Abstract

This study focuses on the long-term trend in happiness by income level in the United States. General Social Survey data suggest that in the past, rich and poor Americans were not only more equal in terms of income, but also in terms of their subjective wellbeing: the happiness gap between the poor and the rich has been increasing. Today’s poor suffer greater relative unhappiness than the poor of past decades. The gap between the poor and the rich is substantial, approximately 0.4 on a 1–3 happiness scale. The increase in the happiness gap is striking: comparing the 1970s to the 2000s, the gap has widened by about 40 % between the poor and the rich, and by about 50 % between the middle class and the rich.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social scientists have argued for decades (Campbell et al. 1976; Diener et al. 1999; Easterlin 1974)—but only recently has it become widely recognized—that income is not a good measure of wellbeing. Amartya Sen, Joseph Stiglitz, Jeffrey Sachs and other economists have proposed using happiness in addition to income as a measure of progress (Helliwell et al. 2012; Stiglitz et al. 2009). What matters, however, is not only the level of happiness, but also its dispersion, and that is still largely overlooked.

There is growing interest in inequality; by far the most popular metric of inequality is income inequality. Academics, politicians, and the media pay attention to income inequality (e.g., Attanasio et al. 2012; Cassidy 2013; Delhey and Dragolov 2014; Economist 2011; Frank 2014; Pickett and Wilkinson 2014; Stiglitz 2012). Usually, those addressing it assume or imply that income inequality results in lower wellbeing, but it is striking how little we know about the actual link between income inequality and inequality in subjective wellbeing or happiness,Footnote 1 particularly because we know so much about the relationship between income and happiness.

Equal income does not guarantee equal outcomes because human abilities to use money and other resources differ greatly; the same income results in different functionings/capabilities for different people (see e.g., Nussbaum 2006; Sen 2000). There is also debate about whether inequality of opportunity or inequality of outcome should be the focus of research and policy. In any case, confining the discussion of inequality to inequality in income is superficial, but also potentially misleading. How do we measure inequality? Ruut Veenhoven, one of the pioneers of happiness research, has offered a suggestion: “income difference falls short as an indicator of inequality […] Instead I propose to measure inequality in another way, not by difference in presumed chances for a good life, but by the dispersion of actual outcomes of life, using the standard deviation of life-satisfaction as an indicator” (Veenhoven 2005, p. 457).

This approach and its modifications (Delhey and Kohler 2010; Delhey and Urlich 2006) provide a broader picture than does an income inequality metric such as the gini coefficient. Yet, variance in happiness as a measure of inequality has limitations as well. Such an approach ignores the connection between income inequalities and happiness inequalities for groups. This study examines the happiness gap between the rich and the poor, directly considering the relationship between income inequality and happiness inequality.

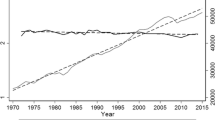

1 Income and Income Inequality

America has doubled its per capita income over the past four decades as shown in Fig. 1, Panel (a). Income and economic growth have resulted in a substantial increase of the average living standards (Bok 2010; Fischer 2010; Veenhoven 2005). By one estimate, today’s bottom decile has a better standard of living than everyone other than the top decile did one hundred years ago (Bok 2010). Americans should have become happier. But we know that the increase in income has not been accompanied by an increase in happiness. This is a well known phenomenon known as the Easterlin Paradox (Easterlin 1974; Easterlin et al. 2010, 2012; Oishi et al. 2011, 2012; Veenhoven and Vergunst 2013). Yet, the paradox is less surprising if we consider the income distribution, as shown in Fig. 1, Panel (b). Indeed, as lamented by Fischer (2008), national income is a woefully inadequate measure of the actual income enjoyed by actual people, because it refers to income per capita on average, disregarding the dispersion from that average. The bottom 20 % of the income distribution did not gain anything from doubling the GDP, and a the bottom 40 % (more than 100 million Americans) gained almost nothing: the upper income limit for the bottom 40 % of families has increased by merely 8 %, from $45,000 in 1972 to $49,000 in 2011 in constant dollars.

Income over time. a Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is gross domestic product divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. b Upper limits for family income fifths. 2011 CPI-U-RS adjusted dollars. Source: US Census Bureau, Table F1, see the link for data footnotes http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/families. a National income (GDP), b personal income

As noted above, income inequality has been the subject of exceptional attention (e.g., Frank 2012; Piketty 2014; Stiglitz 2012). The key question, which the present study attempts to answer, is how rising income inequality over the past four decades has affected wellbeing. This connection between inequality and wellbeing is of key importance, because inequality is a serious problem if it can be shown that it diminishes wellbeing. Wilkinson and Pickett (2006, 2010) have shown many examples of negative effects of inequality, but has been criticized for oversimplifying and choosing selective evidence (e.g., Snowdon 2010).

Some may argue that income inequality is not a problem if people are not unhappy with it. The present study adds direct evidence using a happiness approach: the increasing income inequality gap has been accompanied by an increasing happiness gap. Groups that are further apart on the income dimension are also further apart on the wellbeing dimension. Most studies investigate the link between income inequality and happiness level, not between income inequality and happiness inequality, and find a negative relationship (Alesina et al. 2004; Bartal et al. 2011; Blanchflower and Oswald 2003; Bjørnskov et al. 2013; Graham and Felton 2006; O’Connell 2004; Oishi et al. 2011; Oshio and Kobayashi 2010, 2011; Tricomi et al. 2010; Winkelmann and Winkelmann 2010; Wynne 2004). Two studies have examined the relationship between income and happiness inequalities, but they have reached contradictory conclusions: Berg and Veenhoven (2010) found no effect across countries. Delhey and Kohler (2010) found a negative relationship.Footnote 2

2 Happiness Theories

There are three major theories about how happiness is created. The adaptation theory (Brickman et al. 1978) posits that there is an adjustment to external circumstances, suggesting that people get used to their situations. The second theory, multiple discrepancy theory (MDT; Michalos 1985) asserts that happiness is a result of social comparison or a comparison to various standards, such as in the notion that “It is better to be a big frog in a small pond than a small frog in a big pond” (Davis 1966). The third theory, livability theory (Veenhoven and Ehrhardt 1995) argues that happiness results from objective living conditions and from fulfillment of needs.

According to adaptation theory, inequality should not be much of a problem: people simply adjust to income or lack of it. According to multiple discrepancy theory, inequality will make us less happy because people will feel more relatively deprived compared to others. According to livability theory, inequality will only hurt us to the degree that basic human needs are unsatisfied, that is, that only people in absolute (rather than relative) poverty, or suffering from other deprivation or adversity, will be less happy.

3 Data and Variables

We use American General Social Survey (GSS) data, pooled over 1972–2012. GSS is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey. GSS was administered almost every year until 1994 when it became biennial. The unit of analysis is a person and data are collected in face-to-face, in-person interviews (Davis et al. 2007). The happiness survey item reads, “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days–would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” We coded answers as 1 = “not too happy,” 2 = “pretty happy,”3 = “very happy.”

The key explanatory variable is income. There are many income variables in the GSS. The variable “income” is not informative because half of the respondents are in the highest category, due to its low cutoff point of $25,000. Other income variables, “income72,” “income77,” and so forth, are not comparable because the bins are inconsistent. We use the family real income variable (realinc), which is inflation-adjusted for 1986 dollars. One reason for using family income is theoretical. In technical report no. 64 describing the GSS income variables, Ligon ([1989] 1994) states that the “concept for these two different sorts of measures [respondent and household income] differ as well. Measures of household income attempt to measure income from all sources, while measures of respondent’s income attempt to measure only the respondent’s earnings from a single occupation.”

A person’s happiness is likely to be more affected by family income than by personal income. Indeed, family income correlates twice as highly with happiness as respondent’s income does (0.17 vs. 0.09). Note that Ligon ([1989] 1994) uses the term “household income” to refer to the GSS realinc variable, while we follow the GSS codebook nomenclature and use the term “family income.” Another reason to use family income rather than personal income is logistical. Personal income variables have about 20,000 more missing values than family income variables.

A typical (there are very small changes in wording over time) question asked of respondents is, “In which of these groups did your total family income, from all sources, fall last year before taxes, that is? Just tell me the letter.” In the earliest surveys there were 12 choices, though the number has increased over time to 25. Ligon ([1989] 1994) describes the income variable in detail. “Getting the most out of the GSS income measures” by Michael Hout, Co-Principal investigator of GSS (2004) and the Ligon Report ([1989] 1994) describe the process of generating the income variable used here, which involved three steps. First, GSS researchers turned categories into dollars by using category midpoints as a measure of central tendency within each income category (including the bottom category). Second, they calculated the mean income in the top category using the Pareto distribution. Third, they adjusted dollars for inflation.

We turned this income variable into quintiles and generated a dummy variable for each category. One reason to generate quintiles is technical, in that it enables us to explore nonlinearities. We chose five bins to have sufficient categories to be able to proxy for five classes: poor, working class, middle class, upper-middle class, and rich, and also have a decent sample size per bin. We include robustness tests using alternative categorizations in appendices. While it may seem that aggregating data to bins results in loss of information, income data for this variable were originally derived from categories, making the variable only artificially (and approximately) continuous. Indeed, Ligon ([1989] 1994) advises: “Because of the crudity of the underlying data, both income measures are expressed in hundreds of dollars. Expressing these income measures in hundreds of dollars still implies a false precision for higher levels of income—for many purposes, the user would do well to round to the nearest thousand dollars.”

Survey measures of income suffer from measurment error. While we demonstrate the robustness of our results, future research should investigate with better measures of income when they become available. Currently, GSS is the longest running US survey containing both happiness and income measures. All variable definitions, summary statistics, correlations, and distributions of income and happiness variables for each year of the survey are in “Appendix 1”. We show that rising income inequality is associated with a rising wellbeing gap even after controlling for predictors of happiness. Two key predictors beyond income are health and unemployment (e.g., Blanchflower and Oswald 2011). We also include a typical set of covariates found to play a role in happiness (that is, happiness is in part a function of these): age, age squared, household size, and education. Finally, we control for a number of happiness predictors suggested in the literature to be of particular importance when dealing with various inequalities. Stevenson and Wolfers (2009) note that female happiness is declining, and we include gender because there are well-known inequalities associated with it. Conservatives are happier than liberals (Okulicz-Kozaryn et al. 2014). Politics matter when exploring inequalities. Indeed, liberals almost universally see inequalities as a problem, while conservatives are more ambiguous about it, and often actually supportive of inequality (Okulicz-Kozaryn et al. 2014). Finally, views about inequality are likely to vary across the US.

4 Results

This study aims to find whether the happiness gap between the rich and the poor has changed over the past four decades. Instead of calculating a standard deviation, gini coefficient, or a similar measure of dispersion for society as a whole, we calculate happiness averages for each income quintile for each year. Contrary to a decline in the variance in overall happiness, the happiness gap between the rich and the poor has increased, as shown in Table 1.Footnote 3

The first column (SD) shows the standard deviation in happiness, which was highest in the 1970s, then declined, then increased again after 2000. Subsequent columns show means of happiness by income quintiles. Happiness for the top quintile is quite stable over time at about 2.365. Happiness for the lowest quintile dropped by 0.1 from 2.06 in the 1970s to 1.96 in the 2000s. Likewise, for the second quintile it dropped by 0.1 from 2.18 in the 1970s to 2.08 in the 2000s. The middle quintile registered a substantial drop, too: about 0.06, from 2.23 to 2.17. Happiness ranges from 1 to 3, and hence, a change of 0.1 for 20 % of the American population (roughly 60 million people) is a substantial change in aggregate happiness. Happiness for the two upper fifths stayed roughly flat, and happiness for the bottom 60 % declined. The upper-middle class and rich stayed happy, and everyone else became less happy. Changes are large in relative terms. In the 1970s the gap between the rich and the poor was 0.3 (2.36–2.06); in the 2000s it was 0.41 (2.37–1.96), which is a 37 % increase (0.41–0.3)/0.3. Even more strikingly, the gap between the middle class (third quintile) and the rich (fifth quintile) increased from 0.13 (2.36–2.23) to 0.2 (2.37–2.17), a 54 % increase (0.2–0.13)/0.13.

Given that the overall standard deviation of reported happiness has decreased, why did the happiness gap increase? The total variance depends on within-group variance and between-group variance. Results imply that there was an increase in between-group variance and/or a decrease in within-group variance. The last five columns in Table 1 show standard deviations by income groups. From the 1970s through the 1990s within-group happiness variance decreased. After 2000, the variability increased. Variance in happiness is the largest among the poorest quintile in all decades, demonstrating the the poor are not a monolithic group.

The rich did not become happier even though they became richer. The poor did not retain their happiness despite the fact that their income stayed flat (and if anything increased slightly). If happiness was derived only from satisfaction of needs according to livability theory, the poor’s happiness should not have decreased. Based on multiple discrepancy theory, however, we expect growing income disparities to result in growing happiness disparities. In other words, relative deprivation matters in addition to absolute deprivation.

The differences in Table 1 are significant and they hold when controlling for key predictors of happiness. Table 2 shows the regression results. Column a0a shows that happiness declined over time. In column a0b, each happiness quintile is progressively happier as compared to the lowest quintile. In column a1, the top two quintiles are significantly happier over time compared to the lowest quintile. Column a2 adds controls for two key predictors of happiness, unemployment and health, though due to many missing observations on the health variable, the sample size drops substantially. Finally, column a3 is a saturated model including a number of additional covariates that have been shown to predict happiness as explained above. Model a3 controls for size of household, a key variable when focusing on a family income variable. In model a3 the sample size drops further due to more missing observations, and the results become less significant; the fourth quintile-year interaction is no longer significant, although the positive sign remains.

To present these results in a more intuitive way, Fig. 2 plots predicted values, showing clearly that the happiness gap between the upper-middle class and rich and everyone else is widening. This is similar to the widening income gap shown earlier in Fig. 1b, and confirms the overall happiness-income-time patterns from Table 1. These figures demonstrate that the widening of the gap persists when adding controls for socio-demographic, political, and regional characteristics in model a3. Based on model a1, the gap between the richest and the poorest in 1972 was 0.31 (2.37–2.06) and increased in 2014 to 0.43 (2.38–1.95), a 39 % increase (0.43–0.31)/0.31; and based on the full model (a3), the gap has increased from 0.22 (2.33–2.11) to 0.31 (2.32–2.01), a 40 % increase (0.31–0.22)/0.22. Based on model a1, the gap between middle class (third quintile) and the rich (top quintile) was 0.11 (2.37–2.26), and increased to 0.2 (2.37–2.17), an 82 % increase (0.2–0.11)/0.11. Given the full model (a3), the gap was 0.08 (2.33–2.25), and doubled, increasing to 0.16 (2.32–2.16). These are the end point estimates (1972 vs. 2012), and conservative estimates comparing decades as in Table 1 are more appropriate. Nevertheless, the magnitude is striking.

Predicted happiness and 95 % confidence intervals for quintiles of income (referenced at the very right of the graph). Predicted values are based on Table 2. a specification a1, b specification a2, c specification a3

Using a full set of regressors in model a3, the three bottom quintiles move together, and hence the poor, working, and middle class (lower three quintiles) became equally unhappy as compared to the upper-middle class (fourth quintile), who became only a little less unhappy, and the rich (the top quintile) who largely retained their earlier happiness. Over time, the rich became not only happier than the poor, but also happier than the middle class.

We performed several robustness checks. “Appendix 3” shows happiness by the original income measures, to show that the transformation of the income variable did not distort the results. The results are similar: the happiness gradient by income was less steep in the past, and specifically, the poor of today are less happy than were the poor in the 1970s. “Appendix 4” compares the inequality measures from the GSS to the “official” measures from the Census. “Appendix 5” uses three and seven bins on the income variable as opposed to the five used above. Finally, “Appendix 6” discusses results using personal income as opposed to family income. We also tried multinomial models and the results were similar; it is well known that when modeling ordinal happiness, OLS performs well (Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters 2004). We also tried dropping years that included oversamples and years when the ordering of the questions was changed: 1972, 1980, 1982, 1985, 1986, 1987. Finally, we reran analyses on a sample excluding the post-2008 years to exclude the Great Recession. Results using all these subsamples were substantively similar.

5 Discussion: Relative Deprivation

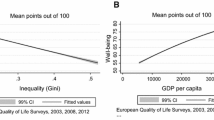

An important limitation, and at the same time a direction for future research is to account for secular trends,Footnote 4 which would require a panel dataset across countries. Cross-country investigation is needed, because using multiple countries provides the most variability in contextual factors. Such an approach is beyond the scope of this study, but a brief discussion is in order.

Perhaps, the increasing gap in happiness between income quintiles is not due to increasing income inequality, but due to increasing costs. Over the past four decades, in addition to stagnant wages, other troubling trends have developed. Healthcare costs have skyrocketed, and education costs have increased even more (Chokshi 2009). Household debt increased, and college debt increased even more, surpassing credit card debt (Stiglitz 2013). One could therefore argue that it is rising costs, not inequality, that is responsible for the decline in happiness among the poor. Yet, costs are a problem for happiness only if there is not enough income to cover those costs, and therefore, insufficient income is the obvious explanation, but it is in part likely due to rising inequality as well. While inequality does not invariably mean worse objective conditions for the poor, it does mean worse relative conditions. And in fact, rising inequality in the US since the 1970s has meant not only that the rich are pulling ahead, but that the poor are falling behind; gains are not widely shared (Gilbert 2011). In the US, income inequality has increased as poverty has deepened (Desmond 2015; Edelman 2012; Edin and Shaefer 2015; Gould and Davis 2015; Massey 2007; Putnam 2015; Shaefer et al. 2015; Stiglitz 2012; Yellen 2006).

Future research could use another dataset to investigate alternative explanations and estimate how much of the happiness gap is due to different factors. The goal of this study is exploratory: to document the widening gap in happiness that attends the widening gap in income. The widening gap in happiness is likely due to the widening gap in income.

These results should not be generalized beyond the US. In addition, confirmation of the causal relationship and empirical exclusion of alternative explanations both remain for future research.

The happiness gap in the US between the rich and everyone else has increased; those at the top stayed happy and others became less happy. We can explain these results in terms of relative deprivation as theorized by Michalos in his multiple discrepancy theory (1985), and we conclude that adaptation theory and livability theory do not provide compelling explanations for our results. One possibility is that people tend to compare themselves to the rich and such comparisons makes them unhappy, but the rich do not become happier by comparing themselves to those with less money. Relative loss is felt more than is relative gain (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Lower income among the poor and middle classes produces more unhappiness than higher income produces increased happiness among those already rich. We know that we compare ourselves to others (Campbell et al. 1976; Michalos 1985; Ng 1997), and therefore, lower income compared to others’ higher income can be felt as a loss. Moreover, once we reach a moderate income, we tend to compare ourselves to those at our level or above (Myers 2004). By one estimate, comparisons to others explain or predict happiness better than do actual resources (Schulz 1995).

We are more unequal in income, and more unequal in wellbeing. Perhaps, this makes sense of the Easterlin paradox: income growth did not cause an increase in happiness because that growth only went to very few people at the top.Footnote 5

Income inequality is only one way of measuring inequality. Happiness inequality is important as well. This study has examined the relation between the two.

Notes

We use the terms subjective wellbeing and happiness interchangeably. Happiness, life satisfaction, and subjective wellbeing do overlap. Although they are to some degree distinct, in the happiness literature it is customary to treat these concepts interchangeably (see e.g., Veenhoven 2008; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Diener and Lucas 1999; Radcliff 2013).

There was a lively discussion between Veenhoven and Delhey, and it resulted in many papers (http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=veenhoven+delhey+inequality). This debate, however, is beyond the scope of this article, which deals with the US and changes over time, not cross-sectional comparisons across countries. The results of the present study do not necessarily conflict with Berg and Veenhoven (2010), who found that across nations there is no correlation between income inequality and average happiness. It is even possible that income inequality can add to average happiness in many countries by increasing the pie, though probably not anymore in the US—some economists think that current levels of inequality in the US are bad for the economy. Income inequality can actually hurt the economy, not only society (The Economist 2012a, b, 2013). Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) found happiness inequality to be decreasing, but they did not establish a connection with income inequality. Easterlin (2001) focused on happiness by income, but only at one point in time. Blanchflower and Oswald (2004) looked at change over time, but at the effect of income on happiness, not on the effect of income inequality on happiness inequality.

General reduction of inequality in happiness or reduction between some two groups, say racial groups, can co-exist with increasing inequality in the happiness across income groups. Taking Using a public health analogy, the life expectancy gap between Blacks and Whites has decreased but the life expectancy gap between the educated and the uneducated has increased (Meara et al. 2008).

We are grateful for this suggestion to an anonymous reviewer who pointed out a need: “to find a convincing way of handling trends other than the increase in inequality, which may be causing changes in the level and distribution of happiness.”

However, the Easterlin Paradox is observed in many countries, and our explanation may not hold up across the board—we are grateful for this point to Richard Easterlin.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Attanasio, O., Hurst, E., & Pistaferri, L. (2012). The Evolution of Income, Consumption, and Leisure inequality in the US, 1980–2010. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bartal, I., Decety, J., & Mason, P. (2011). Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science, 334, 1427–1430.

Berg, M., & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. repub.eur.nl.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., Fischer, J. A., Schnellenbach, J., & Gehring, K. (2013). Inequality and happiness: When perceived social mobility and economic reality do not match. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 91, 75–92.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2003). Does inequality reduce happiness? Evidence from the states of the USA from the 1970s to the 1990s. Mimeographed, Warwick University.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2011). International happiness: A new view on the measure of performance. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 25, 6–22.

Bok, D. (2010). The politics of happiness: What government can learn from the new research on well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Buman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 917–927.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cassidy, J. (2013). American inequality in six charts. New York: The New Yorker.

Chokshi, N. (2009). Education costs rising faster than health care. Washington: The Atlantic.

Davis, J. A. (1966). The campus as a frog pond: An application of the theory of relative deprivation to career decisions of college men. American Journal of Sociology, 72, 17–31.

Davis, J. A., Smith, T. W., & Marsden, P. V. (2007): General Social Surveys, 1972–2006 [Cumulative File], Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Delhey, J., & Dragolov, G. (2014). Why inequality makes Europeans less happy: The role of distrust, status anxiety, and perceived conflict. European Sociological Review, 30, 151–165.

Delhey, J., & Kohler, U. (2010). Is happiness inequality immune to income inequality? New evidence through instrument-effect-corrected standard deviations. Social Science Research, 40(3), 742–756.

Delhey, J., & Urlich, K. (2006). From nationally bounded to Pan-European inequalities? On the importance of foreign countries as reference groups. European Sociological Review, 22, 125–140.

Desmond, M. (2015). Severe deprivation in America: An introduction. RSF 1(2):1–11. http://www.rsfjournal.org/doi/full/10.7758/RSF.2015.1.2.01. Retrieved 12 Jan 2016.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. R. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In E. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 213–229). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., & Lucas, R. E. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (Vol. 89, pp. 98–125). New York: Academic Press Inc.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111, 465–484.

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 22463–22468.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 9775–9780.

Edelman, P. (2012). So rich, so poor: Why it’s so hard to end poverty in America. New York: The New Press.

Edin, K. J., & Shaefer, H. L. (2015). $2.00 a Day: Living on almost nothing in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Fischer, C. S. (2008). What wealth-happiness paradox? A short note on the American case. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 219–226.

Fischer, C. S. (2010). Made in America: A social history of American culture and character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Frank, R. H. (2010). Hey, big spender: You need a surtax. New York: New York Times.

Frank, R. (2012). The Darwin economy: Liberty, competition, and the common good. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Frank, R. H. (2014). The vicious circle of income inequality. New York: New York Times.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic literature, 40(2), 402–435.

Gilbert, D. L. (2011). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Gould, E., & Davis, A. (2015). Persistent poverty’s largest cause is inequality, not family structure. August 10. https://thesocietypages.org/families/2015/08/10/poverty-caused-by-inequality-not-family-structure/. Retrieved 17 Feb 2015.

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4, 107–122.

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2012). World happiness report. New York: The Earth Institute, Columbia University.

Hout, M. (2004). Getting the most out of the GSS income measures. Washington: National Opinion Research Center.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Ligon, E. ([1989] 1994). The development and use of a consistent income measure for the General Social Survey. National Opinion Research Center, The University of Chicago

Massey, Douglas S. (2007). Categorically unequal: The American stratification system. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Meara, E. R., Richards, S., & Cutler, D. M. (2008). The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs, 27, 350–360.

Michalos, A. (1985). Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413.

Myers, D. G. (2004). Exploring psychology. London: Macmillan.

Ng, Y.-K. (1997). A case for happiness, cardinalism, and interpersonal comparability. The Economic Journal, 107, 1848–1858.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Conversations with History: Martha Nussbaum. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qy3YTzYjut4&list=PLDmIbYyjfK8BAq8q-ZYzakLXnGtQ8PS0I&index=147.

O’Connell, M. (2004). Fairly satisfied: Economic equality, wealth and satisfaction. Journal of Economic Psychology, 25, 297–305.

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22, 1095–1100.

Oishi, S., Schimmack, U., & Diener, E. (2012). Progressive taxation and the subjective well-being of nations. Psychological Science, 23, 86–92.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., Holmes IV, O., & Avery, D. R. (2014). The subjective well-being political paradox: Happy welfare states and unhappy liberals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1300–1308.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2010). Income inequality, perceived happiness, and self-rated health: Evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 1358–1366.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2011). Area-level income inequality and individual happiness: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 633–649.

Pickett, K. E. & Wilkinson, R. G. (2014). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–326.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam, Robert D. (2015). Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Radcliff, B. (2013). The political economy of human happiness: How voters’ choices determine the quality of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schulz, W. (1995). Multiple-discrepancies theory versus resource theory. Social Indicators Research, 34, 153–169.

Sen, A. (2000). Development as freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Shaefer, H. L., Edin, K., & Talbert, E. (2015). Understanding the dynamics of $2-a-day poverty in the United States. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 1(1):120–38. http://www.rsfjournal.org/doi/full/10.7758/RSF.2015.1.1.0. Retrieved 12 Jan 2016.

Snowdon, C. (2010). The spirit level delusion: Fact-checking the left’s new theory of everything. Ripon: Little Dice.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Happiness inequality in the United States. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2009). The paradox of declining female happiness. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1, 190–225.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2012). The price of inequality: How today’s divided society endangers our future. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2013). Student debt and the crushing of the American dream. New York: The New York Times.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2009). Report by the Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr.

The Economist. (2011). The rich and the rest What to do (and not do) about inequality. Economist.

The Economist. (2012a). For richer, for poorer. The Economist.

The Economist. (2012b). True progressivism. The Economist.

The Economist. (2013). Having your cake; Less inequality does not need to mean less efficiency. The Economist.

Tricomi, E., Rangel, A., Camerer, C., & O’Doherty, J. (2010). Neural evidence for inequality-averse social preferences. Nature, 463, 1089–1091.

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Return of inequality in modern society? Test by dispersion of life-satisfaction across time and nations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 457–487.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Sociological theories of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being: A tribute to ed Diener (pp. 44–61). New York: The Guilford Press.

Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34, 33–68.

Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (2013). The Easterlin illusion: economic growth does go with greater happiness. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper No. 43983.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2006). Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 1768–1784.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2010). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (2010). Does inequality harm the middle class? Kyklos, 63, 301–316.

Wynne, C. (2004). Animal behaviour: Fair refusal by capuchin monkeys. Nature, 428, 140–140.

Yellen, J. (2006). Economic inequality in the United States. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF) Economic Letter, 2006-33-34 (December 1, 2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Ruut Veenhoven. We take full responsibility for any errors or weaknesses that remain.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Additional Descriptive Statistics

See Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and Tables 3, 4, 5.

Happiness by deciles of income. Results are similar to those in Fig. 5: happiness is stable for the rich and declining for the poor

Appendix 2: Other Variables by Income Quintiles Over Time

Generalized trust: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” The higher the value, the more trust. There is little difference by income, but a very clear pattern in the overall trend exists as documented by many others (e.g., Putnam 2001): Americans report lower trust than in the past

Support for government action to reduce income differences. The higher the value, the greater the support. Numbers 1–5 shown at the right side of the graph denote income quintiles. As expected, the poorer the group, the more support there is for reducing income differences. Yet, the biggest increase in favor of redistribution is among the richest

Opinions about fairness. The higher the value, the more agreement that “people try to take advantage of you as opposed to be fair.” Along with the increasing income gap, there was an increase amongst the poorest in the opinion that people are taken advantage of. Numbers 1–5 shown at the right side of the graph denote income quintiles

Appendix 3: Happiness by Original Income Measures

See Fig. 10.

Happiness by original income measures. 95 % CI shown. The top row shows the two earliest income measures (gss names: income72 and income77). The bottom row shows the latest income measures (gss names: income98 and income06). Vertical lines are drawn to aid interpretation. In all years happiness for the richest is approximately 2.4. But there is a change for the poorest: in the 1970s it was approximately 2.0, but in the last decade it was below 2.0 (about 1.9). There are also some interesting irregularities: for instance, the least happy are not the poorest

Appendix 4: Comparison of Inequality Measures from GSS and from Census

Gini data from the Census Bureau come from Table F-4 “Gini Indexes for Families, by Race and Hispanic Origin of Householder: 1947 to 2014,” available at https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/inequality. Note that this gini index is for families (in this paper we use family income from the GSS). Furthermore, it is worth noting that from 1947 until 1972, when the GSS series began, the gini decreased only slightly and reached a low of 0.348 in 1968 before increasing, through to the present day. Data are plotted in graph 1. The correlation between the two series is 0.85. There is a spike in the GSS gini, another reason to rerun the analyses without the post-recession years. Yet, both series show a virtually identical linear trend as shown by fitted values (Fig. 11).

Data on income quintiles from the GSS and the Census are shown in Figs. 12 and 13. The Census data use 2011 constant dollars. The GSS uses 1986 constant dollars. The quintiles are more uneven for the GSS series. Incomes are estimates in the GSS and, for many years, not very continuous but rather, are presented more discretely. This limitation is unfortunate, particularly because these are the only data available that are consistent series and go back as far in time. The series are especially inconsistent in earlier years when there were fewer income categories, and so the cutoff points for quantiles are coarser. The fit between the two series is not close; to check whether the results might have been due to quantization, we reran the analyses using 3 and 7 classes (see “Appendix 5”). Results are similar.

Upper limits for family income fifths. 2011 CPI-U-RS adjusted dollars. Source: US Census Bureau, Table F1, see the link for data footnotes: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/families

Appendix 5: Robustness Checks: Using 3 and 7 Classes

Stata (the statistical software used in this study) performs quantization (assigns variable values into quantiles) in a peculiar way by checking whether it passes the appropriate percentile for given quantile and if it does not, it uses the lower quantile for categorization. This yields non-optimal cutoff points when a variable has few levels. For instance, in 1972 real income has the following distribution:

Income | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

2707 | 123 | 8.34 | 8.34 |

8122 | 165 | 11.19 | 19.54 |

13,537 | 160 | 10.85 | 30.39 |

18,951 | 160 | 10.85 | 41.25 |

24,366 | 192 | 13.03 | 54.27 |

30,458 | 217 | 14.72 | 69 |

37,226 | 159 | 10.79 | 79.78 |

43,994 | 103 | 6.99 | 86.77 |

50,763 | 63 | 4.27 | 91.04 |

60,915 | 67 | 4.55 | 95.59 |

74,452 | 33 | 2.24 | 97.83 |

109,355 | 32 | 2.17 | 100 |

Total | 1474 | 100 |

Hence, an optimal solution is to classify only the first two categories (2707, 8122) into the first quintile (they constitute 19.54 percent of the distribution), but Stata takes the third category as well (13,573), because it does not reach 20 % after taking the first two. This peculiar approach has been documented on the Stata listserv by Stata’s foremost expert Nick Cox http://www.stata.com/statalist/archive/2012-06/msg01193.html, and at http://www.stata.com/statalist/archive/2012-06/msg01187.html. An obvious question is what if the study’s result—that the poor and rich are more unequal in happiness—is due to this strange clustering? We use 3 and 7 bins as a robustness check. Results hold up as shown in Tables 6 and 7.

Appendix 6: Family Income Versus Personal Income

There are theoretical and technical reasons for using family income as opposed to individual income, but for robustness, we discuss here the results using personal income. With respect to family income reported here there is a rather smooth gradient: the richer the group, the smaller the decrease in happiness over time, and as a result the bigger the gap in happiness. With respect to respondents’ income, this is still true when comparing the first quintile to the others: the poorest people became less happy over time. Richer groups remained more flat in their happiness, so the happiness gap between the poorest and the rest has increased. The key difference in results when using personal income is that all richer income groups remained at about the same happiness levels over time, so whatever happiness differences there were in the 1970s, they remained after the 2000s. In addition, the very richest group became slightly less happy, though not nearly by as much as the poorest group. The three middle quintiles remained most stable over time. For the reasons mentioned above, family income is a better measure, and we base our overall conclusions on the family income variable. These results do not generalize entirely when using personal income. In particular, the happiness gap between the richest and middle class has not increased if individual income is used instead of family income.

Finally, we reran models using family income divided by the natural log of the number of people in the household +1 (to avoid zero from ln(1)). The effect of family income on happiness depends in part on the number of people in a household. The rationale for dividing family income by the natural log of the number of people in a household is to scale the effect to reflect the diminishing marginal effect of each additional member of a household on family income (the addition of each subsequent member of a household “costs” less).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., Mazelis, J.M. More Unequal in Income, More Unequal in Wellbeing. Soc Indic Res 132, 953–975 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1327-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1327-0