Abstract

Research on attitudes toward racial policies has often been limited to a single racial group (e.g., either Whites or Blacks). These studies often focus on the role of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness, but this work has operationalized these concepts in different ways when studying White or Black respondents. Using data from a study in which Whites and Blacks living in Chicago were asked their attitudes toward affirmative action, we build on this body of research by using common measures of self-reported self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness to predict support for affirmative action. We also examine whether the effects of these determinants are moderated by political ideology. We find that self-reported self-interest influences support for affirmative action among Black conservatives, but not among other respondents. Self-reported group-interest, however, has significant effects that differ between Blacks and Whites and across liberals, moderates, and conservatives. We also find that race consciousness affects respondents’ attitudes toward affirmative action, but that this effect is moderated by political ideology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Affirmative action has been a controversial policy since its inception in the 1960s. Supporters of affirmative action argue that the policy is required to address ongoing discrimination toward racial minorities. Opponents claim the policy violates principles of fairness and meritocracy. In the realm of popular discourse, the issue of affirmative action is couched within a larger political agenda. As a result, the degree to which organizations and workplaces are held accountable to, or banned from using, affirmative action varies from one political regime to the next. In 2003, for example, the Supreme Court ruled against an affirmative action program at the University of Michigan. Just over a decade later, the Supreme Court upheld an affirmative action policy at the University of Texas. While the structure of the affirmative action programs at these two universities was different, the regular flow of such cases heard in the Supreme Court illustrates the ongoing political contention around racial policy—where issues of fairness and meritocracy confront the need to address racial discrimination.

Debates around affirmative action in public discourse are mirrored by disagreements among researchers over the determinants of individuals’ support for racial policies. While some researchers argue that values such as political orientation are the primary determinants of support (Sniderman & Carmines, 1997; Sniderman, Crosby, & Howell, 2000; Son Hing, Bobocel, & Zanna, 2002), others contend that opinions about racial policy reflect racial attitudes such as racial resentment or racism (Kinder & Sanders, 1996; Rabinowitz, Sears, Sidanius, & Krosnick, 2009; Sears, Van Laar, Carrillo, & Kosterman, 1997; Shteynberg, Leslie, Knight, & Mayer, 2011; Tuch & Hughes, 2011). Still, another body of research argues that racial differences in support for racial policies are predominantly explained by differences in individuals’ personal- or group-interest (Beaton & Tougas, 2001; Bobo, 1998; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Kravitz & Platania, 1993; Sidanius, Pratto, & Bobo, 1996).

Taken as a whole, the body of research examining attitudes toward affirmative action suggests that individuals’ opinions on this topic are highly complex. Yet, there remains ample room to explore that complexity. One underexplored area involves comparing the predictors of attitudes toward affirmative action between Blacks and Whites, rather than focusing on explanations for mean differences in attitudes across racial groups. In order to do that, we focus on variables that can be assessed comparably across racial groups. Research on self- and group-interest has often assumed that racial differences in support for affirmative action policies (AAPs) are due to individuals’ belief in whether the policy will benefit them or their race group, with much research showing that racial group-interest is more influential in policy attitudes than self-interest (Bobo, 1998; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Kravitz & Platania, 1993; Sears & Funk, 1990). Few studies on this topic (e.g., Lowery, Unzueta, Knowles, & Goff, 2006) have explicitly asked respondents if they believe the policy will affect them or people of their race, and it remains rare for studies to use common measures of self-/group-interest across respondents of different racial groups. In this study, we examine within-race variation in feelings of self- and group-interest by using a self-reported common measure that asked respondents if AAPs affect them or their race group. By using a self-reported measure, our approach avoids the assumption that all people of a certain race share the same feelings of self- or group-interest and allows us to estimate the effect of these variables as they are perceived by respondents.

Our study also examines whether respondents’ self-reported belief that their race affects the way they are treated, a variable we call race consciousness, influences their attitudes toward affirmative action. Previous research has found that race consciousness plays a large role in shaping both Blacks’ (Dawson, 2001; Schmermund, Sellers, Mueller, & Crosby, 2001; Simien & Clawson, 2004; Sullivan & Arbuthnot, 2009; Tate, 2010) and Whites’ policy attitudes (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Schiffhauer, 2007; Iyer, Leach, & Crosby, 2003; Knowles, Lowery, Shulman, & Schaumberg, 2013; Knowles, Lowery, Chow, & Unzueta,2014; Lowery et al. 2006; Powell, Branscombe, & Schmitt, 2005). However, these studies have generally examined Black and White respondents separately using distinct metrics of race consciousness. Here, we operationalize race consciousness using a common variable for Blacks and Whites measuring the extent to which respondents believe they are treated differently because of their race. We then investigate the relationship between race consciousness and policy attitudes for both Blacks and Whites.

In addition to comparing the effects of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness on attitudes about AAPs among Blacks and Whites, our study also advances research on attitudes toward affirmative action by examining whether political ideology moderates the effect of policy attitude determinants. Previous research on racial policy attitudes has found different effects of racial prejudice (Sniderman et al., 2000) and racial resentment (Feldman & Huddy, 2005) for conservatives and liberals. Yet, we still do not know if other determinants, such as self-interest, group-interest, or race consciousness, are moderated by political ideology. Extending previous research, we examine whether the effects of these variables are different for Black and White conservatives, moderates, and liberals.

In this paper, we first review the literature on political ideology, self- and group-interest, and race consciousness as predictors of support for AAPs. Next, we present our hypotheses, followed by a description of our data and analytic plan. We then highlight our findings. Self-interest only affects the policy attitudes of Black conservatives. Group-interest, however, has significant effects for both Black and White respondents. Furthermore, these effects are moderated by political ideology among Blacks. Finally, we find that race consciousness is also a significant predictor of support for affirmative action among Whites and Blacks and that this variable is moderated by political ideology.

Antecedents of Support for Affirmative Action

In this section, we review the individual characteristics that have been found to predict support for racial policies, including political ideology, self- and group-interest, and race consciousness. We also point out how our study contributes to existing frameworks for understanding racial policy attitudes. Finally, we discuss evidence of political ideology not as a predictor of support for racial policies, but as a possible moderator of other predictors.

Principled Politics

Several scholars have argued that political conservatism is a central determinant of racial policy attitudes (Kuklinski et al., 1997; Sniderman & Carmines, 1997; Sniderman et al., 2000). These researchers argue that opposition to racial policies is based on the perception that these policies give an unfair advantage to racial minorities, rather than any negative sentiment or racial attitude.

Self-interest

Researchers have also argued that policy opinions are influenced by individuals’ self-interest. The premise behind this perspective is that individuals who personally benefit from racial policies will be more likely to support them. Consistent with the self-interest hypothesis, previous research has found that views on affirmative action are divided along racial lines, with Whites largely opposing and minorities mostly supporting such policies (Bobo, 1998; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Steeh & Krysan, 1996). One limitation of this line of research is that it often assumes that racial differences are due to individuals’ belief that they will benefit or be disadvantaged through the policy. By using race as a proxy for feelings of self-interest, we are unable to determine whether some Whites, for example, believe they will benefit from the increased diversity that affirmative action programs may generate. Alternatively, this approach also obscures the fact that many Blacks may feel they don’t benefit from policies like affirmative action because such programs may reinforce negative perceptions that their accomplishments are due to organizational policies rather than individual merit. Also raising concerns about this assumption, research examining self-interest across policy domains has found that this variable is a much weaker predictor of attitudes than group-interest (discussed below) and attributes associated with individuals’ racial attitudes (Bobo, 1998; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Citrin, Green, Muste, & Wong, 1997; Sears, Lau, Tyler, & Allen, 1980; Sears & Funk, 1990).

Moving forward, it is important to reconsider the way we determine self-interest in racial policy attitudes. Previous work examining self-interest has suffered from limited construct validity. Racial identification (Bobo, 1998; Kravitz & Platania, 1993) and economic standing (Bobo & Kluegel, 1993) may serve as strong indicators of whether a respondent will benefit from certain policies, but do not measure respondents’ personal belief in whether they will benefit. Here, we build from previous examinations of self-interest by using a measure high on construct validity that captures respondents’ self-reported feelings of whether they are personally affected by affirmative action.

Group-Interest

Studies examining the relationship between personal interest and policy attitudes have generally found that individuals’ feeling of group-interest—the belief that policies will benefit their racial group as a whole—are more influential in policy attitudes than feelings of self-interest that the policy will benefit them personally (Bobo, 1998; Sears & Funk, 1990). Much of this research has examined Whites’ opposition to racial policies such as affirmative action. These studies show, for example, that Whites are more likely to oppose AAPs when these policies are targeted toward improving racial diversity as opposed to gender diversity (Beaton & Tougas, 2001; Sidanius et al., 1996). Such findings suggest that Whites oppose affirmative action not because of the structure of policies, but because their race group does not benefit.

As with previous research on self-interest, there is ample room to expand upon the construct of group-interest. As noted, previous research has used respondent race and the race target of policy to determine the effects of group-interest (although see Lowery et al., 2006 for an exception focusing on Whites). Few studies have measured respondents’ personal belief in whether their race group is affected by policy. Furthermore, we are aware of no studies to date that have used a common metric of group-interest across race groups to compare the effects of this attribute on policy attitudes. Here, we build from studies on group-interest by using a measure high on construct validity that captures both Black and White respondents’ self-reported belief in whether AAPs affect their race group.

Race Consciousness

Previous research has also examined the role of racial attitudes, racial identity, and race consciousness in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward public policy. Several scholars have found that various forms of racial prejudice are strongly associated with opposition toward racial policies (Kinder & Sanders, 1996; Kinder & Sears, 1981; Rabinowitz et al., 2009; Sears et al., 1997; Shteynberg et al., 2011; Tuch & Hughes, 2011). One growing area of research in this field examines how feelings of racial identity or race consciousness affect policy attitudes. These qualities are distinct from other racial attitudes in that they do not pertain to an individual’s feelings toward members of other race groups. Instead, they relate to the individuals’ beliefs in whether their race has impacted their life.

Research on race consciousness and policy attitudes has generally examined Blacks and Whites separately. Among work focusing on Black political opinion, Dawson (2001) finds that Black political opinion is shaped by feelings of shared fate with other Blacks. The continued economic, geographic, and social isolation of Blacks creates the context for this group to establish a cohesive set of policy positions based on the shared experience of racial marginalization. More recent research supports Dawson’s findings, showing that Blacks’ political opinions are influenced by identification with others of the same race group (Simien & Clawson, 2004; Sullivan & Arbuthnot, 2009; Tate 2010).

There has also been a growing body of research examining Whites’ race consciousness and feelings of racial identity. Studies taking place over the past two decades have found that Whites’ policy positions are increasingly shaped by their feelings of whiteness (Goren & Plaut, 2012; Jardina, 2019; Knowles et al., 2013; Knowles & Peng, 2005). Those who feel they are increasingly alienated on the basis of their race in an increasingly diverse society are more likely to oppose racial policies such as affirmative action and immigration (Goren & Plaut, 2012; Jardina, 2019; Lowery et al., 2006). Meanwhile, Whites who report awareness of racial privilege tend to have greater support for policies aimed at improving diversity and racial equity (Iyer, Leach, & Crosby, 2003; Knowles et al., 2014; Powell, Branscombe, & Schmitt, 2005).

Race consciousness has been found to play a large role in shaping policy attitudes for both Blacks and Whites. Yet, previous research has tended to focus on these groups separately, using race-specific items to measure race consciousness. Dawson’s conclusions on Blacks’ feelings of shared fate, for example, are partly based on analyses using a series of items measuring respondents’ exposure to Black information networks such as Black TV stations or books from Black authors. Schmermund et al. (2001) used the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers et al., 1997) which includes questions about being an oppressed minority—items that are valuable, but not applicable for research on White respondents. Research on Whites has also used race-specific measures. In her study of Whites’ political attitudes, Jardina (2014, 2019) used an item that measured the importance of whiteness to respondents’ personal identity—a measure that is not directly transferrable to other race groups. We agree that there is value in using race-specific items, since racial identity is substantively different across race groups. However, limiting our analysis of race consciousness to only race-specific variables threatens to constrain our focus to race as an individual characteristic rather than one that is also maintained through social interactions and structures. In this study, we use a common measure of race consciousness that is worded the same way for Black and White respondents. Using a single measure allows us to determine how this characteristic may operate differently between race groups.

Political Ideology as a Moderator

A great deal of debate has taken place between scholars who argue about the relative importance of political ideology (Kuklinski et al., 1997; Sniderman & Carmines, 1997; Sniderman et al., 2000) and those underscoring the influence of racial attitudes, self-interest, and group-interest (Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Sidanius et al., 1996). This work largely tests these variables as competing predictors of support for racial policies. In contrast, a growing body of evidence suggests that in addition to predicting support for racial and nonracial policies, political ideology may also influence how policy positions are formed. Consistent with this, studies focusing on support for nonracial policies have found that determinants of policy attitudes are often moderated by political ideology (Malka & Lelkes, 2010; Rudolph & Evans, 2005).

In the realm of racial policies, only a few researchers have begun to explore this possibility, but the findings in these studies suggest that political ideology may act as an important moderator. For example, Sniderman et al. (2000) found that prejudice has much stronger negative effects on racial policy support for liberals than conservatives. In direct contrast to Sniderman and colleagues, however, Feldman and Huddy (2005) found that feelings of racial resentment have a much stronger negative effect on support for racial policies for White conservatives than liberals. Other research focusing on Whites’ race consciousness suggests that feelings of White racial identity may be shaped by political ideologies related to feelings of national pride (Goren & Plaut, 2012; Knowles & Peng, 2005). Collectively, these studies suggest that conservatives, moderates, and liberals may come to different conclusions based on a similar set of criteria. We further test this assumption in our investigation of racial policy attitudes by assessing whether the effects of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness are moderated by political ideology.

The Current Research

In each of the above sections, we have noted how our study makes a unique contribution to research on attitudes toward racial policy. By using self-reported measures of self- and group-interest, examining the effects of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness for both Blacks and Whites, and testing for the moderation of key determinants by political ideology, our study builds directly from previous research by further investigating the complexity of racial policy attitudes. We next lay out our specific hypotheses.

Hypotheses

Building on previous research, we focus on three sets of hypotheses that relate to the primary aims of this study. First, we examine whether self-interest—respondents’ belief that affirmative action affects them personally—influences support for these policies. Since minority or underrepresented groups are the intended beneficiaries of AAPs, Blacks may be more likely to feel they personally benefit, while Whites may have the opposite opinion. The effects of self-interest, however, may be different within-race groups depending on respondents’ political ideology. Self-interest may be more influential for Black conservatives than Black liberals, since conservatives would otherwise oppose affirmative action to be consistent with broader policy positions. The opposite could be true for White liberals, where those with high levels of self-interest may oppose affirmative action if they feel the policy hurts them personally, even though it goes against their political affinities.

H1a

The effects of self-interest will be largest for Black conservatives compared to moderates and liberals.

H1b

The effects of self-interest will be largest for White liberals compared to moderates and conservatives.

In addition to respondents’ belief that affirmative action affects them personally, feelings that the policy affects their race group as a whole may also influence their level of support. Our next set of hypotheses examines the role of group-interest in support for affirmative action policies. Because affirmative action is designed to be a restorative measure intended to curtail discrimination, we hypothesize that group-interest will be positively related to Blacks’ support of this policy. The opposite effect, however, may be observed for Whites who believe affirmative action affects their race group as a whole. Among Blacks and Whites, however, the effects of group-interest may differ by political ideology. Black conservatives with high levels of group-interest may be motivated to go against conservative policy agendas in order to support a policy that improves the condition of their race group. White liberals with high levels of group-interest, on the other hand, may be motivated to oppose affirmative action despite the fact that it is against policy positions mostly held by liberals.

H2a

The effects of group-interest will be strongest for Black conservatives compared to moderates and liberals.

H2b

The effects of group-interest will be strongest for White liberals compared to moderates and conservatives.

Our last set of hypotheses concerns the relationship between race consciousness and support for affirmative action. Both Blacks and Whites who believe that their race affects their day-to-day life may be more aware of racial inequality and, therefore, more supportive of affirmative action. The strength and direction of these effects, however, may differ by political ideology. Black liberals and moderates may associate race consciousness with a need for policy that addresses racial inequality, while Black conservatives may feel that racial policies should be minimized because they only exacerbate the salience of race. A similar effect may be observed among Whites, where liberals with high levels of race consciousness may view their lived experienced as being shaped by racial privilege, the presence of which necessitates affirmative action. White conservatives, on the other hand, may feel alienated because of their race and oppose affirmative action as a result.

H3a

Race consciousness will be negatively associated with support among Black conservatives and positively related to support for Black moderates and liberals.

H3b

Race consciousness will be negatively associated with support among White conservatives and positively related to support for White moderates and liberals.

Testing the relationship of political ideology, self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness to attitudes toward affirmative action among Blacks and Whites also allows us to compare how these predictors differ across race. Therefore, in addition to testing our hypotheses in the analysis below, we also report differences between Blacks and Whites in the determinants of policy attitudes.

Data and Sample

The data used here come from the 2008 Chicago Area Study which surveyed individuals’ attitudes toward government policies. The survey was administered between April 19 and August 16 of 2008 and was conducted by the Survey Research Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Chicago as well as several graduate students who were involved in a survey methods course. The survey was conducted via telephone by both professional interviewers and graduate students. Only respondents aged 18 years or older that resided in the city of Chicago were included in our sample. The sample was selected using random-digit-dialing methods. In instances where there was more than one eligible respondent in the household, interviewers used the Troldahl–Carter–Bryant selection method (Bryant, 1975) to select a respondent. The survey had a 20.3% AAPOR Response Rate 3, which was slightly above average response rates for telephone surveys during the year of data collection (Lavrakas et al., 2017). On average, interviews lasted about 24 min and were conducted in either English or Spanish. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Chicago approved all research activities related to this study.

Our analysis of support for affirmative action focuses on Black and White respondents included in the Chicago Area Study. Respondents with missing data on any focal variables were dropped from the sample. Our final sample includes 210 Black and 223 White respondents. The small number of Latino and other race respondents included in the original sample prevented us from extending our analysis to additional race groups. This sample of Chicago residents provides key insight into the study of attitudes toward racial policy and is ideal for this study’s aims. As one of the most diverse, yet most segregated, cities in the USA, racial politics are a constant issue in Chicago and something ordinary citizens are frequently exposed to. As a result, most individuals’ hold thoughtful positions on issues like affirmative action and are able to easily respond to questions about their feelings toward race-related topics. For these reasons, our sample of Chicago residents is able to provide key insight about how feelings of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness interact with political ideology to influence attitudes toward affirmative action.

Measures

Dependent Variable: Support for Affirmative Action Programs

To measure support for affirmative action programs, we use a dichotomous variable measuring whether respondents believe that affirmative action programs are still needed. During the interview, respondents were asked which of two statements was closer to their point of view:

Affirmative action programs are still needed to make up for the effects of discrimination against minorities and help reduce racial inequality

Affirmative action programs have gone too far in favoring minorities and should be phased out because they are unfair to Whites

Respondents selecting the first statement were given a value of 1, indicating that they support affirmative action programs. Respondents who chose the second statement were coded with a value of 0.Footnote 1 The question wording was intentionally designed to account for the fact that many Americans are misinformed regarding the definition of affirmative action programs (Crosby, Iyer, Clayton, & Downing, 2003). From their beginning, AAPs were intended to correct for the harmful effects of racial discrimination (Crosby, Iyer, & Sincharoen, 2006). Thus, continued support for AAPs should be grounded in the opinion that they are needed to adjust for racial discrimination (the first option), while opposition should be based on a belief that such adjustments are no longer needed (the second option). By rooting the question in the definition of AAPs, the wording also reduces social desirability to the extent that justifications are readily present for either opinion.

Political Ideology

We use a three-category variable to indicate whether respondents identified as liberals, moderates, or conservatives. On the survey, respondents were asked to rate their political views by choosing one of five options: very conservative, conservative, moderate, liberal, or very liberal. Respondents who chose the options ‘very conservative,’ and ‘conservative’ were identified as having a conservative orientation. Those who chose ‘moderate’ were placed in a single category as moderates. Respondents selecting ‘liberal’ or ‘very liberal’ were grouped together as liberals.Footnote 2

Relevance of AAPs to Respondents’ Self-interest

We use the same variable to measure the relevance of AAPs to both Black and White respondents’ personal lives. This item records the degree to which respondents believe they are personally affected by affirmative action. Our measure comes from a single question on the survey asking respondents ‘How much does affirmative action affect the way you live your life?’ Respondents provided one of five possible answers, ranging from ‘a great deal’ to ‘not at all.’ Answers were recoded to range from zero to one so that higher scores reflect greater levels of a belief that AAPs affect respondents personally. This item has been used in previous research examining the role of self-interest (Boninger, Krosnick & Berent, 1995; Holbrook, Sterrett, Johnson, & Krysan, 2016). By focusing on the relevance of AAPs to respondents’ self-interest, this variable provides a common measure that can be used for both Black and White respondents. Henceforth, we refer to this variable as ‘self-interest’ with an understanding that it measures the perceived relevance of AAPs to respondents’ personal lives.

Relevance of AAPs to Respondents’ Group-Interest

We examined the relevance of AAPs to respondents’ group-interest using an item that asked, ‘How much do affirmative action programs for Blacks and other minorities affect [respondent’s race] people?’ There were five possible response options ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘a great deal.’ Higher scores in this zero to one five-point scale reflect respondents’ perceived relevance of affirmative action to their race group as a measure of group-interest. As with our variable for self-interest, our measure of group-interest has been used in previous research examining policy attitudes (Allison, 2011; Boninger, Krosnick, & Berent, 1995; Holbrook et al., 2016). The fact that this item asks specifically about the effects of affirmative action for the respondents’ race group constitutes an innovation of this study where group-interest is measured as it relates specifically to affirmative action, rather than as a generalized attitude (Beaton & Tougas, 2001; Sidanius et al., 1996). Henceforth, we refer to this variable as ‘group-interest,’ while acknowledging that it more specifically measures respondents’ perception of the relevance of AAPs to their race group.

Race Consciousness

To measure race consciousness, we combined two survey items. The first measured respondents’ agreement with the statement ‘Being [respondent’s race] determines a lot how you are treated in this country.’ The second item recorded participants’ agreement with the statement, ‘Being [respondent’s race] determines a lot how you are treated in Chicago.’ Four possible response options were available for each item: Strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree. The mean of these two questions was calculated to create a measure of race consciousness (Cronbach’s alpha = .82).Footnote 3 Scores in this variable range from zero to one, with higher scores indicating increased agreement with the statements and, therefore, higher levels of race consciousness.

Control Variables

All models control for the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents’ age, gender, and years of education. We also control for respondents’ political party identification with a three-category variable indicating whether respondents identified as Democrat, Republican, or other/independent.Footnote 4 To control for racial attitudes, we draw insight from previous research suggesting that antipathy toward Barack Obama that remains after accounting for political ideology and party identification is largely due to racial sentiment (Knowles, Lowery, & Shaumberg, 2010; Piston, 2010) and include a variable measuring respondents’ feelings for Barack Obama on a five-point scale ranging from very negative (zero) to very positive (one). While a more direct measure of racial attitudes may have been useful, our survey did not include these types of questions, and we are skeptical such an item would have been beneficial because they are subject to social desirability bias.

Analytic Strategy

Throughout our analysis, we examine Blacks and Whites separately to assess differences and similarities between these two groups. We first review descriptive statistics for support of AAPs and our independent variables. Because our measure of race consciousness is unique and because race consciousness has rarely been measured in a sample that includes both White and Black respondents, we also explore the predictors of this variable for Whites and Blacks.

Next, we review logistic regression models predicting support for affirmative action separately for Blacks and Whites. For each group, our first model regresses support for affirmative action on political ideology and demographic control variables to test our hypotheses relating to political ideology. The second model adds the three variables measuring self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness as a predictors. In the third model, we interact political ideology with these three variables to test our hypotheses relating to the moderation effects of political ideology. After reporting the results for our sample of Black and White respondents, we then compare predictors of affirmative action between racial groups. All logistic regression models were performed using weights.

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 provides an overview of the descriptive statistics for key variables separately for Black and White respondents. Consistent with previous research (Bobo, 1998; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Steeh & Krysan, 1996), we find that Blacks are much more likely to support affirmative action than Whites. The overwhelming majority, 93%, of Blacks support affirmative action in this sample. Among Whites, there is a near 50/50 split.

Table 1 also shows that there is an equal proportion of Whites and Blacks who identify as moderate, with just over a third of respondents identifying with this category of political ideology. A significantly greater percentage of Whites (45%) identified as liberals, compared to 38% of Blacks (p < 0.05). Consequently, there is a greater percentage of conservatives among Blacks (26%) than Whites (20%) (p < 0.05). Beyond political ideology, there were also differences between these two race groups in several key independent variables. Blacks were, on average, higher on measures of self-interest (p < 0.001), group-interest (p < 0.001), and race consciousness (p < 0.001) than Whites. We also find that Whites tend to have more years of education (p < 0.001), and are more likely than Blacks to identify as Republican (p < 0.001) or as independent/other political party (p < 0.001). Blacks reported higher average scores than Whites in support for Barack Obama (p < 0.01). Furthermore, a higher percentage of Blacks than Whites identified as Democrat (p < 0.001).

Predictors of Race Consciousness

The descriptive statistics above show that Black respondents are higher on race consciousness than Whites. In Table 2, we find that Blacks who identify as Democrats (p < 0.05) have higher levels of race consciousness. Additionally, we find that Black women reported slightly lower levels of race consciousness than Black men (p < 0.1). Among Whites, those with more years of education (p < 0.1) and greater support for Barack Obama (p < 0.05) are higher on race consciousness. It is notable that the significant predictors of race consciousness are different for Blacks and Whites. For Blacks, political affiliation is a key determinant, while for Whites, support for Barack Obama is the strongest predictor. These findings provide evidence suggesting that race consciousness has different meanings for Black and White respondents.

Logistic Regression Models Predicting Support for Affirmative Action

In this section, we present the results of our logistic regression models predicting support for affirmative action. First, we present the results of our analysis focusing on the sample of Black respondents. Next, we review the results of the same equations performed on the sample of White respondents. After presenting these two sets of regression tables, we summarize our results and compare significant determinants between Blacks and Whites.

Black Respondents’ Support for Affirmative Action

Table 3 presents the results of the logistic regression models we performed with our sample of Black respondents. All the models presented include the controls of sex, education, age, party identification, and support for Obama. The first model explores whether political ideology is related to respondents’ support for affirmative action. We find no significant differences in opinions toward AAPs across Black conservatives, moderates, and liberals. If fact, there are very few significant predictors of Blacks’ support for affirmative action, possibly because there was little variation in these respondents’ opinions toward AAPs, with the vast majority expressing their support.

The second model in Table 3 includes three additional focal predictors of attitudes toward AAPs: the relevance of self-interest, the relevance of group-interest, and race consciousness. The main effects of each of these variables are nonsignificant, indicating that they are unrelated to Black respondents’ opinions toward affirmative action.

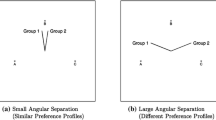

To explore whether the effects of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness differ by political ideology, we include interaction terms in the third model between these three predictors and political ideology. Focusing first on respondents’ reported feelings that AAPs affect them personally (self-interest), we find that self-interest has no effect on moderates’ opinions toward affirmative action, while being associated with support among both conservatives and liberals. These trends are illustrated in Fig. 1. Consistent with H1a, self-interest has the strongest positive effect for conservatives (β = 4.394, p < 0.05). We were surprised, however, to find that self-interest also marginally predicts support among liberals (β = 3.123, p < 0.1). Only among Black moderates was self-interest unrelated to AAP support. These findings suggest that political polarization influences whether self-interest shapes policy opinions. Respondents who identify as either conservative or liberal are more likely to have their policy positions influenced by feelings of self-interest, while moderates are unaffected by these sentiments.

The third model in Table 3 also includes an interaction term exploring whether the relationship of group-interest to AAP support is moderated by political ideology. The results reveal that group-interest has significantly different effects across political ideology (p < 0.001). Group-interest is related to AAP support among Black conservatives (β = 5.575, p < 0.01), while predicting opposition among Black moderates (β = − 6.598, p < 0.05) and liberals (β = − 7.082, p < 0.01). These trends provide support for H2a and are illustrated in Fig. 2. As we predicted, group-interest had the largest positive effect for Black conservatives. In the opposite direction, group-interest had a negative effect on Black liberals’ and moderates’ likelihood of supporting AAPs. It is possible that moderates and liberals with high levels of group-interest may oppose affirmative action on the grounds that we need a more aggressive policy to deal with racial inequality.

The last interaction term in model 3 of Table 3 examines whether the effect of race consciousness on attitudes toward affirmative action differs by political ideology for Black respondents. The results support H3a, showing that race consciousness has a significantly different effect for moderates than it does for conservatives (p < 0.01). Moderates with higher levels of race consciousness are more likely to support affirmative action (β = 9.149, p < 0.05). This relationship is illustrated in Fig. 3, where we observed the strongest positive effect of race consciousness for moderates. Race consciousness has no effect on the opinions of Black conservatives and liberals.

In short, our analysis of Black respondents highlights several key findings. First, as discovered in the descriptive statistics, a far greater proportion of Black respondents than White respondents reported that they support affirmative action. Second, we found that Black conservatives, moderates, and liberals did not differ in levels of support for affirmative action. Third, self-interest had a positive relationship with AAP support for Black conservatives, a moderately strong positive relationship for liberals, and no relationship for moderates. Fourth, we found that the effects of group-interest were in opposite directions between conservatives and those with moderate or liberal political orientations. Group-interest predicted AAP support among conservatives, while predicting opposition among moderates and conservatives. Finally, our findings revealed that race consciousness was associated with AAP support among Black moderates, while being unrelated to opinions toward AAPs among Black conservatives and liberals.

White Respondents’ Support for Affirmative Action

Next, we examine Whites’ support for affirmative action. The models presented in Table 4 use the same equations as those in Table 3, but apply them to the sample of White respondents. The first model in Table 4 examines the effect of political ideology on Whites’ support for affirmative action. Here, we find that moderates (p < 0.05) and liberals (p < 0.001) are more likely to support affirmative action than conservatives. Furthermore, liberals are significantly more likely to support affirmative action than moderates (p < 0.05). Model 1 also reveals that several control variables are significantly related to Whites’ support for affirmative action. Whites who support Obama (p < 0.01) are more likely to support affirmative action. Republicans are significantly less likely to support AAPs than those who identify as independents/other party (p < 0.05). Additionally, White women report higher support for AAPs than White men (p < 0.05). The effects of these control variables remain consistent across all subsequent models, with the exception that differences in party identification become nonsignificant in model 2 with the addition of variables measuring the relevance of self-/group-interest and race consciousness. Observed gender differences also come nonsignificant in the final model that includes interactions between political ideology and self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness.

Model 2 in Table 4 examines the main effects of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness on support for affirmative action. Only group-interest was found to have significant effects. White respondents who believe that affirmative action affects people of their race group had lower levels of support for these policies (p < 0.001). Self-interest and race consciousness were found to have nonsignificant main effects in predicting opinions toward AAPs.

The third model in Table 4 tests hypotheses H1b, H2b, and H3b regarding the moderating effects of political ideology. Hypotheses H1b and H2b are not supported. Self-interest is not a significant predictor of Whites’ support for affirmative action regardless of political ideology. Group-interest is also not moderated by political ideology, as Whites who feel affirmative action programs affect their race group are less likely to support these policies regardless of political ideology. There was, however, support for H3b. While model 2 shows that the main effect of race consciousness is not significant, model 3 reveals that race consciousness has different effects across White conservatives, moderates, and liberals. Among Whites with high levels of race consciousness, conservatives are more likely to oppose affirmative action than moderates and liberals (p < 0.05). This interaction effect is illustrated in Fig. 4.

In sum, our analysis of Whites’ support for affirmative action reveals that moderates and liberals are more likely to support affirmative action than conservatives, and that liberals are more likely to support affirmative action than moderates. Feelings of self-interest are unrelated to Whites’ attitudes toward affirmative action, while their feelings of group-interest decrease the likelihood that they will support the policy, and this effect is consistent across conservatives, moderates, and liberals. Finally, we found that the relationship of race consciousness to AAP support depends on Whites’ political ideology. High levels of race consciousness are associated with AAP opposition for conservatives, and support for moderates and liberals.

Comparing Determinants of Support Between Blacks and Whites

To compare predictors of attitudes toward affirmative action between Black and White respondents, Fig. 5 illustrates the coefficients for the effects of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness by political ideology. Coefficients were calculated from the equations reported in model 3, Table 3 (for Black respondents) and model 3, Table 4 (for White respondents). In general, a few similarities emerged. Group-interest is associated with opposition to AAPs among both Black and White moderates and liberals. Additionally, the relationship of race consciousness to attitudes toward AAPs was similarly moderated by political ideology for both Black and White respondents. Among those with high levels of race consciousness, Black and White moderates are more likely to support AAPs than conservatives.

There were also important differences to emerge in the predictors of AAP opinions. Self-interest was unrelated to policy attitudes among White respondents, but was associated with support for Black conservatives and liberals. Group-interest predicted support for AAPs among Black conservatives, while otherwise being associated with opposition for Whites. Finally, White respondents with high levels of race consciousness were more likely to support affirmative action if they were liberal than if they were conservative, while the relationship between race consciousness and AAP support was similar for Black conservatives and liberals.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study broadens our understanding of racial policy attitudes by using common measures of self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness across a sample of Black and White respondents, as well as testing for the moderating effects of political ideology. Unlike previous studies that use race group membership or economic standing as proxies for self-/group-interest, the survey items we used were high on construct validity, measuring respondents’ self-reported belief that they were personally affected by affirmative action (the relevance of self-interest) or their race group was affected (the relevance of group-interest). This new operationalization confirmed results from previous studies, while also shedding new light on the heterogeneous effects of self- and group-interest within-race groups. Confirming previous findings, we found that self-interest is not a strong predictor of policy support for Whites (Citrin et al., 1997; Sears et al., 1980; Sears & Funk, 1990) and that group-interest is negatively related to support for AAPs among Whites (Beaton & Tougas, 2001; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993; Sidanius et al., 1996). Adding new insight to our understanding of the effects of self- and group-interest, we found that the effects of these variables often differed by political ideology. Self-interest had a positive effect on support for AAPs among Black conservatives and liberals, suggesting that self-interest is particularly influential among those with more entrenched political views. When political platforms are more defined, feelings of self-interest may play a larger role in swaying Black support for AAPs. The effects of group-interest also differed among Black respondents, with group-interest predicting support for AAPs among Black conservatives and predicting opposition among Black moderates and liberals. When it comes to feelings of group-interest, Black conservatives may contradict conservative political agendas if they feel it will benefit their race group. Black moderates and liberals who are high on group-interest, on the other hand, may desire a more aggressive policy that poses a greater challenge to racial inequality.

Our study also extends research on the relationship between race consciousness and policy attitudes. Like previous research (Dawson, 2001; Schmermund et al., 2001; Simien & Clawson, 2004; Sullivan & Arbuthnot, 2009; Tate, 2010), we found that Blacks who are high on race consciousness are more likely to support racial policies like affirmative action. Yet, this effect was only significant for Black moderates. One reason for the more limited effect of race consciousness observed here is that most Black respondents already supported affirmative action in the first place, so there is little variation in the dependent variable from which to leverage. Nonetheless, the findings here do suggest that the effect of race consciousness may not be uniform across Black conservatives, moderates, and liberals. Instead, Black respondents with less polarized political agendas appear to have policy opinions that are more closely related to their perceptions of how race affects their daily life.

We also examined the effect of race consciousness on policy attitudes for Whites. While the effects of race consciousness were not as large those observed for group-interest, we nonetheless found significant differences in the effects of this variable between White conservatives, moderates, and liberals. Among Whites with high levels of race consciousness, White conservatives are more likely to oppose affirmative action than White moderates and liberals. This finding suggests that race consciousness has different meanings for conservatives, moderates, and liberals. White conservatives may feel they are treated unfairly because of their race and, therefore oppose racial policy, while White liberals and moderates may be more cognizant of their racial privilege and support racial policy as a result. While both groups share an awareness that their race affects their day-to-day life, they may differ in how they understand its fundamental role.

While our study sheds new light on the predictors of attitudes toward affirmative action, it also has limitations that should be noted. First, respondents in this study come from a random sample of Chicago residents. The diverse and politically vibrant atmosphere of Chicago, where issues like affirmative action are regularly featured in public debate, make it an advantageous location for the study of racial policy. Yet, readers should take caution when extending the findings presented here to other contexts. Second, while our sample size is larger than many studies examining policy attitudes, it remains relatively small. Given this limitation, our findings are likely conservative estimates of the moderating influence of political ideology and self-interest, group-interest, and race consciousness.

In sum, our examination of individuals’ support for affirmative action provides four contributions to our understanding of racial policy attitudes. First, while self-interest is not a strong predictor of attitudes toward affirmative action among Whites, it remains an influential factor for Black conservatives and liberals. Second, group-interest has a large influence on policy attitudes that differ between Blacks and Whites and between conservatives and those with moderate or liberal political ideologies. Third, race consciousness affects both Black and White policy attitudes, but this effect differs for conservatives, moderates, and liberals. Fourth, our study provides strong evidence for the moderating effects of political ideology on policy preferences, suggesting that conservatives, moderates, and liberals process similar motives in different ways to reach divergent policy positions.

Notes

While this dichotomous variable does not allow us to measure varying levels of support or opposition, it requires less cognitive effort on behalf of respondents, thus reducing satisficing (Krosnick, 1991; Krosnick & Presser, 2010). This is particularly important in the case of the survey used here, where respondents were asked their opinion on a variety of political issues.

Results are confirmed when using the more detailed 5-item measure of political ideology. We chose to use a trichotomous measure because the 5-item measure had small cell counts (less than 20) in some categories.

Internal reliability for this index was similar for both Black (Cronbach’s alpha = .83) and White (Cronbach’s alpha = .80) respondents.

We include party identification as a control variable, even though it is correlated with political ideology, because respondents of different political ideologies are found across all political parties. Nonetheless, results remain consistent when party identification is not included as a control variable.

References

Allison, R. (2011). Race, gender, and attitudes toward war in Chicago: An intersectional analysis. Sociological Forum,26(3), 668–691.

Beaton, A., & Tougas, F. (2001). Reactions to affirmative action: group membership and social justice. Social Justice Research,14, 61–78.

Bobo, L. (1998). Race, interests, and beliefs about affirmative action: Unanswered questions and new directions. American Behavior Scientist,41, 985–1003.

Bobo, L., & Kluegel, J. (1993). Opposition to race-targeting: Self-interest, stratification ideology, or racial attitudes? American Sociological Review,58, 443–464.

Boninger, D., Krosnick, J., & Berent, M. K. (1995). Origins of attitude importance: Self-interest, social identification, and value relevance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,68, 61–80.

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Schiffhauer, K. (2007). Racial attitudes in response to thoughts of white privilege. European Journal of Social Psychology,37, 203–215.

Bryant, B. E. (1975). Respondent selection in a time of changing household composition. Journal of Marketing Research,12(2), 129–135.

Citrin, J., Green, D., Muste, C., & Wong, C. (1997). Public opinion toward immigration reform: The role of economic motivations. The Journal of Politics,59(3), 858–881.

Crosby, F. J., Iyer, A., Clayton, S., & Downing, R. A. (2003). Affirmative action: Psychological data and the policy debates. American Psychologist, 58(2), 93–115.

Crosby, F. J., Iyer, A., & Sincharoen, S. (2006). Understanding affirmative action. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 585–611.

Dawson, M. (2001). Black visions: The roots of contemporary African–American political ideologies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Feldman, S., & Huddy, P. (2005). Racial resentment and white opposition to race-conscious programs: Principles or prejudice? American Journal of Political Science,49(1), 168–183.

Goren, M. J., & Plaut, V. C. (2012). Identity form matters: White racial identity and attitudes toward diversity. Self and Identity,11, 237–254.

Holbrook, A. L., Sterrett, D., Johnson, T. P., & Krysan, M. (2016). Racial disparities in political participation across issues: The role of issue-specific motivators. Political Behavior,38, 1–32.

Iyer, A., Leach, C. W., & Crosby, F. J. (2003). White guilt and racial compensation: The benefits and limits of self-focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,29, 117–129.

Jardina, A. (2014). Demise of dominance: Group threat and the new relevance of white identity for American politics. PhD Dissertation, Department of Political Science, University of Michigan.

Jardina, A. (2019). White identity politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D., & Sears, D. (1981). Prejudice and politics: Symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,40, 414–431.

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M., & Unzueta, M. M. (2014). Deny, distance, or dismantle? How White Americans manage a privileged identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science,9(6), 594–609.

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., & Shaumberg, R. (2010). Racial prejudice predicts opposition to Obama and his health care reform. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,46, 420–423.

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Shulman, E. P., & Schaumberg, R. L. (2013). Race, ideology, and the tea party: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE,8(6), 1–11.

Knowles, E. D., & Peng, K. (2005). White selves: Conceptualizing and measuring a dominant-group identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,89(2), 223–241.

Kravitz, D., & Platania, J. (1993). Attitudes and beliefs about affirmative action: Effects of target and of respondent sex and ethnicity. Journal of Applied Psychology,78(6), 928–938.

Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitudes measures in surveys. Applied Cognitive Psychology,5, 213–236.

Krosnick, J. A., & Presser, S. (2010). Question and questionnaire design. In P. V. Marsden & J. D. Wright (Eds.), Handbook of survey research (2nd ed., pp. 263–314). West Yorkshire: Emerald Group.

Kuklinski, J., Sniderman, P., Knight, K., Piazza, T., Tetlock, P., Lawrence, G., et al. (1997). Racial prejudice and attitudes toward affirmative action. American Journal of Political Science,41(2), 402–419.

Lavrakas, P.J., Benson, G., Blumberg, S., Buskirk, T., Cervantes, I.F., Christian, L., Dutwin, D., Fahimi, M. Feinberg, H., Guterbock, T., Keeter, S., Kelly, J., Kennedy, C., Peytchev, A., Piekarski, L, & Shuttles, C. (2017). Report from the AAPOR task force on the future of U.S. general population telephone survey research. American Association for Public Opinion Research. (https://www.aapor.org/getattachment/Education-Resources/Reports/Future-of-Telephone-Survey-Research-Report.pdf.aspx). Accessed August 12, 2018.

Lowery, B., Unzueta, M. M., Knowles, E. D., & Goff, P. A. (2006). Concern for the in-group and opposition to affirmative action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,90(6), 961–974.

Malka, A., & Lelkes, Y. (2010). More than ideology: Conservative-liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Social Justice Research,23, 156–188.

Piston, S. (2010). How explicitly racial prejudice Hurt Obama I the 2008 election. Political Behavior,32, 341–451.

Powell, A. A., Branscombe, N. R., & Schmitt, M. T. (2005). Inequality as ingroup privilege or outgroup disadvantage: The impact of group focus on collective guilt and interracial attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,31(4), 508–521.

Rabinowitz, J., Sears, D., Sidanius, J., & Krosnick, J. (2009). Why do White Americans oppose race-targeted policies? Clarifying the impact of symbolic racism. Political Psychology,30(5), 805–828.

Rudolph, T., & Evans, J. (2005). Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending. American Journal of Political Science,49(3), 660–671.

Schmermund, A., Sellers, R., Mueller, B., & Crosby, F. (2001). Attitudes toward affirmative action as a function of racial identity among African American college students. Political Psychology,22(4), 759–774.

Sears, D., & Funk, C. (1990). Self-interest in Americans’ political opinions. In J. J. Mansbridge (Ed.), Beyond self-interest (pp. 147–170). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sears, D., Lau, R. R., Tyler, T., & Allen, H., Jr. (1980). Self-interest vs. symbolic politics in policy attitudes and presidential voting. The American Political Science Review,74(3), 670–684.

Sears, D., Van Laar, C., Carrillo, M., & Kosterman, R. (1997). Is it really racism? The origins of White Americans’ opposition to race-targeted policies. The Public Opinion Quarterly,61(1), 16–53.

Sellers, R. M., Rowley, S., Chavous, T., Shelton, N., & Smith, M. (1997). Multidimensional inventory of black identity: Preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,73, 805–815.

Shteynberg, G., Leslie, M., Knight, A., & Mayer, D. (2011). But affirmative action hurts us! Race-related beliefs shape perceptions of White disadvantage and policy unfairness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,115, 1–12.

Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., & Bobo, L. (1996). Racism, conservatism, affirmative action, and intellectual sophistication: A matter of principled conservatism or group dominance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,70(3), 476–490.

Simien, E., & Clawson, R. (2004). The intersection of race and gender: An examination of Black Feminist consciousness, race consciousness, and policy attitudes. Social Science Quarterly,85(3), 793–810.

Sniderman, P., & Carmines, E. (1997). Reaching beyond race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sniderman, P., Crosby, G. C., & Howell, W. G. (2000). The politics of race. In D. Sears, J. Sidanius, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Racialized politics (pp. 236–279). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Son Hing, L. S., Bobocel, D. R., & Zanna, M. (2002). Meritocracy and opposition to affirmative action: Making concessions in the face of discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,83(3), 493–509.

Steeh, C., & Krysan, M. (1996). The polls-trends: Affirmative action and the public, 1970–1995. Public Opinions Quarterly,60(1), 128–158.

Sullivan, J., & Arbuthnot, K. (2009). The effects of Black identity on candidate evaluations: An exploratory study. Journal of Black Studies,40(2), 215–237.

Tate, K. (2010). What’s going on? Political incorporation and the transformation of Black public opinion. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Tuch, S., & Hughes, M. (2011). Whites’ racial policy attitudes in the twenty-first century: The continuing significant of racial resentment. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,63, 134–152.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Maria Krysan for her feedback on previous versions of this paper.

Funding

Collection of data used in this study was funded by the Chicago Area Study Initiative at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Great Cities Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent procedures for this study were approved by the authors’ institutional review board and carried through in the course of data collection.

Additional information

This paper used data from the 2008 Chicago Area Study (CAS) at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and is dedicated in memory of Ingrid Graf, the 2008 CAS Project Coordinator.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scarborough, W.J., Holbrook, A.L. The Complexity of Policy Preferences: Examining Self-interest, Group-Interest, and Race Consciousness Across Race and Political Ideology. Soc Just Res 33, 110–135 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-019-00345-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-019-00345-5