Abstract

Research on leader–member exchange (LMX) has gained momentum with a large number of studies investigating its impact on multiple levels. This article systematically reviews the literature between 2010 and 2016 on the link between LMX and its impacts on employee perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Our review identifies performance, job satisfaction, organization citizenship behavior, turnover intention, creativity, organizational commitment and affective commitment as the most significant outcomes of LMX. This article also identifies potential areas for future LMX research and identifies different ways for enhancing its theoretical and empirical contributions in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As leadership does not occur in ‘black box’, the relationship between leaders and ‘the led’ is important and remains of interest to both academicians and practitioners (Redeker et al. 2014; Van Vugt and De Cremer 2003). Seeking to theorize this, leader–Member Exchange (LMX) is influential (Boer et al. 2016). LMX suggests a focus on the leader–employee relationship and how the intensity of their relationship leads to a number of positive and negative changes in employees over time (Liden et al. 2006). On the other hand, leaders formulate high quality relationships with some group members and facilitate them by going beyond formal obligations by offering mentoring or empowering them, while offering fewer incentives to others. Those differences in relationships are known as LMX differentiation (Chen et al. 2007; Sparrowe and Liden 2005).

LMX is an important concept in the literature, as it recognizes the importance of relationships and employee mental adjustment rather than just focusing on monetary incentives (Bernerth et al. 2016; Breevaart et al. 2015). The concept of LMX particularly focuses on those qualitative aspects that are essential for individual performance through an impact of their relationship with leaders (Liden et al. 1997; Little et al. 2016) and hence adds value to the literature. A growing number of articles have been written on LMX and its significance over the last two decades (Bernerth et al. 2016; Cobb and Lau 2015; Li et al. 2016) based on the antecedents, consequences and other aspects of LMX (Harris et al. 2014), for example, on employee performance and productivity (Boer et al. 2016; Morganson et al. 2016). Previously, researchers were focused on understanding LMX behavioral outcomes, e.g. on citizenship behavior, impression management (Wayne and Green 1993). However, researchers are now focused more on psychological outcomes (Chen et al. 2012; Creary et al. 2015; Glaso and Einarsen 2008; Liang 2017; Spitzmuller and andIlies 2010).

Most LMX studies have examined the positive consequences of LMX differentiation. However, LMX differentiation leads to variability in relationships of subordinates with leaders, resulting in a number of perceptual barriers for employees that may negatively impact on their performance (Tse and Troth 2013). Researchers are increasingly interested in determining how LMX impacts on employee behavior or perceptions negatively, such as how LMX may lead to envy or jealousy between employees working within the same groups (Kim et al. 2013).

LMX is not only associated with employee performance outcomes but also positive emotions and perceptions of employees e.g. justice procedures (van Knippenberg and De Cremer 2008), thus improving the overall environment of organizations (Ma and and Qu 2010; Peng and Lin 2016; Soane et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2010). The external environment may also play an essential role in impacting LMX quality (Bernerth et al. 2016; Nolzen 2018). The concept of LMX is strongly related to social identity theory as well (Liu et al. 2013). Social identity theory also remained an important concept, as leaders and employees may experience identity changes after working with each other (Hogg et al. 2012; Meyer et al. 2016). When employees formulate individual relationships with leaders, formulation of in-groups and out-groups leads to formulation of different social groups, eventually impacts identity changes in them over time, and hence LMX may play an initiating role in this aspect, particularly in a cross-cultural environment (Meyer et al. 2016). LMX is further related to social learning theory as high quality relationships between leaders and followers improve the learning of leaders and followers through their interactions (Uhl-Bien 2011). Furthermore, such relationships also impact on the social exchange between them, as suggested by social exchange theory (Ahmed et al. 2013); hence LMX provides a useful linkage to other theories as well.

In the early articles in the late 1970s researchers investigated LMX outcomes at the dyadic level only (Li et al. 2016). However, this does not provide complete assessments (Tu and Lu 2016). For example, employees performing tasks as a group or team are missed by such dyadic analysis (Bhal and Dadhich 2011). Thus, researchers began conducting studies at the team level (Li et al. 2016; Ma and and Qu 2010; Meyer et al. 2016; Zhao 2015). Some researchers also suggested understanding LMX consequences at group level (Cobb and Lau 2015).

Although a few researchers have recently worked on LMX review articles, most of these were predominantly based on the use of a meta-analytic approach (Dulebohn et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2016). While this provides a useful approach for summarizing results, it is based on the use of statistical techniques and may not consider the impact of contextual or subjective factors (Walker et al. 2008), Hence, the aim of our article is to expand our understanding to the above question, i.e. how does LMX impact on employees through focusing on employee perspectives and contextual differences. For this purpose LMX articles written over a seven year period (January 2010–December 2016) were examined through a systematic review process. A number of review articles written before 2010 were limited to meta-analysis (Kuoppala et al. 2008); hence this time period (2010–2016) has been selected for understanding more recent trends in the studies.

1.1 Research question

Recent studies in organizational behavior particularly suggest understanding the various outcomes of leaders’ on followers in a changing dynamics context (Liang 2017; Naseer et al. 2016). Hence, the following question provides the basis of our research: “What is the relationship between LMX and employee outcomes?”

2 Methodology

We integrate previous findings through a systematic analysis of the LMX literature. This is useful since it helps in-depth study of a particular area and helps minimize bias and enhance transparency by providing clear boundaries at every stage (Rousseau et al. 2008; Tranfield et al. 2003). One potential argument made in recent studies is that LMX is dependent on multiple factors and we cannot synthesize outcomes in one review without considering or controlling all those factors (Antonakis 2017; Ioannidis 2016). More contemporary studies try to carry out some kind of experiment for ensuring this aspect and for eliminating possible endogeneity (Bettis et al. 2014; Guide and Ketokivi 2015; Reeb et al. 2012), However, the articles included in our review period did not discuss this factor.

A second, limitation is that our focus is mainly on understanding LMX outcomes. However, we do not include the mechanism or process of those changes as most of the previous meta-analyses focused on understanding those mechanisms (Dulebohn et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2016). Hence our review aims to add value with qualitative aspects.

A three stage procedure of systematic review was followed: Stage 1 was the planning phase: research questions were defined as this clarified our overall boundaries. Stage 2 was the review phase: relevant papers from multiple sources were collected and reviewed. Stage 3 was the reporting phase: based on the reviews we reported the results and patterns of findings. There were seven steps overall in the three stages. Table 1 overview this systematic review process and explains the integration of the systematic review process at different stages.

Three different databases—Emerald, JSTOR and Springer link—were selected for a wide coverage. Second, these databases were searched for LMX papers focused on employee outcomes. Key search words were “Leader Member Exchange” and “LMX”. To focus only on more recent findings, we limited our time period to January 2010–December 2016.

In recent years a focus has mainly shifted to the ‘quality of methodological validity’ of systematic reviews. Hence, our systematic review was conducted using a logical process for enhancing inter-rater reliability as well. In order to enhance the internal validity of the study and limit bias, three different key databases were selected because they covered articles from diverse and multiple domains. Within this group only impact factor articles were selected for three reasons. First, our initial screening process resulted in identification of a large number of articles from various domains, we wanted to retain specific and high quality articles, and hence access all the high quality articles through this filter. Second, it provides a more objective ground for selection of articles above a certain quality (Citrome 2007). Third, it helps in improving the overall quality of a systematic review for future research, as potential researchers approach systematic reviews for accessing high quality content (Triaridis and Kyrgidis 2010).

In order to maintain consistency and reduce the chances of error in the article selection process, we involved one Human Resource (HR) expert, having extensive research experience in LMX and related areas, to help ensure great consistency (Cooper et al. 2018). This helped in including all the relevant key terms and hence in identifying articles that were relevant to the research question.

In total, 193 articles were included in our initial sample and keywords were searched in the ‘Abstract’ section. After reading their abstracts, 80 articles were selected on the basis of relevance to our research question. Databases do not offer an option of extracting impact factor articles. Hence the impact factor criteria were specified after getting a complete list of all the 80 articles on LMX. Paper selection was further refined by using only articles in impact factor journals to maintain a quality of research threshold, leaving 50 articles. To add more value to our study we then went through five high quality journals in other databases (e.g. Sage publications): The Leadership Quarterly, Journal of Management, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. Four of these journals are part of the FT50 list and while The Leadership Quarterly was not, it has a high impact factor. These journals were particularly relevant due to their contribution to the field of leadership. Search terms used for electronic search of databases and individual journals were the same i.e. ‘LMX’ and ‘Leader Member Exchange’. One of the reasons behind getting a large number of articles from individual journals i.e. 35 is the close relevance of these journals with the concept of leadership; hence a large number of articles were extracted from them using the similar keywords. Hence the total number of papers in the final review process was 85 (50 + 35). Details regarding selection from the databases and the number from each journal are given in Tables 2 and 3.

3 Findings

3.1 Theoretical support in the literature

A number of different theories were utilized in the articles, besides LXM theory. However, Resource Theory and Fairness Theory were the two major theories as both provide a meaningful framework for understanding the concept of LMX from diverse perspectives. Hence these are discussed in this section.

3.1.1 Resource theory

This has been used for explaining the positive association of high quality LMX and creative performance in 8% (7) articles. The relationship between LMX differentiation and team conflicts may be explained in light of resources (Zhao 2015). One paper utilized three different theoretical perspectives for theorizing team member exchange (TMX) as an important mechanism influenced by LMX (Tse 2014). Employees are more likely to engage in their work to their fullest extent when they are provided with superior resources by leaders (Breevaart et al. 2015). Conservation of Resource Theory asserts the importance of resources in employee performance. Commitment level decreases when employees are not provided with sufficient resources (Cheng et al. 2012). High quality LMX also facilitates the creation of new and valuable resources for organizations (Creary et al. 2015; Harris et al. 2011), as provision of resources makes them feel valuable and psychologically connected to an organization.

3.1.2 Fairness theory

This explains the importance of employee fair treatment and how perceptions about fairness can lead to positive outcomes in organizations in 4% (3) articles. Employee perceptions of fairness about resource distribution also impact on the quality of LMX (Sun et al. 2013). Employee perceptions regarding fairness have positive association with performance as compared to actual processes (Peng and Lin 2016). Hence, organizations should enhance transparency in their systems to create a fair climate for employees (Lind and Tyler 1988). More research on their integration may lead to meaningful outcomes in the future.

4 Analytic framework

Based on the findings regarding the outcomes of LMX, three major categories of LMX outcomes including perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral outcomes, were identified. Perceptual outcomes refer to the changes or impact on an individual’s thought process and mindset. Attitudinal outcomes refer to changes in an individual’s feeling and emotions. Behavioral outcomes refers to changes in an individual’s way of acting and habits (Fazio and Williams 1986).

Due to the blurred boundaries and lack of consensus in the literature, perceptual and attitudinal variables were categorized together (Liden et al. 1997), hence category one concerns perceptual and attitudinal outcomes, while category two concerns behavioral outcomes. Perceptual and attitudinal outcomes of LMX are psychological in nature and reflect employee mental state and how that shapes their emotions and thinking process; hence are not easily observable and recognizable to others. These outcomes also impact individuals’ behavioral outcomes. The four variables included in the first category are: Job satisfaction, Turnover intention, Organizational commitment and Affective commitment. The remaining three variables, Performance, Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and Creativity, were categorized as behavioral outcomes. Behavioral outcomes refer to the impact on the behavior of employees and changes in their actions due to LMX.

The seven outcomes were discussed in 60% (51) of papers. A few variables, including actual turnover, employee exhaustion, trust and deviant behavior, emotional exhaustion were discussed in just one or two articles. The variables of knowledge sharing, whistle blowing, perception of career satisfaction and normative commitment were investigated in just one article. A list of 7 outcomes identified from the literature and the frequency of their discussion has been summarized in Table 4.

4.1 Perceptual and attitudinal outcomes

This section discusses and integrates the findings of the four perceptual and attitudinal outcomes: Job satisfaction, Turnover intention, Organizational commitment and Affective commitment.

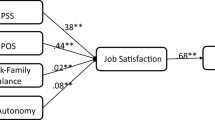

4.1.1 Job satisfaction

This was investigated as a LMX outcome in 16% (14) of papers. Most 85% (12) of these were based on empirical investigations. Job satisfaction is closely linked with employee emotions (Bang 2015; Harris et al. 2011; Pan and Lin 2016). If employee emotional abilities are strong enough in handling different and difficult kinds of situations, their relationship with leaders will be stable and level of job satisfaction will increase (Chen et al. 2014; Pan and Lin 2016). Emotional stability is helpful, as this helps them in communicating their challenges with the leaders and provide an important route for shaping high quality LMX (Jordan and Troth 2011; Hill et al. 2014; Zhang and Morand 2014). Job satisfaction is also suggested as positively related to a number of other outcomes e.g. affect, loyalty, respect and contribution (Bang 2015; Little et al. 2016). LMX partially mediates the relationship between delegation and job satisfaction (Joiner and Leveson 2015). One paper suggested a strong role for high quality LMX, especially for newcomers, since leaders are the main source of guidance and learning for them (Sluss and Thompson 2012).

4.1.2 Turnover intention

The relationship between LMX and turnover intention was examined in 11% (10) of papers. Some 80% (8) of these articles did not take into account actual turnover. Turnover intention is a better variable than actual turnover since it can highlight a realistic picture of organizations in terms of employee thinking and perceptions, while actual turnover may be linked to many broader issues as well (Kang et al. 2011). LMX facilitates relationship development between leader and follower through establishing an emotional understanding that further reduces employee turnover intention (Agarwal et al. 2012). Employees with high emotional intelligence (Poon and Rowley 2007) are less likely to think about leaving the organization due to better relationships with employers (Jordan and Troth 2011). Furthermore, when there is a similarity between personality traits of leaders and followers, i.e. high leader–follower congruence, LMX positively impacts relationship development between them through information sharing and continuous communication (Chen et al. 2016). High quality LMX between leaders and followers leads to organizational identification of employees and makes them feel closely associated to organizations (Liu et al. 2013).

4.1.3 Organizational commitment and affective commitment (subset)

LMX impacts on organizational and affective commitment was examined in 11% (10) of papers. Organizational commitment was studied in 7% (6) papers, while affective commitment was studied in 5% (4) papers. Organizational commitment refers to an individuals’ mental and emotional affiliation, while affective commitment only represents emotional. Affective commitment is a subset of organizational commitment but has been studied separately. A positive association with organizational commitment was found 80% (8 out of 10) of papers. One paper explained LMX’s role in impacting on organizational, but not career, commitment (Kang et al. 2011).

Each employee has a different relationship with supervisors and those that experience high quality LMX with supervisors experience higher levels of organizational commitment as compared to employees with low quality LMX (Torka et al. 2010). Emotionally intelligent employees respond to organizational challenges in a more proactive way and are more committed, as their broad horizon facilitates them in understanding the critical situations well (Cheng et al. 2012).

Affective commitment is linked to employee emotional bonding with organizations. The relationship between LMX and affective commitment is also mediated by participation quality (Torka et al. 2010; Zhang and Morand 2014). LMX plays a key role in facilitating employee performance by raising their level of affective commitment (Graves and Luciano 2013). When employees perceive politics in an organization, they can handle that effectively through high quality LMX and feel a sense of high connectedness (Kimura 2013). Some 40% (4) of this group of articles supported previous findings that high LMX leads to emotional attachment of employees with organizations.

4.2 Behavioral outcomes

More than 36% (31) of papers supported a positive association between LMX and performance, creativity and OCB.

4.2.1 Performance

Performance outcomes were discussed in 16 articles. Most 68% (11) of this group of articles explained performance outcomes at the dyadic level (Herman et al. 2012). More recent research examined LMX outcomes on groups. LMX differentiation is especially coherent with the concept of group/team perceptions because group perceptions are shaped by the perceptions of all the members and their individual relationships with leaders, which may lead to conflict within teams (Tse 2014; Walumbwa et al. 2011; Yuan et al. 2016). Individual performance is positively related with high LMX. However, in group/team performance both high and low LMX may lead to negative employee performance (Casimir et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2016). These performance differences at individual and team level performance may be attributing to the role of additional factors such as perceptions of competition among team employees, that may hinder perform of some employees. High LMX of some team members may increase insecurities among other team members leading to their poor performance. Resourceful environment also facilitates employee performance since employees are provided with better resources in high quality LMX resulting in better performance (Breevaart et al. 2015; Stoffers et al. 2014). LMX is strengthened by employee trust level and perceptions. Thus, employee perceptions also manipulate their performance (Bai et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2016; Naidoo et al. 2011).

4.2.2 OCB

Some 13% (11) of the articles considered OCB as one of the most important outcomes. When supervisors share resources and feedback employees feel valued and engage in OCB (Chan and Mak 2012). OCB strengthens employee bonding with the organization and reduces the intensity of deviant behavior (Sun et al. 2013). LMX also mediates the relationship between justice and OCB, as organization’s environment based on fair mechanisms, helps employees in maintaining high quality LMX. Contradicting previous studies, the relationship between LMX and personality similarity was found to be negative in one paper (Peng and Lin 2016). When leaders and followers have different personality types, employees make a better connection with their leaders, which engages leaders in OCB (Oren et al. 2012). Leader personality also impacted on LMX. If leaders have qualities like empathy and humility, that can lead to positive and high quality LMX (Newman et al. 2015). High quality LMX enhances the whistle blowing behavior of employees over time (Bhal and Dadhich 2011). LMX mediates the relationship between benevolent leadership and OCB (Chan and Mak 2012). If employers manage the negative emotions of employees and help them in managing their stress, that can lead to their job satisfaction and OCB through LMX (Fisk and Friesen 2012; Little et al. 2016).

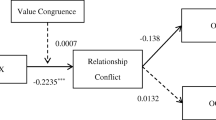

4.2.3 Creativity

Creativity is considered as one of the most essential indicators of success in organizations and facilitates creative behavior through psychological empowerment (Gu et al. 2015). Social Cognitive Theory explains the mechanism of the creative process in individuals (Volmer et al. 2012). Creativity is influenced by LMX through task motivation (Wang and Wang 2016; Zhao 2015). Creative behavior is dependent on the way supervisors treat and facilitate employees (Agarwal et al. 2012). Supervisors need to be careful as different LMX with some employees may lead to their poor performance (Munoz-Doyague and Nieto 2012). Sometimes creativity and performance may decline as a result of LMX differentiation due to conflicts between team members (Liao et al. 2010). High LMX leads to creative performance when leaders are benevolent (Agarwal et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2016a). High quality LMX leads to overall improved behavior of employees and they start valuing change oriented behaviors (Lin et al. 2016b). Creativity is triggered by high quality LMX due to the encouragement and support of leaders (Huang et al. 2016; Zhao 2015).

4.3 Summary: LMX’s perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral outcomes

We have discussed seven perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral LMX outcomes. Some 13% (11) articles theoretically examined LMX but more than 80% (69) relied dominantly on empirical investigations, which have led to a development of consistent findings in LMX literature, rather than specifying new directions.

Studies signified an overall positive association between LMX outcomes of job satisfaction, performance and OCB (Breevaart et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2014). Interestingly, 2.3% i.e. two papers investigated LMX impact on perceptual outcomes of employee trust and the results suggests focusing on some new dimensions (Xiaqi et al. 2012). Different types of leadership styles, including benevolent, despotic and servant, have also been studied in LMX (Lin et al. 2016a). Studies in these domains raise suggestions regarding importance of some new areas as well.

Just a few 3.5% (3) articles also highlight the importance of leader perceptions. Supervisors impact not only on the behavior of subordinates, but also on perceptions as well as attitudes (Pan and Lin 2016). For example, literature suggests that leader’s individual values and beliefs cannot be ignored since these play a major role in deciding an impact on leadership styles and their attitude towards employees (Fu et al. 2010). High quality LMX does not depend solely on the efforts of leaders and followers. Rather, contextual factors such as organizational climate and flexibility play a key role in shaping their relationship (Shapiro et al. 2016). LMX can be enhanced by improving the physical atmosphere and creating a kind of environment where employees can enjoy their tasks (Gkorezis et al. 2014; Zhang and Morand 2014).

A large majority, some 80% (68) of articles found a positive effect of LMX on employee outcomes while 20% (17) were different and gave inconsistent results, which suggests a dominant focus of researchers on positive outcomes of LMX and a weak focus on the negative outcomes. Indeed, researchers have started to examine the negative consequences of LMX on employees. Literature suggests that despotic leaders are dictatorial in nature and try to control employees through an autocratic leadership style; hence they are likely to negatively affect employee performance due to low LMX (Naseer et al. 2016). Similarly, abusive supervision may lead to low confidence of employees in high LMX and lead to the emotional exhaustion of employees (Xu et al. 2015). Table 5 lists citations for all the seven outcomes of LMX in reverse chronological order under each sub-heading.

Table 6 summarizes the results from our systematic review, along with the overall support for findings in the literature. This table is useful for understanding the dominance of literature towards the positive outcomes of LMX; hence it may be useful for future researchers in exploring less examined areas.

4.4 Extensions of LMX

The review of the LMX articles indicated new avenues of research for future researchers. These are an opportunity to develop new theories in future. This section discusses some examples providing new directions for future research. In this section suggestions regarding the theoretical contributions are illustrated, followed by contextual research directions.

4.4.1 Team performance and TMX differentiation

First area for future research is identified as team-level outcomes i.e. TMX. A very few 6% (5) articles suggested that LMX can be examined only at the dyadic level (Markham et al. 2010). Yet, such investigations are not sufficient for understanding group level scenarios (Joiner and Leveson 2015). Hence research at the group level can provide a better understanding of LMX (Tu and Lu 2016). LMX differentiation and team performance are positively related to each other. However, there may be conflict between team members due to LMX differentiation (Naidoo et al. 2011). Group focused leadership helps in resolving issues since leaders maintain relationships with groups rather than individuals (Herman et al. 2012). Results have supported the importance of group focused leadership in enhancing employee performance (Wu et al. 2010). LMX may lead to poor employee performance when TMX is higher (Harris et al. 2014). The relationship between LMX and team outcomes cannot be determined without taking into account contextual details. Contextual variables such as culture, personality traits and organizational structure may alter the impact of LMX on team performance (Le Blanc and Gonzalez-Roma 2012). Hence, future studies may focus on the concepts of TMX and TMX differentiation as studying LMX in isolation does not provide valid results for team performance (Yuan et al. 2016). TMX differentiation refers to the degree to which the relationship of members varies within a single group (Little et al. 2016) and was studied in 6% (5) articles. Even in one team, all members cannot maintain the same quality of relationship with each other due to personality differences as well as upbringing (Liao et al. 2010). Furthermore, working in a single team requires all the members to work together, as bonding and coordination among team members positively impact their performance as well as that of other groups (Le Blanc and Gonzalez-Roma 2012). TMX explains the strength of the relationship of team members working in one group. TMX has been linked and integrated team performance and LMX (Tse and H. 2014).

4.4.2 Social LMX and economic LMX

The concepts of social and economic LMX have been introduced and investigated in 4% (3) articles. Social LMX refers to the development of long term relationships between leaders and followers and focuses on how well they emotionally and mentally understand and support each other (Walumbwa et al. 2011). On the other hand, economic LMX refers to the short term and formal relationships between leaders and followers as both confine them to work-related discussions only. Expectations of both parties are related to performance and not perceptions or attitude in economic LMX. The main concern is goals accomplishment for leaders in economic exchanges (Kuvaas et al. 2012). Research has given more weight to social LMX as compared to economic LMX in determining employee performance as social LMX focuses on emotions and thinking of employees along with work (Herman et al. 2012); hence provides a comprehensive approach for understanding employees’ mindset.

4.4.3 I-deals

A few 6% (5) articles linked I-deals with LMX. I-deals refer to the consensus among employers and employees regarding the work conditions that lead to benefits for employees as well as employers (Luu and Rowley 2015; TrongLuu et al. 2016). They are objective in nature and vary according to the willingness of employees and employers. For example, employees may demand flexible working hours for giving their best in projects (Rousseau 2005). Articles show that it is not possible for leaders to maintain the same quality of LMX with each employee. Hence, I-deals can be used as a possible substitute for LMX and solutions to this problem. The focus of I-deals is not just on LMX quality. Rather, I-deals go beyond that in facilitating employees (Anand et al. 2010). The creation of I-deals is dependent on an organization’s culture, structure and level of flexibility. I-deal creation depends on the quality of relationships with leaders as well and how employers value their employees (Hornung et al. 2010). Future studies may integrate the concepts of LMX and I-deals for understanding how such deals get influenced by LMX differentiation for various employees and how do such deals impact on leader and follower performance over time.

4.4.4 Chinese context and Guanxi networks

An unexpected finding was the importance of China as a research context and its generation of new concepts. More than 60% (50) articles concerned China, indicating an interest in Chinese leadership due to a number of reasons. First, China’s growing importance and economy. It seems interest will continue with the huge investments in recent years in international projects, such as the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative (Ahmed et al. 2017). Initiation of these projects has led to the movement of Chinese people to different countries as workers and expatriates. Second, Chinese employers prefer working at higher management and leadership positions in other countries (Zhang and Fan 2014); hence researchers are increasingly interested in understanding the impact of Chinese employers in a cross-cultural cultural context. Finally, Chinese culture, values, work practices and management and leadership style are considered different, with preferences for working in their traditional ways even in cross-cultural settings (Chuang et al. 2015). One such example is “Guanxi”, which manifests itself in the form of increased emphasis on relationship building (Farh et al. 1998). Hence articles were interested in understanding the impact of Chinese culture on leadership in different contexts.

Most 70% (35) of the articles in this sub-group linked Guanxi with LMX. The concept of Guanxi is based on Chinese values (Wang and Rowley 2016). Guanxi networks are based on informal relationships between supervisor and employees rather than formal relationships (Wei et al. 2010). Guanxi relationships are based on emotional attachment between leaders and followers where both are engaged in informal and frequent communication with each other (Kang et al. 2011). Supervisors do not exercise their authority for getting work done by employees but rely on social bonds for establishing relationships. Guanxi leads to employee performance since that relationship is based on trust, cooperation, resource sharing, understanding and helping attitudes. Employers can maximize employee performance by forming Guanxi networks, especially in countries where collectivism is high and bonding is a significant value, such as China (Ahmed et al. 2013). One of the studies suggests that Guanxi provides a better understanding about employee perceptions compared to LMX, as Guanxi helps in strengthening informal bonding between employer and employees as well (Shih and Lin 2014). Thus, Guanxi networks are better than LMX for some commentators (Zhang et al. 2015). Further studies may examine the specific impact of Guanxi on employee behavioral, attitudinal and perceptual outcomes for deepening our understanding regarding the relationship between these similar concepts.

4.5 Limitations of LMX research

This section provides an overview of the limitations in the literature on LMX based on our review of the literature. First, as cross-sectional research cannot provide clear and accurate pictures about causal relations researchers could have use longitudinal research designs for determining causality in LMX (Le Blanc and Gonzalez-Roma 2012; Breevaart et al. 2015; Casimir et al. 2014; Kang et al. 2011; Markham et al. 2010; Peng and Lin 2016). Researchers could use experimental methods for a better understanding of LMX outcomes (Hsiung 2012; Lebel 2016; Wang and Wang 2016). Rather than relying solely on quantitative and qualitative techniques for data collection, future researchersmay examine the biological impact of high and low quality LMX on employee perceptions through different experiments. For example, one article did analyze the impact of LMX on stress through examining hair cortisol level of employees (Diebig et al. 2016).

Second, behavioral outcomes are evident to some extent and they can be measured accurately using different techniques, but a major purpose of our article was to cover perceptual and attitudinal outcomes. Perceptions and attitudes may be linked with numerous other factors, hence their measurement is a challenging task and it is not possible to measure them objectively (Lin et al. 2016a; Zhao 2015). Most 65% (45:69) of the quantitative articles gathered data from employees. Despite this focus of most of these studies on self-reported data, almost all of them mentioned this weakness and highlighted that self-reported results may have biasness and inaccuracies since employees may provide inaccurate responses due to pressurized environments and to conform with social pressures (Jordan and Troth 2011; Kimura 2013).

Third, the overall generalization and reliability of findings in the LMX literature is one of the limitations given the amount the Chinese context was used (Chan and Mak 2012; Gu et al. 2015; Lin et al. 2016a; Wu et al. 2013). Cultural values, attitudes and behavior of people vary across culture (Rowley 1997; Rowley and Benson 2002). For example, Guanxi culture may work in China but not in Western countries due to cultural differences. Power distance is also low in Western countries; hence it is very important to not only conduct studies across cultures, but to compare overall differences in mechanisms (Casimir et al. 2014; Fu et al. 2010; Peng and Lin 2016). Future studies may focus on such comparisons to clarify the impact of contextual differences.

Of course, the applicability of theory may not be same as in Western settings due to the impact of different cultures at different levels of relationships, expectations and emotions (Wei et al. 2010). For example, the Asia Pacific region relies on social ties and interpersonal trust in relationships, while other basis of relationships varies in other settings (Rowley et al. 2017). Hence, these theories may not provide support for LMX research in other settings (Casimir et al. 2014). Future studies may integrate LMX with other theories, such as Social Identity Theory or Social Exchange Theory for unveiling the leader–follower relationship in a better way.

The vast majority of articles, 81% (69), were based on quantitative investigations while 13% (11) were theoretical and 6% (5) based on qualitative methods. Of the quantitative articles 85% (60) used regression analysis, hierarchical linear modeling and structure equation modeling. Only 13% (9 out of the 69) of articles used path analysis or other methods. One of the major patterns was the use of cross-sectional design in more than 80% (59–61) of articles. Only 13% (9) of the 69 quantitative articles relied on longitudinal design.

The measures of LMX used by more than 90% (63 out of 69) of articles were predominantly the LMX-7 item scale by Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995) and the LMX-12 item scale. The remaining 10% (7) articles relied on other measures in their studies.

4.6 Implications

The use of multiple theories in the literature suggests that integration of multiple theories in a single study may improve understanding regarding the quality of LMX relationships (Creary et al. 2015). For instance, Resource Theory is suggested as helpful for understanding the role of leader cognition and its impact on their stress level (Morganson et al. 2016). Regarding the specific stress sources, future studies could also examine the role of family issues and problems in impacting on the performance of leaders and employees.

Our review also offers some implications for practice and managers. LMX highlights the individual relationship of each employee with leaders. Thus, supervisors may try to maintain some balance in terms of relationships with each subordinate and try to remain neutral in their communications for developing strong ties with subordinates.

Employee perceptions cannot be monitored or measured exactly, but supervisor’s frequent communication and positive interaction with employees may trigger positive perceptions about them. Thus, employers should take the initiative in terms of communication with employees (Gkorezis et al. 2015; Kafetsios et al. 2014). Leaders may fail to solve the problems of employees in groups because they focus so much on individual relationships as well as perceptual barriers. Thus, leaders need to manage groups in an objective way, which is helped by group focused leadership activities.

Organizations should cultivate learning and collaborative environments for facilitating positive leadership styles and introduce programs that can improve relationships between leaders and followers.

4.7 Future research questions

Based on our review of the literature specific suggestions are made in this section. Researchers commonly investigate the same LMX outcomes. The review process suggests that new outcomes could also be studied in the future; otherwise research will revolve around the same things. Outcomes like humor or cynicism were investigated in just two (2.3%) articles (Gkorezis et al. 2014; Torka et al. 2010). Such kinds of articles need to be investigated in different contexts for understanding the outcomes of LMX from novel perspectives. I-deals have been suggested as a substitute for LMX. Research on I-deals could examine their possible consequences and how employee performance can be improved with their help.

Researchers have already provided evidence that leaders have a different quality of LMX with each follower, but future studies need to examine how employee performance and behavior with high LMX is different compared to employees having mediocre or weak relationships with leaders (Naidoo et al. 2011). Future studies need to examine LMX consequences on leader perceptions and performance as well since leaders are also greatly affected by their relationship with followers. Researchers should focus on understanding the whole cognitive process that leads to changes in emotions over time and how those emotions further lead to other positive and negative outcomes for employees over time.

A positive relationship between fear and employee voice behavior was suggested in one article included in the review process. Thus, further investigation can examine factors that lead to openness of employees with leaders in fearful environments (Lebel 2016). Some 12% (10) of the articles determined just turnover intention from LMX and not actual turnover. Only 2.3% (2) articles added both these variables and found how LMX can link these two variables. Future research could combine them in one model to explain the whole mechanism. Studies on the negative impacts of high quality exchanges were in very few, just 1.1% (1) articles. Only one article determined a negative impact of LMX on employee performance (Naseer et al. 2016).

LMX focuses on dyadic relationships while Social Networking Theory deals with informal networks and relationships of employees. Employees can perform better through strengthen their strong networking because that goes beyond LMX. Hence, future research could examine their relationship and different outcomes (Sparrowe and Liden 2005). Future studies may focus on integrating Resource Theory for deepening understanding regarding the impact of psychological resources on employee performance and how leaders provide requisite resource to their employees. Future studies may also use fairness theory for understanding the impact of employee fairness perceptions on their overall relationship and outcomes.

5 Conclusion

Our review of research on LMX impacts on perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral outcomes highlighted seven outcomes that were consistently investigated: Performance, Job satisfaction, OCB, Turnover intention, Creativity, Organizational commitment and Affective commitment. On one level our overall results are consistent with previous findings since these seven outcomes were studied in the previous studies as well. However, on another level our study unveiled new insights in various dimensions as well. For example, the concept of LMX has been studied in multiple new dimensions as well, such as Guanxi, social and economic LMX and TMX have also been investigated. An unexpected finding was the widespread use of China as a research context. In some ways, of course, this is a useful counter-balance to the more traditional US/Western dominance of research contexts. Future researchers may focus on comparing LMX outcomes in China and Western contexts to help better understand their impact in more depth. Overall, research has produced knowledge that is novel in terms of perceptual outcomes and cognitive processes. However, future researchers may rely on the use of novel methods for more novelty in the results in the future.

References

Agarwal UA, Datta S, Blake-Beard S, Bhargava S (2012) Linking LMX, innovative work behaviour and turnover intentions: the mediating role of work engagement. Career Development International 17(3):208–230

Ahmed I, Ismail KW, Khairuzzaman Wan Ismail W, Mohamad Amin S, Musarrat Nawaz M (2013) A social exchange perspective of the individual Guanxi network: evidence from Malaysian-Chinese employees. Chin Manag Stud 7(1):127–140

Ahmed A, Ahmed A, Arshad MA, Arshad MA, Mahmood A, Mahmood A, Akhtar S (2017) Neglecting human resource development in OBOR, a case of the China–Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC). J Chin Econ Foreign Trade Stud 10(2):130–142

Anand S, Vidyarthi PR, Liden RC, Rousseau DM (2010) Good citizens in poor-quality relationships: idiosyncratic deals as a substitute for relationship quality. Acad Manag J 53(5):970–988

Antonakis J (2017) On doing better science: from thrill of discovery to policy implications. Leadersh Q 28(1):5–21

Bai Y, Li PP, Xi Y (2012) The distinctive effects of dual-level leadership behaviors on employees’ trust in leadership: an empirical study from China. Asia Pac J Manag 29(2):213–237

Ballinger GA, Lehman DW, Schoorman FD (2010) Leader–member exchange and turnover before and after succession events. Organi Behav Hum Decis Process 113(1):25–36

Bang H (2015) Volunteer age, job satisfaction, and intention to stay: a case of nonprofit sport organizations. Leadersh Organ Dev J 36(2):161–176

Bernerth JB, Walker HJ, Harris SG (2016) Rethinking the benefits and pitfalls of leader–member exchange: a reciprocity versus self-protection perspective. Hum Relat 69(3):661–684

Bettis R, Gambardella A, Helfat C, Mitchell W (2014) Quantitative empirical analysis in strategic management. Strateg Manag J 35(7):949–953

Bhal KT, Dadhich A (2011) Impact of ethical leadership and leader–member exchange on whistle blowing: the moderating impact of the moral intensity of the issue. J Bus Ethics 103(3):485–496

Boer D, Deinert A, Homan AC, Voelpel SC (2016) Revisiting the mediating role of leader–member exchange in transformational leadership: the differential impact model. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 25(6):883–899

Breevaart K, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, van den Heuvel M (2015) leader–member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. J Manag Psychol 30(7):754–770

Casimir G, Ngee Keith NK, Yuan Wang K, Ooi G (2014) The relationships amongst leader–member exchange, perceived organizational support, affective commitment, and in-role performance: a social-exchange perspective. Leadersh Organ Dev J 35(5):366–385

Chan SC, Mak WM (2012) Benevolent leadership and follower performance: the mediating role of leader–member exchange (LMX). Asia Pac J Manag 29(2):285–301

Chen G, Kirkman BL, Kanfer R, Allen D, Rosen B (2007) A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. J Appl Psychol 92(2):331

Chen Z, Lam W, Zhong JA (2012) Effects of perceptions on LMX and work performance: effects of supervisors’ perception of subordinates’ emotional intelligence and subordinates’ perception of trust in the supervisor on LMX and consequently, performance. Asia Pac J Manag 29(3):597–616

Chen Y, Yu E, Son J (2014) Beyond leader–member exchange (LMX) differentiation: an indigenous approach to leader–member relationship differentiation. Leadersh Q 25(3):611–627

Chen Y, Wen Z, Peng J, Liu X (2016) Leader–follower congruence in loneliness, LMX and turnover intention. J Manag Psychol 31(4):864–879

Cheng T, Huang GH, Lee C, Ren X (2012) Longitudinal effects of job insecurity on employee outcomes: the moderating role of emotional intelligence and the leader–member exchange. Asia Pac J Manag 29(3):709–728

Chuang A, Hsu RS, Wang AC, Judge TA (2015) Does West “fit” with East? In search of a Chinese model of person–environment fit. Acad Manag J 58(2):480–510

Citrome L (2007) Impact factor? Shmimpact factor!: the journal impact factor, modern day literature searching, and the publication process. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 4(5):54

Cobb AT, Lau RS (2015) Trouble at the next level: effects of differential leader–member exchange on group-level processes and justice climate. Hum Relat 68(9):1437–1459

Cooper C, Booth A, Varley-Campbell J, Britten N, Garside R (2018) Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):85

Creary SJ, Caza BB, Roberts LM (2015) Out of the box? How managing a subordinate’s multiple identities affects the quality of a manager-subordinate relationship. Acad Manag Rev 40(4):538–562

Diebig M, Bormann KC, Rowold J (2016) A double-edged sword: relationship between full-range leadership behaviors and followers’ hair cortisol level. Leadersh Q 27(4):684–696

Dulebohn JH, Bommer WH, Liden RC, Brouer RL, Ferris GR (2012) A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader–member exchange: integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J Manag 38(6):1715–1759

Farh JL, Tsui AS, Xin K, Cheng BS (1998) The influence of relational demography and Guanxi: the Chinese case. Organ Sci 9(4):471–488

Fazio RH, Williams CJ (1986) Attitude accessibility as a moderator of the attitude–perception and attitude–behavior relations: an investigation of the 1984 presidential election. J Person Soc Psychol 51(3):505

Fisk GM, Friesen JP (2012) Perceptions of leader emotion regulation and LMX as predictors of followers’ job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh Q 23(1):1–12

Fu PP, Tsui AS, Liu J, Li L (2010) Pursuit of whose happiness? Executive leaders’ transformational behaviors and personal values. Adm Sci Q 55(2):222–254

Gkorezis P, Petridou E, Xanthiakos P (2014) Leader positive humor and organizational cynicism: LMX as a mediator. Leadersh Organ Dev J 35(4):305–315

Gkorezis P, Bellou V, Skemperis N (2015) Nonverbal communication and relational identification with the supervisor: evidence from two countries. Manag Decis 53(5):1005–1022

Glaso L, Einarsen S (2008) Emotion regulation in leader–follower relationships. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 17(4):482–500

Graen GB, Uhl-Bien M (1995) Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh Q 6(2):219–247

Graves LM, Luciano MM (2013) Self-determination at work: understanding the role of leader–member exchange. Motiv Emot 37(3):518–536

Gu Q, Tang TLP, Jiang W (2015) Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader–member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. J Bus Ethics 126(3):513–529

Guide VDR, Ketokivi M (2015) Notes from the editors: redefining some methodological criteria for the journal. J Oper Manag 37:v–viii

Harris KJ, Wheeler AR, Kacmar KM (2011) The mediating role of organizational job embeddedness in the LMX–outcomes relationships. Leadersh Q 22(2):271–281

Harris TB, Li N, Kirkman BL (2014) Leader–member exchange (LMX) in context: how LMX differentiation and LMX relational separation attenuate LMX’s influence on OCB and turnover intention. Leadersh Q 25(2):314–328

Haynie JJ, Cullen KL, Lester HF, Winter J, Svyantek DJ (2014) Differentiated leader–member exchange, justice climate, and performance: main and interactive effects. Leadersh Q 25(5):912–922

Herman HM, Ashkanasy NM, Dasborough MT (2012) Relative leader–member exchange, negative affectivity and social identification: a moderated-mediation examination. Leadersh Q 23(3):354–366

Hill NS, Kang JH, Seo MG (2014) The interactive effect of leader–member exchange and electronic communication on employee psychological empowerment and work outcomes. Leadersh Q 25(4):772–783

HM Tse H (2014) Linking leader–member exchange differentiation to work team performance. Leadersh Organ Dev J 35(8):710–724

Ho VT, Tekleab AG (2016) A model of idiosyncratic deal-making and attitudinal outcomes. J Manag Psychol 31(3):642–656

Hogg MA, van Knippenberg D, Rast DE III (2012) The social identity theory of leadership: theoretical origins, research findings, and conceptual developments. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 23(1):258–304

Hornung S, Rousseau DM, Glaser J, Angerer P, Weigl M (2010) Beyond top-down and bottom-up work redesign: customizing job content through idiosyncratic deals. J Organ Behav 31(2–3):187–215

Hsiung HH (2012) Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: a multi-level psychological process. J Bus Ethics 107(3):349–361

Huang L, Krasikova DV, Liu D (2016) I can do it, so can you: the role of leader creative self-efficacy in facilitating follower creativity. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 132:49–62

Ioannidis J (2016) The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q 94(3):485–514

Joiner TA, Leveson L (2015) Effective delegation among Hong Kong Chinese male managers: the mediating effects of LMX. Leadersh Organ Dev J 36(6):728–743

Jordan PJ, Troth A (2011) Emotional intelligence and leader member exchange: the relationship with employee turnover intentions and job satisfaction. Leadersh Organ Dev J 32(3):260–280

Kafetsios K, Athanasiadou M, Dimou N (2014) Leaders’ and subordinates’ attachment orientations, emotion regulation capabilities and affect at work: a multilevel analysis. Leadersh Q 25(3):512–527

Kang DS, Stewart J, Kim H (2011) The effects of perceived external prestige, ethical organizational climate, and leader–member exchange (LMX) quality on employees’ commitments and their subsequent attitudes. Pers Rev 40(6):761–784

Kim SK, Jung DI, Lee JS (2013) Service employees’ deviant behaviors and leader–member exchange in contexts of dispositional envy and dispositional jealousy. Serv Bus 7(4):583–602

Kim SL, Han S, Son SY, Yun S (2016) Exchange ideology in supervisor-subordinate dyads, LMX, and knowledge sharing: a social exchange perspective. Asia Pac J Manag 34:1–26

Kimura T (2013) The moderating effects of political skill and leader–member exchange on the relationship between organizational politics and affective commitment. J Bus Ethics 116(3):587–599

Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A, Liira J, Vainio H (2008) Leadership, job well-being, and health effects—a systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Occup Environ Med 50(8):904–915

Kuvaas B, Buch R, Dysvik A, Haerem T (2012) Economic and social leader–member exchange relationships and follower performance. Leadersh Q 23(5):756–765

Le Blanc PM, Gonzalez-Roma V (2012) A team level investigation of the relationship between leader–member exchange (LMX) differentiation, and commitment and performance. Leadersh Q 23(3):534–544

Lebel RD (2016) Overcoming the fear factor: how perceptions of supervisor openness lead employees to speak up when fearing external threat. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 135:10–21

Li Y, Fu F, Sun JM, Yang B (2016) Leader–member exchange differentiation and team creativity: an investigation of nonlinearity. Hum Relat 69(5):1121–1138

Liang SG (2017) Linking leader authentic personality to employee voice behaviour: a multilevel mediation model of authentic leadership development. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 26(3):434–443

Liao H, Liu D, Loi R (2010) Looking at both sides of the social exchange coin: a social cognitive perspective on the joint effects of relationship quality and differentiation on creativity. Acad Manag J 53(5):1090–1109

Liden RC, Sparrowe RT, Wayne SJ (1997) leader–member exchange theory: the past and potential for the future. Res Pers Hum Resour Manag 15:47–120

Liden RC, Erdogan B, Wayne SJ, Sparrowe RT (2006) leader–member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: implications for individual and group performance. J Organ Behav 27(6):723–746

Lin CC, Kao YT, Chen YL, Lu SC (2016a) Fostering change-oriented behaviors: a broaden-and-build model. J Bus Psychol 31(3):399–414

Lin W, Ma J, Zhang Q, Li JC, Jiang F (2016b) How is benevolent leadership linked to employee creativity? The mediating role of leader–member exchange and the moderating role of power distance orientation. J Bus Ethics 152:1–17

Lind EA, Tyler TR (1988) The social psychology of procedural justice. Springer, Berlin

Little LM, Gooty J, Williams M (2016) The role of leader emotion management in leader–member exchange and follower outcomes. Leadersh Q 27(1):85–97

Liu Z, Cai Z, Li J, Shi S, Fang Y (2013) Leadership style and employee turnover intentions: a social identity perspective. Career Dev Int 18(3):305–324

Luu TT, Rowley C (2015) From value-based human resource practices to i-deals: software companies in Vietnam. Pers Rev 44(1):39–68

Ma L, Qu Q (2010) Differentiation in leader–member exchange: a hierarchical linear modeling approach. Leadersh Q 21(5):733–744

Markham SE, Yammarino FJ, Murry WD, Palanski ME (2010) Leader–member exchange, shared values, and performance: agreement and levels of analysis do matter. Leadersh Q 21(3):469–480

Martin R, Guillaume Y, Thomas G, Lee A, Epitropaki O (2016) Leader–member exchange (LMX) and performance: a meta-analytic review. Pers Psychol 69(1):67–121

Meyer B, Burtscher MJ, Jonas K, Feese S, Arnrich B, Troster G, Schermuly CC (2016) What good leaders actually do: micro-level leadership behaviour, leader evaluations, and team decision quality. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 25(6):773–789

Morganson VJ, Major DA, Litano ML (2016) A multilevel examination of the relationship between leader–member exchange and work–family outcomes. J Bus Psychol 1:1–15

Munoz-Doyague MF, Nieto M (2012) Individual creativity performance and the quality of interpersonal relationships. Ind Manag Data Syst 112(1):125–145

Naidoo LJ, Scherbaum CA, Goldstein HW, Graen GB (2011) A longitudinal examination of the effects of LMX, ability, and differentiation on team performance. J Bus Psychol 26(3):347–357

Naseer S, Raja U, Syed F, Donia MB, Darr W (2016) Perils of being close to a bad leader in a bad environment: exploring the combined effects of despotic leadership, leader member exchange, and perceived organizational politics on behaviors. Leadersh Q 27(1):14–33

Newman A, Schwarz G, Cooper B, Sendjaya S (2015) How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: the roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J Bus Ethics 145:1–14

Nolzen N (2018) The concept of psychological capital: a comprehensive review. Manag Rev Q 68:1–41

Oren L, Tziner A, Sharoni G, Amor I, Alon P (2012) Relations between leader–subordinate personality similarity and job attitudes. J Manag Psychol 27(5):479–496

Pan SY, Lin KJ (2016) Who suffers when supervisors are unhappy? The roles of leader–member exchange and abusive supervision. J Bus Ethics 151:1–13

Peng JC, Lin J (2016) Linking supervisor feedback environment to contextual performances: the mediating effect of leader–member exchange. Leadersh Organ Dev J 37(6):802–820

Poon HF, Rowley C (2007) Contemporary research on management and human resources in China: a comparative content analysis of two leading journals: research note. Asia Pac Bus Rev 13(1):133–153

Redeker M, de Vries RE, Rouckhout D, Vermeren P, De Fruyt F (2014) Integrating leadership: the leadership circumplex. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 23(3):435–455

Reeb D, Sakakibara M, Mahmood IP (2012) From the editors: endogeneity in international business research. J Int Bus Stud 43(3):211–218

Rousseau DM (2005) I-deals, idiosyncratic deals employees bargain for themselves. ME Sharpe, New York

Rousseau DM, Manning J, Denyer D (2008) Evidence in management and organizational science: assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. Acad Manag Ann 2(1):475–515

Rowley C (1997) Conclusion: reassessing HRM’s convergence. Asia Pac Bus Rev 3(4):197–210

Rowley C, Benson J (2002) Convergence and divergence in Asian human resource management. Calif Manag Rev 44(2):90–109

Rowley C, Bae J, Horak S, Bacouel-Jentjens S (2017) Distinctiveness of human resource management in the Asia Pacific region: typologies and levels. Int J Hum Resour Manag 28(10):1393–1408

Shapiro DL, Hom P, Shen W, Agarwal R (2016) How do leader departures affect subordinates’ organizational attachment? A 360-degree relational perspective. Acad Manag Rev 41(3):479–502

Shih CT, Lin CCT (2014) From good friends to good soldiers: a psychological contract perspective. Asia Pac J Manag 31(1):309–326

Sluss DM, Thompson BS (2012) Socializing the newcomer: the mediating role of leader–member exchange. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 119(1):114–125

Soane E, Booth JE, Alfes K, Shantz A, Bailey C (2018) Deadly combinations: how leadership contexts undermine the activation and enactment of followers’ high core self-evaluations in performance. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 27:1–13

Sparrowe RT, Liden RC (2005) Two routes to influence: integrating leader–member exchange and social network perspectives. Adm Sci Q 50(4):505–535

Spitzmuller M, lies R (2010) Do they [all] see my true self? Leader’s relational authenticity and followers’ assessments of transformational leadership. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 19(3):304–332

Stoffers M, Jol IJMVH, Notelaers G (2014) Towards a moderated mediation model of innovative work behavior enhancement. J Organ Change Manag 27(4):642–659

Sun LY, Chow IHS, Chiu RK, Pan W (2013) Outcome favorability in the link between leader–member exchange and organizational citizenship behavior: procedural fairness climate matters. Leadersh Q 24(1):215–226

Torka N, Schyns B, KeesLooise J (2010) Direct participation quality and organizational commitment: the role of leader–member exchange. Empl Relat 32(4):418–434

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14(3):207–222

Triaridis S, Kyrgidis A (2010) Peer review and journal impact factor: the two pillars of contemporary medical publishing. Hippokratia 14(Suppl 1):5

TrongLuu T, TrongLuu T, Rowley C, Rowley C (2016) The relationship between cultural intelligence and i-deals: trust as a mediator and HR localization as a moderator. Int J Organ Anal 24(5):908–931

Tse HH, Troth AC (2013) Perceptions and emotional experiences in differential supervisor–subordinate relationships. Leadersh Organ Dev J 34(3):271–283

Tu Y, Lu X (2016) Work-to-life spillover effect of leader–member exchange in groups: the moderating role of group power distance and employee political skill. J Happiness Stud 17(5):1873–1889

Uhl-Bien M (2011) Relational leadership theory: exploring the social processes of leadership and organizing. In: Leadership, gender, and organization, Springer, Dordrecht, pp 75–108

Van Knippenberg D, De Cremer D (2008) Leadership and fairness: taking stock and looking ahead. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 17(2):173–179

Van Vugt M, De Cremer D (2003) Leader endorsement in social dilemmas: comparing the instrumental and relational perspectives. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 13(1):155–184

Volmer J, Spurk D, Niessen C (2012) Leader–member exchange (LMX), job autonomy, and creative work involvement. Leadersh Q 23(3):456–465

Walker E, Hernandez AV, Kattan MW (2008) Meta-analysis: its strengths and limitations. Clevel Clin J Med 75(6):431

Walumbwa FO, Mayer DM, Wang P, Wang H, Workman K, Christensen AL (2011) Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: the roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 115(2):204–213

Wang BX, Rowley C (2016) Business networks and the emergence of Guanxi capitalism in China: the role of the ‘Invisible Hand’. In: Business networks in East Asian capitalisms, p 93

Wang CJ, Wang CJ (2016) Does leader–member exchange enhance performance in the hospitality industry? The mediating roles of task motivation and creativity. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 28(5):969–987

Wayne SJ, Green SA (1993) The effects of leader–member exchange on employee citizenship and impression management behavior. Hum Relat 46(12):1431–1440

Wei LQ, Liu J, Chen YY, Wu LZ (2010) Political skill, supervisor–subordinate Guanxi and career prospects in Chinese firms. J Manag Stud 47(3):437–454

Wu JB, Tsui AS, Kinicki AJ (2010) Consequences of differentiated leadership in groups. Acad Manag J 53(1):90–106

Wu LZ, Kwan HK, Wei LQ, Liu J (2013) Ingratiation in the workplace: the role of subordinate and supervisor political skill. J Manag Stud 50(6):991–1017

Xiaqi D, Kun T, Chongsen Y, Sufang G (2012) Abusive supervision and LMX: leaders’ emotional intelligence as antecedent variable and trust as consequence variable. Chin Manag Stud 6(2):257–270

Xu AJ, Loi R, Lam LW (2015) The bad boss takes it all: how abusive supervision and leader–member exchange interact to influence employee silence. Leadersh Q 26(5):763–774

Yuan L, Yuan L, Xiao S, Xiao S, Li J, Li J, Ning L (2016) leader–member exchange differentiation and team member performance: the moderating role of the perception of organizational politics. Int J Manpow 37(8):1347–1364

Zhang MM, Fan D (2014) Expatriate skills training strategies of Chinese multinationals operating in Australia. Asia Pac J Hum Resourc 52(1):60–76

Zhang L, Morand D (2014) The linkage between status-leveling symbols and work attitudes. J Manag Psychol 29(8):973–993

Zhang XA, Li N, Harris TB (2015) Putting non-work ties to work: the case of Guanxi in supervisor–subordinate relationships. Leadersh Q 26(1):37–54

Zhao H (2015) leader–member exchange differentiation and team creativity: a moderated mediation study. Leadersh Organ Dev J 36(7):798–815

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mumtaz, S., Rowley, C. The relationship between leader–member exchange and employee outcomes: review of past themes and future potential. Manag Rev Q 70, 165–189 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00163-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00163-8