Abstract

As a part of the international debate on Beyond the GDP, this paper describes the temporal trend of the multidimensional well-being of the Italians from 1861 to 2011. Building on the CNEL and ISTAT’s Equitable and Sustainable Well-being (Benessere Equo e Sostenibile, BES) project, the paper selects 41 indicators that are grouped into eight dimensions characterizing the most important aspects of everyday life: health, education, work, economic well-being, political participation, security, environment and research and development. In order to synthesize the information provided by this large set of indicators, a composite index for each dimension is tracked over the time span of 150 years. The main contributions of this paper consist in providing an analysis of the Italian BES over such a long period. As a result, the eight domains exhibit temporal tendencies that are different from the one of economic well-being. In particular, health, education, work and political participation show a pattern increasing over time (analogously to economic well-being), although at different growth rates, while an overall declining path emerges for the domains of security, environment and research and development. Moreover, we identify four main periods of the Italian history (before WWI, the Fascist period, the years from 1950 to 1990 and the most recent period) each characterized by different relations among the well-being domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The economic performance of a country is usually measured through the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In the last decades this indicator has been used also as a metric for the standard of living of people. However, a high level of GDP per capita in a country does not automatically imply that people living there are better off compared with those living in a country with lower GDP per capita. Moreover, per capita income increase is not associated with the growth of happiness (Easterlin 1974) or well-being (Stiglitz et al. 2009; Helliwell et al. 2015).

Measuring countries’ development using GDP ignores the effects of economic growth on the environment and, in particular, it does not take into account the costs that we encounter when trying to restore ecosystems destroyed by economic production. These costs are related to services such as regulation of climate and atmospheric gases, decomposition and absorption of waste, flood control, soil formation, pollination, which are invaluable. No accountability of these services—which lack a market price, are non-negotiable and not calculated in the GDP—creates a net loss for present and future generations. Also, if we focus only on the GDP, we ignore the loss of biodiversity, deforestation and their consequent effects on the soil (erosion, geomorphic instability, desertification, salinization, etc.), on the atmosphere (climate regulation at different scales) and on human communities (mass migration due to desertification). Actually, we see that the exponential growth of population and consumption is leading towards an ecological collapse causing rapid mass extinctions.

Moreover, GDP ignores the distributional issues and the contribution of non-market goods and services such as health, education, security and governance. Attention to other aspects of well-being is, therefore, crucial.

Particularly after the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi Commission’s report (Stiglitz et al. 2009), it has been widely recognized that the GDP is an inadequate measure of well-being and, starting from the last decade of the XX century, interest in well-being measures that could overcome the limitations of the GDP has grown. Along these lines, in this paper we measure the well-being in Italy from its unification (1861) to recent years (2011).

Well-being analysis can be carried out either subjectively or objectively. The subjective approach is based on the individuals’ self-assessed life satisfaction (see, among others, Diener and Suh 1997). However, interpersonal comparisons and external events may affect responses. Subjective indicators are not limited to the assessment of overall satisfaction, they also refer to satisfaction with specific aspects of life, such as health, work, social connections, personal security, aspirations and expectations about the future (see, in particular, OECD 2013; Clark 2016; NEF 2013). On the other hand, objective well-being indicators focus on the specific and distinct aspects of the quality of life of individuals that can be objectively measured. They are related to different dimensions: political (political stability and the degree of freedom of a country, the level of crime and corruption), economic (work, level and intensity of its economic growth), environmental (level of environmental pollution) and social (education, health, life expectancy, safety and social problems, life balance). Both subjective and objective aspects of well-being are important, as strongly suggested by Stiglitz et al. (2009), and many of the currently existing indicators of well-being are a combination of the two.Footnote 1

However, going beyond GDP does not mean only engaging in the construction of a significant synthetic indicator, but also going beyond the logic of the market as a value in itself. The measurement of well-being is not a purely technical problem, but rather it reflects the values and preferences of a society and its citizens. So, it would make little sense to compare the well-being of a country using a single indicator. For this reason, it is necessary to move from the unidimensional point of view embedded in the GDP to a multidimensional one. That is, we need a set (or dashboard) of indicators because well-being is a multidimensional phenomenon.

The literature typically distinguishes between two different approaches for measuring multidimensional well-being. On the one hand, well-being can be evaluated through a dashboard of indicators. This approach has the advantages of providing a detailed picture of the situation of a country, as well as of avoiding any loss of information. However, due to the high number of indicators, it does not allow a parsimonious representation of the well-being in a society nor an easy identification of the key macroeconomic changes. Since Stiglitz et al. (2009), there has been an increasing interest in dashboards of indicators, and one of the most important attempts is the Better Life Index proposed by OECD.

On the other hand, well-being can be monitored using a composite index that aggregates all well-being indicators into a single number. Composite indicators are one way to circumvent the problem raised by the extreme richness of dashboards and to synthesize their abundant and relevant information. In fact, the use of a composite index offers the main advantage of summarizing a complex picture into a relatively simple one that can be easily understood. Several attempts have been presented in the literature. One of the best known is the Human Development Index (United Nations, HDI) created in 1990, combining income per capita (in PPP terms), life expectancy at birth, adult literacy and education enrolment ratios.Footnote 2 The computation of a multidimensional index requires that single indicators are combined into a synthetic value, and the literature on composite indicators offers a wide variety of aggregation methods. In general, the aggregation procedure involves the choice both of the weights to be assigned to each component and of a synthetic function (OECD 2008).

Several well-being indicators have been proposed in the literature, which can be classified following different taxonomies. The main classification schemes are based on aspects such as the domain of the analysis (social, economic or environmental well-being), the approach (subjective, objective or both), the type of measure (a single indicator, a dashboard of indicators or a composite indicator), the link to GDP (indicators adjusting GDP, replacing GDP or supplementing GDP), the level of the impact (international, national, local) and the purpose of the analysisFootnote 3 (influencing policy-makers or media, academic use or simple data collection). Reviews of the existing literature on well-being indicators, analysis of the relationships among them as well as their classification according to the above-mentioned criteria have been widely proposed (see, among others, Afsa et al. 2008; Bleys 2012; Boarini et al. 2006; Ciommi et al. 2013; Hák et al. 2012).

Following the recommendations of Stiglitz et al. (2009) that encourage the democratic participation of citizens and the use of surveys for measuring citizens’ perceptions, in 2011 the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) launched the OECD’s Better Life Index (hereafter, BLI) initiative that includes the “How’s life?” report, which constitutes one of the first attempts to measure well-being as a dashboard of indicators (OECD 2011). This framework defines and measures well-being according to 11 dimensions: income and wealth, jobs and earnings, housing conditions, health status, work-life balance, education and skills, social connections, civic engagement and governance, environmental quality, personal security, and subjective well-being. The aim is to identify the aspects of life that matter to the people living in 34 countries (Durand 2015). Being a dashboard of indicators, it allows for both monitoring a country’s performance over time and comparing different countries in each of the specific facets of well-being.

Afterwards, several countries launched similar initiatives that have produced country-specific well-being measures. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the Measuring National Well-being programme provided an overview of the objective and subjective well-being of the UK citizens according to four domains: good connections with friends and family, education and training, job satisfaction and economic security, present and future conditions of the environment (Self et al. 2012). The main objective of this UK programme is to complement the more traditional economic measures used to monitoring the UK performance without creating a measure that replaces GDP.

In Italy, the Beyond GDP initiative has given rise to the Equitable and Sustainable Well-Being (BES) project, coordinated by the National Council for Economics and Labor (CNEL) and by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Aim of this project is to complement the GDP with social and environmental indicators that may help policy-makers to identify the main weaknesses of the country and address efficient and incisive policies to improve the well-being of citizens. The BES project is characterized by a direct involvement of the various components of society, with the aim of providing a democratic legitimisation for the indicators chosen to represent the concept of well-being. The BES, first released in 2013, consists of a set of 134 indicators partitioned into 12 dimensions of well-being: health, education and training, work and life balance, economic well-being, social relationship, politics and institutions, safety, subjective well-being, landscape and cultural heritage, environment, research and innovation and quality of services.

Recently, the OECD has extended the Better Life Index project by considering a temporal analysis and looking at the long-term trend of well-being since 1820. The “How was life?” report (van Zanden et al. 2014) provides an overview of these trends for 25 countries, focusing on 10 dimensions of both material and non-material well-being: GDP per capita, real wages, education attainment, life expectancy, height, personal security, political institutions, environmental quality, income inequality and gender inequality. In addition, the indicators have been aggregated into a composite index defined in two alternative ways: (1) as an arithmetic mean of the standardised indicators with equal weight for each dimension and (2) as a latent variable obtained from a factor analysis. Interestingly, the analysis reveals that the trend in real GDP per capita may not be accompanied by similar trends in other dimensions of well-being such as life expectancy, education, personal security or gender inequality.

Inspired by the “How was life?” report, in this paper we focus on Italy by providing an historical analysis of well-being from the year of the Italian unification (1861) to a more recent one (2011), with the aim of answering the following question: how was life in Italy in 1861 and how has it improved over time? To our knowledge, this paper constitutes the first attempt to extend the analysis of the Italian BES over time.

In particular, we collected 41 long time-series of indicators, covering eight aspects of well-being: health, education, work, economic well-being, political participation, security, environment, research and development. There are three considerations on the basis of the selection of these indicators. Firstly, we tried to find indicators similar to those included in the BES project, since the latter are the result of a democratic legitimisation within the debate of the well-being of Italians. Then, we tried to follow the international proposals, in particular the OECD’s How was Life? report. And, lastly, we took into account the availability of the time series.Footnote 4

Moreover, although we believe that well-being is a multidimensional concept and cannot be reduced to a single measure, we also stress the importance of aggregating the information of several well-being indicators into a reduced number of composite indicators, which play a crucial role in policymaking and benchmarking (OECD 2008). Hence, in order to summarize the information collected in the 41 indicators, we constructed a composite index for each of the eight domains of historical well-being of the Italians, following the methodology proposed in Mazziotta and Pareto (2013). The Mazziotta-Pareto Index is based on the assumption of non-substitutability of the indicators, that is, it does not allow for compensation among them.

Analysing the trends of these eight composite indicators over time can provide an interesting picture of Italian history and may reveal scenarios that would remain hidden focusing only on the GDP.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 illustrates the methodology we used. In particular, for each domain, we computed an aggregate synthetic indicator based on a modified version of the Mazziotta and Pareto (2015) methodology. Once a time series for each domain was obtained, we performed a structural change analysis for each domain, by testing for the presence of multiple structural breaks at unknown dates. Section 3 describes the eight well-being dimensions considered and shows trends and structural breaks of the resulting composite indicators. In Sect. 4 we analyse both the correlations between each domain and GDP as well as the relative changes of the series over time. Section 5 concludes. Finally, two appendices complete the paper, the first one collecting a detailed list of the indicators, sources and coverage of each domain, as well as their relationship with well-being, and a second one comparing our 41 indicators with those included in the BES project. Electronic supplementary material is also available, which includes a graphical illustration of the temporal trend of each of the 41 indicators.

2 The Historical BES Approach: The Methodology

Recently there has been a renewed interest in Italian economic history and demographic trends following the 150th anniversary of Italian unification. In particular, Baffigi (2011) has constructed a time series of the national accounts, providing estimates based on demand and supply side at constant and at current prices, while Di Nino et al. (2011) have analysed how the relationship between real exchange rate misalignments and economic growth has changed throughout Italian history. Moreover, Brandolini and Vecchi (2011) and Vecchi (2011) have constructed a time series for several well-being indicators since the Italian unification. Finally, Felice and Vasta (2015) have computed the human development index for Italian regions over the period 1871–2007.

Although our work is in line with the above-mentioned literature, there are several elements of distinction.

Similarly to Brandolini and Vecchi (2011) and Vecchi (2011) in this paper we provide an overview of the long-term trends of the well-being dimensions in Italy. However, while Brandolini and Vecchi (2011) analysed the well-being of Italians by means of a dashboard of indicators related to economic development, distributional issues and the going-beyond-GDP topics,Footnote 5 in our work we build intensively on the BES project. In fact, we focus on indicators that resemble those adopted in the definition of BES (see Table 5 in the online supplementary material) with the aim of providing a picture of BES over the last 150 years. In particular, as already mentioned, we have collected data from several sources obtaining a set of 41 indicators partitioned into eight domains. Thus, we cover dimensions of well-being that the cited authors leaved unexplored, such as political participation, security, environment and research.

Moreover, Brandolini and Vecchi (2011) examined the trend of each indicator individually and aggregated just a few of them into synthetic indices.Footnote 6 We, on the other hand, propose to summarize all the series belonging to the same domain into a synthetic indicator, with the aim of analysing and comparing the trends of such composite indices over time. This allows us to bring out the multidimensionality of well-being by computing eight different composite indicators aimed at capturing different aspects of well-being as expressed by a large number of indicators.

We also diverge from Felice and Vasta (2015), who focused on a limited number of social and economic indicators, namely life expectancy, education and GDP per capita at purchasing power parity, to compute what they defined a “hybrid HDI” from 1871 to 2007. Their index is computed for Italy and for the Italian regions at census data. Thus, the geographical dimension (regional vs. national), the number of series collected (3 vs. 41) and their frequency (census vs. yearly) indicate noticeable differences between Felice and Vasta’s and our paper. However, the most important difference stands in the approach adopted. Brandolini and Vecchi (2011) and Felice and Vasta (2015) were interested in obtaining an overall index of well-being, like the Human Development Index, while our work follows a multidimensional approach, along the lines of the BES project.

Finally, our work differs also from the time series produced by OECD’s “How was life?”. Firstly, the aim of OECD work was to provide “a truly long-run perspective on measures of well-being that complement GDP per capita” (van Zanden et al. 2014, p. 25), whereas we propose a set of composite indicators that may substitute the GDP. In addition, we use a different aggregation method, which is non-compensatory and takes into account the variability of the indicators’ distribution. Also, we aggregate only within domain, while the OECD’s project proposed an overall index of well-being.

Our analysis presents some unavoidable limitations. First of all, we could not include time series for the subjective well-being domain of the BES, since this concept has been introduced very recently in the economic literature. Secondly, even if it were possible to reconstruct the time series of objective well-being indicators, this procedure should be considered a sort of “statistical archaeology”, which combines data that come from different sources or that are computed with different methodologies. We should also stress that, although our aim is to be in line with the BES framework, we encountered relevant data limitations, and, therefore, we have provided proxies for several of the original BES indicators.

A further problem arises when measuring well-being over time, which is related to the change of people’s preferences. Indeed, there are well-being indicators whose meaning has evolved due to cultural changes in the society. For instance, the idea of having time for doing physical exercise after a hard working day has a different meaning for a farm hand living in Crispi’s eraFootnote 7 and for an employee living frenetically in Milan nowadays. Another example, even more complex to deal with, is provided by violence against women, a concept to which the Italian society has attributed different values over time. Indeed, while domestic violence was allowed until the 1960s, changes in people’s perception about the role of women were followed by changes in the legislation. While violence against women is always negative in a society, it was not considered a crime in the past and had no legal definition, so we could not go backward in collecting data. We thus decided to disregard the “Physical violence rate” from our analysis.Footnote 8 Therefore, in order to take these issues into account, we chose to exclude those well-being indicators whose meaning has drastically changed over time and for which no adequate data are available.

We now move to describe first our data collection strategy and then the methodology implemented for constructing composite indices for each domain.

2.1 The Selection of Domains and Indicators

The implementation in a long run perspective of a multidimensional measure of well-being is a compelling task and several considerations need to be addressed to provide accurate indicators.

Firstly, the choice of domains and indicators of well-being needs a careful evaluation in order to address the requirements of the recent literature. We primarily followed ISTAT’s BES project (CNEL and ISTAT 2013), which represents the Italian effort to provide a multidimensional assessment of well-being. However, in case of data limitations, we proxied some of the BES indicators by following the most relevant international approaches to well-being measurement (such as Human Development Index, Better Life Index, Quality of life Indicators Gross National Happiness),Footnote 9 elaborated by outstanding (governmental or non-governmental) organizations, such as OECD, EUROSTAT and so forth.

Secondly, in our attempt to analyse in the long run the trends of the well-being domains on a yearly basis since unification to the present day, we incurred in severe data limitations. For example, historical data are not available for all the original indicators elaborated by our inspiration sources, mainly ISTAT’s BES. In particular, data are available for each census year but rarely available at a yearly basis; hence, they need to be interpolated.

Thirdly, for some domains data are not available over time, since they represent modern concepts. In particular, the absence of any survey in more remote years on individual or self-reported opinions and beliefs did not allow us to recover subjective well-being domains, such as social relations, subjective well-being and quality of services. We also excluded the domain of landscape and cultural heritage, since both concepts are strictly modern and, therefore, no information about them is available in the long run. The same happens for several specific BES indicators, such as “Uncertainty of employment and job satisfaction”, “Share of employed persons who feel satisfied with their work”, or “Physical violence rate”.

Finally, we have chosen those indicators that over time contribute always either positively or negatively to the well-being of Italians. Even if it is doubtless that preferences, social beliefs and needs have changed dramatically since the Italian unification, we selected the well-being domains and their specific indicators that reveal always a positive (or negative) effect on well-being over time. In particular, we defined positive and negative effects on well-being on the basis of a modern perspective on concept of high-quality life. For example, living longer, being more educated, or having more money have been always considered positive aspects for people’s well-being. In particular, not all the original 134 indicators of the Italian BES have a clear historical interpretation.

Summing up, according to the above considerations, for historical Italian well-being we have selected 41 indicators grouped into the following eight domains: health, education, work, economic well-being, political participation, security, environment and research and development.Footnote 10

2.2 A Composite Index for Each Domain

Once we obtained a rich dataset containing the time series of 41 well-being indicators, we aggregated them by domain, with the aim of synthesizing the information of each well-being dimension. The construction of a composite index for each domain allows us to evaluate the Italian multidimensional well-being over time and to compare the temporal trends of its dimensions.

In particular, we decided to follow the aggregation method adopted so far by ISTAT, which refers to the approach described in De Muro et al. (2011) and Mazziotta and Pareto (2013). As observed by Massoli et al. (2014), a suitable aggregation procedure should produce an index that is, at the same time, comparable across space and time, easy to compute and interpret, and built on non-substitutable and non-compensatory indicators. These authors, after comparing six different methodologies for aggregating individual indicators, conclude that the only one that satisfies all the previous requirements is the so-called Adjusted Mazziotta-Pareto Index (hereafter, AMPI) introduced in Mazziotta and Pareto (2013) and re-adapted in Mazziotta and Pareto (2015) in order to allow for a comparison over time rather than across space.Footnote 11 Therefore, here we apply the AMPI methodology to our data. For each domain, let X = {x ij } be a matrix with n rows and m columns representing the distribution of m indicators over a time span n.Footnote 12

Let R = {r ij } denote the matrix of the normalized indicators, obtained as follows

where \(\hbox{max} ({\text{x}}_{\text{j}} )\) and \(\hbox{min} ({\text{x}}_{\text{j}} )\) denote the maximum and the minimum level achieved by the indicator j over time, respectively. The normalization procedure requires the definition of the relationship between each indicator and the corresponding domain. That is, if the jth indicator is in concordance with its domain, we define indicator jth as being “positive”. Otherwise, if an increase in the jth indicator is associated with a decrease in the corresponding domain, we define it as being “negative”. Focusing, for example, on the education domain, the indicator “School enrolment rate” is positively correlated with its domain, while the indicator “Illiterate spouse” is considered as negative, since an increment of this indicator has a negative impact on education. Moreover, all normalized indicators will take values within the interval (70; 130).

The AMPI construction also involves the use of a so-called penalty coefficient that depends on the indicators’ variability (the authors refers to it as “horizontal variability”) and is measured using standard deviation and coefficient of variation. The standard deviation is used to obtain robust indicators that are less influenced by outliers. In particular, let \({\text{M}}_{\text{i}} = \frac{1}{\text{m}}\sum\nolimits_{\text{j}}^{\text{m}} {{\text{r}}_{\text{ij}} }\), \({\text{S}}_{\text{i}} = \sqrt {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{\text{j}}^{\text{m}} \left( {{\text{r}}_{\text{ij}} - {\text{M}}_{\text{i}} } \right)^{2} }}{\text{m}}}\) and \({\text{CV}}_{\text{i}} = \frac{{{\text{S}}_{\text{i}} }}{{{\text{M}}_{\text{i}} }}\). Thus, the composite indicator for each of our domain is obtained as follows:

where the mean of the normalized values, Mi, is adjusted by subtracting a quantity that is the product of the standard deviation and the coefficient of variation.Footnote 13

As a result, for each year we obtain a composite index for each well-being domain.

Then, we tested for the presence of multiple structural breaks at unknown dates in the trend of each composite indicator AMPI i In particular, we performed a structural change analysis for each domain over the years 1861–2011, following the approach proposed by Bai and Perron (1998, 2003) and implemented, among others, by Clementi et al. (2015).

The model considers a standard linear regression model with k breaks:

where \(i = t_{h - 1} + 1, \ldots , t_{h} , \,{\text{for any}}\, h = 1, \ldots , k + 1, {\text{with}} t_{0} = 0 \,{\text{and}}\, t _{k + 1} = n\) and n is the length of the period span. Model (3) affirms that for each time i between two breaks (that is within a sub-period h) the value of composite indicator \(AMPI_{i}\) is equal to the average value of that sub-period \((\beta_{h} )\) plus a stationary error \(\left( {\varepsilon_{i } } \right)\).

Tests on structural changes aim at testing the null hypothesis of no structural changes over the entire time span: \(H_{0} : \beta_{h} = \beta\) for all \(h = 1, \ldots ,k + 1\) against the alternative hypothesis that the beta coefficients vary over time.

Moreover, we determined the optimal number and location of the structural break points, by minimizing the Bayesian information criterion score (see, among others, Clementi et al. 2015; Bai and Perron 1998, 2003).Footnote 14

3 Results from Each Domain

In this section we introduce and discuss each of the eight dimensions of the historical well-being and their respective indicators.Footnote 15

3.1 Health

Health status is fundamental for the quality of life and is a prerequisite of individual well-being (OECD 2011; WHO 2013) since it affects the participation in other relevant spheres of a person’s self-realization (such as employment, civil participation and social interaction); its relevance grows as people get older (CNEL and ISTAT 2013). To depict the trend of the Italian health status since 1861 we focused on measures of life expectancy at birth, distinguishing between males and females, and of infant mortality rate.Footnote 16 In addition, we considered four more indicators related to improvements in health status and well-being: average height of males (military draft), total calories, vegetable protein and alcohol calorie consumption. All these indicators, except for infant mortality and alcohol calories, positively affect the health domain as presented in Table 4 of Appendix.

Several studies reported a positive correlation between human stature, as a main indicator of the biological standard of living, and nutrition and longevity (Fogel 1994; Fogel et al. 1982; Komlos 1985; Steckel and Floud 1997). Accordingly, height is a common proxy for health in historical studies, especially when data over time and/or for developing countries are difficult to collect (van Zanden et al. 2014).

Similarly, the quality of nutrition affects physical well-being and health.Footnote 17 Here we considered total calories, alcohol calories and vegetable proteins for several reasons. Food consumption deeply affects survival probability and the physical ability to overcome illnesses and more in general, increases the individual capacity of facing daily work. Total calories proxy the potential energy available to the Italians (Vecchi 2011); however, not all types of calories are good for human well-being. For example, alcohol negatively affects the capacity to undertake both physical and social tasks. Sources of vegetable proteins (fruits, vegetables and grains) are largely and easily available also in a less developed society; therefore, the quantity consumed of these proteins may indicate how rich a diet is in macronutrients (essential for cellular growth and regeneration, and for an alternative source of energy in case of lack of glucose).

Data on life expectancy at birth, total calories, vegetable proteins and alcohol consumption are supplied by Vecchi (2011), while average height (males 18 years old) and infant mortality are provided by ISTAT—Italian Historical Statistical Repository (hereafter, ISTAT HS).Footnote 18 All indicators, except for infant mortality and height, are available at censuses and thus they have been (linearly) interpolated.Footnote 19 Infant mortality and height are originally recorded on an annual base but height is interpolated for missing years.

Figure 1 shows the trend of the composite index for the health dimension based on the Mazziotta-Pareto aggregation method. The figure reveals that Italian health status has improved constantly since the country’s unification. However, there are some caveats. Apart from World War (WW) years, when slowdowns or declines in the general tendency can be expected,Footnote 20 we observe some periods of stagnation in the growth pattern of the composite health indicator. Specifically, an almost-flat (decreasing) trend emerges in the 1930′s (fascist period), followed by a flat path from WWII till 1960. Nevertheless, it has to be underlined that these phases are, respectively, subsequent and previous to two periods of marked growth.

One of the causes of stagnation during the 1930–1940 decade lies in the deceleration of the decrease of infant mortality. In that period Italy experienced a phase of economic and scientific isolation from the rest of the world, which prevented it from benefiting from scientific progress, such as new drugs (Penicillin and the Sulfonamides) and diagnostics, whose effects spread across Italy only in subsequent years (ISTAT 2014). Similarly, we observe a decrease in the average available calories mainly due to the autarkic economic policy.Footnote 21

The flatness in the health index over the 1950s can be ascribed to the regularization of new sustainable values of infant mortality, and thus life expectancy, after the sudden changes experienced in the war and post war periods. Additionally, these are the years of the “Italian economic miracle” (miracolo economico italiano) which correspond to the transition from an agricultural to an industrial society. Thus, we cannot exclude that related improvement in general family welfare translates into variations in social life style and eating habits such as the steady reduction of vegetable proteins due to a greater consumption of meat (Tirelli 2006).

Of particular interest is the rapid growth of the health composite index in the second half of 1960s. It can be related to increases in available calories as well as to vaccination requirements, and to the institution of the Ministry of Public Health in 1958 and the Mariotti law in 1968, which established that public hospital institutions provide a wide range of care services. These structural reforms placed Italy among the most developed countries in terms of public health institutions which rapidly brought infant mortality and height growth to, respectively, the minimum and maximum values of the observed trend.Footnote 22

A health reform comes after a period of stagnation in the composite health index: in 1978 the “National Health Service” (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale) was introduced aimed at guaranteeing healthcare for all citizens. After the 2000s, the health indicator appears to reduce its growth rate, possibly due to new diseases or to biological human limits that do not allow for a continuous increase at the same speed.

Figure 1 shows, moreover, that the structural break analysis identifies four optimal breaks in the following years: 1882, 1918, 1967 and 1989, which almost track the picture described above.

3.2 Education

Education is one of the important predictors of well-being (OECD 2011). We tracked education attainment by means of seven indicators for both quantity and quality of education: the share of illiterate spouses, distinguishing between male and female, average number of years of education, enrolment rate at elementary school, high school and university and, lastly, degree attainment rate (see Table 4 of Appendix).

The shares of illiterate spouses testify the diffusion of some ability to read and write among the large mass of population, since these indicators track the share of spouses who were unable to subscribe the marriage certificates because of illiteracy. This indicator is extremely meaningful in order to understand the years immediately after unification, when educational development and skill building were little beyond basic literacy and numeracy ability. Later on, when literacy began to reach 100 % of the population, the degree of education attainment and skill achievement differs largely across different levels of school (see also van Zanden et al. 2014). Thus, progress in education in the recent years can be best recorded by the average number of years of education received, which can be considered as a good proxy for the stage of formal education completed.

Moreover, we included data on enrolment at different school levels to collect information on the trend toward education development and on the massive spread of formal education. Finally, we completed our picture with an overview of degree attainment rate, since improving student academic achievement is one of the prominent goals of current development policies. It is, indeed, commonly accepted that a more skilled and educated labor force favours progress of societies and allows citizens to enjoy and benefit from cultural and social activities in terms of individuals’ inner sense of fulfilment and effectiveness (EUROSTAT 2013).

Basic data series are provided by ISTAT HS time series and ISTAT Census with the exceptions of average years of education estimates, which are published in van Zanden et al. (2014) and population, obtained from Baffigi (2011). Data on shares of illiterate spouses are yearly from 1867 to 1965. They have been assumed to be constant from 1861 to 1867 and also after 1965 when spouse illiteracy scored almost 0 %. School and university enrolment rates are yearly data; however, some short interruptions occurred in the time series on school enrolment, which have been linearly interpolated. They have been computed as proportion of school age population for the given level of education as indicated in Table 4 of Appendix. Data on degree attainment rates are yearly starting from 1926, while for previous periods they are estimated by projecting the 1926–1936 graduation rate on the previous years. Finally, average years of education estimates are recorded as 10 years average, and, therefore, they have been interpolated.

All these indicators enter the Adjusted Mazziotta-Pareto Index with a positive sign, with the only exception of spouse illiteracy.

Figure 2 depicts the trend of the education composite index, which is increasing over time since the Italian unification. The structural break analysis identifies optimal breaks in the years 1882, 1904, 1926, 1966 and 1989. Structural breaks are very close to those identified for the health indicator.

It is clear from Fig. 2 that the trend of the education composite index is increasing. Until WWII the education index growth is driven mainly by the reduction of illiteracy. During those years, several reforms were implemented aimed at ensuring participation in education at the elementary school and at increasing compulsory education up to 14 years.Footnote 23 As economic development increases in Italy over time, secondary and higher education becomes more important as proxy of educational performance. Indeed, increase in the education composite index during the post war period can be ascribed primarily to the growing participation in secondary schools and, starting from 1970, in universities. During the 1990s the growth rate of the index sharply accelerates, mainly driven by the tertiary education enrolment, whereas in the 2000s the composite indicator’s trend becomes flatter due to stagnation in the enrolment rate in secondary education and to a contraction in tertiary education.

3.3 Work

Work strongly contributes to the quality of life for several reasons. Of course, as a source of income, it directly promotes welfare. Material advantages apart, working also helps to build a social status and it is a primary occasion for adult individuals to socialize with each other. Having a job that is adequate to one’s education and skills is a universal aspiration and makes a decisive contribution in reinforcing self-realization and satisfaction (CNEL and ISTAT 2014). On the other hand, poor working conditions (such as unsafe activities or space, insecurity about work and pay, discrimination) have a negative impact on peoples’ well-being and also on their physical and/or psychological health (EUROSTAT 2013).

We tried to account for all these aspects by means of several indicators: activity rate, injury rate, permanent injury rate in work accidents, death rate in work accidents, the National Institute for Insurance against Accidents at Work (INAIL) coverage which is the share of workers under public insurance, child labour (separately for male and female), International real wages (as defined in Williamson 1995) and full time equivalent workers over the population.

Data on activity rate come from ISTAT HS time series at censuses and, hence, they have been interpolated. This indicator is the ratio of the total labour force to the population of working age.Footnote 24 An additional quantitative indicator of the work domain is represented by full time equivalent workers, which measures the amount of hours worked to obtain the total amount of production with no distinction between full or part-time contracts, as proportion of population.

Data are provided by Broadberry et al. (2011) and Baffigi (2011), respectively, and are on a yearly basis. As indicators of the quality of work, we employed the accidents-data made available by INAIL. Beyond the total count, we distinguished types of accidents that are permanent or death injuries; data have been computed as percentage of workers.Footnote 25 Finally, data on low skilled workers, comparable also at the international level, have been obtained by updating the real wage available in Williamson (1995).Footnote 26 Computation of the indicator at a yearly base starts in 1883, since no information on accidents before that year is available. Number of accidents and child labour negatively affect the work composite index, while the remaining indicators enter positively. All these indicators, along with source and coverage of basic data series are described in Table 4 of Appendix.

As Fig. 3 shows, the composite indicator for the work domain increases over time, and four structural breaks in the years 1913, 1936, 1957 and 1976 reveal significant changes in the average value of this index.

Moreover, the index presents a larger variability across the years in comparison with previous dimensions of well-being (health and education), while total improvement (in absolute terms) is lower. Indeed, even if security legislation can promote healthier workplaces, accidents happen at random with high fluctuations across years.Footnote 27

In particular, we can notice that before 1912 labour conditions did not improve significantly; however, the indicator is strongly affected by the very low coverage of workers by INAIL. Labour conditions improve largely before WWI, but this development is almost completely lost because of the war. The fascist period did not considerably improve working conditions: a small increase in the index is observed until the beginning of the war but, during the conflict, it reverts.

It is only after WWII that the work domain starts a continuous growth that stops only in the first half of 1980s; afterwards, the composite indicator slowly deteriorates. The increasing path is mainly driven by the disappearance of child labour and by improvements in low skilled salaries.

Starting from the 1990s the flatness in the composite index is mainly driven by a clear decrease in the INAIL coverage rate and in the injury rate together with a slowdown in the growth rate of the full time equivalent workers.

We finally note that, although the indicators considered cover several aspects of the evolution of work conditions over the 150 years of Italian history, it is implicit that some aspects are not captured by the available time series, in particular changes in laws like maternity leave, legal protection against dangerous jobs and job security.

3.4 Economic Well-Being

Economic well-being is undoubtedly a key issue in determining people’s quality of life. It affects the capacity of spending on goods and services and, thus, of ensuring a more stable and pleasant material standard of living. Moreover, greater financial opportunities favour the access to better services of health, education and social relationships (such as leisure, cultural services, entertainment) improving also this strand of intangible resources of citizens’ well-being.

Traditionally, GDP per capita was used to provide a raw measure of the economic well-being of a country. However, individual economic conditions are also affected by the distribution of income across the society. Economic growth that comes at the expense, for example, of higher income inequality does not provide an accurate picture of a country’s prosperity. Since information on income distribution (computed from demand or supply side) is not available over such a long period of time, we based our analysis on available estimates of the Gini index and the share of the population below the absolute poverty line provided by both Vecchi (2011) and I.Stat for several years. We performed linear interpolations for the missing years. In Table 4 of Appendix, we report, for each of the three indicators considered, source and coverage of the respective data and we show that GDP per capita enters the composite index positively, while income inequality and poverty rate contribute negatively.

Figure 4 depicts the composite indicator and the years of structural break. We can divide the period in four main phases. The first period goes from Italian unification to the beginning of the XX century, the so-called period of late take off. It does not reveal a significant increase in Italian well-being, with only a moderate jump in the first decade of the reign, mainly due to the on-going process of unification.Footnote 28

The second period starts at the beginning of the XX century and continues until the end of fascism (about year 1945). In that period, we observe a slow increase in economic well-being of the population mainly due to a reduction of the share of the population below the absolute poverty line. War and fascism frustrate any improvement in population conditions. This corroborates the idea that behind the fascist propaganda of the so-called battaglia del grano there was no policy target to improve the population’s economic conditions but, instead, a gift to landowners who were the real support of the fascist regime.

It is only after WWII that the country begins to grow at a rate that allows redistribution to the poorer population. The almost continuous growth until 1990s is due to a fast growth in per capita GDP accompanied by a strong reduction in absolute poverty rate. This corroborates the idea that pursuing economic growth is a fundamental requirement for redistribution, even if this is not enough. Since the 1990s the economic well-being composite indicator does not increase, despite at least 10 years of growth in per capita GDP. Indeed, GDP growth is contrasted by an increase in income inequality. Finally, in the last decade the stagnation (before) and the crisis (after) take Italian economic well-being back to the levels of the 1980s.

Finally, we note that the values of the economic well-being composite index seem to confirm Giorgio Fuà’s intuition according to which the Italian economy started growing only around the years 1896–1897, and not since its unification.Footnote 29

Optimal breaks occur in years 1908, 1955 and 1977. It is not surprising, recalling the economic history of Italy. The first period is almost in the middle of the Giolitti era, recalling the name of the leading politician at that time, a period of progress in Italian economic and social growth. However, it was accompanied by a depletion of the Mezzogiorno (South of Italy) that resulted in a massive flow of migration. The second break characterizes the start of the “Italian economic miracle” and, finally, 1977 corresponds to the year in which violence erupted in Italian politics.Footnote 30

3.5 Political Participation

Political institutions that ensure democracy and favour political participation as instruments to express the citizen’s voice also allow individuals to influence government policies. Regardless of the actual outcomes of the political processes, participation in the decision-making process relative to issues that affect peoples’ lives is fundamental to quality of life (Dreze and Sen 2002). According to theories of “procedural utility”, political participation may have an intrinsic value to individual well-being, since people receive satisfaction not only from the final outcome, but also from the way in which those decisions are made (Frey et al. 2004), thus enforcing autonomy, connection, competence, and self-realization.

To build a composite index for political participation we adopted the following elementary indicators: population allowed to vote, voter turnout and vote distance between first and second political party (Table 4 of Appendix). All indicators have been computed from data on general political elections in Italy as elaborated by Corbetta and Piretti (2009) for the period 1861–1934; from 1946 up to 2011 we refer to the Italian Ministry of the Interior. They depict the degree of political participation (population allowed to vote and voter turnout) and political competition in Italy (vote distance between first and second party). Opposition in a democracy testifies the capacity to express a different political view; however, when this vote distance is high, the main opposition party is not largely and effectively representative so that political competition is hampered. Therefore, we assume that this indicator affects well-being negatively, while all the other indicators enter the Mazziotta-Pareto index. Finally, given that elections are held occasionally, we construct a punctual index only for the years when Italians voted for a general election.Footnote 31 As a consequence, optimal structural breaks cannot be computed.

The evolution over time of the spotty political participation composite index, reported in Fig. 5, recalls political Italian history, which can be divided into three main periods. The first period embraces Italian unification, from 1861, till 1913. Parliament is elected by a very small percentage of the population, roughly only males older than 25 years, literate (they have to able to read and write) or rich enough (voters have to pay a given amount of tax, corresponding to 40 lb until 1881 and afterwards to about 20 lb until 1912). No salary or compensation is received for being a member of the national parliament; therefore, only the richest, and usually of noble birth, could candidate and eventually be elected. In 1913 the right to vote was extended to almost all adult males.Footnote 32 However, the index does not improve significantly because of the effects of war and of fascist totalitarianism that inhibited citizens’ political freedom. On the contrary, after the fascist coup in 1922, the political participation composite index inverts to pre WWI values. National constitution comes only after the liberation from Nazi-fascism and the referendum that determines the end of the Reign, which is in 1948. From 1945, also women are allowed to vote.

In 1975 the population allowed to vote is further widened by reducing the voting age for members of the Chamber of Deputies to 18 years.Footnote 33 For the whole period from the end of WWII to the end of 1980s we observe an increase in the political indicator, mainly because of the growing participation of citizens. Actually, until the end of 1980s in Italy there is a series of indirect punishments for abstention (for example, the ban to participate in concorso pubblico, a competitive state exam used to recruit employees for the public sector), which raises electoral participation to very high levels, with peaks over 85 %.Footnote 34 Afterwards, we observe a decreasing trend of the political participation composite index until recent years, which mirrors a growing abstention of voters and the public’s disaffection with politics.

3.6 Security

The absence of threats to people’s security is essential for their well-being. The feeling of safety can be affected by several types of threatening events, such as property crimes, loss of life, economic damage or loss, physical harm and psychological trauma (OECD 2011). In a way, it is a source of pressure which influences people’s possibility to live freely in a community and to enjoy their own property peacefully, due to a perception of threat and the resulting feeling of insecurity that undermines quality of life (EUROSTAT 2013). To construct the security composite index we included the following indicators: number of crimes per capita, of homicide per capita, of theft per capita, of robberies per capita, of scams and frauds per capita, and of violence resistance and offence to public servant per capita. Data source on type of crimes and offences is ISTAT HS while population is from Baffigi (2011) (Table 4 of Appendix).Footnote 35 All indicators enter the Mazziotta-Pareto methodology with a negative sign.

Figure 6 clearly shows the up and down pattern of the composite index, at least until 1950s; afterwards, a declining path seems to emerge, followed by a wavering pattern over the very recent years. Given this historical trend of worsening security, we may wonder whether we are less safe today than our ancestors. To give an interpretation of the index pattern, it is helpful to examine the modification in crime legislation in Italy over time. Indeed, since the index is affected by the number of reported crimes, the introduction of new typologies of illegalities across years have dramatically changed our basic statistics.Footnote 36

Apart from the war periods, we can identify two main falls and a peak in the index tendency. The peak corresponds, not surprisingly, to the fascist dictatorship period; indeed, under such state of police, the rule of law is strongly detuned and it strongly increases the disincentive to enter in contact with law. Moreover, in this period the so-called “blackshirts” (camice nere) are allowed to perpetrate all kinds of violence without any risk of prosecution.Footnote 37 The two falls occur in 1970s and 1990s and they capture different changes in legislation and in social heritage. During 1970s, we witness a dramatic social conflict that culminates in the “years of lead” (anni di piombo, a period of socio-political turmoil in Italy), in the season of terrorism, and in a cultural revolution based on the feminist movement, which completely changes the role and rights of women in Italy. Before that period, in Italy violence against women was tolerated as natural, although not allowed by law. The feminist movement had the great virtue of shedding light on a phenomenon murmured across the country and of giving women the consciousness of the discrimination they had been victims of over time. As an example, the so called “honour killing” (delitto d’onore, the right to kill an unfaithful bride and her lover) was fully abolished only in 1981. Consequently, we observe that the introduction of new legal definitions of crimes and the new awareness of society dramatically increases the number of crimes reported.

Therefore, were Italians less safe after the 1970s? If we do not consider terrorism, the answer is both yes and no. No, in terms of the amount of violence across the country, since presumably women were abused even before definition of the crime was legally instituted. Yes, in terms of perception of the crime, since violence that was considered as normal 10 years before became unacceptable 10 years later.

Similarly, the sharp fall of the composite index series in the 1990s is mainly due to a cultural, technological and demographic change in the country. From a cultural point of view, “clean hands” (mani pulite, the judicial operation which brought to trial politicians and industrialists for corruption scandals) and the reaction to widespread political and social corruption change the penal code and propose a new series of crimes. The computer era introduces new types of offence (for example, software piracy) but also provides justice with new instruments to detect crimes, particularly financial frauds. Finally, yet importantly, Italy becomes a country of immigration and, with the Bossi-Fini law and the introduction of the crime of illegality, the number of crimes dramatically increases. Again, are we less safe than our grandparents? Yes, in terms of the perception that we have of society, related to social insecurities and fear of crime.

It is not surprising that the structural break analysis identifies 4 years of break, corresponding to 1889, 1929, 1971 and 1990, which are also related to the three peculiar periods of fascism, anni di piombo and mani pulite, already mentioned.

3.7 Environment

Quality of the environment is a dimension of the quality of life that is becoming increasingly important in recent times. It has implications for the short- and long-term perspective in sustainable development with regard to both preservation of environmental and natural resources and safeguarding the beauty of landscape (OECD 2011; CNEL and ISTAT 2013).

To analyse this domain of well-being we adopted the following indicators: species abundance, SO2 (sulphur dioxide) emissions and the gross investment in housing constructionFootnote 38 (as listed in Table 4 of Appendix).

Species abundance measures the degree of biodiversity, while SO2 emissions and investment in housing construction monitor natural resource (air and soil) deterioration. More specifically, the latter depicts the pattern of soil consumption and urban sprawl growth as an effect of building construction; a yearly data provided by Baffigi (2011), while species abundance and SO2 emissions are reported by van Zanden et al. (2014). SO2 emissions and investment in housing construction enter negatively the Adjusted Mazziotta-Pareto Index, while species abundance contributes positively (Fig. 7).

The environment composite index shows a clear worsening until post WWI, as the pre-war industrial development consolidates in Italy, with a mild recovery in the years of the “Italian economic miracle”; the period 1920–1930 is characterized also by the drainage of a large portion of Italian territory. The overall decline continues until the end of the XX century, followed by a weak change in the trend due to the actual financial crisis. The latter determined a marked slowdown in building and industrial activity, which is mirrored by a slight growth in the index pattern. The short periods of upturn or sluggish decline over the last century testify an increasing awareness of public opinion toward environmental issues. In addition, several attempts can be listed aimed at protecting the environment and the territory by means of legislative action. Indeed, there were several laws to guarantee Park and protected areas, starting from the framework law on protected areas of 1991,Footnote 39 some resolutions to meet the commitments signed under the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in the early 2000sFootnote 40 and, finally, framework laws to prevent forest fire of 2000.Footnote 41

The dynamics illustrated above are almost replicated by the reference dates identified by the structural breaks analysis: 1888, 1912, 1941, 1966, 1989, which are strictly correlated with important aspects of Italian development over the years. A slow economic and industrial development is accompanied by a declining trend in the environment index until the 1930s. The first structural break year reflects the strengthening of protectionism as high duties on several agricultural and industrial products were introduced. 1911 corresponds to the year of resumption of colonial policy, while 1941 identifies the period of WWII. Starting from 1966 we witness the decline of the miracolo economico italiano. Finally, the year 1989 marks the beginning of an economic stagnation in Italy and subsequent economic crises.

3.8 Research and Development (R&D)

The final domain in the analysis of well-being refers to research and development activity. It impacts social progress and thus is the base of a sustainable and durable development of well-being. Indeed, the application of knowledge contributes to the improvement in a wide range of dimensions that largely affect human well-being (health, work conditions, environment, social connection).

Given the lack of data, we were able to record the historical pattern of this domain only starting from 1970. The available indictors are the share of Italian patents over the total United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) patents, the ratio of R&D investment on GDP and the share of engineers on total graduate students. The former tracks the inventive and creative performance of Italians across the years in the very competitive and international patent market of the USA; data are available from USPTO. R&D investment on GDP is an indicator of the R&D effort made by an economy relative to its overall size. Finally, the share of engineers on total graduate students can be considered as a proxy of the domestic innovative capacity in terms of technical human capital.Footnote 42 The source of the two latter indicators is ISTAT HS historical data (see Table 4 of Appendix). All these indicators enter the AMPI index with a positive sign.

Compared to the previous domains, the R&D composite index has been tracked for a much shorter period of time. Figure 8 reveals very volatile behaviour of the overall time series, identifying three structural breaks (1978, 1984 and 1990). The upward peak of the series is achieved in the year 1990 as a consequence of the highest value in the ratio of R&D investment on GDP. On the contrary, in 1995 the index shows a relevant fall, reaching levels similar to those in the 1980s, mainly driven by the reduction in the ratio of R&D investment on GDP. After some years of unstable recovery with continuous ups and downs, the index turns back to poor performance from 2005 to 2009. This overall result summarizes an uncontrollable decline of the Italian innovative capacity, measured by patenting, alongside a non-growing trend in R&D on GDP.

4 A Correlation Analysis Between GDP and the BES Domains

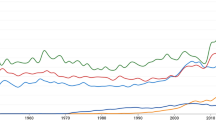

Not surprisingly, the domains previously illustrated exhibit different patterns compared to GDP over the entire period 1861–2011.

The first row in Table 1 illustrates the correlation coefficients between GDP and each of the well-being domains over the entire time span considered. A marked positive correlation emerges with economic well-being, health, education, work, political participation and R&D domains. On the contrary, security and environment are, respectively, negatively and strongly negatively correlated with GDP.

The picture above changes dramatically if we divide the overall period of 150 years into the following sub-periods: pre-war (1861–1913), inter-wars (1921–1938), between the end of WWII and 1990 (1950–1990), and the Second Republic (1990–2011).

The correlation values referring to the sub-period 1861–1913 are similar, although much weaker, with the only exception of the work domain, whose correlation with GDP becomes not significant.

In the years of Fascism (from 1921 to 1938) all the correlations become particularly weak, with the only exception of the political participation domain, which reveals a strong negative trend with GDP.

The post-war period (1950–1990), on the contrary, is characterized by very strong correlation values: a highly positive relation occurs for economic well-being, health, education, work, political participation and R&D, whereas security and environment present strong negative dependence. This may reveal that the rapid economic boom after WWII had as a negative consequence a deep deterioration in environmental well-being.

Finally, in the period of the Second Republic (1990–2011) we observe another relevant change: no series express high positive correlation—only health and education display positive correlation—while political participation and environment are strongly negatively correlated. This may be a signal of the fact that growth in economic well-being in that last period, not only of the environment but also of social well-being, declines.

Interestingly, economic well-being and education are the only domains that display a high and significant positive association with GDP in all the sub-periods.

In addition to the correlation analysis, we also computed relative changes of the series over each sub-period (Table 2).Footnote 43 Looking at the entire period 1861–2011, the relative changes are very high: economic well-being has increased by 79 % and education by 69 %, while security and environment register negative variations of 20 and 27 %, respectively. Looking at the sub-periods, the table confirms what is illustrated in Table 1, but reveals something interesting referring to the periods 1921–1938 and 1990–2011. In the former decades, Table 2 shows that the levels of all the well-being domains remained constant, with the only exception of the security domain, which increased by 20 %. The latter period also presents significant results: while economic well-being remained unvaried security, environment and R&D registered a reduction in the values of their composite indicators, while education and health domains improved. Moreover, Table 3 shows the average annual growth rate in each domain for the different periods of time; it reveals that, for all the domains except education, the period characterized by the highest annual change was the one between 1950 and 1990.

Finally, from Fig. 9 it can be observed that all series anticipate economic well-being, meaning that early indicators of the crisis were not only quantitative and exogenous. Thus, we can assess Italian growth as environmentally unsustainable.Footnote 44 Indeed, the environment domain grew during the years of the Great Recession, when economic well-being declined; even worse is the trend of security and working conditions. Actually, the strong positive feature of education, although still below the European standard, greatly scales down when considering the pattern of research spending. If it is true that we are moving towards a learning society, the collapse that occurred at the beginning of the 1990s is alarming. Moreover, the fact that the environmental domain is negatively correlated with economic well-being gives warnings about long term sustainability of the actual production processes. It signals how difficult growth will be in the years to come, casting concrete doubts on intergenerational sustainability of the process.

5 Conclusive Remarks

In this paper we attempted to describe the well-being of a country like Italy building on a panel of indicators in addition to those commonly adopted per capita GDP.

In the words of Gianni Toniolo:

In 1861, the new Kingdom of Italy was a poor country, in both absolute and relative terms. Per capita income, more or less equivalent to the current average in Sub-Saharan Africa today, was about half that of the United Kingdom, the dominant economic power and cradle of the industrial revolution. Average life in the New kingdom was about 30 years. A working-class family of four lived on the monthly equivalent of €230, 60 % of which was spent on food. Some 44 % of Italians lived in absolute poverty, deprived of sufficient income to meet their daily needs. Income inequality was extremely high (the Gini coefficient was about 0.5). In the course of 150 years, income per inhabitant in Italy has grown approximately 13-fold. Average life expectancy is now 82 years, one of the longest in the world. The average working-class family of four spends an average of €2100 a month on goods and services and only a quarter of it on food which is far more varied and higher quality than that of their forebears in 1861. Unfortunately absolute poverty has not been eradicated, but it now affects “only” 4–5 % of the population. Despite the increase in inequality of the last 20 years, income is distributed much more equally today than at the time of unification.”Footnote 45

Almost all production growth is concentrated in the period after the Second World War. Looking more closely, however, the country starts growing shortly after Unification, and accelerates after 1896, when the Giolitti era begins. Until the eve of the First World War the GDP grows in an almost regular way, but from 1921 to 1945 actual tsunamis (two world wars and the Great Depression) affect the economy. In 1945, the GDP per capita is back to that of 1890, but the post-war period is spectacular: growth is exponential and the nation takes full advantage of opening to foreign markets and public spending, albeit often unproductive and corrupt, on infrastructures (Brandolini and Vecchi 2011). This trend continues until the first oil shock in 1973, which ended the (golden?) years of development. Afterwards, GDP increases at a slower pace until the interruption in 1992 due to the currency crisis and, finally, the economic stagnation observed during the new millennium. Starting from the 70′s, the decline in GDP growth was accompanied by a separation between economic well-being and other socio-economic indicators. Driven by socio-economic frictions, terrorism, fuel crisis, political instability and a deterioration of social cohesion, Italy entered a negative socio-economic spiral which poses serious doubts about economic development and social stability in the long run.

If we continue to think that simply by making the GDP grow, everyone would automatically benefit, we would be wrong. Even if the economy produced more goods and services and, year after year, most citizens had higher levels of income at the expense of future generations, this would not be a sufficient condition to ensure that our economy is working well. If we examine the average life satisfaction for Italy collected by Veenhoven (2014),Footnote 46 we observe that this index improves till 1991 when it reaches its peak and afterwards declines. Thus, the Italian happiness index reveals a path that reinforces our conclusion about the worsening of Italian well-being in more recent years.

The structure of the economy has changed: from farmers we became blue-collar workers, then white collar workers and now unemployed: part-time and happy in the near future? We are living longer and often healthily, we have fewer children and are better educated, but we live in a polluted environment with an increasing sense of uncertainty.

This process is multi-systemic, but not uniform. Thus, while the number of Italians who go to school increases, life expectancy increases, the number of hours of work, the green areas and the quality of air and water decrease.

If we assume that a panel of indicators is able to report something about the Italian situation, it tells us that around the year 1990 the country seems to have reached a threshold of “sufficiency”, beyond which any further increase in economic well-being does not translate into growth of other indicators (health, security, labor and politics). It can also be noted that around the year 1950, two domains change their relationship with GDP: the environment moves from a positive correlation to a negative one, health from no correlation to positive correlation, and work from negative and null correlation to a positive correlation. Moreover, after the anni di piombo period, the security domain also changes its relation with economic well-being, shifting from being uncorrelated to being negatively correlated.

Here, we do not claim that we were better off in the past, and that after all it was better when it was worse, but we must admit that pursing, as an objective, only GDP growth makes us weird people. Like hamsters running frenetically in the wheel, we work harder to be able to produce more and consume more. Reconsidering the idea of GDP as a measure of our life is accompanied by a search for indicators of well-being that should lead us from living to work and consume towards a “Buen Vivir”. The GDP in fact represents the market which- it is sometimes useful to remember-is only a part of our lives and able to assign a price to all commodities, but not a value to goods.Footnote 47

One often reads that the rise in available income of each human being has profound effects on life expectancy, on decline in infant mortality and on literacy. The same is true also for Italy. Until the end of the fifties, GDP growth corresponds to this substantial increase. Everything ends in 1961, when the possible causal relationship becomes very vague. It is difficult to estimate well-being if we merely relate it to income. Money is basically just a part of life; there are things that cannot be measured or materialized (in a certain sense the GDP considers everything that has a price, but not a value). Product increase is certainly a result of productivity, which brings higher wages and profits, but also a reduction in work hours over the lifetime of an average Italian. We would like to point out that economic evolution has led to the disappearance of child labor (it is estimated that in 1860, in Italy, 80 % of the population of 10–14 year olds were economically active). The Gini index indicates the degree of inequality of income distribution. Compared to the average of other developed countries, Italy is currently less equitable. The Gini index decreases from year 1861 to year 1974, and then more quickly until 1985, when the wage share increases, to rise again to the present value of 0.35.

Per capita GDP is not a reliable measure of well-being. Many indicators, including health and education, have significantly improved compared to the moderate increase in national income. Relying only on GDP per capita, Italy does not seem to have converged towards the older industrialized countries. But looking at other indicators of well-being (life expectancy at birth, mortality in the first 5 years of life, literacy), this convergence has been fully implemented.

Material growth has undoubtedly revolutionized our lives and the use of time, but often at the cost of sustainability: environmental and social in the first place, but also related to the quality of life (in particular, security and work conditions). We tried to “have our cake and eat it too”, often delegating to a market that has proven to be inefficient, producing too much (pollution) and too little (research), thus, compromising the future of the younger generations. Only a multidimensional approach, like the one adopted here, allows to recover and evaluate this fundamental perspective.

Further research will be twofold. We will first focus on the comparison of different aggregation techniques. In addition, recognising the importance of measuring well-being at a local level, we will try to reconstruct the temporal evolution of regional well-being in Italy.

Notes

See OECD (2008) for more details on composite indicators.

Also denoted as the “ladder of research utilization” by Knott and Wildavsky (1980).

The complete list of the indicators is available in Table 3.

The indicators considered by Brandolini and Vecchi (2011) are GDP per capita and per equivalent person, child work and manual workers in industry including construction, Gini index and Atkinson index of inequality, male and female life expectancy at birth, the difference between male and female life expectancy at birth, infant mortality, the male height, gross enrolment rate for primary education and literacy rates.

For examples, Human Development Index and distributionally-adjusted GDP measures.

Francesco Crispi was an Italian patriot and statesman and governed as Prime Minister for 6 years, from 1887 until 1891 and again from 1893 until 1896.

In the BES project, this variable accounts for the percentage of women aged 16–70 who are victim of physical violence.

For a careful definition of the mentioned indicators refer to Ciommi et al. (2013).

A comparison among BES domains and indicators and our approach is available online as a supplemental material.

Note that, in contrast with the Mazziotta and Pareto definition of the AMPI, we do not have the space dimension since the unit of analysis is Italy measured over time. So, our modification coincides with AMPI removing the spatial dimension. In other words, we have a bi-dimensional matrix instead of the three-dimensional one.

Note that, differently from Mazziotta and Pareto (2015), here we denote the time span with n rather than with t.

The AMPIi described in Eq. (2) is a simplification of the original AMPI index introduced in Mazziotta and Pareto (2015), which attaches a sign to the penalty according to the polarity of the mean Mi. More in detail, if the mean Mi is positive, such that increasing values of Mi correspond to positive variations of the well-being, then the penalty coefficient is subtracted; on the contrary, if the mean Mi is negative, i.e. increasing values of Mi correspond to negative variations of the well-being, then the penalty coefficient is added. In our application, all the domains are positively related with the concept of well-being and, therefore, the penalty coefficient is always subtracted.

For the analysis, we applied the package strucchange implemented by Zeileis et al. (2002) for the statistical software R (http://www.R-project.org).

The graph of each series is available online as a supplemental material.

As in van Zanden et al. (2014), we do not consider morbidity indicators due to the difficulties in tackling indicators, in the long run, that track aspects which compromise health, such as illness and injury.

Here we focus on aspects of malnutrition instead of under-nutrition.

ISTAT is our main source of information. Our data sources are: Serie storiche (henceforth, ISTAT HS), which is an on-line ongoing database of historical Italian data partly published in ISTAT (2011); and I.Stat, which is an ongoing data warehouse since 2002.