Abstract

Objectives

To describe and evaluate Chicago’s Quality Interaction Program (QIP) for police recruits. The training focused on procedural justice, interpersonal communication, decision-making, cultural awareness, and stress management during encounters with the public. Attention was given to emotions, empathy, and communication skills.

Methods

The QIP is an underutilized approach to police training that involves engaging recruits through applied case studies, role-playing scenarios, repetitive opportunities for practice, and individualized feedback. The impact of QIP training on 142 officers’ attitudes and behaviors was evaluated in a randomized control trial. Treatment and control groups were assessed through responses to self-reported questionnaires as well as research-coded videos that recorded officers during role-playing scenarios.

Results

The QIP did not change recruits’ attitudes toward procedural justice, nor did it impact their self-reported interpersonal communication skills. However, the program was effective at creating more respectful and reassuring behaviors during role-playing scenarios that were videotaped. The program also improved recruits’ decision-making during a scenario with rebellious youths and reduced officers’ reliance on force and arrest relative to controls.

Conclusion

The QIP initiative was instrumental in moving police training beyond “talking heads” to interactive adult education, while promoting a more sophisticated understanding of human dynamics during police–public encounters. The results, however, were mixed, due in part to a training academy environment that emphasized aggressive policing and officer safety. Thus, reform-minded agencies may need to rethink the totality of the training experience to achieve strong results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background and problem statement

The police in democratic societies face a multitude of interpersonal challenges, including resolving domestic disputes, de-escalating situations involving mental health crises, responding to traumatized crime victims, managing organized protests, interacting with rebellious youths and gang members, showing sensitivity and fairness to diverse racial, ethnic, and religious groups, and many other challenges. A series of high visibility officer-involved shootings of young black men covered since the fall of 2014 have contributed to a new “crisis of legitimacy” in American policing. As a result, the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015) was created to recommend strategies for restoring public trust and improving police–community relations. The Task Force recommended new and better training for police officers in a variety of areas, ranging from interpersonal communication skills to crisis response. The Task Force emphasized procedural justice and de-escalation skills during encounters with the public to decrease officers’ reliance on force and to begin rebuilding public trust. Prior to, but consistent with, the Task Force recommendations, we worked with the Chicago Police Department to develop, implement, and evaluate a new training program called the Quality Interaction Program (QIP) for police recruits. The QIP, implemented in 2010, became a launching pad for procedural justice training in the United States, Britain, Scotland, and Australia. Hence, this belated publication of the original QIP evaluation provides a missing link in the history of procedural justice training and includes lessons we have yet to fully learn.

Encounters with community members, whether voluntary or involuntary, are at the heart of police work. On a daily basis, officers have interactions with community members in numerous settings: walk-ins at the front desk, crime reports by telephone, traffic or street stops, emergency and non-emergency calls for service, investigative interviews, community meetings, and other exchanges. The public’s expectations of the police when responding to these diverse incidents are very high. Officers are expected to effectively play multiple roles, including enforcer, social worker, marriage counselor, parent/disciplinarian, crowd-control manager, criminal investigator, and group facilitator. One minute, an officer might be arresting a disrespectful gang member and, soon thereafter, taking a report from a traumatized elderly victim of armed robbery. In addition to physical prowess, officers are expected to have strong interpersonal skills and the ability to transition from one scenario to the next, while always treating everyone equally, respectfully, and professionally. In addition to showing empathy and compassion appropriately, officers are expected to exercise good judgment in terms of preventing, de-escalating, or resolving conflict, gaining compliance, and solving problems using the least amount of force necessary.

Notwithstanding these expectations, interacting and communicating with community members in a manner that is both effective and fair is a challenge for many officers. Often, community members voice their dissatisfaction with these encounters, with complaints ranging from verbal to physical abuse. Negative public attitudes toward the police stemming from negative encounters are well documented (e.g., Brown and Reed Benedict 2002; Skogan 2006a; Tuch and Weitzer 1997). Research indicates that factors such as the officer’s perceived demeanor, fairness and impartiality, concern, helpfulness, conflict resolution strategies, and professional competence all play a role in determining residents’ level of satisfaction with police encounters (e.g., Cheurprakobkit and Bartsch 2001; Skogan 2006b; Tyler 1990; Tyler and Huo 2002; Wortley et al. 1997).

This same research has uncovered a substantial racial divide, with African-Americans and Latinos reporting less satisfaction than whites with the treatment they receive from the police (e.g., Weitzer and Tuch 2002). Indeed, recent street protests and the social justice movements (e.g., Black Lives Matter) have drawn attention to the mistakes made by police officers. While police use of force occurs in only 1.6% of police contacts in the USA (Hyland et al. 2015), nearly 1000 people die each year from police actions (Washington Post 2017). Furthermore, large cities face thousands of complaints each year regarding excessive force (Hickman 2006) and pay out millions of dollars in misconduct settlements and court judgments (Elinson and Frosch 2015). More commonly, citizen complaints involve police abuse of authority (e.g., bias in stop and search decisions), discourtesy, and offensive language (Dugan and Breda 1991; New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board 2013).

The widespread perception that police are disrespectful or unfair during encounters can have serious consequences for public safety. As numerous police scholars and police chiefs have observed, the police rely on the support and voluntary cooperation of the public to achieve their goals of preventing crime and disorder and administering justice (Rosenbaum 1998). Extensive research indicates that this public support and cooperation are undermined when the community does not view the police as legitimate authorities (Mazerolle et al. 2012b). Stated in positive terms, when the police are seen as exercising their authority in a legitimate manner, the public is more likely to comply with police directives (McCluskey et al. 1999; Tyler 1990, 2004; Tyler and Fagan 2008; Tyler and Huo 2002), obey the law (Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Huo 2002), and work with the police to report crime and engage in crime prevention behaviors (Murphy et al. 2008; Tyler 2004). At the most basic level, public compliance with police requests, whether it be as simple as stepping back from a crime scene or providing information about possible suspects, is essential for maintaining order and solving crime. Going a step further, the use of force by the police is often the result of non-compliance or resistance by community members during an arrest (Adams 2004), so the effects of weak legitimacy are multiplicative.

This begs the question, how can the police achieve greater legitimacy with the public? A large body of research in many countries indicates that one of the main drivers of police legitimacy is whether the officers treat community members in a respectful and fair manner, called “procedural justice” (Gau and Brunson 2010; Jackson et al. 2012a, b; Mastrofski et al. 2002; Myhill and Quinton 2011; Skogan 2005; Tyler 2006). Police–community interactions that are viewed as procedurally just produce greater public satisfaction with the encounter and with the outcome (Mastrofski et al. 1996; McCluskey 2003; Tyler and Fagan 2008; Wells 2007). Even domestic spouse abusers will be less likely to reoffend if treated in a procedurally just manner (Paternoster et al. 1997).

Procedural justice includes at least three core elements: citizen participation or voice in the process prior to police decisions, neutrality or fairness in police decision-making, and treating the community member with dignity and respect (Tyler 2004). The officer’s trustworthiness is also important (often included as a fourth component of procedural justice). We maintain that, while these elements are essential for good communication, they are only part of a more complex set of factors at work in human interactions. Additional factors, such as empathy and compassion (Eisenberg and Miller 1987), emotional intelligence (Mayer et al. 2007), humor (Christoff 2016), and non-verbal behaviors (Tannen 2007), can also influence the quality of the interaction, and, thus, the community member’s overall satisfaction and response. To our knowledge, the Chicago QIP was the first attempt to train new recruits in procedural justice and expand the model to incorporate some of these additional communication factors.

Police training

As we have observed as a nation, one of the greatest challenges facing the police in a democratic society is how to maintain order and administer justice without jeopardizing the public’s trust or civil liberties. At the individual level, the challenge is how to achieve desired outcomes without resorting to tactics that could undermine one’s authority as a police officer, violate civil liberties, escalate conflict, or result in injury or death. Police training is a critically important domain where police agencies have the opportunity to strengthen officers’ interpersonal skills during encounters. National data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, however, indicate that training academies in 2013 devoted the vast majority of training hours to firearms skills, self-defense, physical fitness, patrol tactics, and investigations, giving very little attention to basic strategies of community policing, cultural diversity, human relations, mediation skills, and other communication skills (Reaves 2016). This imbalance in subject matter virtually guarantees a lack of social proficiency in routine police work and runs the risk of officers using force that could threaten their careers, lead to costly law suits, and further jeopardize the legitimacy of the police as an institution.

In light of public dissatisfaction with the way they are treated by the police, some training programs have sought to bolster police legitimacy by focusing on community policing (Kaiser 1995; Skogan and Hartnett 1997), cultural diversity (Harrington 2002), and leadership (Berringer 2004). However, our knowledge of training effectiveness in these areas is very limited due to the absence of controlled evaluations.

Police have also been criticized for mishandling encounters with special populations. Hence, we have seen a growth in police crisis intervention training over the years to address a variety of problems, including domestic disturbances (Buchanan and Perry 1985; Driscoll et al. 1973), hostage negotiations (Van Hasselt et al. 2008), mental health (Barocas 1971), and a variety of police encounters (Mulvey and Reppucci 1981). The expectation is that such training will enhance officers’ skills in crisis management and, thus, reduce their reliance on force and arrest (Hails and Borum 2003). Overall, the evaluations of legitimacy and crisis training show positive effects on officers’ attitudes and intentions, but few have assessed the impacts on community members (see Bennett et al. 2014).

Recently, many departments have introduced the “Memphis” model of crisis intervention to teach de-escalation and situational management as alternatives to using force when responding to persons having a mental health crisis (DuPont et al. 2007; Watson et al. 2008). Training for Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) has been recommended by the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015: 56) and is widely adopted today. CIT involves 40 hours of training and employs a range of teaching methods, including lectures, videos, and role-playing. Evaluations of CIT have shown improvements in officers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding mental illness (Compton et al. 2014a), but little research has been done on actual behavior. There is some evidence that CIT training reduces use of force as resistance increases (Morabito et al. 2012) and is associated with increased transports for emergency psychiatric services (Watson et al. 2011), but mixed evidence that the training has any effect on officers’ arrest decisions or on patient outcomes, such as re-arrest or hospitalization (Compton et al. 2014b; Steadman et al. 2000; Teller et al. 2006; Watson et al. 2011). Only a few of the studies on CIT involve quasi-experimental designs, utilizing a control group, and no randomized trials have been reported (see Marotta et al. 2014 for a review).

Related to CIT, we maintain that police need substantially more training on interpersonal communication around procedural justice principles and other micro components of human interaction. Existing training has been too general. Cultural awareness training, for example, has sought to improve police–community relations through general knowledge of diverse groups, but these efforts generally do not target specific behaviors and have not been well received by officers. “Verbal judo” training (Thompson 2013) has been widely adopted and does focus on verbal behaviors, but does not adequately address the community member’s need for fairness, or the complexity of human interaction, nor are we aware of any rigorous evaluations of its effectiveness. The new Fair & Impartial Policing training program (Fridell 2016) is helpful for allowing officers to acknowledge implicit biases that we all share about various segments of society, but is not easily transferable into social interaction skills that can correct this unconscious problem and has yet to be rigorously evaluated.

Despite a massive literature showing that procedural justice by the police has a substantial impact on police legitimacy, very little of this work has been translated into training, and the evaluations of existing procedural justice training are generally weak or non-existent (see Wheller and Morris 2010). Only recently has training in procedural justice started to take shape in the USA. The QIP initiative reported here was the first program in the USA to translate procedural justice theory into police training, and then go further to incorporate other aspects of human interaction. The QIP led to the development of procedural justice in-service training in Chicago and has been the springboard for a wide range of procedural justice training programs in the USA, including the National Initiative for Building Community Trust in six pilot cities, as well as procedural justice training initiatives now available to hundreds of agencies via the Office of Community Oriented Policing and the Office of Justice Programs. Despite this rapid growth in procedural justice training programs, the scientific evidence regarding effectiveness remains relatively weak (Lum et al. 2016).

Chicago’s QIP training for recruits was used as a foundation to build a one-day in-service program for all Chicago officers in 2013 and 2014. Using a quasi-experimental design, Skogan et al. (2015) found that officers who participated in the program were more likely than controls to endorse the importance of four procedural justice principles (voice, respect, neutrality, and trust) immediately after training, and three of the four attitudinal effects persisted roughly six months after officers returned to their daily work. However, the follow-up results should be interpreted with greater caution because they are not linked to training participants and may reflect selection bias in who chose to participate in the training.

With the introduction of a single police force in Scotland in 2013, a 12-week version of the QIP, called the Scottish Police and Citizen Engagement (SPACE) Trial, was introduced for new recruits that gave attention to procedural justice and communication skills. A quasi-experimental evaluation of the training (Robertson et al. 2014) found that training had a positive effect on four of eight communication measures, but an unexpected negative effect on respect measures. While Scottish probationary officers valued communication skills, anecdotal evidence suggested that they dismissed procedural justice as not “core policing” and discounted empathy skills as something that “could compromise professionalism” (Robertson et al. 2014: 8–9). Behavioral performance during role-playing was unaffected by the training.

The gold standard in evaluation research is the randomized control trial (RCT), but this is rarely done in police training and procedural justice training in particular. An RCT was introduced with Detroit police recruits in 1986 to increase their sensitivity and responsiveness to crime victims during preliminary investigations (Rosenbaum 1987), a partial test of procedural justice. The evaluation found that the experimental group outperformed the control group by the end of basic training, showing positive changes in attitudes and behavioral intentions with regard to compassion and responsiveness to victims. However, telephone interviews with victims roughly four months after the training showed no differences between the experimental and control groups in terms of victims’ emotional state, fear, feelings of vulnerability, and crime prevention behaviors.

Two recent RCTs stand out as direct tests of procedural justice training. Mazerolle and her colleagues (Mazerolle et al. 2012a, 2013) conducted the Queensland Community Engagement Trial involving the Queensland Police Service in Brisbane, Australia, where officers were trained in “legitimacy policing” to improve their performance during roadside stops involving random breath tests. This RCT required officers in the experimental group to follow a script with drivers that covered some key elements of procedural justice, while officers in the control group engaged in business as usual. Survey results from drivers indicated that the legitimacy script increased their perceived satisfaction with the encounter, fairness, respect, trust, and confidence with regard to the police, as well as their willingness to comply with police directives. MacQueen and Bradford (2015) sought to replicate the Queensland study in Scotland without success, and, in fact, found that trust in the officer and satisfaction with the encounter declined significantly relative to controls in this RCT. A follow-up study using focus groups suggests that the adverse effects were due, in part, to a lack of organizational justice within the agency that would be needed to create receptiveness to such reform (MacQueen and Bradford 2016).

Going beyond reading scripts about procedural justice, the Greater Manchester Police Service sought to employ multiple training techniques and give attention to aspects of police–community encounters overlooked in procedural justice training, namely empathy and interpersonal communication skills (Wheller et al. 2013). The Greater Manchester RCT was influenced by the Chicago QIP and used much of the content and methods employed in Chicago, including role-playing, videotaping, and feedback to constables in the training. The Greater Manchester RCT, which provided 14 hours of in-service training in 2011 and 2012 to a randomly selected sample of more than 500 officers, found positive training effects on four of eight attitudinal dimensions (the perceived impact of training, attitudes toward delivering quality of service, building empathy and rapport, and having fair decision-making). Victims also reported slightly more procedural justice during their interaction with trained officers, but their willingness to cooperate with the police was unaffected. On the whole, this work underscores the importance of building empathy and rapport with victims, as proposed by the QIP.

These studies are extremely rare and focus primarily on procedural justice. With the exception of the Scotland SPACE training and the Greater Manchester training, police training around interpersonal interaction has been superficial, lacking theoretical or empirical justification, and failing to provide officers with practical skills or habits for policing on the streets. A new training program called “T-3” (Wender and Lande 2015) shows promise to overcome these deficiencies, but has yet to be rigorously evaluated.

Methods of training

As suggested earlier, a core problem with most police training is not simply the content but the mode of delivery. Anecdotal observations of training in several cities has led us to believe that most training is delivered like academic education, by “talking heads” at the front of the classroom, using PowerPoint, lectures, and “war stories” (see Ford 2003). According to experts, adult education should focus on making the learning process relevant to the lives of students, respectful of their experiences, and participatory (e.g., Vella 2002). More specifically, research on adult education suggests that the mastery of skills and a deeper understanding of concepts can be achieved through problem-based learning (with real-world problems and cases), experiential practice (with scenarios and role-playing), varied repetition of desired behaviors, and immediate feedback regarding performance success at the individual level (see Entwistle et al. 2010). The QIP tried to move in this direction and go beyond the lecture modality, as described below.

The present study

The QIP initiative provided a genuine opportunity, through recruit training, to grow a new police culture that endorses key values and principles regarding human interaction and seeks to solve interpersonal problems in a way that reinforces this orientation. Developed jointly by the Chicago Police Department and the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2010, the QIP was the first known demonstration and evaluation of procedural justice training in the classroom and the first to focus on developing interpersonal skills among police recruits. This was a strong police–university partnership, but it experienced several bumps in the road, including difficulty in convincing the department’s legal counsel that the merits of an RCT outweighed the risk of lawsuits stemming from officers in the control group “not being properly trained.”Footnote 1

The new QIP curriculum was constructed within a community-oriented procedural justice framework that gives primary attention to the quality of police–community encounters. It was strongly evidence-based, derived from diverse research in multiple disciplines. It emphasized how tasks are performed during encounters (procedural justice) and how officers communicate and make decisions in light of the needs of crime victims and other community members. The curriculum also emphasized non-traditional, adult pedagogy. In contrast to the “talking heads” approach, training in firearms and self-defense has always involved scenarios, simulations, and repetition to achieve proficiency. As noted earlier, educational scholars recognize the importance of student–instructor interaction to maximize interest and learning, especially in adult education environments. Also, repetitive practice is an effective approach to training. Recruits need opportunities to practice behaviors during interpersonal encounters.

Critically important to effective education and training is feedback and improvement in performance at the individual level. If training instructors do not have a good sense of the level of interpersonal skill possessed by individual recruits, feedback at the individual level is not possible. Thus, instructors need to be armed with knowledge of individual performance if they intend to provide guidance to students who are struggling to reach some level of proficiency.

Through the National Police Research Platform, a program designed to advance knowledge and practice in American policing (Rosenbaum 2017), we designed the present study to explicitly test the impact of procedural justice training on officers’ attitudes and behaviors in an RCT. Treatment and control groups were assessed through responses to self-reported questionnaires as well as research-coded videos that recorded officers during role-playing scenarios. Compared to the control group, we hypothesized that officers receiving the QIP training would report higher levels of respectful attitudes, supportive behaviors, and non-aggressive decision-making when intending to interact with community members. Our main research questions included whether or not the experimental treatment could alter views and role-playing behaviors of new police officers.

Methods

QIP training methods and materials

The QIP training model draws upon behavioral research across multiple disciplines to construct evidence-based training (e.g., research on adult education, interpersonal communication, procedural justice, race prejudice and profiling, multicultural studies, human perception, criminal justice processes, conflict resolution, emotional control, and stress management). The QIP developers sought to identify the optimal interpersonal skills needed by police officers for different types of encounters. As noted earlier, procedural justice theory and research (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler 1990) provided a valid framework for understanding police–community encounters, as people’s judgments about the legitimacy of the police are based largely on their sense of the fairness of the process and the quality of treatment. Thus, recipients of police service should be more satisfied and cooperative when they have a voice in the process, feel they are treated with dignity and respect, feel the officer was fair and impartial, and feel the officer was genuinely concerned for their welfare. An attempt was made to incorporate these elements of police behavior into the training program. Prior research on police encounters supports this decision.

Theories of victimization, stress, and recovery also guided the development of the QIP. Too often, victims of violence experience negative, unsupportive reactions from professionals, which have been shown to inhibit their psychological recovery and reduce the likelihood of future disclosure or reporting to authorities (Ahrens 2006; Starzynski et al. 2005; Ullman 1999). Ullman (2000) identifies four key dimensions of negative social reactions to victims (i.e., taking control of the victim’s decisions, victim blame, distraction from what happened, and egocentric behavior) and three aspects of positive reactions (i.e., instrumental, emotional, and informational support). This implies the need for officers to be particularly sensitive to the needs and concerns of victims when responding to calls and taking police reports (cf. Rosenbaum 1987).

The curriculum also incorporated research on stress management, conflict resolution, emotional intelligence, and cognitive behavioral therapy. These dimensions were integrated into the procedural justice framework to address the influence of emotion on officers’ interpersonal skills and decision-making when interacting with the public. The social function of emotion is to “…mobilize the organism to deal quickly with important interpersonal encounters” (Ekman 1992: 171). Emotion exerts influence on communication and decision-making by: (a) carrying information that is used as input (i.e., feelings as information; Schwarz and Clore 1983); (b) influencing key cognitive processes (i.e., selective attention, prejudicial biases, and perceptions of risk and evaluations of value; Tiedens and Linton 2001); and (c) overwhelming the individual, thus impeding his/her ability to engage in a deliberative decision-making process (Loewenstein 1996). In addition, research suggests that one person’s emotional state influences another person’s emotional state through the mechanisms of evoking complementary emotions and/or operating as an incentive for reinforcing the other’s behavior (Morris and Keltner 2000). Officers’ emotions not only affect their skills and decisions, but they also influence community members’ responses to their requests. The literature on work stress (Dewe et al. 2010) and police stress in particular (Gilmartin 2002) suggests that burnout and cynicism can occur and will likely damage interpersonal relations. The QIP curriculum addresses this problem.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to be effective in reducing negative behaviors (Butler et al. 2006). Some of the key elements of cognitive behavioral therapy include the assumption of a causal link between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, an emphasis on the learning process, and cognitive activities, including pre-event expectations, post-event attributions, and self-talk (Kendall and Braswell 1993). By integrating elements of cognitive behavioral therapy into the program, the training attempted to address some of the barriers to using appropriate interpersonal skills consistently. Officers were encouraged to interpret and control their thoughts and emotions with internal self-statements and other tools. They were trained to respond in a fair and respectful manner in all encounters, including situations where they may be stressed, angry, or overwhelmed.

The QIP begs the question: what are we seeking in new police officers and how do we achieve that goal? Traditional police scholars have argued that police work is all about the use (and misuse) of coercive force (e.g., Bittner 1980), hence the current focus of training academies on physical agility–physical fitness, driving, use of force, and self-defense. In contrast, community policing scholars, beginning in the 1980s, have argued that the police are primarily in the business of providing high-quality services to community members, preventing crime, and engaging community members in the “co-production” of public safety (Rosenbaum 1994; Skogan 2003). If we accept this community model, then a new set of skills should be taught at the academy that focus more on interpersonal communication, multicultural sensitivity, leadership, decision-making and problem-solving, ethics and integrity, constitutional rights, procedural justice, and responsiveness to the needs of crime victims and others in the community. The process of policing “for the people” (Mastrofski 1999) is given a higher priority under this community model.

The reality is, perhaps, more complex than either of these positions suggest. Municipal police are expected to fulfill a wide range of functions, including preventing crime, helping crime victims and others in danger, keeping the peace, protecting constitutional guarantees, managing the movement of people and vehicles, resolving conflicts between parties, creating a feeling of safety in the community, and providing a host of other services (see Goldstein 1977). However, the QIP initiative was based on the assumption that, in virtually all of these mandates, the interpersonal skills of the officer are essential. Even the decision to use physical or deadly force can reflect a “failure to communicate” in less dramatic or consequential ways. Hence, the QIP initiative gave more attention to the development of general interpersonal skills, which should ultimately reduce the risk of officer or civilian injury, promote mutual respect, and resolve immediate problems.

Experimental intervention

The primary training objective was to develop a program that would increase the quality of police–community encounters by increasing officers’ skills during these events. The QIP added approximately 20 hours of new material to the larger curriculum. It was evidence-based, community service-oriented, and integrated with other courses. In addition, it included individualized feedback and allows for student engagement, practice, and repetition.

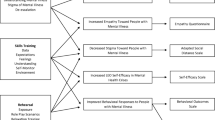

The present study examines hypothesized changes among new recruits at the completion of the six-month training period. The QIP training was designed to instill more respectful and supportive attitudes, behavioral intentions, and actual behaviors among recruits with respect to police–community contacts; to increase their communication skills; and to encourage better decision-making and problem-solving in these settings. The training was designed to increase officers’ skill by incorporating five key components into existing and new training modules. Table 1 details the key components of the QIP training.

Curriculum development

Curriculum development followed a modified ADDIE model of instructional systems design (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate with rapid development; Jones and Richey 2000; Piskurich 2000) and incorporated proven adult education strategies, such as modeling, repetitive practice, individualized feedback (Moses 1978), and learning styles (i.e., verbal, visual, logical, intrapersonal, interpersonal, music, kinesthetic, and existentialistic; Gardner 1999).

Various resources were marshaled in order to develop an effective training program: (1) personnel were assigned to oversee, coordinate, and manage the project; (2) instructors and supervisors from the academy participated in workgroups designed to develop, implement, and evaluate the new training program; and (3) staff videotaped all recruits as they engaged in role-playing scenarios to allow individualized feedback to the trainees.

Training academy personnel and researchers participated in workgroups tasked to design, implement, and evaluate the new training curriculum. The workgroups first identified current curriculum modules where key components can be inserted and then adapted those modules as needed. Second, the new training modules were developed and components were tested as needed. Third, a training program for instructors was developed that trained instructors to teach the new program. Finally, a quality control program was developed to measure indicators of success and an overall evaluation plan. To maximize learning and retention, the QIP engaged the students and challenged them through a sequence of methods (cf. Moses 1978):

-

Modeling: Trainees observe filmed, videotaped, or actors performing a task or dealing with a problem;

-

Rehearsal: Trainees practice the behavior frequently;

-

Feedback: Trainer and other trainees provide feedback on the rehearsed behavior.

To achieve this type of individual engagement, several teaching methodologies were used, including case studies (business school model), scenarios, role-playing, and simulations. In theory, the more opportunities students are given to read it, hear it, see it, discuss it, discover it, solve it, or experience it, the greater the probability of learning and retention.

One of the central tasks in the curriculum development process was the development of verbal scripts appropriate for various encounters, as well as scripts that would be inappropriate and should be avoided. Different sets of scripts are needed for different types of encounters. The notion of scripts was central to the QIP curriculum as conceived. As one instructor noted (half-jokingly), officers typically use many different versions of a single script on the streets, namely, “We can do this the easy way or the hard way—which will it be?” Unfortunately, threat often leads to counter-threat rather than compliance (Limberg 2008). Thus, a decision was made that new officers could benefit from having a more diverse repertoire of verbal statements that can be used in different situations.

Trainees and instructors in the experimental group developed verbal scripts that were guided by research on procedural justice, social support, customer satisfaction, and other areas of social interaction. For example, research on social support and “emotional work” points to the importance of having empathy and showing compassion during encounters with persons who are upset or distressed by adverse experiences. The key subprocesses involved in “compassion” are noticing the person’s suffering, feeling the person’s pain, and responding in some way to help correct the situation (Kanov et al. 2004; Miller 2007). Hence, noticing and feeling scripts might include statements such as, “I can see that you are upset by what happened,” “I’m sorry this happened to you”, or “I’ve been through this myself, so I know the feeling.” Acknowledging the victim’s feelings and expressing empathy were considered important objectives behind the task of script development. This task was considered especially important for young officers who do not “naturally” display these social interaction skills or who needed additional reinforcement and practice.

Negative scripts to be avoided include blaming the victim and paternalistic statements (e.g., “Why were you out at 2 AM—what were you thinking?”). Officers in one district assisted the project by developing a list of negative scripts, based on their own experiences. These negative scripts, used in the field, reflect the stereotypes present in the police culture. Some of them were used in the new curriculum for “inoculation training” to illustrate what not to do. Conversely, a new set of positive scripts was developed by students in the experimental group, which they practiced delivering and were encouraged to use in role-playing.

Instructors were trained in the new curriculum. Part of the instructor training focused on creating a culture where integrity of the message, using the right tone and appropriate pedagogy, is critically important. Instructors were sensitized to the fact that they can sometimes send mixed messages to the recruits, and, consequently, undermine their own training objectives. Instructors were also trained in the professionalism of teaching and the importance of role-modeling, including starting and ending class on time, treating every student with dignity and respect, evaluating students using fair and objective standards, etc.

The curriculum began with a core four-hour period during which recruits were exposed to lectures, videos, and role-playing scenarios led by two instructors: one police officer and one university professor. Key concepts discussed included procedural justice, communication skills, decision-making skills, cultural awareness, and stress management. The instructors used three case studies to help recruits determine how to communicate and resolve conflict in diverse interpersonal situations, ranging from neighbors fighting over a parking space to working with a partner who is being verbally abusive to a community member.

The new four-hour block was introduced in the first month of their six months at the training academy, giving them more time to practice scripts and role-playing. This curriculum was also integrated into several existing classes that focused on the handling of property crimes, personal crimes, and domestic violence. In smaller groups, students were exposed to role-play scenarios, where “beat officers” (recruits selected from the class) were asked to conduct a preliminary investigation with a “victim” or “witness” to a property or personal crime. The initial role-player (victim/witness) was previously instructed to remain upset until the officer used certain scripted language to either acknowledge the victim’s feelings or expresses empathy (e.g., “I understand…” or “I’m sorry…”). During and after these scenarios, the class was asked what other questions should be asked and what else needs to be done to properly finish the investigation.

In addition to group exercises, practice of new skills and individualized feedback were important components of the program. Each student in the program participated in a role-playing scenario around a domestic violence incident (including a violation of an order of protection and an angry victim) and many of these sessions were videotaped, followed by individualized feedback from instructors. Students were encouraged to use the verbal script they had developed during their role-play encounter with the victim.

The individualized feedback program required instructors to review the tapes, note areas where improvement was needed, and prepare comments for a one-on-one feedback session. Structured feedback was given on key aspects of procedural justice (e.g., voice, neutrality, respect, intentions), emotion control (keeping cool and not getting frustrated), and resilience (helping them reduce stress). Instructors used the taped performance to identify positive examples of good communication skills and other examples that should not be used (e.g., blaming the complainant, using condescending or sarcastic language). Safety tips were also covered. Instructors were encouraged to model good interpersonal communication at all times. Finally, instructors for the treatment group were expected to integrate and reinforce the concepts during six “homeroom” classes over the course of several months.

RCT procedure and sample characteristics

The study was an RCT. Prior to starting the academy, recruits were matched on gender, race, age, and prior military background, and then randomly assigned to the standard academy curriculum or the training condition. Recruits in the control condition received the standard academy curriculum, which did not include topics covered in the QIP training. Recruits in the training condition received the standard curriculum for all classes except the QIP training. As detailed above, the QIP classes incorporated research on stress management, conflict resolution, and cognitive behavioral therapy. These dimensions were integrated into the larger procedural justice framework to address the influence of emotion on officers’ interpersonal skills and decision-making when interacting with the public.

A total of 142 recruits participated in the RCT. The demographic distribution was 72% male, 44% white, 25% African-American, and 29% Latino. The average age was 28 years. The majority of the recruits were single and less than a quarter served in the military prior to joining the police department. Most of the recruits reported having at least a college degree. More than one-third reported being bilingual, with Spanish as the most commonly reported second language. There were no statistically significant differences between the control and training groups in terms of participant demographics (see Table 2), thus confirming the effectiveness of the random assignment process.

Self-report questionnaires were administered prior to training and at the conclusion of training (six months later) for both experimental and control groups. These survey-based attitudes and behavioral intentions were supplemented by direct observations of recruits’ behavior during role-playing scenarios. A portion of the recruits in both experimental and control groups were videotaped at the beginning and end of their six-month training period as they interacted with scripted complainants who had called the police for assistance.Footnote 2 These videotapes were scored by graduate students not affiliated with the training and “blind” as to the experimental conditions. Each item of the officer’s recorded role-playing scenario was rated by one to four graduate students (mode = 3) using three-point response scales. The raters’ responses on each item were averaged to create a single stable score for each trainee. The measures obtained from both the surveys and observations focused on dimensions of procedural justice and emotional control during encounters. They are discussed along with the results in the following section.

Due to a lack of resources, only a subsample of the recruits was videotaped at the pretest (n = 70, 34 in treatment condition, 36 in control) and, due to attrition in this component of the study, this subsample was further reduced at the posttest (n = 38, 15 in treatment condition, 23 in control). This subsample introduced the possibility of differential attrition across experimental conditions, so Chi-square analyses were run to test for differential attrition. There were no significant differences in the demographics between the experimental and control group members who were videotaped for both the pretest and posttest scenarios (sex: χ2 = 0.169, race: χ2 = 0.406, education: χ2 = 0.865, marital status: χ2 = 0.375, prior military service: χ2 = 0.337, bilingual: χ2 = 0.618, age: t = 1.126; all with p > 0.05). Independent sample t-tests on each of the outcome measures also indicated that this subsample was not statistically different from the sample of officers who were not videotaped, with the exception of force.Footnote 3

Results

Respectful attitudes toward police–community member encounters

We hypothesized that recruits exposed to the QIP would place a greater value on being respectful during police–community member encounters and controlling their own emotions than recruits in the control group. Each item was coded on a five-point scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = disagree, 5 = strongly disagree). The Respect Toward Community Members Index was comprised of the following items: (1) All people should be treated with respect regardless of their attitude (reverse), (2) It is OK to be rude when someone is rude to you, (3) Being respectful is nearly impossible when you are dealing with a gang member, (4) Officers can’t be expected to keep their emotions in check when people are disrespectful, and (5) The time that officers spend chatting with average citizens could be better spent investigating crime and suspicious situations. Descriptive statistics of all scales are presented in Table 3. Scale unidimensionality and reliability were assessed using separate principal components factor analysis and the Cronbach alpha statistic for each set of items within the scales. Each scale was created by averaging the items and scales were only calculated for respondents who answered half or more of the items used in the scale.

A generalized linear model (GLM) repeated measures analysis was performed in SPSS to estimate program effects over time. GLM provides an analysis of variance that allows for hypothesis testing for both between-subjects (experimental group) and within-subjects (time) effects. The time-by-group interaction term captures the treatment effect, as it tests for differential change between the treatment and control groups over time. As shown in Table 4, a significant effect was found for the time variable, indicating that respectful attitudes toward community members declined between time 1 (start of training) and time 2 (six months later) for both training and control groups. However, no treatment effect was found on this index.

Respectful and supportive behavior during police–community member encounters

We hypothesized that officers exposed to the training would exhibit more respectful and supportive behaviors during a role-playing encounter than officers in the control group. As noted earlier, for a smaller sample of recruits, we videotaped their actual performance during role-playing scenarios and coded their behavior. Six different variables were coded by blind observers to capture respectful and supportive behaviors toward the actors. These included whether the officer: (1) apologized to the victim for what happened, (2) acknowledged the actor’s feelings and concerns, (3) made reassuring or empowering statements, (4) had a courteous demeanor, (5) had a friendly demeanor, and (6) was reassuring and efficacious. Response options included 1 = no/never, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = yes/often, with a higher score on this index indicating greater respect toward the individual.

Due to the fact that two actors were present during the posttest homeowner/parker scenario, new variables were created by averaging the recruits’ scores on the above items between actors. This is justified since the observers’ ratings of the recruits’ behavior toward the two actors were very similar, with Pearson r-values for each of the six dimensions ranging from 0.65 to 0.88, all less than the 0.001 significance level.

The GLM repeated measures analysis (see Table 4) provides support for the treatment hypothesis. Over time, recruits in the experimental group were significantly more likely than the control group to display respectful and supportive behavior during encounters with a live actor. In terms of net changes, the experimental group showed a small decrease in the amount of respectful and supportive behavior over time, while the control group showed a sizeable decline on this index.

Procedural justice behavioral intentions during traffic stops

A series of questions were developed to evaluate recruits’ perceptions of the importance of procedural justice practices when conducting a traffic stop. Recruits were given the following scenario: “An officer has just pulled over a driver who committed a traffic violation. The driver did not come to a full stop at a stop sign.” Recruits were then asked to determine how much priority they thought should be placed on a list of specific procedural justice behaviors using a five-point response scale, where 1 = a very low priority and 5 = a very high priority. We hypothesized that the training should increase the priority that recruits place on procedural justice practices.

The Quality of Treatment Index, composed of six items, was designed to capture procedural justice behavioral intentions, as well as emotional supportiveness. The following items were included in this Quality of Treatment Index: (1) Be respectful when dealing with the driver, (2) Stay calm even if the driver yells at you, (3) Acknowledge the driver’s feelings, (4) Let the driver tell his or her side of the story, (5) Try to answer all the driver’s questions, and (6) Explain the process for paying the tickets or going to court. A higher score on this index indicated that the officer intends to have a higher priority on their quality of treatment during traffic stops.

The GLM repeated measures analysis does not support the treatment hypothesis (see Table 4). Furthermore, all recruits placed significantly less, not more, emphasis on the quality of treatment during traffic stops from time 1 to time 2.

Communication skills and emotional intelligence

We hypothesized that recruits exposed to the training program would show improved communication skills and emotional intelligence relative to controls. An index was created that reflects both communication skills and emotional intelligence. The latter indicates an ability to read, understand, and respond appropriately to emotions in others and oneself. Recruits were asked to evaluate their communication skills by indicating whether they agreed or disagreed on a four-point scale (1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree) with the following eight statements: (1) I know how to talk with people, (2) I know how to resolve conflict between people, (3) I have good communication skills, (4) I know how to make someone comfortable, (5) I feel confident when using my communication skills, (6) I am good at reading other peoples’ emotions, (7) I know how to show empathy or compassion, and (8) I know how to use nonverbal cues to communicate my feelings to others.

The results from the GLM repeated measures analysis do not support the program hypothesis, presented in Table 5. Students in the training group did not show significant improvement in their communication skills or emotional intelligence at the end of the academy relative to the controls. If anything, these skills declined slightly in both groups, although the change was not significant.

Attitudes toward the use of force

We hypothesized that recruits exposed to the QIP would place less value on using force during police–community encounters. Several questions were used to measure the officers’ attitudes toward using force during encounters. Each item was coded on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). A single Use of Force Index was identified comprising the following items: (1) Police officers should use force more often to get citizens to comply, (2) Use of force should be the last resort for police officers (reverse), (3) Police officers are often in situations where it is more appropriate to use physical force than to keep on talking to a person, (4) Some people can only be brought to reason the hard, physical way, (5) A tough physical approach should be used less on the street (reverse), (6) Sometimes, forceful police actions are very educational for civilians, and (7) If officers don’t show that they are physically tough, they will be seen as weak.

The results from the GLM repeated measures analyses do not support the program hypothesis. Students in the training group did not show significant improvement in their views toward use of force at the end of the academy relative to the controls. In fact, the desire to resolve situations with force increased significantly for both groups during their time at the training academy, practically at the same rate (see Table 5).

Decision-making and problem-solving skills

We hypothesized that recruits exposed to the training program would exhibit better decision-making and problem-solving skills than recruits in the control group. Recruits were presented with a scenario to measure their decision-making and conflict-resolution strategies. The training program emphasized the importance of conflict-resolution skills and the use of force or arrest as last resorts when other strategies have failed. Students in both groups were presented with the following scenario for measurement purposes:

As an officer, imagine that you are sent on a call to investigate a group of youths “hanging out” in the park. You arrive on the scene and ask the youths to go home. At first, they refuse and start goofing around and calling you names. Listed below are some methods that might be applied to dealing with the above situation. Some methods may be more effective than others, while some methods may be more appropriate than others. On a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 10 (Very), please rate how effective and appropriate each of the methods would be for dealing with the situation.

We hypothesized that the training would impact recruits’ perceptions of the appropriateness of specific conflict-resolution strategies. Recruits who participated in the training were expected to rely more often on mediation and diffusion and less often on physical force and arrest than recruits who did not participate in the program. Two outcome measures were tested representing these divergent strategies: The Aggressive Enforcement Index included two items they could endorse as appropriate: “Use physical force to get the youths to leave and go home” and “Arrest all of the youths”. In contrast, a single item was used to measure a non-aggressive strategy: “Attempt to diffuse the situation by telling the kids they did not have to go home, but leave the park”.

The results for the GLM models are presented in Table 6. The training program yielded positive results in this youth scenario for both outcome measures. Relative to controls, the recruits in the training group were significantly less likely to rely on aggressive enforcement (force and arrests) to solve the youth problem. They were also significantly more likely than controls to want to “diffuse the situation” by giving youths the option of leaving the park without further intervention.

Discussion

The QIP was one of the first systematic attempts to develop and test evidence-based training to improve how new police officers interact with the public. The program, started in 2010, was instrumental in guiding future procedural justice training programs. The findings from this RCT are promising, but mixed. The program did not appear to impact recruits’ attitudes about showing respect or procedural justice during encounters with community members, nor did it alter their self-reported interpersonal communication skills. However, for recruits that were videotaped, the program appears to have been effective at increasing respectful and reassuring behavior during role-playing encounters. Based on ratings from independent “blind” observers, recruits in the experimental group were more inclined than controls to engage in the desired verbal behaviors, such as apologizing for what happened, acknowledging the actor’s feelings and concerns, being courteous, and making reassuring statements. Regardless of the recruits’ true attitudes and internal feelings, these verbal statements may be a direct reflection of the scripts that they developed and rehearsed.

This raises an important question about whether external changes in officers’ behavior must be accompanied by internal changes in attitudes or feelings, or whether it is sufficient that the victim/complainant hears these statements. That is a question for future research. We also recognize that the use of scripts is a controversial subject. Scripts may oversimplify social behavior and not be applicable to many encounters that the police face. However, we maintain that scripts, when combined with role-playing, provide a solid starting point for young officers who are uncertain about how to act or what to say and need to practice their communication skills.

The QIP also had a significant positive impact on recruits’ decision-making regarding conflict resolution with youths. Many researchers and practitioners argue that good decision-making on the job is at the core of good policing and good police administration (Cordner and Scarborough 2010). When responding to a rebellious youth scenario, recruits in the training group felt more comfortable attempting to diffuse the problem of youths hanging out in a park than did the control group. Furthermore, the training group was less inclined to resort to aggressive enforcement to solve the problem, including using physical force and/or arresting them. Given the importance of good judgment in the exercise of police discretion, especially with youths, these findings are important. Whether these behavioral intentions will translate into actual behavior in the field remains to be seen.

The impact of the QIP on respectful attitudes and communication skills may have been limited for several reasons. First, the opportunities to rehearse or practice new behaviors or to be given immediate feedback on performance at the individual level were limited, despite the use of innovative materials and methods. Verbal feedback after role-playing scenarios was provided during the first week of training, but most individualized scenario-based feedback during basic training was focused on officer safety and departmental policies and procedures, rather than the quality of encounters. More frequent videotaped feedback was planned, but was judged to be too costly. Second, the dosage of treatment was estimated to be less than 20 hours of class time, embedded in a curriculum that included more than 1000 hours devoted to other topics. Instructors were encouraged to reinforce the concepts during a one-hour “homeroom” at the start of the day. Observations and feedback from instructors suggest that this reinforcement varied by instructor. In sum, the level of integration with other classes may not have been sufficient to change behavior and attitudes relative to the control group that was exposed to the same non-treatment curriculum.

Third, some degree of “cross-contamination” may have occurred between the experimental and control groups. Although separate instructors were used for treatment and control groups and were cautioned about not sharing treatment materials, we learned that treatment instructors were occasionally assigned to the “homeroom” of control instructors to fill in during their absence. During these assignments, some sharing of the QIP concepts with controls may have occurred. This reality underscores the importance of creating physical distance between the experimental and control groups in RCTs to prevent contamination. Whenever possible, independent training academies in separate locations should be the unit of assignment, rather than individual officers.

Fourth, based on considerable observation in the classrooms and hallways of the training academy, this type of innovation in training was “swimming upstream” against a socialization process that favored toughness and officer safety. Both the treatment and control groups, for example, reported a greater reliance on physical force to solve problems after six months of training and reported less respectful attitudes toward the community. The training was able to significantly slow the rate of decline in respectfulness, but decline occurred over six months nevertheless. The training literature outside of policing gives attention to the factors that limit the transfer to learning to behavior on the job (e.g., Salas et al. 2012), such as peer support and organizational culture, but, here, the socialization process and lessons learned in other classes prior to leaving the training academy apparently interfered with the QIP’s effectiveness.

Helping to explain these countervailing forces, one Chicago police officer noted that the training academy at the time, perhaps like other academies, suffered from an identity crisis: “On the one hand, we want engaging and innovative learning strategies that are student-centered, yet we hold on tight to a paramilitary model that stresses toughness and discipline above all else.” (For an analysis of parables in police training, see Ford 2003). Clearly, toughness and self-defense are critically important for preparing young women and men for potentially life-threatening encounters. The challenge is figuring out how to integrate respectful policing and negotiation skills into the prevailing safety paradigm that drives police perceptions and behavior. The QIP emphasized the practical safety and efficiency benefits to police officers who exhibit procedural justice and victim sensitivity during encounters. Policing is not a “zero-sum” game; safety, respect, empathy, and civilian cooperation can, and should be, more strongly linked within the training environment.

Given these realities, the total training process requires more careful examination, especially with regard to the complexities of interpersonal communication and the best way to achieve diverse personal and organizational goals during police–public encounters. The integration of material across courses is critical (in contrast to the popular “silo approach” to teaching), but the hours devoted to specific topics is also important. This is a national problem. State and local law enforcement training academies devote, on average, 71 hours of training on firearms and 60 hours on self-defense, but only 9 hours on mediation and conflict management (Reaves 2016). A better balance should be achieved.

One of the lessons coming from recent evaluations of procedural justice is that police officers struggle with the idea of applying these principles to all encounters. The benefits are more apparent to officers when fairness, respect, and concern are applied to innocent victims than to offenders such as traffic violators or disorderly youths. Future training programs should include robust discussions and role-playing addressing the fact that everyone deserves fair treatment and that procedural justice can make police work easier and save careers, especially when applied to community members who have the least respect for the police.

Despite these limitations, at the conclusion of a six-month training period, the QIP appears to have produced some positive changes in actual behavior as judged by independent observers. While these findings should be viewed with caution because they are based on a subsample of recruits, they are consistent with work by Mazerolle et al. (2012a) in Australia indicating that procedural justice behaviors can be scripted and taught to law enforcement personnel. Also, efforts in England and Scotland to replicate the QIP’s adult teaching methods and the focus on communication skills and emotions suggest that procedural justice training can be expanded beyond the standard four principles and beyond classroom lectures.

The next question is whether these effects from the classroom can be translated into street behavior that is noticeable by community members. Will young officers act the same way or will they “forget what they have learned” at the academy? Will verbal statements be viewed as genuine or contrived? In the end, the community members encountered on the job will be the final judge of whether the officers’ performance is believable and impactful.

Hopefully, this article will help to continue the dialogue about what type of police officer we are seeking during this difficult time in the history of policing, and how new training can make a difference. Our society is demanding a police officer who gives more attention to being the guardian of the community rather than the warrior (Rahr and Rice 2015). This will require a major overhaul of our police training academies, giving them the leadership, personnel, and resources needed to rethink their mission, focusing on the desired set of social and tactical skills, as well as the ethical standards valued by the community. Researchers can contribute by studying not only the impact of new models of training, but the socialization process that occurs through academic instructors, field training officers, and first-line supervisors and drives the current police culture.

Notes

We needed to remind the department’s legal counsel that: (1) recruits in the control group would still be given the same training the department had been using for years; (2) innovations are promising, but not proven, otherwise there would be no need for research and evaluation; and (3) evidence-based practice in policing would not be possible in the future without evidence, thus preventing the policing craft from ever becoming a profession, guided by knowledge.

The pretest video involved taking a report from a domestic violence victim whose order of protection had been violated and who was upset at the police for their slow response time and inability to prevent repeat offending. The posttest video required the trainee to take a report regarding a dispute between two neighbors who were arguing over a parking space (both disputants were present).

Officers who were videotaped expressed a lower desire to use force, which may suggest some reactivity from this measure, but this difference applies to both experimental and control groups.

References

Adams, K. (2004). What we know about police use of force. In Q. Thurman & J. Zhao (Eds.), Contemporary policing: Controversies, challenges, and solutions (pp. 187–199). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury Publishing Company.

Ahrens, C. E. (2006). Being silenced: The impact of negative social reactions on the disclosure of rape. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 263–274.

Barocas, H. A. (1971). Current research: A technique for training police in crisis intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, & Practice, 8(4), 342–343.

Bennett, S., Davis, J., & Mazerolle, L. (2014). Police-led interventions to enhance police legitimacy. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 3753–3765). New York: Springer.

Berringer, R. D. (2004). The effect of formal leadership training on the leadership styles of police field trainers. Masters Abstracts International, 43(2), 393.

Bittner, E. (1980). The functions of the police in modern society. In L. K. Gaines & G. W. Cordner (1999, eds.), Policing perspectives: An anthology. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury Publishing Company.

Brown, B., & Reed Benedict, W. (2002). Perceptions of the police: Past findings, methodological issues, conceptual issues and policy implications. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 25, 543–580.

Buchanan, D. R., & Perry, P. A. (1985). Attitudes of police recruits towards domestic disturbances: An evaluation of family crisis intervention training. Journal of Criminal Justice, 13(6), 561–572.

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 17–31.

Cheurprakobkit, S., & Bartsch, R. A. (2001). Police performance: A model for assessing citizens’ satisfaction and the importance of police attributes. Police Quarterly, 4, 449–468.

Christoff, T. E. (2016). Humor with a shade of blue: Examining humorous exchanges during police–community interactions. Ph.D. dissertation submitted to the Department of Criminology, Law, and Justice, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Compton, M. T., Bakeman, R., Broussard, B., Hankerson-Dyson, D., Husbands, L., Krishan, S., Stewart-Hutto, T., D’Orio, B. M., Oliva, J. R., Thompson, N. J., & Watson, A. C. (2014a). The police-based crisis intervention team (CIT) model: I. Effects on officers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Psychiatric Services, 65(4), 517–522.

Compton, M. T., Bakeman, R., Broussard, B., Hankerson-Dyson, D., Husbands, L., Krishan, S., Stewart-Hutto, T., D’Orio, B. M., Oliva, J. R., Thompson, N. J., & Watson, A. C. (2014b). The police-based crisis intervention team (CIT) model: II. Effects on level of force and resolution, referral, and arrest. Psychiatric Services, 64(4), 523–529.

Cordner, G. W., & Scarborough, K. E. (2010). Police administration (7th ed.). New Providence, NJ: LexisNexis/Anderson Publishing.

Dewe, P., O’Driscoll, M., & Cooper, C. (2010). Coping with work stress. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Driscoll, J. M., Meyer, R. G., & Schanie, C. F. (1973). Training police in family crisis intervention. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 9, 62–82.

Dugan, J. R., & Breda, D. R. (1991). Complaints about police officers: A comparison among types and agencies. Journal of Criminal Justice, 19(2), 165–171.

Dupont, R., Cochran, S., & Pillsbury, S. (2007). Crisis Intervention Team Core Elements. Memphis, TN: University of Memphis.

Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91–119.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 169–200.

Elinson, Z., & Frosch, D. (2015). Cost of police-misconduct cases soars in big U.S. cities. The Wall Street Journal. July 15. https://www.wsj.com/articles/cost-of-police-misconduct-cases-soars-in-big-u-s-cities-1437013834.

Entwistle, N., Christensen Hughes, J., & Mighty, J. (2010). Taking stock: An overview of research findings. In J. Hughes & J. Mighty (Eds.), Taking stock: Research on teaching and learning in higher education (pp. 15–51). Montreal, QC, Canada: McGill-Queens University Press.

Ford, R. E. (2003). Saying one thing, meaning another: The role of parables in police training. Police Quarterly, 6, 84–110.

Fridell, L. (2016). Fair & Impartial Policing. http://www.fairandimpartialpolicing.com.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York: Basic Books.

Gau, J. M., & Brunson, R. K. (2010). Procedural justice and order maintenance policing: A study of inner-city young men’s perceptions of police legitimacy. Justice Quarterly, 27(2), 255–279.

Gilmartin, K. M. (2002). Emotional survival for law enforcement: A guide for officers and their families. Tucson, AZ: E-S Press.

Goldstein, H. (1977). Policing a free society. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Hails, J., & Borum, R. (2003). Police training and specialized approaches to respond to people with mental illnesses. Crime & Delinquency, 49, 52–61.

Harrington, M. P. (2002). An inquiry into the effects of diversity training on police policy makers in Fairfax County, Virginia: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia.

Hickman, M. J. (2006). Citizen complaints about police use of force. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 210296. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=553.

Hyland, S. S., Langton, L., & Davis, E. (2015). Police use of nonfatal force, 2002–2011. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 249216. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5456.

Jackson, J., Bradford, B., Hough, M., Myhill, A., Quinton, P., & Tyler, T. R. (2012a). On the justification and recognition of police power: Broadening the concept of police legitimacy. New Haven, CT: Yale Law School.

Jackson, J., Bradford, B., Hough, M., Myhill, A., Quinton, P., & Tyler, T. R. (2012b). Why do people comply with the law? Legitimacy and the influence of legal institutions. British Journal of Criminology, 52(6), 1051–1071.

Jones, T. S., & Richey, R. C. (2000). Rapid prototyping methodology in action: A developmental study. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48, 63–80.

Kaiser, M. (1995). 1995 CAPS training evaluation report. Chicago, IL: Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University.

Kanov, J. M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., & Lilius, J. M. (2004). Compassion in organizational life. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 808–827.

Kendall, P. C., & Braswell, L. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for impulsive children (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Limberg, H. (2008). Threats in conflict talk: Impoliteness and manipulation. In D. Bousfield & M. A. Locher (Eds.), Impoliteness in language: Studies on its interplay with power in theory and practice (pp. 155–181). New York City, NY: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum Press.

Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(3), 272–292.

Lum, C., Koper, C. S., Gill, C., Hibdon, J., Telep, C. & Robinson, L. (2016). An evidence-assessment of the recommendations of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing—Implementation and research priorities. Fairfax, VA: Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy, George Mason University. Alexandria, VA: International Association of Chiefs of Police.

MacQueen, S., & Bradford, B. (2015). Enhancing public trust and police legitimacy during road traffic encounters: Results from a randomised controlled trial in Scotland. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11(3), 419–443.

MacQueen, S. & Bradford, B. (2016). Where did it all go wrong? Implementation failure—and more—in a field experiment of procedural justice policing. Journal of Experimental Criminology. Published online before print at: http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.1007/s11292-016-9278-7.

Marotta, P., Barnum, J., Watson, A., & Caplan, J. (2014). Crisis intervention team training programs for law enforcement officers: A systematic review. Campbell Crime and Justice Group.

Mastrofski, S. D. (1999). Policing for the people. Ideas in American Policing Series, March 1999. Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

Mastrofski, S. D., Snipes, J. B., & Supina, A. E. (1996). Compliance on demand: The public’s response to specific police requests. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 33(3), 269–305.

Mastrofski, S. D., Reisig, M. D., & McCluskey, J. D. (2002). Police disrespect toward the public: An encounter-based analysis. Criminology, 40(3), 519–552.

Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2007). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 507–536. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646.

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Antrobus, E., & Eggins, E. (2012a). Procedural justice, routine encounters and citizen perceptions of police: Main findings from the Queensland Community Engagement Trial (QCET). Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8, 343–367.

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Manning, M., Ferguson, P. & Sargeant, E. (2012b). Legitimacy in policing: A systematic review of procedural justice. Campbell Crime and Justice Group.

Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Tyler, T. R. (2013). Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: A randomized field trial of procedural justice. Criminology, 51, 33–63.

McCluskey, J. D. (2003). Police requests for compliance: Coercive and procedurally just tactics. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing.

McCluskey, J. D., Mastrofski, S. D., & Parks, R. B. (1999). To acquiesce or rebel: Predicting citizen compliance with police requests. Police Quarterly, 2, 389–416.

Miller, K. I. (2007). Compassionate communication in the workplace: Exploring processes of noticing, connecting, and responding. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 35, 223–245.

Morabito, M. S., Kerr, A. N., Watson, A., Draine, J., Ottati, V., & Angell, B. (2012). Crisis intervention teams and people with mental illness: exploring the factors that influence the use of force. Crime & Delinquency, 58(1), 57–77.

Morris, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2000). How emotions work: The social functions of emotional expression in negotiations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22, 1–50.

Moses, J. L. (1978). Behavior modeling for managers. Human Factors, 20, 225–232.

Mulvey, E. P., & Reppucci, N. D. (1981). Police crisis intervention training: An empirical investigation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(5), 527–546.

Murphy, K., Hinds, L., & Fleming, J. (2008). Encouraging public cooperation and support for police. Policing and Society, 18(2), 136–155.

Myhill, A., & Quinton, P. (2011). It’s a fair cop? Police legitimacy, public cooperation, and crime reduction: An interpretative evidence commentary. National Policing Improvement Agency.

New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board (2013). 2012 Annual report.