Abstract

Changes in the population age structure can have significant effects on fiscal sustainability since they can affect both government revenue and expenditure. In this paper, we project government revenue, expenditure, and fiscal balance in developing Asia up to 2050 using a simple stylized model and the National Transfer Accounts data set. Rapidly aging countries are likely to suffer a tangible deterioration of fiscal sustainability under their current tax and expenditure system. On the other hand, rapid economic growth can improve fiscal health in poorer, relatively young countries with still-growing working-age populations. Overall, our results indicate that Asia’s population aging will adversely affect its fiscal sustainability, pointing to a need for Asian countries to further examine the impact of demographic shifts on their fiscal health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Asia-Pacific has experienced very dramatic changes in its age structure over the last few decades and these changes are certain to continue in the future. During the 1950 s and 1960 s, most Asian countries were young countries, with the notable exception Japan, but since 1970, the share of young people has declined rapidly and the share of those of prime working age has increased. The share of older people has also increased in many countries. This second phase of population aging is most noticeable in the sub-region of East Asia.Footnote 1

Asia is now entering the third phase of the demographic transition, where the old age population increases dramatically. Changes in population age structure matter for public finances for the simple reason that the beneficiaries of public programmes and taxpayers are different. For both developed and developing Asia, the benefit profiles usually show two peaks. The first peak is for children, driven by public spending on education, and the second peak is for the elderly, driven by public pensions and publicly funded health care spending. On the other hand, the tax burden profiles typically show one peak, at the peak of labor income. Thus, the fiscal balance can worsen rapidly if age-related expenditure such as health care for the elderly increases, while the tax base shrinks due to a decline of the working age population. For wealthier countries with well-developed public sectors, the key issue is whether age-related programs can be sustained as their population age.

In contrast, many developing Asian countries will see an improvement in their fiscal health because their working age populations will continue to expand. The danger is that fast-growing countries with favorable demographics will implement generous transfer systems that ultimately prove to be unsustainable. In fact, many lower income countries spend little on public sector programs for reasons that are largely unrelated to demographic conditions. This pattern is especially evident in the Asia-Pacific region, where the roles of the public sector are very different in high- and middle-income countries than in low income countries. As lower-income countries develop, however, a key issue is whether the public sector can expand while their populations age.

The data needed to document the region’s current demographic profile and to project the future course of its population aging is comprehensive and widely available. However, data on the interface between population age structure and the economy is much more rudimentary and underdeveloped. Even less is known about trends in the age patterns of public program benefits. This is a serious gap in the informational base needed to understand how population aging will influence public sector programs and spending needs over the coming decades.

In this paper, we project government revenue, spending, and fiscal balance in developing Asia up to 2050. Lee and Mason (2015) projected public spending for education, health, and social protection spending for the Asia-Pacific,Footnote 2 but there is no study which projects government revenue, spending, and fiscal balance for the region. By using the National Transfer Accounts (NTA) data set, UN population projections, and other data sources for long-term real GDP projections, we estimate future fiscal burdens that result from both economic growth and demographic changes. We also offer a few alternative estimates based on alternative assumptions. For example, as countries anticipate or experience population aging, they are likely to adjust taxes or benefits if they are concerned about excessive growth of the government. This scenario is considered and discussed in the paper as well.

2 Estimation

2.1 Methodology

The methodology closely follows Lee and Mason (2015), which incorporates two main factors, namely (1) changes in population age structure and (2) changes in age-specific transfers, into fiscal projections. While Lee and Mason (2015) projected public spending for education, health, and social protection spending, we project government revenue, spending, and fiscal balance (see Sect. 2.1.2 for issue related with this projection).

2.1.1 Projection Method

Let per capita transfers to persons age x in year t in country z be designated by b(z)τ(x, t). For the purposes of projection we will use a normalized support ratio equal to public transfers per person relative to per capita income, y(t), so that public transfers per person age x in year t in country z is equal to \(b(z)\tilde{\tau }(x,t)y(t)\) where \(\tilde{\tau }(x,t) = {{\tau (x,t)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\tau (x,t)} {y(t)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {y(t)}}\). Thus, given the normalized transfer profile per capita, transfers are assumed to increase at the same rate as per capita income.

The normalized profile shifts upward in a stepwise fashion as per capita income increases. In general, the normalized profile in year t is given by:

where D k [y(t)] is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if per capita income in year t falls in per capita income growth k (otherwise the dummy variable is zero) and \(\tilde{\tau }(x,k)\) is the model profile for income group k. Please refer to the text for the income groups and the model profiles for each group.

Total transfers as a share of per capita GNP is thus computed as:

The model is applied separately to revenue and spending using separate age profiles.

We calculate the changes in the tax burden and spending given the base year age profile of tax and benefits and the projected population age structure:

Equation (3) is the ratio of per capita tax (spending) in year t relative to per capita tax (spending) on the program in the base year necessary to maintain the level of tax and benefits per person at each age.

Several features of this specification should be noted. First, it is important to understand that population size itself has no effect on tax revenue or public spending as a percentage of GDP although it affects the aggregate amount of revenue or spending. Since public expenditure, which benefits everyone, is assumed to increase at the same rate as per capita GDP, it does not affect our results. Non-tax revenue is assumed to increase at the same rate as per capita GDP, so they do not affect our results either. Rather, it is the population age structure that has a direct effect on revenue or spending as a share of GDP. Intuitively, we would assume that tax burdens and benefits are concentrated at particular age groups, as discussed above. Second, growth in per capita income within income groups does not affect transfers as a percentage of GDP, all other things being equal. We assume that countries increase tax and spending as per capita income rises. The larger relative size of the government in richer countries supports this assumption. Third, public transfers are scaled to match the initial level (year 2010 in this paper) of tax revenue, spending, and fiscal balance in each country. Countries with large public sectors are projected to have large public sectors in the future.

2.1.2 Issues

The rationales for using the two factors—(1) changes in population age structure and (2) changes in age-specific transfers due to projected changes in per capita income—are rather obvious. Countries are quite different in terms of their taxation and spending component. First, the age profiles of taxation very much depend on the tax base (i.e. the source of tax is labour, asset income, corporate, or consumption) but the base differs a lot across countries. For example, compared with Japan, the Korea, Rep. of (henceforth, Korea) relies less on income taxes. The financing of social welfare expenditure is also different in the two countries.

Broadly speaking, the tax base consists of direct and indirect taxes. The choice between direct and indirect taxes has long been the subject of debate in academic and political circles. Income taxes can be classified as direct taxes and the same is true for most taxes on assets and wealth. Indirect taxes such as value added tax fall on transactions such as consumption. Mstinez-Vazquez et al. (2009) show that in the last three decades the average ratio of direct to indirect taxes has been rising, especially in developed countries. This is in large part due to the implementation of social security contributions. The importance of income taxes has declined in developing countries, whereas it has remained flat in developed countries. Within indirect taxes, there has been an increase in consumption taxes, especially in developing countries.

There is a growing literature on the impact of the tax mix on economic growth, equity, and tax revenue. One part of this literature compares the effects of direct versus indirect tax choices in the context of the dynamic endogenous growth model. The evidence generally indicates that switching toward consumption taxation and away from income taxation has a significant positive impact on growth and a negative impact on income distribution (e.g. Li and Sarte 2004). Different taxes may also result in different evasion outcomes. Since income taxes are easier to evade than indirect taxes, tax authorities are more likely to rely on indirect taxes when there is widespread tax evasion. Developing countries tend to rely more on indirect taxes, whereas developed countries tend to rely more on direct taxes. A number of empirical studies show that reliance on direct taxes rises with per capita income (Hines and Summers 2009; Estrada et al. 2015). This has significant implications for the tax burden by age, since the age profiles are quite different depending on the incidence of tax on income versus consumption.

Second, there is a large variation across countries in terms of the expenditure mix. For example, about 40 % of central government expenditure is non-age related in the median Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) country, compared with nearly 70 % in a county such as Korea. This is because Korea still devotes a relatively large share of government spending to public investment and economic infrastructure rather than social welfare related spending. Hence, Korea is less likely to be affected by population aging if we hold the profiles constant, compared with other OECD countries.

Third, there is an issue specifically relevant to Japan, which provides the target profiles of our model. Japan’s tax revenue as a percent of GDP decreased from 14 % in 1990 to less than 10 % in 2012. As a result, Japan’s tax burden decreased by 4.2 % points, whereas the average tax burden ratio in OECD changed little during the same period (around 25 %). In fact, Japanese government cut their taxes in 1994, 1998 and 1999, whereas social welfare expenditure rose in large part due to population aging. Furthermore, the compensation of employees has grown little during the same period due to sluggish economy. Thus, the gap between spending and revenue has been expanding, resulting in an accumulation of Japanese government debt. Simulation results in Kim (2015) show that Japan’s fiscal position may not have deteriorated in the absence of tax cuts. The point here is that while Japan’s welfare expenditure has increased, spending on economic infrastructure and others areas has gradually decreased. Japanese-style debt financing will not be possible for most Asian governments.

Our projections do not explain why some governments are bigger than others. In fact, there is no solid consensus on the determinants of government size, even though richer countries typically have larger governments. Public services require a certain critical minimum size, which implies that smaller economies tend to have bigger governments (Alesina and Wacziarg 1998). Openness may be linked to government size in a variety of ways because openness is a source of destabilising external shocks (Rodrik 1996). Certain modes of political representation, in particular, proportional and parliamentarian democratic systems, can also induce bigger government (Persson and Tabellini 2004).

We do not address differences across countries such as the tax base, composition of social expenditure, government size, or reliance on debt financing. In fact, the literature provides little by way of formal modeling of long-term forecasts of how tax revenues or public sector spending will change. Consequently, our projections based on recent revenue and spending trends in higher income Asian countries are a guide to how revenue and spending are likely to change in lower-income Asian countries. In spite of these limitations, it is nevertheless useful to understand the deteriorating fiscal trends in countries like Korea and Japan. For one, understanding Korean and Japanese trends can alert many Asian countries to the unsustainability of their current tax and expenditure systems.

Above all, although the tax base and expenditures are key determinants of the age profile, it is clear that projections of government revenues, tax revenues, expenditures, and debt will also depend on economic growth and population age structure. For example, Korea’s tax base will shrink and expenditures will increase markedly due to population aging and a decline in the potential growth rate. So it is plausible to assume that the impact of population aging will be substantial even if we allow for diverse patterns of tax bases and expenditure across Asian countries. Due to an older population and slower growth, Korea’s public debt to GDP ratio is projected to rise from 35 % in 2015 to over 200 % by 2060 (National Assembly Budget Office 2015).

2.1.3 Literature Review

A numbers of studies indicate that the age structure of the population has a big impact on economic growth (Bloom et al. 2010; Park and Shin 2011; European Commission 2015). Some found that a higher proportion of the elderly reduces productivity and savings, and increases government expenditures (Fougère et al. 2009; Bloom et al. 2010; Sharpe 2011; Walder and Döring 2012). The demographic shift most likely intensifies the old age dependency ratio, implying that a smaller working age group supports a larger elderly group (Navaneetham and Dharmalingam 2012). Many studies uncover a negative correlation between population ageing and economic growth (Narciso 2010; Bloom et al. 2010; Lisenkova et al. 2012; Walder and Döring 2012), which may be due to the weakening of physical ability, tastes and demand. Changes in public expenditure, consumption and saving associated with population are projected to cause significant negative effect on economic growth. Number of studies (e.g., Weil 2006; Sobotka et al. 2010; Börsch-Supan 2013) confirm that population aging is a global phenomenon, although the level and speed of aging differs a lot across countries. The adverse impact of population aging on economic growth has been significant, especially since the global financial crisis (Lee et al. 2011).

Making use of median values for the share of pensioners in the population, Dang et al. (2001) estimated pension benefits, health care spending and other age-related spending of OECD countries over 2000–2050. Their study predicts an increase in age-related spending of around 6 % points of GDP.Footnote 3 Pension reform can, to a certain extent, compensate for the adverse impact of older populations on sustainability of pension systems.

European Commission (2015) estimated aging forecast public expenditure for 2013–2060. The forecasts were made for age-related expenditures such as pensions, health care, long-term care, education and unemployment benefits. The exogenous macroeconomic variables were labor force participation, employment, unemployment rates, labor productivity and the real interest rate. The empirical results suggest that low fertility, longer life expectancy and migration policy will transform the EU’s demographic structure considerably in the coming decades. The overall size of the population is likely to increase by 2060 but will be much older.Footnote 4 The old-age dependency ratio will rise almost twofold over the long-term. In other words, the EU now has four working-age people for every person aged over 65 years but the ratio will drop to about two in the future. The study projects falling labor supply and growing pressures on public expenditures.Footnote 5 The increase in age-related expenditures between 2013 and 2060 are primarily driven by health care and long term care spending.

Using demographic projections from the UN, Clements et al. (2015) make long-term projections on public pension and health care spending for countries around the world between 2015 and 2100. To reduce the fiscal effect of population aging, they suggest policies such as boosting fertility rates. In addition, allowing more migration from younger countries would influence the age structure and create breathing room for helpful reforms. Along with better tax systems and more efficient public expenditures, policies that increase the participation of women and elderly in the labor market can mitigate the effect of population aging. The authors estimate that without further reforms, public spending on age-related programs such as pensions and health care would rise by 9 and 11 % points of GDP in developing countries and developed countries, respectively, between 2015 and 2100. Furthermore, declining populations can reduce economic growth and make it more difficult to reduce public debt as share of GDP. Lee and Mason (2015) estimated government spending on education, health care, and social protection in developing Asia up to 2050. In projecting the potential consequences of demographic change and economic growth, they use United Nations’ population projections and long-range projections for real gross domestic product (GDP) from other sources. They find that the GDP share of public spending on health care and social protection will grow since demographic change and economic growth are mutually reinforcing. GDP share of public spending on education will decrease in Asia and the Pacific due to declining fertility rate. The magnitude of these effects varies depending on the speed and of demographic change and the current level of public expenditure, which differ a lot across economies. According to the study, social spending in the Korea, Rep. of; the China, People’s Rep. of; and Taiwan is projected to more than double as a share of GDP by 2050, while the increase will be more modest in other areas of Asia and the Pacific. Studies comparable with our study have been summarized in “Appendix Table 2”.

In sum, at a broader level, most studies propose quite similar policy tools to sustain economic growth and tackle the effect of demographic change when populations are aging. Policy implications such as promoting immigration, extending the retirement age, improving social planning, and increasing the fertility rate of couples are some frequently suggested policy tools. Yet, there is no one-size-fits-all policy tool kit that can adequately tackle the challenge of aging population in all countries all the time. Most of the literature suggests that although the broad contour of policy options may be similar across countries, the actual policy measures must be country-specific to the extent that the speed and scale of aging, as well as impact of aging, differs from country to country. Other policy-relevant parameters, such as the fiscal space available to a country, will also dictate country-specific responses to aging.

2.2 Data

In this section, we describe the data used in our analysis.

2.2.1 Population and GDP Growth

UN World Population Prospects, 2012 Revision (2013a), prepared by the UN Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, is used for our analysis. All projections are based on the medium fertility scenario. This scenario assumes that fertility will continue to decline in high fertility countries and will recover towards replacement in low fertility countries. Details are available on the UN Population Division website.Footnote 6

Long-term projections of real GDP are inherently difficult to construct. We rely on three sources of data—OECD projections for Japan, India, Indonesia, Korea, China, and Non-OECD countries up to 2060; Asian Development Bank (ADB) projections for ADB member countries up to 2030; and the International Macroeconomic Data Set from the United States (US) Department of Agriculture for 190 countries up to 2030. Since ADB and USDA provide projections only up to 2030, OECD member and non-member projections are used as a benchmark for extended projections up to 2050. Countries have been classified into four groups based on these three data sets. The projection results are influenced by the GDP growth assumptions only when countries graduate to a new income group. Many low-income countries do not exceed US $5000 per capita income throughout the entire projection period, and many others reach a higher income level only near the end of the projection period.

2.2.2 Public Sector Finances

Data on public sector finances are based on National Transfer Accounts (NTA), a new set of economic accounts, which document economic flows to and from ages in a manner consistent with the UN System of National Accounts. Research teams in about 50 countries on six continents are currently collaborating in the construction of NTA. Accounts have been constructed for eleven Asian economies—Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The theoretical foundations of the accounts build on Lee (1994a, 1994b) and some details and preliminary results are reported in Lee et al. (2008) and Mason, Lee et al. (2009). The most recent and comprehensive treatment is Lee and Mason (2011). Methods are fully documented and explained in United Nation Population Division (2013b) and on the NTA website: www.ntaccounts.org.

In NTA, transfer inflows refer to flows received by the beneficiaries of all public programmes, which are used for projections of public spending. Transfer outflows refer to the flows from taxpayers who are funding the programme, which include taxes and other sources of revenue. For example, if the government runs a deficit, transfer outflows are equal to taxes, plus other sources of revenue that make up the difference—grants, net public asset income, and dis‐saving represented by the sale of public debt. In NTA, taxes provide the age pattern of all public transfer outflows, but not the macro controls. Instead, the macro controls are equal to public transfer inflows plus any net transfer of the programme to Rest of World (ROW) entities (Table 1).

Public transfer outflows are assigned to taxpayers based on rules that are similar to those followed in generational accounting. It is constructed in two steps. First, age profiles of taxes and social contributions are constructed. Second, these age profiles are combined with information about how each type of government programme is funded (the “source”) to construct age profiles of public transfer outflows by purpose (Table 2).

Public transfer inflows are public benefits, classified by purpose: education, health, pensions, and other public programs. This classification is consistent with the UN Classification of Functions of Government (COFOG), but simplified to emphasize large inter‐age transfers. These public transfer inflows provide the age pattern of government spending. Distinguishing the purpose of inflows is important for constructing age profiles. Transfer inflows for many public programs are assigned to the age group of the intended beneficiary of the public program in question using techniques described below. The inflows from public collective goods, e.g., national defense or diplomacy, public administration, and public safety programs are assigned equally among all members of the population, i.e., on a per capita basis.

Public spending on social welfare is much lower in low income Asian countries than in high income countries in per capita terms, but also relative to standards of living. As incomes grow in the region, taxes and public spending will become increasingly important. Exactly how countries adjust to higher income is a matter of policy and will be determined by political decisions within each country.

We use age profiles of tax and public spending by age for Asian countries for which NTA profiles are available, as follows. All profiles are per capita flows to persons at each age expressed relative to the average per capita labor income of those aged 30–49. Thus, given a particular profile, per capita flows rise at the same rate as projected per capita labor income for prime age adults. In addition, we assume that as countries become members of higher income groups that they will experience additional changes in their fiscal profiles. Four model profiles, constructed for the varying levels of income shown in Table 1, are used to allow for the effects of income, as shown in Table 3.

The profiles thus obtained for each income group are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The level of spending and revenue rises relative to income as per capita income reaches higher levels.

In Fig. 1, the age patterns of government spending that are particularly visible for the older people due to the dramatic increase in their health expenditure. For low and middle income countries, the increase in spending on health care at older ages is less pronounced than for higher income countries, where health care spending rises very sharply with age.Footnote 7 All projections are scaled and adjusted proportionately to match the actual observed values of government expenditure in 2010 as a percentage of GDP for each country, provided by ADB. This guarantees that our projections depend on county specific growth rate, age structure change, levels of tax revenue versus non-tax revenue, the share of social welfare spending, and the level of debt financing.

Again, Fig. 1 does not include the other public spending, which benefits everyone (i.e. allocated equally to the whole population) such as national defense. Nevertheless, other public spending is assumed to increase the same rate as per capita GDP and we calibrate the aggregate controls for whole countries at their 2010 values. Therefore, using the profiles, excluding the other public spending, which benefit everyone does not affect the results. Likewise, using the tax profile to estimate government revenue, including non-tax revenue will not change our results since we assume that non-tax revenue as a percent of GDP will not change over time.

3 Fiscal Projections

In this section, we present our projections for government expenditures, tax revenues, government revenues, and fiscal balance up to 2050.

Actual values (1995–2010) and projections of government expenditure to 2050 are provided in Table 4. Populations are aging, which should push up the level of social welfare spending. In addition, higher levels of per capita income should push up per capita spending on social welfare. For a few countries (see Table notes), spending by all levels of government are included, but in most cases, the values refer to central government spending only.

3.1 Expenditure

On average, the increase amounts to a 3.3 % rise in the percentage of GDP spent on public expenditure.Footnote 8 The simple average of developing Asian countries increases from 24.4 % of GDP in 2010 to 27.7 %, if we exclude countries with missing data in any particular period. The rise in public expenditure is particularly dramatic in East Asia, with the average share of GDP rising from 16.9 % of GDP in 2010 to 27.5 % of GDP in 2050. In the PRC, the projected rise is from 22.4 to 33.9 % of GDP, a projected increase of 51 %. This sharp increase reflects rapid aging combined with relatively high rates of economic growth. In Korea, it will increase from 19.8 % in 2010 to 32.4 % in 2050, in large part due to population aging. In a number of other countries outside East Asia, public expenditures will also grow quite rapidly.

For a few countries, only a small increase is projected because projected economic growth and projected population aging are limited. Government expenditure in Bangladesh, India, and Philippines are projected to reach 12.6, 16.5 and 16.9 % of GDP, respectively, in 2050. Note that spending in Singapore is quite low in 2050 (16.9 %), but its mandatory provident fund, the Central Provident Fund, is not included in the figures.

High public spending is not limited to Asia’s higher income countries. Several Central and West Asia countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kyrgyz Republic), South Asian countries (Bhutan and Maldives), and Timor-Leste have high levels projected for 2050. These projections may be quite conservative. We only emphasize the kind of benefits which are affected by the age structure. Other public spending may also increase rapidly, but they are not considered here. Other public expenditure can only be assessed with more extensive data with detailed information on the different components of public spending.

3.2 Revenues and Fiscal Balance

Estimates of tax revenue and government revenue as a percentage of GDP for selected economies up to 2050 are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Again, for a few countries (see Table notes) revenue at all levels of government are included, but in most countries, the values refer to central government revenue only. Tax revenues average 15.2 % of GDP (simple average of country values) in Asia. The average figure is projected to increase to 20.2 % of GDP by 2050, ranging between 1.5 and 39.5 % of GDP (Table 7).

The projected increase in revenue is driven by an increase in income level, and in some developing economies by increase in working age population as well. Since we assumed that the share of non-tax revenue as a percent of GDP will not change over time, the percentage change of tax revenue over time is the same as the percentage change of government revenue.

The importance of tax revenue, currently and in the future, varies considerably from country to country. Very large increases are projected for PRC, where tax revenue as a share of GDP soared from 9.9 % in 1995 to 18.2 % in 2010, and it is projected to further increase to 37.3 % until 2050, an increase of 105 % for the next 40 years. But for Korea and Taiwan, tax revenues increase very little since the negative effect of population aging partially offsets the positive effects of growth. High levels of government revenues are not limited to East Asian countries. Several Central and West Asia countries (Armenia, Georgia, and Uzbekistan), South Asian countries (Bhutan and Maldives), and many countries in the Pacific have high level of government revenue. Only Japan (central government) will experience a decline in tax revenue as share of GDP due to its shrinking working age population.

Some countries rely much more on non-tax revenues for government spending. Timor-Leste is an extreme case where the tax revenue accounts for only 1.5 % as percent of GDP in 2010, even though government revenue is 22.0 % of GDP in 2010. This is because foreign aid makes up the lion’s share of the government budget. Another extreme case is Brunei Darussalam, where the difference between tax revenue and government revenue is about 20 % point as a share of GDP in 2005. The non-tax revenue is revenue from petroleum and natural gas sales. Mongolia is another significant outlier. Projections for these countries are not realistic and hence some estimates are dropped from our analysis.

Fiscal balance is the government’s income from tax and other revenues, including the proceeds of assets sold, minus government spending. When the balance is negative, the government has a fiscal deficit. When the balance is positive, the government has a fiscal surplus. The projected fiscal balance is calculated as the difference between the projected increase in tax revenue and projected spending. PRC and Bhutan show the most dramatic improvement in fiscal balance between 2010 and 2050.

However, our projections for revenues as well as fiscal balance should be interpreted with extreme caution. In contrast to our spending projections, our revenue projections are not conservative. In the real world, raising taxes would be more difficult than raising government expenditure. This is especially true for rapidly growing countries, i.e., country group A in our model (Mongolia, PRC, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, India, and Vietnam). As expected, our results predict fiscal improvement for these countries. For example, PRC recorded a fiscal deficit of 1.7 % in 2010, but our projection shows a fiscal surplus of 6 % in 2050. The same is true for Bhutan, which recorded the fiscal surplus of 1 % in 2010. The surplus is projected to increase further to 10 % in 2050, the highest level among Asian countries.

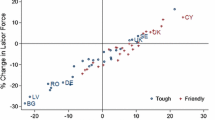

Figures 3 and 4 present the average of the actual and projected government expenditure, government revenue, tax revenue, and fiscal balance as percent of GDP. These are unweighted simple average of developing Asian countries, which is limited to all countries for which we have estimates and projections for 1995–2050. The simple average shows that on average revenues tend to rise faster than expenditures in our model. As a result, the fiscal deficit declines over time.

In fact, as countries anticipate or experience the effects of changes in their population age structure, they are likely to adjust taxes or benefits if they are concerned about the growth of the government. To address this issue, an alternative estimate based on the assumption of status quo is presented in the appendix table. The status quo scenario projects tax revenues as a percent of GDP assuming that all countries maintain the fiscal balance of 2010 until 2050. The “Appendix Tables 13 and 14” shows that the tax revenue as a percentage of GDP for PRC increases to 29.7 % in 2050 instead of 37.3 %, as in the original scenario. The opposite is true for Korea or Taiwan. Tax revenues for Korea are projected to increase to 26.6 % in 2050 (instead of 15.6 %) if fiscal balance is held constant. For Taiwan, tax revenues rise to 22.3 %, instead of 9.9 %.

3.3 Decomposition Results

The projections of tax revenue, public sector spending, and fiscal balance are driven by changes in the level of taxation and spending and changes in age structure. Although the level of taxation and spending have been indexed to per capita income, it would be a mistake to interpret this as a causal relation between income and the level of spending. Instead correlations of income may account for some or all of the changes in the level of spending.

The analysis, presented in Tables 8, 9, 10, is based on a simple decomposition procedure. The value in the first column of numbers, the 2010 value, is the actual share of GDP in 2010. The second column is the projected change in the percent of GDP between 2010 and 2050. The third column reports the effect of changing age structure calculated by holding the level of tax, spending, and fiscal balance at their 2010 levels, using population age structures for 2010 and 2050. The next column reports the difference between the total change and the change due to age structure as the amount due to age specific changes in the level of tax and spending. The interaction between changes in the level of taxes, benefits, fiscal balance, and age structure are reported in the following column. The final three columns in the table report the change due to age structure, age-specific level of spending, and interaction between the two as a percentage of the 2010 value (Tables 8 and 9) or as a percentage of percentage change from 2010 value (Table 10). These values control for the large effect of the initial level of spending and allow us to focus our attention on the importance of age structure and age-specific level of spending.

For government expenditures the effects of changing age structure and changing levels of age specific spending mutually reinforce each other in East Asia (Table 8). The age structure effects are by far the largest in East Asia, and particularly in Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. In those economies, age structure changes will raise government expenditure by 2.5–4.9 % points as a share of GDP by 2050. The effects are large in other countries, but nowhere near this large. The interaction effects are by far the largest in East Asia.

Somewhat surprisingly, the increase is much smaller in other Asian countries which are also aging rapidly, for example Thailand. There are two underlying reasons for this. First, aging in poorer countries has a smaller impact because welfare expenditures often do not rise as rapidly with age as in richer countries. While their welfare spending is projected to reach higher levels between now and 2050, the increase in pensions, health care and other elderly-oriented expenditures will be more limited than in richer countries. The second factor is the shape of the age profile. An increase in the 70+ population has a much bigger impact on expenditure than an increase in the number of 60-year-olds. East Asian DMCs are further along in their aging process and hence relative to Thailand, the very elderly account for a larger share of the increase in the old-age population.

The decomposition analysis for government revenue is presented in Table 9. We do not report the results for tax revenue and government revenue separately since the decomposition results are same. All changes in government revenue are driven by tax revenue, not by non-tax revenue. Non-tax revenues and grants are assumed to increase as a fixed share of GDP in our model.

The share of the working age population is declining in East Asian economies and, hence, the impact of changing population age structure is to reduce tax revenues in this region. The impact is not big enough to offset the increase in tax revenues though. On average, changing age structure could reduce tax revenues by between 6 and 8 % in East-Asia. The same is true for Singapore and Thailand too. On the other hand, most countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia experience increase in tax revenues between 2010 and 2050. The effects in others regions vary a lot, ranging from 1 to 21 %. The interaction effect is quite small.

The effects of changes in the level of taxation are non-negative in every country since the per capita age-specific level of taxation is assumed to rise as countries grow richer. The rising level of age specific tax is large enough to offset the effects of changing age structure in all countries. The age specific tax revenue increase is largest in countries that are expected to grow rapidly, such as PRC and Thailand. This is due the assumptions underlying our projections, which are based on observed data.

Table 10 shows the decomposition of the fiscal balance. The last columns are negative if fiscal balance worsens and positive if it improves. If the contribution due to age specific change in the level is nil for both revenue and expenditure, then all change is due to age structure. For example, most countries in Central and West Asia, and the Pacific will not experience any change due to change in growth. All changes in their fiscal balance will thus be due to change in their age structure. Only demographic effects matter in countries that are very poor, or grow very slowly, and hence do not reach the income threshold that leads to an upward shift in the health profile. At the same time, only demographics matter in very rich economies such as Hong Kong, Singapore, or Japan, for the same underlying reason.

Although some Asian countries are currently in good fiscal shape compared with other regions of the world, such as Europe or Latin America (Roy 2015), there is no guarantee that their fiscal health will last. Korea is an example of a country which is expected to simultaneously face a substantial fiscal deficit, slower economic growth, and population aging. Population aging will significantly harm the fiscal health of all East Asian countries. However, healthy economic growth could offset some of the negative impact of population aging. The PRC, which is assumed to grow rapidly until 2050 in our model, is a case in point. But in Korea and Taiwan, both the age effect and the age-specific level effects will adversely affect the fiscal balance. In contrast, both the age effect and the age-specific level effects are benign and mutually reinforcing in many South Asian countries. The size of the working population is still growing in these countries, while social welfare spending remains limited. High growth rate is the key driver of the region’s fiscal improvement.

4 Conclusions

Although data limitations impede our analysis of the relationship between demographic change and fiscal sustainability in Asia, our findings nevertheless point to some important issues and considerations. The worsening fiscal health of countries like Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, suggests that current tax and expenditure systems cannot guarantee future fiscal sustainability in aging Asian countries. On a more optimistic note, low income countries, which are still enjoying an expansion of the working age population under the second phase of the demographic transition, can help their own fiscal position substantially by growing rapidly. At the same time, it should be noted that population aging is a universal feature of Asian countries. Only the timing and speed of the demographic transition varies and sooner or later they will face a deterioration of their fiscal health in the future, following the footsteps of Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.

Our results for individual countries are based less on what we know about individual countries and more on what we see as broad patterns across the region based on selective data available for countries at different levels of development. Data about the interaction between the population age structure and the economy remain underdeveloped. The age profiles of tax burdens and benefits are available for only a few countries. Little is known about how slow growth and population aging will influence the fiscal environment in the coming decades. This information gap points to an urgent need to improve the quality of data, particularly data on public transfers in Asian countries.

Public programs are an increasingly important source of support for the elderly, especially in richer Asian countries. The key question is how to sustain or reform current old-age support systems in the face of rapid population aging. According to our results, population aging can lead to very substantial increases in public spending and decreases in revenue, even with constant age profiles. Therefore, a key priority everywhere is to improve our understanding of the connection between age, tax burden, and needs for support. Unfortunately, current policies often depend on definitions of working age or old age that are arbitrary and perhaps increasingly out of touch with changing reality.

Notes

See “Appendix Table 11” for population projections of all study countries.

We follow Lee and Mason (2015), which is consistent with the definition by the Asian Development Bank.

They assumed that the change in share of GDP of other government spending and revenues as a constant thus a share of GDP change in age-related spending is fully incorporated in the overall primary balance.

Up to 2050, the EU population is expected to increase from 507 million in 2013 by almost 5 %, when it will touch the highest at 526 million and will thereafter descent slowly to 523 million in 2060.

The total employment rate (for individuals aged 20–64) in the EU is projected to increase from 68.4 % in 2013 to 72.2 % in 2023 and 75 % in 2060 whereas the number of employed would shrink.

Lee and Mason (2015) project government spending for education, health, and social protection respectively.

The calculation excludes who are missing any period of observations.

References

Alesina, A., & Wacziarg, R. (1998). Openness, country size, and government. Journal of Public Economics, 69, 305–321.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Fink, G. (2010). Implications of population ageing for economic growth. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 26, 583–612.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2013). Myths, scientific evidence and economic policy in an aging world. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 1–2, 3–15.

Clements, B. J., Dybczak, K., Gaspar, V., Gupta, S., & Soto, M. (2015). The fiscal consequences of shrinking populations, IMF staff discussion notes 15/21. International Monetary Fund.

Dang, T., Antolín, P., & Oxley, H. (2001). Fiscal implications of ageing: Projections of age-related spending. In OECD economics department working papers, no. 305. OECD Publishing.

Estrada, G., Lee, S.-H., & Park, D. (2015). An overview. In D. Park, S.-H. Lee, & M. Lee (Eds.), Fiscal policy, inequality, and inclusive growth in Asia (pp. 1–25). Oxon, UK, New York NY USA: Routledge.

European Commission (2015). The 2015 ageing report: Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU member states (2013–2060). European Economy 3/2015.

Fougère, M., Harvey, S., Mercenier, J., & Mérette, M. (2009). Population ageing, time allocation and human capital: A general equilibrium analysis for Canada. Journal of Economic Modelling, 26, 30–39.

Hines, J. R., & Summers, L. H. (2009). How globalization affects tax design. NBER working paper series 14664.

Kim, S. T. (2015). Lessons from Japan’s fiscal policy for Korea. In Presented to the EWC-KDI conference on Japanization: Causes and remedies. August 2015.

Lee, R. D. (1994a). Population, age structure, intergenerational transfers, and wealth: a new approach with applications to the US, P Gertler. The family and intergenerational relations. Journal of Human Resources., 29, 1027–1063.

Lee, R. D. (1994b). The formal demography of population aging, transfers, and the economic life cycle. In L. G. Martin & S. H. Preston (Eds.), Demography of aging (pp. 8–49). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Lee, R. D., Lee, S.-H., & Mason A. (2008). Charting the economic lifecycle. In A. Prskawetz, D. E. Bloom, W. Lutz (Eds). Population aging, human capital accumulation, and productivity growth, vol. 33 (pp. 208–237). Population and Development Review.

Lee, R., & Mason, A. (Eds.) (2011). Population aging and the generational economy: A global perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Lee, S.-H., & Mason, A. (2015). Are current tax and spending regimes sustainable in developing Asia? In D. Park, S.-H. Lee, & M. Lee (Eds.), Fiscal policy, inequality, and inclusive growth in Asia (pp. 202–234). Oxon, UK, New York NY USA: Routledge.

Lee, S. H., Mason, A., & Park, D. (2011). Why does population aging matter so much for Asia? Population aging, economic security and economic growth in Asia. ERIA discussion paper series, ERIA-dp-2011-04.

Li, W., & Sarte, P. D. (2004). Progressive taxation and long-run growth. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1705–1716.

Lisenkova, K., Mérette, M., & Wright, R. (2012). Population ageing and the labour market: modelling size and age-specific effects. Economic Modelling, 35, 981–989.

Mason, A., Lee, R., et al. (2009). Population aging and intergenerational transfers: introducing age into national accounts. In D. Wise (Ed.), Developments in the Economics of Aging (pp. 89–126). Chicago: NBER and University of Chicago Press.

Mstinez-Vazquez, J., Vulovic, V., & Liu, Y. (2009). Direct versus indirect taxation: Trends, theory and economic significance. International Studies Program WP 09-11.

Narciso, A. (2010). The impact of population ageing on international capital flows. MPRA paper 26457.

National Assembly Budget Office (2015) White paper. Republic of Korea.

Navaneetham, K., & Dharmalingam, A. (2012). A review of age structural transition and demographic dividend in South Asia: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Population Ageing, 5, 281–298.

Park, D., Shin, K. (2011). Impact of population aging on Asia’s future growth. In: Asian development bank economic working paper series no. 281. October 2011.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2004). Constitutions and economic policy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 75–98.

Rodrik, D. (1996). Why do more open economies have bigger governments? The Journal of Political Economy, 106(5), 997–1032.

Roy, R. (2015). Room at the top: an overview of fiscal space, fiscal policy, and inclusive growth in developing Asia. In D. Park, S.-H. Lee, & M. Lee (Eds.), Fiscal policy, inequality, and inclusive growth in Asia (pp. 26–68). Oxon, UK, New York, NY USA: Routledge.

Sharpe, A. (2011). Is ageing a drag on productivity growth? A review article on ageing, health and productivity: the economics of increased life expectancy. International Productivity Monitor, 21, 82–94.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2010). Economic recession and fertility in the world literature review. In European commission, directorate-general employment. Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities Unit E1–Social and Demographic Analysis.

United Nations Population Division. (2013a). World population prospects: The 2012 revision. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Population Division. (2013b). National transfer accounts manual: Measuring and analyzing the generational economy. New York: United Nations.

Walder, A. B., & Döring, T. (2012). The effect of population ageing on private consumption—a simulation for Austria based on household data up to 2050. Eurasian Economic Review, 2, 63–80.

Weil, D. N. (2006). Population Aging. NBER working paper 12147.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SH., Kim, J. & Park, D. Demographic Change and Fiscal Sustainability in Asia. Soc Indic Res 134, 287–322 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1424-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1424-0