Abstract

Recent demographic and economic research has analyzed the expected increase in the proportion of the population who are elderly. One consequence of an increasing elderly population is expansion in health care utilization, hence funding problems may arise.. European institutions encourage member states to promote good health among their citizens to mitigate the ageing effects on the health care system. Our objective was to examine the effect of healthy lifestyles among Southern European older adults on health care utilization by focusing on the number of outpatient doctor visits (ODV) and nights hospitalized (NH). Negative binominal regressions were conducted using a panel data set consisting of five waves (2004–2015) of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Our results add new empirical evidence on the effect of Southern European older adults’ lifestyles on their health care utilization. Engaging in vigorous physical activities reduces the number of ODV visits and NH by 7.8% and 28.25%, respectively. Moreover, smoking increases NH by 14.22%. Member states should establish policies to promote healthy lifestyles, with vigorous physical activities playing a key role, to reduce health services utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Demographic change has become one of the most significant transformations in societies. It is expected that elderly people as a percentage of the entire population will rise from 18% to 28% by 2060 (European Commission 2013; 2015). The European Union (EU) is concerned about how these population projections will affect the health care system in future decades (Tordrup et al. 2013; Vollaard and Martinsen 2017). Hence, if the European welfare state wants to continue being a cornerstone, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of aging. Health expenditures currently represent, on average, 15.3% of total public expenditures in the EU28 (Eurostat 2019). Older adults have a higher probability of using and spending more on health care (Aguado et al. 2012; de Meijer et al. 2013; Denton et al. 2006). Moreover, trying to disentangle how elderly people use the health care system has major relevance for generating forecasts based on plausible scenarios for future decades. Achieving greater equity within populations and providing better service regardless of income or economic status are key EU objectives (Tordrup et al. 2013; Viia et al. 2016; Vollaard and Martinsen 2017).

In many countries, elderly people play a major role in society. Due to the economic crisis, some grandfathers are in charge of their descendants (children and grandchildren) helping them with housing or food. Hence, the economic limitations of this cohort have increased. Jeon et al. (2017) studied this issue for Korea considering the role of the most important social program, the National Basic Livelihood Security System (NBLSS), that provides non-contributory transfers to low-income families. An important finding is that the low-income disabled individuals not participating in the NBLSS have greater problems accessing medical services than those participating in the program.

The future of European health care services depends on organization and funding measures (Åhs and Westerling 2006; Thomson et al. 2009; Hosseinichimeh et al. 2016; Jeon et al. 2017). Regidor et al. (2008) identified differences in the use of health care services between the public and private sectors. Hence, the type of health care model (National Health Services or Social Security Systems) is relevant. In addition, in some countries, visiting a specialist requires a general practitioner (GP) referral (Majo and van Soest 2012). Thus, waiting times could increase the use of emergency services.

Going to a specialist may require an economic effort in those systems where total coverage is not compulsory. Utilization differences are related to income inequalities (Cseh et al. 2015), which affect health outcomes (Pascual et al. 2005). Low-income households must wait until the public system provides them with an appointment, while high-income households do not have to wait (Hoebel et al. 2017). Differences exist in medical resource utilization depending on the health system sector (Abásolo et al. 2014): GPs, specialists or hospitalizations. The higher the income, the lower the probability of using a GP and being hospitalized, but the probability of using a specialist is higher.

The European Commission wants member states to enhance primary care services, especially GPs. Aguado et al. (2012) collected data from thousands of patients and demonstrated that older adults use more services. The probability of suffering from multimorbidity is higher for elderly people, which explains this trend. According to Hewitt et al. (2016), the probability is 74% higher. Fortin (2005) suggests that it is nearly 100% for their study using Canadian data. Glynn et al. (2011) found that suffering from different illnesses at the same time increases health care utilization, especially for primary care.

Lifestyle is also a relevant factor in health care utilization. In general, following a balanced diet or engaging in physical activities reduces health care utilization. These people are likely to have fewer health problems and higher level cognitive functioning than those who do not (Kesavayuth et al. 2018; Stegeman et al. 2012). Nevertheless, there is some disagreement in the literature on the effect of physical activity on health care utilization. According to Lee et al. (2017), people that usually engage in physical activities use more health services, while Qi et al. (2006) did not observe a significant association.

Promoting efficiency gains is a major aim of the European Commission. Therefore, European citizens are encouraged to use GPs more in order to reduce utilization of specialists, hospital care and emergency services. Remaining active in the labor market (as long as possible) or self-managing chronic conditions, if hospitalization is not required, are also EU recommendations. Other public policies suggested by the European Commission (2013, 2014) include promoting good health by investing in disease prevention to reduce higher long-term costs and early deaths, promoting a healthy workforce, without a large increase in public expenditures, and reducing health inequalities.

The objective of this study was to examine the effect of healthier lifestyles among elderly people on health care utilization measured by the number of outpatient doctor visits (ODV) and the number of nights hospitalized in a year (NH). Southern European countries (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Slovenia) were the focus due to similarities in health systems and Mediterranean lifestyle.

Methods

Data Description

The data were retrieved from the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th and 6th waves of the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (Van den Hout 2015; Börsch-Supan 2018a, b, c, d, e). Wave 3 (SHARELIFE) was not included in the analysis since the questionnaire was dissimilar to the others and focused on childhood health. The SHARE survey developed as the result of the European institutional goal of creating deeper and strongest cooperation among member states in providing good data on elderly people. This survey includes data from health to socioeconomic status passing through lifestyles or personal networks. Table 1 depicts descriptive statistics and defines each variable.

Our dependent variables (ODV and NH) were obtained from the questions HC602_STtoMDoctor (“During the last twelve months, about how many times in total have you seen or talked to a medical doctor about your health? Please exclude dentist visits and hospital stays, but include emergency room or outpatient clinic visits”) and HC014_TotNightsinPT (“How many nights altogether have you spent in hospitals during the last twelve months?”) For simplicity, it was assumed that the first one can be simplified as the number of outpatient doctor visits (ODV).

As in previous studies (Majo and van Soest 2012; Van den Hout 2015), gender (Female), marital status (Single), participation in the labor market (InLabFor) and educational level (Education) were included. Education was considered a proxy for socioeconomic level. Moreover, country dummies variables were included to control for country differences. In the estimations, no education and Portugal were reference categories.

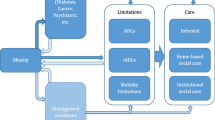

The number of chronic diseases (NCD) and number of limitations in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) were used to capture multimorbidity. Self-assessed good health status (SAGHS) was also included. Physical characteristics determined the physical health status and BMI was used to classify respondents. Obese corresponds to respondents whose BMI exceeded 30. Hence, the importance of obesity is double-sided. First, illness has a direct effect. Second, people who are obese have a higher probability of suffering from other sicknesses, like diabetes, and can become insulin resistant (Algoblan et al. 2014; Kearns et al. 2014).

Moreover, the aim was to study how lifestyle affects health care utilization among elderly people. Three covariates capture whether the person ever smoked daily (Smoke), engaged in vigorous activities nearly every day (Vigorous Physical Activities Engagement, VPAE) or drank alcohol daily (DrinkingDaily).

Estimation Method

Count data models are often used to analyze health care utilization (Riphahn et al. 2003; Cameron and Trivedi 2005; González-Alvarez and Clavero-Barranquero 2005; Jones et al. 2013). The study aim was to explain the effect of lifestyles on ODV and NH controlling for other socioeconomic and health factors. Our models were based on the negative binomial distribution and estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The density function is as follows (Jones et al. 2013):

where:

If the parameter α tends to 0, it would be a Poisson distribution. An overdispersion test was carried out, where the null hypothesis is that the value of alpha equals zero, meaning that equidispersion exists. Test results indicated the existence of overdispersion.

Zero-inflated models are used if an excess of zeros exists. Moreover, Jones et al. (2013) differentiate between non-users and potential users. According to these authors, such models are not appropriate for potential users. Our database contains people older than 50 and every individual is considered a potential user.

Since the database has a panel structure, panel data models suitable for count data were used. Fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models capture unobserved effects. The difference is that, in the RE model, this effect is assumed to be a variable which is not correlated with the other explanatory variables (Wooldridge 2010). The Hausman Test was carried out to determine the most convenient model (FE or RE). The null hypothesis was that no correlation exists between the unobserved effect and the other variables. When the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, the FE model should be used. These results can be seen in Table 2 and Table 3. Pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) was the first approach used for the panel models. As this specification is merely an OLS regression, each individual was treated as a cluster in order to obtain robust standard errors.

Results

Outpatient Doctor Visits (ODV)

Table 2 shows that when age increases doctor visits also increase, suggesting the existence of a non-linear relationship. Gender also matters as females make 7.14% more ODV than men. Being single had a negative effect on the number of ODV. Moreover, people who remained active in the labor market were 16.05% less prone to visit a doctor than their unemployed peers. The country where respondents live was also relevant, since country-specific health systems differ. Higher education was associated with more ODV.

As SAGHS worsened, the probability of a doctor visit increased. Our results suggest that people whose self-assessed health status is at least fair visit a doctor 30% less often. A higher number of chronic diseases, limitations in daily living activities and being obese increased the ODV probability. Smoke was not statistically significant, but had a positive effect. Being a drinker was statistically significant and was related to lower ODV use. Considering this, an interaction term between drinking every day and the number of chronic conditions (DDNCD) was introduced. The results suggest that the probability of an ODV increased when the drinker suffered from chronic conditions. Finally, engaging in vigorous physical activities reduced ODV by 7.8%.

Nights Hospitalized (NH)

Table 3 shows the results for the NH. Women were hospitalized 26.58% less than men. Moreover, remaining active in the labor market reduced the number of nights in the hospital per year by 21.49%. Country differences remained statistically significant. Regarding the socioeconomic status proxies, people with tertiary education had fewer NH than those with less education. Serious health conditions can arise if a person is not sufficiently worried about their health status, which might lead to an increase in NH.

Our results suggest that smoking habits and VPAE are relevant. Being a smoker increased the number of NH by 14.22%. Engaging vigorous physical activities reduced NH by 28.25%.

Discussion

In general, our results regarding socioeconomic status were quite similar to those described in the literature. Nevertheless, the paper presents updated findings on the effect of lifestyle on health care utilization among elderly people living in Southern Europe controlling for country-specific differences. Note that the average age in the sample was 67 and that only people older than 50 were included. These reasons explain the finding that Age was not always highly statistically significant. Moreover, being female had a positive effect on ODV. Females are more likely to suffer from disabling conditions (World Health Organization and The World Bank 2011) which may be a reason for more ODV. Glaesmer et al. (2012) suggested that part of this gender effect is attributable to the health care system. In some countries, specific programs for women are covered which may help women achieve better control of their health status. Women had fewer NH than men did. Being single had no clear effect on ODV but affected positively the NH. As most single people live alone, perhaps they do not worry about their health status as much as their married peers do.

Socioeconomic characteristics also had an important effect on health care utilization. Our results suggest that highly educated people had a higher number of ODV. According to Devaux (2015), highly educated people had better access to the health care system, which enabled visiting their GP or specialist more often than their less educated peers. Remaining active in the labor market also reduces the number of outpatient doctor visits. Kraut et al. (2000) showed that hospital admissions and physician visits are higher for unemployed people.

Moreover, our results regarding health status variables are consistent with previous literature. As expected, having at least a fair self-perceived health status had a negative impact on the use of both types of services. Nevertheless, multimorbidity, limitations of daily living and obesity were positively associated with ODV and NH. Lehnert et al. (2011), Hewitt et al. (2016) and Cantarero-Prieto et al. (2016) showed that multimorbitidy and limitations increase health services use and the associated costs.

Of particular interest is the group of variables capturing lifestyle. Our results suggest that a history of smoking daily increases NH. This is consistent with previous literature (Kahende et al. 2009; Wacker et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018). Schlichthorst et al. (2016) found a negative correlation, however, they only included men aged younger than 55. Our study only included elderly people and the effect of smoking daily may be more prominent at these ages.

Drinking every day, when the respondent is healthy, leads to less health care utilization. This can be explained by the fact that non-drinkers report poorer health status than their drinker peers (Ormond and Murphy 2017). Nevertheless, the drinking habit when the respondent suffers from chronic diseases is associated with more visits to the GP. This shows that the drinking habit does play a key role in determining health care utilization (Polen et al. 2001).

Engaging in vigorous physical activities reduced the probability of NH and the number of ODV. Similar results were found by Woolcott et al. (2010) and Sari (2011). Being physically active reduced the probability of suffering from illnesses and improved self-perceived health status (Stegeman et al. 2012). Nevertheless, Lee et al. (2017) proved that healthy lifestyles increase health care utilization through the preventive services.

Conclusions

We have tried to determine how the lifestyles of elderly people affect their health care utilization in Southern European countries in order to provide new insight. New empirical evidence is added on the effect of lifestyles on the ODV and the NH by using five waves of the SHARE survey and focusing on elderly people.

Our results highlight the effect that engaging in physical activities and remaining active in the labor market have on reducing ODV and NH. Hence, public health campaigns promoted by member states should incorporate this evidence. Moreover, policymakers must consider two facts: Firstly, employers promote early retirement among their oldest employees. Secondly, there is a conflict between promoting the country’s productivity and trying to keep people active in the labor market (Van Dalen et al. 2010).

Because of the heterogeneous nature of ODVs and NH in Southern European countries and the growing elderly population, more effort in this area is needed to enhance healthcare system sustainability. Moreover, country differences remain relevant. In terms of ODV, Italy and Spain are the countries where people are more prone to use these services. On the other hand, Slovenia is the country where the number of nights in the hospital is higher. These two facts highlight the necessity of focalizing EU policies in some countries to achieve the goal of convergence in health care utilization. This study has some potential limitations. The effects on healthcare utilization are estimated using self-reported data on physical activity and self-assessed health status, which cannot be independently verified.

References

Abásolo, I., Negrín, M. A., & Pinilla, J. (2014). Utilisation and waiting times: Two inseparable aspects of the analysis of equity. Revista Hacienda Pública Española, 208(1), 11–38.

Aguado, A., Rodríguez, D., Flor, F., Sicras, A., Ruiz, A., & Prados-Torres, A. (2012). Distribución del gasto sanitario en atención primaria según edad y sexo: un análisis retrospectivo. Atención Primaria, 44(3), 145–152.

Åhs, A. M. H., & Westerling, R. (2006). Health care utilization among persons who are unemployed or outside the labour force. Health Policy, 78(2–3), 178–193.

Algoblan, A., Alalfi, M., & Khan, M. (2014). Mechanism linking diabetes mellitus and obesity. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 7, 587–591. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S67400.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2018a). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 1. Release version: 6.1.1. https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w1.611.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2018b). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 2. Release version: 6.1.1. https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w2.611.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2018c). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 4. Release version: 6.1.1. https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w4.611.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2018d). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 5. Release version: 6.1.1. https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.611.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2018e). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) wave 6. Release version: 6.1.1. https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.611.

Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Korbmacher, J., Malter, F., et al. (2013). Data resource profile: The survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(4), 992–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt088.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Count data. In Microeconometrics. Methods and applications (1st ed., pp. 802–808). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cantarero-Prieto D., Pascual-Saez, M., & Blaquez-Fernandez, C. (2016). Statistical models of economic evaluation in public policies. Analysis of health care resource utilization (No. 8). Available at: http://www.ief.es/docs/destacados/publicacio

Cseh, A., Koford, B. C., & Phelps, R. T. (2015). Hospital utilization and universal Health insurance coverage: Evidence from the Massachusetts Health care reform act. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 13(6), 627–635.

de Meijer, C., Wouterse, B., Polder, J., & Koopmanschap, M. (2013). The effect of population aging on health expenditure growth: A critical review. European Journal of Ageing, 10(4), 353–361.

Denton, F. T., Mountain, D. C., & Spencer, B. G. (2006). Age, retirement, and expenditure patterns: An econometric study of older households. Atlantic Economic Journal, 34(4), 421–434.

Devaux, M. (2015). Income-related inequalities and inequities in health care services utilisation in 18 selected OECD countries. The European Journal of Health Economics, 16(1), 21–33.

European Commision. (2015). The 2015 Ageing Report. Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2013-2060). Luxembourg.

European Commission. (2013). Investing in health. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2012/pdf/ocp125_en.pdf. Accessed 4 March 2019.

European Commission. On effective, accessible and resilient health systems. , Pub. L. No. COM (2014) 215 Final (2014). https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/systems_performance_assessment/docs/com2014_215_final_en.pdf. Accessed 4 March 2019.

Eurostat. (2019). EUROSTAT database. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Accessed 10 July 2019.

Fortin, M. (2005). Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. The Annals of Family Medicine, 3(3), 223–228.

Glaesmer, H., Brähler, E., Martin, A., Mewes, R., & Rief, W. (2012). Gender differences in healthcare utilization: The mediating effect of utilization propensity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(5), 1266–1279.

Glynn, L. G., Valderas, J. M., Healy, P., Burke, E., Newell, J., Gillespie, P., & Murphy, A. W. (2011). The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost. Family Practice, 28(5), 516–523.

González-Alvarez, M. L., & Clavero-Barranquero, A. (2005). Una revisión de modelos econométricos aplicados al análisis de demanda y utilización de servicios sanitarios. Hacienda pública española, 173, 129–162.

Hewitt, J., McCormack, C., Tay, H. S., Greig, M., Law, J., Tay, A., Asnan, N. H., Carter, B., Myint, P. K., Pearce, L., Moug, S. J., McCarthy, K., & Stechman, M. J. (2016). Prevalence of multimorbidity and its association with outcomes in older emergency general surgical patients: An observational study. BMJ Open, 6(3), e010126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010126.

Hoebel, J., Rommel, A., Schröder, S., Fuchs, J., Nowossadeck, E., & Lampert, T. (2017). Socioeconomic inequalities in Health and perceived unmet needs for healthcare among the elderly in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1127.

Hosseinichimeh, N., Martin, E. G., & Weinberg, S. (2016). Do changes in health insurance coverage explain interstate variation in emergency department utilization? World Medical & Health Policy, 8(1), 58–73.

Jeon, B., Noguchi, H., Kwon, S., Ito, T., & Tamiya, N. (2017). Disability, poverty, and role of the basic livelihood security system on health services utilization among the elderly in South Korea. Social Science & Medicine, 178, 175–183.

Jones, A. M., Rice, N., Bago d’Uva, T., & Balia, S. (2013). Count data models. In Applied health economics (2nd ed., pp. 295–341). Abingdon: Routledge.

Kahende, J. W., Adhikari, B., Maurice, E., Rock, V., & Malarcher, A. (2009). Disparities in health care utilization by smoking status--NHANES 1999-2004. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(3), 1095–1106.

Kearns, K., Dee, A., Fitzgerald, A. P., Doherty, E., & Perry, I. J. (2014). Chronic disease burden associated with overweight and obesity in Ireland: The effects of a small BMI reduction at population level. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 143.

Kesavayuth, D., Liang, Y., & Zikos, V. (2018). An active lifestyle and cognitive function: Evidence from China. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 12(September 1980), 183–191.

Kraut, A., Mustard, C., Walld, R., & Tate R. (2000). Unemployment and health care utilization. Scandanavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 26(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.527.

Lee, I.-C., Chang, C.-S., & Du, P.-L. (2017). Do healthier lifestyles lead to less utilization of healthcare resources? BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 243.

Lehnert, T., Heider, D., Leicht, H., Heinrich, S., Corrieri, S., Luppa, M., et al. (2011). Review: Health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Medical Care Research and Review, 68(4), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558711399580.

Majo, M. C., & van Soest, A. (2012). Income and health care utilization among the 50+ in Europe and the US. Applied Econometrics, 28(4), 3–22.

Ormond, G., & Murphy, R. (2017). An investigation into the effect of alcohol consumption on health status and health care utilization in Ireland. Alcohol, 59, 53–67.

Pascual, M., Cantarero, D., & Sarabia, J. M. (2005). Income inequality and health: Do the equivalence scales matter? Atlantic Economic Journal, 33(2), 169–178.

Polen, M. R., Green, C. A., Freeborn, D. K., Mullooly, J. P., & Lynch, F. (2001). Drinking patterns, health care utilization, and costs among HMO primary care patients. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 28(4), 378–399.

Qi, V., Phillips, S. P., & Hopman, W. M. (2006). Determinants of a healthy lifestyle and use of preventive screening in Canada. BMC Public Health, 6, 1–8.

Regidor, E., Martínez, D., Calle, M. E., Astasio, P., Ortega, P., & Domínguez, V. (2008). Socioeconomic patterns in the use of public and private health services and equity in health care. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), 183.

Riphahn, R. T., Wambach, A., & Million, A. (2003). Incentive effects in the demand for health care: A bivariate panel count data estimation. Journal of Applied Econometrics. 18(4), 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.680

Sari, N. (2011). Exercise, physical activity and healthcare utilization: A review of literature for older adults. Maturitas, 70(3), 285–289.

Schlichthorst, M., Sanci, L. A., Pirkis, J., Spittal, M. J., & Hocking, J. S. (2016). Why do men go to the doctor? Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with healthcare utilisation among a cohort of Australian men. BMC Public Health, 16(S3), 1028.

Stegeman, I., Otte-Trojel, T., Costongs, C., & Considine, J. (2012). Healthy and active ageing. http://www.healthyageing.eu/sites/www.healthyageing.eu/files/featured/HealthyandActiveAgeing.pdf. Accessed 4 March 2019.

Thomson, S., Foubister, T., & Mossialos, E. (2009). Financing health care in the European Union: Challenges and policy responses. Copenhagen: World Health Organization . http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/98307/E92469.pdf. Accessed 4 March 2019.

Tordrup, D., Angelis, A., & Kanavos, P. (2013). Preferences on policy options for ensuring the financial sustainability of health care services in the future: Results of a stakeholder survey. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 11(6), 639–652.

Van Dalen, H. P., Henkens, K., & Schippers, J. (2010). How do employers cope with an ageing workforce? Demographic Research, 22, 1015–1036.

Van den Hout, W. (2015). The value of productivity in Health policy. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 13(4), 311–313.

Viia, A., Toots, A., Mali, B. Č., Kerbler, B., Øverland, E. F., Terk, E., et al. (2016). Futures of European welfare models and policies: Seeking actual research questions, and new problem-solving arsenal for European welfare states. European Journal of Futures Research, 4(1), 1.

Vollaard, H., & Martinsen, D. S. (2017). The rise of a European healthcare union. Comparative European Politics, 15(3), 337–351.

Wacker, M., Holle, R., Heinrich, J., Ladwig, K.-H., Peters, A., Leidl, R., & Menn, P. (2013). The association of smoking status with healthcare utilisation, productivity loss and resulting costs: Results from the population-based KORA F4 study. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 278.

Wang, Y., Sung, H.-Y., Yao, T., Lightwood, J., & Max, W. (2018). Health care utilization and expenditures attributable to cigar smoking among US adults, 2000-2015. Public Health Reports, 133(3), 329–337.

Woolcott, J. C., Ashe, M. C., Miller, W. C., Shi, P., & Marra, C. A. (2010). Does physical activity reduce seniors’ need for healthcare?: A study of 24 281 Canadians. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(12), 902–904.

Wooldridge, J. (2010). Basic linear unobserved E¤ects panel data models. In Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed., pp. 281–344). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

World Health Organization & The World Bank. (2011). World report on disability. WHO Library. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/

Xu, X., Bishop, E. E., Kennedy, S. M., Simpson, S. A., & Pechacek, T. F. (2015). Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(3), 326–333.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Governance and Economics Research Network (GEN) for having published an earlier version of this study as GEN Working Paper B2018-1.

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 (DOIs: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w1.611, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w2.611, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w4.611, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.611, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.611), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: N°227822, SHARE M4: N°261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cantarero-Prieto, D., Pascual-Sáez, M. & Lera, J. Healthcare Utilization and Healthy Lifestyles among Elderly People Living in Southern Europe: Recent Evidence from the SHARE. Atl Econ J 48, 53–66 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-020-09657-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-020-09657-3