Abstract

It is part of the daily routine of companies to deal with different problems and, among them, the so-called complexes, characterized by the existence of multiple parties, different perspectives and objectives, conflicting interests, intangible aspects, and uncertainties. Their solution is strategic in nature and usually involves great opportunities. In the search for solutions to problems, companies use different approaches from different paradigmatic origins. The business management epistemology brings approaches such as Continuous Improvement, Total Quality and Lean Thinking aimed at solving problems and improving processes. In systemic epistemology, approaches such as Systemic Intervention, Critical Systems Heuristics and Theory of Distinctions, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives seek solutions that, in addition to bringing consistent improvements, aim to develop the critical and systemic thinking skills of those involved. Thinking about the need for an approach to deal with complex problems that adapts to the culture and the needs inherent in the business environment, the objective of this paper is to present the critical-systemic intervention method. To this end, systemic, critical, and business management approaches used by companies to deal with problems and promote the continuous improvement of their processes are explored. Afterwards, the method is presented and as a result there is a hybrid intervention approach that aims to support companies in obtaining meaningful solutions for results, sustainable in the long term and that promotes continuous learning and development of the organizational culture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The epistemology of business management brings concepts such as Kaizen (IMAI 1994), Lean Thinking (WOMACK et al. 1990; WOMACK and JONES 1996) and Total Quality Management – TQM (Martinelli, F. B., 2009) aimed at solving operational problems and the continuous improvement of processes.

In systemic epistemology, approaches such as Critical Systems Heuristics – CSH (ULRICH 1983), Systemic Intervention – SI (Midgley 2000), the Distinctions, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives Theory – DSRP (Cabrera 2004), among others, seek solutions which, besides bringing consistent improvements to solve complex problems, aim at developing systemic and critical thinking skills of those involved and, consequently, of the organisations, which are fundamental aspects nowadays.

From the perspective of this paper, appropriate systemic concepts and practices should be applied by companies to promote systemic and critical thinking to address complex problems more effectively. Reflecting on these concepts and approaches, several similarities can be observed, such as: the intention to promote the effective participation of stakeholders; the stimulus to the development of a critical and constructive vision; the search for viable and continuous improvements; among others.

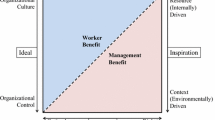

However, some paradigmatic differences regarding the extent of objectives and expectations are noted, since in the case of business management concepts there is a focus on structured problems and direct action, of the “see and act” type, for which the problems are evident, and the actions often depend simply on dedicated resources and time.

Systemic approaches, on the other hand, aim to address unstructured problems, characterized as complex and that, thus, denote greater strategy and reflection in the search for solutions that can be significant for the results and sustainable in the long term. According to MacDuffie (1997), problems related to productive processes, connected to quality and productivity, for example, do not have direct or clear causes, and are hardly solved from a methodology or standardized procedure, because they require a lot of interaction, creativity, and coordination of those involved for the solution.

Maximiano (2005) emphasizes that companies as systems face complex problems in their daily lives. Rosenhead and Mingers (2001) call “complex problems”, or unstructured, those characterized by the existence of multiple actors, multiple perspectives, conflicting interests, distinct objectives, intangible aspects, and uncertainties. Mingers and Rosenhead (2004) observe that, often, the solution of these problems has greater strategic importance.

In this context, “complex business problems” may be present at the operational, tactical, and strategic levels of an organization, related to several perspectives: financial; internal processes and organization; customers and products; relationship with partners; organizational growth and development; among others. Figure 1 shows several types and perspectives of complex business problems that can be found at each level.

For Martinelli, D. P. (2010), most of the corporate management problems are complex and companies have difficulties in dealing with them in an efficient and effective manner, but these are where the greatest gain opportunities lie and, as a result, demand special attention from companies.

In this context, the aim of this paper is to present the hybrid critical-systemic intervention method, obtained from the synergy between concepts and practices of systemic epistemologies and business management, for business application at the operational and strategic levels to address complex problems. At the operational level bringing viable, meaningful, and sustainable solutions to problems, and at the strategic level promoting learning and cognitive development in critical and systemic thinking, essential aspects for the growth and competitiveness of companies today.

Churchman (1971) emphasizes that the systemic vision revolutionized the administration in the areas of business, industry, and the solution of problems, enabling the manager a new view of organizations. For Espejo et al. (1996), an organization that can effectively apply the systemic vision can develop as a viable system, characterized by its ability to solve problems independently, that is, based on its own human, technical, intellectual, and financial resources.

The article is organized into five sections. In this section the research motivations, objectives and contributions were presented. In Sect. 2 the research methods are related. Section 3 presents the theoretical reference about the systemic and business management concepts and practices used in the structuring and solution of problems in companies. In Sect. 4 the proposed intervention method is detailed. Finally, conclusions and final considerations are presented in Sect. 5.

Methods

The methodological procedures adopted involved two stages. Firstly, the three approaches used to ground the proposed method were explored as of searches using the names of authors and their collaborators: publications of Gerald Midgley, Werner Ulrich and Derek Cabrera were the focus of these searches. In a second moment, in the search for aspects and practices of problem solving in a business environment, the main research bases used were Web of Science and Scopus from the use of keywords such as, for example, “Systemic Thinking”, “Critical Heuristics”, “Critical Practices”, “Systemic Intervention”, " Boundary Critique”, “Methodological Pluralism”, “Complex Problems”, “Business Management Philosophies” and “Business Management Methods”.

Thus, 41 publications were used to conduct this study. Figure 2 shows the number of publications obtained by approach.

It is worth noting that a pressing concern of the authors of this work was the construction of an intervention method aimed at companies and, as a result, the research focused on approaches directed towards the search for solutions to complex problems and continuous improvement.

Theoretical and Practical References

Critical Systems Heuristics

The CSH methodological approach presented by Ulrich (1983, 1987) seeks to address issues such as coercive social and organizational contexts, fundamental conflict among stakeholders, the diversity of underlying interests and the influence of power on systemic practices. Brings a practical approach grounded in boundary critique (Midgley et al. 1998; Midgley and PINZÓN 2011), which involves an unfolding process for systemic interventions that, from the consideration of different stakeholders’ points of view, promotes the inclusion of as many factors as possible to the analysis (SYDELKO et al. 2021).

Ulrich (1996) emphasizes that CSH seeks practical and rational solutions as of the promotion of critical systemic thinking by means of the systematic critique of frontiers to generate knowledge. In this sense, the author added a set of structured questions to the methodology aiming at greater practicality for application in real environments. Each question can and should be answered from different points of view, not only of the people involved, but also from the perspective of those not involved, but interested or potentially affected.

For the author the central concern of the methodology is to develop and pragmatize critical heuristics in the sense of enabling the transmission of ideas and possibilities among people, making their voices “competent”, as they should be considered as “’experts” on social issues in which they are involved. In this sense, critical heuristics has the ideal of empowering people in a practical way, proposing effective ways, from methodological tools of self-reflection and debate, even in circumstances of asymmetric distribution of knowledge, skills, and power.

Ulrich (2005) lists two foci for heuristics: (1) analysing the boundaries of current situations; and (2) supporting people to challenge the boundaries of others when they disagree with them. Thus, it is an approach specifically designed to support the process of making boundary judgments, in which those involved must identify and examine the “marginalized elements or aspects” by themselves and others, debate and challenge the elements they disagree with, and construct more appropriate, reasoned, and bounded arguments.

From the author’s perspective, marginalised elements or aspects are those characterised by disagreement, conflict, usually unstated or obvious, which may involve ethical or paradigmatic issues and thus remain “at the margins” of dialogues and discussions, because their effects, if not properly addressed pre-emptively, will generate more conflict than consensus, which will bring little or no effectiveness in the context of an intervention.

Jackson (2003) highlights that CSH is a practice-oriented methodology, which seeks to ensure that planning and decision-making include a “critical dimension”, promoting deeper questioning in various types of projects, aiming to explore and discover what interests and expectations are present.

Systemic Intervention

SI is a contemporary approach developed by Midgley (2000) to address problem situations, usually applied to support the intervention and action making process in governmental, non-governmental organisations, community management etc. It is a systemic practice consisting of three interrelated steps: (1) Critique: identification, analysis, understanding and definition of the boundaries with the inclusion, exclusion and/or marginalization of the components involved in the problem-situation, such as data, people, conditions etc.; (2) Judgement: research, critical evaluation and choice of the theories and/or methods to be applied; and, (3) Action: implementation of the chosen methods, definition and proposition of improvements, which must be significant and sustainable over time.

The author also stresses that the main added value of SI in comparison with previous systemic approaches is the synergy of “boundary critique” and “methodological pluralism”. According to the author the boundary critique should be the first activity of the intervention, from which boundaries and values should be explicitly explored from three basic perspectives: (1) of the problem-situation, seeking to understand which aspects are relevant for negative or below-desired results; (2) of the stakeholders, about who is directly or indirectly involved and/or affected and how; and, also, (3) of the relations between stakeholders, with the understanding of the power relations present, formal or not, possible conflicts and marginalized elements.

In this regard, Ufua, Papadoulos, and Midgley (2016) note that when dealing with multi-stakeholder problematic issues, there may be complexities and power relations that need to be investigated and considered. It may be the case that the main stakeholders in the intervention may be blind to relevant issues in this regard that may be part of the context to be addressed and understood.

For Midgley (2000), conflict between groups usually arises when they hold different ethical positions and therefore repeatedly make distinct boundary judgements. However, these judgements may be stabilised by social attitudes and rituals, and acceptance of stabilised boundary judgements tends to occur and therefore this should be a focus at the beginning of a systemic intervention.

Mingers and Brocklesby (1997) note that the essence of multimethodology is to use more than one methodology, or part of it, possibly from different epistemological paradigms, within a specific intervention. The authors also emphasise the attractiveness of using multimethodology in systemic practices by arguing about its potential in real-world problem situations, which are “inevitably highly complex and multi-dimensional” (MINGERS and BROCKLESBY 1997, p. 492).

In the view of Midgley, Nicholson, and Brennan (2017) multimethodology is a practice of using methods from two or more different paradigmatic sources in a study. The authors emphasize that its application involves the possibility of acting at two levels: (a) from the perspective of the methodology it is possible to obtain methodological ideas from other authors and sources and, from this, develop a new one; (b) in the method, one can apply several of them or part of them to obtain specific results without necessarily changing them.

Distinctions, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives Theory

For Cabrera (2004) “Distinctions, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives” should be considered “universal patterns” to the process of structuring information and thinking, and people, if they learn to use them in an explicit and structured way, can improve their systemic thinking skills. Moreover, these patterns should not and cannot be considered isolated elements, that is, it is the dynamic behaviour of the rules acting together that provides a contribution to concept knowledge (Cabrera 2006; Cabrera, D.; Cabrera, L.; Midgley, 2021).

In Cabrera and Colosi’s (2008) view, the DSRP is a universal model of thought patterns, not just a set of universal elements, but a set of interaction patterns, making up the so-called “thought patterns model”. Cabrera, D., Cabrera, L., and Powers (2015) argue that these patterns and their interrelated elements are the foundations of systems thinking, and that although the underlying rules are simple, their combination and repetition can produce results of almost infinite complexity.

This dynamic is presented by Cabrera (2006) as a “minimal concept theory”, or a “universalization theory” of systemic thinking. For the author, systemic thinking would be an emergent property of the application of DSRP, constructed by a group of people in each system from the study of a specific problem-situation, because the types of distinctions, organizations, relationships, and perspectives recognized depend on the system of interest and the situation about which one is dealing.

The development of continuous systemic thinking learning, according to Cabrera, D. et al. (2018), can also be the key to structuring, problem solving and sustainability in environments called “Complex Adaptive Systems”, characteristic of an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world. In this context, the authors present simple rules for the development of systemic thinking in a collective and organizational perspective, the VMCL (“Vision, Mission, Culture/Capacity, and Learning”).

While DSRP theory is designed from the strategic perspective of developing the individual’s metacognition in systems thinking, VMCL is about simple patterns that can be applied to leverage learning in systems thinking in an organisation or group of individuals. In this case the rules also operate in pairs and in an interrelated way, with learning leading to culture and capability, and mission to vision achievement. In this way, the concept can be applied to develop systemic thinking in an organization for the sake of its growth and sustainability (Cabrera, D.; Cabrera, L., 2019).

Also, for the authors, the influence and power of leadership for the application of VMCL rules are fundamental and indispensable factors, from the understanding of the strategy called NFST (“Naysayers, Fence-sitters, Supporters, and Thought leaders”). In this sense, the leadership has the role of interacting with the group and with the organisation itself in a proactive way by explaining the objectives (the vision), disseminating the rules (the mission), selecting and empowering agents and, from this, building a culture to support the shared learning of the organisation’s “Mission-Vision”. Further, the authors point out that VMCL and NFST are evolving models that promote systems thinking by developing organisations in adaptive learning and can help practitioners for the collective good.

Applications in the Enterprise Environment

Several approaches and methods developed for the systemic practice in corporate and business environments are found in the literature. Midgley (1997) points out that the methodological approach to be developed for a systemic intervention depends fundamentally on the context and the skills, competences, and decisions of the mediator, usually in interaction with the others involved. Table 1 presents examples of SI, CSH and DSRP applications in the business environment.

Slotte (2006) proposes a form of intervention based on the SI with emphasis on dialogue with stakeholders from the application of dialogue methods with a view to overcoming individual and social barriers to share meanings, values and understanding of the needs and involved aspects of the intervention.

Midgley and Shen (2007), developed the Buddhist Systems Methodoly (BSM), a systemic methodology resulting from the synergy of the Buddhist cultural model with the IS idealised to support problem solving in Taiwanese organisations. BSM uses SI application activities and 36 questions based on Buddhist concepts during the intervention process.

Barros-Castro, Midgley, and Pinzón (2015) built an intervention approach based on a typical SI approach considering a set of interrelated questions to promote boundary reflections about the problem and stakeholders.

Ufua, Papadoulos, and Midgley (2016) developed the Systemic Lean Intervention (SLI), a methodology aimed at the effective participation of external stakeholders in the intervention process for the collaborative development of improvements. The methods used include semi-structured interviews, participatory observation, boundary diagrams, workshops, conceptual modelling, and rich pictures.

Cabrera, D. et al. (2018) developed a systemic intervention approach for organizational design and change from the application of the VMCL patterns and the NFST strategy, aiming to stimulate learning in systemic thinking and leadership development. The DSRP and VMCL patterns have also been applied at Zuora, a US enterprise software company (CABRERA and CABRERA 2018) and at General Electric (CABRERA et al. 2018b).

Castellini and Paucar-Caceres (2019) built an approach that integrates methodologies from the combination of traditional hard Operational Research methods, problem structuring methods and quality management tools for application in companies.

However, these conceptual and methodological aspects present in the approaches and practices verified may be extremely relevant to promote the critical-systemic practice in a structured and systematic way in companies.

In this sense, the contribution of this work is the construction of a hybrid intervention method based on aspects present in SI, CSH and DSRP.

The activities of Critique, Judgement and Action, the application of boundary critique to analyse the problem situation, identify and choose methods, devise methodologies, evaluate and outline improvement actions that are meaningful to the outcomes and sustainable in the long term are important aspects present in Midgley’s SI (2000) for the practice of systemic interventions in companies.

The construction of heuristics structured in the perspective of Ulrich’s CSH (1983, 1987, 1996) can enable the promotion of boundary critique in a business environment, in a simple and organized way.

The use of universal thinking patterns for the promotion of systemic thinking, both in the individual perspective with DSRP (CABRERA 2004, 2006) and group perspective with VMCL (Cabrera et al. 2018; CABRERA, D.; CABRERA, L., 2019), seems to be a viable way to promote adequate organizational growth aimed at continuous improvement.

Finally, other aspects found in examples of systemic approaches can be incorporated for the construction of an effective intervention method in business environment, such as: the promotion of dialogue between stakeholders (SLOTTE 2006; BARROS-CASTRO et al. 2015), the importance of leadership development (CABRERA and CABRERA 2018; CABRERA et al. 2018b; CABRERA et al. 2018b) and the need for synergy between cultural aspects specific to systemic paradigms (MIDGLEY and SHEN 2007; UFUA et al. 2016; CASTELLINI and PAUCAR-CACERES 2019).

Systemic Business Intervention Method

Conceptual and Methodological Approach

Systemic Business Intervention (SBI) brings an intervention approach based on systemic and business management theories, concepts, and practices. To deal with complex business problems, the proposed approach seeks to promote the understanding of each problem-situation in a comprehensive way, always seeking to understand it as a system in interaction with others, as it is represented in Fig. 3.

Thus, each problem situation should be seen as a system, composed of several elements (human, material, economic, social, ethical, etc.), which is inserted and interacts with other systems, internal and/or external to the company. The combination of these elements makes up the system of the problem situation that should be treated by SBI.

As for the methodological structure, the SBI method presented in Fig. 4 is composed of a preliminary stage and other three stages, based on SI activities. It is supported on four “pillars” and provided with critical heuristics to promote boundary critique during the intervention from the so-called “Critical Heuristics Quiz – CHQ”.

Support Pillars

With these pillars we seek to establish aspects that should be considered for the promotion of the practice of dialogue and boundary critique, and the formation of leaderships in the sense of building an environment where systemic thinking can be learned and constantly developed in favour of the solution of complex problems and the search for the realisation of the “Mission-Vision” of the company.

The pillars Leadership and Dialogue represent essential characteristics for the practice of NSDI, being indispensable for the dissemination of the DSRP thought patterns through effective and constant dialogue, supported by active leadership, for the creation and development of a culture of systemic thought and critical thinking of boundaries.

The Critical Thinking aims to highlight the importance and relevance of its declared and effective practice in interventions. This pillar should be a “flag” in the promotion of the methodology in the company, and mediators, leaders and managers should stimulate and encourage others in the effective practice of exploring and discussing limits and marginalised aspects throughout the intervention.

Finally, the Systemic View pillar is justified by the strategic need to carry out the stages and steps guided by its promotion and emphasis during the interventions. Managers, leaders, mediators, and others involved should practice and stimulate systemic vision in reflective practice and dialogue.

Critical Heuristics Quiz

The role of the CHQ is to support the SBI intervention method in the practice of vision and critical and systemic thinking in a structured and explicit way using 42 questions distributed in the following three stages throughout the intervention. To build the CHQ we used the references highlighted in Table 2. The suggested questions were designed for each stage and associated steps.

It is important to note that the questions should be used as a guide, and it is not mandatory to have defined and specific answers. Interviews, forms, meetings, and dynamics may be used, which may be carried out individually or in groups.

Stages and Steps

Both the Preliminary Stage and the steps of the other stages should be carried out in sequence. Each step is structured as a process, composed of inputs, tools and techniques; and outputs, as detailed in Table 3.

Preliminary Stage: Assessment of Anomalies

Anomaly assessment can be carried out proactively or reactively, i.e., forums can be promoted for the identification of potential anomalies or starting from pre-existing anomalies.

A team from the sector where an anomaly was identified, preferably led by the sector manager, should evaluate whether the anomaly presents characteristics of a “complex problem”. If necessary, employees from other sectors or even external stakeholders, such as suppliers, customers, partners, and the community, may be involved.

To perform this step, we recommend meetings, interviews or forms supported by questions suggested in Table 4 for the classification of anomalies.

If the answers to the first six questions in Table 4 were all positive or conflicting, the problem is considered “Complex”. All other responses and information collected should be recorded, and the call to Step 1 will be based on question 7.

If the anomaly is not considered a complex problem by the team, the manager should take any other course of action, since the SBI would have little to add in this scenario and may even bring less agility to the solution of the problem.

Stage 1: Critique - Problem Situation Analysis

In Step 1.1, those involved should reflect on the aspects involving the problem, their interests, influence, and role in relation to the problem-situation and the intervention itself, coordinated by a leader designated for this step, who can be the sector manager, already involved in the previous step, or another, if necessary. As tools and techniques, meetings or interviews are suggested, supported by the CHQ questions specific to the step (Table 1).

The main outputs of the step are common aspects of the problem-situation, for which there is consensus; marginalized aspects, which generated disagreement and/or conflicts; the choice of the designated mediator, who will be responsible for conducting the next steps.

In Step 1.2, based on the list of marginalised aspects, the designated mediator should gather those involved for reflection forums and specific and in-depth discussions. As tools and techniques, it is suggested to use meetings with the support of the CHQ questions specific to the step. In this step, interviews or individual application of the quiz is not recommended, since dialogue and group discussion about marginalized aspects are essential in promoting greater understanding of the problem-situation.

The expected outcome of this step is a greater understanding of the aspects involved in the problem situation and the consolidation of the list of relevant aspects. Resources such as audio and video recording are recommended so that all relevant information is recorded.

Stage 2: Judgement - Intervention Planning

The research and choice of methods in Step 2.1 should be made based on the relevant aspects of the problem situation. As tools and techniques there are research tools, meetings and the CHQ. Search engines and related software are suggested.

The mediator should promote meetings to discuss the options identified. The output of this step is the chosen methods duly justified and related to the relevant aspects.

In Step 2.2, with the chosen methods duly justified, the mediator should prepare the intervention plan based on multi-methodology concepts. Methods can be used in their standard format or with adaptations. Process modelling can be carried out, for example, using standards or software available in the company or on the Web.

With the intervention plan modelled, the mediator should hold a meeting and supported by the specific CHQ questions for the step, discuss and assess its feasibility of application, as well as verify needs. The outputs of this step are the consolidated intervention plan, those responsible and involved in its implementation and the means and methods of dissemination to stakeholders.

Stage 3: Action - Implementation and Evaluation of Intervention

In Step 3.1, the intervention plan should be implemented. The suggested tools and techniques are managerial techniques such as meetings, dynamics, and workshops.

The expected outputs are a list of potential improvements and preliminary data related to each of them, such as costs, deadlines, resources, expected results, people responsible, etc. The mediator should actively support the implementation process of the intervention plan, seeking to ensure its proper implementation by constantly checking with those responsible.

Step 3.2 involves a critical assessment of the potential improvements identified to ensure that only systemically desirable, culturally feasible and with the potential for significant and sustainable long-term effects are proposed.

The tools and techniques to be used are meetings supported by specific CHQ questions for the step and techniques for planning the improvement actions. The outputs of the step are the consolidated list of recommended improvements and an action plan with responsible parties.

Step 3.3 aims to perform a critical and reflective appreciation about the SBI application process, with the objective of generating information and providing feedback to the mediator, those involved and the company management and, thus, enable the method’s improvement.

In the vision of these authors, this is a fundamental need, because the method must adjust to the organisational culture of the company, supporting the continuous improvement process and the organisational learning and development in the solution of problems.

The tools and techniques to be used are meetings, interviews, or forms, supported by specific CHQ questions. The desired outputs are positive and negative points, lessons learned, impressions and suggestions.

Conclusions

The main objective of this work was to present and base a method of critical-systemic intervention adherent and adapted to the culture and needs inherent to the business environment.

To this end, the theoretical framework explored concepts, theories and systemic, critical, and business management practices used by companies to treat problems and promote the continuous improvement of their processes.

The fundamental aspects and activities of the Systemic Intervention, the structured critical analysis of the Critical Systems Heuristics and the DSRP thought patterns were used in the foundation and structuring of the proposed intervention method, with the identification of stages, application elements and supporting pillars: Leadership; Dialogue; Systemic Thinking; and Critical Boundary.

The SBI method was grounded and detailed. Birnbaum quoted by Davis, Dent, and Wharff (2015, p. 83) notes that “a model is an abstraction of reality that, if good enough, allows us to understand (and sometimes predict) some of the dynamics of the system it represents”.

In this sense, as a result was obtained a method of critical-systemic intervention hybrid and idealized to support organizations in obtaining meaningful solutions to the results and sustainable in the long term and, moreover, that promotes learning and continuous development of organizational culture in systems thinking.

It is worth noting that an application of the developed SBI method is underway in a real environment and will be duly presented once finalised. Some points to be tested and evaluated in the pilot application should be highlighted: the real freedom that the company will give to those involved to practice boundary critique; the quantity of questions of the CHQ aiming at an adequate balance for the efficiency of the critical heuristics along the intervention; the potential for individual and organizational learning in systemic thinking from the DSRP and the VMCL; the need to create standards, forms, procedures among other necessary resources for a more efficient intervention; the feasibility of training internal mediators in the company.

Finally, it is important to emphasise that the aim is not to adapt the company to the SBI, but that the method should be applied in such a way as to add perceived value in the solution of complex problems and continuous improvement of results.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Alves EA, C. (2021) O PDCA como ferramenta de gestão da rotina. In: Congresso Nacional De Excelência Em Gestão, 11., 2015, Rio de Janeiro. Anais eletrônicos… Evento online: CONEG, 2015. Disponível em: https://www.cneg.org/anais/artigo.phpe=CNEG2015MBA&c=T_15_017M. Acesso em 21

Barros-Castro RA, Midgley G, Pinzón L (2015) Systemic intervention for computer-supported collaborative learning. Syst Res Behav Sci v 32(1):86–105

Cabrera D (2004) Distinctions, systems, relationships, perspectives: the simple rules of complex conceptual systems. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283046472_distinctions_systems_relationships_perspectives_the_simple_rules_of_complex_conceptual_systems. Acesso em 22 set. 2022

Cabrera D (2006) Boundary critique: a minimal concept theory of systems thinking. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237724411_Boundary_Critique_A_ Minimal_Concept_Theory_of_Systems_Thinking. Acesso em 15 set. 2021

CABRERA D (2019) CABRERA L. What is systems thinking? In: SPECTOR M, LOOKEE B, Childress M (eds) Learning, Design, and Technology. Springer, Cham, pp 1–28

Cabrera D, Cabrera L (2018) Systems leadership: designing an adaptive organization using four simple rules to thrive in a complex world. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349868871_Systems_Leadership_designing_an_adaptive_organization_using_four_simple_rules_to_thrive_in_a_complex_world. Acesso em 05 ago. 2021

Cabrera D, Cabrera L, Powers E (2015) A unifying theory of systems thinking with psychosocial applications. Syst Res Behav Sci v 32(5):534–545

Cabrera D, Cabrera L, Sokolow J (2018b) Systems thinking for transformation: GE evolves for the digital industrial era. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349868408_Systems_Thinking_for_Transformation_GE_Evolves_For_The_Digital_Industrial_Era. Acesso em 05 mar. 2021

CABRERA D, COLOSI L (2008) Distinctions, systems, relationships, and perspectives (DSRP): a theory of thinking and of things. Evaluation and Program Planning, v. 31, n. 3, p. 311–317,

Cabrera D, Colosi L, Midgley G (2021) The four waves of systems thinking. In: cabrera D, Cabrera L, Midgley G (eds) Routledge handbook of systems thinking. Routledge, London, pp 1–44

Cabrera D, Cabrera L, Powers E, Solin J (2018) Applying systems thinking models of organizational design and change in community operational research. Eur J Oper Res 268(3):932–945

Castellini MA, Paucar-Caceres A (2019) A conceptual framework for integrating methodologies in management: partial results of a systemic intervention in a textile SME in Argentina. Syst Res Behav Sci v 36(1):20–35

Checkland PB (1981) Systems thinking, systems practice. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Churchuman C (1971) W. Introdução à teoria dos sistemas. Editora Vozes, São Paulo

Córdoba JR, Midgley G (2008) Beyond organizational agendas: using boundary critique to facilitate the inclusion of societal concerns in information systems planning. Eur J Inform Syst v 17(2):125–142

Davis AP, Dent EB, Wharff DM (2015) A conceptual model of systems thinking leadership in community colleges. Systemic Pract Action Res v 28(4):333–353

Espejo R et al (1996) Organizational transformation and learning: a cybernetic approach to management. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Imai M (1994) Kaizen: a estratégia para o sucesso competitivo. Iman, São Paulo

Jackson MC (2003) Systems thinking: creative holism for managers. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

MacDuffie JP (1997) The road to root cause: shop-floor problem-solving at three auto assembly plants. Manage Sci 43(4):479–502

Martinelli DP (2010) Negociação empresarial: enfoque sistêmico e visão estratégica, 2 edn. Santana de Parnaíba: Editora Manole,

Martinelli FB (2009) Gestão da qualidade total. Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro

Maximiano ACA (2005) Teoria geral da administração: da revolução urbana à revolução digital. Atlas, São Paulo

Midgley G (1997) Developing the methodology of TSI: from the oblique use of methods to creative design. Systems Practice, v. 10, n. 3, p. 305–319,

Midgley G (2000) Systemic intervention: philosophy, methodology, and practice. Kluwer/Plenum, New York

Midgley G, Munlo I, Brown M (1998) The theory and practice of boundary critique: developing housing services for older people. J Oper Res Soc v 49(5):467–478

Midgley G, Nicholson J, Brennan R (2017) Dealing with challenges to methodological pluralism: the paradigm problem, psychological resistance, and cultural barriers. Industrial Mark Manage v 62:150–159

Midgley G, Pinzón L (2011) The implications of boundary critique for conflict prevention. J Oper Res Soc v 62:1543–1554

Midgley G, Shen CY (2007) Toward a Buddhist systems methodology 2: An exploratory, questioning approach. Systemic Practice and Action Research, v. 20, n. 3, p. 195–210,

Mingers JC, Brocklesby J (1997) Multimethodology: towards a framework for mixing methodologies. Omega, v. 25, n. 5, p. 489–509,

Mingers JC, Rosenhead J (2004) Problem structuring methods in action. Eur J Oper Res v 152(3):530–554

Noblat PLD, Souza BCG (2015) de; Barcellos, C. L. K. Análise e melhoria de processos: metodologia MASP. ENAP. Disponível em: https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/bitstream/1/2174/1/MASP%20-%20M%C3%B3dulo%20%281%29.pdf. Acesso em 23 out. 2021

Rosenhead J, Mingers J (2001) Rational analysis for a problematic world revisited. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Slotte S (2006) Systems sensitive dialogue intervention. Systems Research and behavioral science, v. 23, n. 6, p. 793–802,

Sydelko P, Midgley G, Espinosa A (2021) Designing interagency responses to wicked problems: creating a common, cross-agency understanding. Eur J Oper Res v 294(1):250–263

Ufua D, Papadoulos T, Midgley G (2016) Systemic lean intervention: enhancing lean with community operational research. Eur J Oper Res v 268(3):1134–1148

Ulrich W (1983) Critical heuristics of social planning: a new approach to practical philosophy. Paul Haupt, Bern/Stuttgart

Ulrich W (1987) Critical heuristics of social systems design. Eur J Oper Res v 31(3):276–283

Ulrich W (1996) A primer to Critical Systems Heuristics for action researchers. Disponível em: https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1996a.pdf. Acesso em 11 jul. 2021

Ulrich W (2005) A brief introduction to critical systems heuristics (CSH). Disponível em: http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2005f.pdf. Acesso em 13 jul. 2021

Womack JP, Jones DT (1996) Lean thinking: banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. Touchstone Books, Cambridge

Womack JP, Jones DT, Ross (1990) D. A Máquina que mudou o mundo. Campus, Rio de Janeiro

Funding

This research was funded in part by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Financial Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author Fabrício wrote the main text of the manuscript, prepared the figures and tables. The author Carmen revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Parrilla, F.R., Neyra Belderrain, M.C. Systemic Business Intervention to Treat Complex Problems in Companies. Syst Pract Action Res 37, 441–457 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-023-09662-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-023-09662-y