Abstract

We study how donors decide about which charity to give to. To this end, we construct a theoretical model that clarifies the conditions under which the stand-alone benefit from giving, the charity price (i.e. the fundraising expenditure and overhead costs claimed by the charity providing services), and the information cost (i.e. the cost of information acquisition) inform giving decisions. We define the price of giving as the sum total of charity price and information cost. The model shows that giving decisions might be affected by a price–information trade-off—a condition where donors care about the charity price because they want their donations to maximise charitable output, but dislike searching for the charity price because it is costly. The literature is then reviewed to test the explanatory power of the theoretical model. The review provides evidence in favour of a price–information trade-off.

Résumé

Nous étudions comment les donateurs déterminent à quelles associations caritatives ils vont donner. À cet effet, nous élaborons un modèle théorique qui précise les conditions dans lesquelles l’avantage à part entière à faire un don, le prix de l’organisme de bienfaisance (les dépenses de collecte de fonds et les frais généraux réclamés par l’organisme offrant les services, par exemple) et le coût des informations (le coût d’acquisition des informations, par exemple) informent les décisions de dons. Nous définissons le prix des dons comme la somme totale du coût de l’organisme de bienfaisance et le coût des informations. Le modèle montre que les décisions de dons peuvent être affectées par un compromis sur les informations tarifaires – une condition où les donateurs se préoccupent du prix de l’organisme de bienfaisance parce qu’ils veulent que leurs dons augmentent autant que possible le résultat des organismes de bienfaisance, mais n’aiment pas rechercher le prix de cet organisme, car il est coûteux. Les publications sont ensuite examinées pour tester le pouvoir explicatif du modèle théorique. Cet examen fournit des preuves en faveur d’un compromis sur les informations tarifaires.

Zusammenfassung

Wir untersuchen, wie Spender entscheiden, an welche gemeinnützige Einrichtung sie spenden. Dazu erstellen wir ein theoretisches Modell, das die Bedingungen erläutert, unter denen der separate Vorteil aufgrund von Spenden, der karitative Preis (d. h. die von der gemeinnützigen Organisation, welche die Dienstleistungen bereitstellt, angegebenen Aufwendungen im Zusammenhang mit der Mittelbeschaffung und fixen Kosten) sowie die Informationskosten (d. h. die Kosten im Zusammenhang mit der Informationsgewinnung) Spendenentscheidungen beeinflussen. Wir definieren den Spendenpreis als die Gesamtsumme des karitativen Preises und der Informationskosten. Das Modell zeigt, dass Spendenentscheidungen von einem Preis-Informationskonflikt beeinflusst werden können - ein Umstand, bei dem der karitative Preis für Spender von Bedeutung ist, weil sie sich von ihren Spenden das maximale gemeinnützige Resultat wünschen, sie jedoch nicht den karitativen Preis nachforschen möchten, da dies mit Kosten verbunden ist. Anschließend wird die Literatur geprüft, um die Aussagekraft des theoretischen Modells zu testen. Die Literaturprüfung liefert Anhaltspunkte für einen Preis-Informationskonflikt.

Resumen

Estudiamos cómo los donantes deciden a qué organización benéfica dar. Con este fin, construimos un modelo teórico que clarifica las condiciones en las que el beneficio independiente de dar, el precio de la organización benéfica (es decir, el gasto de recaudación de fondos y los costes generales indicados por la organización benéfica que proporciona los servicios), y el coste de información (es decir, el coste de adquisición de información) informan la decisión de dar. Definimos el precio de dar como la suma total del precio de la organización benéfica y el coste de información. El modelo muestra que la decisión de dar puede verse afectada por un compromiso entre precio-información - una condición en la que los donantes se preocupan por el precio de la organización benéfica porque desean que sus donativos maximicen los resultados benéficos, pero les disgusta buscar el precio de la organización benéfica porque es costoso. Después, se revisa el material publicado para probar el poder explicativo del modelo teórico. La revisión proporciona evidencias a favor de un compromiso entre precio-información.

我们研究了捐赠人如何决定要捐赠的慈善组织。对此,我们构建了一个理论模型,以了解捐赠的单独好处、慈善价格(即提供服务的慈善组织的筹款支出和日常开支成本)和通知捐赠决定的信息成本(即信息采集)。我们将捐赠价格定义为慈善价格和信息成本的总和。该模型表明,捐赠决定可能受价格信息权衡的影响 – 其中捐赠人关心慈善价格,因为他们希望捐赠最大化慈善输出;但是,不太喜欢搜索慈善价格,因为这过于昂贵。然后,本研究查阅了各种文献以测试理论模型的解释力,从而提供有利于价格信息权衡的证据。

ندرس كيف يقرر المانحين لأي مؤسسة خيرية يعطون. تحقيقا˝ لهذه الغاية، أقمنا نموذج نظري يوضح الظروف التي الفائدة القائمة بذاتها من العطاء، سعر العمل الخيري (أي نفقات جمع الأموال والتكاليف العامة التي تطالب بها الجمعية الخيرية التي تقدم خدمات)، وتكلفة المعلومات ،(مثل٬ تكلفة الحصول على المعلومات) إبلاغ إعطاء القرارات. نحدد سعرالعطاء مثل مجموع سعرالعمل الخيري وتكلفة المعلومات. النموذج يظهر إعطاء القرارات يمكن أن يتأثر بالمفاضلة بين سعر المعلومات – الحالة التي فيها يهتم المانحين بسعر العمل الخيري لأنهم يريدون تبرعاتهم تزيد الإنتاج الخيري إلى حد كبير، لكن يكرهون البحث عن سعر العمل الخيري لأنه مكلف. ثم يتم مراجعة الأدبيات لاختبار القوة التفسيرية للنموذج النظري. تقدم المراجعة الأدلة في صالح المفاضلة بين السعر- المعلومات.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The emergence of entities the objective of which is to help donors make “smart” giving decisions suggests that donors are demanding more information on the efficiency and effectiveness of not-for-profits (e.g. see Saxton et al. 2011; Bekkers 2003, 2010); however, it is occasionally argued that donors do not use these tools to guide their giving decisions (e.g. Arumi et al. 2005; Sargeant 1999; Sargeant and Ford 2006; Sargeant and Jay 2010). If this were generally true, then the various means of charity quality assurance, such as charity watchdogs and disclosure-related regulation, would be wasted. We thus ask: How do donors decide about which charity to give to, and do donors use the charity price to guide their giving decisions?

To answer these questions, we construct a theoretical model that specifies the conditions under which the charity price influences donors’ giving decisions. A “utility function” is a way of capturing the (psychological) benefits the donor receives from giving. We assume the donor’s utility function contains three components: the stand-alone benefit from giving, the charity price (i.e. fundraising expenditure and overhead costs claimed by the charity providing servicesFootnote 1), and the information cost (i.e. the price the donor has to pay for information about the charity price), which may consist of effort cost as well as out-of-pocket expenses. The charity price describes the cost of purchasing charitable output. It increases when the charity uses more donations on fundraising and administration expenditure, as it means the donation is less able to purchase charitable output. We define the price of giving as the sum total of charity price and information cost.

The main insight from the model is that the typical donor faces a price–information trade-off, which occurs when she is not well informed about the charity price but wants to use it to guide her giving decisions. Since her search for information on the charity price is costly in terms of time, effort, and money, she might be willing to forego giving to the charity with the lowest charity price in order to decrease the price of giving.

The model contains three implications. First, the donor who faces the price–information trade-off adopts strategies to minimise the price of giving. Second, a charity that uses donations on fundraising and advertising expenses might receive more donations if they help decrease the information cost. Third, to the extent that the provision of information has a strong public-good component to it, our analysis suggests that publicly funding watchdog agencies or seals of approval might be beneficial.

The hypothesis that donors experience a price–information trade-off is tested by means of a literature review. Specifically, we verify whether donors care about the charity price and attempt to minimise the amount of cost associated with searching for it. The evidence seems to support the conjecture that this trade-off informs donors’ giving decisions.

In “The Theoretical Model” section we provide the theoretical model, and in “The Literature Review” section we provide our literature review. Concluding remarks follow in the “Concluding Remarks” section.

The Theoretical Model

The Basic Set-Up

To formalise how the price of giving informs donors’ giving, we use the concept of “utility” to explain what motivates an individual to behave a certain way. We assume the donor makes decisions that maximise her benefits net of charity price and information cost (i.e. “maximises her utility”). Her utility function consists of three components: the stand-alone benefit from giving (Component 1); the charity price (Component 2); and the information cost (Component 3). The interaction of these components determines the level of utility she receives from giving.

Component 1: Stand-Alone Benefit from Giving

Donors give to charitable causes for various reasons. She might give because she values the output provided by the charity (Vesterlund 2006), to feel the “joy of giving” (Andreoni 1990), or to fulfil a duty she believes the privileged are bound by (Sen 1977). For our present purpose, we simply assume the donor gives because she receives some form of benefit from doing so.

The donor’s willingness to give corresponds positively to the level of benefit she receives from doing so. If the donor prefers dogs to cats, for example, she most likely receives greater benefit from giving to a dog charity than to a cat charity provided all other factors, such as the information cost and the charity price, are equal. The term “taste” is used to describe the donor’s willingness to give to different charitable causes.

Component 2: Charity Price

Modifying Weisbrod and Dominguez (1986), the charity price reflects the proportion of donations the charity spends on producing charitable output. Namely, the charity spends a portion of every dollar worth of donations on administration and fundraising expenses. The charity price increases when the charity uses a larger portion of its donations on these expenses, as it means a smaller portion of donations is used to purchase charitable output, and vice versa. The price-sensitive donor dislikes giving to charities with a high charity price.Footnote 2

Component 3: Information Cost

The typical donor is not well informed about charities. If the donor cares about the charity price, she will exert effort to learn about the charity’s performance, which is the information cost. Her search to verify the price of giving, however, is costly in terms of effort, time, and money. She thus becomes unhappier as the cost of information acquisition increases.

The donor’s objective is to give to the charity that maximises her utility (Eq. 1). Her net utility increases when her stand-alone benefit from giving increases, and decreases when the price of giving and the cost of acquiring information increases.

Information is Perfect (Information Cost = 0)

We first assume that information is perfect—donors know the charity price for all charities. Component 3, the information cost, is thus absent from the present discussion, and charity price is thus identical to the price of giving. When information is perfect, charity price informs all giving irrespective of the type of taste the donor has. To illustrate, consider the donor with the following tastes:

Donor with Uniform Tastes

The donor with uniform tastes likes each charitable cause equally, and so receives the same amount of benefit from giving to each cause. The donor’s net utility from giving equals her stand-alone benefit from giving to a cause minus the disutility felt from the price of giving which equals in this case charity price. Since benefit is equal for all causes, she maximises her net utility by giving to the charity with the lowest charity price, as she experiences the least disutility from giving to it. The charity price informs the giving decisions of the donor with uniform tastes.

Donor with Peak-Shaped Tastes

A donor with peak-shaped tastes prefers one cause above all other causes, and so receives greater benefit from giving to her favourite cause rather than the alternatives. Suppose the donor only wishes to give to dog charities. She has the same stand-alone benefit from giving to any charity that supports stray dogs. Since, based on stand-alone benefit alone, she cannot distinguish which charity to give to but possesses information on charity price, she uses price to discriminate among them. She maximises her utility by giving to the charity with the lowest price, for it generates the least disutility.

Hypothesis 1

When a cause is supported by many charities and information is perfect, the charity price, which is also the price of giving when information is perfect, informs all giving, regardless of the taste of the donor.

Since donors give to the charity with the lowest price, charities are forced to produce output at the lowest price, lest they lose donations to charities that provide the same goods at a lower price. The charity market thus converges to a perfectly competitive market, as charities compete for donations through price.

Information is Imperfect (Information Price ≠ 0)

The charity market is imperfect due to information asymmetries—donors typically do not know the charity price and charities have better information about their price than donors (Ortmann and Schlesinger 2003). We thus assume that information is imperfect to move the model closer to reality. To allay information asymmetry, the price-sensitive donor might exert effort to search for charities’ key financial and performance-related indicators, incurring an information cost in terms of time, effort, and money. She hence might experience disutility from searching. This price–information trade-off is illustrated in the following scenarios.Footnote 3

Scenario 1: The Donor Strongly Dislikes Searching for Charities’ Charity Price

The donor who has high information cost does not search for the charity price. If her stand-alone benefit from giving to her favourite cause is greater than the expected disutility from giving to a charity, she gives to any charity that supports her favourite cause(s). If her stand-alone benefit from giving to her favourite cause is smaller than the expected disutility from giving to a charity, then she does not give.

Scenario 2: The Donor Strongly Dislikes Giving to a Charity with a High Price

For the donor who experiences large disutility from giving to a charity with a high charity price, if her stand-alone benefit from giving to her preferred cause is large enough, she will look for the charity price regardless of the information cost. If her stand-alone benefit from giving to her preferred cause is low, she will not search for the charity price and not give.

Scenario 3: The Donor Finds Ways to Decrease the Information Cost

Depending on the donor’s aversion to effort, she might exert effort to find more information on charity price. For the donor who is willing to exert effort because she values the charity price, ratings by charity watchdogs and/or certification agencies’ seals of approvals would act as an appropriate mechanism to help guide her giving decision, while decreasing the information cost associated with acquiring information on them.

The scenarios illustrate three implications of the price–information trade-off:

-

1.

A donor might appear to let her “taste” cause her to give indiscriminately to charities; however, her giving might be due to her aversion to information cost. For example, suppose the donor’s favourite cause is dogs, and she is only aware of one charity that supports dogs. If the donor faces the price–information trade-off and believes (possibly falsely) the charity has a low price, she might still give to it.

-

2.

Fundraising expenses might increase donations if they decrease the donor’s information cost. Fundraising thus has countervailing effects on giving. It increases the charity price, which decreases the donor’s willingness to give, but it also decreases the information cost by increasing the charity’s name recognition, which may lead to greater donations.

-

3.

The donor who faces the price–information trade-off would welcome tools that help minimise the information cost, such as ratings by charity watchdogs and/or certification agencies’ seals of approvals.

Hypothesis 2

When many charities support a single cause and information is imperfect

-

A.

A donor that faces the price–information trade-off might behave like a donor who does not care about the charity price;

-

B.

Raising the profile of the charity through fundraising expenditure can increase donations; and

-

C.

Donors who face the price–information trade-off would welcome shortcuts to minimise the amount of costly effort associated with searching for charities’ price of giving (charities’ price).

Hypothesis 2 raises an important policy issue concerning the possibility that fundraising and advertising is a social waste and that information acquisition could be better achieved through charity watchdogs and/or seals of approvals. These bodies would be less self-serving and, due to the public-good aspect of information, more cost-effective; they might also increase the quality of charities on average (e.g. Svitkova 2013 and literature review therein).

The Literature Review

We review studies that address components 2 (i.e. the charity price) and 3 (i.e. information cost) of the utility function to assess whether donors use charity price to inform their giving decisions and/or whether they try to reduce the information cost.Footnote 4

Do Donors Care About the Charity Price?

In the model, if the donor cares about the charity price and wants her dollar contribution to maximise charitable output, charities with a lower price are rewarded with higher donations. Using a desk-based search of the literature, survey and empirical evidence were reviewed to verify whether this assumption reflects reality.

Survey Evidence

Table 1 contains a summary of the survey findings. The evidence suggest that donors are hetergeneous—some value charity price and use it to guide their giving, whereas others do not. Most donors from Arumi et al. (2005), for example, reported they did not research their beneficiary charity before or after they gave nor were they interested in the financial details of charities. However, they displayed price sensitivity, as they diverted their donations from United Way and Red Cross to other charities once news of the misuse of donations emerged. In contrast, donors from Barclays Wealth (2010) claimed they often used efficiency metrics to guide which charity they gave to (but see Hope Consulting 2010).

Moreover, non-donors do not give, and donors do not give more, if they believe their donations will not be used efficiently (Madden 2006; Lasby 2004). Specifically, Bagwell et al. (2013) calculated that donors would donate an additional £663 million if charities could better explain how donations were used and provided evidence of impact.

Observation 1 Based on the survey evidence

-

(1)

Donors claimed they use charity price to inform the charity they give to; however, the extent to which donors use price to guide their giving decision varies.

-

(2)

Some donors claim to search for metrics to guide their giving, whereas others do not. Donors nonetheless tend to stop giving if a charity is reported as having misused donations.

The survey methodology has important limitations. Surveys that focus on a subgroup might provide a biased sample of the population. Surveys can be subjective, as one person’s perception of efficiency or effectiveness might be different from another’s (Borgloh et al. 2013, 2010). As demonstrated in Buchheit and Parson’s (2006) experiment, respondents’ self-reported behaviour may not match actual behaviour. In their study, all subjects were given a charity fundraising request, while roughly half were given additional service efforts and accomplishment (SEA) information.Footnote 5 Based on the survey taken by the subjects, those who received SEA information were more likely to make a future donation to the charity than those who received the basic fundraising request. However, when given the choice to give $2 to the charity or keep a pen, subjects who received the SEA information were more likely to keep the pen than subjects with the basic fundraising request.

Empirical Evidence

Simplifying Weisbrod and Dominguez’s (1986) price-of-giving model, the donor purchases chariable output in dollar amounts.Footnote 6 For every dollar contributed to the charity’s output, a portion is spent on other expenses, such as fundraising and administration. When the portion spent on other expenses increase, the donor’s dollar contribution buys less charitable output. The charity price (PRICE) thus increases as it costs more to purchase a dollar’s worth of charitable output. The model is formalised in Eq. (2):

where f and a represent fundraising and administrative expenses, respectively.

Table 2 summarises the results from studies that test the relationship between PRICE and donations. Column “PRICE variable” contains accounting ratios that are based on Eq. (2). Column “PRICE” contains the qualitative effect of the PRICE variable on donations. Symbol “+” denotes the PRICE variable and donations are positively correlated—donors give more to charities that have a higher price of giving. Symbol “−” denotes the PRICE variable and donations are negatively correlated—donors give less to charities that have a higher price of giving, or more precisely a higher charity price since none of the studies controls for the information costs. “0” denotes the PRICE variable having a statistically insignificant effect on donations. If donors want their dollar contributions to maximise the charity’s output, “−” should be observed across the PRICE column. The “Fundraising” column is addressed later.

Observation 2, however, is open to interpretation. Specifically, the negative effect of PRICE on donations suggests that donors are price sensitive, but the positive effect of fundraising on donations suggests that giving increases when charities increase expenditure on fundraising, such as through soliciting donors more frequently or with better quality. We elaborate on this issue in “Do Higher Fundraising Expenses Correspond to More Giving?” section of the paper.

Moreover, these results depend on the econometric tools that are used, the data analysed, and the regulatory framework imposed at the time of analysis (e.g. see Krishnan et al. 2006; Tinkelman 1999; Tinkelman and Mankaney 2007; Yetman 2009). Tinkelman and Mankaney (2007), for example, replicated the regressions in Posnett and Sandler (1989), Greenlee and Brown (1999), and Frumkin and Kim (2001) with different data sets to verify the effect of the administration ratio on donations. Consistent with Greenlee and Brown (1999) and Frumkin and Kim (2001), a higher administrative ratio corresponded to greater donations. However, when the same regression was conducted with “relevant and reliable” data,Footnote 7 the effect became negative. When they replicated Posnett and Sandler’s (1989) study, a higher administrative ratio corresponded to greater donations, regardless of the data’s quality. The authors posit that this result was driven by the less “relevant” nature of the dataset, as it contains less donor-reliant organisations than other datasets.

Do Donors Minimise Information Cost?

We predicted that donors who experience the price–information trade-off care about the charity price but dislike exerting effort, and so use “rules of thumbs”, signals, and rating or certification agencies to gauge the charity price and guide their giving decisions. We also predicted that charities with higher fundraising expenses might receive more donations, as it decreases the information cost.

Do Donors Use “Rules of Thumb” to Guide Their Giving Decisions?

Donors sometimes use “rules of thumb” to gauge the charity price and minimise effort. For example, although donors from Arumi et al. (2005) rarely researched their beneficiary charity before or after giving, and donors from Breeze (2010) often could not recall the charities and causes they supported, respondents from both studies often applied “rules of thumb” to gauge the quality of the charity, such as whether they recognised the charity’s name (“recognition heuristic”; see Gigerenzer and Todd 1999), how many people volunteered at the charity, or whether they received a newsletter detailing the charity’s accomplishments.

Donors might also reduce the amount they give if they suspect their donations were used on expenses extraneous to the cause. In Bekkers and Brutzen’s (2007) experiment, for example, donors who received the fundraising campaign letter in “plain” envelopes were more likely to give, and at higher amounts, than donors who received the fundraising campaign letter in “flashy” envelopes. Similarly, in Landry et al.’s (2010) experiment, individuals were offered either nothing, a small gift, or a large gift for giving to a Hazards Centre. Individuals who previously gave to the Centre were more likely to give when they were not offered a gift.

Charities can even signal their quality by providing more information on itself. Saxton et al. (2011) found that charities that disclosed more financial and performance-related information on their website received more donations than those that disclosed less. Aguiar et al. (2008) found that individuals are more willing to give to a charity when they know who their beneficiary is and how exactly their donations would be used (also see Branas-Garza 2006). Most subjects in McDowell et al.’s (2010) experiment, in contrast, gave to the charity once they read about its mission and goals, and without reading its program ratio.

Charities can adopt “announcement strategies” to decrease donors’ information cost. Specifically, by announcing the receipt of a large donation to the public, the charity provides a signal to potential donors that the benefactor gave because s/he believes the charity is trustworthy (Vesterlund 2003). The donor who faces the price–information trade-off might respond to this strategy if it helps minimise the information cost and gives her confidence that her donation will go to an adequate charity.

An example of an announcement strategy is “matching”, where a lead donor matches the donations of other donors at a given rate, up to a maximum amount. Karlan and List (2007) studied the matching strategy by sending a fundraising letter to over 50,000 prior donors about a liberal organisation. Donations were either not matched, or matched where the lead donor gave 1, 2, or 3 dollars to the organisation for every dollar donated. They found that donors in the matched treatments were more likely to give, and gave more, than donors whose donations were not matched (see Karlan et al. 2011 for a similar study, but also see Rondeau and List 2008, for contradictory results).

Another announcement strategy is a “challenge gift”, where a donor commits to giving a set amount of money to a charity, can also influence giving. List and Lucking-Reiley (2002) demonstrated this by asking 3000 Central Florida residents for donations to the Centre for Environmental Policy Analysis. They found that increasing the level of the challenge gift contribution from 10 to 67 % of the campaign goal resulted in nearly a sixfold increase in overall donations (also see Rondeau and List 2008).

Observation 3 Some donors use rules of thumb, such as charities’ level of spending on expenses and the level of information they provide on themselves, to guide their giving decisions.

Do Donors Use Agencies to Inform Their Giving Decisions?

Watchdog agencies provide information to donors about the quality of charities. For example, Charity Navigator rates charities out of 4 stars, the American Institute of Philanthropy (AIP; now called CharityWatch) rates charities from A + to F, and Better Business Bureau (BBB) Wise Giving Alliance in the US, Central Bureau Fondsenwerving (CBF) in the Netherlands, and Deutsches Zentralinstitut fuer soziale Fragen (DZI) in Germany award accreditation seals to charities that comply with their standards. Typical standards include whether financial statements are audited and the proportion of donations spent on fundraising and administrative expenses (Ortmann and Svitkova 2007). By meeting or performing well against these standards, charities demonstrate that they use donations responsibly.Footnote 8

Based on the theoretical model, donors who face the price–information trade-off use these agencies to reduce the information cost and ensure their donations are used appropriately. They are more likely to give to accredited charities, or charities with high ratings, than to charities that either are not accredited or have low ratings.

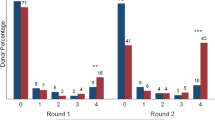

Table 3 summarises the findings from studies that examine the relationship between ratings and giving. The “Increase (Pass)” column contains the qualitative effect of an increase in rating (e.g. from C to C+; two stars to three) or a pass rating on giving. Symbol “+” means an increase in rating or a pass rating corresponded to more giving; symbol “−”means a decrease in rating or a fail rating corresponded to less giving; and “0” means the effect was statistically insignificant. The “Decrease (Fail)” column contains the qualitative effect of a decrease in rating or a fail rating on giving. Symbol “+” means that a decrease in rating or a fail rating corresponded to more giving; symbol “−” means that a decrease in rating or a fail rating corresponded to less giving; and “0” means the effect was statistically insignificant. If donors face the price–information trade-off, column “Increase (Pass)” should contain symbol “+” and “Decrease (Fail)” should contain symbol “−”.

Donors generally used agencies to inform their giving, although not all studies showed that highly rated and/or accredited charities were rewarded with more donations. This can be explained using the theoretical model. Namely, the financial details of most charities in Berman and Davidson (2003) were not publicly available at the time of the analysis. The accountability rating would thus not affect donations if the information search was too costly. Silvergleid (2003) found that the AIP quarterly ratings had an insignificant effect on donations. Since AIP rates charities on a scale of A+, A, A−, …, F, the “decrease” in rating from A to A- might not be steep enough to induce donors to search for charities with a lower price. Lastly, Sloan (2009) conjectured that “did-not-pass” ratings did not correspond to lower donations, as charities that did-not-pass were not obligated to publish the result on their websites. Since donors have to search the Wise Giving Alliance database to determine whether the charity passed, the information search might also have been too costly.

Observation 4 Although the evidence is mixed, it appears that highly rated or accredited charities tend to receive more donations than lower rated or unaccredited charities.

Cnaan et al. (2011), in contrast, noted that watchdog agencies are not widely used. Using the responses from three waves of the Harris Poll Online Panel (HPOL), they found that most donors (77.7 %), bar those engaged in advocacy or systematically making large donations, do not use watchdog ratings. The authors thus question the relevance of watchdog agencies to the average donor, and argue that they are either unaware of them, or do not care about the quality of charities (Horne et al. 2005; but also see Bekkers 2003, 2010; Svitkova 2013 and the evidence therein).

In contrast, Bekkers (2006) shows that knowing about accreditation seals can lead to greater trust in, and giving to, charities. Using the first two waves of the Giving in the Netherlands Panel Survey (2002–2004), he found that awareness of the accreditation seal is positively related to confidence in the not-for-profit sector, and that those with no/little confidence in the sector gave 130 Euros per year, those with some confidence gave 257 Euros per year, and those with quite some/very much confidence donated 393 Euros per year.

Do Higher Fundraising Expenses Correspond to More Giving?

Based on the model, fundraising expenses can have countervailing effects on giving (Okten and Weisbrod 2000). For the price-sensitive donor, higher fundraising expense decreases giving. For the donor who dislikes information cost, higher fundraising expenses increases giving as it raises the profile of the charity and decreases costly information search.Footnote 9 The total effect of fundraising on giving thus depends on which force is stronger.

Column “Fundraising” in Table 2, “Do Donors Use Agencies to Inform Their Giving Decisions?” section, contains the qualitative effect of charities’ fundraising expense in the previous year on donations. “+” means fundraising expense and donations were positively correlated, as donors gave more to charities with higher fundraising expenses; “−”means they were negatively correlated; “0” means the effect was statistically insignificant, and “N/A” means it was excluded from the study. For evidence that suggests donors face the price–information trade-off, “+” should be observed across the Fundraising column and “−”should be observed across the PRICE column, for it implies that donors used fundraising as a way to glean more information on charities with minimal effort, or received better information on charities through more effective fundraising activities, but were price sensitive as they gave less as the charity price increased.

17 of the 23 studies reviewed in the “Empirical Evidence” section provide evidence in favour of the price–information trade-off. Namely, fundraising expenses had countervailing effects on giving—the direct effect of fundraising expense increased giving, while the indirect effect through the charity price decreased donations.

Observation 5 Based on the studies reviewed in the “Empirical Evidence” section, charities that spent more on fundraising expenses in the previous year received greater donations in the current year, however, charities with a greater price received less private donations.

Note that the countervailing effects of fundraising expenses on donations cannot be distinguished in archival and survey data. As such, the interpretation of the effect of fundraising expenses on giving is debateable. For example, although higher fundraising expenses can increase giving through reducing the information cost, it might also be the result of charities using more sophisticated solicitation mechanisms (e.g. see Wiepking 2010; Bekkers and Wiepking 2011) and better designed fundraising drives (Pallotta 2013).Footnote 10 A carefully designed experiment, however, could disentangle these two effects.Footnote 11 Specifically, the experimenter could hold specific design elements constant (such as the number of times the donee is solicited), while varying one element (such as fundraising expense). Causation can be inferred if the variation of the one element is accompanied with greater giving.

Concluding Remarks

We set out to understand how donors decide about which charity to give to, and whether they use the charity price to guide their giving decisions. Specifically, we were interested in the merits of the claim that donors do not use quality-assurance entities such as charity watchdogs to help donors make “smart” giving decisions (e.g. Arumi et al. 2005; Sargeant 1999; Sargeant and Ford 2006; Sargeant and Jay 2010). If this were generally true, then the various means of charity quality assurance would be wasted. We thus asked: How do donors decide about which charity to give to, and do donors use the charity price to guide their giving decisions?

To this end, we proposed a theoretical model to explain the conditions under which taste, charity price, and information cost inform giving decisions. The central insight from the model is that giving decisions might be informed by a price–information trade-off, where donors care about the charity price, but are averse to searching for it because they dislike exerting effort and thus incur an information cost. In consequence, donors might seek ways to minimise the information cost. Simultaneously, charities that spend more money on fundraising costs might generate more donations than those that do not, as they are able to raise their profile and reduce the information price.

We reviewed the literature to test the explanatory power of the theoretical framework. The evidence suggests that donors generally care about the charity price but also seek to minimise the information cost. This supports the hypothesis that the price–information trade-off can affect donors’ giving decisions.

If the price–information trade-off does inform giving decisions, we suggest for policy-makers and academics to explore the role of information cost on donors’ giving decisions. In particular, measures that can reduce the information price, such as certification or watchdog agencies, may be beneficial for donors to whom the price–information trade-off matters. These agencies guarantee that charities with a seal of approval or a specific rating spend an appropriate amount on expenses that do not contribute to producing charitable output. Due to the public good nature of information, a central agency that provides information on all charities’ price would be more cost effective than individual charities revealing their price metric individually, or publicising themselves through costly fundraising and/or advertising. For this to work, these portals need to be widely publicised and trusted. If successful, the information asymmetry problem afflicting charities will be allayed and the charity market will move towards a more competitive model where donations flow to charities with a lower price, at least in theory.

Although our central hypothesis—donors care about charity price and information cost, can be explained by the literature—it is unclear which of the two a typical donor cares about more—the charity price or the information cost. If the former, policy-makers could encourage greater efficiency and effectiveness among charities in line with our prior recommendation. The more involved policy-maker and researcher could also consider how different types of charity prices (e.g. fundraising expenses which are signalled through pamphlets or celebrity endorsements, or through financial reports) influence the giving patterns of different types of donors (e.g. regular versus intermittent givers; givers versus non-givers; wealthy givers versus average givers). If the latter, policy-makers face additional problems—is the information cost problem better attenuated through the presence of watchdog agencies or sophisticated fundraising drives? In fact, what exactly brings about the information cost? Is it the number of solicitations received by the giver, the minutes of television airtime the charity receives, or the number of celebrities that endorse the charity? Indeed can the charity sector ever mimic a competitive market if there are these “frictions”? Our model allows us to formulate the basis of several testable hypotheses which could be explored if the policy-maker believes that expanding the pool and creating a more efficient and effective allocation of resources in the charitable sector is important.

Notes

Some of which might not have a reasonable explanation; see Ortmann and Schlesinger 2003.

The charity price might be used as a proxy for the scale of output delivered by the charity, even though different charities might produce different levels of output with the same amount of input (i.e. donations). Suppose, for example, that Charities A and B spend $0.2 of a $1 donation on administration and fundraising. Suppose, also, that Charity A uses $0.8 to produce $2 worth of charitable output, but Charity B uses $0.8 to produce $0.5 worth of charitable output. Although both charities spend equal amounts of donations on producing output, Charity A produces more output than Charity B.

A donor who uses the charity price to guide her giving decisions is indifferent between Charities A and B. However, Charity A is more worthy of being funded, all other things being equal, as it produces more output with the same amount of input. For ease of exposition, for the remainder of the paper we assume that the amount the charity spends on charitable output) equals the amount of charitable output produced.

The amount of output produced by charities is arguably related to the level of outcomes produced by the charity, as opposed to output. Needless to say that measuring outcomes, or social impact, is a major challenge (e.g. Forbes 1998, or Herman and Renz 1999, or recent attempts to measure social impact).

These are indeed only illustrations; a more formal analysis would be necessary to provide crisp predictions for aggregate outcomes and specific donor behaviour.

We refer the reader to Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) for an exposition of component 1 (i.e. stand-alone benefit) of the utility function. Bekkers and Wiepking’s (2011) literature review identified eight drivers of giving: awareness of needs; solicitation; costs and benefits; altruism; reputation; psychology benefits; values; efficacy.

SEA shows the charity’s effectiveness in fulfilling its mission (Parsons 2003).

Weisbrod and Dominguez (1986) also define price in terms of tax benefits; hence, we present a simplification of their model.

“Relevant and reliable” data include charities that report administrative and fundraising expenses greater than US$1000, are at least 4 years old, received more than US$100,000 in donations in prior years, and received donations equal to at least 10 % of the previous year’s revenue.

Another issue is whether watchdog agencies can evaluate charities effectively. Ling and Neely (2012) affirm that Charity Navigator can identify top-performing charities in the human-related sector, as charities that receive a four-star rating from Charity Navigator hold lower levels of excess cash and compensation expenses, and that their compensation is less sensitive to performance. In spite of this, Charity Navigator awarded Central Asia Institute (CAI) a four-star rating, and maintained the rating even after allegations aired by tv program 60 Minutes suggested that Greg Mortenson, then the CEO of CAI, mismanaged donors’ funds (Kristof 2011).

This implies that charities might enter a rat-race, where they spend successively more on fundraising to receive more donations. However, engaging in the rat race is no longer profitable once the marginal dollar spent on fundraising expense is less than the resultant marginal donation. And even if the marginal dollar spent on fundraising expense was never less than the resultant marginal donation, donors are heterogeneous. Not all donors are afflicted with the price–effort trade-off, and so not all donors would give more to better publicised charities.

We thank Rene Bekkers for pointing this out.

We thank Rene Bekkers for pointing this out.

References

Aguiar, F., Branas-Garza, P., & Miller, L. M. (2008). Moral distance in dictator games. Judgment and Decision Making, 3(4), 344–354.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100, 464–477.

Arumi, A. M., Wooden, R., Johnson, J., Farkas, S., Duffett, A., and Ott, A. (2005). The Charitable Impulse. Those who give to charities - and those who run them - talk about what’s needed to keep the public’s trust. Public Agenda.

Bagwell, S., de Las Casas, L., van Poortvliet, M., & Abercrombie, R. (2013). Money for Good UK. London: Understanding donor motivation and behaviour. New Philanthropy Capital.

Bekkers, R. (2003). Trust, accreditation, and philanthropy in the Netherlands. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32(4), 596–615.

Bekkers, R. (2006). Keeping the Faith: Origins of Confidence in Charitable Organizations and its Consequences for Philanthropy. NCVO/VSSN Researching the Voluntary Sector Conference, Warwick University, Coventry.

Bekkers, R. (2010). The benefits of accreditation for fundraising nonprofit organizations in the Netherlands. In M. K. Gugerty & A. Prakash (Eds.), Nonprofit clubs: Voluntary regulation of nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations (pp. 253–279). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bekkers, R., & Brutzen, O. (2007). Just keep it simple: a field experiment on fundraising letters. International Journal of Nonprofit and Volunary Sector Marketing, 12(4), 371–378.

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 924–973.

Berman, G., & Davidson, S. (2003). Do donors care? Some Australian evidence. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(4), 421–429.

Blackbaud, (2009). 2009 State of the Not-for-Profit Industry Survey. In association with the Resource Alliance: United Kingdom Survey Results.

Borgloh, S., Dannenberg, A., & Aretz, B. (2010). Small is Beautiful - Experimental Evidence of Donors’ Preferences for Charities. ZEW - Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No. 10-052. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1663639 or doi:10.2139/ssrn.1663639

Borgloh, S., Dannenberg, A., & Aretz, B. (2013). Small is beautiful - experimental evidence of donors’ preferences for charities. Economics Letters, 120, 242–244.

Bowman, W. (2006). Should donors care about overhead costs? Do they care? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(2), 288–310.

Branas-Garza, P. (2006). Poverty in dictator games: Awakening solidarity. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60, 306–320.

Breeze, B. (2010). How donors choose charities. University of Kent, Centre for Charitable Giving and Philanthropy. London: Alliance Publishing Trust.

Buchheit, S., & Parsons, L. M. (2006). An experimental investigation of accounting information’s influence on the individual giving process. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25, 666–686.

Callen, J. (1994). Money donations, volunteering and organizational efficiency. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 67(3), 215–228.

Chen, G. (2009). Does meeting standards affect charitable giving? An empirical study of New York metropolitan area charities. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 19(3), 349–365.

Chhaochharia, V., and Ghosh, S. (2008). Do charity ratings matter? No 08001, Working Papers, Department of Economics, College of Business, Florida Atlantic University.

Cnaan, R. A., Jones, K., Dickin, A., & Salomon, M. (2011). Nonprofit watchdogs: Do they serve the average donor? Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 21(4), 381–397.

Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. (2006). Giving Australia: Research on Philanthropy in Australia. Canberra: Report on Qualitative Research.

Department of Family and Community Services. (2005). Giving Australia: Research on Philanthropy in Australia. Canberra.

Forbes, D. P. (1998), Measuring the Unmeasurable: Empirical Studies of Nonprofit Organization Effectiveness from 1977 to 1997. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, pp. 183–202.

Frumkin, P., & Kim, M. T. (2001). Strategic positioning and the financing of nonprofit organizations: Is efficiency rewarded in the contributions marketplace? Public Administration Review, 61(3), 266–275.

Gigerenzer, G., & Todd, P. M. (1999). Simple heuristics that make us smart. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, T. P., Knock, C. L., & Neely, D. G. (2009). The roel of rating agencies in the market for charitable contributions: An empirical test. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 28(6), 469–484.

Grant, L. G. (2010). The Response to Third-Party Ratings: Evidence of the Effects on Charitable Contributions. Working Paper.

Greenlee, J., & Brown, K. (1999). The impact of accounting information on contributions to charitable organizations. Research in Accounting Regulation, 13, 111–125.

Herman, R. D., & Renz, D. O. (1999). Theses on nonprofit organizational effectiveness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28, 107–126.

Hope Consulting (2010). Money for good: The US market for impact investments and charitable gifts from individual donors and investors. Retrieved June 9, 2013 from http://www.hopeconsulting.us/pdf/Money%20for%20Good_Final.pdf

Horne, C., Johnson, J., & Van Slyke, D. (2005). Do Charitable donors know enough—and care enough—about government subsidies to affect private giving to nonprofit organizations? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 34(1), 136–149.

Jacobs, F. A., & Marudas, N. P. (2009). The combined effect of donation price and administrative inefficiency on donations to US nonprofit organizations. Financial Accountability & Management, 25(1), 33–53.

Karlan, D., & List, J. A. (2007). Does price matter in charitable giving? Evidence from a large-scale natural field experiment. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1774–1793.

Karlan, D., List, J. A., & Shafir, E. (2011). Small matches and charitable giving: Evidence from a natural field experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 344–350.

Khanna, J., Posnett, J., & Sandler, T. (1995). Charity donations in the UK: New evidence based on panel data. Journal of Public Economics, 56(2), 257–272.

Khanna, J., & Sandler, T. (2000). Partners in giving: The crowding-in effects of UK government grants. European Economic Review, 44, 1543–1556.

Krishnan, R., Yetman, M., & Yetman, R. J. (2006). Expense Misreporting in Nonprofit Organizations. Accounting Review, 81(2), 399–420.

Kristof, N. D. (April 11, 2011). ‘Three cups of tea,’ spilled. Retrieved May 30, 2012, from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/opinion/21kristof.html. The New York Times

Landry, C. E., Lange, A., List, J. A., Price, M. K., & Rupp, N. G. (2010). Is a donor in hand better than two in the bush? Evidence from a natural field experiment. American Economic Review, 100(3), 958–983.

Lasby, D. (2004). The Philanthropic Spirit in Canada: Motivations and Barriers. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

Ling, Q., & Neely, D. G. (2012). Implications of being a highly rated organization: Evidence from four-star rated nonprofits. Accounting and Finance Research, 1(1), 3–17.

List, J. A., & Lucking-Reiley, D. (2002). The effects of seed money and refunds on charitable giving: experimental evidence from a University capital campaign. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 215–233.

Madden, K. (2006). Giving and Identity: why affluent Australians give—or don’t—to community causes. Australian Journal of Social Issues., 41, 453–476.

Marcuello, C., & Salas, V. (2001). Nonprofit organizations, monopolistic competition, and private donations: evidence from Spain. Public Finance Review, 29(3), 183–207.

Marudas, N. P. (2004). Effects of nonprofit organization wealth and efficiency on private donations to large nonprofit organizations. Research in Government and Nonprofit Accounting, 11, 71–91.

Marudas, N. P., & Jacobs, F. A. (2004). Determinants of Charitable donations to large U.S. higher education, hospital, and scientific research NPOs: New evidence from panel data. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 15(2), 157–179.

Marudas, N. P., & Jacobs, F. A. (2007). The extent of excessive or insufficient fundraising among US arts organizations and the effect of organizational efficiency on donations to US arts organizations. International Journal of Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Marketing, 12(3), 267–273.

Marudas, N. P., & Jacobs, F. A. (2008). The effect of organizational inefficiency on donations to U.S. nonprofit organizations and the sensitivity of results to different specifications of organizational size. Proceedings of ASBBS, 15(1), 318–326.

McDowell, E., Li, W., & Smith, P. C. (2010). Investigating individual donor information search: The relevance of nonprofit efficiency and nonfinancial information. American Accounting Association—Auditing Section—Annual Meeting.

Okten, C., & Weisbrod, B. A. (2000). Determinants of donations in private nonprofit markets. Journal of Public Economics, 75, 255–272.

Ortmann, A., & Schlesinger, M. (2003). Trust, Repute, and the Role of Nonprofit Enterprise. In H. Anheier & A. Ben-Ner (Eds.), The study of the nonprofit enterprise (pp. 77–114). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Ortmann, A., & Svitkova, K. (2007). Certification as a viable quality assurance mechanism in transition economies: Evidence, theory, and open questions. Prague Economic Papers, 16(2), 99–114.

Pallotta, D. (2013) The way we think about charity is dead wrong. TED. Ideas worth spreading. Retrieved September 6, 2014 from http://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pallotta_the_way_we_think_about_charity_is_dead_wrong.

Parsons, L. M. (2003). Is accounting information from nonprofit organizations useful to donors? A review of charitable giving and value-relevance. Journal of Accounting Literature, 22, 104–129.

Posnett, J., & Sandler, T. (1989). Demand for charity donations in private non-profit markets. the case of the U.K. Journal of Public Economics, 40, 187–200.

Rondeau, D., & List, J. A. (2008). Matching and challenge gifts to charity: evidence from laboratory and natural field experiments. Experimental Economics, 11, 253–267.

Sargeant, A. (1999). Charitable giving: Towards a model of donor behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 215–238.

Sargeant, A., & Ford, J. B. (2006). ’The power of brands’ stanford social innovation review (pp. 41–47). Greensburg: Winter.

Sargeant, A., & Jay, E. (2010). Fundraising management, analysis planning and practice (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Saxton, G. D., Neely, D., & Chao, G. (2011). Web disclosure and the market for charitable contributions. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1912966.

Sen, A. (1977). Rational fools: a critique of the behavioural foundations of economic theory. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 6, 317–344.

Silvergleid, J. E. (2003). Effects of watchdog organizations on the social capital market. New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising, 41, 7–26.

Sloan, M. (2009). The effects of nonprofit accountability ratings on donor behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(2), 220–236.

Svitkova, K. (2013). Certification and its impact on quality of charities. Prague Economic Papers, 22(4), 542–557.

Szper, R., & Prakash, A. (2011). Charity watchdogs and the limits of information-based regulation. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22, 112–141.

The Centre on Philanthropy at Indiana University. (2009). The 2008 Study of High Net Worth Philanthropy. Issues Driving Charitable Activities among Affluent Households. Retrieved March 8, 2015 from http://www.philanthropy.iupui.edu/files/file/final_hnw_08_study_6_1_09_2.pdf

Tinkelman, D. (1998). Differences in sensitivity of financial statement users to joint cost allocations: The case of nonprofit organizations. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 13(4), 377–393.

Tinkelman, D. (1999). Factors affecting the relation between donations to not-for-profit organizations and an efficiency ratio. Research in Government and Nonprofit Accounting, 10, 135–161.

Tinkelman, D. (2004). Using nonprofit organizational-level financial data to infer managers’ fund-raising strategies. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9/10), 2181–2192.

Tinkelman, D., & Mankaney, K. (2007). When is administrative efficiency associated with charitable donations? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(1), 41–64.

Trussel, J. M., & Parsons, L. M. (2008). Financial reporting factors affecting donations to charitable organizations. Advances in Accounting, 23, 263–285.

Vesterlund, L. (2003). The information value of sequential fundraising. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 627–657.

Vesterlund, L. (2006). Why do people give? In R. Steinberg & W. W. Powell (Eds.), The nonprofit sector (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Yale Press.

Wealth, Barclays. (2010). Barriers to giving. A white paper in co-operation with Ledbury Research. London: Barclays Weath.

Weisbrod, B. A., & Dominguez, N. D. (1986). Demand for collective goods in private nonprofit markets: Can fundraising expenditures help overcome free-rider behavior? Journal of Public Economics, 30(1), 83–96.

Wiepking, P. (2010). Democrats support international relief and the upper class donates to art? How opportunity, incentives and confidence affect donations to different types of charitable organizations. Social Science Research, 39, 1073–1087.

Yetman, M. H. (2009). Economic consequences of expense misreporting in nonprofit organizations: Are donors fooled? Working Paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank two referees for this journal for the latter’s helpful comments. Special thanks to Rene Bekkers. The usual caveat applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, J., Ortmann, A. Do Donors Care About the Price of Giving? A Review of the Evidence, with Some Theory to Organise It. Voluntas 27, 958–978 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9567-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9567-1