Abstract

The standard view in philosophy treats pains as phenomenally conscious mental states. This view has a number of corollaries, including that it is generally taken to rule out the existence of unfelt pains. The primary argument in support of the standard view is that it supposedly corresponds with the commonsense conception of pain. In this paper, we challenge this doctrine about the commonsense conception of pain, and with it the support offered for the standard view, by presenting the results of a series of new empirical studies that indicate that lay people not only tend to believe that unfelt pains are possible, but actually, quite common.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The philosophical consensus holds that pains are mental states that are necessarily conscious. As such, it is generally held that there can be no unfelt pains. This standard view is thought to correspond with the commonsense conception of pain, and this supposed correspondence is often noted as the main argument in support of the standard view. Despite this, we will report and discuss the results of 17 new empirical studies indicating that English speakers by and large hold that unfelt pains are possible.

We begin in Sect. 1 by discussing the standard view of pain and the support that is offered for it. We then consider two alternatives to the standard view that allow for the existence of unfelt pains: in Sect. 2 we look at the view that while pains are mental states, they need not be phenomenally conscious mental states; in Sect. 3 we lay out a more radical alternative—that pains are not mental states at all, but bodily states. In the remainder of the paper we argue that contrary to what advocates of the standard view have supposed, native English-speakers happily endorse the occurrence of unfelt pains. More tentatively, we argue that this reflects that the majority hold a bodily conception of pain. After discussing the results of previous empirical work on the commonsense conception of pain in Sect. 4, we present the results of a series of new empirical studies surveying over 1600 native English-speakers in Sect. 5. Finally, in Sect. 6, we discuss the implications of these results for philosophical accounts of pain.

1 Pains as conscious mental states

Almost all philosophers writing about pains treat them as being mental states. Within this camp, most hold the standard view that pains are necessarily conscious mental states.Footnote 1 On this view, the existence of a pain depends on its being felt, such that there can be no unfelt pains. The standard view of pain has a venerable history in philosophy. Famously, Reid (1785: 1.1.12) wrote:

Pain of every kind is an uneasy sensation. When I am pained, I cannot say that the pain I feel is one thing, and that my feeling it is another thing. They are one and the same thing, and cannot be disjoined, even in imagination. Pain, when it is not felt, has no existence.

And many more recent authors have echoed Reid’s sentiment. To give but a few examples, Kripke (1980: p. 152) writes that pain “is not picked out by one of its accidental properties; rather it is picked out by the property of being pain itself, by its immediate phenomenological quality.” Daniel Dennett claims that “Pains are feelings, felt by people, and they hurt.” (1986: p. 65). More recently, Aydede (2006: p. 4) has pushed the standard view:

Pains seem also to be subjective in the sense that their existence seems to depend on feeling them. Indeed, there is an air of paradox when someone talks about unfelt pains. One is naturally tempted to say that if a pain is not being felt by its owner then it does not exist.

And similarly from Hill (2009: pp. 169–170):

Our thought and talk about bodily sensations presupposes that the appearance of a bodily sensation is linked indissolubly to the sensation itself. This is true, in particular, of our thought and talk about pain.

What we find across these authors is that pains are treated as being conscious mental states with a particular type of phenomenal character. As such, these authors rule out the possibility of there being unfelt pains.

Should we accept the standard view of pains put forward by philosophers like Reid, Kripke, Aydede, and Hill? And, more specifically, should we accept that there can be no unfelt pains? This requires considering the support that is on offer for this view. What we find when we look more closely is that the claim that there can be no unfelt pains is primarily supported via two related claims: It is asserted that this is part of the ordinary or commonsense conception of pain, and it is asserted that it is obvious or self-evident from one’s own experience with pain.

Aydede and Hill are especially clear in offering the first line of support. For instance, Aydede argues that “there are two main threads in the commonsense conception of pain that pull in opposite directions” (2006: p. 2). The first thread treats pains as being located in body parts and is manifested in ordinary expressions like “I have a sharp pain in the back of my right hand” and “my wisdom tooth aches intensely” (2006: pp. 2–3). In contrast, the second thread corresponds with the standard view, treating pains as experiences. And it is this second thread that Aydede considers to be “our ordinary or dominant concept of pain” (2006: p. 5).Footnote 2 Accordingly, the possibility of pain hallucinations, unfelt pains, and, more generally, an appearance-reality distinction for pains, is dismissed by Aydede based on our common-sense understanding of pain. He is particularly clear about this when considering the following thought experiment about the possible existence of unfelt pains:

Suppose that we do in fact attribute a physical condition, call it PC, when we attribute pain to body parts, and that PC is the perceptual object of such experiences. So, for instance, John’s current excruciating experience (call this E) is caused by and represents a physical condition in his right thigh and our ordinary concept of pain applies in the first instance to this condition in his thigh. From this it would follow that… John would have pain if he had PC but no E (as would be the case, for instance, if he had taken absolutely effective painkillers or his thigh had been anesthetized).

But (this statement is) intuitively incorrect. (It appears) to clash with our ordinary or dominant concept of pain, which seems to track the experience rather than the physical condition. (2006: 4–5)

In this passage Aydede supports the claim that our ordinary concept of pain primarily corresponds with the standard view by appealing to his intuition about the painkiller thought experiment he gives, assuming that his intuition is representative of those of ordinary people. In fact, Aydede seems to be very certain that his intuition is representative as he asserts that it “seems to be a truism” that “pain is a subjective experience” (2006: p. 5). We will return to thought experiments involving painkillers in Sect. 5.2.

A similar appeal to intuitions about thought experiments is found in Hill. In the passage quoted above, he suggested that the standard view follows from “our thought and talk about pain.” Hill then proceeds to suggest both lines of support noted above: he argues that we think of principles that follow from the standard view as “holding either because of deep metaphysical facts about our awareness of pain, or because of the a priori structure of our concept of pain” (2009: p. 169). Like Aydede, however, Hill goes on to allow that some aspects of our ordinary use of pain language don’t correspond well with the standard view. For example, he notes that “we say that pains can wake us up,” and that this claim is naturally construed as presupposing “a picture according to which pain can exist prior to and therefore independently of awareness” (2009: p. 170). Hill counters this, however, by appealing to his intuitions about a thought experiment:

Although this picture has a certain appeal, I doubt very much that it can be said to represent a dominant strand in our commonsense conception of pain. If we were fully committed to the picture, we would be prepared to consider it epistemically possible that an injured soldier actually has a severe pain, despite his professions to the contrary, but that there is something wrong with the mechanisms in his brain that support attention, and that this is preventing the pain from penetrating the threshold of consciousness. When I have asked informants to assess the likelihood of this scenario, however, they have all been inclined to dismiss it as absurd. (2009: p. 171)

We will return to thought experiments involving injured soldiers who profess to feel no pain in Sect. 5.3.

The second line of support for the standard view is to take it to be simply obvious from one’s own experience with pain. Oftentimes when an author claims that it is in some way obvious that there can be no unfelt pains, it is unclear whether this is thought to follow from the concept of pain or from the phenomenology of pain (or both). Others are more careful, clearly distinguishing between these two lines of support. For example, Levine (2008: p. 227) pushes both, beginning with the conceptual point:

Now one way of opposing the possibility of unfelt pains is to treat the question as basically a semantic one. One might claim, plausibly to my mind, that the way we use the term “pain” makes it inappropriate to apply it in those cases where we totally fail to “feel” it, when there is no conscious awareness of it at all. David Lewis famously said that pain is essentially a feeling, and one way to interpret this claim is to treat it as a conceptual matter. It’s just a part of our concept of pain that one attributes it only when one is aware of it.

Of course, our concept could be different, as Levine realizes. And perhaps it could even be the case (although Levine does not raise the possibility) that the concept that philosophers are operating with in putting forward the standard view differs from the ordinary concept—it could be that these philosophers have learned a technical concept in the course of their studies and that this technical concept diverges in important ways from the ordinary concept.Footnote 3

Levine goes on to suggest what he takes to be a deeper line of support, however; he argues that the standard view follows from the phenomenology of pain experience:

When people intuitively resist the idea that there are unfelt pains, or when they agree with Lewis’s statement that pain is essentially a feeling, I think they have something in mind far more substantive than when it’s appropriate to apply the term “pain.” Rather, the idea is that when you contemplate that very quality of, say, a toothache, the one that fills your awareness, it does not seem at all like the kind of thing that can be instantiated in one’s tooth (or the nerve, or whatever) without one’s being aware of it. That is, it is in its very nature a feeling, a moment of consciousness, something “for the subject.” (2008: 227)

While this second line of support is distinct from the first, they are closely related. In particular, it seems that if Levine is correct about the phenomenology of pain supporting the standard view, then we should expect the ordinary conception of pain to follow suit. In fact, we might say that the phenomenological point would explain the conceptual point. Going the other way, if we were to find that the ordinary conception of pain does not correspond with the standard view, this would give us reason to reconsider the phenomenological claim: if it is in fact evident from ordinary experience with pain that there can be no unfelt pains, then we should expect that the ordinary conception of pain will rule out unfelt pains.

Alternatively, one might wonder whether the phenomenology of feeling pain really points in this direction. It might be urged that when one feels a pain it feels as if it is located somewhere in the body (although some pains feel more localized than others). Taking this phenomenological point seriously, one might conceive of pains as being qualities of bodily disturbances—that is, as something that can be “merely instantiated,” such that it might exist without being felt at a given time. We return to this bodily conception of pain in Sect. 3, after briefly considering a second type of mental state conception of pain in the next section.

2 Pains as unconscious mental states

While most philosophers working on pain have adopted the standard view discussed in the previous section, some advocates have acknowledged that there is room for disagreement. For instance, Dretske (2006: p. 59) writes:

Many people think of pain and other bodily sensations (tickles, itches, nausea) as feelings one is necessarily conscious of. Some think there can be pains one doesn’t feel, pains one is (for a certain interval) not conscious of (“I was so distracted I forgot about my headache”), but others agree with Thomas Reid and Saul Kripke that unfelt pains are like invisible rainbows: they can’t exist. If you are so distracted you aren’t aware of your headache, then, for that period of time, you are not in pain. Your head doesn’t hurt. It doesn’t ache. For these people (I’m one of them) you can’t be in pain without feeling it, and feeling it requires awareness of it.

This type of dissent is prominent amongst philosophers who believe that there are unconscious mental states that the term “pain” can be reasonably applied to, even if we typically apply it to conscious mental states. For example, David Armstrong argues:

“Are the happenings of which we are introspectively aware—such things as pains, sense-impressions, mental images, etc.—necessarily experiences, or can they exist when we are not aware of them?” I think we ought to say the latter. For suppose that we decide that pains, sense-impressions, images, etc., logically must be apprehended, the logical possibility must still be admitted of inner happenings which resemble these mental states in all respects except that of being objects of introspective awareness. For if introspective awareness and its objects are “distinct existences,” as we have argued, then it must be possible for the objects to exist when the awareness does not exist. And once we concede this, we have every reason to call such states pains, sense-impressions, etc. (1963: p. 114)

Armstrong’s argument for allowing for unfelt pains is quite different from the support we saw for the standard view in the previous section. In particular, Armstrong is not suggesting that the ordinary concept of pain allows for unfelt pains, or that ordinary pain language countenances unfelt pains, but instead is arguing that certain unconscious mental states are similar enough to the mental states we call pains that they should be included under that label.

Most philosophers who advocate the view that pains can be unconscious mental states today are representationalists who believe that it is reasonable to refer to first-order representations of certain bodily conditions as being pains [e.g. Lycan (1995)]. Some follow Armstrong in suggesting that this would be a reasonable expansion of our current use of pain terminology. Carruthers (2004: p. 108), however, argues that the ordinary concept of pain does not support the existence of unfelt pains:

I am not saying that [pains] are understood in this way by our common-sense psychology. One significant difference between pain and vision, for example, is that we ordinary folk have a proto-theory of the mechanisms that mediate vision…. In contrast, we have very little idea of how experiences of pain are caused. Partly for this reason, and partly because pains aren’t inter-subjectively available in the way that colors are, we don’t have much use for the idea of an unfelt pain, in the way that we are perfectly comfortable with the idea of unperceived colors.

While Carruthers seems to accept the claims about the ordinary concept of pain that one finds in defenses of the standard view, other higher order theorists have not conceded even this point. A good example is Bill Lycan (1995: p. 3), who writes:

Consider pain. A minor pain may go unfelt, or so we sometimes say. Even quite a bad pain may not be felt if attention is distracted by sufficiently pressing concerns. Yet such assertions as my last two can sound anomalous; as David Lewis once said, meaning to tautologize, “pain is a feeling.” When one person’s commonplace sounds to another contradictory on its face, we should suspect equivocation, and the Inner Sense model delivers: Sometimes the word “pain” is used to mean just the first-order representation of damage or disorder, a representation which can go unnoticed. But sometimes “pain” means a conscious feeling or mode of awareness, and on that usage the phrase “unfelt pain” is simply self-contradictory; it comprehends both the first-order representation and the second-order scanning together. Thus the equivocation, which gave rise to the issue; the issue is dissolved. (1995: p. 3)

Lycan suggests that, as a matter of fact, we do sometimes use pain language to refer to first-order representations of damage or disorder, offering an example from the John Grisham novel, The Firm: “Each step was painful, but the pain was not felt. He moved at a controlled jog down the escalators and out of the building.” In this passage, Grisham seems to countenance the occurrence of unfelt pain (and many other popular examples could be given). It is far from clear, however, that Grisham is best read as identifying the unfelt pain with something like a “first-order representation of damage or disorder.” And there is, we think, a fairly obvious alternative that we will discuss in the next section—Grisham could be thinking of the pain as a quality of the damaged leg.

3 Pains as bodily states

The bodily conception of pain offers a radical alternative to mental state views. According to this view, pains are not mental states—be those mental states phenomenally conscious or not—but are qualities of bodily disturbances. These qualities are then (sometimes) perceived by sentient beings, typically the being whose body part has suffered the disturbance.

Before proceeding, a couple of clarifications are in order. It is important to note that the bodily conception is not the relatively weak view that people often use (or should use) pain language to refer to the causes of our pains (where this is taken to be a bodily disturbance) rather than the pain itself (where this is taken to be an unpleasant experience). According to the bodily conception, the qualities we are acquainted with when we feel pains are qualities of bodily disturbances and can exist whether or not anybody feels them at a given time.

As alluded to in the previous section, it is also important to distinguish between the truth of an account of pain and whether that account adequately captures the commonsense conception. After all, there is no guarantee that the commonsense conception is the right one. That said, we saw in the first section that most philosophers working on pain treat compliance with the commonsense conception of pain as an important desideratum in our theorizing about pain. Philosophers like Aydede and Hill, for example, seem to hold that an account of pain is prima facie good insofar as it corresponds with our intuitions about key cases and prima facie bad insofar as it contradicts our intuitions about key cases. Thus, while our focus in this article is on investigating the commonsense conception of pain and the ordinary use of pain language in English, how this investigation turns out will have clear implications for the philosophical debates on the nature of pain.

While the bodily conception of pain has received scant philosophical attention, there is some anecdotal reason to think that lay people might hold such a conception. In fact, several reasons have already been hinted at in the preceding discussion. First, recall that Carruthers compared the commonsense conception of pain with that of vision, suggesting that the latter distinguishes between colors and the perception of colors while the former does not distinguish between pains and the perception of pains. Accepting that lay people tend to hold such a view of colors,Footnote 4 however, we might expect that they will hold a similar view of pains, since absent evidence to the contrary it would be reasonable to expect that people hold similar views about perception across the different sense modalities. Further, we might speculate that people distinguish between colors and the perception of colors because the phenomenology seems to place colors in the world. But, a similar point holds for feeling pain, as noted in the previous section—typically, when one feels a pain that pain feels as if it were located somewhere in the body. As such, we might reasonably speculate that people will also tend to distinguish between pains and the perception of pains.

Second, recall that Aydede holds that there are two main threads in the commonsense conception of pain. He argues that the dominant thread—the one he identifies with the ordinary concept of pain—corresponds with the standard view, ruling out the occurrence of unfelt pains. Aydede considers these two threads because he finds that everyday pain talk in English often seems to run counter to the standard view. For instance, he notes that we often speak of pains being located in afflicted body parts. Aydede then discusses attempts to downplay these troubling ways of speaking. For example, one might suggest (Aydede 2009: p. 25) that “colloquial ways of speaking just jumble the pain with the disturbance, and thus confuse and mislead us”.Footnote 5 Absent evidence that the intuitions of native English-speakers actually turn out the way that Aydede asserts, however, we see little reason to attempt to explain away such common turns of phrase. Instead we see these ways of speaking as providing further reason to hypothesize that the commonsense conception of pain corresponds with the bodily conception.

Finally, there are a number of other common bits of pain language that suggest that the commonsense conception of pain countenances unfelt pains. For example, we saw in Sect. 1 that Hill worries about people saying that they were woken up by a pain. Others have noted that people often talk as if they can be distracted from pains, which indicates that those pains remain present without us being conscious of them. Similarly, Lycan (2004: p. 106) writes that “given a mild pain that I have, I may be only very dimly and peripherally aware of it (assuming I am aware of it at all).” In a like vein, people sometimes speak of feeling the same pain again, suggesting that the pain continued across a period of time when the person was distracted from it or otherwise not feeling it. Taking such instances of pain talk to reflect the commonsense conception of pain, we have further reason to suspect that it diverges from the standard view.

Our goal in the remainder of this article will be to provide empirical evidence concerning the commonsense conception of pain, focusing on whether or not it corresponds with the standard view in denying the possibility of unfelt pains. And, we will argue that the evidence is rather overwhelming in indicating that native English-speakers tend to hold that it is possible to have unfelt pains. While showing that lay people countenance the occurrence of unfelt pains suggests that they do not hold the standard view, it does not indicate whether they instead hold the unconscious mental state view or the bodily conception (or some other type of view all together). Nonetheless, some of the evidence that we will present is most naturally interpreted as indicating that lay people hold that it is possible to have unfelt pains because they take pains to be located in body parts.

4 Previous empirical studies

In recent years, there has been a flurry of research in experimental philosophy of mind investigating how people understand and attribute mental states that philosophers treat as being phenomenally conscious.Footnote 6 Several lines of study in this literature have a bearing on the commonsense conception of pain, suggesting that it differs from the standard view.Footnote 7 We briefly review the evidence in this section, before turning to new empirical work in the following section.

Expanding on work indicating that lay people do not employ the concept of phenomenal consciousness, Sytsma (2012) hypothesized that lay people hold a naïve view for pains.Footnote 8 The idea is that people tended to deny that a simple robot felt pain because they take pains to be instantiated in body parts, but doubted that the robot had the right sort of body parts for pains to be instantiated in—having hard and metallic body parts rather than soft and fleshy ones. To test this hypothesis, Sytsma ran a study in which participants were given a vignette describing a human (Susan) who lost a hand in an accident and had it replaced with either a hard and metallic robotic hand or a soft and fleshy bioengineered hand, which was then injured. He found that participants were significantly more likely to say that Susan felt pain when she had the bioengineered hand than when she had the robotic hand.

In a different type of study, Reuter (2011) found evidence that ordinary pain talk corresponds with an appearance–reality distinction, and thus diverges from the standard view of pains. He conducted linguistic corpora studies on pain expressions, which revealed that the use of different pain expressions depends on the intensity of the experienced pain: when a pain is strong, people tend to say that they have a pain, whereas milder pains are usually expressed by saying that a pain is merely felt. Drawing an analogy with visual, auditory and olfactory appearance statements, Reuter concludes that people do in fact distinguish the appearance from the reality of pain.

In another series of studies, Reuter et al. (2014) investigated the claim that the commonsense conception of pain draws an appearance–reality distinction in another way. They noted that if lay people draw this distinction, then they should hold that it is possible to have pain hallucinations and pain illusions. In contrast, the standard view of pain denies that this is possible, since it holds that having the appearance of a pain just is to have an actual pain. Contrary to what one would expect if the commonsense conception of pain corresponds with the standard view, in one study Reuter et al. found that almost two-thirds of the participants surveyed endorsed the possibility of pain hallucinations. And in another study, they found that more than 80% of participants agreed that illusions about the intensity of a pain were possible, while more than 70% accepted that it is possible to have illusions regarding the location of a pain.

Sytsma (2010) presents results suggesting that the commonsense view of pain does not correspond with the standard view but with the bodily conception. First, he gave participants a short vignette describing both the standard view of pain and the bodily conception, then asked them a series of questions about their understanding of pain. He found that a majority of the lay people surveyed denied the standard view and accepted the bodily conception. Further, Sytsma found that a majority of the participants held that “there is still pain in a badly injured leg even when the person is not aware of it,” providing initial evidence that the ordinary conception allows for unfelt pains. This was extended in his third and fourth studies using two variations on a case where a patient is distracted from a severe pain. Sytsma found that a significant majority in each study treated this as a case of unfelt pain.

Finally, Kim et al. (2016) ran two cross-cultural studies asking American and South Korean participants about the location of referred pains (i.e., cases where the felt location of the pain diverges from the corresponding bodily damage). In each case a large majority of each group located the pain in the body (either where it was felt to be or where the bodily damage was), while only a small minority located it in the mind.

5 New empirical studies

In the previous section, we noted that a number of recent studies suggests that despite what many philosophers have assumed, the commonsense conception of pain diverges from the standard view in philosophy. Given that many philosophers have specifically claimed that people find it to be absurd to say that a pain could exist without being felt, however, we believe that further evidence is needed to make a compelling case that lay people do in fact allow for the possibility of unfelt pains. As such, we turn now to the results of 17 new empirical studies across four different approaches that indicate that adult English-speakers tend to accept that unfelt pains are possible. We begin by replicating the result of Sytsma’s (2010) distracted patient case. We then turn to variations on the painkiller thought experiment presented by Aydede and the injured soldier thought experiment presented by Hill. Finally, we ask participants a series of direct questions about the possibility of unfelt pains.

5.1 Distracted patient case (Study 1)

Recall that in Sect. 2 we saw that Dretske (2006: p. 59) notes that “some think there can be pains one doesn’t feel, pains one is (for a certain interval) not conscious of (‘I was so distracted I forgot about my headache’).” Do non-philosophers tend to agree with this alternative position, or do they follow the standard view as many philosophers have asserted? We saw in the previous section that when Sytsma (2010) presented participants with a scenario in which an injured person is distracted from a pain, they tended to answer that the patient was nonetheless in pain during this period. In our first study, we begin by replicating this result, using the vignette used in Sytsma’s original study, but converting the question to binary answer choices and soliciting responses online rather than in the classroom as in Sytsma’s original study:

Doctors have observed that sometimes a patient who has been badly injured will get wrapped up in an interesting conversation, an intense movie, or a good book. Afterwards, the person will often report that during that period of time they hadn’t been aware of any pain.

Which of the following descriptions of this type of situation seems most appropriate to you?

(A) The injured person still had the pain and was just not feeling it during that period.

(B) The injured person had no pain during that period.

The order of the answer choices was randomly determined, although we’ll report the responses using the ordering shown above. The same was done for all subsequent studies using binary answer choices.

Responses were collected from 31 native English-speakers, 16 years of age or older, who completed the survey, had not taken a survey through the website previously, and had at most minimal training in philosophy.Footnote 9,Footnote 10 The results are striking: 90.3% of the participants surveyed selected the (A) answer choice, indicating that they take this to be a case of unfelt pain. This was significantly above 50%.Footnote 11

5.2 Painkiller cases (Studies 2–5)

In Sect. 1 we saw that Aydede supports the claim that the “ordinary or dominant concept of pain” corresponds with the standard view by appealing to his intuition about a case in which a person feels no pain because he has taken a painkiller. In such cases he asserts that the intuitively correct answer is that there is no pain. Is Aydede’s intuition representative of lay people?

To test this, we ran a series of four studies in which participants were given a vignette about a woman who was injured, rushed to the hospital, and given a painkiller. The vignette for Study 2 read as follows:

Sally works at an industrial factory. One day the machine she was using malfunctioned, severely burning her left hand. Sally grimaced and shouted out “Ouch!” She was immediately rushed to the hospital, where she was given a pill for the pain. Ten minutes later, the doctor arrived to examine Sally. When the doctor pushed on the injured hand, Sally merely shrugged her shoulders and said it didn’t hurt at all. The next morning the doctor examined Sally again, after the painkiller had worn off. This time when the doctor pushed on the injured hand, Sally grimaced and shouted out “Ouch!”

After reading this vignette, participants were then asked the following three questions and answered by selecting either “yes” or “no” for each:

- 1.

Was there a pain in Sally’s injured hand when she arrived at the hospital?

- 2.

Was there a pain in Sally’s injured hand when the doctor examined her the first time, even though she didn’t feel it?

- 3.

Was there a pain in Sally’s injured hand when the doctor examined her the second time?

The second question served to test whether participants found this to be a case of unfelt pain, while the first and third questions served as material checks and tested whether participants are employing an unduly skeptical standard for pain attributions.

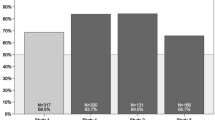

Responses were collected from 67 participants.Footnote 12 The results for all studies in this sub-section are shown in Fig. 1. We found strong agreement with Questions 1 and 3, indicating that a vast majority of participants attributed pain to Sally when she arrived at the hospital and when the doctor examined her for the second time.Footnote 13 Pace Aydede’s intuition, we found that a significant majority of the participants (67.2%) treated the painkiller case as an instance of an unfelt pain.Footnote 14 Again it appears that lay people tend to accept that it is possible to have an unfelt pain. Note, that it is unlikely that people interpreted the question about whether there was a pain as a question about whether there was an injury in Sally’s hand, because the question explicitly asked participants about “Sally’s injured hand.”

After conducting this study, we had worries that the phrase “didn’t feel it” in the second question might be taken to imply that there was an ongoing pain there to be felt. To control for this, in Study 3 we replaced the phrase with “didn’t feel pain.” Responses were collected from 88 participants.Footnote 15 Again, we found that participants tended to treat this as an instance of unfelt pain, with a significant majority (62.5%) selecting the “yes” answer.Footnote 16 To further test this worry, in Study 4 we instead revised the phrase “didn’t feel it” in the second question to “didn’t feel any pain”; in addition, the vignette was revised to replace “and said it didn’t hurt at all” with “and said she didn’t feel any pain.” Responses were collected from 156 participants.Footnote 17 Yet again we found that a significant majority of participants (70.5%) gave the “yes” response.Footnote 18

Finally, in Study 5 we used the same vignette as Study 4, but replaced the binary questions with questions using a Likert scale to allow participants to select a neutral answer and to indicate their degree of agreement/disagreement. In this study, after reading the vignette participants were asked to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with each of the following three claims using a 7-point scale with 1 anchored with “Totally Disagree,” 4 with “Neutral,” and 7 with “Totally Agree”:

- 1.

There was a pain in Sally’s injured hand when she arrived at the hospital.

- 2.

There was a pain in Sally’s injured hand when the doctor examined her the first time, even though she didn’t feel any pain.

- 3.

There was a pain in Sally’s injured hand when the doctor examined her the second time.

Responses were collected from 38 participants.Footnote 19 Once again, we found that participants treated this as a case of unfelt pain. The mean response for Question 2 was 5.24, which was significantly above the neutral point.Footnote 20

5.3 Injured soldier cases (Studies 6–9)

In Sect. 1 we saw that, like Aydede, Hill supports the claim that the commonsense conception of pain corresponds with the standard view by calling on intuitions about a thought experiment—this time involving the case of an injured soldier that professes to feel no pain. And like Aydede, Hill appears to hold that his intuition about this is representative of lay people. In fact, he tells us that when he has “asked informants to assess the likelihood of this scenario… they have all been inclined to dismiss it as absurd” (2009: p. 171). But we might wonder just who Hill’s informants were, how many of them Hill asked, how they were selected, and how the scenario was posed to them. Given that Hill treats this as an empirical matter—having taken the responses of his informants to be relevant information—we have clear reason to test people’s intuitions about this type of case in a more transparent and systematic manner.

We began in Study 6 by presenting participants with an extended vignette providing a clear example of an injured soldier professing to feel no pain. For this purpose, we used a passage from Orwell’s (1938) account of his involvement in the Spanish Civil War in which he describes being wounded by a sniper, but having no feeling of pain until sometime later when his broken right arm “came to life and began hurting damnably”.Footnote 21 Participants were then asked: “Before his broken arm came to life, do you think that there was a pain and Orwell just didn’t feel it or that there was no pain until his broken arm came to life?” Participants answered by selecting one of two answer choices:

- (A)

There was a pain and Orwell didn’t feel it.

- (B)

There was no pain.

Responses were collected from 47 participants.Footnote 22 The results for each study in this sub-section are shown in Fig. 2 below. Pace Hill, we found that a significant majority of participants tended to treat this as a case of unfelt pain, with 83.0% giving the (A) response.Footnote 23

In Study 7, participants were given the same vignette as in Study 6, but answered using a 7-point scale with 1 anchored with “clearly there was a pain and Orwell didn’t feel it,” 4 anchored with “not sure,” and 7 anchored with “clearly there was no pain.” Responses were collected from 42 participants.Footnote 24 Once again we found that participants tended to treat this as a case of unfelt pain. The mean response was 3.17, which was significantly below the neutral point, and 59.5% gave an answer of 1, 2, or 3.Footnote 25

One potential worry is that the Orwell vignette was quite long and contained pain language that could potentially bias participants. As such, in Studies 8 and 9 we gave participants a simplified vignette based on the language used by Hill in presenting his thought experiment:

Soldiers often sustain serious injuries but show no sign of feeling any pain, continuing to display normal behavior. They also deny that they feel any pain. Only after the end of the battle, do soldiers proclaim they feel severe pain and show clear pain behavior.

In Study 8 participants were asked which of the following two descriptions about this type of case seemed most appropriate to them:

- (A)

During the battle, the injured soldier has a pain but doesn’t feel it.

- (B)

During the battle, the injured soldier has no pain.

Responses were collected from 57 participants.Footnote 26 As in Study 6, we found that a significant majority of participants treated this as a case of unfelt pain, with 70.2% giving the (A) response.Footnote 27

In Study 9, participants were instead asked: “In a situation like this, do you think that an injured soldier has a pain during the battle and just doesn’t feel it or that the injured soldier has no pain?” They answered using a 7-point scale anchored at 1 with “clearly has a pain and doesn’t feel it,” at 4 with “not sure,” and at 7 with “clearly has no pain.” Responses were collected from 35 participants.Footnote 28 Again, we found that a significant majority of participants treated this as a case of unfelt pain. The mean response was 2.23, with 80.0% giving an answer of 1, 2, or 3.Footnote 29

5.4 Pains that are never felt (Study 10)

The results of the studies so far strongly suggest that a majority of people believe unfelt pains to be possible. However, each of these studies asked participants to read scenarios in which pains were felt at least at some point. As seen above, this corresponds with what is found in the philosophical literature. Nonetheless, one might wonder whether people also accept the existence of pains that are never felt. This is an interesting question that is not clearly addressed by our previous studies. Further, the lack of empirical evidence with regard to judgments about the existence of pains that are never felt allows for a potential objection.Footnote 30 When participants read that a pain was felt at two separate times, such as in the painkiller case, they might be inclined to think that the pain must have existed across this period, not because their concept of pain allows for unfelt pains but because of the superficial similarity of such cases with the persistence of objects across time. This challenge is exacerbated by the fact that we often speak as if pains that were felt at different times, are one and the same pain. For instance, David Papineau argues that “it is true that we often say things like ‘Oh dear, there’s that pain again—I thought I was rid of it’” (2007, p. 101).Footnote 31 Many people might then infer that if the same pain that was felt at a later time was already felt at an earlier time, then it must have also existed across this span, even though this clashes with their conception of pains as subjective.

While we believe this challenge has some initial plausibility, it should be noted that we found similar results for the injured soldier case, which has quite a different set-up: we asked participants to judge whether a soldier had a pain without having previously felt it. It is therefore unlikely that those participants were biased into thinking that the pain must have existed before it was felt. In order to deal with this challenge more decisively, however, we modified the injured soldier vignette from Studies 8 and 9 to make it so that the pain was never felt:

Soldiers often sustain serious injuries but show no sign of feeling any pain, continuing to display normal behavior. They also deny that they feel any pain. Only after the end of the battle, do soldiers proclaim they feel severe pain and show clear pain behavior.

Greg was a soldier who sustained a serious injury in battle, receiving a shot through his left leg. Right after the incident, a field medic examined him. Greg denied that he felt any pain, despite the horrible injury. Unfortunately, Greg died while being evacuated from the battlefield, shortly after the medic had examined him.

We then asked the participants “Which of the following descriptions about this case seems most appropriate to you?” They answered by selecting one of the following two choices:

- (A)

When the field medic was examining his injury, Greg had a pain but didn’t feel it.

- (B)

When the field medic was examining his injury, Greg had no pain.

Responses were collected from 97 participants.Footnote 32 In line with our previous studies, and against the objection, a significant majority (67.0%) selected the first response option, indicating that they think of the situation as a case in which a pain existed although it was never felt.Footnote 33,Footnote 34

Note that we do not hold that people consider such pains to be typical. Prototypical pains hurt and will be felt by the subject. Moreover, we expect many people to be resistant to the idea of positing pains that are never felt (see also the results in Sect. 5.5). This is in part because the phenomenal feel of a pain is the main (and often the sole) indicator for having a pain. As such, skepticism will often be warranted with regard to pains that are never felt. Additionally, people usually consider other persons to be authoritative over whether or not they have a pain and hardly challenge others about the existence of pains that are not felt at a certain point in time (for a more detailed discussion of this point, see Reuter 2017). Nonetheless, the results show that most people consider the existence of pains to not depend on them being felt by the person having the pain.

5.5 Direct questions (Studies 11–17)

In our next series of studies, we turned from asking participants questions about thought experiments to more direct questions about whether there can be unfelt pains. We began in Study 11 by investigating whether people believe that all pains are felt, as would be expected if they deny the possibility of unfelt pains. Participants were asked “Which of the following statements about pains seems most correct to you?” then given four answer choices to select from:

All Pains are felt.

Most pains are felt.

Some pains are felt.

No pains are felt.

Responses were collected from 204 participants.Footnote 35 The results for these four studies are shown in Fig. 3. We found that only a minority (46.1%) selected the “all” response, although this was not significantly below 50%.Footnote 36 In comparison, 32.8% selected “most,” 21.1% selected “some,” and nobody selected “none.”

Noting that advocates of the standard view have a specific type of feeling in mind when they assert that all pains are felt—i.e., pains hurt—in Study 12 we investigated whether people believe that all pains hurt. Participants were asked the same question as in Study 11, but with “hurt” replacing “are felt” in each answer choice. Responses were collected from 264 participants.Footnote 37 Again we found that only a minority (41.3%) selected the “all” response, which was significantly below 50%.Footnote 38 In comparison, 18.9% selected “most,” 38.6% selected “some,” and 1.1% selected “none.”

While only a minority selected the “all” option in each of these studies, this was nonetheless the most common single answer, and the percentages were higher than we expected based on the data of our previous studies. One potential explanation is that participants might have read the answer choices as meaning that the pains are felt (or hurt) at some point in time. For example, they might have read “all pains hurt” as meaning “all pains hurt at some point,” which is compatible with the occurrence of unfelt pains. This seems plausible when one considers statements with a similar structure, such as “all chefs cook,” which would seem to be true even though there are times when a given chef isn’t cooking.

To correct for this issue, in our next two studies we added the timeframe to the answer choices from the previous studies. In Study 13 participants were given the following four answer choices:

When you have a pain, you feel that pain all of the time.

When you have a pain, you feel that pain most of the time.

When you have a pain, you feel that pain some of the time.

When you have a pain, you feel that pain none of the time.

Responses were collected from 106 participants.Footnote 39 Once again, we found that only a minority of the participants surveyed selected the “all” answer choice. This time, however, the percentages were much lower, with only 8.5% of participants answering that when you have a pain, you feel that pain all of the time. This was significantly below 50%.Footnote 40 In comparison, a large majority selected either “most” (25.5%) or “some” (65.1%).

In Study 14, we repeated the previous study but replaced “you feel that pain” with “that pain hurts” for each answer choice. Responses were collected from 155 participants.Footnote 41 Again we found that only a minority (12.9%) selected the “all” answer choice. This was significantly below 50%.Footnote 42 In comparison, a large majority selected either “most” (21.9%) or “some” (63.9%).

Next, we conducted a pair of studies in which we asked participants directly about the possibility of unfelt pains. In Study 15, we gave participants two sets of two questions on consecutive pages (they were not able to go back to change previous answers):

- 1.

Is it possible for a person to have a pain that they don’t feel for a period of time?

- 2.

Have you ever had a pain that you didn’t feel for a period of time?

- 3.

Is it possible for a person to have a pain that doesn’t hurt for a period of time?

- 4.

Have you ever had a pain that didn’t hurt for a period of time?

The order of the sets of questions were randomly assigned, although we will discuss them in the order shown above. Participants answered each question by selecting either “yes” or “no.” Responses were collected from 51 participants.Footnote 43 The results are shown in Fig. 3. In line with our previous results, we found that a significant majority of participants answered that it is possible to have an unfelt pain (92.2%) and that a significant majority answered that it is possible to have a pain that doesn’t hurt (90.2%); in fact, a significant majority of participants answered that they have had an unfelt pain (88.2%) and a significant majority of participants answered they have had a pain that didn’t hurt (86.3%).Footnote 44

In Study 16, participants were given the same four questions but answered on a 7-point scale anchored at 1 with “clearly no,” at 4 with “not sure,” and at 7 with “clearly yes.” Responses were collected from 62 participants.Footnote 45 Results were comparable to those for Study 15, with the mean response for each question being significantly above the neutral point (5.56, 4.77, 5.29, 4.77).Footnote 46

Finally, in Study 17 we removed the explicit mention of the pain not being felt for some period of time, asking participants simply: “Is it possible to have a pain that is not felt?”Footnote 47 They answered by selecting either “yes” or “no.” Responses were collected from 64 participants using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.Footnote 48 Again we found that a significant majority (60.9%) answered affirmatively.Footnote 49

6 Discussion

The question of whether ordinary people hold that unfelt pains are possible serves as a litmus test for whether common sense supports the standard view of pain: if empirical results show that ordinary people do not allow for unfelt pains, experimental studies on other aspects of the standard view will do little to convince proponents that their position is flawed; in contrast, if empirical work demonstrates that ordinary people allow for unfelt pains, the most important stronghold of the standard view crumbles. In this paper, we have carried out this litmus test.

Across 17 studies utilizing four distinct approaches, including both direct and indirect questions, the results suggest that English speakers hold that unfelt pains are possible. The results of any given study clearly leave open the possibility that the common-sense conception of pain aligns with the standard view of pain despite the results we obtained. The reason is that it is difficult to design experiments that do not bias people in one way or another. Nonetheless, by coming at the question from a number of different angles, we hoped to forestall worries about any given study. We believe that the combined array of results all pointing in the same direction provide compelling evidence that contra what many philosophers have asserted, lay people do in fact countenance the possibility of unfelt pains.

The first three sets of studies we conducted were indirect investigations of the ordinary conception of pain and were inspired by philosophers discussing the possibility of unfelt pains—the distracted-patient case suggested by Dretske (2006), Papineau (2007), and others; the painkiller case inspired by Aydede (2009); and the injured-soldier case proposed by Hill (2009). As such, it cannot be readily argued that we presented participants with scenarios that might bias their responses. Instead we chose cases that the main players in this debate take to be crucial for determining whether unfelt pains are possible.

Not surprisingly, there are good reasons to believe that these scenarios are well suited to tap into people’s views about the possibility of unfelt pains. It is an undisputed part of the commonsense conception of pain that acute pains are typically associated with bodily damage, and that is the case in the distracted-patient, painkiller, and injured-soldier scenarios. Furthermore, it is common knowledge that there are means to eliminate our awareness of pain—most notably, mental distraction, painkillers, and adrenaline. We made sure that participants understood this by pointing out that while bodily damage existed, no pain was felt by the protagonist. Thus, all three sets of studies were structurally set-up to allow for the investigation of people’s views on unfelt pains. And, again, the results were unambiguous: a clear majority of the participants supported the notion of unfelt pains both in forced-choice tasks as well as in Likert-scale tasks.

The fourth and last set of studies asked people directly and fairly explicitly about their views on whether pains can exist unfelt. Once again the results were unambiguous: across eight direct studies, not a single one yielded a result supporting the standard view of pain. Instead, in each case a majority explicitly opted against the view that pains need to be felt in order to exist.

One possible objection that might be raised against our studies concerns their imaginary character. After all, participants were not put into pain as part of the studies. Instead, focusing on the indirect studies, participants were simply asked to imagine scenarios in which a person had tissue damage without reporting that he/she felt pain at a given time. It is possible that results would have turned out differently had people not merely imagined these scenarios, but actually underwent them. Although we cannot rule out a different outcome in such cases, we strongly doubt that the results would have been significantly different. First, the scenarios we used are easy to envision and do not require people to imagine entirely unknown situations. Second, trying to distract oneself from a pain, taking painkillers, and so on, is common behavior in the English-speaking world. As such, it is likely that a majority of the participants have had experience with being distracted from pain or taking painkillers. While very few participants are likely to have had the experiences we describe in the injured soldier case, we expect that most adults have been in situations in which adrenaline has interfered with their feeling pain. That each of the scenarios is fairly common and/or relatively easy to imagine reduces the likelihood that people would come to very different conclusions regarding the existence of pain, were they put into such a situation rather than simply imagining it.Footnote 50

While the results of our studies suggest that the commonsense conception of pain diverges from the standard view, can we say anything more positive about the commonsense conception? We have introduced two alternative accounts—the mental state view, which maintains that unfelt pains are unconscious mental states, and the bodily conception, which maintains that pains are bodily states. The studies we presented in Sect. 5 were primarily designed to test the standard view, not to adjudicate between these alternatives, and the results are consistent with both. While we hold that further empirical work is needed to settle the issue (and are in the process of carrying out such work), we believe that there are at least four reasons to believe that the commonsense conception of pain tends to align with the bodily conception.

First, as noted in Sect. 4, previous empirical work on the ordinary conception of pain amongst English-speakers—especially Sytsma (2010, 2012) and Kim et al. (2016)—suggests that lay people tend to hold a bodily conception. Second, that lay people tend to hold a bodily conception provides the most straightforward explanation for why they tend to allow for unfelt pains. If pains are conceived of as bodily states, then people should judge that unfelt pains are possible. Obviously, the bodily damage continues and hence provides a strong indication that the pain still exists. In contrast, the mental state view postulates a complicated causal mechanism involving bodily tissue damage, a first-order mental state, and an introspective mechanism scanning the first-order mental state. Such a mechanism seems likely to go well beyond what is found in common sense. More importantly, while the bodily conception can easily explain people’s judgments that unfelt pains are in the body, the mental state view needs to make plausible the notion that people refer to unconscious mental states when they talk about unfelt pains. However, no indication of such unconscious mental states is given to a person when she no longer feels a pain.

Third, both Aydede (2006) and Hill (2009) have argued that the commonsense conception of pain is in tension with the semantic properties of pain reports, noting that people standardly report pains to be in body parts. This tension is dissolved if the commonsense conception corresponds with the bodily conception. In contrast, the tension continues on the mental state view, which localizes pains in the mind and not in the body where ordinary pain reports place them.

Fourth, if the mental state view is correct, we would expect people to be hesitant to give affirmative responses to questions localizing pains in body parts. But this is not what we saw in the painkiller studies reported in 5.2, when participants were asked whether “there was a pain in Sally’s injured hand.” If the commonsense conception of pains corresponds with the mental state view, then we would expect lower responses to questions phrased in this way. If people hold a mental state view then they would not think that the pain is in Sally’s injured hand; but, we saw that a significant majority answered that it was.

7 Conclusion

Do unfelt pains exist? Proponents of the standard view answer in the negative and support this view by calling on the supposed commonsense conception of pain. Building on previous empirical research, in this paper we have presented the results of 17 new empirical studies indicating that proponents of the standard view are simply mistaken about the commonsense conception of pain: across these studies a substantial majority responded that unfelt pains are possible. While we have argued that our data puts into doubt the plausibility of the standard view, further tests are needed to decide whether a bodily view of pains should be preferred, or whether a more refined mental states view of pain can be rescued.

Notes

This view is not only found amongst philosophers, but extends to scientists studying pain as well. For instance, the International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” and they go on to note that “activity induced in the nociceptor and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain, which is always a psychological state, even though we may well appreciate that pain most often has a proximate physical cause” (1986: p. 250).

The putative tension between the two threads is part of the reasoning of why philosophers have considered the ordinary concept of pain to be paradoxical. Note, however, that especially Aydede has cast little doubt that the intuitions of laypeople are very clear in supporting the standard view of pain, in particular by ruling out the possibility of unfelt pains. The so-called paradox of pain that both Aydede and Hill highlight, arises more directly because of the tension between the semantic properties of pain expressions that point to a bodily conception of pain and the standard view that treats pains as mental states. Both philosophers have offered interesting ways of solving this putative paradox. However, we will not engage with their arguments as the point of this paper is a different one: if the standard view of pain is mistaken, no such paradox of pain even begins to arise (see also Reuter 2017).

In fact, Hill (2009) has argued that the best way to solve these conceptual difficulties would be to introduce two new concepts, one referring to bodily disturbances and the other referring to mental states.

In fact, there is evidence that most native English speakers distinguish between colors and the perception of colors. Sytsma (2009) argues that lay people tend to hold a naïve view of colors, treating them not as phenomenal qualities, but as mind-independent qualities of objects located outside of the mind/brain. This line of argument is further developed in Sytsma (2010), which presents empirical evidence for the claim.

See e.g. Tye (2006) for holding such a view.

See Sytsma and Reuter (2017) for a recent overview on experimental philosophy of pain.

While this paper focuses on the question of whether lay people accept the possibility of unfelt pains, it is worth briefly noting that the results have implications for wider debates in philosophy of mind. Sytsma and Machery (2010) argue that a principal reason offered in the recent literature for believing in phenomenal consciousness is that its existence is pretheoretically obvious. If this is the case, however, then we should expect lay people to employ something like the philosophical concept in making mental state attributions. But there is a growing body of evidence that lay people do not categorize mental states along phenomenal lines as philosophers do (Sytsma and Machery 2009, 2010, 2012; Sytsma 2010, 2012, 2014b; see Machery and Sytsma 2011 for a brief overview). Insofar as pains are often taken by philosophers to be paradigmatic examples of phenomenally conscious mental states, evidence that lay people do not conceive of pains in this way offers some support for the claim that they do not employ the concept of phenomenal consciousness.

The same restrictions were used for each study reported in this paper. Responses for all studies were collected through the Philosophical Personality website (http://philosophicalpersonality.com), except where otherwise indicated. Participants were counted as having more than minimal training in philosophy if they were philosophy majors, had completed a degree with a major in philosophy, or had taken graduate-level courses in philosophy.

77.4% women, with an average age of 45.0 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 72.

χ2(1, N = 31) = 18.58, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

74.6% women, with an average age of 35.3 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 88.

92.5% answered “yes” to Question 1 and 91.0% answered “yes” to Question 3.

χ2(1, N = 67) = 7.22, p = 0.004, one-tailed. The same holds if we remove the seven participants who answered “no” to either Question 1 or Question 3: 71.7% answered “yes” to Question 2, which is significantly above 50%—χ2(1, N = 60) = 10.42, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

70.5% women, with an average age of 34.6 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 74.

χ2(1, N = 88) = 5.01, p = 0.013, one-tailed. Again, we found strong agreement with Questions 1 and 3, with 94.3% selecting “yes” for each question. And the results for Question 2 remain significant if we remove the eight participants who answered “no” to either question: 63.8% answered “yes” to Question 2, which is significantly above 50%—χ2(1, N = 80) = 5.51, p = 0.009, one-tailed.

80.1% women, with an average age of 41.1 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 75.

χ2(1, N = 156) = 25.44, p < 0.001, one-tailed. Again, we found strong agreement with Questions 1 and 3, with 95.5% selecting “yes” for the former and 96.8% for the latter. And the results for Question 2 remain significant if we remove the 11 participants who answered “no” to either question: 71.0% answered “yes” to Question 2, which is significantly above 50%—χ2(1, N = 145) = 24.83, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

76.3% women, with an average age of 39.5 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 78.

t(37) = 3.43, p < 0.001. Again, we found strong agreement with Questions 1 and 3, with a mean response of 6.55 for the former and 6.68 for the latter. Further, no participant selected an answer on the lower half of the scale (1, 2, or 3) for either question.

The full vignette is available in the online appendix.

61.7% women, with an average age of 39.3 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 78.

χ2(1, N = 47) = 19.15, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

59.5% women, with an average age of 40.5 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 79.

t(41) = −2.47, p = 0.009, one-tailed.

87.7% women, with an average age of 41.4 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 69.

χ2(1, N = 57) = 8.49, p = 0.002, one-tailed.

74.3% women, with an average age of 45.9 years, and ranging in age from 17 to 73.

t(34) = −5.48, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

We would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for this journal for presenting us with this interesting challenge to the results of some of our studies.

Papineau rejects this case as a possible counterexample to the standard view by arguing that we can only have the same type of pain, not the same token of pain.

58.8% women, with an average age of 39.7 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 74.

χ2(1, N = 97) = 10.56, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

This result was replicated using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. In this replication, 63.2% (67 out of 106) of the participants responded that Greg had a pain but didn't feel it. 50.0% women, with an average age of 35.9 years, and ranging in age from 22 to 67; χ2(1, N = 106) = 13.72, p < 0.01, one-tailed.

86.8% women, with an average age of 47.2 years, and ranging in age from 19 to 72.

χ2(1, N = 204) = 1.10, p = 0.146, one-tailed.

67.4% women, with an average age of 30.3 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 77.

χ2(1, N = 264) = 7.67, p = 0.003, one-tailed.

83.0% women, with an average age of 50.3 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 84.

χ2(1, N = 106) = 71.41, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

61.3% women, with an average age of 30.3 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 81.

χ2(1, N = 155) = 83.85, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

78.4% women, with an average age of 48.4 years, and ranging in age from 26 to 73.

Question 1: χ2(1, N = 51) = 34.59, p < 0.001, one-tailed; Question 2: χ2(1, N = 51) = 28.31, p < 0.001, one-tailed; Question 3: χ2(1, N = 51) = 31.37, p < 0.001, one-tailed; Question 4: χ2(1, N = 51) = 25.41, p < 0.001, one-tailed.

67.7% women, with an average age of 39.6 years, and ranging in age from 16 to 73.

Question 1: t(61) = 8.96, p < 0.001, one-tailed; Question 2: t(61) = 3.02, p = 0.002, one-tailed; Question 3: t(61) = 5.93, p < 0.001, one-tailed; Question 4: t(61) = 2.94, p = 0.002, one-tailed.

We would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for this journal for suggesting this modification.

51.6% were women, with an average age of 35.6 years, and ranging in age from 21 to 70.

χ2(1, N = 64) = 4.50, p = 0.034, one-tailed.

That said, we believe that follow-up studies involving participants currently undergoing pain, such as patients in pain clinics, would be interesting and would directly address this concern.

References

Armstrong, D. (1963). Is introspective knowledge incorrigible? The Philosophical Review,72(4), 417–432.

Aydede, M. (2006). Introduction: A critical and quasi-historical essay on theories of pain. In M. Aydede (Ed.), Pain: New papers on its nature and the methodology of its study (pp. 1–58). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Aydede, M. (2009). Pain. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2013 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2013/entries/pain/.

Carruthers, P. (2004). Suffering without subjectivity. Philosophical Studies,121(2), 99–125.

Dennett, D. (1986). Content and consciousness (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Dretske, F. (2006). The epistemology of pain. In M. Aydede (Ed.), Pain: New papers on its nature and the methodology of its study (pp. 59–74). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hill, C. (2009). Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, H., Poth, N., Reuter, K., & Sytsma, J. (2016). Where is your pain? A cross-cultural comparison of the concept of pain in Americans and South Koreans. Studia Philosophica Estonica,9(1), 136–169.

Kripke, S. (1980). Naming and necessity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Levine, J. (2008). Secondary qualities: Where consciousness and intentionality meet. The Monist,91(2), 215–236.

Lycan, W. (1995). Consciousness as internal monitoring, I: The third philosophical perspectives lecture. Philosophical Perspectives,95(9), 1–14.

Lycan, W. (2004). The superiority of HOP to HOT. Advances of Consciousness Research,56, 93–114.

Machery, E., & Sytsma, J. (2011). Robot pains and corporate feelings. The Philosophers’ Magazine,52, 78–82.

Orwell, G. (1938/1952). Homage to Catalonia. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Papineau, D. (2007). Phenomenal concepts are not demonstrative. In M. McCabe & M. Textor (Eds.), Perspectives on Perception (Vol. 6). Walter de Gruyter.

Reid, T. (1785). Essays on the intellectual powers of man. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Reuter, K. (2011). Distinguishing the appearance from the reality of pain. Journal of Consciousness Studies,18(9-10), 94–109.

Reuter, K. (2017). The developmental challenge to the paradox of pain. Erkenntnis,82(2), 265–283.

Reuter, K., Phillips, D., & Sytsma, J. (2014). Hallucinating pain. In J. Sytsma (Ed.), Advances in experimental philosophy of mind. London: Bloomsbury.

Sytsma, J. (2009). Phenomenological obviousness and the new science of consciousness. Philosophy of Science,76(5), 958–969.

Sytsma, J. (2010). Dennett’s theory of the folk theory of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies,17(3–4), 107–130.

Sytsma, J. (2012). Revisiting the valence account. Philosophical Topics,40(2), 179–198.

Sytsma, J. (2014a). Advances in experimental philosophy of mind. London: Bloomsbury.

Sytsma, J. (2014b). The robots of the dawn of experimental philosophy of mind. In E. Machery & E. O’Neill (Eds.), Current controversies in experimental philosophy. New York: Routledge.

Sytsma, J. (2016). Attributions of consciousness. In J. Sytsma & W. Buckwalter (Eds.), A companion to experimental philosophy. West Sussex: Wiley.

Sytsma, J., & Buckwalter, W. (2016). A companion to experimental philosophy. West Sussex: Wiley.

Sytsma, J., & Livengood, J. (2015). The theory and practice of experimental philosophy. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Sytsma, J., & Machery, E. (2009). How to study folk intuitions about phenomenal consciousness. Philosophical Psychology,22(1), 21–35.

Sytsma, J., & Machery, E. (2010). Two conceptions of subjective experience. Philosophical Studies,151(2), 299–327.

Sytsma, J., & Machery, E. (2012). On the relevance of folk intuitions: A reply to Talbot. Consciousness and Cognition,21(2), 654–660.

Sytsma, J., & Reuter, K. (2017). Experimental philosophy of pain. Journal of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research,34(3), 611–628.

Tye, M. (2006). Another look at representationalism about pain. In M. Aydede (Ed.), Pain: New papers on its nature and the methodology of its study. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a FHSS JRC Small Grant from Victoria University of Wellington. We would like to thank the audiences at Ruhr University Bochum, University of Glasgow, University of Bern, Victoria University of Wellington, University of Auckland, Nanzan University, as well as the Philosophy of Science Association, the International Congress of Psychology, and the Society for Philosophy and Psychology for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reuter, K., Sytsma, J. Unfelt pain. Synthese 197, 1777–1801 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1770-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1770-3