Abstract

No empirical study has systematically investigated the role of power imbalance in sexual harassment and assault within the Chinese college and university context. Addressing this gap, we used search engines, news media, and social platforms to collect 93 publicly reported real-world cases of sexual harassment and assault by men against women at Chinese colleges and universities up until the end of 2023. We coded these cases for general characteristics, power status of perpetrators and victims, severity of sexual harassment and assault, and the post-incident behaviours of the victims, the perpetrators, and their colleges/universities. The results demonstrated that features of the power imbalance between perpetrators and victims were significantly associated with the behaviour of the victims, perpetrators, and colleges/universities after the assault. Specifically, the victim being single and in an isolated environment predicted greater severity of the sexual harassment and assault. The prominence of the perpetrator’s administrative position predicted a greater likelihood of the victim denouncing the perpetrator after graduation rather than before graduation. The lower the economic status of the victim’s family, the higher the ranking of the college/university that employed the perpetrator, and the perpetrator’s membership in the Communist Party of China (CPC) predicted a greater tendency for the perpetrator to deny allegations of harassment and assault. Finally, the perpetrator’s membership in the CPC and the higher the ranking of the college/university predicted the tendency for the college/university to obstruct the victims’ rights. Overall, these findings underscore the ways in which features of the deeply rooted power imbalance between male perpetrators and female victims shape responses to sexual harassment and assault within Chinese colleges and universities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Like their counterparts in other countries, Chinese women face many forms of sexual harassment (Can, 1995; Jiang, 2018). However, due to the sensitivity and controversy of sexual topics in the context of a collectivist culture, the problem of sexual harassment and assault in China has not received sufficient attention from scholars (Parish et al., 2006; Shi & Zheng, 2021). It was only after the anti-sexual violence and anti-sexual harassment movement known as #MeToo emerged globally and spread to China in 2018 that scholars began to conduct more research on the topic of sexual harassment in China (Li et al., 2021; Xu & Zhang, 2022; Zeng, 2020). Most research on sexual harassment and assault in China predominantly addresses workplace misconduct (Chen et al., 2021; Shi & Zheng, 2020), such as in the hospitality industry (Li et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2019), manufacturing factories (Pei et al., 2022), financial institutions (Liao et al., 2016; Xin et al., 2018) and medical institutions (Zeng et al., 2019, 2020). To date, research on sexual harassment in Chinese colleges and universities remains limited (Qiu & Cheng, 2022).

Notably, Chinese students in universities can be more vulnerable than workplace employees because of students’ limited social experience and the paternalistic hierarchical structure between teachers and students in Chinese culture (Qiu & Cheng, 2022). Indeed, the #MeToo movement in China was largely inspired by Luo Xixi, a former PhD student at China’s Beihang University, who accused her supervisor, professor Chen Xiaowu, of repeated sexual harassment (Zeng, 2020), and most of the following allegations were made by current and former graduate students (Zeng, 2020), demonstrating the extent and severity of sexual harassment on Chinese college campuses. Research on sexual harassment and assault at Chinese colleges and universities has focused on students’ understanding of sexual harassment and the relationship to experiencing and responding to sexual harassment (Li et al., 2022a, 2022b; Tang et al., 1996), the association between tolerance of sexual harassment and traditional gender values (Mou et al., 2022), and sexual harassment and assault disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth (Li et al., 2022a, 2022b). Although it is widely known that the core of the sexual harassment and assault problem involves power and control (MacKinnon, 1979; ProPublica, 2017; Robbins et al., 1997), surprisingly, there is only one interview-based qualitative study specifically investigating how the power imbalance between college students and their teachers shapes sexual harassment in Chinese academia (Qiu & Cheng, 2022). To our knowledge, there is no empirical evidence systematically demonstrating the role of power imbalances in sexual harassment and assault within the Chinese university context. In fact, in China’s authoritarian political system and traditional cultural context, power imbalances may have unique forms of representation that may differ from those of other countries and thus need special investigation.

Scholars have long argued that power imbalance is at the heart of sexual harassment and assault (MacKinnon, 1979), and the central goal of the perpetrator’s abuse of power is to gain or maintain control over the victim, who is in a position of powerlessness (Gravelin et al., 2019; Minnotte & Legerski, 2019). Perpetrators with more power can exert more influence and control over the victims, while the victims with less power are often perceived as more controllable by perpetrators and are therefore more likely to be the target of sexual harassment (Hardt et al., 2023; Wamoyi et al., 2022). Furthermore, based on the gap in power between the perpetrator and the victim, the perpetrator will decide what kind of sexual harassment and assault to commit, and the victim, the perpetrator, and the college/university will decide how to respond after the sexual harassment and assault has occurred (see Fig. 1).

In the current study, we examined how the power imbalance between perpetrators and victims shape sexual harassment and assault at Chinese colleges and universities, and more specifically, how the power status of the perpetrator and the victim affect the severity of the sexual harassment and assault in Chinese college/university and the behavioural responses of the three main parties involved; that is, the victim’s denouncement of the perpetrator, the perpetrator’s denial of allegations, and the college/university’s obstruction of the victim’s rights. Our overarching hypothesis is that the greater the power imbalance (i.e., the more power the perpetrator has and the less power the victim has), the more likely the perpetrator will be protected than the victim in the aftermath of the assault.

Power Imbalances Within the Chinese Context

The most distinctive characteristic of Chinese higher education under the rule of the Communist Party of China (CPC) is that colleges and universities have been integrated into the communist political and administrative hierarchy, and all Chinese public universities are assigned administrative ranks (Wang & Vallance, 2015; Ying et al., 2017). Chinese colleges and universities, ranging from the elite to less recognized, can be categorized as national key universities (including the “985 Project,” “211 Project” universities, and “Double First-Class” universities), other publicly owned colleges and universities, and privately owned colleges and universities. The higher the rank of a college or university, the more political and administrative power it has and the more resources (including funding and network resources) it receives from the government (Wang & Vallance, 2015). The “985 Project,” “211 Project,” and “Double First-Class,” looking to build world-class universities in the twenty-first century, are the key programs of the CPC’s strategy of “using technology and education to build a modern power” (Ying, 2011; Zong & Zhang, 2019). The national key universities are therefore given special treatment, both financially and politically. For instance, from 2009 to 2013, the national key universities, numbering only 115, received nearly 70% of all government research funding, while more than 2000 other colleges and universities received only 30% (Lin & Wang, 2022).

Moreover, the national key universities hold ranks equivalent to municipal or even vice-provincial administrations, granting them a superior political standing. Notably, nearly 40% of the leaders at these national key universities administered by the Ministry of Education have served as leaders in the central or provincial governments (Huang, 2017). Privately owned colleges and universities are financially self-sufficient, are associated with no administrative level, and are thus in the lowest ranking position in the hierarchical structure of Chinese higher education. Teachers affiliated with higher-ranking colleges or universities have a higher social status, more influence, more resources, and most importantly, more interpersonal relationships with government officials. It should be mentioned that the rank of a college or university influences not only the power of that college or university as an institution, but it also confers social status and power on faculty who work there.

The official rank-oriented standard, which is called Guan Ben Wei (官本位 in Chinese), is deeply embedded in the Chinese culture and value system, in which the government official’s social class is always at the top of China’s hierarchical system and involves privileges greater than those of other classes. This profoundly influences individuals’ and organizations’ ways of thinking and behaving (Lei, 2011; Wang & Hua, 2020). Meanwhile, Chinese public colleges and universities are very similar to government departments: all administrative and teaching staff are located within a hierarchically organized structure with corresponding political and administrative power at different levels, and they are appointed, promoted, and even evaluated like bureaucrats (Ying et al., 2017). Thus, having an administrative position at a Chinese college or university means being, in essence, an honourable and powerful official. It is no surprise that ambitious academics in Chinese universities always strive for administrative positions to obtain the official career benefits of more political and administrative power, greater renown, respect from others, and increased research projects and grants once appointed (Wang et al., 2014).

Importantly, the CPC membership of university staff is crucial for them to win higher ranks in their official careers because the standing committee of the CPC committee is the real power at all levels of Chinese public sectors, including Chinese colleges and universities (Wang & Hua, 2020). In addition, the necessary academic capability is also indispensable for acquiring an administrative position. As an old Chinese saying goes, “Officialdom is the natural outlet for good scholars (学而优则仕)” (Wang & Hua, 2020); most of those who hold administrative positions in Chinese colleges and universities also hold relatively high-level faculty titles (at least associate professors). A higher-level faculty title also means more academic power over students in almost all important aspects of college life, such as admission, graduation, and award selection (Cipriano et al., 2023).

Therefore, based on the foregoing analysis, we propose that the power status of the perpetrators in Chinese colleges and universities can be observed along four dimensions (see Fig. 1): status and resources (rank of the college/university), administrative power (perpetrator’s administrative position), political background (perpetrator’s CPC membership), and academic power (perpetrator’s faculty title).

Compared with the perpetrators in colleges and universities, victims (mainly students) with no administrative or academic power are in a vulnerable position, and perpetrators involved in sexual harassment and assault are more likely to target victims who are powerless and can be easily controlled or disposed of during and after the offence (Beauregard & Martineau, 2015). Further, under the influence of China’s five-thousand-year male chauvinism (Huang, 1983), women are often considered to be the private property of men, and thus if a woman with a boyfriend is assaulted by a perpetrator, there will likely be retaliation, which can deter some perpetrators. Therefore, students at Chinese colleges and universities who are single and thus without companionship are considered less protected and at higher risk of encountering more serious sexual harassment and assault. It should be noted that we use the term “single” in this article to refer to the status of not being in a dating relationship (unmarried and without a boyfriend or girlfriend).

Previous studies have also revealed that economically powerless individuals who were associated with poor family economic status often face higher rates of sexual harassment (Eller, 2016; Wamoyi et al., 2022). Additionally, there is another important but often neglected powerlessness of victims, that is, spatial powerlessness. The perpetrators tend to commit their crimes in relatively isolated places where the victims cannot call for help. By placing the victims in an extremely powerless and vulnerable position, the perpetrators can easily control them through their advantages in power.

Therefore, based on the foregoing analysis, we propose that the power status of the victims in Chinese colleges and universities can be observed along three dimensions (see Fig. 1): social relationship (victim’s single status), economic power (victim’s family status), and spatial vulnerability (place of sexual harassment and assault).

Specific Impacts of Power Imbalances Within Chinese Universities

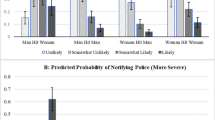

In this section, we provide a specific analysis of how the power imbalance affects the behaviours of the perpetrators, victims, and colleges/universities with respect to the severity of the sexual harassment and assault, the victim’s own defence of their rights, perpetrator’s response to the allegations, and the university’s obstruction of victims’ defences of rights (see Fig. 2).

Severity of the Sexual Harassment and Assault

Prior to the sexual harassment and assault, perpetrators may screen for individuals who would be less protected as targets (Beauregard & Martineau, 2015). A common tactic used by perpetrators is to ask for information about the victim’s relationship status (single status) and family background (including family’s economic status) under the guise of a teacher’s concern for the student (Cleveland & Kerst, 1993; Dziech & Weiner, 1990). Due to their trust in teachers, Chinese college students are generally willing to respond honestly to sensitive personal questions (Hua et al., 2023). After assessing the victim’s powerlessness and identifying him/her as a target of sexual assault, the perpetrator will use his power to create opportunities to place the victim in a spatially isolated and powerless environment to commit the sexual harassment or assault. The ability to control the setting gives teachers special access to the students (Dziech & Weiner, 1990), and the locations are often strategically selected based on the intended severity of the sexual harassment and assault. We hypothesized that the severity of perpetrators’ sexual harassment and assault would be higher for victims who are single and who are assaulted in isolated environments (Hypothesis 1).

Victim’s Denouncement of the Perpetrator

After experiencing a sexual harassment or assault, victims are faced with the difficult decision of whether to denounce the perpetrator, and when to do so. The perpetrators’ power allows them to exert influence and even control over the victim in many ways, such as academic performance, awards, graduation, and jobs. Once a victim chooses to denounce the perpetrator, it typically means a complete break with the perpetrator. If the denunciation is unsuccessful, the perpetrator may retaliate against the victim, who will then have almost no place to live at their college or university. In fact, when victims do denounce, their cases infrequently result in their perpetrators’ expulsion (Richards, 2019; Richards et al., 2021; Rosenthal & Freyd, 2022).

Within the Chinese higher education system, having an administrative position means essentially being an official, and offending officials is frowned upon for anyone in China. Those administrative position holders possess the real power and dominate decision-making processes, enabling them to influence nearly all aspects of daily academic work (Li et al., 2013). Offending someone who holds administrative power can have disastrous consequences for a victim’s college experience. Given the risks involved, victims may be stricken by fear and confusion and may not denounce the perpetrators right away (Klemmer et al., 2021; Koçtürk & Bilginer, 2020), but instead choose to do so after graduation when they are no longer under the power of perpetrators. Therefore, whether to denounce the perpetrator after graduation can be selected as an important indicator of the victim’s own defence of their rights. We hypothesized that the victim’s denunciation of the perpetrator after her graduation rather than before would be associated with the perpetrator’s having an administrative position (Hypothesis 2).

Perpetrator’s Denial of Allegations

Although many perpetrators adopt avoidance and silence as their strategy in response to accusations, there are also many who do not remain silent, instead choosing a strategy to deter victims from speaking up. Their tactics include denying or minimizing the abuse, attacking the victim’s credibility, and portraying themselves as the victims (Freyd, 1997). The acronym DARVO encapsulates this pattern: Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender (Rosenthal & Freyd, 2022). Notably, research has found that increased levels of exposure to DARVO were associated with greater feelings of self-blame among victims (Harsey et al., 2017).

The perpetrator’s response strategy may be influenced by various factors, including the extent to which they are afforded protection by their institution and network. For example, if the perpetrator believes that he can obtain sufficient protection from institutions and authorities, and the victim lacks an influential family background, the perpetrator may be more inclined to deny the allegations. Researchers found that the clerics who were engaged in sexual misconduct gained access to the protection offered by the church’s power, prestige, and wealth in ways that the laity did not (De Weger & Death, 2018). Similarly, college administrators and the authorities may seek to protect the reputation of the institution and the CPC, and thus protect the perpetrators. Higher-ranked universities have more resources and power to delete negative posts on social media, control comments, and even influence the direction of public opinion, thus indirectly protecting the perpetrators. In contrast, poor family backgrounds of victims cannot provide adequate protection for victims. Students from poor families cannot access sufficient resources and power from their families (Chen & Wei, 2011; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2016), and are thus more vulnerable to being treated perfunctorily by the perpetrators in the aftermath of a sexual harassment or assault. We hypothesized that the perpetrator’s greater tendency to deny allegations would be associated with the lower economic status of the victim’s family, the higher ranking of the college/university the perpetrator was employed by, and the perpetrator’s CPC membership (Hypothesis 3).

College/University’s Obstruction of the Victim’s Rights

Higher education institutions often choose to protect their own interests and reputations by trying to obstruct the victims’ defences of their rights (Smith & Freyd, 2014). Chinese colleges/universities often tend to take actions to prevent a scandal from spreading as much as possible and try to reach a private settlement with the victim. Many colleges/universities even send administrative staff to do so-called ideological work on victims, with many victims forced to delete posts or even abandon their rights due to the position of power of these institutions, especially higher-ranked colleges/universities. Further, to avoid punishment from the CPC and damage to the party image, colleges/universities may be more inclined to cover up the scandals and obstruct the victims’ defences of their rights when the perpetrators have CPC membership. We therefore hypothesized that the tendency of Chinese college/university to obstruct victims’ defences of their rights would be associated with factors such as CPC membership of the perpetrators, and the ranking of the college/university (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Study Subject and Data Collection

This study adopted a hybrid research design, combining elements of the case study approach with quantitative analysis. To test our hypotheses and examine the role of power in sexual assault cases involving Chinese higher education institutions, we identified publicly reported real-world cases of sexual harassment and assault at Chinese colleges/universities that occurred between faculty members as the perpetrators (including management and support personnel, teaching and research staff) and students as the victims (including undergraduate students, postgraduate students, and PhD students) in Chinese colleges/universities up to the end of 2023. We used search engines like Baidu (China’s Google counterpart) and Google, along with social platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and Zhihu (analogous to WhatsApp, Twitter, and Quora, respectively) in China, and employed the following keywords to identify validated and widely reported sexual harassment and assault cases: “学院/大学性骚扰” (“college/university sexual harassment”) and “学院/大学性侵” (“college/university sexual assault”).

In our search for cases, we did not limit the time frame or the gender of the victims and perpetrators to collect the most comprehensive sample of cases possible. It is important to note that the research aim did not include an analysis of cases that involved any romantic consensual relationships between teachers and students (Eller, 2016). Each case was meticulously coded for variables relating to general characteristics of the sexual harassment and assault cases, power status of perpetrators and victims, severity of sexual harassment and assault, and the post-incident behaviours of the victims, the perpetrators and their colleges/universities. This coding process translated qualitative case details into quantifiable data, laying the groundwork for regression analysis. To the best of our ability, we collected and organized all the information of eligible cases including news reports about the incident, victim’s denouncement letter, perpetrator’s resume, official announcements from colleges/universities, etc. Whenever news reports or accusations of sexual harassment and assault related to Chinese higher education institutions was discovered, we sought out additional details like the victim’s denouncement letter, the perpetrator’s resumé and the official announcements to gain a complete understanding of each incident. The data, mainly textual materials, were systematically organized and analysed using MaxQDA software.

We obtained 115 cases of sexual assault incidents occurring on Chinese college/university campuses from news media and social networks. After excluding cases that occurred between colleagues and those with significant data missing, we ultimately acquired 93 valid cases involving 93 different victims and 82 different perpetrators, each containing all the necessary variable data. The reason for this situation is that some perpetrators were repeat offenders who had assaulted different students at different times, leading to some victims accusing the same individual.

Measures

Dependent Variables

This study aimed to investigate how the power imbalance between perpetrators and victims shapes the behaviours of victims, perpetrators, and colleges/universities. We examined four main dependent variables: the severity of sexual harassment and assault, the victim’s denouncement of the perpetrator, the perpetrator’s denial of allegations, and the college/university’s obstruction of the victim’s rights.

Severity of Sexual Harassment and Assault

Based on previous studies (Fedina et al., 2018; Filak, 2009), the severity of sexual harassment and assault was categorized into four ascending levels: verbal sexual harassment (including slurs and crude sexual remarks and repeated requests for dates), physical sexual harassment (including hugging and touching non-sexual parts of the body), molestation behaviour (including touching sexual organs and attempted sexual assault), and sexual abuse (forced sexual relationship). We obtained these data directly from the victim’s denouncement. Victims often describe their experiences clearly, making it possible to code the severity of sexual harassment or assault from their accounts.

Victim’s Denouncement of the Perpetrator

We coded this variable to indicate whether the victim publicly denounced the perpetrator after graduation, categorized as “Yes” or “No.” These data were obtained through the victim’s denouncement or by comparing the time of the denouncement with the victim’s enrolment or graduation dates.

Perpetrator’s Denial of Allegations

We coded this variable to indicate whether the perpetrator tended to deny the sexual harassment or sexual assault charge, categorized as “Admit,” “Non-response,” or “Deny” (Bongiorno et al., 2020). These data were obtained directly from the denouncement letters or news reports.

College/University’s Obstruction of the Victim’s Rights

We coded this variable to indicate whether the college/university attempted to obstruct the victim’s defences of their rights, categorized as “Yes” or “No.” It should be noted that during the coding process, we categorized two types of behaviours as constituting obstruction: the college/university evading, delaying, or failing to investigate students’ denouncement, and even retaliating against students for making these denouncements; and the college/university pressuring students or their parents to cease denouncements or to delete relevant online posts.

Independent Variables

The core independent variables in this study were the power status of the perpetrator and victim. Based on the theoretical analysis presented earlier, we coded the power status of the perpetrator across four dimensions: rank of the college/university (three codes: private colleges and universities, regular public colleges and universities, national key universities), perpetrator’s administrative position (two codes: yes or no), perpetrator’s CPC membership (two codes: yes or no), and perpetrator’s faculty title (four codes: no faculty title, lecturer, associate professor, or professor). All the above variables were obtained from the perpetrator’s resume.

We coded the power status of the victim across three dimensions: victim’s single status (two codes: yes or no), victim’s family status (two codes: not poor or poor), and place of sexual harassment and assault (two codes: non-isolated or isolated). Data for place of sexual harassment and assault was obtained from the victim’s denouncement, with non-isolated places referring to more public or open spaces such as on-campus public spaces, classrooms, and social networking platforms, and isolated places referring to more private or closed spaces such as the perpetrator’s office or studio, home or dormitory, or off-campus venues including hotels and field sites. The victim’s single status was determined directly from their denouncements, such as when they explicitly state they are single, or inferred from the victim’s denouncement letters or news reports, such as referring to “my boyfriend/my girlfriend.” The economic status of the victim’s family was determined from certain keywords used in reference to the families within the denouncements and news reports, such as “poor,” “low-income,” “difficult family conditions,” “unable to afford,” “from a rural area,” or “farmer.”

As examined in this paper, the severity of sexual harassment and assault varies with the degree of environmental isolation. Therefore, before the sexual harassment or assault took place, the variable “place of sexual harassment and assault” was used in the regression where the dependent variable is “severity of sexual harassment and assault.” However, once the incident had occurred, it becomes a settled matter. In terms of how to handle and respond to the incident subsequently, the place where the sexual harassment or assault occurred is no longer as important. Thus, the place of sexual harassment and assault is not directly related to the subsequent response strategies of the victim, the perpetrator, and the college/university, and was excluded from the analyses of the post-incident behaviours of the three parties involved after the incident.

Control Variables

Based on the information that was available from the materials we collected and past research on sexual harassment and assault, this study included the demographic characteristics of the victim, such as the victim’s age and education level, and the demographic characteristics of the perpetrator, such as the perpetrator’s educational background, age, and marital status, as control variables. We obtained the demographic characteristics of the victims from their denouncement letters or news reports, while the perpetrators typically have their complete resumes publicly available online, allowing us to directly gather specific data. It should be noted that since victims generally do not have public resumes and some do not disclose their age, we sometimes had to infer it from their educational stage. According to China’s current educational system and duration, the age for entering college/university is generally 18. Therefore, if a student is in their fourth year of university or at a higher educational level, their age must be 20 years or older. This is why the age of the victims is categorized into two groups: ≥ 20 and < 20, while the age of the perpetrators is provided with specific data.

What is also worth mentioning here is that the severity of sexual harassment and assault was included as a control variable in the regression analysis predicting post-incident behaviours of the three parties involved because the severity of sexual harassment and assault may affect how the three parties deal with the incident. For example, if the sexual harassment and assault is more severe, the victim may act more promptly to defend their rights. For the perpetrator and the college/university, this means potentially more severe consequences from higher authorities, which may lead them to be more inclined to deny and cover up the incident.

Additional Variables

Additional variables were coded for where available about the sexual harassment and assault cases for descriptive purposes only. These variables included: (1) characteristics of the harassment/assault (i.e., year the assault occurred, year when the assault was publicly reported, whether the perpetrator had promised benefits to the victim, whether the perpetrator had threatened the victim, whether there were other victims, and the perpetrator’s subject area; (2) characteristics of the victim’s denouncement (i.e., whether the victim denounced the perpetrator immediately after a sexual harassment or sexual assault incident occurred, whether the victim denounced by using her/his real name, the way of denouncing the perpetrator; (3) characteristics of the college/university’s response (i.e., the punishment that was finally imposed on the perpetrator).

It should be noted that for the variable “whether the victim denounced the perpetrator immediately after a sexual harassment or sexual assault incident occurred,” this paper specifically defines “immediately” as within the same day or the next day after the sexual harassment and assault incident occurred, which differs in the time definition from “whether the victim publicly denounced the perpetrator after graduation.” With this variable, we can more comprehensively illustrate the victim’s hesitation and fear after experiencing sexual harassment and assault. The variable “the way of denouncing the perpetrator” refers to the channels by which the victim denounced the perpetrator. We have categorized these channels into five types: only exposing on the internet (including WeChat, Weibo, etc.); exposing on the internet while also reporting to the universities/authorities; only reporting to the universities/authorities; reporting to the universities/authorities while also seeking help from news media; and reporting to the universities/authorities while also seeking help from news media and exposing it on the internet.

Data Analysis Method

The variable information was extracted from a wide range of materials, mainly textual sources, including news reports, victim’s denouncement letter, perpetrator’s resume, official announcements from colleges/universities, etc. (see Supplementary Material A for a sample case of text coding). While certain variables such as the gender, age, education period, faculty title, administrative position, and CPC membership can be directly accessed, others may require subjective judgment which inevitably introduces bias. To mitigate the impact of this bias and enhance the accuracy of our coding process, we implemented three main strategies. Initially, we established clear, objective rules for the evaluation of variables that required subjective judgment. For instance, the assessment of a victim’s single status was based on the presence or absence of references to romantic relationships in victims’ narratives. Expressions indicating a romantic partnership, such as mentions of “my boyfriend,” served as markers for victims not considered single. Conversely, the absence of such expressions or explicit mentions of being single highlighted their vulnerable position. Similarly, when evaluating the obstruction by colleges and universities, we focused on identifiable behaviours like delaying responses, evading responsibility, issuing threats to victims, or exerting pressure to remove public posts. Next, the materials were coded and analysed by two investigators separately. This independent coding was followed by a meticulous comparison of the results, discussing any disparities to reach a consensus. Then, all completed coding were fully reviewed by the first author to ensure credibility and trustworthiness of the analysis process (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). This final review step was critical for identifying and resolving any remaining discrepancies, ensuring the integrity of our data analysis process.

We used descriptive statistics to outline the general characteristics of sexual harassment and assault cases, power status of perpetrators and victims, severity of sexual harassment and assault, and the post-incident behaviours of the victims, the perpetrators, and the colleges/universities. Regression analyses were employed to assess the impact of the power status of perpetrators and victims on the severity of sexual harassment and assault, and the behaviours of the three parties involved after the sexual harassment and assault. Since our 93 valid cases involved 93 different victims and 82 different perpetrators, the presence of perpetrators who were involved in multiple cases suggests that the cases might not be entirely independent of each other. Therefore, we conducted our analysis by using the probit models based on the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method and reported Robust Standard Errors (RSE) to account for the clustering of multiple cases by the same perpetrator. The GEE approach is an estimation technique used to estimate the parameters of models with a possible unknown correlation among samples so as to overcome the possible violation of sample independence assumption (Chiou et al., 2020; Zeger & Liang, 1986). The statistical significance level was taken as 0.05 in all tests. Data analyses were conducted using Stata 17 and R software.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In this section, we present the descriptive statistics for the general characteristics of sexual harassment and assault cases, power status of perpetrators and victims, severity of sexual harassment and assault, and the post-incident behaviours of the victims, the perpetrators and their colleges/universities. All information is presented in Table 1.

General Characteristics of Sexual Harassment and Assault Cases

The sexual harassment and assault cases spanned a wide range of years, with the earliest being 1996 and the latest being 2022. Although the majority (62.37%) of cases happened prior to 2018, only a very small percentage (16.13%) of cases came to light before 2018, which was the year when the #Metoo movement spread to China. The tactic of coercion and bribery was most used by the perpetrators to force the victims to comply and shut up, as 30.11% of the perpetrators had threatened the victims, and 25.81% had promised benefits to the victim. In almost all cases (90.32%), there were other victims involved in the specific case, suggesting the perpetrators were often repeat offenders.

In our search for cases, we did not limit the gender of the victims and perpetrators. Nevertheless, in all publicly reported cases we collected, all the victims were women (n = 93). Most of the victims were 20 years old or older (72.04%) and were college and university undergraduate students (70.97%) when the sexual harassment and assault happened to them. All perpetrators were men and already married (75.27%). The average age of the perpetrators was 42.86 ± 9.75 years old. Most perpetrators were in the field of humanities & social sciences (55.91%), followed by an equal share in the field of science and engineering (16.13%) and within the administration of the college/university (16.13%). Most perpetrators (91.40%) had a high level of education, with 60.22% of them holding a Ph.D.

Power Status of Perpetrators and Victims

Regarding the perpetrator’s power status, more than half (53.76%) of the perpetrators were working at the national key universities, which is a staggering percentage considering that the national key universities account for only 4.5% of all higher education institutions in China. In addition, more than half (51.61%) of the perpetrators held an administrative position, nearly half (41.94%) of the perpetrators had the title of professor, and nearly three-quarters of them were CPC members.

Regarding the victim’s power status, 75.27% of the victims were single, and 10.75% were from poor families. Most of the assaults occurred in relatively isolated places where the perpetrators could easily control the victims, and where the victims would have difficulty calling for help, such as the perpetrator’s office or studio (26.88%); off-campus venues, including hotels, private rooms or corners of restaurants, field sites (23.66%); and the perpetrator’s home or dormitory (18.28%).

Severity of Sexual Harassment and Assault

Regarding the severity of sexual harassment and assault, 52.69% of the victims experienced molestation behaviour (including touching sexual organs and attempted sexual assault) or sexual abuse (forced sexual relationship), and 47.31% experienced verbal sexual harassment or unwelcome physical touching.

Victim’s Denouncement of the Perpetrator

After a sexual harassment or sexual assault incident occurred, the vast majority (89.25%) of the victims did not denounce the perpetrators immediately, and more than half (53.76%) of the victims chose to denounce the perpetrators after graduation when they were no longer under the control of the perpetrators. Most (68.82%) of the victims chose not to use their real names. In terms of the way that the victims chose to denounce the perpetrator, the vast majority (77.42%) chose to post publicly through internet platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and Zhihu, while others chose a combination method, such as posting online while also reporting to universities/authorities (the Ministry of Education, police, etc.), and very few (8.60%) chose to only report to the universities/authorities.

Perpetrator’s Denial of Allegations

After being denounced by victims, very few (9.68%) perpetrators were willing to admit sexual harassment or sexual assault charges, and their usual tactic was to refuse to respond (52.69%) or to outright deny the allegations (37.63%) because they knew that if they continued to deny it, they still had a chance to escape punishment and avoid serious consequences.

College/University’s Obstruction of the Victim’s Rights

Most of the colleges and universities (64.52%) demonstrated attempts to obstruct the victims’ defences of their rights. Overall, 32.26% of perpetrators were dismissed, 36.56% were demoted but not dismissed, and 31.18% received no punishment at all.

Regression Analyses

Power Status and the Severity of Sexual Harassment and Assault

To investigate how the power status of perpetrator and victim relates to the severity of the sexual harassment and assault, a GEE probit regression model was conducted with severity of sexual harassment and assault as the dependent variable. As we can see from the results in Table 2, among the variables characterizing the power status of perpetrator and victim, victim’s single status had an odds ratio (OR) of 1.74 and was statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that those who were single in Chinese colleges and universities were at higher risk of encountering more serious sexual violations, supporting Hypothesis 1. In addition, we also found a large odds ratio of 3.57 for the isolated place of sexual harassment and assault which was also statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that more isolated settings for the assault were associated with more severe assaults, which also confirmed Hypothesis 1. For the control variables, we found that only the perpetrator’s age showed significant effects on the severity of sexual harassment and assault (p = 0.007), and the odds ratio was lower than 1 (OR = 0.97), indicating that the older the perpetrator was, the less severe the assault.

Power Status and Victim’s Denouncement of the Perpetrator

To investigate how the power status of the perpetrator and victim related to the victim’s denouncement behaviour, a GEE probit regression model was constructed with victim’s denouncing the perpetrator after graduation as the dependent variable. The results are displayed in Table 3. Among the variables characterizing the power status of perpetrator and victim, perpetrator’s administrative position had a significant (p = 0.008) effect on the likelihood of denouncing the perpetrator after graduation, and the odds ratio of 3.25 was much higher than 1, indicating that if the perpetrator held an administrative position, it was more likely that the victim denounced him after graduation, presumably when she was more free from the control and threats of the perpetrator. The findings support Hypothesis 2. Interestingly, among the control variables, the perpetrator’s divorced marital status had a significant impact on the victim’s delaying their denouncement until after graduation (p = 0.011), with an odds ratio of 6.73, indicating that if the perpetrator was divorced, the victim was more likely to denounce the perpetrator after graduation.

Power Status and the Perpetrator’s Denial of Allegations

To investigate how the power status of perpetrator and victim affect the perpetrator’s response to accusations of assault, a GEE probit regression model was conducted with perpetrator’s denial of allegations as the dependent variable. The results are presented in Table 4. Among the variables characterizing the power status of perpetrator and victim, victim’s family status (OR = 1.78 and p = 0.039), rank of the college/university (OR = 1.87 and p = 0.002 for the category “regular public colleges and universities”, OR = 2.64 and p < 0.001 for the category “national key universities”), and perpetrator’s CPC membership (OR = 1.55 and p = 0.013) significantly predicted perpetrator’s denial of allegations with the odds ratios all larger than 1. These results support Hypothesis 3 in that the lower economic status of the victim’s family, the higher the rank of the college/university employing the perpetrator and being a CPC member all contributed to greater denial of the allegations by the perpetrator.

Power Status and the College/University’s Obstruction of the Victim’s Rights

To investigate how the power status of perpetrator and victim affect college/university’s obstruction of the victim’s rights, a GEE probit regression model was conducted with college/university’s obstruction of the victim’s rights as the dependent variable. The results are presented in Table 5. Among the variables characterizing the power status of perpetrator and victim, the rank of the college/university (OR = 13.87 and p < 0.001 for the category “regular public colleges and universities”, OR = 15.96 and p = 0.001 for the category “national key universities”) and perpetrator’s CPC membership (OR = 2.85 and p = 0.017) significantly predicted college/university’s obstruction of the victim’s rights with the odds ratios all larger than 1. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 4 that the higher the rank of the college or university, and being a member of the CPC, predicted a greater tendency to obstruct the victims’ defences of their rights by Chinese higher education institutions. In addition, among the control variables, the victim’s age significantly predicted obstruction (p = 0.005) with a large odds ratio of 3.99, indicating that the older the victim was, the more likely the college/university was to take measures to pressure the victim abandon their rights.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to systematically investigate the role of power imbalance between the perpetrator and victim in real-world sexual harassment and assault cases within the Chinese higher education context. The findings suggest that the power status of the perpetrators in Chinese colleges and universities can be observed across four dimensions: status and resources (rank of the college/university), administrative power (perpetrator’s administrative position), political background (perpetrator’s CPC membership), and academic power (perpetrator’s faculty title). The power status of the victims can be reflected across three dimensions: romantic relationship (victim’s single status), economic power (victim’s family status), and spatial vulnerability (place of sexual harassment and assault). Descriptive statistics highlight the stark power imbalance, with perpetrators typically occupying positions of significant power, whereas victims often find themselves inherently vulnerable.

Despite many sexual harassment and assault incidents predating 2018, public reports surged in that year with the #MeToo movement’s arrival in China. In the public reported cases, all victims were female, predominantly over 20 and undergraduates, while perpetrators were all male, largely from the humanities and social sciences, well-educated, married, with an average age of 42.86 ± 9.75. Several reasons may explain why all victims were female. One reason is that strong masculinity norms in China render acknowledging sexual assault as a weakness and shameful, which may deter Chinese men from reporting these experiences. Another reason may be that, in reality, very few men have experienced unwanted physical contact from teachers in Chinese universities, and even fewer have been the targets of teachers’ coercive sexual behaviours (Tang et al., 1996).

The perpetrators typically held significantly more power than the victims in their official capacities as CPC members, working at China’s elite universities, and holding administrative positions and senior faculty titles. In contrast, the victims have less sources of power to rely on, with most being single and having the assault occur in isolated settings where there is no one to help them. Over half of the victims faced severe sexual violations, including touching sexual body parts, attempted sexual assault, and rape. These findings suggest that the perpetrator’s identification of women to assault was not random. The perpetrators selectively targeted victims based on their powerlessness, particularly their single status and the spatial environment, which then dictated the severity of the sexual harassment and assault.

Perpetrators often used coercion and bribery to deter victims from reporting them, with many being repeat offenders. This pattern of findings suggests that the perpetrator’s power over the victim led to most victims delaying their denouncements until after graduation, and many victims preferred online anonymity to direct institutional reporting, indicating a profound mistrust in the ability of institutions to act impartially. In fact, according to the experiences of some students, reporting misdemeanours to colleges/universities or authorities did not actually work, and the only thing they could do was make their complaint online (CGTN, 2019).

Moreover, the post-incident reactions from both the perpetrators and the higher education institutions were centred around protecting the perpetrator and the reputation of the institution. A strategy of denial or no response was commonly employed by perpetrators, and dismissals or any form of punishment did not occur in the majority of the cases. Universities seemed to value their reputation above victims’ rights, and thus often pressured victims to forsake their claims and stay silent. It should be noted that, in the cases involving CPC-affiliated perpetrators, the fear of party sanctions likely motivated denials of wrongdoing, which was mirrored by university actions that impeded victims’ rights. This mutual avoidance strategy adopted by both the perpetrators and the higher education institutions resulted in a concerted effort to obfuscate the truth, effectively absolving both parties from higher-level scrutiny. Consequently, a complex dynamic emerged between perpetrators and academic institutions, with CPC membership providing a veil of protection against consequences.

Our results also reveal that the power imbalance integral to sexual harassment and assault cases within Chinese colleges and universities differs from that in other countries. In China, the source of the perpetrator’s power is deeply connected to China’s traditional patriarchal culture and bureaucratic political system. Single women who are not affiliated with men are in a weaker power position and more easily manipulated, and factors such as higher administrative level of the college/university, the perpetrator’s administrative position, and party membership can provide protection for the perpetrator. However, in some other countries, such as the United States, the power differential between perpetrator and victim often arises from the perpetrator’s academic authority and higher economic status (Eller, 2016; Klein & Martin, 2021). For example, a professor might require a student to engage in sexual relations in exchange for passing the course exam.

Our study’s strengths lie in its archival analysis of actual real-world cases, providing a high degree of ecological validity. Our findings contribute to a broader understanding of power imbalances in sexual harassment and assault cases, highlighting unique aspects within the Chinese colleges/university context and offering insights that applicable to other similar authoritarian countries.

It should be noted that a power differential may be automatically imposed due to gender, making Chinese women inherently more vulnerable compared to men (Qing, 2020; Xie, 1994). However, this inherent gender-based power imbalance does not necessarily affect the response strategies after sexual harassment and assault. In fact, if the male perpetrator and the female victim are strangers, rather than having the teacher-student relationship with the various power imbalances mentioned in this paper, the psychological burden on the female victim to denounce the male perpetrator may be different (Li & Zheng, 2022). Additionally, Chinese authorities view the number of convictions for sexual crimes as a measure of political achievement, believing that an increase in the handled cases reflects better protection of women’s rights (Liu, 2024). Therefore, the unique power imbalances between male perpetrators and female victims proposed in this paper can effectively predict responses to sexual harassment and assault within the Chinese colleges/university context and are not overshadowed by the inherent gender-based power differential.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While our study provides significant insights, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. One limitation is the variability in how information was coded, which may depend on the code book and the definitions of variables used for the research. This variability could influence the consistency and reliability of our data. Additionally, other indicators of power status, such as the personal relationships between perpetrators and high-ranking officials, need to be examined in future studies. We were unable to control for certain variables or obtain detailed information about some variables, such as the victim’s family composition (e.g., whether they are an only child, whether both parents are alive),that may be useful in understanding power dynamics more comprehensively. Another limitation is that our study only includes cases that were reported, excluding those who did not report their experiences, thereby potentially biasing our findings. Also, more attention is needed on male victims, who report less and may face greater challenges in sharing their experiences. Identifying and studying this group through social media posts, for example, could deepen our understanding and support for all victims of sexual misconduct.

Furthermore, we did not quantify the power imbalance itself but rather quantified the power of the perpetrator and the victim separately and used their statuses as predictors. Developing a power score that accounts for the relative power difference, where victims might also possess some power, could provide a more nuanced understanding of these dynamics. Moreover, our study focuses on clear power differentials, such as man-woman and professor-student relationships. Future research should explore scenarios with less stark power differentials to determine if the outcomes would be similar in those contexts.

Lastly, reliance on widely reported, verified incidents of sexual harassment and assault ensures the authenticity and reliability of our data; however, it inherently limits our sample size, which may impact the interpretation of the findings. To broaden our research scope and reinforce our conclusions, future studies could employ web scraping technology to gather extensive data from public postings on China’s social networking platforms, focusing on victims’ self-reports for textual and quantitative analyses. In the Chinese cultural context, the fact that victims dare to publicly talk about their experiences of being sexually assaulted at all indicates that the postings have a certain degree of credibility. Moreover, the presence of some inaccuracies in a large ecologically valid dataset would be unlikely to significantly distort the overall findings, thus supporting the overall conclusions.

Practice Implications

Our study illuminates the profound impact of power imbalances between the perpetrator and victim on sexual harassment and assault within Chinese higher education, highlighting the inherent vulnerability of Chinese college/university students. Moreover, the complicity of educational institutions, deeply embedded within China’s administrative structure, and their faculty’s bureaucratic ties exacerbate this vulnerability, fostering an environment where abuse can flourish unchecked. This dynamic not only instils a deep fear of administrative authority among victims but also aligns the interests of perpetrators, universities, and administrative authorities towards minimizing scandal exposure to protect reputations, resulting in inadequate investigation and accountability measures. Thus, the internal investigations conducted by universities frequently lead to a low dismissal rate of perpetrators, with a significant number of them facing no consequences, thereby undermining public trust. Our findings underscore a pressing need for systemic reform within Chinese higher education to address and mitigate the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault of women.

In fact, Chinese authorities have always been committed to the prevention of sexual harassment and assault at colleges and universities, recognizing that such scandals tarnish the government’s image and could potentially undermine the CPC’s legitimacy — outcomes the party is keen to avoid. On November 15, 2019, China’s Ministry of Education, alongside six other government departments, issued a new guideline on teachers’ professional ethics named “Opinions on Strengthening and Improving the Construction of Teachers’ Ethics and Style in the New Era,” which emphasized zero tolerance of sexual harassment on campus (CGTN, 2019). However, this can hardly solve the problem of shielding, and if shielding exists, sexual harassment and assault will remain a serious problem at Chinese colleges and universities.

To address this, we suggest that an independent committee composed of members of the community who have no interest related to the perpetrators or universities should be established by the Chinese government to be responsible for handling sexual misconduct reports, conducting thorough investigations, reporting findings to both the government and public, and recommending punitive actions. We believe that such an independent committee would not only serve as a powerful deterrent against sexual misconduct but also empower victims to report offences. Meanwhile, it is critical to not only empower victims but also disempower perpetrators. Chinese governments should further promote the de-bureaucratization reforms in Chinese college and university, eliminating the bureaucratic administrative ranks of institutions and their employees, thereby reducing the administrative power to intimidate victims (Jian & Mols, 2019). Crucially, these proposals align with the CPC’s higher echelons’ aspirations to mitigate sex scandal occurrences that could besmirch the party’s reputation, making it a feasible and impactful initiative.

Additionally, it must be pointed out that the cases in this study, being based solely on publicly reported real instances of sexual assault, mainly included those who dared to denounce the perpetrators. In fact, compared to those who had the courage to come forward, victims who did not might be in an even more powerless position. Their economic conditions, social support, and family relationships could be weaker than those of the victims studied in this paper. This further underscores the importance of our research, suggesting that special consideration should be extended to support disadvantaged students, who may face heightened vulnerabilities due to economic or familial circumstances, ensuring a safer educational environment for all. We should conduct investigations targeting students in powerless situations, proactively identifying and assisting potential victims, rather than merely reacting to reports. The measurement of the victim’s power proposed in this paper could be effectively used to identify these potential victims.

Our research also revealed that sexual harassment and assaults that occurred in relatively isolated places such as off-campus hotels and the perpetrator’s home were generally associated with more serious sexual harm. Thus, codes of conduct aimed at helping teachers and students uphold appropriate boundaries should be implemented. Relevant education about the cognition and prevention of sexual harassment, such as avoiding being alone with teachers in a relatively closed environment, which is seriously lacking in China, should also be developed and delivered to students.

Conclusion

The current study examined the power status of perpetrators and victims of sexual harassment and assault incidents at Chinese colleges and universities as predictors of response to sexual assaults. We found that perpetrators were generally in high positions of power, while the victims were in a naturally vulnerable position, and this power differential, rooted in China’s traditional culture and bureaucratic political system, shaped the behaviours of victims, perpetrators, and Chinese higher education institutions. Specifically, the power imbalances were robustly linked to more serious sexual violations and a pattern of responses that protected perpetrators and sustained their powerful status, including victim silence, perpetrator denial, and institutional shielding. This study not only sheds more light on the current state of sexual misconduct at Chinese colleges and universities but also paves the way for future research and more effective policy interventions to combat the deep-rooted gendered power dynamics of this problem.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Beauregard, E., & Martineau, M. (2015). An application of CRAVED to the choice of victim in sexual homicide: A routine activity approach. Crime Science, 4(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-015-0036-3

Bongiorno, R., Langbroek, C., Bain, P. G., Ting, M., & Ryan, M. K. (2020). Why women are blamed for being sexually harassed: The effects of empathy for female victims and male perpetrators. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319868730

Can, T. (1995). The existence of sexual harassment in China. Chinese Education & Society, 28(3), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-193228036

CGTN. (2019). China releases new guideline to strengthen teachers’ ethics. CGTN. Retrieved February 19, 2023, from https://news.cgtn.com/news/2019-12-17/China-releases-new-guideline-to-strengthen-teachers-ethics-MuzXTlTf8s/index.html

Chen, H., Kwan, H. K., & Ye, W. (2021). Effects of sexual harassment on work–family enrichment: The roles of organization-based self-esteem and Polychronicity. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40, 409–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09787-5

Chen, J.-K., & Wei, H.-S. (2011). Student victimization by teachers in Taiwan: Prevalence and associations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(5), 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.01.009

Chiou, Y.-C., Fu, C., & Ke, C.-Y. (2020). Modelling two-vehicle crash severity by generalized estimating equations. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 148, 105841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105841

Cipriano, A. E., Holland, K. J., Rieger, A., & O’Callaghan, E. (2023). “I had no power whatsoever”: Graduate student survivors’ experiences disclosing sexual harassment to mandatory reporters. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 23(1), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12336

Cleveland, J. N., & Kerst, M. E. (1993). Sexual harassment and perceptions of power: An under-articulated relationship. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1993.1004

De Weger, S. E., & Death, J. (2018). Clergy sexual misconduct against adults in the Roman Catholic Church: The misuse of professional and spiritual power in the sexual abuse of adults. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 30(3), 227–257. https://doi.org/10.1558/jasr.32747

Dziech, B. W., & Weiner, L. (1990). The lecherous professor: Sexual harassment on campus (2nd ed). University of Illinois Press.

Eller, A. (2016). Transactional sex and sexual harassment between professors and students at an urban university in Benin. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(7), 742–755. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1123295

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Fedina, L., Holmes, J. L., & Backes, B. L. (2018). Campus sexual assault: A systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(1), 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016631129

Filak, C. J. (2009). Sexual assault and health behaviors of college women: A secondary analysis. George Mason University

Freyd, J. J. (1997). Violations of power, adaptive blindness and betrayal trauma theory. Feminism & Psychology, 7(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353597071004

Gravelin, C. R., Biernat, M., & Baldwin, M. (2019). The impact of power and powerlessness on blaming the victim of sexual assault. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217706741

Hardt, S., Stöckl, H., Wamoyi, J., & Ranganathan, M. (2023). Sexual harassment in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(5), 3346–3362. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221127255

Harsey, S. J., Zurbriggen, E. L., & Freyd, J. J. (2017). Perpetrator responses to victim confrontation: DARVO and victim self-blame. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(6), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1320777

Hua, L., Wang, Y., Mo, B., Guo, Z., Wang, Y., Su, Z., Huang, M., Chen, H., Ma, X., Xie, J., & Luo, M. (2023). The hidden inequality: The disparities in the quality of daily use masks associated with family economic status. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1163428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1163428

Huang, F. (2017). Who leads China’s leading universities? Studies in Higher Education, 42(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1034265

Huang, I.-S. (1983). China’s renewed battle against male chauvinism. China Report, 19(4), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/000944558301900403

Jian, H., & Mols, F. (2019). Modernizing China’s Tertiary Education Sector: Enhanced Autonomy or Governance in the Shadow of Hierarchy? The China Quarterly, 239, 702–727. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741019000079

Jiang, Q. (2018). Sexual harassment in China. Retrieved December 6, 2022, from https://theasiadialogue.com/2018/01/29/sexual-harassment-in-china/

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Fröjd, S., & Marttunen, M. (2016). Sexual harassment victimization in adolescence: Associations with family background. Child Abuse & Neglect, 56, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.04.005

Klein, L. B., & Martin, S. L. (2021). Sexual Harassment of College and University Students: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019881731

Klemmer, K., Neill, D. B., & Jarvis, S. A. (2021). Understanding spatial patterns in rape reporting delays. Royal Society Open Science, 8(2), 201795. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201795

Koçtürk, N., & Bilginer, S. Ç. (2020). Adolescent sexual abuse victims’ levels of perceived social support and delayed disclosure. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105363

Lei, Z. (2011). Can official rank standard affect individuals’ behavior in China? –A framing effect investigation. Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://excen.gsu.edu/docs/Zhen%20Lei_11.15.2011.pdf

Li, L., Lai, M., & Lo, L. N. K. (2013). Academic work within a mode of mixed governance: Perspectives of university professors in the research context of western China. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14(3), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-013-9260-2

Li, M. N., Zhou, X., Cao, W., & Tang, K. (2022a). Sexual assault and harassment (SAH) victimization disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual Chinese youth. Journal of Social Issues, 79(4), 1325–1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12511

Li, P., Cho, H., Qin, Y., & Chen, A. (2021). #MeToo as a connective movement: Examining the frames adopted in the anti-sexual harassment movement in China. Social Science Computer Review, 39(5), 1030–1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320956790

Li, X., Gu, X., Ariyo, T., & Jiang, Q. (2022). Understanding, Experience, and Response Strategies to Sexual Harassment Among Chinese College Students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3–4), 2337–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221101183

Li, Y., Chen, M., Lyu, Y., & Qiu, C. (2016). Sexual harassment and proactive customer service performance: The roles of job engagement and sensitivity to interpersonal mistreatment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.02.008

Li, Z., & Zheng, Y. (2022). Blame of Rape Victims and Perpetrators in China: The Role of Gender, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Situational Factors. Sex Roles, 87(3–4), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01309-x

Liao, Y., Liu, X.-Y., Kwan, H. K., & Tian, Q. (2016). Effects of sexual harassment on employees’ family undermining: Social cognitive and behavioral plasticity perspectives. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(4), 959–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9467-y

Lin, L., & Wang, S. (2022). China’s higher education policy change from 211 project and 985 project to the double-first-class plan: Applying Kingdon’s multiple streams framework. Higher Education Policy, 35(4), 808–832. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-021-00234-0

Liu, L. (2024). Supreme People’s Procuratorate: In the first half of the year, 22,000 people were prosecuted for crimes violating women’s rights, such as rape and molestation.(最高检: 上半年起诉强奸、猥亵等侵害妇女权益犯罪2.2万人). Thepaper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_28321982

Suzhi expectations for double-shouldered academics in Chinese public universities: An exploratory case study. (2014). Journal of Chinese Human Resources Management, 5(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHRM-07-2014-0019

MacKinnon, C. A. (1979). Sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination (Vol. 19). Yale University Press.

Minnotte, K. L., & Legerski, E. M. (2019). Sexual harassment in contemporary workplaces: Contextualizing structural vulnerabilities. Sociology Compass, 13(12), e12755. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12755

Mou, Y., Cui, Y., Wang, J., Wu, Y., Li, Z., & Wu, Y. (2022). Perceiving sexual harassment and #metoo social media campaign among Chinese female college students. Journal of Gender Studies, 31(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1884848

Parish, W. L., Das, A., & Laumann, E. O. (2006). Sexual harassment of women in urban China. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(4), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9079-6

Pei, X., Chib, A., & Ling, R. (2022). Covert resistance beyond #Metoo: Mobile practices of marginalized migrant women to negotiate sexual harassment in the workplace. Information, Communication & Society, 25(11), 1559–1576. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1874036

ProPublica. (2017). Trump administration hires official accused of sexually assaulting students. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/trump-administration-hires-official-accused-of-sexually-assaulting-students_n_590b237de4b02655f844b9ae#

Qing, S. (2020). Gender role attitudes and male-female income differences in China. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 7(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-020-00123-w

Qiu, G., & Cheng, H. (2022). Gender and power in the ivory tower: Sexual harassment in graduate supervision in China. Journal of Gender Studies, 32(6), 600–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2022.2138839

Richards, T. N. (2019). No evidence of “weaponized Title IX” here: An empirical assessment of sexual misconduct reporting, case processing, and outcomes. Law and Human Behavior, 43(2), 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000316

Richards, T. N., Gillespie, L. K., & Claxton, T. (2021). Examining incidents of sexual misconduct reported to Title IX coordinators: Results from New York’s institutions of higher education. Journal of School Violence, 20(3), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2021.1913599

Robbins, I., Bender, M. P., & Finnis, S. J. (1997). Sexual harassment in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(1), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025163.x

Rosenthal, M. N., & Freyd, J. J. (2022). From DARVO to distress: College women’s contact with their perpetrators after sexual assault. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 31(4), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2022.2055512

Shi, X., & Zheng, Y. (2020). Perception and tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of feminist identity, sexism, and gender roles in a sample of Chinese working women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684320903683

Shi, X., & Zheng, Y. (2021). Feminist active commitment and sexual harassment perception among Chinese women: The moderating roles of targets’ gender stereotypicality and type of harassment. Sex Roles, 84(7–8), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01180-8

Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). Institutional betrayal. American Psychologist, 69(6), 575–587. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037564

Tang, C. S., Yik, M. S. M., Cheung, F. M. C., Choi, P., & Au, K. (1996). Sexual harassment of Chinese college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 25(2), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02437936

Wamoyi, J., Ranganathan, M., Mugunga, S., & Stöckl, H. (2022). Male and female conceptualizations of sexual harassment in Tanzania: The role of consent, male power, and social norms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(19–20), NP17492–NP17516. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211028309

Wang, X., & Vallance, P. (2015). The engagement of higher education in regional development in China. Environment and Planning c: Government and Policy, 33(6), 1657–1678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614143

Wang, Y., & Hua, L. (2020). Birth influences future: Examining discrimination against Chinese deputy mayors with grassroots administration origins. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00572-1

Xie, Z. (1994). Regarding men as superior to women: Impacts of Confucianism on family norms in China. China Population Today, 11(6), 12–16.

Xin, J., Chen, S., Kwan, H. K., Chiu, R. K., & Yim, F. H. (2018). Work–family spillover and crossover effects of sexual harassment: The moderating role of work–home segmentation preference. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(3), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2966-9

Xu, J., & Zhang, C. (2022). Sexual harassment experiences and their consequences for the private lives of Chinese women. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 8(3), 421–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X221105717

Ying, C. (2011). A Reflection on the Effects of the 985 Project. Chinese Education & Society, 44(5), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932440502

Ying, Q., Fan, Y., Luo, D., & Christensen, T. (2017). Resources allocation in Chinese universities: Hierarchy, academic excellence, or both? Oxford Review of Education, 43(6), 659–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1295930

Zeger, S. L., & Liang, K.-Y. (1986). Longitudinal Data Analysis for Discrete and Continuous Outcomes. Biometrics, 42(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.2307/2531248

Zeng, J. (2020). #MeToo as connective action: A study of the anti-sexual violence and anti-sexual harassment campaign on Chinese social media in 2018. Journalism Practice, 14(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1706622

Zeng, L.-N., Lok, K.-I., An, F.-R., Zhang, L., Wang, D., Ungvari, G. S., Bressington, D. T., Cheung, T., Chen, L., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2020). Prevalence of sexual harassment toward psychiatric nurses and its association with quality of life in China. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 34(5), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2020.07.016

Zeng, L.-N., Zong, Q.-Q., Zhang, J.-W., Lu, L., An, F.-R., Ng, C. H., Ungvari, G. S., Yang, F.-Y., Cheung, T., Chen, L., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2019). Prevalence of sexual harassment of nurses and nursing students in China: A meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 15(4), 749–756. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.28144

Zhu, H., Lyu, Y., & Ye, Y. (2019). Workplace sexual harassment, workplace deviance, and family undermining. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 594–614. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0776

Zong, X., & Zhang, W. (2019). Establishing world-class universities in China: Deploying a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the net effects of Project 985. Studies in Higher Education, 44(3), 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1368475

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the reviewers and editors for their invaluable comments and meticulous editing. Their insightful feedback and suggestions have greatly enhanced the quality of our work. We deeply appreciate their dedication and effort in improving our manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Young Innovative Talents Project of Colleges and Universities in Guangdong Province (2023WQNCX120) and School-level Research Projects of Nanfang College · Guangzhou (2021XK03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LH was primarily responsible for study conceptualization, data analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. LT provided comprehensive editing and refinement of the manuscript. HC, ZG, WC, YW, RD, WH, JZ and SW collected and organized the data. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article