Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze the relationship between economic and social performance in an organizational context. We perform a meta-analysis to test this relationship and to examine the influence of the measurement criteria and organizational characteristics, such as activity, social orientation, technology and cultural environment. We find 678 effect sizes in 83 papers. Our results reveal a positive relationship between economic and social performance, although differences in the sign are detected depending on the measurement instrument and the type of organization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Currently, organizations are developing a growing interest in promoting socially friendly activities. Michelon et al. (2013) identify advantages of an organization deciding to promote these activities, such as improvement in its legitimation and reputation, a better relationship with its stakeholders and the promotion of skills, processes and systems that increase the organization’s competitiveness. These advantages are translated into the ability to generate social and economic performance. As a consequence, one of the most interesting topics studied in the literature is the relationship between an organization’s economic and social performance.

The aim of this paper is to determine the existence and nature of the relationship between economic and social performance in the organizational context. Although the concepts of social and economic performance were originated in socioeconomic research more than 20 years ago, there are no generally accepted definitions, measurements or descriptions of the interactions between them (Felício et al. 2013; Bellostas et al. 2016).

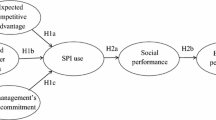

This paper develops a meta-analysis of the relationship between economic and social performance. Meta-analysis is an appropriate statistical approach to use when multiple individual studies have yielded inconclusive or conflicting results, as in the case of this relationship (Waddock and Graves 1997; Rosenthal and DiMatteo 2002; Orlitzky et al. 2003; Wu 2006). We propose the treatment of the measurement criteria of economic and social performance and the characteristics of the organization as elements that can condition this relationship. Orlitzky et al. (2003) and Margolis et al. (2007) analyzed some of these aspects approximately 10 years ago. However, in the last few years, there has been a strong progress in this research field with the creation of new measurement criteria or indicators of economic and social performance. This paper introduces these new criteria and analyses its influence in the relationship between economic and social performance in different types of organizations. The influence of these new elements has not been studied by the previous economic literature up to date. As our main contribution, we statistically aggregate extant evidence concerning the claim that social performance interacts with the economic performance of an organization. Second, we test a central assertion of instrumental stakeholder theory, i.e., that there is a positive interaction between the two types of performance. Moreover, we investigate whether the relationship varies based on the distance between performance measures and characteristics of the organization. In particular, those measurements of social performance that include the degree of satisfaction of stakeholders promote higher interaction between both types of performance. Something similar happens when the organization is oriented to service delivery or belongs to an intensive technology sector. Finally, we note that organizations must design and integrate relevant definite indicators in their strategic management practices and that researchers should be careful in drawing conclusions because they could be influenced by the abovementioned elements.

This paper is organized into five sections: The first section is the introduction. The second section defines the various research questions posed in this paper. The third and fourth sections introduce the methodology and the results, respectively, to answer the proposed research questions. In the fifth section, we discuss the results. The last section provides conclusions based on the results obtained.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Interaction Between Economic and Social Performance

The link between economic and social performance has been a core topic in the management literature for years (Schaltegger and Synnestvedt 2002). Corporate social responsibility and socially friendly activities have been understood as an alternative way of generating economic and social welfare (Godfrey and Hatch 2007). These practices imply the creation of social value from different initiatives. Traditionally, business companies, cooperatives and mutuals created social value through the market, whereas other types of nonprofits, such as foundations or associations, created social value outside the market system (Sanzo et al. 2015; Costa and Carini 2016). Nowadays, all these organizations have an active role in markets, competing between them to obtain users and financial resources, although with a different social orientation or strategy (Chaves and Monzón 2012).

Despite the large number of academic contributions, the links between social and economic performance remain unclear (Brammer and Millington 2008; Hahn and Figge 2011; Orlitzky et al. 2003; Waddock and Graves 1997; Wu 2006). Aupperle et al. (1985) and, more recently, McWilliams et al. (1999) and McWilliams and Siegel (2001) find no empirical relationship between economic and social performance in companies with a social orientation. By contrast, Waddock and Graves (1997), Kinnell and McDougall (1997), Blois (1999) and Sargeant (1999) detect a positive relationship between a proxy of social value and accounting measurements of economic value, whereas Abiodun (2012) detects a negative relationship between investment in social activities and economic return. Taking into account the conflicting results reached by previous studies, we propose the following research question:

RQ 1 : Is there a significant relationship between economic and social performance?

If there is a significant relationship, the results will be in line with Preston (1978), Freedman and Stagliano (1991), Graves and Waddock (2000), Berman et al. (1999), Van de Velde et al. (2005) and Wu (2006). These authors all find a relationship between economic and social performance. The sign of this relationship could be influenced by the measurement criteria and the indicators used by different authors to analyze this relationship. In the context of corporate social responsibility, Orlitzky et al. (2003) study the importance of measurement criteria as influential variables. Bellostas et al. (2016) also detect a lack of agreement among academic researchers concerning the composition and measurement of both types of performance. Moreover, in the last few years, both new types of organizations with social orientation and measurement criteria of performance have emerged in the economic arena (López-Arceiz et al. 2016). However, the impact of these criteria and the behavior of new hybrid organizations have not been studied yet. Thus, correlations between the economic and social performance constructs can be influenced by these new factors.

2.2 Measurement Strategies for Economic and Social Performance

The interaction between economic and social performance can be influenced by the measurement criteria adopted in each research project, being a lack of consensus about the operational level (Yang et al. 2014; Testi and Bellucci 2011).

In this sense, the measurement of economic performance is not free of challenges. Economic performance supposes that stable and continuous economic activities are being conducted. The question is how to measure an organization’s economic activity. Orlitzky et al. (2003) proposed three broad subdivisions of economic performance: market-based (investor returns), accounting-based (accounting returns), and perceptual (survey) measurements. Market-based and accounting-based measurements constitute a partial perspective because they recognize only the consumer and the producer or owner of a company as legitimate stakeholders (Payne et al. 2000; Johansen and Nielsen 2012; Nishimura 2007; Fontaine et al. 2006; Freeman 1984). In this case, traditionally the most used criterion has been the accounting return, but nowadays sales or asset growth are more important in some entities such as nonprofit organizations (Liu et al. 2012; Coombes et al. 2011; Bai 2013). Something similar happens with perceptual measures. These measures are based on the answers of a person who can give a subjective evaluation (Conine and Madden 1986; Reimann 1975). The perceptions of managers are being used as a source in the measurement of economic performance because managers have access to the entity’s economic targets (Brouthers 2002; Liu et al. 2012). Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that the measurement criteria of economic performance chosen by the researcher can influence the relationship between economic and social performance. For instance, Lu et al. (2014) evidenced a negative effect of the market measurements. These indicators tend to consider all the available information, while accounting indicators are the result of the organizational accounting policy. Then, currently, the traditional criteria, compiled by Orlitzky et al. (2003) and Margolis et al. (2007), live together with new measurement criteria, such as subjective measurements and growth or size criteria. These new measurements can be able to influence positively the interaction between economic and social performance according to Santos and Brito (2012) or Bai (2013) (Table 1). Therefore, we define the following research question:

RQ 2 : Does the relationship between economic and social performance depend on the measurement criterion of economic performance?

If there is no influence of the measurement criteria of economic performance, we can assume that although there is no consensus in the measurement criteria of economic performance, there is a general agreement about the meaning of economic performance (such as return, growth or perception). Conversely, if we observe an influence of these criteria, economic performance should be considered a multidimensional construct with different dimensions that the researcher must consider (Moneva and Ortas 2010).

This idea is relevant when we analyze the measurement criteria of social performance. In general terms, social performance refers to the generated impact on stakeholders affected by the organization. Lu et al. (2014), Orlitzky et al. (2003) and Post (1991) identify four strategies for measuring social performance: (a) Social performance disclosure; (b) Social performance reputation ratings; (c) Social audits, social performance processes, and observable outcomes, and (d) Managerial social performance principles and values. Social performance disclosure is a criterion based on public information (annual reports, letters to shareholders, etc.). Although this is the most objective criterion, information disclosure by itself is only a proxy of social performance and may be insufficient to study this element in its entirety (Farneti and Guthrie 2009). The second and third approaches are related to systematic third-party efforts to assess a firm’s ‘objective’ social performance behaviors, such as community service, environmental programs, and corporate philanthropy. For this criterion, the main problem is the comparability of the information. If the initiative does not publish the social audit process, the comparison will not be feasible, and the usefulness of this criterion will be low (Gao and Zhang 2001, 2006). The fourth criterion assesses the values and principles inherent in an organization’s culture (Aupperle 1984; Carroll 1979). This criterion is a broad category with a high level of subjectivity because it is based on the perceptions of the individual who evaluates these values and principles.

Although these authors made an important effort when they studied these measurement strategies, additional criteria should be considered at present. For example, service quality can be an indicator of the level of integration of stakeholders’ needs into the organization (Mitchell et al. 1997; Sacchetti et al. 2016). Furthermore, community interests or regional development are proxies of this integration when the entity promotes higher levels of growth in that area (Borzaga and Fazzi 2000). Other authors have developed indicators, such as social return on investments that offer a specific vision of social performance (Rotheroe and Richards 2007). Finally, social auditing and social indexing are not available in all cases because some entities are easier to access than others. Table 1 shows negative influences when the measurement criterion uses the third-party assessments. Moreover, the new criteria would be able to change the interaction between economic and social performance. Millar and Hall (2013), in relation to the social return on investment, suggest a tendency to obtain positive relationships. Bai (2013) in relation to social auditing identify negative interactions in the context of nonprofit organization which are not table to participate in social indexing. All these particularities can modify the relationship between economic and social performance. These new aspects have not been studied by the previous meta-analysis. As a consequence, we propose the following research question:

RQ 3 : Does the relationship between economic and social performance depend on the measurement criterion of social performance?

Finally, some organizational characteristics, which can act as control variables, influence the relationship between economic and social performance. Deegan and Gordon (1996) and García-Ayuso and Larrinaga (2003) identify a strong influence of the type of developed activity on the relationship between economic and social performance. The social orientation of the organization is also a variable that can modify this relationship. According to Felício et al. (2013), entities that adopt a legal form closer to nonprofit organizations will have a stronger social orientation and will be able to create a more intense relationship. However, other authors, such as Bai (2013), Bouckaert and Vandenhove (1998) and Weisbrod (2009), propose that although nonprofit organizations have an explicit social aim, self-dealing and market competition can prevent these entities from reaching an optimal level of social performance. The level of technology required by the organization also determines this relationship. In this sense, Guadamillas et al. (2010) and Morfit (2014) state that entities belonging to technological sectors are the ones that provide more information to their stakeholders and, as a consequence, are able to create a more intensive relationship between economic and social performance. Other characteristics that can influence this relationship are the cultural environment of the organization. Defourny and Nyssens (2008), Kerlin (2006), Quintão (2007) and Hulgård (2010) show that the impact of socially friendly activities varies based on the diversity of experiences at a regional level and is affected by the prevailing cultural backgrounds. As a consequence, the prevalent sphere of values will promote the development of a more intense relationship between economic and social performance (López-Arceiz et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016).

RQ 4 : Organizational characteristics are a moderator variable of the relationship between economic and social performance.

The previous three research questions allow the relationship between economic and social performance to be tested from different perspectives to determine the extent to which economic and social measurements and the characteristics of the entity influence the behavior of organizations that decide to develop a “double bottom” strategy.

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample and Indicators Used

Searches of the Web of Science, Scopus, and ABI/Inform, databases were conducted using the keyword ‘organizational performance’. Synonyms, which were searched separately, were ‘organizational performance’, ‘profitability’, ‘economic performance’, ‘financial performance’, and ‘economic value’. The keyword ‘social performance’ was alternately substituted with ‘(corporate) social responsibility’ and ‘social value’. Web of Science gives access to the full text and images of more than four million business and trade journal articles, with a coverage period of one hundred years. Scopus indexes abstracts of journal articles (approximately 57 million references) and books (approximately 100,000 references). To increase the scope of our search, cross-citations from previous reviews (for example, Orlitzky et al. 2003; Margolis et al. 2007) were also explored.

The relevant studies selected for the meta-analysis had the following characteristics, and these were the selection criteria:

-

The studies referred to concepts associated with socially responsible businesses, social enterprises and nonprofit organizations.

-

The analyzed studies quantitatively examined the relationship between economic and social performance. The reported effect size could be Pearson’s correlation r, a t test statistic or an effect size (Hunter and Schmidt 1990).

-

The studies were concerned with at least one aspect of a firm’s economic performance. To study the different aspects, we distinguished between five possible criteria based on the theoretical framework (Moneva and Ortas 2010): (a) Accounting measurements, (b) Market criteria, (c) Economic aim management or perceptual indicators, (d) Size or growth criteria, and (e) Other measurements. We identified indicators that had a frequency of one in our database search as ‘other’ (for instance, the level of intangible assets).

-

The same procedure was used for social performance.Footnote 1 According to the previous economic literature, we considered seven possible indicators: (a) Professional integral audit based on social performance disclosure (e.g., KLD), (b) Stakeholder integration (e.g., managerial social performance), (c) Service quality, (d) Social auditing/indexing (e.g., reputational measurements), (e) Regional development criteria, (f) Created social value criteria (e.g., social return on investments), and (g) Other criteria (Wood 1991; Moneva and Ortas 2010). In the ‘other’ category, we included indicators that had a frequency lower than one (for instance, volunteering or networking).

-

Finally, we considered organizational characteristics such as the organization’s activity (raw materials, production of goods or service delivery), its social orientation (based on its legal form), the intensity of its use of technology, and the cultural environment (Anglo-Saxon or continental) in which the organization was framed.

As consequence, we had access to 678 effect sizes from 83 papers.Footnote 2 The Appendix lists the most important study characteristics, such as author(s), date of study, study sample size Ni, observed r (or transformed and/or partially corrected r), number of correlations per study, organizational characteristics and the measurement criteria of economic and social performance.

3.2 Methodology

A meta-analysis integrates the quantitative findings of separate but similar studies and provides a numerical estimate of the overall effect of interest (Petrie et al. 2003).Footnote 3 This meta-analysis uses Hunter and Schmidt’s (1990) statistical aggregation techniques for cumulative correlations and to correct for various study artefacts to estimate the true score correlation (ρ) between economic and social performance. The meta-analysis arrives at a mean true-score correlation by correcting observed correlations for sampling error.Footnote 4 Because sampling error varies directly with sample size, all studies are weighted by sample size Ni (Schmidt and Hunter 1977). Studies with a smaller standard error and larger sample size are given more weight in the calculation of the pooled effect size.Footnote 5

Agreement or disagreement between the studies can be examined using a heterogeneity test. In this study, we use Cochran’s Q. This statistic is the weighted sum of squares on a standardized scale. It is reported with a p value, where low p values indicate the presence of heterogeneity (Higgins et al. 2003). To test the relationship between economic and social performance, we specify a meta-regression model to study the role of the measurement criteria of economic and social performance. In this model, we have added the influential variables, such as dummy variables, following this expression (1):

where ρij is the effect size, Dij represents each influential variable (economic and social performance measurement criteria and organizational characteristics), and \(\varphi_{ij}\) is the random error. Parameter \(\beta\) measures the effect of the moderator elements on the effect size. We use the software SPSS 22.0 and Stata 14.0 to estimate the different models.

Finally, we have implemented a bootstrap estimation (number of samples: 10,000) in order to robust the obtained results. A bootstrap estimation allows us to obtain a set of uniform subsamples based on the total sample, the original model being tested in each one. Moreover, we have re-estimated the model using the Bayesian estimator. The Bayesian estimator is suitable in a meta-analysis when we have finite sample sizes and we introduce prior information based on previous research. Both techniques enable us to robust the previous results.

4 Results

As shown in the first line of Table 2, the mean observed correlation for the total set of 678 correlations (k) and the total sample size (N) of 1,368,044 observations is 0.188, with an observed standard deviation of 0.289.

As Table 2 shows, Cochran’s Q coefficient has a p value lower than 5%, which indicates the presence of heterogeneity in the studied sample. Therefore, we decide to use a random effects meta-regression model. Thus, the true (corrected) correlation score is 0.199, which is higher than the observed correlation with a confidence interval at 95% of (0.165–0.232). Therefore, there is positive and significant relationship between economic and social performance among the papers that discuss this relationship. However, this result could be affected by the measurement criteria employed for social and economic performance. Moreover, the control variables related to the characteristics of the studied entities could affect this relationship. For this reason, taking into account the presence of heterogeneity, we decide to include these elements as moderator variables.

In Table 3, we show the impact of the measurement criteria of economic performance on the relationship between economic and social performance. Taking into account the previous literature, we create five measurement sets to examine the moderator effects based on the measurement criteria of economic performance: (a) Accounting criteria, (b) Market criteria, (c) Perceptual criteria, (d) Size criteria, and (e) Other.Footnote 6

Table 3 indicates that the association between economic and social performance depends on the type of measurement used by the researcher to measure economic performance. The size criteria reveals the highest positive correlation between economic and social performance [r: 0.828, CI (0.687–0.908)], whereas other (related to subjective organizational aspects, such as self-values and utilitarian identity) presents the lowest correlation [r: − 0.054, CI (− 0.202 to 0.096)]. Accounting measures are more highly correlated with social performance than market-based measures [r: 0.167; CI (0.147–0.187) vs. r: 0.082; CI (0.071–0.093)]. Finally, perceptual criteria, related to management by targets, show an intermediate behavior [r: 0.129; CI (0.111–0.146)]. Therefore, the relationship between economic and social performance changes when we consider the measurement criteria of the economic dimension.

We also test whether the measurement criteria of social performance may affect the relationship between economic and social performance. The results are shown in Table 4.

To study the measurement of social performance, we distinguish between the following categories: (a) Professional integral audit criteria (e.g., KLD); (b) Stakeholder criteria; (c) Quality criteria; (d) Social auditing/indexing criteria; (e) Regional development criteria; (f) Created social value criteria; and (g) Other criteria.Footnote 7 The results show that the highest correlation occurs when the measurement criteria include the degree of satisfaction among stakeholders [r: 0.221, CI (0.163–0.278)]. By contrast, the lowest value is observed when the researcher decides to entrust in the measurement of a third party [r: 0.072; CI (0.062–0.082)]. In all cases, the correlations are positive, except when the created social value criteria are used [r: 0.215, CI (− 0.044 to 0.447)]. Therefore, the measurement criteria of social performance moderate the relationship between economic and social performance.

The obtained results are robust according to the meta-regression model (Table 5). In all cases, the indicators of each dimension determine the correlation between economic and social performance (p value < 0.05). However, the interpretation of each parameter is different because the β parameter is a measurement of the intensity of the change.

For example, in economic performance, when the paper uses a size criterion, the relationship between economic and social performance is higher (β: 0.158), whereas when the author uses the market criterion, the result is inverse (β: − 0.069). Although we are not able to determine the correlation using this methodology, we can approximate the change in magnitude. Thus, this method is complementary to the traditional meta-analysis. This methodology enables us to determine the influence of different variables. As we can observe, entities whose activity is related to service delivery are able to intensify the interaction between economic and social performance (β: 0.274, β: 0.296). This same pattern is revealed in high-technology organizations (β: 0.214, β: 0.239) in an Anglo-Saxon cultural environment (β: 0.071, β: 0.127). In contrast, socially oriented organizations are not able to promote a more intense relationship between economic and social performance because of the non-significant parameter achieved in the meta-regression (β: 0.019, β: − 0.021). Taking into account this result, a positive correlation between economic and social performance is detected, although this result is affected by the measurement criteria of economic and social performance and organizational characteristics.

This result is consistent with the alternative estimation techniques used in this study (Table 6). The first four columns show the parameters, p values and confidence intervals for the bootstrap estimation, while the second four show the same information for the Bayesian estimator.

As we can observe, there is a positive interaction between economic and social performance, although the final sign depends on the measurement criteria and organizational characteristics. We only attract attention on the improvement in term of goodness-of-fit in the case in Bayesian estimation which robust the obtained results.

5 Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis demonstrate a positive association between social and economic performance across the studied papers. This result contradicts conclusions of McWilliams et al. (1999) and McWilliams and Siegel (2000), who state that economic and social performance are independent spheres in the organizational context. By contrast, our results support the conclusions of Waddock and Graves (1997), Kinnell and McDougall (1997), Blois (1999) and Sargeant (1999), who detected a positive relationship between economic and social performance.

However, this relationship may be influenced by the criteria used in the measurement of economic and social performance and by organizational characteristics. The measurement criteria for economic and social performance have been discussed in previous papers. Brown and Perry (1994, 1995) and Wood and Jones (1995) found that positive correlations may be artefactual functions of the measurement elements. Therefore, we distinguish different measurement indicators in the definition of both types of performance in our meta-analysis. In the analysis of the previous literature, we identified five measurement criteria. Differences in the correlation between economic and social performance are observed in the subjective criteria (other criteria), when the measurement adds elements such as self-behavior or a utilitarian identity. This measurement can cause illogical results because the relationship is based on the opinion of the manager who evaluates the level of economic performance in the entity. This result is also found by Orlitzky et al. (2003), who observe that when the economic performance measurement is based on a survey, the cross-study variation in correlation is removed, and the correlation becomes positive. Measurements based on perceptual criteria are associated with a stronger relationship between economic and social performance according to Santos and Brito (2012) or Peloza (2009). Thus, according Orlitzky et al. (2003), many of the negative findings in individual studies are artefactual, and if the researcher or the company uses a different criterion, positive relationships will appear (Jones and Wicks 1999; Pava and Krausz 1995; Wood and Jones 1995). The meta-regression shows that changes in the measurement criteria used tend to strengthen or weaken this relationship. Measurements that are not associated with efficiency, such as size measurements (sales or asset growth), are able to favor the relationship. However, market criteria introduce a penalization. This same result had been obtained by Goyal et al. (2013). Therefore, the use of a criterion can encourage or discourage the relationship between economic and social performance.

In relation to the measurement of social performance, we have grouped the indicators into seven categories and obtained different intensities in the function of each indicator. The weakest relationship is obtained when the created social value criteria are used. In the meta-regression, we observe that if the researcher decides to change the measurement strategy of social performance, it can influence the interaction between economic and social performance. In this sense, the indicators based on professional integral auditing and social auditing/indexing can decrease the strength of the relationship between economic and social performance. This result diverges from Chen et al. (2015), who obtain a positive interaction in the context of manufacture sector when these criteria are used. In contrast, taking into account the local impact and the regional development may improve this relationship. In any case, similar to the measurement of economic performance, some studies use one measurement and have small sample sizes; therefore, the conclusions in some papers may be biased (Orlitzky et al. 2003).

Finally, the control variables play an important role. The activity of the organization determines the relationship between economic and social performance. Those activities related to the services sector are able to promote a more intense interaction between the two types of performance. This result is obtained by Miles et al. (2014), who demonstrate a stronger relationship in the case of organizations in the sphere of social services. Other control variables also show a positive effect on this relationship. Then, when the entity develops high-technology activities, it is able to create a better interaction, according to Guadamillas et al. (2010) and Morfit (2014). The Anglo-Saxon environment also tends to promote greater interaction (Jackson and Apostolakou 2010). According to these authors, the differences in the institutional context and the level of involvement of stakeholders are the explanations for this behavior. In contrast, the social orientation of the organization does not influence this relationship. Costa et al. (2012) or Bellostas et al. (2016) detect a strong relationship between social and economic performance in Italian social cooperatives and Spanish sheltered workshops, respectively. This result can be explained based on the legal form of the organization, which drives this positive correlation. However, the meta-regression evidences that the social orientation does not influence the relationship between economic and social performance. In this sense, the adoption of professional management criteria in nonprofit organizations and the promotion of socially friendly activities in for-profit organizations has reduced the gap between both types of organizations according to .Chaves and Monzón (2012). So, social performance can be created by hybrid organizations in the market or in the nonmarket, independently of their legal form.

6 Conclusions

The objective of this paper has been to analyze the relationship between economic and social performance in the organizational context. The results show how those entities that develop socially friendly activities experience positive synergies between their social and economic performance. However, some singularities appear when we take into account the measurement criteria of economic and social performance and some characteristics of the organization, such as its activity, its technology and the cultural environment in which it operates. Although some of these indicators had been analyzed by previous studies (Orlitzky et al. 2003; Margolis et al. 2007), the impact of the new measurements of performance and organizational characteristics had not been considered as an influential variable.

Moreover, this paper contributes to the academic debate about the relationship between economic and social performance and shows how it is possible to foster social and economic performance from different strategic organizational models. In fact, a gradual process of convergence occurs in which some non-profit entities tend to develop the economic side in their management model. Similarly, some for-profit entities tend to develop their social side. Currently, there are emerging new models of hybrid organizations that pose a challenge for researchers and managers who need new theoretical frameworks that can explain these models. In any case, it is not possible to provide a universal set of indicators for the measurement of both types of performance due to the observed diversity among the different entities. Therefore, this paper also issues a warning about the use and design of different indicators. In this sense, managers of organizations must design specific indicators that take into account the singularities of the entity. Otherwise, if they follow general indicators, the measurement will be imprecise, and conclusions about the efficiency of the activity will be measured incorrectly.

Finally, this paper has some limitations that should be noted. The aggrupation in different categories of the indicators of economic and social performance is based on previous studies, and it could be different if we analyzed other papers. Moreover, in some selected studies, we have detected small sample sizes, which could influence the extracted conclusions. This fact and the lack of specific indicators are limitations that future research must address.

Notes

We included studies of environmental management and financial performance in the meta-analysis. First, some studies, especially earlier ones, use environmental management as a proxy for social performance. Second, we found stakeholders related to environmental aims (Starik 1995). Finally, the business community tends to regard social responsibility as including both social and environmental performance (for example, BusinessWeek 1999).

We started the research process using this sequence of Boolean operators: (Social performance OR Corporate social responsibility OR Social value) AND (Economic performance OR Profitability OR Financial performance OR Economic value). We obtained 167,132 papers in SCOPUS and 452 in Web of Science. After this process, we added three elements: type of organization (socially responsible business, social enterprise and nonprofit), relationship and correlation. Web of Science offered 16 articles, and SCOPUS offered 83 papers. Those papers from Web of Science were included in SCOPUS.

A meta-analysis takes into account individual studies, but also previous meta-analyses that are introduced with a mean correlation and a SD. Consequently, this technique provides a complete set of information about the studied item.

According to Hofmann et al. (2005), there are three advantages related to the use of the correlation coefficient. First, the accumulation of findings across studies allows for a proper estimation of the mean population correlation being controlled variability. Second, the variance of population can be estimated. Finally, we can model the variability among population through the effect of potential moderators.

To evaluate the publication bias, we use Egger's test for small-study effects. The obtained results do not enable us to reject the null hypothesis (p value > 0.10). Thus, there is a little evidence of this type of bias in the studied sample.

We include in this category indicators with a frequency lower than one: financial sustainability, economic efficiency, economic efficacy, self-values, utilitarian identity, quality of service, organizational satisfaction, organizational success, and volunteer-worker relationship.

We include in this category indicators with a frequency lower than one: promotion of cultural development, existence of pension plans, promotion of research and development, definition of organization values, normative identity, knowledge update, creation of shared value, commitment to stakeholders, community development, and promotion of trust.

References

Abiodun, Y. (2012). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firms’ profitability in Nigeria. European Journal of Economics, Finance, and Administrative Sciences, 45(1), 39–50.

Alsaid, L. (2016). Do consistent CSR activities matter for firm value? Corporate Ownership & Control, 14(1–2), 340–350.

Auamnoy, T., & Areepium, N. (2011). Could corporate social responsibility predict pharmaceutical corporate financial performance? Value in Health, 14(7), 422.

Augustine, D., Wheat, C. O., Jones, K. S., Baraldi, M., & Malgwi, C. A. (2016). Gender diversity within the workforce in the microfinance industry in Africa: Economic performance and sustainability. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 33(3), 227–241.

Aupperle, K. E. (1984). An empirical measure of corporate social orientation. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 6, 27–54.

Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2), 446–463.

Bai, G. (2013). How do board size and occupational background of directors influence social performance in for-profit and non-profit organizations? Evidence from California hospitals. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 171–187.

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304–1320.

Bellostas, A. J., López-Arceiz, F. J., & Mateos, L. (2016). Social value and economic value in social enterprises: Value creation model of Spanish sheltered workshops. Voluntas, 27(1), 367–391.

Berman, S. L., Wicks, A. C., Kotha, S., & Jones, T. M. (1999). Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 488–506.

Blois, K. J. (1999). Trust in business to business relationships: An evaluation of its status. Journal of Management Studies, 36(2), 197–215.

Boesso, G., Kumar, K., & Michelon, G. (2013). Descriptive, instrumental and strategic approaches to corporate social responsibility: Do they drive the financial performance of companies differently? Accounting, Auditing and Accountability, 26(3), 399–422.

Borzaga, C., & Fazzi, L. (2000). Azione volontaria e processi di trasformazione del settore nonprofit. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Bouckaert, L., & Vandenhove, J. (1998). Business ethics and the management of non-profit institutions. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(9–10), 1073–1081.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2008). Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29(12), 1325–1343.

Brouthers, K. D. (2002). Institutional, cultural and transaction cost influences on entry mode choice and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2), 203–221.

Brown, B., & Perry, S. (1994). Removing the financial performance halo from Fortune’s “most admired” companies. Academy of Management Journal, 37(5), 1347–1359.

Brown, B., & Perry, S. (1995). Halo-removed residuals of fortune’s responsibility to the community and environment—A decade of data. Business and Society, 34(2), 199–216.

BusinessWeek. (1999). Social responsibility and shareholder value. 3 May: 85.

Callan, S. J., & Thomas, J. M. (2009). Corporate financial performance and corporate social performance: An update and reinvestigation. CSR and Environmental Management, 16(2), 61–78.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Chaves, R., & Monzón, J. L. (2012). Beyond the crisis: The social economy, prop of a new model of sustainable economic development. Service Business, 6(1), 5–26.

Chen, L., Feldmann, A., & Tang, O. (2015). The relationship between disclosures of corporate social performance and financial performance: Evidences from GRI reports in manufacturing industry. International Journal of Production Economics, 170, 445–456.

Choi, J. S., Kwak, Y. M., & Choe, C. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: Evidence from Korea. Australian Journal of Management, 35(3), 291–311.

Conine, T. E., & Madden, G. P. (1986). Corporate social responsibility and investment value: The expectational relationship. Handbook of Business Strategy, 1987, 1–18.

Coombes, S. M., Morris, M. H., Allen, J. A., & Webb, J. W. (2011). Behavioural orientations of non-profit boards as a factor in entrepreneurial performance: Does governance matter? Journal of Management Studies, 48(4), 829–856.

Costa, E., Andreaus, M., Carini, C., & Carpita, M. (2012). Exploring the efficiency of Italian social cooperatives by descriptive and principal component analysis. Service Business, 6(1), 117–136.

Costa, E., & Carini, C. (2016). Northern and southern Italian social cooperatives during the economic crisis: A multiple factor analysis. Service Business, 10(2), 369–392.

Deegan, C., & Gordon, B. (1996). A study of the environmental disclosure practices of Australian corporations. Accounting and Business Research, 26(3), 187–199.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2008). Social enterprise in Europe: Recent trends and developments. Social Enterprise Journal, 4(3), 202–228.

Dell’Atti, S., Trotta, A., Iannuzzi, A. P., & Demaria, F. (2017). Corporate social responsibility engagement as a determinant of bank reputation: An empirical analysis. CSR and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1430.

Di Zhang, D., & Swanson, L. A. (2013). Social entrepreneurship in nonprofit organizations: An empirical investigation of the synergy between social and business objectives. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 25(1), 105–125.

Dobre, E., Stanila, G. O., & Brad, L. (2015). The influence of environmental and social performance on financial performance: Evidence from Romania’s listed entities. Sustainability, 7(3), 2513–2553.

Esteban-Sanchez, P., de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M., & Paredes-Gazquez, J. D. (2017). Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.127.

Farneti, F., & Guthrie, J. (2009). Sustainability reporting by Australian public sector organisations: Why they report? Accounting Forum, 33(2), 89–98.

Fatemi, A., Glaum, M., & Kaiser, S. (2017). ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Global Finance Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2017.03.001.

Felício, J. A., Gonçalves, H. M., & da Conceição, V. (2013). Social value and organizational performance in non-profit social organizations: Social entrepreneurship, leadership, and socioeconomic context effects. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2139–2146.

Ferrero, I., Fernández, M. A., & Muñoz, M. J. (2016). The effect of environmental, social and governance consistency on economic results. Sustainability, 8(10), 1005.

Fontaine, C., Haarman, A., & Schmid, S. (2006). The stakeholder theory. Martolo: Edlays Education.

Freedman, M., & Stagliano, A. J. (1991). Differences in social cost disclosures: A market test of investor reactions. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability, 4(1), 68–83.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Gao, S., & Zhang, J. (2001). A comparative study of stakeholder engagement approaches in social auditing. In J. Andriof & M. McIntosh (Eds.), Perspectives on corporate citizenship (pp. 239–255). Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Gao, S., & Zhang, J. (2006). Stakeholder engagement, social auditing and corporate sustainability. Business Process Management Journal, 12(6), 722–740.

García-Ayuso, M., & Larrinaga, C. (2003). Environmental disclosure in Spain: Corporate characteristics and media exposure. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting, 32(115), 184–214.

Garcia-Castro, R., Ariño, M. A., & Canela, M. A. (2010). Does social performance really lead to financial performance? Accounting for endogeneity. Journal of Business Ethics, 92(1), 107–126.

Garcia-Sanchez, I. M., Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., & Frias-Aceituno, J. V. (2016). Impact of the institutional macro context on the voluntary disclosure of CSR information. Long Range Planning, 49(1), 15–35.

Godfrey, P. C., & Hatch, N. W. (2007). Researching corporate social responsibility: An agenda for the 21st century. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(1), 87–98.

Goyal, P., Rahman, Z., & Kazmi, A. A. (2013). Corporate sustainability performance and firm performance research: Literature review and future research agenda. Management Decision, 51(2), 361–379.

Graves, S. B., & Waddock, S. A. (2000). Beyond built to last… Stakeholder relations in “built to last” companies. Business and Society, 105(4), 393–418.

Guadamillas, F. J., Donate, M., & Škerlavaj, M. (2010). The integration of corporate social responsibility into the strategy of technology-intensive firms: A case study. Zbornik radova Ekonomskog fakulteta u Rijeci, 28(1), 9–34.

Guo, C., & Brown, W. A. (2006). Community foundation performance: Bridging community resources and needs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(2), 267–287.

Hahn, T., & Figge, F. (2011). Beyond the bounded instrumentality in current corporate sustainability research: Toward an inclusive notion of profitability. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(3), 325–345.

Hamid, K., Akash, R. S. I., Asghar, M., & Ahmad, S. (2011). Corporate social performance, financial performance and market value behavior: An information asymmetry perspective. African Journal of Business Management, 5(15), 6342–6349.

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327, 557–560.

Hofmann, W., Gawronski, B., Gschwendner, T., Le, H., & Schmitt, M. (2005). A meta-analysis on the correlation between the Implicit Association Test and explicit self-report measures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1369–1385.

Hong, J., Zhang, Y., & Ding, M. (2017). Sustainable supply chain management practices, supply chain dynamic capabilities, and enterprise performance. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.093.

Hulgård, L. (2010). Discourses of social entrepreneurship—Variations of the same theme? Working Paper, European Research Network, Denmark.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (1990). Dichotomization of continuous variables: The implications for meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(3), 334.

Inoue, Y., & Lee, S. (2011). Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tourism Management, 32(4), 790–804.

Jackson, G., & Apostolakou, A. (2010). CSR in Western Europe: An institutional mirror or substitute? Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 371–394.

Johansen, T., & Nielsen, A. (2012). CSR in corporate self-storying-legitimacy as a question of differentiation and conformity. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 17(4), 434–448.

Jones, T. M., & Wicks, A. C. (1999). Convergent stakeholder theory. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 206–221.

Jung, K., Jang, H. S., & Seo, I. (2016). Government-driven social enterprises in South Korea: Lessons from the social enterprise promotion program in the Seoul metropolitan government. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(3), 598–616.

Kerlin, J. A. (2006). Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: Understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas, 17(3), 246–262.

Kinnell, M., & McDougall, J. (1997). Marketing in the not-for-profit sector. London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kristoffersen, I., Gerrans, P., & Clark-Murphy, M. (2008). Corporate social performance and financial performance. Accounting, Accountability and Performance, 14(2), 45–90.

Lebovics, M., Hermes, N., & Hudon, M. (2015). Are financial and social efficiency mutually exclusive? A case study of Vietnamese microfinance institutions. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 87(1), 55–77.

Lee, D. D., Faff, R. W., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2009). Revisiting the vexing question: Does superior corporate social performance lead to improved financial performance? Australian Journal of Management, 34(1), 21–49.

Leipnitz, S. (2014). Stakeholder performance measurement in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 25(2), 165–181.

Li, N., Puumalainen, K., & Toppinen, A. (2014). Managerial perceptions of corporate social and financial performance in the global forest industry. International Forestry Review, 16(3), 319–338.

Lioui, A., & Sharma, Z. (2012). Environmental corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Disentangling direct and indirect effects. Ecological Economics, 78, 100–111.

Lisi, I. E. (2016). Determinants and performance effects of social performance measurement systems. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3287-3.

Liu, G., Eng, T. Y., & Takeda, S. (2013). An investigation of marketing capabilities and social enterprise performance in the UK and Japan. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 267–298.

Liu, G., Takeda, S., & Ko, W. W. (2012). Strategic orientation and social enterprise performance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(3), 480–501.

López-Arceiz, F. J., Bellostas, A. J., Moneva, J. M., & Rivera, M. P. (2017). The role of corporate governance and transparency in the generation of financial performance in socially responsible companies. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1080/02102412.2017.1379798.

López-Arceiz, F. J., Bellostas, A., & Rivera, M. P. (2016). The effects of resources on social activity and economic performance in social economy organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(4), 499–511.

Lu, W., Chau, K. W., Wang, H., & Pan, W. (2014). A decade’s debate on the nexus between corporate social and corporate financial performance: A critical review of empirical studies 2002–2011. Journal of Cleaner Production, 79, 195–206.

Makni, R., Francoeur, C., & Bellavance, F. (2009). Causality between corporate social performance and financial performance: Evidence from Canadian firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(3), 409–422.

Maletič, M., Maletič, D., Dahlgaard, J. J., Dahlgaard-Park, S. M., & Gomišček, B. (2016). Effect of sustainability-oriented innovation practices on the overall organizational performance: An empirical examination. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 27(9–10), 1171–1190.

Mallin, C., Farag, H., & Ow-Yong, K. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance in Islamic banks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 103, 21–38.

Mano, R. S. (2014). Networking modes and performance in Israel’s nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24(4), 429–444.

Mano, R. S. (2015). Funding allocations in Israel: An empirical assessment of the new philanthropy approach. Voluntas, 26(5), 2130–2145.

Margolis, J. D., Elfenbein, H. A., & Walsh, J. P. (2007). Does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis and redirection of research on the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Ann Arbor, 1001, 48109-1234.

Matei, L., & Matei, A. (2012). The social enterprise and the social entrepreneurship—Instruments of local development. A comparative study for Romania. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 1066–1071.

McKay, S., Moro, D., Teasdale, S., & Clifford, D. (2011). The marketisation of charities in England and Wales. Voluntas, 26(1), 336–354.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2000). CSR and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 603–609.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D., & Teoh, S. H. (1999). Issues in the use of the event study methodology: A critical analysis of corporate social responsibility studies. Organizational Research Methods, 2(4), 340–365.

Mendoza-Abarca, K. I., Anokhin, S., & Zamudio, C. (2015). Uncovering the influence of social venture creation on commercial venture creation: A population ecology perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(6), 793–807.

Michelon, G., Boesso, G., & Kumar, K. (2013). Examining the link between strategic corporate social responsibility and company performance: An analysis of the best corporate citizens. CSR and Environmental Management, 20(2), 81–94.

Mickiewicz, T., Sauka, A., & Stephan, U. (2014). On the compatibility of benevolence and self-interest: Philanthropy and entrepreneurial orientation. International Small Business Journal, 34(3), 303–328.

Miles, M. P., Verreynne, M. L., & Luke, B. (2014). Social enterprises and the performance advantages of a Vincentian marketing orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(4), 549–556.

Millar, R., & Hall, K. (2013). Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: The opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care. Public Management Review, 15(6), 923–941.

Miras, M. D. M., Carrasco, A., & Escobar, B. (2014). Responsabilidad social corporativa y rendimiento financiero: Un meta-análisis. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting, 43(2), 193–215.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

Moneva, J. M., & Ortas, E. (2010). Corporate environmental and financial performance: A multivariate approach. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 110(2), 193–210.

Moore, G. (2001). Corporate social and financial performance: An investigation in the UK supermarket industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 34(3–4), 299–315.

Morfit, S. (2014). What does corporate social responsibility mean for the technology sector? Standford Social Innovation Review, 1–3.

Nishimura, A. (2007). Conceptual analysis of value-based management and accounting: With reference to Japanese practices. Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Journal, 2(1), 71–88.

Ntim, C. G. (2016). Corporate governance, corporate health accounting, and firm value: The case of HIV/AIDS disclosures in Sub-Saharan Africa. The International Journal of Accounting, 51(2), 155–216.

Oh, W., & Park, S. (2015). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance in Korea. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 51(3), 85–94.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441.

Pava, M. L., & Krausz, J. (1995). Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The paradox of social cost. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(3), 321–357.

Payne, A., Holt, S., & Frow, P. (2000). Integrating employee, customer and shareholder value through an enterprise performance model: An opportunity for financial services. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 18(6), 258–273.

Peloza, J. (2009). The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1518–1541.

Petrie, A., Bulman, J. S., & Osborn, J. F. (2003). Further statistics in dentistry Part 8: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. British Dental Journal, 194(2), 73–78.

Post, L. E. (1991). Research in corporate social performance and policy. Greenwich: JAI Press.

Preston, L. E. (1978). Analyzing corporate social performance—Methods and results. Journal of Contemporary Business, 7(1), 135–150.

Preston, L. E., & O’bannon, D. P. (1997). The corporate social-financial performance relationship. Business and Society, 36(4), 419–429.

Quintão, C. (2007). Empresas de inserción y empresas sociales en Europa. CIRIEC-España, revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa, 59, 33–59.

Rahim, H. L., Mohtar, S., & Ramli, A. (2015). The effect of social entrepreneurial behaviour towards organizational performance: A study on Bumiputera entrepreneurs in Malaysia. International Academic Research Journal of Business and Technology, 1(2), 117–125.

Ramayah, T., Lee, J. W. C., & In, J. B. C. (2011). Network collaboration and performance in the tourism sector. Service Business, 5(4), 411–428.

Reimann, B. C. (1975). Organizational effectiveness and management’s public values: A canonical analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 18(2), 224–241.

Rhodes, J., Lok, P., Yu-Yuan, R., & Fang, S. C. (2008). An integrative model of organizational learning and social capital on effective knowledge transfer and perceived organizational performance. Journal of Workplace Learning, 20(4), 245–258.

Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2002). Meta-analysis. Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology. New York: Wiley.

Rotheroe, N., & Richards, A. (2007). Social return on investment and social enterprise: Transparent accountability for sustainable development. Social Enterprise Journal, 3(1), 31–48.

Sacchetti, S., Tortia, E., & López-Arceiz, F. J. (2016). Human resource management practices and organizational performance. The mediator role of immaterial satisfaction in Italian social cooperatives (Vol. 2, pp. 1–30). Spain: WP Zaragoza University.

Saeidi, S. P., Sofian, S., Saeidi, P., Saeidi, S. P., & Saaeidi, S. A. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 341–350.

Sahin, K., Basfirinci, C. S., & Ozsalih, A. (2011). The impact of board composition on corporate financial and social responsibility performance: Evidence from public-listed companies in Turkey. African Journal of Business Management, 5(7), 2959–2978.

Sanchis, J. R., Campos, V., & Mohedano, A. (2013). Management in social enterprises: The influence of the use of strategic tools in business performance. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9(4), 541–555.

Santos, J. B., & Brito, L. A. L. (2012). Toward a subjective measurement model for firm performance. BAR-Brazilian Administration Review, 9(SPE), 95–117.

Sanzo, M. J., Álvarez, L. I., Rey, M., & García, N. (2015). Business–nonprofit partnerships: A new form of collaboration in a corporate responsibility and social innovation context. Service Business, 9(4), 611–636.

Sargeant, A. (1999). Marketing management for nonprofit organizations. Oxford: University Press Oxford.

Scarlata, M., Zacharakis, A., & Walske, J. (2016). The effect of founder experience on the performance of philanthropic venture capital firms. International Small Business Journal, 34(5), 618–636.

Schaltegger, S., & Synnestvedt, T. (2002). The link between ‘green’ and economic success: Environmental management as the crucial trigger between environmental and economic performance. Journal of Environmental Management, 65(4), 339–346.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (1977). Development of a general solution to the problem of validity generalization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(5), 529.

Shiva, M. M., & Suar, D. (2012). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, organizational effectiveness, and programme outcomes in non-governmental organizations. Voluntas, 23(3), 684–710.

Siciliano, J. I. (1996). The relationship between formal planning and performance in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 7(4), 387–403.

Simpson, W. G., & Kohers, T. (2002). The link between corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the banking industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 35(2), 97–109.

Singh, P. J., Sethuraman, K., & Lam, J. Y. (2017). Impact of corporate social responsibility dimensions on firm value: Some evidence from Hong Kong and China. Sustainability, 9(9), 1532.

Škare, M., & Golja, T. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance—Is there a link? Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1, 215–242.

Soana, M. G. (2011). The relationship between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance in the banking sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(1), 133–148.

Starik, M. (1995). Research on organizations and the natural environment: Some paths we have traveled, the “field” ahead. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 1, 1–41.

Stevens, R., Moray, N., & Bruneel, J. (2014a). The social and economic mission of social enterprises: Dimensions, measurement, validation, and relation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1051–1082.

Stevens, R., Moray, N., Bruneel, J., & Clarysse, B. (2014b). Attention allocation to multiple goals: The case of for-profit social enterprises. Strategic Management Journal, 36(7), 1006–1016.

Suárez, D. F., & Hwang, H. (2013). Resource constraints or cultural conformity? Nonprofit relationships with businesses. Voluntas, 24(3), 581–605.

Tan, W. L., & Yoo, S. J. (2015). Social entrepreneurship intentions of nonprofit organizations. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 103–125.

Tang, Z., Hull, C. E., & Rothenberg, S. (2012). How corporate social responsibility engagement strategy moderates the CSR–financial performance relationship. Journal of Management Studies, 49(7), 1274–1303.

Testi, E., & Bellucci, M. (2011). Measuring an organisation’s social and economic performance for public tenders. In ECPR Conference, Rejkiavik.

Valenzuela, L., Jara-Bertin, M., & Villegas, F. (2015). Social responsability practices, corporate reputation and financial performance. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 55(3), 329–344.

Van de Velde, E., Vermeir, W., & Corten, F. (2005). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 5(3), 129–138.

Van der Laan, G., Van Ees, H., & Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2008). Corporate social and financial performance: An extended stakeholder theory, and empirical test with accounting measures. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(3), 299–310.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 303–319.

Wang, H., & Choi, J. (2013). A new look at the corporate social–financial performance relationship the moderating roles of temporal and interdomain consistency in corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 39(2), 416–441.

Wang, Q., Dou, J., & Jia, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Business and Society, 55(8), 1083–1121.

Weisbrod, B. A. (2009). The nonprofit economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 691–718.

Wood, D. J., & Jones, R. E. (1995). Stakeholder mismatching: A theoretical problem in empirical research on corporate social performance. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 3(3), 229–267.

Wu, M. (2006). Corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and firm size: A meta-analysis. Journal of American Academy of Business, 8(1), 163–171.

Wu, M. W., & Shen, C. H. (2013). Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(9), 3529–3547.

Xiong, B., Lu, W., Skitmore, M., Chau, K. W., & Ye, M. (2016). Virtuous nexus between corporate social performance and financial performance: A study of construction enterprises in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, 223–233.

Yang, C. L., Huang, R. H., & Lee, Y. C. (2014). Building a performance assessment model for social enterprises-views on social value creation. Science Journal of Business and Management, 2(1), 1–9.

Yang, F. J., Lin, C. W., & Chang, Y. N. (2010). The linkage between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance. African Journal of Business Management, 4(4), 406–413.

Yang, Z., Sun, J., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2016). Peas and carrots just because they are green? Operational fit between green supply chain management and green information system. Information Systems Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-016-9698-y.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (ECO2016-74920-C2-1-R//ECO2013-48496-C4-3-R), the Regional Government of Aragon/Feder (S64/S17) and Ibercaja-CAI foundation (Programa Estancias de Investigación).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Francisco J. López-Arceiz declares that he has no conflict of interest. Ana J. Bellostas and Pilar Rivera declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López-Arceiz, F.J., Bellostas, A.J. & Rivera, P. Twenty Years of Research on the Relationship Between Economic and Social Performance: A Meta-analysis Approach. Soc Indic Res 140, 453–484 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1791-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1791-1