A fool who thinks that he is a fool is for that very reason a wise man. The fool who thinks that he is wise is . . . a fool indeed.—The Teaching of Buddha, DHAMMAPADA 63.

Abstract

No longer can teachers in the US simply close their classroom doors and isolate themselves, their classrooms, their students; that is, if they ever could. More than ever before, larger political, sociocultural and ideological forces find their way into the classroom on the backs of so-called educational reforms. But not every educational reform results in school improvement, and precious few educational reforms benefit teachers and their work life. Educational reforms have wrought tremendous change on the classroom and on the teacher. Public schools and the teachers who inhabit them are bleeding out in a death by a thousand cuts. Support for public education is dwindling. Accountability, high-stakes tests, prescriptive ‘teacher-proof’ curriculum, and more, serve to stifle creativity, quash innovation and otherwise eat away at teachers’ professional discretion, independence and autonomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this article, I examine schooling today, especially how global trends, fads, movements, discourses and narratives, and irrationalisms affect local conditions. I will show how it is that teachers, more than any other, suffer a death by a thousand cuts, in a metaphorical sense. That is to say that the injustices done to and by teachers, one to another, the forces at play and the subsequent compromises that educators are forced to make day in and day out are so egregious that, were we but to examine them in toto and coolly, we would surely see them for what they are and put a stop to them. But it may be that the juggernaut of public school accountability has such inertia as to be unstoppable, even unmanageable; which would be ironic, wouldn’t it, that a management system has itself become unmanageable?

In broad stokes, we are dealing here with schools and schooling. At the very heart of the issue is what it means to be a teacher today. As I develop my theses, I will take up issues having to do with the larger historical moment(s) of which we are all part; with issues of work, especially the work of teachers and administrators; with schools as workplaces and as educational sites; and with how all this is changing. These issues have to do with teaching as a profession, the teacher as a professional and with greater issues of professional discretion, freedom and autonomy. Ultimately, though—and as I will suggest—these are matters which affect the education of our children and, by extension, our futures.

There are numerous challenges for those undertaking an analysis and critique such as this. One such challenge has to do with tone and fairness: The social observer or kulturkritik (see Huyssen 1987, p. x) must be seen to be even-keeled, if not fair and ‘objective’; which is somewhat ironic in the present case, as the targets of my criticism—demagogues, charlatans, ideologues and so on—are, almost by definition, less than fair, far from objective.

Another of the challenges present in this type of project is more ideo-scientific; which is to say that the modern-day kulturkritik is heir to the intellectual discourses, operations and procedures of the Enlightenment and its science(s)—“from the public exposure of lies to the benign correction of error to the triumphant unveiling of a structurally necessary false consciousness by ideology critique” (Huyssen 1987, p. xii), which, according to Huyssen, “will no longer do.” The scholar, the kulturkritik, treads a fine line between borrowing from or using Enlightenment tropes and perpetuating these or other grand narratives. Scholars who do this work must be intellectually fleet of foot, reflexive and self-critical, or at least seem to be so. Yet another, somewhat related challenge in this work is how to avoid falling into a relatively simple-minded nihilistic form of postmodernism (or seeming to) where, in the minds of some, ‘anything goes,’ where there is no footing—moral, ethical, intellectual footing—and where there is no hope, no way forward.

Conversely, scholars who do this work are best advised to avoid ready-to-hand prescriptions for the work or practice of others. This would simply be hypocritical. Finding one’s way, working through an educational landscape of quick fixes; failed reforms; ‘junk,’ misunderstood and misapplied or hijacked science, and doing so with honesty and integrity, presents its own challenges. To work in this way I will strive to avoid ad hominem attacks or to demonize all educational reformers or paint them with too broad a brush. What I will do is point to some characteristics of reforms and reformers that should give us pause and trust the reader to make her own interpretations and fashion his own applications.

Winds of Change

Due in part to the rise of neo-liberalist thinking across the globe, its contribution to overall changes in social relations, including work relations, teachers and other workers find that they have fewer and fewer degrees of freedom, less autonomy and less discretion in their work. Two recent polls—one a collaboration between the Gallup organization and Healthways (Lopez and Sidhu 2013) using a Well Being Index, and the other done by the Harris group for the insurer MetLife (2013), called the Survey of the American Teacher—found significant work issues for teachers.

Teachers scored highly on the Well Being Index (Lopez and Sidhu 2013) in all areas except work environment. The report’s authors noted high levels of teacher work-related stress, which they found remarkable, given that work stress generally rose with income level. They called attention to “the potential emotional health burden that teaching carries” (¶ 4). Of the occupational groups surveyed, teachers fell in the middle on the item that gauged relationships with administrators (i.e., my “‘supervisor treats me more like a partner than a boss’”). Teachers rated the openness and trust of their work environment the worst among all the other occupational groups surveyed. Interestingly, and a point noted by the report’s authors, teachers’ relatively low composite work environment score was shared by “another female-dominated profession—nurses” (¶ 6).

Similarly, the Harris MetLife survey of the American teacher (MetLife 2013) found teachers’ job satisfaction to be at a 25-year low, with more than half of those surveyed reporting “feeling under great stress several days a week” (p. 6). Stress, according to the report, is related to a lack of control in decision making, at least for principals (p. 33), likely for teachers as well. Elementary school teachers were found to have the greatest increase in the stress experienced. The report noted how “less satisfied teachers are more likely to be located in schools that had declines in professional development . . . and in time for collaboration with other teachers” (p. 6). Overall, for teachers, declines in school budgets correlate with decreased job satisfaction. Greater levels of stress are found among those who occupy the lower rungs of hierarchical social groups, especially when those structures are relatively fixed, manifesting a lack of social mobility (Waite 2010). Teachers, generally, are poorly paid relative to other professions, have little time for collaboration, have limited or no autonomy, and sit on the lower rungs of rather rigid hierarchical systems.

Stringent and over-done accountability measures impinge upon teachers’ autonomy and professional discretion and contribute to their job-related stress. Such regimes were described by the then Commissioner of the Texas Education Agency as “a ‘perversion’ of the system” (Weiss 2012, ¶ 2), resulting in an “overemphasis on test results at the local level.” Although the education commissioner was appointed by and served under a staunchly conservative and long-serving Republican governor, his criticism of the testing and accountability regimes could not have been more emphatic when he called it the “‘heart of the vampire.’”

The accountability movement has gained such tremendous traction in education as a manifestation of neoliberalism—a socio-economic ideology that has taken root across the ‘developed’ world. Some of the hallmarks of neo-liberalism include belief in a libertarian view of a ‘free market’ system, ‘choice,’ standards, standardization, measurement, accountability and control.

Neoliberalism, with its attendant accountability systems, undercuts teacher autonomy and professional agency. But it’s not simply public school accountability—with its high-stakes testing and its naming, blaming and shaming of public schools and public school teachers—that imperils teachers’ professional agency and, by extension, public education. There are many factors that, combined, contribute to this ‘death by a thousand cuts’ for teachers and public schools. Many ill-conceived and potentially dangerous interventions (i.e., reforms) are invented, manufactured, introduced, spread or made worse by those I liken to charlatans, sorcerers, alchemists, demagogues, profit-mongers, tyrants and kings masquerading as educational reformers. My point—that many educational reformers have questionable motives and bona fides (Waite et al. 2015)—was underscored by two disparate sources; one being the lay press and the other a former student.

A news story in The New York Times (Dillon 2010), titled “School Reform Draws a Crowd, Not Credentials,” observed how, with there being so much federal and state money behind educational reform initiatives in the US, individuals and conglomerates are rushing to cash in. In 2010, the US Department of Education “sharply increased federal financing for school turnarounds, to $3.5 billion this year” (p. A11). The Times quoted a former New York City schools chancellor, who himself had formed his own consulting company, as saying that “‘this is like the aftermath of the Civil War, with all the carpetbaggers and charlatans’” (p. A11).

A former student of mine now works for a lobbying firm in Austin, Texas, the state capitol, where she represents different associations of educators, administrators and school boards. During the last legislative session, she sent me a text with a link to a news story, asking: “I’d be interested in your thoughts on this article/study. We’re surrounded by kool-aid-drinking think tank ‘reformers’ in Austin who know too little about pub[lic] ed[ucation]” (M. Smith, personal communication, May 7, 2015).Footnote 1

To be sure, not all educational reformers fit this mold, but there are enough careerists and opportunists parading as reformers to justify our wariness and skepticism of those with a reform agenda. And it is not just the egregious offenders among the lot—the charlatans, the demagogues, profit-mongers and others—that cause the most harm. Generally, these louts are the easiest to spot, the easiest to defend against; but it is the lesser kings, the petty tyrants, the sorcerers’ apprentices who can do the most damage—those 1000 tiny cuts, because their effects are multiplied across time and systems.

It is in this way that Ariely (2013) described dishonesty (lying, cheating, fraud, etc.) and its effects. His assertion is that all of us lie a wee bit, even to ourselves. Some of us, under certain conditions, lie and cheat quite a bit, and some of us do a so a lot and to a great extent. Ariely made the case (NPR 2012) that the most egregious instances of corruption, thievery, graft and so on may grab the headlines, but the harm done in these extreme cases is much less than that caused by the relatively more commonplace transgressions, multiplied.

Experts, Sorcerers, Alchemists and Other Wise Men

To a large degree, these educational reformers (and others, such as certain professors of education and educational leadership) fit Nietzsche’s (1968) categorization of ‘the famous wise men.’ Nietzsche chided these famous wise men thus:

You have served the people and the superstition of the people, all you famous wise men—and not the truth. And that is precisely why you are accorded respect. And that is also why your lack of faith was tolerated; it was a joke and a circuitous route to the people. Thus the master lets his slaves have their way and is even amused by their pranks.

But the free spirit, the enemy of fetters, the non-adorer who dwells in the woods, is as hateful to the people as a wolf to the dogs. . . .

It was ever in the desert that the truthful have dwelt, the free spirits, as masters of the desert: but in the cities dwell the well-fed, famous wise men—the beasts of burden. For, as asses, they always pull the people’s cart . . . they remain such as serve and work in a harness, even when they shine in harnesses of gold (pp. 214–216, emphasis in original).

These wise men (and women) (and those not so wise) are the charlatans, sorcerers, alchemists, demagogues, profit-mongers, tyrants and kings which concern us here. Popularity, celebrity, the adoration of the herd, bouys these persons, raises them up, gives them power and emboldens them. Often, the substance of what these personalities have on offer is weak or lacking entirely and their primary positive attribute, the thing that recommends them, is their popularity or celebrity. The dynamics of the herd—as is the nature of status hierarchies—draws educators’ and educational leaders’ attention to those authors and their models of reform already popular. This momentum or inertia helps them become even more popular, often without critical scrunity.

An Historical Example as a Parable

Some time ago, in the late eighteenth century, the American diplomat, printer, author, natural philosopher and revolutionary, Benjamin Franklin, collaborated with Antoine Lavoisier, at the behest of the French government, to investigate and report on a phenomenon sweeping through French society (Gould 1989). Franz Anton Mesmer, a physician, claimed to have discovered vital energies which coursed through the human body, energies he referred to as animal magnetism. Mesmer, and soon the numerous people trained by him, diagnosed human maladies caused by the misalignment of these energies and prescribed remedies for them. He became a celebrity and his movement attracted hordes of followers, including many from the elite French social circles. (Today we still use the term mesmerized, owing to Mesmer and his quackery.)

The rapidity, breadth and depth by which Mesmer’s social movement took hold in France so alarmed certain influential members of the French government that they feared that it would upset the social order. The French enlisted Franklin and Lavoisier to investigate Mesmer and his claims. In their report, these scientists held that:

The art of concluding from experience and observation consists in evaluating probabilities, in estimating if they are high or numerous enough to constitute proof. This type of calculation is more complicated and more difficult than one might think. It demands a great sagacity generally above the power of common people. The success of charlatans, sorcerers, and alchemists—and all those who abuse public credulity—is founded on errors in this type of calculation. (Franklin & Lavoisier, 1794, Rapport des commissaires chargés par le roi de l’examen du magnétisme animal, cited in Gould 1989, p. 7)

Stephen Jay Gould, the biologist and public intellectual, went further. He brought Franklin’s and Lasovier’s conclusion to bear on what was for him one of the more disconcerting problems of the modern era—the misunderstanding and misappropriation of science, scientific principles and methods, including, especially, Darwinism. Gould added that:

I would alter only Lavoisier’s patrician assumption that ordinary folks cannot master this mode of reasoning—and write instead that most people surely can but, thanks to poor education and lack of encouragement from general culture, do not. . . . But ignorance has always prospered, serving the purposes of demagogues and profit mongers. . . . Moreover, despite a great spread in the availability of education, the favored irrationalisms of the ages show no signs of abatement. (p. 1)

Though we might think of ourselves as exceptional and our society as so advanced and enlightened, have we really come that far? The parallels between our current situation and a faddist intellectual movement of eighteenth century France are striking as well as illustrative. The testing and accountability craze that has taken hold of schooling throughout the so-called developed world (with notable exceptions such as Finland) is no more rational, no more reasoned than the pseudo-scientific movement that mesmerized the French in the late eighteenth Century.

But Laviosier’s is a cautionary tale, especially as regards what Nietzsche might refer to as the truth seeker, or the shepherd, and the herd. During the Reign of Terror in France, Laviosier—the discoverer of oxygen, was hauled before a tribunal, accused by a competitor of “imprisoning Paris and blocking its air circulation through a wall he constructed around the capital” (Mencken 1926/2009, pp. 191–192, fn. 3). Laviosier was sentenced to death by guillotine. He appealed, but the judge denied his appeal, saying that “‘the Republic has no need for scientists’” (p. 192, fn. 3). He was beheaded.

The Power of the Farmers

There is and perhaps always has been and will be a dynamic to the social world, whether we frame it in terms of the push and pull of socio-political forces or the yin and yang of our nature. The way in which we conceive of these types of phenomena, the theories we construct or borrow, the lenses we use with which to see, and the stories or narratives we tell say as much about us as they do about the phenomena ‘out there.’ Lingis (1994) spoke to this when he noted how:

Valuations are gifts of force given to the forces of things. It is with forces, welling up in oneself, that life confronts and opposes, but thereby incites, other forces. The strong sensations, those with which the force of life confronts what comes to encounter it, are not passive affects of pleasure and pain left on life by the impact of things that pass. The strong sensations are those with which an active sensibility greets what comes with laughter and tears, blessing and cursing. The cursing and the tears are themselves forces. (pp. 51–52)

Where some conceive of this dynamism as social Darwinism, Hegel saw a dialectic. Bakhtin (1981) saw centrifugal and centripetal forces at play. Still others saw a dynamic interplay among the state, organized religion(s), and the market (Waite et al. 2007; Wallerstein 2005). Some explain the social world and competing interests in terms of discourses and counterdiscourses (de Certeau 1986), while Rancière (2004, 2010) described the lived social world in terms of the (unequal) distribution of the sensible and its policing.

For Rancière, we are all part of the police order, and politics is that used by those outside of the established order to try to subvert that order [Lingis (1994) might have referred to those outside the police order as the community of those who have nothing in common]. The police and policing are simply the “administration or ‘management’ of society . . . and in particular . . . what is presupposed in all types of administration: ‘the symbolic constitution of the social’” (Rancière 1998, as cited in Simons and Masschelein 2010, p. 591). Simons and Masschelein noted that:

the domain/object of administration does not exist as such, and it is not a natural, pre-existing domain waiting for managerial concern. The domain or object of administration is symbolically constituted although . . . administration acts ‘as if’ it is a natural or given domain (out there) . . . . The administration . . . presents itself as the actualisation of what is the common of a community and . . . transforms the rules for managing into the so-called natural rules of society. (p. 592)

The Kings’ Administrators v. The Outsiders

Still another way to think of this perennial social dynamism is in terms of conflict over competing interests, such as between competing ideologies and/or dogmas (and those who hold them) or between clans, tribes, nation states or commercial concerns. Or we might view societal tension and conflict as stemming from the uneasy interaction of different personality types, two of which Hazony (2012) characterized as the farmers and the shepherds. Hazony dug into Hebrew scripture, read allegorically, to illustrate and illuminate these archetypes: “In the History, the shepherd and the farmer are taken as representing contrasting ways of life, and two different kinds of ethics, which come into sharp conflict time and again” (p. 104). He saw their quintessence in Cain and Abel. Cain was the farmer. Abel was the shepherd.

Cain followed the dicta of his god and his father. He tilled the soil, though it was a hard-scrabble existence, full of woe and misery. The farmer, according to Hazony (2012), submits to the decrees of the gods (and god-kings), exhibits pious sacrifice and self-sacrifice, and honors the customs of past generations. The virtues of “obedience, piety, stability, productivity . . . belong principally to the farmer” (p. 139). The farmer, and later, the manager and administrator, and their labor led to settlements, a certain type of civilization and to the growth of the nation state. The farmer is the backbone of the state. And, “in the ethics of the ancient Near East, all action was ultimately directed toward the maintenance of the state since all goodness was seen as flowing from it. Indeed, whatever served to maintain the closed circle of farmer, tax collector, king, soldier, and priest was on its face for the good” (p. 129). The farmer and the manager are cut from the same cloth.

For Hazony (2012), shepherds and farmers complement one another: the farmer builds great cities and maintains the social order, the shepherd subverts and troubles that order through innovation, dissent and creativity. Apropos our discussion here, we might say that, in school and in schooling, the farmers and their successors have gained control of our schools, their mission and objectives. This is especially true in higher education in the US, where administrators and their staff were predicted to make up more than fifty percent of all higher education personnel by 2014 (Greene et al. 2010; Lewin 2009; Waite and Waite 2010). Managers (read farmers) have bent schooling to serve statist ends, with the state itself having been corrupted and used by business and market interests, in part, through promotion and acceptance of neoliberal ideologies and their attendant processes and policies. This is occurring globally.

Reports are beginning to emerge of the dramatic administrative turn in higher education in the US. Universities in the US are allocating less and less of their resources to instruction and more to administration (Lewin 2009), and students are paying a higher proportion of the costs (Greene et al. 2010; Zernike 2009). In going about their jobs, administrators generate more paperwork and other administrative tasks, not just for themselves and other administrators, but for faculty as well. Faculty and teachers find that responding to administrators’ requests fills more and more of their time. Reichman (2013) reported that the teachers she studied in Israel complained that their jobs were becoming more and more administrative in nature and less pedagogical. Lingis (1994) observed how it is that there are those:

who have an interest in preventing this rather than that from being communicated; they do so by arguing for that, by presenting it in seductive and captivating ways, or by filling the time and the space with it. There are outsiders who have an interest in preventing us from communicating at all. They do so by filling the time and the space with irrelevant and conflicting messages, with noise. (pp. 72–73)

These trends parallel global work trends. In 2011, Arianna Huffington sold the Huffington Post to AOL for 315 million dollars (Carr 2011). The Huffington Post was really nothing but a web portal for bloggers to post their blogs, with links to the actual news stories cited. Few people were employed by the Huffington Post; most posted their work for free. Social and financial commentators asked whether writing online for no pay was worth it (NPR 2011). One commentator suggested that in this new business model we are all serfs now (Carr; de Rosa 2011). de Rosa noted how:

We live in a world of Digital Feudalism. The land many live on is owned by someone else, be it Facebook or Twitter or Tumblr, or some other service that offers up free land and the content provided by the renter of that land essentially becomes owned by the platform that owns the land. (¶ 2)

This same exploitation of the worker, the talent, occurs all over, and threatens to become the norm. Take the music streaming services Pandora and Spotify. Musicians are protesting the pittance these services pay them for playing their songs (NPR 2013), which in some cases equals about $0.004 per play. To cite one example:

Last fall, musician Damon Krukowski wrote a story for the music website Pitchfork about how a song by his ‘80s group Galaxie 500, “Tugboat,” was monetized on Spotify and Pandora. On Pandora, it received 7,800 plays in three months.

“We had earned for that 21 cents—the band had earned that. There are three of us who were in that band and wrote that song together, so we had each earned 7 cents for the quarter for those 7,000-plus plays,” he says. “Spotify pays marginally more. Spotify had played Tugboat 5,960 times, almost 6,000. And for that, we as a band earned $1.05. So that was a whole 35 cents a piece. So we tripled our earnings from Pandora.” (NPR 2013, Comparing Companies, ¶ 1–2)

Lest you think that these are isolated incidents, we have this example involving YouTube, multimedia channels such as Machinima which provide its content, and their artists or workers (Stuart 2013). In one case, Machinima approached Ben Vacas, a successful gamer who had made and posted several short videos on YouTube, offering him a contract wherein Machinima would post ads on his videos and he would receive a small portion of the revenue. Some time later, when he thought he would make and post a short video of his own, Machinima pulled him up short. Too late, he realized the devil’s bargain he had entered into:

he learned that the company would own the rights to whatever videos he posts on YouTube for the rest of his life and beyond, “in perpetuity, throughout the universe, in all forms of media now known or hereafter devised.” Not only that, but his contract with the network was open-ended. There was no point at which it was set to expire. (¶ 9)

Vacas posted a short video, barely more than a minute long, bidding goodbye to his 40,000 YouTube subscribers with a tone of resignation and despair, saying:

I woke up today hoping to make a video, but I went into a call with Machinima this evening and they said that my contract is completely enforceable. I can’t get out of it. . . . They said I am with them for the rest of my life—that I am with them forever. . . . If I’m locked down to Machinima for the rest of my life and I’ve got no freedom, then I don’t want to make videos anymore. (¶ 3–4)

Think of these as cautionary tales, canaries in the coal mine, as indicators of trends in relations between employers and employees, teachers included, as the world becomes more corporativist (Waite 2014).

The same feudal model, where we serfs work the land and the owners (and managers) reap the profit from our labor, is the business model that underpins the likes of Facebook, Google, Amazon.com, the whole digital industry, including internet searches, smart phone and tablet apps and all the rest. Basically, every time you access the internet, use an app or use your mobile phone or tablet, you leave digital bread crumbs behind—these are bits of data, data that when collected, compiled and analyzed, disclose your whereabouts, your preferences, your habits, and more.Footnote 2

These data are vacuumed up, aggregated, analyzed. This is known as Big Data and Big Data means big money (Vega 2013). And the business of Big Data is exploding. Big Data, when complied and subjected to special analytics, become metadata, and metadata can profile your life (Wise and Landay 2013). The uses to which these metadata are put erodes our privacy, and this, in turn, affects our freedom, independence, and our control over our own lives (and data); simply put, these trends severely and negatively affect our autonomy, be we teachers or whomever.

This phenomenon, this change, coincides with an alarming and rapid growth in income inequality in the US and elsewhere (Wilkinson 2005; Reich 2010). This trend is reflected in recent U.S. Labor Department statistics. Recent reports indicate that hourly wages have risen a meager 1.9 percent over the past 2 years (Tell Me More 2013), not enough to keep up with inflation. This, while CEO pay rose “16 percent last year and this year, it’ll probably be even more. The typical pay is a little over $15 million a year for CEOs” (¶ 16).

The median pay for beginning teachers in the US is $35,672Footnote 3, but for workers in other fields:

if you have the right skill sets, this can still be a good economy. For example, . . . petroleum engineers. These are kids right out of school. You’re just finished with your engineering degree. They hand you a sheepskin. Starting salaries are running at about 93,500 [USD] a year. So that’s pretty good for a kid. For Harvard MBAs this year, it’s about $120,000 a year as soon as you get out of school. (Tell Me More, 2013, ¶ 16–17).

Profit-Mongers…

That administrators and administration overshadow teaching and teachers is also reflected in the fact that administrators are the highest paid staff/personnel in K-12 school districts and, aside from some college football coaches, the highest paid personnel in both private and public colleges and universities, and, perhaps, the highest paid state workers all together, including state governors. Many college presidents, public as well as private, have salaries and/or compensation packages topping one million dollars per annum (Lewin 2011), with some making in excess of four million dollars. For example, the ex-president of Ohio State University, having resigned in the wake of his numerous gaffes, was gifted a severance package of 5.9 million dollars over the following 5 years (Austin American-Statesman, July 30, 2013, p. C2), “along with an office, a secretary and a premium parking pass.” The past president of Texas A&M, R. Bowen Loftin, stepped down and, upon doing so, received an $850,000 ‘payout’ (Haurwitz 2013) in an “example of what seems to be a national trend of generous exit packages for higher education leaders” (p. A1). As a faculty member, he will receive a salary of $310,500 a year, plus “$50,000 a year for two years in startup funds for [his] . . . institute, $50,000 a year for three years to use within the . . . department, up to $25,000 for legal and tax advice, and expenses to relocate his library and personal furnishings” (p. A11).

Or if we need further evidence of administrators taking advantage of their privileged position we might consider the large forgivable loans university administrators have given to certain, select faculty and to themselves! (A forgivable loan means that the person receiving the ‘loan’ might never need to pay it back. In effect, it becomes free money.) In the most notable cases, the amounts of these forgivable loans are in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. The University of Texas dean of the law school awarded himself a $500,000 forgivable loan (Hamilton 2012), following a tradition of making forgivable loans to administrators and select faculty that went back at least a decade at the school. At New York University (NYU), administrators (and even former administrators) are routinely given money for housing and more: One administrator, the head of an institute, received $800,000 as annual salary, $1.5 million in mortgages, “of which the university forgave $440,000” (Kaminer 2013, ¶ 13) and administrators “awarded him a $685,000 bonus as he was leaving to take a position at Citigroup” (¶ 2). The current president of NYU, upon stepping down, will receive $800,000 a year.

Critics, however, question such extravagant financial awards and incentives. One, US Senator Charles E. Grassley, noted how universities have non-profit status, exempting them from income and property taxes, saying “‘universities are tax-exempt to educate students, not help their executives purchase vacation homes . . . . It’s hard to see how the student with a life-time of debt benefits from his university leaders’ weekend homes in the Hamptons’” (Kaminer and Delaquérière 2013, p. A19). Another remarked how “‘most faculty find these numbers to be obscene, especially at an institution where adjunct teachers qualify for food stamps’” (Kaminer, ¶ 10).

In effect, faculty have become, or soon will become, serfs and laborers on land owned and managed by the administrators, the farmers. Whatever the individual teacher’s pedagogical orientation, more time will be spent responding to the needs of the state, as interpreted by administrators, and likely less time will be devoted to helping the student learn and grow.

This changes the nature of teachers’ relationships with everyone at work—the students, the administrators, fellow teachers and parents alike. As Lingis (1994) noted:

The servile are those who understand evil . . . . For by evil, they understand nothing else than the very image of those with sovereign instincts, who are felt to be dangerous by their own impotence . . . . The evil one for them is the one who is strong, that is, violent; beautiful, that is, vain; healthy, that is, lascivious; noble, that is, domineering. . . .

The idea of good [for them is] . . . a pale after-effect of their sense of evil. They do not know it in their own instincts and their own joys . . . . In their lips, health means closure from the contagions of the world, beauty means enclosure in the uniforms of serviceability in the herd, goodness means productivity, and happiness means contentment with the content appropriated. (pp. 57–58)

But lest we think that shepherds—instructional coaches and supervisors, maverick principals, and autonomous or semi-autonomous teachers—are somehow above the fray or immune to the issues having to do with communalism and communal responsibility/accountability, we ought to keep in mind Nietzsche’s (1968) observation that “it is not a matter of going ahead (—for then one is at best a herdsman, i.e., the herd’s chief requirement), but of being able to go it alone, of being able to be different” (p. 196, emphasis in original).

Autonomy

Briefly, “autonomy [is] closely related to equity in that a precondition for autonomy is the need to avoid subservience and subordination . . . emphasizing the importance of a sense of control” (Wilkinson 2005, pp. 240–241). Autonomy, freedom and equality are difficult to attain in hierarchical and bureaucratic systems (Waite 2010), built as they are on ranks and rankings.

As organizations grow in size (Shirky 2008), or as someone moves up the hierarchical organizational ladder (Sarason 2004), concern for the organization’s (i.e., the school’s) core mission diminishes—a process known as mission creep or goal displacement. Max Weber (1958) found that, as bureaucracies become established, they grow more concerned with their own survival and self interests. It therefore is unremarkable that organizations become conservative and a conservatizing force, and that their administrators are conservative as well, holding onto, defending, and even promulgating the status quo.Footnote 4 To the degree that administrators act as the disciplinary force for the organization, the school, they limit teachers’ autonomy, freedom, and professional discretion. Teacher autonomy is essential because of the independence it gives teachers—something especially important for service providers and for those receiving their services.

Take medicine. Doctors suffer from a conflict of interest when they receive a salary, a cash bonus, an honorarium, or some other perk or reimbursement from, say, a pharmaceutical company whose pills they prescribe or promote, or when physicians are paid by pharmaceutical companies to be listed as the author of a journal article based on company-generated research, articles which, in reality, are written by ghost writers in the employ of the pharmaceutical companies (Waite 2011; Wilson 2010a, b).

As a patient, I’d prefer being treated by a physician who was concerned about my well-being first and foremost. Students have the right to expect the same of their teachers: that they are not compromised, that their primary concern is the students’ growth and well-being. And lest we forget, teachers teach more than academics. In their role in loco parentis, teachers teach students about life and living.

But it’s not just about teacher autonomy, is it? The teacher is neither totally autonomous nor is this an ideal to be sought. The teacher has a responsibility to the student and to the community, the group. But what is the nature of that responsibility and how might one negotiate autonomy and group membership, obligation and responsibility?

A question relevant to our discussion concerns teaching; that is, how we think of it. Caught up in this question is another that concerns, especially, system-level administrators and policy makers: how do we provide better schooling? How do teachers improve? The answers to these questions are at once pedagogical, epistemological, ontological, developmental and relational.

Tyrants and Kings…

In terms of autonomy, one ideal is that where the individual could negotiate his/her relationship with any and all groups of which s/he is a member and be governed only by her/his consent. Obviously, the larger and more complex the group, the more difficult this is to accomplish (never impossible, simply more difficult). This ideal ignores situations where the group goals supersede or even run contrary to those of the individual, and, vice-versa, where the individuals’ goals, actions or intents run contrary to those of the group. The latter are framed by more autocratic or controlling organizations or groups (and their leaders) as taboos, sins or crimes, and, whole systems of belief and of canonical and legal argument (and education) are developed to norm and discipline (to police, in Rancière’s terms) both the individual and the collective. Groups and organizations elicit or exact some effort toward accomplishing the group goals though varying degrees of persuasion or coercion—salary and bonuses, force, threat of physical or psychological pain, sanction and banishment. This is usually a contractual arrangement, which both parties at least negotiate, and, at best, enter into knowingly, willingly, and freely.

Social and psychological motivation can impel an individual to perform group or organization tasks. These socio-psychological motivations include the need to belong to a group (or society or social entity), and involve issues of membership, affiliation and identity. Different groups or organizations ask different degrees of commitment from incumbents. Coser (1974) wrote of greedy institutions, such as the church and the military, which demand utter commitment and fealty from those it contracts or ‘employs.’Footnote 5 In a similar vein, the sociologist and symbolic interactionist, Erving Goffman (1962), wrote of total institutions such as prisons and asylums.

Other groups are able to engender near total commitment and affiliation, but on a more voluntary basis than do prisons and asylums. Some such groups are formed of those whose devotion, identity and affiliation are driven by fanaticism, far removed from rationality and reason. Examples of these types might include sects (e.g., the Jonestown followers of Jim Jones; the Branch Davidian followers of David Karesh in Waco, Texas) as well as political (of both the left and right) and fundamentalist and extreme religious groups. And though the membership in these groups is more voluntary than in the total or greedy institutions mentioned above, frequently the members are coerced and/or manipulated into joining and staying. In some such groups, leaders prey on members’ personal and psychological fears, weaknesses or debilities.

The relationship of the member to the work group or organization ranges from full autonomy and freedom to utter and complete subservience. The reciprocal give-and-take relationship between the member (teacher or whomever) and the organization is what Billett (2004) referred to as co-participation, “an interdependent process of engagement” (p. 174).

Some of the negative and/or dysfunctional aspects of (some) groups and other communal forms of association include, but are not limited to: nepotism; cronyism; patriarchy; bullying, oppression and marginalization (erasure) of difference (group self-disciplining, censuring, governing/governmentality/managementality, hegemony); and the potential for imperial hubris to emerge in the leader (Waite 2014). Fukuyama (2011) noted how, historically, many of the republican democratic states we hold up as models “were . . . not liberal states but highly communitarian ones that did not respect the privacy or autonomy of their citizens” (p. 20).

Conditions such as external stressors (famine, the Great Recession, ultra-conservative policy environments, etcetera); the structure(s), policies and procedures in place; and the personality of the leader(s) influence how members experience a group, be it a family (Conley 2004), business, or another type of organization (Waite 2010). Bullying, rumor-mongering, and more subtle types of peer pressure are used to discipline and normalize those members framed as deviant (Lipman-Blumen 2005). Shunning and boycotting do this work, too. These disciplining or policing tactics are especially effective in tight-knit or closed communities, slightly less effective in more porous and/or interconnected communities where people have more options. Ostracizing and dismissal are ways that group members and their leaders expel someone from a community, company or other group. (Capital punishment and stoning accomplish the same thing, but by killing, not expelling, the group member.)

Corruption is another negative aspect of groups, organizations, companies and nation-states (Waite and Allen 2003; Waite and Waite 2009). Cronyism, nepotism, and other types of favoritism are closely associated with corruption, each drawing power from and reinforcing the other. Likewise, corruption seems more likely to be exhibited in more communal types of societies or cultures.Footnote 6 Corruption also correlates with GDP (gross domestic production) per capita; which means that poorer countries (as measured per capita) evidence more corruption.Footnote 7 We cannot help but wonder if (and how) these more communal societies produce more corruption owing, perhaps, to patriarchy, fealty to a laird or patriarch, or the rigid and closed social hierarchies (ranks and status) they spawn, the socially-inscribed and formal relationships among people of different ranks and status, especially as demonstrated in the giving of gifts (as rent) and the social bond/reciprocities these rituals engender (with real financial benefits for the superior).Footnote 8 Gift-giving can be used to obligate the recipient, and then becomes a form of bribery (Noonan 1984).

People experience the same groups differently. This depends on many factors, some associated with birth—and the inheritance of whatever cultural capital is available, geography, the social and economic structures one is born into, those one constructs and is able to choose for oneself or those one has foisted upon him or her. For teachers, the school where one works, the state or nation in which it is located, the financial and political milieu, the sociocultural beliefs and expectations about school and schooling that are swirling about, and the leader one finds oneself working with all affect one’s work life. Work and our working environment affect not only what we do, but also affect who we are and who we are becoming. That is, the work one does and the working environment where those tasks are preformed affect the worker’s psyche, personality, self-image, well-being, social status, and more. As the nature of the work changes, it changes the worker. Different kinds of work attract different kinds of people (personality types) and affect the development of the worker’s persona, anima or spirit.

The real question is, then, to what degree are we able to shape our working conditions so that they are more felicitous—healthier, happier, more liberating? And where we control the fruits of our labor? As teachers, we want what many want, what those who precipitated the Arab Spring want: “democracy, dignity, human rights, social equality and economic security” (Hubbard and Gladstone 2013, p. A11).

… and Demagogues

We would be mistaken if we assumed that every educational reform contributes to school improvement. Many do the opposite. Many educational reforms are reactionary measures drawn up in response to some real or imagined ailment or threat. Some are simply the next logical (?) step in an inertia-driven neo-liberal policy agenda. Most of these reforms are neither reasoned nor rational, but leveraged into educational policy by some demagogue or another. Take as an example, the rhetoric accompanying the early positioning in advance of a state-wide election for lieutenant governor of Texas. The chair of the Texas Senate Education Committee, Dan Patrick (R-Houston), pandered “directly to key Republican primary constituencies: conservative parents and tea party activists” (Alexander 2013, p. A1), by suggesting that a curriculum written and disseminated by one of the regional educational service centers diminishes “American and Christian values while promoting socialism and Islam” (A1). He said, “‘there is a war going on right now in this country for the heart and soul of who we are and who we will be . . . . There is a fear that that war has now gone down into the trenches of the classroom’” (p. A5).

But it’s not all lunacy in state capitols and departments of education: there have been signs of moderation, as when, in its last regular legislative session, the Texas legislature, in response to mounting political pressure brought by middle-class parents, reduced the number of the end-of-course exams (EOCs) students must take and pass in order to graduate high school in this state, from 15 to (only!) five.

Data, Magical Thinking, Alchemists and Sorcerers…

The great American satirist, public intellectual and iconoclast, Mark Twain, once said that “there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”Footnote 9 Data and statistics can be used well or poorly and for good or ill; but data are not ever neutral. There are always certain assumptions, acknowledged or implicit, in how research studies are designed, the measures chosen, and how the results are interpreted and used.

Implied in the Twain witticism above is the notion that data can be invoked to settle a question, as the ultimate authority. What and who is given (or usurps) authority in our personal and professional work-a-day lives affects our freedom, our autonomy. The authority that we give to numbers, the values and valuation given them, and the effects that these then have on people’s lives make of the whole process another of the thousand cuts that eat away at teachers, teachers’ psyches, their work and work lives, and their autonomy.

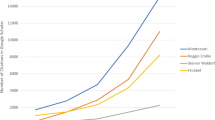

Magical thinking—an anthropological term referring to unscientific or faith-held beliefs in, for example, the power of fetishes to ward off the evil eye or sacrifices to appease angry gods—negatively affects teachers, school and district leaders, even policy makers, and their beliefs and behaviors toward schooling and school improvement. Magical thinking involving numbers is called numerology. Figure 1 shows a dedicated data wall in a Texas middle school with a votive candle placed in front, as though it were some sort of altar.

Magical thinking is but one form of belief or thinking that negatively affects teachers. Others include determinism, excessive (/obsessive) calculation(s), ascribed causality, and substitution of a simpler question for a more complicated one (see Kahneman 2011), though this list is not exhaustive. These all strip the teacher of agency as a human actor in his/her own life, but, in the case of magical thinking, teacher agency is surrendered to whimsical or capricious non-corporeal external agents.

Though most teachers are likely unaware, besides the data that they collect on a daily basis and the mountains of data that they and school administrators collect, many state departments of education in the US contract with data analytic firms to try to catch those whom they construe as test cheaters. One such company is Caveon (Gabriel 2010), which developed and markets what company literature refers to as ‘data forensics’ to oversee standardized testing for, currently, Delaware, Florida, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Washington, Kentucky, Indiana, Massachusetts, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Texas, as well as The College Board, the Atlanta Public Schools and others.Footnote 10 Caveon employs a number of techniques, only some of which involve running an algorithm developed by the company’s founder, which is touted as being able to spot anomalies in reported test data using probability theory, such as an unexplained bump in a school’s scores, or a higher-than-by-chance number of erasures on tests. Those at Caveon then alert state-level school administrators, who may investigate further. Besides the additional time, energy and expense for the school administrators and teachers involved, this type of surveillance and oversight, built on distrust, erodes teacher-administrator relationships, placing the parties on an adversarial footing.

There are those who question, not just the assumption behind this type of oversight, characteristic of a surveillance society, but the mathematics upon which this ‘data forensics’ and its algorithms are built. The New York Times cited professor Walt Hanney and his criticism “that because the company’s methods for analyzing data had not been published in scholarly literature, they were suspect. ‘You just don’t know the accuracy of the methods and the extent they may yield false positives or false negatives’” Gabriel 2010, ¶12–13). Such programs not only catch few ‘cheaters,’ but produce numerous more false positives—which, through allegation and aspersion, damage people’s reputations, and perhaps their work satisfaction, self-concept, and possibly their health.

The charlatans and alchemists, educational reformers among them, have, through sleight of hand and slick rhetoric, convinced many that test scores are a valid measurement in themselves and that they are a proxy for student learning (Waite et al. 2001), just as they have sold many on the belief that ‘data forensics’ can (and should) be used to ferret out test cheating by teachers and/or administrators. Surveillance programs such as these did not head off the corruption and cheating scandals in El Paso, Texas (Fernandez 2012) or Atlanta, Georgia (Winerip 2013), both clients of Caveon. The pressure teachers are under, their individual and collective sense of threat, their vulnerability, and the surveillance methods they are subjected to are more characteristic of a penal system (cf. discussion of Foucault’s use of the panopticon metaphor in, e.g., Lustick, in press), a prison-like atmosphere, than one in which teachers’ agency and professionalism are prized.

Fear Rules the Schoolhouse

Teachers’ work lives are heavily controlled (Ingersoll 2003); controlled and restricted, for instance, in the curriculum and pedagogical decisions they are allowed, in terms of their own governance, and by the processes and structures of their work places. As workers, they suffer diminished dignity and respect as a result of a neo-liberalist-driven degradation in work relations. The Great Recession resulted, in the US, in large numbers of lay-offs (redundancies) in school staff—teachers, aides, and some administrators, as well as school closures. In June of 2013, leaders in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (US) school district “closed 24 schools and laid off 3,783 employees, including 127 assistant principals, 646 teachers and more than 1,200 aides, leaving no one even to answer phones” (Lyman and Walsh 2013, pp. A1 & A12). The issues in Philadelphia are related to financial problems facing the city and state: for example, the urban flight of more affluent parents, which raises the poverty rate in the city and puts a heavier tax burden on those who remain; a Democratic mayor at loggerheads with a Republican governor; and more. But elected officials and government bureaucrats have sought to shore up the city’s finances first, and have only looked to school finances secondly, causing one parent to exclaim:

“The concept is just jaw-dropping,” said Helen Gym, who has three children in the city’s public schools. “Nobody is talking about what it takes to get a child educated. It’s just about what the lowest number is needed to get the bare minimum. That’s what they’re talking about here: the deliberate starvation of the nation’s school districts.” (p. A1)

City and state officials are also seeking salary concessions from teachers, asking them to take a pay cut to help shore up their budgets.

And the dire economic environment, the worsening image of the public schools, and demographic shifts, among other factors, have left some large US urban districts with a population of students that is much more expensive to educate:

The students left behind in some of these large districts are increasingly children with disabilities, in poverty or learning English as a second language.

Jeff Warner, a spokesman for the Columbus (Ohio) City Schools, said that enrollment appears to be stabilizing, but it can be difficult to compete against suburban and charter schools because of the district’s higher proportion of students requiring special education services.

In Cleveland, where enrollment fell by nearly a fifth between 2005 and 2010, the number of students requiring special education services has risen from 17 percent of the student body to 23 percent, up from just under 14 percent a decade ago. . . . (Rich 2012, ¶ 17-19)

The Great Recession has seen teachers become more dependent on their jobs, especially in those families where the other spouse has lost his/her job or in single-parent households. In these cases, teachers, workers, may be willing to endure unsatisfying, even demeaning work and working conditions simply to have a pay check and health insurance benefits.

Teachers find themselves in a bind, squeezed on all sides. But the hazards teachers and school leaders face—the slow erosion of their professional autonomy, their individualism, their liberty—have not been readily apparent, as these changes have been incremental over an extended period of time, ever since educational reform gained traction with the release of A Nation at Risk in 1983.

Of course we would be naïve to think that all teachers are angelic, perfect. Teachers are human. And, as such, they could stand to improve, as do our schools. The issues for us concerning educational reform and school improvement are, as mentioned earlier, what do we expect of teachers and of our schools and under what conditions do teachers do their best work, individually and collectively? Here’s the rub. Due, in part, to the competing ideologies, worldviews, or agendas in the dynamic social tableau discussed above, we’re not of one mind on these issues.

The dominant discourse in the US reflects more of a command and control mentality, making teachers accountable within a rigid and punitive system, and punishing those who fall short, threatening to close (‘reconstitute’) schools, to fire principals and teachers. But this approach, one closely associated with neo-liberal thinking, is simplistic and inadequately addresses the complexities presented. It puts too much weight on the individual for his/her success or ‘failure,’ and that weight falls most heavily on those ‘lower’ in the hierarchy, us serfs. Those at the top aren’t as accountable for their errors or failures (Ingersoll 2003; Waite et al. 2001) and yet they take credit for perceived successes, using these to build resumés and careers, even though only ten percent of the variance between successful and unsuccessful outcomes can be attributed to leadership (Kahneman 2011).

Another type of leadership is exhibited by competitive and more assertive individuals. In the extreme, and left unchecked, what may be positive attitudes and behaviors warp into more sociopathic ones and the too-competitive or too-assertive leader can become the arrogant, narcissistic tyrant, closed off to any negative feedback in his (/her) surroundings (Wagner 2004; Waite 2014). Of course, these behaviors may be exhibited by anyone, but corporatist or corporativist organizations appear to attract, promote and reward these personality types (Lipman-Blumen 2005). Emerging trends in the social world and the world of work set up the corporate system as the model for social organization. Corporativism and consumerism influence our thinking: We can all too easily come to think of those we serve, not as people, but as consumers. And those whom we serve similarly come to view education as a kind of consumer good, concerned not with education for democratic purposes, but judged for the return on investment it affords (Biesta 2010; Gronn 2003).

Corporations value the image they project, no matter what ‘reality’ lies behind it. We refer to this as the brand, or brand name, and to the process as branding. Universities and schools at other levels are re-branding themselves to be more appealing to the student reconstituted as a consumer. Consumer-oriented organizations readily massage the face they show the public, and may even pander to the public in order to garner a better reputation and rise in the rankings, as ranking can affect income and resources. Several prominent universities have been found to game these rankings to keep or obtain more favorable status (Pérez-Peña and Slotnik 2012). Such public relations exercises open the door for charlatans who are adept at gaming the system.

As part of the Affordable Care Act, for example, the US government has instituted a new accountability system for hospitals wherein federal dollars are more closely tied to, among other metrics, patient attitudes (Gorman 2013), causing one hospital administrator to comment “‘it’s not good enough to be the safest or the highest quality [hospital] . . . . You have to connect with people on an emotional level to get them to be loyal’” (p. A7). The Obama administration is looking to implement a similar accountability system for colleges and universities in the US, linking some federal monies to a school’s rankings, some of which will be judged on the income of graduates (Lewin 2013).

Our corporativist thinking, hierarchical and bureaucratic, permits us to anoint and lionize a few, giving them license to take advantage of the many, and to squeeze as much productivity out of them as they can. Such is the pressure cooker that is work today. This is the case not only in the gold mines in South Africa and Chile, but in the sweatshops in Bangladesh, and the electronics plants in China, but throughout the developed world as well. It’s simply a matter of degree, not of kind.

Overconfidence and hubris in the organization’s leaders are constitutive features of neo-liberalism and corporativism (Waite 2014). These characteristic features of organizations today are themselves tied to issues of identity and affiliation: the CEO or whomever begins to believe that he/she is responsible for success. Pay schemes reinforce this. Pay for performance schemes are infiltrating schools and systems to the degree that teachers, principals, and district leaders can earn a bonus if ‘performance targets’ are met or surpassed. Sometimes these bonuses can reach ten thousand dollars or more for an individual teacher (of course, these performance targets are based on student high-stakes test results—a spurious foundation upon which to base decisions about teachers’ compensation and/or their entire careers). No matter that, in business, huge pay packages do not correlate with the actual performance of either the company or company stock (Fukuyama 2011; Marketplace, 2001, as cited in Waite and Allen 2003). That is, even as stock prices tumbled, or companies laid off large numbers of workers—both measures of company performance, CEO salaries and bonuses continued to climb.

Just as not every school reform contributes to school improvement, not every leader does good work (Gardner et al. 2001). Some do some pretty nasty things (Lipman-Blumen 2005; Waite 2014; Waite and Allen 2003); some do ‘dirty work’ (Hughes 1971). Examples of this can be found in the disgraced former Atlanta school superintendent, Beverly Hall (Winerip 2012)—who was said to rule by fear; or the superintendent of schools from El Paso, Texas who was recently convicted of fraud and sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison. He and his principal-accomplices ‘disappeared’ large numbers of students whom they thought might bring down the school test scores (Llorca 2012). (Teachers in these schools reported that they thought that test doctoring was part of their job.) Or there are principals who threatened to put their entire staff on professional growth plans if school test scores didn’t rise (F. Casteel, personal communication, April 8, 2013). We also have untold numbers of district and school administrators and teachers who game the system however they can, seeing it for what it is—a senseless and crazy system; that is, unless they unreflectively accept its assumptions and methods and their consequences.

Concluding Thoughts

All of these forces—from the macro to the micro—impinge on teachers and their teaching. So much so, that the heart and soul of the profession is at stake. In our struggle to educate, to teach, we might take inspiration from the shepherd, who, according to Hazony (2012):

observes and evaluates all that goes on in human life from a perspective that is outside the political state and free of any prior commitment to it. . . . [The shepherd’s] ethics begin with a view of the human being—or, to be more precise, with the human family—as being independent of the state. . . . When the state cannot or does not serve this end, the state and its laws cease to have a claim on the individual. So far as he [/she] is concerned, they no longer have any reason to exist at all. (p. 133, emphasis in original)

Nietzsche (1968) posed a similar challenge for us. Once we have recognized that there is a problem, we cannot refuse to see, we cannot not see. What can we do?

You run ahead? Are you doing it as a shepherd? Or as an exception? A third case would be the fugitive. First question of conscience . . . .

Are you genuine? Or merely an actor? A representative? Or that which is represented? In the end, perhaps you are merely a copy of an actor. Second question of conscience . . . .

Are you one who looks on? Or one who lends a hand? Or one who looks away and walks off? Third question of conscience . . . .

Do you want to walk along? Or walk ahead? Or walk by yourself? One must know what one wants and that one wants. Fourth question of conscience. (p. 472, emphasis in original)

Or we might find inspiration and a kind of road map in the words of the great American poet, Walt Whitman, who, in the preface to the first edition of Leaves of Grass (Whitman 1885), offered this advice:

This is what you shall do: Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves [pages] in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul; and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body. (¶ 2)

Acting courageously in this way we must be ever alert to charlatans and those others who would attempt to turn our love and longing for human fulfillment into taking up their reforms. We must expose the charlatans and demagogues, profit-mongers and the rest. We must scrutinize even the most popular of reformers, for the herd is easily swayed by celebrity and by the ‘research says’ academics, the ‘brain-based,’ ‘what works’ and ‘best practices’ purveyors of reform. Locally-produced, thoughtful responses to immediate educational problems and situations, while not sexy, slick and seductive, are likely to be the best, most appropriate educational reforms we can find. We must rise to the challenge. It is our responsibility as teachers and as educators.

Notes

“Kool-aid-drinking” is a colloquial term, a vestige of the murder-suicide precipitated by Jim Jones, an erstwhile religious cult leader, in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978, when he convinced his followers to drink poison-laced Kool-aid. Nearly one thousand people died as a result.

These data bits can and have been used, through analysis, analytics, and assignment of probability, to profile you: who your ‘friends’ are, what their preferences are, what your political leanings are, your gender and even your sexual orientation (are you gay or straight), and more.

Entry-level teachers in the US can earn anywhere from $30,000 to $50,000, depending on where they are employed (National Education Association, http://www.nea.org/home/2011-2012-average-starting-teacher-salary.html).

As an example, in Egypt the state bureaucracy is referred to as ‘the deep state,’ and widely acknowledged as being a formidable impediment to any type of change (McEvers 2013).

Two friends of mine, one who served as a US Marine and the other as a Catholic priest, have each told me separately that there is no such thing as a ‘former priest’ or, the other, that there is no such thing as a ‘former marine’: once a marine, always a marine. This speaks to a high degree of indoctrination and of personal, psychic attachment (and identification).

See http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2012/results/ for Transparency International’s 2012 Corruption Perception Index.

There is, to the contrary, ample historical evidence of smaller communal groups, often more hunter-gathers or of a subsistence-level economy, that have, in today’s terms, a flatter organizational structure and enjoy more egalitarian relationships among the members (Wilkinson 2005); so a tendency toward corruption may be a function of hierarchy and the size of the group, community or country. Patriarchy and culture almost certainly play a role; but just what their part is, we can’t say at this time.

Compare Transparency International’s index (fn 6 above) with per capita figures, for example: http://www.econguru.com/heat-map-of-worldwide-gdp-ppp-per-capita-2008/.

A quick (virtual) tour of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul and the treasury of the Ottoman sultans provides ample evidence for my assertions about gifting in social hierarchies. A representative sample can be seen on this YouTube video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=if0ohSTZorQ.

References

Alexander, K. (2013). Election focus turns to CSCOPE. Austin American-Statesman, August 2, 2013, A1 & A5.

Ariely, D. (2013). The (honest) truth about dishonesty: How we lie to everyone—especially ourselves. New York: Harper Perennial.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. (M. Holquist Ed., C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Billett, S. (2004). Co-participation at work: Learning through work and throughout working lives. Studies in the Education of Adults, 36(2), 190–205.

Carr, D. (2011). At media companies, a nation of serfs. The New York Times, February 12, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/14/business/media/14carr.html?_r=1&src=busln

Conley, D. (2004). The pecking order: Which siblings succeed and why. New York: Pantheon Books.

Coser, L. A. (1974). Greedy institutions: Patterns of undivided commitment. New York: The Free Press.

de Certeau, M. (1986). Heterologies: Discourse on the other (B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

de Rosa, A. (2011). The death of platforms. Soup, January 17, 2011. http://soupsoup.tumblr.com/post/2800255638/the-death-of-platforms

Dillon, S. (2010). School reform draws crowd, not credentials. The New York Times, August 10, 2010, A1 & 11.

Fernandez, M. (2012). El Paso rattled by scandal of ‘disappeared’ students. The New York Times, October 13, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/14/education/el-paso-rattled-by-scandal-of-disappearedstudents.html?pagewanted=all

Fukuyama, F. (2011). The origins of political order: From prehuman times to the French revolution. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gabriel, T. (2010). Cheaters find an adversary in technology. The New York Times, December 27, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/28/education/28cheat.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Gardner, H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Damon, W. (2001). Good work: When excellence and ethics meet. New York: Basic Books.

Goffman, E. (1962). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Chicago: Adline Publishing Company.

Gorman, A. (2013). Happy patients now mean more cash for hospitals. Austin American-Statesman, August 18, 2013, A7.

Gould, S. J. (1989). The chain of reason versus the chain of thumbs. Natural History, 98(7), 12–18.

Greene, J. P., Kisida, B. & Mills, J. (2010). The higher price for higher ed. Austin American-Statesman, September 7, 2010, A6.

Gronn, P. (2003). The new work of educational leaders. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Hamilton, R. (2012). UT law’s forgivable loans to faculty ‘not appropriate.’ The Texas Tribune, November 13, 2012. http://www.texastribune.org/texas-education/higher-education/ut-law-forgivable-loan-program-deemed-not-appropri/

Haurwitz, R. K. M. (2013). A&M head’s $850,000 payout part of U.S. trend. Austin American-Statesman, August 24, 2013, A1 & A11.

Hazony, Y. (2012). The philosophy of Hebrew scripture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hubbard, B., & Gladstone, R. (2013). Arab spring countries find peace is harder than revolution. The New York Times, August 15, 2013, A11.

Hughes, E. C. (1971). Good people and dirty work. In E. C. Hughes (Ed.), The sociological eye: Selected papers. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Huyssen, A. (1987). Foreword :The return of Diogenes as postmodern intellectual. In P. Sloterdijk (Ed.), Critique of cynical reason (pp. ix–xxxix). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2003). Who controls teachers’ work? Power and accountability in America’s schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kaminer, A. (2013). More than one N.Y.U. star got lavish parting gift. The New York Times, March 3, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/nyu-gives-lavish-parting-gifts-to-some-star-officials.html?_r=0

Kaminer, A., & Delaquérière, A. (2013). N.Y.U. gives stars loans for summer homes. The New York Times, June 18, 2013, pp. A1 & A19.

Lewin, T. (2009). Staff jobs on campus outpace enrollment. The New York Times, April 21, 2009, A12.

Lewin, T. (2011). Private-college presidents getting higher salaries. The New York Times, December 5, 2011, A17.

Lewin, T. (2013). Obama’s plan aims to lower cost of college. The New York Times, August 22, 2013, A1 & A16.

Lingis, A. (1994). The community of those who have nothing in common. Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press.

Lipman-Blumen, J. (2005). The allure of toxic leaders: Why we follow destructive bosses and corrupt politicians—and how we can survive them. New York: Oxford University Press.

Llorca, J. C. (2012). Former El Paso school chief gets over 3 years in test scandal. Austin American-Statesman, October 5, 2012. http://www.statesman.com/news/news/state-regional-govt-politics/former-el-paso-school-chief-gets-over-3-years-in-t/nSWSJ/

Lopez, S., & Sidhu, P. (2013). U.S. teachers love their lives, but struggle in the workplace. Gallup Wellbeing, March 28, 2013. http://www.gallup.com/poll/161516/teachers-love-lives-struggle-workplace.aspx

Lustick, H. (in press). Administering discipline differently: A Foucauldian lens on restorative school discipline. International Journal of Leadership in Education.

Lyman, R., & Walsh, M. W. (2013). A city borrows so its schools open on time. The New York Times, August 16, 2013, pp. A1 & A12.

McEvers, K. (2013). Conspiracy or bureaucratic neglect in Egypt? National Public Radio, July 22, 2013. http://www.npr.org/2013/07/22/204580866/conspiracy-or-bureaucratic-neglect-in-egypt

Mencken, H. L. (1926/2009). Notes on democracy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. (Reprinted by Dissident Books, New York, 2009).

MetLife. (2013). The MetLife survey of the American teacher. https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/foundation/MetLife-Teacher-Survey-2012.pdf

Nietzsche, F. (1968). The will to power. (W. Kaufmann & R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

Noonan, J. T. (1984). Bribes. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company.

NPR. (2011). Is writing on line without pay worth it? National Public Radio, February 15, 2011. http://www.npr.org/2011/02/15/133759724/is-writing-online-without-pay-worth-it.

NPR. (2012). The ‘truth’ about why we lie, cheat and steal. National Public Radio, June 4, 2012. http://www.npr.org/2012/06/04/154287476/honest-truth-about-why-we-lie-cheat-and-steal.

NPR. (2013). Paying the piper: Music streaming services in perspective. National Public Radio, July 28, 2013. http://www.wbur.org/npr/205873218/paying-the-piper-criticism-of-music-streaming-services-in-perspective.

Pérez-Peña, R., & Slotnik, D. E. (2012). Gaming the college rankings. The New York Times, January 31, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/01/education/gaming-the-college-rankings.html

Rancière, J. (2004). The politics of aesthetics. (G. Rockhill, Trans.). London: Continuum.

Rancière, J. (2010). Dissensus: On politics and aesthetics. (S. Corcoran, Trans.). London: Continuum.

Reich, R. B. (2010). Foreword. In R. Wilkinson & K. Pickett (Eds.), The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Reichman, R. (2013, May). New directions in teachers’ professional development following the national “New Horizon” reform. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the (Israeli) National Conference on Educational Leadership and Administration, Haifa, Israel.

Rich, M. (2012). Enrollment off in big districts, forcing layoffs. The New York Times, July 23, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/24/education/largest-school-districts-see-steady-drop-in-enrollment.html?pagewanted=all

Sarason, S. B. (2004). And what do YOU mean by learning?. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Shirky, C. (2008). Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations. New York: The Penguin Press.

Simons, M., & Masschelein, J. (2010). Governmental, political and pedagogic subjectivation: Foucault with Rancière. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 4, 588–605.

Stuart, T. (2013). YouTube stars fight back. LAWeekly, January 10, 2013. http://www.laweekly.com/2013-01-10/news/machinima-maker-studios-YouTube/full/

Tell Me More. (2013). Jobs have been added, but why are wages stubborn? National Public Radio, August 2, 2013. http://www.npr.org/2013/08/02/208259656/jobs-have-been-added-but-why-are-wages-stubborn

Vega, T. (2013). Two ad giants in merger deal, chasing Google. The New York Times, July 29, 2013, pp. A1 & A3.

Wagner, R. K. (2004). Smart people doing dumb things: The case of managerial incompetence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Why smart people can be so stupid (pp. 42–63). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Waite, D. (2010). On the shortcomings of our organizational forms: With implications for educational change and school improvement. School Leadership and Management, 30, 225–248.

Waite, D. (2011). Universities and their faculties as ‘merchants of light’: Contemplation on today’s university. Education and Society, 29, 5–19.

Waite, D. (2014). Imperial hubris: The dark heart of leadership. Journal of School Leadership, 24(6), 1202–1232.

Waite, D., & Allen, D. (2003). Corruption and the abuse of power in educational administration. Urban Review, 35, 281–296.

Waite, D., Boone, M., & McGhee, M. (2001). A critical sociocultural view of accountability. Journal of School Leadership, 11, 182–203.

Waite, D., Moos, L., Sugrue, C., & Liu, C. (2007). Framing education: A conceptual synthesis of the major social institutional forces affecting education. Education & Society, 25, 5–33.

Waite, D., Rodríguez, G., & Wadende, A. (2015). The business of educational reform. In J. Zajda (Ed.), Second international handbook of globalisation, education and policy research (pp. 353–374). The Netherlands: Springer.

Waite, D., & Waite, S. F. (2009). On the corruption of democracy and education. In P. Jenlink (Ed.), Dewey’s democracy and education revisited: Contemporary discourses for democratic education and leadership (pp. 297–324). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Waite, D., & Waite, S. F. (2010). Corporatism and its corruption of democracy and education. Journal of Education and Humanities, 1(2), 86–106.