Abstract

This article examines the role of income status and policy context in jointly determining public responses to taxation policies. Based upon the notion that taxpayers’ self-interested preferences are inextricably intertwined with the policy context, I hypothesise that high-income taxpayers react differently to taxation policies depending on their perceived tax burden associated with tax policy structures. Using international social survey data, I find that the link between income and tax support is conditioned by the tax system within which taxpayers are contextually situated. In countries with comparatively high levels of direct taxes, high-income taxpayers react more negatively to higher and more progressive taxation than do low-income counterparts. In contrast, in low-tax societies, attitudinal cleavages among income classes become less intense. Moreover, the results reveal that the impact of income on tax attitudes does not significantly vary across countries with different degrees of tax concentration. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications of these findings and directions for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Redistributive schemes are unlikely to succeed in the absence of public support for taxation policies. It is crucial for governments to mitigate potential tax revolts and other public reactions that may undermine the financial basis of the social security system, especially in times of fiscal retrenchment and increasing inequality (OECD 2008). Political scientists and sociologists have invested a great deal of effort into identifying the sources of citizen-initiated tax revolts (Lowery and Sigelman 1981; Beck and Dye 1982; Sears and Citrin 1982; Beck et al. 1990; Bowler and Donovan 1995; Bartels 2005; Rudolph 2009). One of the most common explanations is the economic self-interest hypothesis, namely, taxpayers behave in accordance with their material benefits and costs. For example, this view predicts that individuals with affluent economic resources and low market risks are more likely to manifest anti-tax sentiments than do less privileged categories. Indeed, previous empirical studies have shown that high-income earners are less in favour of progressive tax policies than low-income earners (Edlund 2000, 2003).

We know less, however, about the potential role of existing policy structures in shaping individual-level tax attitudes. The basic intuition here is that the development of self-interested preferences is not an ‘atomistic’ procedure but rather is inextricably embedded in social contexts (i.e., institutional settings). Put differently, self-interest and institutionalist theories are not independent of each other, but rather they simultaneously contribute to the development of taxpayers’ policy attitudes. To date, such joint mechanisms have not been fully investigated, and several questions remain unanswered. For example, do taxpayers alter their preferences in response to the institutional context in which they are situated? If so, which tax policy dimensions are most responsible for these context effects? More specifically, do high-income taxpayers resist further tax increases or progressive taxation in the same (or in a similar) manner regardless of the institutional environment? To answer these questions, the present paper explores how taxpayers contextualise their self-interest within a given policy situation. This is important for at least two reasons. First, it contributes to the policy-feedback literature by confirming that existing (tax) policy legacies can influence how citizens (taxpayers) perceive the potential gains and losses associated with a particular (tax) policy scheme. Second, the social policy literature dealing with the relationship between policy structures and mass politics has mainly focused on the ‘spending side’ of redistributive government (i.e., social benefits and services), whereas much less attention has been devoted to its ‘financing side’ (i.e., tax burden). The present paper aims at filling this lacuna by linking the literature: mass feedback effects and class politics over taxation policy.

The goals of this project are threefold. First, it focuses on two tax policy features: (1) the absolute amount of direct taxes; and (2) the relative distribution of tax burden across different income classes. In particular, the impact of the latter dimension (i.e., tax concentration) on tax preferences has barely been tested in existing studies. Second, this paper provides a theoretical framework for how these two institutional circumstances affect voters’ tax preferences. Although the role of individual-level attributes in determining tax attitudes has been well documented in previous studies (Edlund 2000, 2003), the theoretical mechanisms underlying the association between tax policy contexts and mass attitudes remain unclear. This paper argues that the self-interested calculus of taxpayers is not exogenous but depends on the institutional arrangements in which stakeholders are socially located. Specifically, it hypothesises that the effect of income status on tax attitudes varies according to the perceived tax burden associated with a given tax system. Third, using survey data from 19 rich and middle-income societies, this paper provides empirical evidence for the claim that income and tax schemes jointly affect outcome attitudes. I find that the downward impact of higher income is less prominent in countries with lower levels of direct taxes. Moreover, the empirical results reveal that the context effect of tax concentration is rather limited. In other words, the relationship between income and tax support does not significantly differ across countries with different levels of tax concentration.

2 Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1 Self-Interested Tax Attitudes

Economic self-interest has been regarded as an influential driving force in shaping voters’ preferences towards redistributive policies (Romer 1975; Roberts 1977; Meltzer and Richard 1981). Individuals with lower labour market positions—i.e., those with few economic resources and high market risks—are expected to favour government-led social services because they tend to be the beneficiaries of such services. Conversely, grievances against redistributive government would be most prevalent among affluent, low-risk categories who contribute to the financing of such schemes. In essence, this approach assumes that individuals behave opportunistically based on a self-interested calculus. Scholars have argued that demographic profiles such as gender, age, employment status, and social class evoke distinctive patterns of self-interested responses. Those who benefit from the welfare system—e.g., females, the elderly, the unemployed, and low-income earners (or manual labourers)—are assumed to have strong incentives to defend it. This prediction has been evidenced by several empirical investigations (Hasenfeld and Rafferty 1989; Svallfors 1997; Edlund 1999a; Linos and West 2003; Jæger 2006; Sumino 2014).

The self-interest approach is equally applicable to the analysis of individuals’ preferences towards taxation. Given that one’s relative position on the income ladder directly affects his or her actual and perceived tax burden, we can assume that income position acts as an immediate trigger for the formation of self-interested aspirations regarding tax policies. The feeling of being burdened by the demands of the welfare state is expected to be most intense among high-income contributors and less so among low-income beneficiaries (Sears and Citrin 1982; Sears and Funk 1990), which in turn generates attitudinal polarisation among individuals with different income resources. Despite the logic, the empirical evidence is somewhat inconclusive. Some studies find systematic differences in tax attitudes among income groups (Edlund 2000; Barnes 2015), while others find no such differences (Lowery and Sigelman 1981). Thus, the first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1

Attitudinal polarisation towards tax policies exists among different income classes. High-income earners are less willing to favour higher and more progressive taxation.

2.2 Institutional Feedback Effects—Tax Level and Concentration

Another theoretical approach is the institutionalist model, which emphasises the role of institutions (or policy structures) in preference development. This approach contends that policies, once put in place, have ‘feedback effects’ on political processes (Skocpol 1992; Pierson 1993; Mettler and Soss 2004). Policies are not only the consequence of political struggles (Easton 1953; Brooks and Manza 2006) but also the cause of political forces that reshape political actors’ interests, identities, and cognitive interpretations of the social world. Policies generate resources and incentives that influence the ways in which political actors define the gains and losses of various courses of action. Echoing this idea, the social policy literature has argued that different entitlement schemes—universalistic versus targeted programmes—produce distinct patterns of social stratification (Korpi 1983; Esping-Andersen 1990; Korpi and Palme 1998; Rothstein 1998, 2002; Larsen 2007). On the other hand, Svallfors (1997, 2003, 2004) suggests that although the overall level of support for redistribution significantly differs across welfare regime types (higher support in the social democratic regime than in the radical and liberal counterparts), clear cleavage structures do not exist between countries (see also Papadakis and Bean 1993; Bean and Papadakis 1998; Edlund 1999a; Gelissen 2000; Arts and Gelissen 2001; Andreß and Heien 2001; Linos and West 2003; Jæger 2006; Larsen 2007).

Drawing on these arguments, one can assume that mass publics react opportunistically according to the incentives and constraints inherent in tax policy structures. This implies that the self-interest calculus discussed above is not an ‘atomistic’ procedure but rather is embedded in a given tax policy environment. In other words, stakeholders’ reactions to tax policies are not uniform but differ systematically depending on the policy context, within which they contextualise their self-interested calculations. In brief, the linkage between income status and tax attitudes (Hypothesis 1) might be conditioned—either strengthened or weakened—by existing tax policy structures.

Then, which policy features may have an interaction effect on voters’ attitudes towards taxation? I suggest two policy dimensions—tax level and tax concentration—that seem to have particular relevance to taxpayers’ self-interest. ‘Tax level’ refers to the overall amount of taxes levied on households, while ‘tax concentration’ refers to the distribution of tax burden across income groups. These policy dimensions are conceptually distinct, the former reflecting the absolute level of tax burden, whereas the latter reflecting the relative share of tax burden among households with different income resources. In the paragraphs that follow, I explain how these two policy features may contribute to the development of public opinion.

Tax level may have an interaction effect on the relationship between income status and tax attitudes. In countries with high tax levels, taxation policies are relatively visible to stakeholders and thus, are often recognised as a potential challenge to the pursuit of self-interested goals. A heavier tax burden increases the perceived tax price associated with social services and instils anti-tax sentiments especially among those who bear a relatively high ‘tax cost’ (i.e., the upper income class). As a result, in high-tax countries, the conflict of interest among different income categories becomes more salient and acute. By contrast, in low-tax societies where tax burdens are comparatively small or even ‘latent’, attitudinal polarisation among income classes becomes minor.Footnote 1 The argument can be summarised as follows:

Hypothesis 2a

Attitudinal differences across income classes become more evident in high-tax societies. High-income taxpayers are more reluctant to support taxation policies in countries with higher levels of direct taxes.

When examining the above proposition, this study pays particular attention to the level of direct—rather than indirect—taxation for two reasons. First, direct taxes are more visible and subject to public attention and scrutiny. Wilensky (1975, 1976) suggests that the composition of taxation can affect mass perceptions towards tax burdens, arguing that countries relying on visible forms of taxation (e.g., direct taxes on personal income) are more likely to face welfare backlash than those relying on less visible ones (see also Coughlin 1980; Hibbs and Madsen 1981). People are more sensitive (or responsive) to direct taxes than to less visible forms of taxation because the high visibility of direct taxes stimulates a feeling of ‘being burdened’, and this in turn provokes public discontent against redistributive government. Second, given that one’s income status serves as the initial basis for self-interested calculations (Hypothesis 1), direct taxes on earned income play a more relevant role than do indirect taxes (e.g., sales and value-added taxes) in conditioning the income-attitude linkage. In other words, since the aim of this study is to test how different income groups react to taxation policies in different policy contexts, it is theoretically consistent to focus on direct taxes levied on income rather than indirect taxes levied on goods and services.Footnote 2

Tax concentration may have an interaction effect on the link between income and taxpayers’ responses. This idea derives from the work of Korpi and Palme (1998), in which they argue that the disproportionate distribution of transfer benefits gives rise to a zero-sum competition between net beneficiaries and net contributors. Welfare state institutions characterised by means-tested low-income targeting tend to split the population into those who benefit from the transfer scheme and those who do not, which leads to divergent definitions of interests and identities among social classes. Although the Korpi and Palme’s (1998) model focuses on the benefit side of redistributive politics, the underlying logic can be extended to the financing side. That is, an unevenly distributed tax burden may affect the formation of interests and identities among different income categories—in countries where tax burdens are disproportionately concentrated in certain households (e.g., high-income earners), attitudinal cleavages become more intense than in countries where household taxes are proportionally distributed. This argument leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2b

Attitudinal differences across income classes grow wider in countries with concentrated taxation. High-income taxpayers become more reluctant to support taxation policies in countries where tax costs are unevenly (or ‘unfairly’) distributed across income groups.

Empirical evidence on the link between policy features and tax attitudes is sparse and inconsistent. For instance, Jaime-Castillo and Sáez-Lozano (2014) operationalise ‘direct taxation’ as the sum of direct taxes (i.e., incomes, profits, capital gains, and payrolls taxes) as a percentage of GDP, and demonstrate that attitudinal differences among socio-economic (occupational) classes are more salient in the context of higher direct taxes.Footnote 3 In contrast, Barnes (2015, supplementary material) finds no systematic relationship between tax schemes (tax level and progressivity) and mass attitudes (see also Ariely 2011).

3 Data and Measures

3.1 Data

The analysis is based on data from the ‘Role of Government IV’ module of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) collected during 2005–2008. Although the ISSP contains data from over 30 countries around the globe, the estimations were carried out using the data from 19 rich and middle-income societies for which key macro-level indicators (OECD 2008) are fully available.Footnote 4 After listwise deletion of missing cases, the effective sample sizes for the final models were 18,812 (tax level attitude) and 18,940 (tax progressivity attitude).Footnote 5

3.2 Measures

The dependent variables—support for taxation policies—were measured using the following three response items:

Generally, how would you describe taxes in [R’s country] today? (We mean all taxes together, including wage deductions, income tax, taxes on goods and services and all the rest)Footnote 6

First, for those with high incomes, are taxes too high (coded −1), about right (0), or too low (+1)?Footnote 7

Next, for those with middle incomes, are taxes too high (−1), about right (0), or too low (+1)?

Lastly, for those with low incomes, are taxes too high (−1), about right (0), or too low (+1)?

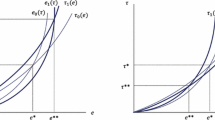

On the basis of these items, I calculate two similar, yet conceptually distinct, tax attitude indicators: the tax level index and the tax progressivity index. To do so, I follow the procedure described by Edlund (1999a, b, 2000). The first measure, tax level index, reflects respondents’ attitudes towards the overall amount of taxes, calculated by (thi + tmi + tli)/3, where ‘thi’ is the response score for the first item (taxes for those with high incomes), ‘tmi’ is the response score for the second item (taxes for those with middle incomes), and ‘tli’ is the response score for the third item (taxes for those with low incomes). The second measure, tax progressivity index, taps respondents’ attitudes towards the tax burden imposed on high-income earners when compared with that on their low-income counterparts, defined by (thi − tli)/2. The former measure concerns one’s support for overall tax increases regardless of the target group (high-, middle-, or low-income groups), while the latter measure represents one’s support for tax increases for high-income groups relative to low-income groups. Both measures can range from −1 (strongest agreement with lower or proportional taxation) to +1 (strongest agreement with higher or progressive taxation). As presented in Fig. 1, the two attitude indices vary substantially within and across countries. Overall, support for higher and more progressive taxation is most prominent in South Korea, Germany, and Slovak Republic, and least so in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. The two outcome variables are moderately correlated (pooled data: Spearman’s ρ = .41) but were estimated separately.

Distribution of tax attitudes by country. Notes Two indices range from −1 (lowest support for tax increases and progressivity) to +1 (strongest support for tax increases and progressivity). For the tax level attitude index (left), countries are sorted by the proportion of the sum of ‘+1’, ‘+.67’ and ‘+.33’, while for the tax progressivity attitude index (right), countries are sorted by the proportion of ‘+1’. N = 18,812/18,940

The primary independent variable of interest is income status. The ISSP 2006 contains country-specific variables coding respondents’ household incomes. Actual/continuous income values are available for some countries, while for others, only income ranges/categories are given. For example, the income categories for the United States are as follows:

Less than $1000 per year

From $1000 up to $2999

From $3000 up to $3999

[…]

From $110,000 up to $129,999

From $130,000 up to $149,999

More than $150,000

To convert these income intervals into pseudo-continuous scales, the midpoint of each bracket was assumed as a proxy for actual income—e.g., less than $1000 = $500, from $1000 up to $2999 = $2000, from $3000 up to $3999 = $3500, and so on (see Rueda et al. 2014; Rueda 2014; Rueda and Stegmueller 2015). The midpoint of the last open-ended category (e.g., more than $150,000) was extrapolated from the frequencies of the next-to-top and the top categories using a Pareto formula proposed by Hout (2004).Footnote 8 Next, to take into account the differences in price levels across countries, income values were adjusted by purchasing power parities (PPPs) for actual individual consumption in national currencies per US dollar (OECD 2006; see also OECD 2012). Finally, to adjust for differences in household compositions, household incomes were deflated using an equivalence scale of the square root of household size (Buhmann et al. 1988).Footnote 9 To reduce skewness, income values were transformed with a natural logarithm prior to analysis.Footnote 10

Income and occupational classes are often regarded as interchangeable proxies for social stratification. Occupational status, defined using the International Socio-Economic Index (Ganzeboom et al. 1992) or the Erikson-Goldthorpe class schema (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992), could be considered an alternative option for analysing the impact of social stratification on tax attitudes. It could be argued that one’s position on the income ladder presupposes one’s occupational status in the labour market, and not vice versa. Nonetheless, the present study focuses exclusively on income position not only because the inclusion of the occupational status measure substantially reduces the number of effective observations but also because, as discussed above, tax burdens and corresponding reactions to tax policies (progressive income taxes, in particular) are determined primarily by one’s position in the income distribution, not by one’s occupational class.

Demographic characteristics that have been shown to affect tax attitudes (Lowery and Sigelman 1981; Edlund 1999b, 2003) were included as background controls: gender (female = 1, male = 0), age (years divided by 10), educational attainment (dummies for no formal qualification, lowest formal, above lowest, higher secondary, above higher secondary, and university degree), and working status (dummies for full-time, part-time or less, unemployed, student, retired, housekeeping, and others).Footnote 11 In particular, including ‘educational attainment’ as a potential confounder adds strength to the causal inferences because education may affect both one’s current labour income (cause) and perceptions towards taxation (effect/outcome).

The key macro-level factors are tax level and concentration. The level of taxes was measured by the share of taxes in household income (OECD 2008). This index reflects cross-national differences in the absolute amount of taxes imposed on households. Higher values indicate higher levels of income taxes and social security contributions. On the other hand, the concentration (or dispersion) of taxes was gauged by the concentration coefficient of household taxes, which taps the extent to which household taxes are disproportionately allocated across different income groups (OECD 2008). The concentration index is calculated in the same way as the Gini index: a score of zero indicates that all income groups pay an equal share of household taxes; a higher value indicates a more ‘unequal’ (concentrated) distribution of tax payments; a lower value indicates a more ‘equal’ (proportional) tax policy.

As presented in Fig. 2, there is larger cross-national variation in the level of taxes than the concentration index. In the tax level measure, household taxes account for more than 30 % of household income in the Nordic countries (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland), Switzerland, and Germany, while the share is less than 10 % in South Korea. On the other hand, the concentration coefficients of household taxes are highest in liberal market economies (the United States, Ireland, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada), and by far the lowest in Switzerland, followed by Sweden and Denmark. The two measures were only moderately correlated with each other (Pearson’s r = −.40; p > .05).

Variation in tax level and concentration across 19 countries. Source OECD (2008)

The two tax policy indices have an advantage over national-revenue measures such as the level of tax revenues as a percentage of GDP. It seems quite demanding to assume that the general public is well informed about their domestic tax-revenue structure. If individuals are not adequately aware of the revenue structure and its implications,Footnote 12 then it makes no sense to argue that individuals alter their self-interested calculations and subsequent reactions to taxation according to the policy context. In this respect, the tax policy measures used in the present study—the share of taxes in household income and the concentration of taxes across households—are more closely linked to personal self-interest and policy perceptions as they are designed to assess the tax burden at the household level. In contrast, national-revenue measures are less tangible for the general public, and thus, are less likely to contribute to the formation of individuals’ preferences.

As a country-level control, I include ‘market income inequality’, measured by the Gini index of pre-tax and transfer income (OECD 2005). Although not the main interest of this paper, existing income disparities might significantly affect the causal mechanisms tested here. First, the degree of concentrated taxation may be greater in countries where the distribution of market income is highly unequal. In other words, market income inequality might be a confounding factor for both tax progressivity and outcome attitudes. Moreover, drawing on Meltzer and Richard (1981), one could assume that income inequality (i.e., country-level context) might be associated with public demand for redistribution, namely the interaction effect of inequality on the link between income status and outcome attitudes (Finseraas 2009; Schmidt-Catran 2014). To test this alternative hypothesis, I use ‘pre-tax and transfer Gini’ (i.e., market income inequality) rather than ‘post-tax and transfer Gini’ (i.e., disposable income inequality) not only because the Metzler and Richard model originally refers to pre-tax and transfer market income inequality (Finseraas 2009) but also because post-tax and transfer inequality reflects (or includes ‘information’ about) the degree of redistributive efforts in a given country. ‘Redistribution’ can be defined as the reduction in inequality produced by taxes and social transfers (Wang and Caminada 2011):

As this definition suggests, ‘ginipre’ refers to the initial level of income inequality created in the labour market prior to redistribution (r), whereas ‘ginipost’ refers to the level of inequality adjusted by redistributive efforts, including taxation policies. Given that ‘taxation policies’—tax level and concentration—are the key explanatory variables of interest in this paper, it seems plausible to rule out any factors that reflect the degree of government intervention (i.e., taxes and social transfers) from the income inequality measure. Using ‘post-tax and transfer income inequality’, which conceptually overlaps with ‘redistributive policy’, makes it difficult to discern the effect of market inequality and that of government efforts such as redistributive taxation.

Another macro-level control is ‘economic affluence’, defined as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP) in US dollars (IMF 2005). One could argue that the salience of class conflicts differs across countries with different levels of economic development. More specifically, attitudinal differences between income classes might be less salient in economically advanced countries. In societies where citizens in general have abundant economic resources to buy basic needs such as food and shelter, differences in attitudes towards redistributive taxation may become minor because both the rich and the poor do not ‘desperately’ depend on redistributive schemes. Thus, we can expect a (relatively) similar amount of support from the rich and the poor. On the other hand, in relatively impoverished societies, public attitudes deviate among different income groups because government redistribution serves as a ‘refuge of last resort’ that protects the very poor from disruptive market forces. In this scenario, we can expect an ‘unbalanced’ support from the rich and the poor—i.e., a very strong support from the poor and a relatively weak support from the rich.

3.3 Analytical Approach

A multilevel modelling approach was applied to examine hierarchically nested samples and to jointly test the explanatory power of both individual- and country-level factors (Goldstein 1995; Kreft and De Leeuw 1998; Snijders and Bosker 1999). Given the ordinal/categorical nature of the outcome measures, I used an ordered logit link function. All models were estimated using MLwiN version 2.30 (Rasbash et al. 2014).

4 Results

The estimated results are shown in Tables 1 (tax level) and 2 (tax progressivity). As shown in the empty models (models 0a and 0b), the estimated between-country variances were .219 and .328, with VPCs (variance partition coefficients) of .062 and .091, indicating that approximately 6.2 and 9.1 % of the variations in the outcome variables are accounted for by differences between level-2 cohorts.

In models 1a and 1b, a set of individual-level variables was added. As predicted in Hypothesis 1, the effects of income status are negative and highly significant (p < .001), suggesting that high-income groups prefer lower and proportional tax policies. This is true even after allowing income slopes to vary across countries (models 2a and 2b). Several demographic controls were found to be significantly related to tax attitudes. Interestingly, highly educated respondents (with university degrees) accept tax increases, whereas they express resistance to a disproportionate taxation; support for tax increases and progressive taxation is stronger among the elderly, with a slight levelling off in the higher age categories; being a woman is associated with greater support for tax progressivity but not with support for tax increases; compared with full-time workers, students and retired persons express support for tax increases but not for uneven tax payments; housekeeping is inversely associated with support for higher and more progressive taxation. In models 3a and 3b, country-level factors were included.Footnote 13

Hypotheses 2a and 2b predicted that high-income taxpayers are less willing to support taxation in the context of high and progressive tax policy. To test these hypotheses, the interaction terms between income status and tax policy indices were added in models 4a and 4b. For tax level attitudes (Table 1), the interaction between income status and tax level was negative (β = − .116) and significant (p < .05). For tax progressivity attitudes (Table 2), the interaction effect was negative (β = −.111) but did not reach statistical significance (z = 1.43). In models 5a and 5b that include the interaction terms between income and macro-level controls, the interaction effects of tax level remained negative (β = −.188; −.180) and statistically significant (p < .001; .05), indicating that the marginal (downward) impact of higher income on tax attitudes is larger in high-tax societies. In particular, the random slope variance was markedly reduced from .053 (model 3a) to .028 (model 4a), suggesting that the interaction terms (income × tax policy indices) introduced in model 4a account for nearly half (47 %, [1 − (.028/.053)]) of the income slope variance.

On the other hand, the tax concentration hypothesis (Hypothesis 2b) was not supported. There was no significant interaction between income position and tax concentration, suggesting that attitudinal disparities between income groups are independent of the degree of tax concentration in each society. For robustness check, I estimated the same interaction models (models 5a and 5b) using the effectiveness (inequality reduction) index for household taxes (OECD 2008; Wang and Caminada 2011) instead of the concentration coefficient of household taxes. The effectiveness index is defined as the distance between the Gini coefficient of before-tax earnings and that of after-tax earnings (i.e., inequality reduction by household taxes). This scale, which reflects the redistributive impact of household taxes, can be considered as an alternative proxy for progressive taxation (Kakwani 1977; Joumard et al. 2012). The results, however, showed that the interaction terms between income and the effectiveness index remained statistically insignificant (p > .10; not reported here).

To help interpret the substantive magnitude of the interaction effects, predicted probabilities were calculated using the parameter estimates from models 5a and 5b. The results are presented in Table 3. In the context of high-tax policy (52.5), the shift from the poor (10th percentile) to the rich (90th percentile) substantially decreases the probabilities of support for tax increases (−.225) and more progressive taxation (−.288), while in the context of low-tax policy (8.0) the effect of income on attitudes is less clear (−.047) or even works in the opposite direction (+.103). On the other hand, patterns of attitudinal gaps between income groups are similar across countries with different degrees of tax concentration (tax level attitudes: −.060 and −.083; tax progressivity attitudes: −.156 and −.207).

5 Discussion

Thus far, I have investigated how both demographic and contextual circumstances are associated with taxpayers’ policy preferences, with a particular focus on the interaction mechanisms between income status and policy contexts. The theoretical model tested was based on the following two propositions: (1) taxpayers’ preferences are primarily motivated by self-interest; and (2) taxpayers situate their self-interest within a given policy context. With regard to the former proposition, income status was found to be a strong predictor of tax attitudes, while the latter proposition obtained mixed results. On the one hand, I found that the direction and magnitude of the effects of income status are conditional upon the absolute amount of household taxes. While higher income reduces the likelihood of pro-tax orientations in high-tax societies, attitudinal differences among income groups are less marked in low-tax societies. On the other hand, however, no interaction effect was detected between income position and concentrated taxation.

Before discussing the implications of these findings, several caveats should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits any causal inferences regarding the direction of the observed associations. In particular, the question remains whether tax policies cause public opinion, or the other way around—i.e., public opinion shapes tax policies. In this respect, it is important to note that the current study does not attempt to examine how macro-level features (i.e., tax policies) directly affect individual-level attitudes, but instead focuses on how policy features condition the effect of income status on outcome attitudes (Hypotheses 2a and 2b). Second, the relationship between the complexity of a tax system and mass attitudes is not fully recognised. The interaction theory examined in this study suggests that taxpayers behave differently depending on the tax system in which they are embedded. This notion presupposes that individuals are adequately aware of the implications that a tax structure may have on their personal economic lives. In countries with complex tax legislation, the general public is expected to find it more difficult to acquire sufficient knowledge about the system, which may distort or bias self-interested calculations and subsequent tax preferences.Footnote 14 Third, the present study could benefit from a more nuanced behavioural model that incorporates the distinction between labour income (e.g., wages) and capital income (e.g., rents, dividends, and interest) into its theoretical framework. A report by the OECD (2008) suggests that countries have different tax structures and different levels of distributional inequality for labour and capital incomes. Taking these additional macro-contexts into account would allow us, for example, to examine the potential interplay between self-interest and capital income taxation.

Several implications and directions for future research can be drawn. First, the empirical findings in this study strongly support an institutionalist understanding of tax behaviour. Based on the notion that previously enacted policies produce ‘feedback effects’ on mass publics (Pierson 1993; Mettler and Soss 2004; Soss and Schram 2007), the present study hypothesised that the effect of income status on tax attitudes differs systematically across policy contexts. The results indeed suggest that attitudinal cleavages among income groups become more salient in high-tax societies (Hypothesis 2a). This implies that further tax increases may result in polarised tax preferences between the rich and the poor. In contrast, the other policy feature—tax concentration—seems to have little to do with popular perceptions. Drawing on the work of Korpi and Palme (1998), I hypothesised that in countries where taxes are ‘unequally’ distributed across different income groups, high-income earners hold stronger anti-tax sentiments because they are disproportionately exposed to tax costs (Hypothesis 2b). This prediction, however, was not supported by the survey data. The relationship between income and policy attitudes was not conditioned by the disproportionate distribution of tax burden. Thus, it could be concluded that ‘tax targeting’ does not have an interaction effect on the income-attitude linkage. However, the insignificant result may be attributable to the limited variation in the tax concentration index coming from a relatively small number of country cases and/or to the choice of the proxy variable employed to measure the construct (i.e., the concentration coefficient of household taxes). A more theoretical explanation of this result is that relative to tax level, concentrated taxation might be invisible or ‘hidden’ to ordinary citizens. If taxpayers are not aware of, or do not notice, the degree of tax concentration in their country, then it is hardly surprising that they ‘fail to react’ to the policy context. Another theoretical interpretation is that taxpayers may perceive the burden (cost) associated with taxation policies to be high in comparison with the expected benefits they receive. If this is the case, the disproportionate distribution of tax costs must be evaluated relative to that of transfer benefits. An integrated model incorporating both transfer benefits and tax costs may provide a more accurate account of how taxpayers contextualise their self-interest within a given policy context.

Notes

Of course, this is not to say that tax resistance will be absent in low-tax societies nor that tax level is the only cause of a protest movement. For instance, Martin (2008) argues that in the United States not every tax increase (i.e., the absolute amount of taxes) causes a tax revolt but that American taxpayers react angrily when they understand that a policy change undermines their informal tax privileges—i.e., specific tax exemptions not codified in law but are part of the tax system in practice—that provide them with a shelter from potential market anomalies.

This is not to say that there is no relationship between indirect tax policies and mass opinion.

Their work differs from the present study in that they assessed ‘social class’ using the International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) and did not associate income status with tax preferences (as argued earlier, it is income position that directly determines one’s actual and perceived tax burden and thus contributes to the formation of tax policy opinion), and in that they employed different measures of ‘tax policy schemes’ and ‘tax attitudes’.

The included countries are Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Slovak Republic (available from a separate data file), South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States.

Respondents aged 17 or younger were omitted.

One disadvantage of using this question is that the word ‘taxes’ covers a wide variety of taxes including indirect taxes (i.e., taxes on goods and services). Ideally, ‘taxes’ should only refer to direct income taxes because the present study argues that tax attitudes are jointly motivated by income status and direct income taxes.

‘Much too high’ and ‘too high’ were coded as −1, while ‘much too low’ and ‘too low’ were coded as +1.

For several countries, household income is offered on an annual, not a monthly, basis. To gain comparability across countries, annual incomes were divided by 12.

Household size ranges from 1 to 34 (mean = 2.7; SD 1.4). To reduce the influence of outlying values, respondents with 9 or more household members (0.2 %) were recoded as 8.

Respondents with zero income (0.3 %), that is, Ln(0), were dropped from the data.

Subjective (explanatory) variables such as political trust, political ideology, and self-rated social class were omitted from the analysis to avoid potential endogeneity issues.

The four country-level variables were standardised prior to analysis for ease of interpretation.

In this regard, Edlund (2003) notes that “[t]he comparatively low degree of complexity and high degree of standardization, i.e. the high degree of system transparency, is likely to advance public understanding of social and tax policy” (p. 151, italics in original). Moreover, it could be argued that the better educated are more likely to accurately assess the impact of particular tax structures on their households.

References

Andreß, H.-J., & Heien, T. (2001). Four worlds of welfare state attitudes? A comparison of Germany, Norway, and the United States. European Sociological Review, 17(4), 337–356.

Ariely, G. (2011). Why people (dis)like the public service: Citizen perception of the public service and the NPM doctrine. Politics & Policy, 39(6), 997–1019.

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2001). Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: Does the type really matter? Acta Sociologica, 44(4), 283–299.

Barnes, L. (2015). The size and shape of government: Preferences over redistributive tax policy. Socio-Economic Review, 13(1), 55–78.

Bartels, L. M. (2005). Homer gets a tax cut: Inequality and public policy in the American mind. Perspectives on Politics, 3(1), 15–31.

Bean, C., & Papadakis, E. (1998). A comparison of mass attitudes towards the welfare state in different institutional regimes, 1985–1990. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 10(3), 211–236.

Beck, P. A., & Dye, T. (1982). Sources of public opinion on taxes: The Florida case. Journal of Politics, 44(1), 172–182.

Beck, P. A., Rainey, H. G., & Traut, C. (1990). Disadvantage, disaffection, and race as divergent bases for citizen fiscal policy preferences. Journal of Politics, 52(1), 71–93.

Bowler, S., & Donovan, T. (1995). Popular responsiveness to taxation. Political Research Quarterly, 48(1), 79–99.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2006). Why do welfare states persist? Journal of Politics, 68(4), 816–827.

Buhmann, B., Rainwater, L., Schmaus, G., & Smeeding, T. M. (1988). Equivalence scales, well-being, inequality, and poverty: Sensitivity estimates across ten countries using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) database. Review of Income and Wealth, 34(2), 115–142.

Coughlin, R. M. (1980). Ideology, public opinion and welfare policy: Attitudes toward taxes and spending in industrialized societies. Berkeley: Institute of International Studies, University of California.

Easton, D. (1953). The political system: An inquiry into the state of political science. New York: Knopf.

Edlund, J. (1999a). Trust in government and welfare regimes: Attitudes to redistribution and financial cheating in the USA and Norway. European Journal of Political Research, 35(3), 341–370.

Edlund, J. (1999b). Attitudes towards tax reform and progressive taxation: Sweden 1991–96. Acta Sociologica, 42(4), 337–355.

Edlund, J. (2000). Public attitudes towards taxation: Sweden 1981–1997. Scandinavian Political Studies, 23(1), 37–65.

Edlund, J. (2003). Attitudes towards taxation: Ignorant and incoherent? Scandinavian Political Studies, 26(2), 145–167.

Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1992). The constant flux: Study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Finseraas, H. (2009). Income inequality and demand for redistribution: A multilevel analysis of European public opinion. Scandinavian Political Studies, 32(1), 94–119.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1–56.

Gelissen, J. (2000). Popular support for institutionalised solidarity: A comparison between European welfare states. International Journal of Social Welfare, 9(4), 285–300.

Goldstein, H. (1995). Multilevel statistical models. London: Edward Arnold.

Hasenfeld, Y., & Rafferty, J. A. (1989). The determinants of public attitudes toward the welfare state. Social Forces, 67(4), 1027–1048.

Hibbs, D. A., & Madsen, H. J. (1981). Public reactions to the growth of taxation and government expenditure. World Politics, 33(3), 413–435.

Hout, M. (2004). Getting the most out of the GSS income measures. GSS Methodological Report No. 101. Chicago, NORC.

IMF. (2005). World economic outlook database (September). Washington, DC: IMF.

Jæger, M. M. (2006). What make people support public responsibility for welfare provision: Self-interest or political ideology? A longitudinal approach. Acta Sociologica, 49(3), 321–338.

Jaime-Castillo, A. M., & Sáez-Lozano, J. L. (2014). Preferences for tax schemes in OECD countries, self-interest and ideology. International Political Science Review, online first (8 July 2014).

Joumard, I., Pisu, M., & Bloch, D. (2012). Tackling income inequality: The role of taxes and transfers. OECD Journal: Economic Studies, 2(1), 37–70.

Kakwani, N. C. (1977). Measurement of tax progressivity: An international comparison. Economic Journal, 87(345), 71–80.

Korpi, W. (1983). The democratic class struggle. London: Routledge Kegan Paul.

Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. American Sociological Review, 63(5), 661–687.

Kreft, I., & De Leeuw, J. (1998). Introducing multilevel modeling. London: Sage.

Larsen, C. A. (2007). The institutional logic of welfare attitudes: How welfare regimes influence public support. Comparative Political Studies, 41(2), 145–168.

Linos, K., & West, M. (2003). Self-interest, social beliefs, and attitudes to redistribution: Re-addressing the issue of cross-national variation. European Sociological Review, 19(4), 393–409.

Lowery, D., & Sigelman, L. (1981). Understanding the tax revolt: Eight explanations. American Political Science Review, 75(4), 963–974.

Martin, I. W. (2008). The permanent tax revolt: How the property tax transformed American politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

Mettler, S., & Soss, J. (2004). The consequences of public policy for democratic citizenship: Bridging policy studies and mass politics. Perspectives on Politics, 2(1), 55–73.

OECD. (2005). Income distribution database (IDD). Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2006). National accounts statistics. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2008). Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2012). Eurostat-OECD methodological manual on purchasing power parities. Eurostat Methodological Working Papers 2012 Edition. Paris, OECD.

Papadakis, E., & Bean, C. (1993). Popular support for the welfare state: A comparison between institutional regimes. Journal of Public Policy, 13(3), 227–254.

Pierson, P. (1993). When effect becomes cause: Policy feedback and political change. World Politics, 45(4), 595–628.

Rasbash, J., Steele, F., Browne, W. J., & Goldstein, H. (2014). A user’s guide to MLwiN, v2.31. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol.

Roberts, K. W. S. (1977). Voting over income tax schedules. Journal of Public Economics, 8(3), 329–340.

Roberts, M. L., & Hite, P. A. (1994). Progressive taxation, fairness, and compliance. Law & Policy, 16(1), 27–48.

Roberts, M. L., Hite, P. A., & Bradley, C. F. (1994). Understanding attitudes toward progressive taxation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 58(2), 165–190.

Romer, T. (1975). Individual welfare, majority voting and the properties of a linear income tax. Journal of Public Economics, 4(2), 163–185.

Rothstein, B. (1998). Just institutions matter: The moral and political logic of the universal welfare state. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2002). The universal welfare state as a social dilemma. Rationality and Society, 13(2), 213–233.

Rudolph, T. J. (2009). Political trust, ideology, and public support for tax cuts. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(1), 144–158.

Rueda, D. (2014). Food comes first, then morals: Redistribution preferences, altruism and group heterogeneity in Western Europe. CAGE Working Paper Series No. 200. Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy (CAGE).

Rueda, D., Segmueller, D., & Idema, T. (2014). The effects of income expectations on redistribution preferences in Western Europe. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA).

Rueda, D., & Stegmueller, D. (2015). The externalities of inequality: Fear of crime and preferences for redistribution in Western Europe. American Journal of Political Science, online first (21 August 2015).

Schmidt-Catran, A. W. (2014). Economic inequality and public demand for redistribution: Combining cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. Socio-Economic Review, online first (3 October 2014).

Sears, D. O., & Citrin, J. (1982). Tax revolt: Something for nothing in California. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sears, D. O., & Funk, C. L. (1990). The limited effect of economic self-interest on the political attitudes of the mass public. Journal of Behavioral Economics, 19(3), 247–271.

Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers: The political origins of social policy in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage.

Soss, J., & Schram, S. F. (2007). A public transformed? Welfare reform as policy feedback. American Political Science Review, 101(1), 111–127.

Sumino, T. (2014). Escaping the curse of economic self-interest: An individual-level analysis of public support for the welfare state in Japan. Journal of Social Policy, 43(1), 109–133.

Svallfors, S. (1997). Worlds of welfare and attitudes to redistribution: A comparison of eight Western nations. European Sociological Review, 13(3), 283–304.

Svallfors, S. (2003). Welfare regimes and welfare opinions: A comparison of eight Western countries. Social Indicators Research, 64(3), 495–520.

Svallfors, S. (2004). Class, attitudes and the welfare state: Sweden in comparative perspective. Social Policy and Administration, 38(2), 119–138.

Wang, C., & Caminada, K. (2011). Leiden LIS budget incidence fiscal redistribution dataset. http://www.law.leidenuniv.nl/org/fisceco/economie/hervormingsz/datawelfarestate.html. Accessed 16 July 2015.

Wilensky, H. (1975). The welfare state and equality: Structure and ideological roots of public expenditures. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wilensky, H. (1976). The ‘new corporatism’, centralization, and the welfare state. London: Sage.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Professors Stephen D Fisher and Tamas David-Barrett for stimulating discussions and encouragements throughout the research period. I also wish to thank three anonymous referees for their thought-provoking comments on an earlier version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sumino, T. Level or Concentration? A Cross-national Analysis of Public Attitudes Towards Taxation Policies. Soc Indic Res 129, 1115–1134 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1169-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1169-1