Abstract

I provide a novel, non-reductive, action-first skill-based account of active imagining. I call it the Skillful Action Account of Imagining (the skillful action account for short). According to this account, to actively imagine something is to form a representation of that thing, where the agent’s forming that representation and selecting its content together constitute a means to the completion of some imaginative project. Completing imaginative projects stands to the active formation of the relevant representations as an end. The account thus bakes in the means-end order that some in action theory take to be definitional of intentional action. Moreover, in the spirit of this conception of intentional action, I hold that a central feature of the means-end order exhibited in active imagining is the agent’s direct non-observational knowledge both of her act of imagining and of its having this order. The agent knows that she’s actively imagining (that-)p and knows why she actively imagines this–to carry on the pretense, engage in the fiction, predict another’s behavior, reason about possibility or necessity, reason about contingent matters of fact, just imagine for its own sake, and so on. I show that the account accounts for the possibility of misimagining while holding onto the idea that we imagine what we intend to imagine. I likewise show that the account unifies imagining across types of imaginative project like those just listed in a way that tolerates conflict in the roles that imagining plays in the mental economy across those projects. Finally, I show that the account can accommodate passive imagining like involuntary and automatic imagining as well as mind wandering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a sense, we all know what imagining is. It’s what kids do when engaged in pretend play, what an avid fiction reader does when engrossed in a gripping novel, what a cunning general does when taking up the perspective of their adversary, what a savvy interior designer does when considering whether a piece would fit the aesthetic of a room, what a philosopher does when working through a thought experiment, what a bored department head does when mind-wandering instead of reading this year’s expense reports, and what we do when bringing images or thoughts of the (merely) possible before our mind’s eye. The kids imagine the goings-on of the pretense, the fiction reader imagines the world of the novel, the general imagines thinking like their opponent, the interior designer imagines the arrangement of the room that includes the piece, the philosopher imagines the setup of the thought experiment, the department head imagines being anywhere but here, and we imagine whatever is before our mind’s eye.

However, there is another sense in which we do not at all know what imagining is. It is unclear exactly what type of activity is common across the aforementioned cases. And it is unclear what features of imagining would allow it to contribute to such disparate behaviors as pretending, reasoning about possibility and necessity, mind-wandering, and so on. Indeed, even just these three behaviors appear to make conflicting demands on imagining: motivating action, justifying belief, and neither, respectively. For the appeal to imagination to do real explanatory work across the aforementioned cases, there must be some characterization of what it is that is both intelligible and explicates its role in contributing to the relevant behaviors. Unfortunately, attempts at such a characterization have met with difficulty. Such difficulties have led philosophers to doubt that imagining is a unified, potentially explanatory phenomenon after all. Indeed, after considering various kinds of imagining, Kendall Walton asks: “What is it to imagine? […] shouldn't we now spell out what [these kinds] have in common? Yes, if we can. But I can't” (1990, p. 19). And, similarly, Amy Kind asks: “[I]s there such a thing as the phenomenon of imagining? […] we must answer in the negative: There is no single “something” that can play all of the explanatory roles that have been assigned to [imagining]” (2013, p. 157; original emphasis).

This paper provides a novel, non-reductive, action-first skill-based account of active imagining that can explain what is common to imagining across the behaviors it is invoked to explain. I call it the Skillful Action Account of Imagining (the skillful action account for short). According to this account, imagining is paradigmatically active. To imagine something actively is to form a representation of that thing, where forming that representation and selecting its content together constitute a means to the performance of behaviors such as those listed in the preceding paragraphs. I place such behaviors together under the heading of “imaginative project.” So, for example, in a pretense game like ‘the floor is lava,’ one player might respond to another’s tossing a throw pillow onto the floor by forming a representation of, say, an outcropping emerging from the lava as a means of carrying on the pretense. Completion of an imaginative project like carrying on a bit of pretense stands to the active formation of the corresponding representation as an end. The account thus bakes in the calculative, means-end order that some in action theory take to be definitional of intentional action. Moreover, in the spirit of this conception of intentional action, I hold that a central constitutive feature of this order is the agent’s possessing direct non-observational knowledge both of her act of imagining and of its having the relevant means-end order. This is her practical knowledge of her active imagining. In possessing that practical knowledge, our pretender knows that she is actively imagining the emergence of the outcropping and knows why she actively imagines this, namely, to carry on the pretense. Her knowledge in her intention to play constitutes her corresponding act of imagining. Both the means-end order and the agent’s practical knowledge thereof are on the skillful action account essential parts of what it is for her to imagine. Moreover, in taking active imagining to be the central imaginative kind, the account highlights the importance of both the means-end order and practical knowledge to understanding the nature of imagining.

The skillful action account provides a characterization of imagining in terms of its paradigmatically being a type of skillful action. Human beings might well start out with a bare capacity for forming representations at will and in the absence of a corresponding stimulus. But, even so, for this capacity to contribute to pretense and the like, agents have to learn how to imagine in ways appropriate to the completion of the corresponding imaginative project. And, as with other types of skillful action, this takes training and practice. So, although infants appear able to engage successfully in simple pretend play and in joint acts of pretense with non-infants (Nielsen & Christie, 2007; cf. Hess, 2006), imagining appropriate to, say, completing a yearlong Dungeons & Dragons campaign requires an ability to imagine shaped by sufficient practice playing tabletop games. Similarly, as with other types of skillful action, one’s imagining can improve along certain dimensions and can be appropriate or not in relation to the type of imaginative project one is engaged in. Bracketing aphantasia, a painter’s visualizing is apt to be more vivid than a non-painter’s. And an impressionist painter’s visualizing is apt to be more impressionistic overall compared to the likely more geometric visualizing of a cubist.

The characterization of imagining as paradigmatically a type of skillful action provided by the skillful action account can explicate imagining’s role as a means in contributing to pretense, engagement with fiction, predicting others’ behavior, reasoning about possibility and necessity, hypothetical and counterfactual reasoning about contingent matters of fact, mind-wandering, imagining for its own sake, and so on. According to the account, as with other types of skillful action, distinct acts of imagining can be put to use towards very different, even conflicting ends. Moreover, in their service as means, such acts can take on very different, even conflicting properties. For instance, painting as part of creating a work of art might well require the agent to do something that is very different or that even conflicts with what would be required of her in painting as part of renovating a home. Nonetheless, painting as a type of skillful action is identifiable despite this variation and conflict across its instances: it is the exemplification of some practice of at least minimally aesthetic expression through color. Skillful act-types tolerate variation and conflict in the role they play across their instances. If, as the skillful action account has it, imagining is paradigmatically a type of skillful action then such variation and conflict across its instances is to be expected and is consistent with type-individuating imagining as a skillful mental action.

In what follows, I introduce the skillful action account (Sect. 2) before applying it to explain, programmatically, the role of imagining across types of imaginative project (Sect. 3). I then show how the account elucidates the intentionality of imagining as part of its characterization of imagining (Sect. 4) and addresses passive instances of imagining (Sect. 5) before concluding by touching on six avenues for future research.

2 Advancing the account

Here, in brief, is the account:

2.1 The skillful action account of imagining

An agent’s forming some representation is an instance of active imagining iff

-

(i)

her constructing that representation and selecting its content together constitute a means to her completing some project and;

-

(ii)

her completing that project consists in the exercise of her practical knowledge of her constructive activity as a means.

The account treats active imagining as the central imaginative kind and, thus, takes imagining in general to consist paradigmatically in the performance of this type of mental action. To simplify things, going forward, I restrict focus to active imagining among healthy individuals from adolescence through adulthood under normal conditions. By “constructing a representation,” I mean what Van Leeuwen (2013) calls “constructive imagining.” That is, active imagining involves the agent’s “coming up with mental representations that have [such-and-such] content” by “combin[ing] elements of ideas from memory” in a way usually governed by background beliefs, conventions, and guiding principles specific to each type of imaginative project (221, 224). For example, an act of imagining a dancing banana involves the combination of elements of the agent’s conception of bananas with that of her conception of dancing. Elements of the former might include the typical shape, color, texture, and so on of bananas, while elements of the latter might include stereotyped movements of, say, freeform dancing.Footnote 1 I depart from Van Leeuwen in denying that construction on its own counts as a kind of imagining. For instance, the coming of perception-like images to mind unbidden might well involve the subject’s combining elements of ideas from memory, however implicitly. But such an instance of construction is not thereby an instance of imagining, let alone an instance of active imagining.Footnote 2 To imagine actively, an agent must not only combine elements of ideas she has but must also select those elements in light of what she aims to do with the resulting representation.

By “selecting the content of a representation,” I mean what Dorsch (2012) discusses under the heading of the specific determination of content (387–391). That is, active imagining involves the agent’s “voluntary determination of which entities are represented as instantiating which properties” (389). In imagining a dancing banana, the agent does not just select the topic of her imagining. That is, she does not just hold an intention to imagine a dancing banana and then leave the rest to nature (cf. Strawson, 2003). Rather, she exercises selective agency over which entity she imagines and its properties, namely, some individual banana that is moving itself in the relevant way(s). She might also represent the banana as having a particular color, shape, texture, and so on. I likewise follow Dorsch (2012) in taking it that the agent’s involvement both in constructing the relevant representations as well as in fixing their content distinguishes imagination from other mental faculties like perception and belief. The content of perception and belief-formation are in the good case fixed by external stimuli and by one’s evidence, respectively, such that what the agent perceives and believes is at least typically outside of her control. By contrast, the agent’s ability to select what she represents in imagining is part of the so-called “freedom of imagination.” Some have thought that such freedom is a distinguishing mark of the faculty since at least as far back as Hume (1777/2000, 1739/2007). I will have more to say about this aspect of the freedom of imagination in Sect. 4.

By “project,” I mean goal-directed movement, whether bodily or mental, that can be pursued by means of imagining as well as such movement that must be so pursued. These projects include but are not limited to:

-

imagining for its own sake (Dorsch, 2012; Van Leeuwen, 2013);

-

pretense (Carruthers, 2002, 2006; Gendler, 2000, 2003, 2006a, b, 2010; Nichols, 2004; Nichols & Stitch, 2000, 2003; Picciuto & Carruthers, 2016);

-

engagement with fiction (Chasid, 2019; Currie, 1990; Doggett & Egan, 2007; Meskin & Weinberg, 2003; Walton, 1990);

-

predicting or explaining others’ behavior (often called “mindreading”) (Currie & Ravenscroft, 2002; Goldman, 2006; Heal, 2003);

-

reasoning about possibility and necessity (Gregory, 2004, Gregory, 2020; Williamson, 2007; Kung, 2010; Ichikawa & Jarvis, 2012; cf. Fiocco, 2007; Spaulding, 2016);

-

hypothetical and counterfactual reasoning about contingent matters of fact (Blomkvist, 2022; Kind & Badura, 2021; Kind & Kung, 2016; Myers, 2021a, 2021b); and

-

mind-wandering (Christoff et al., 2016; Irving & Glasser, 2019; Irving et al., 2020).

Following the philosophical literature on imagination, I treat each listed behavior performed by means of imagining as constituting a distinct type of imaginative project. Completing imaginative projects consists in performing the relevant behavior by means of imagining. Importantly, on the skillful action account, agents must learn how to complete each type of imaginative project. There is no inbuilt faculty or module for pretense, engagement with fiction, mindreading, reasoning about possibility and necessity, and so on. If so, then active imagining is skillful in large part thanks to the agent’s learning and mastering principles, methods, techniques, heuristics, and so on specific to the domain of each type of imaginative project.Footnote 3 Her practice pretending, getting engrossed in fictional narratives, figuring out what someone will do next, and so on quite literally shapes her capacity to imagine over time, making her a more refined and sophisticated imaginative agent.Footnote 4 I will have more to say about imaginative projects and imaginative skill in Sect. 3.

By “means,” I have in mind a more immediate action by which some other action is performed or by which some end that is currently at a distance from the agent is achieved. Immediacy and being at a distance are interdependent notions that pick out relations among actions and ends. The means an agent takes are actions that suffice to close at least some of the distance between her and her goal. A sufficient means is an action that suffices to completely close such a distance. Recall our pretender playing ‘the floor is lava.’ In playing the game, her imagining that the floor is lava is immediate and is done in order to perform pretense actions like jumping from one outcropping to another, where, for instance, two sofas function as the appropriate props in the game. Unlike the real-world act of jumping between sofas, the pretense act of jumping between outcroppings is at a conceptual distance. The latter action’s being at a conceptual distance is due to the fact that, in addition to performing the real-world act, the agent must register jumping between sofas as constituting a legitimate move in the game and must be motivated to pursue this move. The calculative relation between means and ends on display in this example can be iterated. For instance, the agent might perform the pretense act of jumping between outcroppings in order to carry on the pretense and might carry on the pretense, in turn, in order to entertain herself and her friends. Moreover, each means sufficient for closing at least some of the distance between the agent and her goal might consist in the performance of multiple actions. In the case under consideration, the agent both imagines and actually jumps in order to perform the pretense act of jumping between outcroppings. For other imaginative projects, for instance, engagement with fiction, the act of imagining, e.g., the goings-on of the world of the fiction, can itself be a sufficient means to their completion.

Finally, by “practical knowledge,” I mean the agent’s knowledge of what she is doing such that what she is doing has the calculative means-end order that constitutes it. Practical knowledge is the agent’s knowledge in intention (Small, 2012, 135ff.; Campbell, 2017, 17ff.). Our pretender knows that she is playing ‘the floor is lava’ as part of her intending to play and this gives her knowledge of the means that she is taking: her imagining, her jumping, her performing pretense actions, and so on.Footnote 5 The means-end order I have been drawing out of the example would not exist were it not for her practical knowledge. Acquisition of the agent’s ability to practically cognize what she is doing such that she has practical knowledge of her doing it depends in part on her having the requisite knowledge-how.Footnote 6 In the case under consideration, part of what allows the agent to play intentionally and, thus, knowingly is her knowing how to pretend as well as her knowing how to play ‘the floor is lava’. Such knowledge-how is gained through practice. Yet, once our pretender has acquired this knowledge-how, she can readily apply it whenever the opportunity arises. Because practical knowledge stems from the agent’s practical cognition, that is, from her intention, it is knowledge unlike that drawn from belief or perception in that she possesses it without drawing on evidence (Campbell, 2017, pp. 18–19). Our pretender imagines that the floor is lava ultimately because she possesses practical knowledge of her end in intending to play.Footnote 7 Such knowledge contains her knowledge of the means she takes to that end. In the case under consideration, the agent does not need to observe or infer that she is imagining or that her imagining is efficacious to know that she is imagining, what she is imagining, or why. She does not rely on observation or inference because her imagining itself stems from her practical knowledge of it in intending to pretend. I will have more to say about the role of practical cognition in imagining in Sects. 3 and 4.

Recall our pretender playing ‘the floor is lava.’ According to the skillful action account, she actively imagines that the floor is lava because, in intending to carry on the pretense, she intentionally forms a representation of the floor’s being lava as a means to that end. By contrast, consider an agent engaging in Tolkien’s Return of the King and, in so doing, imagining the scene where Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee enter Mount Doom. According to the skillful action account, this agent actively imagines, say, that Frodo and Sam are standing at the precipice, looking down on a molten pit whose flames are roaring all around them. He is doing this because he intentionally forms a representation of this event in Frodo’s and Sam’s journey as a means to engaging in the fiction. In the one case, the pretender’s active imagining supplies a representation with properties that allow it to bear both a motivational and justificatory relation to certain pretense actions. In the other, the fiction reader’s active imagining supplies a representation with properties that allows it to bear only a justificatory relation to his active and immersive reading of Return of the King.Footnote 8 What remains the same between the cases is the means-end order specific to imagining and each agent’s practical knowledge thereof. That order and their practical knowledge are thus essential parts of what it is for them to imagine.

In taking active imagining to be the central imaginative kind, the skillful action account highlights the importance of both the means-end order and practical knowledge to understanding the nature of imagining itself. More than that, the account sets out the form specific to imagining as a type of mental action. By virtue of being a type of action that can be performed intentionally, imagining is a type of happening characterized by a means-end order that is definitional of it.Footnote 9 The skillful action account explicates the means-end order specific to active imagining and, thus, characteristic of imagining in general. According to it, that order consists in, on the one hand, the agent’s constructing a representation and selecting its content as means and, on the other, her completing the corresponding imaginative project as end. In proposing this account, I thus adopt a novel position concerning the metaphysics of imagination. In effect, what I am proposing is an action-first non-reductive ontology of imagination (cf. Langland-Hassan, 2020).Footnote 10 My aim in making this proposal is in the first place programmatic: I want to provide a unifying account of imagining that has materials sufficient to explain its role in contributing to the completion of imaginative projects.Footnote 11 It is to this that I now turn.Footnote 12

3 Applying the account part I: the role of active imagining in imaginative projects

Recall the problem with which I began. On the one hand, we seem to know what imagining is and to be able to identify it as playing a key role across a number of disparate types of imaginative project. It seems that imagining involves the agent’s ability to form certain kinds of representation at will (cf. Strawson, 2003). And it seems that this representation formation activity is implicated in pretense, engagement with fiction, mindreading, reasoning about possibility and necessity, hypothetical and counterfactual reasoning about contingent matters of fact, mind-wandering, and so on. On the other hand, these behaviors seem to make conflicting demands on imagining such that it is difficult to see what is common to the activity across its contributions to them. We are thus hard pressed to provide a characterization of imagining that is both intelligible and can explicate its role across the relevant types of imaginative project. The problem, then, is to find a unity within this multiplicity. Call this the Unity-in-Multiplicity Problem.

The problem is especially acute once we consider the functions ascribed to imagining. Given what imagining is thought to do within each type of imaginative project and what features of imagining are thought to allow it to do this work, it can seem that the activity is attributed conflicting functions. For instance, in pretending, imagining the goings-on of the pretense is supposed to be such that it motivates action in the actual world. By contrast, in engaging with fiction, imagining the world of the fiction is supposed to be such that it does not motivate action in the actual world. In hypothetical and counterfactual reasoning about contingent matters of fact, imagining what might occur or what could have occurred is supposed to be such that it justifies beliefs closely tied to the actual world. In many other types of imaginative project, imagining is supposed to be such that it does not justify beliefs closely tied to the actual world. In mindreading, imagining being in another’s shoes is supposed to be such that it both justifies beliefs concerning the actual world and motivates action in the actual world. In many other types of imaginative project, imagining is supposed to be such that it neither justifies beliefs concerning the actual world nor motivates action in the actual world. In engagement with fiction and (at least certain instances of) mindreading, imagining is supposed to be such that it gives rise to affective states. In reasoning about possibility and necessity, imagining what possibly is or what must be is supposed to be such that it does not give rise to affective states. Given conflict in the functions ascribed to imagining and in the features of instances of imagining that are supposed to allow it to perform these functions across types of project, the trouble becomes saying what imagining is that tolerates this conflict and does not just resolve into a heap of accounts specific to each type of imaginative project.Footnote 13

One response to the Unity-in-Multiplicity problem has been to give up altogether on finding a characterization that can do both, as Walton (1990) and Kind (2013) suggest. Kind puts the motivation for this response best:

[T]he explanatory burden that imagination must carry varies greatly from context to context. Not only do features that are essential to imagination in one context drop out entirely in another context, but even worse, features of imagination that play an essential role in one context are sometimes inconsistent with features of imagination that play an essential role in another context. […] When philosophers invoke imagination to explain one [type of imaginative project] […] the thought is that there is something special about imagination itself that can do the explanatory work. In each individual context, this claim may well seem plausible. But once we look at the contexts together, the initial plausibility of the claim dissipates (2013, p. 157).

We might be able to characterize certain kinds of imagining and we might be able use such accounts to elucidate imagining’s role among some subset of types of imaginative project. But, so this response maintains, it is not possible to provide a characterization of imagining that captures a single unified mental phenomenon, illuminates its nature in an intelligible way, and satisfactorily unifies its instances across sufficiently diverse types of project. Much of the literature on imagination accordingly adopts a piecemeal approach, some explicitly in light of the worries voiced by Walton and Kind (see, for instance Langland-Hassan, 2020; cf. Wiltsher, 2019a, b, 2023).Footnote 14

Luckily, this is not the only response to the problem. One viable response is to treat the problem as gesturing towards core desiderata for accounts of imagining that aim to unify its instances across types of imaginative project. I count at least two core desiderata. First, a unifying account of imagining should be intelligible in the sense that it is useful for theorizing about imagination and provides some insight into the nature of imagining. Call this the “intelligibility desideratum.” Arguably, a source of the discouraging response to the Unity-in-Multiplicity problem is a recognition that accounts that aim for unity tend to give up intelligibility and this undercuts their potential explanatory power (cf. Dorsch, 2012). An adequate characterization of imagining should capture its essential features, specifically what distinguishes it as a mental activity. What is more, an adequate characterization should specify what features of imagining in particular make it well suited to contribute to the completion of imaginative projects. This leads to the second desideratum on unifying accounts, namely, such accounts should provide a characterization of imagining that explicates the contribution it makes to completing imaginative projects. Call this the “explication desideratum.” Arguably, another source of the discouraging response to the problem is a recognition that accounts that aim for unity often end up providing a satisfactory explication of imagining’s contribution to only a few types of intimately related imaginative projects at the expense of covering types of project that differ significantly from those it treats as central. An adequate characterization of imagining should show how types of imaginative project generally hang together as types of imaginative project.

In this section, I argue that the skillful action account of imagining has the resources to satisfy both desiderata and is thus in a position to resolve the Unity-in-Multiplicity problem. What is more, the account has the added benefit of providing a characterization that fits naturally with the folk understanding of imagining as an essentially agentive representation formation activity. To mount my argument, I draw attention to five parameters common to the performance of skillful action through a series of parallels between skillful bodily action and active imagining. A single type of skillful action can tolerate variation in the values of these parameters across its instances, including values that conflict with the values of parameters of another instance of that same act-type. Such variation and conflict across instances are fully consistent with type-individuating these actions. One need only identify the means-end order specific to the type of action. I suggest that the same applies to active imagining: its instances exhibit variation in the values of these same parameters, including values that conflict with the values of parameters of other instances of active imagining. Accounting for the conflicting functions ascribed to imagining across types of imaginative project by appeal to the parameterization of skillful action satisfies the explication desideratum. At the same time, the skillful action account sets out the act-type common across such variation and conflict: constructing a representation and selecting its content as a means of completing an imaginative project. This specification of the act-type satisfies the intelligibility desideratum.

Consider a skillful action like painting. On the skillful action account of imagining, painting and active imagining are species of a common genus, namely, skillful action. To unpack this claim, consider the following five parameters on skillful action:

-

(i)

variation in properties across performances;

-

(ii)

variation in causes across performances;

-

(iii)

variation in effects across performances;

-

(iv)

practical knowledge of a performance;

-

(v)

propriety of a performance;

Let us consider each in turn. Focus on painting. The properties (i), causes (ii), and effects (iii) of individual acts of, say, making brushstrokes, observing one’s subject, mixing paints, blending, and so on vary depending at least in part on the end for which these acts are means. Focusing on brushstrokes, a brushstroke can be slow, quick, careful, careless, and so on. Beyond adverbial properties, brushstrokes can involve one set of bodily movements on one occasion and a contrary set of movements on another, be expressive of a particular style on one occasion and expressive of a contrary style on another, and so on (i). Making a brushstroke can be caused by a prior intention or by an appropriate cue, say, glimpsing a bit of negative space to be filled with a vibrant color (ii). And making such a stroke can result in or come to constitute, say, applying primer, blocking in, layering, adding accents, shading, creating contrast, refining shapes, applying sealant, and so on (iii). In the bodily case, then, a single type of skillful action can exhibit significant variation across its instances at least in part due to those instances constituting distinct means to distinct ends.

In addition to this outward variation, there is significant variation in one’s practical knowledge (iv) of the acts involved in particular instances of painting. As a result, there is significant variation in the propriety of those acts (v). Whether an individual brushstroke is properly also an application of primer, blocking in, adding contrast, and so on depends on the agent’s knowing how to perform these wider actions as part of the exercise of her practical knowledge on the relevant occasion. The practical knowledge that the painter brings to bear on making a brushstroke for the sake of applying primer differs from the practical knowledge she brings to bear on making a brushstroke for the sake of blocking in differs from… Each making of the brushstroke differs in light of the painter’s practical knowledge of the end to which that stroke serves as a means. But even practical knowledge of just the brushstroke in isolation will differ across instances, since such knowledge incorporates appropriate respecification of the painter’s intention in light of how her performance is currently unfolding (Small, 2012, p. 158) (iv). Importantly, the painter’s acquiring actionable knowledge-how to make the relevant brushstrokes depends at least in part on sufficient practice performing such strokes in accordance with the principles internal to the domain of her skill, say, portrait painting. Only once she has acquired this knowledge-how can she put it to use in exercising her practical knowledge.Footnote 15 Such knowledge-how is chiefly what establishes what is appropriate for any given performance by virtue of reflecting the standards of the artform (v). Recall that the agent’s practical knowledge comes to constitute her performance by way of constituting the means-end order which that performance embodies. It is the skill itself and its exemplification in action, then, that possess these parameters and their values, respectively.

Variation across performances of an action—including performances exhibiting values of parameters (i)–(v) contrary to each other—in no way prevents identifying those performances as tokens of the same type. Type-individuating the relevant action depends on identifying its role as a means across the range of wider actions in which its instances are embedded. Although I have up to this point focused entirely on a single aspect of painting, namely, making brushstrokes, what I have said thus far applies to the other acts constitutive of the artform. Moreover, I take it that the paradigmatic expression of the skill is actually putting paint to a surface. The means-end order specific to painting, then, is the agent’s at least minimally aesthetic expression through color as a means of participating in the relevant artform.Footnote 16 The artform in which some instance of painting counts as participating specifies the principles that, when incorporated into the painter’s repertoire of actionable knowledge-how, contribute to establishing what is appropriate for that bit of painting. Importantly, I take the relevant set of artforms to include those setting out the principles of, say, painting the walls of a house or giving a car a paint job. Any action worth counting as an instance of painting will involve the application of color to a surface in a way that is informed by a social practice that takes such application as its primary means, provides at least the potential for mastery of such application, and is at least minimally concerned with aesthetic value.

The points laid out in the previous three paragraphs apply directly to active imagining. Recall our pretender playing ‘the floor is lava.’ Regarding parameters (i)–(iii), our pretender’s imagining can be slow, quick, careful, careless, and so on. Beyond adverbial properties, imaginings differ in their format, attitudinal, and phenomenological properties. Our pretender might construct a representation of the lava that has a perceptual or sensory phenomenal character or format, that is, “mental imagery” (Van Leeuwen, 2013, p. 222; Nanay, 2010, 2016, 2021, 2023). Her imagery might be thin and sparse or richly detailed and she might integrate it into her perceptual field (Brown, 2018; Van Leeuwen, 2011). Or our pretender might hold a proposition in mind that she takes to be (merely) fictional or non-actual, say, that, within the pretense, she is surrounded by lava. That is, she might engage in “attitudinal imagining” (Langland-Hassan, 2020; Van Leeuwen, 2013). Or she might hold in mind the lava itself and treat what she is representing as fictional or non-actual. That is, she might engage in “objectual imagining” (Yablo, 1993) (i). Our pretender’s imagining might be caused by a prior intention or might be a response to an appropriate cue, say, being told by another player “look out! The floor is lava!”. Similarly, were an agent imagining an event in which he or another is surrounded by lava as part of engaging in a fiction, his imagining might likewise be quick, slow, careful, careless, and so on. Such imagining might likewise be imagistic, attitudinal, or objectual. And such imagining might be caused by a prior intention or an appropriate cue, say, reading, “the fires below awoke in anger, the red light blazed, and all the cavern was filled with a great glare and heat” (Tolkien, 1993, p. 1238) (ii). Our pretender’s imagining will cause further imaginings in keeping with the goings-on of the pretense as well as pretense actions motivated by what she imagines. By contrast, our fiction reader’s imagining himself or another surrounded by lava as part of engaging with a fiction should not result in the performance of any actions by which he means to affect the goings-on of the world of the fiction, lest he lapse into pretense (iii).

Parameters (iv) and (v) bring the skillful nature of active imagining to the fore, specifically as a means of principle-driven completion of imaginative projects. Our pretender’s practical knowledge (iv) that she is imagining that the floor is lava and why, namely, to carry on the pretense, is at a minimum the application of her knowledge-how to attribute non-factual things to herself, to attribute the relational property of being surrounded by lava, and to play ‘the floor is lava’. Application of this knowledge-how in her act of representation formation is such that it motivates and thereby results in her performing pretense actions appropriate to carrying on the pretense. Her acquiring this knowledge-how depends in the first instance on practice imagining across types of project, including practice engaging in pretense. Indeed, the development and subsequent shaping of the pretender’s capacity to imagine is a process of learning through guided practice in joint imaginative acts, unguided practice in solo imaginative acts, and performance in the completion of the relevant imaginative project (Small, 2014). Focusing on pretense, infants engage in solo pretend play only for short bursts and can play for extended periods only thanks to scaffolding from others (Nielsen & Christie, 2007; cf. Hess, 2006). By the time of adolescence, agents are in principle able to engage in pretense indefinitely, as any avid player of Dungeons & Dragons can attest.

The preceding is true of engaging with fiction as well. Recall our fiction reader. The fiction reader’s practical knowledge (iv) that he is imagining Frodo’s and Sam’s approach to Mount Doom and why, namely, to engage in Tolkien’s Return of the King, is at minimum his application of his knowledge-how to attribute several complex properties to non-existent characters, to relate events that never actually occurred to each other in a narrative order, and to read epic high fantasy. Application of this knowledge-how also depends in the first instance on practice imagining across types of project, including practice engaging in fiction. The development and subsequent shaping of the fiction reader’s capacity to imagine is a process of learning through guided practice in joint imaginative acts, unguided practice in solo imaginative acts, and performance in the completion of the relevant imaginative project. In learning to read fiction, the agent learns more than how to parse the relevant sentences and words in context. He learns how to immerse himself in a world that is not his own (usually) without being motivated to act so as to affect the goings-on of the fictional world. He learns how to construct episodes or thoughts about events and relate them to each other in a narrative structure, how to attribute mental states to others (sometimes on the basis of being told what those others are thinking), and so on all with the recognition that the subjects of his mental actions are not, strictly speaking, supposed to exist or be influenceable by his actions. He acquires this actionable knowledge-how to engage in a distinctive mode of thought (or of entertaining imagery) through guided and unguided practice in reading fiction, engaging other imaginative projects, and reading non-fiction.

Relating the capacity to imagine to the propriety of imaginative performances (v), part of what our pretender acquires through practice is grasp of the principles that guide her pretense behavior. Each type of imaginative project brings with it some such principles that partially define the corresponding domain of skill. These principles govern not only the production and transformation of imaginative states and their contents but the production and transformation of corresponding non-imaginative states and behaviors involved in the successful completion of the relevant imaginative project as well. For example, there are arguably two primary principles at work in pretense (Gendler, 2003, 2006a, b). First, actions performed within the pretense mirror the causal and logical structure of the corresponding non-pretense behaviors were the events of the pretense to occur at the actual world. Second, the goings-on of the pretense, including pretense actions involving real-world behavior, are taken to have effects quarantined to the within the pretense. Our pretender’s imagining is usually formed and updates in accordance with these mirroring and quarantining principles and it is these principles that she exploits in performing pretense actions, injecting new content into the pretense, and intentionally violating those very principles.Footnote 17 She becomes proficient in pretending in part by internalizing both principles through guided and unguided practice, where the outcomes of her attempts therein serve as feedback. Such internalization literally shapes her capacity to imagine.

Once incorporated into her capacity to imagine, the principles guiding the completion of a type of imaginative project come to underwrite both the agent’s acts of constructing the appropriate content (v) as well as her making appropriate use (v) of that content in completing tokens of the relevant type of project. As with other types of skillful action, the proficient imaginer puts her hard-won knowledge-how to use in exercising her practical knowledge. And because exercise of her practical knowledge constitutes her imaginative performance by way of constituting the means-end order that that performance embodies, it is the skill itself and its exemplification in action that possess these parameters and their values, respectively.

Again, the preceding applies to engagement with fiction as well. Walton (1990) identifies two primary principles for generating fictional truths, i.e., facts which hold of the relevant fictional world(s), that a competent audience will apply when engaging with the relevant fiction. First, if propositions p1,…,pn are ones whose fictionality a piece generates then another proposition, q, is fictional relative to that piece just in case if p1,…,pn were the case then q would be the case. Walton calls this the Reality Principle (RP) (1990, p. 145). A fictional truth that is generated directly is one that is asserted by way of features of the piece itself given the conventions and, thus, social practices surrounding the production of such pieces. In our running example, directly generated fictional truths would be those expressed on the page by Tolkien. RP sanctions further indirect generation, where the fictionality of a proposition relative to a piece is inferable from another in accordance with RP even if the latter is not itself generated directly by the piece. For instance, our reader can realize that it is fictional that Frodo and Sam are sweating by inferring from the fictional truths that hobbits have physiology at least not unlike ours and that the temperatures inside Mount Doom are likely to be similar to those at the mouth of an erupting volcano at the actual world. Neither of these fictional truths are (to my knowledge) generated directly by Return of the King.Footnote 18 Second, if propositions p1,…,pn are ones whose fictionality a piece generated directly then another proposition, r, is fictional relative to some piece just in case it is mutually believed in the author’s society that if p1,…,pn were the case then r would be the case. Walton calls this the Mutual Belief Principle (MBP). Walton notes that the ways by which fictional truths are generated directly is conventional. He also notes that neither RP nor MBP are meant to be universal principles. They can be violated, like the principles guiding pretense. What is important is that our reader’s imagining is usually formed and updates in accordance with RP and MBP and it is these principles that he exploits in elaborating the fictional world of Middle Earth, in entertaining himself by wondering whether hobbits braid their feet hair, and so on. He becomes proficient at engaging in fiction in part by internalizing these principles through guided and unguided practice, where the outcomes of his attempts therein can be compared to public expressions of others’ and, thus, indirectly serve as feedback. Such internalization literally shapes his capacity to imagine.

Similarly, Once incorporated into her capacity to imagine, the principles guiding the completion of a type of imaginative project come to underwrite both the agent’s acts of constructing the appropriate content (v) as well as his making appropriate use (v) of that content in completing tokens of the relevant type of project. And, again, because exercise of his practical knowledge constitutes his imaginative performance by way of constituting the means-end order that that performance embodies, it is the skill itself and its exemplification in action that possess these parameters and their values, respectively. The differences between our pretender and our fiction reader, specifically the differences between the motivating features of the former’s imagining and the lack thereof of the latter’s, stem from differences in the principles appropriate to the respective domains of each type of project. In particular, the mirror and quarantining principles in the domain of pretense and the lack of such principles in the domain of engaging with fiction result in imaginings with distinct functional profiles in proficient imagining agents exercising their capacity in either domain. Acts of imagining backed by these principles will result in representations that have positive or negative valences or the character of directives or affordances, whereas those backed by RP and MBP result in representations that do not. The exception is, arguably, interactive fiction, which is arguably a kind of pretense (cf. Walton, 1990). Because the skillful action account has it that such principles come to shape the capacity to imagine in the form of embodied, actionable knowledge-how, this means that the capacity itself is structured as a complex of dispositions for exercising such knowledge-how in appropriate contexts and in light of the imagining agent’s intention to imagine thusly. It is the structure of the complex—fashioned through inculcation into the relevant domains—and activation of the appropriate parts of it qua exercise of the imagining agent’s practical knowledge that allows individual exercises of the capacity to imagine to have seemingly inconsistent properties when we consider the capacity independently of any of its exercises. The insight of the skillful action account is that the same is true of other capacities worthy of being called skills, as the case of painting shows.

I am now finally in a position to show that the skillful action account can satisfy the intelligibility and explication desiderata on unifying accounts of imagining. Starting with the explication desideratum, recall that an adequate unifying account should provide a characterization of imagining that explicates the contributions it makes to the completion of imaginative projects. The parameters of skillful action show how the account can do this. First, if, as the account has it, active imagining is a skillful type of action then variation in the properties, causes, and effects of its instances is to be expected. This includes cases in which the values of the parameters in one performance conflict with the values of the parameters in another performance. Second, the agent learns through practice the principles specific to each type of imaginative project. She then applies what she has learned in exercising her practical knowledge in imagining. In possessing this knowledge, she constructs and makes use of representations that are systematically attuned to the corresponding imaginative project that she intends to complete. Conflict in the role of painting across artforms dissolves once it is acknowledged that the painter is in one context intending to do one thing in painting and is in another context intending to do something else in painting. What is shared across these contexts is her intentionally performing the same act as means to these distinct ends under the self-imposed guidance of the relevant principles. By the same token, both conflict in the role imagining plays across types of imaginative project as well as conflict in the features that are supposed to allow it to play its role are resolved once it is acknowledged that the sufficiently proficient imaginer is in one context intending to do one thing in imagining and is in another context intending to do something else in imagining. What is shared across these contexts is her intentionally constructing a representation and selecting its content as a means to completing distinct imaginative projects under the self-imposed guidance of the relevant principles.

Moving on to the intelligibility desideratum, recall that an adequate unifying account should be intelligible in the sense that it is useful for theorizing about imagining and provides some insight into its nature. By laying out the means-end order specific to imagining as a mental action and by fleshing its characterization out with the five parameters of skillful action, the skillful action account can do this. The claim that active imagining is paradigmatically a type of skillful mental action is straightforwardly intelligible. The claim that this mental action consists in forming a representation, selecting its content, and making use of the representation so formed as a means to pretending, engaging with fiction, mindreading, and so on is illuminating of the nature of imagining. The addition of the five parameters enriches this characterization. In particular, the skillful dimensions of imagining come into focus by considering how acquiring knowledge-how to engage appropriately in different types of imaginative project shapes both the capacity to imagine and essential features of its individual exemplifications. It becomes clear how, through practice, the agent’s practical knowledge of those imaginings becomes increasingly nuanced and sensitive to the demands of the corresponding imaginative project. Finally, the characterization of imagining provided by the skillful action account is ripe for theorizing. And this brings us back to the Unity-in-Multiplicity problem. I have so far provided a programmatic roadmap for addressing the problem. Fully addressing it requires, first, laying out the principles specific to each type of imaginative project and, second, showing that sufficient practice constructing representations in accordance with those principles is in fact how agents become proficient pretenders, fiction readers, mind-readers, and so on. Such is the plan for an empirically informed philosophical research program suggested by the skillful action account of imagining.

Finally, to close out this section, note that the characterization of active imagining provided by the skillful action account fits naturally with the folk understanding of imagining. Imagining is generally understood as an activity of forming representations wherein the agent fixes the content of the representations thus formed. Moreover, imagining is generally understood to play a role at least across the types of imaginative project under consideration. It is only when we subject this latter part of the folk understanding to philosophical and scientific scrutiny that the Unity-in-Multiplicity problem emerges. Finally, agents who display mastery in the completion of a type of imaginative project are often attributed a correspondingly refined capacity to imagine. Indeed, figures as disparate as Albert Einstein and Andy Warhol are both treated as being expert imaginers. The account explicates and, thus, upholds the folk notion of imagining by laying out the specific type of skillful mental action in which imagining consists. This result does not itself satisfy a core desideratum on unifying accounts, since such accounts can be revisionist at least to the extent that it helps them satisfy core desiderata. Nonetheless, the account’s upholding and explicating the folk notion of imagining is an additional advantage that, to my knowledge, only it enjoys.

4 Applying the account part II: the intentionality of imagining

So far, I have been concerned primarily with the nature of imagining as a kind of mental process, that is, as a type of mental action. However, because the activity that imagining consists in is one of forming representations, a complete account of its nature requires discussion of its intentionality. As I noted in Sect. 2, the skillful action account holds that the agent selects the content of what she represents in imagining in light of the end she has in forming that representation. In this section, I show that the account adopts a qualified form of what Munro and Strohminger (2021) identify as “intentionalism.” According to intentionalism about the content of imagination, “whenever you intend to imagine something and act on that intention, the content of your intention about what to imagine determines the content [that] you imagine” (11848).Footnote 19 This formulation of intentionalism is unrestricted. By contrast, on the skillful action account, there are limits to what an agent can imagine that stem from the limited nature of human practical cognition in general. Just as successful action requires sufficient knowledge-how, sufficient sensitivity to the context of action, and efficacious performance, so too does successfully representing what one intends in imagination. On the qualified form of intentionalism put forward by the skillful action account, only when the agent’s practical cognition of her act of imagining achieves the status of practical knowledge does she imagine what she intends to. This account of the intentionality of imagining further enriches the characterization of the nature of active imagining proposed by the account.Footnote 20

The relation between intention and content in active imagining is, presumably, an aspect of the freedom of imagination. Some form of intentionalism is thus the norm in the literature on imagination. However, as Munro and Strohminger point out, there are cases where it seems that what is imagined diverges from what the agent intends to imagine. Let us focus on one such case of imagistic imagining inspired by Wittgenstein (1980). A tourist visits both King’s College and Trinity College. Later, she mixes up her past experiences in attempting to episodically remember the visits. She now misremembers her tour of Trinity College as being her tour of King’s College. She then intentionally imagistically imagines what she takes to be King’s College on fire. Intuitively, the agent misimagines King’s College on fire. Her image mischaracterizes King’s College as Trinity College and, thus, fails to represent the former appropriately. I grant that this case counts as a genuine instance of misimagining. It thus gestures at a genuine limit on the freedom of imagination that is tied to the etiology of the imagery involved.Footnote 21

The question, then, is how to square the possibility of misimagining with the intentionalist dimension of the freedom of imagination. According to the skillful action account, at its core, what goes wrong in cases of misimagining is a failure of an attempted imagining to match the agent’s practical cognition of what she is doing. Such failures can occur in more than one way. The agent can (i) fail to know how to imagine (appropriately), (ii) fail to know some fact upon which her success in this instance depends, or (iii) make so-called “mistakes in performance.” In the good case, the agent’s fixing the content of an imagining occurs as part of the exercise of her practical knowledge in intending to complete the relevant imaginative project. However, like all cognition, practical cognition is fallible such that it sometimes fails to reach the status of knowledge. An agent, in acting, can think they are doing one thing when in fact they are not.

The reasons for such failures in the bodily case mirror the ways that misimagining can occur. First, an agent can think he knows how to do something that he in fact does not know how to do, and, upon attempting to exercise what he takes to be a bit of knowledge-how, fails to do what he intends. For instance, he might think he knows how to tie a full Windsor knot but, in fact, does not know to make a second loop on the left side of the tie. His attempt at exercising what he takes to be knowledge-how to tie a full Windsor will at best result in a half Windsor. Second, an agent can know how to do something and set out to do it but fail to know some fact that the success of his performance depends on. For instance, he might know how to operate a manual water pump but not know that there is a hole in the water suction line. His attempt to pump water will likely result in pushing a lot of air out of the pump.Footnote 22 Finally, an agent can know how to do something and can know everything that he needs to in order to succeed in performing the relevant action but, nonetheless, his performance fails to realize his intention. For instance, he might know how to call an elevator and know that button A calls the one that he means to call. Nonetheless, in reaching for button A he might miss and press button B. In all three cases, what ends up happening fails to match the agent’s practical cognition.

Returning to imagining, for each way in which what ends up happening fails to match the agent’s practical cognition, the agent misimagines. In the King’s College case, the tourist’s failure falls within the second category. The tourist knows how to imagine buildings on fire but does not know that the images of burning buildings that she conjures are those belonging to Trinity College rather than those belonging to King’s College. In particular, she does not know that she has misattributed her memory-based image of Trinity College to her past experience of touring King’s College. This fact turns out to be pertinent to the success of her attempt to imagine King’s College on fire. She can only correct for the mistake if she is made aware of it. Now, consider an agent, an idle imaginer, who knows how to imagine that the floor is lava but does not know that she has been invited to play a game of ‘the floor is lava.’ Instead, she thinks that she has been invited simply to entertain the image or thought of the floor’s being lava and it is her taking herself to be so invited that prompts her to entertain the relevant image or thought. In this case, the idle imaginer fails to know that the end she has been invited to take up is engaging in the pretense. She is thus liable to misimagine because she is likely to fail to update her imagining in response to her or others’ pretense actions. She will likely fail to update her imagining in response to another player tossing a throw pillow onto the floor because she will likely fail to recognize that action as that player’s making a move in the game. The idle imaginer’s liability to fail to update in this case suggests that failures to know facts required for successful imaginative performance concern not just content or features of the context of action but also the point of imagining in a given instance.Footnote 23

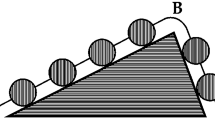

There are also failures of knowledge-how that result in misimagining. Such failures take at least two forms: an agent’s failing to know how to imagine something and her failing to know how to imagine such that she completes the corresponding imaginative project. Regarding the first form, a greenhorn orchidologist might not know how to imagine a king-in-his-carriage orchid because she is completely unaware of the species. Upon being told about the orchid, she might try to imagine it and conjure an image of an especially glorious-looking flower belonging to the Cypripedioideae genus. But she would be misimagining the orchid in this case, since king-in-his-carriage is of a genus of orchids with a peculiar look (Fig. 1).Footnote 24 Regarding the second form of failing to know how to imagine, a novice player of a game of pretense might not know how to imagine appropriately for engaging in that game. She might be just starting to learn the rules of ‘the floor is lava’ and, upon seeing another player toss a throw pillow onto the floor, not know to update her imagining. She might then attempt to avoid touching the throw pillow. She might think it is, say, a lava-resistant naval mine. In such a case, she would be misimagining the state of the game: unlike practiced players, she would not select an appropriate content, e.g., that an outcropping has just emerged from the lava flow.

Finally, there are mistakes in performance in imagining. An agent can know how to imagine in both of the relevant senses and can know everything that she needs to in order to succeed in her act of imagining but, nonetheless, her performance for some reason fails to match her practical cognition. Suppose our pretender is a practiced player of ‘the floor is lava’ and knows that another player has just tossed a throw pillow onto the floor. She might nonetheless fail to update and try to traverse the space without making use of the pillow. In such a case, she would be misimagining the state of the game, failing to imagine that an outcropping has just emerged from the lava flow. She might well feel silly for making this mistake. After all, she knows how to play and would otherwise immediately update her imagining upon seeing the throw pillow get tossed. Still, the content of her imagining failed to match her practical cognition with respect to carrying on the pretense and this mistake might well cost her her life in the game.

The three kinds of failure just listed each constitute a way that the agent misimagines. And each way of misimagining can occur via distinct routes. Each results in the agent’s failing to represent what she intends to. In each case, her intention thus “falls to the ground.” An intention’s falling to the ground is not its forever going unsatisfied or its being contradicted but, rather, its currently not being executed by what the agent is doing (Small, 2012, pp. 143–150). Other things being equal, the agent can pick her intention back up if (1) it is not too late to correct her imaginative act or it is not a one-off, (2) she does not change her mind, and (3) she is made aware of the relevant failure.Footnote 25 Indeed, upon learning that tying a full Windsor involves making a second loop, the agent tying his tie will undo the half Windsor and try again. Similarly, upon learning that there is a hole in the water suction line, the agent operating the pump will try to fix the hole or go find some other source of water (Small, 2012, p. 147). And, upon learning that he had pressed the wrong button, the agent calling the elevator will press button A. In all of these cases, the agent goes on to satisfy his intention by adopting the appropriate means once he has learned that what he actually did was not appropriate.

Holding the three conditions on picking up an intention fixed, let’s reconsider what happens in the cases of misimagining so far discussed. In the King’s College case, upon learning of her mistake, the tourist will use an image search engine for “King’s College” to relearn what it looks like, will attempt to correct her memory on her own, will (re)specify her intention to be that of imagining King’s College Trinity-College-wise and on fire, etc.Footnote 26 Upon learning that she’s been invited to play a game of ‘the floor is lava’, the idle imaginer will shift from merely entertaining the relevant imagery or thought to engaging in the pretense. Upon learning what a king-in-his-carriage orchid looks like, the greenhorn orchidologist will either correct her imagery or will (re)specify her intention to be that of imagining a king-in-his-carriage orchid Cypripedioideae-wise. Upon learning the relevant updating rules for ‘the floor is lava’, the novice player will go on to apply those rules to her imagining in continuing to try to play. Finally, upon learning that she had failed to update, the seasoned player will automatically update to include the new outcropping as among the walkable surfaces within the pretense.

In each case where the agent picks her intention back up, her correcting her mistake means that she does not ultimately misimagine. That is, in these cases, the agents successfully imagine King’s College on fire, that the floor is lava, and the king-in-his-carriage orchid, respectively. An agent’s being in a position to pick her intention back up and carry it to completion despite making mistakes suggests another way in which misimagining constitutes a failure to fully exercise the capacity to imagine. Indeed, misimaginings are in general relegated to defective portions of ultimately successful imaginings, instances where the agent overestimates her (current) imaginative ability,Footnote 27 instances where the agent gives up before successfully correcting her imaginative behavior, and instances where there is no chance for correction.

By providing a more robust account of imagining’s intentionality, the qualifications that the skillful action account makes to intentionalism further enrich the account’s characterization of the nature of imagining as paradigmatically a type of skillful mental action. What an agent imagines is what she intends to imagine just in case, other things being equal, her act of imagining matches her practical cognition of that act. Adding this qualified form of intentionalism to the skillful action account of imagining has the following two results. First, what an agent intends to imagine and, thus, what she ends up imagining are both shaped by the intention with which she imagines, namely, to pretend, engage with fiction, mindread, imagine for its own sake, and so on. Thus, the agent’s freedom to imagine is tempered by whatever end she is exercising that freedom for the sake of. Second, an especially important enabling condition for the agent’s imagining what she intends is her having had sufficient practice imagining and doing so in accordance with the principles guiding the relevant imaginative project. Just having the needed ideas in memory is not enough. The agent must be able to selectively combine elements of those ideas in constructing a representation and must be able to do so with a view to completing the corresponding project. So, according to the skillful action account, while it is true that in the good case the agent imagines what she intends to, what she can efficaciously imagine and what she can genuinely intend to imagine are both constrained by the shape of her capacity to imagine.Footnote 28

5 Addressing non-active imagining and mind-wandering

Because the skillful action account treats imagining as paradigmatically a type of skillful mental action, one might expect it to struggle accounting for passive imaginings like automatic imagining, involuntary imagining, or mind-wandering. Neither automatic nor involuntary imagining appear to be types of imaginative project nor appear to occur within such projects. And mind-wandering, at least when understood as “unguided attention” (Irving, 2016), appears to be a type of imaginative project that is by definition undirected by the agent. Indeed, all three appear to happen independently, if not entirely against, the agent’s will. One might think, then, that to the extent that the skillful action account emphasizes the centrality of the skillful mental action of imagining, it fails to countenance automatic imagining, involuntary imagining, and mind-wandering.

I give five responses on behalf of the account. First, starting with automatic imagining, many such instances might well be responses to an appropriate cue. At least in these instances, automatic imagining is not genuinely passive. This is unsurprising if we take imagining to be skillful. Indeed, skillful action in general depends heavily on automatic action: if the agent had to slow down and think through every movement involved in, say, playing piano every time she sat down to play, she would not be able to master the skill (Wu, 2016). Recall our painter from Sect. 3. Her filling in a bit of negative space might well be an automatic response to noticing that bare spot on the canvas. Likewise, our pretender playing ‘the floor is lava’ might imagine the emergence of an outcropping automatically in response to seeing another player tossing a throw pillow onto the floor. Much active imagining is (as it must be) automatic yet skillful, occurring without prior deliberation as a function of habit and in response to the appropriate cue.

Second, moving onto involuntary imagining, some instances of involuntary imagining will turn out to be disruptions in the functioning of mechanisms involved in construction. In that case, they are not instances of imagining at all but, rather, instances of defective construction. Hallucination after a head injury is a case in point. It would at the very least be wildly misleading to describe someone hallucinating after a head injury as imagining. He is at most suffering unbidden imagery as a result of damaged construction mechanisms in a way that is difficult or impossible for him to distinguish from genuine perception. It would be more apt to say that he is “seeing things” or “hearing things” with the inflection that the imagery is pathological in part by serving to mislead him. Third, other instances of involuntary imagining will turn out to be non-malfunctional instances of unbidden imagery or thought. Many biological mechanisms are liable to misfire despite not malfunctioning. Indeed, such misfires can be adaptive, say, when a prey detector’s being subject to many false alarms brings with it the occasional and much needed meal (Godfrey-Smith, 1992, pp. 297–308). Similarly, the mechanisms involved in construction are not foolproof. Even if infrequent, they can be activated in the absence of any appropriate stimulus. In that case, they will produce unbidden imagery or thought. This might be what happens, for instance, when people experience unbidden imagery as they are falling asleep, when they dream,Footnote 29 or when they suffer an earworm. Such cases are not unlike “mindless” scratching in response to a phantom itch. Such scratching does not remove an actual irritant from the skin but might nonetheless be adaptive if it is reflective of a tendency that is likely to activate in response to an actual irritant causing an itch. I also take it that cases of imagery-involving illusions induced, say, in the lab involve (deliberately) causing such mechanisms to non-malfuctionally misfire.

Fourth, still other instances of involuntary imagining will turn out to be action slips. Action slips occur when an action is tokened in response to what would otherwise be an appropriate cue but where performance of that action is inappropriate for the context (Amaya, 2013, 2020; Mylopoulos, 2022). Skillful and habitual actions are both prone to slips. For instance, an agent can find herself driving her normal route home despite having formed an intention to stop by the grocery store prior to getting into the car. Getting into the car places her in surroundings likely to trigger the habit of taking her normal route.Footnote 30 If, as the skillful action account has it, active imagining is the central imaginative kind and is a type of skillful action then we should expect imagining to admit of occasional slips. Some instances of automatic imagining fall into this category, as will some instances of unbidden imagery or thought. In cases of imaginative action slips, the capacity to imagine is likely triggered by a cue for engaging in some imaginative project in the absence of the agent’s being engaged in that project. Just like in the bodily case, the agent can become aware of these slips in imagining and can usually correct her imaginative behavior.

Fifth, and finally, the first and fourth responses given to address automatic and involuntary imagining apply as well to mind-wandering. Mind-wandering deserves a more thorough treatment than I can give it here. However, I can provide some reason for thinking that the skillful action account of imagining can incorporate mind reading as an imaginative project. I consider automatic mind-wandering and mind-wandering that starts as an action slip in order. First, recall that, following Irving (2016), mind-wandering is “unguided attention” where such guidance is consciously experienced. Attention is unguided if its movement from one topic to another does not cause the agent to feel “pulled back” from what she was previously focused on. That is, mind-wandering often lapses into thought about future tasks and wider goals that are more pressing or feel more rewarding to think about (Shepherd, 2019). In which case, it is fully consistent with the lack of the feeling of being pulled back that mind-wandering is primarily a matter of automatic habitual or skillful seeking out of behavior that is more efficient or rewarding than what the agent is currently doing. The skillful action account can therefore classify such seeking-out as a subset of a type of imaginative project, namely, (imagistic) hypothetical or counterfactual thought about contingent matters of fact (De Brigard, 2014).

For example, while making dinner, I am also writing this paper. My thoughts are liable to drift towards the metaphysical structure of action and its relation to imagination as I slice, mince, sauté, and so on. Yet, I do not experience being pulled back from my cooking and recognize that the task of writing this paper is, relative to my larger goals, more pressing than eating the meal that I am making right now.Footnote 31 In this case, my mind-wandering is my automatically seeking out a more pressing goal automatically in response to an appropriate cue, say, the stress or anxiety I am feeling about completing it. Such cues can be external as well: a bored elementary school student might automatically mind-wander to thoughts of play in response to seeing the school’s lawn outside the window. What is important is that the imagining the student and I engage in is an automatic construction of a representation whose content is given by the more pressing (or fun) goal we would rather be engaging in, e.g., work or play, respectively. That we do not experience such thought as a distraction to be corrected and, so, is attentionally unguided is no bar on our mind-wandering being something we each do, albeit without having to use attentional resources in an attempt to so wander. The paradoxical air around mind-wandering is that it is an action that we cannot perform deliberately. But so too are certain kinds of meditation or mindfulness practices. In all three cases, the key to dispelling the air of paradox is seeing that a lack of guidance or deliberate attempts is consistent with automatic performance.

Similarly, it is consistent with the skillful action account that some instances of mind-wandering begin as action slips. An agent’s feeling hungry at work might cause her to think about dinner, where this thinking conflicts with her operative intention to stay focused during a work meeting. The agent can then choose to continue engaging in this imaginative project, taking an active role in its development. She might find fantasizing about her upcoming meal a more worthwhile endeavor. Like other slips, one often notices or finds themselves mind-wandering. In such cases, one then either corrects the behavior by refocusing attention to the task at hand or elaborates the wandering.Footnote 32 If the agent refocuses, she stops the mind-wandering. If she elaborates the mind-wandering then she transitions from this imaginative project to another, most likely directed daydreaming. Either way, these instances of mind-wandering can also be handled by the skillful action account by placing their initial phases within the category of action slips.