Abstract

Mangroves are one of the most productive, diverse ecosystems on the planet and serve as a protective barrier for coastal areas. Shrimps have a productive correlation with mangroves habitat, thereby large-scale shrimp farming pose a serious threat to mangroves ecosystems. The present study was carried out to estimate the total area under shrimp farming in the intertidal regions of Kannur district. From the study, we have documented 140 shrimp ponds, which contributes to a total area of 524.4 ha. We found that active shrimp farming area in the district is 524.4 ha in 2020. The traditional shrimp farming method accounts for 60.6% of the total farmed area while non-traditional shrimp farming accounts for 36.9% of the total farmed area; both types are expanding fast in the district. Of the five major Rivers in the district, Kuppam River has the majority of the shrimp farms followed by Dharmadam River. Penaeus monodon, Litopenaeus vannamei and Penaeus indicus are the shrimp species cultivated in the district. Since shrimp farms are created by replacing the mangrove habitats in the intertidal region, mangroves of Kannur district are under threat and needs serious intervention for long term survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mangrove ecosystems are the most productive ecosystem, that contribute several socio-economic and ecological services (Kathiresan 2010). They stabilise coastlines and mitigate the devastation caused by natural calamities such as tsunamis and hurricanes. Also serve as breeding and nursing grounds for a variety of commercially important fish, molluscs, and crustaceans. Despite occupying just 0.1% of the earth’s geographical surface, mangroves account for 11% of total terrestrial carbon intake into the ocean and 10% of terrestrial dissolved organic carbon released to the ocean (Jithendra et al. 2014).

Kerala, the southern Indian state, once had 700 km2 of mangroves along its 41 west-flowing Rivers and associated estuaries and backwaters (Edwin 2002; George et al. 2018). A recent study records only 17.82 km2 of mangroves in Kerala which depicts a loss of more than 90% of the historical extent. Almost 90% of these forests are privately owned and therefore highly threatened. The mangroves of Kerala are scattered in 10 coastal districts (Sreelekshmi et al. 2021). Across the districts of the state, Kannur has the largest extent of mangroves (Preethy 2019).

Mangrove areas are ideal for shrimp farming (Barbier and Cox 2004). For the preparation of shrimp farms, mangroves and wetlands are levelled and destroyed (PÁez-Osuna 2001) which is the main reason for loss of mangroves globally (Jayanthi et al. 2007; Berlanga-robles et al. 2011). The conversion to shrimp farms has detrimental effects on the dependent communities, also by impacting their livelihood (Treviño and Murillo-Sandoval 2021). Effluents from the shrimp farms adversely affect the biotic and abiotic components of the mangrove ecosystem (Primavera 1997, 2006; Ashton 2008; Mishra et al. 2008; Biao et al. 2009; Hamilton 2011; Pattanaik and Prasad 2011.

Shrimp farms in India were established in the late 1980s in response to increased demand from the worldwide market (Jayanthi et al. 2018). India ranks second in terms of shrimp production (FAO 2016). Over the past 25 years, there has been an 879% increase in aquaculture land in India (Jayanthi et al. 2018).

There are two types of shrimp cultivation systems in Kerala: traditional and non-traditional. The traditional shrimp aquaculture systems are usually sustainable, low- intensive and small scale. They mainly depend on diurnal tidal inundation to supply the larval shrimp and their food nutrients to the ponds. The non-traditional shrimp farms were introduced for increasing the production (Bhattacharya 2010). They are focussed on modern farming techniques such as intensification of culture operation by innovative changes on pond size, increasing stocking rate, employment of aeration, application of formula feed etc. In Kerala indigenous shrimp species like Penaeus monodon and P. indicus and other wild varieties are usually cultivated in traditional systems whereas in non-traditional farming, Litopenaeus vannamei and P. monodon are the common species (Bhattacharya 2010).

Farmers in Kerala are well versed in traditional shrimp farming and have a long history of traditional breeding of native species. The total area devoted to shrimp farming in Kerala in 2017–2018 was estimated at 10,599.26 ha, of which 8430.98 ha is under traditional farming and 2168.28 ha is under non-traditional farming. The annual production of farmed shrimp in Kerala was estimated at 2952.56 metric tons. Of this, the contribution of the traditional sector was 2174.80 metric tons (73.66%) and that of the non-traditional sector was 777.76 metric tons (26.34%). The productivity of shrimp farms in Kerala was calculated at 932.08 kg ha−1 year−1 (Sahadevan and Sureshkumar 2020).

The shrimp farms of Kerala are spread across 10,599 ha, while the total extent of mangroves of the state has dwindled to around 1782 ha (Sahadevan and Sureshkumar 2020; Sreelekshmi et al. 2021). The area and diversity of mangroves of Kerala is falling at an alarming rate (Pillai and Harilala 2015). Kannur district which holds largest share of mangroves of the state, has around 1500 ha of mangroves as shown by the online map published by Wildlife Trust of India. Of this extent, only 236 ha of mangroves are legally protected as Reserve Forests (Bala Kiran 2017). Since the remaining mangrove areas are threatened and unprotected, the objective of the present study is gaining understanding the status of mangroves and shrimp farms in Kannur district.

Materials and methods

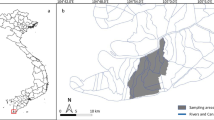

The study area is the Kannur district of Kerala, with a geographical area of 2966 km2, located between 11° 40′ to 12° 08′ N latitudes and 75° 11′ and 76° 08′ E of longitudes (Fig. 1). The district is bounded by Kasaragod district in the north, Western Ghats in the east (Coorg district of Karnataka state), Kozhikode and Wayanad districts in the south and Lakshadweep Sea in the west. Kannur district has the maximum area of mangrove forest cover in the Kerala state relative to other districts. The most suitable place for shrimp aquaculture is the mangrove habitat, which is why the number of such ponds is increasing day by day in Kannur.

An interactive map of mangroves depicting the geographic distribution and various details of the mangroves in the Kannur district was available on the website of the non-governmental organization, Wildlife Trust of India through its Kannur Kandal Project. Overlaying this interactive map on Google earth, all the shrimp ponds were searched in the intertidal zone of Kannur and the polygons were drawn. Then these intertidal zones were surveyed physically to collect data on all the shrimp farms across the district. The field surveys were conducted during March 2021–December 2021, collecting details including the type of farming (traditional or non-traditional), species cultivated, year of creation of the farm, area, panchayath name. Characteristics including > 1 m pond depth, use of modern equipment, chemical fertilizers and feeds differentiate the non-traditional shrimp farm method from the traditional method. L. vannamei is cultivated only in the non-traditional shrimp farms. This data was also cross checked with the available information from the Fisheries department.

Results

Area under shrimp farming across different Local Self Government Departments in Kannur district

The study recorded 140 active shrimp farms in Kannur district, with a total area of 524.4 ha (Fig. 2). The study also reveals that 23 Local Self Government Departments (LSGDs) have shrimp farms, and Ezhome (27.8%), Dharmadam (12%), and Cherukunnu (10.4%) have the most abundant areas (Fig. 3).

From the analysis, mean value and standard deviation of total area of shrimp farms across the studies LSGDs in Kannur district is 0.04 and 0.06 respectively. This shows a significant impact (p = 0.00) on mangrove forests due to the shrimp farms (Fig. 4).

Expansion of shrimp farming area in Kannur district since 2000

The area of active shrimp farms in the district in 2020 shown by the present study is 524.4 ha. Among these active shrimp farms, only 235.4 ha (44.9%) were started before 2000. The remaining 289 ha (55.1%) were started after 2000. Of these, 126 ha were created during 2015–2020, while 79.1 ha were created during 2010–2015 (Fig. 5).

Percentage distribution of shrimp farm types in Kannur district

The percentage distribution of shrimp farm types in Kannur district are shown in Fig. 6, with traditional cultivation contributing 60.7% (318.1 ha) of total area and 36.9% (193.5 ha) under non-traditional method. Only 2. 4% (12.8 ha) is under mixed farming in which both traditional and non-traditional methods are used (Fig. 6).

Shrimp species used in Kannur district

The study reveals that the shrimp species used for cultivation in Kannur district are Penaeus monodon, Litopenaeus vannamei and Penaeus indicus. Some shrimp farms also cultivate fishes like Etroplus suratensis and Lates calcarifer. L. vannamei is an exotic species from Pacific coast of Mexico and Central and South America as far south as Peru (Liao and Chien 2011). It is being utilised in many countries because of its high tolerance to wide range of salinities, low temperature, high growth rate and higher survival rate in hatchery. The omnivorous scavenger L. vannamei is less aggressive than P. monodon. It can tolerate a large range of salinities (0.5–45 ppt) but it grows well at 10–15 ppt (Sadek and Nabawi 2021). L. vannamei can tolerate the temperature variations, ranging from 7.5–42 °C, usually farming is recommended above 12 °C (Kumlu et al. 2010).

Extent under traditional and non-traditional shrimp farms during 2000–2020

Among the active shrimp farms, the extent of traditional shrimp farming has increased from 165.2 to 318.1 ha during the time period 2000–2020. At the same time, the area under non-traditional shrimp farming has increased from 91.1 in 2000 to 206.3 ha in 2020 (Fig. 7). The increase in the extent of non-traditional shrimp farms during 2015–2020 is mainly due to the introduction of L. vannamei. Due to its resistance to a wide range of salinities, fast weight gain over a short period of time and high meat production, majority of the farmers are choosing L. vannamei over other indigenous species for farming (Kumaran 2016).

Extent of shrimp farm distribution across various rivers in Kannur district

There are many minor and major rivers flowing through Kannur district. Shrimp farming in the district is mainly distributed along the rivers: Kuppam (51.7%), Dharmadam (24.6%) and Perumba (10%). The extent of shrimp farms along Kuppam river is 270.9 ha. The Kuppam river flows between Ezhome and Cherukunnu panchayaths, where the majority of shrimp farms are found. Dharmadam river and Perumba river has shrimp farms of area 129 ha and 52.4 ha respectively. Kavvayi river and Anjarakandy river possesses comparatively small areas of ponds of less than 1 ha (Fig. 8).

Discussion

The present study recorded 524.4 ha area of shrimp farms in the intertidal regions of the Kannur district. A study in 2007 recorded only 251.5 ha of shrimp farms in Kannur district (Harikumar and Rajendran 2007). This shows that over the last 13 years, there was an increase of 272.9 ha in the shrimp farm area. The results also prove that the area of shrimp farms is increasing since 2000 especially after 2015. Kerala Fisheries Department is providing financial and technical support to shrimp farmers; financial subsidies from the department to shrimp farmers raise up to 80% of the cost for setting up new shrimp farms. At the same time, private land owners protecting mangroves in their land are not getting any support or incentives from the Government. This scenario will aggravate the rate of destruction of mangroves in Kannur district. Since Kannur district holds major portion of mangroves in Kerala, urgent measures are required to secure the mangroves in the district.

Because of its advantages, farmers choose L. vannamei over other species. L. vannamei requires scientific farming techniques for successful cultivation. This promotes the non-traditional shrimp farming which causes larger long-term impacts on the mangrove ecosystems. Non-traditional shrimp ponds are usually 1–1.5 m depth in the district, which prevents natural regeneration of mangroves even after the ponds are abandoned. Topographical changes are required to initiate mangrove restoration in the abandoned ponds. Such measures must be initiated to bring back the lost mangrove cover. Mangrove afforestation along the borders of the functioning ponds also has to be facilitated to minimize the impacts of shrimp farming.

Application of several chemicals, fertilizers and feeds in the shrimp farms will adversely affect several micro-organisms (Rahman et al. 2013; Iqbal and Milon 2018). Lime, urea and other inorganic fertilizers used in shrimp ponds can have a negative impact on the natural soil structure, reducing the prospects for further mangrove restoration (Balakrishnan et al. 2011).

Conclusion

In the intertidal regions of Kannur district, mangrove ecosystems have been deforested and converted to shrimp farms. The conclusion we have reached through the study is that the excessive encroachment onto mangrove forest for shrimp farming increased across the last decades. This is severely affecting the structure and function of mangrove ecosystems. The mangrove forests of the LSGDs like Ezhome, Dharmadam, Cherukunnu are under very immediate threat. Continuing such trends in long-term might degrade the mangrove forest cover. In the light of global climate change and sea level rise, the coastal areas near these cultivations are under serious threat from flooding. It is therefore imperative that all stakeholders become aware of the impending danger, and the Government take necessary actions towards regulating shrimp farms.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Ashton EC (2008) The impact of shrimp farming on mangrove ecosystems. CAB Rev. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20083003

Bala Kiran P (2017) Mission mangroves Kannur. Mangal-Van. Mangrove Society of India, Goa, pp 41–54

Balakrishnan G, Peyail S, Ramachandran K, Theivasigamani A, Savji KA, Chokkaiah M, Nataraj P (2011) Growth of cultured white leg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone 1931) in different stocking density. Adv Appl Sci Res 2(3):107–113

Barbier EB, Cox M (2004) An Economic analysis of shrimp farm expansion and mangrove conversion in Thailand. Land Econ 80(3):389–407

Berlanga-robles C A, Ruiz-luna A, Hernandez-Guzman R (2011) Impact of shrimp farming on mangrove forest and other coastal wetlands: the case of Mexico. Aquaculture and environment a shared destiny. http://www.intechopen.com/books/aquaculture-and-the-environment-a-shared-destiny

Bhattacharya P (2010) Comparative study of traditional vs scientific shrimp farming in West Bengal: a technical efficiency analysis. Indian Econ J. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019466220100206

Biao X, Tingyou L, Xipei W, Yi Q (2009) Variation in the water quality of organic and conventional shrimp ponds in a coastal environment from eastern China. Bulg J Agric Sci 15(1):47–59

Edwin S (2002) Mangrove ecosystem biodiversity: a case study. Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Cochin

FAO (2016) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture report. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome

George G, Krishnan P, Mini KG, Salim SS, Ragavan P, Tenjing SY, Muruganandam R, Dubey SK, Gopalakrishnan A, Purvaja R, Ramesh R (2018) Structure and regeneration status of mangrove patches along the estuarine and coastal stretches of Kerala India. J for Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-018-0600-2

Hamilton SE (2011) The impact of shrimp farming on mangrove ecosystems and local livelihoods along the pacific coast of Ecuador. The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg

Harikumar G, Rajendran G (2007) Kerala fisheries—An over view of particular emphasis with on aquaculture. IFP Souvenir, Noida

Iqbal MH, Milon SRH (2018) Impact of land use for shrimp cultivation instead of crop farming: the case of southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. World Rev Bus Res 8(2):1–12

Jayanthi M, Gnanapzhalam L, Ramachandran S (2007) Assessment of impact of aquaculture on mangrove environments in the south east coast of India using remote sensing and geographical information system (GIS). Asian Fish Sci 20:325–338

Jayanthi M, Thirumurthy S, Muralidhar M, Ravichandran P (2018) Impact of shrimp aquaculture development on important ecosystems in India. Glob Environ Change 52:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.05.005

Jithendra K, Vijay KME, Rajanna KB, Mahesh V, Naik KAS, Pandey AK, Manjappa N, Pal J (2014) Ecological benefits of mangrove. Life Sci Leafl 48:85–88

Kathiresan K (2010) Importance of mangrove forests in India. J Coast Environ 1(1):11–26

Kumaran M, Anand PR, Kumar JK, Ravisankar T, PaulKumaraguru vasagam JKP, Vimala DD, Raja K (2016) A is pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) farming in India is technically efficient? A comprehensive study. Aquaculture 468:262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.10.019

Kumlu M, Turkmen S, Kumulu M (2010) Thermal tolerance of Litopenaeus vannamei (Crustacea: Penaeidae) acclimated to four temperatures. J Therm Biol 35:305–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2010.06.009

Liao IC, Chien Y-H (2011) The pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, in Asia: the world’ s most widely cultured alien crustacean. In: Galil BS et al (eds) In the wrong place-alien marine crustacean; distribution, biology and impacts. Springer, Dordrecht

Mishra RR, Rath B, Thatoi H (2008) Water quality assessment of aquaculture ponds located in Bhitarkanika mangrove ecosystem, Orissa, India. Turk J Fish Aquat Sci 8:71–77

PÁez-Osuna F (2001) The environmental impact of shrimp aquaculture: causes, effects, and mitigating alternatives. Environ Manag 28(1):131–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002670010212

Pattanaik C, Prasad SN (2011) Ocean & coastal management assessment of aquaculture impact on mangroves of Mahanadi delta (Orissa), east coast of India using remote sensing and GIS. Ocean Coast Manag 54:789–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.07.013

Pillai NG, Harilala CC (2015) Status of mangrove diversity in the coastal environments of Kerala. Eco Chron 10(1):30–35

Preethy C M (2019) The systematics, floristics and ecology of selected mangroves of Kerala. Thesis submitted to the Department of Marine Biology, Microbiology & Biochemistry School of Marine Sciences, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kochi

Primavera JH (1997) Socio-economic impacts of shrimp culture. Aquac Res 28:815–827

Primavera JH (2006) Overcoming the impacts of aquaculture on the coastal zone. Ocean Coast Manag 49:531–545

Rahman MM, Giedraitis VR, Lieberman LS, Akhtar T, Taminskienė V (2013) Shrimp cultivation with water salinity in Bangladesh: the implications of an ecological model. Univ J Public Health 1(3):131–142. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujph.2013.010313

Sadek MF, Nabawi SS (2021) Effect of water salinity on growth performance, survival %, feed utilization and body chemical composition of the Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei juveniles. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish 25(4):465–478

Sahadevan P, Sureshkumar S (2020) Estimation of farmed shrimp production in Kerala. Int J Fish Aquat Stud 8(4):392–400. https://doi.org/10.22271/fish.2020.v8.i4e.2297

Sreelekshmi S, Veettil BK, Nandan SB, Harikrishnan M (2021) Mangrove forests along the coastline of Kerala, southern India: current status and future prospects. Reg Stud Mar Sci 41:101573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2020.101573

Treviño M, Murillo-Sandoval PJ (2021) Uneven consequences: gendered impacts of shrimp aquaculture development on mangrove dependent communities. Ocean Coast Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105688

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Kannur Kandal Project of Wildlife Trust of India and Apollo Tyres. The authors are grateful also to the Department of Geography-Kannur University, Kerala Fisheries department and Agency for the Development of Aquaculture in Kerala (ADAK). Also, sincere thanks to Aiswarya V V, MSc. student of the Department of Environmental Science, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore and Mohammed Shanid, MSc. student, Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Pondicherry University. The authors also thank Ms. Navya K K, PhD scholar, Kerala Forest Research Institute and Mr. Sachin Chandran, PhD scholar, Payyanur College for their inputs.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, RM; methodology, RM.; BP.; software, SKP; validation, BP, RM, MT; formal analysis, BP, RM; investigation, BP, PMN; data curation, BP; writing-original draft preparation, BP, MT, PMN; writing-review and editing, RM, BP, SKP; project administration, RM; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bijith, P., Ramith, M., Megha, T. et al. Shrimp farms as a threat to mangrove forests in Kannur district of Kerala, India. Wetlands Ecol Manage 30, 1281–1289 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-022-09896-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-022-09896-y