Abstract

This study retrospectively investigated the effect of breed and season on the lambing/kidding dynamics, growth performance, neonatal viability, and weaning dynamics of sheep (Damara, Dorper, and Swakara) and goats (Boer goat and Kalahari Red) at a farm in the Khomas Region of Namibia between 2004 and 2015. Litter size was dependent on breed (X2(12, N = 3388) = 796, p < 0.001), with twinning more frequent in Dorper sheep and Kalahari Red and Boer goats than in the Damara and Swakara sheep (p < 0.05), while triplets were more prevalent in the Dorper sheep and Kalahari Red goats (2.8% and 1.0%, respectively; p < 0.05). Distribution of birth weight categories was dependent on breed. There was a significant difference in the proportions of birth weight categories between breeds (X2(12, N = 3388) = 467, p < 0.001) whereby Dorper lambs were mostly born weighing below 3 kg (2.6%, p < 0.05); Boer goat kids, Kalahari Red kids, and Damara lambs were mostly born weighing 3 to < 4 kg (4.3%, 6.3% and 19.9%, respectively; p < 0.05); Swakara lambs were mostly born weighing 4 to < 5 kg (12.2%, p < 0.05), and Swakara lambs were mostly born weighing ≥ 5 kg (3.3% and 2.3%, respectively, p < 0.05). Weaning age categories were dependent on breed (X2(12, N = 3388) = 241, p < 0.001) whereby Dorper lambs were mostly weaned at below 3 months of age (2.8%, p < 0.05); Damara lambs were mostly weaned at 3 to < 5 months of age (12%, p < 0.05), and Boer goat kids were mostly weaned at ≥ 5 months of age (0.9%, p < 0.05). Neonatal viability was dependent on breed (X2(8, N = 3388) = 49.2, p < 0.001) whereby Dorper lambs were more susceptible to abortions and neonatal deaths (0.6% and 1.5%, respectively; p < 0.05) than the rest of the breeds. Breed and lambing season interacted to produce effects on the birth weight of offspring although lambing season alone did not have a significant effect on Boer goat and Kalahari Red kids’ birth weights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sheep and goats are an important source of income in many commercial and communal farm enterprises in the tropics and sub-tropics (Dadi et al. 2008; Gökçe and Atakışİ 2019; Hasan et al. 2015). Small stock production is popular in arid countries such as Namibia because they mature very rapidly and are a major source of survival and assets for the landless and poor since they are relatively cheap to buy. They utilize a wider diversity of plants and do not compete for forage with cattle. As browsers, they use different vegetation than cattle and thus allow farmers to make more efficient use of the available natural resources. They have very wide climatic adaptation and thrive well in dry areas where feed resources are limited (Erasmus 2000; Silanikove et al. 2000).

It has been predicted that small ruminants will provide 50% of red meat in Sub-Saharan Africa by the year 2025 (Winrock International 1992). In Namibia, small ruminant production comprises approximately 2,055,848 (57%) sheep (Dorper, Damara, Swakara) and 1,624,834 (43%) goats (mainly Boer goat) produced commercially in the southern and western parts of the country and through subsistence farming in the north of the country (De Lange 2008; Mushendami et al. 2008; Namibia Statistics Agency 2015a, b).

According to the Namibian Livestock Sector Strategy, prior to 2006, most of the sheep and nearly all the goats were exported to South Africa on hoof (Anon 2011). In 2006, the Government came up with a “Growth at Home” strategy discouraging export of live animals in favour of local slaughter. Consequently, local demand for lamb has since increased (Anon 2011). Though the demand for chevon and cabrito cuts in formal markets was previously depressed, recent years have witnessed an upsurge of demand from urban centres (Casey and Webb 2010). The increased demand for small ruminant meat has placed a strain on traditional small ruminant production systems, thus challenging the systems to produce more meat on diminishing land resources. This scenario has necessitated active research into increased small ruminant meat production from current flocks raised in smaller and otherwise less productive land (Casey and Webb 2010). Reproductive performance, pre-weaning growth performance, and the survival of kids/lambs all form the basis of such improvements in productivity (Abdelqader et al. 2017; Chay-Canul et al. 2019; Đuričić et al. 2019; Topal et al. 2017).

Reproductive performance and pre-weaning growth performance (Duričić et al. 2012; Hasan et al. 2015; Kleemann et al. 2016; Tungu et al. 2017) are influenced by animal (birth weight, litter size, breed, parity, and sex), environmental (season and year of birth), and management (production system, maternal nutrition, health, consumption of colostrum) factors (Fasae et al. 2012; Gaafar et al. 2011; Gökçe and Atakışİ 2019; Hoffman et al. 2017; Sánchez-Dávila et al. 2015). Birth weight is also influenced by an interplay of several factors including breed, sex, litter size, parity, and maternal nutrition and affects weaning weight (Behrendt et al. 2019; Chniter et al. 2013; Fasae et al. 2012; Sánchez-Dávila et al. 2015). Kids/lambs of some breeds are born heavier than others; kids/lambs born in bigger litters are lighter than singletons; and nutrition of the dam negatively affects pre-weaning growth performance through reduced levels of circulating growth and other metabolic hormones (Loureiro et al. 2016). Gestations carrying male foetuses are generally longer and thus result in heavier neonates than those carrying female foetuses (Gaafar et al. 2011; Hoffman et al. 2017). Space and nutritional constraints imposed on foetuses in utero limit future productivity of the offspring by limitations imposed, in utero, on stem cell numbers through a phenomenon known as developmental programming (Greenwood et al. 2017; Hoffman et al. 2017; Samkange et al. 2019).

Pre-weaning mortality is a major factor limiting the economic viability of small ruminant enterprises with implications on farmer morale and animal welfare (Balta and Topal 2018; Dadi et al. 2008; Dwyer et al. 2016). The causes, extent, determinants, and solutions of pre-weaning lamb/kid mortality have been investigated under experimental and field conditions (Doaa et al. 2009; Gowane et al. 2018; Hagan et al. 2014). There are animal (Juengel et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2006; Snyman and Olivier 2002; Swarnkar et al. 2019), environmental (Abdelqader et al. 2017; Dadi et al. 2008; Doaa et al. 2009; Đuričić et al. 2019; Mustafa et al. 2014; Topal et al. 2017), and management factors (McCoard et al. 2017; McGregor 2016; Raoof 2018) responsible for kid/lamb survival. The causes of pre-weaning mortality include infectious and non-infectious conditions of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and nervous systems that are associated with low birth weight and poor early health performance (Mukasa-Mugerwa et al. 2000; Petros et al. 2014; Snyman 2010). Common specific infectious conditions include septicaemia, diarrhoea, pneumonia, and endoparasites (Chikwanda et al. 2013; Khan et al. 2006; Swarnkar et al. 2019). The non-infectious conditions include low birth weight, lameness, predators, starvation-mis-mothering complex, birth stress, trauma, and hypothermia (Abdelqader et al. 2017; Gokce and Erdogan 2009; Kandiwa et al. 2018; Mukasa-Mugerwa et al. 2000; Petros et al. 2014; Snyman 2010).

The factors affecting lamb/kid productivity have been thoroughly investigated globally, in Africa and in the southern African sub-region. Traditionally, these factors have been investigated separately in sheep and goats. To the best of our knowledge, comparison of different small ruminant species and breeds (lambs and kids) has not previously been done in the same study. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare the production performance of different breeds of kids/lambs born and raised under similar conditions at a farm in the Khomas Region of central Namibia. It was hoped that the results of this study would inform farmers of the best small ruminant species and breeds to adopt under production conditions similar to those in central Namibia.

Materials and methods

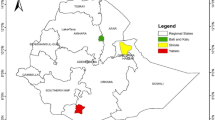

The study was carried out at a farm located at the coordinates 22° 31′ 0″ S and 17° 15′ 0″ E in the Khomas Region of Namibia about 40 km east of Windhoek. The farm lies at 1963 m above sea level and occupies 10,187 ha of land dominated by shrub-veld Savannah vegetation. Between 300 and 400 mm of rainfall occurs annually from November to April.

Study animals

The Swakara, Dorper, and Damara lambs, Boer goat, and Kalahari Red kids born since 2004 until 2017 at the farm constituted the study animals. Sheep and goats from each breed were reared in the same paddocks. Deworming, dipping, vaccinations, disease diagnoses, and treatments were performed following the established farm protocol. Female and juvenile animals were allowed to graze extensively in designated rotational paddocks during the wet and dry seasons, but rounded up every night into protected sheds to deter losses through predation. Pellets and lucerne hay were used for supplementation during the dry seasons, and urea blocks were maintained in the paddocks all year round. For breeding purposes, selected males were introduced into paddocks with selected females to prevent inbreeding and cross-breeding. Clean borehole water was provided ad libitum at designated water points throughout all the paddocks. February to March and July to August were the designated annual lambing/kidding seasons at Neudamm farm.

Statistical analysis

The data was collected from farm records and collated on Microsoft Excel 2013 from which pivot tables were created for the designated categories: lamb/kid sex, birth weight, offspring/dam, viability of offspring, weaning weight, and weaning age. Pearson’s chi-square with an alpha level of 0.05 was used for comparison of the number of animals within these categories. Adjusted residual post hoc tests with adjusted significant levels were used to further test significant chi-square results. Two-way ANOVA with replication was used to test for the significance (p < 0.05 was considered significant) of the effect of breed or season and the interaction thereof. The z test for comparison of proportions was also used for overall comparison of proportional distribution of birth weight categories between breeds. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 was used for data analyses.

Results

As shown in Table 1, more Damara lambs, followed by the Dorper, Swakara, Kalahari Red kids and least of all Boer goat kids (36.2%, 30.7%, 20.2, 7.6%, and 5.3%, respectively) were born at the farm during the study period (z = 4.87, p < 0.0001). Overall, more female (51.1%) than male (48.9%) animals were born (z = 1.8, p = 0.07), although this was statistically insignificant. There was no difference in the proportions of males to females between the breeds of animals born during this period (X2(4, N = 3388) = 2.69, p = 0.61).

There was a significant difference in the proportions of offspring/dam between breeds (X2(12, N = 3388) = 796, p < 0.001). The proportions of the Damara and the Swakara singlet lambs delivered (25.8% and 19.8%, respectively) were greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportions of the Dorper, the Boer goat, and Kalahari Red twins (13.9%, 4.4%, and 3.4%, respectively) were greater than those of the Damara and the Swakara (p < 0.05). The proportions of Dorper and Kalahari Red triplets were greater than those of the rest of the breeds (p < 0.05). There was, however, no significant difference in the proportions of the quadruplets between breeds (p > 0.05).

Proportions of birth weight categories were different between breeds (X2(12, N = 3388) = 467, p < 0.001). The proportion of the Dorper lambs under 3 kg birth weight (2.6%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportions of Boer goat kids, Kalahari Red kids, and Damara lambs weighing 3 to < 4 kg at birth (4.3%, 6.3%, and 19.9%, respectively) were significantly greater than those of the Swakara and the Dorper (p < 0.05). The proportion of Swakara lambs weighing 4 to < 5 kg at birth (12.2%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportions of Dorper and Swakara lambs weighing ≥ 5 kg at birth (3.3% and 2.3%, respectively) were significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05).

Weaning age categories were significantly different between breeds (X2(12, N = 3388) = 241, p < 0.001). The proportion of Dorper lambs weaning at below 3 months of age (2.8%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Damara lambs weaned in the 3- to < 5-month category (12%) was significantly greater than those of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Boer goat kids weaned at ≥ 5 months of age (0.9%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Dorper lambs weaned at unknown age (22%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05).

Proportional occurrence of weaning weight was significantly different between breeds (X2(12, N = 3388) = 285, p < 0.001). The proportions of Boer goat kids (0.6%) and Kalahari Red kids (0.8%) weaned at below 15 kg live weight were significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Damara lambs weaned at the 15- to < 25-kg weight category (10.4%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Dorper lambs weaned at ≥ 25 kg (4.6%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Dorper lambs weaned at unknown weight (22.1%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05).

Overall, proportional viability of neonates was different between breeds (X2(8, N = 3388) = 49.2, p < 0.001). The proportions of Dorper lambs that were aborted (0.6%) and died as neonates (1.5%) were significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05). The proportion of Damara lambs that survived the neonatal period (35.4%) was significantly greater than those of the rest of the other breeds (p < 0.05).

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant difference in the proportions of birth weight categories between seasons (X2(27, N = 3388) = 608, p < 0.001). Two-way analysis of variance showed that the proportion of winter-born Dorper and Swakara weighing < 3 kg at birth was greater than those of the summer-born Dorper (1.6% and 1%, respectively; p < 0.001) and Swakara lambs (0.6% and 0.2%, respectively; p < 0.01) within the same birth weight category. The proportion of winter-born Damara weighing 3 to < 4 kg at birth was greater than that of the summer-born Damara lambs within the same birth weight category (10.7% and 9.2%, respectively; p < 0.001). The proportion of summer-born Damara weighing 4 to < 5 kg at birth was greater than that of the winter-born Damara lambs within the same birth weight category (9.3% and 3.6%, respectively; p < 0.001). There was no significant seasonal effect on the Boer goat and Kalahari Red kids’ birth weight (p > 0.05). The proportion of offspring born weighing ≥ 5 kg was not affected by lambing season alone though, however, lambing season interacted with breed to produce significant effects.

Discussion

The results from this study showing that an overall majority of births (63.5%) were singleton births also show a significant difference in litter size between breeds (Table 1). The preponderance of singletons in the Damara and Swakara is in agreement with reports from other studies on the same breeds (Näsholm and Eythorsdottir 2011; von Wielligh 2003) whereby 80.5% singleton and 19.5% twin births were reported in Damara sheep (von Wielligh 2003). Findings of more twinning from Boer goats in this study are also in agreement with those from previous studies (Almeida 2011; Campbell 2003; Lehloenya et al. 2005) which, however, also reported substantial proportions of triplets and quadruplets (Erasmus 2000). Inferences regarding occurrence of quadruplets in the current study were inconclusive due to insufficient data. Considerable numbers of triplets has also been reported in Dorper sheep (King 2009).

The findings from the current study that 95.3% of the births were over 3 kg is well-substantiated by other earlier studies although the rather greater proportion of Dorper lambs weighing below 3 kg is not supported in these studies (Alemseged and Hacker 2014; Schoeman and Burger 1992).This greater proportion of underweight lambs by Dorper standards may have resulted from the greater proportions of twins and triplets in the current study. A number of studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between birth weight and litter size (Balta and Topal 2018; Chay-Canul et al. 2019; Hagan et al. 2014). The current finding whereby the greatest proportions of Damara lambs weighed 3 to < 4 kg was contradictory to findings by another author, whereby female and male Damara lambs weighed 4.2 kg and 4.5 kg, respectively (Du Toit 1995). This discrepancy may have been due to the age, parity, weights, and nutrition of the mothers of these lambs as well as the seasons of birth (Deligiannis and Lainas 2000; Petros et al. 2014; Sánchez-Dávila et al. 2015). The ages and parities of the dams were, however, not determined in the current study. The current finding of a significantly greater proportion of Swakara lambs weighing 4 to < 5 kg can be explained by the inverse relationship between litter size and birth weight since the Swakara had the lowest proportion of twin and triplet births. The greater proportions of Dorper and Swakara lambs weighing ≥ 5 kg are possibly to the fact that a majority of the Dorper and Swakara lambs were singleton births.

The high birth weights in this study can be attributable to the high level of management practised at the farm. According to the farm manger Edmund Beukes, it is farm policy to have a very high selection intensity for small ruminants. Only the top 15% is selected for replacement stock. In addition, every year, the farm purchases the best rams for introduction of improved genetics from the auctions and to prevent inbreeding depression. The lambs receive creep feed as soon as they can eat solid food. Breeding rams and bucks are given supplementary lucerne, hay, and pellets 3 weeks before breeding, during breeding and up to a week after the 35-day breeding season. Breeding ewes are also supplemented with lucerne, hay, and special ram, lamb, and ewe pellets to enable them to produce more milk for the offspring. Additional feed is given for each multiple birth. The farm is also very strict with primary health care policy, and animals are vaccinated and dewormed according to a very strict protocol.

Due to their well-documented high average daily gain (Von Seydlitz 1996), a significantly greater proportion of Dorper lambs from the current study were weaned at less than 3 months of age. Greater proportions of Damara lambs and Boer goat kids were weaned at 3 to < 5 months and ≥ 5 months of age, respectively. Findings of significantly greater proportions of Boer goat and Kalahari Red kids being weaned at below 15 kg are contradictory to those from other studies reporting the bulk of Boer goat kids weaning at 20–29 kg after 4 months, a proof of better pre-weaning performance in comparison with Damara and Dorper lambs (King 2009; von Wielligh 2003). The reported average daily gain (ADG) of the Boer goat varies widely from 129 to 240 g/day depending on the litter size, production system, and whether or not they receive supplementary feeding (Barry and Godke 1997; King 2009).

The current study found that a significantly greater proportion of Damara lambs were weaned at 15 to < 25 kg, which is in agreement with another study which reported an average weaning weight of 19.8 kg for the same breed (Almeida 2011). The significantly greater proportion of Dorper lambs weaned at ≥ 25 kg in the current study is in agreement with that of other studies where ADG of 240–280/day in Dorper lambs were reported (Kleemann et al. 2000; Schoeman and Burger 1992). Curiously, the Dorper sheep had the greatest proportion that was weaned at unknown weight. The inference that the farmer may be growing more confident with this breed is a tempting explanation here.

The low pre-weaning mortality rate of 4% obtained in this study was a remarkable feat. Reported pre-weaning mortality rates varied from as low as 1.79% (Swarnkar et al. 2019) through 3–10% (Atashi et al. 2013; Chauhan et al. 2019) to 11–19.7% (Abdelqader et al. 2017; Elia 2018; Khan et al. 2006; Mustafa et al. 2014; Snyman 2010). The significantly high average birth weight (95.3% of all offspring were > 3 kg), small litter size (63.5%, singleton births), and predominantly summer lambing/kidding (59.66%) are all possible explanations for the rather low mortality rate. Lamb survival has often been positively associated with higher birth weight and single-born lambs than with multiple-born lambs (Aldridge et al. 2015; Hebart and Brien 2018; Juengel et al. 2018). Reports on the effect of season on neonatal viability are conflicting at best. Higher neonatal mortalities have been reported in kids/lambs born in both winter (cold and dry) and summer months (hot and wet) (Belay and Haile 2011; Deligiannis and Lainas 2000; Kandiwa et al. 2018).

The physical and metabolic limitations placed on multiple born offspring during gestation resulting low birth weight and subsequent suboptimal postnatal growth performance deserves special mention. Such kids/lambs are born with low rectal temperatures, low levels of glucose, plasma protein, cholesterol, and growth hormone, which could limit the speed at which the offspring reaches the udder to suckle (Chniter et al. 2013; Dwyer et al. 2016; Kenyon et al. 2019; Plush 2013). The metabolic pathways of these kids/lambs are still largely immature (Plush 2013), consequently preventing rigorous suckling that provides fuel for the adjustment to early life and facilitates bonding with their mothers to increase chances of survival. These lambs/kids fail to consume sufficient quantities of colostrum to enable them to fight diseases (Chniter et al. 2013; Dwyer et al. 2016; Gökçe and Atakışİ 2019), and significant numbers of them face certain death. High levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) has been associated with lower levels of mortality in sheep (Khan et al. 2006). Pre-weaning mortality has been reported to be higher in males than in females (Doaa et al. 2009; Mustafa et al. 2014; Snyman 2010). According to one study, mis-mothering that occurs when many does kid at the same time, was the single most important cause of kid mortality (Petros et al. 2014). A number of studies have demonstrated that paying attention to feeding the dam in the middle to last trimester may help improve the chances of survival for the lambs/kids to come out of that pregnancy (McCoard et al. 2017; McGregor 2016).

The presence of dedicated small stock personnel for small ruminants ensured that the animals were drenched for parasitic diseases, were vaccinated for diseases, and were supervised during birth, feeding, and colostrum intake and correctly paired with their mothers, thus favouring lamb/kid survival. The semi-extensive production system which ensures good nutrition for the dams was possibly an additional factor in favour of low neonatal mortalities in this study.

The Dorper breed was plagued by abortions and neonatal deaths while the Damara breed experienced better neonatal survival. Studies have often reported that neonatal mortality rates differ between different breeds (Mukasa-Mugerwa et al. 2000; Swarnkar et al. 2019; Topal et al. 2017). The Dorper is a synthetic breed, fashioned through the fusion of two exotic breeds, and the Damara has literally tracked down from North Africa to southern western Africa, over several hundreds of years, from its origins in Asia (Kandiwa et al. 2019). According to a number of reports, the Damara has adapted to local disease and production conditions, breeds throughout the year, and has a good mothering ability (Almeida 2011; Kandiwa et al. 2019; von Wielligh 2003).

The majority of kids/lambs were born in summer (59.66%), and overall, breed and season had an effect on birth weight. Significantly more winter-born than summer-born Dorper and Swakara lambs weighed below 3 kg than in summer. It is surprising that the majority of Damara lambs were born in winter with weights greater than 3 kg especially when recent reports are pointing out that the breed now breeds equally well throughout the year in the Namibia climate (Kandiwa et al. 2019). Earlier reports, however, have conflicting views on the effect of lambing/kidding season on birth weight with some reporting higher birth weights in winter-born lambs (Doaa et al. 2009; Fasae et al. 2012) and yet others reporting higher birth weights in summer-born lambs (Barzdina and Kairisa 2015; Hagan et al. 2014).

Since, nowadays, production trends and choices are influenced and guided by market requirements, studies comparing the ADG, fat cover, meat-to-bone ratio, meat yield (rib eye area), moisture and drip loss, and sheer force of the Damara, Dorper, and Karakul (Swakara) may need to be reconsidered. Such studies showed that the Dorper had a superior pre-weaning ADG, rib eye area, meat-to-bone ratio, and the best (lowest) sheer force while the Damara had a superior fat thickness and drip loss and the worst (highest) sheer force (Von Seydlitz 1996). Similarly, other studies showed that the Damara had superior polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega 3) than Dorpers and Merinos. On the other hand, the Boer goat has been reported to have a lean carcass whose meat is low in cholesterol (Van Niekerk and Casey 1988; Simela et al. 2004; Webb 2014). One study compared the meat quality characteristics of the Damara, Dorper, and Boer goat and concluded that the Boer goat had inferior carcass yield and lower meat-to-bone ratio but had leaner carcasses and higher concentrations of saturated fatty acids (Tshabalala et al. 2003).

Small ruminant production using the five breeds from this current study under semi-extensive production conditions appears to be a viable proposal as the farmer is able to take advantage of each of the best traits offered by each breed. The results of this study showed that, overall, there were excellent survivability, high birth weight, and highly efficient weaning parameters though there is a pressing need for the farmer to improve record-keeping pertaining to weaning weight and age. It is, however, also apparent that singletons were the most predominant litter size in this study. It is also noteworthy that since the Damara and Dorper were the most populous breeds in the study, their birth weight, neonatal viability, and weaning ages/weights had a profound effect on the productivity of the whole enterprise. There is very limited information regarding the productivity data of the Kalahari Red goat in literature (Kotze et al. 2004; Ramsay et al. 1998), and the results of the current study may serve to bridge this information gap.

References

Abdelqader, A., Irshaid, R., Tabbaa, M.J., Abuajamieh, M., Titi, H. & Al-Fataftah, A.R., 2017, 'Factors influencing Awassi lambs survivorship under fields conditions', Livestock Science 199, 1–6.

Aldridge, M.N., Brown, D.J. & Pitchford, W.S., 2015, 'Genetic and phenotypic relationships between kid survival and birth weight in Australian meat goats', in Proc. Assoc. Advmt. Breed. Genet., pp. 350–353., from http://www.aaabg.org/aaabghome/AAABG21papers/Aldridge21350.pdf.

Alemseged, Y. & Hacker, R.B., 2014, 'Introduction of dorper sheep into Australian rangelands: Implications for production and natural resource management', Rangeland Journal 36, 85–90.

Almeida, A.M., 2011, 'The Damara in the context of Southern Africa fat-tailed sheep breeds', Tropical Animal Health and Production 43, 1427–1441.

Anon, 2011, Namibian Livestock Sector Strategy, Windhoek, Namibia, from http://www.nammic.com.na/jdownloads/IndustryActs/NamibiaLivestockProducerSectorStrategy.pdf.

Atashi, H., Izadifard, J., Zamiri, M.J. & Akhlaghi, A., 2013, 'Investigation in early growth traits, litter size, and lamb survival in two Iranian fat-tailed sheep breeds', Tropical Animal Health and Production 45, 1051–1054.

Balta, B. & Topal, M., 2018, 'Regression Tree Approach for Assessing the Effects of Non-Genetic Factors on Birth Weight of Hemsin Lamb', Alınteri Journal of Agricultural Sciences 33, 65–73.

Barry, D.M. & Godke, R.A., 1997, The Boer goat: the potential for cross breeding, viewed 9 December 2019, from http://www.boergoats.com/clean/articles/godke.htm.

Barzdina, D. & Kairisa, D., 2015, 'The production and quality analysis of Latvian darkhead breed lambs', in S. Zeverte-Rivza (ed.) Nordic View to Sustainable Rural Development, pp. 361–366, NJF Latvia, Riga, latvia., from http://llufb.llu.lv/conference/NJF/NJF_2015_Proceedings_Latvia-361-366.pdf%5Cn%3CGotoISI%3E://WOS:000380590200104.

Behrendt, R., Hocking Edwards, J.E., Gordon, D., Hyder, M., Kelly, M., Cameron, F., et al., 2019, 'Offering maternal composite ewes higher levels of nutrition from mid-pregnancy to lambing results in predictable increases in birthweight, survival and weaning weight of their lambs', Animal Production Science.

Belay, B. & Haile, A., 2011, 'Survivability of lambs under village management condition: The case around Jimma, Ethiopia', Livestock Research for Rural Development 23, viewed 30 December 2019, from https://lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd23/4/bela23079.htm.

Campbell, Q.P., 2003, 'The origin and description of southern Africa’s indigenous goats', South African Society for Animal Science: Popular-scientific articles 4, 18–22, from http://www.sasas.co.za/Popular/Popular.html.

Casey, N.H. & Webb, E.C., 2010, 'Managing goat production for meat quality', Small Ruminant Research 89, 218–224, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2009.12.047.

Chauhan, I.S., Misra, S.S., Kumar, A. & Gowane, G.R., 2019, 'Survival analysis of mortality in pre-weaning kids of Sirohi goat', Animal.

Chay-Canul, A.J., Aguilar-Urquizo, E., Parra-Bracamonte, G.M., Piñeiro-Vazquez, Á.T., Sanginés-García, J.R., Magaña-Monforte, J.G., et al., 2019, 'Ewe and lamb pre-weaning performance of Pelibuey and Katahdin hair sheep breeds under humid tropical conditions', Italian Journal of Animal Science 18, 850–857, from https://doi.org/10.1080/1828051X.2019.1599305.

Chikwanda, A.T., Mutisi, C., Sibanda, S., Makuza, S.M., Kusina, N.T. & Chikwanda, D., 2013, 'The effect of housing and anthelmintic treatment on pre-weaning kid death rate and infestation with gastrointestinal helminthes.', Applied Animal Husbandry & Rural Development 6, 32–35, from http://www.sasas.co.za/sites/sasas.co.za/files/ChikwandaVol6Issue1.pdf%5Cn http://site.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20133426491..

Chniter, M., Hammadi, M., Khorchani, T., Ben Sassi, M., Ben Hamouda, M. & Nowak, R., 2013, 'Aspects of neonatal physiology have an influence on lambs’ early growth and survival in prolific D’man sheep', Small Ruminant Research 111, 162–170.

Dadi, H., Duguma, G., Shelima, B., Fayera, T., Tadesse, M., Woldu, T., et al., 2008, 'Non-genetic factors influencing post-weaning growth and reproductive performances of Arsi-Bale goats', Livestock Research for Rural Development 20, viewed 13 October 2019, from http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd20/7/dadi20114.htm.

De Lange, D., 2008, Small Stock Management, L. Meeser (ed.), Windhoek, Namibia.

Deligiannis, K. & Lainas, T., 2000, 'Effect of lambing season on the productivity of ewes of the Karagouniko breed', Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society 51, 225–235.

Doaa, F., Teleb, E., Saifelnasr, E. & El-Sayed, H., 2009, 'Factors affecting performance and survivability of Saidi lambs from lambing to weaning', Egyptian Journal of Sheep & Goat Sciences 4, 55–74.

Du Toit, C.M., 1995, 'The Damara Sheep in Southern Africa', in Damara Sheep Breeders Association, pp. 13–57, Bloomfontein, South Africa.

Duričić, D., Grizelj, J., Dobranić, T., Harapin, I., Vince, S., Kočila, P., et al., 2012, 'Reproductive performance of boer goats in a moderate climate zone', Veterinarski Arhiv 82, 351–358.

Đuričić, D., Benić, M., Žaja, I.Ž., Valpotić, H. & Samardžija, M., 2019, 'Influence of season, rainfall and air temperature on the reproductive efficiency in Romanov sheep in Croatia', International Journal of Biometeorology 63, 817–824.

Dwyer, C.M., Conington, J., Corbiere, F., Holmoy, I.H., Muri, K., Nowak, R., et al., 2016, 'Invited review: Improving neonatal survival in small ruminants: science into practice', Animal 10, 449–459.

Elia, J., 2018, 'Dam age and weight, lamb sex, breed and kidding type effects on the mortality of local, Turkish Awassi and cross bred', Journal of Research in Ecology 6, viewed 30 December 2019, from www.ecologyresearch.info.

Erasmus, J.A., 2000, 'Adaptation to various environments and resistance to disease of the Improved Boer goat', Small Ruminant Research 36, 179–187.

Fasae, O.A., Oyebade, A.O., Adewumi, O.O. & James, I.J., 2012, 'Factors Affecting Birth and Weaning Weights in Lambs of Yankasa, West African Dwarf Breeds and their Crosses', Journal of Agricultural Science and Environment 12, 89–95.

Gaafar, H., El-Gendy, M., Bassiouni, M. & Shehab El-Din, M., 2011, 'Pre- and Post-Weaning Performance and Economic Efficiency of Rahmani and Finn Lambs and Their Crosses', Researcher 3, 75–79.

Gökçe, E. & Atakışİ, O., 2019, 'Interrelationships of serum and colostral IgG (passive immunity) with total protein concentrations and health status in lambs', Kafkas Universitesi Veteriner Fakultesi Dergisi 25, 387–396.

Gokce, E. & Erdogan, H.M., 2009, 'An Epidemiological Study on Neonatal Lamb Health', Kafkas Universitesi Veteriner Fakultesi Dergisi 15, 225–236.

Gowane, G.R., Swarnkar, C.P., Prince, L.L.L. & Kumar, A., 2018, 'Genetic parameters for neonatal mortality in lambs at semi-arid region of Rajasthan India', Livestock Science 210, 85–92, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2018.02.003.

Greenwood, P., Clayton, E. & Bell, A., 2017, 'Developmental programming and beef production', Animal Frontiers 7, 38–47.

Hagan, B.A., Nyameasem, J.K., Asafu-Adjaye, A. & Duncan, J.L., 2014, 'Effects of non-genetic factors on the birth weight, litter size and pre-weaning survivability of West African Dwarf goats in the Accra Plains', Livestock Research for Rural Development 26, from http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd26/1/haga26013.htm.

Hasan, M.J., Ahmed, J.U., Alam, M.M., Mojumder, M.L.O. & Ali, M.S., 2015, 'Reproductive performance of Black Bengal goat under semi-intensive and extensive condition in Rajshahi district of Bangladesh', Asian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 1, 22–30.

Hebart, M.L. & Brien, F.D., 2018, 'The genetics of lamb survival is different across different birth types', in Proceedings of the World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, p. 703., from http://www.wcgalp.org/system/files/proceedings/2018/genetics-lamb-survival-different-across-different-birth-types.pdf.

Hoffman, M.L., Reed, S.A., Pillai, S.M., Jones, A.K., McFadden, K.K., Zinn, S.A., et al., 2017, 'Physiology and endocrinology symposium: The effects of poor maternal nutrition during gestation on offspring postnatal growth and metabolism', Journal of Animal Science 95, 2222–2232.

Juengel, J.L., Davis, G.H., Wheeler, R., Dodds, K.G. & Johnstone, P.D., 2018, 'Factors affecting differences between birth weight of littermates (BWTD) and the effects of BWTD on lamb performance', Animal Reproduction Science 191, 34–43.

Kandiwa, E., Mushonga, B., Samkange, A., Bishi, A. & Nyoni, N., 2018, 'Retrospective study on small ruminants losses in a farm of Namibia', Indian Journal of Small Ruminants 24, 115–120, from http://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:ijsr&volume=24&issue=1&article=022.

Kandiwa, E., Mushonga, B., Madzingira, O., Samkange, A., Bishi, A. & Tuaandi, D., 2019, 'Characterization of Oestrus Cycles in Namibian Swakara and Damara Sheep through Determination of Circannual Plasma Progesterone Levels', Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2019, 1–6.

Kenyon, P.R., Roca Fraga, F.J., Blumer, S. & Thompson, A.N., 2019, 'Triplet lambs and their dams – a review of current knowledge and management systems', New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 62, 399–437, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00288233.2019.1616568.

Khan, A., Sultan, M.A., Jalvi, M.A. & Hussain, I., 2006, 'Risk factors of lamb mortality in Pakistan', Animal Research 55, 301–311.

King, J.F.M., 2009, 'Production Parameters for Boer Goats in South Africa', University of Free State.

Kleemann, D.O., Quigley, S.P., Bright, R. & Scott, Q., 2000, 'Survival and growth of damara, dorper, dorset, rambouillet, South African Meat Merino first cross lambs in semi arid Queensland', Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 13, 173.

Kleemann, D.O., Walker, S.K., Ponzoni, R.W., Gifford, D.R., Walkley, J.R.W., Smith, D.H., et al., 2016, 'Effect of previous reproductive performance on current reproductive rate in South Australian Merino ewes', Animal Production Science 56, 716–725.

Kotze, A., Swart, H., Grobler, J.P. & Nemaangani, A., 2004, 'A genetic profile of the Kalahari Red goat breed from Southern Africa', South African Journal of Animal Sciences 34, 10–12.

Lehloenya, K.C., Greyling, J.P.C. & Schwalbach, L.M.J., 2005, 'Reproductive performance of South African indigenous goats following oestrous synchronisation and AI', Small Ruminant Research 57, 115–120.

Loureiro, M., Pain, S., Kenyon, P. & Blair, H., 2016, 'Reproductive performance of singleton and twin female offspring born to ewe-lamb dams and mature adult dams', in Proceedings of the New Zealand Society of Animal Production, pp. 151–154.

McCoard, S.A., Sales, F.A. & Sciascia, Q.L., 2017, 'Invited review: Impact of specific nutrient interventions during mid-To-late gestation on physiological traits important for survival of multiple-born lambs', Animal 11, 1727–1736.

McGregor, B.A., 2016, 'The effects of nutrition and parity on the development and productivity of Angora goats: 1. Manipulation of mid pregnancy nutrition on energy intake and maintenance requirement, kid birth weight, kid survival, doe live weight and mohair production', Small Ruminant Research 145, 65–75, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2016.10.027.

Mukasa-Mugerwa, E., Lahlou-Kassi, A., Anindo, D., Rege, J.E.O., Tembely, S., Tibbo, M., et al., 2000, 'Between and within breed variation in lamb survival and the risk factors associated with major causes of mortality in indigenous Horro and Menz sheep in Ethiopia', Small Ruminant Research 37, 1–12.

Mushendami, P., Biwa, B. & Gaomab II, M., 2008, Unleashing the potential of the agricultural sector in Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia.

Mustafa, M.I., Mehmood, M.M., Lateef, M., Bashir, M.K. & Khalid, A.R., 2014, 'Factors influencing lamb mortality from birth to weaning in Pakistan', Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences 12, 139–143.

Namibia Statistics Agency, 2015a, Namibia Census of Agriculture 2013/2014: Commercial, Leasehold and Resettlement Farms. Windhoek, Namibia, from http://nsa.org.na/dw/datawheel.

Namibia Statistics Agency, 2015b, Namibia Census of Agriculture 2013/14: Communal Sector Report, Windhoek, Namibia.

Näsholm, A. & Eythorsdottir, E., 2011, 'Characteristics and utilization of sheep pelts', Small Ruminant Research 101, 182–187.

Petros, A., Aragaw, K. & Shilima, B., 2014, 'Pre-weaning kid mortality in Adamitulu Jedokombolcha District, Mid Rift Valley, Ethiopia', Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health 6, 1–6.

Plush, K.J., 2013, 'Metabolic maturity and vigour in neonatal lambs, and subsequent impacts on thermoregulation and survival', University of Adelaide, from https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/96730/3/02whole.pdf.

Ramsay, K., Harris, L. & Kotzé, A., 1998, Landrace breeds: South Africa’s indigenous and locally developed farm animals., K. Ramsay, L. Harris, & A. Kotzé (eds.), Farm Animal Conservation Trust, Irene, South Africa.

Raoof, S.O., 2018, 'Non-genetic factors affecting the mortality in Kurdi lambs', The Iraqi Journal of Agriciultural Sciences 49, 78–82.

Samkange, A., Kandiwa, E., Mushonga, B., Bishi, A., Muradzikwa, E. & Madzingira, O., 2019, 'Conception rates and calving intervals of different beef breeds at a farm in the semi-arid region of Namibia', Tropical Animal Health and Production 51, 1829–1837, from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-01876-4.

Sánchez-Dávila, F., Bernal-Barragán, H., Padilla-Rivas, G., del Bosque-González, A.S., Vázquez-Armijo, J.F. & Ledezma-Torres, R.A., 2015, 'Environmental factors and ram influence litter size, birth, and weaning weight in Saint Croix hair sheep under semi-arid conditions in Mexico', Tropical Animal Health and Production 47, 825–831.

Schoeman, S.J. & Burger, R., 1992, 'Performance of Dorper sheep under an accelerated lambing system', Small Ruminant Research 9, 265–281.

Silanikove, N., Merin, U. & Leitner, G., 2000, 'The physiological basis of adaptation in goats to harsh environments', Small Ruminant Research 35, 181–193.

Simela, L., Webb, E.C. & Frylinck, L., 2004, 'Effect of sex, age, and pre-slaughter conditioning on pH, temperature, tenderness and colour of indigenous South African goats', South African Journal of Animal Science 34, 208–211, viewed 28 December 2019, from http://www.sasas.co.za/sajas.html.

Snyman, M.A., 2010, 'Factors affecting pre-weaning kid mortality in South African Angora goats', South African Journal of Animal Sciences 40, 54–64.

Snyman, M.A. & Olivier, W.J., 2002, 'Productive performance of hair and wool type Dorper sheep under extensive conditions', Small Ruminant Research 45, 17–23.

Swarnkar, C.P., Narula, H.K. & Chopra, A., 2019, 'Risk factor analysis for neonatal lamb mortality at an organized farm of arid Rajasthan', Indian Journal of Small Ruminants (The) 25, 59.

Topal, M., Emsen, E. & Yağanoğlu, A.M., 2017, 'Chaid and logistic regression approaches for assessing the effects of non-genetic factors on lamb mortality', Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences 27, 40–47.

Tshabalala, P.A., Strydom, P.E., Webb, E.C. & De Kock, H.L., 2003, 'Meat quality of designated South African indigenous goat and sheep breeds', Meat Science 65, 563–570.

Tungu, G.B., Kifaro, G.C., Gimbi, A.A., Mashingo, M. & Nguluma, A.S., 2017, 'Effect of genetic and non-genetic factors on growth and reproduction performance of Black Head Persian and Red Masai Sheep in Tanzania', International Journal of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry 2, 4–10.

Van Niekerk, W.A. & Casey, N.H., 1988, 'The Boer goat. II. Growth, nutrient requirements, carcass and meat quality', Small Ruminant Research 1, 355–368.

Von Seydlitz, H.H.B., 1996, 'Comparison of the meat and carcass characteristics of Karakul, Damara and Dorper', Agricola 8, 49–52.

von Wielligh, W., 2003, 'The Damara Sheep as Adapted Sheep Breed in Southern Africa', in Community-based Management of Animal Genetic Resources, p. 173, Mbambane, Swaziland.

Webb, E.C., 2014, 'Goat meat production, composition, and quality', Animal Frontiers 4, 33–37, viewed 28 December 2019, from https://academic.oup.com/af/article/4/4/33/4638810.

Winrock International, 1992, Assessment of animal agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa., from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lah&AN=19931859210&site=ehost-live.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank the University of Namibia for availing the data which was used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Ethical issues

This study only involved the review of available data, and therefore, no ethical clearance was needed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kandiwa, E., Nguarambuka, U., Chitate, F. et al. Production performance of sheep and goat breeds at a farm in a semi-arid region of Namibia. Trop Anim Health Prod 52, 2621–2629 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02283-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02283-w