Abstract

Parents in dual-earner couples use family resources to balance work and other life roles, which can influence not only their own well-being, but that of their partner. Following the theories of conservation of resources and role balance, in the present study we proposed that family support is positively associated with life satisfaction, directly and via work-life balance, in dyads of different-sex dual-earner parents with adolescent children 10–17 years-old. Questionnaires were administered to 303 different-sex dual-earner couples in Temuco, Chile. Both parents answered the family subscale of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, the Work-Life Balance Scale, and the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Analyses were conducted using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model and structural equation modelling. Results showed positive associations for each parent from family support to life satisfaction, directly and via work-life balance. Crossover associations were only found from fathers to mothers—namely, fathers’ family support had a positive effect on mothers’ work-life balance, as did father’s work-life balance on mother’s life satisfaction. Overall, men’s resources had a positive effect on their female partner’s role balance and well-being. Results are discussed by considering gender dynamics in the work-life interface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The overall life satisfaction of individuals is linked to several roles they fulfill in different life spheres (Perrone et al. 2007). Most adults must negotiate the demands of work and other life domains, an ongoing task that has a substantial impact on their well-being. Moreover, for workers with a partner and children, the impact of this role negotiation also extends to their family’s well-being (Demerouti et al. 2005; Fan et al. 2015; Park and Fritz 2015). The dynamics of the work-family interface have been widely studied (Haar and Brougham 2020), more so as women have increasingly entered the workforce over the last decades (Hobfoll and Shirom 2001). However, this line of research has yet to emphasize that, like single or childless workers, working parents have relations and roles outside work besides their spouse and children, such as leisure activities, friends, and community groups (Haar 2013).

Life satisfaction, the cognitive assessment of one’s overall life conditions (Diener et al. 1985), has been established as an outcome related to the work-family interface. This relationship has been shown at an individual level and in dyads more frequently composed of husband-wife with young children (Abbott et al. 2013; Matias et al. 2017; Pedersen 2014). The work-life interface has been less studied, but evidence shows it is also linked to life satisfaction, individually (Haar 2013; Haar et al. 2014), and via crossover in different-sex dual-earner couples with adolescent children (Schnettler et al. 2020a). Crossover is understood here as an interindividual transmission of resources between members of a dyad (Hobfoll et al. 2018). A successful balance between work and other life roles can be both an antecedent and a consequence of how individuals manage their resources (Haar et al. 2019), which often involve others close to them (Hobfoll et al. 2018). This transmission of resources, in turn, can account not only for the individual’s well-being, but also that of their closest relations (Haar 2013).

Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM, Kenny et al. 2006), in the present study we examine the associations among work-life balance, perceived family support, and life satisfaction and whether work-life balance has a mediating role in these relationships in dyads of different-sex dual-earner parents with adolescent children. In the APIM, actor effects are the outcomes predicted by the individuals’ own characteristics, whereas partner effects are outcomes from one member of the dyad which are predicted by the characteristics of the other member (Kenny et al. 2006). In our study, life satisfaction is examined as the outcome of both the aforementioned work-life balance and family support, the latter which is a source of tangible and intangible resources shown to contribute to both workers’ work-life balance (Russo et al. 2015), and general well-being (Halbesleben et al. 2014; Hobfoll 2002).

Perceived Family Support as a Resource for Life Satisfaction

In the work-family interface, social support is considered a crucial resource to maintain workers’ well-being (Halbesleben et al. 2014; Hobfoll 2002). Social support allows individuals to gain more resources through other individuals. The conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll 1989, 2002) posits that individuals are motivated to acquire and protect things that they value, termed resources, which can be objects (e.g., a car), conditions (e.g., marital status), personal characteristics (e.g., self-esteem) or energy (e.g., knowledge). In this sense, social support from family members provides workers with more resources via instrumental and affective means, which in turn increase the workers’ satisfaction and well-being (Leung et al. 2020).

The person’s assessment that they have a social network on which they can rely is termed perceived social support (Zimet et al. 1988). Perceived family support (family support from here on in) can change over the life cycle as the meaning of family changes as well: for younger adults, the point of reference is their family of origin, whereas for older adults it means the family of their own (Zimet et al. 1988). Working adults can perceive family support in two ways (King et al. 1995): socio-emotional support, related to the family members’ interest in the worker’s job, and instrumental support, which entails facilitating daily functions for the worker, such as sharing household tasks or structuring family schedule to accommodate the workers’ requirements.

The COR theory posits that family support can have a substantial impact on the workers’ job performance and satisfaction (Drummond et al. 2017; Ferguson et al. 2012; King et al. 1995), as well as on their life satisfaction (Lee and Shin 2017; Xu et al. 2019). Furthermore, counting on family support results in positive outcomes not only for the individual, but also for close persons sharing the same environment. For different-sex dual-earner couples, the literature has established these crossover effects, showing that experiences, whether negative (e.g., stress, Westman and Vinokur 1998) or positive (e.g., life satisfaction, Schnettler et al. 2020b; Steiner and Krings 2016) can be transmitted between the partners (Demerouti et al. 2005; Park and Fritz 2015). Resources, like experiences, can also cross over in members of a dyad. Hobfoll et al. (2018) described studies related to resource exchange between intimate partners, showing that each partner responded to the other’s resource gain (e.g., self-esteem and job-related self-efficacy) as if it were their own gain.

This interdependence between dual-earner couples is framed by family systems theory, which posits that individuals involved in reciprocal relationships are emotionally connected and can influence each other’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (Kerr and Bowen 1988). Moreover, Westman (2001) and Hobfoll et al. (2018) proposed three mechanisms that explained how crossover of resources occurs between partners: directly through empathy, indirectly through mediators and moderators (e.g., interpersonal factors), and spuriously through shared stressors. Studies have reported that life satisfaction can cross over between partners in dual-earner couples (Demerouti et al. 2005; Park and Fritz 2015; Steiner and Krings 2016), which may be considered a direct effect in which one partner’s life satisfaction enhances that of the other. One partner’s family support, as shown in previous research, can be expected to be a resource that enhances their own life satisfaction, but also, following Hobfoll et al. (2018), one partner’s family support can have a positive effect on the other partner’s life satisfaction.

Overall, family support is a psychological capital that can increase or reduce the person’s resources to achieve well-being (Haar & Brougham, 2002). Research shows that family support can enhance an employee’s experience of work-family balance (Ferguson et al. 2012), which is a means to improve well-being, but individuals’ lives outside work encompass more than family life. Lower family support may entail fewer resources at hand to cope with job and family demands, which in turn can prevent the person from investing and participating in other life roles (Haar et al. 2019).

Work-Life Balance as a Mediator to Enhance Life Satisfaction

The concept of work-life balance (WLB, Haar 2013) refers to how effectively workers perceive they can manage multiple roles in their life, including but not limited to work and family roles. In Haar’s (2013) approach, balance does not mean 50/50 allocation of time and energy for work and other life activities, but a personal perception of how well these multiple roles fit with one another. In this sense, role balance theory (Haar 2013) establishes that beneficial outcomes for the individual do not come from the roles themselves (i.e., not enrichment nor conflict), but from the perceived successful managing of these roles.

Both the COR and role balance theories support that employees with greater resources (e.g., time, control) can enhance the fit between their work and life roles, leading to higher WLB (Haar et al. 2019). Moreover, also in line with COR theory, higher levels of WLB would entail more psychological resources that can be invested to obtain beneficial outcomes (Haar and Brougham 2020), including a higher life satisfaction (Haar 2013; Haar et al. 2014; Schnettler et al. 2020a). Research on Haar’s (2013) WLB is scarce, but progressively researchers are addressing the work-life interface instead of the work-family one because the former allows us to include a wider array of samples and life conditions (Gragnano et al. 2020; Russo et al. 2015). In this regard, WLB functions as an intermediate variable.

Family support has been shown to be a resource for WLB. In the work-family interface, evidence shows that a supportive partner may enhance the employee’s ability to balance work and family roles (Ferguson et al. 2012). Family support may also enhance the workers’ ability to manage the roles outside work that transcend the family sphere (e.g., hobbies, community groups, Haar 2013; Haar & Brougham, 2002). Russo et al. (2015) found that perceived family support can facilitate WLB for both part-time students and full-time workers in different organizational settings, which improves their job-related performance. Because family support has indirect effects on employees’ life satisfaction (Lee and Shin 2017), it can be expected that family support is associated with WLB, and WLB, in turn, contributes to enhancing life satisfaction in workers.

Most studies on the work-life interface have focused on intraindividual effects (Haar and Brougham 2020). In this line, an adequate WLB has been positively associated with workers’ satisfaction with their job (Brough et al. 2014; Haar 2013; Haar et al. 2014; Viñas-Bardolet et al. 2019), family (Brough et al. 2014; Viñas-Bardolet et al. 2019; Schnettler et al. 2020a), and life (Haar 2013; Haar et al. 2014; Schnettler et al. 2020a). A previous study examined the crossover associations between one partner’s WLB with the other partner’s life satisfaction (Schnettler et al. 2020a), finding asymmetric crossover effects, where the men’s WLB was associated with their female partners’ life satisfaction, but this association was not found from women to men.

The present study builds on previous work, with two expectations. The first one is that COR theory stands when WLB is associated not only to one’s beneficial outcomes, but to those of a partner. Namely, it would be expected that one partner’s higher WLB (afforded by access to more resources) could enhance the other partner’s life satisfaction. Second, it can be expected that one partner’s WLB has a mediating role between their own family support and life satisfaction (Haar and Brougham 2020; Russo et al. 2015), as well as between the other partner’s family support and life satisfaction.

The Present Study

There is increasing interest in examining the interrelationships between different life domains and outcomes for different-sex couples in which both partners contribute to the household income (Schnettler et al. 2018). Most studies have focused on work-family role conflict and enrichment (Haar and Brougham 2020), showing that both members of these couples can deal with conflicting family and work roles (Chrishianie et al. 2018). However, asymmetric effects by gender have been reported in Liu and Cheung’s (2015) study on work-family enrichment—life satisfaction crosses over in husbands and wives (wives’ enrichment enhances husbands’ life satisfaction) and in Jensen et al.’s (2013) study on crossover of support and marital outcomes (husbands’ support enhances wives’ marital outcomes). Focusing on work-life balance, Schnettler et al. (2002b) also reported asymmetric effects, in which men’s WLB enhanced their female partners’ life satisfaction.

Observing gender differences in crossover effects should account for practical aspects such as the division of housework. The degree of involvement in housework has an impact on the amount of resources individuals have available and in how they balance their different roles. Studies from an individual (Bartley, Blanton, & Gilliard, 2015) and a dyadic (Cerrato and Cifre 2018) standpoint have found that a gendered division of labor persists in the home in Latin America (Vaca 2019) and around the globe. Women spend more time doing household chores than their male partners because women are still considered the primary party responsible for the home sphere. The role re-negotiations that members of dual-earner couples make have resulted in the woman taking on a role as a worker in addition to her domestic roles (Abbott et al. 2013), whereas the man’s work role is still considered his family role (Bartley et al., 2015, p. 73). Nevertheless, it has been reported that men are increasingly facing conflicting demands between their work and family roles as they get more involved in housework and childcare (Yucel and Latshaw 2020). Under these conditions, for both partners, family support can be an important resource that allows them and their partners to better balance their work and other life roles.

Moreover, the study of well-being in different-sex dual-earner parents have mostly focused on those with young children (Abbott et al. 2013; Matias et al. 2017; Pedersen 2014), whereas parents of adolescent children have received less attention. The World Health Organization (2020) establishes the adolescent period from ages 10 to 19 years-old; our study focuses on parents of adolescents aged 10 to 17 years-old because in the Chilean context, youth commonly start university and move from their parents’ house at 18 years-old. Adolescents may pose fewer demands of parental care than younger children, being able to provide emotional and instrumental support while becoming more independent from their parents (Tisdale and Pitt-Catshupes 2012). Yet, overall, adolescence is also particularly challenging for parental well-being (Meier et al. 2018), partly due to its demands that parents allocate resources (time, attention, shared activities) to ensure their adolescent child’s healthy adjustment and ongoing development (Davis et al. 2015). Adolescence changes the child-rearing dynamics that dual-earner couples face with younger children because it presents them with new resources (e.g., adolescent can provide support) and demands (e.g., risky behaviors, Han et al. 2010). Therefore, it is relevant to examine the perception of family support and the ability to balance various life roles in parents of adolescent children, which in turn can have an impact on their life satisfaction, both individually and as a couple.

Against this background, the aims of the present study were to explore the associations between perceived family support (PFS), work-life balance (WLB), and life satisfaction (LS) in dyads of different-sex dual-earner parents with adolescent children. The mediating role of WLB in these relationships was also explored. Using the APIM framework, and following theories that establish the transmission and exchange of resources in individuals and dyads (i.e., family systems, COR and role balance theories), we hypothesized that perceived family support, work-life balance, and life satisfaction would be positively associated for each parent (actor effects, Hypothesis 1); that perceived family support, work-life balance, and life satisfaction of one parent would be positively associated with those of the other parent (partner effects, Hypothesis 2); and that work-life balance would have a mediating role between perceived family support and life satisfaction for both parents (actor and partner effects, Hypothesis 3).

Method

Participants

Non-probability sampling was used to recruit 303 different-sex dual-earner couples (married or cohabiting) with at least one adolescent child between 10 and 17 years of age in Temuco, Chile. Participants were recruited from seven schools that serve socioeconomically diverse populations. The mothers’ average age was 40.87 years old (SD = 7.43, range = 26–68), and the fathers’, 43.18 (SD = 7.98, range = 22–70). The average number of family member was four (SD = 1.10, range = 2–11), with an average of two children (SD = 1.02, range = 1–6). Families were distributed across socioeconomic status (SES), ranging from high and upper-middle (34 families, 11.2%); middle (63, 20.8%); lower-middle (112, 37%); low (65, 21.5%); to very low (9.6%) SES.

Procedure and Measures

The present study is part of a larger research project examining eating habits and subjective well-being in Chilean families. Parents who agreed to participate were visited in their homes by one of six trained interviewers (two men, four women) during May and August 2017. The anonymity of the responses was ensured. After both parents signed written informed consent, the questionnaires were personally administered separately to each parent by the interviewers. Mothers and fathers responded to the same scales, described in the following in the order they were presented. Prior to its conduct, our study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de La Frontera.

Perceived Family Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support measures participants’ subjective assessment of social support from family, friends, and significant others (Zimet et al. 1988). Only the four-item Perceived Family Support subscale was used in our study to measure perceived family support (i.e., “My family really tries to help me” [Mi familia realmente trata de ayudarme]; “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family” [Recibo la ayuda y apoyo emocional que necesito de mi familia]; “I can talk about my problems with my family” [Puedo hablar de mis problemas con mi familia]; and “My family is willing to help me make decisions” [Mi familia está dispuesta a ayudarme a tomar decisiones]). Respondents rated each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Completely disagree) to 5 (Completely agree). Scores were obtained by summing the scores from the four items such that higher score indicate stronger perceived family support. The Spanish version of the Perceived Family Support (PFS) subscale was used (Mella et al. 2004). Pinto et al. (2014) validated this scale in Chilean older adults and reported a Cronbach alpha of .93. In our study, Cronbach alpha was .88 for mothers, and .89 for fathers.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS evaluates individuals’ overall cognitive judgments about their own life (e.g., “In most ways your life is close to your ideal” [En muchos aspectos, su vida se acerca a su ideal]; Diener et al. 1985). Respondents indicated their degree of agreement with five statements using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Completely disagree) to 6 (Completely agree). SWLS scores were obtained by summing the scores from the five items so that higher scores indicated higher satisfaction with life. The Spanish version of the SWLS was used, for which a Cronbach alpha of .88 has been reported (Schnettler et al. 2013). In our study, Cronbach alpha was .89 for both mothers and fathers.

Work-Life Balance (WLB)

The WLB scale is a three-item measure that assesses participants’ perceptions of how well their work and other life roles are balanced (i.e., “I am satisfied with my work–life balance, enjoying both roles” [Estoy satisfecho con mi balance trabajo-vida, disfruto con ambos roles]; “Nowadays, I seem to enjoy every part of my life equally well” [Actualmente, disfruto equitativamente cada parte de mi vida]; and “I manage to balance the demands of my work and personal/family life well” [Me las arreglo para balancear bien las demandas de mi trabajo y mi vida personal/familiar]; Haar 2013). Respondents rated each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Completely disagree) to 5 (Completely agree). Responses were summed across items such that higher scores indicate higher perceived work-life balance. The Spanish version of the WLB was used (Schnettler et al. 2018). Studies in different countries show an average Cronbach alpha of .84 (Haar et al. 2014). In our study, the WLB scale showed good internal reliability with Cronbach alphas of .82 for mothers and .87 for fathers.

Sociodemographic Information

Mothers and fathers were asked about their age. Mothers were asked about the number of family members and the number of children. Mothers were asked about the education level and occupation of the person in their household who perceived the main (higher) income. Responses to these two questions were used to determine the family’s socioeconomic status (SES, Adimark 2004).

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS v.23. Following Claxton et al. (2015), a dyadic confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to verify the latent structure of each scale and test their psychometric properties. The omega coefficient was used to examine the internal consistency of the scales (McDonald 1970). We assessed convergent validity by inspecting the standardized factor loadings of each scale (ideally >.50) as well as their significance and average variance extracted (AVE, values >.50) (Hair et al. 2006). Discriminant validity was obtained by comparing the AVE for each scale with the square of the correlation between the factorial scores of the scales (Hair et al. 2006).

To test the hypotheses regarding the effects between both members of the couple’ PFS, WLB, and LS (Hypotheses 1 and 2), the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) with distinguishable dyads was assessed using structural equation modeling (SEM) (Kenny et al. 2006). The APIM uses the dyadic interaction as the unit of analysis. In the APIM framework, each dyad member is an actor as well as a partner in the analysis (Kenny et al. 2006). Actor effects comprise the associations between the PFS of one parent with their own WLB and LS. Partner effects comprise the associations between the PFS of one parent with the WLB and LS of the other parent.

The APIM controls for the extent to which one parent’s PFS is affected by the other parent’s PFS and vice versa through a correlation between independent variables of each member of the dyad (the father’s and mother’s PFS). The APIM also includes correlations between the residual errors of the dependent variables of both parents (LS), which controls for other sources of interdependence between partners (Kenny et al. 2006).

To control for the effects of number of children and family SES in modeling the fit of the data, these variables with a direct effect on the dependent variable of the dyad members (LS) were incorporated. In the case of the number of children, the presence of children has been associated with low levels of life satisfaction in working parents from developed countries and with higher levels in working parents from Latin American countries (Terrazas-Carrillo et al. 2016). The second control variable, SES, was introduced because the literature has shown its substantial influence on parents’ life satisfaction (Pollmann-Schult 2014; Rajani et al. 2019).

The CFA and SEM were conducted using Mplus 7.11. Parameters of the CFA and structural models were estimated using the robust unweighted least squares (ULSMV). Considering the ordinal scale of the items, the polychoric correlation matrix was used to perform the SEM analysis. The model Chi-square (χ2), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to determine the model fit of the data. The TLI and CFI indicated a good fit with a value above .95. A good fit is found when the value of the RMSEA is lower than .06. A good model fit is found when the model Chi-square is nonsignificant (Hu and Bentler 1999). To test the mediating role of WLB (Hypothesis 3) SEM was used through bootstrap confidence interval (CI). The mediating role was established when the CI for the mediation effect did not include zero.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Fathers’ mean age (M = 43.18, SD = 7.98) was significantly higher than that of the mothers (M = 40.87, SD = 7.43), t(604) = −3.67, p < .001. Descriptive statistics and correlations for each parent’s PFS, WLB and LS are displayed in Table 1. An independent samples t-test showed that there was a significant difference between mothers and fathers on WLB, t(604) = 2.00, p = .046, d = .16, and no significant differences on either PFS, t(604) = .88, p = .375, or LS, t(604) = −1.04, p = .295. The correlation analysis showed that all three study variables were significantly associated for one parent and between both parents. There were no missing data because the questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers to ensure that all questions were addressed. Hence, the analysis conducted included all responses from the 303 dyads.

Psychometric Properties of the Scales

Results for the dyadic CFAs indicated that the measurement models of PFS, χ2 (15, 303) = 32.54, p = .005 (CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .06), WLB, χ2 (5, 303) = 5.70, p = .337 (CFI = 1.00, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .02), and SWLS, χ2 (29, 303) = 36.73, p = .153 (CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .03) have a good or at least acceptable fit to the data for both members of the couple. Although the Chi-square test was significant for the PFS scale, it is well established that the Chi-square test is sensitive to sample size (MacCallum et al. 2006), as is the case in our study. The reliability of each scale is good with values of omega coefficients between .82 and .94 and AVE values above .50. Convergent validity is supported by the size of factor loadings, all of which were statistically significant and with values above .50. Discriminant validity is supported because all AVE values are greater than the square correlation between the factorial scores of the scales (see Table 1).

Test of Hypotheses

Actor Effects

Having controlled for the effects of number of children and family SES, the model that assessed the APIM association among both parents’ PFS, WLB, and LS had fit indices that showed a good fit with the data (CFI = .97, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .03). The Chi-square test was significant, χ2 (265, 303) = 380.51, p < .001, although this test is sensitive to the study’s sample size (MacCallum et al. 2006). A significant correlation (covariance) was found between the WLB of both parents (r = .48, p < .001), as well as between the residual errors of mother’s and father’s LS (r = .26, p = .003).

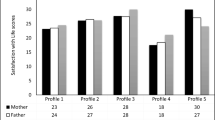

As shown in Fig. 1, the path coefficients related to actor effects indicated that PFS was positively associated with LS in mothers (γ = .36, p < .001) and fathers (γ = .48, p < .001). PFS was positively associated with WLB in mothers (γ = .37, p < .001) and fathers (γ = .46, p < .001). WLB was positively associated with LS in mothers (γ = .29, p < .001) and fathers (γ = .26, p < .001). Thus, this finding supports Hypothesis 1, which stated that PFS, WLB, and LS would be positively associated for each parent.

Actor-partner interdependence model of the effect of perceived family support (PFS) on work-life balance (WLB) and satisfaction with life (SWLS) in dual-earner couples with adolescent children. Em and Ef: Residual errors on SWLS for the mother and father, respectively. Values in the diagram correspond to standardized path coefficients (γ). The control for the effects of number of children and family socioeconomic status on the dependent variable of both members of the couple (SWLS) were not shown in the path diagram, so as not to overload the figure

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Partner Effects

The partner effect analysis showed that mothers’ PFS was not significantly associated with the fathers’ LS (γ = −.14, p = .077). Likewise, the fathers’ PFS was not significantly associated with the mothers’ LS (γ = −.03, p = .669). The mothers’ PFS was not significantly associated with the fathers’ WLB (γ = .10, p = .225), whereas the fathers’ PFS was positively associated with the mothers’ WLB (γ = .20, p = .024). Likewise, the mothers’ WLB was not significantly associated with the fathers’ LS (γ = .15, p = .096), whereas the fathers’ WLB was positively associated with the mothers’ LS (γ = .16, p = .042). Hypothesis 2 stated that PFS, WLB, and LS of one parent would be positively associated with those of the other parent. These findings did not support Hypothesis 2 for mothers, whereas they partially supported Hypothesis 2 for fathers.

Testing the Mediating Role of WLB

The last hypothesis, Hypothesis 3, stated that WLB had a mediating role between PFS and LS. The role of mothers’ WLB as mediator in the relationship between their own PFS and LS was supported by a significant indirect effect obtained with the bootstrapping confidence interval procedure (standardized indirect effect = .10, 95% CI [.02, .17]). Likewise, the mediating role of fathers’ WLB in the relationship between their own PFS and LS was also supported by a significant indirect effect (standardized indirect effect = .11, 95% CI [.02, .26]). Because the confidence intervals did not include zero for either member of the couple, it is shown that WLB had a mediating role between PFS and LS for each member of the couple.

Regarding the mediating role of one parent’s WLB on the other parent’s PFS → LS relationship, effects were not found. The indirect effect of the mothers’ WLB as mediator between the fathers’ PFS and LS was not supported because the confidence intervals did include zero (standardized indirect effect = .03, 95% CI [−.02, .16]). Similarly, the indirect effect of the fathers’ WLB as mediator in the relationship between the mothers PFS and LS was not supported because the confidence intervals did include zero (standardized indirect effect = .01, 95% CI [−.01, .04]). Therefore, one parent’s WLB did not have a mediating role between the other partner’s PFS → SL relationship. These findings thus partially support the mediating role of WLB between PFS and LS, as stated in Hypothesis 3.

Discussion

Research on the well-being of dual-earner parents traditionally focuses on the work-family interface. Addressing how working parents in different-sex couples balance their work and other life roles—including but not limited to the family—can be key to understanding the resources that individuals have and how they manage these resources (Haar et al. 2019). This resource management is an ongoing task which often involves significant others (Hobfoll et al. 2018), and it has an impact on the person’s life satisfaction (Haar 2013; Haar et al. 2014) and on that of their working partner (Schnettler et al. 2020a).

In the present study we examined the transmission of resources between working parents through the associations between perceived family support (PFS), work-life balance (WLB), and life satisfaction (LS) in different-sex dual-earner parents with adolescent children. Findings showed that PFS, WLB, and LS were positively associated for both mothers and fathers (Hypothesis 1), as expected from previous literature. On the other hand, the effects of one parent’s PFS, WLB, and LS on the other parent were not reciprocal as proposed (Hypothesis 2). Lastly, WLB had a mediating role between PFS and LS for each parent, but this mediating role did not cross over to the other parent’s PFS → LS relationship (Hypothesis 3).

Perceived Family Support, Work-Life Balance, and Life Satisfaction

The first hypothesis of our study was that perceived family support, work-life balance, and life satisfaction would be associated for the same parent. In the APIM framework, these are the actor effects. Results for family support showed that this variable was positively linked to higher life satisfaction, as expected (Lee and Shin 2017; Xu et al. 2019). Moreover, family support was also associated with work-life balance, in agreement with findings by Russo et al. (2015). WLB, at the same, was also positively associated with life satisfaction (Haar 2013; Haar et al. 2014; Schnettler et al. 2020a).

These positive actor effects suggest that life satisfaction in working parents can be a consequence of family support manifesting in the two ways outlined by King et al. (1995). Family support can have a direct effect on life satisfaction as affective and instrumental support. This contribution, according to the COR (Hobfoll 1989, 2002; Russo et al. 2015), occurs because family support is a resource, and a means to access more resources, to enhance the worker’s fit between their work and other life roles (Haar et al. 2019). In turn, as expected from role balance theory (Haar 2013), a successful WLB means better resource management, leading to higher life satisfaction. Taken together, these findings show positive actor effects among perceived family support, work-life balance, and life satisfaction, regardless of the gender of the working parent.

Crossover Effects between Parents

The second hypothesis of our study tested partner effects, that is, interrelations between one parent’s PFS, WLB, and LS and those of the other parent. This hypothesis is primarily based on family systems theory (Kerr and Bowen 1988), which states that family members have strong emotional connections and react to one another, setting up reciprocal exchanges. These crossover effects have been reported in dual-earner couples (Demerouti et al. 2005; Park and Fritz 2015; Schnettler et al. 2020b), and our study sought to further examine the transmission of psychological resources from one partner to the other (Hobfoll et al. 2018). The results indicated that these interrelations were not reciprocal. Nevertheless, as we discuss in a following section, previous dyadic studies on stress, support, and satisfaction in different-sex couples (Jensen et al. 2013; Leavitt et al., 2016) show that there are gender differences in how one parent relates to the other when they are providers (actors) or recipients (partners).

Mothers as actors showed no significant effects on fathers, that is, their own resources did not seem to contribute to their male partners’ work-life balance nor life satisfaction. In our actor-partner analysis, we found that mothers’ perceived family support had no significant effect on their male partners’ work-life balance nor life satisfaction. Recall, however, that fathers’ own family support does contribute to their WLB, suggesting that their own resources in this regard are sufficient to afford them satisfactory role management. Lastly, mothers’ adequate balance of their own life roles is not associated with their male partners’ life satisfaction, a finding that replicates that of a previous study in Chilean dual-earner couples (Schnettler et al. 2020a).

Fathers’ effects on mothers showed a different dynamic. On one hand, there was no significant effect from fathers’ perceived family support on mothers’ life satisfaction. In other words, fathers’ access to emotional and instrumental family-related resources does not cross over to the mothers’ assessment of her own life. However, the other two partner effects from fathers to mothers were positive. First, there was a positive effect from fathers’ perceived family support to the mother’s work-life balance. Following the COR theory, this result means that fathers’ family resources cross over to the mothers’ ability to manage their life roles. Hence, although the support that a father receives from his family does not reflect on the mother’s life satisfaction, this perceived support may still be beneficial for her. It may be the case that men who receive family support, although they do not provide resources that contribute to their female partner’s life satisfaction, they may be providing instrumental support (i.e., rather “doing” than “being”, Jensen et al. 2013), contributing to their partner’s management of her roles.

The second positive partner effect we found in our study was from fathers’ work-life balance to mothers’ life satisfaction. There is previous evidence that a man’s work-life balance contributes to his female partner’s life satisfaction (Schnettler et al. 2020b). Taken together, findings from the previous study and the current one suggests that fathers’ management of their different life roles can help them allocate sufficient resources to different roles and activities in a manner that has a positive impact on their female partners’ life. It is notable that fathers’ effects on mothers are seen through a more practical aspect, role balance, rather than perceived family support, which includes instrumental but also affective assistance. These findings are in line with Jensen et al. (2013) and Leavitt et al. (2016) who indicated gender differences in how resources and experiences cross over between different-sex couples and the critical role of men’s support in well-being outcomes for both members of the couple (Jensen et al. 2013).

The gender differences reported here contradict other studies focused on work-family crossover with different-sex dual-earner couples, which have reported no gender differences in these partner effects, suggesting a growing egalitarianism between husbands and wives (Park and Fritz 2015; Yucel and Latshaw 2020). Indeed, men are increasingly reporting conflicting demands between their work and family roles as they get more involved in housework and childcare (Yucel and Latshaw 2020). Nevertheless, an unequal division of labor and gender roles remains strongly marked in Latin America (Vaca 2019). In this sense, any role re-negotiations that members of dual-earner couples make have resulted, at a cultural level, in the woman taking on a role as a worker in addition to her domestic roles (Abbott et al. 2013), whereas the man’s work role is still considered “work time for the family” and thus a trade-off for household labor (Bartley et al., 2015, p. 73). It is possible that this trade-off also occurs for other roles outside the family because equating work time with family times frees men, more than women, to pursue other interests outside their job and their family sphere.

Work-Life Balance as a Mediator

To our knowledge, there are no published studies testing the link between family support and role balance outside the work-family interface to enhance well-being in working parents. Hence, the last hypothesis of our study tested actor and partner effects of WLB as a mediator between perceived family support and life satisfaction. The first part of this hypothesis proposed that WLB had a mediating role for both mothers and fathers (actor effects). This expectation was supported because perceived family support and life satisfaction were associated both directly (as shown in the first hypothesis) and indirectly via work-life balance, in the same parent, regardless of gender.

The prior finding underscores the importance of family support to achieve higher levels of WLB (Russo et al. 2015), in line with COR theory, which can then be invested to enhance positive outcomes (Haar and Brougham 2020) for individuals. These results contribute to literature showing that family support has indirect effects on workers’ life satisfaction (Drummond et al. 2017; Ferguson et al. 2012; Lee and Shin 2017). Moreover, the mediating role of WLB between family support and life satisfaction should be discussed in the context of the division of labor. The finding from our second hypothesis, that women’s WLB benefits from men’s perceived family support, underscores the importance of working mothers getting instrumental support from the family, particularly from those who are closest to her (i.e., her partner). The literature consistently shows that mothers remain responsible for planning and carrying out domestic work and caring for her children and partner (Abbott et al. 2013), whereas men do not get as involved in housework and childcare and instead undertake household maintenance duties and “help” with child supervision (Abbott et al. 2013; Cerrato and Cifre 2018). Under these conditions, women who are more independent from their partners, as may be the case for working women in our study, are more likely to consider the traditional (i.e., inequal) distribution of household chores unfair (Cerrato and Cifre 2018). This latter assessment of not receiving enough family support may be related to their perception of a lower work-life balance which, in turn, decreases their life satisfaction.

Lastly, the mediating role of WLB as a partner effect was not supported for either parent. In our second hypothesis, it was shown that fathers’ family support crossed over positively to the mothers’ WLB. In testing this hypothesis, however, it was shown that mothers’ WLB did not cross over to fathers’ life satisfaction. Similarly, mothers’ family support was not associated with fathers’ WLB, and the latter, in turn was not associated with fathers’ life satisfaction. Hence, WLB appears to be a consistent intrasubject mediator (Haar 2013), but in our study, one parent’s role balance plays a limited part in the other parent’s transmission of resources from family support to life satisfaction.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitations of our study must be addressed to improve further research. The first limitation is the study’s relatively small sample, recruited using a non-probabilistic method; therefore, results cannot be generalized to the population of dual-earner families with adolescent children. Second, although our study refers to effects, following the literature on the APIM, a causal link cannot be established between the variables under study, and longitudinal studies are required to further support the associations reported. A third limitation is that the measure of family support referenced “people who are important in [participants’] life,” but it does not explicitly include specific family members. The difference between the effect of perceived family support from mothers to fathers (non-significant) and from fathers to mothers (significant) raises the question of who is indeed included in their definitions of family. In Latin American cultures, including Chile, mothers may rely on extended family (parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles) for support (Reynolds at al., 2018), but which relatives composed the “family” for each parent was not explored. Divergences in this regard may account for differences in partner effects and should be further examined in future studies.

A fourth limitation is that common method variance (CMV) may be present in the responses, and this overlap was not accounted for in our analysis. CMV may inflate the values of the statistical correlations because each parent completed the same measures. To our knowledge, there is no procedure to correct CMV bias in dyadic analysis, but future studies can reduce this potential bias by changing the order of items and measures for participants and by performing specific statistical checks (see Fuller et al. 2016; Podsakoff et al. 2012). One last limitation is that the questionnaire did not ask about the nature of the job of both parents, whether they worked part-time or full-time, and their degree of involvement (e.g., supervision, shared activities) with their adolescent child. Future studies should account for these limitations.

On the other hand, one of the strengths of our study is that it was conducted in a Latin American context, whereas most research on dual-earner couples’ well-being has focused on more developed regions. It is thus recommended that a broader view on work-life balance and life satisfaction studies continues in dual-earner dyads by considering samples from contexts with varying degrees of gender equality and different family structures, using longitudinal designs, and acknowledging diverse facets of the work-life interface (e.g., Gragnano et al. 2020). Future research in this line will also benefit from accounting for potential moderators in the interrelations among family support, work-life balance, and life satisfaction in working parents.

Practice Implications

Fathers’ effects of their perceived family support and work-life balance on mothers’ work-life balance and life satisfaction, respectively, suggest the positive influence of men’s resources on their female partner’s role balance and well-being. Family practitioners should seek to strengthen this gain and transmission of resources in men, but should also be open as to why women seem to be more responsive to their male partner’s perception of support and role balance, and not the other way around (i.e., women may be responding with empathy rather than receiving any tangible benefit from their partners). Gender socialization, roles, and expectations should thus be considered to better understand the asymmetrical effects found in our study. Practitioners can help men and women explore their distinct meanings of social support, work-life balance, and life satisfaction, as well as the contribution that their partner makes to these positive resources and experiences.

Another implication from our study is the need for policymakers and organizations to adopt the work-life balance standpoint. The workplace continues to function by assuming a man-breadwinner and woman-housemaker model (Yucel and Latshaw 2020), focusing on family policies. Instead, workers fulfill multiple life roles. Findings in our study, in agreement with previous research, showed that WLB is beneficial for individuals’ life satisfaction; furthermore, it showed that fathers’ WLB can cross over to mothers’ life satisfaction. Moreover, fathers’ perceived family support also had a positive association with mothers’ WLB. Hence, workplace policies and interventions should provide support for men and women to homogenize and balance their roles not only in the workplace, but also within the family (Cerrato and Cifre 2018), as well as in domains beyond work and family. The latter is a particularly pressing issue for mothers whose well-being as workers remains confined to their roles in the work-family interface.

Conclusions

The present study contributes to understanding the relationship between work-life balance and life satisfaction, involving perceived family support as a resource to enhance this relationship in different-sex dual-earner parents with adolescent children. Individually, each parent’s perceived family support had a positive effect on their own life satisfaction, directly and via work-life balance. On the other hand, the effect of one parent on the other in these variables depended on the gender of actor and partner. Neither mothers’ family support nor their work-life balance showed effects on fathers’ work-life balance nor life satisfaction. On the other hand, fathers’ family support had a positive effect on mother’s work-life balance, as did fathers’ work-life balance on mothers’ life satisfaction. Work-life balance appears to be beneficial for women, as both actor and partner in a dual-earner relationship. Nevertheless, the asymmetrical partner effects found in our study suggest that gender dynamics should be considered as a key variable in work-life interface research.

References

Abbott, P., Nativel, C., & Wallace, C. (2013). Dual earner parents’ strategies for reconciling work and care in seven European countries. Observatoire de la Société Britannique, 14, 73–97. https://doi.org/10.4000/osb.1521.

Adimark. (2004). Mapa Socioeconómico de Chile [Socioeconomic Map of Chile]. Retrieved from http://www.comunicacionypobreza.cl/wp-content/uploads/2004_Mapa_Socioeconomico_-de_-Chile.pdf.

Brough, P., Timms, C., O'Driscoll, M. P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2014). Work-life balance: A longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(19), 2724–2744. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.899262.

Cerrato, J., & Cifre, E. (2018). Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01330.

Chrishianie, C., Soekandar, A., & Primasari, I. (2018). Marital satisfaction in dual-earner marriage: Single-residence versus commuter. Psychological Research on Urban Society, 1(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.7454/proust.v1i1.21.

Claxton, S. E., DeLuca, H. K., & van Dulmen, M. H. M. (2015). Testing psychometric properties in dyadic data using confirmatory factor analysis: Current practices and recommendations. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 22(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM22.2.2.

Davis, K., Lawson, K., Almeida, D., Kelly, E., King, R., Hammer, L., & …McHale, S. (2015). Parents’ daily time with their children: A workplace intervention. Pediatrics, 135(5), 875–882. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2057.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 266–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.07.001.

Drummond, S., O’Driscoll, M. P., Brough, P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Timms, C., … Lo, D. (2017). The relationship of social support with well-being outcomes via work-family conflict: Moderating effects of gender, dependants and nationality. Human Relations, 70(5), 544–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716662696.

Fan, W., Lam, J., Moen, P., Kelly, E., King, R., & McHale, S. (2015). Constrained choices? Linking employees’ and spouses’ work time to health behaviors. Social Science and Medicine, 126, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.015.

Ferguson, M., Carlson, D. S., Zivnuska, S., & Whitten, D. (2012). Support at work and home: The path to satisfaction through balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.001.

Fuller, C., Simmering, M., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69, 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008.

Gragnano, A., Simbula, S., & Miglioretti, M. (2020). Work-life balance: Weighing the importance of work-family and work-health balance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 907–927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030907.

Haar, J. M. (2013). Testing a new measure of work-life balance: A study of parent and non-parent employees from New Zealand. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(17), 3305–3324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.775175.

Haar, J., & Brougham, D. (2020). Work antecedents and consequences of work-life balance: A two sample study within New Zealand, vol 1. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, p. 24. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1751238.

Haar, J., Russo, M., Suñe, A., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2014). Outcomes of work-life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85, 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.010.

Haar, J., Sune, A., Russo, M., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2019). A cross-national study on the antecedents of work-life balance from the fit and balance perspective. Social Indicators Research, 142, 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1875-6.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130.

Han, W.-J., Miller, D. P., & Waldfogel, J. (2010). Parental work schedules and adolescent risky behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1245–1267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020178.

Hobfoll, S. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Hobfoll, S. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640.

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 57–80). London: Routledge.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jensen, J., Rauer, A., & Volling, B. (2013). A dyadic view of support in marriage: The critical role of men’s support provision. Sex Roles, 68, 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0256-x.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Kerr, M., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation. New York: W.W. Norton.

King, L. A., Mattimore, L. K., King, D. W., & Adams, G. A. (1995). Family support inventory for workers: A new measure of perceived social support from family members. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160306.

Lee, E. S., & Shin, Y. J. (2017). Social cognitive predictors of Korean secondary school teachers' job and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.008.

Leung, Y., Mukerjee, J., & Thurik, R. (2020). The role of family support in work-family balance and subjective well-being of SME owners. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(1), 130–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1659675.

Liu, H., & Cheung, F. M. (2015). Testing crossover effects in an actor-partner interdependence model among Chinese dual-earner couples. International Journal of Psychology, 50(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12070.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Cai, L. (2006). Testing differences between nested covariance structure models: Power analysis and null hypotheses. Psychological Methods, 11(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.19.

Matias, M., Ferreira, T., Vieira, J., Cadima, J., Leal, T., & Mena Matos, P. (2017). Workplace family support, parental satisfaction, and work-family conflict: Individual and crossover effects among dual-earner couples. Applied Psychology, 66, 628–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12103.

McDonald, R. P. (1970). Theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 23, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1970.tb00432.x.

Meier, A., Musick, K., Fischer, J., & Flood, S. (2018). Mothers' and fathers' well-being in parenting across the arch of child development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(4), 992–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12491.

Mella, R., González, L., D’appolonio, J., Maldonado, I., Fuenzalida, A., & Díaz, A. (2004). Factores asociados al bienestar subjetivo en el adulto mayor [factors associated with subjective well-being in older adults]. Psykhe, 13(1), 79–89.

Park, Y., & Fritz, C. (2015). Spousal recovery support, recovery experiences, and life satisfaction crossover among dual-earner couples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037894.

Pedersen, D. (2014). Spillover and crossover of work-to-family conflict and the health behaviors of dual-earner parents with young children. Sociological Focus, 47(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2014.855980.

Perrone, K., Webb, L., & Jackson, Z. (2007). Relationships between parental attachment, work and family roles, and life satisfaction. The Career Development Quarterly, 55, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00080.x.

Pinto, C., Lara, R., Espinoza, E., & Montoya, P. (2014). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de apoyo social percibido de Zimet en personas mayores de atención primaria de salud [Psychometric properties of Zimet’s perceived social support scale in older adults in primary health care facilities]. Index de Enfermería, 23(1–2), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1132-12962014000100018.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., & Porsakoff, N. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2014). Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don't children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12095.

Rajani, N. B., Skianis, V., & Filippidis, F. T. (2019). Association of environmental and sociodemographic factors with life satisfaction in 27 European countries. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 534–541. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6886-y.

Russo, M., Shteigman, A., & Carmeli, A. (2015). Workplace and family support and work-life balance: Implications for individual psychological availability and energy at work. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1025424.

Schnettler, B., Denegri, M., Miranda, H., Sepúlveda, J., Orellana, L., Paiva, G., … Grunert, K. (2013). Hábitos alimentarios y bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios del Sur de Chile [eating habits and subjective well-being in university students from southern Chile]. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 28(6), 2221–2228. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2013.28.6.6751.

Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Lobos, G., Saracostti, M., Denegri, M., Lapo, M., … Hueche, C. (2018). The mediating role of family and food-related life satisfaction in the relationships between family support, parent work-life balance and adolescent life satisfaction in dual-earner families. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), E2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112549.

Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Grunert, K.G., Lobos, G., Lapo, M., & Hueche, C. (2020a). Testing the spillover-crossover model between work-life balance and satisfaction in different domains of life in dual-earner households. Applied Research in Quality of Life. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09828-z.

Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Grunert, K., Lobos, G., Lapo, M., & Hueche, C. (2020b). Satisfaction with food-related life and life satisfaction: A triadic analysis in dual-earner parent families. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(3), e00090619. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00090619.

Steiner, R., & Krings, F. (2016). How was your day, darling? A literature review of positive and negative crossover at the work-family interface in couples. European Psychologist, 21(4), 296–315. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000275.

Terrazas-Carrillo, E., McWhirter, P. T., & Muetzelfeld, H. K. (2016). Happy parents in Latin America? Exploring the impact of gender, work-family satisfaction, and parenthood on general life happiness. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 3(2), 140–161. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHD.2016.079596.

Tisdale, S., & Pitt-Catshupes, M. (2012). Linking social environments with the well-being of adolescents in dual-earner and single working parent families. Youth & Society, 44, 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X10396640.

Vaca, I. (2019). Oportunidades y desafíos para la autonomía de las mujeres en el futuro escenario del trabajo. Asuntos de Género, N° 154 (LC/TS.2019/3) [Opportunities and challenges to women’s autonomy in the future work scenario]. Santiago: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL).

Viñas-Bardolet, C., Guillen-Royo, M., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2019). Job characteristics and life satisfaction in the EU: A domains-of-life approach. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15, 1069–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09720-5.

Westman, M. (2001). Stress and strain crossover. Human Relations, 54(6), 717–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701546002.

Westman, M., & Vinokur, A. D. (1998). Unraveling the relationship of distress levels within couples: Common stressors, empathic reactions, or crossover via social interaction? Human Relations, 51(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016910118568.

Xu, D., Mou, H., Gao, J., Zhu, S., Wang, X., Ling, J., … Wang, K. (2019). Quality of life of nursing home residents in mainland China: The role of children and family support. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 83, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.04.009.

Yucel, D., & Latshaw, B. (2020). Spillover and crossover effects of work-family conflict among married and cohabiting couples. Society and Mental Health, 10(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869318813006.

World Health Organization. (2020). Adolescent health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Availability of Data and Material

Data is available upon request to the authors.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development [Fondecyt] of the Government of Chile. The results presented here correspond to Fondecyt Projects 1160005 and 1190017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

All participants in this research signed informed consent in accordance with ethical guidelines regarding the confidential treatment of the data. More information can be found in the manuscript, in the Procedure and measures subsection in Method.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orellana, L., Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E. et al. Resource Transmission is not Reciprocal: A Dyadic Analysis of Family Support, Work-Life Balance, and Life Satisfaction in Dual-Earner Parents with Adolescent Children. Sex Roles 85, 88–99 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01207-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01207-0