Abstract

Teacher–student trust is associated with the social and emotional development of students, their school connectedness and engagement, and their academic achievement. However, few studies have examined how trust develops between teachers and students in ninth grade, a critical year in high school for students to start off on-track. Even less research has examined how teacher–student trust develops from the perspective of students to help identify specific teacher classroom practices that are effective at doing so, particularly at the start of the school year when students’ relationships and connections to high school are just beginning to take shape. Drawing on data from a longitudinal, qualitative study of ninth-grade teacher–student relationships in one neighborhood public high school in Chicago, this study highlights three critical classroom practices that appear particularly effective for helping to build trusting teacher–student relationships during the first 10 weeks of high school. Highlighting the perspectives and insights of ninth grade students, this analysis finds that (1) the priority that teachers place on specific classroom practices, and (2) the timing of when these practices are used by teachers, are both critical in establishing teacher–student trust—an essential ingredient in helping ninth grade students gain important social and school connections during their transition to high school. By highlighting the voices of ninth grade youth, this study provides valuable insights for educators aiming to use specific classroom-based practices that are essential for helping ninth grade students make valuable school connections and get on-track right from the start of the year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition to high school has been found to be challenging for students in urban public high schools. However, research that has examined the specific practices used by classroom teachers to enhance students’ school connectedness has highlighted that teachers who actively work to build trusting relationships with students are more likely to positively impact students’ social and emotional development, especially for those most at risk for being disconnected from high school. Drawing on analysis of data from a year-long qualitative study that examined how ninth grade teacher–student relationships develop in one public neighborhood high school in Chicago this study highlights three critical teacher classroom practices identified by ninth grade students as most effective for building teacher–student trust, an essential ingredient for strengthening students’ school connectedness during an important school transition.

The Importance of Ninth Grade, School Connectedness, and Teacher–Student Trust

Ninth grade students are at risk for a range of social, emotional, and academic challenges that can reduce their chances of graduating high school. Compared to their elementary school peers, ninth grade students have been found to be more likely to report lower self-perceptions of their abilities as students, to express increased negative attitudes about school, and to experience declines in attendance and course performance during their first year of high school (Allensworth and Easton 2005, 2007; Felner 1982; French et al. 2000; Gwynne et al. 2012; Quint et al. 1999; Roderick 1993; Seidman and Allen 1994; Schiller 1999; Weiss 2001). The challenges students experience in ninth grade also appear to be common in early adolescence. Benner and Graham (2009), found that negative trends in students’ school engagement and academic performance begin as early as seventh grade and continue steadily throughout tenth grade across a variety of schools serving students from diverse racial, ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds. Low-income students attending urban, public high schools, however, appear to be at particularly high risk for challenges in ninth grade. In the Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the school district where the high school in this study took place, ninth grade students experience lower attendance, increased disciplinary infractions, and declines in academic performance compared to their elementary school peers (Allensworth and Easton 2005, 2007; Gwynne et al. 2012; Roderick et al. 2014). These challenges can also have long-term implications for students’ chances of graduating high school. During 2011–2012, the year this study took place, 27% of the 21,227 ninth grade students (N = 5731) in CPS were off-track to graduate high school because they failed one or more core academic classes (English, math, science, and social studies), leaving them without the requisite core course credits to keep them on-track to graduate (Allensworth and Easton 2005; Chicago Public Schools 2014). Moreover, off-track freshman in CPS have been found to only have a 25% chance of graduating high school within 5 years (Allensworth and Easton 2005, 2007; Gwynne et al. 2012). In light of these challenges, it is critical to closely examine what classroom practices can help students develop essential connections to their new high school, connections that can greatly increase their chances of staying on-track during this important school transition.

Research on school connectedness and adolescent development highlights that the connections youth develop with adults in schools can be critical to ensuring their healthy development and school success (Catalano et al. 2004; Libbey 2004; Pianta 1999). Bond et al. (2007) define connectedness as, “a sense of secure emotional connection to key individuals [that] provide a base for psychological and social development”. As well, high levels of school connectedness were significantly associated with better mental health and academic outcomes for adolescents, such as lower levels of anxiety/depression symptoms and graduating high school (Bond et al. 2007). Strengthening ninth grade students’ connectedness to their new high school can be difficult, however, as students often must develop new adult and peer relationships, as well as navigate new and sometimes unfamiliar academic and behavioral norms and expectations.

Studies of school connectedness often focus on the role of teacher–student relationships and their role in helping students successfully begin high school. Roorda et al. (2011) meta-analysis of affective teacher–student relationships found that the detrimental effects of negative teacher–student relationships are stronger in secondary school than elementary school but that positive affective teacher–student relationships are associated with higher school engagement and academic achievement. Essential to developing positive affective teacher–student relationships is the important process of building trust. Research on teacher–student trust in schools is closely associated with an array of important school outcomes (Bryk and Schneider 2002). For example, in CPS, Allensworth and Easton (2007) found teacher–student trust to be the most predictive school climate variable associated with ninth grade attendance, course failure rates, and course grades. Baker et al. (2008) found that teacher–student relationships characterized by warmth, trust, and low degrees of conflict, were associated with positive school outcomes for students who experience internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Additionally, Murray (2009) found that teacher–student trust was strongly associated with positive school adjustment among low-income early adolescent students of color.

Trusting relationships between teachers and students develop over time. The way in which students initially perceive whether their teachers appear trustworthy, as well as how this perception evolves over time, are both critical to understanding what classroom practices facilitate the development of teacher–student trust. Phillippo (2012), in a qualitative study of advisory classroom in three Chicago public high schools, developed a two-stage model of the process by which teacher student relationships develop. According to Phillippo, how students initially observed teachers in their interactions with students in the classroom, how they designed their classroom activities, and how they used classroom discipline approaches over time determined how teachers were perceived as being trustworthy and culturally responsive. Specifically, she found that if teachers initiated specific classroom practices and behaviors at the start of the year, that they were likely to be perceived by students as trustworthy and culturally responsive by the end of the year (Phillippo 2012). Thus, by closely examining how teacher–student trust initially emerges in ninth grade classrooms, as well as how it unfolds over time, valuable insights can be gained into which classroom practices can help ninth grade students become more strongly connected to their new high school.

Previous studies that have examined teacher classroom practices that enhance positive teacher–student relationships help to frame which practices appear particularly effective. In a meta-analysis of teacher–student relationships Cornelius-White (2007) highlights that teacher expressions of nondirectivity, empathy, warmth, and encouragement of higher order thinking were highly correlated with positive cognitive and affective behavioral outcomes for students. Avoiding inappropriate and negative behaviors were also identified as essential for teachers to build trust with students. Gregory and Ripski (2008) found that high school teachers who avoided incompetence, offensiveness, and indolence were more likely to develop trust with their students and, in turn, reduced student discipline referrals, teacher stress, and lost instructional time. In a report of the five essential factors found to be effective for learning in CPS, measures of teacher–student trust were defined by teachers who were perceived by students to be effective in keeping their promises, helping students feel safe and comfortable at school, who listened to their ideas, and who treated them with respect (Chicago Consortium on School Research 2016). As well, Muller (2001) found that students who perceive that their teachers care for their wellbeing, expect them to find success, listen to them, and praise them for their efforts are more likely to see improvements in academic achievement among their students. As well, teachers who use regular feedback and revision cycles through writing assignments to establish systems of communication with students (Lee and Schallart 2008), those who vocally communicate with assertiveness and responsiveness (Van Petegem et al. 2007), and those who show enthusiasm and variation in methods when teaching (Wooten and McCroskey 1996) have all been shown to enhance student well-being and build teacher–student trust. Taken together, research on teacher–student trust appears to show that right from the start of the year teachers can take important steps toward building trust with their ninth grade students if they: (1) consistently demonstrate assertive, enthusiastic, warm, and respectful communication, (2) set clear, high expectations for student success, (3) listen to students to identify and draw out their individual strengths and needs, (4) embrace and incorporate students’ cultural backgrounds into the classroom, (5) are responsive to students’ affective concerns and academic needs, (6) create classroom systems that facilitate regular face-to-face and written feedback and communication between teachers and students, and (7) avoid negative interactions with students such as incompetence, offensiveness, and indolence. In light of these essential practices, and given the importance of helping to keep students connected to their new school and on-track from the beginning of ninth grade, this study closely examines specific classroom practices used by ninth grade teachers right from the start of the year and uses student perspectives on teacher classroom practices to provide valuable insight into which practices are critical for building teacher–student trust and strengthening students’ school connectedness during their transition to high school.

Method

This study is guided by two research questions: (1) What ninth grade teacher classroom practices do students perceive as effective for building teacher–student trust? (2) What are the implications of these practices on how students experience their transition to high school?

Study Design and Setting

Using a longitudinal, qualitative design, this study followed a cohort of eight (8) ninth grade teachers and sixteen (16) ninth grade students throughout one academic year, from June 2011 through July 2012 in one neighborhood public school in Chicago—Anderson High School. (To ensure the anonymity of the school, teachers, and students, all names have been changed to pseudonyms.) Semi-structured interviews with ninth grade teachers and students were conducted, ninth grade classrooms were observed, and student attendance and academic performance records were obtained at the end of the first and second semester of ninth grade. This study analyzes data gathered from the 73 semi-structured interviews that were conducted with ninth grade student interviews throughout the school year.

Ninth grade classrooms were the central settings used to examine teachers’ classroom practices. During the 2011–2012 school year, 1620 students attended Anderson a high school that was comprised of ethnically diverse students (65% of students identified as Hispanic, 12% as Asian American, 11% as African American, 9% as White, and 2% as Other) from largely low income (91% of students participated in the Federal free lunch program) households (Chicago Public Schools 2012). As well, 16% received special education services and 10% were designated as English Language Learners (ELL). Anderson High School was chosen for this study because its organizational structure and student demographic characteristics mirrored the majority of public neighborhood high schools in CPS. In the district, schools designated as “neighborhood high schools” represent the largest category of high schools that students attended during the 2010–2011 academic year (55,239 students, or 46.8%, of all CPS high school students) (Chicago Public Schools 2011). Thus, Anderson was similar to the majority of neighborhood high schools in CPS and provided a unique opportunity to explore the range of classroom practices that can shape how ninth grade teacher–student relationships develop.

Participants

A theoretical sampling strategy was used to select study participants (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss 1987; Strauss and Corbin 1990; Mason 2002; Creswell 1998). Theoretical sampling aims to identify groups in a study tied to particular, theoretically relevant, phenomena that enable further subsequent sampling and detailed coding of categories toward the development of themes used to tell an integrated story of the phenomenon of interest (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss 1987; Mason 2002; Creswell 1998). In sampling a high school with a similar demographic distribution of students to those in the district, theoretically informed decisions were made to recruit students from Anderson’s two primary neighborhood feeder elementary schools, as well as its ninth grade summer preparation program, prior to the start of the 2011–2012 academic year. In total, 33 parents provided consent for their incoming ninth grade students (eight boys and twenty-five girls) to participate in the study; 21 of these students were ultimately identified as potential student interview subjects. To be selected as a potential interview subject, each student was enrolled in a core academic class and shared the same class period with at least one other student who consented to participate in the study during the same class period. These pairings enabled the researcher to effectively triangulate the perceptions of effective teacher practices in the same classroom with multiple students in the same class. Because ninth grade academic performance in these four academic areas has been found to be highly predictive of future drop-out and graduation rates in CPS (Allensworth and Easton 2005), examining teachers’ practices in these core subjects classrooms was vital for understanding how ninth grade students experienced their first year of high school. Ultimately, an ethnically diverse sample of sixteen ninth grade students were selected and interviewed (five boys and eleven girls). Of these sixteen students, all but one were first or second generation immigrants and came from eight different countries across Central and South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Data Sources and Analysis

The larger study of ninth grade teacher–student relationships drew on four data sources: (1) semi-structured teacher interviews, (2) semi-structured student interviews, (3) classroom observations, and (4) student attendance and grade records. For this paper, only student interviews were analyzed. Ninth grade student participants were each scheduled for interviews at five different time points over the course of the academic year: (1) during July and August prior to the start of the school year, (2) at week five of semester one, (3) at week ten of semester one, (4) at the end of semester one, and (5) at the end of semester two. A total of 73 student interviews were completed over the course of this yearlong study.

In keeping with a grounded theory method, student and teacher interview protocols were developed for the first round of summer interviews. Based on the themes that emerged during these interviews, questions relevant to the study’s research questions were then developed for each subsequent round of interviews. This grounded, theoretically-informed and iterative approach to data gathering and analysis enabled the researcher to continuously focus on the central questions of study while also remaining open and flexible to consider novel themes that were emerging throughout the data gathering phase (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss 1987; Strauss and Corbin 1990; Creswell 1998). Sample interview questions for each round of interviews are provided in Table 1.

After data gathering was complete, broad themes relevant to the study’s research questions were coded using an open-coding system. Axial coding was then used to develop subcategories of themes and determine their relationship to the themes developed during open coding (Strauss and Corbin 1990; Creswell 1998). Additionally, to triangulate the findings of this research, the author’s research colleagues read sample transcripts and provided feedback on analysis and various manuscripts and presentations completed for this study. Through this analysis, a series of key themes were identified, highlighting valuable insights into the teacher classroom practices that students identified as most effective in building teacher–student trust and enhancing students’ school connectedness in ninth grade.

Results

Analysis of first round interviews revealed that prior to starting high school student participants experienced specific worries about high school as well as concrete hopes they expected their teachers would help assuage early in the school year. Once the year began, analysis of student interviews in the first 10 weeks revealed themes regarding the priority and use of three specific classroom practices used by teachers that initially signaled to students at the start of the school year that they could be trusted to help assuage their worries and support their hopes and goals for the future. By year’s end, interviews with student participants further underscored the importance of these three critical classroom practices right from the start of the year, and further reinforced their impact to the end of the school year. Together, these critical classroom practices provide a valuable roadmap for educators seeking to identify and affirm effective approaches for effectively building teacher–student trust and strengthening students’ school connectedness in the face of the inevitable challenges of ninth grade.

Student Worries and Hopes About High School

During the first round of interviews, in July and August before the school year began, three themes emerged related to the worries ninth grade students had about starting high school: (1) navigating the first day of school and finding answers to questions about Anderson High School, (2) developing new peer and teacher relationships, and (3) seeking and receiving social, emotional, and academic supports from high school teachers. Together, these worries painted a clear picture of what students feared they would find most challenging in ninth grade. As well, these themes signaled the hopes students had for their teachers in helping provide them support in the year ahead.

Worries About High School

Worried about her nerves and navigating many of the unknowns of high school on the first day, Sabrina commented, “I’m going to get lost on my first day. I’m not going to be able to open my locker, I don’t know. I’m probably gonna wake up late. I’m gonna be too nervous.” Diana echoed similar worries, and was certain she’d be shy when initially getting to know her new classmates and teachers. “The first day of school is going to be…bad…I’m going to get lost and then be shy…I have to wait for a couple weeks to pass and [get to] know each other, and that’s when I start talking.” Sabrina agreed, and expressed worries about avoiding peers that would make her first year difficult. “I don’t want to get into no drama,” she said. Lastly, Diana specifically worried about being academically successful, and what it meant for her future. “If I have good grades, and for sophomore and all the other ones, it could take me to a good college,” Thus, student worries ranged from genuine concerns about the unknowns of high school, the peer and academic pressures to start new, pro-social relationships that could facilitate academic success, and the exciting possibility that ninth grade represented a fresh start toward their future.

Hopes for High School

To overcome their worries, student participants also overwhelmingly indicated in their first round interviews that they hoped their teachers would be supportive and attentive to the individual needs of students, not just the academic goals and expectations they knew would be demanded of them in high school. Maricela hoped her ninth grade teachers would care less about academic work at the beginning of the year. “I hope they’re gonna be cool…not like, uptight,” she said emphatically, “really give a lot of focus on students…[not] just go on with work…focus on the students!” AJ agreed, highlighting how important his initial perceptions of his teachers would be in determining whether he believed he could trust them to help him find success in ninth grade.

The way the teacher is behaving on the first few days, if she wants to know a lot more information about us and get to know us better…it’s going to be a good class. But if there’s one where we’re just doing some normal activities, they don’t want to get to know us a lot…it establishes a [different] relationship between the students and the teachers …When [we] have teachers who really know us well and we’ve believed that are really good, and want to be our friends, the students, they’re more tempted to do more of the work and not be so loud and disrupt the class all the time…If you’re in a class where it’s all boring and the teacher doesn’t try to help you out, you’re basically not going to do very good. But if you’re in one where you’re more comfortable…you’re going to get through it.

Thus, as the school year began, students like Maricela and AJ made it clear that their initial perceptions of their teachers’ classroom interactions, behaviors, and practices would signal whether they knew what their ninth grade students most worried and hoped for at the start of their first year of high school. And in their first round interviews, while student worries ranged from navigating their new school building, to establishing new peer relationships, to meeting the new academic demands and stakes before them, despite their worries, students set out in hopes of finding both peers and teachers who would share in and support their goals from the very beginning of the school year.

Right from the Start: Critical Classroom Practices for Building Teacher–Student Trust the First 10 Weeks of High School

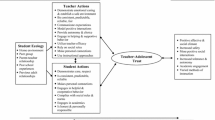

During interviews the first 10 weeks of the school year, students described how quickly they began to assess which teachers they perceived could be trusted to help them address their worries, make important school connections in ninth grade, and reach for their hopes and goals. Analysis of interviews conducted at the fifth and tenth weeks of the school year revealed clear themes related to the teacher classroom practices that students perceived as most effective for building teacher–student trust and helping students establish valuable connections to their new high school at the start of the year. Of particular note was the timing and sequence of the classroom interactions, behaviors, and practices used by teachers which students perceived as illustrative of their teachers’ priorities in the first 10 weeks. Specifically, students highlighted that teachers who: (1) showed flexibility, understanding, and patience with inconsistent student classroom behaviors, (2) led classroom activities and developed classroom norms and expectations that strengthened classroom teacher and student relationships, and (3) frequently used classroom conferencing to build rapport, assess and monitor learning, open lines of communication, and differentiate instruction, were all quickly perceived by students as teachers who could be trusted right from the start of the year to help them make the essential school connections they were seeking at the beginning of high school. Moreover, these three critical classroom practices helped students find the footing and guidance they needed to help them envision how to successfully navigate the challenges they may face in the road ahead.

Show Flexibility, Understanding, and Patience with Inconsistent Student Classroom Behaviors

The first theme that students described in determining whether teachers were perceived as trustworthy right from the start of the year or not related to how clearly teachers demonstrated flexibility, understanding, and patience as a top priority in their classroom practice. To students, teachers who demonstrated a depth of ability to demonstrate these practices in their classrooms quickly addressed many of the immediate worries and hopes they had expressed just before they began high school. Because many worried about how they would connect with the many new and different teachers, peers, and school in their new high school, those teachers who explicitly demonstrated flexibility, understanding, and patience with inconsistent student classroom behaviors during the first days of high school signaled that they understood that students would be unsure of themselves in their interactions with their peers and teachers, particularly at the start of the year, when they were just beginning to learn the new norms and expectations of high school. Alex, for example, who explained that he had had a reputation in elementary school of getting negative attention from teachers for his distracted and disruptive behavior, highlighted how Ms. Talama, his ninth grade Writing and English teacher, was particularly effective at showing flexibility, understanding, and patience with her students right from the start of the year. Specifically, she did so by expressing kindness, patience, and forgiveness by giving him multiple opportunities to make mistakes and find success. “In her class, it’s not boring, I actually want to go to her class…if you’re goofing off she won’t come talk to you, yell, and get you [angry], she’ll ask you nicely to stop. And then if you keep goofing off she’d tell you to stay outside until you’re acting better…she’s nice to me and she cares about what grades I get in the class.” Thus, teachers who explicitly showed that building trusting relationships with students was expressed through showing flexibility, understanding, and patience with inconsistent student classroom behaviors signaled to students that they genuinely understood the challenges students were facing in their transition and that they could be counted on to help them along the way.

Lead Classroom Activities and Develop Norms and Expectations That Strengthen Teacher and Student Relationships

Analysis of student interviews during the first 10 weeks also revealed a second theme related to the classroom practices used by teachers critical for helping to build trusting ninth grade teacher–student relationships. Specifically, students highlighted the importance of teachers leading classroom activities that that were designed to strengthen classroom teacher and peer relationships as well those that explicitly sought to develop classroom norms and expectations for strengthening these relationships. Early in the school year, students described feeling more comfortable interacting with and getting to know their peers and teachers, as well as participating in classroom discussions, when their teachers actively led and organized class activities that helped set norms and expectations for relational interactions of the classroom. During their ten-week interviews, many students quickly identified Ms. Devin, the ninth grade environmental science teacher, as particularly effective in leading activities that strengthened relationships in the classroom. Tiffany described how Ms. Devin made it a priority to know each student’s name on the first day of class, as well as how Ms. Devin used specific activities to help students interact with and learn about one another during the first weeks of the year. Tiffany described the impact this had on students’ participation and self-confidence at the start of the year:

Well, first she got us to talk…the first week we were all shy, but then the next weeks we started doing some activities, like playing games, so we got to meet like the people and then the next day we noticed that we all started talking…at the beginning of school other teachers just gave us work, and she didn’t. She first wanted us to talk and then she started giving us work…now we all know each other and we’re, like, confident to talk now, and not to be shy.

Thus, Ms. Devin’s intentionally designed classroom activities prioritized learning each students’ individual names, as well as encouraging classroom participation by forming relationships with her and among her students’ classmates. Moreover, by leading these activities before she began teaching content-focused material, this critical classroom practice helped Ms. Devin’s students quickly feel recognized by their teacher and comfortable enough with one another to begin engaging with course material more confidently, especially knowing that they had begun to establish trusting relationships and connections with Ms. Devin and their peers from the first day the school year began.

Students in Ms. Schick’s social studies class also highlighted her practice of collectively creating a classroom contract the first week of the school year to establish the mutual academic and behavioral expectations in her classroom. In her interview the fifth week of the year, Tiffany observed how by setting these classroom expectations she and her classmates could successfully engage in interactive activities that helped them learn important opinions and facts from each other.

It’s a good class, how she runs it…there [was] a group discussion activity…to get to know each other and give each other our ideas on social things. She had us go into different groups. The outside group was observers of your partner and the inside group had the chance to talk…She would ask questions and everybody would answer or agree or disagree, or ask questions to that person that answered – outside people had to observe that and write down the person if they talked or not, and then we got to switch and do the same thing…it was something that I hadn’t done before…[but] I’m surely learning…if you know who you’re with in that class, you know their interests and thoughts towards what you’re learning.

Thus, by establishing clear academic and behavioral expectations in her classroom, as well as creating concrete opportunities for students to practice these interactions and expectations in her classroom, early in the year Ms. Schick established a norm of classroom communication and interaction early on in the school year that set a strong foundation for how her classroom activities, and the interactions they facilitated, could help strengthen relationships and learning with and between students’ peers.

Frequently Use Classroom Conferencing to Build Relationships, Assess Learning, Enhance Communication, and Differentiate Support

Finally, a third theme emerged in analysis of student interviews, underscoring a critical classroom practice during the first 10 weeks of the year that centered on how frequently and effectively teachers used classroom conferencing. Specifically, students explained that teachers who frequently and effectively used one-on-one teacher–student classroom conferences signaled to their students that they wanted to get to know them individually, that they were intentional about assessing their unique learning strengths, difficulties, interests, and styles of learning, and that they wanted to establish a process where they could continuously communicate with them and find ways to support their success.

AJ highlighted his experience in Ms. Talama’s English class during a classroom writing and conferencing activity she facilitated the second week of school. During this particular day Ms. Talama had her ninth grade students write reflection essays on their personal interests and needs and the ways they’ve seen teachers effectively support students in their classrooms in the past. She also asked permission to share these insights with her fellow ninth grade teachers, to help them better know how to support their new students. During the class session, as students independently wrote these reflections, Ms. Talama then used three-to-five minute one-on-one conferences with each of her students at her desk to review a previous writing assignment and better learn each of their individual strengths, difficulties, interests, and goals. Over 3 days Ms. Talama met with every one of her students individually during class time. In his five-week interview, AJ described his experience during these one-on-conferences. “It’s not like with the other teachers,” he said, “When they call you up, you feel like you’re in trouble. There it feels like you need some improvement and the teacher actually wants to help you out…when we discuss, she actually discusses, she makes us point out what we did wrong, like in an essay, and she would actually help us find new ways to correct it.” Thus, through purposefully designed activities that aimed to make space for focused, in-class, one-on-one teacher–student conferences, Ms. Talama simultaneously showed AJ and his classmates that she wanted to learn how teachers can effectively build relationships with them and that she cared about helping them, while also assessing the quality of their writing, pinpointed their unique strengths and establishing a new channel of communication to steadily improve her ability to individually support their needs and goals throughout the year.

Frequent and effective classroom conferencing also enabled teachers in this study to monitor student progress, provide specific feedback on areas to improve, and differentiate their support as needed. During her fifth week interview, Sabrina, who began struggling with her school attendance at the start of the year, following the tragic murder of her boyfriend and his mother during a home burglary the third week of school, expressed why it was important that her teachers be attentive to monitoring her progress, noticing when she was not staying on-track with her academic work, and communicating their concerns right away. Highlighting the approach used by Mr. Golan, her ninth grade algebra teacher, Sabrina emphatically identified him as the lone teacher that she trusted at Anderson because he showed that he was keeping close tabs on her grades and learning during a very difficult time in her life. She was also appreciative of the discrete, attentive approach Mr. Golan took to individually check-in with her about her absences, rather than openly expressing his concerns in front of the entire class.

Interviewer: So what does he do after days you’ve missed?

Sabrina: He says, ‘Are you okay? Why haven’t you been coming?’ He helps me make up work too. But I don’t know, it’s different…he asks me very individually. He actually takes the time to talk to me…when we first walk in the class, we sit down, and he gives us the bell ringer. So while the class is working, he’ll come to me and talk to me…He goes step-by-step by what he’s saying and he actually takes the time to make sure everybody understands it…I feel like whenever we need help, I just go to him.

Thus, even for Sabrina, who was struggling at the start of the year just to come to school and stay a full day, Mr. Golan’s classroom conferencing practices exceeded her expectations and showed her that she had a teacher who was willing to make the extra effort to assess her unique needs, and provide concrete and critical support to try and help prevent her from getting off-track during a difficult time in her life.

Mr. Golan’s classroom conferencing practices also supported students, who were excelling academically early in the year. Frequent and effective conferencing helped students reach the learning standards in his class, referred to as the “I can” statements, which were particularly important to students like Jason. “He definitely listens and he also checks the statements, the ‘I can’ statements. If you’re missing one he’ll tell you about it, and say if you need to come after school, he’ll tell you when he’s after school…He wants you to get the ‘I can’ statements.” Thus, through a thoughtful, precise, systematic, and individually targeted system designed to closely assess and monitor students’ learning progress and provide immediate feedback and support, by the tenth week of the year, Mr. Golan’s classroom conferencing system had become deeply valued by his students. It was individually tailored to assess, monitor, and communicate to each individual student their specific competencies, as well as areas for improvement, each week Mr. Golan opened lines of communication with his students, helped them mutually and closely assess and monitor their learning progress, and conveyed to them that he cared deeply about their ongoing learning and success.

Right to the End: Enhanced Ninth Grade Learning, Relationships and Wellbeing

In addition to the impact of these three critical classroom practices highlighted by students during the first 10 weeks of high school, analysis of ninth grade student interviews during the second semester further reinforced how these three classroom practices right from the start of the year also strengthened students’ trust in their teachers by the end of the year. Specifically, by leading in the development of trusting teacher–student relationships, the ninth grade teachers who used these three critical classroom practices also enhanced the learning, supports, and wellbeing of the ninth grade students in this study by the end of their first year of high school. Specifically, through their use of these three critical classroom practices right from the start of the year, by year’s end, clear themes also emerged in how students described the ways in which the trust their teachers had developed with them also enhanced their connection to Anderson. According to the students in the study, their ninth grade teachers accomplished this in two ways: (1) by making learning more enjoyable and (2) by becoming seen as a resource beyond the classroom. In turn, students also described how the impact of these practices translated into enhanced supports for their individual wellbeing both at Anderson and in the futures they envisioned for themselves beyond ninth grade.

Making Learning More Enjoyable

By year’s end, analysis of second semester interviews revealed that the more teachers used the three critical classroom practices identified in this study right from the start of the year the more they described their learning experiences in ninth grade as enjoyable. Marta, for example, during her final interview of the year, described how Ms. Devin’s embrace of classroom practices that made teacher–student trust-building a priority from the first day of the year helped make her learning more enjoyable throughout the year.

Marta: [Ms. Devin] is always making us laugh…She’ll get to know you…by talking to you and helping you to know what you need help in, what kind of person you are…she makes us write things about you…like about what you did, what you like to do. During quizzes [we write] what we like to learn, this new quarter, or what we liked last quarter.

Interviewer: So she puts that as a question on the quiz?

Marta: Yeah…so we can enjoy science…to learn more about it and make it fun…[if] you make it fun too, you learn it that way…which is way easier for you to learn in that subject.

Thus, by immediately and continuously incorporating ways to elicit insights from students about their individual and collective interests, feedback, and ideas for learning Ms. Devin simultaneously made student learning in her class more enjoyable for her students and, in turn, increased their chances of finding success in her classroom all year long.

Becoming Seen as a Resource Beyond the Classroom

In addition to continuously finding ways to make learning more enjoyable, students also highlighted how these three critical classroom practices helped they and their peers begin to see their teachers as a resource, both in the classroom and beyond. In his final interview, AJ described how Ms. Talama continuously used the knowledge she was gaining from her students throughout the year to design new assignments—such as the year-end projects they completed that explored issues directly impacting the lives of high school students. AJ believed she did this to keep her students engaged in learning activities that were relevant to their lives, as well as to help her better understand how to better support her students beyond the classroom. “I think she designed [the projects] this way because she notices teens struggle with different problems, different situations, sometimes it interferes with their work,” AJ explained, “sometimes it interferes with their lives personally, and sometimes students change, just, completely.” Thus, by continuously learning this information about her students, AJ believed Ms. Talama gained valuable insights into how to better support her students’ learning throughout the year as they grew and encountered new challenges along the way. Diana also noted how this practice helped her start to see Ms. Talama as an important resource in addressing her own challenges inside and outside of school. “[Ms. Talama] has always been asking us how we are doing or if we have any problems…some students think it doesn’t matter because they don’t want teachers to get involved into their life…[but it does].” Sharon agreed, and explained how once Ms. Talama took extra time and effort to connect with Sharon and her family early on in the school year when Sharon was struggling academically. To thank her for this extra effort, Sharon and her family invited Ms. Talama to attend Sharon’s quinceañera in the spring. After that, Sharon began to see Ms. Talama in a different light.

When you see Ms. Talama in school, it’s just about school things, but when you see her outside, she talks about her personal life or something like that so you know her more, a little deeper…it helps me in her class to feel more secure with what I am doing…I feel like we have more of a closer relationship than I do with other teachers…the one that really knows who I am, where I’m from, it’s Ms. Talama, because she knows my parents and most of my family…she was invited to my quinceañera and…[she] makes positive phone calls to your mom like, ‘oh, your daughter is doing great,’ so I think that that kind of helps you do better.

Thus, for students like Sharon, Ms. Talama’s efforts to offer and provide support was experienced in both her classroom practices and in her extra efforts to connect with her family. In turn, this practice further reinforced the close connection that she developed with Sharon and her family as well as the mutual benefits Ms. Talama gained in continuously reinforcing her role as being an educator and mentor inside and outside the classrom.

Trusting Relationships and Student Wellbeing

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, analysis of second semester ninth grade student interviews revealed that through the trusting relationships developed by their teachers, by year’s end students also described how they had begun to experience a stronger sense of wellbeing as a result of teachers’ use of these three critical classroom practices and the support and success they helped to imbue in their students. Tiffany, for example, highlighted how the relationship that she had developed with Ms. Talama by year’s end had motivated her to become a more engaged student in school, in volunteer work, and in the after school programs that Ms. Talama had encouraged her to join throughout the year. Tiffany explained, “Since like the beginning, [Ms. Talama] is always telling us…joining activities and keeping you busy—instead of doing other things out of school and stuff like that…other teachers usually don’t [do that]…they’re stressed, or don’t think it’s important…” In other words, having noticed the open and generous interpersonal qualities that Tiffany demonstrated in class early in the school year Ms. Talama helped Tiffany become involved in activities that furthered her strengths and enhanced her wellbeing by encouraging her to avoid the riskier temptations of teenage life. Thus, by continuously learning from and engaging with students about their academic and social and emotional interests, needs, and strengths, both from the very beginning and throughout the year, Tiffany saw in Ms. Talama something she didn’t in many of her other teachers—a teacher who knew that these practices were a mutual benefit to their shared teaching and learning experience and an essential way for Ms. Talama to continuously support Tiffany’s wellbeing all year long.

Discussion

This study highlights that many ninth grade students enter high school with a set of worries and hopes about high school that call teachers to proactively anticipate, accurately identify, and effectively support them during this difficult school transition. The ways in which teachers go about doing so, however, is critically important, particularly during challenging school transitions. At the start of ninth grade, when students may be feeling disconnected from the academic and social supports of their elementary school, the specific practices, and the timing of the messages, interactions, activities, and assignments that teachers use in their classroom to address student worries and affirm student hopes often signals to how, and to what degree, students can trust their teachers to support them in their new high school. These signals can also set the stage for how teacher–student relationships develop, how students interact with and learn about their new classmates, and how students connect with their new school community. What is clear is that ninth grade teachers play a lead role in this process. How their actions are perceived and understood by their ninth grade students, however, is critical for understanding how students make important social and school connections to their new high school. Simply put, understanding how trusting teacher–student relationships can be effectively developed right from the start the school year is both complex and critically important, particularly in ninth grade.

During the first 10 weeks, Ms. Talama, Ms. Devin, Ms. Schick, and Mr. Golan prioritized all or a combination of the three critical classroom practices identified by their students as effective for building teacher–student trust. In turn, this helped their students begin to trust that they could help them make important social and school connections and stay on-track in ninth grade. It is important to note that students made no mention of the other four teachers who participated in this study as using any of the three critical classroom practices identified by students during the first 10 weeks. In fact, analysis of student interviews revealed that these teachers rarely, if ever, used any of the critical classroom practice priorities highlighted in this analysis. This may be particularly concerning as some students in this study did not have Mr. Golan, Ms. Schick, Ms. Devin, or Ms. Talama at all on their ninth grade course schedules all year long. For those who did, however, the practices that they experienced in these teachers’ classrooms continuously reinforced that they were aware of the hopes, worries, concerns, and challenges that ninth grade students often encounter in this transition. Moreover, students appreciated the warm and intentional ways in which these teachers often explicitly communicated their goal of making building trusting relationships with them a top priority in their classrooms. They also embraced the activities and assignments teachers used to help students learn about and to get to know their peers, as well as to continuously assess and reinforce their interests, strengths, and ideas for how teachers at Anderson could better support them in ninth grade. Indeed, the specific needs of ninth graders inevitably change every year. However, this analysis highlights that teachers who develop specific classroom practices that can identify the needs and strengths of students early in the year, as well as establish intentional ways to start to develop trusting relationships with their students, are best positioned to effectively keep their ninth grade students on-track all year long.

Implications for Ninth Grade Classroom Practice

Themes from this study’s analysis underscore how teacher–student trust is critical for effective teaching and learning. Specifically, this study offers three concrete examples of classroom practices that do so during a critical school transition. Thus, by highlighting critical classroom practices for building trusting teacher–student relationships during this unique period of adolescence this study points to three broad implications for ninth grade teacher classroom practices.

First, this study underscores the lead role that teachers can play in building trusting teacher–student relationships. Its findings suggest that teachers must lead the trust-building process in the specific classroom practices they prioritize, especially in ninth grade when teacher–student relationships are entirely new. Moreover, the priorities that teachers make must also be clearly communicated and practiced from the first day of school forward, as doing so can have important implications for how ninth grade students begin to connect with peers and adults in their new high school. Phillippo (2012) echoes the importance of teachers leading this process right from the start of the year by describing how teacher–student relationship formation moves from ‘developing’ to ‘established’ based on students’ discernment of their teachers’ trustworthiness and cultural responsiveness. In turn, this discernment shapes students’ receptiveness to teacher interventions, as well as to teachers’ inquiries about their personal lives (Phillippo 2012); inquiries which can be critical in helping youth find the supports they need to stay on-track in ninth grade.

Second, this study underscores the close connection between teacher–student trust and culturally responsive classroom practice, particularly in supporting immigrant youth and youth of color, students who most often experience oppression, marginalization, and unequal access to resources and supports in schools. Research on culturally responsive practice has been shown to effectively improve students’ school engagement and academic performance through instructional strategies and classroom practices rooted in values of cultural pluralism and goals of educational equity (Ball 1995; Cammarota 2007; Gay 2010; Ladson-Billings 1995, 2001; Lee 1995; Santamaria 2009). A culturally responsive approach is essential for teachers to use in creating classroom contexts where immigrant youth can feel safe and supported in exploring, expressing, and affirming their identities in ways that can positively facilitate their social and school connectedness, social and emotional development, and academic performance. The widely diverse youth who participated in this study were largely first- and second-generation immigrant youth from Mexico, Guatemala, Iraq, Ghana, Romania, South Korea, and Cambodia. The eight teachers in this study, however, did not mirror the diversity of their students; only two were first-generation immigrants (one from Greece and one from Vietnam). Additionally, five teachers identified as White, one as African American, one as Asian, and one as Asian American. In spite of the differences between students and teachers, however, Mr. Golan, Ms. Schick, Ms. Devin, and Ms. Talama each developed a range of classroom practices that aimed to frequently interact with their students and learn more about their individual interests, backgrounds, strengths, and needs. Thus, each teacher made themselves well positioned to continuously gather valuable information about their students and to attentively, proactively, and collaboratively use this knowledge to support their students’ interests, strengths, and needs. It should then come as little surprise that the students in this study came to quickly trust these adults as authentically and genuinely invested in helping them forge relationships that would help them gain the knowledge, skills, resources, and information they needed to be successful in ninth grade.

Scholarship that examines how social capital is transmitted in schools and youth-serving organizations underscores the profound impact that trust and culturally responsive practices have on youth. According to Stanton-Salazar (2011) “institutional agents” who use a specific set of actions, enact distinct roles, and demonstrate particular relational qualities to help marginalized youth gain access to resources embedded in the structures of society and schools by creating authentically supportive relationships. For Stanton-Salazar these relationships are characterized by adults’ ability to: (1) demonstrate their trustworthiness, (2) develop a shared meaning of the oppressive contexts in which youth and adults interact, and (3) express solidarity with youth in helping them attain social capital—defined as the critical knowledge and information that help them develop “problem-solving capacities, help-seeking orientations, networking skills, and instrumental behaviors used to overcome stressful institutional barriers and harmful ecological conditions” (Stanton-Salazar 2011). Thus, teachers who effectively work to build trusting teacher–student relationships are also helping their students gain access to essential skills and resources, and to develop specific behaviors, that help them to be successful.

Finally, building trusting teacher–student relationships in ninth grade has important implications for students’ social and emotional development. Through their efforts, the teachers highlighted in this study also helped students’ social and emotional development during an important period of adolescence when students’ social and emotional challenges are often increasing and their academic performance is in decline. Social and emotional learning (SEL) is centered on helping students develop five core competencies: (1) self-awareness, (2) self-management, (3) social awareness, (4) relationships skills, and (5) responsible decision-making; it has also been linked to improvements in students’ social and emotional skills, attitudes, behavior, and academic performance (Durlak et al. 2011; Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning 2017). However, not all teachers are well trained, or are even willing or comfortable to use classroom practices that support students’ mental health and social and emotional development (Phillippo and Kelly 2014). Thus, the challenges ahead for enhancing teachers’ capacities for making trust building a top pedagogical priority in ninth grade may be beyond simply examining or advocating for enhancing the classroom practices which teachers adopt. Indeed, how teachers are trained and supported in their schools to make teacher–student trust building a priority make require a much larger policy and practice sea change that we are just beginning to explore.

Conclusion

Together, the findings from this study suggest that teacher–student trust is critical for effectively keeping ninth grade students academically on-track in ninth grade through the social and school connections they make as they transition from elementary to high school. The lead role that teachers take in this process is particularly important for supporting students at greater risk for declines in school engagement and performance in ninth grade, such as low-income immigrant youth of color. For teachers to better support these youth, identifying concrete classroom practices that can help them make critical social and school connections means paying close attention to how students perceive of the practices, assignments, activities, and interactions in teachers’ classrooms. With careful attention to the priorities and timing that teachers set for their classroom practices, right from the start and throughout the school year, high schools and teachers can together create stronger academic and social and emotional supports that are critical for enhancing ninth grade students’ social and school connections and ensuring their academic success and social and emotional wellbeing.

References

Allensworth, E., & Easton, J. Q. (2005). The on-track indicator as a predictor of high school graduation. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago.

Allensworth, E., & Easton, J. Q. (2007). What matters for staying on track and graduating in Chicago public schools. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago.

Baker, J. A., Grant, S., & Morlock, L. (2008). The teacher–student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. School Psychology Quarterly,23(1), 3.

Ball, A. F. (1995). Text design patterns in the writing of urban African American students: Teaching to the cultural strengths of students in multicultural settings. Urban Education,30(3), 253–289.

Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., et al. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health,40(4), 357-e9.

Bryk, A., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cammarota, J. (2007). A social justice approach to achievement: Guiding Latina/o students toward educational attainment with a challenging, socially relevant curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education,40(1), 87–96.

Catalano, R. F., Oesterle, S., Fleming, C. B., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: Findings from the Social Development Research Group. Journal of School Health,74(7), 252–261.

Chicago Consortium on School Research. (2016). 5 essentials school reports. Retrieved October 14, 2018, from https://cps.5-essentials.org/2016/s/609744/measures/trts/#performance.

Chicago Public Schools. (2011). FY09 Racial Ethnic Survey. Retrieved July 7, 2011, from http://research.cps.k12.il.us/cps/accountweb/Reports/RacialSurvey/.

Chicago Public Schools. (2012). FY09 Racial Ethnic Survey. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://cps.edu/SchoolData/Pages/SchoolData.aspx.

Chicago Public Schools. (2014). City-wide Freshman On-Track 1997–2013. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://cps.edu/SchoolData/Pages/SchoolData.aspx.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2017). Retrieved July 27, 2017 from http://www.casel.org/what-is-sel/.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher–student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research,77(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298563.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development,82(1), 405–432.

Felner, R. D. (1982). Primary prevention during school transitions: Social support and environmental structure. American Journal of Community Psychology,10(3), 277.

French, S. E., Seidman, E., Allen, L., & Aber, J. L. (2000). Racial/ethnic identity, congruence with the social context, and the transition to high school. Journal of Adolescent Research,15(5), 587–602.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Teacher’s College Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). Time for dying. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

Gregory, A., & Ripski, M. B. (2008). Adolescent trust in teachers: Implications for behavior in the high school classroom. School Psychology Review,37(3), 337.

Gwynne, J., Pareja, A. S., Ehrlich, S. B., & Allensworth, E. (2012). What matters for staying on-track and graduating in Chicago Public Schools: A focus on English language learners. Research Report. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal,32(3), 465–491.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). Crossing over to Canaan: The Journey of New Teachers in Diverse Classrooms. The Jossey-Bass Education Series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Lee, C. (1995). A culturally based cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching African American high school students skills in literary interpretation. Reading Research Quarterly,30, 608–630.

Lee, G., & Schallert, D. L. (2008). Constructing trust between teacher and students through feedback and revision cycles in an EFL writing classroom. Written Communication,25(4), 506–537.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health,74(7), 274–283.

Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative researching. London: SAGE Publications Limited.

Muller, C. (2001). The role of caring in the teacher–student relationship for at-risk students. Sociological Inquiry,71(2), 241–255.

Murray, C. (2009). Parent and teacher relationships as predictors of school engagement and functioning among low-income urban youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence,29(3), 376–404.

Phillippo, K. (2012). “You’re trying to know me”: Students from nondominant groups respond to teacher personalism. The Urban Review,44, 441–467.

Phillippo, K. L., & Kelly, M. S. (2014). On the fault line: A qualitative exploration of high school teachers’ involvement with student mental health issues. School Mental Health,6(3), 184–200.

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Quint, J., Miller, C., Pastor, J., & Cytron, R. (1999). Project Transition: Testing an intervention to help high school freshmen succeed. New York: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation.

Roderick, M. (1993). The path to dropping out: Evidence for intervention. Westport, CT: Auburn House.

Roderick, M., Kelley-Kemple, T., Johnson, D. W., & Beechum, N. O. (2014). Preventable failure: Improvements in long-term outcomes when high schools focused on the ninth grade year. Research summary. Chicago: University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research,81(4), 493–529.

Santamaria, L. J. (2009). Culturally responsive differentiated instruction: Narrowing gaps between best pedagogical practices benefiting all learners. Teachers College Record,111(1), 214–247.

Schiller, H. (1999). Effects of feeder patterns on students’ transitions to high school. Sociology of Education,72(4), 216–233.

Seidman, E., & Allen, L. (1994). The impact of school transitions in early adolescence on the self-system and perceived social context of poor urban youth. Child Development,65(2), 507–522.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2011). A social capital framework for the study of institutional agents and their role in the empowerment of low-status students and youth. Youth & Society,43(3), 1066–1109.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Van Petegem, K., Aelterman, A., Rosseel, Y., & Creemers, B. (2007). Student perception as moderator for student wellbeing. Social Indicators Research,83(3), 447–463.

Weiss, C. (2001). Difficult starts: Turbulence in the school year and its impact on urban students’ achievement. American Journal of Education,109(2), 196–227.

Wooten, A. G., & McCroskey, J. C. (1996). Student trust of teacher as a function of socio-communicative style of teacher and socio-communicative orientation of student. Communication Research Reports,13(1), 94–100.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation (Grant No. 102574). The author gratefully acknowledges Jessica Darrow, Florian Sichling, Hasan Reza, and Ben Roth for their invaluable feedback, insights, and assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brake, A. Right from the Start: Critical Classroom Practices for Building Teacher–Student Trust in the First 10 Weeks of Ninth Grade. Urban Rev 52, 277–298 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00528-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00528-z