening; it is examined for its positive aspects, viewed from a new perspective, etc.

-

Social support (SS): seeking emotional support from people around, family, and friends.

-

Express emotions (EE): releasing and expressing emotions.

-

Problem avoidance (PA): denial of problems and the avoidance of thoughts or action about the stressful event.

-

Wishful thinking (WT): cognitive strategies that reflect an inability or reluctance to reframe or symbolically alter the situation. These items involve hoping and wishing that things could be better.

-

Social withdrawal (SW): blaming and criticizing oneself for the situation.

Problem solving, cognitive restructuring, social support, and expressing emotions reflect the attempts made by the individual to engage in efforts to manage the stressful person/environment transaction. Through these coping strategies, individuals engage in an active and ongoing negotiation with the stressful environment.

Problem avoidance, wishful thinking, social withdrawal, and self-criticism include strategies that are likely to result in disengaging the individual from the person/environment transaction. Emotions are not shared with others, thoughts about situations are avoided, and behaviors that might change the situation are not initiated.

2nd Phase

The worksite wellness education (WWE) program was conducted for 108 EM physician participants.

A pre-test questionnaire was introduced to the participants and contained questions evaluating the knowledge levels of the participants regarding the following: work-related stress, musculoskeletal disorders, diet and nutrition, physical activity, smoking, substance abuse, circadian disruption, sleep deprivation, malpractice and fear of litigation, exposure to infectious disease, and exposure to patient mortality.

Then, the WWE program was introduced to the participants in the form of training sessions, inside the residents’ resting room. The researches provided two educational sessions per week, one in the morning shift and the other in the night shift, for six consecutive months during different prescheduled week days to cover all the participants equally. Each session was about 30 to 45 min. Different training methods were used for illustration such as, booklets, PowerPoint presentations, posters, role play, group discussion, and video films.

The content of the WWE was designed according to previous studies and included key topic areas of work-related stress, diet and nutrition, musculoskeletal disorders, physical activity, smoking (Blake and Gartshore 2016), substance abuse, sleep deprivation, circadian disruption, malpractice and fear of litigation, exposure to patient mortality, and exposure to infectious disease (Schmitz et al. 2012),

Three months after the application of the program, a post-test questionnaire was conducted with the same questions in the pre-test one with the same participants. Moreover, the questionnaire of the ProQOL and CSI was applied for the second time. The questionnaires were filled out by the participants through a 30-min face-to-face semi-structured interview.

Statistical analysis:

The data collected was computerized and statistically analyzed using the SPSS program (Statistical Package for Social Science) version 15.0. Qualitative data were represented as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative data were represented as mean and standard deviation. Quantitative data was compared using the Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA). Correlations between variables were analyzed using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. McNemar’s test and paired t test were used to compare between pre-test and post-test results. Multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify the predictors of each indicator of ProQOL. The test results were considered significant when p value < 0.05 and highly significant when p value < 0.01.

Results

One hundred and eight ED physicians working at ZUHs were included in the current study. Most of them (64.8%) were young being the ages between 20 and 29 years old. Male physicians represent 55.6%, 71.3% of the studied emergency physicians were married, and 63.0% was nonsmokers. As regarding life style, 63.9% was not practicing exercise and 61.1% has no hobbies. Nighttime sleeper was 65.7% and 64.8% reported drinking about 1–2 cups of caffeine per day. Residents represent 47.2% of the respondents, and those of non-surgical specialties are 80.6%, and 66.7% reported that they had non-satisfactory income. Most of the participants (73.1%) serviced average 20–40 patients per shift, and 63.9% has 40–60 working hours per week. Relationship between socio-demographic and occupational variables of the studied ED physicians and their ProQOL sub-scales is demonstrated in Table 1 where, older age group (40–49 years), smokers, nighttime sleepers, and hobbies’ practitioners showed higher levels of CS (p ≤ 0.05) while BO levels were significantly higher among younger age group (20–29 years), females, non-smokers, daytime sleepers, and those who do not practice exercise or have hobbies, those with chronic diseases, those who take more than one hour to reach work, servicing average more than 40 patients per shift, on a schedule of more than three night shifts per week, and more than 60 working hours per week (p ≤ 0.05). STS was common among non-smokers, those suffering of chronic diseases, and who take more than one hour to reach work (p ≤ 0.05).

Multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors of each indicator of ProQOL. The results of the multiple linear regressions are presented in Table 2. Compassion satisfaction scores were significantly affected by having hobbies (β = 0.237, p < 0.01), which demonstrated the strongest association with compassion satisfaction. Nighttime sleep also had a significant positive relationship with compassion satisfaction (β = 0.184, p < 0.05). The results of the burnout regression demonstrated that practicing exercise has a moderate negative association with burnout (β = −0.432, p < 0.001). Similarly, nighttime sleep (β = −0.327, p < 0.001) and having hobbies (β = −0.129, p < 0.05) were associated with lower levels of burnout. An average number of patients serviced per shift (β = 0.357, p < 0.001), night shifts (β = 0.318, p < 0.001), work hours per week (β = 0.261, p < 0.01), history of chronic diseases (β = 0.174, p < 0.05), female gender (β = 0.159, p < 0.05), and time taken from home to work (β = 0.109, p < 0.05) demonstrated the strongest positive association with burnout. The results of the STS regression revealed that history of chronic diseases (β = 0.279, p < 0.01) was associated with higher levels of STS, while smoking was negatively associated with STS (β = −0.137, p < 0.05).

Coping strategies followed by ED physicians to overcome stress and their ProQOL scores were evaluated before and after application of the WWE program (Table 3). There was significant improvement in all variables of coping strategies except for wishful thinking. This improvement was highly significant regarding social support, emotional expression, and social withdrawal (p ≤ 0.001).

As regarding ProQOL scores, there were highly significant improvement in all subscales of CS, BO, and STS (p < 0.0001) after application of the program.

Table 4 demonstrated Pearson’s correlation analysis between ProQOL subscales and coping strategies. A highly significant positive correlation was found between CS and PS (r = 0.21, p ≤ 0.01), CR (r = 0.58, p ≤ 0.01), EE (r = 0.28, p ≤ 0.01), and SS (r = 0.17, p ≤ 0.01). While, there was a significant negative correlation between CS and PA (r = −0.46, p ≤ 0.01) and SC (r = −0.32, p ≤ 0.05). There was a significant positive correlation between BO and STS (r = 0.11, p ≤ 0.01), SC (r = 0.14, p ≤ 0.01), WT (r = 0.24, p ≤ 0.05), and SW (r = 0.12, p ≤ 0.05). While, a significant negative correlation was noticed between BO and PS (r = −0.61, p ≤ 0.01), SS (r = −0.17, p ≤ 0.01), CR (r = −0.26, p ≤ 0.05), and EE (r = −0.28, p ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 1 demonstrates the level of knowledge about workplace wellness before and after application of the WWE program. There were significant improvements in all items, which was highly significant with sleep deprivation, physical activity, diet, and nutrition (p < 0.001).

Discussion

The concept of wellness, quality of life, and coping with stressors is a growing area of focus and interest, particularly among EM physicians whom are routinely confronting potentially traumatic events in the course of their careers.

The current study investigated risk factors affecting aspects of ProQOL among 108 EM physicians at ZUHs where compassion satisfaction (CS) was higher among older age groups, night sleepers, and those practicing hobbies. This is may be attributed to partial relive of senior physicians from marked competition to build up their career and more satisfaction in their jobs. Rosenstein (2013) noted that older physicians are more capable and well-prepared for handling stressful situations effectively that enhance CS. Moreover, night sleep and practicing hobbies reflect a more balanced life and relief from work stressors which leads to more CS. Sabo (2011) mentioned the great effect of having hobbies and sharing time with family on increasing the level of CS.

Although smoking has many negative health impacts; however, it may represent an outlet and time off from the emergency work environment. In the current study, smokers show (CS) more than non-smokers, and this is consistent. Bhutani et al. (2012) noted that CS score was greater among older age groups and smokers who generally think that smoking alleviates their stress and gives them a chance to take some time off. On the other hand, gender and working hours did not affect CS which matches the findings of Bellolio et al. (2014) and Sreenivas et al. (2010).

The present results revealed higher BO rates among younger age groups, females, non-smokers, those with chronic diseases, and those who have no social life and suffer from stressful work conditions, e.g., high workload and night shift. Also, STS was higher among non-smokers, those with chronic diseases, and those who take more than an hour to work. Shanafelt et al. (2012) found that the highest rates of BO were among EM physicians.

Peisah et al. (2009) found that younger people are more susceptible to burnout and psychological distress. Upton et al. (2012) also concluded that the prominent factor for BO is age. Younger physicians usually have extra working hours and a large workload which are required of them so they are able to raise their income. Egypt is considered one of the countries where physicians get paid the least. When physicians went on strike in 2011, they were earning $50 a month when working in a public hospital (Ahram Online 2011). Egyptian physicians have made some ground since then but are still paid very poorly compared to physicians in the rest of the world.

Female physicians, in the current study, were more liable to BO. This may be clarified by facing workplace discrimination both from physicians and from patients. Also, female physicians may face lower incomes and fewer opportunities than the male emergency physicians. Moreover, lack of social and workplace support leads to an increase in BO and females often face less social and workplace support in fields dominated by males. Verweij et al. (2017) found that the work–family conflict is the main contributor of higher BO among females. On the other hand, Porto et al. (2014) reported no role for gender. These discordances may be related to the different cultures and workplace settings that can predict role of gender on BO levels.

Non-smokers in the present study revealed a higher BO. The same results were reached by Kotb et al. (2014). Ellahi and Mushtaq (2012) who explained that person may seek help by smoking to cope with stress. Also, work overload and lack of social life are associated with high scores of BO among studied physicians in accordance to these results. Toker et al. (2015) found higher BO rates among EM physicians with higher patients’ rate. Additionally, Wilson et al. (2017) noted that excess workload creates work-time pressure. This may include longer work shifts and shorter duration for social life. Ben-Zur and Michael (2007) found that social support mediated burnout also; there is evidence that organizational support was related to a reduction in burnout (Miller et al. 2017).

Predictors of both negative and positive aspects of ProQOL were investigated among studied EM physicians and could be summarized in two main categories: social life (hobbies, exercise, and night sleep) and work conditions (number of patients, night shift, and time to go to work). The imbalance between the two items in the present study shows increase in BO and decrease in CS. On the same line, Baird and Kracen (2006), Killian (2008), and the Registered Nurses of Ontario (2014) demonstrated that improved self-care practices (especially exercise, adequate night sleeping, rest times, and having holidays) can dramatically reduce CF and improve CS. Stressful work conditions represent the strongest predictors for BO, as they usually push individuals towards fatigue and depression which are the main symptoms of BO. Consistently, Montgomery et al. (2011) clarified that workload was one of the most studied occupational factors in relation to BO. Additionally, Jalili et al. (2013) noted that the factors that may be associated with higher BO rates were work overload, feeling of insecurity for future career, and imbalance between professional and private life.

Increasing awareness about coping strategies with different work stressors in emergency settings can help physicians to overcome these stresses and improving ProQOL subscales. There was a significant improvement in all coping strategies after intervention except for wishful thinking. That may need longer duration to be changed and root changes in different surroundings of physicians’ life (Table 3). These results are in accordance with the results of Hunziker et al. (2013), who reported significant impact of cultural and educational changes on improving coping mechanisms among emergency physicians, decrease exposure of physicians to BO, and help them to cope with their work tasks. Also, Stamm (2010) and Gentry and Baranowsky (2011) noted a decrease in the level of CF among participants after application of an education program. In a systematic review done by Cocker and Joss (2016) to determine the effect of educational programs on CF, they noted the great difference in the effect of such programs.

Table 4 demonstrated correlation analysis between ProQOL subscales and coping strategies. CS was positively associated with PS, CR, EE, and SS; however, it is negatively associated with PA and SC. On the other side, BO and STS were positively associated with SC, WT, and SW; however, BO is negatively associated with PS, SS, CR, and EE. It was clear that being a positive physician who can interact with the surrounding environment, ongoing, solve the problems and not avoiding it, restructure his thinking according to the situation (malleable), and above all of that find the social support (either from his colleagues, supervisors, and family), all of these are associated with increased CS and decreased BO and STS. In consistence, Zotti et al. (2008) found a strong link between coping styles and CF. Moreover, the American Colleague of Emergency Physicians (2016) clarified that social support (dealing with colleagues as partners) and logic problem solving were the most important determinants of BO reduction and CS increase. Additionally, Goldberg et al. (1996) noted a strong positive association between PrQol and problem solving and social support and cognitive restructuring. However, it was negatively associated with problem avoidance, social withdrawal, and continuous self-blame.

A core step on the way of physicians’ wellness is increasing their awareness about this item and drawing their attention towards the role of wellness not only on their quality of life but on the quality of the service provided to their patients. With the introduction of wellness topics early in residency, the ultimate goal is to increase resiliency and decrease BO. The benefits of cultural change include providing positive educational environment for physicians, raising awareness of CF, coping strategies with emergency departments’ ultimate requirements, and how to maintain wellness. In Fig. 1, knowledge about workplace wellness was significantly improved after the application of an educational intervention program; improvement was highly significant regarding knowledge about sleep deprivation, physical activity, and nutrition. These factors reflect on the un-healthy lifestyle of the studied physicians related to culture, work overload, and long shift hours. Mata et al. (2015) clarified that increasing awareness among EM residents about wellness can enhance rising their own wellness and serve them, their families, and their patients throughout their careers. Ruger and Scheer (2009) found that sleep disruption may cause insomnia, decreased alertness, and performance, a sense of “not feeling well.” Also, poor nutrition and lack of physical activity were the most significant factors affecting physicians’ wellness, as they lead to mood swings, poor productivity, and lifelong health problems (Wallace et al. 2009).

As regards malpractice and fear of litigation, Elmendorf (2009) identified EM physicians at a higher risk of malpractice specialty due to patient acuity, lack of control over patient volume, and limited interaction time with patients and families in a non-established patient–physician relationship. Schmitz et al. (2012) focused on the importance of residence education among EM physicians regarding following points for reduction of the effect of fear of malpractice and fear of litigation on wellness: acknowledge this risk, maintaining balance of realistic and safe patient care standards, strategies for risk management, improved documentation, and introduction to the litigation process.

In conclusion, younger age groups are more exposed to BO symptoms. On the other hand, having a hobby, regular physical activity, and good time for night sleeping can decrease the risk of CF among EM physicians. Additionally, scheduled work as decreased number of work hours per week, workload, and night shift has a dramatic effect on reduction of BO. Educational programs are targeted to increase awareness about CF; coping and work place wellness may improve these elements that subsequently enhance ProQOL. These findings are encouraging, as they suggest that workers in at-risk occupational groups can be taught to cope with the known risk factors for the development of CF.

Strengths of the study

To our knowledge, this study was one of very few studies that make a spot on ProQOL in Egypt. Moreover, it is the first study that applies a WWE program to raise awareness among EM physicians about factors that may help them to navigate stress which is an unavoidable part of their job.

Limitations

There were many other variables that were not included as risk factors, such as home support, personal coping strategies, and training program factors. The long-term effect of education program was not evaluated. Social desirability was huge, especially if in a face-to-face situation, such as an interview. The health education program took a long time and was very difficult to introduce to the EM physicians because of their busy schedule and difficulty in convincing them to admit the training. Finally, this study cannot address causality or directionality of the observed associations.

References

Abdo SA, El-Sallamy RM, El-Sherbiny AA, Kabbash IA (2016) Burnout among physicians and nursing staff working in the emergency hospital of Tanta University, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J 21(12):906–915

Addison CC, Campbell-Jenkins BW, Sarpong DF, Kibler J, Singh M, Dubbert P, Wilson G, Payne T, Taylor H (2007) Psychometric evaluation of a coping strategies inventory short-form (CSI-SF) in the Jackson heart study cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health 4(4):289–295. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph200704040004

Ahram Online (2011): http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/21254/Egypt/Politics-/Egypt-doctors-continue-strike-over-minimum-wage-.aspx.

Al-Sayed N, Elsheikh M, Mahmoud M et al (2016) Work stress: psychological impact and correlates in a sample of Egyptian medical residents. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 23(3):113–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.XME.0000484346.57567.72

American Colleague of Emergency Physicians (2016): Avoid burnout by managing your stress. Available from www.acep.org.

Baird K, Kracen AC (2006) Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: a research synthesis. Couns Psychol Q 19(2):181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070600811899

Bellolio MF, Cabrera D, Sadosty AT, Hess EP, Campbell RL, Lohse CM, Sunga KL (2014) Compassion fatigue is similar in emergency medicine residents compared to other medical and surgical specialties. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 15(6):629–635. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2014.5.21624

Ben-Zur H, Michael K (2007) Risk-taking among adolescents: associations with social and affective factors. J Adolesc 30:17–31

Bhutani J, Bhutani S, Balhara YPS, Kalra S (2012) Compassion fatigue and burnout amongst clinicians: a medical exploratory study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 34(4):332–337. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.108206

Blake H, Gartshore E (2016) Workplace wellness using online learning tools in a healthcare setting. Nurse Educ Pract 20:70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.07.001

Cocker F, Joss N (2016) Compassion fatigue among healthcare, emergency and community service workers: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(6):618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060618

El Safa EIA, El Khayat GA (2016) A mobile solution for fast and accurate medical emergency reporting. In: 2016 I.E. First International Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies (CHASE). IEEE, pp 7–12

Ellahi A, Mushtaq R (2012) Doctors at risk of job burnout, diminishing performance and smoking habits. A Journal of the BSA MedSoc Group 6(36)

Elmendorf DW (Congressional Budget Office) (2009). Background paper. Washington DC: Congressional Budget Office, US Congress); 2009 Oct. (Congressional budget office). Medical Malpractice Tort Limits and Health Care Spending. CBO Background Paper. April

Gentry J, Baranowsky A (2011) Treatment manual for accelerated recovery from compassion fatigue. Toronto, ON, Canada, Psych Ink Resources

Goldberg R, Boss RW, Chan L, Goldberg J, Mallon WK, Moradzadeh D, Goodman EA, McConkie ML (1996) Burnout and its correlates in emergency physicians: four years’ experience with a wellness booth. Acad Emerg Med 3(12):1156–1164. Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03379.x

Hunziker S, Simona PS, Fasler K et al (2013) Impact of a stress coping strategy on perceived stress levels and performance during a simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Emergency Medicine 201313:8

Jalili M, Sadeghipour Roodsari G, Bassir Nia A (2013) Burnout and associated factors among Iranian emergency medicine practitioners. Iranian Journal of Public Health 42(9):1034–1042

Khashaba EO, El-Sherif MAF, Ibrahim AA-W, Neatmatallah MA (2014) Work-related psychosocial hazards among emergency medical responders (EMRs) in Mansoura City. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine 39(2):103–110 https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.132733

Killian KD (2008) Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Journal of Traumotology 14(2):32–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608319083

Kim K, Han Y, Kwak Y, Kim J (2015) Professional quality of life and clinical competencies among Korean nurses. Asian Nursing Research 9(3):200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2015.03.002

Kotb AA, Mohamed KA-E, Kamel MH, Ismail MAR, Abdulmajeed AA (2014) Comparison of burnout pattern between hospital physicians and family physicians working in Suez Canal university hospitals. The Pan African Medical Journal 18:164. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.18.164.3355

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job Burnout. AnnuRev Psychol 52(1):397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Narinder B et al (2015) Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 314(22):2373–2383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

Miller A, Unruh L, Zhang N, Liu A, Wharton T (2017) Professional quality of life of Florida emergency dispatchers. International Journal of Emergency Services 6(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJES-01-2017-0001

Montaser T (2013) Emergency medicine in Egypt: current situation and future prospects. African Journal of Emergency Medicine 3:20–21

Montgomery A, Panagopoulou E, Kehoe I, Valkanos E (2011) Connecting organisational culture and quality of care in the hospital: is job burnout the missing link? J Health Organ Manag 25(1):108–123

Peisah C, Latif E, Wilhelm K, Williams B (2009) Secrets to psychological success: why older doctors might have lower psychological distress and burnout than younger doctors. Aging Ment Health 13(2):300–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802459831

Porto GG, Carneiro SC, Vasconcelos BC, Nascimento MM, Leal JLF (2014) Burnout syndrome in oral and maxillofacial surgeons: a critical analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 43(7):894–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2013.10.025

Registered Nurses’ of Ontario (2014). Managing and mitigating fatigue: tips and tools for nurses. Available from, www.RNAO.ca/bpg/fatigue

Rosenstein AH (2013) Addressing physician stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue: the time has come. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 2(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-4015-2-32

Rüger M, Scheer FAJL (2009) Effects of circadian disruption on cardiometabolic system. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 10(4):245–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-009-9122-8

Sabo B (2011) Reflecting on the concept of compassion fatigue. Online J Issues Nurs 16(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01Man01.

Sand M, Hessam S, Bechara FG, Sand D, Vorstius C, Bromba M, Stockfleth E, Shiue I (2016) A pilot study of quality of life in German prehospital emergency care physicians. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences: the Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences 21

Schmitz GR, Clark M, Heron S, Sanson T, Kuhn G, Coomes J (2012) Strategies for coping with stress in emergency medicine: early education is vital. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 5(1):64–69. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.93117

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L (2012) Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among us physicians relative to the general us population. Arch Intern Med 172(18):1377–1385

Shareck M, Frohlich K, Poland B (2013) Reducing social inequities in health through settings-related interventions—a conceptual framework. Glob Health Promot 20(2):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975913486686

Sreenivas R, Wiechmann W, Anderson CL, Chakravarthy B and Menchine M (2010). Compassion satisfaction and fatigue in emergency physicians. University of California at Irvine, Orange, CA; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. 2010. Annals of emergency medicine. 56(3): S51.

Stamm BH (2005) The ProQOL manual: the professional quality of life scale: compassion satisfaction, burnout & compassion fatigue/secondary trauma scales. Sidran, Baltimore, MD Available from: http://www.proqol.org

Stamm BH (2010) The concise ProQOL manual, 2nd edn. ProQOL.org, Pocatello, ID

Tavakoli Z, Montazeri A, Farshad AA, Lotfi Z, Hassim IN (2016) Sources of stress and coping strategies among Iranian physicians. Global Journal of Health Science. May 18 9(1):120

Tobin RL, Holroyd KA, Reynolds RV (1984). Users manual for the coping strategies inventory. Available from K. A. Holroyd, Ph.D., Dept. of Psychology, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, 45701.

Toker İ, Ayrık C, Bozkurt S (2015) Factors affecting burnout and job satisfaction in Turkish emergency medicine residents. Emerg Med Open J 1(3):64–71. https://doi.org/10.17140/EMOJ-1-111

Upton D, Mason V, Doran B, Solowiej K, Shiralkar U, Shiralkar S (2012) The experience of burnout across different surgical specialties in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional survey. Surgery 151(4):493–501

Verweij H, van der Heijden FMMA, van Hooff MLM, Prins JT, Lagro-Janssen ALM, van Ravesteijn H, Speckens AEM (2017) The contribution of work characteristics, home characteristics and gender to burnout in medical residents. Adv Health Sci Educ 22(4):803–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9710-9

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA (2009) Physician wellness: a missing quality indictor. Lancet 374(9702):1714–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0

Wilson W, Raj JP, Narayan G, Ghiya M, Murty S, Joseph B (2017) Quantifying burnout among emergency medicine professionals. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 10(4):199–204. https://doi.org/10.4103/JETS.JETS_36_17. https://doi.org/10.4103/JETS.JETS_36_17

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2011) Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. WHO, Geneva

Yeela Haber MA, Palgi Y, Hamama-Raz Y, Shrira A, Ben-Ezra M (2013) Predictors of professional quality of life among physicians in a conflict setting: the role of risk and protective factors. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 50(2):174–181

Zotti A, Omarini G, Ragazzoni P (2008) Can the type of organisational structure affect individual well-being in health and social welfare occupations? G Ital Med Lav Ergon 30:A44

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all physicians for being included in the study.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Philippe Garrigues

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

El-Shafei, D.A., Abdelsalam, A.E., Hammam, R.A.M. et al. Professional quality of life, wellness education, and coping strategies among emergency physicians. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25, 9040–9050 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1240-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1240-y