Abstract

In this case study, we aimed to investigate residents’ agency through their participation in the development of their residential area in the city of Espoo, Finland. With the aid of seven themes, we identified by thematic analysis five types of residents in terms of agency: free floaters, home troops and helpers, representative information brokers, informed reviewers, and change agents. Relational agency, rooted from the cultural-historical activity theory, necessitated recognizing the available resources, understanding the motives of others, and collaborating in joint activities. The results of 30 interviews showed that residents are willing to participate, and they need space and structure to exploit their relational agency in order to build common interests in their neighbourhood. The findings are discussed with reference to the potential of residents’ agency while participating in neighbourhood governance and volunteering. Our study contributes to the understanding of residents’ relational agency in community development and in volunteering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Participation as a practice is usually located in community development and collective action for social change carrying a desire of social justice and a sustainable world. It has a liberating potential involving a process of becoming critical, gaining autonomy, and ending up in empowerment (Ledwich and Springett 2010). Participation is interconnected with power and democracy; it manifests an open culture in which to debate and the possibility for citizens to exercise such agency that they can be involved in decisions, which affect them. Community development is understood as a process that facilitates participation and agency of members of communities, and especially putting the needs of the disadvantaged people at the core (Bhattacharyya 1995). It obtains social justice through means of collective action and believes in participatory democracy. Citizens’ social connectedness with their communities occurs through political, civic, and religious participation. Putnam (2000) explicated that expressing views, exercising rights, contacting officials, discussing politics, joining campaigns, signing petitions, and voting in elections are activities that have traditionally been used to bring citizens together and embody their social capital. However, all of this has declined rapidly, while less formal, voluntary civic participation involving a growing number of mailing-list memberships, for example, has increased.

The term “third sector” is increasingly used, in constant change, and confused with the bordering domains of community, market, and state; thus, the concept of hybridity describes its nature and helps to explore it (Billis 2010; Brandsen et al. 2005). Global civil society is defined as “the sphere of ideas, values, institutions, organizations, networks, and individuals between family, state, and market operating beyond the confines of national societies, polities, and economies” (Anheier et al. 2001:17). The growing civil society sector is a space of organized, private, non-profit-distributed, self-governed, of public benefit, and voluntary activities between institutions and citizens across the globe (Lewis 2005; Salamon 1999). Salamon and Sokolowski (2016) have proposed an extended conception of this blur third sector to empower the multiple activities operating in this social space, adding TSE “the third or social economy sector” (cooperative enterprises, mutuals, associations, and public-benefit foundations), to the third sector. This broadens the core and amount of individuals’ choices to take part in voluntary basis to social activities, such as community improvement, public, cultural and religious events, promoting health, safety, or education, taking care of the environment and the nature, providing emergency relief, helping people in need, organizing a demonstration or advocacy campaign, and providing professional work for free (Salamon and Sokolowski 2016). Indeed, the definition and the growing importance of the third sector relate to the development of the volunteering in a community.

Individuals need the capacity and power to make a difference in the pre-existing state of affairs. Agency refers to an intentional act that the actor knows, or believes, will have a particular outcome, and in which knowledge is utilized by the actor in order to have an outcome (Giddens 1984). Intentions alone are not yet sufficient to enact actions. Self-efficacy, meaning people’s beliefs in their capacity to produce desired results and forestall detrimental ones by their own actions, is the most pervasive determinator of personal agency (Bandura 2001). Personal agency helps individuals to shape their environments but is not yet sufficient to achieve all individuals’ goals. This raises the concept of relational agency, which gives us the possibility to examine individual and collective elements of agency: expanding personal agency to acting together with others (Edwards 2005; Edwards and D’Arcy 2004). We claim that agency goes beyond conventional participation such as being informed and attending to decision-making; it consists of residents’ capacities to influence and understand the resources and possibilities of the current local circumstances enabling their involvement in community development and volunteering. The concept of relational agency, referring to a capacity to work and align with others, is particularly useful for understanding residents’ participation and volunteerism.

The purpose of this paper is to explore residents’ agency when they attempt to participate in and influence their neighbourhood’s development in the city of Espoo, Finland. More specifically, we aim to examine residents’ relational agency related to their activities, skills, relationships, and knowledge needed in exerting power upon things. We regard relational agency as a mediating structure and useful for understanding residents’ participation and volunteering. The paper asks the following research questions: (1) What needs do residents express in urban development? (2) How is residents’ agency manifested during the development of their residential area? (3) How do residents contribute to volunteering? The concepts of citizens’ participation, volunteerism, and agency are discussed, after which the research methodology and results of the analysis of the interview data are presented. “Discussion” section finalizes the paper.

Theoretical Foundations

From Participation to Volunteerism

Participation came into vogue with the emergence of urban renewal and antipoverty projects that aimed to better include excluded have-not citizens in society (Arnstein 1969). Sherry Arnstein (1969) used a ladder metaphor to describe citizens’ public participation in urban planning and decision-making. Her typology can be divided into three levels that illustrate the extent of citizen power. The first is non-participation, such as grassroots people being involved in neighbourhood councils or committees with no genuine power. The second is tokenism, meaning the first steps towards legitimate citizen participation allowing have-nots to hear and to have a voice, but with powerholders retaining the right to decide. The third is citizen power, which enables a sharing of decision-making responsibilities, a redistribution of power, and community control through negotiations between citizens and powerholders.

According to Gamble and Weil (1995), “citizen participation is an active and voluntary involvement of individuals and groups in changing problematic conditions in communities and influencing the policies and programs that affect the quality of their lives and the lives of other residents”. It serves two purposes: informing the public of government actions and allowing the public to participate in government decision-making processes (Berner 2001). Residents typically engage in their neighbourhoods by involvement in governance, by participation in neighbourhood improvement projects, and by involvement in collective action or mobilizing efforts. Involvement in collective efforts refers to participation in collaborative resident efforts to influence decision-making, such as engagement in neighbourhood block groups, citizens’ committees, or neighbourhood organizing efforts, while individual activism refers to the residents’ actions to express their neighbourhood concerns to key decision-makers. There is a need to build an active citizenry through engaging residents and maintaining a high level of involvement in neighbourhoods. It necessitates, besides residents’ individual activism and collective actions, collaboration between residents and local actors (Foster-Fishman et al. 2007). Collaboration between residents and local actors can serve as a vehicle to strengthen citizens’ knowledge and skills and thus promote active citizenry (Foster-Fishman et al. 2006). Although citizens’ participation and engagement in local decision-making processes has recently been increased, involving residents and maintaining them in community development is quite complicated, especially in terms of addressing social structural problems in deprived districts (Foster-Fishman et al. 2007; Wagenaar 2007).

Individual actors play an important role in community development and neighbourhood processes. The types of urban exemplary practitioners who make a difference in public sphere have been identified in many research, such as reflective practitioners (Schön 1983), deliberative practitioners (Forester 1999), street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky 1980), front-line workers (Durose 2009), everyday makers (Bang 2005; Bang and Sörensen 1999), everyday fixers (Hendriks and Tops 2005), and competent boundary spanners (Williams 2002). Durose et al. (2016) have explored fluid profiles of enduring, struggling, facilitating, organizing, and trailblazing practitioners who contribute in different ways in neighbourhoods, and expand the opportunities of the collaboration of urban governance and public administration. These practitioners are able alone and in collaboration positively influence the course of processes in the neighbourhood with their local knowledge, ways of working, networks, and skills (e.g. Van Hulst et al. 2012; Van Den Pennen and Van Bortel 2016).

Volunteering means giving time freely to activities which benefit another person (Wilson 2000), it has a positive impact on local communities (United Nations Volunteers 2012), and it is based on emotional and value-based activity (Haski-Leventahl and Bargal 2008). Snyder and Omoto (2008: 3–5) define it as “freely chosen and deliberative helping activities that extend over time, are engaged in without expectation of reward or other compensation and often through formal organizations, and that are performed on behalf of causes or individuals who desire assistance”. Volunteering focuses more on helping activities on individual basis, while activism is oriented more to social change (Markham and Bonjean 1995) by activists who have a collective identity linked to participation in a social movement or collective action (Bobel 2007). The social capital in the neighbourhood is build when citizens voluntarily collaborate together for the community sharing values, mutual understanding, and trust (Putnam 2000), and community associations are seen as means focusing on social relations mobilizing other assets of community (Mathie and Cunningham 2003).

Volunteer literature contributes to an understanding of volunteering in micro-level, such as the motives or the personal dispositions and characteristics of volunteers (Hustinx et al. 2010; Rochester et al. 2010), in meso-level focusing on how organizational factors affect volunteers collectively (Studer and Von Schnurbein 2013), and in macro-level, such as how societal values, government policies, and social capital affect volunteering (Haski-Leventhal and Cnaan 2009; Hustinx and Meijs 2011). The nature of volunteering has been examined through models of volunteering (Rochester 1999), according to volunteer group norms and identities (Haski-Leventhal and Cnaan 2009), and through identity types of volunteers (Grönlund 2011). While the traditional collective volunteering style refers to service ethic and duty to a local community, the present-day reflexive volunteering style is based on personal interests and needs. The relationship of social closeness and geographical distance has changed the nature and meaning of volunteering. Globalization and virtual volunteer communities have broadened the place- and group-based boundaries, as well as interconnected local volunteer actions and global concerns (Hustinx and Lammertyn 2003).

Relational Agency

The framework of cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) (Vygotsky 1978) helps us to understand the relationship between the individual and social context, mediated by cultural means and tools, and the interdependence of the object of activity and the object motives shaping our actions (Leontjev 1978) in collaborative learning. The object of an activity is a need-related moving target, which determines possible actions and gives a shape to the activity (Engeström 1999: 381, 2001). Motives arise out of the encounter between the need-state and object; the dialectical relationship between object and motive relates to how we interpret the object of our actions, and, further, how we engage with it (Edwards 2005). This refers to personal agency as well as relational agency. The concept of relational agency shifts the analytic focus from individual action to action with others. Edwards and D’Arcy (2004:147) defined relational agency as a “capacity to engage with the dispositions of others in order to interpret and act on the object of our actions in enhanced ways”. Edwards (2005:172) further defined relational agency as a “capacity to work with others to expand the object that one is working on and trying to transform by recognizing and accessing the resources that others bring to bear as they interpret and respond to the object”.

Relational agency refers to (a) the subject’s capacity to recognize that other people can be a resource, (b) interpreting what matters to others, (c) aligning one’s own thoughts and actions with those of others, and (d) bringing that interpretation to the interpretation of the joint object, and responding to it (Edwards 2005). It is not merely collaboration concerning a joint object, but also an ability to recognize how available resources can support one’s action as well as to use the support of others (Edwards and D’Arcy 2004). Edwards further described common knowledge and collaboration emerging in boundary spaces which enables understanding everyone’s values and the long-term purposes of practice, “knowing how to know who”, sharing knowledge, and being responsive. Boundary space can be considered an area where different motives and interpretations of the object of activity come into contact (Edwards 2011: 35).

Methods

Context of the Study

This paper is based on the analysis of the residents’ agency of their participation in the neighbourhood development in the city of Espoo, Finland. Local Government Act (1995) in Finland enhances public input prior to decision-making by incorporating the democratic principles of inclusiveness and by giving people the right to have a say. This provides several opportunities for citizens: to give feedback to and claim rectification from municipal decision-makers, to vote and be chosen for a position of trust in the municipality, to propose an initiative, to organize delegations, to follow and influence the progress of ongoing plans. In addition to legislation, many cities run projects in urban areas aiming to engage residents in developing regional government and strengthening their voices, agency, and interaction with communal decision-makers, thus promoting public involvement.

In urban planning processes, power is distributed alternately between residents, experts, and decision-makers in order to realize certain values, such as manifesting minorities’ voices and encouraging residents’ input in the design of urban environments (Mäntysalo 2005). However, it has been claimed that the planning processes are unclear, experts use jargon, and information for residents is inadequate. There is a need for more participatory approaches, which recognize the place-based local knowledge and expertise of residents (Staffans 2004).

The third sector, in Finland, is described a broad diversity of historically evolved types of voluntary-based associations, organizations, and foundations, ending up to the social enterprises of a legal basis where the volunteer work itself has a strong emphasis (Defourny 2014; Salamon and Sokolowski 2016). In the mentioned neighbourhood, the third sector consists of several organizations which run supporting activities for unemployed, people with mental illnesses, substance misuse, special housing needs, and immigrants.

Community and Participants

This study is part of the participatory action research (PAR) Caring and Sharing Networks project, aimed at examining and enhancing residents’ participation, and developing effective means for residents’, public servants’, and organizations’ collaboration in urban development. The project took place in one of the municipal districts of the city of Espoo, Finland. In terms of social and economic indicators, the district represents the least advantaged area of the city. The proportion of unemployed and uneducated persons, single-parent families, people with low income, and immigrants (23%) is higher than in other districts (Lehtinen 2016). The area is characterized by a poor reputation and multiple urban renewal projects. Concurrently, the participatory Espoo programme advances open decision-making, local activities, and the participation of different groups (A Participatory Espoo, 2016).

Thirty active residents were recruited through snowball sampling: 18 females and 12 males, aged 27–79 years. Nine interviewees were immigrants from Somalia, Russia, Ghana, Iraq, or Kosovo, most of them fluent in Finnish, and 21 interviewees represented the main population. Twenty participants were employed, seven were retired, and three were at home taking care of their children. Some participants were socially and politically active, members of neighbourhood organizations, or had responsibilities in voluntary work.

Data Collection and Interview Procedure

The residents’ interviews were part of the problem-definition and context-mapping phase of the action research process cycle, the goal of which was to gain an understanding of the citizens’ current community participation (Kemmis and McTaggart 2000). The data consisted of 30 residents’ audiotaped interviews, lasting from 31 to 134 min and yielding 28 h of transcribed data. The semi-structured interviews contained open questions on residents’ views of the residential area and their efforts to advance their interests in urban development and took place at interviewees’ homes or workplaces, a local library, the premises of NGOs, and a local park. In accordance with the PAR method, we considered the participants to be co-researchers, and the interviews were similar to open conversations where knowledge is exchanged. We carefully explained to participants the aim of the research and the voluntary nature of their participation and obtained their written informed consent.

Analytic Strategy

The data were analysed according to the steps of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). An inductive, bottom up analysis, using the semantic and explicit codable moments of the entire data, provided a way to recognize accurate reflections of the content and its surface meanings (Boyatzis 1998). The richly descriptive data provided a clear sense of residents’ thoughts, ideas, and concerns with respect to urban development in their residential area.

First, thirty interviews were transcribed verbatim, yielding 477 text pages with 12pt, Times New Roman, single spacing, right and left margins 2 cm, top and bottom margins 2.5 cm. We read the data through carefully to get a picture and initial ideas of the urban development in the area. During the diligent re-reading process, we underlined the meaningful ideas and parts of text, as well as took notes. Sharper attention was gradually focused on the residents’ actions, activities, interaction, and participation in their residential area. It is worth noting that we could not completely free ourselves from the prior knowledge we had gained through the parallel ongoing action research project. Second, we coded the data initially in a descriptive way, giving the code a meaningful name which identified the features of the data referring to the most basic elements regarding the phenomena. Coding was supported by a NVivo10 for Windows computer program, and each of the 70 codes had its own file filled with collated extracts demonstrating the code. Third, we read through the content of the codes, deleting or moving some extracts to other codes and giving them a short description and summary. The summaries served as tools to test the description and the name of the code. We emended the codes to more analytic ones, ending up with 48 final codes. Nine initial themes and five floating single issues were formed by grouping codes which seemed to belong together. Fourth, we carefully reviewed the themes with their extracts and formed meaningful patterns by moving some codes to more fitting themes to ensure that extracts within the themes cohered together. We re-read the whole data set to find additional data and make sure the themes were internally homogenous as well as separable from each other. At this point, we found an unexpected candidate theme, valid for several interviews and forming a coherent pattern. Fifth, we outlined and re-shaped the themes in a more systemic way. Contrasts in prevailing governance practices and residents’ scale of participation in urban development helped us to understand the dynamics of the themes and locate them on the map.

The interplay of the theoretical framework and observations on the data with the newly determined themes enabled us, in the sixth and final step, to understand the development of the area and elicit the emerging seven themes: (1) everyday activities in the neighbourhood, (2) common activities and community space, (3) contacting and networking, (4) intercultural issues in the residential area, (5) prevailing participation practices, (6) challenges in local urban development, and (7) possibilities for collaboration. We presented the themes with written stories and checked how they worked with the whole data and in relation to each other. As a result of the analysis, the main themes residents’ participation in local urban development and governance practices in local administration emerged (see Fig. 1).

Results

Agency Types of Residents in Local Urban Development

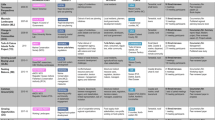

In the interests of developing our analysis more explicitly, we constructed five agency types of residents according to the content of seven themes. We organized the residents by scaling their participation with prevailing governance practices. In this way, we tried to capture residents’ relational agency, defined as an ability to work with others and align one’s motives with the motives of others. The analysis yielded five types of agency, with one having a subtype: free floaters, home troops and helpers, representative information brokers, informed reviewers, and change agents (see Fig. 2). We classified every participant in one agency type even though eight participants had features of two types and one participant of three types.

Free Floaters

These residents perceived their residential area as comfortable. The poor image and reputation of the area did not bother them, even though they mentioned it. They were interested in the reorganization and reconstruction of the area as it concerned their own apartments and lives. If something was not working, they made immediate phone calls or complaints to the municipality. They concentrated on keeping things stable, their participation was random, and their behaviour was mostly of either a demanding or defending nature.

Because we mothers are quite alone, the residential park is the most important meeting place for us, I see friends and we do things together in our free time…there are quite a lot of things to do here for single parents. (Kate)

I have been able to take care of the things myself. If I have problems, I think about who I can contact and then I make a phone call. (Nina)

Free floaters were satisfied as long as the circumstances remained unchanged. They acted only according to their personal relevance to the individual issues. They used conventional means of participating, and their agency was limited to reporting about the negative issues.

Home Troops and Helpers

This type consisted of two kinds of residents: home troops as a major type and helpers as a subtype. Similar life situations and activities connected them and led them to interact and discuss their interests. These residents wanted to improve their own lives and residential environment. They had the personal motivation to participate regarding small-scale everyday issues about their lives or neighbourhood. Usually, they managed to solve the problems alone, but if they had to make more effort they contacted their friends.

In our housing association’s meetings we write everything down in an official memo, such as problems in apartments and repairs needed, and then we send it to the house manager. (Ann)

Distinct from home troops, helpers assisted others in need when possible, but their activities did not expand any further due to the lack of a common motive and resources they were looking for. Helpers were mostly volunteers on an individual basis and members of local associations. They helped seniors, children in their homework, immigrants, and the lonely.

I do volunteer work in an association by supporting immigrant women who have just arrived to Finland and do not speak Finnish. We help them with daily routines, language and contacts. (Sally)

Home troops and helpers had a positive agency; they worked with others, and they helped each other and aligned their motives with the motives of others. They considered participation as a normal activity in everyday life, but to expand their agency further they would need common encounters to recognize and combine the resources around them. The need for a place of their own combined these groups: home troops wished for a place where they could run their activities in their free time, while helpers expressed a need for a place for their volunteering activities in their own turns.

Representative Information Brokers

These residents held influential positions in official decision-making systems or associations. They were close to the information sources and transferred messages and knowledge in many directions. Their aim was to promote the common good and well-being in the environment, and they maintained societal discussions in the local neighbourhoods. The main reason for their participation was their engagement in driving the interests of their own group. On the other hand, they felt an obligatory responsibility that was connected to their representative position. They were also involved in helping others on a voluntary basis due to their greater overview of people in need.

The city council work gives me much responsibility. I represent 13% of the population. If my people want to meet the mayor, it is easier for me as a city counsellor to arrange a meeting with him. (Ben)

It is my first term as a deputy counsellor. I have been able to give information and transmit messages to the counsellor. For example, I get a lot of calls; I am a link between residents and decision-makers. (Ashley)

Representative information brokers’ agency was based on their stable and regulated positions. They represented and repeated the conventional means of participating. They had a restricted agency; they were dependent on other residents’ social contexts and relationships, but were tied to the rules and were not capable of creating new ways to participate or systems of influence.

Informed Reviewers

These residents participated because they wanted to use their skills, expertise, and broad local knowledge to solve complex issues in their residential area. They were motivated by a high concern for social justice. They had long-lasting personal projects which they tried to promote by utilizing conventional official ways of participation as well as their wide networks. These residents were or had been in respectable positions, they had been involved in similar contexts earlier, and they were experts in utilizing relationships.

We have meetings with the mayor and now he is with us. We had a plan that the city should be involved; it works that way, and you have to have close contacts with political decision- makers. I have been a good networker since 1979. We have invited these influential people to our premises for discussions …It is amazing how they have never taken advantage of my knowledge. I have been a high school principal in this area for 30 years, and they’ve never asked me anything. And then they keep saying that residents do not participate! That is not true! (Robert)

These residents tirelessly acquired more information, were familiar with the bureaucracy, but did not necessarily win people to their side. They were involved in ongoing conflicts and contradictions, which had sometimes temporarily halted their progress, but which still fuelled their efforts to attain their goals. They claimed that they had been mistreated and stubbornly wanted to participate in the decision-making. Their stances were strong, and they referred to their experience which was not easily equalled. They were frustrated by slow, ambiguous, and laborious official procedures. They were critical of the conventional means of participation, but still repeated them. Concerning fairness, they expected new official rules, regulations, and procedures from the municipalities. They maintained a conversation on inequity between neighbourhoods with respect to resource allocation, accused the local media of one-sidedness, and claimed that even though residents were expected to participate in common activities, they were left without the means to do so.

I am a member of a residents’ forum. It is a “pretend democracy”. The principle is that we are given cases, and we kind of prepare them. Now we have 20 of them, and we fiddle with them, but they go no further. We have no real impact. (Steven)

There should be two-generation houses and apartments, with their own entrances. There should be seniors’ houses, student housing, and a conglomeration of senior citizens’ service facilities including commercial space for entrepreneurs, such as barbers and pedicurists. (Joan)

We have tried to organize a common space for all the youngsters, not only for immigrant youngsters. I have contacted the city mayor, parents, civil servants and the representatives of many immigrant groups. The process is slow, and I am worried about the integration of the second generation. (Josh)

Informed reviewers had good potential to participate, and their agency was based on their knowledge, experience, skills, and connections, and also on their own perseverance. They had many resources around them, but had difficulty aligning their motives with the motives of others, and integrating their knowledge with that of others as well.

Change Agents

These residents wanted to influence the structural development of the residential area through their far-reaching goals. They had been involved in larger-scale projects and movements by virtue of their broad networks. They wanted to influence political decision-making, attitudes, and social change at many levels and through many channels. They paid attention to collective interests and recognized the resources in the numerous social practices they were involved in.

I have always started from where things are the worst, and then improved on them. I always have basic human rights as a starting point. I am interested in how the law works in everybody’s case. If it does not work, I focus my attention on it. (Cecilia)

These residents noticed the worries and vulnerable situations of people in need and were able to set goals concerning them. Their goals were resident driven, practical, and accepted by many, and they were able to promote them through the associations. They considered issues like integration, multiculturalism, housing policy, and community space as empowering elements in the area. They regarded volunteer work as a powerful means to maintain the relations and connections they continuously needed in order to solve the problems of the area. They had good capabilities to reach their goals because of their local knowledge which they could offer and use effectively. Volunteer work and the reconstruction in the area served as a springboard for them to invite the city to collaborate.

We just started to develop things with different actors and organizations, it was my idea, and we got green light to the project when I was in the multicultural advisory board. Then we started to need help from other actors like third sector, associations etc. That is how it started. (Max)

I am active if it concerns my own hometown, my own neighbourhood. A person like me between two cultures can bridge people and things. I have always been interested and active. I could be a voluntary worker without compensation; I could take care of things, set up rules, and keep control. (Rose)

When there are difficult and complex processes like zoning, you have to learn it, you need straight channels, good contacts, and then you have to think about how it may affect your own area. (Brian)

I have immigrant mothers in my heart. Life has not always been easy…I was depressed after my first child, so I want to help those who have difficulties. (Lisa)

Change agents understood that they could solve complex problems by maintaining their unity, and in situations where resources were scarce they knew who could help. They were able to conceptualize and combine issues that mattered to everyone, which supported them in forming and expanding their long-term goals. Their timely local knowledge gave them the potential to respond more quickly than the official system, and they quickly mobilized their knowledge across the systems. They used their knowledge of the area’s specific problems as a means of becoming a legitimized partner in urban development. They sought collaboration with the city and had the resources to advance it.

Relational Agency as a Capacity of Residents

We defined relational agency as an ability to work with others and align one’s motives with the motives of others, and we tried to capture residents’ relational agency by scaling their participation with prevailing conventional and neighbourhood governance practices. In this way, we tried to understand their networks, resources, and abilities to align and work together. The interview data gave us some findings of residents’ expressions of the aspects of their relational agency.

The residents were able to do things alone, but they were also willing to collaborate with other residents. We found that the agency types of change agents and home troops, including helpers, had the capacity of relational agency. They were helpful residents who recognized the needs of others, gathered together to build a common understanding, and noticed the resources around them. By listening and understanding each other, they found the motives of others, were able to recognize what matters to everyone, and integrated the people and issues in an open deliberation, which mediated and maintained their collaboration.

The agency types of representative information brokers and informed reviewers worked close to the resources and networks, but they were bound to the vertical ways of influencing, which were not open for horizontal ways of deliberation. They were experts of many fields, but had difficulties to find alignments or agreements to solve the things with others. They were mostly involved in conventional governance practices, which did not give space to exploit their capacity of relational agency. The aspects of relational agency of free floaters were invisible in our findings.

Residents’ Contribution to Volunteer Work

It is important to recognize the residents’ agency types and their roles as a relevant urban partner from the perspective of volunteering and discuss them with regard to other typologies in previous research. In order to provide more understanding of the residents’ practice in an urban neighbourhood and to give depth to our research, we will introduce the residents as an asset in community development and voluntary work (see Table 1).

The descriptions show that residents had multiple experiences, skills, interests, and possibilities for volunteering. Most of them had a strong commitment and responsibility for the activities they participate. Free floaters were an exception; they need a motive to volunteer, and their interest has to be aroused before they become active.

Some of the home troops and helpers reminded “everyday makers” doing concrete things spontaneously themselves because they find it necessary (Bang and Sörensen 1999). Helpers’ resilient personality with social skills and positive emotionality (Atkins et al. 2005), emphatic concern (Einolf 2008), a relational motive (Prouteau and Wolff 2008), and enduring way of working tied them to volunteer work (Durose et al. 2016). These residents had a community identity being communal, loyal, and solidary (Grönlund 2011). One resident had a strong mission to improve and prepare the neighbourhood for future generations and pass on to them the prevailing existing knowledge (see Warburton and Gooch 2007).

Representative information brokers had a skill of agreeableness (Bekkers 2005) while negotiating between people, which fits to a volunteer worker. A sense of helpfulness and feeling responsible for the welfare of others related this group to volunteering (Penner 2002). The cultural and socioeconomic challenges of the own group triggered one resident to help voluntarily (Ecklund 2005).

Informed reviewers put a lot of effort over the course of years in order to empower and improve people’s situation and life in the neighbourhood with their struggling way of influencing (Durose et al. 2016). This group was energized by their tasks, and they had an ability to express themselves and a volunteer engagement drove their issues further (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). They had place-based social networks, multiple memberships in organizations, and earlier experience in volunteering, which increased their possibility to volunteer (e.g. Smith 1994). This group is related to collective volunteers with a dual identity (Haski-Leventhal and Cnaan 2009), one from their earlier affiliation, which they brought to a volunteering group.

Change agents had some characteristics of “everyday experts” being able to pay attention to the official political game while realizing their own plans (Bang and Sörensen 1999). They used “front-line workers’” strategies in neighbourhood; they identified the marginalized groups and engaged with them building skills and social networks between them (see Durose 2011). One resident reminded of the “boundary spanner” (Williams 2002) working between public administration, organizations, and residents gaining trust across the boundaries. Empathy with obligation to help people in need drove this group to volunteer work (Wilhelm and Bekkers 2010). Being an activist, values driven, fighting for justice and making the world a better place are indicators of “influencer’s” identity (Grönlund 2011), and they had the organizing profile (Durose et al. 2016). The social ties of this group improved trust which supported them to move forward and use their time to common good on voluntary basis (Brady et al. 1999). Change agents promoted the integrated approach, and they believed in the capacities of local residents and their associations to build powerful communities (Kretzmann and McKnight 1993). One resident had characteristics of “everyday fixer” who speaks for the neighbourhood, has personal commitment on justice issues, brings about changes, and brings others along (Hendriks and Tops 2005).

Relational Agency and Volunteerism

Residents’ relationships, networks, variety of resources, and abilities of supporting people, working together and aligning with the motives of others played a major role in residents’ volunteerism. They were characteristics for the relational agency of the residents as well. Volunteer work represented a participatory structure in neighbourhood governance enabling understanding each other’s’ values, sharing knowledge, and improving their capacity of relational agency. Thus, relational agency functioned as a mediating concept that necessitated a space of deliberation, and voluntary work provided a participatory arena for that.

Residents showed commitment, responsibility, social and emotional skills and values, and ability to work across boundaries, which are characteristics in both relational agency and volunteer work. The different residents’ agency types had different kinds of contribution to volunteer work. Some residents were able to draw upon the resources of others, align with the motives of others, and engage in volunteer work. Some residents were left without the collaboration with others, and their participation in community development and volunteering stayed low. Residents manifested the need of re-organizing the local volunteer work in ways which enabled the matters, motives, and dispositions of diverse residents and public administration to come into contact, and thus increased the participation of residents.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide insights into how residents’ build their agency in their efforts to participate and exert influence in their local community. A thematic analysis of 30 interviews formed a description of the residents’ actions in their neighbourhood, their experiences with current governance practices, and the agency needed when trying to make an impact in an urban development. Our findings delineated agency types of residents in terms of how residents draw upon resources, relations, rules, and ideas in urban development processes. Our special interest was to examine residents’ relational agency, defined as working with others and aligning one’s own motives with those of others (Edwards 2005; Edwards and D’Arcy 2004), as well as to reveal its possibilities to enable residents’ participation and volunteering in a neighbourhood.

The results of our study indicate that participation in neighbourhoods begins with resident’s small-scale actions in everyday life. Residents manifested a wide range of needs that were rooted in community development, such as strengthening the neighbourhood-based activities, re-organizing the volunteer work, understanding the cultural diversity of residents, and enhancing immigrants’ integration. To drive these topics further, residents needed the help of other residents to expand their agency to more collective ways of acting (see Foster-Fishman et al. 2006). Getting to know each other and each other’s motives required mutual trust and a sense-making process and called for common space where residents could meet and interact with each other. Challenges concerning local governance, such as the rules and slowness of conventional representative governance practices, inhibited residents’ agency as well as created an inability to recognize the resources and motives of others and form a joint object. The residents also manifested issues concerning urban development in their residential area, such as promoting structural development and planning new building models, but to push these things further they demanded new kinds of collaboration and participation practices with the municipalities in order to have a greater influence.

We see residents’ agency as emerging from the interaction between them and their environments. Agency is challenging in neighbourhoods undergoing many changes, such as reconstruction and infilling. Further, the bureaucratic approach of current governance can be obscure, which does little to steer residents’ issues in the right direction, not to mention its ineffective attempts to attract citizens’ voluntary involvement due to poor ways participation (see Chaskin 2005). There is a call for various types of residents’ agency in neighbourhoods, and our findings suggest that residents need relational agency to act collectively for change. Governance and participation practices are ambiguous and need structural changes based on collaboration to enable residents to exploit their capacity for relational agency.

Residents have significant skills, such as negotiating, communicating, and helping others, and they are able to get things done and keep things going in and around neighbourhood. Besides skills, they have values and ideas how to develop their neighbourhood. The importance of a common space and the sense of community were widely acknowledged by residents, and we suggest that a community centre could be a participatory place for different types of residents to build their relational agency by being together, understand the motives of others, and to enable residents’ engagement to volunteering as a neighbourhood practice. Residents could recognize common issues of concern as well as resources, and take collective action to promote collaborating with local actors. In order to use the potential of residents’ agency, combining their resources and practice-based local knowledge with cross-sectorial collaboration in public governance could allow for the cities to take advantage of active citizenry, reallocate resources, and increase citizens’ well-being in their communities (see Foster-Fishman et al. 2007; Wagenaar 2007).

Our results encourage to empathize the importance of volunteers, and the portraits of the residents could be useful for volunteering research and practice. The volunteer opportunities have a vital role bridging the participation of diversity of the residents with formal policy-making and thus building the social capital in the neighbourhood. Volunteering can provide relevant roles and arenas of responsibility for residents in social issues, and it can be beneficial for the whole community. Thus, volunteers can make a significant contribution to the neighbourhood.

Our study offers a novel contribution to the literature by applying the concept of agency, based on the CHAT (Vygotsky 1978), to the field of community and urban development. We consider residents’ agency as an effort to have an influence with respect to common concerns in the neighbourhood and community, and, in suitable circumstances, taking action to promote change. To expand their capacities, they need relational agency. Engaging with the dispositions of others is a process that involves recognizing others as resources, interpreting their motives, and responding to them. By understanding what matters to others (Edwards 2012), residents are able to build a joint object of their activities as a basis for their collaboration (Leontjev 1978). Relational agency can be seen as a structure building links between people and practices, and raising residents’ individual agency to collective agency.

In spite of its many strengths, the present study has certain limitations. Interviewing as a method enables acquiring direct knowledge of the phenomenon in question, but there are challenges related to having to stimulate interaction between interviewers and interviewees and having to establish a common understanding of the topic, reaching the right key informants, and the researchers’ positions and their influence with respect to the research. Second, according to the CHAT, agency and actions are to be studied in movement—following the participants in real social contexts. In this respect, the interview data were insufficient to draw overriding conclusions on residents’ agency. Further research is needed to investigate agency from other perspectives, for example an in-depth exploration of particular residents’ agency through their participation paths, and observing and revealing participating structures in the neighbourhood. Even though the present research focused on a single community, it can be considered most likely case with its resourceful participants. The contextual knowledge and understanding of behavioural patterns of residents in an appropriate sociocultural environment where that particular behaviour happens provide transferable results. These different types of residents can be representative of the diversity of the population, and the results can be relevant to other urban areas as well.

In conclusion, citizen collaboration in urban development necessitates the emergence of residents’ relational agency in community development. Relational agency is a mediating concept that accurately describes residents’ struggles towards collective action in neighbourhoods. Volunteers make a significant contribution to their neighbourhoods, while they gather troops, give a meaning to their activities and build identities for collaborating for common good.

References

A participatory Espoo. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.espoo.fi/en-US/City_of_Espoo/Decisionmaking/The_Espoo_Story/A_participatory_Espoo. Accessed 15 March 2017.

Anheier, H., Glasius, M., & Kaldor, M. (2001). Introducing global civil society. In H. Anheier, M. Glasius, & M. Kaldor (Eds.), Global civil society 2001 (pp. 3–22). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, 216–224.

Atkins, R., Hart, D., & Donnelly, T. (2005). The association of childhood personality type with volunteering during adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 51, 145–162.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

Bang, H. B. (2005). Among everyday makers and expert citizens. In J. Newman (Ed.), Remaking governance: People, politics, and the public sphere (pp. 159–178). Bristol: Policy Press.

Bang, H. P., & Sörensen, E. (1999). The everyday maker: A new challenge to democratic governance. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 21, 325–341.

Bekkers, R. (2005). Participation in voluntary associations: Relations with resources, personality, and political values. Political Psychology, 26, 439–454.

Berner, M. (2001). Citizen participation in local government budgeting. Popular Government, 66, 23–30.

Bhattacharyya, J. (1995). Solidarity and agency: Rethinking community development. Human Organizations, 54, 60–69.

Billis, D. (2010). Towards a theory of hybrid organizations. In D. Billis (Ed.), Hybrid organizations and the third sector: Challenges for practice, theory and policy (pp. 46–69). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Bobel, C. (2007). I’m not an activist, though I’ve done a lot of it: Doing activism, being activist and the ‘perfect standard’ in a contemporary movement. Social Movement Studies, 6, 147–159.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative analysis. Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brady, H., Schlozman, K. L., & Verba, S. (1999). Prospecting for participants: Rational expectations and the recruitment of political activists. American Political Science Review, 93, 153–169.

Brandsen, T., Van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or chameleons? Hybridity as a permanent and inevitable characteristic of the third sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28, 749–765.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Chaskin, R. (2005). Democracy and bureaucracy in a community planning process. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 24, 408–419.

Defourny, J. (2014). From third sector to social enterprise: A European research trajectory. In J. Defourny, L. Hulgård, & V. Pestoff (Eds.), Social enterprice and the third sector. Changing European landscapes in a comparative perspectives (pp. 17–41). New York: Routledge.

Durose, C. (2009). Front line workers and “local knowledge”: Neighbourhood stories in contemporary UK local governance. Public Administration, 87, 35–49.

Durose, C. (2011). Revisiting lipsky: Front-line work in UK local governance. Political Studies, 59, 978–995.

Durose, C., Van Hulst, M., Jeffares, S., Escobar, O., Agger, A., & De Graaf, L. (2016). Five ways to make a difference: Perceptions of practitioners working in urban neighborhoods. Public Administration Review, 74, 576–586.

Ecklund, E. (2005). Models of civic responsibility: Korean Americans in congregations with different ethnic compositions. Journal for the Scientific Study of the Religion, 44, 15–28.

Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43, 168–182.

Edwards, A. (2011). Building common knowledge at the boundaries between professional practices: Relational agency and relational expertise in systems of distributed expertise. International Journal of Educational Research, 50, 33–39.

Edwards, A. (2012). The role of common knowledge in achieving collaboration across practices. Learning, Culture, and Social Interaction, 1, 22–32.

Edwards, A., & D’Arcy, C. (2004). Relational agency and disposition on sociocultural accounts of learning to teach. Educational Review, 56, 147–156.

Einolf, C. (2008). Empathic concern and prosocial behaviors: A test of experimental results using survey data. Social Science Research, 37, 1267–1279.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Innovative learning in work teams: Analysing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R.-L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 377–404). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14, 133–156.

Forester, J. (1999). The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Cantillon, D., Pierce, S. J., & Van Egeren, L. A. (2007). Building an active citizenry: The role of neighborhood problems, readiness, and capacity for change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 91–106.

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Fitzgerald, K., Brandell, C., Nowell, B., Chavis, D., & Van Egeren, L. A. (2006). Mobilizing residents for action: The role of small wins and strategic supports. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 143–152.

Gamble, D. N., & Weil, M. O. (1995). Citizen participation. In R. L. Edwards (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social work (pp. 483–494). Washington, DC: NASW Press.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Introduction of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Grönlund, H. (2011). Identity and volunteering intertwined: Reflections on the values of young adults. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22, 852–874.

Haski-Leventahl, D., & Bar-Gal, D. (2008). The volunteer stages and transitions model: Organizational socialization of volunteers. Human Relations, 61, 67–102.

Haski-Leventhal, D., & Cnaan, R. S. (2009). Group processes and volunteering: Using groups to enhance volunteerism. Administration in Social Work, 33, 61–70.

Hendriks, F., & Tops, P. W. (2005). Everyday fixers as local heroes: A case study of vital interaction in urban governance. Local Government Studies, 31, 475–490.

Hustinx, L., Cnaan, R., & Handy, F. (2010). Navigating theories of volunteering: A hybrid map for a complex phenomena. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40, 410–434.

Hustinx, L., & Lammertyn, F. (2003). Collective and reflective styles of volunteering. A sociological modernization perspective. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14, 167–187.

Hustinx, L., & Meijs, L. C. P. M. (2011). Re-embedding volunteering: In search of a new collective ground. Volunteer Sector Review, 2, 5–21.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2000). Participatory action research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 567–605). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kretzmann, J., & McKnight, J. (1993). Building communities from the inside out. Chicago: ACTA Publications.

Ledwich, M., & Springett, J. (2010). Participatory practice. Community-based action for transformative change. Bristol: Policy Press.

Lehtinen, T. (2016). Espoo alueittain 2015: Analyysit teemoittain ja suuralueittain. Tietoisku 7/2016. [Espoo in districts 2015]. Espoo: City of Espoo.

Leontjev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lewis, L. (2005). The civil society sector. A review of critical issues and research agenda for organizational communication scholars. Management Communication Quarterly, 19, 238–267.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Local Government Act. (365/1995). Retrieved from http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1995/en19950365.pdf. Accessed 4 April 2017.

Mäntysalo, R. (2005). Approaches to participation in urban planning theories. In I. Zett & S. Brand (Eds.), Rehabilitation of suburban areas—Brozzi and Le Piagge neighbourhoods (pp. 23–38). Florence: University of Florence.

Markham, W., & Bonjean, C. (1995). Community orientation of higher-status women volunteers. Social Forces, 73, 1553–1572.

Mathie, A., & Cunningham, G. (2003). From clients to citizens: Asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development. Development in Practice, 13, 474–486.

Penner, L. A. (2002). Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism. An interactionist perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 447–467.

Prouteau, L., & Wolff, F. (2008). On the relational motive for volunteer work. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 314–335.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rochester, C. (1999). One size does not fit all: Four models of involving volunteers in small voluntary organizations. Voluntary action. The Journal of the Institute for Volunteering Research, 1, 7–20.

Rochester, C., Paine, A. E., Howlett, S., & Zimmeck, M. (2010). Making sense of volunteering: Perspectives, principles and definitions. In C. Rochester, A. E. Paine, S. Howlett, & M. With Zimmeck (Eds.), Volunteering and society in the 21st century (pp. 9–23). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Salamon, L. (1999). America’s non-profit sector: A primer (2nd ed.). New York: Foundation Center.

Salamon, M., & Sokolowski, W. S. (2016). Beyond non-profits: Re-conceptualizing the third sector. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1515–1545.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 25, 293–315.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

Smith, D. (1994). Determinants of voluntary association participation and volunteering. A literature review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23, 243–263.

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. (2008). Volunteerism. Social issues, perspectives and social policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 2, 1–36.

Staffans, A. (2004). Vaikuttavat asukkaat: Vuorovaikutus ja paikallinen tieto kaupunkisuunnittelun haasteina. [Influencing residents: Interaction and local knowledge as challenges of urban planning]. Espoo: Helsinki University of Technology.

Studer, S., & Von Schnurbein, G. (2013). Organizational factors affecting volunteers: A literature review on volunteer coordination. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24, 403–440.

United Nations Volunteers. (2012). Report of the secretary-general: Follow-up of the implementation of the international year of volunteers (2012). Retrieved from the www.unvolunteers.org/swvr2011. Accessed 22 May 2017.

Van Den Pennen, T., & Van Bortel, G. (2016). Exemplary urban practitioners in neighbourhood renewal: Survival of the fittest…and the fitting. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1323–1342.

Van Hulst, M., De Graaf, L., & Van den Brink, G. (2012). The work of exemplary practitioners in neighbourhood governance. Critical Policy Studies, 6, 434–451.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wagenaar, H. (2007). Governance, complexity, and democratic participation. How citizens and public officials harness the complexities of neighborhood decline. The American Review of Public Administration, 37, 17–50.

Warburton, J., & Gooch, M. (2007). Stewardship volunteering by older Australians: A generative response. Local Environment, 12, 43–55.

Wilhelm, M., & Bekkers, R. (2010). Helping behaviour, dispositional empathic concern and the principle of care. Social Psychology Quarterly, 73, 11–32.

Williams, P. (2002). The competent boundary spanner. Public Administration, 80, 103–124.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215–240.

Funding

The study is funded by The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland and the Ministry of Environment through the Development Programme for Residential Areas (2013–2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Research was conducted in accordance with research protocol concerning human participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lund, V., Juujärvi, S. Residents’ Agency Makes a Difference in Volunteering in an Urban Neighbourhood. Voluntas 29, 756–769 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-9955-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-9955-4