Abstract

The problem of skepticism is often understood as a paradox: a valid argument with plausible premises whose conclusion is that we lack justification for perceptual beliefs. Typically, this conclusion is deemed unacceptable, so a theory is offered that posits conditions for justification on which some premise is false. The theory defended here is more general, and explains why the paradox arises in the first place. Like Strawson’s (Introduction to logical theory, Wiley, New York, 1952) “ordinary language” approach to induction, the theory posits something built into the very notion of justification: it is loaded with a bias towards the proposition that we are not massively deceived. Beyond the paradox, remaining skeptical problems consist of metaphysical and practical questions: whether we are massively deceived, or why we should use our loaded notion rather than some other. Such challenges have profound epistemological significance, but they are not problems that an a priori theory of justification can solve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The problem of skepticism is often understood as a paradox: a valid argument with seemingly plausible premises whose conclusion is that we lack justification for perceptual beliefs. Typically, this conclusion is deemed unacceptable, so a theory is offered that specifies conditions for justification on which some premise in the skeptical argument is false. Solving the paradox in this way is a major, if not the main, role that theories of justification serve in contemporary epistemology. A different sort of theory of justification is presented here. It posits something more general about the notion of justification, which explains why theories of justification reject the skeptical conclusion, and why the paradox arises in the first place. Like Dogramaci (2012) and Schafer’s (2014) recent contributions, the theory aims to shed light on the concept of justification by considering its function. Like Strawson’s (1952) “ordinary language” approach to the problem of induction, the theory posits that there is something built into the very notion we use to evaluate our beliefs. The basic idea is that the notion of justification is loaded with a bias towards the proposition that we are not massively deceived.

After applying Strawson’s “analytic” approach to perceptual justification and using it to explain the paradox, I will consider the main objections to Strawson that may be thought to apply to the view defended here. A new picture emerges of the role of theories of justification in answering skeptical challenges. If our notion of justification is loaded, the paradox amounts to the challenge: Is there something we could plausibly mean by ‘justified’ that is properly epistemic and avoids commitment to the premises of the paradox? The remaining, other skeptical problems consist of other, metaphysical and practical challenges. Such challenges have profound epistemological significance, but they are not problems about the conditions for justification, as most epistemologists have taken skepticism to be. If one is interested in a metaphysical or practical skeptical question, such as whether we are massively deceived, or why we should use our loaded notion rather than some other, then the loadedness of justification does nothing to help. But neither does any theory of justification, I will argue.Footnote 1

1 The paradox and theories of justification

In this section I briefly outline the paradox and the way in which theories of justification are typically used to solve it.

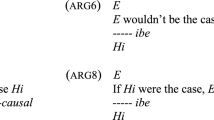

Let ‘p’ stand for some contingent, external-world proposition that we typically believe on the basis of perception, such as that there are hands; let ‘sk’ stand for some skeptical hypothesis according to which you are massively deceived about things such as p. A typical skeptical argument has this form:

-

(1)

You don’t have justification to believe ~sk.

-

(2)

If you have justification to believe p, then you have justification to believe ~sk.

So,

-

(3)

You don’t have justification to believe p.

Though this is the most common formulation in recent discussions, there are variations. For example, while most discussions appeal to a “closure” principle to motivate (2), some instead appeal to an “underdetermination” principle, according to which having justification to believe p implies that one’s evidence favors p over all of p’s alternatives, including sk. Much of my discussion concerning (1)–(3) can be applied to such alternative formulations of the paradox. However, the relation between closure and underdetermination is disputed, and adjudicating this would take us too far afield. So, let us just assume that some kind of closure principle motivates (2).Footnote 2

The conclusion, (3), is usually taken to be unacceptable, so (1)–(3) constitutes a paradox, and solving it requires explaining how one of the premises is false. (2) is widely—though not universally—accepted, especially for versions of sk on which p logically entails ~sk. And, though most are comfortable asserting that (1) is false, it has proven difficult to show how it could be false, or what our justification for believing ~sk could be. Another element of the debate about justification is that a theory must account for why the paradox arose in the first place.Footnote 3 As we will see, the loadedness of justificationFootnote 4 provides a good explanation for why justification to believe ~sk is so hard to specify, and why the paradox arises. For now, recall the usual difficulties with refuting (1). There seems to be no obvious a priori evidence or argument for the deeply contingent proposition that ~sk, and any appeal to non-a priori, or empirical evidence seems, prima facie, inappropriately question-begging or circular. For, things would seem empirically just as they do now if sk were true, and how could appealing to the way things look show, by itself, that things are the way they look? Famously, some have proposed a priori arguments,Footnote 5 and some have argued that there is no serious problem with appealing to empirical premises in the context of justifying belief in ~sk.Footnote 6 But the difficulty of establishing these views is familiar from the literature of the past few decades.Footnote 7

Theories of justification are meant to address the paradox by positing conditions for justification on which either (1) or (2) is false. For example, a theory of justification might state that having justification to believe ~sk is not a necessary condition on having justification to believe p.Footnote 8 If so, then (2) is false and we have avoided conclusion (3). Another example is the view that we have perceptual justification to believe ~sk (perhaps the justification arises from an inference from simple perceptual premises).Footnote 9 Then (1) is false and (3) is avoided. Defending such theories requires making plausible observations about justification and explaining away rival intuitions. This is the bulk of the work done in the theory of justification.

There are different ways of understanding the term ‘justification’ in epistemology. The primary focus of most of this paper is the sort of justification at issue in the paradox. The solutions that are discussed here are not meant to be “dissolutions,” or theories according to which there is no real problem or puzzle to begin with. If we take seriously the idea that the paradox presents an interesting problem for justification, we cannot take justification to be merely a positive status relating to the virtue, usefulness, or indispensability of a belief. For, unless something further is said about the virtue or utility in question, there is no reason to think that we lack such justification for believing ~sk. Instead, I take the justification at issue to be what philosophers call ‘epistemic’. This may suggest an essential connection with knowledge (episteme). But the justificatory status associated with knowledge, which is sometimes termed, following Plantinga (1993), ‘warrant’, is not the status I have in mind either. Rather, the paradox as it has appeared in the literature on justification involves a justificatory status in its own right, not necessarily in relation to knowledge. Justification here is a positive status that entails that a belief fares well with respect to its own likely truth, and this is what is typically meant by ‘epistemic’ in the literature.Footnote 10 Whether the “faring well” and the “likely truth” involved are subjective or objective, and what the conditions for them are, are controversies about this independent notion. As the idea that the notion is loaded is explained, below, the connection with the “likely truth” should become less obscure. When understood in this way, the case for (1) is clear, and solutions to the paradox begin to look difficult.

2 What it means for the notion of justification to be “loaded”

In this section I introduce the idea that justification is loaded and show how this resembles a Strawsonian claim that it is “analytic” that some beliefs or inferences count as justified.

As described above, theories of justification that address the paradox posit some conditions for justification on which either (1) or (2) is false. Usually, the theories do this by building a bias in favor of the reliability of our senses—or against the possibility that we are massively deceived—into those conditions. For example, conservatives such as White (2006) suggest that justification applies to our belief that we are not deceived, by default, or automatically (albeit defeasibly). And dogmatists such as Pryor (2000) hold that the appearance as of p is itself sufficient for immediate, prima facie justification to believe p. So, in using justification, one favors ~sk.Footnote 11 The central idea of this paper is that the bias displayed by these various theories of justification is a feature of the very notion of justification, since it is loaded. But what is loadedness, exactly?

To begin, consider a very rough description. We are used to the idea of a loaded question as one which has a controversial or charged assumption or implication. Like a loaded die or a biased source, a loaded question tips the balance in favor of some outcome (or answer), so it is not neutral with respect to the question. Likewise, a loaded notion, as I understand it, is a notion which, relative to some issue or topic, tips the balance in favor of some proposition. If the conditions of justification are such as to favor the conclusion that we are not deceived, then the notion of justification is loaded, at least with respect to the issue of whether we are so deceived. To be clear, the notion is “unfair” or “biased” only with respect to the question whether sk is true, and only in the sense that it is not neutral with respect to the truth value of sk. If you were debating whether sk is true, appealing to a notion that is loaded with the assumption that it is true is not conducive to “unbiased” investigation. As I explain below, there is good reason for people to use such a notion, even if it is not well-suited to investigations into the truth of sk. Use of the notion itself is not necessarily “unfair,” on this view, and indeed it is a very useful one for most purposes.

Why and how is justification biased in favor of ~sk in this way? The “why” is easy to answer. We live in a community in which everyone takes of granted, and assumes that everyone (else) takes for granted, that we are not massively deceived. It makes sense, then, that the notions we employ to evaluate our beliefs arise within, and incorporate, this assumption. This makes such notions loaded with respect to the philosophical question of whether we are deceived; the notion we use to evaluate beliefs is not neutral on our shared assumptions. Of course, the question remains, whether such a notion of justification tracks the objective truth, in the sense that justified beliefs are objectively likely to be true. This is the question whether we are, in fact, in a sk scenario. This is a legitimate question, but it poses a distinct challenge from the one posed by the paradox. I will take this issue up in Sects. 4 and 5, below.

But answering the “how” question can be more difficult, depending on how much detail we aim to provide. Just as there are different accounts of concepts in general, there can be different corresponding accounts of how a concept or notion can be loaded with an assumption. This gets into murky and controversial philosophical territory. Here, I offer some brief, possible outlines of how justification is loaded. This will serve to indicate how the details might be worked out, rather than to argue for any particular set of details.

One possibility, perhaps the most obvious one given that the idea is originally due to Strawson, is that a concept’s being loaded with an assumption amounts to that assumption being a “semantic presupposition.” That is, ‘justified’ “semantically presupposes” that our perceptual states are likely to be accurate. However, I will not pursue this idea because the very notion of semantic presupposition is, notoriously, controversial. And it is not clear whether the standard features of semantic presupposition are present here. For example, the negation of “S’s belief that p is justified,” which is “S’s belief that p is not justified,” does not obviously presuppose that our perceptual states are likely to be accurate. But, typically, negations of statements with presuppositions also have those presuppositions.

Presupposition aside, I will still take justification’s loadedness to be a matter of meaning. The idea is that whenever one uses ‘justified’, one must assume that, absent any information to the contrary, we are not massively deceived. That justification has this requirement would seem to constitute a form of loadedness. But the question immediately arises, why one must make this assumption, and in what sense “must” one make it. I suggest that the best way to explain why one might always be required to make this assumption is that this follows (in a way I will explain below) from what ‘justified’ means; and the sense in which one “must” make this assumption is, roughly, that otherwise one is not using our term ‘justified’ correctly. Both of these claims need to be further explained, of course. And, to be clear, I do not take this to be a proof that justification is loaded in the sense that some contingent assumption—that we are not deceived—is part of the notion of justification. Rather, what follows is a defense of a view that I take to be promising in various ways, and I think it best explains how our notion might be loaded.Footnote 12

According to Strawson, it is analytic that inductive inferences are reasonable, or justified [“this is what ‘being reasonable’ means in such a context” (1952, p. 257)]. Applied to perceptual beliefs, the idea is that it is analytic that forming beliefs on the basis of sensory experience is justified. One proponent of this idea is Cohen (2010, p. 156), who suggests that we count, as a brute fact, perceptual beliefs as “rational” or justified, and therefore likely true.Footnote 13 Since we simply count perceptual beliefs as justified and regard justified beliefs as more likely to be true, justification is loaded with the assumption that perception is reliable. For, by using justification, one simply counts perceptual beliefs as likely. Cohen has an “epistemic” sense of ‘likely’ in mind (e.g. 2010, p. 148), which depends on one’s available evidence, rather than objective likelihood. It may therefore be best to interpret this sort of loadedness as the view that justification is loaded with ~sk because we are, by default, justified in believing ~sk. One difficulty with this is the question of the relation between epistemic and objective likelihood, even granting that, from the subject’s own perspective, to judge that one’s own belief is epistemically likely at least commits one to the view that it is objectively likely. Setting this difficulty aside, Cohen’s Strawsonian view is a helpful first step towards understanding the loadedness of perceptual justification along Strawsonian lines.

A natural way to understand this is within a broadly inferentialist framework.Footnote 14 Consider an analogy. According to a famous example of Dummett’s (1973), the pejorative boche is characterized by the following basic, canonical introduction and elimination rules: If S is German then S is boche; and if S is boche then S is cruel. This suggests that possession of the notion boche requires endorsing an inference from “S is German,” to “S is cruel.” The notion is thus loaded with the assumption that all Germans are cruel. If one wondered whether Germans were cruel, ‘boche’ would straightforwardly be a problematically loaded notion to employ.

Given the controversies surrounding inferentialism, it is worth noting that this account of loadedness doesn’t imply or assume that concepts (or notions) are individuated by their canonical inferences, one’s willingness to make them, or one’s thinking that, all things considered, they are warranted. Nor does one need to accept that anyone who possesses the concept is willing or all things considered inclined to perform these inferences. One could possess the concept but refuse to use it because one thinks the inferences it licenses are bad, or rejects the assumption built into the concept via its basic inferences.Footnote 15

According to the features of justification I attributed to Cohen above, you can infer, merely by using justified, from “p is the content of a perceptual state” or “belief that p is a perceptual belief,” that “p is likely true.” Justification applies to perceptual beliefs and implies likely truth. Though Cohen had epistemic likelihood in mind, an externalist about justification could endorse a similar view about objective likelihood: perceptual beliefs are justified and therefore objectively likely to be true.Footnote 16 From an inferential perspective, this is what it means to say that justification is loaded with a bias towards ~sk. This perspective on loadedness fits well with dogmatist views of justification, according to which our perceptual justification is immediate. For, the introduction rule allows us to infer directly, from a belief’s being a perceptual belief, that the belief is justified. But many more details are required. For example, there could be other introduction rules—which leaves room for the possibility that some beliefs are also justified by default—since perception may not be the only source of justification.Footnote 17 And there may well be other elimination rules such that, in the presence of defeaters, the belief in question is not justified, and not necessarily likely, after all. This would happen, for example, if your course of experience leads you to the conclusion that you are massively deceived. In that case, your starting assumption, that ~sk, was defeated by your subsequent evidence.

However, these details may not be worth working out. For, one might reasonably consider boche to be defective, precisely because it facilitates such non-conservative inferences. And, presumably, we don’t want to say that justification is defective, at least not so straightforwardly. Whatever would make boche defective, we presumably prefer a theory of justification that does not entail that justification has the same problem.

Fortunately, there is a similar idea about technical terms that can be exploited here, and on this other idea, whether a concept is defective is not an a priori matter. Ramsey (1929) and Lewis (1972) famously held, roughly, that ‘mass’, in Newtonian theory, is semantically equivalent to ‘the property that obeys such-and-such laws’. Thus, employing the term ‘mass’ assumes that there is some such property. And the laws are, of course, substantive and contingent. Certain inferences are licensed by this assumption. For example, if x resists acceleration under force, then x has mass. And, if x has mass, then x gravitationally attracts other objects that have mass. So, the concept of mass is “loaded” with the assumption that objects that resist acceleration under force attract each other. In judging that something has mass, you thereby make that assumption by (implicitly) appealing to mass theory.Footnote 18

If justification resembles Newtonian mass in this way, then when employing the concept of justification, one assumes “justification theory,” according to which there is some property such that perceptual beliefs have it and anything that has it is objectively likely to be true. Justification is the property that, absent defeating information, obeys the “laws” of a world in which ~sk holds. Accordingly, justification is loaded with a starting assumption, or a bias, that ~sk. Of course, even in a non-deceptive world, it is possible for other evidence to make one’s perceptual beliefs not so likely after all. So, again, the justification “laws” of this world, which determine when a belief is justified, need to be considerably more complicated than the brief description given here. They specify sufficient conditions only for prima facie justification.

These accounts of how justification is loaded nicely match the account of why we would use such a notion. ‘Justification’ is a helpful label that mediates between our initial assumptions about the reliability of our faculties and our beliefs, perhaps because of its explicitly positive evaluative connotation (i.e. one is approving of, and encouraging, the beliefs that one calls ‘justified’). It is easy to see why beings like us would come to use such a notion, just as it is easy to see why a population that universally assumes that all Germans are cruel would use boche. We all accept, absent any special information, that we are not massively deceived, and we expect that others in our community accept that too. We are biased, and so are our notions.

There are different ways in which our bias manifests itself in our notion of justification, and these correspond to different theories of the conditions of justification. We have seen that on one kind of theory, justification is loaded with the assumption that perceptual beliefs are epistemically likely, or that belief that ~sk is (absent defeating evidence) justified. This is one, internalist way in which the notion can be biased. And another kind of theory has it that justification is loaded with the assumption that ~sk, or that perceptual beliefs are objectively likely—they are merely likely only because there are ways for a perceptual belief to be false aside from some skeptical scenario holding, so they are never guaranteed to be true. Of course, even externalists can accept that a justified belief can sometimes be false. However the details work out, this would be a more externalist way in which the notion can be biased.

There are also other perspectives one can take on concepts, which imply different approaches to loadedness. For example, a non-inferentialist account can be gleaned from Goldman’s reliabilism, in both its “normal worlds” phase (1986) and the “folkways” phase (1993). In the earlier phase, our assumptions determine what counts as a “normal world,” and this includes the assumption that no massive deception is going on. This in turn determines which beliefs are justified: those that would be reliable in a normal world (1986, pp. 107–108). In Goldman’s later phase, our assumptions about which of our processes are reliable directly determine which beliefs are deemed justified (1993, p. 160). Either way, the assumption’s determination of the concept’s extension provides an alternative account of how the concept is loaded with a bias, or the “chauvinism” of justification towards this being a normal, rather than a deceptive, world (108).Footnote 19

Goldman (1986, p. 108) highlights what I call the ‘loadedness’ of justification by considering the analogy with cats (though he does not use the term ‘loaded’), which he attributes to Unger (1984), Putnam (1962) and Kripke (1980). If we discover that the things we’ve called ‘cats’ are (and have been) internally robotic, then, according to Goldman and others, we should conclude that there are no cats. For, whatever else cats are found to be, they could not be robotic; our belief that the things we call cats are organic and not robotic helps to determine what would count as a cat. In that sense, cat is loaded with the assumption that the things we usually call ‘cats’ are animals. As Goldman puts it, “What we believe about the things we call ‘cats’ determines the meaning.” (108).

But, granting that this is so, what is the appropriate analogy to draw with justification? One idea is that what we believe about the beliefs we call ‘justified’—that many of them are perceptual beliefs and are (all else equal) likely true—determines what would count as ‘justified’. In that sense, justified is loaded with the assumption that perceptual beliefs are likely to be true, or ~sk. Call this ‘the first version’ of the idea: a world in which we are massively deceived is a world in which there is no such thing as justification, just as a world of cat-robots is a world in which there is no such thing as a cat. However, according to Goldman, the “chauvinism” of justification has the opposite consequence. He suggests that, since it is built into justification that we are in a normal world, beliefs are justified if they would be reliably formed in a normal world, regardless of whether the actual world is normal. Call this the ‘second version’ of the idea: we assume that the actual world is normal, and hence beliefs that would be reliably formed in such worlds count as justified.

Though he doesn’t recognize this in his discussion, the situation with justification, according to his, or the second, version of the idea, is quite different from the situation with cats. Goldman endorses the view that a world in which our assumption about cats is false is a world without cats. But a world in which our assumption about justified beliefs is false is still a world that contains justified beliefs, on Goldman’s preferred, second version of the idea. Since I agree with Goldman’s intuition about the cats, I find the first version more compelling than Goldman’s version. But they are both options for developing the idea of loadedness. And, at any rate, by noticing the difference between the first and second versions, we can appreciate how different views about meaning can have important consequences for our understanding of epistemic justification.

These accounts of the loadedness of justification resemble Strawson’s idea about induction. Recall that, on Strawson’s view, it is analytic that beliefs about the unobserved based (in a certain way) on observed regularities, or inductive inference, are (prima facie) justified (Strawson 1952, pp. 256–257). According to the loadedness of perceptual justification, it is analytic that

-

(a)

perceptual beliefs are prima facie justified, and

-

(b)

such justified beliefs are likely to be true (absent defeaters).

(a) resembles Strawson’s main claim almost exactly. Recall that, in order to engage with skeptical worries directly, an account must posit some epistemic justification, which is, by definition, a positive status of faring well with respect to the relevant belief’s own truth. (b) should be regarded in that light, as guaranteeing that the justification at issue has the right connection with the truth. Is it philosophically problematic that (a) and (b) are analytic, and would the resulting view afford us a satisfying solution to the skeptical problem anyway? Before addressing these questions, I will offer some clarifications and raise some issues, and, in the next section, explain how the loadedness of justification can explain why the paradox, (1)–(3), arises.

Here are two clarifications. First, judging that a belief is justified is not the same as judging that it is justified if we are not deceived. The view here is that perceptual beliefs simply count as justified (absent defeaters) and therefore likely to be true. Why? Because that’s how the notion of justification works; it has built-into it a bias in favor of ~sk.

Second, the type of justification under discussion must be restricted. I will be focusing exclusively on perceptual justification, because it is the skeptical problem involving sk that is at issue here. While I suggest that when you judge that your perceptual belief is justified, you thereby make a starting assumption that ~sk, I grant that you do not assume this when you judge that you are justified in believing that you exist, or that 2 + 2 = 4. I claim only that perceptual justification is loaded with the starting assumption that ~sk.

With these clarifications in mind, I can now raise some issues. Does it follow that our beliefs would be justified, and therefore likely, even if we were, in fact, massively deceived? What happens to the extension of justification if the assumption with which it is loaded is false, or if it assumes that something false is likely? Different versions of loadedness may suggest different answers to this question (and hence they suggest different approaches to the “new evil demon” question, or the question of the status of the BIV’s perceptual beliefs), as we saw by considering the two versions of Goldman’s idea. I will set this issue aside, since I am not arguing for any particular way of explaining how justification is loaded. A more thorough development of justification as a loaded notion would require extensive discussion of this point. Here, I have space only to argue that the general idea has explanatory power and is defensible.

Another issue arises when we consider non-perceptual justification. One might object that the notion of perceptual justification seems to be the same notion as, say, a priori justification, so that focusing exclusively on perceptual justification, and the bias towards ~sk, seems artificial. Isn’t there a more unified, general notion of justification of which perceptual justification is just one sort, and is such a notion consistent with the account offered here?

A more general notion of justification is indeed consistent with the account of perceptual justification offered here. Here are two ways in which the account could be supplemented to generalize it.

First, the kinds of justification that don’t seem loaded with a bias towards ~sk—e.g. the kind involved in the cogito and mathematical judgments—still imply the same thing as perceptual justification, namely likelihood and goodness (or positive evaluation) of the justified belief. They are for that reason naturally grouped together in our (pre-theoretical) thinking, and we may regard all notions which apply to beliefs and imply likelihood and goodness as sub-species of a general notion of justification. Justification in general, then, is a notion that applies to beliefs and implies likelihood and goodness (of the belief). There are different “kinds” of justification only in the sense that what makes justification loaded with respect to some particular question is its bias towards some particular assumption, and this is a function of the various application conditions.

But insofar as the implications of justification are potentially controversial, this is perhaps not an ideal response to the worry about generalizing the notion of justification. A more decisive, second response is as follows. We can, consistently with everything above about the loadedness of perceptual justification, broaden the assumption of justification in such a way that there is only one, fully general assumption with which the notion is loaded. This more general assumption would entail that ~sk (or that we are justified believing ~sk, depending on how loadedness is detailed), so that all of the features of loadedness appealed to in this paper still apply. Though specifying exactly what this more general assumption is would take us too far afield, here is a brief sketch. The assumption might be that one can, given one’s current cognitive situation as one understands it, get at the truth by using one’s faculties. It would follow that, absent any other relevant information, one is not massively deceived, or ~sk. That is, it follows that, when it comes to empirical topics such as whether one has hands, one is not perceptually deceived. This would have to be refined, surely. One faculty sometimes corrects another, for example. But, such complexities aside, it is plausible that I do assume that I can get at the likely truth through proper use of my faculties (including my logical and “insight” faculties) while concluding that I am justified in believing that I exist, for example, or that 2 + 2 = 4. Thus, a general notion of justification could be seen to be loaded with a more general assumption, which entails ~sk. Here, though, we are focusing on ~sk, since we are concerned with skepticism about the external world.

3 Loadedness explains why the paradox arises

Recall that argument (1)–(3) constitutes a paradox because the conclusion of the skeptical argument, (3), is unacceptable, and (1) and (2) both seem plausible. Most epistemologists take (2) for granted, so for them explaining why the paradox arises requires explaining why (1) seems plausible and why (3) is unacceptable.

In order to explain why (1) is plausible, one must account for the difficulty of explaining how we could have justification to believe ~sk. If justification is loaded with a bias towards ~sk, then any judgment that some proposition is justified requires the starting assumption that ~sk. But, in the case of the judgment that there is justification to believe ~sk, the notion of justification is being applied to that starting assumption. This loopy quality has the flavor of a paradox, since we seem to need to use a notion in order to secure that very notion’s bias, or starting assumption. How can you get justified in believing something that the very notion of justification assumes?

The appeal of (1), then, is that Justification’s bias toward ~sk is what’s doing the work to get you justified in believing ~sk, and that seems contrary to how one can get justified. Even if you appeal to an empirical premise, say, that you have hands, in order to infer ~sk, you regard that premise as justified, and thus worthy of use in an argument, only in virtue of the fact that the notion of justification is already biased towards ~sk—otherwise, why regard your experiences as evidence, or justification, for the proposition that you have hands?Footnote 20 And that, it seems, is no way to become justified in concluding that ~sk, since the deck was stacked in favor of ~sk all along.Footnote 21 ~Sk is not just another proposition, and it doesn’t just happen to be difficult to explain our justification for believing it. Justification itself marks a special place for ~sk, and this explains the difficulty of establishing our justification for ~sk. Loadedness, then, makes sense of the apparent inescapability of (1). This is precisely the challenge that most epistemologists take on when considering the paradox.

To be sure, any of the steps taken above to explain why the paradox arises can be questioned and ultimately rejected. But they seem, on the face of it, compelling, and that is why (1) seems compelling. Likewise, some philosophers hold that there are some good a priori arguments or considerations in favor of ~sk, and this would make a case against (1).Footnote 22 But, if such a priori considerations aren’t obvious—and they don’t seem to most of us to be obvious—then the existence of such heroic a priori solutions to the paradox is compatible with the forgoing explanation of why (1) seems true in the first place. To be clear: it is compatible with the view defended here that (1) is false (or that (2) is false). What I’ve explained here is why (1) appears true. We may well have justification to believe ~sk, once the details of justification are sorted out.

Recall that, in order to explain why the paradox arises, it is also necessary to explain why (3) seems unacceptable. Loadedness can explain this. The negation of (3), absent any evidence that sk is true, is something like a conceptual truth. Perceptual beliefs just count as prima facie justified. So long as we know that we have some experience as of p, we know that our notion of justification (prima facie) applies to belief that p. Since we’re sure that we do have some such experiences, the idea that we lack justification to believe p, in the absence of any specific defeaters, is almost unthinkable. This is why, when one is confronted with (1)–(3), it only remains to see which of (1) or (2) is false, and why. This is exactly what the vast majority of the literature on the paradox does. The loadedness of justification explains this well. To be clear, then, on this account, if one rejects the idea that a perceptual belief is even prima facie justified, then one is either misusing our notion of justification, or refusing to use it at all (as one might with boche). How else can you have an experience as of p, believe that p on that basis in the normal way, lack defeating evidence, and yet deny that the resulting perceptual belief is justified?

The view here is that justification is loaded with a bias towards ~sk, in virtue of the way the notion works, or given what it means to be justified. But, this does not mean that those who disagree about the specific conditions of justification lack an understanding of our very concept of justification. The only one lacking understanding of what ‘justified’ means is one who accepts that we lack even prima facie perceptual justification. That one of the premises of the paradox is false follows from what it means to be justified. But which one and why, and how this is consistent with our intuitions is not settled by the view defended here. On the contrary, as we will see below, the theory on offer here explains why the paradox arises, and why the work of anti-skeptical epistemologists is so difficult. It is only the claim that our perceptual beliefs are justified (somehow) that is not up for debate for those who understand justification, on this theory.

This explanation for why we regard (1)–(3) as a paradox extends to paradoxes involving scenarios or propositions that are entailed by the assumption that we are not massively deceived. This includes the proposition that our senses are generally reliable, that we are not dreaming, that we are not dreaming with socks on, that nature is uniform, and so on. For, if some proposition is entailed by the starting assumption of justification, it is just as difficult to see how we can gain justification to believe it by using that very notion (and lacking any further evidence).

4 Objections to loadedness: analyticity and arbitrariness

So far, I’ve introduced the idea that justification has a built-in, or “analytic” bias towards ~sk, and that this explains why the paradox involving our justification to believe ~sk arises.Footnote 23 I’ve also noted that solving the paradox requires specifying some conditions for justification which are compatible with the falsity of (1) or (2), and explaining away the initial appeal of (1) or (2). Such solutions are clearly consistent with the loadedness of justification. But now one might worry that, by building in a bias towards ~sk, we have thereby overstepped what a theory of justification can plausibly show, and trivialized the problem of skepticism. Similar worries were raised about Strawson’s view as a solution to the problem of induction. In this section I consider the most important of these objections as applied to the loadedness of perceptual justification.

The first objection is that the claim that (a) and (b) are analytic is implausible, since it implies that something contingent is a matter of meaning. Recall that, according to the loadedness of perceptual justification, it is analytic that

-

(a)

perceptual beliefs are prima facie justified, and

-

(b)

such justified beliefs are likely to be true (absent defeaters).

One might think this is a problem because (a) and (b) together imply that perceptual beliefs are likely to be true, or ~sk, and that sounds like a contingent claim. Note that this is a contingent claim only if “likely” in (b) is interpreted objectively, so that, taken together, (a) and (b) imply that perceptual beliefs are objectively likely to be true. (We have seen above that such an interpretation is optional.) So, let us construe it in this, objective way for the purpose of considering this objection. Even granting this interpretation, though, the loadedness of justification does not imply that one can come to know or derive the conclusion that perceptual beliefs are likely true, a priori or solely by consulting or observing one’s concepts. The sense in which one can “discover” that ~sk is implicated by justification needs only to be clarified to show this: you can discover that the way you employ justification implies ~sk, but that is not the same thing as discovering some evidence that ~sk.

On the version of the loadedness currently being considered, the notion of justification is loaded with a starting assumption that sk is true, so that perceptual beliefs are (all else equal) objectively likely. In other words, it follows from how justification works that perceptual beliefs are likely to be true. In just the same way, it follows from how boche works that all Germans are cruel, and it follows from how Newtonian mass works that things that resist acceleration under force attract other things that resist acceleration under force. This is problematic only if it follows that one can come to know such contingent truths a priori. But this is not so in any of these cases. To see why, consider, first, that it remains an a priori possibility that ‘justification’, ‘boche’, ‘Newtonian mass’, are empty, or defective, or incoherent (as some have argued ‘boche’ is). Showing that the skeptical argument fails, or solving the skeptical paradox, removes one argument for the conclusion that ‘justification’ is empty. But there remains, on this account, another troubling possibility: that justification is loaded with a false starting assumption, or biased towards a false proposition. To vindicate one’s use of such a loaded notion would require an independent reason to make such a starting assumption. Presumably, you cannot vindicate your use of a loaded notion by making its starting assumption, using the notion, and then inferring that its starting assumption must be correct. So, one cannot learn that ~sk—that perceptual beliefs are objectively likely to be true—a priori or by appealing to the meaning of ‘justified’.

A clarification made in the previous section is worth repeating here. I am not arguing that we cannot be justified in believing ~sk. Rather, here I am arguing that we, on the face of it, we cannot gain justification to believe ~sk merely by using a concept that is loaded with the starting assumption that ~sk. This leaves open whether we are justified by default (without ever gaining justification for it) in believing ~sk, and also whether there is some other evidence or argument for ~sk that would justify that belief. (a) and (b) are not problematically analytic. Rather, they make explicit the starting assumption, or bias loaded into justification. Being implied by a notion is one thing, being knowable by inference from a mere use of the notion is another.

Although the forgoing should assuage the worry that the analyticity of (a) and (b) is problematic, one might still wonder how ~sk can be part of, or follow from, some notion. One way to arrive at a theory of justification by a priori reflection is to think about what we mean (or perhaps what we ought to mean) by ‘justified’. If justification is a loaded notion, it is not mysterious how reflecting on the notion results in the conclusion that (absent contrary evidence) sk is true. It is obviously possible to discover your assumption from the armchair, and to see that this assumption is “built in” to a notion you are using.Footnote 24 Still, it is not a priori, or a matter of meaning, whether the assumption is true. Realizing that justification is loaded is just realizing that we’ve been assuming something all along, and that this assumption has influenced the way we’ve constructed our notions.

At this point, having seen a way out of the original worry, one might worry that the loadedness of justification doesn’t solve any skeptical problem, since it doesn’t allow us to infer whether sk is true, or objectively likely to be true. Rather, all it does is show us how we use some term. As Salmon (1957) famously put it, in objecting to Strawson’s analytic solution to the problem of induction: “If you use inductive procedures you can call yourself ‘reasonable’—and isn’t that nice.” Another, more common way of putting the objection is in terms of relativism: if ~sk is built into our notion of justification, and if we still have no way of determining whether ~sk is true, then why use this, rather than some other notion of justification that is loaded with some other starting assumption instead? This objection has been made by Bonjour (1998), Salmon (1957), Skyrms (1975), Lange (2008), and others. In Bonjour’s version (1998, p. 199), we would have nothing to say in response to a group of people who loaded their notion of justification with the reliability of some religious text. Whatever Strawson can say in defense of his notion, the religious community can say it in defense of its own notion: “This is what we count as justified!” It seems to apply to the view presented here, too: whatever we can say in defense of our loaded notion of justification, the religious community has that defense too.

However, this objection conflates different skeptical problems. I think the reason that this objection has been so widely accepted is that it is sound with respect to its target, but its proper target is narrower than philosophers have realized. What the objection shows is that if one wants to vindicate one’s use of a loaded notion, one cannot do so merely by making claims invoking that notion. However, vindicating our use of justification is a distinct project from the project of solving the paradox. The conditions for justification, which are often appealed to in different solutions to the paradox, betray a bias towards ~sk built into our notion. Those conditions imply that some premise of the paradox is false. But those a priori knowable conditions themselves, as conditions of a loaded notion, won’t help to vindicate our use of this, rather than some other, notion, as the objection illustrates. That a theory of the conditions of justification cannot itself vindicate our use of justification does not show that any such theory is false. Rather, it just shows the limits of what a theory of the conditions of justification can do. It cannot show that some contingent claim such as ~sk is true, and it cannot vindicate our use of this, rather than some alternative, notion. But it may well still be true, and it may well still afford us a solution to the paradox by implying that some premise of the paradox is false. That is, such a theory of justification can remove one important reason one might have had for thinking that justification is empty or defective: the paradox.

The forgoing response to the objection sets up the task for the next section, which is to distinguish different kinds of skeptical challenge in light of the loadedness of justification, and to explain what vindicating our use of the notion would require. But note that the response is not entirely novel, and nor is it a special burden of the view defended here. Pryor (2000) famously distinguished two different anti-skeptical projects: the modest one is to say which premise of the paradox is false appealing only to claims that we, the non-skeptics, accept. The ambitious one is to do the same using only claims that the skeptic will accept. He, and many others, aspire only to the modest project, and therefore should not be worried by the relativism objection. We accept ~sk, and this explains why we use justification, and the conditions of justification account for which premise in the paradox is false. The objector’s religious community can also say, “we aspire only to the modest anti-skeptical project with respect to your religious skepticism,” in response to a challenge to their practice. Most epistemologists, whether they know it or not, accept that theories of justification cannot do more than solve the paradox: the vast majority of anti-skeptical papers claim to solve the paradox without citing any evidence that ~sk is actually true.Footnote 25 Rather, such papers are concerned with conceptual, a priori matters, which is what is required to solve the paradox. Next, I will propose a more radical distinction between anti-skeptical projects, beyond Pryor’s dialectical insight.

5 What is “the” problem of skepticism?

It is a metaphysical question whether we are massively deceived—it is different in kind from the question of whether or how we are justified in believing that we are not massively deceived. If it seems inappropriate, or unsatisfying, to use our notion of justification in the absence of meeting this metaphysical challenge, then, in that sense, Bonjour and others’ relativist challenge is “deeper” than the one posed by the paradox. The paradox itself can, at least in principle, be addressed by sorting out the way the notion of justification works. We need only come up with a satisfactory account of the notion on which one of the skeptical premises are false. But this involves employing the notion of justification, whose legitimacy, according to the deeper skeptical challenge, is in question. The latter, metaphysical skeptical challenge is to figure out how we are causally connected to the world, not how our notion of justification works or whether its use gives rise to contradictions as the paradox threatens to show. It is an empirical question.

All any (non-skeptical) theorist of justification can say is, “we can call our perceptual beliefs ‘justified’, and isn’t that nice?” But the fact that things are “nice” in that way can be significant, if the aim is to refute the idea that things are not “nice” in that way, which is what the paradox threatens by appealing to our notion of justification in defense of premises that lead to the conclusion that no belief is justified. So, if the paradox is what we are interested in, then the idea that justification is a loaded notion has much to offer. It explains why the paradox arises and gives a framework for providing the details of the precise conditions of justification such that some premise of the paradox is false. If, instead, it is the metaphysical skeptical question, whether ~sk, that interests us, then loadedness does nothing to help. But neither does any a priori theory of justification.

It is tempting to inquire how important the metaphysical question is. On one level, it is just another question about the world. But it is among the philosophically rich questions, like “Is there a God?” or “Why is there anything at all?” These pose specific questions about what is out there, but they are especially interesting because, presumably, it matters to us whether there is a God, or why there is anything at all. Arguably, it matters to us whether we are massively deceived, because much of what we care about is discovered through our senses. But, from an epistemological perspective, why does it matter whether ~sk is true?

One way the question whether ~sk can be seen as important to epistemology is that it can be understood as an attempt to answer the question: Why care about whether our beliefs are justified? For, our notion of justification is loaded with a bias, or starting assumption, that ~sk; clearly we should care about justification only if it is loaded in the right direction. This is similar to the question “Why be moral?” or “Why should I care if my actions are right?” Notice that this is different from asking “Is anything immoral?” or “Is anything wrong?” If the principles of morality deem murder to be wrong, then that answers the latter questions. But the former questions are deeper in the sense that they inquire about the significance of those principles. Likewise, the question “Is any belief justified?” is, given loadedness, rather easy: “Yes, perceptual ones, for example, are typically justified; that’s how ‘justified’ works.” But the question “Why care about which beliefs are justified?” or “Why care about justification?” is harder, and requires considering the biases or starting assumptions of justification.

Trying to determine whether we are massively deceived is not the only way to address this sort of question. The question is “Why use, or care about,” some notion. A rationale for accepting a notion is not the same thing as a justification for believing a proposition. That is, it isn’t obvious that the answer to the “why” question must come in the form of evidence or proof, or some epistemic justification for believing, that we are not massively deceived. It may come in the form of some other, non-epistemic considerations in favor of accepting that proposition, or using a notion that assumes it.Footnote 26 If there is some non-epistemic but strong reason to use justification, loaded as it is with ~sk, then that seems to answer the questions “Why use the concept” and “Why care about the concept?” Perhaps these non-epistemic reasons are practical, or perhaps they stem from certain aspects of human nature. In any case, the “why care” question is not equivalent to the metaphysical question, since it doesn’t necessarily demand proof, or evidence, or epistemic justification, to believe ~sk. And the paradox is certainly different from either one of those questions, since it can be answered by appeal to our notion of justification and how it works.

To sum up, if justification is loaded, then the question of whether our perceptual beliefs are prima facie justified is relatively easy: of course they are, since the notion of justification guarantees it. Questions about the credentials of our notion of justification seem much harder, but they are not necessarily epistemological questions. They concern why we should use or care about our notion rather than another, or else they concern metaphysical (perhaps empirical) facts about our world and how we are connected to it. I leave it an open question whether such questions deserve to be regarded as “the real” skeptical problems; they are certainly distinct from the challenge of solving the paradox.

Notes

The term ‘notion’ is intended to be synonymous with ‘concept’ while carrying a salient implication—especially in the context of a discussion of skepticism—that the thing of which we have a notion may not actually exist. See Merriam Webster’s Dictionary of Synonyms for an explanation of the subtle differences between ‘notion’, ‘concept’, and some other related terms.

I use italics for emphasis, to introduce a new term, and, in other cases, such as this, to denote the notion expressed by the italicized term.

Alston (1993) surveys many of these difficulties.

For example, Avnur (2012).

For example, Pryor (2004).

There is another, Wittgenstein-inspired approach to the paradox, recently termed ‘hinge epistemology” (see Coliva and Moyal-Sharrock 2016; Avnur 2018 for some discussions), according to which propositions that are relevantly like ~sk (“hinge” propositions) get special treatment by our general epistemic principles. On this view, the way we use the notion of justification implies that it cannot apply to ~sk. It is not clear to me how exactly this relates to the claim, defended here, that justification favors ~sk. One might think that hinge epistemology does not posit a bias in favor of ~sk (thanks to Annalisa Coliva for helpful discussion here). Rather, on such views, it makes no sense at all to assess whether or not belief that ~sk is justified; ~sk is entirely left out of the picture. If so, then the theory developed here is an alternative to a hinge epistemological, Wittgenstein-inspired approach to justification. Two important developments of the “hinge” approach to the paradox are Coliva (2015) and Pritchard (2016). I myself have defended this kind of view in Avnur (2012). One advantage of developing the loadedness approach I favor here is that most other theories of justification can be seen as versions of loadedness, but not of hinge epistemology. So, loadedness should have broader appeal.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pressing this point.

Cohen cites Strawson in a footnote there, but doesn’t explicitly detail the connection.

See McCullagh (2011) for an alternative version of inferentialism, which does not require endorsement of any inference as a necessary condition on concept possession.

Of course, loading the notion of justification, even in this externalist way, does not make our perceptual beliefs true or objectively probably true. In a world in which sk is true, this externalist sort of loaded notion will have no extension, presumably. So, such a strategy does not answer the question whether sk is true, or whether our perceptual beliefs are generally or probably true. Rather, it shows that our notion of justification does not commit us to a paradox or contradiction, which is what the skeptical paradox challenges us to do. Below, in Sects. 4 and 5, I address the relation of this challenge to the challenge of establishing whether, in fact, our perceptual beliefs are objectively likely to be true.

For example, Silins (2005) holds that, while our perceptual justification is immediate, we also have default justification to believe ~sk.

Thanks to Dustin Locke for helpful discussion on this point.

What follows is a brief discussion of Goldman’s view, as an example of a theory according to which justification is loaded. The idea that what we believe about things determines the meaning of term we use to refer to them needs more discussion than can be offered here for a full defense. A major issue is how to decide which beliefs about a thing determine the meaning of the relevant term. Admittedly, on the way of understanding loadedness under discussion, this will be a major commitment and so the details will be important. For one recent approach to this question, applies to the problem of free will, see Turner (2013, section 3) on ‘conceptions’.

See Wright (2007) for discussion of the distinction between having and claiming justification, or warrant, for a belief in the context of Moore’s “proof” of an external world.

This is often discussed in terms of “transmission-failure” or “epistemic circularity,” which divides dogmatists (or “liberals”) and conservatives. Wright (2002) and Pryor (2004) are the classic examples of conservative and liberal views on transmission failure, respectively. Wright’s (2004) version of the view concerns the broader notions of “acceptance” and “trust,” instead of belief, but he is widely interpreted to hold that the relevant beliefs have a default warrant. There is also a third option, sometimes called ‘Moderatism’ (a term coined by Coliva 2012) which is defended in Avnur (2012) and Coliva (2012). This involves rejecting (2) in the paradox. The idea that justification is a loaded notion is neutral on all of these debates, and yet it still can explain why the inference from a simple perceptual premise to ~sk seems to fail (even if on reflection, we decide that it does not fail).

One might think that, since justification is loaded with a bias towards ~sk, it is the wrong notion to use when evaluating the skeptical argument, which crucially involves ~sk. Why do epistemologists use such a notion, given their aims? Answer: the argument concerns justification. Appealing to our loaded notion of justification is not an option that epistemologists choose when confronting the paradox. Rather, the paradox, or skeptical argument, is about our notion of justification, which is loaded with a bias towards ~sk.

This is exactly what happens when Goldman and Cohen theorize, as we’ve seen above.

Above, I noted the most obvious exceptions to this, namely those who present an a priori argument for ~sk. They do not attempt to solve the paradox by appealing to a theory of justification. Many, though, are not in this camp. This includes some externalists, such as Goldman (1986, 1993) since even on that account, what counts as a “normal world,” or what assumptions we make about which faculties are reliable, while knowable from the armchair, does not constitute an argument that ~sk is true. This point is made by Stich (1990, p. 95). Beyond discussion of Goldman, Stitch call theories of justification as I am understanding them “analytic epistemology,” and his discussion is similar to this one in some ways, though the aim is different (Stitch 1990, pp. 91–93).

Alston (1993) reaches a similar conclusion.

References

Alston, W. P. (1986). Epistemic circularity. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 47(1), 1–30.

Alston, W. P. (1993). The reliability of sense perception. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Alston, W. (2005). Beyond justification: Dimensions of epistemic evaluation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Avnur, Y. (2012). Closure reconsidered. Philosophers’ Imprint, 12(9), 1–16.

Avnur, Y. (2018). Review of Annalisa Coliva, Danièle Moyal-Sharrock: Hinge epistemology. Philosophical Investigations, 41(3), 366–370.

Bergmann, M. (2000). Externalism and skepticism. Philosophical Review, 109(2), 159–194.

BonJour, L. (1998). Defense of pure reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BonJour, L., & Sosa, E. (2003). Epistemic justification: Internalism vs. externalism, foundations vs. virtues. Hoboken: Blackwell Pub.

Brandom, R. (2000). Articulating reasons: An introduction to inferentialism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Brueckner, A. (1994). The structure of the skeptical argument. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 54(4), 827–835.

Cohen, S. (1998). Two kinds of skeptical argument. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 58(1), 143–159.

Cohen, S. (2010). Bootstrapping, defeasible reasoning, and a priori justification. Philosophical Perspectives, 24(1), 141–159.

Cohen, S. (2016). Theorizing about the epistemic. Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, 59(7–8), 839–857.

Coliva, A. (2012). Moore’s Proof, liberals, and conservatives: Is there a (Wittgensteinian) third way? In C. Wright & A. Coliva (Eds.), Mind, meaning, and knowledge: Themes from the philosophy of Crispin Wright. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coliva, A. (2015). Extended rationality: A hinge epistemology. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Coliva, A., & Moyal-Sharrock, D. (Eds.). (2016). Hinge epistemology. Leiden: Brill.

Descartes, R. (1990). Descartes: Selected philosophical writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dogramaci, S. (2012). Reverse engineering epistemic evaluations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 84(3), 513–530.

Dummett, M. (1973). Frege: Philosophy of language. London: Duckworth.

Fumerton, R. (2005). The challenge of refuting skepticism. In S. Matthias & S. Ernest (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 85–97). Hoboken: Blackwell.

Goldman, A. I. (1986). Epistemology and cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goldman, A. I. (1993). Epistemic folkways and scientific epistemology. Philosophical Issues, 3, 271–285.

Kripke, S. A. (1980). Naming and necessity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lange, M. (2008). Hume and the problem of induction. In D. Gabbay, S. Hartmann, & J. Woods (Eds.), Handbook of the history and philosophy of logic, vol. 10: Inductive logic. Hoboken: Elsevier. (forthcoming).

Lewis, D. (1972). How to define theoretical terms. Journal of Philosophy, 67, 427–446.

McCullagh, M. (2011). How to use a concept you reject. Philosophical Quarterly, 61(243), 293–319.

Peacocke, C. (2004). The realm of reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Plantinga, A. (1993). Warrant: The current debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pritchard, D. (2005). The structure of sceptical arguments. Philosophical Quarterly, 55(218), 37–52.

Pritchard, D. (2016). Epistemic angst: Radical skepticism and the groundlessness of our believing. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pryor, J. (2000). The skeptic and the dogmatist. Noûs, 34(4), 517–549.

Pryor, J. (2004). What’s wrong with Moore’s argument? Philosophical Issues, 14(1), 349–378.

Putnam, H. (1962). It ain’t necessarily so. Journal of Philosophy, 59(22), 658–671.

Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, truth, and history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramsey, F. P. (1929). Theories. In R. B. Braithwaite (Ed.), Foundations of mathematics (1931). London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Salmon, W. C. (1957). Should we attempt to justify induction? Philosophical Studies, 8(3), 33–48.

Schafer, K. (2014). Doxastic planning and epistemic internalism. Synthese, 191(12), 2571–2591.

Schiffer, S. (2004). Skepticism and the vagaries of justified belief. Philosophical Studies, 119(1–2), 161–184.

Silins, N. (2005). Deception and evidence. Philosophical Perspectives, 19(1), 375–404.

Skyrms, B. (1975). Choice and chance: An introduction to inductive logic. Co: Dickenson Pub.

Stitch, S. (1990). The fragmentation of reason: Preface to a pragmatic theory of cognitive evaluation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Strawson, P. F. (1952). Introduction to logical theory. New York: Wiley.

Turner, J. (2013). (Metasemantically) Securing free will. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 91(2), 295–310.

Unger, P. K. (1984). Philosophical relativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vogel, J. (2004). Skeptical arguments. Philosophical Issues, 14(1), 426–455.

Vogel, J. (2005). The refutation of skepticism. In S. Matthias & S. Ernest (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 72–84). Hoboken: Blackwell.

White, R. (2006). Problems for dogmatism. Philosophical Studies, 131(3), 525–557.

Wright, C. (2002). (Anti-)sceptics simple and subtle: G. E. Moore and John McDowell. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 65(2), 330–348.

Wright, C. (2004). Warrant for nothing (and foundations for free)? Aristotelian Society Supplementary, 78(1), 167–212.

Wright, C. (2007). The perils of dogmatism. In S. Nuccetelli & G. Seay (Eds.), Themes from G. E Moore: New essays in epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wright, C. (2014). On epistemic entitlement (II): Welfare state epistemology. In D. Dodd & E. Zardini (Eds.), Scepticism and perceptual justification (pp. 213–247). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

For comments and discussion over many years on various versions of this paper, I would like to thank David James Barnett, Paul Boghossian, Annalisa Coliva, Kit Fine, Dustin Locke, James Pryor, Karl Schafer, Stephen Schiffer, Dion Scott-Kakures, and Rivka Weinberg, as well as other participants at a Skepticism conference at UC Irvine, the New Perspectives on External World Scepticism conference at the Munich Centre for Mathematical Philosophy, the European Epistemology Network Conference in Bologna, Italy, a seminar at New York University, and a Work in Progress seminar at the Claremont Colleges.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avnur, Y. Justification as a loaded notion. Synthese 198, 4897–4916 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02375-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02375-7