Abstract

Self-verifying judgments like I exist seem rational, and self-defeating ones like It will rain, but I don’t believe it will rain seem irrational. But one’s evidence might support a self-defeating judgment, and fail to support a self-verifying one. This paper explains how it can be rational to defy one’s evidence if judgment is construed as a mental performance or act, akin to inner assertion. The explanation comes at significant cost, however. Instead of causing or constituting beliefs, judgments turn out to be mere epiphenomena, and self-verification and self-defeat lack the broader philosophical import often claimed for them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the Second Meditation, Descartes’s Meditator judges that he exists. The reasoning preceding this judgment is elementary enough for beginning students to grasp, but it has proven surprisingly difficult for interpreters to reconstruct. Notably, the Meditator gives no argument for the conclusion that he exists; the famous “cogito, ergo sum” appearing only in other work. Instead, we find an argument for the distinct conclusion that the proposition I exist is self-verifying, in roughly the sense that a thinker’s affirming it guarantees its truth.Footnote 1

It might seem obvious that establishing I exist as self-verifying justifies the Meditator in affirming it (or judging it to be true). But it is not obvious how. It might be obvious if the Meditator could simply infer the conclusion I exist from the premise that I exist is guaranteed to be true if affirmed. But this inference is not deductively valid. The premise is a necessary truth, so it cannot entail the contingent truth that someone exists, let alone that any particular person does. Non-deductive inference is perhaps less straightforward, but it is at least hard to see how this premise could provide anything like inductive, abductive, or probabilistic support for the Meditator’s or anyone else’s existence. So it is no wonder this passage has proven so puzzling, apparently even for Descartes himself. When pressed, he often seems to concede that I exist is inferred from a distinct, introspectively known premise I think. Yet as I’ll discuss, this does not do justice to the idea that self-verification is relevant to the judgment’s justification.

Recent discussions of self-knowledge and epistemic paradox have emphasized a related phenomenon. Loosely inspired by G. E. Moore, many philosophers claim that propositions of the form p, but I don’t believe that p are self-defeating, in the sense that one’s affirming them guarantees their falsity. The idea is this. Judging guarantees believing, and believing a conjunction guarantees believing each conjunct. Thus in judging a Moorean conjunction to be true, one believes its first conjunct, and thus guarantees its second conjunct is false.

Many philosophers have thought this makes Moorean judgments irrational.Footnote 2 But if this is so, it is not because they are logically inconsistent, or even because they cannot be supported by one’s evidence. Here is one example adapted from Declan Smithies (2016) and Ralph Wedgwood (2017, p. 45):

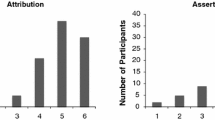

Stubborn Stella: Stella has conclusive meteorological evidence supporting that it will rain. But Stella stubbornly withholds belief that it will rain, and she can tell by introspection that she withholds belief.

Stella knows that she does not believe it will rain. But her meteorological evidence supports that it will rain. So her total evidence supports the Moorean conjunction It will rain, but I do not believe that it will rain. Even so, Smithies and Wedgwood think Stella is in no position to rationally affirm this conjunction.

While common, these claims are puzzling. We usually think beliefs are rational when they are supported by one’s evidence. And yet self-verifying judgments apparently can be rational even when evidentially unsupported, and self-defeating ones irrational even when supported. How can this be?

This paper argues that the solution requires us to understand judgment as a mental act, subject to norms of practical reason. Sections 2, 3, 4, and 5 explains the idea informally, as it applies to the key examples of Moore’s paradox and the cogito. The nuts and bolt are developed more formally in Sect. 6, with some specific applications in a technical appendix. After developing the account, I turn to the broader significance of self-verifying and self-defeating judgments. Section 7 examines what the mental act of judgment must be like, and what its relation to belief must be, to vindicate the account. And Sects. 8 and 9 turn to some popular claims about the broader import of Moorean and cogito-like judgments. Many authors claim they are not mere idle curiosities, but rather illustrative of central features of the nature of self-knowledge.Footnote 3 But my account casts doubt on these claims.

2 The Cogito

The Second Meditation begins in extreme skeptical doubt. Yet even without evidence or premises from which to proceed, the Meditator soon finds himself able to affirm his own existence. At least for agents who reflect on the matter in the right way, it seems:

(Cogito) It is rational to affirm I exist.

But why is affirming one’s existence rational? On my reading Descartes had two distinct accounts, though I see no evidence that he saw them as distinct. Some commentators think they can reconcile the apparent inconsistencies in his various remarks, but I’m less optimistic.Footnote 4 My aim is not so much a faithful interpretation of Descartes’s overall view as a reconstruction of one strand of his thinking with a particular contemporary relevance.Footnote 5

Start with the account that seems to me dominant in Descartes’ own writings, though it will not be my focus. I call it the introspective account, because it has affirmation of one’s existence supported by introspective knowledge of one’s particular thoughts, doubts, sensory perceptions, and the like. Descartes is not altogether clear about the nature of this introspective knowledge.Footnote 6 But what is clear is that it is available by at least the latter half of the Second Meditation, where the Meditator is said to know:

(Sensory Perception) I seem to see a piece of wax.

And what follows this is the clearest endorsement of the introspective account in the Meditations (CSM II 22).Footnote 7 The Meditator argues that while Sensory Perception provides some evidence for the wax’s existence, it “entails much more evidently” that he exists, since:

(Sensory Perception Guarantee) When I seem to see a piece of wax, it is simply not possible that I who am now thinking am not something.

How exactly are Sensory Perception and Sensory Perception Guarantee supposed to justify the Meditator’s affirmation of his existence? Most obviously, they might serve as premises from which he infers I exist. Alternatively, maybe I exist is supposed to be inferred directly from Sensory Perception, with Sensory Perception Guarantee appearing only as the Meditator’s post hoc endorsement of the inference (e.g., Peacocke, 2012). Or maybe knowledge of I exist is supposed to be non-inferential, but still parasitic upon knowledge of these premises, the way intuitive knowledge of God’s existence can be parasitic on the prior consideration of arguments (e.g., Markie, 1992). These readings disagree on important matters involving intuitive and deductive knowledge, and the priority of particular knowledge over general principles. But for my purposes, their similarities matter more than these differences.

Besides this passage in the Second Meditation, the introspective account is suggested or directly endorsed in many other writings, beginning with correspondence preceding the Meditations (CSM III 98), and continuing in the Fifth Replies (CSM II 244) and later the Principles (CSM I 195).Footnote 8 It also fits the famous slogan “Cogito, ergo sum,” which suggests knowledge of I exist proceeds by inference from an antecedently known premise about one’s thinking. While the slogan is absent from the Mediations, it appears in earlier and later writings, and in the replies to the Meditations.Footnote 9 Finally, though I won’t explore the matter here, I suspect the introspective account better coheres with other aspects of Descartes’s project, such as his argument for mind–body dualism, and his view that all knowledge, including knowledge that one exists, is rooted in clear and distinct perception.Footnote 10

But despite all this, I agree with Jaakko Hintikka (1962) that the Meditations contains another account of Cogito, one invoking self-verification.Footnote 11 I do so notwithstanding partial agreement with critics who say Hintikka overstates the textual support for the account, and fails in his attempt to analyze (what I call) self-verification (e.g., Feldman, 1973; Frankfurt, 1966, 1970, Ch. 10). Despite these misgivings, the central discussion of the cogito in the Second Meditation seems to me undeniably preoccupied with the self-verifying character of I exist:

…I have convinced myself that there is absolutely nothing in the world, no sky, no earth, no minds, no bodies. Does it follow that I too do not exist? No: if I convinced myself of something then I certainly existed. But there is a deceiver of supreme power and cunning who is deliberately and constantly deceiving me. In that case I too undoubtedly exist, if he is deceiving me; and let him deceive me as much as he can, he will never bring it about that I am nothing so long as I think that I am something. So after considering everything very thoroughly, I must finally conclude that this proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind. (CSM II 16–17)

What guarantees the Meditator’s existence in this passage is not an arbitrary perception of some object like a piece of wax. Instead, the mental state guaranteeing the truth of I exist is simply his affirming that very proposition, or else some other state closely related to his affirming it, like his conceiving it or being potentially deceived about it.

Can an introspective reading handle this passage? It might be claimed that the Meditator still needs introspective premises about the relevant mental states, in order to affirm his existence on their basis. And to be sure, the Meditator first affirms his existence upon remarking:

(Conviction) I convinced myself that there is nothing in the world,

and,

(Conviction Guarantee) If I convinced myself of something then I certainly existed.Footnote 12

So it might seem introspective knowledge of his convictions is supposed to support affirmation of the Meditator’s existence, just as awareness of sensory perceptions later does.

But I read things a little differently. When the Meditator remarks on these thoughts and convictions, it is initially merely to track the dialectic, not to introduce substantive psychological premises.Footnote 13 The dialectical remarks then prompt the realization that his having thoughts and convictions guarantees his existence. With I exist thus established as self-verifying, there is no further need for introspective premises supporting it.

This reading seems favored by the remainder of the passage. Rather than immediately concluding that he exists, the Meditator continues with what seems intended as an elaboration of the same point. And here the point clearly is not to infer his existence from the premises:

(Deception) There is a deceiver constantly deceiving me,

and,

(Deception Guarantee) In that case I too undoubtedly exist, if he is deceiving me.Footnote 14

Surely Descartes does not intend for the Meditator’s knowledge of his existence to rest on the false premise that there is a deceiver. Instead, the point is to stress that even if there were such a deceiver, the Meditator still could not be deceived in affirming his own existence. Knowing this, the Meditator does not need Deception as a further premise supporting his existence, and by the same token does not need Conviction, either.

This reading is further reinforced by what we are told is the passage’s ultimate conclusion:

(Conception Guarantee) I am, I exist is true whenever it is put forward [profero] by me or conceived in my mind.

This conclusion is rather notably not equivalent to I exist. And that is for good reason on my reading, since the Meditator’s point never was to offer an argument for his existence. Rather, it is to establish I exist as self-verifying. If one affirms or even conceives this proposition, then by that very act one guarantees its truth, no matter the origins of one’s thought, or one’s vulnerability to deception more generally.

At this point, the Meditator moves on to consider the nature of “this ‘I’ … that now necessarily exists.” Yet it is left unexplained how the existence of any such thing follows necessarily from Conception Guarantee, an existentially noncommittal observation about the proposition I exist. (If Homer conceived I exist then it was true, but it hardly follows that Homer existed.) For the Meditator’s existence to follow another premise is needed, for example:

(Conception) I am conceiving the proposition I exist.

It would be rather anticlimactic, however, for the Meditator at this point to affirm his existence based on an introspective premise about what he is conceiving. Why not just skip all the rigmarole about self-verification, and introspect some arbitrary transient thought or sensory perception?

Harry Frankfurt (1970, Ch. 10) has the only answer I know of.Footnote 15 It is that Conception is true when the Meditator considers his existence, unlike (say) Sensory Perception, which is true when he looks at wax. So whenever the question of his existence happens to be on the Meditator’s mind, Conception will be among the available introspective premises for settling the matter. Frankfurt thinks this is supposed to lend knowledge of one’s existence a kind of stability that it would not have if it depended on premises about transient sensory perceptions. If he is right, then Descartes never really wavered from the introspective account, like Hintikka and I claim.

But Frankfurt’s answer leaves something out. Conception Guarantee is just the final articulation of an idea that is already present in Conviction Guarantee and Deception Guarantee. While these thee claims are not interchangeable, there is plausibly supposed to be a common thread uniting them. Yet in the context of skeptical doubt, one might not be able to know Conviction introspectively, simply because one is not yet convinced of anything. And one never can know Deception, since God is not a deceiver. So neither Conviction Guarantee nor Deception Guarantee gets one anywhere close to affirming one’s existence in the way Frankfurt suggests. Conception Guarantee thus stands alone in a way that seems unsupported by this passage, not to mention other writings where it is Deception Guarantee that gets top billing.Footnote 16

So I think the best reading holds that affirming I exist is rational because self-verifying; because its truth is guaranteed just by one’s affirming it.Footnote 17 There is no need for perceptual premises like ‘I am walking’, which on any reasonable reading are doubtful at this stage of the Meditations. But there also is no need for introspective premises about what thoughts one is having, whatever we say about their antecedent doubtfulness. This is the first central commitment of what, following Hintikka, I call the performative account of Cogito. What is less clear is how the fact that I exist is self-verifying justifies one in affirming it, without recourse to further premises or evidence from which it can be inferred. Descartes never says, but the second key commitment of the performative account, which I defend in what follows, fits well with his other views. It is that affirming a proposition in one’s mind, like publicly asserting it and unlike believing it, is a performance or act. If you are in any doubt as to your existence, you should not on that account hold back from asserting I exist in speech, out of fear you will end up asserting a falsehood. And the same goes for affirming it in one’s mind. If skeptical doubts land you in the position of deliberating over whether to affirm I exist, despite uncertainty as to your existence, you should not let that stop you from affirming. Go ahead and do it, Conception Guarantee tells you, and you cannot go wrong.

3 Self-verification

The difficulties raised by Cogito are just one instance of a more general puzzle. To a first approximation, it is tempting to accept something like:

(Self-Verification) If ϕ is self-verifying, then it is rational to affirm ϕ.

But this is incompatible with:

(Evidential Support) It is rational to affirm ϕ if and only if ϕ is supported by one’s evidence.

These claims are incompatible because many self-verifying propositions are unsupported by one’s evidence. For every number n, propositions like I am now thinking of n, and I hereby affirm that n is a number are self-verifying. But one’s evidence can hardly support for each number that one is now thinking of it, or that one ever has or will affirm it is a number. Perhaps somehow one still can be justified in spontaneously affirming, say, that one is thinking of the number 36. But that is not because one’s antecedent evidence must support it in the sense of assigning it high probability.

To dramatize the point, consider a fanciful example where you know some brain state S is identical to judging one is in S. Both I am in S and I am not in S might be self-verifying, but your evidence cannot support both.

One might try to reconcile Self-Verification and Evidential Support by appealing to the introspective evidence that you will have after affirming a self-verifying proposition. Once you affirm you are thinking of 36, it could be claimed, you will know by introspection that you are doing so. And then your evidence will support that you are thinking of 36. Likewise, if you affirm I exist, then you can know by introspection that you affirm this, and so will have evidence entailing that you exist. And so in general, Self-Verification never requires there to be a time at which one both rationally affirms a self-verifying proposition and lacks evidence for it.

But I doubt the attempted reconciliation really succeeds. If you acquire evidence supporting a proposition only after affirming it, then this evidence cannot be what motivates the affirmation. So the appeal to introspection cannot explain how self-verifying judgments are rationally motivated. It requires that you affirm them for no reason, only for the reasons to come once it is too late. And if you currently have no reason to affirm a proposition, then it is not true that it is rational for you to affirm it.Footnote 18

So Self-Verification really is incompatible with Evidential Support. Even so, I think there are widely acknowledged rational norms that support Self-Verification. The hitch is that they are not the kinds of evidential norms we usually associate with belief and judgment, but rather practical norms that govern voluntary actions like assertion.

Because assertions are actions, what it is rational to assert can come apart from what one’s evidence supports. Sometimes one might have practical reasons to flat out lie. More commonly, one’s practical reasons might bear on which propositions out of the many supported by one’s evidence are worth asserting. Yet we might still expect that if we bracket off those kinds of practical considerations, and focus just on the narrow aims of asserting any and only truths, then the rationally assertable propositions will coincide with the evidentially supported ones.

While this is a natural thing to expect, it isn’t true. Suppose that for whatever reason you aim to assert something true just now, and do not much care what truth it is. Even if you lack any evidence that you will just now refer in speech to the number 36, you still might have sufficient practical reason to assert I am now referring to 36. Since you know that your asserting any proposition of this form will guarantee its truth, you can simply decide to assert one of your choosing.

Importantly, you do not need to assert first and then, once you realize you are making the assertion about 36 rather than some other number, for the first time gain justification for it. Sufficient reason for making the assertion is available antecedently, before you know you will make it. That is why the decision to assert can be rational in the first place.

Of course in practice nobody really aims to assert truths without concern for which truths they are. So in the middle of a lecture, it will not be all-things-considered rational to assert out of nowhere I am now referring to 36 or even 36 is not the capital of Australia. Maybe it also will not be all-things-considered rational to inwardly affirm these things when there are more important matters to attend to. If so, Self-Verification and even Evidential Support will need qualification. But even if so, we still will be left with a puzzling gap between rational affirmability and evidential support. At least for self-verifying propositions that are worth affirming, affirmation can be rational even without evidential support. And even for ones that are not worth affirming, the reason why affirming them is potentially irrational is not that one’s evidence fails to support them.Footnote 19

Perhaps this is why the resemblance between judgment and assertion was stressed by Hintikka (1962, pp. 13 and 18–19), not to mention Descartes himself (CSM II 17).Footnote 20 Just how literally we are to understand the comparison I am not sure. Though the Meditations takes the form of an inner monologue, perhaps it is merely supposed to be the linguistic expression of thoughts that may not be formulated in natural language by the Meditator. But even if so, there remains a deeper connection between the Meditator’s affirmations and public assertions. For both are, on Descartes’s voluntarist view, free and voluntary acts.

For the historical question of how to interpret Descartes’s cogito, it is enough that he accepted voluntarism. But as we will see, many philosophers have thought self-verification and a related phenomenon of self-defeat are of more that purely historical interest. So it is a pressing matter whether the performative account commits us to an untenable voluntarism. After considering self-defeat in Sects. 4 and 5, I turn in Sects. 6 and 7 to these pressing matters.

4 Moore’s paradox

G. E. Moore famously observed that it is “absurd” to assert propositions of the form ϕ, but I don’t believe that ϕ. Subsequent authors like Sydney Shoemaker (1996, Chs. 2, 4, and 11) have considered judgments enough like assertions to underwrite a related claim:

(Moore) It is irrational to affirm ϕ, but I don’t believe that ϕ.

Indeed, Moore is often considered an obvious datum, which an account of Moore’s paradox should explain (Chan, 2010; de Almeida, 2001, 2007; Fernández, 2005 and 2013, Ch. 4, p. 112; Gibbons, 2013, pp. 3 and 231; Heal, 1994, p. 6; Kriegel, 2004; Moran, 2001, p. 70; Setiya, 2011; Silins, 2013, p. 297; Smithies 2012, 2016, 2019; Williams 2006, 2007).

But even if we regard Moore as obvious, we should still find it puzzling. As Moore himself emphasized, Moorean conjunctions are logically consistent. Indeed, many of them are true. For there are many truths I do not believe, either because I have a false belief or no belief at all on the matter—and for each one of these unbelieved truths, the corresponding Moorean conjunction is true. What is more, I myself can recognize that there are many true Moorean conjunctions, at least in the abstract. And as Stubborn Stella brings out, there can at least be certain cases where particular Moorean truths are supported by an agent’s own evidence. Given all this, how can it be in general irrational to affirm Moorean conjunctions?

A popular answer holds that it has something to do with Moorean conjunctions being self-defeating, in the sense that one’s affirming them guarantees they are false (Shoemaker, 1996, p. 76; Smithies, 2016, 2019; Sorensen, 1988, Ch. 1 and p. 388; Wedgwood, 2017; Williams, 1978, p. 165; Green and Williams 2011, pp. 249–250. See also Briggs, 2009, p. 79). This follows from two key premises; first, that affirming a proposition guarantees believing it, and second, that believing a conjunction guarantees believing each conjunct. For suppose one affirms the conjunction It will rain, but I don’t believe it will rain. By the first premise, one is guaranteed to believe this conjunction, and then by the second premise guaranteed to believe its first conjunct. But that guarantees the second conjunct, and hence the whole conjunction, is false.

Are these two premises plausible? This might depend on what exactly we mean by ‘guarantees’, and what we think the relation between judgment and belief is. These questions are more pressing for Moore’s paradox than for the cogito. One’s affirming I exist seems to metaphysically suffice for one’s existence, but it is less obvious that affirming a Moorean conjunction metaphysically suffices believing each conjunct. For now, I will leave these matters open. But in Sects. 6 and 7 , I will argue Moore is most plausible if ‘guaranteeing’ is given an epistemic rather than metaphysical reading, so that affirming a conjunction just needs to be sufficient evidence for believing its conjuncts.

5 Self-defeat

Even if we think Moorean conjunctions are self-defeating, that still leaves us with a puzzle. The fact that a Moorean proposition must be false if affirmed does not entail it is false. This is just one instance of a broader tension between:

(Self-Defeat) If ϕ is self-defeating, then it is irrational to affirm ϕ,

and

(Evidential Support) It is rational to affirm ϕ if and only if ϕ is supported by one’s evidence.

Even if it were denied that Moorean conjunctions are self-defeating, or that they can be supported by one’s evidence, the broader tension between these claims stands. If one affirms I am not thinking of the number 36, for example, this guarantees in whatever sense you like that the proposition affirmed is false—though presumably one could have strong inductive evidence supporting its truth. If so, Self-Defeat is incompatible with Evidential Support.

This incompatibility seems widely presupposed in discussions of epistemic paradox. Suppose you know brain state S’ is identical to judging that one is not now in S’. That makes I am not in S’ self-defeating; affirming this proposition will guarantee one is in S’, in which case it is false. And unlike a Moorean conjunction, the proposition also is guaranteed to be true if one does not affirm it. If one does not judge that one is not now in S’, then one is not in S’. This peculiar feature of the proposition is thought to make it especially paradoxical, since unlike Moorean conjunctions, one cannot straightforwardly avoid irrationality by withholding judgment.

So what should you do? On Earl Conee’s view (1987, p. 327), you should refrain from affirming I am not in S’. On David Christensen’s (2010, Sec. 6), you are in violation of a rational ideal whether you affirm it or not. On Roy Sorensen’s, you should refuse to believe that a state like S’ exists, no matter your evidence (1988, Ch. 11). Later on I will favor Conee’s view, applied to judgment if not belief. For now, consider what all these views have in common. On all of them, whether you should affirm the self-defeating proposition does not depend on what evidence you happen to possess regarding its truth. For example, none let the rationality of judging that you are not in S’ turn on whether you have inductive evidence that you are not in S’.

Why should your evidence be irrelevant in this way? As with the cogito, some authors favor a broadly introspective account (Salow 2019, Shoemaker, 1996, Kriegel, 2004, Silins, 2012, 2013, and esp. Smithies, 2016, 2019). It says a self-defeating proposition’s probability on your current evidence is irrelevant because your evidence will change as soon as you affirm it. That is, if you were to affirm it, you would be able to know introspectively that you did so. In that case, you will be in a position to infer from your new evidence that the proposition is false. So even if you initially have sufficient justification to affirm a self-defeating proposition, that justification vanishes once you do affirm it, and introspectively come to know that you have.

But even if so, the introspective account still has trouble with rational motivation. If I am rational, then I will refrain from affirming a self-defeating proposition in the first place. I won’t first affirm it and then immediately regret it upon introspectively learning that I have done so. If this is right, it seems I must have available antecedent reasons to refrain from affirming a self-defeating proposition, even before I can know by introspection that I in fact do so.

As with self-verification, I think a better account holds that judgment, like public assertion, is an act or performance. Suppose you have sufficient inductive evidence that you will make no assertions right now referring to the number 36. Even if your aim is to speak the truth, you still have reason not to assert this. For you can know that if you were to assert it, then it would be false. Importantly, you do not need to assert first and then immediately regret it, once you realize you have done so. The reasons against asserting are available antecedently.Footnote 21

Perhaps thinking along these lines is why many discussions of Moore’s paradox emphasize a commonality between belief and assertion (Green and Williams 2007, p. 3; Hájek, 2007, p. 219; Moran, 2001, p. 70; Peacocke, 2017; Shoemaker, 1996, pp. 78–79; Silins, 2012; Smithies, 2016, 2019; Williamson 2000, pp. 255–256). If judgments resemble assertions in the ways that matter, then we can likewise explain Self-Defeat. But what are the ways that matter? And do judgments really resemble assertions in those ways? In the next two sections, I will address this and other questions, and give a detailed performative account in place of the schematic one offered so far.

6 The performative account

Let’s take stock. The performative account of Cogito and Moore says that I exist is rationally affirmable because self-verifying, and Moorean conjunctions are unaffirmable because self-defeating. But self-defeating propositions might be supported by one’s evidence, while self-verifying ones might not be. And so we have a puzzle. For most ordinary propositions, we think, Evidential Support holds. It is irrational to affirm a proposition if one’s evidence does not support it, and rational if it does. So what makes self-verifying and self-defeating propositions any different? The performative account’s answer is where it gets its name; it says it is because judgment is a performance or act. The next two sections develop this answer, which has so far only been sketched.

We will get back in Sect. 7 to the question what it means to say judgment is an act. Does it require judgments to be voluntary, for example? This section considers a different question: Assuming judgments are acts, how does that allow exceptions to Evidential Support?

Here is one possible answer. Evidential reasons for judgment are alethic, or truth-directed. But acts, or at least voluntary ones, should be responsive to the full range of an agent’s reasons, including practical ones. One’s evidence can support that 36 is not the capital of Australia, but maybe it is irrational to waste one’s time making assertions or judgments about the matter. And maybe it even could be rational to make judgements against the evidence, if one’s practical reasons are strong enough. Presumably unsupported assertions can be rational, for example in order to reassure an insecure interlocutor. If inner affirmation is an act like assertion, maybe it can be rational to affirm something without evidence. Just because it makes me happy, I can affirm I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.

That is one way voluntarism about judgment lets us reject Evidential Support. But it is the wrong one. The exceptions to Evidential Support raised by self-verifying and self-falsifying propositions do not involve practical reasons like this. It is rational for Descartes’s Meditator to affirm I exist precisely because he aims to affirm truths, and it can be irrational for Stubborn Stella to affirm a Moorean conjunction just because she aims not to affirm falsehoods. So the right account of Cogito and Moore had better be compatible with one’s aims being the purely alethic.

Thus the performative account must reject a widespread assumption about deliberation under alethic aims, namely that:

(Transparency) If one’s aims are alethic, deliberation about whether to affirm ϕ is transparent to deliberation about whether ϕ.Footnote 22

Fans of Transparency say that deliberation about what to affirm automatically gives way, or is transparent to, deliberation about what is true. But even if the is often the case, the phenomena of self-verification and self-defeat give us good reason to reject it as a universal rule. Just compare judgment to assertion. Even if your only aim is to speak the truth, it can be rational to assert things that your evidence does not support, like propositions of the form I am referring to the number n. There is something funny about this. Your aim is to assert the truth, and yet for every n there is a lack of transparency between deliberations over whether you are (or soon will be) referring to n and whether to assert I am referring to n. How can this be?

Here’s how. Practical deliberation is concerned with how to intervene in the world. Thus it is concerned not with the question what is the case, but of what will or would be the case if the relevant intervention is made. So if you are deliberating about whether to assert ϕ, reasons to do so need not bear directly on whether ϕ is true. They need only bear on whether ϕ will or would be true if you asserted it. You might therefore have sufficient reason to assert that you are referring to 36, for example, even if your evidence does not support that you are (or soon will be) referring to 36.

If affirmation, like outer assertion, is a performance or act, then it likewise is up to you whether to affirm that you are thinking of 36. Rather than deliberating about whether you are thinking of 36, you can simply deliberate about whether to affirm that you are. And so there will be no need for evidence that you are thinking of 36, not even introspective evidence.

I hope this rough idea is intuitive enough. But I want to do more than present it impressionistically. It can be made more precise using formal theories of rational decision like causal decision theory (CDT), evidential decision theory (EDT), and graded ratificationism (GR).Footnote 23 These theories disagree on important matters of detail, but they agree on enough to offer independently motivated predictions about which judgments are rational, on the assumption that judgments are acts. And what they say is that self-verifying judgments are rational, and self-falsifying ones irrational.Footnote 24

Suppose you are deliberating whether to assert ϕ. Refraining is neutral, and asserting is associated with either good outcome G or bad outcome B. When will it be rational to assert? Despite disagreeing on finer points, all these theories agree about the basic shape of the answer. Where A(ϕ) is that one asserts ϕ, doing so is rational iff:

Here Pr is one’s probability function, which assigns to its arguments the appropriate probabilities given one’s evidence. So (1) has the assertability of ϕ depend in part on the values of Pr(G||A(ϕ)) and Pr(B||A(ϕ)). For now, think of these as the probabilities of asserting being associated in the right way with outcomes G and B. Associated how, exactly? This is where our theories disagree. It might be the probability of the outcomes if one asserts, or the probability that the outcome would have occurred if one were to assert, or something else. These disagreements can affect how the performative account applies to particular cases, notably Moorean judgments, as discussed in the appendix. For now I will stick to the main thread.

The other element in (1) is v, one’s value function. It assigns to outcomes numerical values representing their degree of goodness. So (1) also has the rationality of affirming depend on how good G is and how bad B is.

Turn now from assertion to judgment. Our concern is what judgments are rational given the alethic aims of affirming truths but not falsehoods. So we can henceforth take v to be one’s alethic value function, which represents solely one’s alethic aims of judging that ϕ if it is true and not if it is false.Footnote 25 Maybe more practical considerations can be relevant to the all-things-considered rationality of a judgment, such as whether the topic is worth making judgments about, or even more straightforwardly prudential concerns. If so, the focus on alethic value might oversimplify things. Still, I think the oversimplification is harmless. The important thing is that even setting practical considerations aside, the rationality of a judgment still can come apart from evidential support.Footnote 26

Where J(ϕ) is that one judges that ϕ, T is that one thereby affirms a truth, and F that one thereby affirms a falsehood, judging that ϕ will be rational iff:

which reduces to:

Thus formal theories of practical rationality say it is rational to affirm some proposition ϕ just in case (3) is satisfied. The right hand side of (3) sets a threshold for judgment, based on the relative value of making a true judgment on the matter compared to avoiding a false one. One could allow it to vary between agents, if one adopts a Jamesian permissivism about how “trigger happy” one should be with judgment and belief, or between contexts, if one wants the threshold for judgment to vary with some parameter like the practical stakes. But for simplicity, we can suppose it is a constant.

The important thing for us is what it takes for a proposition ϕ to clear the threshold. It is a matter of the probabilities assigned by one’s evidence. But according to the left hand side of (3), the relevant probabilities are not Pr(ϕ) and Pr(~ ϕ). Instead they are Pr(T || J(ϕ)) and Pr(F || J(ϕ)). For most propositions the difference does not matter; the probability that one will or would affirm a truth (or falsehood) if one affirms ϕ will just be the probability that ϕ is true (or false). But these probabilities can diverge, particularly when:

This is exactly what happens with self-verifying and self-defeating propositions. Consider for example I am thinking of 36. This proposition might be improbable given one’s evidence. And yet if one affirms it, it is guaranteed to be true. Where t is that one is thinking of 36:

The upshot is that formal theories of practical rationality, applied to judgment, vindicate Self-Verification at the expense of Evidential Support. For I am thinking of 36 to be rationally affirmable, what matters is not whether its probability clears the threshold for judgment, but whether a distinct probability does. And the converse goes for self-defeating propositions, like I am not thinking of 36. Even if its probability is high, the probability that matters for affirmability still will not be.

This is enough to show the performative account of Self-Verification and Self-Defeat is not arbitrary or ad hoc. Instead, its key claims are predictions of entirely general and independently motivated theories of practical rationality. But some further details still matter for the application to the cogito and Moorean conjunctions. A technical appendix says more about what’s under the hood.

7 Voluntarism about judgment and belief

We have just seen how the performative account vindicates Self-Verification and Self-Defeat. But the catch is that it must construe judgments as performances or acts. What does this mean for the nature of judgment, and its relation to standing states like beliefs and credences?

Descartes accepted the voluntarist view that judgment is a free and voluntary act of the will. But accepting this ourselves might seem to commit us to an implausible voluntarism about belief, on which we can will ourselves into the state of belief as we see fit. If judgments If the performative account is committed to doxastic voluntarism, that might be a problem.

A number of responses are consistent with the main claims of this paper, but there is one I think is probably best. If you are not worried about it, you can skip to Sect. 8.

A first response is to accept doxastic voluntarism (Weatherson, 2008). While this would be good news for the performative account I’m afraid it’s too good to be true. It is arguably metaphysically impossible to believe at will, and is at least psychologically difficult for us (Feldman, 2000; Hieronymi, 2006; Kelly, 2002; Rinard, 2017). If offered a cash prize for believing the capital of Australia is Sydney, for example, it seems you would not be able to do it, even if you wanted to. Yet it seems you would have to be able to if judgment were voluntary, and if judgments cause or constitute beliefs.Footnote 27

A second response says that even if judgments are involuntary, they still can be subject to standards of practical rationality like those endorsed by formal decision theories. If so, the performative account might not really require us to decide what judgments we make. Perhaps indirect voluntary influence or some other form of control is enough, or else that judgments can be evaluated as practically rational or irrational regardless of whether we exercise any form of voluntary control over them.Footnote 28

But I think this response is ultimately unsatisfying. Descartes’s own ambition was not just for affirmation of I exist to be evaluated as rational, but to supply for his Meditator and for us a basis on which to affirm our existence. We should be unsatisfied, too, if we want agents to have it in their ability to rationally affirm self-verifying propositions, or to refrain from self-defeating ones. So the performative account needs our reasons for affirmation and refraining to be ones we are capable of acting on.

A third response distinguishes the truth-directed aims assumed by the performative account from other practical aims, such as monetary ones. We might then say one can judge and believe for the former kind of motive, even if not for the latter (Shah & Velleman, 2005). We do not need to settle whether to classify such a view as voluntarist. The important thing is that it allows us to be motivated by alethic aims as the performative account requires, even if not by more crassly prudential ones like a cash prize.

There may be different ways of developing a view like this, but here is one I used to think might work. It takes judgment to be a motivation-individuated instance of some fully voluntary mental act like entertaining.Footnote 29 I can voluntarily entertain that it will rain, for example, by imagining or conceiving of rain, or just by saying ‘It will rain’ in inner speech. When my entertaining is motivated by an alethic aim to entertain the truth, then it is a judgment. But someone might say the same thing in inner speech without this motivation, such as an actor rehearsing her lines, and it would not be a judgment on account of its distinct motivation. If so, then perhaps judgment could be voluntary, and yet necessarily motivated by alethic aims.

But I now doubt this maneuver really succeeds, at least if we hope to salvage the performative account of Moore’s paradox. If entertaining rather than affirming a Moorean conjunction is the act under my control, then the act under my control will not really be self-defeating, since one’s merely entertaining a Moorean conjunction does not guarantee is is false. For comparison, suppose a god rewards those who worship out of piety, but punishes those who worship out of greed. I am sure that I am pious, but really I am greedy for reward. Should I worship? Doing so seems potentially rational, since it is rationalized by my beliefs and motives, and is not obviously self-defeating. Of course, if it were under my control whether to worship greedily, then deciding to worship greedily would be self-defeating. But if what is under my voluntary control is merely whether I worship, and not what motivates the worship, then things are different. Between the options of worshipping piously, worshipping greedily, and refraining, the worst might be worshipping greedily. But between worshipping and refraining, worshipping might be rationally preferable, even if in fact it will be done greedily.

Even setting these difficulties aside, there is a more general problem with any view along these lines. It just does not seem to me that I can believe at will even when my motive is to have true beliefs, any more than I can for a cash prize. This is perhaps most obvious in cases of epistemic tradeoffs, where adopting one belief will guarantee one’s adopting other true beliefs. Suppose Poindexter offers to tutor me in algebra if I believe he is the coolest kid in school. I will get true beliefs about algebra out of it, but I don’t think I could believe for that reason any more than for a monetary one. And the same plausibly goes even for cases of self-verification, where adopting some belief will guarantee the truth of that very belief. Suppose I learn that I have a special telekinetic power to influence a coin toss; if I believe it will land heads, then it will land heads, and if I believe tails, then tails. Without evidence about what I will believe or how the coin will land, I doubt I could simply spontaneously will myself into believing it will land heads.Footnote 30

This matters for the performative account, especially concerning Moore. If one’s options are merely to entertain a Moorean conjunction or not, one’s deciding to entertain will hardly guarantee one believes it. Rather, one’s option must be not just to entertain but to affirm the Moorean conjunction. And this seems unlikely if affirming just is entertaining done with a certain motive. For it would require the motivations for your judgments, and not just the judgments themselves, to be voluntary.

A fourth and I think best response is to say that judgments are voluntary even if beliefs are not. This allows us to let judgments be voluntary, even if beliefs are not. You can affirm to yourself that Poindexter is the coolest kid in school, but that does not mean you really believe it.

To be sure, there may well be distinct phenomena that are well-suited to being called ‘judgments’, and they may not all have the same relationship to beliefs. Psychologists routinely use the term for sub-personal states or events, for example. But even restricting ourselves to elements of our conscious mental life, there seems to be a diversity of phenomena that might well be called ‘judgments’. Here are some examples:

-

affirming I exist in the context of the Meditations

-

reminding oneself that one shouldn’t interrupt

-

recalling from memory that a person’s name is ‘Rene’

-

arriving at the answer to a math problem, but lacking confidence one got it right

-

realizing while closing the front door that one has left one’s keys inside

-

reaffirming that there is no God, having believed it for many years

It is not obvious that these are instances of a single mental phenomenon that should be given a unified account. So it may be better to pitch the performative account as concerned with how certain mental acts that could be called ‘judgments’ are justified. This is the approach I favor. My aim here is merely to characterize this particular mental act, for which Self-Verification and Self-Defeat plausibly hold, including in paradigmatic instances like the cogito and Moorean judgments. We need not insist in advance that all the phenomena listed above are instances of the same kind.

So we can vindicate Self-Verification and Self-Defeat with the right conception of judgments. But it is a conception of judgments (or ‘judgment’) that has them play a less psychologically central role than Descartes and many others might have hoped for. Let epiphenomenalism about judgment be the view that judgments, like assertions, are typically the incidental effects of one’s beliefs rather than their causes. If you aim to speak the truth, you usually will assert a proposition only if you believe you will thereby assert a truth. And aside from special cases like I am referring to 36, that will mean being motivated by a preexisting belief in the asserted proposition. If we conceive of judgments along the same lines, then typically judgments will be the effects of preexisting beliefs as well. You might remark to yourself ‘It looks like it’s going to rain’ while looking out the window, but inner assertions like this will be mere epiphenomena, reflecting a belief you already hold.

Despite the name, epiphenomenalism can allow that judgments sometimes have psychological effects, just as talking to yourself out loud can. It just denies that judgments routinely cause beliefs, or for that matter strictly require them. That way, if you voluntarily affirm that Sydney is the capital of Australia in order to collect a prize, that will not mean you actually believe it. And despite all the comparisons between judgment and assertion, the epiphenomenalist does not need all judgments to take the form of inner speech, or even for all inner speech to be judgments. But the assertion of preexisting beliefs in inner speech is a paradigmatic illustration of the relationship between judgment and belief that the epiphenomenalist claims even for other judgments.

Epiphenomenalism still allows judgment to epistemically guarantee belief, in the sense of providing sufficient evidence of it. But judgments do not metaphysically guarantee beliefs in the sense of metaphysically or causally sufficing for belief. This raises some tricky issues for the performative account of Moore’s paradox, discussed in the appendix. But I think Moorean conjunctions still come out as self-defeating. Even if affirming It will rain, but I don’t believe it will rain does not cause one to believe it, it may still be evidence one already does—and thus epistemically guarantee first conjunct is false.

8 Self-defeat and contagion

Suppose we accept the performative account. What does it matter? In this section and the next, I argue that it undermines a key motivation for prominent views about self-knowledge.

Many authors have drawn broader lessons about self-knowledge from Moore (e.g., Gibbons, 2013; Fernández, 2013; Moran, 2001, pp. 69–77; Shoemaker, 1996; Smithies, 2016, 2019; Zimmerman, 2008), and a few have taken a similar line with Cogito (Burge, 2013, Chs. 1–9; Setiya, 2011). Roughly speaking, these authors think self-verification and self-defeat are in a certain sense contagious; that just as it is wrong to analyze these unusual phenomena in terms of familiar notions like introspection and evidence, it is wrong to analyze self-knowledge more generally in these terms. The anti-evidentialist character of self-verifying and self-defeating judgments infects our ordinary knowledge and judgments about our own minds, so that:

(No Higher-Order Errors) If you believe ϕ, then it is irrational to believe that you do not believe ϕ.Footnote 31

Supposing we accept No Higher-Order Errors, why would that cut against explaining self-knowledge in terms of introspective evidence? There are at least two reasons on offer.

The first comes from Timothy Williamson’s (2000) argument that no nontrivial condition is luminous. If beliefs were luminous, then whenever you believe ϕ, your evidence would include the fact that you do. So your evidence would rule out that you do not believe ϕ, and make it irrational to believe otherwise. But if Williamson is right that beliefs and other mental states are nonluminous, the evidentialist has no obvious way of upholding No Higher-Order Errors. There are bound to be marginal cases where one’s access to one’s believing ϕ is not secure enough to include it in one’s evidence.

A second reason, stemming from Sydney Shoemaker (1996) and others, is more radical, suggesting that at least some introspective accounts of self-knowledge are committed to the possibility of more dramatic introspective failures. Taken at face value, talk of ‘introspective evidence’ suggests the deliverances of something like inner sense, a faculty somehow broadly analogous to our perceptual faculties, but directed inward rather than outward. Yet as Shoemaker emphasizes, it is a matter of contingency which perceptual faculties we have available, and which facts about out outward environment they provide evidence about. An ideally rational agent can suffer perceptual deficits like blindness, and can even be rationally misled about her visible surroundings where a sighted agent would not be. If introspection were akin to an inner sense, then an agent likewise could find himself without it, as in:

Self-Blind George: George believes it will rain based on sufficient meteorological evidence, but he lacks any contingent faculty of introspection that we might be supposed to have. His behavioral evidence misleadingly suggests that he does not believe it will rain.

If self-knowledge depended on some contingent introspective faculty, then George, who lacks this faculty, would not know he believes it will rain. Because of his misleading behavioral evidence, he should believe that he does not believe it, violating No Higher-Order Errors. According to Shoemaker, this amounts to a reductio of any account treating self-knowledge as a kind of quasi-perceptual evidence.

Maybe neither consideration is decisive, but there is at least some pressure for an introspective account of self-knowledge to reject No Higher-Order Errors. And this is where Moore’s paradox spells trouble. For it might seem that No Higher-Order Errors follows from the unaffirmability of Moorean conjunctions, since by Moore it is irrational to affirm the Moorean conjunction It will rain, but I don’t believe it will rain. Since George rationally believes It will rain, it cannot be rational for him to believe I don’t believe it will rain, if we assume:

(Contagion) If it is irrational to affirm Ѱ, and if {ϕ1, ϕ2, … ϕn} jointly entail Ѱ, then it is irrational to jointly believe each of {ϕ1, ϕ2, … ϕn}.

Setting aside Moorean conjunctions, Contagion seems like a natural general principle governing the contagion of irrationality. It in effect combines a multi-premise closure principle with the further claim that it is irrational to believe what it is irrational to affirm. Both claims are contestable, but reasonable enough at a first pass. And applied to Moorean conjunctions, it means it is irrational even for George to believe both conjuncts of a Moorean conjunction. So if George or anyone else believes it will rain, they cannot rationally believe that they do not believe this.

But Moorean conjunctions and other self-defeating propositions give us reason to reject Contagion. The reason has nothing to do with the usual worries about risk accumulation over large numbers of premises, or failures of logical omniscience. It springs directly from the phenomenon of self-defeat. Premises that are not self-defeating can entail conclusions that are, yielding dramatic failures of Contagion. This goes even when a single premise straightforwardly entails a self-defeating conclusion, as in:

Unthinkable Consequences: Robin knows that people sometimes affirm double-negations, propositions of the form not-not-ϕ. But his evidence supports that it is rarer for someone to affirm or even entertain triple-negations, and that hardly anyone ever affirms quadruple-negations. He considers whether he himself will ever affirm a quintuple-negation, and his evidence supports that he never will.Footnote 32

It seems potentially rational for Robin to believe I will not affirm a quintuple-negation. And yet by Self-Defeat, it would be irrational for anyone to affirm I will not not not not not affirm a quintuple-negation. So a single believable premise straightforwardly entails an unaffirmable conclusion.

So while Contagion seems appealing, it sometimes fails dramatically for self-defeating propositions. And the performative account offers an elegant explanation of why. It is a familiar theorem of the probability calculus that if ϕ entails Ѱ, then Pr(ϕ) ≤ Pr(Ѱ). So Contagion would be hard to deny if we accepted Evidential Support. For Evidential Support says that ϕ is affirmable only if supported by my evidence, in which case Ѱ must be affirmable because it is supported to at least the same degree. Things get trickier when the single premise ϕ is replaced by multiple premises, allowing for the accumulation of error risk. But even then, when two conjuncts are each highly probable, the probability of their conjunction must be fairly high.

But the performative account says the affirmability of a proposition does not go with the probability it is true, but instead the probability that it will or would be true if affirmed. And those probabilities do not play by the same rules. For example, where p is that one will affirm a quintuple-negation,

and yet

Since the probabilities in (15) are what matter for affirmability, ~ p can be affirmable even when ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ p is not.

The failure of Contagion is not a quirk of Unthinkable Consequences. It is a predictable upshot whenever premises that are not self-defeating entail a conclusion that is. For if the premises are supported by one’s evidence, they will be affirmable (and believable), but the conclusion they entail will not be. This goes for Moorean conjunctions, too. If one’s evidence supports a high probability of rain, then potentiallyFootnote 33:

Yet the Moorean conjunction still will be unaffirmable, because:

This is plausibly the situation of Stubborn Stella, whose evidence supports rain, but who knows that she (stubbornly) does not believe it will rain. Her evidence supports both conjuncts of the Moorean conjunction It will rain, but I don’t believe it will rain, and also supports for each conjunct that it is true if affirmed. As a consequence, her evidence supports the Moorean conjunction itself, but it does not support that it is true if affirmed. For if she affirms the conjunction, she probably believes the first conjunct, in which case the second conjunct is false.

What about George, our alleged self-blind agent? Unlike Stella, he does believe it will rain. Assuming luminosity, that would mean he must have introspective evidence that he believes this. But without such assumptions, there is no barrier to his rationally believing that he does not believe it will rain. Admitting this belief as rational does not mean admitting George could rationally affirm the Moorean conjunction It will rain, but I don’t believe that it will rain, however, unless we assume Contagion. Without it, the irrationality of affirming Moorean conjunctions does not infect erroneous higher-order beliefs.

9 Self-verification and contagion

The cogito might seem like a paradigm of self-knowledge. Because I exist is self-verifying, I can rationally affirm it, and cannot go wrong when I do. Perhaps that is enough to explain how I know I exist, and by extension how I have other items of self-knowledge like I am a thinking thing, or even I am thinking of 36.

But what about more mundane items of self-knowledge, like I believe it will rain? These are not self-verifying like I exist, so it is not obvious how self-verification could help explain our knowledge of them. The best proposal I know of appeals to what we might call virtuous Moorean conjunctions, like It will rain, and I believe that it will rain.Footnote 34 This virtuous conjunction is not fully self-verifying, since one’s affirming it does not guarantee the truth of its first conjunct. But since affirming it does guarantee the truth of its second conjunct, maybe it is rational to affirm the whole conjunction if one’s evidence supports the first conjunct. More generally, it is plausible that.

(Moore+) If it is rational to believe ϕ, it is rational to affirm ϕ, and I believe that ϕ.

But Moore + does not yet tell us anything about self-knowledge, or even rational self-ascription of belief. To get there, we need the rationality of virtuous Moorean conjunctions to infect self-ascription of belief, for example because:

(Contagion+) If it is rational to affirm ϕ, and ϕ entails Ѱ, then it is rational to believe Ѱ.

Setting virtuous Moorean conjunctions aside, Contagion + might seem a natural general principle governing the contagion of rational affirmation and belief. It in effect combines a single premise closure principle with the further claim that it is rational to believe what it is rational to affirm. And if accepted, that gives us:

(Higher-Order Belief) If you rationally believe ϕ, then it is rational to believe that you believe ϕ.

If you rationally believe ϕ, then by Moore + , it is rational to affirm ϕ and I believe that ϕ. And so by Contagion + it is rational to self-ascribe the belief, like Higher-Order Belief says. Maybe that does not get us all the way to self-knowledge, but it is at least pretty close.

Even so, it is not clear Higher-Order Belief really sets the stage for a satisfying general account of self-knowledge. To explain our self-knowledge, we need an explanation of how we in fact rationally self-ascribe beliefs, not just how we are in principle in a position to. Given that we rarely make virtuous Moorean affirmations, an account drawing on them threatens an implausibly dramatic separation between the justification of our higher-order beliefs and the actual psychological mechanisms generating them.Footnote 35

But in any case, I think the argument for Higher-Order Belief does not succeed, because Contagion + is false. The problem is again that self-verification gives rise to dramatic closure failures, as in:

Unthinkable Consequences: Robin knows that he sometimes affirms conjunctions, and that some of these conjunctions have conjuncts that are logically complex. But Robin has strong inductive evidence that he will never affirm a conjunction one of whose conjuncts is a sextuple-negation, a proposition of the form not-not-not-not-not-not-ϕ. At the same time, his evidence supports that it will rain.

Is it rational for Robin to believe I will affirm a conjunction one of whose conjuncts is a sextuple-negation? Arguably not, since his evidence supports it is false regardless of whether he believes or affirms it. But it is rational for Robin to affirm It will not not not not not not rain, and I will affirm a conjunction one of whose conjuncts is a sextuple-negation. For if he affirms it, it is guaranteed to be true. So its being rational to affirm this partially self-verifying proposition does not make it rational to believe (or affirm) its second conjunct. Thus Contagion + fails, and with it the argument for Higher-Order Belief. For it does not follow from the affirmability of It will rain, and I believe it will rain that it is rational to believe (or affirm) I believe it will rain on its own.

The performative account again predicts this. Ordinarily a proposition is affirmable only if one’s evidence supports it, in which case one’s evidence will support every proposition it entails. But partially self-verifying propositions can be affirmable even if one’s evidence does not support them. And so they may be affirmable even if they entail other unsupported propositions which are not at all self-verifying. Let q be that one affirms a conjunction one of whose conjuncts is a sextuple-negation. If one’s evidence supports that it will rain, then:

And yet:

Likewise for the quasi-Moorean It will rain, and I believe it will rain, it is possible that

even while

Maybe this is George’s situation when his evidence supports rain, for example. In supporting that it will rain, his evidence also supports that It will rain, and I believe it will rain is likely true if he affirms it. But his evidence still does not support I believe it will rain is true, even if he affirms or believes it.

10 Conclusions

The performative account grounds Self-Verification and Self-Defeat in general and independently motivated theories of rational decision. It thus gives a parsimonious explanation of the rationality of cogito-like judgments and the irrationality of Moorean ones, in terms of rational norms governing ordinary acts like assertions. But this comes at the expense of claiming a broader theoretical relevance for these phenomena. Making judgments out to be like inner assertions means that like assertions they do not typically cause beliefs; instead they are cast in the role of epiphenomena typically reflecting the beliefs one already holds. And by avoiding evidential standards for judgment in favor of practical ones vindicating Self-Verification and Self-Defeat, the performative account undermines otherwise appealing principles governing the contagion of rationality or irrationality between judgments and beliefs—blocking broader implications for the nature of self-knowledge. Maybe these consequences of the performative account are a letdown, but I think that is no reason to reject it. There was never any guarantee in advance that affirming I exist like Descartes’s Meditator, or knowing better than to affirm It will rain, but I don’t believe it will rain, has much meaningful connection to how we know about ourselves and our own beliefs.Footnote 36

Notes

Suppose Al affirms I exist, Betty affirms I exist, and Charlie affirms Al exists. Throughout the paper, I assume for convenience that Al and Betty are the ones who affirm the same proposition. But most everything I say could be adapted to other views about what unites Al’s and Betty’s judgments.

Cf. Burge (2013, p. 69), and the authors discussed below.

Both strands also seem apparent in Augustine’s City of God XI, 26.

See Paul (2018) for a discussion of Descartes on introspection. I use ‘introspection’ to mean receptive knowledge of particular mental states, including involuntary states like sensory perceptions.

See also the more ambiguous recapitulation in the Fourth Meditation (CSM II 41).

See also CSM II 409–410.

See Hintikka (1962) for an attempt to distance the slogan from the introspective account.

Cf. Paul (2020).

The French text adds “or thought anything at all.”

Cf. “So serious are the doubts into which I have been thrown as a result of yesterday’s meditation…” (CSM II 16). These are dialectical remarks, not substantive premises.

Cf. Augustine’s City of God XI, 26: “For if I am deceived, I am. For he who is not, cannot be deceived; and if I am deceived, by this same token I am. And since I am if I am deceived, how am I deceived in believing that I am? For it is certain that I am if I am deceived. Since, therefore, I, the person deceived, should be, even if I were deceived, certainly I am not deceived in this knowledge that I am.”

E.g., CSM I 127 and 183–184, and especially CSM II 409–410 and 415–417—though I think some parts of the latter source plainly favor an introspective reading.

The introspective account is also opposed by the method of doubt reading advanced by Broughton (2002 Ch. 7) and Curley (1978, Ch. 4). This reading breaks with a performative one, however, in holding that the truth of I exist is guaranteed directly by skeptical the hypotheses themselves. The idea is that affirming I exist is rational because any grounds for doubting it must invoke skeptical hypotheses that presuppose one’s existence—whether one affirms it or not. While I agree this reading fits some of Descartes’s writings, especially the unfinished Search for Truth, it fits the Meditations less well. For in the central Second Meditation passage, Conception Guarantee is still the advertised ultimate conclusion. Even when Deception Guarantee is considered, the Meditator emphasizes that a deceiver “will never bring it about that I am nothing so long as I think that I am something.” And a Third Meditation recapitulation of Deception Guarantee again says “let whoever can do so deceive me, he will never bring it about that I am nothing, so long as I continue to think I am something” (CSM II 25). So even when skeptical hypotheses are raised the emphasis remains on the guaranteed truth of I exist if one affirms it, with the skeptical hypotheses reinforcing the strength of the guarantee.

Perhaps it could be claimed that there is simply a primitively rational transition from knowledge that a proposition is self-verifying to judgment that it is true. But without a more general explanation of why these transitions are rational, this proposal is liable to seem ad hoc. Pryor n. d. responds to an explanation that he attributes to Ralph Wedgwood, and Barnett 2016 discusses a related view.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pressing me on this.

When the Meditator say I exist is true not only when conceived in his mind but when “put forward [profero],” he probably means to refer to both conceiving and uttering in speech.

Cf. Hintikka (1962, pp. 18–19).

See also Greaves 2013, who discusses phenomena akin to self-verification and self-defeat as test cases for competing epistemic decision theories. Unlike Greaves, I want to emphasize what these theories have in common, just by virtue of being theories of decision rather than evidential support.

One could replace an alethic value function with an epistemic value function, which evaluates judgments not just by their truth, but by their status as knowledge. This modification might be necessary to accommodate the alleged fact that one should not judge that one’s lottery ticket will lose. But unlike Clayton Littlejohn (2010) and Timothy Williamson (2000, Ch. 11), I think it is an idle wheel in the explanation of Moore’s paradox.

Thanks again to an anonymous referee for pressing the issue.

If instead belief were a necessary prerequisite for judgment, like activity in the motor cortex is a prerequisite for bodily action, then perhaps judgments could be voluntary without beliefs being voluntary. But regardless of the direction of causation, if you could judge to collect a prize, you still would have to believe. Thanks to a referee for raising the issue.

Cf. Shah and Velleman (2005, pp. 504–505), whose terminology differs from mine (esp. ‘affirm’).

Cf. Velleman (1989).

Thanks to Ralph Wedgwood for discussion of related examples.

Note that \(\Pr \left( { \sim B\left( r \right)|r} \right)\) need not be low, as can be seen when one’s evidence does not support r. See Barnett 2016 for discussion.

The proposal is loosely adapted from remarks from Tyler Burge (2013, pp. 67–70), though his ultimate view seems to me to land some distance from its inspiration in the cogito. (For discussion, see Barnett n. d.) So compared to Moore’s paradox, where broader lessons for self-knowledge are widely alleged, my discussion of the cogito will be more exploratory.

For comments and/or discussion, I am grateful to Brian Cutter, Imogen Dickie, J. Dmitri Gallow, David Hunter, Harvey Lederman, Eric Marcus, Elliot Paul, Gurpreet Rattan, Timothy Rosenkoetter, Miriam Schoenfield, Declan Smithies, Brian Weatherson, Ralph Wedgwood, Alex Worsnip, three anonymous referees, and audiences at New York University, Toronto Metropolitan University, and the Northern New England Philosophical Association.

See also Greaves’s (2013) Promotion and Arrogance examples.

Note that under GR, there is no guarantee that \(\Pr \left( {T||J\left( \phi \right)} \right) \ne \Pr \left( \phi \right)\;{\text{if}}\;\Pr \left( {F||J\left( \phi \right)} \right) \ne \Pr \left( { \sim \phi } \right)\). So (4) also can be satisfied if \(\Pr \left( {J\left( \phi \right) \Rightarrow F|J\left( \phi \right)} \right) + \Pr \left( {J\left( \phi \right) \Rightarrow F| \sim J\left( \phi \right)} \right) \ne \Pr \left( { \sim \phi } \right)\)

References

Ayer, A. J. (1953). Cogito, ergo sum. Analysis, 14(2), 27–31.

Barnett, D. J. (2016). Inferential justification and the transparency of belief. Noûs, 50(1), 184–212.

Barnett, D. J. (2022). Graded ratifiability. Journal of Philosophy, 119(2), 57–88.

Barnett, D. J. (n. d.) Reflection deflated. Available at https://www.davidjamesbar.net

Briggs, R. (2009). Distorted reflection. Philosophical Review, 118(1), 59–85.

Broughton, J. (2002). Descartes’s method of doubt. Princeton University Press.

Burge, T. (2013). Cognition through understanding: Philosophical essays (Vol. 3). Oxford University Press.

Chan, T. (2010). Moore’s paradox is not just another pragmatic paradox. Synthese, 173(3), 211–229.

Christensen, D. (2010). Higher-order evidence. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 81(1), 185–215.

Christofidou, A. (2013). Self, reason, and freedom: A new light on Descartes’ metaphysics. Routledge.

Conee, E. (1987). Evident, but rationally unacceptable. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 65, 316–326.

Curley, E. M. (1978). Descartes against the skeptics. Harvard University Press.

de Almeida, C. (2001). What Moore’s paradox is about. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 62(1), 33–58.

de Almeida, C. (2007). Moorean absurdity: An epistemological analysis. In M. Green & J. Williams (Eds.), Moore’s paradox: New essays on belief, rationality, and the first-person. Oxford University Press.

Egan, A. (2007). Some counterexamples to causal decision theory. Philosophical Review, 116(1): 93–114.

Feldman, F. (1973). On the performatory interpretation of the cogito. Philosophical Review, 82(3), 345–363.

Feldman, R. (2000). The ethics of belief. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 60(3), 667–695.

Fernández, J. (2005). Self-knowledge, rationality, and Moore’s paradox. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 71(3), 533–556.

Fernández, J. (2013). Transparent minds. Oxford University Press.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1966). Descartes’s discussion of his existence in the second meditation. Philosophical Review, 75(3), 329–356.

Frankfurt, H. G. (1970). Demons, dreamers, and madmen: the defense of reason in Descartes’s meditations, reprinted 2008. Princeton University Press.

Gallow, D. (2020). The causal decision theorists guide to managing the news. Journal of Philosophy, 117(3), 117–149.

Gibbons, J. (2013). The norm of belief. Oxford University Press.

Greaves, H. (2013). Epistemic decision theory. Mind, 122 (488): 915–952.

Green, M., & Williams, J. (2007). Introduction. In Moore’s Paradox: New Essays on Belief, Rationality, and the First-Person, Mitchell Green and John Williams, eds. Oxford: OUP.

Green, M., & Williams, J. (2011). Moore’s paradox, truth and accuracy. Acta Analytica, 26(3), 243–255.

Hájek, A. (2007). My philosophical position says p and I don’t believe p. In M. Green & J. Williams (Eds.), Moore’s paradox: New essays on belief, rationality, and the first-person. Oxford University Press.

Heal, J. (1994). Moore’s paradox: A Wittgentsteinian approach. Mind, 103(409), 5–24.

Hieronymi, P. (2006). Controlling attitudes. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 87(1), 45–74.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Cogito, ergo sum: Inference or performance? Philosophical Review, 71(1), 3–32.

Kelly, T. (2002). The rationality of belief and some other propositional attitudes. Philosophical Studies, 110(2), 163–196.

Kenny, A. (1968). Descartes: A study of his philosophy. Random House.

Kriegel, U. (2004). Moore’s paradox and the structure of conscious belief. Erkenntnis, 61, 99–121.

Littlejohn, C. (2010). Moore’s paradox and epistemic norms. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 88(1), 79–100.

Longuenesse, B. (2017). I, me, mine: back to Kant, and back again. OUP.

Markie, P. (1992). The cogito and its importance. In J. Cottingham (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to Descartes. Cambridge University Press.

Moran, R. (2001). Authority and estrangement: An essay on self-knowledge. Princeton University Press.

Paul, E. S. (2018). Descartes’s anti-transparency and the need for radical doubt. Ergo, 5, 1083–1129.

Paul, E. S. (2020). Cartesian clarity. Philosophical Imprint, 20(19), 1–28.

Peacocke, A. (2017). Embedded mental action in self-attribution of belief. Philosophical Studies, 174, 353–377.

Peacocke, C. (2012). Descartes defended. Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 86(1), 109–125.

Podgorski, A. (2022). Tournament decision theory. Noûs, 56(1), 176–203.

Pryor, J. (n. d.) More on hyper-reliability and apriority. Available at: https://www.jimpryor.net/

Rinard, S. (2017). No exception for belief. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 94(1), 121–143.

Rinard, S. (2019). Equal treatment for belief. Philosophical Studies, 176(7), 1923–1950.

Salow, B. (2019). Elusive Externalism. Mind, 128(510), 397–427.

Setiya, K. (2011). Knowledge of intention. In A. Ford, J. Hornsby, & F. Stoutland (Eds.), Essays on Anscombe’s intention. Harvard University Press.

Shah, N., & Velleman, J. D. (2005). Doxastic deliberation. Philosophical Review, 114(4), 497–534.

Shoemaker, S. (1996). The first-person perspective and other essays. Cambridge University Press.

Silins, N. (2012). Judgment as a guide to belief. In D. Smithies & D. Stoljar (Eds.), Introspection and consciousness. Oxford University Press.

Silins, N. (2013). Introspection and inference. Philosophical Studies, 163(2), 291–315.

Smithies, D. (2012). Moore’s paradox and the accessibility of justification. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 85(2), 273–300.

Smithies, D. (2016). Belief and self-knowledge: lessons from Moore’s paradox. Philosophical Issues, 26(1), 393–421.

Smithies, D. (2019). The epistemic role of consciousness. Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. (1988). Blindspots. Oxford University Press.

Velleman, J. D. (1989). Epistemic freedom. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 70, 73–97.

Weatherson, B. (2008). Deontology and Descartes’s demon. Journal of Philosophy, 105(9), 540–569.

Wedgwood, R. (2013). Gandalf’s solution to the Newcomb problem. Synthese, 14, 1–33.

Wedgwood, R. (2017). The value of rationality. Oxford University Press.