Abstract

In-work poverty is becoming an important category of poverty in many developed economies, where labour polarization and income disparity have trapped in poverty a growing number of people, particularly low-skilled workers, despite their active participation in the labour force. In Hong Kong, the government has acknowledged the seriousness of the problem and has made the working poor one of the main target groups of its poverty reduction strategy. Existing studies have identified various individual, employment and household factors that contribute to the poverty risk of households with working members. These factors operate through three mechanisms: low earnings, the lack of other earners in the household and high living costs related to the care of dependent members in the household. The relative importance of these mechanisms varies according to the socio-economic contexts of different societies. In order to formulate an effective poverty reduction policy, it is necessary to understand which mechanisms lead to in-work poverty in a local context. In this paper, we sought to identify the characteristics of households affected by in-work poverty, and the mechanisms that lead to such poverty, by analysing a data sample from the 2011 Hong Kong Population Census. The results show that low-paid work and the absence of a second earner in the household are the two main mechanisms that lead to in-work poverty in Hong Kong. The results also show that the risk of in-work poverty differs for high- and low-skilled labour. We propose that the government should strengthen the poverty reduction strategy by countering the income disparity in the labour market and adopting an integrated approach in the formulation of policy to improve the labour participation of working-poor households.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Employment is often regarded as an important means of escaping poverty. However, this assumption has come under increasing scrutiny as more and more workers, especially low-skilled workers, find themselves unable to provide a reasonable standard of living for themselves and their families, let alone to use employment to climb up the social ladder (Fleury and Fortin 2006). Compared with other categories of households in poverty, the situation regarding the number of working-poor households is surprisingly serious. In the United States, the percentage of working-poor households was 11.0 % in 2000 (Brady et al. 2010), which was more than twice that of single-mother households living in poverty (4.1 %) and over four times that of households without working members (2.6 %). The situation has been receiving increasing attention in recent years, especially since the 2008 financial crisis, when the world witnessed top executives in the financial sector receiving lavish bonuses while the lower strata of the working population were left devastated by the crisis those executives had created. Many have argued that the main reason why workers find their economic outlook deteriorating is that the benefits of economic growth are not fairly distributed and the current economic system in many developed societies privileges the rich at the expense of the poor (Stiglitz 2012; Piketty 2014).

Given that social inequality often underlies in-work poverty, the problem is not limited to poverty itself but rather has wider implications in other social domains. For instance, in-work poverty creates a disincentive to engage in work, thus increasing labour wastage and the burden of social welfare expenditure. When people do not believe in the prospect of escaping poverty through work or that working is the way to achieve a higher standard of living, this creates more demands on social welfare from individuals whose economic well-being could have been met by productive economic activities. This is particularly the case if there are no stringent requirements for receiving unemployment benefits or if the money received from a welfare programme is comparable to, if not better than, the remuneration received from employment (European Commission 2012). In-work poverty also undermines aspirations of upwards social mobility. When the chance of social advancement through labour participation is diminished, trust in the fairness of society will also be undermined. The hidden social costs of the widespread perception of unfairness in society will damage the social fabric that is essential to sustaining stability within society (Cooke and Lawton 2008).

As an open economy, Hong Kong has a problem of in-work poverty similar to that in other developed economies. As a way to gauge the extent of poverty in Hong Kong, on 28 September 2013 the government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) announced its first official poverty line, which is set at half the median monthly household income before tax and welfare transfers and adjusted for household size (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2013b). Based on this poverty threshold, the poverty rate in 2012 was 19.6 %; about 1.31 million people were living in poverty. The number of people classified as working poor was 702,100, which accounted for slightly more than half (53.5 %) of the whole population living below the poverty line (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2013a).

In order to improve the living standard of low-paid workers, the government introduced the statutory minimum wage on 1 May 2011; it was initially set at HK$28 per hour and subsequently raised to HK$32.50. The government’s commitment to help the working-poor households was reiterated when the Chief Executive announced in his second policy address, in February 2014, the introduction of a Low-income Working Family Allowance to alleviate the heavy financial burden of working-poor families, especially those with children, and to encourage them to remain in the labour market (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2014a). However, given the emerging importance and policy significance of the issue, the study of in-work poverty in Hong Kong is very limited (Lui 2013). In order to formulate better policy responses, the main objectives of this study are (1) to construct a profile of the working-poor households in Hong Kong and (2) to determine the main mechanisms that lead to their poverty through an analysis of the 2011 Hong Kong Population Census data.

1.1 Factors and Mechanisms Contributing to In-Work Poverty

Past research has identified three mechanisms through which a person would become working poor: (1) low earnings, (2) low labour participation within the household and (3) high costs associated with the care of dependents in the household (Goerne 2011; Crettaz and Bonoli 2011). These mechanisms point to the availability of resources in a household (the earnings and number of earners) as well as the needs of that household (in terms of the number of children and elderly dependents). First of all, poverty among the working population may simply be the result of low earnings (Nolan and Marx 2000; Marlier and Ponthieux 2000; Cooke and Lawton 2008). The level of earnings is associated with a number of individual-level and employment-related factors. For instance, low educational attainment is often associated with low employment status and low income (Julian and Kominski 2011). The probability of having a low-paid job as a result of having poor social and cultural capital is often higher for migrants than for their native counterparts (Lam and Liu 1998; Liu et al. 2004; Chou et al. 2014). In addition to having a low educational level, migrants are also more likely to receive poor remuneration because of discrimination (Lam and Liu 2002a, b). Employment discrimination also exists across gender; it is still a general phenomenon in many countries that female workers find themselves in a disadvantaged position in the labour market (Darity and Mason 1998; Davies and Joshi 1998). Low earnings are also associated with employment-related variables, such as the specific occupation, whether the occupation is full- or part-time, whether it is on a permanent or temporary contract, and whether an individual is self-employed (Peña-Casas and Latta 2004; European Commission 2012; Lohmann and Andreβ 2008).

Low earnings are attributed to macro-level factors—such as types of welfare regime and labour market institutions (Lohmann 2009)—as well as to individual and employment-related variables. From the macro-level perspective, the increased connectedness of the global economy and the advancement of technology have put pressures on the wages of low-skilled workers. For instance, the international outsourcing strategy adopted by multinational corporations (to relocate jobs to regions with relatively low labour costs, both in terms of wages and labour regulations) has reduced the bargaining power and wages of low-skilled workers (Geishecker and Görg 2008). The negative effects on wages of these socio-economic developments are mostly felt in liberal welfare regimes where wages are more flexible and the institutional protection of labour rights (such as to collective bargaining or to minimum wages) is inadequate (Dafermos and Papatheodorou 2012; Esping-Andersen 1990; Esping-Andersen and Regini 2000).

In a liberal welfare regime, policymakers are often reluctant to introduce legislation to protect workers’ pay levels because allowing wage levels to be adjusted downward by market forces is considered necessary to reduce unemployment. Although the negative relationship between unemployment and low-wage employment has been refuted by recent empirical research (Grimshaw 2011), this idea is still held by many policymakers and has been used by business interest groups to resist minimum wage legislation. Similarly, a desire to increase the competitiveness of an economy and the efficiency of its labour market leads policymakers to dismantle existing labour protection. Liberal welfare regimes generally allow a high level of wage flexibility and disparity to increase employment opportunities for all. Justified by trickle-down economics, wage disparity is very often seen as a necessary evil to be tolerated as a means of sustaining economic growth, which is a prerequisite for poverty reduction—as the economy grows, everyone in it will benefit, and the absolute gain for those in the lower strata of society will be higher than the relative gain they would get through redistribution. Thus, income disparity and inequality is tolerated in order to create more economic benefits for everybody.

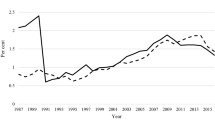

Although having a low-paid job is an important cause of in-work poverty, it is not the sole determinant, as other household characteristics may affect the economic well-being of a household (European Commission 2012). For instance, an individual may live below the poverty line because his/her partner and/or other working age members of the same household earn nothing (Burkhauser et al. 1995; Maitre et al. 2003; Buchel et al. 2003). This is particularly the case with single parents who have dependent children and who struggle to balance childcare and employment (Citizens Advice Bureau 2008; Millar and Ridge 2009; Marsh 2001). The risk of in-work poverty is reduced if there are other sources of income, most notably the earnings of other household members and social welfare transfers (Marx and Verbist 1998; Strengmann-Kahn 2003; Andress and Lohmann 2008; Peña-Casas and Latta 2004; Swiss Federal Statistical Office 2008). Thus, the number of earners within a household is also related to in-work poverty. Finally, in-work poverty may be the result of the high living costs associated with having dependent children and elderly in a household. Past studies have shown that a single-earner household with high living costs resulting from having many dependents is the typical household that experiences in-work poverty (Goerne 2011; Brady et al. 2010). Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram that illustrates the relationship between these macro- and micro-level variables and the three mechanisms that lead to in-work poverty.

This paper will focus on analyzing the micro-level variables in order to determine the relative importance of the three mechanisms and construct a profile of the working poor in Hong Kong. Although the focus of this paper is on the influence of the micro-level variables, it should be remembered that macro-level variables (such as types of welfare regime and labour market institutions) also play a salient role in explaining the condition of the working poor. The next section will briefly explain the labour market’s institutions and the welfare regime in Hong Kong.

1.2 Institutional Context of In-Work Poverty in Hong Kong

Hong Kong has a typical liberal welfare regime, with limited institutional protection for workers. The government relies mainly on economic growth and trickle-down economics for its poverty reduction strategy. It maintains a low level of welfare spending while emphasizing welfare provision from private sources. According to Wong et al. (2010), the government uses a number of strategies to garner public support for limited public spending on the provision of social welfare; these strategies include emphasizing the constitutional requirement of financial prudence under the Basic Law, reinforcing the belief in the fragility and uncertainty of Hong Kong’s economic prosperity, differential provision and retrenchment of welfare to target resources on the groups most in need, a selective response to the public’s welfare expectations, and the promotion of the family as the main source of welfare support in society.

Hong Kong also maintains a flexible labour market with limited institutional protection for wages. For instance, shortly after the handover of Hong Kong’s sovereignty in 1997 the Hong Kong SAR government repealed and amended the labour ordinances that provided the right to collective bargaining (Committee on Freedom of Association 1999). The flexibility of the Hong Kong labour market has diminished only slightly since the introduction of the minimum wage in 2011.

In Hong Kong, there has been growing disparity between the wages of highly skilled and low-skilled workers ever since the bulk of Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry (which contributed to Hong Kong’s economic boom in the 1970s and 1980s) was relocated north, across the border, to Guangdong Province. Replacing this industry is the booming financial industry, which is now one of the main pillars of Hong Kong’s economy. The hollowing out of the manufacturing industry forced the surplus labour to compete with other low-skilled workers for unskilled and semi-skilled jobs. Moreover, the continued growth of the migrant population (most of the migrants have entered Hong Kong by obtaining one-way permits allocated in a non-merit based quota scheme) has further increased the downward pressure on wages in the low-skilled segment of the labour market (Lee and Wong 2004; Chiu and Lui 2004; Lee et al. 2007; Lam and Liu 2011).

Since the relative importance of the three mechanisms varies in different societies, it is important to understand in-work poverty in its local context (Goerne 2011; Crettaz and Bonoli 2011). By analyzing the data from the 2011 Hong Kong Population Census, we sought to identify a profile of the working-poor households in Hong Kong and to discover which of the three mechanisms are important in the Hong Kong context. The results have important policy implications for the government’s anti-poverty strategy. For instance, researchers in other countries have questioned the effectiveness of a minimum wage as a measure for reducing the number of working-poor households because many of these households do not contain low-wage workers (Formby et al. 2010; Sabia and Nielsen 2012). As such, our own findings on this and other issues will shed light on the current policy debates over the question of how best to help the working poor in Hong Kong.

2 Methodology

2.1 Sample

The data used in this study were taken from a 5 % sample of the 2011 Hong Kong Population Census, which provided cross-sectional data on in-work poverty in Hong Kong. The 2011 Population Census was conducted by the Census and Statistics Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government between June and August 2011. In the Population Census, basic information (such as the age and gender of individuals) was collected from about 90 % of all the households in Hong Kong; 10 % of the households were randomly selected to complete a long questionnaire in which a wide range of the socio-economic characteristics of individual household members was collected. We used the 5 % sample because this was the largest proportion of the sample available for purchase from the Census and Statistics Department. In the Census, workers were defined as those aged 16 and above who were engaged in paid employment during the week prior to the data collection. In our sample, a total of 180,302 workers fitted this definition.

The 2011 Population Census data included information on basic demographic and economic indicators (e.g. age, gender, educational level and employment); household characteristics (e.g. household income and household size); and migration-related attributes (e.g. place of birth, duration of residence, and the usual language spoken at home as well as other languages spoken). Regarding employment, the respondents were asked to provide information concerning the following variables: whether they had a low-paid primary job (i.e. one providing a wage less than half the median income); whether they had a secondary job or other sources of income (e.g. government welfare benefits or financial assistance from family members); whether they were self-employed; and their occupation. In addition, the Census data provided detailed information on the following household characteristics: the household composition (the categories being ‘two adults only’, ‘single and no child’, ‘single parent with a child or children’, ‘two adults and one child’, ‘two adults and two children’, ‘two adults and more than two children’ and ‘other’); the labour intensity (i.e. the ratio of non-working members to working members); and the number of earners.

2.2 Analytical Strategy

In this study, a person was considered to be in in-work poverty if he/she was engaged in paid employment during the week prior to the data collection and was living in a household whose income fell below the poverty line, defined as half the median household income adjusted for household size through the square root formula. This measure of poverty was adopted because it is the official definition of poverty in Hong Kong. Based on the Census data, the poverty threshold in this study was HK$ 6062.20 per month. A dependent variable that indicated poverty status was thus created (0 = not living in poverty; 1 = living in poverty) for our whole 5 % Census sample (121,723 households). In this sample, we found that 28,246 households (23.2 % of the total) were poor. After establishing the poverty household, we then selected all of the workers in our sample (n = 180,302) and found that, of the total working population, 13,101 (7.3 %) were living in poverty.

The empirical analysis then proceeded in two stages. In the first stage, the workers who were poor and non-poor were compared in terms of their individual-level variables, employment-related variables and household-level variables using bivariate analysis. The second stage of the analysis used logistic regression models (with robust standard errors that adjusted for clustering within households) to estimate the likelihood of in-work poverty in families belonging to the working population.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Profile of the Working Poor in Hong Kong

Table 1 provides a comparison between the poor and non-poor workers in our sample with respect to the individual-level variables, the employment-related variables and the household-level variables. Compared with the non-poor workers, poor workers were more likely to be older, male, immigrants and able to speak Cantonese; they were more likely to have had no university education and to be unable to speak English. Only approximately 5 % of the poor workers in our sample were university graduates, while about one quarter of the non-poor workers had had a university education. More than 55 % of the poor workers were immigrants, while only slightly more than one-third (35 %) of the non-poor workers were born outside Hong Kong. There were also significant differences between the poor and the non-poor workers in all of the household characteristics we evaluated, including the household composition and the number of earners. In particular, the poor workers were more likely than the non-poor workers to be single parents or to live in a single-earner household.

In terms of employment, more of the primary occupations of the poor workers were low-paid jobs. Specifically, about 62 % of the poor workers were engaged in a low-paid job; this compared with only 22 % of the non-poor workers. In regard to the other employment-related variables, the poor workers were less likely than the non-poor ones to have a secondary job or other sources of income. We also noticed that the percentage of the poor workers who were self-employed was twice that of those who were not poor. This is consistent with earlier research that found that a high percentage of the working poor were self-employed (Fleury and Fortin 2006). The high incidence of self-employed working poor in Hong Kong is also the result of forced self-employment following the introduction of the Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) scheme in 2000. Under the MPF scheme, both employers and employees are required by law to make regular contributions to the employees’ retirement funds. However, to avoid having to pay the employer’s contribution, unscrupulous employers often force their employees (mostly low-skilled contract staff) to reclassify themselves as self-employed (Legislative Council 2009). In addition, there were significant differences between the poor and the non-poor workers in terms of their occupations and the industries they were working in. For instance, the non-poor workers were more likely than the poor workers to work in finance, insurance, real estate, and business services, and to assume managerial and professional positions; the poor workers, however, were mostly concentrated in occupations such as machine operators, assemblers and other elementary occupations.

3.2 Factors and Mechanisms that Contribute to In-Work Poverty in Hong Kong

Using the logistic regression model, we examined the relative importance of the three mechanisms—namely, low earnings, low labour participation and high costs related to the care of dependents—that potentially lead to in-work poverty in Hong Kong. As can be seen in Table 2, households with only one earner have a much higher risk of in-work poverty than those with two or more earners. Existing studies have already documented the poverty risk associated with single-parent households (Ambert 2006; Chzhen and Bradshaw 2012; Cheung 2015). As regards the married couples, non-poor households tended to have two or more earners, whereas poor households usually had only one earner. Another mechanism that is significantly associated with the risk of in-work poverty is that of low earnings; this finding corresponds with our profile of the working poor in Hong Kong. The demographic features of the working poor had characteristics similar to those of groups that are in general more prone to have a low income, including the elderly, those without a university education, single parents and immigrants. Compared with those of the other two mechanisms, the odds ratios for being working poor were not high for households having dependents: for households with one child the odds ratio was 1.44; for households with two children or more it was 1.83. The same general result was true for households having elderly dependents.

In the course of our analysis of the three mechanisms we described, we also found that the risk of becoming working poor differs across occupations. The workers who engaged in elementary occupations and those who were employed as service workers and shop sales workers, agricultural and fishery workers, or plant and machine operators had a much greater risk of being poor than those who were professionals, managers and administrators. This is probably the result of the wage disparity between highly skilled and low-skilled workers in Hong Kong, one that is common in liberal welfare regime. As shown in a recent government economic report, there is a gap between the rate of the increases in the pay of low-skilled workers and highly skilled workers (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2014b). For instance, miscellaneous non-production workers and low-skilled service workers have seen their nominal wages increase by 7.1 and 5.8 %, respectively, following the upward adjustment of the statutory minimum wage to HK$30 per hour in 2013; however, the gap between the rate of the pay increases of these workers and that of professionals and business service workers continues to widen, as the latter saw their nominal wages increase by 8.1 % in the same year (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2014b). This, though, is hardly surprising, given the economic and social polarization that Hong Kong has experienced in recent decades (Lee et al. 2007).

In addition to examining the individual mechanisms, we wished to know whether the risk of in-work poverty that is associated with low earnings was affected by the other two mechanisms. Table 3 shows the results of the three logistic models we used to compare the interaction effects among the three mechanisms. Model 3 shows the odds ratio of being working poor using a number of variables and mechanisms without considering any interaction effects. Model 4a shows the odds ratio of being working poor after taking into account the interaction effects between having a low-paid job and the number of dependents in the household. In Model 4b, we further examined the interaction effects between having a low-paid job and the number of earners in the household. The interaction terms are shown in the lower portion of these models.

The results show that the combined odds ratio of being working poor for a household having a low-paid job and one dependent child, without taking into account the interaction effects, was 21.79 (found by multiplying the odds ratio of ‘low-paid primary job’ and of ‘one child’ in Model 3, i.e. 15.13 × 1.44). However, when taking the interaction effects into account, the combined odds ratio of being working poor became 26.23 (by multiplying the odds ratios of ‘low-paid primary job’ and ‘one child’ and the interaction terms ‘low-paid and one child’ in Model 4a, i.e. 24.09 × 1.98 × 0.55). The odds ratio of being working poor was 20 % higher when the interaction effect was considered. Similarly, the combined odds ratio of being working poor for a household having a low-paid job and one elderly dependent was 21.07 (24.09 × 1.25 × 0.7 in Model 4a) when the interaction effect was considered; this was about 32 % higher than the odds ratio of being working poor when the interaction effect was not considered (15.88). Model 4b shows that there was no significant interaction between having a low-paid job and the number of earners in the household.

3.3 Policy Implications

The results of our analyses show that low earnings and having only one earner in the household are the two main mechanisms that cause in-work poverty in Hong Kong. Low earnings and the income disparity between highly skilled and low-skilled workers are intertwined with each other. Our analyses also show that although the risk of being working poor as a result of the high cost of living associated with having elderly dependents and children is relatively low, the presence of dependents in the household does have interaction effects with low earnings and results in a heightened risk of being working poor. These results have important implications for the strategy the government should adopt to tackle in-work poverty in Hong Kong.

Since the risk of in-work poverty associated with having children and elderly dependents is not high, policymakers should focus on policies that address the issue of low earnings—such as by setting an adequate statutory minimum wage—while not neglecting policies aimed at reducing the burden of households with dependent members. This is particularly pertinent, given that the public provision of childcare and elderly care services in Hong Kong is inadequate. For instance, public childcare services are normally provided to children under 3 years old; a typical daytime crèche in a government-aided centre usually costs around HK$4000 per month.Footnote 1 Such a level of cost has proved to be too high for low-income households that do not pass the poverty threshold of HK$6062.20 per month. In addition, limited geographical coverage of these childcare centres also restricts the access to these services. This being so, increasing the provision of affordable public childcare services in Hong Kong is needed to reduce the burden on working-poor families.

Expanding the public childcare services and making them affordable for working-poor families would also help to reduce the number of single-earner households, which is another important factor in in-work poverty. In Hong Kong, a substantial number of families are able to have dual-earners in the household because some of their childcare responsibilities have been delegated to foreign domestic helpers. As at 2011, there were 254,284 foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong (Census and Statistics Department 2012), the majority of whom were from South East Asian countries, such as the Philippines and Indonesia. Although most of these domestic helpers are recruited at the statutory Minimum Allowable Wage of HK$4010 per month, the cost is still not affordable for all households with childcare responsibilities. More affordable public childcare services would allow more working-poor families to take advantage of these services and increase their labour participation.

Finally, given that low earnings contribute significantly to in-work poverty, the government should strengthen that part of its poverty reduction strategy that is focused on countering low wages in the low-skilled sectors. The introduction of the minimum wage by the Hong Kong SAR government in 2011 and the subsequent raising of the minimum wage were moves in the right direction. However, this policy is insufficient on its own. As mentioned earlier, the minimum wage is unable to stop the widening gap in earnings between highly skilled and low-skilled workers. Furthermore, a measure such as this usually attracts greater resistance from representatives of the business sector, who often condemn it for interfering with the free market economy in Hong Kong. Alternatively, the government could address the structural cause of income inequality by targeting both the demand and supply sides of the labour market in Hong Kong (Marx and Verbist 2008). On the demand side, the government should diversify the existing economic structure to create more jobs for low-skilled workers. Following the global financial crisis in 2008, the government has acknowledged the need to diversify the economic structure. However, it has mainly focused on enhancing the strength of the economy and reducing the risks associated with over-reliance on the financial sector. Thus, all six sectors the government has promoted investment in (education services, medical services, testing and certification, environmental industries, innovation and technology, and cultural and creative industries) involve high-end service industries that require their workers to have a high skills and education level (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2010). The government should also consider using economic diversification as a means to promote industries that require a more diverse range of skill levels—particularly ones that require skills at the lower end of the spectrum—and to fill the gap left by the manufacturing industry. In terms of the labour supply, the government should reconsider the number of immigrants to be admitted into Hong Kong through the non-merit based one-way permit system, and consider other, merit-based schemes. In order to reduce the competition among low-skilled local workers, a focus should be placed on attracting more highly-skilled immigrants in order to mitigate the widening gap between the highly skilled and the low-skilled workforce in Hong Kong. This, however, would oblige the government to adopt an integrated approach to poverty reduction, one that requires close collaboration across different policy areas in order to maximize the effect of its poverty reduction strategy.

4 Conclusion

Like many other developed economies, Hong Kong is facing a growing problem of in-work poverty, and it is anticipated that the problem will persist and even worsen. Thus, it is necessary for the government to do more to target the needs of the working people whose income level falls below the poverty threshold. On the basis of an analysis of the 2011 Population Census data, we have identified two main mechanisms—namely, low income and poor labour participation—that lead to in-work poverty in Hong Kong. The results have important policy implications for the poverty reduction strategy adopted by the government. To date, most government policy initiatives have focused on addressing the low-income mechanism and have relied heavily on institutional means to raise the income level of the working poor, either through minimum wage legislation or welfare benefits (such as low-income subsidy). The easily measurable results on the poverty reduction provided by these policies—results the government has recently proudly announced by reporting the post-intervention poverty situation in Hong Kong (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2013a)—may boost the political standing of the government in the short run, but being content with these readily assessable results will lead to government complacency that is detrimental to any attempt to address the structural causes of the problem. Addressing the structural causes of income disparity and in-work poverty demands more concerted government efforts, in diverse policy areas (including population and immigration policy as well as the diversification of the economic structure), to alter the macro socio-economic variables. In addition, since labour participation is also an important mechanism that leads to in-work poverty in Hong Kong, the government should not be so focused on an income-based poverty reduction strategy as to neglect other policy initiatives (such as the provision of public childcare services) that could encourage higher labour participation by working-poor households. Further, the government should also pay more attention to alleviating the financial burdens on working-poor families that arise from the support of child and elderly dependents, as these may deepen the poverty of these families. In sum, the results of this study should prompt the government to adopt a more comprehensive approach to addressing the poverty of working-poor families and not to be content with short-term results at the expense of long-term policy outcomes.

Notes

Residential childcare centres and special childcare centres also provide childcare services for children under the age of six, but these services are for moderately and severely disabled children or for children who cannot be adequately cared for by their families because of behavioural, emotional or relationship problems or family crises. Details of the childcare centres in Hong Kong are available at http://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_family/sub_listofserv/id_childcares/.

References

Ambert, A. M. (2006). One parent families: Characteristics, causes, consequences, and issues. Ottawa: The Vanier Institute of the Family.

Andress, H. J., & Lohmann, H. (2008). The working poor in Europe: Employment, poverty and globalization. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Brady, D., Fullerton, A. S., & Cross, J. M. (2010). More than just nickels and dimes: A cross-national analysis of working poverty in affluent democracies. Social Problems, 57(4), 559–585.

Buchel, F., Mertens, A., & Orsini, K. (2003). Is mothers’ employment an effective means to fight family poverty? Empirical evidence from seven European countries. Luxembourg income study Working Papers Series no. 363. Luxembourg: LIS.

Burkhauser, R. V., Couch, K. A., & Glenn, A. J. (1995). Public policies for the working poor: The earned income tax credit versus minimum wage legislation. Discussion paper no. 1074-95. Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty.

Census and Statistics Department. (2012). 2011 Population census main report (Vol. 1). Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department.

Cheung, K. C. K. (2015). Child poverty in Hong Kong single-parent families. Child Indicators Research, 8(3), 517–536.

Chiu, S. W. K., & Lui, T. L. (2004). Testing the global city-social polarisation thesis: Hong Kong since the 1990s. Urban Studies, 41(10), 1863–1888.

Chou, K. L., Cheung, K. C. K., Lau, M. K. W., & Sin, T. C. H. (2014). Trends in child poverty in Hong Kong immigrant families. Social Indicators Research, 117(3), 811–825.

Chzhen, Y., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). Lone parents, poverty and policy in the European Union. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(5), 487–506.

Citizens Advice Bureau. (2008). Barriers to work: Lone parents and the challenges of working. London: Social Policy Department.

Committee on Freedom of Association. (1999). 311th Report of the Committee on freedom of association (Case no. 1942). Geneva: International Labour Organisation.

Cooke, G., & Lawton, K. (2008). Working out of poverty: a study of the low-paid and the ‘working poor’. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Crettaz, E., & Bonoli, G. (2011). Worlds of working poverty: National variations in mechanisms. In N. Fraser, R. Gutiérrez, & R. Peña-Casas (Eds.), Working poverty in Europe: A comparative approach (pp. 46–69). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dafermos, Y., & Papatheodorou, C. (2012). Working poor, labour market and social protection in the EU: A comparative perspective. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy, 6(1/2), 71–88.

Darity, J. W. A., & Mason, P. L. (1998). Evidence on discrimination in employment: Codes of color, codes of gender. The Journal of Economic Perspective, 12(2), 63–90.

Davies, H., & Joshi, H. (1998). Gender and income inequality in the UK 1968–1990: The feminization of earnings or of poverty. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 161(1), 33–61.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Regini, M. (Eds.). (2000). Why deregulate labour markets? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

European Commission. (2012). Employment and social developments in Europe 2011. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fleury, D., & Fortin, M. (2006). When working is not enough to escape poverty: An analysis of Canada’s working poor. Government of Canada.

Formby, J. P., Bishop, J. A., & Kim, H. (2010). What’s best at reducing poverty? An examination of the effectiveness of the 2007 minimum wage increase. Washington, DC: Employment Policies Institute.

Geishecker, I., & Görg, H. (2008). Winners and losers: A micro-level analysis of international outsourcing and wages. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 41(1), 243–270.

Goerne, A. (2011). A comparative analysis of in-work poverty in the European Union. In N. Fraser, R. Gutiérrez, & R. Peña-Casas (Eds.), Working poverty in Europe: A comparative approach (pp. 15–45). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (2010). 2009 Economic Background and 2010 Prospects. Hong Kong: Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (2013a). Hong Kong poverty situation report 2012. Hong Kong: Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (2013b). Poverty Line set for HK. http://www.news.gov.hk/en/categories/health/html/2013/09/20130927_191059.shtml.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (2014a). 2014 policy address by chief executive. Hong Kong: Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (2014b). First quarter economic reports. Hong Kong: Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Grimshaw, D. (2011). What do we know about low-wage work and low-wage workers? Analysing the definitions, patterns, causes and consequences in international perspective. Conditions of work and employment Series no. 28. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Julian, T., & Kominski, R. (2011). Education and synthetic work-life earnings estimates—American community survey reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (1998). Immigration, population heterogeneity, and earnings inequality in Hong Kong. Contemporary Economic Policy, 16(3), 265–276.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (2002a). Earnings divergence of immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(1), 86–104.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (2002b). Relative returns to skills and assimilation of immigrants in Hong Kong. Pacific Economic Review, 7(2), 229–243.

Lam, K. C., & Liu, P. W. (2011). Increasing dispersion of skills and rising earnings inequality. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39(1), 82–91.

Lee, K. M., & Wong, H. (2004). Marginalized workers in postindustrial Hong Kong. Journal of Comparative Asian Development, 3(2), 249–280.

Lee, K. M., Wong, H., & Law, K. Y. (2007). Social polarisation and poverty in the global city: The case of Hong Kong. China Report, 43(1), 1–30.

Legislative Council. (2009). Minutes of meeting (LC Paper no. CB(2)766/09-10). http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr09-10/english/panels/mp/minutes/mp20091119.pdf.

Liu, P. W., Zhang, J., & Chuen, C. S. (2004). Occupational segregation and wage differentials between natives and immigrants: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of Development Economics, 73(1), 395–413.

Lohmann, H. (2009). Welfare states, labour market institutions and the working poor: A comparative analysis of 20 European countries. European Sociological Review, 25(4), 489–504.

Lohmann, H., & Andreβ, H. J. (2008). Explaining in-work poverty within and across countries. In H. J. Andreβ & H. Lohmann (Eds.), The working poor in Europe: Employment, poverty and globalization. London: Edward Elgar.

Lui, H. K. (2013). Widening income distribution in post-handover Hong Kong. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Maitre, B., Whelan, C. T., & Nolan, B. (2003). Female partner’s income contribution to the household income in the European Union. Institute for Social Economic Research Working Papers 2003-43. Colchester: University of Essex.

Marlier, E., & Ponthieux, S. (2000). Low wage employees in EU countries. Statistics in focus, population and social conditions. Paper no. 11. Brussels: Eurostat.

Marsh, A. (2001). Helping British lone parents get and keep paid work. In J. Millar & K. Rowlingson (Eds.), Lone parents, employment and social policy (pp. 11–36). Bristol: Policy Press.

Marx, I., & Verbist, G. (1998). Low-paid work and poverty: a cross-country perspective. In S. Bazen, M. Gregory, W. Salverda (Eds.), Low-wage employment in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Marx, I., & Verbist, G. (2008). Combating in-work poverty in Europe: The policy options assessed. In H.-J. Andreß & H. Lohmann (Eds.), The working poor in Europe: Employment, poverty and globalization (pp. 273–292). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Millar, J., & Ridge, T. (2009). Relationships of care: Working lone mothers, their children and employment sustainability. Journal of Social Policy, 38, 103–121.

Nolan, B., & Marx, I. (2000). Low pay and household poverty. In M. Gregory (Ed.), Labour market inequalities: Problems and policies of low-wage employment in international perspective (pp. 100–199). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peña-Casas, R., & Latta, M. (2004). Working poor in the European Union. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sabia, J. J., & Nielsen, R. B. (2012). Can raising the minimum wage reduce poverty and hardship? New evidence from the survey of income and program participation. Washington: Employment Policies Institute.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2012). The price of inequality. London: Allen Lane.

Strengmann-Kahn, W. (2003). Working but poor, analysis and social policy consequences. New York: Campus.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office. (2008). Bas salaires et working poor en Suisse. Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

Wong, T. K. Y., Wan, P. S., & Law, K. W. K. (2010). The public’s changing perceptions of the condition of social welfare in Hong Kong: Lessons for social development. Social Policy and Administration, 44(5), 620–640.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Research Grant Council, Public Policy Research Funding Scheme (HKIEd 7005-PPR-12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, K.CK., Chou, KL. Working Poor in Hong Kong. Soc Indic Res 129, 317–335 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1104-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1104-5