Abstract

Given the challenging in- and out-of-school outcomes that some boys and young men of color exhibit, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners have advocated for increasing the number of Black male teachers. This strategy is predicated on the belief that having same-race and same-gender teachers can improve student learning. Drawing on Shedd’s Universal Carceral Apparatus and Brown’s Pedagogical Kind, this study used the qualitative method, specifically phenomenology, to explore the school-based experiences of 27 Black male teachers across 14 schools in one urban school district. Participants perceived that their peers and school administrators positioned them to serve primarily as disciplinarians first and teachers second. The Black male teachers described how their colleagues expected them to redirect student misbehavior. They rejected the idea that they were magically constructed or that students who were deemed as misbehaving responded to the teachers’ redirection simply because they were Black men. Instead, participants described how they attended to students’ social and emotional development, thereby influencing their capacity to engage and manage perceived misbehavior. Implications for future research are presented at the conclusion of the study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

I can see most people would feel enthused that they’re helping out their colleagues and more so like they picked me because they respect me. I can see the sense of entitlement you get, but it’s also becoming a burden now because it’s more so like I have other things to do. I have to plan. I have to get my kids or plan for my kids to be on a specific track for scope and sequence and correcting papers. Just the regular things daily things that teachers do.

Christopher Brooks, ninth-grade math teacher at

Thomas Jefferson High School

The discourse from many policymakers and practitioners around increasing the number of Black male teachers, who currently represent 2% of the educator workforce [National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) 2016], has focused on the potential of these new recruits to serve as role models or surrogate fathers to Black boys. For example, former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan (2010) described his perception of the role of Black male teachers in this way: “I used to go into elementary schools that did not have a single Black male teacher, though most of the students were Black and grew up in single-parent families. How can that be a good thing for young children, especially boys?” Such framing by policymakers that links the presence or absence of Black male teachers in schools to supporting Black boys can have the unintended consequence of positioning these teachers as being uniquely responsible for improving the schooling outcomes of Black males.

Like policymakers, researchers also have joined the call to increase recruitment efforts for Black and Latino male teachers, particularly in the implication sections of their empirical studies (Carter 2005; Gershenzon et al. 2016; Lindsay and Hart 2017). The rationale for these implications is the growing evidence that having a same-race and same-gender teacher can serve as a mechanism for improving the schooling outcomes for Black students (Lewis and Toldson 2013; Milner 2016). An analysis of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study for Kindergarten through Fifth Grade (ECLS-K-5) pointed to increases in scores in math and English for Black students when they were taught by a Black teacher (Easton-Brooks et al. 2010; Eddy and Easton-Brooks 2011). Based on Dee’s (2005) quasi-experimental findings, that teachers view students who belong to different ethnoracial groups as disruptive and inattentive, led him to conclude that “The most widely recommended policy response to these sorts of effects is arguably the ones that involve recruiting underrepresented teachers” (p. 8). While recruitment efforts are important, teacher diversity initiatives could be bolstered with a clearer understanding of how educators of color perceive their school-based experiences (Haddix 2015).

To explore the school-based experiences of Black male teachers, it is important to examine the organizational conditions in which they teach. For this reason, we draw on Shedd’s (2015) notion that urban public schools serving historically marginalized children of color are organized as extensions of prisons, a phenomenon that she called the universal carceral apparatus. Within our framework, we move from discussing the macro-organization of schools to the role of agents, specifically Black men, in schools who are tasked with managing and punishing students, specifically Black boys, who are most often perceived to be misbehaving (Carey 2017; Nelson 2016; Wallace 2017). Here, we turn to Brown’s (2012) pedagogical kind, or the notion that schools position Black male teachers to be disciplinarians first and teachers second. We then discuss the literature on Black male teachers, paying particular attention to the empirical work that illuminates the role these teachers play in their school. Recognizing the paucity of empirical research that has examined Black male educators’ perceptions of their school-based roles, we have constructed a smaller qualitative study, which is part of a larger study on Black male teachers’ pathways into the profession and their retention. This smaller study, which recruited 27 Black male teachers across 14 public schools in one urban district, answered the research question: What are Black male teachers’ perceptions of the school-based roles their colleagues and administrators expect them to play? Drawing on two rounds of semi-structured interviews with elementary, middle, and high school Black male teachers, we found that participants believed their colleagues and administrators positioned them to serve as disciplinarians first and educators second. Black male teachers described being encapsulated in the role of managing student behavior. For example, they believed that their colleagues were more likely to reach out to them for help with redirecting students’ misbehavior, and were less likely to reach out to participants with support from their teaching.

Theoretical Framework

The School as a Universal Carceral Apparatus

One function of schools, Foucault (1979) argued, is to maintain discipline over students. While schools prioritize teaching and learning, an equally competing priority is to ensure that order and discipline are maintained (Venter and van Niekerk 2011). In schools, one primary agent responsible for maintaining discipline is the teacher (McNeil 1986). Consequently, the role for teachers can extend to prioritizing punishment over teaching and learning (Sibblis 2014).

Shedd (2015) posited that the overreliance on discipline and punishment is more acute in urban spaces serving students of color from working-class families. Schools within these spaces, Shedd argued, operate as an extension of the universal carceral apparatus. Shedd’s conception of this apparatus comes from her work in Chicago, where neighborhood segregation and class stratification have been endemic for generations, leading to the hyper-segregation of Black and Latino students attending historically underfunded schools. Shedd posited that in the name of social justice and protecting youth of color from perceived and credible threats, urban public schools have adopted and made commonplace the apparatus used in carceral institutions.

Shedd contended, for example, that these schools “have begun to resemble correctional facilities. Metal detectors, surveillance cameras, and other mechanisms designed to monitor and control inhabitants are now standard equipment” (p. 80). As urban schools with large concentrations of students of color increase their over-reliance on “mechanisms” and “standard equipment” to monitor and control students, so, too, have they turned to people, such as Black male teachers, to carry out this policing. In schools, the expectation then becomes that Black male teachers are uniquely responsible for attending to the needs of misbehaving boys and young men of color (Brockenbrough 2012). This expectation is both explicit and implicit, as colleagues approach Black male teachers both formally and informally to assist with disciplining children of color (Howard et al. 2012; Pabon 2016). Black male educators are often tasked to serve in formal roles such as dean of students (a pseudonym for school disciplinarian) as well as informal roles such as a monitor for students on timeout. These expectations position Black male teachers as uniquely responsible for disciplining, or policing, children of color (Martino 2015).

The Black Male Teacher as Pedagogical Kind

Brown (2012) offered the notion of pedagogical kind where he drew upon philosopher Ian Hacking’s (1995, in Brown 2012) notion of “human kinds” to historicize the contexts in which Black male teachers emerged as possible role models for Black male students. Brown defined a pedagogical kind as a:

type of educator whose subjectivities, pedagogies, and expectations have been set in place prior to entering the classroom. In this sense, the Black male teacher has been situated directly in the context of the Black male student and received by the educational community to secure, administer, and govern the unruly Black boy in school. (p. 299)

Thus, according to Brown, the positioning of Black men to operate in singular ways within their school is a manifestation of a pedagogical kind. Moreover, Brown reminded us that the call for more Black men to enter the classroom is directly linked to policy discussions addressing the school-based performance of Black male students; these discourses generally assume that Black male teachers have dispositions and experiences that allow them to reach “troubled” Black boys.

Recent work on Black men entering the teaching profession has raised concern about the role these new recruits are expected to play in their schools, compared to the role of other teachers in the school (Bristol 2017; Goings and Bianco 2016). Researchers have described the need to move away from narrow prescriptions around recruiting Black men into schools to work with Black boys (Bryan and Milton Williams 2017; Mentor 2016).

As Black boys are perceived as exhibiting the greatest in-school behavioral challenges (Bristol 2015a; Dumas and Nelson 2016; Warren 2016), efforts to increase the number of Black male teachers and then positioning them as a pedagogical kind to attend to the needs of Black boys (Brown 2012), has the unintended, or intended, effect of encapsulating these teachers as agents of the universal carceral apparatus (Brockenbrough 2015; Rezai-Rashti and Martino 2010). Because of how Black men have been positioned in the framing used by policymakers in recruitment efforts to mentor and support Black boys (Duncan 2010), and because of the continued emphasis on the prisonization of urban schools (Kupchik 2010; Nolan 2011), Black male teachers are expected to serve primarily as school disciplinarian and only secondarily as teacher (Pabon 2017).

The early seminal research on Black male teachers focused on the need to increase the number of Black male teachers as well as to understand how these Black men have characterized their work with students (Cuban 1991; Lewis 2006; Motley 1999). This early research also described the diversity within Black men who have taught, thereby acknowledging that Black male teachers are not a homogeneous group (Lynn et al. 1999). As Lewis (2006) suggested, many of these Black male teachers considered their role bound to some form of social justice. Lewis also recounted some of the reasons why Black male teachers only comprise about 2% of the national teaching corps: “(a) low compensation offered to teachers; (b) educational obstacles, such as the NTE or PRAXIS; and (c) social and cultural impediments (e.g., culture shock at the university level)” (p. 229). He listed these items as probable factors for this enigma and laid out what he thought could be done to increase the Black male teacher population. He also stated that alternative certification programs have been helpful in aiding the growth of the number of Black males in the classroom.

According to Brockenbrough (2012), other scholars have echoed claims that Black male teachers are uniquely qualified to serve as role models for Black boys (Brown and Butty 1999; Cooper and Jordan 2003). This leads to the question of whether Black male teachers are specifically needed to help young men of color navigate their schooling, and what this might say about how these Black male teachers engage with other students. Brockenbrough reminded us of two recurring themes in Black masculinity studies that are central to bear in mind when looking at the lived experiences of Black male teachers. The first is to recognize and acknowledge the unique psychological, emotional, and spiritual toll of Black male marginality on Black men. Brockenbrough spoke to how the Black male teachers in his study had to negotiate their identities and positions within professional contexts that challenged their access to patriarchal definitions of manhood in a society that assesses men by their ability to wield patriarchal power. However, Brown (2012) reminded us that “Black men are not magically reconstructed to be positive role models capable of reaching Black youth; this image resulted from a confluence of discourse that can be traced to the sociological studies of the 1930’s” (p. 302). Moreover, given the ever increasing Black male teacher recruitment efforts in urban public schools, it is necessary to consider these conceptions of the pedagogical kind and the universal carceral apparatus when focusing on the roles, both perceived and real, of Black male teachers working in urban public schools.

While empirical evidence is growing on Black male teachers’ pathways into the teaching profession (Bridges 2011), life histories (Woodson and Pabon 2016), and practices (Simmons et al. 2013), research has not yet sufficiently explored how these educators believe fellow colleagues and administrators position them within their school building. To fill this empirical gap, we sought to address the following research question: What are Black male teachers’ perceptions about the school-based roles their colleagues and administrators expect them to play?

Methods

Data Collection

The data for this study came from a larger project that explored how school organizational conditions affected 27 Black male teachers’ pathways into the profession, their teaching experiences, and their retention in one large northeastern urban district. Students in the district were predominantly Latino and Black: specifically, 41% Latino, 36% Black, 13% White, and 9% Asian. The teaching force, however, has not kept pace with the district’s growing ethnoracial student diversity. According to publicly available data, teachers self-identified as 62% White, 23% Black, 10% Hispanic, and 5% Asian. Roughly 6% of the district’s teachers are Black men, which is higher than the national average.

To understand how the school’s organizational context influenced Black male teachers’ perceptions of their school-based experiences, the first author conducted two waves of semi-structured interviews (Seidman 2006) with 27 Black male teachers in 14 schools. Each interview lasted approximately 1 h. During the first wave of interviews, participants described their life histories, preparation to become teachers, and decisions to teach in their current schools. During the second wave of interviews, participants reflected on their school-based experiences. These reflections included interactions with students, colleagues, administrators, and parents. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed by a transcription service.

Here, we used the qualitative method, specifically phenomenology (Creswell 2009; Denzin and Lincoln 2005; Patton 1990), to explore how Black male teachers perceived their school-based experiences. A phenomenological study, which allows for an understanding of the essence of particular group or individual experiences (Bogdan and Biklen 2007), was considered suitable for this study, given its focus on exploring how the school’s organizational context affects Black male teachers’ perceptions of their organizational experiences.

Participant Recruitment and Selection

We used purposive sampling (Patton 1990) to capture a range of district schools in which teachers could teach—traditional district, turnaround (reconstituted), pilot (semi-autonomous), innovation (federally funded, autonomous), and exam schools. Traditional district schools in the district have little flexibility with central office regulations and thus are less able to exercise discretion around choosing curriculum, budgeting, and selecting students and teachers. The state gave schools designated as turnaround 5 years to “improve,” which meant increasing performance on one measure (e.g., a standardized exam); failure to improve meant the state would take over the school. To avoid state takeover, a state law passed in 2010 gave districts greater authority to improve learning. The northeastern urban district adopted a policy of replacing principals and requiring teachers to reapply for their jobs. Both pilot and innovation schools have great flexibility in choosing curricula, budgeting, and selecting teachers and students (often screening students through an application process). Exam schools require students to pass an entrance examination before being admitted.

After identifying schools, the first author sent an email to principals in which he included a recruitment letter for participants. If some principals did not respond to the email, the first author visited the schools and asked participants directly if they would like to participate in the study. In schools with more than three Black male teachers, the first author again used purposive sampling (Patton 1990) to capture a range of teacher characteristics in each school, including age, years of teaching, and subject area. The 27 Black male teachers across 14 schools were diverse in several ways (see Table 1). Participants ranged in age from 25 to 56 years old, and taught math, Spanish, English, physical education, physics, and performing arts. They had a diverse set of experiences from being in their first year of teaching to having more than 20 years of teaching experience. There was also socioeconomic diversity during the participants’ childhood and adolescence, ranging from being upper-middle class to living with a single mother and relying on government assistance. While seven participants were born in Boston or its environs, the majority were Boston transplants: They were born and raised in several cities across the United States and the African Diaspora (e.g., Caribbean and West Africa). All schools and participants were given pseudonyms to protect their identity.

Data Analysis

To direct the analysis toward answering the study’s research questions, we first read and reread the transcribed interview transcripts and Contact Summary Forms (Miles and Huberman 1994) to develop a sense of their overall meaning (Creswell 2009). Using NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software, we organized the collected data for analysis by creating codes which allowed us to ascribe meaning to the data (Miles and Huberman 1994).

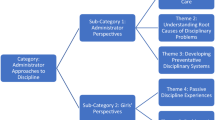

We then applied two approaches to the coding of the individual teacher interview data: etic and emic coding (Lett 1990). First, we drew on the literature from our theoretical framework on the universal carceral apparatus to create codes (i.e., etic coding). We also used emic coding to ground the codes in what participants described as their school-based experiences. After using both approaches, we collapsed the codes with the same theme into categories and identified the emerging patterns (Miles and Huberman 1994). We focused our attention on both similarities and variations in patterns in how participants described their school organizational context and retention. We summarized observed patterns for individual teachers’ perceptions of their school-based experiences. We then aggregated these patterns to make claims at the school level to identify common teaching experiences among Black male teachers in the same building. We then identified patterns across the 14 sample schools. These observed patterns across each school allowed us to address our research question. The findings below illustrate how Black male teachers in this study described their perceptions of the school based roles colleagues and administrators expected them to play.

Findings

We found that Black male teachers in our study perceived that their peers and school administrators positioned them to serve primarily as de facto disciplinarians. Specifically, participants said that their colleagues expected them to be uniquely responsible for managing student misbehavior. Black male teachers believed that their colleagues were more likely to reach out to them for help with managing student behavior and not help with designing curriculum.

We also found that Black male teachers rejected the idea that they were magically constructed (Brown 2012), or that students who were seen as misbehaving responded to their redirection simply because they were Black men. Instead, participants described how they attended to students’ social and emotional development to engage them. This attention to these aspects allowed Black male teachers to know their students as individuals.

De facto Disciplinarian

Pierce Bond, a first-year math teacher at Explorations High School, also described serving, or being expected by his colleagues to serve in a de facto disciplinary position. As Bond said, “Even though I don’t formally play the role of dean of students or anything like that,” his colleagues routinely called on him to address student misbehavior. Bond started the year willing to support his colleagues on issues of classroom management; however, by the end of the first semester in his first year as a teacher of record, Bond became conflicted over supporting his colleagues, particularly while he was teaching. As Bond noted:

I’ve been mid-lesson and had interruptions at the door for “You’ve been requested downstairs” in what’s called the Reflection Room, which is the detention room. Sometimes you have to make that decision. Do I stop whatever I’m doing now to go deal with this situation? You have to walk that fine line.

For Bond, that “fine line” appeared as a boundary between supporting his colleagues in managing student misbehavior and neglecting to teach the students in his class. Bond did not seem to have any clear answers about the tradeoff between going downstairs and staying upstairs. What was clear, however, was that Bond’s colleagues expected him, a first-year teacher, is expected by his colleagues to manage student behavior, thereby positioning him as a pedagogical kind, even at the expense of not delivering instruction to his students.

Unlike Bond, Adebayo Adjayi, a 32-year veteran, had developed a response to his colleagues who turned to him to address students’ misbehavior. Adjayi taught prekindergarten students with mild to severe autism at Crispus Attucks Elementary School. Adjayi recounted how his colleagues would routinely send misbehaving students into his classroom during his planning periods and, more troubling, when he was teaching. For Adjayi, being responsible for managing student misbehavior proved problematic for two reasons: (a) the students sent to him would soon be taking the state’s standardized exam and would be missing content while with him; and (b) students were often much older than the kindergarteners Adjayi taught and they created classroom management challenges when they were in his classroom. As Adjayi said:

They [my colleagues] used to bring fifth grade students to my classroom to keep them. At a point, I told them this is not working because these students should be taking MCAS [state standardized exam] and keeping them with four-year-olds is wasting their time. My para[professional] said she wouldn’t take responsibility of anything because some of them come; they wander and make noise. She says she is only allowed to take care of my own children, my students. That’s all she would take care of, so when it became an issue for me, I told them.

Adjayi recognized that his classroom became the school’s disciplinary room, a holding area, and he had become the school disciplinarian. Without considering the type of environment that would most support Attucks’s students who were deemed misbehaving, the fifth graders were placed in the same classroom as the prekindergartners. Adjayi, as an agent of the universal carceral apparatus, was expected to manage and monitor the fifth-grade students.

While Adjayi initially appeared to accept assisting his colleagues with students they found challenging, he also described the increased burden of having to attend to his prekindergartners with special needs along with the fifth graders sent to his room. Out of frustration, Adjayi approached the school’s principal to share his discontent. Adjayi did report that students stopped coming, but he was unclear about who in his school was really responsible for them.

Like Bond, Christopher Brooks, a third-year math teacher at Thomas Jefferson High School, also expressed his growing frustration with having to be responsible for managing the behavior of his colleagues’ students. Brooks characterized his classroom as the unofficial “timeout room” on the floor where he taught. He did not volunteer to serve in this role. However, he first said yes to one teacher who asked him, “Can you just talk to so-and-so because he’s not giving up his phone?” and then to another colleague who asked, “Can I leave Shawn in here? He can’t seem to sit still?” By that time, it had become the unspoken norm that Brooks would attend to his colleagues’ misbehaving students. Brooks described his feeling of having to manage the floor’s “timeout room,” while simultaneously teaching an equal number of classes as his colleagues did:

I can see most people would feel enthused that they’re helping out their colleagues and more so like they picked me because they respect me. I can see the sense of entitlement you get, but it’s also becoming a burden now because it’s more so like I have other things to do. I have to plan. I have to get my kids or plan for my kids to be on a specific track for scope and sequence and correcting papers. Just the regular things, daily things that teachers do. But as far as now, it’s like it’s played a role into how I organize my day because I know fifth period I’m gonna get him or sixth period I know I have to hurry up and finish eating lunch because I know there’s going to be a problem that arises.

Here, Brooks acknowledged the burden of serving as a pedagogical kind, the floor’s de facto disciplinarian, while also being responsible for the demands of planning and teaching math to his students. Moreover, in addition to not having enough time for his students, Brooks described inadequate time to eat his lunch. For Brooks, the continued inability to take a break, eat, and replenish his own energy because he was expected to monitor other colleagues’ students added to the “burden” that characterized his school-based experience.

Brooks used these one-on-one interactions with the young men he was expected to manage and control to understand why their teachers might have seen them as misbehaving. He acknowledged that many of the young men were disruptive, but they engaged in this behavior because they could “get away with it.” Brooks believed that because his colleagues had not created and enforced clear expectations about how to be productive and engaged members of the classroom, the students misbehaved. In reflecting on why one colleague continued to have challenges redirecting one student, Brooks noted, “If there’s no limitations or you’re not consistent on your limitations, he’ll play you for a fool and that’s what he’s doin’ right now and he’s getting away with it.” Despite this recognition that his colleagues’ classroom management challenges resulted from their inability to create structures that supported students, Brooks nonetheless bore the burden of managing student misbehavior while fulfilling the everyday tasks associated with being an educator; namely, teaching, planning, and taking lunch breaks.

George Little, a fifth-year teacher at Jefferson, confirmed Brooks’s sentiments about the role Black male teachers played at their school. In addition to colleagues who expected the Black faculty to serve as disciplinarians, Little believed that the principal assigned him the administrative task of monitoring students during dismissal. While Jefferson’s teachers, like all district teachers, are contractually obligated to serve in an administrative role, Little did not think it was a coincidence that school administrators tasked him as well as Mr. Brooks and other Black male teachers to, as he noted, “police” the front of the building during dismissal:

Teachers of color have been tapped to have certain jobs or duties based on their being a male or also being a male and person of color. [Mr. Brooks], me and another African American man had outdoor duty, to just kind of monitor and police the front of the building at dismissal times just to usher students away from the building and make sure there is no issues outside the building…. It was clear and evident why we were chosen for those roles.

The roles that Little and other Black male teachers believed their colleagues and administrators expected them to serve essentially positioned these educators as agents within the universal carceral apparatus. Black male teachers noted having to act as disciplinarians first and teachers second. In these urban schools, comprised mostly of children of color from historically marginalized communities, the Black male teachers said that their peers routinely expected them to monitor and punish misbehaving students. Participants, however, were keen to point out how they redefined the role of behavior manager. They articulated the requisite skills and competencies needed to improve student behavior. In so doing, they posited that their social location—Black and male—did not make them effective managers of student behavior. Instead, they felt that their ability to build relationships and get to know the students as individuals influenced their success in re-engaging these challenging students.

Here, we found that these Black male teachers were positioned as a pedagogical kind and served as agents within the universal carceral apparatus. Participants perceived their role at their schools as the adults responsible for policing, and whether the teachers were resentful or accepting of such a role, the perception nonetheless existed.

Not Magically Constructed: Getting to Know Students as Individuals

While participants described school administrators and staff as positioning them to manage and monitor students, they refused to accept that their success in engaging students was the result of being magically constructed (Brown 2012). The Black male teachers reflected on how they skillfully attended to students’ social and emotional development, which increased engagement. For example, Dennis Sangister, an English teacher at the K-8 school Marcus Garvey acknowledged that his colleagues routinely turned to him to redirect misbehaving students. Sangister, in his sixth year of teaching, said that he resisted serving as the school’s dean of disciplinarian. He recounted how his colleagues expected him to quiet students at the end of lunch in the cafeteria before they returned to their class.

My colleagues, because they know that I can do that, it’s almost like every time it’s expected that I do it. And I don’t because I feel like we all get paid a salary and we all are, as a part of our job criteria, for having our jobs is classroom management. For me, I feel like it’s unfair to always have to do that. So I don’t always do it—purposely and strategically…. I’ll be eating an apple and acting like “Oh my mouth is full,” and wait to see who else will do it.

Instead of focusing his time and attention on serving as school disciplinarian, Sangister described how he worked to improve classroom practices that would mitigate misbehavior. Sangister recalled attending a summer professional development session on classroom management. There, he learned the importance of building bridges between students’ experiences at home and the classroom. After attending the workshop, Sangister required students as their first assignment to bring in a picture of family members whom they loved: “Any time a kid is acting crazy in this class—we had one kid who was kind of a behavioral issue. But any time I told him to go stand and look at that wall he calmed down.” Sangister went on to describe how he treated his class as a “house” and worked to ensure that students felt they were part of a “family.” His success in redirecting student misbehavior came from attending professional development to improve his classroom practice. In so doing, he learned ways to make his classroom a welcoming space for students, all in the service of student learning.

Peter Baldwin, a first-year teacher at Apple Pilot Elementary School, expressed some reservations about his unofficial role of managing the behavior of challenging students, but maintained his decision to get to know students. Baldwin described that among the three teachers in his special needs classroom, it was a “one-man show” when managing student behavior. In particular, Baldwin suggested having to be uniquely responsible for one Black boy, despite this student having a one-to-one teacher. In addition to the one-to-one teacher and a co-teacher (both White women), Baldwin noted, “When things escalate, I am the one that addresses it.” He cited one example at the end of one class session when the male student started “kicking things and so I was supposed to go lunch, but then I stayed behind to make sure that she [the one-on-one teacher] was able to figure it out. But then he got too—so I ended up corralling him.” In physically restraining this student, Baldwin submitted, “I don’t like restraining and I don’t—it doesn’t feel comfortable, so when I cannot, I try to not.”

While Baldwin acknowledged that this student received fewer suspensions this year than before and he was on track not to repeat the grade, he appeared annoyed by his colleagues’ underlying assumption of why he specifically should be responsible for managing behavior. Baldwin recounted his co-teacher saying, “You should be able to talk to him about XYZ man to man or you should be able to blah, blah, blah.” Over time, Baldwin developed a “bond” with his Black male student, but not for the assumptions his colleagues held. One of Baldwin’s challenges in accepting his colleagues’ belief about why he was equipped for the role of working with this male student might have been because of his identification as a “a young Black gay male.” As such, Baldwin appeared to reject hetero-normative (Alexander 2006; Boykin 1996; Connell and Messerschmidt 2005; Haase 2010) assumptions about the role of Black male teachers. As he stated, “[Based on] my personal life, just because someone else is male does not mean that I am going to have some magical connection with them.” Instead, Baldwin credited his ability to get to know this student as follows,“I don’t think he was just gonna respond to me better than others because I’m me, or because I’m a male or because I’m Black. I think because I sort of invested time…we’ve built a relationship.” Here, Baldwin redefined the requisites needed to manage challenging students beyond race and gender to focus instead on the importance of building relationships with students.

Similar patterns held with Okonkwo Sutton, a first-year teacher at Explorations Charter School. Sutton also did not mind being called on to address student misbehavior. He described his colleagues “looking to me, being a Black male figure of authority to kind of step in. I tend to have a little more pull with the kids in that area.” Like Young, Sutton did not appear to be bothered by serving in a role that required him to be consistently responsible for managing student misbehavior. “I don’t mind it. I understand it because I know how to speak the kids’ language. And at the same time I’ve had a very similar childhood and background as many of them.” Sutton described one instance when a teacher emailed him to say, “‘Hey, this student is giving me a hard time. Maybe you can talk to him.’ I’ve done so and been able to mediate whatever issue there was.” While his colleagues asked Sutton to speak mostly with young men, on occasion he also redirected young women. As a first-year teacher, Sutton embraced the responsibility of stepping into support his colleagues when addressing student misbehavior.

Finally, veteran teacher Wole Achebe, who taught at Grand Case Pilot School, seemed, much like Sutton, to accept having colleagues ask him to watch over students. For Achebe, such an occurrence seemed part of his everyday work, as he noted,“Sometimes, a colleague would say, ‘Do you mind if I keep the student here in this classroom, in your class for a while?’ Or, ‘Can you…’ Yeah, sometimes they’ll tell me to talk to students that I have a close relationship with.” But Achebe has not always been able to manage student behavior. In fact, Achebe was fired after his first year of teaching because he was unable to manage student behavior. Over the years and through “reflection,” he has learned that the “students that we service in Boston come from very difficult backgrounds and upbringings.” In response to this, Achebe noted that he has “forge[d] relationships with [his] children [students] before [he] actually enacts any disciplinary action.” Achebe also realized that his expectations for how students behaved in school should not be based on his own schooling experiences in Nigeria or private schools in the United Kingdom. Achebe’s role of supporting teachers to manage misbehavior suggested that merely being Black and male does not allow one to manage behavior effectively. Instead, as Achebe submitted, he developed skills that increased his ability to manage students’ behavior.

Participants appeared to resist the idea that their maleness and/or Blackness made them uniquely qualified to manage and monitor students’ perceived misbehavior. Black male teachers described how they built relationships with students and got to know them as individuals. They did not see themselves as being the supernegro (Baldridge 2017) or possessing an elusive elixir for working with students, who were most often boys and young men of color. Instead, participants turned away from being positioned as agents of the universal carceral apparatus. As such, both the conceptions of pedagogical kind and the universal carceral apparatus are useful in further discussions and analysis when looking at Black male teachers as disciplinarians in schools.

Conclusion

In this article, we sought to answer the question: What are Black male teachers’ perceptions about the school-based roles their colleagues and administrators expect them to play? Black male teacher participants described that one role colleagues assigned to them in the organization was being responsible for students—often males—who misbehaved. The answers given in their interviews are not meant to be representative of all of the Black men in the study or across the research spectrum. Moreover, participants were also heavily influenced by whether they felt fellow teachers and administration supported them at their schools; by whether they were purposefully or unintentionally placed in positions as disciplinarians; and by what they perceived their academic purpose and aspirations were.

Even though similar experiences ran through each of the participants’ stories and commentaries, it is not possible to generalize the findings of this study to all members of the same population. All of the participants spoke to issues of race, the criminalization of the Black body, having been silenced or marginalized in education, and being positioned in schools as the teachers who were supposed to mete out discipline. Each of the Black men in this study spoke to these points from their own unique and individual experiences. To address the experiences of these participants as well as of Black male teachers whose experiences may be similar, we outline the following recommendations for research, policy, and practice.

Research

To continue highlighting the school-based experiences of Black male teachers, more research is needed. Currently, the sample sizes of Black male teachers in different studies remain relatively small. Additional research should also use experimental and quasi-experimental methods to make causal claims about the experiences of Black male teachers. Future research should also explore students’ perceptions of their Black male teachers. Researchers may want to understand if students, particularly boys and young men of color, perceive their Black male teachers as pedagogical kinds and agents of the universal carceral apparatus.

Policy

The growing policy initiatives focused on recruiting Black men to the blackboard frame the urgency of these efforts as addressing the underperformance of boys and young men of color. As such, policymakers position Black men as a pedagogical kind even before these new recruits enter the school. As such, policymakers should frame efforts to increase the ethnoracial diversity of the country’s educator workforce as benefiting all students in this increasingly diverse society (White 2016).

Practice

Finally, the narrations provided by these participants have the power to influence the creation of supportive spaces for Black male teachers as well as allow teacher trainer practitioners (Gist 2017) and policymakers to listen to these words so that we can learn to create and sustain environments that address the unique needs of Black male teachers. Moreover, the experiences of these Black male teachers have important implications for schools and school districts (Bristol 2015b). As Brown (2012) reminded us, “If schools only envision these teachers’ roles as one dimensional, they run the risk of enclosing and delimiting their pedagogical potential” (p. 312). School administrators should work to develop more expansive roles for Black male teachers and become more cognizant of how Black male teachers are implicitly and explicitly positioned in their schools. Equally important, administrators should work to develop the capacity of all teachers to support and engage all students.

References

Alexander, B. K. (2006). Performing Black masculinity: Race, culture, and queer identity. Lanham, MD: Rowman Altamira.

Baldridge, B. J. (2017). “It’s like this myth of the Supernegro”: Resisting narratives of damage and struggle in the neoliberal educational policy context. Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(6), 781–795.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Boykin, K. (1996). One more river to cross: Black and gay in America. New York, NY: Anchor.

Bridges, T. (2011). Towards a pedagogy of hip hop in urban teacher education. The Journal of Negro Education, 80(3), 25–338.

Bristol, T. J. (2015a). Teaching boys: Towards a theory of gender-relevant pedagogy. Gender and Education, 27(1):53–68.

Bristol, T. J. (2015b). Male teachers of color take a lesson from each other. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(2):36–41.

Bristol, T. J. (2017). To be alone or in a group: An exploration into how the school-based experiences differ for Black male teachers across one urban school district. Urban Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085917697200.

Brockenbrough, E. (2012). Emasculation blues: Black male teachers’ perspectives on gender and power in the teaching profession. Teachers College Record, 114(5), 1–43.

Brockenbrough, E. (2015). “The discipline stop”: Black male teachers and the politics of urban school discipline. Education and Urban Society, 47, 499–522.

Brown, A. L. (2012). On human kinds and role models: A critical discussion about the African American male teacher. Educational Studies, 48(3), 296–315.

Brown, J. W., & Butty, J. M. (1999). Factors that influence African American male teachers’ educational and career aspirations: Implications for school district recruitment and retention efforts. Journal of Negro Education, 68, 280–292.

Bryan, N., & Milton Williams, T. (2017). We need more than just male bodies in classrooms: Recruiting and retaining culturally relevant Black male teachers in early childhood education. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 38(3), 209–222.

Carey, R. L. (2017). “What am I gonna be losing?”: School culture and the family-based college-going dilemmas of Black and Latino adolescent boys. Education and Urban Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124517713112.

Carter, P. L. (2005). Keepin’ it real: School success beyond Black and White. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859.

Cooper, R., & Jordan, W. J. (2003). Cultural issues in comprehensive school reform. Urban Education, 38, 380–397.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Cuban, L. (1991). History of teaching in social studies. In J. P. Shaver (Ed.), Handbook of research on social studies teaching and learning (pp. 197–209). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Dee, T. S. (2005). A teacher like me: Does race, ethnicity, or gender matter? The American Economic Review, 95(2), 158–165.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dumas, M. J., & Nelson, J. D. (2016). (Re)imagining Black boyhood: Toward a critical framework for educational research. Harvard Educational Review, 86(1), 27–47.

Duncan, A. (2010). Changing the HBCU narrative: From corrective action to creative investment. Durham, NC: Remarks by Secretary Arne Duncan at the HBCU symposium at the North Carolina Central University Centennial.

Easton-Brooks, D., Lewis, C., & Zhang, Y. (2010). Ethnic-matching: The influence of African American teachers on the reading scores of African American students. National Journal of Urban Education and Practice, 3(1), 230–243.

Eddy, C., & Easton-Brooks, D. (2011). Ethnic matching, school placement, and mathematics achievement of African American students from kindergarten through fifth grade. Urban Education, 46, 1280–1299.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Gershenzon, S., Holt, S. B., & Papageorge, N. W. (2016). Who believes in me? The effect of student-teacher demographic match on teacher expectations. Economics of Education Review, 52, 209–224.

Gist, C. D. (2017). Voices of aspiring teachers of color: Unraveling the double bind in teacher education. Urban Education, 52, 927–956.

Goings, R. B., & Bianco, M. (2016). It’s hard to be who you don’t see: An exploration of black male high school students’ perspectives on becoming teachers. Urban Review, 48, 628–646.

Haase, M. (2010). Fearfully powerful: Male teachers, social power and the primary school. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 18(2), 173–190.

Haddix, M. (2015). Cultivating racial and linguistic diversity in literacy teacher education: Teachers like me. New York: Routledge.

Howard, T. C., Flennaugh, T. K., & Terry, C. L., Sr. (2012). Black males, social imagery, and the disruption of pathological identities: Implications for research and teaching. The Journal of Educational Foundations, 26(1/2), 85.

Kupchik, A. (2010). Homeroom security: School discipline in an age of fear. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Lett, J. (1990). Emics and etics: Notes on the epistemology of anthropology. In T. N. Headland, K. L. Pike, & M. Harris (Eds.), Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate (Frontiers of anthropology, 7). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lewis, C. (2006). African American male teachers in public schools: An examination of three urban school districts. Teachers College Record, 108(2), 224–245.

Lewis, C. W., & Toldson, I. A. (Eds.). (2013). Black male teachers: Diversifying the United States’ teacher workforce. Howard House, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Lindsay, C. A., & Hart, C. M. D. (2017). Exposure to same-race teachers and student disciplinary outcomes for black students in North Carolina. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(3), 485–510.

Lynn, M., Johnson, C., & Hassan, K. (1999). Raising the critical consciousness of African American students in Baldwin Hills: A portrait of an exemplary African American male teacher. Journal of Negro Education, 68(1), 42–51.

Martino, W. J. (2015). The limits of role modeling as a basis for critical multicultural education: The case of Black male teachers in urban schools. Multicultural Education Review, 7(1–2), 59–84.

Mentor, M. (2016). Black male teachers speak: Narratives of corps members in the NYC teach for america program. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Columbia University.

McNeil, L. M. (1986). Contradictions of control: School structure and school knowledge. New York, NY: Routledge.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Milner, H. R. (2016). A Black male teacher’s culturally responsive practices. The Journal of Negro Education, 85(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.85.4.0417.

Motley, C. B. (1999). Equal justice under law: An autobiography. New York, NY: Macmillan.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2016). Number and percentage distribution of teachers in public and private elementary and secondary schools, by selected teacher characteristics: Selected years, 1987–1988 through 2011–2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved October 15, 2017 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_209.10.asp.

Nelson, J. D. (2016). Relational teaching with Black boys: Strategies for learning at a single-sex middle school for boys of color in New York City. Teachers College Record, 118(6), 1–30.

Nolan, K. (2011). Police in the hallways: Discipline in an urban high school. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Pabon, A. (2016). Waiting for black superman: A look at a problematic assumption. Urban Education, 51(8), 915–939.

Pabon, A. J. M. (2017). In hindsight and now again: Black male teachers’ recollections on the suffering of black male youth in US public schools. Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(6), 766–780.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Rezai-Rashti, G., & Martino, W. (2010). Black male teachers as role models: Resisting the homogenizing impulse of gender and racial affiliation. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 37–64.

Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Shedd, C. (2015). Unequal city: Race, schools, and perceptions of injustice. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sibblis, C. (2014). Expulsion programs as colonizing spaces of exception. Race, Gender, and Class, 21(1/2), 64–81.

Simmons, R., Carpenter, R., Ricks, J., Walker, D., Parks, M., & Davis, M. (2013). African American male teachers and African American students: Working subversively through hip-hop in three urban schools. The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 4(2), 69–86.

Venter, E., & van Niekerk, L. J. (2011). Reconsidering the role of power, punishment and discipline in South African schools. Koers: Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 76(2), 243–260.

Wallace, D. (2017). Distinctiveness, deference and dominance in Black Caribbean fathers’ engagement with public schools in London and New York City. Gender and Education, 29(5), 594–613.

Warren, C. A. (2016). We Learn Through Our Struggles”: Nuancing notions of urban Black male academic preparation for postsecondary success. Teachers College Record, 118(6), 1–38.

White, T. (2016). Teach for America’s paradoxical diversity initiative: Race, policy, and Black teacher displacement in urban schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(16), 1–42.

Woodson, A., & Pabon, A. (2016). “I’m none of the above”: Exploring themes of heteropatriarchy in the life histories of Black male educators. Equity and Excellence in Education, 49, 57–71.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bristol, T.J., Mentor, M. Policing and Teaching: The Positioning of Black Male Teachers as Agents in the Universal Carceral Apparatus. Urban Rev 50, 218–234 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0447-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0447-z