Abstract

Informed by self-determination theory (SDT), this study explores older adults’ long-term community volunteering experiences and motivations in Shanghai. We took a qualitative research approach to conduct face-to-face, semi-structured, in-depth interviews with older adults who were long-term volunteers in Shanghai communities (N = 69). We performed thematic analysis and generated themes for their experiences and evolving motivations. Participants began volunteering because it was enjoyable and helped them adapt to life after retirement. As their volunteering progressed, participants’ motivations gradually evolved and they developed a fusion motivation––juewu, combining characteristics of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations––for their strong commitment to volunteering. Gradually, participants assimilated juewu into their volunteer identity, which encouraged them to lead community self-governance initiatives. This study sheds light on the evolving, nuanced, underlying motivational process that shapes older adults’ experiences of long-term community volunteering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Volunteering is one of the most important avenues for older adults to continue engaging with the society after retirement (Morrow-Howell, 2010) and a way to offset the impacts of a shrinking labor market (Gonzales et al., 2015). Given the unprecedented aging population in China, the Chinese government has recognized the value of older volunteers and advocated for older adults’ productive engagement (lao you suo wei 老有所为; China National Committee on Aging, 2008). In China, older adults are usually the primary community members who volunteer to increase service availability and affordability for their communities (Xu, 2007). Volunteering in the community—such as doing voluntary work and participating in governmental or nonprofit organizations—has rapidly become one of the most popular patterns of productive engagement among Chinese older adults (Liu & Lou, 2016).

More recently, community self-governance initiatives in urban China have further relied on older volunteers, especially those who are retired members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP; e.g., Bray, 2006; Lee & Zhang, 2013; Read, 2012). Seeing it as their moral duty (Bray, 2006), Chinese older volunteers contribute to community self-governance initiatives to show their model moral status and achieve generativity (i.e., providing a moral example for the younger generations) to raise all residents’ overall suzhi (素质), meaning the qualities of behavior, education, and ethics related to the concepts of breeding (jiaoyang教养) and personal cultivation (xiuyang 修养; Tomba, 2014; The China Story, 2013). This agenda is likely based on the Chinese cultural belief that older adults possess wisdom and experience that can foster familial and social harmony and stability (Peng & Fei, 2013). However, most existing studies on Chinese urban communities focus on strategies for promoting community self-governance initiatives and related policies (see Xiao, 2011); research on older volunteers has primarily focused on the outcomes of volunteering, while little is known of how their motivations and experiences change during the process of volunteering, especially in these community self-governance initiatives.

In order to illustrate these changes in older volunteers’ motivation during their volunteering experiences in Chinese urban communities, we applied the self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000) as the framework. By examining the quality of motivation, SDT offers a theoretical lens to illuminate the “underlying motivational process” (van Schie et al., 2015, p. 1574) and the interplay between volunteering motivation and contextual elements (Nencini et al., 2016). Thus, the purpose of this study is to explore older adults’ evolving experiences of and motivations for long-term community volunteering in urban China. We took a qualitative approach and conducted face-to-face, semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 69 older long-term volunteers in Shanghai and applied SDT to analyze the evolution of their motivations in relation to their community volunteering experiences.

Literature Review

Older Adults and Volunteering

Older Volunteers in Western Contexts

A growing body of Western evidence has suggested that volunteering can benefit older adults (e.g., Haski-Leventhal 2009; Russell et al., 2019; Taghian et al., 2019). On the individual level, volunteering provides them with opportunities to improve their personal outlook (Taghian et al., 2019) and enhance their self-perceived health (Nappo & Firorillo, 2020; Fiorillo & Nappo, 2017). Russell and colleagues (2019) found that volunteering could improve older American adults’ negative self-esteem, sense of belonging, and life satisfaction. Volunteering also brought new meaning and offered new identities to Dutch older adults to compensate for their lost role identity after retirement (van Ingen & Wilson, 2017). In additional to mental benefits, volunteering can bring monetary rewards as well as boost volunteers’ human capital (Bruno & Fiorillo, 2016).

Sociocultural contexts are the critical backdrop for older adults’ productive engagement (Morrow-Howell & Wang, 2013). Volunteering extends social networks for older adults (e.g., Bruno & Fiorillo, 2016), which, in turn, can lead to improved well-being and reduced depressive symptoms (Chen, Ye & Wu, 2020; Choi et al., 2013; Warburton & Winterton, 2017) as well as continued volunteering (Dury et al., 2020). For example, Han and colleagues (2019) explored older volunteers’ perspectives on their volunteering experiences in a community-based social support program for people with dementia. Older volunteers valued the opportunity to have meaningful social relationships with others (Han et al., 2019). Older Australian volunteers took the caring nature of community as part of their identity (Warburton & Winterton, 2017). Volunteering is also influenced by older adults’ life-course experiences. For example, Chambré and Netting (2018) revealed that the trend of volunteering among retired baby boomers in the USA was motivated by meaningful social engagement and light compensation.

Older Volunteers in the Chinese Community

Since the Economic Reform in 1978, the work unit system in urban China has broken down, leading the Ministry of Civil Affairs to encourage communities themselves to integrate fragmented social welfare services previously provided by work units (Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs, 2000; Heberer & Göbel, 2011). Under this guideline, a residents’ committee is tasked with overseeing all the administrative affairs of the residential area, representing its residents, and providing social welfare and security, as well as training residents to govern themselves (Bray, 2006; Guo, 2010; Heberer & Göbel, 2011).

Typically, residents’ committees and local branches of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) purposefully recruit retirees to volunteer in the community in several different capacities: neighborhood patrol; charity work; and social welfare activities, such as mentoring youth and caring for older adults and individuals with disabilities (Chen & Adamek, 2017; China National Committee on Aging, 2008; Peng & Fei, 2013). The CCP considers retirees, especially older CCP members, morally dependable, committed, and capable of enhancing other residents’ virtues (Bray, 2006; Guo, 2010; Lin, 2001; Tomba, 2014). These older volunteers have become a major force of community building in urban China (Bray, 2006; Chen & Adamek, 2017; Lee & Zhang, 2013; Read, 2012).

Chinese studies on older volunteers have yielded similar findings to those of Western studies. It has been well documented that community volunteering can benefit older Chinese volunteers’ well-being by reducing their depressive symptoms (Liu & Lou, 2017) and improving their functional and self-rated health (Li et al., 2013). Older Chinese volunteers are also more likely to achieve positive self-identity and younger subjective age than their non-volunteer counterparts (Xie, 2015). These positive effects largely derive from the fact that volunteering in the community supplies, establishes, and expands social connections for older adults, integrating them into their community and encouraging them to continue to contribute to it (Chen et al., 2020). Despite these similar outcomes, little is known of the implications of Chinese social contexts for older volunteers’ motivations and experiences.

Motivation to Volunteer

Self-determination theory (SDT) specifies individuals’ innate needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness, as manifested in their desire to learn new skills and seek personal growth (Deci & Ryan, 2000). SDT assumes that individuals are self-motivated, curious, and reward-seeking and thus determined to succeed (Deci & Ryan, 2000). SDT emphasizes that the quality of motivation is more important than the quantity (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

SDT distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000) to examine the quality of motivations. Intrinsic motivations indicate behaviors and activities that are interesting and satisfying. That is, individuals are self-determined––they choose to behave based on their volition (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Extrinsic motivations indicate external factors that drive individuals to seek desirable outcomes (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). There are four types of extrinsic motivation: integrated, identified, introjected, and external (Deci & Ryan, 2008). External motivation suggests that individuals volunteer to receive others’ approval (Bidee et al., 2013; Deci & Ryan, 2000). They may also be driven by monetary incentives to volunteer (Fiorillo, 2011). Introjected motivation suggests that individuals volunteer to prove something or to avoid guilt or anxiety (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Identified motivation suggests that individuals recognize and willingly accept volunteering as a value (Bidee et al., 2013; Deci & Ryan, 2008). Integrated motivation suggests that individuals integrate the values of volunteering (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Deci and Ryan (2008) proposed that extrinsic and intrinsic motivations form a continuum of motivations, from passive compliance to self-determined.

Recent quantitative studies have applied SDT’s extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to examine the determinants and consequences of volunteering motivation. For example, Bidee and colleagues (2013) revealed a positive link between intrinsic motivation and work effort. Oostlander and colleagues (2014) found that autonomy-supportive leadership as a contextual element can positively influence volunteer motivation. Wu and colleagues (2016) investigated Chinese volunteers’ intention to work for the Special Olympics. The study found that intrinsic motivation was associated with their intention to continue to volunteer, mediated by job satisfaction. Others studies showed that organizational contexts also mattered to support volunteers’ autonomous motivations and satisfaction with volunteering (Nencini et al., 2016; van Schie et al., 2015). SDT provides these studies with a theoretical underpinning to connect volunteering context and outcomes with motivations, and to construct a motivational process (Nencini et al., 2016; van Schie et al., 2015).

However, these quantitative studies all assume that extrinsic and intrinsic motivations are qualitatively different. This may be related to the fact that studies on motivation to volunteer often circumscribe the antecedent stage of volunteering while neglecting its implications for sustained volunteering (Snyder & Omoto, 2008; Wilson, 2012). Although motivation to volunteer has been found to be systematically related to time devoted to volunteering (Finkelstein, 2009), existing literature has remained relatively silent on changes of motivation in relation to the volunteering process (Wilson, 2012). Also, existing evidence on motivation to volunteer is primarily quantitative; further qualitative evidence on the socially and culturally constructed, meaning-making aspect of motivation is needed (Hayakawa, 2014; Weenink & Bridgman, 2017).

In the existing literature, only a few studies have explicitly explored older Chinese adults’ motivations to volunteer. For example, Xu (2007) found that older adults with lower education levels were more likely to volunteer because they wanted to increase service availability and affordability in their communities. Duan and Wang (2010) reported that older adults in Beijing volunteered to increase self-realization, expand social networks, and fulfill their sense of social responsibility. Still, little is known of older volunteers’ experiences and motivations related to community self-governance in urban China. Weenink and Bridgman (2017) stressed that the study of motivations to volunteer should be situated in the volunteering process; thus, the dynamic of older Chinese adults’ motivation to volunteer deserves an examination within the current context of community self-governance initiatives.

Methods

Study Design and Procedure

This was a qualitative study based on face-to-face, semi-structured, in-depth interviews with long-term older volunteers in Shanghai. A qualitative design was suitable to understand older adults’ own perceptions of motivations and experiences during their long-term volunteering in community self-governance initiatives.

After receiving ethical approval from the university,Footnote 1 we conducted our study in Shanghai from 2017 to 2019. We disseminated the study information and invitations to participate in the neighborhoods of 15 residents’ committees. We combined purposive and snowballing sampling strategies to recruit eligible participants. The inclusion criteria were: (a) long-term, dedicated volunteers (i.e., over one year) and (b) active volunteers (i.e., volunteering at the time of the interview). The final sample size of 69 participants was determined by data saturation, that is, the point at which subsequent interviews offered little or no new information for data analysis (Guest et al., 2011; Morse, 2015).

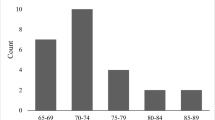

A total of 25 females were among the 69 volunteers. Participants’ average age was 69.6 years old, ranging from 60 to 85 years old. Approximately 80% of the participants had volunteered for over 5 years and the other 20% had volunteered for 1 to 3 years. Almost 70% were married and lived with their spouse. A majority (77.5%) were CCP members. Over two thirds reported having a medium to high income. Table 1 presents detailed demographic characteristics of the participants.

Participants volunteered in various programs and services in their communities, including parking management, trash sorting, neighborhood watch, traffic monitoring, sanitation services, and daily logistics in the residents’ committees. They also served as leaders of various activity groups, such as Tai Chi, singing, photography, and calligraphy.

Data Collection

After receiving informed consent from each participant, we began each interview by asking participants to recount how they had begun volunteering. We followed with detailed questions to retrospectively trace their initial decision and motivations to volunteer (e.g., How did you begin volunteering in the community? What was your primary reason to begin volunteering?); their volunteering experiences (e.g., What was the most impressive/memorable volunteering experience for you?); any changes in their motivations during the process (e.g., How have your perceptions of volunteering evolved during the process?); and their perceptions of volunteering (e.g., How do you consider volunteering before and after volunteering?). Each interview concluded with a speculation question about the future for older volunteers in the community.Footnote 2 Since almost every participant discussed how their juewu (觉悟; i.e., an awareness related to commitment to the public good) related to their long-term, strong commitment to volunteering, we asked probing questions to further explore this topic. Each participant was interviewed for 1–2 h at their home or in a designated private room at the residents’ committee offices. Each interview was conducted in Mandarin or Shanghai dialect and was audiotaped with participants’ permission. We assigned pseudonyms to each participant to protect their anonymity and privacy.

Data Analysis

We used standard qualitative research techniques when analyzing the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). We first transcribed the interviews in Chinese verbatim and read through the transcripts to gain a holistic understanding of participants’ volunteering experiences. We open-coded all the transcripts using line-by-line technique (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Codes and statements were then grouped into various categories based on similarities across descriptions of participants’ experiences of volunteering and different types of motivations (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Similar statements and recurrent categories were then grouped together to form themes pertaining to participants’ motivations to volunteer, the volunteering process, and their understanding of volunteering (Guest et al., 2011). Interpretations of themes and final narratives were based on both authors’ consensus on the definition of each theme (Creswell & Poth, 2016). After identifying all the themes, we read through the original transcripts again to ensure that all themes were accounted for. Both authors are proficient in both Chinese and English, and we translated quotations and excerpts into English for the purpose of reporting our findings. We kept memos and discussion notes as an audit trail.

Results

Participants recounted their experiences of beginning volunteering in the community after their retirement. They found volunteering intrinsically enjoyable. Volunteering helped expand their social connections, promote their continual personal growth, and facilitate their adaptation to the aging process. Participants believed that juewu––a fusion motivation combining characteristics of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation––sustained their strong commitment to the public good and encouraged them to lead community self-governance initiatives. Participants’ long-term volunteering experiences suggest an evolving, dynamic motivational process.

At the Beginning: Volunteering to Adjust to Retirement

When asked how they began volunteering in the community, all participants responded that it helped them better adapt to life after retirement. They found volunteering genuinely interesting and believed that it helped extend their social connections in the community in which they had seldom interacted before retirement. Almost all the participants (96%) concurred that volunteering offered them an opportunity to continue to seek competence after retirement. For example, 68-year-old Mr. Liu was proud of leading an award-winning Chinese painting group:

I am learning Chinese landscape painting and serving the group at the same time. I have made good friends. Our group was awarded outstanding volunteering group citywide in 2015. I have also received painting awards in the district competitions in recent years.

Retirement did not stop participants from seeking continual personal growth. Self-realization and salient developmental activities attracted participants to volunteer in community-based social activities. Indeed, these were the starting point for all the participants to discover and become involved in community volunteering. Most of those who had volunteered for less than 5 years (20%) were active members of various community-based social activity groups.

A majority of participants (80%) had volunteered for over 5 years and acknowledged that volunteering had become a platform for them to exercise the capabilities they had accumulated throughout their life course. For example, 70-year-old Mr. Li, who had been the director of the homeowners’ association in his community for almost 6 years, said:

I was a director in a World 500 enterprise before retirement. The homeowners’ association can benefit from my managerial experiences so I decided to volunteer. It is very natural for me to contribute to my community.

Volunteering in the community allowed participants to continue to engage with society and express their values. Not only did they seek enjoyment after retirement, but volunteering offered them various opportunities to demonstrate their usefulness. In the face of adversities brought on by their advancing age, volunteering became a way for participants to continue to exercise their capabilities, express their values, buttress their self-esteem, and engage with society. As such, volunteering gave participants a sense of existential purpose; as 62-year-old Mrs. Peng put it philosophically, “I volunteer, hence I exist.”

Juewu: A Fusion Motivation Sustaining Volunteering

Those who had volunteered for over 5 years (80%), credited juewu––an awareness related to commitment to the public good––with sustaining their long-term volunteering in the community. The length of time devoted to community volunteering set them apart from less experienced volunteers. All of these more experienced participants volunteered not only in community social activities but, more importantly, in community affairs, such as in the residents’ committees and local CCP branches. In particular, participants who had volunteered for over a decade (36%) believed that their long-term involvement reinforced their juewu, which reciprocally motivated them to continue to volunteer. Specifically, juewu consisted of participants’ sense of progressiveness (xian jin xing 先进性) and authority, combined with a sense of enjoyment, to sustain their continual contribution to the community.

A Sense of Progressiveness

The CCP defines party members’ progressiveness as consciously assimilating party ideology and advancing morality to achieve model moral status and lead other residents (People.cn, 2013) and participants who were CCP members (77.5%) believed volunteering was an ideal milieu for demonstrating their sense of progressiveness. Community volunteering was a particularly essential step for retired CCP members to continually present and refine their moral progressiveness. For example, 69-year-old Mr. Tian believed that his solid juewu qualified him to volunteer for the residents’ committee for almost a decade:

A group of older adults began volunteering to help [with] the 2010 census in our community. Most of them gave it up halfway because the work was time-consuming and with little compensation. As a CCP member, I kept going and finished the job. The local party branch director believed that I had solid juewu and perseverance, then asked me to continue to volunteer in the residents’ committee [till now].

The invitation from the local party branch director validated Mr. Tian’s consistent maintenance of juewu, showing CCP progressiveness and model moral status in the community, which did not ebb because of his retirement. As a result, Mr. Tian proved himself morally dependable and qualified to work for the residents’ committee. Volunteering in the residents’ committee was considered one of the most advanced types of community volunteering among participants, since it represented a close and formal connection to the CCP that typically became loose and informal for retirees. Approximately 83% of our participants and all the participants who were CCP members volunteered in the residents’ committees or relevant managerial activities led by residents’ committees. They considered themselves “elite volunteers,” whose moral progressiveness and juewu distinguished themselves from fellow residents. For example, Mr. Chen, 74 years old, who had led the neighborhood watch program for over 8 years, said, “As a CCP member I should be a role model [for non-CCP members].” Through long-term community volunteering, older CCP members demonstrated that their sense of progressiveness was still robust enough to lead fellow residents, regardless of their retirement.

Notably, non-CCP member participants also sought affirmation of their moral progressiveness through community volunteering. For example, 70-year-old Mrs. Shen was proud that her juewu was recognized by the local party branch director to be as solid as that of a CCP member. Participants asserted that volunteering in the community expressed their progressiveness and encouraged fellow residents to attain similar status. As such, participants continued to pursue the CCP’s progressive agenda by demonstrating their juewu through volunteering.

A Sense of Authority

Some participants (45%) further noted fellow residents’ trust and support for their volunteering as a positive response to their juewu. For example, 72-year-old Mrs. Wu, who had been a building leader (lou zu zhang 楼组长) for almost 20 years, was very proud of her credibility when mediating disputes among neighbors:

When there are disputes, it is my turn to step in. There is no need to call on the residents’ committee to officially intervene. [All the neighbors] know what kind of person I am so they give me honor [“face”] and stop arguing once I am present.

Neighbors’ trust in Mrs. Wu to resolve disputes was based on her long-term volunteering in the building and the community, which demonstrated her strong juewu. A consensus emerged in participants’ responses that long-term volunteering strengthened their model moral status in the community, which in turn earned them high credibility and respect among neighbors, thus establishing their authority.

Participants’ sense of authority also related to their mission of generativity, that is, guiding the younger generations to commit to the public good for the long run. For example, 75-year-old Mr. Qian, who had led a photography interest group for over a decade, was concerned about the sustainability of volunteering in the community:

Our generation has a strong commitment to the public good… Broadly speaking, [volunteering] is a part of Chinese culture and virtue. In reality, however, there are far fewer young people joining in, not even those who have just retired.

Gradually, juewu distinguished participants with conscience and model moral status. Their long-term volunteering and juewu helped them establish model moral status for fellow residents and younger generations.

A Sense of Enjoyment

In addition to their sense of progressiveness and authority, juewu also brought a sense of enjoyment for participants during their long-term volunteering. Recognition of their efforts from fellow residents and community officials validated participants’ values and self-esteem. This realization brought participants genuine enjoyment. For example, 65-year-old Mr. Gao, who had volunteered in the community trash-sorting group for 5 years, commented:

[Volunteering] is altruistic and we have to have the juewu to devote to the community and sacrifice our own time, and that is altruistic. At the same time, I find such juewu and my [volunteering] effort make me [feel] very happy and worthwhile.

For participants, juewu indicated not only their devotion to community, model moral status, and continual contribution to the CCP mission and generativity, but also feelings of pleasure and satisfaction during volunteering. As Mr. Gao described his long-term contribution, “Volunteering has already been growing on me.” This attachment to volunteering suggests the enjoyment ingrained in volunteering. As such, juewu became a fusion motivation, combining characteristics of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and sustaining participants’ long-term volunteering.

Leading Community Self-Governance Initiatives

Juewu distinguished participants from shorter-term volunteers and fellow residents in the community by validating participants’ moral qualification to serve as spokespersons for fellow residents. The recognition and validation of their volunteering efforts also reinforced their enjoyment. As a result, participants were actively involved in the community affairs and willingly led community self-governance groups. For example, Mrs. Fang, who was 66 years old and had been the leader of a parking management group for over 8 years, recounted:

[Our group] has worked hard to ensure fairness in parking. When there are disputes over parking spaces in the community, neighbors don’t turn to the property management company, don’t turn to the residents’ committee, don’t turn to the homeowners’ association, they turn to me. They trust me. Working for my neighbors is my responsibility and at the same time I’m enjoying it very much.

Long-term volunteering made participants well aware of their neighbors’ needs and concerns and enabled them to advocate for their neighbors. Participants’ model moral status earned them the trust of fellow residents, which became the cornerstone of participants’ active role in community affairs.

Participants’ strong juewu and well-earned credibility also brought them enduring standing in the community, as validated by residents’ committees and the local CCP branches. Participants devoted themselves to community self-governance initiatives to oversee and monitor community affairs. For example, Mr. Zhao, who was 68 years old and had led a neighborhood coalition for 7 years, shared his opinion:

It’s actually very difficult to deal with community affairs. Things happen every day. Officials from our residents’ committee often work overtime. They don’t have much power or money to officially intervene. Compared with them, we [older volunteers] have [built] more rapport and trust to negotiate with fellow residents.

Leading self-governance initiatives, participants undertook the responsibility of negotiating and intervening in community affairs by communicating with fellow residents and on behalf of residents’ committees. As opposed to going through official channels, participants believed that their unique position––connecting both residents and residents’ committees––fostered a harmonious atmosphere for the community. For example, 69-year-old Mr. Sun described how self-governance groups bridged relations between the residents’ committee and fellow residents in his community:

Self-governance groups connect our residents’ committee with fellow residents. As volunteers, we execute the residents’ committee’s decisions and [provide a] voice for fellow residents. We mediate between residents and officials.

With their reputation as “model citizens,” established through long-term community volunteering, these dedicated older volunteers’ became increasingly identified with juewu and eventually became self-motivated to devote themselves to community self-governance initiatives. Participants’ long-term volunteering experiences demonstrated that they were morally dependable, and both fellow residents and community officials trusted them. Such validation, in turn, consolidated their motivation to stay involved in community affairs and recognize their unique position to lead self-governing community initiatives.

An Evolving Motivational Process for Long-Term Community Volunteering

Participants’ motivation to volunteer evolved with their long-term volunteering experiences, from adjusting to retirement life to demonstrating juewu, a fusion motivation combining characteristics of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations; participants increasingly assimilated their volunteer identity and took their unique positions in leading community self-governance initiatives.

Specifically, all participants reported that they had begun volunteering because they wanted to better adapt to life after retirement (extrinsic motivation) and enjoy themselves (intrinsic motivation). Volunteering in the community allowed them to continue social engagement and personal growth. Participants’ ethos and model moral status (i.e., a sense of progressiveness) received validation from officials of local CCP branches and residents’ committees (extrinsic motivation). Earning credibility and accountability among fellow residents, participants’ sense of authority continued to grow as they became actively involved in managing community affairs. Their progressiveness and authority were recognized by community officials and fellow residents (extrinsic motivation), which reinforced participants’ enjoyment of volunteering (intrinsic motivation). In this sense, juewu combined characteristics of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, giving participants further incentive to devote themselves to volunteering and eventually leading community self-governance initiatives. Thus, participants’ motivation to volunteer evolved with their volunteering experience as they further assimilated their volunteer identity.

Discussion

This study explored older adults’ experiences and motivations for long-term community volunteering in Shanghai. Informed by SDT, our findings shed light on the evolving motivational process of these long-term, dedicated volunteers. When participants began volunteering, extrinsic and intrinsic motivations coexisted. Participants relished volunteering and believed it would help them adapt to life after retirement, including achieving self-realization and maintaining social connections, as well as leaving meaningful legacies for younger generations. Over time, participants developed juewu as a fusion motivation, combining characteristics of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, which sustained their volunteering commitment and encouraged them to lead community self-governance initiatives.

Juewu as a Fusion Motivation

Juewu combines characteristics of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, thus becoming a fusion motivation in the motivational process. It sustained participants’ long-term dedication to community volunteering and distinguished participants from fellow volunteers and residents by their model moral status and credibility. Consistent with previous studies, juewu was essential to long-term community volunteering in China (Bray, 2006).

In terms of its extrinsic characteristic, juewu consolidated participants’ progressiveness and authority in the community, reflecting a widely held belief that community volunteering is “the best type of political-ideological work” (Luova, 2011, p. 781). Because volunteering is itself “a rewarding experience” (Cnaan & Goldberg-Glen, 1991, p. 281), in this study we conceptualize juewu as a reward system––consisting of moral rewards evaluated and conferred by the community. This could be related to the Chinese term biaoxian (表现), meaning “a broad realm of behaviors and attitudes subject to leadership evaluation” (Walder, 1986, p. 132). Walder (1986) conceptualized biaoxian as a financial and material reward system for employees’ work performance––including work attitudes, political loyalty, and morality––as evaluated by leaders in Chinese work units (Walder, 1986). We suggest that in the community volunteering context, juewu may serve the function of biaoxian; that is, juewu provides socially recognized moral rewards for participants (Li, 2008; Xu & Ngai, 2011).

Participants’ robust juewu contributed to their reputation and credibility, which legitimized their leadership of community self-governance initiatives––a socially recognized moral reward. Their devotion to community self-governance initiatives “embodies a substantial ethical element… raising the moral ‘quality’ of urban citizens” (Bray, 2006, p. 533). Compared to volunteering in interest and activity groups for recreational purposes, participants reported that volunteering in community self-governance initiatives better allowed them to manifest their usefulness and sense of purpose. They valued such opportunities for advancing the CCP’s mission and social generativity by serving as a point of connection between the government and their fellow residents (Lee & Zhang, 2013; Luova, 2011; Read, 2012).

Notably, juewu also cultivates participants’ social connections, which are important to managing community affairs and influencing fellow residents. Personal bonding with fellow residents allowed volunteers to better facilitate community volunteering (Dury et al., 2020; Finkelstein, 2010). Based on their proven selflessness, helpfulness, and fairness, participants were able to resolve disputes in the community without formal interventions by police or residents’ committees, thus leveraging their authority to manage community affairs (Lee & Zhang, 2013).

In terms of its intrinsic characteristic, juewu reinforced participants’ enjoyment of volunteering. Their long-term devotion to the community demonstrated their model moral status, trustworthiness, and values, which were validated by residents’ committees, local CCP branches, and fellow residents. Such recognition and validation supported their continual personal growth, which further amplified their enjoyment of volunteering. Participants found that volunteering was not only extrinsically rewarding, but intrinsically interesting (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Given their long-term volunteering experiences in community self-governance initiatives, participants’ motivations evolved and formed a motivational process. Compared with previous research, the findings of this study suggest that types of motivation to volunteer may not be completely extrinsic or intrinsic, but can be a fusion of the two. Thus, the underlying motivational process of long-term community volunteering among older adults in Shanghai was dynamic and nuanced.

Collectivist Social Context and Community Volunteering in urban China

Participants’ long-term volunteering experiences and continual contribution may stem from the interaction between motivation and the Chinese collectivist sociocultural context. Collectivism has been found to be related to continuous volunteering (Jiang et al., 2018). Viewed from a life-course perspective (i.e., how older adults’ earlier experiences influence their later life; Elder et al., 2015), participants tended to juxtapose their volunteering experiences with their earlier experiences in work units; through volunteering, participants sought a sense of belonging in their community that they formerly attributed to their work unit. This sense of belonging can help volunteers foster a community identity (Author, 2020), express their collectivist values (Duan & Wang, 2010), and take ownership of community governance goals (Bray, 2006). This collectivist view of volunteering reflected the collective self—vs. the individual self—an identity driven by shared goals to improve the quality of communal life (Bray, 2006; Xu, 2007). Collective community identity of volunteers has also been found to have implications for volunteers’ intention to volunteer in Saudi Arabia, also a collectivist country (Jiang et al., 2018).

Notably, participants’ early lives coincided with the most collectivist period of Chinese history (i.e., 1949–1979; Dahlman & Aubert, 2001). These older volunteers still felt honored to work for the CCP and a collective good (Lee & Zhang, 2013). Participants’ previous experiences in work units may have led them to perceive juewu in their communities similarly after retirement. Since volunteering behaviors and motivations should be assessed within generational contexts (Chambré & Netting, 2018), it remains to be seen if juewu and the moral reward system will continue to motivate younger generations in China to volunteer in their communities.

This collectivist ethos may also relate to participants’ concerns about the generativity of community volunteering in urban China. Participants reported that volunteering embodied Chinese collectivist culture and that this culture can offer meaningful guidance for younger generations, echoing previous findings that older Western volunteers were motivated by generativity (Morrow-Howell, 2010; Wilson, 2012).

Study Limitations

We should interpret our study’s findings in light of its limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional, meaning that we only know what participants thought of volunteering at the time they were interviewed. Longitudinal investigation is needed to establish a holistic understanding of commitment to community volunteering. Second, we did not interview anyone who had stopped volunteering in their community or who had never volunteered at all. These groups may have different views on volunteering that could enhance our understanding of why people choose to volunteer (or not). Third, this study took place in Shanghai, where community self-governance models are relatively popular compared with other places in China. Thus, our findings may not be broadly applicable across China. Although qualitative research aims to obtain rich data to explore the uniqueness and depth of social phenomenon whereas not focusing on representativeness, the findings of our study can inform future large sample quantitative studies.

Conclusion

Informed by SDT, this study explored older adults’ evolving motivational process during their long-term community volunteering experiences in Shanghai. Participants credited juewu, a fusion motivation combining characteristics of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, with motivating them to commit to long-term community volunteering to express their values and promote generativity. The credibility and trust they earned from local CCP branches, residents’ committees, and fellow residents allowed participants to lead community self-governance initiatives. This study provides insights for applying SDT to understand the nuanced dynamic of the motivational process of long-term community volunteering in urban China.

Availability of Data and Material

The data are not shared.

Notes

Qualitative research methods need ethical approval from the university because researchers have direct contact with human subjects. The ethical approval ensures the study procedures comply with all the ethical rules to protect human subjects.

The interview guide is available in an online supplemental appendix to this article.

References

Chen, L., Ye, M., & Wu, Y. (2020). Shaping identity: Older adults’ perceived community volunteering experiences in Shanghai. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49, 1259–1275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020911205.

Bidee, J., Vantilborgh, T., Pepermans, R., Huybrechts, G., Willems, J., Jegers, M., & Hofmans, J. (2013). Autonomous motivation stimulates volunteers work effort: A Self-Determination Theory approach to volunteerism. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24, 32–47.

Bray, D. (2006). Building ‘community’: New strategies of governance in urban China. Economy and Society, 35, 530–549.

Bruno, B., & Fiorillo, D. (2016). Voluntary work and wages. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 87, 175–202.

Chambré, S. M., & Netting, F. E. (2018). Baby boomers and the long-term transformation of retirement and volunteering: Evidence for a policy paradigm shift. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37, 1295–1320.

Chen, H., & Adamek, M. (2017). Civic engagement of older adults in mainland China: Past, present, and future. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85, 204–226.

China National Committee on Aging. (2008). White paper of China’s aging undertakings. Retrieved from http://www.cnca.org.cn/en/iroot10075/4028e47d18edb7d401190901aefd098b.html [Chinese]

Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs. (2000). The Ministry of Civil Affairs’ views on promoting urban community building throughout the nation. Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Choi, K., Stewart, R., & Dewey, M. (2013). Participation in productive activities and depression among older Europeans: Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(11), 1157–1165.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., et al. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1516–1530.

Cnaan, R. A., & Goldberg-Glen, R. S. (1991). Measuring motivation to volunteer in human services. The Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 27, 269–284.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE.

Dahlman, C. J., & Aubert, J. E. (2001). China and the knowledge economy: Seizing the 21st century. World Bank Publications.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what’’ and “why’’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49, 14–23.

Duan, S., & Wang, F. (2010). A qualitative study on Chinese older adults’ motivations to volunteer. Hebei University Xue Bao (Philosophy and Social Science), 35, 121–125. [Chinese].

Dury, S., Brosens, D., Smetcoren, A. S., Van Regenmortel, S., De Witte, N., De Donder, L., & Verté, D. (2020). Pathways to late-life volunteering: A focus on social connectedness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49, 523–547.

Elder, G. H., Shanahan, M. J., & Jennings, J. A. (2015). Human development in time and place. In M. H. Bornstein & T. Leventhal (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 665–715). Psychology Press.

Finkelstein, M. (2009). Intrinsic versus extrinsic motivational orientations and the volunteer process. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 653–658.

Finkelstein, M. (2010). Individualism/collectivism: Implications for the volunteer process. Social Behavior and Personality, 38, 445–452.

Fiorillo, D. (2011). Do monetary rewards crowd out the intrinsic motivation of volunteers? Some empirical evidence for Italian volunteers. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 82, 139–165.

Fiorillo, D., & Nappo, N. (2017). Formal volunteering and self-perceived health. Causal evidence from the UK-SILC. Review of Social Economy, 75, 112–138.

Gonzales, E., Matz-Costa, C., & Morrow-Howell, N. (2015). Increasing opportunities for the productive engagement of older adults: A response to population aging. The Gerontologist, 55, 252–261.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE.

Guo, W. H. (2010). The soft control of the state will on community public affairs: An expansion on Philip Huang’s concept of “the third realm between state and society. Open Times, 2, 60–82. [Chinese].

Han, A., Brown, D., & Richardson, A. (2019). Older adults’ perspectives on volunteering in an activity-based social program for people with dementia. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 43, 145–163.

Haski-Leventhal, D., & Cnaan, R. A. (2009). Group processes and volunteering: Using groups to enhance volunteerism. Administration in Social Work, 33, 61–80.

Hayakawa, T. (2014). Selfish giving? Volunteering motivations and the morality of giving. Traditiones, 43, 15–32.

Heberer, T., & Göbel, C. (2011). The politics of community building in urban China. Routledge.

Jiang, G., Garris, C. P., & Aldamer, S. (2018). Individualism behind collectivism: A reflection from Saudi volunteers. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations., 29, 144–159.

Lee, C. K., & Zhang, Y. (2013). The power of instability: Unraveling the microfoundations of bargained authoritarianism in China. American Journal of Sociology, 118, 1475–1508.

Li, H. (2008). Social reward and activists in Chinese urban communities: A case study of the building leaders (louzuzhang) in community, Shanghai. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 28, 97–117. [Chinese].

Li, Y., Xu, L., Chi, I., & Guo, P. (2013). Participation in productive activities and health outcomes among older adults in urban China. The Gerontologist, 54, 784–796.

Lin, S. L. (2001). Party building in the community: The new starting point for Chinese politics. Shanghai Party History and Party Building, 03, 11–14. [Chinese].

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Liu, H., & Lou, V. W. (2017). Patterns of productive activity engagement as a longitudinal predictor of depressive symptoms among older adults in urban China. Aging & Mental Health, 21, 1147–1154.

Liu, H., & Lou, W. Q. (2016). Patterns of productive activity engagement among older adults in urban China. European Journal of Ageing, 13, 361–372.

Luova, O. (2011). Community volunteers’ associations in contemporary Tianjin: Multipurpose partners of the party-state. Journal of Contemporary China, 20, 773–794.

Morrow-Howell, N. (2010). Volunteering in later life: Research frontiers. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 65, 461–469.

Morrow-Howell, N., & Wang, Y. (2013). Productive engagement of older adults: Elements of a cross-cultural research agenda. Ageing International, 38, 159–170.

Morse, J. M. (2015). Data Were Saturated. Qualitative Health Research, 25, 587–588.

Nappo, N., & Fiorillo, D. (2020). Volunteering and self-perceived individual health: Cross-country evidence from nine European countries. International Journal of Social Economics, 47, 285–314.

Nencini, A., Romaioli, D., & Meneghini, A. M. (2016). Volunteer motivation and organizational climate: Factors that promote satisfaction and sustained volunteerism in NPOs. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 618–639.

Oostlander, J., Güntert, S. T., Van Schie, S., & Wehner, T. (2014). Leadership and volunteer motivation: A study using Self-Determination Theory. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43, 869–889.

Peng, D., & Fei, W. (2013). Productive ageing in China: Development of concepts and policy practice. Ageing International, 38, 4–14.

People.cn. (2013). Xi Jinping’s four “Can and Cannot” become the standards of Chinese Communist Party members’ progressives. Retrieved August 10, 2021 from http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2013/0109/c241220-20144206.html [Chinese]

Read, B. (2012). The roots of the state: Neighborhood organizations and social networks in Beijing and Taipei. Stanford University Press.

Russell, A. R., Nyame-Mensah, A., de Wit, A., & Handy, F. (2019). Volunteering and wellbeing among ageing adults: A longitudinal analysis. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30, 115–128.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (2008). Volunteerism: Social issues perspectives and social policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 2, 1–36.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE.

Taghian, M., Polonsky, M. J., & D’Souza, C. (2019). Volunteering in retirement and its impact on seniors’ subjective quality of life through personal outlook: A study of older Australians. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30, 1133–1147.

The China Story. (2013). Suzhi. Retrieved August 10, 2021 from https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/yearbook-2013/introduction-engineering-chinese-civilisation/suzhi-%e7%b4%a0%e8%b4%a8/ [Chinese]

Tomba, L. (2014). The government next door. Cornell University Press.

van Ingen, E., & Wilson, J. (2017). I volunteer, therefore I am? Factors affecting volunteer role identity. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46, 29–46.

van Schie, S., Güntert, S. T., Oostlander, J., & Wehner, T. (2015). How the organizational context impacts volunteers: A differentiated perspective on self-determined motivation. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 1570–1590.

Walder, A. G. (1986). Communist neo-traditionalism: Work and authority in Chinese industry. University of California Press.

Warburton, J., Paynter, J., & Petriwskyj, A. (2007). Volunteering as a productive aging activity: Incentives and barriers to volunteering by Australian seniors. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 26, 333–354.

Warburton, J., & Winterton, R. (2017). A far greater sense of community: The impact of volunteer behaviour on the wellness of rural older Australians. Health & Place, 48, 132–138.

Weenink, E., & Bridgman, T. (2017). Taking subjectivity and reflexivity seriously: Implications of social constructionism for researching volunteer motivation. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28, 90–109.

Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42, 176–212.

Wu, Y., Li, C., & Khoo, S. (2016). Predicting future volunteering intentions through a Self-Determination Theory perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1266–1279.

Xiao, L. (2011). The “study of community” and “community studies”: A review of recent research on urban community in China. Sociology Studies, 4, 185–208. [Chinese].

Xie, L. (2015). Volunteering and its impact on self-identity: Results from Chaoyang District in Beijing. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 25, 170–181.

Xu, Q. (2007). Community participation in urban China: Identifying mobilization factors. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36, 622–642.

Xu, Y., & Ngai, N.-P. (2011). Moral resources and political capital: Theorizing the relationship between voluntary service organizations and the development of civil society in China. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(2), 247–269.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Pringle, Yijia Jing, Xue Li, Lan Zhang, and Qianfeng Wu for their comments and suggestions. Previous versions were presented in workshop of frontier China studies, LSE-Fudan Research Centre for Global Public Policy, Fudan University, and community research workshop in Department of Sociology, Fudan University.

Funding

The research is supported by National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences (CN), Fund for Young Scholars, “Community Power Structure, Social Capital Building and Implications for Governance” (19CSH005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Lin Chen and Felicia F. Tian. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lin Chen, and both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Tian, F.F. Evolving Experience and Motivation of Older Adults’ Long-Term Community Volunteering in Shanghai. Voluntas 34, 313–323 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00471-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00471-w