Abstract

I argue that high level causal relationships are often more fundamental than low level causal relationships. My argument is based on some general principles governing when one causal relationship will metaphysically ground another—a phenomenon I term derivative causation. These principles are in turn based partly on our intuitive judgments concerning derivative causation in a series of representative examples, and partly on some powerful theoretical considerations in their favour. I show how these principles entail that low level causation can derive from high level causation, and in particular that neural causation can derive from mental causation. I then draw out several important consequences of this result. Most immediate among these are the implications the result has for aspirations to reduce high level causation to its low level counterpart. But the result also bears on the possibility of downward causation, the relationship between counterfactuals and causation, and the idea—familiar from both the literature on the exclusion problem and the literature on proportionality constraints on causation—that causal relationships at different levels compete for their existence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This is a paper about the connection between causal relationships at different levels of reality. Questions about this connection have received enormous amounts of philosophical attention. Is there causation at different levels? If so, which levels does it occupy? Is there causation at the level of fundamental physics? If we weren’t to find it at the fundamental physical level, would it exist at all? Can we make sense of causation at high levels? Do causes at different levels compete with one another? Does causation at some levels reduce to causation at others?

I hope to shed light on some of these issues by arguing for the following claim: the level of reality occupied by a causal relationship does not always match up with how fundamental that causal relationship is. In particular, I argue that high level causal relationships are often more fundamental than their lower level counterparts, in the sense that high level causal relationships often metaphysically ground their lower level counterparts. Cases of mental causation fit this bill. My feeling thirsty caused me to drink—a high level causal relationship—and likewise the neural event underlying my feeling thirsty (call it n) caused me to drink—a lower level causal relationship. On the view I defend in this paper, n’s causing me to drink is grounded in my thirst’s causing me to drink.Footnote 1 Causation involving more fundamental events is not always itself more fundamental—indeed, sometimes it is less fundamental.

The view defended in this paper is not, to my knowledge, a view that has been defended—or even considered—in the contemporary literature. Existing views on the relationship between high level and lower level causation in general, and mental causation and physical causation in particular, split into five categories.

Epiphenomenalists deny that there is any high level causation: they maintain that high level events never cause anything (Lyons, 2006; Tammalleo, 2008 defend epiphenomenalism, and on one natural interpretation of their view, so do Jackson & Pettit, 1988, 1990). According to them, our example of mental causation is impossible: while n may well have caused me to drink, the mental event of my feeling thirsty did not. Mental events are not suited to causing anything.

Gappists deny that every event with a high level cause has lower level causes. On their view, there are gaps in the physical causal order—not every caused event has a low level physical cause. Gappists are liable to deny that the neural event, n, caused me to drink, but are happy to admit that my thirst caused me to drink.Footnote 2

Identitarians say that the relationship between high level and lower level causation is that of identity: every instance of high level causation is identical to an instance of lower level causation. Since n is identical to my feeling thirsty, their respective causings of my drinking are also identical.Footnote 3

Independentists maintain that high level causation is independent of lower level causation. That is, they deny that my thirst’s causing me to drink depends on n’s causing me to drink, and that n’s causing me to drink depends on my thirst’s causing me to drink.Footnote 4

Finally, dependentists typically maintain that high level causation depends on lower level causation, and thus claim that my thirst’s causing me to drink depends on n’s causing me to drink, but not that n’s causing me to drink depends on my thirst’s causing me to drink.Footnote 5

I am a dependentist of a different stripe: I claim that lower level causation sometimes depends on higher level causation. As the rationale I offer for my view will eventually reveal, however, the dependence relationships between high and low level causation are far from uniform: in different cases the dependence goes in different directions. Still, in our example of mental causation the verdict of my brand of dependentism is clear: n’s causing me to drink depends on my thirst’s causing me to drink.

My argument for the central thesis of this paper—that my favoured stripe of dependentism is true—is based on some general principles governing what I call derivative causation. By definition, one causal relationship, f caused g, derives from another, p caused q, just in case p caused q, metaphysically grounds, f caused g.

The principles I plump for specify sufficient conditions for one causal relationship to derive from another—i.e., for one causal relationship to ground another. I do not seek necessary conditions for derivative causation, and toward the end of the paper I give examples of derivative causation not covered by my favoured principles. Another feature of the principles I am interested in is that they are neutral on the question of what causal relationships actually obtain: they tell us whether one causal relationship derives from another only given those preestablished causal relationships as input—they do not take more fundamental relationships as input and spit out other, less fundamental relationships.

Unlike the principles appealed to in so much of the existing work on causation and levels (e.g., Kim’s exclusion principle (1998, 2005), and Kroedel and Schulz’s causal grounding principle (2016)], the principles I work with are motivated not only by general metaphysical considerations but by our intuitive judgments about concrete examples. In particular, my principles are closely tied to data generated by our intuitive judgments concerning sentences of the form ‘f caused g because p caused q’ in a class of cases that are prima facie neutral with respect to the questions at issue in the aforementioned literature. I identify a pattern underlying such judgments which characterises a class of structures that we have powerful theoretical reason to believe will, in general, result in derivative causation. If these structures do indeed generate derivative causation in the way I suggest, it follows immediately that lower level causation often derives from high level causation.

Aside from being surprising in its own right, this result has implications for a number of debates about the connection between high and lower level causation. In this paper I can only briefly discuss a couple of these implications. One is that the result places constraints on the way in which high level causation can be reduced to lower level causation.Footnote 6 Another is the result’s suggestion that causal relationships at different levels do not in general compete for their existence in the way suggested by e.g. Kim (1998, 2005)—who thinks that low level causation threatens to exclude high level causation—and Yablo (1992)—who thinks that proportional causation threatens to exclude disproportionate causation. And another is that the result rules out certain kinds of downward causation, a consequence of which is that counterfactual dependence does not suffice for causation—a thesis endorsed by nearly every partisan of a broadly counterfactual approach to causation (Hall, 2004; Paul & Hall, 2013).

2 Preliminaries

A standard way of talking about causation and levels (which I will adopt throughout this paper) has it that whether a causal relationship is low level or high level is entirely a function of the level of the event occupying the cause role in the relationship, without reference to the level of the event that occupies the effect role. Let events whose occurrence is not metaphysically grounded in the occurrence of any other event be low level events, and all other events be high level events. Then causal relationships whose constituent causes are low level will themselves be low level, and causal relationships whose constituent causes are high level will themselves be high level. The causal relationship which holds between my thirst and my drinking is thus an instance of high level causation, and causal relationships that hold between any of the fundamental physical events underlying my thirst and my drinking are instances of low level causation.Footnote 7 We can also define a notion of one causal relationship being at a higher/lower level than another. I say that the causal relationship between f and g is higher level than the causal relationship between p and q (and the causal relationship between p and q lower level than the causal relationship between f and g) just in case both f and g are at least as high level as p and q and at least one of f and g is strictly higher level than at least one of p and q (where f, g, p and q range over events).

I will frequently discuss the connection between high and lower level causal relationships. In doing so I am discussing the connection between two relationships, the first of which involves a high level cause and the second of which involves a cause and effect each of which is at least as low level as the cause and effect in the high level relationship, and at least one of which is strictly lower level than the events in the high level relationship. Less frequently, I will discuss the connection between low and higher level causal relationships. In doing so I am discussing the connection between two relationships, the first of which involves a low level cause and the second of which involves a cause and effect each of which is at least as high level as the cause and effect in the low level relationship, and at least one of which is strictly higher level than the events in the low level relationship. It is compatible with this that the higher level relationship in this pair is still low level due to its constituent cause being low level, while its constituent effect is at a higher level than the effect of the other relationship in the pair. For a similar reason, it can also be that the lower level relationship in a pair is still high level. Moreover, it can be that a high level relationship is not higher level than a low level relationship. This might sound strange, but that doesn’t matter—it is just a way of talking that will be convenient for the purposes of this paper. Nothing of substance turns on it.

A question of great interest to metaphysicians, philosophers of science and philosophers of mind alike has been whether there is any high level causation, so understood, and, if so, how exactly it is related to lower level causation. Of course, such philosophers are not interested in the relationship between high and lower level causation in general. There won’t be any interesting relationship between one atomic collision causing another in Andromeda and the United Kingdom’s declaration of war on Nazi Germany causing the Battle of Britain, despite the former being a lower level causal relationship than the latter. Thus, with a few exceptions, I restrict myself to investigating the connections between high and lower level causal relationships some of whose constituent events are grounding related.Footnote 8 I will usually be interested in pairs comprising a high level causal relationship f caused g and a lower level causal relationship p caused q for which the following is trueFootnote 9: either (i) p grounds f and q grounds g, or (ii) p grounds f and q = g, or (iii) p = f and q grounds g.Footnote 10 The main example of such a pair that I will focus on has already been introduced. My feeling thirsty caused me to drink—a high level causal relationship —and likewise the neural event underlying my feeling thirsty (call it n) caused me to drink—a lower level causal relationship.Footnote 11 This pair satisfies clause (ii) of the above condition. Unless I say otherwise, when I speak of pairs of causal relationships, one of which is high level and the other of which is lower level, I have in mind pairs that satisfy the above condition.

The structure of the paper is as follows. I start by introducing the phenomenon of derivative causation using a series of examples. Then I propose some principles about derivative causation based on the conspicuous pattern exhibited by these examples, but show that the most flat-footed version of these principles is not sensitive to the way in which causal influence can be conveyed along multiple paths. I proceed to show that, appropriately qualified, these principles entail the central thesis of this paper: that lower level causal relationships sometimes derive from high level causal relationships. From here I proceed to tease out several of the thesis’ more interesting consequences (which I listed earlier) for the connection between high and lower level causation.

3 Derivative causation

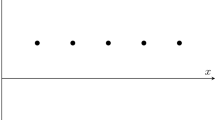

As the views briefly canvassed in the opening section of this paper suggest, the nature of the relationship between higher and lower level causation is highly controversial. For this reason, we will kickstart our search for principles governing derivative causation with some relatively anodyne causal structures which focus on causal relationships that are intuitively at the same level of reality. To that end, take a causal relationship f caused g. Suppose that for some p it is true that f caused p and p caused g. In cases with this structure, which is represented in Fig. 1 (where dashed arrows represent causal relationships and big block arrows represent grounding relationships between causal relationships), we are usually inclined to say that f caused g because f caused p, and that f caused g because p caused g. We all know, for instance, that the jury’s verdict caused Socrates to drink hemlock, and Socrates’ drinking hemlock caused his death. Here we say that the jury’s verdict caused Socrates’ death because it caused him to drink hemlock, and because his drinking hemlock caused his death.

It is reasonable to suppose that these because claims indicate grounding relationships. We could, for instance, felicitously replace them with in virtue of claims, which are one of the signatures of grounding. But more to the point, a popular way to think of grounding is as a building relation (Bennett, 2017), and on a natural way of understanding cases like the one above, they involve the building of a more encompassing causal relationship from two less encompassing causal relationships. In particular, the relationship between the jury’s verdict and Socrates’ death is constructed by chaining together the more immediate relationships between the verdict and his drinking hemlock, and between his drinking hemlock and his death. When a causal relationship is built from the chaining together of two other causal relationships, we have an instance of derivative causation.Footnote 12 Schematically: supposing that f caused g, if f caused p and p caused g, then f caused g is grounded in f caused p and in p caused g. Similar reasoning suggests that, on the supposition that f caused g, if f caused p, p caused q, and q caused g, then f caused g is grounded in f caused p, in p caused q, and in q caused g. This structure is represented in Fig. 2.

Though this sort of chaining is familiar from the idea that causation is transitive (an idea I will return to in Sect. 4), the fact that it results in derivative causation has not, to my knowledge, been remarked on in the literature. This is an unfortunate oversight, it turns out. Once one notices the connection between chaining and derivative causation in cases like the one above, it is easy to see that something similar is going on in the cases that have previously been alleged to exhibit derivative causation in the literature.Footnote 13

The body of literature which explicitly engages in general theorising about derivative causation is small. Goldman (1970), Kim (1974, 2005) and Menzies (1988) are some of the few examples, and out of the sorts of cases I am concerned with, they mostly focus on those that share a common structure with the following example, due to Kim (1974).

When Socrates drank hemlock, not only did he die, but his wife, Xanthippe, became a widow. His death, however, did not cause Xanthippe to become a widow. Rather, Socrates’ death grounds Xanthippe’s becoming a widow—the latter event occurs partly in virtue of the occurrence of the former. Despite this difference, the same phenomenon arises in this case. For Socrates’ drinking hemlock caused not only his death, but Xanthippe’s widowing. Moreover, his drinking hemlock caused Xanthippe to become a widow because his drinking hemlock caused him to die.

What seems to be going on here is that a causal relationship is being chained not with another causal relationship, but with a grounding relationship, so as to construct a more encompassing causal relationship. As in cases involving the chaining of causal relationships, it seems that cases involving mixed chains of causation and ground exhibit derivative causation. But while it is intuitively obvious that this will hold generally in the purely causal case, it is less obvious that the same is true of the less familiar mixed case. To help assuage this doubt, I now present several examples (the first of which is adapted from Goldman [1970]) of mixed structures which intuitively exhibit derivative causation. (Rather than spelling out the examples in detail, however, I simply list the because claims that indicate the relevant instances of derivative causation, from which detailed examples can be easily reconstructed.)

My opponent’s anxiously eyeing the b6 square caused me to checkmate him because it caused me to move my knight to b6.

The criminal’s anger caused him to violate his probation because it caused him to assault a friend.

The magnesium’s burning caused its weight to increase because it caused its mass to increase.

In each of these cases, the effect in the derivative relationship is grounded in the effect of the relationship from which it derives. It thus seems that derivative causal relationships can be built not only from chains of causal relationships, but from mixed chains whose first link is a causal relationship and whose second link is a grounding relationship. Schematically: supposing that f caused g, if f caused p and p grounds g, then f caused g is grounded in f caused p. Combining the purely causal case with this mixed case suggests that, on the supposition that f caused g, if f caused p, p caused q, and q grounds g, then f caused g is grounded in f caused p and in p caused q. These structures are represented in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively (where small block arrows represent grounding relationships between events).

Having identified chaining as a feature common to both varieties of derivative causation discussed so far, it is only natural to conjecture that there exists a third variety which arises in another sort of chaining structure. It is this third variety that is key to understanding how high level causation can be more fundamental than lower level causation. The sort of structures that give rise to it involve a causal relationship that is built from a chain whose first link is a grounding relationship and whose second link is a causal relationship. Our earlier example of mental causation instantiates this structure, but is too controversial a case to use as intuitive motivation for countenancing derivative causation of this sort. Let us start with a more neutral one.

Suppose Xanthippe hated Socrates so much that she wished a painful death upon him. However, she did not want to be in the precarious position of a widow in ancient Greece. So, when Socrates died, this caused her great anguish.

The last claim I make in my description of the case might come as a surprise given the first claim I made. Didn’t Xanthippe hate Socrates? If so, why would his death cause her anguish? It turns out that attention to the derivative causal structure of the case helps to reconcile these two facts. For Socrates’ death did cause Xanthippe great anguish, but did so because it made her a widow, and because her becoming a widow caused her great anguish.Footnote 14 Cases like this motivate the following schematic principle: supposing that f caused g, if f grounds p and p caused g, then f caused g is grounded in p caused g. Similar reasoning suggests that on the supposition that f caused g, if f grounds p, p caused q, and q caused g, then f caused g is grounded in p caused q and in q caused g. These structures are represented in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively.

This third kind of derivative causation is less familiar than the first two. The first is at least implicit in many discussions pertaining to the transitivity of causation, and the second has been explicitly discussed at least several times. This third kind, however, has, to my knowledge, received no attention at all in the literature. But once noticed, it crops up everywhere. Martha Stewart’s sale of certain stocks caused her to go to jail in part because she broke the law in virtue of selling those stocks, and in part because her breaking the law in turn caused her to go to jail. The horologist’s reduction of the length of the pendulum inside a grandfather clock caused the clock to run fast in part because in virtue of reducing the pendulum’s length he reduced its period, and in part because his reducing the pendulum’s period caused the clock to run fast.

Combining this third kind of structure with the second kind of structure we considered yields yet another principle about derivative causation: supposing that f caused g, if f grounds p, p caused q, and q grounds g, then f caused g is grounded in p caused q. This structure is depicted in Fig. 7. Combining all three kinds of structure yields the final principle about derivative causation I will mention: supposing that f caused g, if f grounds p, p caused q, q caused r, and r grounds g, then f caused g is grounded in p caused q and in q caused r. This structure is depicted in Fig. 8.

4 Principles for derivative causation

In summary, the argument of the preceding section went like this. In cases where f caused p, p caused g, and f caused g, we are inclined to judge that f caused g because f caused p and because p caused g. It is most natural to interpret these because claims as disclosing grounding relationships, as in such cases the relationship f caused g seems to be constructed out of the relationships on which it depends: f caused p and p caused g. Interestingly, we are inclined to make analogous judgments in cases wherein we chain together not two causal relationships, but one causal relationship and one grounding relationship. Given the close analogy between causation and grounding, it seems best to subsume these cases to the same pattern: more encompassing causal relationships are being constructed from less encompassing determination relationships, where determination is the genus of which causation and grounding are the only species.Footnote 15 And because this picture on which chains (i.e. the more encompassing causal relationships) are grounded in the links from which they are built (i.e. the less encompassing causal relationships) is so theoretically compelling, in endorsing the structural principles of the preceding section we are not just fitting a curve to a small set of intuitively compelling data points. Rather, the curve is one which, on reflection, we are strongly inclined to draw anyway.

A pithy way of painting the above picture is: derivation results from mediation. The jury’s causing of Socrates’ death was mediated by the jury’s causing him to drink hemlock. The hemlock’s causing of Xanthippe’s widowing was mediated by its causing of Socrates’ death. And his drinking hemlock’s causing of Xanthippe’s anguish was mediated by her becoming a widow’s causing of her anguish. Less pithily, the principles about derivative causation we have arrived at are the following.

- Mediation::

-

f caused g derives from p caused q if

-

(i)

f caused g and p caused q, and

-

(ii)

-

(a)

f = p and q determines g, or

-

(b)

g = q and f determines p, or

-

(c)

f determines p and q determines g.

-

(a)

-

(i)

The principles enshrined in Mediation are able to correctly identify derivative causation in examples instantiating every structure we’ve considered so far, and they embody the theoretically attractive idea that when determination relationships are ‘linked together’ in the right way they ‘compose’ or ‘add up’, yielding more encompassing determination relationships.

As already noted, this idea is related to the more familiar idea that causation and ground are transitive relations (Lewis, 1973; Fine, 2012a, b; Paul & Hall, 2013). But the ideas are not the same, even if we extend the transitivity thesis beyond causation and ground taken separately to determination more generally.Footnote 16 In fact, one of the fruits of the idea that determination relationships compose is that it can help to explain the transitivity of determination: the reason that, say, every cause f of an event p will share all of p’s effects, g, is that the causal relationships between f and p, and p and g, chain together to build a more encompassing causal relationship between f and g.

So, if determination is transitive, the hypothesis that determination relationships add up is explanatorily fruitful. But what if, as many have come to think, determination is not transitive (e.g., Hitchcock, 2001, and Schaffer, 2012)? Are we then left without any reason to think that determination relationships add up in anything like way posited by Mediation? I think not. Indeed, the bulk of this paper thus far has consisted in the presentation of a central reason for thinking determination relationships compose: we have firm intuitions in concrete cases which indicate that determination relationships do indeed compose. Not all concrete cases, mind you. Cases where transitivity seems to fail are precisely the cases in which any intuition that the relevant determination relationships add up is absent. But why should our judgement that determination relationships fail to add up in these cases force us to revisit our judgement that determination relationships succeed in adding up in all manner of other cases? The first sort of judgement lacks any clear relevance to the second.

We can further bring out the irrelevance by adopting a toy theory of causation that does not satisfy transitivity. To that end, suppose we think that causation is just counterfactual dependence of the right sort between appropriately distinct events. Then we will reject transitivity for the obvious reason that counterfactual dependence is intransitive. But after attending to enough concrete cases we will likely accept that causal relationships do add up in the right circumstances, though circumstances are not always right. This is because the counterfactual dependences we take causation to consist in themselves seem to add up. Socrates’ death, for instance, counterfactually depends on the jury’s verdict. Why? Presumably it is in part because if the jury hadn’t convicted him then he wouldn’t have drunk hemlock, and in part because if he hadn’t drunk hemlock he wouldn’t have died. And, given our toy theory of causation, the truth of this claim discloses two instances of derivative causation wherein causal relationships add up in the relevant sense.Footnote 17

Another reason to countenance the summing of determination relationships irrespective of whether determination is transitive is again a reason we have already encountered. How are we to explain how Socrates’ death caused Xanthippe’s anguish in spite of her hatred of him unless we can appeal to the facts that his death made her a widow and her widowing caused her anguish? The way we make this appeal is telling, as we are wont to say that Socrates’ death caused Xanthippe’s anguish because it made her a widow, and because her widowing caused her to become anguished. This explanatory appeal requires derivative causation, as it requires that there is a causal relationship between Socrates’ death and Xanthippe’s anguish in virtue of these two other determination relationships, one of which is causal.

Yet another reason to suppose that determination relationships compose is that composition allows us to explain how causation can span spatiotemporal gaps. Imagine that a long row of dominoes is spaced at intervals and that the fall of the first domino eventually causes the last domino to fall. A natural and compelling response to the question of how the fall of the first domino caused the fall of the last domino given the spatiotemporal gap between the two events is that the fall of the first domino did it by causing intermediate falling events which themselves were causally related to the final event, but more proximately. These intermediate causal relationships help to bridge the gap between the first and the final fallings by chaining together to build a more encompassing causal relationship. More generally, we might hope that derivative causation can offer us an account of mediated causation, where by ‘mediated causation’ I mean instances of the following schema: f caused g by making p happen (where f makes g happen just in case f determines g). The idea being that for f to cause g by making p happen just is for f caused g to be grounded in some causal relationship in which p is a relatum for the chaining-type reasons identified in Mediation. (More on this later.)

So whether or not determination is transitive, the hypothesis that determination relationships can be chained together to build more encompassing determination relationships has much to be said for it. It’s just that if determination is transitive then one more thing can be said in favour of the hypothesis: it can help to explain the transitivity of determination.

Mediation itself, however, cannot be used to explain transitivity, as it does not tell us that, given two chained determination relationships, these relationships will serve to build another determination relationship. This is by design. There is good reason to doubt that determination is transitive, and thus good reason to ensure that our principles about derivative causation do not require that it is. Instead, Mediation aims to tell us about derivative causation in structures where transitivity does not fail, which in any case are the only structures in which derivative causation could possibly arise. So Mediation is not directly threatened by failures of transitivity. Unfortunately, however, it is possible to transform apparent counterexamples to the transitivity of determination into counterexamples to Mediation. The key to constructing these counterexamples is the observation that just because a path between cause and effect can be traced through intermediate determination relationships doesn’t mean that those intermediaries are the ones that actually build the relationship between the target cause and effect.Footnote 18 Before presenting one such example, let’s start with a standard counterexample to transitivity.

Suppose a boulder falls toward a hiker, causing the hiker to duck, which in turn causes him to survive (Hitchcock, 2001).

In cases like this we are inclined to deny that causation is transitive on the grounds that the boulder’s falling did not cause the hiker to survive. For precisely this reason—the relevant f fails to cause the relevant g—Mediation is not threatened by such cases. But suppose we enrich the causal structure of the example in the following way.

Boulder A falls toward a hiker, causing the hiker to duck, which in turn causes him to survive. But Boulder A’s falling also caused Boulder A to hit Boulder B, knocking Boulder B off course. And had Boulder A not fallen and knocked Boulder B off course, Boulder B would have struck and killed the hiker whether or not he ducked.

We now have a story in which there is no failure of transitivity. Here, Boulder A’s fall caused the hiker to duck which in turn caused the hiker’s survival, and Boulder A’s fall caused the hiker’s survival. This case thus falls under Mediation’s purview. This is bad news for Mediation, as here the principle incorrectly predicts that Boulder A’s fall causing the hiker to survive is grounded in it causing him to duck, which is the wrong result. Boulder A’s fall causing the hiker to duck has nothing to do with why Boulder A’s fall caused the hiker’s survival. Rather, the latter relationship is to be accounted for by appeal to the fact that Boulder A’s fall caused it to knock Boulder B off course, which in turn caused the hiker to survive.

It is possible to construct similar examples involving mixed determinational chains, but the case we already have in front of us suffices to make the point. What seems to have gone wrong for Mediation in this case is that the failure of determination relationships to add up along one chain—Boulder A’s fall caused the hiker to duck, which caused his survival—is masked by their successfully adding up along another chain—Boulder A’s fall caused Boulder B to be knocked off course, which caused the hiker’s survival—comprised of the same first and last events but a different intermediate event. Just as the primary lesson of the causal modelling literature has been that we must take into account the multiplicity of paths along which causal influence on an event might be conveyed (see e.g. Halpern & Pearl, 2005), so too the lesson of cases wherein determination relationships fail to add up without engendering any failure of transitivity is that we must be sensitive to how determination relationships add up along multiple paths, as the successful summing of determination relationships along one path can mask the failure of determination relationships to sum along another path. And, at the risk of harping on about the issue, note that this attractive explanation of what is going on in these cases requires not only that we take derivative causation seriously, but that we take it seriously even having rejected transitivity.

Let’s try to build this sensitivity to how determination sums along different paths into an amended version of Mediation. Let a determinational pathway be an ordered sequence of events linked by determination relations in a stepwise fashion, so that where f determines p and p determines g, ⟨f, p, g⟩ is a determinational pathway. By definition, determination is transitive across a determinational pathway P beginning in f and ending in g just in case f determines g. Let the variables Pi range over possibly nonactual determinational pathways beginning in f and ending in g.Footnote 19 Holding fixed that P exists, if there are some P1, …, Pn (we allow that n = 1) such that, nonvacuously, determination would not have been transitive across P if none of P1, …, Pn had existed, we will say that P exhibits ersatz transitivity.Footnote 20

Our double boulder example exhibits ersatz transitivity. Holding fixed that Boulder A’s fall caused the hiker to duck, which in turn caused him to survive, it is true that had it not been the case that Boulder A’s fall caused Boulder B to be knocked off course, which in turn caused the hiker to survive, then Boulder A’s fall would not have caused the hiker to survive. The idea, then, is that by ruling out ersatz transitivity in the right way we’ll thereby rule out the above sorts of cases where determination relationships fail to add up, and will thus have a way of guarding our principles of derivative causation against counterexample. I will implement this strategy by adding to each subcondition in condition (ii) of Mediation the requirement that the pathway mentioned in that subcondition not exhibit ersatz transitivity, yielding:

- Derivation::

-

f caused g derives from p caused q if

-

(i)

f caused g and p caused q, and

-

(ii)

-

(a)

f = p and q determines g, and ⟨f, q, g⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, or

-

(b)

g = q and f determines p, and ⟨f, p, g⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, or

-

(c)

f determines p and q determines g, and ⟨f, p, q, g⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity.

-

(a)

-

(i)

Derivation makes the correct predictions about derivative causation in every example we’ve looked at, and is supported by the same general considerations as Mediation. There is thus good reason to think that when the conditions stated in Derivation are satisfied, there is derivative causation.

5 Higher level, yet more fundamental

Derivation has some unsurprising consequences. It tells us that high level causation sometimes derives from lower level causation. Suppose that high caused higher, where high is some high level event, and that high caused lower, where lower is some event which is at a lower level of reality than higher, which it grounds. It follows that the relationship high caused higher is high level, and that the relationship high caused lower is comparatively lower level. Assuming ⟨high, lower, higher⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, Derivation tells us that high caused higher derives from high caused lower—an instance of high level causation deriving from lower level causation. To illustrate: my adjusting the thermostat’s causing the temperature of the room to increase—an instance of high level causation—derives from my adjusting the thermostat’s causing molecules in the room to move faster—an instance of comparatively lower level causation.

Derivation also tells us—again unsurprisingly—that higher level causation sometimes derives from low level causation. Suppose that low caused lower, where low is some low level event, and that low caused higher, where higher is some event which is at a higher level of reality than lower, in which it is grounded. It follows that both relationships are low level, but that in spite of this, the relationship low caused lower is lower level than low caused higher. Assuming ⟨low, lower, higher⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity Derivation tells us that low caused higher derives from low caused lower—an instance of higher level causation deriving from low level causation. To illustrate: let n0 and n1 be two low level physical events in my brain, such that n1 grounds my feeling melancholic. causing of n1—an instance of low level causation—grounds n0’s causing of my melancholy—an instance of comparatively higher level causation.Footnote 21

Yet another unsurprising consequence of Derivation is that high level causation sometimes derives from low level causation. Suppose that high caused low0 which in turn caused low1, and that high caused low1. The second of these three causal relationships is low level, the third is high level. Assuming ⟨high, low0, low1⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, Derivation tells us that high caused low1 derives from low0 caused low1—an instance of high level causation deriving from low level causation. To illustrate: the scientist’s pressing the button caused the emission of the photon, which caused the mark on the screen. The emission of the photon causing the mark on the screen—an instance of low level causation—grounds the scientist’s pressing the button causing the mark on the screen—an instance of high level causation.

In all three of the above cases, the relative fundamentality of the causal relationships tracks the relative fundamentality of their relata. But—and here’s where we get to the surprising consequences—Derivation tells us that this won’t always be so. Sometimes both low and lower level causation derive from high level causation. Suppose that low caused high1, where low is some low level event and high1 some high level event, and that high0 caused high1, where high0 is some high level event that is grounded in low. It follows that low caused high1 is low level, and that high0 caused high1 is high level, and that the latter is higher level than the former. Assuming ⟨low, high0, high1⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, Derivation tells us that low caused high1 derives from high0 caused high1—an instance of low level causation deriving from causation that is both high and higher level.Footnote 22 To illustrate: let n be a low level physical event in my brain that grounds my feeling thirsty. n’s causing of my drinking—an instance of low level causation—derives from my thirst’s causing of my drinking—an instance of high and comparatively higher level causation.Footnote 23

Because this result is so surprising, the notion that pathways with the structure ⟨low, high0, high1⟩ need not exhibit ersatz transitivity, and the notion that ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩ in particular does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, both deserve some comment.Footnote 24 My comments on the first notion will be brief. The Martha Stewart case has the structure ⟨Stewart’s sale of certain stocks, Stewart’s breaking the law, Stewart’s going to prison⟩, and thus has the structure ⟨low, high0, high1⟩. I see no reason to think that there are other pathways between Stewart’s sale of those stocks and her going to prison, whether actual or not, such that the transitivity of determination across ⟨Stewart’s sale of certain stocks, Stewart’s breaking the law, Stewart’s going to prison⟩ depends on those pathways.

Things are not so straightforward in the case of ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩. For it is plausible that in this case we can isolate a low level physical event d such that (i) d was caused by n and (ii) it was in virtue of d’s occurrence that I drank. Given this, another determinational pathway running from n to my drinking will be ⟨n, d, my drinking⟩.Footnote 25 For this reason, one might worry that, holding fixed the existence of ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩, if no ‘low road’ from n through some potential ground of my drinking (like d) to my drinking itself had existed, then n wouldn’t have caused my drinking, in which case ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩ will exhibit ersatz transitivity. If this is right, then Derivation will not tell us that n’s causing of my drinking is grounded in my thirst’s causing of my drinking.

But this is not right. I say this for several reasons. One is that the machine example from note 21 has already shown us that the transitivity of determination across a ‘high road’ like ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩ need not depend on the existence of ‘low roads’ connecting the ends of the pathway like ⟨n, d, my drinking⟩. Imagine a variation on that example in which we’ve gotten rid of the causal connection between scarlet and viridian flashes, thereby getting rid of any low road like ⟨the first machine flashing scarlet, the second machine flashing viridian, the second machine flashing green⟩ running from the first machine flashing scarlet to the second machine flashing green, but in which we’ve preserved the high road between the first machine flashing scarlet and the second machine flashing green ⟨the first machine flashing scarlet, the first machine flashing red, the second machine flashing green⟩. Here it is clear that our removal of a low road has done nothing to prevent determination from remaining transitive across the high road. The first machine flashing scarlet would clearly still cause the second to flash green (because in virtue of flashing scarlet it flashed red, and because its flashing red caused the other machine to flash green) even if the first’s flashing scarlet hadn’t caused the second to flash viridian. Why think that the drinking case is any different?

Indeed, the high roads in both these cases bear a signature of non-ersatz transitivity that is absent from the pathway ⟨Boulder A’s fall, the hiker’s ducking, the hiker’s survival⟩ in the double boulder case. Though perhaps we aren’t pretheoretically inclined to think that (as e.g. Mediation insists) n caused me to drink because my thirst caused me to drink, we certainly are pretheoretically inclined to think that n caused me to drink because n was a way for me to feel thirsty. Similarly, we are pretheoretically inclined to think that the first machine’s flashing scarlet caused the second machine to flash green because the first machine’s flashing scarlet was a way for it to flash red. These data are relevant to ersatz transitivity because they indicate that the causal connections between n and my drinking, and the first machine’s flashing scarlet and the second machine’s flashing green, are due in part to the grounding connections between n and my feeling thirsty and the first machine’s flashing scarlet and its flashing red, respectively. And when the connection between the first and second events on a pathway plays a role in explaining the connection between the first and third events on that pathway, this is a sign that the latter connection owes its existence to that pathway, and hence that the pathway does not exhibit ersatz transitivity.

The contrast between the pathway ⟨Boulder A’s fall, the hiker’s ducking, the hiker’s survival⟩ and the pathway ⟨Boulder A’s fall, Boulder B’s being knocked off course, the hiker’s survival⟩ from the double boulder case further attests to this. For there we are inclined to say that the fall of Boulder A caused the hiker to survive because it caused Boulder B to be knocked off course, but not that the fall of Boulder A caused the hiker to survive because it caused the hiker to duck. And again these inclinations line up with the facts about which pathways exhibit ersatz transitivity and which do not.

A final reason to think that ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity is that, even having supposed away low roads like ⟨n, d, my drinking⟩, if we hold fixed the existence of ⟨n, my feeling thirsty, my drinking⟩ then n will still play the functional roles of a cause with respect to my drinking. The occurrence of n will remain predictive of my drinking, manipulating whether or not n occurs will remain a way of manipulating whether or not I drink, the occurrence of n will still explain why I drank, there will still be objective reason to bring about n in pursuit of seeing me drink,Footnote 26 and someone could still be responsible for my drinking in virtue of bringing about n. Crucially, the same is not true in the double boulder case. There, if we remove the connection between Boulder A’s fall and the hiker’s survival via the path ⟨Boulder A’s fall, Boulder B’s being knocked off course, the hiker’s survival⟩, Boulder A’s fall no longer plays the functional roles of a cause with respect to the hiker’s survival even holding fixed the existence of ⟨Boulder A’s fall, the hiker’s ducking, the hiker’s survival⟩. The fall of Boulder A is no longer predictive of the hiker’s survival, manipulating whether or not Boulder A falls is no longer a way of manipulating whether or not the hiker survives, the fall of Boulder A no longer explains why the hiker survived, there is no longer reason to bring it about that Boulder A falls in pursuit of seeing the hiker survive, and it is no longer the case that someone could be responsible for the hiker’s survival in virtue of making Boulder A fall.Footnote 27

On his basis, we can confidently claim to have in our possession a well-motivated principle about derivative causation—Derivation—which entails that my feeling thirsty caused me to drink grounds n caused me to drink. Why, then, does this result remain so counterintuitive? One potential reason we find it so surprising is that my thirst depends on n, which might prompt us into thinking that the causal relationships my thirst enters into should likewise depend on the causal relationships n enters into. While I feel the pull of this thought—a thought that, as Sartorio (2006) points out, was arguably endorsed by Kim (1974)—I think it is ultimately just an understandable mistake. Perhaps the most obvious reason the thought must be mistaken is that the dependence relationships between the relata of a pair of causal relationships needn’t have a consistent direction. We might have a structure like that depicted in Fig. 7, wherein f causes g, p causes q, f grounds p, and q grounds g. Here one of f caused g’s relata depends on one of p caused q’s relata, but so too does one of p caused q’s relata depend on one of f caused g’s relata. There is thus no way to respect the requirement that dependences between causal relationships reflect dependences between their relata in such structures, so it cannot be a genuine requirement on derivative causation.

A more concrete problem with the same thought becomes clear when we consider cases involving purely causal chains. Here, dependence between relationships can clearly run in the opposite direction to dependence between relata, as when the jury’s verdict causing Socrates’ death depends on Socrates’ drinking hemlock causing his death, in spite of the fact that Socrates’ drinking hemlock depends on the jury’s verdict. It is no obstacle to the existence of this dependence of one causal relationship on another that the cause in the independent relationship itself depends on the cause in the dependent relationship. We must simply accustom ourselves to the corresponding result in certain mixed determination chain cases.Footnote 28

Why are we inclined to make this mistake? Perhaps because we conflate the thought that dependence between relationships must reflect dependence between relata with the closely related thought that dependence of relationships on relata must reflect dependence between relata. Here is what I mean. Since n grounds my thirst, my thirst depends on n (though not necessarily in the simple counterfactual sense). And since causal relationships plausibly depend on the occurrence of their relata, it follows that there is stepwise dependence of any causal relationship my thirst enters into on n. Assuming, as is plausible, that this stepwise dependence amounts to fully fledged dependence in these cases, it follows that the causal relationships my thirst enters into depend on the occurrence of n. This thought does indeed seem plausible, and not at all like a mistake. It says that (modulo worries about transitivity) causal relationships depend on what their relata depend on. It is quite possible, however, to endorse this thought without committing to the mistaken thought that dependences between causal relationships straightforwardly reflect the dependences between their relata.

Another reason we might be surprised by the claim that lower level causation sometimes derives from high level causation is a tacit commitment to the principle that no entity can be more fundamental than its least fundamental constituent. A forest, for instance, is constituted by many atoms, but it would be wrong to say that forests occupy the same level as atoms, or even a nearby level. We can explain why this would be wrong by appeal to the fact that in addition to being constituted by atoms, forests are also constituted by trees, and trees occupy a much higher level than atoms. Given the principle that nothing is more fundamental than its least fundamental constituent, it follows that forests reside at a level at least as high as that of trees.

Applying this principle to causation and levels, it is perhaps tempting to conclude that since, by definition, the events partly constituting high level causal relationships are no more fundamental than those partly constituting lower level causal relationships, the former relationships can never be more fundamental than the latter. But this simply does not follow from the aforementioned principle. So long as both high and lower level causal relationships are no less fundamental than their least fundamental constituents, the principle is respected. And this is compatible with, say, both relationships being less fundamental than the cause in the high level relationship, while the high level relationship is nonetheless more fundamental than the lower level one.

In fact, if one takes the chaining idea behind Derivation seriously, then the principle under consideration immediately militates in favour of a view on which lower level causal relationships needn’t be more fundamental than their high level counterparts. The chaining idea has it that when p grounds f and f caused g, then (assuming ⟨p, f, g⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity) the ‘chained’ relationship p caused g is partly built from one of the links in the chain: f caused g. Given that built things are partially constituted by their building blocks, lower level causal relationships like p caused g will sometimes have their higher level counterparts, like f caused g, among their constituents. The principle under consideration would then have it that the lower level relationship is no more fundamental than the high level one.

Yet another reason one might be surprised by what Derivation has to say about high level causation grounding lower level causation is that this sort of derivative causation is implausible in cases like the following. Suppose that our old friend n—the highly specific neural event that grounds my feeling thirsty—caused the neural event that succeeded it, nʹ (which we will suppose to have preceded my drinking). And suppose further that my feeling thirsty was also among the causes of nʹ. Then Derivation will have it that n caused nʹ because my feeling thirsty caused nʹ. But this seems wrong—n did not have to go via my feeling thirsty in order to produce nʹ. The process that led from n to nʹ took place entirely at the neural level.

Granting that my thirst caused nʹ, the above argument would indeed put pressure on Derivation. But I see no reason to grant this premise. Causes might not have to be fully proportional to their effects as e.g. Yablo (1992) says they must (after all, Socrates’ drinking poison is better proportioned to his death than his drinking hemlock—any poison would have done the job—but the latter is still among the causes of his death), but that doesn’t mean that just any event grounded by a cause will be a cause of the same. The jury’s convicting Socrates caused his death, but the jury’s convicting someone (an act they performed in virtue of convicting Socrates) didn’t. So it is with the above case: though n grounds my thirst, my thirst nonetheless fails to cause something that n causes, namely nʹ.

Far from being a reductio of Derivation, then, the above argument is actually a reductio of certain kinds of downward causation—i.e., causation of a lower level event by a high level event. Indeed, one can see Derivation as crystallising previously inchoate worries about downward causation into a sharp concern: downward causation requires that low level physical causal linkages depend on causation at higher levels, which is not always plausible. Bringing these dependences to the fore enables us to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable instances of downward causation. Since it is implausible that n caused nʹ because my thirst caused nʹ, Derivation precludes my thirst from being a downward cause of nʹ. But since it is plausible that the physical event that grounds the scientist’s pressing the button caused the emission of the photon because the scientist’s pressing the button caused the emission of the photon, the pressing isn’t ruled out as a downward cause of the emission.

An important corollary of the limitations on downward causation imposed by Derivation is that a widely endorsed thesis about causation is false, namely that nonbacktracking counterfactual dependence (see Lewis, 1979) between wholly distinct events suffices for causation.Footnote 29 Suppose that if n hadn’t occurred then its effect nʹ wouldn’t have occurred either. Then, since n necessitates my thirst (a convenient but dispensable assumption), n would not have occurred had I not felt thirsty, and hence nʹ wouldn’t have occurred either. However, paying due attention to derivative causation reveals that the counterfactual dependence of nʹ on my thirst is no guarantee that the latter causes the former.Footnote 30

A final reason for our intuitive surprise at the central thesis of this paper could be an intuitive commitment to ‘reducing’ high level causation to lower level causation, of a certain sort. When I throw a rock into a window and the window shatters, we are wont to say that my throw caused the shattering—a high level causal relationship—but that this is grounded in innumerable instances of lower level, microphysical causation: a collision between one of the rock’s atoms and one of the window’s atoms causing the latter to move; a collision between another of the rock’s atoms and another of the window’s atoms causing the latter to move; and so on. The high level causing seems to happen in virtue of all these low level causings.Footnote 31

I am happy to admit this, but again in doing so I make no quarrel with Derivation. While Derivation does not entail the above instances of derivative causation, it is quite compatible with them, and even with a more ambitious project of grounding all high level causation in lower level causation of this sort (Strevens, 2008 pursues this kind of project).Footnote 32 That said, Derivation is inconsistent with some antecedently plausible ways of grounding high level causation in lower level causation. In particular, it entails the falsity of the thesis that each high level f caused g is grounded in every relationship p caused q such that (i) p is low level and grounds f and (ii) q grounds or is identical to g, as well as a strengthened version of this thesis that changes (i) to require only that p ground f. To see why, consider the high level causal relationship between my thirst and my drinking, and the low level causal relationships between n and my drinking. Since n is low level and grounds my feeling thirsty, both aforementioned theses entail that n caused me to drink grounds my feeling thirsty caused me to drink. But we have already seen that Derivation entails that the grounding relationship goes in the other direction in this case. Since ground is asymmetric, this prediction of the above theses is inconsistent with Derivation.

These principles bear a resemblance to some of the so-called ‘causal inheritance principles’ discussed in the literature, such as the following principle inspired by Kroedel and Schulz (2016): every high level f caused g is grounded in some p caused g where p grounds f.Footnote 33 Derivation reveals this principle to be false as well. For in any case in which f caused g, p caused g and p grounds f, and in which ⟨p, f, g⟩ does not exhibit ersatz transitivity, Derivation will rule that p caused g is grounded in f caused g, which is inconsistent with the verdict of the aforementioned principle given the asymmetry of ground.

The foregoing discussion of the rock and the window revealed a kind of derivative causation that we have not yet discussed. Unlike the derivative causation in our existing taxonomy (as catalogued by Derivation), this sort of derivative causation is not a manifestation of the construction of a causal relationship by way of the chaining together of other determination relationships. Rather, it stems from the way in which parts of whole causes cause parts of whole effects. The existence of this extra kind of derivative causation demonstrates that Derivation only has good prospects as a sufficient condition for the phenomenon.

I refrain from adding extra clauses to Derivation so as to cover this new case, and perhaps thereby render the condition both necessary and sufficient for derivative causation because this new case reveals derivative causation to be a heterogenous phenomenon. While it loosely seems to involve ‘construction’ in all its manifestations, the ways in which one causal relationship can be constructed from others are many and varied. Sometimes this construction involves chaining, and other times it involves parts of cause-wholes causing parts of effect-wholes.

And in fact there is likely to be yet another sort of derivative causation in cases where one causal relationship grounds an event that figures in another causal relationship, as causal relationships will typically depend on what their relata depend on. For instance, Oswald’s killing Kennedy caused a nation to mourn. But Oswald’s killing Kennedy is grounded in Oswald’s pulling the trigger causing Kennedy to die. And since Oswald’s killing Kennedy in turn partly grounds Oswald’s killing Kennedy causing a nation to mourn, it is plausible that Oswald’s pulling the trigger causing Kennedy to die grounds Oswald’s killing Kennedy causing a nation to mourn—an instance of derivative causation. So sometimes causal relationships are constructed by event-building, it seems.Footnote 34 It is hard to see how we might extract a pattern from these three kinds of structure that would allow us to be confident that we have now surveyed every kind of derivative causation.

Derivation thus only purports to cover a certain kind of derivative causation. It is, however, a particularly important kind—the kind associated with mediated causation.Footnote 35 Testifying to the importance of mediated causation are the various philosophical uses the two have been put to in, for instance, understanding action (Goldman, 1970, in his analysis of ‘level generation’ and the by locution), understanding what it is to do good and do bad (Pettit, 2018), and understanding ways-for-it-to-be-that-φ, truthmaking, parthood, subject matter, helpfulness/contribution/relevance, and other cognate notions (Yablo, forthcoming).

More explicitly, my conjecture is that (i)–(ii) of Derivation are satisfied just in case it is true for the f, g, p and q mentioned therein either that f caused g by making p happen, or that f caused g by making q happen. On this view, whenever we make a claim to the effect that the causal relationship between events f and g is mediated by a third event p, we are thereby committed to f caused g being grounded by some causal relationship in which p figures as a relatum. If the fall of the first domino causes the third to fall by making the second fall, then the fall of the first causing the fall of the third is grounded in some causal relationship in which the fall of the second domino figures as a relatum. In particular, it is grounded in the fall of the first domino causing the fall of the second domino, and in the fall of the second domino causing the fall of the third. And likewise we can move from claims of derivative causation in the sense captured by Derivation to claims of mediated causation. If the fall of the first causing the fall of the third is grounded in the fall of the first causing the fall of the second, then the first’s fall caused the third’s by making the second fall.Footnote 36

Further testifying to the plausibility of this conjecture is the apparent synonymy of ‘f caused g by making p happen,’ with ‘f caused g in virtue of making p happen’. If genuine, this synonymy means that when f causes g by causing p it also causes g in virtue of causing p, which is precisely the sort of derivative causation that the conjecture associates with these claims of mediated causation.

6 Conclusions

The principles we have found to underly derivative causation militate in favour of a dependentist perspective on the relationship between high and lower level causation, as, given plausible auxiliary assumptions, they entail that relationships of dependence will often obtain between causal relationships of each sort. But more than this, they militate in favour of a particularly striking version of dependentism on which lower level causal relationships will often depend on their higher level counterparts. One might doubt, however, that my arguments will be found compelling by partisans of other perspectives. Sure, derivative causation might persuade independentists to change their ways, but what about epiphenomenalists, gappists, and identitarians? Both epiphenomenalists and gappists deny the existence of some of the causal relationships that figure crucially in the examples I used to illustrate the phenomenon of derivative causation, and it is open to identitarians to deny that these causal relationships are apt to enter into grounding relationships with one another due to their being identical.

This way of viewing the dialectic, however, understates the persuasive force of my position, as it fails to account for the way in which what I have said undermines some popular motivations for epiphenomenalism, gappism, and identitarianism. One particularly influential reason that has been cited in favour of each position is that causal relationships at different levels compete for their existence.Footnote 37 If n and my feeling thirsty are indeed distinct events, they do battle with one another for the status of being a cause of my drinking, with only one coming out victorious. Or, at least, this is the idea. The epiphenomenalist who is motivated to adopt their position because of this kind of worry about causal competition says the battle goes to n, the similarly motivated gappist says it goes to my feeling thirsty, and the similarly motivated identitarian seeks to avoid conflict altogether by saying that n and my feeling thirsty are one and the same.

In response, I say that causal competition is but a mirage! Our findings about derivative causation tell us that far from being in competition for causal status, the causal relationship between e.g. my feeling thirsty and my drinking actually supports the causal relationship between n and my drinking. So to the extent that epiphenomenalists, gappists, and identitarians are motivated by the bogeyman of causal competition, I say that they should instead be dependentists, and indeed should embrace the provocative version of this view on which low level causation can be built out of high level causation.

Notes

Following Schaffer (2009), I am permissive about what sorts of things stand in grounding relationships, allowing for facts, relations, relationships, events, properties, laws, particulars and what have you to be both grounds and grounded. [I also follow Schaffer (2009), Rosen (2010) and Audi (2012) in treating ground as a relation, in contrast to those who regiment grounding talk with a sentential operator, like Correia (2010) and Fine (2012a).] If one insists on reserving the term ground for a relation that holds between facts, then the relation I have in mind might be termed metaphysical or ontological dependence (see Rydéhn, 2018). There is every reason for those who are happy to relate facts with ground to be happy to relate all manner of other things with metaphysical dependence (e.g. whole objects with their parts). In particular, it is natural for such philosophers to hold that when the fact that x occurs grounds the fact that y occurs, the event y metaphysically depends on the event x. (For those who think the causal relata are facts, like Mellor [1981] and Bennett [1988], no such retreat from ground to metaphysical dependence is necessary.) And for those sceptical that there are any generic relations of metaphysical dependence, note that the purposes I put grounding to in this paper could equally well be served by a combination of more specific dependence relations, such as the realisation relation, the determinate-determinable relation, the species-genus relation, etc.

Examples of philosophers who talk this way include List & Menzies (2009, p. 477) and Sinnott-Armstrong (2021, p. 868), who speak of high level causation given only a high level cause and an arbitrary physical effect, as well as Gibbs (2014, p. 330) and Hoffmann-Kolss (2014), both of whom treat ‘f is a high level cause of g’ and ‘f caused g is an instance of high level causation’ as interchangeable. This contrasts with some, like Kistler (2017, p. 54), who reserve the moniker high level causation for causal relationships wherein both the cause and effect are high level. Though my terminological choices align with the former group of philosophers, my argument that lower level causation is often built from higher level causation goes through on either understanding of the relevant terms.

In general there is no straightforward connection between the relative levels occupied by some entities and the presence or absence of grounding relationships between those entities. The United Kingdom is higher level than an atom in Andromeda, for instance, but the latter does not ground the former. And a collision between two atoms will be partially grounded in the behaviour of each of those atoms, but it would be a stretch to say that the collision occupies a higher level than does the behaviour of each of the two individual atoms.

I use italics to signal that the italicised phrase denotes a relationship. I will sometimes also refer to a causal relationship f caused g by way of phrases such as ‘f’s causing of g’ and ‘f causing g’.

Unless otherwise stated, every grounding claim I make should be understood as a claim about (strict, factive) partial ground (see Fine, 2012b).

I assume that the causal relata are fine-grained, so that we may distinguish between such intimately related things as my feeling thirsty and the neural event that realises it, qua causal relata. Talking, as I do, as though the causal relata are events thus involves talking as though different events can occupy the same spatiotemporal region. But this is just a way of talking—not a substantive assumption. What I say can be recovered in translation by those who deem the causal relata to be facts, property exemplifications, variable values or what have you, assuming these alternative relata are finely individuated and stand in the sorts of grounding relationships I take events to stand in.

These because claims are only diagnostic of derivative causation when we have something like this sort of building going on. That the striking of the match caused the match to light because the leak caused oxygen to enter the room is no sign of derivative causation in my sense of the term.

An anonymous referee points out that the claim that intermediate links in a causal chain ground the causal relationship between the first and last events in the chain is in tension with the idea that grounding is well-founded in the sense that every grounding chain terminates in one or more ungrounded things. For it is a plausible assumption that, for any f and g where (i) f caused g and (ii) f finishes occurring some nonzero length of time before g begins to occur, there will be some p such that f caused p and p caused g. (Note that this is different from the somewhat less plausible assumption that causation is dense in the sense that for any cause f of g there exists a p such that f caused p and p caused g. Even if we assume that causes must occur entirely prior to their effects, it might still be that no interval of time separates f from g.) If this is right, then f caused g will be grounded in p caused g, which in turn will be grounded in pʹ caused g (where p caused pʹ and pʹ is separated from g by a nonzero interval of time), and so on ad infinitum. But the above assumption is only plausible if time is dense (in the sense that there is always an instant of time between any two other instants), and the density of time is already enough on its own to generate a structurally similar threat to well-foundedness, whatever we think of derivative causation. Take, for instance, the existence of the temporal interval [t0, t100], which is grounded in the existence of the interval [t50, t100], which in turn is grounded in the interval [t75, t100], and so on ad infinitum. In light of this, I see no reason to think that my claims about derivative causation generate any novel threat to the well-foundedness of ground.

At various points in this paper I will use talk of making something happen as a more colloquial stand in for talk of one event causing or metaphysically grounding another. I do this in the present case so as to make manifest the intuitive force of the relevant claim, which would be reduced were we to substitute this colloquial manner of speaking for more technical talk of the grounding relationship running from Socrates’ death to Xanthippe’s widowing.

Why do chains of determination serve to construct causal relationships rather than grounding relationships when the chains comprise a mix of causal and grounding relationships, as in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8? One possible explanation is that ground is synchronic and causation diachronic. If this were right it would follow that the events at either end of a mixed determinational chain cannot be grounding-related since any such events are separated by a causal relationship and hence are not simultaneous. Under the same assumptions, chains composed entirely of grounding relationships could not ‘add up’ to causal relationships, hence their absence from our taxonomy, which means to catalogue only those chains that result in derivative causation.

This discussion also serves to reveal the mistake in a more general objection to derivative causation. The objection has it that if causation is counterfactual dependence (or whatever else you like), then positing derivative causation of any sort (whether due to the chaining of determination relationships or not) is idle. Even if, say, f and g are connected by a chain of causal relationships, their causal relatedness consists directly in the counterfactual dependence of g’s occurrence on f’s occurrence—no need to build up the relationship between the two events by way of intermediate relationships. But, as we have just seen, it may well be that the counterfactual dependence between f and g is itself built from other causal relationships/counterfactual dependences, in which case the appearance that the truth conditions for ‘f caused g’ bypass these intervening causal relationships is but an illusion.

I think these modified counterexamples actually reveal that, against the current of existing literature on the topic, which focuses on failures of the transitivity of determination per se, we should instead be concerned with failures of chained determination relationships to build the more encompassing relationships that they succeed in building in normal cases, as failures of transitivity are merely a symptom of this underlying phenomenon.

I allow for the Pi to be nonactual in order to deal with redundant causation. It might, for instance, have been that if Boulder B had never fallen, and so the pathway ⟨Boulder A’s fall, Boulder B’s being knocked off course, the hiker’s survival⟩ had not existed, then Boulder C would have fallen in such a way that, had Boulder A not knocked it off course, then Boulder C would have killed the hiker regardless of whether he ducked. In this case, the transitivity of determination across ⟨Boulder A’s fall, the hiker’s ducking, the hiker’s survival⟩ does not depend on the existence of ⟨Boulder A’s fall, Boulder B’s being knocked off course, the hiker’s survival⟩ alone, but on the existence of at least one of ⟨Boulder A’s fall, Boulder B’s being knocked off course, the hiker’s survival⟩ and ⟨Boulder A’s fall, Boulder C’s being knocked off course, the hiker’s survival⟩, where the latter pathway is nonactual.

In setting things up this way, I am tacitly assuming that if determination would have failed to be transitive along a pathway had some other (possibly nonactual) pathways not existed, then determination would have failed to be transitive along that pathway had some other pathways beginning and ending with the same events not existed. More general setups are available if need be.

An interesting variation on this sort of structure involves a lower0 causing a lower1 and a higher0 causing a higher1, where lower0 grounds higher0 and lower1 grounds higher1. Here Derivation tells us that lower0 caused lower1 grounds lower0 caused higher1 and that higher0 caused higher1 grounds lower0 caused higher1. This seems like the right result. Consider two machines that flash different coloured lights at one another according to the following rules: the second machine will emit a green flash if and only if the first emits a red flash, and will emit a viridian flash if and only if the first emits a scarlet flash (both machines can generate flashes in all manner of different shades of different colours). If on an occasion the first machine flashes scarlet and the second returns a viridian flash, we will have a case with the above structure, as the scarlet flash grounds the red flash which in turn causes the green flash, and the scarlet flash causes the viridian flash which in turn grounds the green flash. Here it seems right to say that the scarlet flash caused the green flash both because the red flash caused the green flash and because the scarlet flash caused the viridian flash, as predicted by Derivation. But this is different from the way in which the causal relationships that result from purely causal chaining are multiply grounded in other causal relationships, as there the causal relationships doing the grounding clearly don’t overdetermine the obtaining of the grounded relationship. Here, by contrast, it is more natural to take the obtaining of the causal relationship between the scarlet flash and the green flash to be overdetermined by the causal relationships that ground it. Given that it doesn’t bear directly on my main arguments, however, I won’t take a stand on this issue one way or the other.

All four of the above results are independent: none entails any other (though the individual cases used to illustrate the results are sometimes instances of multiple results).