Abstract

This study presents a framework for understanding the processes through which volunteers’ perception of relational job design influences their turnover intentions and time spent volunteering. Data sourced from an international aid and development agency in the United Kingdom (n = 534 volunteers) show that volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed (1) report lower intentions to leave their voluntary organization due to their commitment to the voluntary organization; and (2) dedicate more time to volunteering because they are more committed to the beneficiaries of their work. These findings make a theoretical contribution by uncovering two mechanisms that explain how the positive consequences of relational job design unfold.

Résumé

Cette étude présente un cadre decompréhension desprocessus par lesquels la perceptiondes bénévoles sur la conception relationnelle de leur travail influe surleurs intentions de quitter leur organisation et le temps qu’ilspassent dans leurs activités bénévoles. Des données provenant d’une organisation internationale d’aide et de développement du Royaume Uni (n = 534 bénévoles) montrent que les bénévoles qui estiment que leurs rôles sont conçus de manière relationnelle (1) font part d’intentions plus faibles de quitter leur organisation bénévole en raison de leur engagement envers celle-ci, et (2) consacrent plus de temps au bénévolat car ils sont plus dévoués ceux qui bénéficient de leur travail. Ces résultats apportent une contribution théorique en découvrant deux mécanismes qui expliquent l’évolutiont des conséquences positives de la conception relationnelle des tâches.

Zusammenfassung

Diese Studie präsentiert ein Untersuchungsmodellzum Verständnis der Prozesse, durch die die Wahrnehmung einer beziehungsorientierten Arbeitsgestaltung durch Freiwillige Einfluss auf deren Absicht, die Freiwilligentätigkeit zu beenden, und den zeitlichen Umfang ihrer freiwilligen Tätigkeiten nimmt. Daten einer internationalen Hilfs- und Entwicklungs organisation in Großbritannien (n = 534 Freiwillige) zeigen, dass Freiwillige, die ihre Rollen als beziehungsorientiert wahrnehmen (1) aufgrund ihres Commitments gegenüber der ehrenamtlichen Organisation weniger dazu geneigt sind, ihre Freiwilligentätigkeit zu beenden, und (2) aufgrund ihres Commitments gegenüber den Leistungsempfängernmehr Zeit für freiwillige Tätigkeiten aufbringen. Diese Ergebnisse leisten einen theoretischen Beitrag zur Analyse von zwei Wirkungsmechanismen, die erklären, wie sich die positiven Folgen einer beziehungsorientierten Arbeitsgestaltung entfalten.

Resumen

El presente estudio presenta un marco para comprender los procesos mediante los cuales la percepción del diseño del trabajo relacional por parte de los voluntarios influye en sus intenciones de rotación y en el tiempo dedicado al voluntariado. Los datos tomados de una agencia internacional de ayuda y desarrollo en el Reino Unido (n = 534 voluntarios) muestran que los voluntarios que perciben que sus funciones están diseñadas relacionalmente (1) notifican menos intenciones de abandonar su organización voluntaria debido a su compromiso con la organización voluntaria; y (2) dedican más tiempo al voluntariado porque están más comprometidos con los beneficiarios de su trabajo. Estos hallazgos representan una contribución teórica descubriendo dos mecanismos que explican cómo se desarrollan las consecuencias positivas del diseño del trabajo relacional.

摘要

志愿者对关系工作设计(relational job design)的认知影响他们的离职意向以及从事志愿工作的时间。本研究提出了框架,以理解这一过程。来自英国的国际援助与发展机构(数量 = 534名志愿者)的数据显示,如果志愿者发现自己的角色是以关系为基础进行设计的,(1)他们离开自己的志愿组织的意向较低,因为他们对志愿组织的忠诚度较高;(2)他们会投入更多时间从事志愿工作,因为他们对自己工作的受益人更加忠诚。这些研究结果通过揭示能够用以解释关系工作设计产生正面效果的两个机制,从而做出了一定的理论贡献。

ملخص

تقدم هذه الدراسة إطارا˝ لفهم الإجراءات التي من خلالها يدرك المتطوعين علاقة تأثيرتصميم الوظائف على نوايا عائداتهم والوقت الذي يقضوه في العمل التطوعي. تظهر بيانات من مصادر من المساعدات الدولية ووكالة التنمية في المملكة المتحدة (ن = 534متطوع) أن المتطوعين الذين يرون أن دورهم مصمم لتحفيزهم (1) يذكرون النوايا الأقل لترك منظمتهم التطوعية بسبب إلتزامهم للمنظمة التطوعية؛ و (2) تكريس المزيد من الوقت للعمل التطوعي لأنهم أكثر إلتزاما˝ للمستفيدين من عملهم. هذه النتائج تقدم مساهمة نظرية عن طريق كشف آليتين يشرحان كيفية العواقب الإيجابية لتصميم الوظائف المحفزة تتكشف.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In their review of volunteering research, Snyder and Omoto (2008) identified two questions of interest to both researchers and practitioners: “Why do people volunteer? And, what sustains people in their volunteer work”? (p. 7). The first question has garnered most of the attention among researchers. Indeed, the field is rich with research on individual characteristics (e.g., demographics, personality traits, motives) that drive people to initiate volunteering (Lindenmeier 2008; Studer and von Schnurbein 2013). Their second question, on the other hand, has yet to be fully explored. Doing so is pressing because volunteering has become increasingly episodic, with individuals volunteering for shorter periods of time with numerous organizations (Snyder and Omoto 2008). This results in higher costs for voluntary organizations, in terms of lost volunteer time and increases in induction and training expenses. Moreover, higher volunteer mobility reduces organizational learning that comes with longer tenure at an organization (Carley 1992). Accordingly, we examine an unexplored factor in research on the management of volunteers that has the potential to ignite dedication in volunteers, such that they actively commit time to volunteering and express a desire to remain volunteering for the organization. This factor is relational job design (Grant 2007).

Grant (2007) developed a conceptual model of relational job design in the paid employment context. He stated that the relational architecture of jobs refers to a job’s structural properties that enable employees to connect with others. He proposed that when jobs are designed such that they enable employees to see the impact that they make on those who benefit from their work, employees invest more time and energy into tasks that help these beneficiaries. Although some studies have shown that the relational properties of jobs lead to desirable outcomes for organizations in the paid employment context (e.g., Grant et al. 2007; Grant 2008), no research, to our knowledge, has examined this factor in the volunteering context. This is surprising given that this facet of job design may be particularly relevant for enhancing the commitment and retention of volunteers and the time that volunteers dedicate to their service, as the “prosocial” or “value” motive is one of the strongest reasons why individuals initiate volunteering behavior (e.g., Clary et al. 1996; Okun and Schultz 2003; Omoto and Snyder 1995). Accordingly, we contribute to the volunteering literature by examining the impact of an overlooked aspect of volunteers’ job design on two important outcomes for voluntary organizations, namely, turnover intentions and the time that volunteers spend in dedication to their service (e.g., Cnaan and Cascio 1999; Craig-Lees et al. 2008; Hustinx 2010).

A second contribution lies in our response to Wilson’s (2012) call to unearth the mechanism(s) that explain hypothesized relationships in the volunteering context. Specifically, we ask, if there are effects of relational job design on volunteer outcomes, how do these effects occur? In other words, what are the mechanisms through which these effects manifest? Answering this question is theoretically important, as it lays the groundwork for a comprehensive theory on the management of volunteers (Studer and von Schnurbein 2013; Wilson 2012). Moreover, understanding the linchpin(s) that link relational job design with important outcomes can guide practitioners in the design of volunteer roles to maximize retention and the hours volunteers dedicate to their service.

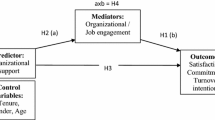

In the present study, we test a model that portrays the roles of two foci of commitment, namely, commitment to the voluntary organization and commitment toward those who benefit from volunteering activities, as mediators in the relationship between relational job design and volunteer outcomes. Drawing from the multiple foci of commitment literature (Becker 1992; Reichers 1985), our model posits that the negative relationship between relational job design and turnover intentions is mediated by volunteers’ organizational commitment, while the positive link between relational job design and time spent volunteering is mediated by volunteers’ commitment to beneficiaries. A diagram of the theoretical model is depicted in Fig. 1.

In summary, the development and test of our theoretical model advances research in the volunteering literature by examining relational job design, an unexplored factor that has the potential to affect two of the most important outcomes of interest to voluntary organizations, that is, turnover intentions and the time that volunteers spend volunteering (Hustinx 2010). Moreover, we present two unique mediators that explain the processes by which relational job design is related to these valued outcomes. In doing so, we respond to calls to extend theory on the management of volunteers by adapting research derived from the paid employment into the voluntary context (Cnaan and Cascio 1999; Shantz et al. 2013b; Studer and von Schnurbein 2013) and by examining organization-relevant factors that influence volunteer behavior (Studer and von Schnurbein 2013; Wilson 2012).

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Relational Job Design

One of the most powerful influences on behavior in organizations is the design of a person’s job (Cordery and Parker 2008). Although most job design theory and research has focused on Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) job characteristics model (e.g., Millette and Gagne 2008; Shantz et al. 2013a), recently, Grant (2007) built on this work to develop a theory of relational job design in the paid employment context. The theory states that when jobs are designed to provide incumbents with an opportunity for them to perceive a positive impact on beneficiaries, they invest more time and energy into their tasks. Research in the paid employment context has shown that employees who feel that they make an impact on others persist more at work (Grant et al. 2007) and exhibit greater job dedication, helping behavior (Grant 2008), and job performance (Grant 2012). Notwithstanding these promising findings from the paid employment sector, this aspect of job design has not been investigated in the context of volunteer work. It may be especially relevant here, given that the initial motivation for volunteering is oftentimes tightly linked to a desire to help others (e.g., Clary et al. 1996; Okun and Schultz 2003; Omoto and Snyder 1995).

Volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed are able to make a connection between their actions and the resulting positive consequences for others. The perception of having an impact on the beneficiaries of one’s actions is thus a central feature of the relational design of jobs. According to relational job design theory, however, perceptions of relational job design go beyond a state of awareness of the impact that one makes on others. They also encompass “a state of subjective meaning, a way of experiencing one’s work as significant and purposeful through its connection to the welfare of other people” (Grant 2007, p. 399). Although the majority of volunteers are motivated by prosocial values (e.g., Clary et al. 1996; Okun and Schultz 2003; Omoto and Snyder 1995), volunteers differ in the extent to which they believe that their actions, while volunteering, are meaningfully connected to those who benefit from their volunteer activities.

The positive consequences of volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed can be explained through expectancy theory (Vroom 1964). This theory states that individuals are motivated when they believe that their efforts lead to higher levels of performance, which, in turn, results in valuable rewards. In the context of volunteering, volunteers who believe that they make an impact on the recipients of their activities report positive outcomes because they are able to see a clear link between their actions and the outcomes of their actions; in essence, perceiving their actions as impactful on beneficiaries is a valued reward for volunteers. Hence, they are likely to remain with the voluntary organization and commit more time to their volunteering work because they see the instrumentality of their volunteering activities in terms of impacting others. Expectancy theory (Vroom 1964) and empirical work on relational job design in the paid context (e.g., Grant 2008) leads us to hypothesize:

H1

Perceptions of relational job design are negatively related to turnover intentions from the voluntary organization.

H2

Perceptions of relational job design are positively related to time spent volunteering.

The Mediating Role of Commitment: Two Foci, Two Paths

Meyer et al. (2006) defined commitment as a force that connects an individual to a target, and to a course of action that is pertinent to the target. This definition has at least two important implications for the present study. First, it recognizes that individuals become committed to various foci (Reichers 1985). Indeed, research has established that commitment to the organization (Meyer and Allen 1991), top management, co-workers (Becker 1992), a union (Gordon and Ladd 1990), one’s occupation (Ellemers et al. 1998; Meyer et al. 1993), and customers (Reichers 1986; Siders et al. 2001) are distinct. In the current investigation, we examine two foci of commitment that are particularly relevant in the volunteering context, namely, commitment to the organization, and commitment to the beneficiaries of volunteering activities. The former is defined as a positive emotional attachment to the voluntary organization (Meyer and Allen 1991); the latter is defined as dedication to the people who are impacted by volunteering efforts (Grant 2007).

Second, the definition reflects that an individual’s bond with a target commits the person to behaviors that are relevant to that target, resonating with the multiple foci of commitment literature. Early foci of commitment researchers noted that organizational commitment, in a paid context, is best understood as a collection of commitments (Becker 1992; Reichers 1985). Indeed, employees experience several commitments to the goals and values of a variety of groups in an organization. Hence, it is important to not only understand simple organizational commitment, but also different foci of commitment (Cheng et al. 2003). There has been some research in the paid employment context that supports this contention. For instance, research shows that organizational commitment is better suited to explain organization-relevant outcomes, whereas commitment to the supervisor is better able to explain supervisor-relevant outcomes (Becker et al. 1996; Cheng et al. 2003).

Multiple foci of commitment among volunteers have been largely neglected in the volunteering literature. A notable exception is a study by Valeau et al. (2013). They found that affective commitment towards the organization was negatively related to turnover intentions, yet affective commitment towards beneficiaries was not. They did not, however, assess antecedents of commitment to beneficiaries, nor did they examine its positive consequences, including whether commitment to beneficiaries is related to the time that volunteers dedicate to their service.

We address this gap by proposing that volunteers who see the impact of their work on others develop attachments to both the voluntary organization and those who benefit from their volunteer activities, and that these foci differ in their impact on work-related outcomes. Understanding the different foci of commitment is important for at least two reasons. First, it has the potential to provide a better framework for understanding the relationships among organizational commitment, commitment to beneficiaries, and volunteer outcomes. Second, it is plausible that the effect of organizational commitment on volunteer outcomes has been overstated in past research (e.g., Cuskelly and Boag 2001; Miller et al. 1990) and that part of its effect could be attributed to attachments volunteers develop with the beneficiaries of their work, aside from their attachment to the voluntary organization. Based on the principle that an individual’s bond with a target commits the person to target-relevant behaviors (e.g., Becker 1992; Meyer et al. 2006; Reichers 1985) and the prior empirical work in the paid employment context that supports it, we propose that volunteers’ commitment to their voluntary organization is related to lower turnover intentions, while volunteers’ commitment to the beneficiaries of their actions is associated with increased time spent volunteering among volunteers. In the following sections, we elaborate on these hypotheses.

The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment

Volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed have higher levels of organizational commitment because, through their volunteering, they are able to directly observe how the voluntary organization helps others and they see that the organization truly cares about those it supports. This argument is consistent with research in the paid employment context carried out by Grant et al. (2008). They found that employees who donate money to charitable causes report higher levels of commitment to their organization. They explained that the organization’s sponsorship of the charitable cause sent a signal to the donators that the organization was caring, thereby strengthening their commitment towards the organization itself (Grant et al. 2008).

A positive relationship between jobs that are designed so that incumbents perceive that they impact others and organizational commitment is also likely given that volunteers operate within the scope of their voluntary organization’s mission (Nelson et al. 1995) and are able to observe firsthand the voluntary organization’s activities. Additionally, it is the voluntary organization’s infrastructure that provides volunteers with the opportunity to improve the welfare of beneficiaries in the first place. As a result, the perception that their actions have a positive impact enables volunteers to see their voluntary organization as caring, thereby strengthening their commitment to the organization.

Moreover, commitment to the voluntary organization is positively associated with volunteers’ desire to remain volunteering for the organization. A healthy body of research supports this link in the volunteering literature (e.g., Cuskelly and Boag 2001; Miller et al. 1990; Valeau et al. 2013). In summary, we propose that volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed report higher levels of commitment to the organization, which, in turn, is negatively related to turnover intentions.

H3

Organizational commitment fully mediates the relationship between relational job design and turnover intentions.

The Mediating Role of Commitment to Beneficiaries

Our theoretical model also posits a positive relationship between relational job design and commitment to beneficiaries. Support for this link can be gleaned from research which has shown that people who help others justify their own helping behavior by believing that the receiver is attractive, likeable, and worthy of commitment (e.g., Flynn and Brockner 2003; Jecker and Landy 1969). Moreover, when individuals perceive that their role enables them to make an impact on others, they become attached to those who receive their care (Grant et al. 2008). Hence, when volunteers perceive that their roles are relationally designed, they infer that they value and like the beneficiaries, which fosters commitment to them (Bem 1972; Jecker and Landy 1969). Additionally, perceptions of beneficiary impact lend weight to volunteers’ belief that their investment in the beneficiaries was successful. This fosters a sense of closeness to the beneficiaries, which promotes feelings of commitment to them (Grant et al. 2008). We, therefore, posit that volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed have higher levels of commitment to these individuals.

Moreover, we propose that commitment to the beneficiaries of volunteering is positively associated with the dedication of time to volunteering. This is because feeling committed to the beneficiaries of one’s activities is associated with a sense of attachment and relatedness to the beneficiaries (Meyer et al. 2004). Volunteers have a need to be related to others, and through spending time on volunteering, that need becomes satiated (Deci and Ryan 1985). In summary, we hypothesize that volunteers who perceive that their roles are relationally designed are more strongly committed to those who benefit from their work and this, in turn, is associated with spending more time engaging with volunteering activities.

H4

Commitment to beneficiaries fully mediates the relationship between relational job design and time spent volunteering.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The sample was drawn from a large international aid and development agency in the United Kingdom (UK). We distributed the survey electronically to 2,500 individuals who volunteered for the organization. In the accompanying electronic message, the individuals were informed about the purpose of the study and assured that their responses would be kept anonymous. Recipients of the initial e-mail were sent a reminder two weeks later.

The response rate was 25.9 %, with 647 volunteers completing the survey. In order to obtain results with practical significance to organizations, we limited our sample to active volunteers, consistent with prior research in the volunteering context (e.g., Penner 2002; Shantz et al. 2013b). We, therefore, excluded respondents who had not volunteered in the 12 months that preceded the survey, which resulted in a usable sample of 534 volunteers. The average age of the final sample of volunteers was 56.2 years, with women accounting for 66.1 % of the sample. Approximately 27.2 % of respondents were full-time employees, 23.2 % of them worked part-time, 34.3 % were retired, and the remaining 15.3 % represented the “other” category. The respondents were volunteers and did not have any formal employment ties with the organization where the research was conducted.

Measures

Unless otherwise noted, all items were measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). Where appropriate, the language used in the scales was adapted to reflect the volunteering context of the study. Scale reliabilities are found in Table 1.

Relational Job Design

Relational job design was measured with a 4-item scale adapted from Grant et al. (2007) to suit the volunteering context. A sample item is “Through my volunteering work, I substantially improve the welfare of [the voluntary organization’s] beneficiaries.”

Organizational Commitment

Affective commitment to the organization was measured with a 6-item scale adapted from Allen and Meyer (1990). A sample item is “I feel a strong sense of belonging to [the voluntary organization].”

Commitment to Beneficiaries

Allen and Meyer (1990) and Grant et al.’s (2007) affective commitment scales were adapted to develop a 5-item commitment to beneficiaries scale that is suited to a volunteer context. A sample item is “I am strongly committed to the beneficiaries of my volunteering activities.”

Turnover Intentions

We adapted a 3-item turnover intentions scale based on Boroff and Lewin (1997) to the volunteer context. A sample item is “I am seriously considering quitting volunteering at [the voluntary organization].”

Time Spent Volunteering

To measure volunteer time, we asked participants to report (by month) the number of hours they volunteered in the preceding 12 months. The sum of these figures was used to create the volunteer time variable employed in our analyses. Volunteer time was positively skewed; in order to conduct parametric tests without violating normality assumptions, we normalized the variable by taking its log transformation (Osborne 2002).

Control Variables

We entered gender (1 = female, 0 = male), age, and working status (dummy variables for full-time, part-time, retired, and other, where we employed the “other” category as the comparison group) in all our analyses. These controls were included because two reviews of the volunteering literature showed that women and men differ in the intensity and longevity of their volunteering efforts; age and related life stages play an important role in volunteers’ attitudes and behaviors; and working status influences the time that volunteers devote to their service (Wilson 2000, 2012).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Tests of Discriminant Validity

Scale reliabilities, means and standard deviations, and correlations of the variables employed in the study are presented in Table 1.

As all measures in the present study were collected from a single source, a series of confirmatory factor analyses was conducted using AMOS 22.0 (Arbuckle 2006) to assess the potential influence of common method bias and to establish the discriminant validity of the scales. A full measurement model was initially tested, in which all indicators loaded onto their respective factors. All factors were allowed to correlate. In all measurement models, error terms were free to covary between one pair of organizational commitment items and two pairs of commitment to beneficiaries items to improve fit and help reduce bias in the estimated parameter values (Reddy 1992).

Five fit indices were calculated to determine how the model fitted the data (Hair et al. 2009). For the χ 2/df, values <2.5 indicate a good fit and values around 5.0 an acceptable fit (Arbuckle 2006). For the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis coefficient (TLI), values above .90 are recommended as an indication of good model fit (Bentler 1990; Bentler and Bonett 1980). For the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), values <.06 indicate a good model fit and values <.08 an acceptable fit (Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hu and Bentler 1998). The five-factor model showed a good model fit (χ 2 = 528; df = 140; CFI = .93; TLI = .91; RMSEA = .072; SRMR = .079). Next, sequential χ 2 difference tests were carried out. Specifically, the full measurement model was compared to eight alternative nested models as shown in Table 2. Results of the measurement model comparison revealed that the model fit of the alternative models was significantly worse compared to the full measurement model (all at p < .001). This suggests that the variables in this study are distinct.

Test of Hypotheses

We employed Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS, which uses an analytical framework based on ordinary least squares regression to estimate direct and indirect effects. This is a versatile modeling tool because it allows for the testing of multiple mediators for one dependent variable at a time. PROCESS quantifies indirect effects and uses a single inferential test to test for mediation. In addition, PROCESS employs bootstrapping when generating confidence intervals for indirect effects. This procedure is a more advanced test for mediation compared to traditional methods (Hayes 2013), such as the causal steps approach (e.g., Baron and Kenny 1986).

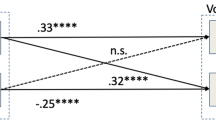

Hypothesis 1 stated that relational job design is negatively related to volunteers’ turnover intentions and Hypothesis 3 stated that commitment to the organization fully mediates this relationship. Table 3 reveals that relational job design was significantly and negatively related to turnover intentions (total effect or path c), lending support to Hypothesis 1. Moreover, relational job design was significantly related to organizational commitment (path a), which in turn was significantly and negatively related to turnover intentions (path b). The results further showed that the size of the indirect effect of relational job design on turnover intentions, transmitted through organizational commitment, was −.14. The 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval [−.2143, −.0866] did not contain 0, indicating that the effect is negative and significant. Sobel (1982) test results also showed that the indirect effect was statistically significant at the .01 level, supporting the indirect effect of relational job design on turnover intentions through organizational commitment. Results in Table 3 also reveal an additional direct effect of relational job design on turnover intentions (direct effect or path c1). The total effect of relational job design on turnover intentions can, therefore, be decomposed into a direct and an indirect effect. This implies that organizational commitment partially mediated the relationship between relational job design and turnover intentions. Hypothesis 3 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that relational job design is positively related to volunteer hours and Hypothesis 4 predicted that commitment to beneficiaries fully mediates this relationship. Results in Table 4 reveal that relational job design was significantly and positively related to volunteer time (total effect or path c). Hypothesis 2 was, therefore, supported. Moreover, relational job design was significantly related to commitment to beneficiaries (path a), which in turn was significantly related to volunteer time (path b). The results further revealed that the size of the indirect effect of relational job design on volunteer time, transmitted through commitment to beneficiaries, was .06. The indirect effect was statistically significant, as the 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval [.0154, .1043] did not contain 0. Sobel (1982) test results further confirmed that the indirect effect was statistically significant at the .01 level, supporting the indirect effect of relational job design on volunteer time through commitment to beneficiaries. Results in Table 4 also reveal an additional direct effect of relational job design on volunteer time (direct effect or path c1). The total effect of relational job design on volunteer time can, therefore, be decomposed into a direct and an indirect effect. This implies that commitment to beneficiaries partially mediated the relationship between relational job design and time spent volunteering, lending partial support to Hypothesis 4.

Although not formally hypothesized, we also examined whether commitment to the organization mediated the relationship between relational job design and time spent volunteering, and whether commitment to beneficiaries mediated the relationship between relational job design and turnover intentions, thereby testing whether the two mediators are interchangeable.

We tested this in two ways. We first ran two mediation models where we individually tested whether we could switch the two mediators without considerably altering the results. We found that commitment to the organization did not mediate the link between relational job design and time spent volunteering, as the indirect effect was not statistically significant (size of the indirect effect = .03; 95 % CI [−.0131, .0773]). Similarly, we found that the indirect effect of volunteers’ perceived relational job design on turnover intentions, transmitted through commitment to beneficiaries, was likewise not statistically significant (size of the indirect effect = −.01; 95 % CI [−.0522, .0400]). These analyses illustrated that, when considered individually, the two mediators were not interchangeable.

Second, we included both foci of commitment variables into the model simultaneously for each dependent variable (i.e., parallel mediation models). The results showed that, as hypothesized, only commitment to beneficiaries mediated the relationship between relational job design and volunteer time, as the indirect effect through commitment to the organization was not statistically significant [size of the indirect effect = .01; 95 % CI (−.0419, .0626)]. The indirect effect of relational job design on turnover intentions, transmitted through commitment to beneficiaries, was statistically significant [size of the indirect effect = .06; 95 % CI (.0087, .1060)]; however, the effect was in the opposite direction than the indirect effect transmitted through organizational commitment and opposite of what one would expect. These results, while not formally hypothesized, add support to our findings, as they further validate our decision to distinguish between the two mediators and propose two different paths from relational job design to volunteering outcomes.

Discussion

The present study revealed a positive relationship between volunteers’ perceived relational job design and (1) intention to remain volunteering with the voluntary organization and (2) the time that volunteers dedicate to their volunteering work. We uncovered two mechanisms that explain how the positive consequences of relational job design unfold. Specifically, we demonstrated that relational job design is associated with volunteer retention due to volunteers’ commitment to the organization. Moreover, relational job design is positively associated with volunteers’ devotion of time to their service because they are committed to the beneficiaries of their volunteer work.

Our theoretical model suggested that the relationships between relational job design, turnover intentions and time spent volunteering were fully mediated by the two foci of commitment. Our results showed that although the inclusion of the mediators reduced the amount of variance in the outcomes explained by the independent variable, it did not render it insignificant. This suggests that, while commitment is one key mechanism that explains the relationships between relational job design and volunteer retention and time spent volunteering, there are other, yet unearthed mediators, which operate in addition to commitment to further explain the underlying processes of the relationships between relational job design and the outcomes under study (Shrout and Bolger 2002). It is plausible that in addition to developing a sense of commitment towards an external target as our model predicts (i.e., the organization and the beneficiaries), relational job design may trigger additional mediational processes such as affecting how volunteers think and feel about themselves. For example, volunteers who see the impact of their work on others may develop feelings of self-esteem (Yogev and Ronen 1982) and confidence in themselves and their work (Yates and Youniss 1996), which motivates them to dedicate more time to their volunteering service. Finding additional explanations for the mechanisms between relational job design, volunteer time and retention is a fruitful avenue for future research.

The present study makes several theoretical and practical contributions to the volunteering literature. For instance, the present study shows that relational job design is an important correlate of volunteer attitudes and behavior. Although the field is rich with research on individual factors that motivate individuals to initiate volunteering, we know less about factors that sustain volunteering. While individual difference factors may shed some light on what sustains volunteering, factors associated with the volunteering environment, such as the design of jobs, are likely to be more promising. Indeed, Hustinx et al. (2010) argued that the voluntary organizational environment is more salient for attitudes and behaviors than individual differences.

Our theoretical model, along with our findings, extends current knowledge in the volunteering literature by showing that the relational architecture of jobs provides volunteers with a sense of instrumentality. We advance relational job design (Grant 2007) and expectancy theories (Vroom 1964) by adopting their principles to the volunteering context, and theorizing that volunteers are motivated to remain volunteering for the organization and dedicate time to their service because they see a link between their actions and the outcomes of their actions. Specifically, our model suggests that when volunteers see that their work has a positive impact on beneficiaries, they further engage in behaviors to make a positive difference on their beneficiaries, as they value the outcome of these behaviors (i.e., increased welfare of beneficiaries). Hence, the present study advances theory on volunteering by demonstrating that factors within the control of organizations (e.g., job design) are an important source of volunteer motivation.

We make an additional contribution to both the volunteering literature and the literature on multiple foci of commitment by uncovering two distinct foci of commitment that explain the links between relational job design and turnover intentions and time spent volunteering, respectively. Volunteers’ commitment to the organization was better able to explain the link between relational job design and turnover intentions (an organization-relevant outcome), while volunteers’ commitment to those who benefit from their work was better suited to explain the link between relational job design and the time that volunteers devote to their service (a beneficiary-relevant outcome). This has implications for the interpretation of past research that has found that commitment to the voluntary organization is associated with important outcomes (e.g., Cuskelly and Boag 2001; Miller et al. 1990; Preston and Brown 2004), as it is possible that the effect is overstated because it does not take into consideration volunteers’ commitment to the beneficiaries of their work.

These findings contribute to the multiple foci of commitment literature, as they illustrate the value of matching the foci of the variables under study (Becker 1992) and advance commitment to the beneficiaries of volunteering as an important focus of commitment. Our findings are in fact consistent with those of Valeau et al. (2013), who found that, among volunteers, commitment to the organization was significantly related to turnover intentions, yet commitment to beneficiaries was not. However, we go beyond the Valeau et al. (2013) study by showing that commitment to beneficiaries is in fact important, but more so for its association with time spent volunteering, rather than intention to remain volunteering for the voluntary organization.

Finally, our study complements recent findings by Bennett and Barkensjo (2005). Their study focused on negative contact experiences with beneficiaries and demonstrated that unpleasant experiences had an overall negative influence on volunteers’ organizational commitment. In contrast, our study demonstrates the positive effects that can be generated for volunteers who are able to connect with the beneficiaries of their work in a positive way. Both studies highlight beneficiary contact as a concept which warrants further attention in the volunteering literature.

In addition to these theoretical insights, the present study has implications for the practice of volunteer management. Due to the important role that perceived relational job design plays in relation to positive volunteer attitudes and behavior, voluntary organizations should focus their efforts on showing their volunteers how their work impacts the welfare of their beneficiaries. In some volunteer roles, the work is designed such that it is relatively straightforward for volunteers to directly see the impact that they make on beneficiaries. For instance, volunteers whose roles involve helping children read literature see the immediate impact of their volunteer work on a child’s reading progression and love of the written word. However, in other contexts, volunteers may hold roles where they are less well-positioned to see how their work impacts others. In the present study, our sample includes volunteers located in the UK who dedicate time, while residing in the UK, to helping individuals in other parts of the world, through activities such as fundraising, selling ‘fair trade’ crafts, and generating enthusiasm from the public through public speaking engagements. For these volunteers, their perception of the impact they make on beneficiaries may be highly varied, given that they are geographically disconnected from the people who benefit from their work. For such volunteers, a straightforward way of increasing perceptions of relational job design is providing information about beneficiaries via internal marketing techniques, such as an electronic newsletter (Bennett and Barkensjo 2005), or other means of communication.

Before we administered the survey to our participants, we ran a number of focus groups with volunteers and paid staff to understand the context of the voluntary organization. During these informal discussions, we found that volunteers (and paid staff) who had traveled to countries (such as those in Africa) where their volunteering efforts were directed, were strongly committed both to the organization and to those whom they benefit. Hence, one way to design jobs to include a relational element is to sponsor volunteers, or help volunteers find funding to travel to parts of the world where their volunteering efforts are most felt.

Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The cross-sectional nature of our study limits our ability to make causality claims. However, we used a strong theoretical foundation to establish temporal precedence, obtained evidence of concomitant variation, and attempted to eliminate spurious covariation by including control variables in the two mediation models (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Nevertheless, replicating our study using longitudinal data would help alleviate this concern and provide more conclusive results. Furthermore, as the sample in our study consisted mostly of older volunteers, future studies should employ a sample more demographically similar to the volunteer population and thereby expand the generalizability of our findings. An additional limitation of the present study is that all the variables used in the analyses were derived from self-report measures, raising concerns regarding common method bias. In order to alleviate this concern, we employed established scales in our study, guaranteed anonymity to our respondents, and provided participants with a clear explanation of study procedures (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Moreover, our analysis revealed that common method bias was not a particular concern and our study variables were distinct from one another.

Our results may lead to future research on the impact of relational job design on outcomes of interest to voluntary organizations. To develop this theoretical area, future research should consider contextual factors that moderate the relationship between relational job design and relevant outcomes. For example, does the relationship depend on the type of volunteer task? Relational job design may be relatively more impactful in roles where the beneficiaries are people (e.g., volunteers who work with the elderly, young mothers, etc.), compared to roles in which those who benefit are either not people or the people who benefit are more psychologically distant from the actual activity (e.g., bird watchers in an ecological setting, quality assurance of public records, etc.). Volunteer roles that allow the incumbents to interact face-to-face with the beneficiaries likely strengthen the relationship between relational job design and outcomes.

Future research should also explore the potential negative consequences of increasing relational job design. Some commentators have suggested that volunteers overestimate their effects on beneficiaries and voluntary organizations should assist volunteers in managing their expectations (Wuthnow 1995). Research on realistic job previews suggests that maintaining expectations (of paid employees) at the initial recruitment stage is imperative for increasing retention and positive job attitudes (e.g., Wanous 1978). Future research should, therefore, examine volunteers’ expectations with regard to their impact on beneficiaries, and whether designing jobs to increase those perceptions may, in some cases, backfire.

The idea that voluntary organizations’ actions may lead to negative consequences throws into question whether human resource management practices, such as job design, training, and performance appraisals, are positively appraised by volunteers, or whether these practices are viewed as bureaucratic hurdles that volunteers must overcome. As noted by Studer and von Schnurbein (2013), research on the effectiveness of human resource management practices has only begun; hence, future research should examine the positive and negative consequences of such activities for the retention, performance, and wellbeing of volunteers.

Conclusion

We developed and tested a theoretical model that explored the relationship between perceptions of relational job design and turnover intentions and time spent volunteering. The results showed that volunteers have lower intentions to leave the organization because they are more strongly committed to that organization, and are more willing to devote more time to their volunteering efforts because they are more strongly committed to the beneficiaries of their actions. At a time when governments increasingly rely on voluntary organizations and their volunteers to fill gaps in services to individuals and communities, promoting active and prolonged volunteer service is more important than ever. With our findings, we highlight important new concepts and pathways that organizations can target and thereby more effectively manage their volunteers.

References

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). AMOS (Version 7.0) [computer software]. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Becker, T. E. (1992). Foci and bases of commitment: Are they distinctions worth making? Academy of Management Journal, 35(1), 232–244.

Becker, T. E., Billings, R. S., Eveleth, D. M., & Gilbert, N. L. (1996). Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 464–482.

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–62). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bennett, R., & Barkensjo, A. (2005). Internal marketing, negative experiences, and volunteers’ commitment to providing high-quality services in a UK helping and caring charitable organization. Voluntas: International Journal of Volunteer and Nonprofit Organizations, 16(3), 251–274.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606.

Boroff, K. E., & Lewin, D. (1997). Loyalty, voice, and intent to exit a union firm: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51(1), 50–63.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Carley, K. (1992). Organizational learning and personnel turnover. Organization Science, 3(1), 20–46.

Cheng, B.-S., Jiang, D.-Y., & Riley, J. H. (2003). Organizational commitment, supervisory commitment, and employee outcomes in the Chinese context: Proximal hypothesis or global hypothesis? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(3), 313–334.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., & Stukas, A. A. (1996). Volunteers’ motivations: Findings from a national survey. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25(4), 485–505.

Cnaan, R. A., & Cascio, T. A. (1999). Performance and commitment: Issues in management of volunteers in human service organizations. Journal of Social Service Research, 24(3–4), 1–37.

Cordery, J. L., & Parker, S. K. (2008). Work organization. In P. Boxall, J. Purcell, & P. Wright (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of human resource management (pp. 187–210). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Craig-Lees, M., Harris, J., & Lau, W. (2008). The role of dispositional, organizational and situational variables in volunteering. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 19(2), 1–24.

Cuskelly, G., & Boag, A. (2001). Organisational commitment as a predictor of committee member turnover among volunteer sport administrators: Results of a time-lagged study. Sport Management Review, 4(1), 65–86.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Co.

Ellemers, N., de Gilder, D., & van den Heuvel, H. (1998). Career-oriented versus team-oriented commitment and behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(5), 717–730.

Flynn, F. J., & Brockner, J. (2003). It’s different to give than to receive: Predictors of givers’ and receivers’ reactions to favor exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1034–1045.

Gordon, M. E., & Ladd, R. T. (1990). Dual allegiance: Renewal, reconsideration, and recantation. Personnel Psychology, 43(1), 37–69.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 393–417.

Grant, A. M. (2008). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 108–124.

Grant, A. M. (2012). Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 458–476.

Grant, A. M., Campbell, E. M., Chen, G., Cottone, K., Lapedis, D., & Lee, K. (2007). Impact and the art of motivation maintenance: The effects of contact with beneficiaries on persistence behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103(1), 53–67.

Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., & Rosso, B. D. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 898–918.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modelling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Bulletin, 3(4), 424–453.

Hustinx, L. (2010). I quit, therefore I am? Volunteer turnover and the politics of self-actualization. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(2), 236–255.

Hustinx, L., Handy, F., Cnaan, R. A., Brudney, J. L., Pessi, A. B., & Yamauchi, N. (2010). Social and cultural origins of motivations to volunteer: A comparison of university students in six countries. International Sociology, 25(3), 349–382.

Jecker, J., & Landy, D. (1969). Liking a person as a function of doing him a favour. Human Relations, 22(4), 371–378.

Lindenmeier, J. (2008). Promoting volunteerism: Effects of self-efficacy, advertisement-induced emotional arousal, perceived costs of volunteering, and message framing. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 19(1), 43–65.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551.

Meyer, J. P., Becker, T. E., & Van Dick, R. (2006). Social identities and commitments at work: Toward an integrative model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 665–683.

Meyer, J. P., Becker, T. E., & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 991–1007.

Miller, L. E., Powell, G. N., & Seltzer, J. (1990). Determinants of turnover among volunteers. Human Relations, 43(9), 901–917.

Millette, V., & Gagne, M. (2008). Designing volunteers’ tasks to maximize motivation, satisfaction and performance: The impact of job characteristics on volunteer engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 32(1), 11–22.

Nelson, H. W., Pratt, C. C., Carpenter, C. E., & Walter, K. L. (1995). Factors affecting volunteer long-term care ombudsman organizational commitment and burnout. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 24(3), 213–233.

Okun, M. A., & Schultz, A. (2003). Age and motives for volunteering: Testing hypotheses derived from socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 231–239.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671–686.

Osborne, J. W. (2002). Notes on the use of data transformations. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 8(6). Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=8andn=6.

Penner, L. A. (2002). Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 447–467.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 13–54). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Preston, J. B., & Brown, W. A. (2004). Commitment and performance of nonprofit board members. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 15(2), 221–238.

Reddy, S. K. (1992). Effects of ignoring correlated measurement error in structural equation models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(3), 549–570.

Reichers, A. E. (1985). A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 465–476.

Reichers, A. E. (1986). Conflict and organizational commitments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 508–514.

Shantz, A., Alfes, K., Truss, C., & Soane, E. (2013a). The role of employee engagement in the relationship between job design and task performance, citizenship and deviant behaviours. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(13), 2608–2627.

Shantz, A., Saksida, T., & Alfes, K. (2013b). Dedicating time to volunteering: Values, engagement, and commitment to beneficiaries. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 63(4), 671–697.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Siders, M. A., George, G., & Dharwadkar, R. (2001). The relationship of internal and external commitment foci to objective job performance measures. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 570–579.

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (2008). Volunteerism: Social issues perspectives and social policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 2(1), 1–36.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhardt (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Studer, S., & von Schnurbein, G. (2013). Organizational factors affecting volunteers: A literature review on volunteer coordination. Voluntas: International Journal of Volunteer and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(2), 403–440.

Valeau, P., Mignonac, K., Vandenberghe, C., & Gatignon Turnau, A. L. (2013). A study of the relationships between volunteers’ commitments to organizations and beneficiaries and turnover intentions. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 45(2), 85–95.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York, NY: Wiley.

Wanous, J. P. (1978). Realistic job previews: Can a procedure to reduce turnover also influence the relationship between abilities and performance? Personnel Psychology, 31(2), 249–258.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240.

Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(2), 176–212.

Wuthnow, R. (1995). Learning to care: Elementary kindness in an age of indifference. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Yates, M., & Youniss, J. (1996). A developmental perspective on community service in adolescence. Social Development, 5, 85–111.

Yogev, A., & Ronen, R. (1982). Cross-age tutoring: Effects on tutors’ attributes. Journal of Educational Research, 75(5), 261–268.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alfes, K., Shantz, A. & Saksida, T. Committed to Whom? Unraveling How Relational Job Design Influences Volunteers’ Turnover Intentions and Time Spent Volunteering. Voluntas 26, 2479–2499 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9526-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9526-2