Abstract

Because female rape survivors who are listened to and believed have been found to have fewer difficulties, it is essential that researchers examine factors that influence the social reactions survivors receive. The present experiment included 397 female U.S. college-students who were randomly assigned to read a vignette that either reflected an acknowledged rape survivor (i.e., used the word “rape” to describe the incident) or described an unacknowledged rape survivor (e.g., used the word “miscommunication” to describe the incident). The college women then answered questions about their own levels of rape myth rejection and indicated on measures of positive social reactions, negative social reactions, and victim blame how they would respond to the hypothetical rape survivor. The results demonstrated that the female participants’ answers on positive social reactions and victim blame were a function of both the survivors’ acknowledgment status and the participants’ rape myth rejection. The interaction was not supported for negative social reactions, but this non-finding may have stemmed from a restricted range of variance and overall low scores on that variable. The results are discussed in the context of both individual and systemic interventions that may lead to more positive, helpful, and affirming responses to survivors via the reduction of rape myths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A series of highly publicized events (e.g., accusations against Harvey Weinstein), large-scale demonstrations (e.g., Women’s March on Washington in 2017), and widespread social media campaigns (e.g., #MeToo) have contributed to a growing dialogue about the frequency of sexual violence and best practices for preventing such violence. In addition to generating important conversations about the pervasiveness of sexual violence and the deleterious effects of victimization on survivors, these recent events have also prompted messaging that is potentially harmful to survivors. For example, several political figures publicly mocked the testimony given by Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who accused now U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault (Dawsey and Sonmez 2018). Given that female survivors who are listened to and believed have been found to have fewer psychological and physical symptoms (Campbell et al. 2001; Ullman 1996b), it is essential that researchers examine factors that influence the social reactions survivors receive.

It is well accepted that the majority of rape survivors discuss their victimization with at least one person (Aherns et al. 2007; Ullman and Filipas 2001). Furthermore, existing data suggest that the majority of survivors receive negative social reactions from at least one of those people (Filipas and Ullman 2001). This response is concerning given that one negative social reaction (e.g., victim blaming) can outweigh the beneficial effects of multiple positive responses (e.g., believing the survivor; Campbell et al. 2009). Overall, there is building empirical evidence that the social reactions a survivor receives are an essential element in the facilitation of their recovery (Campbell et al. 2009; Ullman 2010; Ullman and Peter-Hagene 2014). For example, Ullman and Peter-Hagene (2014) found that positive social reactions were associated with a survivor reporting greater perceived control over their own recovery, which in turn was associated with fewer PTSD symptoms. Conversely, more negative social reactions have been linked to greater survivor self-blame and use of avoidant coping (Ullman 1996b). Another study found that negative social reactions increased PTSD symptoms via increased shame (DeCou et al. 2017). Despite the prior studies demonstrating that social reactions impact the psychological recovery of female sexual assault survivors, the literature examining factors that influence disclosure recipients is under-developed.

Information provided by the survivor about the event, such as emotion conveyed when describing the incident, is one factor that has been found to affect disclosure recipients. For example, female survivors who are perceived as more emotional (e.g., tearful) when describing their victimization are seen as more credible and less to blame for the incident (Klippenstine and Schuller 2012; Winkel and Koppelaar 1991). Prior research has suggested that this is because those survivors are perceived as presenting in a way that is more “typical” of a survivor (Klippenstine and Schuller 2012). One related variable that has received little attention in this context is the survivor’s conceptualization of their victimization experience, commonly called rape acknowledgment (Koss 1989). This may be particularly relevant because a meta-analysis demonstrated that 60% of female rape survivors are unacknowledged survivors, meaning that most survivors use non-victimizing language (e.g., “it was a miscommunication”) to describe their victimization experience (Wilson and Miller 2016). Given that the emotional information conveyed during disclosure impacts social reactions, it is possible that the language the survivor uses to describe the incident could also impact the reaction they receive.

Several studies have demonstrated that acknowledged rape survivors are significantly more likely to disclose their victimization to others than unacknowledged survivors (Layman et al. 1996; Littleton et al. 2006). However, it is important to note that the majority of survivors disclose their victimization regardless of whether or not they acknowledge their victimization as rape (e.g., 91% of acknowledged survivors, 80% of unacknowledged survivors; Littleton et al. 2006). What is less understood is how rape acknowledgment impacts social reactions received during the disclosure process. In the only known study on the topic, Littleton et al. (2006) found that acknowledged survivors reported significantly more egocentric reactions compared to unacknowledged survivors. However, their study found no differences in levels of victim blame, being treated differently, distraction, or taking control based on acknowledgment status.

Littleton et al. (2006) suggested that one explanation for why they largely failed to find differences is that people are increasingly rejecting false stereotypes about sexual victimization. In the present study, we hypothesized that acknowledged rape survivors would receive more positive social reactions, as well as lower levels of negative social reactions and victim blame, because they would be perceived as being more “typical” of sexual assault survivors by disclosure recipients and the incident would also be taken more seriously. Furthermore, based on the study conducted by Littleton et al., we posited that it may be more informative to study the impact of survivor rape acknowledgment on social reactions in the context of the disclosure recipient’s rejection of rape myths (i.e., an interaction).

Arguably, the most frequently studied and demonstrated predictor of social reactions is disclosure recipient’s gender. Specifically, women respond to female rape survivors more positively than men (Earnshaw et al. 2011). However, existing studies have suggested that this gender difference is actually attributable to women’s greater rejection of rape myths (Basow and Minieri 2011). Rape myths are “attitudes and beliefs that are generally false but widely and persistently held, and that serve to deny and justify male sexual aggression against women” (Lonsway and Fitzgerald 1994, p. 134). Thus, rape myth rejection has been demonstrated to be a crucial contributor to the way in which people respond to survivors given that it is linked to more positive social reactions. In fact, Ullman (1996a, p. 555) posited that “Perhaps the most important factor in real-life disclosures of traumatic events is the recipient of the disclosures who may determine both the type of reaction experienced by victims and the impact of that reaction on the victim.” Consistent with a large literature base (see Van der Bruggen and Grubb 2014, for a review), we hypothesized that greater rape myth rejection would be associated with more positive social reactions as well as lower negative social reactions and victim blame.

In sum, the aim of the present study was to examine whether there was an interaction between the rape acknowledgment of a female survivor in a hypothetical rape vignette and disclosure recipients’ rape myth rejection in relation to the social reactions the participant reported they would provide. Survivor rape acknowledgment was manipulated by randomly assigning participants to read one of two different versions of a hypothetical rape vignette, both with a female survivor and male perpetrator. Rape myth rejection was operationalized using a self-report measure, where higher scores indicated greater rejection of rape myths based on the scoring instructions of the measure (McMahon and Farmer 2011). The outcome variables in the present study included self-report measures of positive social reactions, negative social reactions, and victim blame (Davies et al. 2006; Ullman 2000).

Because prior research has shown that people who have experienced sexual assault themselves are more likely to be the recipients of disclosures and have increased empathy toward other survivors (Paul et al. 2014), we included a measure of sexual victimization history (Koss et al. 2007) to ensure the experimental groups did not significantly differ from each other on this relevant variable. If they do differ, this could be a potential alternative explanation for the results. Participants were restricted to only U.S. college women because gender has been found to impact rejection of rape myths and rates of sexual victimization (Breiding et al. 2014; Grubb and Turner 2012). Furthermore, prior research has found that female survivors are more likely to disclosure their sexual assault to a female peer (Orchowski and Gidycz 2012). We hypothesized that survivor rape acknowledgment would have a stronger relationship with social reactions (i.e., positive and negative social reactions, victim blame) among disclosure recipients who reported lower rape myth rejection than those who reported greater rape myth rejection.

Method

Participants

The analyzed sample consisted of 397 female U.S. college-students. The average age of the participants was 19.20 years (SD = 3.03, range = 17–49). The sample was predominantly Caucasian/White (n = 287, 72.3%), with 30 (7.6%) participants indicating that they identify their race/ethnicity as Hispanic/Latinx, 24 (6.0%) as African American/Black/African origin, 20 (5.0%) as Asian American/Asian Origin/Pacific Islander, 4 (1.0%) as Middle Eastern, 28 (7.1%) as Bi-racial or Multi-racial, and 4 (1.0%) selected “Other.” The majority of participants were first year undergraduate students (n = 234, 58.9%), whereas 80 (20.2%) were second years, 40 (10.1%) were third years, 37 (9.3%) were fourth years, and 6 (1.5%) were fifth years.

Procedure and Measures

The participants in the present study were primarily recruited through a university psychology subject pool (n = 361, 90.9%). The university psychology subject pool’s participants received course credit for their participation. We also recruited participants through Facebook to attempt to obtain a more diverse sample (n = 36, 9.1%). The exact same study description was used to recruit in the psychology subject pool and the Facebook post. The psychology subject pool and Facebook participants did not significantly differ on any of the variables of interest or demographic variables, except they were, on average, 1 year older, t(390) = −3.51, p = .001, and more likely to be an upperclassmen as opposed to a first year student, χ2(4, n = 397) = 123.52, p < .001.

The study was conducted as an online experiment that took approximately 30 min to complete. The study was advertised as examining how attitudes impact our memory of stressful events. We included a statement that explicitly stated that the content of the survey included questions about sexual violence history and descriptions of sexual violence, which could have potentially biased which participants self-selected to participate. Our study was reviewed and received approval by the Institutional Review Board at the university where the data collection was conducted. All participants indicated their consent by continuing with the online study after reading the informed consent information.

Sexual Experiences Survey-Short Form Victimization (SES-SFV)

Participants first completed the SES-SFV to assess prior sexual victimization experiences (Koss et al. 2007). The measure captured whether or not participants had experienced seven types of unwanted sexual experiences due to five different perpetrator tactics, resulting in a total of 35 items. These items used behavioral language to assess each experience so that participants did not have to acknowledge the experience as victimization to respond “yes.” Participants completed the questions in relation to the time period since their 14th birthday. The response options were revised so that the participants indicated if they had experienced each type of victimization (i.e., yes/no) rather than the number of times each type of victimization had occurred. Prior research has demonstrated high 2-week test-rest reliability and validity for the SES-SFV among college women (Johnson et al. 2017). The SES-SFV was administered to examine if the experimental groups differed on sexual victimization history. Within the analyzed sample, 147 (42.1%) responded “yes” to at least one item assessing sexual victimization history. Conversely, 205 (51.6%) responded “no” to all of the items, and 25 (6.3%) elected to not answer these questions. Random assignment worked in the present study because the two vignette groups did not significantly differ on victimization history, χ2(1, n = 372) = .37, p = .544, and therefore victimization history is not a viable alternative explanation for any observed group differences.

Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (UIRMAS)

This 22 item self-report measure was used to measure the participants’ agreement with myths about sexual violence (McMahon and Farmer 2011). Participants were asked to respond to each item using a 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) Likert scale. The UIRMAS comprises four subscales, which have been identified in prior research through factor analysis: She asked for it (6 items; e.g., “If a girl acts like a slut, eventually she is going to get into trouble”); He didn’t mean to (6 items; e.g., “When guys rape, it is usually because of their strong desire for sex”); It wasn’t really rape (5 items; e.g., “If a girl doesn’t say “no” she can’t claim rape”); and She lied (5 items; e.g., “A lot of times, girls who say they were rape agreed to have sex and then regret it”). Because the purpose of the current study was to assess the role of rape myths globally and not specific types of rape myths, we calculated a total score by summing responses across the items.

Consistent with the scoring instructions provided by the authors of the measure, higher UIRMAS scores indicated greater rape myth rejection. Therefore, we framed the construct as rape myth rejection rather than acceptance throughout the paper. This measure is a revised version of the instrument created by Payne et al. (1999) and reflects more current language than the original measure. Prior research has demonstrated adequate internal consistency and support for the factor structure of the revised measure (McMahon and Farmer 2011). Cronbach’s alpha for the UIRMAS in the current study was .90, demonstrating excellent internal consistency.

Hypothetical Rape Vignettes

Next, participants were randomly assigned to read one of two vignettes that depicted a hypothetical rape. The vignette was adapted from the hypothetical rape vignette used by Loughnan et al. (2013). The original vignette described a scenario where a woman was raped by a male acquaintance while on a date. The original version described the event in the third person and the tone was factual, like a police report. We revised the vignette so that it was presented from the perspective of the survivor in the first person and was written in a conversational style. The details of the vignette were based on common characteristics of rape incidents, including a female victim who was a college student, said “no” once, and froze during the incident (Bucher and Manasse 2011; Dunn et al. 1999). Also consistent with common characteristics of sexual assaults, the assault happened in the male perpetrator’s apartment, did not involve physical injury, and both parties consumed alcohol (Bucher and Manasse 2011; Dunn et al. 1999).

Research has shown that only 40% of female rape survivors describe their victimization experiences as “rape” (i.e., acknowledged survivors; Wilson and Miller 2016). Of the 60% who do not use the term “rape” to describe the incident (i.e., unacknowledged survivors), the most common term they use is” miscommunication” or they indicate that they are not sure what happened (Layman et al. 1996; Littleton et al. 2009). One of the vignettes in the present study presented a survivor who used the word “miscommunication” to describe what happened to her (i.e., miscommunication vignette). The second vignette presented a survivor who used the word “rape” to describe what happened to her (i.e., rape vignette). The scenarios were written so that the participant was asked to think of themselves as a friend of the survivor because prior research has shown that the most common disclosure recipient is a friend (Dunn et al. 1999). The miscommunication vignette was randomly assigned to 193 (48.6%) participants and the rape vignette was assigned to 204 (51.4%) participants.

Participants read the following vignette:

While reading the following text, please pretend that you receive a phone call from your friend, Michelle. She is a student who is in your major. You have known Michelle since you started college and you consider her to be a close friend. During that phone she says the following:

I was at a party last week and I met a guy named Chris. We hung out during the party and had a really good time. He seemed really nice. At the end of the night, we exchanged phone numbers and I went home. I didn’t hear from him for a few days, but then he called and asked me out. I was so excited to hear from him, so I said “yes” when he asked me out on a date. We went to see a movie on Saturday night and we got a few drinks afterwards. It was a lot of fun! He seemed like a good guy. When the bar closed, Chris asked if I wanted to go back to his place to hang out before he took me home. I was having a good time so I said “yes.” When we got there, we were sitting on the couch and we started kissing. I liked him so I kissed him back. Then, he started touching my breasts, and started kissing harder and harder. I pulled away and told him to stop. But, he became really angry and said “But, I thought you liked me?!?” I didn’t know what to do. I was having a good time on the date and I did like him. But, I wasn’t ready to have sex with him. I froze. Before I knew it, he was on top of me, pulled my pants down and was inside of me. I’m not sure what happened. I guess it was a miscommunication. [In the acknowledged vignette the last two sentence were replaced with “I was raped”.]

Manipulation Check

On the page after the vignette, participants were asked “How did she describe the event to you?” as a manipulation check. They had to select the correct answer from four options, which included miscommunication, bad sex, crime, and rape. The correct answer for the unacknowledged vignette group was miscommunication and for the acknowledged vignette group was rape. From the original sample, nine (2.3%) of the participants who were assigned to the acknowledged group and 19 (4.8%) of the participants who were assigned to the unacknowledged group answered the manipulation check item incorrectly and therefore were excluded from the analyzed sample.

Victim Blame

Next, participants completed 11 revised items from Davies et al. (2006) to assess victim blame. These items were revised to reflect the names from the vignettes used in our study. Participants responded to each item using a 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely) Likert scale to indicate how much they believed the victim was to blame for the incident. Four of the items were reverse worded, and this correction was made prior to creating a total score by summing the items, with higher scores indicating greater victim blame. An example item is “Do you think that Michelle was to blame for what happened because she didn’t try hard enough to escape?” The Cronbach’s alpha for these items was .74, which reflected adequate internal consistency.

Social Reactions Questionnaire (SRQ)

Lastly, participants completed a revised version of a 46-item self-report questionnaire, which assessed the type of social reaction they believed they would have toward the survivor in the vignette (Ullman 2000). The original measure was written to assess the types of social reactions rape survivors have received. We revised the wording of the measure to assess the type of social reactions the participant predicted they would give to the hypothetical survivor. Participants responded to each item using a 0 (very unlikely) to 4 (very likely) Likert scale. The SRQ consists of seven subscales: Emotional Support/Belief (15 items; e.g., “Listened to her feelings”), Treat Differently (6 items; e.g., “Pull away from her”), Distraction (6 items; e.g., “Distract her with other things”), Take Control (7 items; e.g., “Make decisions or do things for her”), Tangible Aid/Information Support (5 items; e.g., “Help her get medical care”), Victim Blame (3 items; e.g., “Tell her she could have done more to prevent the experience from occurring”), and Egocentric (4 items; e.g., “Express so much anger at the perpetrator that she has to calm you down”). These subscales can be grouped into positive social reactions (i.e., Emotional Support/Belief, Tangible Aid/Information Support) and negative social reactions (i.e., Treat Differently, Distraction, Take Control, Victim Blame, Egocentric) factors. In the analyses presented here, we examined the mean scores of the positive and negative social reaction factors. Ullman (2000) found that the SRQ has adequate reliability and factorial structure. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the positive reactions factor was.78 and for the negative reaction factor was .83, which both indicate adequate internal consistency.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS, Version 24. Linear regressions were used to examine the primary hypotheses, including the main effects of the vignette and UIRMAS, and the interaction between vignette and UIRMAS on the positive and negative factors of the SRQ and victim blame. The dichotomous main effect (i.e., vignette) was dummy coded (i.e., 0 = miscommunication or unacknowledged; 1 = rape or acknowledged) and the UIRMAS was mean-centered based on recommendations by Dawson (2014). Separate moderation models examined the positive SRQ factor, negative SRQ factor, and victim blame. The interaction term was created by taking the product of the mean-centered continuous main effect and the binary main effect. When the interaction term was significant, simple slopes were tested according to the procedures recommended by Holmbeck (2002).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Prior to analyzing the hypotheses, independent samples t-tests revealed that the participants who read the miscommunication and rape vignettes did not significantly differ on rape myth rejection, t(384) = −.67, p = .506, or age, t(390) = −.96, p = .339. Chi-square tests revealed that the participants who read the miscommunication and rape vignettes did not significantly differ in recruitment source, χ2(1, n = 397) = .77, p = .382, race/ethnicity, χ2(6, n = 397) = 5.23, p = .515, or year in school, χ2(4, n = 397) = 3.42, p = .490. Therefore, any observed differences on the outcome variables between the vignette groups cannot be attributed to these variables.

Means and standard deviations for the continuous variables are presented in Table 1. Pearson product moment correlations among the continuous variables are also presented in Table 1. Rape myth rejection was significantly positively correlated with the positive SRQ factor and significantly negatively correlated with the negative SRQ factor and victim blame. Victim blame was negatively correlated with the positive SRQ factor and positively correlated with the negative SRQ factor. As expected, the positive SRQ factor was significantly inversely correlated with the negative SRQ factor.

Hypothesis Testing

The results of the moderation analyses are presented in Table 2. The main effect of vignette was significant for the positive support SRQ model and victim blame, but not the negative support SRQ model. Specifically, reading the rape vignette was associated with greater positive support and less victim blame compared to reading the miscommunication vignette. These findings partially supported our first hypothesis that acknowledged rape survivors would receive more positive social reactions as well as lower levels of negative social reactions and victim blame.

The main effect of rape myth rejection was significant for positive SRQ, negative SRQ, and victim blame. Specifically, greater rape myth rejection was associated with greater positive support, lower negative support, and less victim blame. This series of findings is consistent with our second hypothesis.

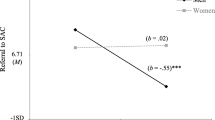

The interaction of vignette and rape myth rejection was significant for the positive support SRQ model. The simple slopes were examined to probe the significant interaction. The analyses indicated that the effect of survivor rape acknowledgment on positive support was significant for the low rape myth rejection group (b = .198, SE = .046, β = .293, t = 4.29, p < .001), but not the high rape myth rejection group (b = −.037, SE = .046, β = −.054, t = −.794, p = .428; see Fig. 1a). Therefore, we supported our interaction hypothesis for positive social reactions.

The interaction of vignette and rape myth rejection was significant for victim blame. The simple slopes were examined for the model including victim blame. The analyses indicated that the effect of survivor rape acknowledgment on victim blame was significant for the low rape myth rejection group (b = −4.09, SE = .868, β = −.295, t = −4.72, p < .001), but not the high rape myth rejection group (b = −1.01, SE = .866, β = −.073, t = −1.17, p = .243; see Fig. 1b). Thus, we supported our interaction hypothesis for victim blame.

The interaction of vignette and rape myth rejection was not significant for negative support SRQ model. Because the interaction was not significant, no further analyses were necessary. Therefore, we did not support our interaction hypothesis for negative social reactions.

Discussion

The present study extended existing research by examining the roles of survivor rape acknowledgment and disclosure recipient rape myth rejection in relation to social reactions among college women. The findings supported the presence of a main effect of survivor acknowledgment status for positive social reactions and victim blame but not negative social reactions. These results suggested that the hypothetical survivor’s use of the word “rape” was associated with more positive social reactions and less victim blame than when the hypothetical female survivor used the word “miscommunication.” The main effect of participant rape myth rejection was supported for all of the outcome variables, such that greater rejection of rape myths was associated with more positive reactions, lower negative reactions, and lower victim blame. The hypothesized interaction was supported for two of the three outcome variables. Specifically, an interaction between survivor acknowledgment status and participant rape myth rejection was supported for positive social reactions and victim blame, but not negative social reactions. Because the interaction between survivor acknowledgment status and participant rape myth rejection was significant, it is more informative to interpret the combined influence of these two variables rather than the main effects.

Overall, the findings of the present study suggest that the impact of the language the survivor uses to describe her victimization on the way people treat her must be considered within the context of characteristics of the disclosure recipient. This is consistent with Ullman (1996a) who emphasized the importance of the disclosure recipient. Specifically, the results suggested that participants who reject rape myths will provide more helpful, positive, and affirming reactions to survivors, regardless of the way the survivor describes the event to them. Conversely, the way in which survivors describe their victimization experiences to others will impact the way people treat them if those people report lower rejection of rape myths. Disclosure recipients who report low rejection of rape myths will respond more positively and with stronger support if the survivor uses the word “rape” as opposed to if the survivor uses the word “miscommunication.” This difference may be because these disclosure recipients are more likely to take the event and the impact of the event on the survivor seriously if the survivor uses the word “rape.” Otherwise, if the survivor uses the word “miscommunication,” then the disclosure recipient’s own biases and stereotypes may have a more powerful influence on the way they treat the survivor.

The findings of the present study may help us understand why Littleton et al. (2006) found that acknowledged and unacknowledged rape survivors largely did not differ in the social reactions they received. Because social reactions appear to be a function of both rape acknowledgment and rape myth rejection, it is too simplistic to only examine the influence of survivors’ rape acknowledgment. Although it was surprising that the main effect of vignette and the interaction were not supported for negative social reactions, it is possible that this is due to a restricted range of responses on that particular variable and overall low levels of negative reactions reported by participants (M = .54, SD = .33, Observed range of .00–2.12; Possible range = 0–4). It is also important to note that there was a ceiling effect so that participants, generally, reported high rates of rejecting rape myths. The average among the participants was 94.54 on a scale with a possible range of 22 to 110. This is consistent with other studies that generally find that victim blaming and exonerating beliefs about perpetrators are not widespread (Aherns and Campbell 2000; Van der Bruggen and Grubb 2014). As people’s beliefs and attitudes about sexual violence shift, it is possible that measurement adjustments will be needed to better capture the nature and degree of false and potentially harmful beliefs people hold about victimization.

The ∆R2 for the significant interactions terms (i.e., .030 for positive social reactions, .012 for victim blame; see Table 2) indicate small effect sizes and it is important to keep this in mind when interpreting our results. However, it is also important to note that prior research has shown that many interactions in social science research only account for between 1 and 3% of the variance, meaning that small effect sizes are common when examining interactions (Champoux and Peters 1987; Chaplin 1991). It is also important to consider that the two versions of the vignette largely differed in one key word (i.e., “rape” versus “miscommunication”). Therefore, the size of the difference observed between the vignette groups, which also contributed to the calculation of the interaction term, could have been attenuated because of the manipulation used. In real life, there would likely be more differences in the way an unacknowledged survivor would describe their victimization experiences to someone compared to an acknowledged survivor. Given that the vignettes differed in one core word and the hypothesis was supported for positive social reactions and victim blame, the results of the present study highlight how important it is to consider the impact of how survivors conceptualize their victimization experiences in the context of characteristics of the woman to whom they disclose.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several additional aspects of our study should be considered when interpreting the results and should be used to inform future research directions. First, the sample was restricted to U.S. college women who were predominantly Caucasian/White, first year undergraduate students, and mostly recruited from General Psychology classes. This is problematic because prior research has shown that demographic characteristics, such as gender and race/ethnicity, can impact social reactions given to survivors (Banyard et al. 2010; George and Martinez 2002). It is unclear whether the results of the present study would generalize to other recruitment sources (e.g., community samples) or more diverse samples (e.g., participants who do not predominantly identify as White/Caucasian or female). Future research should be dedicated to replicating these results in a more diverse sample.

Second, the vignettes depicted a sexual assault perpetrated by a man against a woman. Prior research, such as a study by Ballman et al. (2016), has demonstrated that participants respond differently to vignettes depicting same-gender sexual assault compared to mixed gender sexual assault. Follow-up research should incorporate different vignettes to examine the generalizability of our findings. Third, participants read a hypothetical rape vignette and completed self-report measures assessing how they would respond to the hypothetical survivor. Therefore, it is possible (if not likely) that the participants would respond differently to a real-life friend who had experienced sexual assault. Finally, we only examined one characteristic of the disclosure recipient (i.e., rape myth rejection). Future researchers should consider the impact of other relevant variables, such as attitudes about women’s sexuality, heterosexism and masculinity.

Practice Implications

The findings of the present study highlight the importance of educating college students about sexual victimization. Specifically, because participants who rejected rape myths reported more affirming and positive responses, regardless of the way the survivor described their victimization, one point of intervention for building more supportive social networks for survivors is through reducing rape myths among disclosure recipients. Many of the sexual violence prevention programs used on college campuses specifically aim to reduce belief in rape myths and many of them report success in doing so (e.g., Gidycz et al. 2001). Increasingly, scholars are also discussing the importance of systemic change rather than solely focusing on intervening at the individual level. For example, some scholars have pinpointed community leaders, such as leaders of religious groups, as an avenue through which more positive and supportive messaging toward survivors may occur (Hyman et al. 2000). But, the responsibility also falls on other individuals who have the opportunity to reach large audiences. Individuals who have a platform (e.g., journalists, politicians, attorneys, judges) have a duty to educate the public about what sexual victimization can and does look like, as well as to help challenge the misconceptions which contribute to victim blame.

Conclusions

Although the present study helped contribute to the field’s understanding of some of the factors that may impact how disclosure recipients respond to female rape survivors, future research is needed to more comprehensively consider additional factors that may play a role (e.g., attitudes toward women’s sexuality, heterosexism, masculinity) and to investigate these phenomena in more diverse samples (e.g., race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity). This future work should be of the highest priority because there is empirical evidence that reducing harmful and inaccurate beliefs about sexual violence is a key component to better supporting sexual assault survivors. Ultimately, this line of research supports the education of disclosure recipients so that they can meet survivors where they are on their path to recovery by providing survivor-affirming support that will facilitate disclosure and help seeking.

References

Aherns, C. E., & Campbell, E. (2000). Assisting rape victims as they recover from rape: The impact on friends. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 959–986. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626000015009004.

Aherns, C. E., Campbell, R., Ternier-Thames, N., Wasco, S. M., & Sefl, T. (2007). Deciding whom to tell: Expectations and outcomes of rape survivors’ first disclosures. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00329.x.

Ballman, A. D., Leheney, E. K., Miller, K. E., Simmons, B. L., & Wilson, L. C. (2016). Bystander perceptions of same-gender versus mixed-gender rape: A pilot study. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 10, 1079–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2016.1228019.

Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., Walsh, W. A., Cohn, E. S., & Ward, S. (2010). Friends of survivors: The community impact of unwanted sexual experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509334407.

Basow, S. A., & Minieri, A. (2011). “You owe me”: Effects of date costs, who pays, participant gender, and rape myth beliefs on perceptions of rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510363421.

Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Merrick, M. T. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization: National Intimate Partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. Surveillance Summaries, 63, 1–18.

Bucher, J., & Manasse, M. (2011). When screams are not released: A study of communication and consent in acquaintance rape situations. Women & Criminal Justice, 21, 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2011.558801.

Campbell, R., Ahrens, C. E., Sefl, T., Wasco, S. M., & Barnes, H. E. (2001). Social reactions to rape victims: Healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence and Victims, 16, 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.16.3.287.

Campbell, R., Dworkin, E., & Cabral, G. (2009). An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 10, 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334456.

Champoux, J. E., & Peters, W. S. (1987). Form, effect size, and power in moderated regression analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 60, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1987.tb00257.x.

Chaplin, W. F. (1991). The next generation of moderator research in personality psychology. Journal of Personality, 59, 143–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00772.x.

Davies, M., Pollard, P., & Archer, J. (2006). Effects of perpetrator gender and victim sexuality on blame toward male victims of sexual assault. The Journal of Social Psychology, 146, 275–291. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.3.275-291.

Dawsey, J., & Sonmez, F. (2018, October 2). Trump mocks Kavanaugh accuser Christine Blasey Ford. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-mocks-kavanaugh-accuser-christine-blasey-ford/2018/10/02/25f6f8aa-c662-11e8-9b1c-a90f1daae309_story.html.

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7.

DeCou, C. R., Cole, T. T., Lynch, S. M., Wong, M. M., & Matthews, K. C. (2017). Assault-related shame mediates the association between negative social reactions to disclosure of sexual assault and psychological distress. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 9, 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000186.

Dunn, P. C., Vail-Smith, K., & Knight, S. M. (1999). What date/acquaintance rape victims tell others: A study of college student recipients of disclosure. Journal of American College Health, 47, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448489909595650.

Earnshaw, V. A., Pitpitan, E. V., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2011). Intended responses to rape as functions of attitudes, attributions of fault, and emotions. Sex Roles, 64, 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9920-1.

Filipas, H. H., & Ullman, S. E. (2001). Social reactions to sexual assault victims from various support sources. Violence and Victims, 16, 673–692.

George, W. H., & Martinez, L. J. (2002). Victim blaming in rape: Effects of victim and perpetrator race, type of rape, and participant racism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00049.

Gidycz, C A., Layman, M. J., Rich, C. L., Crothers, M., Gylys, J., Matorin, A., … Jacobs, C. D. (2001). An evaluation of an acquaintance rape prevention program: Impact on attitudes, sexual aggression, and sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16, 1120–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626001016011002.

Grubb, A., & Turner, E. (2012). Attribution of blame in rape cases: A review of the impact of rape myth acceptance, gender role conformity and substance use on victim blaming. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5, 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.002.

Holmbeck, G. N. (2002). Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies on pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87.

Hyman, I., Guruge, S., Stewart, D. E., & Ahmad, F. (2000). Primary prevention of violence against women. Women's Health Issues, 10, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1049-3867(00)00066-9.

Johnson, S. M., Murphy, M. J., & Gidycz, C. A. (2017). Reliability and validity of the sexual experiences survey-short forms victimization and perpetration. Violence and Victims, 32, 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-15-00110.

Klippenstine, M. A., & Schuller, R. (2012). Perceptions of sexual assault: Expectancies regarding the emotional response of a rape victim over time. Psychology, Crime & Law, 18, 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2011.589389.

Koss, M. P. (1989). Hidden rape: Sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of students in higher education. In M. A. Pirog-Good & J. E. Stets (Eds.), Violence in dating relationships: Emerging social issues (pp. 145–184). New York: Praeger.

Koss, M. P., Abbey, A., Campbell, R., Cook, S., Norris, J., Testa, M., … White, J. (2007). Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x.

Layman, M. J., Gidycz, C. A., & Lynn, S. J. (1996). Unacknowledged versus acknowledged rape victims: Situational factors and posttraumatic stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.105.1.124.

Littleton, H. L., Axsom, D., Breitkopf, C. B., & Berenson, A. (2006). Rape acknowledgment and postassault experiences: How acknowledgment status relates to disclosure, coping, worldview, and reactions received from others. Violence and Victims, 21, 761–778. https://doi.org/10.1891/vv-v21i6a006.

Littleton, H. L., Axsom, D., & Grills-Taquechel, A. (2009). Sexual assault victims’ acknowledgement status and revictimization risk. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01472.x.

Lonsway, K. A., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1994). Rape myths: In review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 133–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00448.x.

Loughnan, S., Pina, A., Vasquez, E. A., & Puvia, E. (2013). Sexual objectification increases rape victim blame and decreases perceived suffering. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37, 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313485718.

McMahon, S., & Farmer, G. L. (2011). An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Research, 35, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/35.2.71.

Orchowski, L. M., & Gidycz, C. A. (2012). To whom do college women confide sexual assault? A prospective study of predictors of sexual assault disclosure and social reactions. Violence Against Women, 18, 264–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212442917.

Paul, L. A., Kehn, A., Gray, M. J., & Salapska-Gelleri, J. (2014). Perceptions of, and assistance provided to, a hypothetical rape victim: Differences between rape disclosure recipients and nonrecipients. Journal of American College Health, 62, 426–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.917651.

Payne, D. A., Lonsway, K. A., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1999). Rape myth acceptance: Exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois rape myth acceptance scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 27–68. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238.

Ullman, S. E. (1996a). Correlates and consequences of adult sexual assault disclosure. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 11, 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626096011004007.

Ullman, S. E. (1996b). Social reactions, coping strategies, and self-blame attributions in adjustment to sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 505–526.

Ullman, S. E. (2000). Psychometric properties of the social reactions questionnaire. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00208.x.

Ullman, S. E. (2010). Talking about sexual assault: Society’s response to survivors. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ullman, S. E., & Filipas, H. H. (2001). Correlates of formal and informal support seeking in sexual assaults victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16, 1028–1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626001016010004.

Ullman, S. E., & Peter-Hagene, L. (2014). Social reactions to sexual assault disclosure, coping, perceived control, and PTSD symptoms in sexual assault victims. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21624.

Van der Bruggen, M., & Grubb, A. (2014). A review of the literature relating to rape victim blaming: An analysis of the impact of observer and victim characteristics on the attribution of blame in rape cases. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19, 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.008.

Wilson, L. C., & Miller, K. E. (2016). Meta-analysis of the prevalence of unacknowledged rape. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 17, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015576391.

Winkel, F. W., & Koppelaar, L. (1991). Rape victims’ style of self-presentation and secondary victimization by the environment: An experiment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 6, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626091006001003.

Acknowledgements

Laura C. Wilson, Department of Psychological Science, University of Mary Washington; Hannah R. Truex, Department of Psychological Science, University of Mary Washington; Madeleine C. Murphy-Neilson, Department of Psychological Science, University of Mary Washington; Kristen P. Kunaniec, Department of Psychological Science, University of Mary Washington; Jordan T. Pamlanye, Department of Psychological Science, University of Mary Washington; Rebecca A. Reed, Department of Psychological Science, University of Mary Washington.

Funding

The authors did not receive funding for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest involving this project.

Ethics Approval

IRB approval was obtained at the university of origin.

Consent to Participate

All participants gave informed consent and the consent process was approved by the IRB.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, L.C., Truex, H.R., Murphy-Neilson, M.C. et al. How Female Disclosure Recipients React to Women Survivors: The Impact of Rape Acknowledgment and Rejection of Rape Myths. Sex Roles 84, 337–346 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01169-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01169-3