Abstract

Comparative research on nonprofit organizations (NPOs) has been a prominent approach for advancing our understanding of these organizations. This article identifies the primary drivers that shape the NPO comparative research agenda and explores new research trends. Based on a systematic literature review, nine definitional aspects and ten impulses are identified as drivers of NPO research. This article conducts a correspondence analysis to study the relationships between the definitional aspects and impulses that are discussed in 111 articles that were published in philanthropic and third-sector journals in the period January 2001–January 2015. Based on our results, we suggest three new clusters for future comparative research: investment and growth, participation and social impact, and social cohesion and civil society.

Résumé

La recherche comparative sur les organismes sans but lucratif nous a grandement aidés à mieux comprendre ces derniers. Le présent article identifie les principaux facteurs qui donnent forme aux programmes de recherche comparative sur les organismes sans but lucratif, et explore les nouvelles tendances dans le domaine. Dans le cadre d’une revue systématique de la littérature, neuf aspects définitionnels et dix besoins furent identifiés en tant que facteurs d’incitation à la recherche sur les organismes sans but lucratif. Le présent article procède à une analyse des correspondances dans le but d’étudier les relations entre les aspects définitionnels et les besoins dont il est question dans 111 articles qui furent publiés dans des journaux philanthropiques et du tiers secteur de janvier 2001 à janvier 2015. Nous proposons, en fonction de nos résultats, trois nouveaux groupes pour la recherche comparative ultérieure : investissement et croissance, participation et incidence sociale, et cohésion sociale et société civile.

Zusammenfassung

Vergleichende Forschungen zu Non-Profit-Organisationen sind ein verbreiteter Ansatz, um unser Verständnis über diese Organisationen zu erweitern. Dieser Beitrag ermittelt die Haupteinflussfaktoren, die die Agenda der vergleichenden Forschung zu Non-Profit-Organisationen gestaltet, und untersucht neue Forschungstrends. Beruhend auf einer systematischen Literaturauswertung werden neun Definitionsaspekte und zehn Impulse als Einflussfaktoren für die Forschung zu Non-Profit-Organisationen identifiziert. Man führt eine Korrespondenzanalyse durch, um die Beziehungen zwischen den Definitionsaspekten und den Impulsen zu untersuchen, die in 111 Artikeln in philanthropischen Journalen und Fachblättern des Dritten Sektors im Zeitraum von Januar 2001 bis Januar 2015 diskutiert wurden. Beruhend auf unseren Ergebnissen schlagen wir drei neue Gruppen für zukünftige vergleichende Forschungen vor: Investment und Wachstum, Partizipation und soziale Auswirkungen sowie sozialer Zusammenhalt und Bürgergesellschaft.

Resumen

La investigación comparativa sobre las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro (NPO, por sus siglas en inglés) ha sido un enfoque prominente para el avance de nuestra comprensión de dichas organizaciones. El presente artículo identifica los impulsores fundamentales que dan forma a la agenda de investigación comparativa de las NPO y explora nuevas tendencias de investigación. Basándonos en una revisión sistemática del material publicado, se identifican nueve aspectos definitorios y diez impulsos como impulsores de la investigación de las NPO. El presente artículo realiza un análisis de correspondencia para estudiar las relaciones entre los aspectos definitorios y los impulsos que se tratan en 111 artículos que fueron publicados en diarios filantrópicos y del sector terciario en el período de enero de 2001 a enero de 2015. Basándonos en nuestros resultados, sugerimos tres nuevos grupos temáticos o clusters para la investigación comparativa: inversión y crecimiento, participación e impacto social, y cohesión social y sociedad civil.

Chinese

非营利组织(NPO)比较研究已成为我们了解这些组织的重要方法。本文已列明制定非营利组织比较研究计划和探索最新研究趋势的主要驱动因素。基于系统性文献综述,九项定义内容和十种刺激因素被确认为非营利组织研究的驱动因素。本文通过对应分析,研究了慈善期刊与第三领域期刊在2001年1月至2015年1月期间发表的111篇文章讨论的定义内容和刺激因素之间的关系。根据我们的分析结果,我们建议,未来的比较研究采用三种新的组群:投资与增长、参与和社会影响、社会凝聚力与民间团体。

Arabic

البحث المقارن حول المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPOs) أصبح نهج بارز للنهوض بفهمنا لهذه المنظمات. تحدد هذه المقالة المحركات الرئيسية التي تشكل جدول أعمال البحوث النسبية للمنظمات الغير ربحية (NPO) وتستكشف إتجاهات البحث الجديدة. إستنادا” إلى إستعراض منهجي للأدبيات، تم تحديد تسعة جوانب للتعريف وعشرة نبضات كعوامل محركة لأبحاث المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPO). تجري هذه المقالة تحليل للمراسلات لدراسة العلاقات بين جوانب التعريف والنبضات التي نوقشت في 111 مقالة نشرت في مجلات خيرية وثالثة في الفترة من يناير/كانون الثاني 2001 إلى يناير/كانون الثاني 2015. إستنادا” إلى نتائجنا، نقترح ثلاث مجموعات جديدة من أجل البحوث المقارنة في المستقبل: الإستثمار والنمو، المشاركة والأثر الإجتماعي، والتماسك الإجتماعي والمجتمع المدني.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The purpose of comparative research is to “explain and interpret macro-social variation” (Ragin 1987, p. 5); comparative research identifies and explains the economic, political, sociocultural, and historical similarities and/or differences in a phenomenon across societies. The benefits of conducting a comparative study include conceptual refinement and insight into the specific and general forces underlying a phenomenon. Therefore, comparative research provides a useful tool for advancing our understanding of NPOs.

According to Casey (2016), comparative research on NPOs has expanded and several significant comparative projects have been launched since the 1990s, such as the Johns Hopkins Comparative NonProfit Sector Project and CIVICUS Civil Society Index. Casey explains that these projects have contributed to the development of cultural frameworks that are used to interpret NPOs across societies.

Nevertheless, a significant body of comparative research has developed outside these projects. Parallel to these projects, which garnered important academic and institutional support, scholars around the world have conducted comparative studies that were inspired by specific contexts and interests and have participated in the interpretation of NPOs across societies through their publications in major peer-reviewed journals in the NPO sector.

The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze the primary topics that drive NPO comparative research and explore new issues for future comparative studies. We evaluate 111 comparative articles that were published in 13 NPO-focused scientific journals and analyze the drivers that are defined in the literature as having laid the grounds for the development of the NPO comparative research agenda (Anheier and Salamon 2006; Anheier and Seibel 1990a; James 1987; Salamon et al. 1999).

Anheier and Salamon (2006) explain that the significant worldwide growth in the number and diversity of nonprofit organizations has increased the difficulty of defining the nonprofit phenomenon and has sparked debates regarding the socioeconomic, political, and cultural conditions that characterize NPOs in and across societies (Anheier and Seibel 1990b; Bauer 1990). These scholars highlight definitional aspects and macro-social impulses as the two primary drivers of debate in the NPO comparative field (Anheier and Salamon 2006).

In terms of the structure of comparative research, the definitional aspects refer to attributes that shape NPOs and impulses refer to attributes that shape societies. NPOs and societies are defined by configurations of their attributes. Paraphrasing Ragin (1987, p. 9), the configurations of NPOs and societies are interdependent and are the basis for the development of classifications that are used to test the patterns on which explanations rely. Articles from the study sample are used to illustrate this concept. In their article, Civic Sectors in Transformation and Beyond: Preliminaries for a Comparison of Six Central and Eastern European Societies, Rikmann and Keedus (2013) explain how changes in the political and socioeconomic attributes of Eastern European societies affected the configuration of attributes of NPOs and, ultimately, defined their distinctiveness. A further example is the article Corruption and NGO Sustainability: A Panel Study of Post-communist States, in which Epperly and Lee (2013) explain the variation in the configuration of NPOs (or the degree of sustainability in the NPO sector) in relation to variations of a set of attributes of post-communist states where corruption is a primary factor that affects NPO sustainability in these states.

Consequently, it might be expected that comparative research contributes to better understanding of macro-social variations by filtering and selecting relevant attributes and configurations. It would also be reasonable to expect that the definitional aspects and impulses of NPO comparative research that have been used for more than a decade would be increasingly refined and arranged in configurations to align groups of definitional aspects with groups of impulses.

A word of caution is necessary. Articles were selected that systematically identify attributes that relate to or differentiate two or more macro-social units (countries or regions); however, not all of the articles utilize the comparative method (Mills and De Bruijn 2006; Ragin 1987). Comparative research does not require the adoption of the comparative method (Ragin 1987; Ragin and Rubinson 2009), although the contribution to understanding a phenomenon may be weakened when, for example, quantitative methods are adopted without acknowledging the advantages of comparative methods, such as studying specific populations rather than theoretically constructed populations (Kittel 2006; Ragin 2006). Therefore, studies that apply the comparative method generally detail the complexities of a phenomenon and identify significant relationships of causality (Kittel 2006; Ragin 2006). Nevertheless, our focus is on the subjects that drive comparative research rather than on the evaluation of results; therefore, our criteria for selecting articles are broad.

This article is structured as follows. Comparative drivers are explained in the following section; the advances in socioeconomic impulses that are proposed by Anheier and Salamon are presented and extended by two additional impulses that are identified in the most recent studies: business partnerships and economic capital. The second section explains the methods that are applied for the analysis and describes the sample. The third section presents the results of the correspondence analysis, which indicate that definitional aspects have been increasingly incorporated in a comprehensive manner in studies that address recent advances in NPO impulses. The results also suggest that studies regarding social capital have developed differently than other impulses. In addition, the scope of definitional aspects, such as revenue, size, and distribution constraints, may be shifting away from managerial aspects and focusing more on market aspects because they are increasingly paired with economic impulses in NPO research. The conclusion explains that definitional aspects and impulses drive the comparative research agenda in an irregular manner; social capital and volunteering agendas have developed in slightly different directions than mainstream impulses and operational-definitional aspects, which have developed in a similar manner. Furthermore, the appearance of new impulses results in a transition of the integration of growth-definitional aspects in this area of research.

Framework for the Analysis of Comparative Drivers

The Nonprofit Sector Research Handbook (Powell 1987) was a landmark study regarding nonprofits because it laid the groundwork for the development of the NPO field. Estelle James’ (1987) contribution, The Nonprofit Sector in Comparative Perspective, captures the beginnings of comparative research on NPOs, and the first attempts to go beyond research in the USA are documented by Anheier and Seibel (1990a). Their list of major drivers for comparative research includes the choices about the public–private division in different countries, the development of the third sector, competitive advantages of nonprofits over the government or private companies, sources of financing and tax regulations, and the historic roots of NPOs. Both James (1987) and Anheier and Seibel (1990a) cite the lack of availability of data on the size, scope, and composition of the third sector as the most important obstacle for advancing comparative research. This gap was, to some extent, filled by the John Hopkins Comparative NonProfit Sector Project, which was the first large-scale research study (Salamon et al. 1999, 2004). This project compiled a systematic body of comparative data on NPOs, which has inspired numerous comparative research projects.

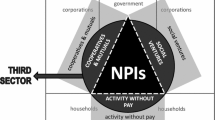

In a chapter in The NPO Sector. A Research Handbook (2006), Anheier and Salamon explain that the two main factors that have inspired comparative research on NPOs are definitional aspects and macro-social impulses. The first refers to how scholars describe and delimit a phenomenon to allow comparisons to be made. The second refers to broader discussions in society on the role of NPOs and the perspectives that scholars develop to define these roles. Definitional aspects have advanced because they have been analyzed from the perspective of different contexts and impulses. For example, the development of new NPO forms and their increasing commercialization have advanced the concept of using a non-distribution constraint to consider a partial constraint that has been applied in cases such as mutuals, cooperatives, and social enterprises (Salamon and Sokolowski 2014, 2016)Footnote 1. Consequently, our analysis seeks to identify how definitional aspects have been adopted in the study of impulses and to assess the extent to which the relationship between definitional aspects and impulses has changed as advances in impulses, and even new types of impulses have appeared on the NPO scene.

Definitional Aspects

To systemize the heterogeneous nature of nonprofits that operate in different countries, Salamon et al. (1999, p.3) developed an operational definition that includes five criteria (see 1 in Table 1):

Organization (org) refers to an organization’s degree of stability and institutionalization and implies that the organization has adopted an internal structure and has been formally recognized.

Private (prvt) implies that the organization does not represent a branch of government and is institutionally separate.

Self-governing (s-gov) implies that the organization’s operation and decision-making processes are independent from external government or corporate influences.

Distribution constraint (dist) According to this principle, NPOs are either entirely or significantly limited in their potential to return profits to patrons. Associations are organizations that have strict non-distribution constraints; however, mutuals, cooperatives, and social enterprises are examples of organizations that have significant distribution constraints.

Voluntary (vol-ry) This principle implies that participation is not compulsory but is a matter of choice.

In addition, Anheier and Salamon (2006, p.95) explain that this operational definition highlights four different dimensions that characterize the NPO sector (see 2–5 in Table 1):

Size (sz) refers to the growth of an NPO, whether in absolute terms, such as an increase in the number of organizations or in relative terms according to its contribution to the economy, such as the number of full-time employees. For 36 countries, Salamon et al. (2004) reported$ 1.3 trillion in expenditures and 2.7% of total workforce, highlighting the economic value of nonprofits for the first time.

Composition (comp) considers the different fields in which NPOs operate and range from health to education or culture. An examination of NPO composition reveals the fields where there is greater need or more interest in the development of the NPO sector.

Volunteering (vol-ing) The work of volunteers is a key resource for the NPO sector. Therefore, defining the work of volunteers will provide additional information regarding the scope of the roots of the NPO sector in a specific context. An analysis of NPOs that operated in 36 countries revealed that the value of volunteer work was $ 314 billion and represented 1.6% of the total volunteer workforce (Salamon et al. 2004).

Revenue structure (rev) NPO’s income sources are varied and range from government incentives to bequests. The distribution of income sources demonstrates the degree of financial strength of the NPO sector and its interdependencies with other sectors.

Anheier and Salamon argue that the discussion of the relevance and value of these definitional elements has been “one of the central features of the comparative NPO landscape” (2006, p.90). Therefore, our goal is to assess the extent that these aspects have inspired recent NPO comparative studies and how these aspects have been operationalized.

Four Original Impulses

Anheier and Salamon (2006) explain that increasing awareness regarding the socioeconomic and political impacts of NPOs and macro-social trends indicate the importance of NPOs and, consequently, inspire comparative research. Three primary macro-social trends that are labeled impulses include the following: new public management (NPM), social capital, and globalization (Table 2). NPM refers to the adaptation of new management styles by state institutions and, consequently, new forms of cooperation with nonprofits. Nevertheless, during the same time period, NPOs were subject to marketization and have adopted managerial practices (Eikenberry and Kluver 2004). Accordingly, we defined two new variables: NPM and management. The set of impulses presented in this section is marked for the analysis by using an “O,” denoting that they belong to the original impulses.

New Public Management (NPM-O)

The NPM perspective maintains that regardless of the private or public character of the entity, management strategies should be adopted to ensure that public services are efficiently delivered. Whether through welfare-state reform or structural adjustment programs, the concepts of NPM have spread in developed and developing countries and have inevitably affected the nonprofit sector (Anheier et al. 1999). An important principle of NPM is that NPOs play a key role as economic engines (Flynn 2002), and consequently, government efforts to shape NPOs through economic and legal incentives have affected the development of the NPO sector (Anheier and Seibel 1990b). Conversely, legal constraints may adversely affect the ability of NPOs to pursue their goals (Howell et al. 2007).

Management (MGT-O)

In addition to or as a response to reforms regarding governmental subsidy processes, NPOs have adopted numerous approaches and values of the private market. Some of these approaches, such as commercial revenue generation, contract competition, or social entrepreneurship, may negatively influence nonprofits’ role as value guardians or advocates (Eikenberry and Kluver 2004). Furthermore, the role of the board as a strategic decision-making body has increased (Cornforth 2014).

Social Capital (SC-O)

NPOs are perceived as important agents in the creation of the social fabric (Wollebaek and Selle 2007), and in a symbiotic manner, social capital enhances organizational effectiveness (Schneider 2009; von Schnurbein 2014). Social capital is a key element of democratic stability and economic growth because it is based on trust and shared norms. Trust and shared norms are significantly cultivated within the framework of NPOs, particularly in associations. Nevertheless, as Anheier and Salamon (2006) explain—and Anheier and Seibel before them (1990b)—NPOs can also be seen as elements of civic empowerment, that is, as organizations through which grass-roots associations and social movements express their views. Ultimately, social capital creation though NPOs is positive for stable, democratic societies.

Globalization (GL-O)

The capacity of NPOs to operate cross-nationally has increased in the past decade. Two of the most important elements that encourage NPOs to operate beyond their borders are the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution and the soaring demand for accountability of international institutions and organizations. However, Anheier and Salamon (2006) highlight the significant development of international laws as an important element, including trends in law convergence between countries and regions. These trends have increased the international status of NPOs and encouraged NPOs to mobilize for global agendas such as human rights, equality, humanitarian aid, and the environment.

Six Recent Impulses

Since the early accounts of James (1987), Anheier and Seibel (1990), and the revisions of Anheier and Salamon (2006) a decade ago, knowledge regarding the impulses of NPO research has advanced, and new impulses have been identified. In this section, we explain the primary advances in regard to the four impulses that are explained above and add two new trends: NPO–Business and economic capital (Table 3). These advances and trends have been identified in prominent studies (e.g., Anheier et al. 2012; Cornforth 2014; Salamon 2014) and in special issues and key discussions in journals reviewed in this study (e.g., Anheier 2014; Harris 2012; Lewis 2014). The set of impulses presented in this section is noted with an “R,” which indicates that these are new impulses.

NPM-R

In the last decade, NPM expanded its focus from efficiency and effectiveness (Gruening 2001) to incorporate value-based practices where the government acts as guarantor of public values (Crosby et al. 2014). This new focus has resulted in a demand for transparency and accountability; governments emphasize that mechanisms for regulation and oversight are essential aspects of NPO–government relationships (Cordery and Morgan 2013).

MGT-R

Relationships between NPOs and governments have become more structured; NPOs are more often direct providers of services; accordingly, government funding has transitioned from grants to contracts, partnerships, and other modes of cooperation (Cornforth 2014). As a result, NPOs are experiencing increased pressure to improve representativeness and accountability and issues such as professionalization and self-regulation have become more prominent. These transformations have expanded the responsibilities of boards that in the past were examined by their original impulses; these new responsibilities include the use of new tools for evaluating performance and incorporating complex forms of governance.

SC-R

Prior studies that adopted alternative perspectives on social capital or examined challenges to the development of social capital and civil society have become more visible (Anheier 2014). Moreover, research that considers views of social capital that differ from the notion that it creates a social fabric that stabilizes and develops democracy, that is, views of social capital as the basis of fragmentation and the reproduction of inequalities, is becoming more prominent (Kwon and Adler 2014). Recent studies question the ability to increase social capital through increasing the nonprofit sector (Hudock 1999; Potluka et al. 2017).

GL-R

Events such as the Arab Spring, austerity measures after the Great Recession, and increasing environmental concerns are blurring the distinctions between North and South (Lewis 2014) because concerns for democracy and social justice are shared and the resulting participation and mobilization are a global phenomenon (Anheier et al. 2012). New global agendas include climate change, austerity, social justice, and democratic quality.

NPO–Business (NPO-B)

The body of research regarding the relationship between businesses and NPOs is significantly less developed than the body of research regarding the relationships among NPOs, governments, and societies (e.g., NPM and SC). However, this topic is gaining attention (Harris 2012). The relevant research agenda explores two developing directions in the relationships between NPOs and businesses (Harris 2012). New studies analyze the modes of cooperation between businesses and NPOs to enhance NPOs’ capacities. Conversely, it analyzes the modes of cooperation between businesses and NPOs for the development of businesses’ corporate social responsibility.

Economic Capital (EC)

This impulse differs from a NPOs’ capacity to create social capital because it reflects their intention to transform their different types of capital into financial wealth. This impulse originated in austerity reforms that affected NPOs’ reliance on government support and compelled NPOs to become more entrepreneurial (Cornforth 2014). One important consequence of this entrepreneurship drive is that topics such as commercialization and social and NPO marketing are increasingly attracting scholars’ attention (Basil and Basil 2012). Furthermore, the traditional modes of philanthropy (grants, endowments, and bequests) align with new forms of capital such as venture philanthropy and social investment and the number of entities involved, and tools for NPO-development have increased significantly (Gautier and Pache, 2013; Salamon 2014).

Methods

Sample

This study’s sample includes 111 articles that were published in journals that appear on a list of international third-sector journalsFootnote 2 provided by the International Society for Third-Sector Research (ISTR) and a list of journals regarding philanthropic studiesFootnote 3 provided by the European Research Network on Philanthropy (ERNOP) (Table 4). Additionally, comparative research has been published in books, which usually compile country reports for a single comparative research project (i.e., Anheier and Daly 2007; Wiepking and Handy 2015). These books only offer limited additional knowledge to the summarizing type of study, such as this current study. Instead, we focused on academic journals because, despite their flaws (Atkinson 2001; Bohannon 2013), not only do they maintain high research standards that ensure good quality articles that advance scientific knowledge, but they also provide forums for significant discussions in most fields (Bornmann 2011).

To identify the articles, the main search terms were comparative study, comparative analysis, cross-national, cross-regional, cross-cultural, and international comparison. The selected articles compared at least two countries (Fig. 1). These searches identified 114 articles, and 111 were relevant for this research.

Figure 1 shows the total number of times a country is included in the studies. It also shows that the diversity of countries has progressively increased and a median of 55 countries has been studied annually—although with significant variance from article to article (SD = 72.72). Although North America (8.4%), Western Europe (23.4%), and Eastern Europe (40.7%) have been the focus of the studies since the start and the USA is discussed in 48 of the articles, the research began to include countries in the Middle East and Africa in 2005 and those in Asia and Latin America in 2008, which together constitute 25% of all such studies (Fig. 1).

Comparative research is likely to be influenced by contextual factors (Ragin and Amoroso 2011), and NPO comparative research does not appear to be an exceptionFootnote 4. Contextual factors are related to the material and technical conditions that affect researchers and impact the design and execution of a study. For example, because of the lack of data, new research topics or cases often apply a qualitative approach as a method of exploration and to establish the basis for future research. Most of the articles in the sample adopted a qualitative research design (63%) and sought to identify patterns and, to a certain extent, refine concepts, whereas most quantitative articles sought to identify correlations.

James (1987) and Anheier and Seibel (1990) highlighted the difficulties in collecting data for NPO comparative research. However, important efforts have been made during the last few decades to overcome these difficulties (Casey 2016). Among the qualitative studies, 26 refer to datasets and all quantitative articles used either primary or secondary datasets (Perez et al. 2016). Interviews and surveys are the source of primary data, and international and regional social and values surveys are a significant source of secondary data. An important step forward in quantitative research is the development of longitudinal research that, as the results shown in Table 5 suggest, is still lacking.

Cross-country comparative research may encourage collaboration among researchers both regionally and internationally. Table 5 indicates that only slightly more than one-quarter of the articles included authors from more than one country. However, this issue does not appear to stop researchers from looking for cases that are beyond their region, and more than half of the studies are cross-continent (Table 5).

To assess which studies were likely to be conducted by early comparative researchers (Anheier and Seibel 1990a; James 1987; Salamon et al. 1999, 2004), we examined the number of authors who also authored country chapters for the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (CNP). However, the descriptive results indicate that most authors did not participate in the CNP (Table 5). Finally, one important issue is the increasing interest in comparative research to attract more funding. This is a difficult issue to assess in this study’s sample (Table 5); however, one-third of the articles received funding from 42 institutions: 11 from the USA and 17 from other countries (Appendix).

Procedure

For our study, we develop an explorative approach that includes qualitative data analysis and comparative analysis. Systematic procedures were applied for an inductive analysis of the content of the 111 articles and to detect new perspectives on NPO comparative research.

The articles were classified according to the drivers and impulses that were identified in studies regarding NPO research and comparative research that was discussed in prior sections (Tables 1–3). The classification of the studies was executed independently by four researchers to ensure the reliability of the coding process. The categories were coded as binary to indicate the presence or absence of the category in the analysis of each article. Thirty-nine articles are represented by the original impulses variable, 59 represented by the new impulses variable, and 13 articles include both original and new impulses. The most examined definitional aspects were revenue structure, volunteering, and self-governing (respectively, 50, 29, and 27% of the articles), and the least examined were size and voluntary (respectively, 10 and 12% of the articles).

In the next step, we conducted a correspondence analysis to analyze the relationships between and within the drivers and impulses of NPO comparative research (Beh and Lombardo 2014). This method is best suited for the explorative nature of our survey because we use categorical, nonparametric data without distributional assumptions (Greenacre 2007). Correspondence analysis is a form of principal component analysis that is useful for interpreting nominal data because it transforms a large contingency table into a simple data matrix that can be represented visually (Beh and Lombardo 2014). The results allow for the analysis of the distance between different categories. For this study, the drivers and impulses were mapped as row and column values. The distances in-between can be interpreted as an overlap of content and understanding of different categories in the initially distinct concepts. Three correspondence analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package: first, between the definitional aspects variable and the original impulses variable; second, between the definitional aspects variable and the recent impulses variable; and finally, between the definitional aspects variable and both the original and recent impulses. The purpose of the first two analyses was to achieve an understanding regarding the relationship between the definitional aspects and the impulses. The purpose of the third analysis was to use comparisons to understand the interrelations among the three sets. Based on the findings, we finally detect new threads of research by combining impulses and drivers.

Results

Definitional Aspects and Original Impulses

Three dimensions were derived (Table 6); the first two dimensions account for 8.3% of the 9.8% total variance explained by this analysis. The first dimension is a viable solution because its average axis is greater than 0.20. The first dimension accounts for 60% of the total variance. The second dimension accounts for nearly one-quarter of the total variance and results in 84.5% of the total variance between the first two dimensions. Nevertheless, despite the Chi-square value, the low significance value (x2 = 17.983; df = 24; p > 0.05) rejects the expectation that definitional aspects and original impulses are closely arranged in configurations and aligned to explain the macro-social variation in NPOs.

Table 7 provides a more detailed description of the contributions of the individual categories of both variables to the variance. For the impulses, globalization is the primary contributor, followed by social capital; when combined, they account for 96.7% of the variance of the first dimension. For the second dimension, management is the main contributor, followed by social capital; when combined, they account for 98.5% of the variance. For the definitional aspects, there is no single major contributor for either dimension. Volunteering and distribution constraint are the main categories and account for the variance of both dimensions (44% and 55.7%, respectively). However, when these categories are combined with revenue structure, voluntary, and self-governing, the value increases to 86.8% of the inertia of the first dimension. Similarly, when the category composition is combined with volunteering and distribution constraint, they account for the inertia of the second dimension (67.4%). An assessment of fit demonstrated high values for all categories with the exception of NPM, which is below 50%, but sufficiently significant for the analysis.

The biplot in Fig. 2 is based on a row principal normalization. Therefore, the impulses as row values are closer to the center, but the distances between impulses and definitional aspects can be interpreted as Euclidean distances. Of the prior impulses, management is clearly distinct from the others. This distinction refers more strongly to definitional aspects, such as voluntary, private, and the distribution constraint, which are criteria of the operational definition of NPOs. More than the other impulses, the social capital impulse refers to composition and volunteering, which are definitional aspects that are related to specific nonprofit resources. Globalization is closer to revenue structure and size, which are dimensions of nonprofit growth. Because the impulse of NPM is located near the zero point of the coordinate system, it aligns with the average profiles and an interpretation is not possible. Altogether, the original impulses are related to some of the formulated definitional aspects of comparative research. However, the overall representation remains scattered.

Definitional Aspects and Recent Impulses

Five dimensions were derived in the analysis (Table 8); only the first two dimensions are viable solutions (greater than 0.20). The first two dimensions account for 24.3% of the 37.6% of the total variance explained by this analysis and account for 91% of the total variance. The results of this model are robust because the Chi-square value indicates that a relationship exists between definitional aspects and new impulses with a statistical significance value near the expected value compared with tests for the definitional aspects and original impulses (x2 = 54.488; df = 40; p > 0.05).

Table 9 illustrates the contribution of the individual categories of both variables to the variance. For the impulses, social capital is the single main contributor (81.6%) of the variance of the first dimension. For the second dimension, economic capital is the single main contributor (74.3%) of the variance. Both show the lowest values for the respective other dimension. These results facilitate an interpretation of the dimensions that span from social capital to economic capital. For the definitional aspects, volunteering is the single main category that contributes to the variance of the first dimension, at 64.3%. The second dimension’s contribution to the variance lies within four categories. Self-governing and distribution constraint combined contribute slightly more than one half of the variance (53.4%) and, when combined with size and revenue structure, account for 84.6% of the variance. To interpret the dimensions, one might infer that the first dimension spans between the voluntary contributions and the structural effects of organization and size. The second dimension spans from voluntary contributions to regulatory aspects, such as governance and the distribution constraint. Although the assessment of fit results in values less than 50% for NPO–Business, globalization, organized, and voluntary, these variables are statistically significant for the analysis.

Figure 3 illustrates a biplot that uses row principal normalization and depicts impulses as row values and definitional aspects as column values. With the exception of social capital, the impulses are all situated in one quadrant. Management, NPM, and globalization are particularly close together, accompanied by definitional aspects such as private, organized, and voluntary. The new impulses, NPO–Business, and economic capital, are closer to revenue structure, size, and distribution constraint than the other impulses. Although distant, social capital is in the same quadrant as the definitional aspects volunteering and composition, as is the case in the biplot of the original impulses. Compared to the analysis of the original impulses, the recent impulses demonstrate more commonality, particularly for the two additional impulses.

Definitional Aspects and Impulses

Eight dimensions with less than the significance value of the Chi-square (x2 = 80.229; df = 72; p > 0.05) were derived (Table 10); only the first two are viable solutions (greater than 0.20). The first two dimensions account for 19.3% of the 24.5% of the total variance that is explained by this analysis. The first dimension accounts for 60% of the total variance, and the second dimension accounts for 18.4% of the total variance.

Table 11 provides details of the contributions of the individual categories of both variables to the variance. For the impulses, no single main variable explains the variance of the first dimension. However, altogether, the categories social capital-o, social capital-r, and management-r explain two-thirds of the variance of the first dimension (66.66%). For the second dimension, economic capital is the main contributor and accounts for 64.8% of the variance. For the definitional aspects, the inertia of the dimensions is balanced across several categories. The first dimension, volunteering, accounts for less than 50% of the variance. However, when combined with revenue structure, self-governing, and voluntary, the value increases to 82.9%. The variance of the second dimension is accounted for by self-governing, revenue structure, distribution constraint, and size, which, when combined, account for 82.1% of the dimension’s inertia. The assessment of fit indicates high values for all categories with the exception of management-o.

Finally, we present a biplot of all impulses and all definitional aspects, using principal normalization to analyze and compare all variables (Fig. 4). The advantage of principal normalization is that the biplot provides symmetrical results with Euclidean distances between impulses and definitional aspects (Greenacre 2007). We separate three clusters of analysis. NPO–Business and economic capital are distinct from the other impulses, and size and distribution constraint are the closest definitional aspects to these two new impulses. The two impulses on social capital are in one cluster with the definitional aspects composition, voluntary, and volunteering. The original and recent impulses for management, NPM, and globalization are all in the same cluster with revenue structure, private, organized, and self-governed.

Discussion

The results of the correspondence analyses offer insights into the past orientation of nonprofit comparative research and may serve as a basis for developing perspectives on future comparative research in this field. Before we discuss our results, we must emphasize some limitations regarding the data and methods used in the study. The first limitation is regarding the literature we used for data collection. We are aware that more comparative research is available and that many results of comparative studies are published in media other than academic journals. However, given our aim of exploring advances in research, we find it appropriate to limit the data to leading peer-reviewed journals in the field. The second limitation concerns the method and the quality of the results. Correspondence analysis is a method that is used for data reduction and simplification, and therefore, the results do not allow for generalization. Nevertheless, the explorative nature of the study allows us to offer new insights and encourage discussions regarding future comparative research.

When comparing the separate analyses of the original and recent impulses, three aspects are of interest. In contrast to the recent impulses, the disparity among the original impulses and definitional aspects is remarkable. Most of the definitional aspects are relevant for only one impulse, for example, volunteering for social capital, the distribution constraint for management, and revenue structure for globalization. Recent impulses are much more concentrated (with the exception of volunteering). To a degree, the definitional aspects group around the impulses, which are almost all situated in one quadrant. It could be argued that the recent impulses lead to a more integrated use of comparative research methods and simultaneously capture several research streams.

The second aspect of interest is the consistency of social capital in relation to composition and volunteering for both analyses. In general, the two definitional aspects tend to be distant, but social capital remains the closest impulse. Putnam (1995) used membership in NPOs as an indicator of social capital because membership offers a natural network for bridging social capital (Wollebaek and Selle 2007). From this perspective, volunteering is an even stronger indicator of social capital because it requires high commitment and social interaction. Composition, as a driver for nonprofit comparative research, differentiates fields of activity among NPOs. The quality and intensity of social capital may vary across NPOs in different fields; for example, professional associations differ from social service agencies. Therefore, comparative research regarding volunteering and composition may lead to new insights into both the development and use of social capital in NPOs (von Schnurbein 2014).

Nevertheless, this significant association between social capital and volunteering does not sufficiently capture the advances in the study of social capital. Social capital is increasingly reconsidering the assumption that NPOs contribute to the strengthening of the social fabric. Therefore, it might be expected that recent comparative research regarding social capital would, to a certain extent, not align with the original definitional aspects.

With respect to volunteering, we found that comparative research should better align with new trends. As Wilson (2012) points out, the study of volunteering has moved from how volunteer inputs shape NPOs to how the dimensions of volunteering shape NPOs. The dimensions of volunteering include antecedents (i.e., motivations), experience (i.e., satisfaction and commitment), and consequences (i.e., health benefits and job prospects) (Wilson 2012; Studer and von Schnurbein 2013). However, although the most examined dimension is regarding the antecedents of volunteering, there is a continued lack of research regarding the experience of volunteering (Wilson 2012). Our study confirms that comparative research primarily concentrates on volunteering inputs and volunteering antecedents.

Finally, a third aspect should be more comprehensively analyzed. In the analysis of the original impulses, management is the closest impulse to distribution constraint. This aligns with the high valuation of the non-distribution constraint in early nonprofit studies (Salamon and Sokolowski 2014). In the analysis of the recent impulses, distribution and size are the most relevant definitional aspects for economic capital and NPO–Business. These new impulses highlight the blurring of boundaries between the market and the third sector and lead to new hybrid forms of organizations (Eikenberry 2009). In these types of organizations, the non-distribution constraint is less important and future research should determine new definitional aspects for categorization and differentiation.

From a joint analysis of the original and recent impulses, we formulate three clusters for the future orientation of nonprofit comparative research, as demonstrated in the distribution of the values in the biplot (Fig. 3). Because of the nature of the explorative approach that is used in our study, these orientations are merely tendencies, rather than clear directions. The first cluster that includes the impulses NPO–Business and economic capital and the definitional aspects of size and distribution constraint, highlights the blurred boundaries and the marketization of the third sector. Future comparative research regarding these issues should address issues regarding investment, growth, and market development. Where can NPOs invest, and what will make NPOs more attractive to investors? What are the different paths for growth, and how does growth influence the mission orientation of NPOs? What are the new markets for NPOs, and how do the traditional arenas of NPOs develop into markets?

The second cluster includes a combination of original and recent impulses (management, NPM, and globalization) and the definitional aspects of revenue structure, private, organized, and self-governed. Therefore, the definitional aspects are closely related to aspects of the operational definition of NPOs and incentivization. In the past, comparative research addressed differentiations and commonalities among the type and characteristics of NPOs; recent perspectives focus more on social impact, participation, and international developments. How is social impact measured in different social communities? How does participation develop on a global scale and what are the new forms of participation (perhaps outside traditional nonprofit structures)? What are the opportunities or threats of globalization for the third sector? How do global challenges such as terrorism, austerity, and climate change constrain/foster the transnational strategies of NPOs?

The third cluster combines social capital with the definitional aspects of volunteering, voluntary, and composition. As stated above, social capital primarily refers to norms and networks that build trust and social connections. This cluster leads to new research perspectives on civil society and social cohesion. How can NPOs develop resources in addition to money for mission, and what might be the new forms of civil society? How does the third sector strengthen/undermine social cohesion? What resources do NPOs use, and in which areas do they promote social cohesion? What factors affect or encourage civil-society development in challenged states (states in crisis and authoritarian regimes)?

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to identify the main drivers that shape the NPO comparative research agenda. The results suggest that the drivers shaped the NPO comparative research agenda in an irregular manner and generated three main clusters. Table 12 summarizes these clusters. A core cluster that includes the operational definition and incentivization of NPOs incorporates four definitional aspects (revenue structure, private, organized, and self-governed) and three impulses (new public management, management, and globalization); a second cluster includes social capital in relation to the three definitional aspects of composition, volunteering, and voluntary. A third cluster combines recent impulses that address the increasing commodification of NPOs (NPO–Businesses and economic capital) and is related to two definitional aspects (size and distribution constraint).

Because our findings are based on existing literature, the suggested perspectives can be understood as advances in existing studies rather than as innovations. This analysis is limited because correspondence analysis is an exploratory technique that is devoted to the evaluation of nominal data and focuses on data reduction. Therefore, we can describe the relationship between impulses and definitional aspects, but we are unable to make other conclusions as a result of this analysis.

Two decades have passed since the seminal work on NPO comparative research, and as this article demonstrates, this is still inspiring a good deal of research. As the findings show, researchers continue to be concerned with essential questions regarding NPOs’ relations with the state and management and with their roles in different contexts. Issues related to NPOs’ contribution to the social fabric continue to attract researchers’ attention; nevertheless, this issue is more developed than the essential questions previously mentioned. Similarly, there is new interest in studying the commodification of NPOs in isolation from the primary issues related to the NPO phenomenon.

One of the primary aims of comparative research is the theory building. Although comparative research is widely used to study NPOs, the literature examined in this study suggests that theory building has occurred in a fragmented manner. The advancement of theories for the identified clusters is certainly important, but the advancement of the theoretical understanding of the NPO phenomenon is also necessary. By identifying three areas of research, we hope to stimulate new research that seeks to achieve cross-fertilization and provide new information regarding the interrelationships. Frequently, cross-fertilization has been a source of innovation in science, and because centrifugal forces grow with an increasing number of impulses, it becomes increasingly important to identify the connecting threads.

Change history

02 July 2018

The PDF version of this article was reformatted to a larger trim size.

Notes

Salamon and Sokolowski’s recent study has renewed the debate on the definitional aspects of NPOs, the impact of which will be examined in future years (i.e., Defourny et al. 2016).

The structural characteristics of the analyzed articles are explained elsewhere.

References

Anheier, Helmut K. (2014). Civil society research: Ten years on. Journal of Civil Society, 10(4), 335–339.

Anheier, H. K., & Daly, S. (2007). Politics of foundations : A comparative analysis. Florence: Routledge.

Anheier, H. K., Kaldor, M., & Glasius, M. (2012). The global civil society yearbook: Lessons and insights 2001–2011. In S. Selchow, M. Kaldor, & H. Moore (Eds.), Global civil society 2012. Ten years of critical reflection. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anheier, H. K., & Salamon, L. M. (2006). The nonprofit sector in comparative perspective. In W. W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (pp. 89–114). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Anheier, H. K., & Seibel, W. (1990a). The third sector in comparative perspective: Four propositions. In H. K. Anheier & W. Seibel (Eds.), The third sector: Comparative studies of nonprofit organizations. New York: de Gruyter.

Anheier, H. K., & Seibel, W. (1990b). The third sector: Comparative studies of nonprofit organizations. New York: de Gruyter.

Atkinson, M. (2001). Peer review’ culture. Science and Engineering Ethics, 7(2), 193–204.

Basil, D., & Basil, M. (2012). Introduction to special issue. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17(2), 293–294.

Bauer, R. (1990). Nonprofit organizations in international perspective. In H. K. Anheier & W. Seibel (Eds.), Third sector. Comparative studies in nonprofit research (pp. 271–275). New York: De Gruyter.

Beh, E., & Lombardo, R. (2014). Correspondence analysis: Theory, practice and new strategies. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Bohannon, J. (2013). Who’s afraid of peer review? Science, 342(October), 60–65.

Bornmann, L. (2011). Scientific peer review. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 45, 197–245.

Casey, J. (2016). Comparing nonprofit sectors around the world. What do we know and how do we know it? Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership, 6(3), 187–223.

Cordery, C. J., & Morgan, G. G. (2013). Special issue on charity accounting reporting and regulation. Voluntas, 24(3), 757–759.

Cornforth, C. (2014). Nonprofit governance research: The need for innovative perspectives and approaches. In C. Cornforth & W. Brown (Eds.), Nonprofit governance: Innovative perspectives and approaches (pp. 1–14). Abingdon: Routledge.

Crosby, B. C., Bloomberg, L., & Bryson, J. (2014). Public value governance: moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 445–456.

Defourny, J., Grønbjer, K., Mejis, L., Nyssens, M., & Yamauchi, N. (2016). Voluntas symposium: comments on Salamon and Sokolowski’s re-conceptualization of the third sector. Voluntas, 27(4), 1546–1561.

Eikenberry, A. (2009). Refusing the market—a democratic discourse for voluntary and nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(4), 582–596.

Eikenberry, A. M., & Kluver, J. D. (2004). The marketization of the nonprofit sector: Civil society at risk? Public Administration Review, 64(2), 132–140.

Epperly, B., & Lee, T. (2015). Corruption and NGO sustainability: A panel study of post-communist states. Voluntas, 26(1), 171–197.

Flynn, N. (2002). Explaining the new public management. The importance of context. In K. McLaughlin, S. P. Osborne, & E. Ferlie (Eds.), New public management: Current trends and future prospects (pp. 57–76). Routledge: London.

Gautier, A., & Pache, A. C. (2013). Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 118, 1–27.

Greenacre, M. (2007). Correspondence analysis in practice (2nd ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

Gruening, G. (2001). Origin and theoretical basis of new public management. International Public Management Journal, 4, 1–25.

Harris, M. (2012). Nonprofits and business: Towards a sub-field of nonprofit studies. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(5), 892–902.

Howell, J., Ishkanian, A., Obadare, E., Seckinelgin, H., & Glasius M. (2007). The backlash against civil society in the wake of the long war on terror. Civil society working paper 26, London: London School of Economics.

Hudock, A. C. (1999). NGOs and civil society. Democracy by proxy?. Cambridge: Wiley.

James, E. (1987). The nonprofit sector in comparative perspective. In W. W. Powell (Ed.), The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (pp. 397–415). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kittel, B. (2006). A crazy methodology? On the limits of macro-quantitative social science research. International Sociology, 21(5), 647–677.

Kwon, S.-W., & Adler, P. S. (2014). Social capital: Maturation of a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 412–422.

Lewis, D. (2014). Heading south: Time to abandon the ‘parallel worlds’ of international non-governmental organization (NGO) and domestic third sector scholarship? Voluntas, 25, 1132–1150.

Mills, M., & De Bruijn, J. (2006). Comparative research. persistent problems and promising solutions. International Sociology, 21(5), 619–631.

Perez, M., von Schnurbein, G., & Gehringer, T. (2016). Comparative research of non-profit organisations: A preliminary assessment. CEPS Working Paper Series, No. 9. Basel: CEPS.

Potluka, O., Spacek, M., & von Schnurbein, G. (2017). Impact of the EU structural funds on financial capacities of non-profit organizations. Voluntas. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9845-1.

Powell, W. W. (1987). The nonprofit sector: A research handbook. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: Americas’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65–78.

Ragin, C. (1987). The comparative method. Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ragin, C. (2006). How to lure analytic social science out of the doldrums: Some lessons from comparative research. International Sociology, 21(5), 633–646.

Ragin, C., & Amoroso, L. M. (2011). Constructing social research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ragin, C., & Rubinson, C. (2009). The distinctiveness of comparative research. In T. Landman & N. Robinson (Eds.), The sage handbook of comparative politics (pp. 13–34). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Rikmann, E., & Keedus, L. (2013). Civic sectors in transformation and beyond: Preliminaries for a comparison of six Central and Eastern European Societies. Voluntas, 4, 149–166.

Salamon, L. M. (Ed.). (2014). New frontiers of philanthropy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salamon, L. M., Anheier, H. K., & associates. (1999). Civil society in comparative perspective. In L. M. Salamon, H. K. Anheier, R. List, S. Toepler, S. W. Sokolowski, & Associates Global Civil Society (Eds.), Dimensions of the nonprofit sector (pp. 3–39). Bloomfield: Kumarian Press.

Salamon, L. M., Anheier, H. K., List, R., Sokolowski, S. W., Toepler, S., & Associates. (2004). Global civil society: Dimensions of the nonprofit sector. Baltimore: John Hopkins Center for Civil Society.

Salamon, L. M., & Sokolowski, S. W. (2014). The third sector in Europe: Towards a consensus conceptualization. TSI Working Paper Series, no. 02. http://thirdsectorimpact.eu/documentation/tsi-working-paper-no-2-third-sector-europe-towards-consensus-conceptualization/.

Salamon, L. M., & Sokolowski, S. W. (2016). Beyond non-profits: Re-conceptualizing the third sector. Voluntas, 27(4), 1515–1545.

Schneider, J. A. (2009). Organizational social capital and nonprofits. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(4), 643–662.

Studer, S., & von Schnurbein, G. (2013). Organizational factors affecting volunteers: A literature review on volunteer coordination. Voluntas, 24(2), 403–440.

von Schnurbein, G. (2014). Managing social capital through value configurations. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 24(3), 357–376.

Wiepking, P., & Handy, F. (Eds.). (2015). The Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(2), 176–212.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2007). Origins of social capital: Socialization and institutionalization approaches compared. Journal of Civil Society, 3(1), 1–24.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jeffrey Brudney for his useful comments. Early versions of this manuscript benefited from the comments of the ERNOP 7th International Conference, 2015, and the 12th ISTR World Conference, 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

von Schnurbein, G., Perez, M. & Gehringer, T. Nonprofit Comparative Research: Recent Agendas and Future Trends. Voluntas 29, 437–453 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9877-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9877-6