Abstract

This article aspires to foster the debate around the methods for measuring time and income poverty. In the last fifteen years a few studies (Dorn et al. in RIW, 2023; Harvey and Mukhopadhyay in SIR 82, 57–77, 2007; Bardasi and Wodon in FE 16, 45–78, 2010; Zacharias in LEIBCWP. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383, 2011; Merz and Rathjen in RIW 60, 450–479, 2014) attempted to measure multidimensional deprivation including time poverty in the definition. Some of them (Bardasi & Wodon in FE 16, 45–78, 2010; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay in SIR 82, 57–77, 2007; Zacharias in LEIBCWP. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383, 2011) put unpaid work–and, therefore, gender inequalities in the division of work–at the center. Despite the fact that the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty (LIMTIP) was first presented more than a decade ago (Zacharias in LEIBCWP. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383, 2011), the measure was always employed in reports and never empirically discussed in an academic article. Here I want to fill this gap in the debate by comparing the LIMTIP to the other measures and by applying it to a new case–Italy–furthering the exploration around the linkages between gendered time allocation, employment patterns and household wellbeing in a country characterized by an extraordinary low women’s participation in the labor market and an equally extraordinary wide gender gap in unpaid care and domestic work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Attempts to measure time and income poverty simultaneously at the individual level are scarce (Bardasi & Wodon, 2010; Dorn et al., 2023; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Merz & Rathjen, 2014; Zacharias, 2011). The goal of this article is to open a debate with other scholars engaged in the measurement of time and income poverty about how to improve past attempts and develop new strategies. In particular, this paper will focus on the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty-LIMTIP, that in this study is applied to Italy. Despite the fact that the LIMTIP was first presented more than a decade ago (Zacharias, 2011), the measure was always employed in reports (with the exception of a book chapter by Antonopoulos et al. (2017)) and never discussed in an academic article.

Poverty has a multidimensional nature (Atkinson, 2003). Just to mention a few dimensions, poverty could be measured in terms of income, assets ownership, access to services, participation, and capabilities. Therefore, the first step in measuring poverty is represented by the choice of the indicator(s) to be employed in the assessment. How poverty is measured matters in terms of the policies adopted for tackling it (Alkire & Foster, 2011), and of the people addressed by such policies–in respect of their gender, age, class, ethnicity, working status, etc.

In her classic book, Woman’s Role in Economic Development, Ester Boserup pointed out that “the subsistence activities usually omitted in the statistics of production and income are largely women’s work” (Boserup, 1970, p. 163). Domestic production and related activities are excluded, rather than underestimated, in statistics, because such activities have been perceived as simply falling outside the conventional definition of work (Beneria, 1999), and, therefore, of productive activities. In particular since the late 1970s, feminists and women’s advocacy organizations have criticized the underreporting and undervaluation of women’s contributions to national output and labor force statistics (Beneria et al., 2016).

Unpaid work performed within the household, whether it is domestic work or care work, is fundamental for the wellbeing of individuals and of societies, and care responsibilities have a wide impact on how we experience life. They can impact the personal ability to enjoy free time, or even compromise the capability to undertake paid employment. This might happen because care responsibilities are not equally shared within the household between partners, nor within society. Societies can be more or less familistic depending on the degree to which they depend on households for responding to the care needs of their citizens (Razavi, 2007).

Time is one of the basic inputs not only in the production of marketable goods but also in the production of self-consumed goods and services.Footnote 1 In the life of every human being time is a limited resource. Simultaneously, time is a necessary input into anything that one cares to do or to become. As Goodin, et al. (2008) pointed out: time is an egalitarian, scarce, and necessary input.

According to Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007) there are four main time categories: contracted time, committed time, necessary time and free time. Contracted time is time reserved for undertaking paid work or education. Once one is involved in employment or education one is obliged to allocate a certain amount of time to these activities. Committed time is the necessary time for taking care of the maintenance of one’s home and family. Necessary time is the time one needs for personal maintenance (eating, sleeping, personal hygiene). Free time consists of the residual time.Footnote 2 Both contracted and committed activities represent productive work. The first, excluding education, takes the form of paid work; the second takes the form of unpaid work. As a consequence, deprivation could arise not only from the lack of income but also from the time deficit of many working people. A time poverty measure helps to identify and investigate those who remain at risk of poverty even though their incomes are above the poverty threshold, or to capture in the short run benefits to time allocation from an intervention or technological change that may have long run benefits in other domains (Willis et al. 2016). The concept of time poverty—and its connection with monetary poverty—was developed around 40 years ago by Claire Vickery (1977). She assumed that in order to attain the poverty threshold the household requires a minimal input of time regardless of the amount of money available, and that “these minimal levels of time and money are not sufficient input by themselves to provide a non-poverty standard of living” (Vickery, 1977, p. 29). Therefore, the well-being of the household must be assessed on the basis of its income and of its structure–that is directly connected with its time requirements.

The advantage offered by poverty measures that combine the income and time dimensions is represented mainly by their ability of including–and valuing–work in both its forms of paid and unpaid activities. Besides this shared feature, time and income poverty measures are very different. When comparing different attempts of measuring time and income poverty, one is confronted by the fact that, on one hand, all of the studies agree on the fact that time–similarly to income–is strictly connected with other fundamental dimensions such as health, education, care, attainment and consumption of goods. On the other hand, that time poverty measurement is “currently immature and full of arbitrary assumption” (Williams et al. 2016, p. 279).

As it will be presented in the second section of this article, there is no agreement among the analyzed studies on whether the focus of time poverty should be on the access to leisure time (Dorn et al., 2023; Merz & Rathjen, 2014) or on necessary household production (Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Zacharias, 2011); or whether the analysis should focus exclusively on time deficits (Bardasi & Wodon, 2010; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Zacharias, 2011) or include time surpluses too (Dorn et al., 2023; Merz & Rathjen, 2014). Studies even differ on the goal of the measurement of time poverty. Some emphasize the substitution between income and leisure time (Bardasi & Wodon, 2010; Dorn et al., 2023; Merz & Rathjen, 2014). Others stress the importance of household production to the wellbeing of the household and the impact of time poverty on monetary poverty (Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Zacharias, 2011).

Against this heterogenous context, the most valuable feature of the LIMTIP is its focus on unpaid work time in the form of household production, which highlights gender inequalities in the division of work and how this affects poverty. This is the main reason that led the author of this article to choose this measure for analyzing Italy–as presented in Sect. 3. Italy is a country of sharp gender differences in time use. When we look at the LIMTIP, the value added of combining both time and income poverty in a single measure is that it sheds light onto the contribution of unpaid work to household wellbeing, and, therefore, onto a relevant part of women’s contribution to household wellbeing. The juxtaposition of the two dimensions can highlights the inability of some households to overcome poverty because of the lack of time. Moreover, in comparison to the other attempts to measure time and income poverty that are cited in this article, the unique contribution of the LIMTIP to the understanding of time and income poverty stands in its capacity of reflecting the differential ability of households to remedy time poverty by purchasing market substitutes. Whereas other scholars focus on the notion of time poverty as the capacity of households to choose their hours of employment. This difference has relevant policy implications. In fact, in a capitalist market, workers typically have more freedom to spend their money however they see fit rather than to pick the amount of work hours they like.

This study employs the LIMTIP methodology with two new features with respect to previous studies. First, previous LIMTIP studies focused on developing countries (Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Turkey, Korea, Ghana and Tanzania), but the LIMTIP uses a distinctive methodology for poverty analysis that can and should be applied to the developed context, too. In particular, applying the LIMTIP to developed countries can provide new insights on the impact of the gender division of work.Footnote 3 Second, this paper includes two time reference points for the same country–a first in a LIMTIP study–that can be used for analyzing poverty trends.

The paper is structured as follows. In the second section, the LIMTIP methodology is presented comparing it to other attempts of measuring time and income poverty at an individual level. In the third section, the gendered division of work in Italy is presented using time use data. In the fourth section, the application of the LIMTIP methodology to Italian data is described and the results are presented with a focus on women and labor market participation. In the last section, the conclusions are discussed.

2 The Measurement of Time and Income Poverty

2.1 A Comparison Among Different Time and Income Measures

In their review of time poverty studies, Williams, Masuda and Tallis (2016) focus their attention on the categories employed for analyzing time poverty and on the difference between relative and absolute poverty thresholds. Here, following their example, five attempts to measure time and income poverty–including the LIMTIP, and the most recent measure developed by Dorn et al. (2023)–will be compared based upon a set of criteria (see Box 1).

All of the analyzed studies on time and income poverty (Bardasi & Wodon, 2010; Dorn et al., 2023; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Merz & Rathjen, 2014; Zacharias, 2011) share the motivation to incorporate measures of time-use into gender-sensitive poverty assessment. Including the time variable, scholars recognize the relevance of unpaid care and domestic work for household wellbeing, and, given the unequal division of work, an important part of women’s contribution to it.

Time and income poverty measures generally take as a starting point a measure of monetary poverty–absolute or relative–that is then integrated with a measure of time poverty. In doing so, several different approaches can be adopted. Starting from the measure of monetary poverty, income (or consumption) can be measured at individual or household level. For Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007) an individual is counted as poor if the household income falls below the poverty threshold. Bardasi and Wodon (2010) employ consumption or income poverty at household level. While, Merz and Rathjen (2014) use net equivalent household income. Only Dorn et al. (2023) attempt to estimate intrahousehold income sharing and, therefore, individual monetary poverty. First, they pool household income and then they use information on household specific expenditure shares for male and female household members as an approximation for intra-household income sharing. They use an approximation because the database employed for the specific study allows us only to know whether an expenditure in personal goods was made for a male or a female but does not give information about the actual recipient of the good who may be any member (child or adult) of the household. The inability to categorically define the share of household income available to each person in the household leads the LIMTIP to assume the option of complete pooling (Zacharias, 2011).

With regard to time poverty, the approaches are diverse, too. Merz and Rathjen (2014) and Dorn et al. (2023) focus on leisure time, and, like monetary poverty, they determine a leisure time threshold. As the focus on leisure time may seem appropriate in the study of time poverty proper, it becomes problematic when it comes to the measurement of time and income poverty. The inclusion of time surpluses in the analysis may even lead to ambiguous conclusions. In fact, in contrast to an abundance of income, excessive amounts of free time, such as those brought on by disability or unemployment, may not be useful for creating wellbeing (Williams, Masuda and Tallis, 2016). Time surpluses are by definition unable to grasp the depth of the time deprivation, which is associated with a deficit. Moreover, in the case of Dorn et al. (2023) the threshold for time poverty is derived by aligning it with the income poverty threshold (in the specific case study of Mexico, the 15% quantile of the income distribution in the population) without any link to time specific issues. Finally, both Merz and Rathjen (2014) and Dorn et al. (2023) attempt to measure the degree of substitution between leisure and income. But, as highlighted by others (Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Zacharias, 2011), free time cannot be converted into money, as it is impossible to know whether or not the individual had the option of working longer or shorter hours.

Bardasi and Wodon (2010) focus on working hours. They estimate two thresholds for the weekly maximum total (paid and unpaid) working hours, a lower threshold equal to 50 h per week, and an alternative threshold equal to 1.5 times the median of the total individual working hours distribution. Persons above the threshold are considered time poor only if they work long hours and they are income poor, or if they would become income poor if they were to reduce their working hours up to the consumption poverty line. Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007) are concerned about total working hours, too, but their approach starts from the estimate of a required household work minimum. Then, they compare the available time–that is the time left over and above what is required for personal maintenance and the required household work minimum–with the time that can unequivocally be allocated to work and leisure activities in order to establish if a household is time poor. This definition of time poverty puts unpaid work at the center of the analysis. Daily reproduction of household members requires that some amount of time must be dedicated to necessary household production activities. If non-constrained time is insufficient the individual–and, therefore, the household–encounters a time deficit. Households with time deficits will have to purchase market substitutes to fill the gap in household production. The LIMTIP follows this example, with the significant exception that, where Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007) equally share the minimum required time for household production between the partners, Zacharias (2011) takes into consideration intrahousehold disparities and employs the actual shares of unpaid work of each partner for dividing the minimum required time for household production.

Finally, both Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007) and Zacharias (2011) calculate the money value of the time deficit by imputing a monetary equivalent of the time deficit amount and adjusting the poverty threshold by the amount obtained, implementing a replacement cost set at the minimum wage rate in the market. They assume that paid work time cannot be changed or substituted by unpaid work time due to the contracted nature of paid work time. However, unpaid work time, except for the minimum non-substitutable amount, is perfectly substitutable with paid work time/money income.

Past case studies consider both developed and developing countries. In particular, Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007), who employ a methodology that shares several features with the LIMTIP, analyze Canada. This highlights how household production is essential, not only in developing contexts, but also in developed countries.

One last criterion of comparison is represented by the data sources used in these studies. Unfortunately, time use data are scarce and sometimes miss valuable information in terms of household income and/or consumption. Some studies are based on questionnaires (Bardasi & Wodon, 2010; Dorn et al., 2023; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007). These studies have the advantage of including information both on resources and time use but have the limit of providing data on time use from less accurate self-reported activity lists. Merz and Rathjen (2014) employ two separate datasets, one for income and living standard related information and one for time use information. The advantage of this approach is that time use data is derived from actual time use surveys that employ more reliable time use diaries. The limit is that the study assumes that families with similar characteristics share similar time use habits. The LIMTIP adopts this last approach.

In conclusion, studies that focus on leisure (Dorn et al., 2023; Merz & Rathjen, 2014) present the advantage of including both time deficit and surpluses, but their results might be misleading because, first, excessive amounts of free time, as due to disability or unemployment, may not be useful for creating wellbeing; second, paid work time is not interchangeable with unpaid work time due to the contracted nature of paid work time. Studies that focus on unpaid work time (Bardasi & Wodon, 2010; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay, 2007; Zacharias, 2011) are best suited for analyzing material deprivation. The limit of Bardasi and Wodon’s (2010) study is represented by the fact that time poverty is not translated into monetary poverty. Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007) overcome this obstacle by monetizing time deficits and adjusting monetary poverty thresholds, but they fail in giving attention to important intrahousehold disparities in terms of unpaid work. The LIMTIP is able to identify individual time deficits, therefore putting the accent on gender inequalities in the division of work, and how these affect household wellbeing. This represents one of the main contributions of the LIMTIP to the development of time and income poverty measures, together with its focus on minimum required household production–that highlights the importance of the daily reproduction of household members, and, therefore, of unpaid care and domestic work.

2.2 The LIMTIP

The LIMTIP assumes that similar to a minimum amount of income that secures access to a basic “basket” of goods and services available in markets, a minimum amount of unpaid care and domestic work time is equally necessaryFootnote 4 and must also be specified (Antonopoulos et al., 2017). The minimum amount of unpaid care and domestic work time is the time used for generating the minimum required household production for subsisting at the poverty level of income, and it is represented by those indispensable activities that generate goods and services for household members–such as providing cooked meals, feed babies, or take children to school.

The LIMTIP adopts two different approaches for income and time with regard to intra-household disparities. Income poverty is measured at the household level, while time poverty is measured at the individual level. The advantage of employing time use data is represented by the fact that they give detailed information on the amount of time that each person in the household devotes to different kinds of activities. Intra-household disparities in the division of unpaid work and paid work are, therefore, visible and assessable. An analysis that does not take these elements of disparity into account can be fundamentally inequitable towards the individuals in the households.

In practice, in order to assess time poverty, the LIMTIP builds a poverty threshold for the minimum necessary time required for household production and then uses it for the assessment of time deficits. The poverty threshold for the minimum necessary time required for household production varies in relation to household size and composition (number of adults and number of children). The construction of these thresholds is explained below step by step.

Time is classified into four categories:

-

1.

time for paid work, which includes the time spent in employment plus the time for commuting;

-

2.

time for personal care and leisure, which includes time spent sleeping, eating and on personal hygiene, plus leisure time;

-

3.

time for substitutable household production, which includes the time spent in unpaid care and domestic work, but only with regard to activities that one could pay a third person to provide;

-

4.

Time for non-substitutable household production, which includes the time spent in unpaid care and domestic work, but only with regard to the share of unpaid care and domestic activities that one does exclusively oneself.Footnote 5

The LIMTIP uses these four time categories for estimating time poverty and it builds thresholds for each of them–with the exclusion of paid work, for which we assume that individuals do not have the freedom to decide how many hours to work, but they have to respect a contract. Employing a threshold is important for avoiding overestimation of time poverty. Therefore, instead of estimating individual time poverty employing the actual hours spent in different activities, we employ thresholds that are set at the minimum necessary.Footnote 6 For example, without a threshold for personal care, which includes hours of sleep, the LIMTIP could count as time poor someone that sleeps more than the average.

The definition of time poverty can be represented in three equations (Zacharias, 2011):

Equation (1) represents the time available (A) to individual i, where 168 are the hours of the week, C is the minimum required amount of time for personal care, D is the minimum required amount of non-substitutable time for household production, and R is the amount of minimum required substitutable household production time essential to subsist at the poverty level of income. αFootnote 7 and γ are respectively individual shares within household’s members in D and R.

A dash (-) is added to the symbols on the right side of the equation because they represent, as it was mentioned above, the minimum necessary timeFootnote 8 for the group that the household belongs to (in terms of number of adults and number of children present in the household) rather than the actual observed values for the household. They are the time allocation parameters for the household which, in principle, are similar to the parameters (such as minimum expenditure on food and nonfood items) used in the construction of absolute income/consumption poverty measures (Zacharias, 2011).Footnote 9

Equation (2) is the individual time deficit (\({\mathrm{X}}_{\mathrm{i}}\)), with L representing the weekly hours of employment of individual i. This step allows us to identify the time poor persons. From a gender perspective being able to estimate time poverty from an individual point of view is fundamental because it enables us to study the characteristics of who suffers from a time deficit. The other members of the household would suffer from this time deficit indirectly in terms of a deficiency in household production.

Finally, Eq. (3) represents the household time deficit (X’), that is the sum of the \({\mathrm{X}}_{\mathrm{i}}s\) of the household’s members. For the household’s members without a time deficit, \({\mathrm{X}}_{\mathrm{i}}\) is equal to 0.Footnote 10 The household is defined as time-poor if the hours of employment exceed the available time for at least one of the adult members of the household. This is based on the idea that an individual time deficit has an impact on the whole household because of the deficiency in household production that derives from the time deficit.

The LIMTIP divides the time for minimum required household production between the adult members of the household based on their actual shares of such activities (Eq. 1). This procedure highlights that household responsibilities in terms of unpaid work are not equally shared between partners, and therefore not all household members are equally time poor–or non-time poor (Eq. 2). On the other hand, the LIMTIP recognizes that the time deficit of a member of the household affects the whole household (Eq. 3). In fact, if a household’s member has a time deficit, that time deficit translates into forgone household production that has an impact on the whole household, meaning that without the necessary time for household production the household will have to replace unpaid work time by goods or services purchased from the market (as prepared meals or babysitting). This decreases household disposable income.

Therefore, the threshold of income poverty needs to be modified to take into account that where a time deficit exists, that time deficit needs to be compensated by the additional income necessary to pay for the unmet part of substitutable household production. Therefore, the income poverty threshold will look as follows (Zacharias, 2011):

In Eq. (4), \(y^{\prime}\) is the poverty threshold adjusted to account for time poverty, \(\overline{y }\) is the unadjusted income poverty threshold, and p is the unit replacement cost of household production. The adjusted poverty threshold, \(y^{\prime}\), is specific for each time-poor household because it reflects time deficits.

Section 4 will describe how the LIMTIP is empirically applied to the case study of Italy. The next section is devoted to presenting the Italian context.

3 The Gendered Division of Work in Italy

The focus of the LIMTIP is on the contribution of household production to the material wellbeing of its members. Household production, in the form of goods (i.e. cooked meals, homemade produce, etc.) and services (i.e. childcare, laundering, cleaning, etc.), is achieved through the time devoted by household members to unpaid care and domestic work. However, the division of unpaid care and domestic work among household members and, particularly, between partners, is usually unequal–with women bearing most of the burden of domestic and care responsibilities. From the LIMTIP perspective, this generates unequal time deficits.

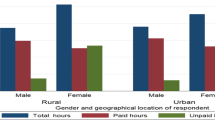

In the EU, Italy has the second lowest women’s employment rate.Footnote 11 This is reflected in time-use data. The last available time-use data for ItalyFootnote 12 highlights that working age women (18–64 years old) perform on average around 14 weekly hours of paid work, versus 25 for men (Table 1). On the other side, women spend an average of 32.4 h per week in unpaidFootnote 13 care and domestic work (the average for employed women is slightly lower at 28.8 h), while men only spend around 12 h per week on average in unpaid care and domestic work (the average is similar for employed men). On average unpaid care and domestic work hoursFootnote 14 represent almost 70 percent of working time for women, and only 32.6 percent for men.

As a result, women on average work almost 10 h per week more than men. In fact, although women devote a fewer hours to paid work on average, their total working time is higher than men’s when unpaid care and domestic work is added to the sum (on average women work 46.5 h per week, while men 37.1). The difference persists even when the analysis is confined to employed people: employed women work on average almost 58 h per week (paid plus unpaid work), while employed men work less than 50 h per week.

A distinction among different types of households by employment status of the person of reference and the partner, if present, and by presence of children (Table 2) allows us to see that in general women work more hours than men (with an exception only for male-earner households without children). Four types of households are identified: non-earners, male-earners, female-earners, double-earners. The distinction is based on the number of hours of paid work. If no adult member of the household reports paid work hours, the household is recorded as non-earner. A double-earner household is a household where both partners record paid work hours. A male/female-earner household is a household where only a male/female adult records paid work hours. The most relevant part of unpaid work consists of domestic work that is also the category of unpaid work where the largest difference between women and men is found. Moreover, the presence of children in the household increases the total number of working hours (because of an increased number of hours devoted to care work), and it has a stronger impact on women’s time-use. In fact, women’s total working time in the presence of children increases by an average of 10 h (10.5 h in male-earner households, 10 h in female-earner households, and more than 7 h in double-earner households). On the other hand, in double-earner households with children, men tend to work more hours than women in paid work. Nonetheless, as underlined above, women still work more hours than men in total, due to women’s higher number of unpaid working hours. In double-earner households in particular, women’s average number of weekly hours of domestic work is almost three times that of men.

Another relevant finding is that in Italy women living as a couple in households without children perform on average 16.4 h of unpaid work more than single women living alone in households without children. On the other hand, even if there is almost no difference in the average number of weekly hours of paid work between women and men for single persons living alone, the average number of weekly hours of paid work of women living as a couple drops to almost half of the number of hours of paid work performed by men. Nonetheless, on average the total number of weekly hours of work (paid and unpaid) performed by women living as a couple is higher than that of men.

4 LIMTIP Estimates for Italy

As described in Sect. 2.2, the first step for calculating the LIMTIP is represented by the construction of time thresholds for different activities, in order to estimate time poverty. First, we build a threshold for minimum necessary household production.

The hours of required household production for each adult person in the household depend on the household-level threshold of household production and the individual’s share in the household-level threshold. The thresholds for household production hours are set at the household level; that is, they refer to the total weekly hours of household production to be performed by the members of the household, taken together. In principle, they represent the average amount of minimum required household production.

In order to identify the minimum required amount of household production, the LIMTIP takes as a standard the average time spent in household production of those households that have an income around the poverty line (income ± 25 percent of the poverty line). Therefore, the minimum required household production is the household production that is required to subsist at the poverty level of income. Moreover, the reference group used in constructing the thresholds consists of households with at least one non-employed adult. This was done because, in general, income poverty thresholds used in poverty assessments rest on the implicit assumption that households around the poverty line possess the required number of hours to spend on household production (Zacharias, Antonopoulos and Masterson, 2012).

Even if TUSs provide a rich amount of information on time use and on individual and household demographic characteristics, the data on income is, generally, not sufficient to develop a LIMTIP study. In the case of Italy, the single information on income included in the TUS is the individual main source of income (whether it is from work, retirement, etc.), but in order to estimate the LIMTIP we need to know the total household disposable income. Information on total household disposable income–together with ample data on income, housing, social exclusion, labor, education, and health–can be found in EU-SILC.Footnote 15 Merging TUS and SILC data in a single ad hoc dataset allows us to access complete information on time use of the population and on its income and living standards. That is useful for developing an in depth analysis on the characteristics of households that fall below the poverty line, which is the objective of LIMTIP studies.

For this analysis on Italy, the EU-SILC data on Italy has been matched with the IT-TUS. The imputation for time use is conducted using propensity score statistical matching (PSSM). PSSM is used in observational studies to generate suitable control groups that are similar to the treatment groups when a randomized experiment is not available (Rubin & Thomas, 1996). In the imputation context, the propensity score estimates the “likelihood/probability” of “having the outcome observed” for any subject with a similar background measured by the independent variables. The target variable is regressed on common variables in both files and the predicted value is used to rank the records in each file (Kum & Masterson, 2010). Subjects with close propensity scores are considered similar and are matched together. The matching procedure is presented in detail in Appendix 1.

The study uses two waves for both data sources (IT-TUS 2008–2009 and 2013–2014 and the Italian data of EU-SILC 2009 and 2015Footnote 16 -IT-SILC from now on).

The estimate of necessary household production is based on the sum of the average time devoted to three forms of unpaid care and domestic work.Footnote 17 On the basis of household composition (number of adult members and number of children), the minimum necessary household production to subsist with an income around the poverty line is calculated. The results are presented in Table 3.

With the information derived as described above, the time available at an individual level has been estimated by subtracting from the total number of hours in a week (168 h) the weekly hours of required personal maintenance,Footnote 18 the individual non-substitutable household production,Footnote 19 the personal share of weekly hours of required substitutable household productionFootnote 20 and for employed persons the weekly hours of paid work and the required weekly hours of commuting.Footnote 21 As a result, individual time deficits for adults (18 years old and up) are obtained. If the sum of paid and unpaid work is higher than the time available (the time left after personal maintenance and non-substitutable household production are fulfilled), the person suffers from time poverty.

The household-level value of time deficits can, then, be obtained in a straightforward manner by summing the time deficits of individuals in the household. First, the household is designated as time poor if at least one of its members is time poor. Then, for each household a new poverty threshold that considers time deficits is calculated. Accounting for time deficits requires the modification of the official poverty thresholdFootnote 22 (Eq. (4) in Sect. 2.2). The modification consists in adding the monetized value of household time deficit to the threshold. As a replacement cost of the forgone household production that accompanies the time deficits, the hourly minimum salary for domestic workers in Italy, which was equal to 6 euros (including taxation),Footnote 23 is employed. The monetized value of time deficits can raise the poverty line to an extent that some of those who are above the official poverty threshold can now be seen to be poor. For those that are already below the official poverty line, time deficits can make their income deficit (i.e., the difference between poverty line and income) larger.

The first relevant result of this analysis is that in Italy women on average suffer from time poverty more than men. As shown in Table 4, in 2008 21.2 percent of women were time-poor versus 12 percent of men. In 2014 the percentage of time-poor women reported a slight decrease (19.9), but the percentage of time-poor men increased to 13.3.Footnote 24 Therefore, a considerable shrinking (almost two and a half percentage points) of the gap in time poverty between women and men was registered.

Considering only employed adults, the analysis highlights that the majority of employed women are time poor (56 percent in 2008 and 53 percent in 2014)–that is around double the time poverty rate registered for employed men (21 percent in 2008 and 24 percent in 2014). Data shows that for employed women time poverty slightly decreased over the period under analysis, while for employed men the data registered an increase in the incidence of time poverty. Focusing on non-employed persons, the data highlights, that even if the percentage of time poor persons in this group are smaller, the results for women and men follow the same trends as for employed people.

The results on time poverty in Italy are in line with the findings registered for previous LIMTIP studies, indicating that time poverty affects more women than men and more employed than non-employed persons. In Korea (Zacharias, Masterson and Kim, 2014) 55 percent of the time poor persons are women. In Italy women represent over 60 percent of the time poor persons (65 percent in 2008 and 61 percent in 2014). Both in Italy and Korea the percentage of time poor persons among non-employed people is very low. In the studies of the three South American countries–Argentina, Chile and Mexico (Zacharias, Antonopoulos and Masterson, 2012) time deficit before employment is lower than among employed people but still relevant. In Argentina 25 percent of non-employed women are time poor; in Chile 19 percent; and in Mexico 34 percent. In Italy the time poverty rate among non-employed women varied between 4 and 2 percent in 2008–2014. The time poverty rates of non-employed men are much lower everywhere: 1 percent in Italy; 1 or 2 percent in Chile and Mexico; 10 percent in Argentina.Footnote 25

The data in Fig. 1 highlights that time poverty increases for both men and women when the number of hours of employment are taken into consideration, but with a fairly wide gender gap to the disadvantage of women. This result underlines how, when keeping the number of hours of paid work equal for men and women, it is the amount of hours of unpaid care and domestic work that determines the higher time poverty rate among women compared to men.

The comparison between the two years analyzed in the study highlights that in 2014 the percentage of time-poor employed persons increased. The widest difference is recorded for men employed between 51 and 60 weekly hours. For this category time poverty rose from 39.4 to 66.5 percent. This change resulted in a shrinkage of the time poverty gender gap for those persons that are employed 51 or more weekly hours.

The depth of time poverty is an additional feature provided by the LIMTIP. To estimate the depth of time poverty, the hours of necessary household production are subtracted from the hours of available time (the time left after subtracting the minimum necessary time for personal care and leisure and the hours of paid work). Table 5 presents time deficits by household composition and number of hours of paid work. For adults employed full-time weekly time deficits are on average around 12 h for women and 4 h for men. The results confirm that among people that are employed for fewer hours (results for part-time workers are presented in the lower part of Table 5), time poverty is less present and, generally, narrower.Footnote 26

Persons employed full-time (30 or more hours per week, presented in the upper part of Table 5) report a deeper and more consistent time poverty compared to those employed part-time. However, the trends differ between women and men. For men, with the single exception of non-parents, the presence of additional adults in the household decreases the depth of their time deficits–larger for single parents and smaller for parents that live with at least one adult. For women, the results highlight the opposite trend. Single women, including parents, have smaller time deficits than women who live with at least one other adult.

The second relevant result is linked to the extent of income poverty. Standard poverty analysis highlights that 19.7 percent of the population in Italy were at risk of poverty in 2014. The incidence of poverty increased by almost two percentage points from 2008 (when it was equal to 18 percent). Considering time deficits and the ability to purchase market substitutes, 23.3 percent of the population lived in a poor household (see Table 6). Thus, when the new poverty threshold is introduced, an additional 3.6 percent of the population moves below the poverty line. In previous LIMTIP studies this phenomenon was called hidden poverty because if we do not take into account the necessary household production and the time that it requires, the condition of these persons looks good enough to statistics. It should be noted that between 2008 and 2014, not only did the percentage of persons at risk of poverty based on standard poverty analysis increase (from 17.95 to 19.7 percent), but hidden poverty also rose (from 3.2 to 3.6 percent).

The international comparison of the results confirms the findings for Italy. In Argentina 11.1 percent of the population falls below the time-adjusted poverty line, compared to 6.2 percent for the official poverty line. For Chile, adjusting for time poverty increases the poverty rate to 17.8 percent from 10.9 percent for the official poverty line. In Mexico, the poverty rate increases to 50 percent from an already high 41 percent.

From a gender perspective, in Italy more than half of the persons who live in a poor household are women (around 55 percent). This result is confirmed both by standard poverty measures and by the LIMTIP. While a focus on hidden poverty highlights that there are slightly more men (around 52 percent) than women among the hidden poor persons.Footnote 27 In the households that are officially at risk of poverty, 11.2 percent of adults are time poor (6.5 percent are women and 4.7 are men), of these around 1.5 percent are unemployed or inactive (almost all of them are women). The remaining 9.7 percent are employed.

When the poverty threshold is adjusted taking into account the replacement cost of time deficits, the depth of poverty increases with respect to the official poverty line and it reflects household composition.Footnote 28 As the current study highlights, households with children have larger time deficits. These are reflected in a decreased disposable income–or a lower poverty threshold. Between 2008 and 2014 there was a rise in poverty, both in terms of the number of poor households and in terms of the magnitude of the poverty these households suffer (see Table 7). The estimates show that in 2014, the average monthly income deficit for households with children was almost 10 percent higher in the LIMTIP than the official income deficit–4005 euros compared to 3654 euros. This is confirmed by international LIMTIP studies. The estimates for South America showed that the average LIMTIP income deficit for poor households was 1.5 times the official income deficit in Argentina and Chile, and 1.3 times in Mexico. While the estimates for Korea highlighted that the average monthly LIMTIP income deficit for all poor households was 1.8 times the official income deficit.

The impact that time deficits have on poverty for households in lower income quintiles might be overwhelming in relation to their earnings. At the individual level, the impact can be assessed by considering the ratio of monetized value of the time deficits–the same that is employed for adjusting the poverty threshold–to net wagesFootnote 29 for persons employed 30 or more weekly hours (Fig. 2). In 2014, in order to cover her time deficit, the average female worker in the bottom income quintile would have had to spend almost 90 percent of her earnings on purchasing market substitutes. Even for those women in the second and middle-income quintile the ratio remains around 40 percent. In contrast, the ratio for men is lower for all income quintiles, on average 17 percent of their net wages.

There are two explanations for this result. The first one is related to the size of time deficits. As reported in Table 5, time deficits for women working full-time are on average larger than men’s, except for single parents. The second explanation regards the level of salaries. Data highlights that on average the net wages of women employed full-time are 6.3 percent lower than those of men.

In conclusion, the LIMTIP analysis for Italy presents three main findings. First, more women than men suffer from time poverty. Between 2008 and 2014 the gap in time poverty between women and men decreased due to a slight decrease in time poverty among women and an increase among men. Time poverty rises for both men and women as the number of hours of employment increases, but with a fairly wide gender gap to the disadvantage of women. This finding demonstrates how the higher time poverty rate among women compared to men is determined by the amount of unpaid care and domestic work, even after adjusting for the number of hours of paid work for men and women.

Second, households with children have larger material difficulties, and this is due partly to the higher amount of time for minimum necessary household production that these households have and partly to the unequal distribution of unpaid care and domestic work between the partners.

Third, the impact that time deficits have on poverty for households in lower income quintiles might be overwhelming in relation to their earnings. The conflict between the value of household production and the wage that one could earn in the labor market clearly emerges. In Italy women employed full-time who belong to a household in the bottom quintile of the income distribution earn on average just enough to cover the cost of the time deficits that their employment creates. If working conditions for low skilled workers are poor and publicly provided care services–that would partially lift the burden of necessary unpaid work–are scarce, certain categories, especially families with children, can hardly escape from poverty.

5 Conclusions

Economists recognize the importance of multidimensional poverty measures. Among the different dimensions of poverty, time poverty highlights the importance of unpaid work to the daily reproduction of household members. Among the previous attempts to measure time and income poverty in a single measure, Harvey and Mukhopadhyay (2007), Bardasi and Wodon (2010) and Zacharias (2011) focused on unpaid care and domestic work and household production. The LIMTIP, that is empirically reviewed for the first time in this article, presents two main advantages. It monetizes time deficits and employes them for adjusting the monetary poverty threshold. It gives attention to important intrahousehold disparities in terms of household responsibilities by taking into account the actual shares of household members in unpaid care and domestic work when estimating time deficits at individual level.

The main limit that the LIMTIP suffers from is represented by the impossibility of measuring income poverty at individual level. The inability to categorically define the share of household income available to each person in the household leads the LIMTIP to assume the option of complete pooling. Attempts to estimate the intrahousehold sharing of resources (Dorn et al., 2023) are interesting but they could also be misleading, because they can at best represent approximations.

The international comparison between the study on Italy and previous LIMTIP studies confirms that in general time poverty affects women more than men, both in terms of incidence of time poverty and depth of time poverty. The official poverty lines underestimate the impact of time deficits. When time deficits are considered, the share of poor households among the population is considerably higher. The difference between the official poverty line and the LIMTIP threshold is lower in Italy compared to previous LIMTIP studies. This is due to the fact that for the current estimation the lowest replacement cost for time deficits was adopted. It remains outside of the scope of this study to compare different replacement costs. These should be analyzed in future research.

Date Availability

Time and income poverty measurement. An ongoing debate on the inclusion of time in poverty assessment.

Notes

See, for example, the theory on the investment in human capital developed by Mincer (1958).

Free time has been defined also as ‘discretionary time’ (Goodin et al., 2008), and it can become the measure for the temporal autonomy that one can enjoy.

For example, in the EU (Addati et al., 2018) on average women spend almost double the amount of time in unpaid work than men. In fact, women spend on average 4 h and 26 min per day in unpaid work, while men spend only 2 h and 23 min, representing an average gender gap in unpaid work of more than 2 h. Italy presents one of the most unequal divisions of unpaid work between women and men. In Italy women spend on average 5 h and 5 min per day in unpaid work, while men spend only 1 h and 48 min, representing—after Portugal – the highest gender gap in the share of total unpaid work (23.8%) among the EU countries.

Feminist scholars challenged the mainstream economics paradigm that paid employment is the exclusive mode of securing a living for oneself and one’s family. Feminist theory considers the importance of non-market activities —from care work to subsistence production— that form the prerequisites for labor market activities, putting the emphasis on reproduction. In particular, they highlighted the role of unpaid work in the extension of monetary income in the form of expanded living standards (i.e. cooked food, washed clothes), and in the expansion of extended living standards in the form of an effective welfare conditions (i.e. ensuring that children go to school, assuring well-being to specific people) (Picchio, 2003). In other words, you cannot feed banknotes to babies, but through unpaid work you need to transform income into goods and services for family members.

Non-substitutable household production does not refer to any activity in particular, but more generally to that minimum share of household activities that, in any case, will not be externalized. Vickery (1977) assumes that even where the maximum substitution of money for nonmarket time has been made, there is a minimum amount of time necessary for the overall management of the household and the supervision of those hired to perform the necessary tasks.

The process through which the thresholds for this study have been built will be explained in Sect. 4.

In the empirical application of the LIMTIP it is impossible to apply the individual share of non-substitutable household production (α), because it is not possible to distinguish in the data the part of household production that is substitutable from the part that is not. Therefore, a minimum threshold of non-substitutable household production that is the same for every adult person in the household is defined.

How the minimum necessary time is calculated is presented in Sect. 4.

For a description of the specific activities that are included for making the estimates see the case study in Sect. 4.

The household time deficit equation in the LIMTIP sets the value of time deficit equal to zero for time non-poor households, thereby ignoring the disparities that would exist among such households in the free time available to them. However, Zacharias (2011) highlights that such disparities do not play any role in the definition of the threshold for income poverty, and they also do not matter in drawing the line between time-poor and time-non-poor households.

Employment rates by sex, age and citizenship, Eurostat [lfsa_ergan].

Here the data of the last available wave Italian Time-use Survey (IT-TUS 2013–2014) are analyzed. The IT-TUS is described in Appendix 2.

Unpaid work does not include voluntary work, which is out of the scope of this study.

Excluding voluntary work.

EU-SILC is described in Appendix 2.

For IT-SILC years 2009 and 2015 were selected, because the survey uses the previous calendar year as the income reference period.

The three categories are: (1) care, that relates to all caring activities for other members of the household, such as eldercare and childcare, but also, for example, the time spent taking children to school; (2) procurement, which represents all those activities that involve buying or obtaining all necessary goods and services, like food shopping or going to the post office to pay the bills; (3) core, which includes domestic work such as cleaning, laundering, cooking, etc. All these three categories are grouped under the set of household production.

The hours of required personal maintenance were estimated as the sum of minimum necessary leisure time (assumed to be equal to 14 h per week) and the weekly average of the time spent on essential activities of personal care. It should be noted that 14 h per week was approximately 20 h less than the mean value of the time spent on leisure (sum of time spent on social, cultural activities, entertainment, sports, hobbies, games and mass media). LIMTIP methodology sets the threshold at a substantially lower level than the observed value for the average person in order to ensure that it does not end up “overestimating” time deficits due to “high” thresholds for minimum leisure.

The method assumes that the hours of non-substitutable household activities are equal to 7 h per week. It is not possible to determine from the data how much of the household production is non-substitutable (see footnote 5). For this reason, and in order to be able to compare the results from this study with the results obtained in previous studies, the study adopts the 7 h threshold used in previous LIMTIP analyses, which means one hour per day for each adult person in the household.

After the threshold hours of household production were estimated, the study determined the share of hours of household production of each individual in the household. This was done using the matched data. The method assumes that the share of an individual in the threshold hours would be equal to the share of that individual in the observed total hours of household production in their household. Consider the hypothetical example of a household with only two adult persons, a woman and a man. If the synthetic data show that the two persons spent an equal amount of time in household production, the threshold value of 50 h of household production recorded for households with two adults and no children, was equally divided between them.

The required time for commuting to work has been derived from the time-use survey. The exploratory analysis showed that the hours of employment have an important impact on the hours of commuting – individuals with a higher weekly number of employment hours have on average a higher number of hours of commute. Therefore, it did not seem appropriate to use the average time for employees without taking into account the hours of employment. After analyzing how commuting time varies in relation to the hours of work, an average commuting time (equal to 3 h) for persons working less than 30 h per week and an average commuting time (equal to 4 h) for persons working 30 or more hours has been determined.

For Italy, the study uses as a reference point the “at risk of poverty” measure as defined by Eurostat. Eurostat considers at risk of poverty everyone living in a household that stands below the 60 percent of the median equivalized disposable income. In the EU case, household equivalised disposable income is calculated as follow:

Equivalised household size = 1 + (0.5* number of persons 14 years old and over) + (0.3*number of persons below 14 years old).

Equivalised disposable income = total household disposable income / equivalised household size.

The minimum wage for domestic workers is established by the “Contratto Collettivo Nazionale di Lavoro sulla Disciplina del Rapporto di Lavoro Domestico” (available at the following link: https://www.assindatcolf.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CCNL-15X21-Assindatcolf-2018.pdf). In this estimation the minimum hourly wage for non-cohabiting domestic workers at A level (the lowest), that is equal to 4.57 euros, is used. With contribution and taxation, the total cost of one hour of domestic work is approximately 6 euros. The study uses the minimum wage for an unqualified domestic worker and not specialized wages, as for example in Suh and Folbre (2016), in order to avoid overestimation of poverty.

The increase in time poverty among men could be due to different elements (an increase in the amount of hours of paid work, an increase in men’s share of household production, that could be due to a change in households composition, for example). To disentangle the causes that are at the origin of this phenomenon a specific analysis is needed, but, at this stage, it goes beyond the scope of this work.

For Korea, the study focused exclusively on employed persons.

It is important to notice that in Italy the percentage of men employed part-time is particularly low compared to women (in 2014 the percentage of men employed part-time on total employed men was equal to 7.8, while for women it was 32.8). Part-time employment, annual data, Eurostat [lfsi_pt_a].

The reason of behind this result requires further investigation.

The cost of children increases when we consider the value of time. In their study on equivalence scale estimation adding the time value of different domestic activities to the monetary expenditures, Gardes and Starzec (2018) highlighted that expenditures for children decrease more the level of well-being in full prices terms than in monetary terms, because they cannot be substituted for cheaper expenditures.

The net income corresponds to the gross income component but the tax at source, the social insurance contributions, or both, are deducted, as found in EU-SILC. Here net wages are employed because the represent the part of the salary that the worker can use for covering the cost relative to time deficits.

I refer to head of the household as to the person who responded to the survey, and to the spouse as her/his partner.

References

Addati, L., et al. (2018). Work. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(2), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-011-9181-4

Antonopoulos, R., et al. (2017). Time and income poverty in the city of buenos aires. In R. Connelly & E. Kongar (Eds.), Gender and time use in a global context the economics of employment and unpaid labor (pp. 161–192). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Atkinson, A. B. (2003). Multidimensional deprivation: contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 51–65.

Bardasi, E., & Wodon, Q. (2010). Working long hours and having no choice: time poverty in guinea. Feminist Economics, 16(3), 45–78.

Beneria, L. (1999). The enduring debate over unpaid labour. International Labour Review, 138(3), 287–309.

Beneria, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. S. (2016). Gender, development, and globalization. Economics as if all people mattered (2nd ed.). Rouledge.

Boserup, E. (1970). Women’s role in economic development. St. Martin’s Press.

Dorn, F., et al. (2023). ‘A bivariate relative poverty line for leisure time and income poverty: Detecting intersectional differences using distributional copulas. Review of Income and Wealth [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12635

Eurostat (2016). Methodological Guidelines and Description of Eu-Silc Target Variables.

Gardes, F., & Starzec, C. (2018). A restatement of equivalence scales using time and monetary expenditures combined with individual prices. Review of Income and Wealth, 64(4), 961–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12302

Goodin, R. E., J., et al. (2008). Discretionary Time: A New Measure of Freedom. Cambridge University Press.

Harvey, A. S., & Mukhopadhyay, A. K. (2007). When twenty-four hours is not enough: Time poverty of working parents. Social Indicators Research, 82(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9002-5

ISTAT (2017). Uso del tempo. Periodo di riferimento: anno 2013–2014. Aspetti metodologici dell’indagine.

Kum, H., & Masterson, T. (2010). Statistical matching using propensity scores : Theory and application to the analysis of the distribution of income and wealth. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 35, 177–196. https://doi.org/10.3233/JEM-2010-0332

Masterson, T. (2014). Quality of statistical match and employment simulations used in the estimation of the levy institute measure of time and income poverty (LIMTIP) for South Korea, 2009. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2416850

Merz, J., & Rathjen, T. (2014). Time and income poverty: An interdependent multidimensional poverty approach with German time use diary data. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(3), 450–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12117

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. Journal of Political Economy, 66(4), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/521238

Picchio A (2003) Unpaid Work and the Economy. In: A Picchio (Eds.) New York: Routledge. pp 10–24

Razavi, S. (2007) The Political and Social Economy of Care in a Development Context, Gender and Development Programme.

Rubin, D. B., & Thomas, N. (1996). Matching using estimated propensity scores: relating theory to practice. Biometrics, 52, 249–264.

Suh, J., & Folbre, N. (2016). Valuing unpaid child care in the U.S.: A prototype satellite account using the american time use survey. Review of Income and Wealth, 62(4), 668–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12193

Vickery, C. (1977) ‘The Time-Poor: A New Look at Poverty’, The Journal of Human Resources, 12(1), pp. 27–48. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/145597.

Williams, J. R., Masuda, Y. J., & Tallis, H. (2016). A Measure Whose Time has Come: Formalizing Time Poverty. Social Indicators Research, 128, 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1029-z

Zacharias, A. (2011). The measurement of time and income poverty. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383

Zacharias, A., Antonopoulos, R. and Masterson, T. (2012) Why Time Deficits Matter: Implications for the Measurement of Poverty. Levy Economics Institute.

Zacharias, A., Masterson, T. and Kim, K. (2014) The Measurement of Time and Income Poverty in Korea. Levy Economics Institute.

Acknowledgements

In this study the matching algorithm developed at the Levy Economics Institute has been applied.

Funding

This work was funded by the European PhD in Socio-Economic and Statistical Studies (Sapienza University of Rome).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author does not have any conflicts of interests and or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The stages of the construction of the synthetic datasets Created for estimating the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty (LIMTIP) for Italy in 2008 and 2014 are presented. I use the Italian Indagine Multiscopo sull’Uso del Tempo of 2008–2009 and 2013–2014 (IT-TUS) for time use data and the Italian data of the European Survey of Income and Living Conditions of 2009 and 2015 (IT-SILC) for the information on demographics and income.

1.1 Data and Alignment

Both IT-TUS and IT-SILC are representative at the national level and contain information for individuals for all age classes. IT-TUS 2008–09 has 44,605 observations, representing 59,426,798 individuals when weighted, while IT-SILC 2009 has 51,196 observations, representing 60,108,862 individuals when weighted. IT-TUS 2013–14 has 44,866 observations, representing 60,410,793 individuals when weighted, while IT-SILC 2015 has 42,987 observations, representing 60,843,061 individuals when weighted.

In order to match the most similar observations, I had to select several variables. Following the example of Masterson (2014), I identified a number of strata variables that are relevant for determining the average amount of household production that is required to subsist at the poverty level of income. For this reason, the reference group for household production threshold estimation consists of households with at least one non-employed adult to avoid underestimation of the necessary amount of household production. Strata variables include, at household level, the number of children and of adults, the presence of a non-employed adult, the income category and, at individual level, the sex, and the employment status. Additionally, other variables might be relevant, as, for example, age, citizenship, region of residence, level of education, etc. These additional variables are selected on the basis of their comparability in the two data files.

Therefore, first of all, I extensively worked on the two separate files in order to align the common variables in terms of definition and measurement. For example, in IT-TUS the only income information present is the main source of income at individual level. Therefore, based on the categories provided by the variable in the IT-TUS, I constructed a corresponding variable in the IT-SILC where, instead, I found detailed information about different sources of income, both at household and individual level. I proceeded according to this principle until I harmonized all the definitions of strata and relevant variables.

Then, to maximize the matching quality, I checked that the distributions of the common variables were comparable. I expected comparable distributions because both data sets have a large number of observations and they are both nationally representative. When common variables did not align, then I doublechecked the definitions and harmonized them, where possible. I found an excellent comparability for all the selected variables (see Tables 8 and 9 below). After the harmonization, I adjusted the sum of the attached weights for records, in order to make them comparable.

1.2 Matching

At this point I need to transfer the variables related to time use from the IT-TUS to the IT-SILC. Considering which are the factors that mostly affect the variation of the amount of unpaid care and domestic work, I divided the reference group into 12 subgroups based on the number of children (0, 1, 2 and 3 or more) and the number of adults (1, 2 and 3 or more).

According to the selected strata variables (the number of children in the household, the number of adults in the household, the presence of a non-employed adult in the household, the marital status, the presence of children under 3 years of age in the household, the sex, the main source of income, the activity status and the number of earners in the household), I separated the data within each file in 38,400 discrete cells.

Then I carefully selected the common variables in the logistic regression model for propensity scores in order to maximize the explanatory power. In the end, my selection of relevant variables included, besides the strata variables: age, level of education, being in education, having a second job, citizenship, region, household tenure, head of the household, spouse.Footnote 30

After running the model, all records for each file were sorted by estimated propensity score and attached weight. For every recipient in the recipient file (IT-SILC), an observation in the donor file (IT-TUS) was matched with the same or nearest neighbour, based on the rank of their propensity scores. In this match, a penalty weight is assigned to the propensity score according to the size and ranking of the coefficients of strata variables not used in a particular matching round (see Tables 10 and 11 below). Under this sorting scheme, I assigned records with larger weights in the donor file to multiple records in the recipient file until all of their weight has been used up.

1.3 Test of Quality of Matching

In order to check the quality of the matching I compared the marginal and the joint distributions in the matched file and in the donor file (see Tables from 12, 13, 14, 15 below). The constraints of the matching scheme should lead to identical marginal distributions, and the joint distribution of variables not jointly observed should be nearly the same.

Therefore, I checked that the mean and the median values for the transferred variables by each strata variable were similar in the matched and the donor files. Specifically, I checked if there were discrepancies in time devoted to unpaid care and domestic work by type of household and sex of the individual. The ratio of the average time spent by women and men for different household activities in the matched file, to the average value in the donor file and the distribution of weekly hours of unpaid care and domestic work for each of the 12 cells, differentiated by number of adults in the household and number of children in the household (see figures from 3, 4, 5, 6 below), give confidence that the marginal distributions have been well preserved in the statistical matching process. Divergences are related in particular to the limited number of observations with three or more children.

Appendix 2

2.1 IT-TUS

The Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) regularly collects data on time use from 2002. The IT-TUS (ISTAT, 2017) is carried out every five years and it is composed of three questionnaires: the individual questionnaire contains general information on family members and their household, the daily diary records the daily use of time of all members aged three years or more, and the weekly diary records, and the hours of paid work for all members that hold a job. Individuals are required to fill in the daily diary for week-days, Saturdays, and Sundays randomly. Sample weights are used to obtain statistics representative of the whole Italian population. Activities are classified in 10 groups: physiological needs, professional work, education activity, household activities, voluntary work in organizations and beyond, social life and entertainment, sport and recreation activities, personal hobbies, using mass-media, time spent on moving and transportation. This classification enables a detailed analysis of the time each household member spends on each activity. The Italian time use survey does not include information on income and earnings.

The population of interest in the Italian Time Use survey is composed of households residing in Italy and the individuals who make them up; people residing in cohabitation institutions are excluded. The family is understood as a de facto family, i.e. a set of cohabiting people linked by marriage, kinship, affinity, adoption, guardianship or emotional ties.

The study domains, i.e. the areas with respect to which the population parameters being estimated are referred, are of two different types: territorial-type domains and temporal-type domains.

The territorial domains are as follows:

-

the entire national territory;

-

the five geographical divisions (North-Western Italy, North-Eastern Italy, Central Italy, Southern Italy, Insular Italy);

-

the geographical regions (with the exception of Trentino Alto Adige whose estimates are produced separately for the provinces of Bolzano and Trento);

-

the municipal typology obtained by dividing Italian municipalities into six classes based on socio-economic and demographic characteristics:

-

A)

municipalities belonging to the metropolitan area divided into:

-

A1 central municipalities of the metropolitan area: Turin, Milan, Venice, Genoa, Bologna, Florence, Rome, Naples, Bari, Palermo, Catania, Cagliari;

-

A2 municipalities that gravitate around the central municipalities of the metropolitan are

-

-

B)

Municipalities not belonging to the metropolitan area divided into:

-

B1 Municipalities with up to 2,000 inhabitants.

-

B2 Municipalities with 2,001–10,000 inhabitants.

-

B3 Municipalities with 10,001–50,000 inhabitants.

-

B4 Municipalities with over 50,000 inhabitants.

-

As far as temporal domains are concerned, the estimates produced by the survey are published with reference to four types of day: weekday, day before a holiday (Saturday), public holiday (Sunday) and average weekly day.

The sampling design is complex and makes use of two different sampling schemes, both based on a cluster structure of the population in municipalities and families. Within each of the domains defined by the intersection of the geographical region with the six areas A1, A2, B1, B2, B3 and B4, the Italian municipalities are divided into two subsets on the basis of the resident population:

-

1-

the set of self-representative municipalities (which we will indicate from now on as AR municipalities) made up of the municipalities with the largest demographic size;

-

2-

the set of non-self-representative municipalities (or NAR) made up of the remaining municipalities.

Within the set of AR municipalities, each municipality is considered as a separate stratum and a design known as cluster sampling is adopted. The primary sampling units are represented by registry families, systematically extracted from the registry office of the municipality itself; for each family included in the sample, the characteristics under investigation of all the de facto members belonging to the same family are recorded.

Within the NAR municipalities, a two-stage design is adopted with stratification of the first-stage units. The first stage units (UPS) are the municipalities, the second stage units are the households (USS); for each family included in the sample, the characteristics under investigation of all the de facto members belonging to the same family are recorded.

Municipalities are selected with probabilities proportional to their demographic size and without repetition, while households are extracted with equal probabilities and without repetition.

For the definition of the overall sample size and its allocation among the different territorial domains, it was decided to adopt a mixed perspective based both on cost and organizational criteria, and on an assessment of the expected sampling errors of the main estimates with reference to each of the territorial domains of interest.

The theoretical sample size at the national level was essentially set at based on cost and operating criteria and is equal to approximately 21,000 families and 500 municipalities. The allocation of the sample of families and municipalities among the various regions was then defined adopting a compromise criterion such as to guarantee the reliability of the estimates both at the national level and at the level of each of the territorial domains.

EU-SILC

EU-SILC (Eurostat, 2016) is a multi-dimensional dataset focused on income but at the same time covering housing, labour, health, demography, education and deprivation, to enable the multidimensional approach of social exclusion to be studied. It consists of primary (annual) and secondary (ad hoc modules) target variables, all of which are forwarded to Eurostat. The primary target variables relate to either household or individual (for persons aged 16 and more) information is grouped into areas: at the household level basic/core data, income, housing, social exclusion and labour information; at the personal level basic/demographic data, income, education, labour information and health. The secondary target variables are introduced every four years or less frequently only in the cross-sectional component. Data are based on a nationally representative probability sample of the population residing in private households within the country, irrespective of language, nationality or legal residence status. All private households and all persons aged 16 and over within the household are eligible for the operation. According to the Commission Regulation on sampling and tracing rules, the selection of the sample is drawn according to the following requirements:

For all components of EU-SILC (whether survey or register based), the cross-sectional and longitudinal (initial sample) data shall be based on a nationally representative probability sample of the population residing in private households within the country, irrespective of language, nationality or legal residence status. All private households and all persons aged 16 and over within the household are eligible for the operation.