Abstract

Economic coercion is a form of intimate partner violence (IPV) that is distinct from but often co-occurs with physical, psychological, and sexual IPV. Women’s experiences of economic coercion are understudied in low- and middle-income countries, despite increases in women’s economic opportunities in these settings. Bangladesh is a salient site to understand how women experience, interpret and give meaning to economic coercion because historical gender inequalities in access to economic opportunities and resources are changing in favor of greater participation of women in economic activities. We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 24 married women aged 19–47 years to understand their experiences of economic coercion with respect to their involvement in income-generating activities in rural Bangladesh. Overall, we found that women’s experiences of economic coercion were multi-dimensional, and influenced by women’s participation in income-generating activities. In this setting, three major domains of economic coercion by husbands emerged from women’s narratives: denial of access to income-generating activities, coercive control over resources, and economic neglect. Furthermore, participant narratives reflected the continued influence of the patriarchal family system, and the gendered power relations therein, on women’s experiences of economic coercion, despite increases in women’s involvement in income-generating activities. Our results suggest that women’s experiences of economic coercion influence their participation in income-generating activities in Matlab, Bangladesh. Interventions to increase women’s economic opportunities should consider the barriers and potential repercussions of women’s involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Women’s Income-generating Activity and Experiences of Economic Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Bangladesh

Economic coercion comprises one form of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women, alongside physical, psychological and sexual violence (Postmus et al., 2016; Yount et al., 2016). Western scholars define spousal economic coercion, also known as economic intimate partner violence, as any implicit or explicit strategy to control the ability of a spouse or partner to acquire, use or maintain economic resources (Adams et al., 2008). Economic coercion may take the form of overt demonstrations of power in the marital dyad to inhibit access to economic activities, or manifest as conflict related to backlash over participation in economic activities. Economic coercion also may reflect latent forms of marital power dynamics by which a partner forgoes participation in economic activities to avoid anticipated conflict. Economic coercion is a prevalent but distinct type of IPV, which is positively associated with other types of IPV (Stylianou et al., 2013; Yount et al., 2016). Despite their prevalence, women’s experiences of economic coercion are understudied in low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) (Fawole, 2008; Yount et al., 2016). This limited evidence is the case in Bangladesh, where women’s historical disadvantages in economic opportunity and resources are shifting toward their greater participation in economic activities (Rahman & Islam, 2013), even while rates of intimate partner violence remain high (Naved, Mamun, et al., 2018; Naved, Rahman, et al., 2018; Sambisa et al., 2011).

Historically, family systems in Bangladesh have been strongly hierarchical, reflecting patterns of classical patriarchy (Kandiyoti, 1988). Men have been expected to serve as the main financial providers and to interact with the wider community; whereas women have been expected to contribute unpaid and undervalued domestic and reproductive labor in the home, often under seclusion or with restrictions to their freedom of movement (Cain et al., 1979; Schuler et al., 1996). In recent years, the historical system of classic patriarchy has eroded to some extent, with increases in women’s employment (Naved, Rahman, et al., 2018; Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al., 2021; Yount, Cheong, Miedema, et al., 2021). However, research is limited on how women’s increased access to economic opportunities may influence their experiences of economic coercion, as a distinct form of IPV.

In this context, our study aims to examine married women’s experiences of economic coercion with respect to their income generation in rural Bangladesh. This study fills an important gap in the scientific literature on patterns of economic coercion in a society where gender relations within the family system and women’s broader participation in the economy are undergoing dramatic change.

Background

Economic Coercion

Economic coercion is an understudied form of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Fawole, 2008; Postmus et al., 2016; Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al., 2021; Yount, Cheong, Miedema, et al., 2021). Economic coercion is distinct from but may co-occur with physical, psychological and sexual IPV (Stylianou et al., 2013; Yount et al., 2016). Specifically, alongside acts of physical, sexual and psychological IPV, perpetrators may deploy economically coercive tactics to control their partners’ economic independence, making them more vulnerable to other forms of IPV. Economic coercion manifests in multiple ways, including denial of access and interference with employment, financial surveillance and control over resources, and financial exploitation and sabotage (Adams et al., 2008; Postmus et al., 2016; Yount et al., 2016). Experiences of economic coercion or other forms of IPV have been shown to diminish women’s self-perceptions of financial independence (Postmus et al., 2012), although some women may respond strategically to partner violence by increasing their economic activity and financial safety net (Yount et al., 2014).

In rural Bangladesh, husband’s economic coercive control over their wives is prevalent. Nearly one in five (or 18%) men report perpetration of economic coercion against their spouse (Naved et al., 2011). The most common form of economic coercion reported by husband’s is taking their wives earnings against her will (13%), followed by prohibiting the wife from working (9%), throwing the wife out of the house (7%) and keeping money for oneself even if his wife could not afford household expenses (3%) (Naved et al., 2011). These indicators reflect the current global practice of measuring economic IPV. However, extant measures may not capture the full spectrum of women’s experiences of economic IPV (Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al., 2021; Yount et al., 2016). As an example, using a recently validated, comprehensive 36-item scale of economic coercion in rural Bangladesh, Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al. (2021) and Yount, Cheong, Miedema, et al. (2021) estimated that 62% of ever-married women experience economic coercion in their lifetime.

Gendered Family and Economic Systems in Flux

The Bangladeshi family historically reflects a “classically patriarchal” system, characterized by patrilocal extended households in which men are dominant and women hold little autonomy (Kandiyoti, 1988). Aligning with classically patriarchal kinship practices, women are married early, transition to their husband’s household, and are expected to be subservient to their husbands and in-laws (Cain et al., 1979). Historically, the legal and customary ‘guardianship’ of women passes from father to husband. Under these conditions, women’s acquiescence to these family hierarchies pays dividends as they age, particularly if they produce sons (Kandiyoti, 1988). Over the life cycle, women gain some authority over ‘junior’ family members, albeit at the expense of reproducing the cyclical gender inequalities that they faced as young brides (Kandiyoti, 1988).

Historically, the gendered organization of work in Bangladesh defined work outside the house for pay as the domain of men. In contrast, women’s work was normatively confined to unpaid domestic and care work, including childcare and household management (Cain et al., 1979; Schuler et al., 1996). In this system, women were dependent on male guardians for financial security. In cases of deceased, absent or abusive guardians, women became vulnerable to economic hardships, such as increased poverty, or other forms of abuse (Cain et al., 1979; Kabeer, 2011). Furthermore, women experienced spatial segregation and restricted mobility through the practice of purdah (Cain et al., 1979). This practice prevented women from seeking work outside of the home compound, and constrained their work to expenditure saving activities on behalf of the family, for which they may not receive or control remuneration (Kabeer, 2001; Kibria, 1995).

However, since the 1980s, expanding export and local market economies (e.g., the burgeoning garment industry), alongside poverty-alleviation programs targeted at women, have increased women’s opportunities to participate in income-generating activities (Heath, 2014; Kabeer & Mahmud, 2004; Salway et al., 2005). Here, we use the term income-generating activities to include all types of women’s work, irrespective of location, seasonality or time-allocation, for which women receive monetary or in-kind remuneration (Kabeer, 2016; Mahmud & Tasneem, 2011; Salem et al., 2018). In doing so, we seek to make visible the productive contributions that women make to their local economies (Langsten & Salem, 2008). The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics reports that 36.3% of women participated in the labor force from 2016–2017 (with labor force participation defined as individuals above age 15 who were involved in work for wage or family gain in the past seven days) (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2018). In 2012, 35 million borrowers in Bangladesh, 90% of whom were women, were covered by microcredit programs compared to 11 million in 2004 (Rahman & Islam, 2013). Women’s employment in the garment industry, in particular, has risen dramatically since the 1990s, with a period of particularly high growth from 2005 to 2010 (Rahman & Islam, 2013). Women increasingly migrate to urban centers for income-generating activities, leaving families behind in rural areas (Kabeer & Mahmud, 2004). This growth in income-generating opportunities for women in Bangladesh and other classical patriarchal settings raises questions over how such growth may alter women’s risk of exposure to economic and other forms of IPV (Kabeer, 2016; Salem et al., 2018).

Effects of Women’s Work on Exposure to IPV

Studies yield mixed results on whether increased workforce participation and access to economic resources have positively or negatively affected women’s empowerment and freedom from IPV (Kabeer, 2016; Naved, Mamun, et al., 2018; Schuler & Nazneen, 2018) and whether women’s work challenges or reinforces patriarchal family systems (Kibria, 1995; Schuler et al., 2017). This literature largely focuses on the effects of women’s economic empowerment on their risk of physical and/or sexual forms of IPV. In some studies, women’s involvement in income-generating activities, such as paid work or involvement in microfinance programs, is associated with reductions in exposure to physical or sexual IPV (Dalal et al., 2013; Salway et al., 2005; Schuler et al., 1996). These reductions in IPV risk may be a result of women’s expanded social networks through work or program participation, as greater social relationships make formerly private acts of violence public (Kabeer, 2016; Schuler et al., 1996). Further, women’s participation in work may expand their social networks and capacity to act collectively with other women (Sultana, 2013). Women’s economic contributions to the household also may reduce pressure on men to provide for the family, particularly in low-resource settings. Poor men may be unwilling to alienate wives who bring economic resources into the household (Kabeer, 2016).

Alternatively, other research finds that women's involvement in income-generating activities and ownership of economic assets are associated with greater risk of IPV (Bates et al., 2004; Heath, 2014; Naved & Persson, 2005). A prevailing theoretical explanation is that wives who deviate from gender norms around work, mobility and control over economic resources, face retaliatory violence from husbands who seek to reassert control (Vyas & Watts, 2009). For example, garment workers who owned household assets and resources, such as jewelry or savings, reported higher rates of IPV compared to peers who owned less (Naved, Mamun, et al., 2018). The authors speculate that greater resource ownership may trigger marital conflict over control and ownership of these assets (Naved, Mamun, et al., 2018).

Another study, conducted across 60 villages in Bangladesh, found that women who work for pay face increased risks of IPV, although this association was significant only among women with lower schooling attainment and a younger age at time of marriage (Heath, 2014). In such cases, women’s pre-marital resources, such as pre-marital education and later age at time of marriage, may have elevated her bargaining power and mitigated against potential backlash when she deviated from normative expectations. Women who earn income also may act strategically in other domains of their lives to reduce the perception of transgressing norms in an effort to mitigate risk of IPV (Schuler et al., 2017), or use economic resources to leverage their position within existing patriarchal systems (Naved, Rahmen, et al., 2018). For example, women who perceive personal advantages within the male-headed “traditional” family structure may be more likely to give up control over their income, in order to benefit from the economic security promised by compliance with patriarchal gender norms within the family system (Kibria, 1995; Naved, Rahmen, et al., 2018).

Summary and Objectives

In sum, women’s expanding economic opportunities in Bangladesh may affect positive change in some cases, even while entrenched constraints inhibit change or generate backlash in other dimensions (Kabeer, 2016). Situational factors, such as women’s pre-marital resources (Heath, 2014), local values and cultural norms (Koenig et al., 2003; Schuler & Nazneen, 2018), and community level characteristics (Rahman et al., 2020; Schuler et al., 2017) may moderate the associations between women’s income-generating activities and risk of IPV. With some exceptions (Naved, Mamun, et al., 2018), this literature focuses largely on the connection between women’s economic empowerment and their experiences of physical and/or sexual forms of IPV. Less is known about how women’s participation in income-generating activities may influence their experiences of economic coercion, as a distinct, yet related type of IPV. In the present study, we aim to address this gap and seek to understand variations in women’s experiences of economic coercion among earning and non-earning women in a context where structural opportunities for women have expanded even while inequitable gender norms remain salient. Specifically, we examine the following research questions: What types of economic coercion occur in marital relationships with respect to women’s income generation (RQ1); How do women describe and understand these experiences (RQ2); and How do women’s experiences of economic coercion vary based on their income-generating activities (RQ3)?

Method

Study Design

This qualitative study was part of a parent study, entitled “Intimate Partner Coercion and Implications for Women’s Health and Well-being.” The parent study employed a sequential mixed-methods design to develop a validated measure of economic coercion in rural Bangladesh. The first stage used qualitative data to explore how married men and women describe, assess and understand economic coercion against wives. The qualitative data then informed the development and psychometric validation of a multi-dimensional economic coercion scale, published elsewhere (Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al., 2021; Yount, Cheong, Miedema, et al., 2021). In this article, we analyze the qualitative data from the first stage of the study to understand women’s experiences of economic coercion, both related to and independent of their involvement in income-generating activities.

Study Site

The study was conducted in Matlab, an upazila (sub-district), approximately 55 km southeast from Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Matlab has approximately 240,000 residents, and is the site of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b)’s Health and Demographic Surveillance Site (HDSS), one of the longest-running population surveillance systems in the developing world (icddr,b, 2020). This site was chosen for the study to facilitate selecting the survey sample from the HDSS, as well as capturing diverse economies across the embankment (discussed below). Matlab’s geography, economy, and society are typical of the rural delta region of Bangladesh. The mean age at first marriage is 19 years for women, compared to 27.6 years for men (icddr,b 2020). In 2014, approximately 51 percent of households owned agricultural land (icddr,b, 2016). However, the primary source of household income in this region is through remittances, or foreign earned income, which is transferred to family members. Remittances are the primary source of household income for 33% of households,, with agriculture only serving as the primary source of income for 8% of the population (icddr,b, 2016).

Participant Recruitment

Women were eligible for the study if they were married and between the ages of 15 and 49 years old. Participants were recruited from within and outside the Matlab embankment, a topographical feature that contributes to distinctive climates and economic markets on either side. Specifically, the area outside of the embankment is prone to floods and therefore has fewer crops compared to the area inside. We used purposive sampling to recruit a diverse sample of women in relation to key strata relevant to the research purpose (e.g., age, length of marriage, husband’s migration status, income-generating activities, and NGO membership). Interviewers coordinated with local health researchers affiliated with icddr,b to identify villages that would be suitable for data collection (e.g., adequate number of women involved in income-generating activities). After arriving in the village, interviewers spoke with women and men in these villages to identify potential participants.

Data Collection

Data were collected using a semi-structured in-depth interview guide, which provided a flexible approach to capture women’s personal narratives and experiences related to economic activities and economic coercion. The guide included questions on women’s involvement in, or perceptions of, work and earnings, loans and microcredit, and dowry practices. The study team developed the guide in English, with guidance on the study context from Bangladesh team members. The English guide was then translated into Bengali and piloted among 4 women by icddr,b team members. The pilot interviews sought to identify any errors or issues with the interview process prior to implementing the study in the field. Based on feedback from the pilot participants, we refined questions for clarity, as well as added and dropped items where relevant. The final guide was back translated into English to check that the intended meaning of each question was preserved across the translation process. The study received ethical approval from Emory University’s Institutional Review Board (#00,097,428) and icddr,b’s Institutional Review Board (PR-17077).

Data were collected in March and April 2018 with 24 married women. Two female Bangladeshi interviewers conducted the interviews, under the supervision and guidance of icddr,b staff. Both interviewers held Masters degrees in Anthropology. Interviewers conducted the interviews in women’s homes, or in the homes of neighbors where women felt comfortable and where the interview could be conducted in private. The final sample of participants ranged in age from 19 – 47 years (see Table 1 for sample characteristics).

Informed oral consent was obtained from all participants. Upon receiving consent, interviews were audio recorded and lasted an average of 75 min. Each interviewer wrote field notes to document recruitment processes and general observations of each interview. The data-collection team reviewed field notes and experiences daily to initiate an iterative process of data collection and to resolve issues or challenges.

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated from Bengali into English. Each translation was reviewed by an icddr,b team member, who had overseen the data collection process. An Emory team member also reviewed translations, and unclear translations were checked against the original Bengali language transcripts. Data comprised 24 verbatim transcripts of the in-depth interviews. Transcripts were entered into MAXQDA 18 software package in order to facilitate coding and data analysis. Data were read closely by team members to identify a range of relevant themes that were listed in a codebook. Code development was done in collaboration with in-country partners to ensure cultural nuances were captured. We developed inductive codes directly from reviewing data and team members from icddr,b ensured that the codes adequately captured cultural nuances in the issues raised. The codebook provided a central reference for all codes that were applied in the entire data set. A single lead researcher coded the majority of the transcripts. A second researcher assisted in quality checks of coding through an inter-coder agreement process. Inter-coder agreement was assessed by coding randomly selected transcript segments (approximately 10% of the transcripts) and comparing the consistency between the coders. Discrepancies in coding were resolved and amendments made to the codebook and coding practices before coding the entire data set. A third coder, as part of her MPH training, supported coding toward the end of the project, under the close supervision and mentorship of the lead coder.

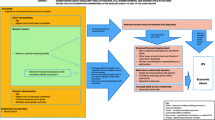

We used grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) to identify normative constructs to inform the development of a theoretical framework of women's economic coercion as it related to their participation in income-generating activities in rural Bangladesh. First, we conducted a descriptive analysis of coded segments, to identify core themes around women’s experiences of economic coercion. As themes and patterns emerged, the research team discussed negative cases that would require us to expand and/or refine our themes to incorporate the full range of women’s experiences. We compared experiences in economic coercion by husband’s migration status, socio-economic status and location of residence within or outside the embankment. Throughout the analysis, the lead author conducted memo writing in order to generate ideas and document the engagement with the data throughout the analytic process. During weekly team meetings, the lead author would present updates on data analysis, as well as questions around interpretation. We discussed possible perspectives through which to interpret our results, and Bangladesh team members guided these discussions to ensure that we situated and interpreted women’s narratives in light of the social context of Bangladesh. Results of our data analysis and interpretation were used to develop a conceptual diagram to organize and differentiate the types of economic coercion and their inter-relationships that emerged from the data on income-generating activities in the sample. The diagram was further refined to consolidate and categorize experiences into broader groupings of economic coercion experiences (Fig. 1).

Results

Our analysis revealed that women’s experiences of economic coercion were multidimensional, and women’s exposure to different forms of economic coercion varied based on access to and participation in different types of income-generating activities. Figure 1 provides a conceptual summary of the results. We identified three separate conceptual domains of economic activity within which women experienced economic coercion by their husband: access to income-generating activities (Domain 1), control of income and household spending (Domain 2), and the financial contributions of husbands to the household (Domain 3). Each domain represents a continuum of coercion from less to more coercive activity – the nature, context and level of coercion differs at each level and is depicted by the nodes along each continuum within each domain. Figure 1 also shows how women’s experiences of coercion are patterned by their level of economic activity, depicted by the shading on the nodes (e.g., economically active or inactive).

Although Fig. 1 depicts economic coercion as linear and discrete categories, women’s experiences were complex and multifaceted. Women could experience coercive behavior in one economic domain (e.g., access to income-generating activities), while experiencing no coercion in another economic domain (e.g,. control of household income). Alternatively, women could experience one type of economic coercion at one point of their lives (e.g,. denial of access to income-generating activities during pregnancy) that is not experienced later (e.g., woman works after children are grown). Thus, the nodes serve to organize different types of coercion within each economic domain, and represent groups of experiences rather than categories of women. The nodes reflect dynamic, rather than static, experiences of coercion within the economic domains of women’s lives and across their life course. Therefore, we are unable to categorize or quantify participants into any one discrete domain.

Overall, women’s participation in the formal economic sector was low, with the majority of participants engaged in subsistence work or in the informal sector. Among those who did participate in the formal employment sector, participants described working in garment factories, insurance companies as field staff, or school teachers or small business owners (e.g., pharmacy owner). In the informal sector, participants described conducting a range of economic activities in the home, such as teaching or tutoring children, poultry rearing, making handicrafts, or tailoring, as well as economic activities conducted outside the home, such as wage or day labor jobs. The majority of participants did not report full-time employment. Rather, they engaged in income-generating activities during part of their day, and engaged in household labor for the remaining portions of the day. Table 1includes a description of women’s economic activities, and classifies women as currently, previously or never economically active.

Domain 1: Access to Income-generating Activities

The first domain reflects women’s access to income-generating activities (see Fig. 1). In this domain, husband’s denial of his wife’s access to income-generating activities, or harassment of wives who did engage in work, emerged as key forms of economic coercion. Across the sample, women commonly described their husband as the primary arbitrator of whether or not they participated in any remunerated work, or work for cash or in-kind. Thus, women’s access to income-generating activities was dependent on their husband’s permission. The importance of husband’s permission with respect to their wife’s access to income-generating activities in Bangladesh was reflected in women’s descriptions of participating (or not) in economic activities. Within Domain 1, we found that women described their interactions with husbands in one of three ways, which we organized into three nodes: (A) husband supported or facilitated their access to income generating work; (B) husband challenged their access to income generating activities; or (C) husband either explicitly or implicitly prevented their access (see Fig. 1). Within each node, different types of support, challenges or barriers were reported. These groups of experiences were also not mutually exclusive. As discussed below, women experienced varying levels of support and restriction or control from their husbands with respect to work across the life course, and across different types of work.

Node A: Husband Supports or Facilitates Access to Income-Generating Activities

One node of experience within Domain 1 reflected husband’s supporting or facilitating their wives access to income-generating activities. Even though women described their husbands as supportive, women still perceived the permission of their husbands as a requirement to being able to work. Permission, thus, became a condition under which women experienced support from their husbands to work, and seeking permission to work was a common practice reported by women. As one 30-year old woman, who was classified as extremely poor, described: “I am working now as everyone supports me…if my husband thinks it will be good for me or beneficial for the family…if he understands, then I can do it” [Married Woman (MW) #6].

Another 27-year old, middle class, woman noted: “I have to take permission in case of any other work I want to do. It is not possible to go without permission. I don’t know how he [husband] would react” [MW #16].

These quotes underscore that a husband’s permission is perceived as a basic requirement for wives to access income-generating opportunities. As we see in the first quote – and describe in detail later – a husband’s permission was often conditional on the type or perceived benefits of economic activity. Women also described concerns for the quality of their relationship, should they transgress expectations of seeking permission to work from their husband, despite the changing social norms around women’s participation in economic activities. For example, a 44-year-old wealthy participant reflected on societal changes in women’s participation in employment:

These days there is no difference between boys or girls, as far as working is concerned. They work equally. There is no way to consider it as bad. The girls couldn’t work in the old times but that’s not the case anymore. [MW#14]

At the same time, she hesitated to imagine a hypothetical situation in which she would not seek permission from (referred to below as “informing”) her husband. She said: “According to me, it’s better to inform him and then go [to a new job]…[if I didn’t] maybe he would demand to know why I didn’t inform him” [MW#14]. In this quote, the phrase “inform him” is interpreted as informing and getting permission. In some cases, not receiving permission from husbands was perceived as a risk for IPV or cause of deterioration of the relationship. A 44-year old wealthy class participant observed: “If I don’t listen to my husband, it would eventually damage our loving relationship. The relationship might deteriorate” [MW #14]. Another 22-year old middle class woman explained how not seeking permission before she engaged in income-generating activities could initiate violent conflict:

He forbade me to go anywhere without asking his permission and said, ‘you will ask me before going. In case of giving permission, I will say you to go there.’ If I go without permission, then he will become angry…he would give two slaps or will beat once or twice with a stick. [MW #19]

Given the high levels of migration among men in Matlab, some women’s husbands were not present to permit or to prohibit their wives from participating in economic activities. In some of these cases, other family members served as a proxy for absent husbands, and women obtained permission from these family members. In other cases, women remained in touch with their husbands via telephone, and obtained permission directly from absent husbands over the phone. These experiences, thus, underscore the perceived importance of permission from a husband or proxy authority before participants could engage in any economic activities.

Once permission was received, women’s descriptions of their husband’s support could be classified as active, emotional or passive support. Women’s discussions of active support from their husbands included his encouragement to apply for work positions or degree programs, his assistance with job applications, or his purchase of necessary equipment for women’s economic activities. Active support, thus, involved some level of participation or facilitation by a husband with respect to his wife’s involvement in income-generating activities, In this low-resource setting, husbands’ active support of their wives participation in remunerated work was sometimes discussed in terms of financial gain to the family. Women reported that their families acknowledged the benefits of added income for the family. Even in cases when the household’s economic security had been attained – and thus the financial impetus for women’s labor was no longer present – husbands continued to support their wife’s economic activities as it brought additional resources to the household to which they had grown accustomed. Women also expressed a desire to participate in economic activities, and reported that their husbands actively supported their desire, for example, through the purchase of sewing machines to enable women to do tailoring work, or by supporting applications to higher education.

Women also described their husbands providing emotional support for their work, although not playing an active role. Emotional support was described in terms of affirmation of their work. Emotional support was also perceived as the absence of prohibitive barriers or harassment about their income-generating activities. Affirmative emotional support from husbands often stood in contrast to criticism from other people in the community (e.g., in-laws or neighbors) who were critical of women’s work, as it deviated from prevalent social norms for women’s roles. For example, a 33-year-old upper middle-class woman, who had been married for 11 years, worked as a religious teacher or tutor. Her husband, a community religious leader, supported her work despite opposition from his family and the broader community. Her in-laws would have preferred that she remained at home, and in some villages, she was forced to stop tutoring due to criticism from neighbors of the families that she taught. However, as the woman described, her husband continued to support her work in the face of opposition:

My [husband] also supports me. He is a very good person. He allows me to do everything…he hasn’t prohibited me any time…He never stops me…. He never interrupted my education, and also never said any negative things about my job. He also doesn’t oppose me in earning. [MW #5]

In this example, the participant describes her husband’s emotional support (never saying negative things), as well as the lack of barriers to work (hasn’t prohibited her), thereby illustrating the husband’s dual role as gatekeeper and support system.

Another type of support described was passive support from the husband, in which husbands neither promoted nor prohibited their wives from income-generating activities. Women described their husbands’ passive support as a general lack of engagement with, or indifference to, their decision to work or not work. In some cases, this passive acceptance was construed by women as a sign of a husband’s respect for his wife’s ability to make choices related to her own economic activities and time use. In other cases, men displayed some curiosity around motivations to work, but did not inhibit women’s ability to engage in economic activities.

Overall, husbands played a central, permission-granting, role in enabling their wives’ access to income-generating activities. In general, participants who experienced the least constraints to income-generating activities described their husbands as supportive of their income-generating activity.

Node B: Husband Challenges Access to Income-Generating Activities

The second node of experiences within Domain 1 reflected challenges to their wives’ access to income-generating activities by husbands. As illustrated in Fig. 1, even women who reported challenges from their husband still participated in some form of income-generating activity. In other words, husbands created barriers to women’s access, but women were able to overcome these barriers to participate in income-generating work. The primary way in which husbands interfered with wives’ income-generating opportunities was by imposing conditional access to income-generating activities. In these cases, women received permission from husbands to work only if certain financial and non-financial conditions were met.

For many women in this low-resource setting, conditional permission to work was influenced by financial need within the family. Concerns around impending poverty tended to override objections about women’s transgression of dominant norms around work and labor. Women themselves often were central in these discussions within the family. A husband’s active support, as described above, was absent here. Instead, women used the household’s precarious financial situation as leverage to negotiate their participation in income-generating activities. Although a husband’s permission was the primary enabling factor, women also discussed the influence of in-laws and other family members in the process of negotiating their access to work. As one 27-year-old middle-class participant reported:

My husband was against it [her working in a garment factory] at first. He said that I don’t need a job. But later I realized that job is a must for us. My husband earns very little, plus we have two kids to feed…That is why I decided to take the job…I insisted every day to convince him…I said that I want to go [work]. Everyone is working, so what’s wrong if I do that too?…These are the things I told him. Then one day he agreed and gave me permission. [MW #16]

Notably, the participant justified her participation in paid work with her perceptions of greater access to paid labor among women in Bangladesh, suggesting that women’s advancement into economic activities in urban Bangladesh may be used as leverage in individual negotiations within the household.

Women’s ability to participate in income-generating activities also was conditional on non-financial factors. These included whether work activities involved interactions with strangers, took place within or outside the home, or interfered with household tasks and family care work. In the context of rural Bangladesh, where women’s freedom of movement is restricted, certain types of remunerated work were perceived to challenge norms around women’s movement by enabling women to leave the house. A major concern raised was that leaving the home created the potential for contact with non-family members, particularly men. Women’s travel outside the home, or potential interactions with non-relative men, was described as potentially damaging to the husband’s (or family’s) reputation. The risk of interaction with men who were not related to their wives was described as a driving motivation for husbands to deny their wives permission to participate in economic activities outside the home. In these cases, the added financial benefit of women’s income did not override normative social pressures for women to remain at home. When women were denied access to remunerated work outside the home, they often participated in income-generating activities at home such as raising and selling poultry and/or livestock. One 22-year-old middle-class woman described her husband’s objections to working as a helping hand at a crèche during one of her pregnancies:

He said ‘no, you cannot do this work. You may fall down and the pregnancy may be in danger. Who will then bear the loss? It’d be my loss and I’ll have to bear the burden’ …This is how he convinced me and kept me [at home]… He doesn’t like that I do a job…He’d say [explaining the reason], ‘when you go somewhere you have to speak with a man and meet a man. [MW #19]

At the time of the interview, due to constraints on her access to work outside the home, the participant sold poultry from her house. This work was considered an acceptable form of income-generating activity, as she did not interact with strange men and was perceived to be protected within the home compound. The type and location of economic activity also influenced whether permission to work was given. Women described a gendered division of income generating activity. Some activities, such as poultry rearing, handicraft work, or tutoring were generally considered socially acceptable for women, as these aligned with expectations of women as nurturers of children (via education) and women in the home (involved in home-based economic activities). When these activities took place in the home, women were more often allowed to participate. In cases where these activities (such as tutoring) took place outside of the home, women were less likely to receive permission, due in part to concerns around women’s mobility described above. Other types of labor, such as fieldwork, grazing cattle or livestock agriculture were perceived as men’s work, and not suitable for women. Thus, both the type and location of the economic activity were central to whether or not women would face barriers to access.

However, women’s access to income-generating activities – even within the home – was conditional on their ability to complete unremunerated household labor, including housework, childcare and care of external household members such as in-laws. Often, women themselves became the arbiters of whether or not they could work – or the extent to which they could work – based on whether they could complete their household tasks. As a consequence, lack of time became a key barrier to participating in income-generating activities. As one respondent asked with a smile (noted in the field notes): “Is there any end of work for women” [MW #4]? Women often described engaging in income-generating activities during their “leisure” time or free time. Women who did not have adequate free time due to their household responsibilities often reported that they were unable to participate in income-generating work to the extent that they wished to. In these cases, the primacy of women’s duties as wife and mother created conditions under which participants were unable to take on full-time or even regular part-time income-generating activities. As a 30-year old, extremely poor, woman noted:

When the kids are back from school, I need to bathe and feed them. I can’t give little time to the [sewing] machine then. If I spend much time working then I am not able to give the kids much time. That’s why I take fewer orders. It’s my choice.”…I know what is good for me. I think if I spend my time on my kids rather than other things, they will not be uneducated like me…That’s why I take less workload. [MW #6]

Some women resumed work after pregnancy, or when children became older. A few women acknowledged that the greater contribution of husbands toward domestic labor or childcare could mitigate time constraints to income-generating activities. However, in general, women did not bring up men’s contributions to household labor. Overall, women tolerated conditions on their access to work, describing this acceptance as a way to avoid conflict with their spouse.

However, in some cases, women’s work did generate conflict between husband and wife. Participants described subtle forms of psychological intimidation from husbands related to women’s wage work. Some women did not receive permission to work or to attend trainings, but did so anyway, and reported conflict with their husbands as a consequence. In other cases, participants describe husbands initially giving permission to work, but their wives’ income-generating work created conflict within the couple. Women described such forms of conflict as verbal belittling, intimidation or accusations of prioritizing income-generating activities above family. Some women described this conflict as a result of women not conforming to expectations around women’s mobility or financial autonomy. Other women described intimidation as a result of their husband’s concern for his reputation. If his wife worked, participants suggested, a man’s ability to provide for his family could be called into question, thus undermining his standing in the community. One 36-year old wealthy participant described her husband’s constant challenge to her efforts to seek training in tailoring:

First, he gave his consent [to take tailoring classes]. At that point, he told me, ‘Ok, as you wish.’ I took this permission, first. After that, while I am going out for a couple of days for my sewing lesson … he became angry and asked me from whom I took the permission to go outside? Then I told him, ‘Why? You forgot that you give your permission to go and learn. So, what happens now? I did not go outside without your permission; I went with your permission….’ [but] he does not like that I frequently go outside from the house, or going somewhere for visit. [MW #11]

Node C: Husband Inhibits Access to Income-Generating Activities

The third node of experiences within Domain 1 reflected instances in which husband’s inhibited or prohibited women’s access to income-generating activities. Participants who did not participate in income-generating activities described situations reflecting implicit or explicit denial of access from their husbands. Explicit denial of access included situations in which women either did not receive permission to participate in income-generating activities and thus did not do so, or received permission to work conditional on completing housework duties but were unable to do both. When women discussed not receiving permission to work, or not seeking permission to work, they often invoked the primacy of their responsibilities as wives and mothers. In some cases, husbands explicitly stated women’s household responsibilities or children’s wellbeing as a reason for not giving permission to participate in an economic activity. For example, a 31-year old extremely poor women, who had been married for 14 years, explained:

[Earning money for the family] is his sole responsibility now. I won’t initiate anything from my side. [Q: Why did you choose to stop working three years ago?] He asked me to stop…He said that I don’t need to work like this in the hot weather under the sun [as a field laborer]. Sometimes I take our children with me, sometimes I leave them at home, they cry a lot. I should not leave them alone. …Who will look after my children? So my husband convinced me to quit. That’s why I quit.…He won’t let me work, sister. If God keeps him alive, he will never let me work again…He says, “you don’t need to work. I’ll take all the burden. You just take care of the kids and look after the family…He won’t let me [work]. He won’t agree. [MW #7]

In other cases, women expressed fear of criticism from others in the community if they were perceived to forgo their childcare duties. Some women did not have alternative childcare support (such as in-laws), and thus could not perceive how to balance childcare responsibilities with opportunities for income-generating activities. Overall, not working due to home duties was a central way in which women described conforming to broader social expectations about housework as their primary duty, and income-generating activities outside the home as the husband’s respective role.

Implicit denial of access took on two forms and reflected the extent to which women internalized or resisted prevailing gender norms about the extent of husband’s control within a marriage. In some cases, women foresaw a negative response from their husbands and did not seek permission, despite their desire to work. In these cases, women described considerable restrictions on their lives and linked these restrictions to being married. In comparison, other women did not seek income-generating opportunities (and as a result did not seek permission to engage in these activities) because their perspective of women’s work as transgressive aligned with that of their husbands and communities. Women invoked customary norms of women’s role in the home as a rationale for not working and argued that they did not want the additional burden or responsibility of income-generating activity. One 32-year old very poor woman stated: “It is against our custom. We may be in crisis but here in our place it is not in the custom that women will work” [MW #4].

Domain 2: Control of Household Income and Spending

The second conceptual domain that emerged from this analysis reflected themes around women’s control of their income, their husband’s income and household spending (see Fig. 1). By control of income and spending, we refer to women’s ability to make choices about what to do with their own and their husband’s income and household expenditures, ranging from daily expenses to larger, less frequent decisions around household repairs, renovations or major purchases. Women’s control over their own income (among women who participated in income-generating activities), their husbands’ income, and household expenditures ranged from sole or joint control with their husbands to complete lack of control. As illustrated in Fig. 1, women’s experiences were patterned similarly, regardless of whether they were economically active or inactive. In other words, irrespective of economic activity, women across the sample described greater or lesser constraints related to control over spending and income. However, we did find that women’s experiences differed based on the socio-economic status of their household. Among women who did not participate in income-generating activities, women in households with lower socio-economic status tended to report lower levels of control. Higher status women, even if they did not work, tended to report higher levels of control.

Among women who participated in income-generating activities, the majority had total or partial control over their own income (Fig. 1, Domain 2, nodes A – C). Most women considered themselves the owners of this income and perceived the income as their contribution to the household. Women’s income was largely spent on household needs, such as food or children’s needs, and did not usually make up much of the overall household income. One 27-year-old middle-class participant who kept and managed her own income, and spent her money on child-related needs noted: “I look after things which I need. I don't need to ask for something from my husband. I don't need to plead for money to him so that I can buy things. I have my own savings” [MW #16]. Some women did not have to account for the spending of their income to their husbands, and these women often also tended to hold greater control over the household income (inclusive of husband’s income) in general. Other women perceived it to be necessary to provide detailed accounting of the budget and expenditures to their husbands, even if their husbands did not ask or desire to know. A few women occasionally gave part of their income to their husbands and described this as required, even if not explicitly requested from their husbands. Women who had to report expenditures to husbands or gave their earnings to their husbands tended to report the lowest levels of decision-making with respect to household income and spending.

Nodes A & B: Sole or Joint Control

The first two nodes of experiences within Domain 2 reflect situations in which women reported sole or joint control over all household income, including control of their own earnings, and management of their husband’s income, as well as any savings accounts (nodes A and B). Financial control included making daily decisions on how to spend money, along with general accounting and budgeting of household expenses. Among women who reported sole control over household income, however, almost all were married to men who had migrated outside of Matlab for work or whose jobs took them away from home for long periods of time. In the absence of their husbands, women became the de facto financial manager of the home (node B). Only one participant who considered herself the sole manager of household finances reported that her husband lived at home.

Nodes C: Partial Control

Node C of Domain 2 captures the experiences of women who held partial control over household finances. Among women with partial control, almost all lived at home with their husbands. Women with partial control over household income described providing general input into financial decisions, but acknowledged that their husbands ultimately made the final decisions on household expenditures. As one 44-year old wealthy participant described, “I don't have to give [my income] to husband…that generally happens in other families. He doesn't count it” [MW #14]. However, she perceived her husband to be the final arbitrator in how to spend the money, arguing that: “He is a man therefore he knows better …He will ask for my suggestion [on how to spend money]…family is all about compromise. It's good to do everything together if the husband is good” [MW#14].

While this gendered division of financial responsibility was often described as normal, women often described income as a shared family resource and a way to enhance the general wellbeing of the family rather than serving as the individual resource of one person. One participant described how she managed the household income (hers and her husbands) but needed to seek permission from her husband in order to spend it. If she did not seek permission, she reported that they would quarrel and said: “[my husband] would say that the money does not belong only to me [wife]. It is necessary for the family" [MW#3]. Other women described situations in which they avoided challenging their husband’s income-related decision-making in order to avoid open conflict. One 41-year-old middle-class participant earned money but her husband supplemented her income with an allowance from his own earnings when he chose to do so. She noted:

No one else would bring me [money] except him. If I understand that, then what’s the benefit of arguing [if he does not bring money home]. There won’t be any fight then. There are many women who argue, exceed their limits, which will eventually break into argument. If I start arguing with you, it will end up in quarrel. You can’t avoid quarrel and fight then. [MW #10]

Node D: No Control

Conversely, women with no control over financial resources described themselves as lacking any access to or influence over household income and spending (node D). Like women who described experiences of partial control, women with no control tended to live at home with their husbands. In some cases, the husband was in charge of household income and decision-making but allocated his wife an allowance for her spending. Other women reported that their husbands controlled all household income and did not provide them with adequate allowances to cover their own expenses. Women who faced greater constraints with respect to access to income and spending tended to avoid discussing financial matters with their husbands. They expressed that asking husbands about money matters could be construed as a challenge to his financial authority and could create conflict within the home.

Domain 3: Income Contributions of Husband to Household

A third conceptual domain of economic activity within which women described varied levels of coercion was the level of husband’s income contribution to the household, given his capacity to work (see Fig. 1). Women’s reports of their husband’s economic contribution to the household varied and were to an extent based on whether women participated in income-generating activity.

Node A: Adequate Contribution to Household

As captured in node A, women who reported adequate contribution from their husbands to cover the household needs were both economically active and inactive. By “adequate contribution,” we refer to women’s personal assessments of whether their husbands contributed enough income to ensure the running of the household (e.g., enough money to buy food, cover childcare expenses, invest in savings, etc.). The majority of participants, regardless of whether they generated income, reported that their husbands provided adequate income to cover household costs and the contribution of income to household needs did not change if and when women began to participate in income-generating activities.

Node B: Reduced/changed Contribution when Women Work

Among other women who participated in remunerated work, some experienced a decreased contribution from their husbands after they initiated work (node B). In some cases, the decreased contribution was due to husband’s perceptions that their wives’ household contributions partially alleviated the burden on them to provide for the household. The primary type of change described was reduced contribution to food or children’s costs, which women then covered from their own expenses. Across the sample, regardless of husband’s contribution, women described spending their income primarily on children, food, or clothing expenses. However, among some women, these expenditures had previously been covered by their husbands and when they initiated income-generating activities, the costs were expected to be covered by earning wives.

Node C: Inadequate Contribution so Women Work

Other women initiated work in order to make up for their husband’s inadequate financial contributions to the household, even though he was able to, and in some cases did, work (node C). Notably, experiences captured by node C reflect situations in which men were able to but did not work, rather than men who were unable to find jobs, despite their efforts. Women described inadequate contributions from their husbands to the household income either because he did not want to work, or because he worked and withheld money from the household. In these cases, women often became involved in income-generating activities as a way to improve the family economic condition.

Node D: Inadequate Contribution and High Poverty

Finally, a few economically inactive women reported that their husbands did not adequately provide for the household, and, as they were not economically active themselves, the women experienced high levels of poverty or challenges to maintain the household (node D). For other women, who were not allowed to or unwilling to work, limited economic resources from their husbands meant that they struggled to maintain the household economy. As these women did not participate in any income-generating activities, they were limited in their access to financial resources and described living in high levels of poverty as a result. One 19-year old extremely poor woman did not have access to her husband’s income or have her own income. She said she had inadequate income for household needs, but avoided discussing money issues with her husband as a strategy to reduce risk of conflict:

He will keep the money to himself…he gives me nothing, doesn’t give any money to me. [Interviewer: Where does his money go? Can you estimate his income and expenditure?] I never ask about these things. Because I believe that, if it is there, it is for me. And if it is not for me, then it will not be there. That’s why I don’t ask at all. [MW #18]

In sum, in this low-resource setting, women described a range of relative financial contributions of both women and their husbands to the household. While the majority of women reported adequate contributions of income from their husband, a few women (often from lower socio-economic groups) described inadequate contributions due to their husband’s unwillingness to work or share income, and experienced higher levels of financial insecurity as a result.

Discussion

The present study focused on women’s economic activity and experiences of economic coercion in rural Bangladesh. Our grounded theory analysis revealed patterns of economic coercion in a society where practices and attitudes around women’s work are in flux. Overall, we observed that women’s experiences of economic coercion are multi-dimensional and shaped by their involvement in income-generating activities. By economic coercion, we focused here on coercive behaviors related to economic activities and control over resources related to women’s work, rather than a comprehensive taxonomy of economic coercion. In this context, three major themes of economic coercion, across the three economic activity domains, emerged from women’s narratives: denial of access to income-generating activities, coercive control over resources and economic neglect.

Notably, the dimensions of economic coercion identified here do not align neatly with leading constructs in the broader (largely Western-based) literature, in part due to varied patterns and circumstances of women’s economic activities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to Western settings. However, our results align with recent advancements in the measurement of economic coercion in LMICs. For example, in comparing our results to the Economic Coercion Scale-36 (ECS-36), the comprehensive scale validated among married women in the parent study, several high prevalence survey items aligned conceptually with women’s descriptions of economic coercion from this qualitative study. For example, based on the ECS-36, 26% of married women in rural Bangladesh reported being told that women should not work outside of the home, 21% were not allowed access to the family money, and 10% reported that their husbands refused to give them money to buy necessities, even when he had the money (Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al., 2021; Yount, Cheong, Miedema, et al., 2021). These examples are consistent with women’s qualitative narratives, which provide a more nuanced understanding of the broader patterns in Matlab, and underscore the need for measurement approaches to assess economic coercion that are based on the lived experiences of women in low-resource settings.

Yet, at the same time, women did not generally describe their experiences of economic coercion as forms of partner violence or abuse. Rather, women framed their experiences in the context of beliefs around what can and should happen in their communities with respect to women, work, family and the distribution of gendered power. As Kabeer (2016, p. 2) acknowledges, when women “assess the justice of their position in society on the basis of norms and values that embody, produce and legitimate women’s inferior status and restricted opportunities, then these will shape in important ways how they interpret their experiences.” Our results suggest that participants experienced incidents of economic coercion in marriage, and these experiences were normalized as part of the ebb and flow of intimate partnership dynamics. In particular, two emergent topics from this qualitative study warrant further discussion: the continued salience of patriarchal family systems and social norms in this context, and how economic coercion sheds light on the operation of power within the family system.

Features of the classic patriarchal family system, first proposed by Kandiyoti (1988), continue to be relevant to women in Matlab. In particular, the guardian role of husbands over wives, described for example over three decades ago by Cain et al. (1979) emerged as a crosscutting theme throughout the data. Permission to act – whether to take on income-generating activities or spend household income – was a key feature of women’s descriptions of their economic activities. In general, women ascribed to the belief that she could work only if their husbands said they could. Even women who were relatively less constrained, such as those whose husbands actively supported their income-generating activities, expressed conformity to normative expectations of needing permission from husbands before taking on work. As such, women continued to subscribe to an ideology of the family system in which the male head of household serves as the guardian of family members and arbitrator of key decisions. Under these conditions, constraints to economic activity became a normalized dimension of marital relationships.

Even women who acknowledged today’s greater economic and educational opportunities for women did not openly challenge the expectation that their husband’s permission was required to access these opportunities. In a context such as Bangladesh, where we see greater gender parity with respect to women’s schooling, injunctive gender norms about women and men’s relative position in the family appear to be changing more slowly than women’s entrance into remunerated work. These results align with other qualitative studies on women’s work in Bangladesh, illustrating how despite women’s greater participation in work, normative expectations and constraints continue to organize women’s lives and interactions with household members (Kibria, 1995; Schuler et al., 2017).

A major consequence of this lag between women’s opportunities and the gender norms underpinning spousal relations was the double burden of labor described by women in this sample. Many women described working in their “leisure time” and very few women described instances of male involvement in household work that would free up their time for income-generating activities. These results align with Kabeer’s (2016) assessment of the domestic division of labor in Bangladesh as “an area of non-decision making” to reflect the entrenched norms governing women and men’s roles in the household. Under these conditions, Kabeer (2016) argues, women do not expect to see change in expectations around women and men’s respective responsibilities. Indeed, analysis of men’s accounts of household labor, drawing upon men’s in-depth interviews from the parent study, is consistent with Kabeer’s assessment. While some men do describe helping with housework or childcare, this tended to occur only when women were ill (Dore et al., n.d.). In other settings where women join the workforce in large numbers, over a short period of time, the “second shift” of household labor alongside remunerated work, has shown to lead to adverse consequences for women, men and their relationships (Hochschild & Machung, 1989). Women’s greater participation in remunerated work in Bangladesh may influence the types of economic coercion they experience – as we demonstrate above – but also may lead to additional burdens of stress and time poverty.

These stressors may have detrimental effects on women’s health and wellbeing, unless broader systematic and normative change takes place concurrently, to support women’s presence in the labor force. Further research on gendered marital relations and women’s economic activities may shed light on the interaction between normative change and women’s work, and provide insight into the mechanisms through which women’s involvement in income-generating activities quantitatively puts them at greater or lesser risk for adverse health outcomes. In particular, as women’s economic opportunities continue to expand, efforts are needed to transform broader gender norms underpinning women’s experiences of economic coercion and other forms of IPV (Schuler et al., 2017).

A second emergent theme from this study relates to economic coercion as a reflection of different forms of power within the family system. Komter (1989) proposes a theory of marital power that captures not only visible, overt displays of power, but also the invisible and informal mechanisms of gendered power that shape marital relations. In Bangladesh, we find that women’s experiences of economic activity and economic coercion demonstrate overt and latent operations of power. Overt or manifest power includes visible or open attempts to change status quo relations, or conflict arising from this change (Komter, 1989). Women described circumstances in which husbands denied women access to economic activities or control over expenditures, and when women openly defied these constraints open conflict emerged. This backlash against women who transgress social norms around men’s control, reflect the operation of overt or manifest power.

However, latent power, or the covert operations of power in which the lack of action by the subordinate partner prevents open conflict, also was common in women’s narratives. Women described situations in which they forgo an action (such as taking on a job), due to fear of the consequences (e.g., criticism from others in the community if they were perceived to neglect childcare duties). Women also described inaction or acquiescence as a way to reduce or avoid conflict with their spouse. Latent power is thus unseen, but perpetrates unequal expectations and norms with respect to work, responsibilities and roles. Further research is needed to understand women’s strategies to cope with and to mitigate the effects of economic coercion, and how these strategies may reinforce men’s power and privilege in marriage and the family.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has a number of limitations. First, we conducted the study in a site where women’s labor force participation is low. Thus, our results with respect to women’s experiences of economic activity and economic coercion may not be reflective of women’s experiences in low-resource settings where women’s labor force participation is higher. In particular, husband’s interference is a domain of economic coercion in the literature from settings where women’s work is normative. Interference includes acts such as harassing intimate partners at work to inhibit their ability to complete tasks (Adams et al., 2008). However, husband’s interference in women’s work does not appear to be salient in the context of our study site in rural Bangladesh. Non-alignment with established forms of economic coercion from the literature may, in part, be due to women’s restricted access to wage work in general in rural Bangladesh, and the central role of permission, rather than interference. Future research directions on this topic could include how men may interfere in other domains of economic activity, such as women’s housework and non-remunerated work.

Second, we conducted the study in a rural site, and other patterns may emerge in urban settings, even within Bangladesh. We translated data into English, so translations may have impacted interpretation of data, as nuance may be lost or altered. However, we ensured validity of interpretation by discussing analysis and results with Bangladeshi team members and returning to the transcripts in their original language during analysis wherever needed.

Finally, the questions on the interview guide focused on income, work, remuneration, and credit. Other potential areas where women may experience economic coercion – such as property or education – were not explored in detail. Thus, our analysis does not provide a comprehensive assessment of all forms of economic coercion that a woman may face in the context of rural Bangladesh, but instead provides an in-depth assessment of economic coercion related to income-generating activity. In sum, this is an exploratory study and further qualitative and quantitative research is needed to understand better the multidimensional nature of women’s experiences of economic coercion elsewhere in Bangladesh and in other LMIC settings.

Practice Implications

Despite decades of growth in women’s participation in poverty-alleviation programs and the local economies of Bangladesh, our results suggest that women’s experiences of economic coercion are a central part of women’s participation or lack of participation in income-generating economic activities. Our results underscore the continued salience of gender norms around women’s paid and unpaid labor in the household and broader economy. Integration of gender transformative programming into microfinance and poverty alleviation programs may help to mitigate inequitable norms and attitudes around women’s work (Yount, Cheong, Khan, et al.,, 2021), which inhibit women’s access and free participation in income-generating activities in rural Bangladesh.

Conclusion

In sum, the present study on women’s economic activity and experiences of economic coercion in rural Bangladesh finds that women experience multi-dimensional forms of economic coercion related to their income-generating activities, shaped in part by their involvement in remunerated work. Women’s descriptions of economic coercion reflect the operation of manifest and latent forms of marital power. While women’s involvement in income-generating activities may provide some women with greater choice and agency, particularly those who bring resources to marriage (Heath, 2014), women’s narratives reflect the entrenched ideology of male power and privilege in the economic domains of marriage in rural Bangladesh.

Data Availability

The datasets generating during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adams, A. E., Sullivan, C. M., Bybee, D., & Greeson, M. R. (2008). Development of the Scale of Economic Abuse. Violence against Women, 14(5), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208315529

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Report on Labour Force (LFS) Bangladesh 2016–2017. Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Bates, L. M., Schuler, S. R., Islam, F., & Islam, M. K. (2004). Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30(4), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1363/3019004

Cain, M., Khanam, S. R., & Nahar, S. (1979). Class, Patriarchy, and Women’s Work in Bangladesh. Population and Development Review, 5(3), 405–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1972079

Dalal, K., Dahlström, O., & Timpka, T. (2013). Interactions between microfinance programmes and non-economic empowerment of women associated with intimate partner violence in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 3(12), Aticle e002941. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002941

Dore, E., Hennink, M., Naved, R. T., Miedema, S. S., Talukder, A., & Yount, K. M. (n.d.). How men shape women's economic activities in rural Bangladesh.

Fawole, O. I. (2008). Economic violence to women and girls: Is it receiving the necessary attention? Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 9(3), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838008319255

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Sociology Press.

Heath, R. (2014). Women’s Access to Labor Market Opportunities, Control of Household Resources, and Domestic Violence: Evidence from Bangladesh. World Development, 57, 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.028

Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift. Viking Penguin Inc.

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr, b). (2016). Health and Demographic Surveillance System - Matlab: Household Socio-economic Census 2014. icddr, b.

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr, b). (2020). Health and Demographic Surveillance System - Matlab: Registration of health and demographic events 2018. icddr,b.

Kabeer, N. (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 29(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00081-4

Kabeer, N. (2011). Between Affiliation and Autonomy: Navigating Pathways of Women’s Empowerment and Gender Justice in Rural Bangladesh. Development and Change, 42(2), 499–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01703.x

Kabeer, N. (2016). Economic Pathways to Women’s Empowerment and Active Citizenship: What Does The Evidence From Bangladesh Tell Us? The Journal of Development Studies, 53(5), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1205730

Kabeer, N., & Mahmud, S. (2004). Globalization, gender and poverty: Bangladeshi women workers in export and local markets. Journal of International Development, 16(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1065

Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with Patriarchy. Gender & Society, 2(3), 274–290. https://www.jstor.org/stable/190357

Kibria, N. (1995). Culture, social class, and income control in the lives of women garment workers in Bangladesh. Gender & Society, 9(3), 289–309. https://www.jstor.org/stable/190057

Koenig, M. A., Ahmed, S., Hoassain, M. B., & Mozumber, A. B. M. K. A. (2003). Women’s Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community- Level Effects. Demography, 40(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2003.0014

Komter, A. (1989). Hidden power in marriage. Gender & Society, 3(2), 187–216. https://www.jstor.org/stable/189982

Langsten, R., & Salem, R. (2008). Two approaches to measuring women’s work in developing countries: A comparison of survey data from Egypt. Population and Development Review, 34(2), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00220.x

Mahmud, S., & Tasneem, S. (2011). The underreporting of women's economic activity in Bangladesh: an examination of official statistics (BDI Working Paper Issue. B. D. Institute. Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Naved, R., Rahman, T., Willan, S., Jewkes, R., & Gibbs, A. (2018). Female garment workers’ experiences of violence in their homes and workplaces in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Social Science and Medicine, 196, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.040

Naved, R. T., Huque, H., Farah, S., & Shuvra, M. M. R. (2011). Men's attitudes and practices regarding gender and violence against women in Bangladesh. International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (Publication no: 135).

Naved, R. T., Mamun, M., A., Parvin, K., Willan, S., Gibbs, A., Yu, M., Jewkes, R. (2018) Magnitude and correlates of intimate partner violence against female garment workers from selected factories in Bangladesh, PLoS ONE, 13(11), Article e0204725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204725

Naved, R. T., & Persson, L. A. (2005). Factors associated with spousal physical violence against women in Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning, 36(4), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00071.x

Postmus, J. L., Plummer, S. B., McMahon, S., Murshid, N. S., & Kim, M. S. (2012). Understanding economic abuse in the lives of survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(3), 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511421669

Postmus, J. L., Plummer, S. B., & Stylianou, A. M. (2016). Measuring Economic Abuse in the Lives of Survivors: Revising the Scale of Economic Abuse. Violence against Women, 22(6), 692–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215610012