Abstract

We examined mothers’ beliefs about gender-typed values and activities and their associations with the academic skills (i.e., math and reading/language arts) and engagement (i.e., emotional engagement in school) of their adolescent children (13–15 years-old) in a U.S. sample of Black, Chinese American, Latinx, and White families (n = 158). Mothers were more likely to endorse gender-typed activities (e.g., “Boys shouldn’t play with dolls”) than gender-typed values (e.g., “Men should make the important decisions in the family”). We found that Chinese American and Latina mothers endorsed more traditional gender-typed beliefs than Black mothers, who endorsed more traditional beliefs than White mothers. Adjusting for race/ethnicity and prior academic outcomes, mothers’ endorsement of gender-typed values was associated with lower emotional engagement in school for male adolescents. In addition, adjusting for race/ethnicity and prior academic outcomes, mothers’ endorsement of gender-typed activities was associated with lower math grades for female adolescents, lower emotional engagement in school for young men, and higher emotional engagement in school for young women. Mothers’ endorsement of gender-typed values and activities was not associated with reading/language arts grades for either male or female adolescents. Our findings have important implications for understanding the processes through which mothers’ gender attitudes may be conveyed and enacted in adolescents’ behavior within the school setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The study of gender socialization has underscored the critical influence of parents’ expectations, values, and beliefs on children’s development. Conceptualizations of gender socialization processes draw from social learning theories that highlight adults’ direct reinforcement of children’s gender-typed behavior (and tacit discouragement of gender-atypical behavior), as well as indirect, observational learning on the part of children taking place while parents do and say some things and do not do and say others (Bandura 1986; Maccoby 1998; Mischel 1970). The gender socialization processes that take place during such transactions have been linked to the activities in which children engage (Leaper 2002; Owen Blakemore et al. 2008; Simpkins et al. 2012). their developing skills and interests (Bian et al. 2017; Bronstein 2006; Crowley et al. 2001), and their conceptions of gender, including expectations regarding gender-typical and gender-atypical behavior (Epstein and Ward 2011; Martin and Dinella 2002; Simpkins et al. 2015).

Researchers have also noted that parents’ adherence to traditional beliefs about gender-typed values and activities (e.g., believing that boys should play with stereotypically male toys like trucks whereas girls should play with stereotypically female toys like dolls) is associated with lower levels of academic performance in children (Hoffman and Kloska 1995). Moreover, parents’ beliefs about and behaviors toward children’s academic abilities are often differentiated by their child’s gender, with parents of sons being less likely to encourage reading and writing abilities (Heyder et al. 2017) and parents of daughters being less likely to encourage math and science skills (Tomasetto et al. 2011).

Although, overall, the body of research on gender socialization has advanced our understanding of its processes related to children’s academic development, it is limited in a number of ways. First, the focus has been almost exclusively on early and middle childhood (see Martin and Ruble 2010) and the correlates that are most appropriate for studying gender socialization of young children, such as gender categorization and engagement in gender-stereotypic activities. Although several studies address how parents’ beliefs about their children’s subject-specific academic abilities predict gender differences in performance (Gunderson et al. 2012), only few have examined the ways in which more general gender-based beliefs may be associated with, for example, the academic performance of older adolescents.

Second, most scholars have examined associations among gender socialization variables with academic achievement concurrently, failing to account for children’s prior academic performance (but see Halpern and Perry-Jenkins 2016). Third, the rates of endorsement of both gender-typed activities (e.g., playing sports being only appropriate for boys) and values (e.g., being more important to educate boys than girls) have typically been collapsed. The conflation of parents’ endorsements of gender-typed activities with values assumes that the correlates of such activities and values would be similar; however, parents’ beliefs may diverge on these two aspects, and each set of beliefs may have differential effects on children’s academic development (Hoffman and Kloska 1995).

Fourth, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that adolescents’ gender informs the content of academic stereotypes, whereby male adolescents are typically socialized to be less engaged in school and more proficient in math and science than female adolescents, whereas young women are socialized to be more engaged in academics and more proficient in reading and language than young men. However, these different expectations have not been studied in relation to the association between parents’ gender beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes.

Finally, past research on associations between gender socialization processes and academic outcomes has vastly underrepresented U.S. Black, Latinx, and Asian American families, underscoring the critical need to investigate processes of gender socialization among ethnic-minority families using an intersectional approach (Else-Quest and Hyde 2016). With ethnic minority youth currently representing 49% of all youth under 17 years-old in the United States (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics 2018), the need to prioritize Families of Color is imperative. In order to address these limitations, we explored gender socialization (i.e., mothers’ beliefs about gender-typed values and activities) and its association with math and language arts grades and academic engagement within a sample of Black, Latinx, Asian American, and White mothers and their adolescent children.

Mothers’ Beliefs about Gender-Typed Values and Activities

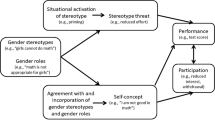

Mothers’ gender socialization is thought to occur through the iterative process of social learning, whereby children (a) observe gender-related information from the social worldb (b) behave in ways that are either punished or rewarded according to mothers’ gender beliefs, and (c) re-integrate information based on this reinforcement into their development of schemas (i.e., working models of what is appropriate for each gender) (Bandura 1986; Bussey and Bandura 1999; Mischel 1970). The transmission of stereotypes can occur both directly—for example when a mother tells her son that “Boys don’t cry”—as well as indirectly. Indirect socialization would include (a) observational learning on the part of children—for example, a daughter seeing her mother, but not her father, spend many hours engaged in housework and (b) communications from mothers that implicitly convey gender-typed messages—for example when a mother responds positively when her daughter plays with dolls but not when she plays with trucks. Children and adolescents are motivated through continual reinforcement to align their behaviors with internalized gender schemas (Martin and Ruble 2010).

A vast majority of gender socialization studies based on social learning perspectives has focused on mothers’ actual behaviors. This research examined how mothers more directly engage with their sons and daughters along gender-typed lines—for example by offering gender-typical, and not gender-atypical, toys to their children during play (Jacklin et al. 1984) or by assigning traditionally masculine household chores like mowing the lawn to sons and traditionally feminine tasks like childcare to daughters (Gaskins 2015; Grusec et al. 1996). Often, reviews and meta-analyses of these studies found more similarities than differences in how mothers treat their sons in comparison to their daughters (Endendijk et al. 2016; Lytton and Romney 1991; McHale et al. 2003), resulting in questions about whether there are any “real” differences in how most mothers shape children’s experiences by gender. Most researchers concluded that given the complexity of gender socialization processes and the ways these processes likely interact with children’s environments, more subtle and multifaceted methods are necessary to adequately examine the role of mothers in the gender socialization of children (see Ruble et al. 2006, for a review).

Thus, researchers have moved to examining the indirect role of mothers’ gender-typed beliefs in an effort to access the subtle pathways through which gender socialization is enacted (Freeman 2007; Mesman and Groeneveld 2018; Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002). Mothers’ explicit beliefs about gender-typed values and activities are thought to underlie the implicit messages children receive regarding expectations for gender-typed behaviors (McHale et al. 2003; Ruble et al. 2006). Accordingly, scholars have assessed mothers’ gender-typed beliefs in an effort to profile parental beliefs as well as to measure how closely they align with children’s gender-typed beliefs (e.g., Endendijk et al. 2013; McHale et al. 2003). Some researchers have found that mother’s gender stereotypes about children (e.g., “Boys who exhibit ‘sissy’ behavior will never be well adjusted”) predict their children’s gender beliefs (Endendijk et al. 2013). One meta-analysis demonstrated a small but non-trivial association (r = .16) between parents’ and children’s gender beliefs (Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002), suggesting that parents’ gender beliefs do play a role in children’s development and merit attention in studies of gender socialization.

It is unlikely, however, that “gender beliefs” among mothers are a singular thing. Rather, it is probable that gender beliefs should be considered from a multi-faceted perspective (Bigler 1997; Martin 1993; Signorella 1999; Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002). For instance, one mother could have highly traditional views concerning both gender-typed values (e.g., that only men should make the important decisions families) and gender-typed activities (e.g., that children should be involved in gender-typical and not gender-atypical activities—such as football for boys and ballet for girls), whereas another mother could hold more egalitarian values regarding family roles while still endorsing gender-typical (and not atypical) activities for her children. If the differences between mothers’ beliefs in these two domains were not disentangled, the second mother would look moderate on a scale of general gender-typed beliefs, although she in fact strongly rejected traditional beliefs in terms of gender-typed values and strongly endorsed traditional beliefs in terms of gender-typed activities for children. In most studies however, these two strands of gender-typed beliefs are combined and differences are not disentangled. (See Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002, for a discussion of how measures are used across studies of maternal gender beliefs.) It remains unclear whether mothers’ beliefs regarding gender-typed activities and values play differential roles in adolescents’ outcomes so that studies are needed to examine different types of gender beliefs among mothers.

Ethnic Differences in Mother’s Gender Beliefs

As we might expect mothers’ gender beliefs to differ across domains, so we might also expect differences in mothers’ gender beliefs across ethnic groups due to knowledge about cultural beliefs that are gendered. Little attention has been paid to cultural differences in U.S. mothers’ gender-typed beliefs, although current evidence suggests that there may be marked differences in mothers’ beliefs across cultural or ethnic lines (Abrams et al. 2016; Jones et al. 2018; Leaper 2002; McHale et al. 2003). Specifically, Black women typically reject traditional gender beliefs associated with White middle-class women like passivity but endorse traits that have been deemed both masculine (strength and independence) and feminine (nurturing others and valuing physical appearance) (Cole and Zucker 2007). Latina women typically endorse more traditional gender beliefs than other ethnic groups, such as the Marianismo stereotype of docility and devotion to domestic and family life (Denner and Dunbar 2004; Raffaelli and Ontai 2004). Other scholars have shown, however, that many Latinas value the Hembrisimo (“super woman”) role—a more masculinized norm of strength, confidence, and tenacity. Along parallel lines, surveys on cultural trends suggest that at least explicitly, White mothers in the United States increasingly espouse egalitarian gender beliefs (Gerson 2009).

Despite the documentation of these differences and the increasing ethnic diversity among mothers and children in the United States., empirical studies on mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ functioning in ethnically diverse samples are lacking, and little is known about how differences in maternal beliefs filter through to children’s functioning. Studies that do not include racially/ethnically diverse participants may be missing important patterns of association between parents’ gender-typed beliefs and adolescents’ outcomes. Conversely, studies that do include ethnically diverse participants but do not account for ethnicity in examining parents’ gender-typed beliefs may have overlooked important systematic sources of variation in these beliefs (Else-Quest and Hyde 2016).

Gender Socialization and Academic Outcomes

Researchers investigating relations among gender beliefs and academic outcomes draw on empirical and historical evidence showing long-standing cultural ideologies linking gender to specific intellectual or scholastic domains. Kagan (1964) was the first known to observe that elementary school-aged children classify school-related objects, behaviors, and intellectual skills as either masculine or feminine. For example, masculinity has been historically been linked to domains thought to require intellectual brilliance, such as in math and science (Nosek et al. 2009; Leslie et al. 2015), whereas femininity has been associated with areas requiring emotional attunement and depth, such as in reading and writing (Halpern et al. 2011; Plante et al. 2009). The pervasiveness of such ideologies underscores scholars’ motivations to understand whether gender beliefs, either among parents or youth, are actually associated with performance in domains that have been historically and culturally gendered.

Numerous researchers have investigated the association between parents’ gender beliefs and their children’s academic outcomes, and they have found that mothers’ gender beliefs are associated with child outcomes—particularly children’s own gender beliefs (Endendijk et al. 2013; Gutman and Eccles 1999; Hoffman and Kloska 1995; Simpkins et al. 2012; Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002). Still, few studies have examined how such beliefs may influence children’s performance. The few studies that do examine such processes find an association between parents’ gender beliefs and their child’s academic outcomes (Fredricks and Eccles 2002; Hoffman and Kloska 1995), whereas others have not (Lytton and Romney 1991; Raymond and Persson Benbow 1986).

The small body of research concerning the influence of parents’ gender beliefs on their children’s academic outcomes is limited in a few key ways. A majority of studies that demonstrate differences in parental beliefs and behavior according to child gender do so in samples of parents of young children, where evidence regarding actual differences in children’s skills in early grades has been widely contested (DiPrete and Jennings 2012; Hyde et al. 2008; Robinson and Lubienski 2011). For example, there is some evidence that girls tend to outperform boys in reading beginning in kindergarten and throughout elementary school (Chatterji 2006; DiPrete and Jennings 2012). Others have found marked gender differences in academic performance do not emerge until either late elementary school or early middle school (Entwisle et al. 2007). Scholars tend to agree, however, that gender differences in academic outcomes are firmly established by the onset of adolescence (Kessels et al. 2014; Ueno and McWilliams 2010; Voyer and Voyer 2014), a period coinciding with the intensification of gender-stereotype learning (Crouter et al. 2007; Hill and Lynch 1983).

Early childhood scholars point out that gender-based skill differences are typically small in very young children. Yet, parents have different evaluations of their son’s or daughter’s skills based on the child’s gender. For example, Tenenbaum and Leaper (2003) demonstrated differences in how parents perceived young children’s science skills by child gender, although the science performance of boys and girls was in fact equivalent. Such studies seem to indicate that although evaluations differ by gender, such beliefs about abilities are not linked to children’s outcomes. However, virtually no studies consider the link between mothers’ gender-typed beliefs and adolescents’ academic functioning, although gender differences are particularly salient and intensify for youth during adolescence (Crouter et al. 2007; Galambos et al. 1990; Hill and Lynch 1983) and academic pursuits take on an increasingly deterministic role in their futures.

Second, it is necessary to look within particular academic domains that are gender stereotyped in assessing relations between mothers’ gender beliefs and children’s academic functioning. In other words, systematic heterogeneity of associations would be masked if studies focused on the effects of mothers’ gender-typed beliefs do not look across multiple academic domains or consider child gender as a moderator. In their meta-analysis of parents’ gender socialization in relation to children’s outcomes, Lytton and Romney (1991) point out that virtually no studies have found gender differences in the extent to which parents encourage general academic achievement across school subjects, a finding that has received interdisciplinary support in recent years (Ma et al. 2016; Pinquart 2016). Rather, parents’ specific encouragement or discouragement of stereotypically gendered academic skills matter for predicting their children’s academic achievement and beliefs in their academic abilities, and the nature of which skills are encouraged or discouraged is highly dependent on the gender of the child (Jacobs and Bleeker 2004; Tomasetto et al. 2015). Fredricks and Eccles (2002) found that parents had different expectations for girls in terms of English/language arts in contrast to mathematics and demonstrated associations between parents’ beliefs and girls’ performance in those subjects. Such research aligns with Eccles’ (1993) expectancy value model, whereby children’s motivations to succeed in specific academic domains are influenced by parents’ communications of beliefs regarding their importance.

Adolescents themselves have been shown to gender stereotype school subjects, particularly reading and language arts as being “for girls” and mathematics and science as being “for boys” (Plante et al. 2009). In their comprehensive review of the effects of parents’ and teachers’ attitudes on children’s developing gender-related math beliefs, Gunderson et al. (2012) argue that parents act as touchstones for adolescents as they develop their beliefs regarding the gender-typicality of school subjects. Overall, these studies underscore that specific academic domain and adolescents’ gender are critical to studies examining links between parents’ gender socialization and children’s academic outcomes, in that some domains are characterized more gender stereotypically than others. Specifically, whereas male adolescents are expected to outperform female adolescents in mathematics, young women are expected to be more engaged in school.

Theories of educational socialization propose that female adolescents are expected to be obedient and follow the rules, whereas male adolescents are expected to reject rules and deem putting effort into schoolwork as “feminine” (Heyder and Kessels 2013). This evidence collectively suggests that adolescents face differential academic pressures from socialization agents based on behaviors (e.g., showing effort as feminine) and domains (e.g., mathematics as masculine) that are considered appropriate for each gender. Thus, the relation between mothers’ gender beliefs and domain specific outcomes may be strengthened or weakened depending on the adolescent’s gender. Without examining adolescents’ gender as a moderator, important gender-based differences in this relation may be obscured.

Finally, most studies focused on the link between parents’ gender-typed beliefs and adolescents’ academic functioning have not accounted for adolescents’ prior academic performance. It is critical to account for students’ earlier academic performance in assessing whether mothers’ beliefs play a role in the differential academic functioning of male and female adolescents. Adjusting for prior academic achievement is particularly important in studies where students have not been randomly assigned into classrooms and may reduce the likelihood of reporting spurious findings regarding gender differences (Pennington et al. 2018).

The Current Study

In response to our review of the literature, in the current study we aimed to address three research questions. (a) Do U.S. mothers’ beliefs regarding gender-typed values and gender-typed activities vary by race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, or adolescents’ gender? (b) What is the association between mothers’ beliefs regarding gender-typed values or activities and adolescents’ math grades, reading/language arts grades, and emotional engagement in school? (c) Does gender of the adolescent moderate this association?

In accordance with the literature reviewed related to Question 1, Hypothesis 1 predicts that Latina mothers and mothers who have more recently immigrated to the United States will hold more traditional gender-typed beliefs in comparison to mothers in other ethnic groups. In relation to Question 2, because the literature reviewed supports a link between gender-typed beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes, Hypothesis 2 predicts that there will be a relationship between these variables such that more traditional beliefs will be inversely related to adolescents’ academic outcomes. However, because the literature has typically conflated maternal beliefs regarding gender-typed values and gender-typed activities, we consider it more exploratory regarding whether one or the other is more closely related to adolescents’ academic outcomes.

Finally, in relation to Question 3—due to academic stereotypes that the discipline of reading and generally showing effort in school have been feminized whereas mathematics has been masculinized—we hypothesize that adolescents’ gender will moderate the association between mothers’ gender-typed beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes. Specifically, Hypothesis 3 predicts that more traditional beliefs will be related (a) to lower reading grades and engagement in school but higher mathematics grades for male adolescents but not for female adolescents and (b) to higher reading grades and engagement in school but lower mathematics grades for young women but not for young men.

Method

Participants

The sample for the current study was drawn from a larger study of Black, Latinx, White, and Asian American students enrolled in six schools in a large U.S. urban district as they progressed through middle school. A follow-up study pursued a subset of these students and their mothers beginning in 6th grade and continuing through their high school years. The sample for the present study is composed of the 158 Black, Latinx, White, and Chinese American students and their mothers who took part in the study over the transition to high school in both 8th and 9th grade. In the current sample, 53% (n = 83) of adolescent participants were female, and adolescents and mothers were 18% (n = 29) Black, 25% (n = 39) Latinx (n = 9, 6% Puerto Rican; n = 28, 18% Dominican; n = 2, 1% Other Latinx), 22% (n = 34) Chinese American, and 35% (n = 56) White. Adolescents were 13 or 14 years-old in the spring of 8th grade and 14 or 15 years-old in the spring of 9th grade.

Families were diverse in terms of immigration history and family structure. Fifty-seven percent (n = 90) of families had either one parent and/or the adolescent born outside the United States, whereas in 43% (n = 68) of families, adolescents were 3rd generation U.S. born or more. In terms of family structure, 62% (n = 98) of adolescents lived with two parents (n = 60, 38% with only their mother). However, there were also specific within-ethnic group patterns. Seventy-two percent (n = 21) of Black mothers and adolescents and 80% (n = 45) of White mothers and adolescents were 3rd generation U.S.-born or more, whereas only 7% (n = 3) of Latinx and no Chinese mothers and adolescents were 3rd generation U.S.-born or more. In terms of family structure, 79% (n = 44) of White adolescents and 91% (n = 31) of Chinese American adolescents lived with two parents, whereas 24% (n = 7) of Black and 46% (n = 18) of Latinx adolescents lived with two parents.

Procedure and Measures

More detailed descriptions of our study procedure can be found elsewhere (see Hughes et al. 2016; Niwa et al. 2014). Thus, a brief description of procedures will be provided here. Prior to data collection, the Institutional Review Board at New York University approved our study’s compliance with ethical standards for research with human participants. Adolescents were recruited from six New York City middle schools in which school enrollment began in 6th grade and ended in 8th grade, and their mothers were also asked to participate in the study in 6th grade. The ethnic composition of schools varied: Four schools were schools in which Black, Latinx, Chinese American, and White students each constituted at least 20% of the student population; one school was predominantly Chinese American; one school was predominantly Dominican (Latinx). However, all schools had representations of Black, White, and Latinx students, and three of the six schools had representations of Chinese American students. An ethnically diverse team of trained research assistants visited all 6th grade classrooms in each school (excluding self-contained and ESL classrooms) in the spring term of two consecutive years—2005 and 2006—to recruit participants. Overall, 77% (n = 1328) of recruited adolescents returned parental consent forms, and 78% (n = 1036) of these had parental consent to participate.

Researchers asked a purposively sampled subgroup of adolescents from the larger sample in each school to request the participation of their parents. Specifically, we sought an equal number of Latinx, Chinese American, Black, and White participants in the subgroup (evenly divided by gender), and we randomly selected participants from within each ethnic and gender group. We obtained both parent and student assent prior to survey administration. Students completed surveys in school in the spring of 8th grade and came to the university laboratory to complete surveys in the spring of 9th grade; parents completed surveys in the laboratory when their children were in 9th grade. Adolescent surveys were written in English and consisted of two sections that took approximately 80 min each to complete. Parent surveys were written in English for parents who said English was their primary language and in Spanish or Chinese for parents who told researchers that was their primary language. The parent survey also consisted of two sections that took approximately 80 min each to complete. Each student received $10 or a comparable gift upon survey completion, and parents received $25 for written survey completion.

Mothers’ traditional gendered beliefs

The degree to which mothers expressed traditional gender beliefs was gauged when adolescents were in 9th grade using two measures: one which assessed gender-related values and one which assessed children’s participation in gender-typed activities. The gender values measure contained five items on marital roles and childrearing adapted from a scale by Hoffman and Kloska (1995): “A man should help in the house, but housework and child care should mainly be a woman’s job”; “It is more important to raise a son to be independent than to raise a daughter that way”; “Education is important for both sons and daughters, but it is more important for a son”; “It is okay for children to help around the house, but I would not ask a son to dust or set the table”; and “Men should make the really important decisions in the family.” Mothers were asked the degree to which they agreed with each statement on a 4-point scale from 1 (disagree a lot) to 4 (agree a lot). This gender values scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a reliability of Cronbach’s alpha .82. A scale score was constructed by taking the mean of these five items, and higher scores on this measure reflect stronger levels of support of traditional values.

The gender activities measure contained four items on children’s participation in gender-typed activities adapted from scales by Hoffman and Kloska (1995) and Egan and Perry (2001). Items were: “It is OK to give a little boy a doll to play with”; “It is OK to give a little girl toy trucks to play with”; “I think it would be OK if my son wanted to learn an activity that girls usually do”; and “I think it would be OK if my daughter wanted to learn an activity that boys usually do.” Mothers were asked the degree to which they agreed with each statement on a 4-point scale from 1 (disagree a lot) to 4 (agree a lot). The items were reverse-coded such that higher scores reflected stronger support for children’s adherence to participation in traditional gender-typed activities, thus indicating more traditional maternal gender-typed beliefs. This gender activities scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .75. A scale score was constructed by taking the mean of these four items, and higher scores on this measure reflect stronger levels of support for traditional gender-typed activities.

Emotional engagement in academics

Adolescents’ emotional engagement in academics was assessed with four items adapted from a scale by Wellborn (1991) that tapped into how emotionally engaged students feel while they are in class. The measure assessed adolescents’ positive feelings and emotions in class: “I enjoy learning new things in class”; “When we work on something in class, I feel interested”; “When I’m in class, I feel good”; and “Class is fun” on a on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (all of the time). The emotional engagement in academics scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .83. Adolescents reported on their emotional engagement in academics in 8th and 9th grades, and at each time point a scale score was constructed by taking the mean of these four items. Higher scores reflect higher levels of adolescents’ emotional engagement in academics.

Academic achievement

Achievement was approximated using two measures: adolescents’ reports of their mathematics grade on their last report card and their report of their last reading/language arts grade. Adolescents circled the number that corresponded with their grades using the following scale: 1 = 100–95, 2 = 94–90, 3 = 89–85, 4 = 84–80, 5 = 79–75, 6 = 74–70, 7 = 69–65, 8 = 55 and below. Responses were reverse coded to ensure that higher scores reflected higher reported grades. School records were obtained for approximately 75% (n = 119) of adolescents in our sample, and school records reports of adolescents’ grades were highly correlated with adolescents’ reports of their grades (r = .81 for mathematics grades and r = .80 for reading/language arts grades). Adolescents reported on their grades in 8th and 9th grades. Because school records were not available for the full sample, they were used to determine whether adolescents’ self-reported grades were accurate. Because the correlation between school records and self-reported grades was high, self-reported grades (and not school records) were used in all subsequent analyses.

Covariates

In all predictive models, we included covariates that were associated with each outcome, including immigrant generation (1 = adolescents were 3rd generation U.S.-born or more, 0 = adolescents were 1st or 2nd generation in the U.S.), family structure (1 = adolescent lives with two parents, 0 = adolescent lives with mother only), and ethnicity (dummy variables for each ethnic group with White as the reference group).

Data Analysis

We conducted a power analysis to determine minimum detectable effect sizes using G*Power 3.1.9 (Faul et al. 2007). Given that sample sizes have already been determined by the study’s data collection, we conducted sensitivity analyses given a .05 alpha level, pre-determined sample size, and at least 80% power. For Question 1 examining differences across racial/ethnic groups, given four groups of approximately 30 cases per group, our analysis indicated a minimum effect size of at least ηp2 = .38. For paired samples t-tests, given analyses within ethnic groups as small as 29, the analysis indicated a minimum effect size of at least ηp2 = .62. For Questions 2 and 3 using multiple regression analyses and SEM predicting academic outcomes, the power analysis indicated that given a sample size of 158, up to seven parameters in the equation, and an error probability of α = .05, there is power of an 80% chance of detecting a minimum effect size of at least ηp2 = .14 in the outcome measures. Power analyses indicated that although we would not be able to detect small-to-moderate effect sizes when examining within ethnic group differences, we had adequate power to detect smaller effect sizes in maternal beliefs across ethnic groups and in adolescents’ academic outcomes.

We examined differences in mothers’ gender-typed beliefs for Question 1 using ANOVA and paired sample t-test procedures, and then we examined relationships between mothers’ gendered beliefs and children’s school-related outcomes for Question 2 in a series of multiple regression equations. To examine the role of adolescents’ gender as a moderator for Question 3, we estimated simultaneous models for male and female adolescents using multiple group analysis within a structural equation framework (McArdle and Nesselroade 2002). Multiple group analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.11 (Muthen and Muthen 2009). We conducted all analyses on complete data—missing data analyses were not relevant because we sampled mothers and adolescents who completed all appropriate measures.

In investigating whether differences existed between male and female adolescents with respect to predicted path estimates, we used multi-group procedures to test whether parameters differed by gender (i.e. whether gender moderated associations). This procedure involved testing the fit of a series of nested models in which we progressively constrained parameters to equality across gender groups. For each path, we started with a model in which we freely estimated all parameters within each group. We next constrained the parameter of the model that was most similar across the two groups—for example, the association between mathematics grades in 8th grade and mathematics grades in 9th grade – to be equal across the two groups. If this constrained model did not provide a significantly worse fit to the data, as indexed by the change in the χ2 values between the two models, we concluded that the parameter did not significantly differ across the two ethnic groups. We then constrained the next most similar parameter to be equal across the two groups, using the same criteria. We repeated this procedure in testing for group differences in all parameter estimates. Using these procedures, we tested whether regression paths differed significantly across gender groups. Reflecting this process, in the text we report the fit statistics for the best fitting or final model. Parameters that are identical in the reported final model for male adolescents and model for female adolescents have been constrained to equality and were determined not to significantly differ according to Chi-square tests. Parameters that differ in the model for male adolescents in comparison to the model for female adolescents were determined to significantly differ according to Chi-square tests showing a significant decrement in fit if these parameters were constrained to be equal.

Results

We begin by presenting results in relation to Research Question 1 regarding mothers’ gender beliefs, followed by the presentation of analyses addressing Question 2 regarding the relationship between mothers’ gender beliefs and adolescents’ school-related outcomes. Finally, we present models that address Research Question 3 regarding whether the relationship between mothers’ gender beliefs and adolescents’ school-related outcomes is moderated by adolescents’ gender when adjusting for other related predictors.

Variation in Mothers’ Gendered Beliefs

In examining whether mothers’ gender-typed beliefs varied by race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, or adolescents’ gender, we first present differences across ethnic group, followed by variations within ethnic group, and finally present differences by immigrant generation and adolescents’ gender. Hypothesis 1 predicted that Latina mothers and mothers who had more recently immigrated to the United States would hold more traditional gender-typed beliefs in comparison to mothers in other ethnic groups.

We examined whether there were differences in mothers’ gender beliefs by race/ethnicity in a one-way ANOVA (see Table 1). Results showed that gender beliefs indeed differed by race/ethnicity on mothers’ gender-typed values, F(3, 154) = 33.09, p < .001, ηp2 = .39, and mothers’ views on gender-typed activities for children, F(3, 154) = 39.80, p < .001, ηp2 = .44. Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc tests suggested differences between all groups except Latina and Chinese American mothers and between Black and Latina mothers. On average, Latina and Chinese American mothers had higher levels of endorsements of traditional gender-typed values and gender-typed activities for children than White mothers (for values p < .001, d = 1.51 and for activities p < .001, d = 1.78 for Latinas; for values p = .001, d = 2.72 and for activities p < .001, d = 2.24 for Chinese American mothers). Black mothers were less likely to endorse traditional gender beliefs than Chinese American mothers (for values p < .001, d = 1.10 and for activities p = .006, d = .88)—but were more likely to endorse traditional gender beliefs than White mothers (for values p = .001, d = 1.19 and for activities p < .001, d = 1.34)—on measures of both gender-typed values and gender-typed activities.

Paired samples t-tests examined whether within group differences existed in mothers’ gender-typed values in comparison to their gender-typed beliefs regarding children’s activities. Analyses indicated that mothers in all ethnic groups were more likely to endorse traditional gender-typed activities than gender-typed values (see Table 1). On average, mothers “disagreed” or “disagreed a lot” (M = 1.73, SD = .70) with traditional statements reflecting gender values (e.g., “Men should make the really important decisions in the family”). However, mothers were divided with regard to children’s engagement in gender-typed activities: On average, mothers were in between the scale points for “disagree” and “agree” about whether their son or daughter should engage in gender-typed (and not gender-atypical) activities (M = 2.15, SD = .83). Within each ethnic group, mothers reported higher levels of endorsement for gender-typed activities for children than their levels of endorsement of traditional gender-typed values.

Finally, for Question 1 we tested whether there were differences in mothers’ gender beliefs by immigrant generation or child gender. Results showed that only immigrant generation differentiated among mothers’ endorsement of gender-typed values, F(1, 156) = 69.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .31, and mothers’ views on children’s engagement in gender-typed activities, F(1, 156) = 68.22, p < .001, ηp2 = .30. Mothers who were U.S.-born, and had adolescents who were 3rd generation American or more (values: M = 1.39, SD = .51; activities: M = 1.75, SD = .69) were less likely to endorse traditional gender-typed values or activities than mothers who were foreign-born and had adolescents who were 1st or 2nd generation American (values: M = 2.18, SD = .67; activities, M = 2.67, SD = .69).There were no differences between the gender beliefs of mothers of female adolescents versus mothers of male adolescents in terms of values, F(1, 156) = .02, p = .90, ηp2 = .00, or activities, F(1, 156) = 1.38, p = .242, ηp2 = .01, nor was the interaction significant.

Mothers’ Beliefs and Adolescents’ Outcomes

In presenting analyses addressing Research Question 2, examining associations between mothers’ gender beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes, we first present correlations among all study variables and discuss bivariate associations between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ outcomes. Hypothesis 2 predicted that more traditional maternal gender beliefs would be associated with children’s academic outcomes such that more traditional beliefs would predict lower academic performance in adolescents.

At the bivariate level, our hypothesis was supported in that mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed values was related to 8th grade mathematics grades and reading/language arts grades such that mothers who endorsed higher levels of traditional gender-typed values had adolescents with lower mathematics and reading/language arts grades in 8th grade (see Table 2). However, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed values was not related to either measure of 9th grade grades or classroom emotional engagement (at either time point). In contrast, mothers’ endorsement of children’s engagement in traditional gender-typed activities was inversely related to mathematics and reading/language arts grades at both time points (8th and 9th grade measures of these outcomes), but not classroom emotional engagement at either time point. Results suggest that, as hypothesized, mothers who more strongly endorsed traditional gender-typed values and activities were more likely to have adolescents with lower grades in mathematics and reading/language arts.

We further examined these associations in stepwise regressions adjusting for race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, family structure, and adolescents’ earlier academic ratings (see the online supplement’s Tables 1s, 2s, and 3s). Results indicated that adjusting for other predictors, in nearly all analyses mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed values did not predict mathematics grades, reading/language arts grades, or emotional engagement in school above and beyond adolescents’ earlier ratings and other covariates. However, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities for children predicted mathematics grades over and above adolescents’ earlier grades and other covariates, such that mothers who endorsed participation in traditional (and not atypical) gender-typed activities had adolescents with lower mathematics grades in 9th grade. Mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities for children did not predict adolescents’ reading/language arts grades or emotional engagement in school above and beyond adolescents’ earlier ratings and other covariates.

Gender as a Moderator

We next examined whether adolescents’ gender moderated the association between mothers’ gender-related beliefs and adolescents’ school-related outcomes for Question 3, adjusting for relevant demographic characteristics and adolescents’ 8th grade performance on the respective measure. Because we hypothesized that different relationships among variables might exist for female adolescents in comparison with male adolescents, we used multiple group analysis to account for gender as a moderator by simultaneously estimating separate predictive models for each adolescent gender group and testing whether paths differed for male adolescents in comparison to female adolescents with a series of Chi-square tests. Paths that were shown to differ between adolescents’ gender according to Chi-square tests were freely estimated, and paths where the Chi-square test indicated no significant difference were constrained to equality (and are reflected by identical estimates in each model). Hypothesis 3 predicted that mothers’ gender-typed beliefs would be associated with lower mathematics grades for female adolescents (but not male) and lower reading/language arts grades and emotional engagement in school for male adolescents (but not female).

Mathematics

Adjusting for race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, family structure, and earlier mathematics grades, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender–typed values was not related to children’s mathematics grades for either male or female adolescents (see Table 3a). Given included covariates however, the final model provided an excellent fit to the data—χ2(5) = 3.20, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 95% CI [.00, .12]—and predicted 47% of the variance in mathematics grades for female adolescents and 43% of the variance in mathematics grades for male adolescents.

In contrast, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities for children predicted mathematics grades for female but not for male adolescents (see Table 3a). Adjusting for demographic characteristics, female adolescents whose mothers less strongly endorsed their daughters engaging in stereotypically male activities had significantly lower mathematics grades in 9th grade net of their 8th grade mathematics performance. This model also provided an excellent fit to the data—χ2(5) = 1.96, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 95% CI [.00, .09]—and predicted 53% of the variance in mathematics grades for female adolescents and 41% of the variance in mathematics grades for male adolescents. This finding provides support for Hypothesis 3 that mothers’ gender-typed beliefs were associated with lower mathematics grades for female, but not for male, adolescents.

Reading/language arts

Adjusting for race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, family structure, and earlier mathematics grades, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed values was not related to adolescents’ reading/language arts grades for either male or female adolescents (see Table 3). Again however, given included covariates, the final model provided an excellent fit to the data—χ2(5) = 5.93, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 95% CI [.00, .12]—although R2 values were somewhat smaller, predicting 29% of the variance in reading/language arts grades for female adolescents and 30% of the variance in reading/language arts grades for male adolescents.

Similarly, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities for children did not predict reading/language arts grades for either male or female adolescents (see Table 3). Here the final model again provided an excellent fit to the data—χ2(5) = 6.36, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 95% CI [.00, .13]—and predicted 29% of the variance in reading/language arts grades for female adolescents and 30% of the variance in reading/language arts grades for male adolescents. This aspect of Hypothesis 3, predicting that mothers’ gender-typed beliefs would have negative associations with reading/language arts grades for male adolescents, was not supported.

Classroom emotional engagement

Adjusting for mathematics and reading/language arts grades, as well as earlier classroom emotional engagement, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed values was related to adolescents’ emotional engagement for male, but not for female, adolescents (see Table 3). Male adolescents whose mothers held more traditional views of appropriate gender roles had sons who were less emotionally engaged in classroom activities. The final model fit the data very well—χ2(3) = 2.95, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 95% CI [.00, .18]—and predicted 23% of the variance in emotional engagement for female adolescents and 31% of the variance in emotional engagement for male adolescents.

Mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities for children predicted classroom emotional engagement for both female and male adolescents, but the directionality of associations differed (see Table 3). Adjusting for grades and earlier emotional engagement, female adolescents whose mothers more strongly endorsed traditional gender-typed activities had daughters with significantly higher levels of emotional engagement in classroom activities, whereas male adolescents whose mothers more strongly endorsed traditional gender-typed activities had sons with significantly lower levels of emotional engagement in classroom activities. The final model provided an excellent fit for the data—χ2(2) = 1.80, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 95% CI [.00, .22]—and predicted 26% of the variance in emotional engagement for female adolescents and 32% of the variance in emotional engagement for male adolescents. Hypothesis 3 predicting that mothers’ gender-typed beliefs would have negative associations with emotional engagement in academics for male adolescents was supported.

Discussion

In the present study we investigated associations between U.S. mothers’ gender beliefs and their adolescents’ academic outcomes. Specifically, we sought to (a) examine whether mothers’ endorsements of traditional gender-typed activities and values differed according to race/ethnicity and immigration status, (b) assess whether mothers’ beliefs were associated with adolescents’ academic outcomes, and (c) determine whether adolescents’ gender moderated these associations. Focusing on our results from the fully specified model addressing Research Question 3 (rather than simply bivariate correlations), we found that mothers’ endorsements of gender-typed values predicted lower engagement in school among male adolescents. Mother’s endorsements of gender-typed activities was associated with higher engagement in school and lower math grades for female adolescents, but lower emotional engagement in school for male adolescents. Importantly, we found that mothers’ endorsements of both gender-typed values and activities were not associated with reading/language arts grades, despite literature suggesting a strongly held cultural stereotype associating female adolescents and femininity with reading and writing based skills.

We provide needed evidence concerning mothers’ gender-typed beliefs across racial/ethnic groups, and we partially confirmed past literature regarding predictors of difference among mothers’ beliefs. We found clear evidence that mothers’ gender beliefs were related to adolescents’ academic outcomes broadly, but the type of outcome and whether gender beliefs was measured through gender-typed activities or values mattered. When adjusting for demographic characteristics, there were no associations between mothers’ beliefs in terms of traditional gender-typed values and adolescents’ mathematics grades, reading/language arts grades or emotional engagement in school. However, when we examined these associations in the context of the interaction between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ gender, we found that mothers with more traditional beliefs about gender-typed values were more likely to have sons with low levels of emotional engagement in school. Mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities for children was associated with lower mathematics grades overall, but when we look at the interaction between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ gender, analyses revealed that mothers’ beliefs regarding gender-typed activities were associated with lower mathematics grades for female adolescents, but not for male adolescents, as well as higher emotional engagement in school for female adolescents, but lower emotional engagement for male adolescents.

Our findings regarding racial and ethnic differences in U.S. mothers’ gender beliefs are noteworthy. Latina and Chinese mothers held more traditional gender beliefs than both Black and White mothers across both gender-typed activities and values, replicating Raffaelli and Ontai (2004) findings on highly traditional gender beliefs among Latina mothers. Our data contradict past literature suggesting Black women are likely to reject traditional gender beliefs (Cole and Zucker 2007; Kane 2000; Littlefield 2008). Instead, we found that these mothers had a relatively high level of endorsement of gender-typed activities and moderate endorsements of gender-typed values. Surprisingly, White women expressed the least endorsement of traditional gender beliefs of any group across both measures.

We also demonstrated that immigrant mothers (those not born in the U.S. whose children are 1st or 2nd generation American) held more traditional gender beliefs than mothers who were born in the United States. However, it is difficult to disentangle immigrant generation from race/ethnicity considering that the bulk of Latina and Chinese mothers were born outside the United States and the bulk of Black and White mothers were U.S.-born. Although future studies must disentangle race/ethnicity and immigration, our results underscore the importance of accessing multiple dimensions of gender beliefs, which can illuminate nuances in group differences that may have been previously masked.

On average, all mothers were fairly low on gender-typed beliefs across groups (between about 1.5 and 2.5 on a 1 to 4 scale) but held less traditional beliefs in terms of gender-typed values than gender-typed activities. Mothers’ generally stronger endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities than values may highlight the difference between “talking the talk” and “walking the walk” in terms of gender beliefs. Although many mothers hold progressive values about gender, these ideas may not always filter through to beliefs about actual gender atypicality among their children’s activities. This finding adds to evidence in the field suggesting mothers’ gender beliefs are not monolithic, but more likely subtle and multidimensional (Bigler 1997; Carlson and Knoester 2011; Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002). For example, few mothers were willing to endorse strongly traditional gender-typed value statements like “A man should help in the house, but housework and childcare should mainly be a woman’s job.” At the same time, many mothers agreed that they did not want their sons to play with dolls or their daughters to play with trucks (i.e., to adhere to gender-typed expectations for activities). Although all mothers may be moving toward egalitarianism in terms of the roles sons and daughters and men and women might play, many mothers still endorse traditionalism in terms of the activities they see as appropriate for their children, and our findings link these traditional beliefs to negative academic outcomes in adolescents.

Our third research question examined whether these associations differed by gender. Research in gender-typed academic expectations suggests that there are differential outcomes by gender and by subject, such that daughters are expected to be more engaged in school and do better than sons generally, whereas sons are expected to do better in mathematics and sciences than daughters (Heyder and Kessels 2013; Mickelson 1989; Ruble et al. 2006; Tenenbaum and Leaper 2003). The current study underscores the power of these expectations when traditional gender beliefs are held by mothers. Specifically, adjusting for other factors related to adolescents’ academic outcomes, mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender-typed activities was negatively associated with mathematics grades and positively associated with emotional engagement in school for their daughters. In other words, the more strongly mothers endorsed gender-typed beliefs regarding activities, the more their daughters recapitulated gendered expectations in terms of academics—receiving lower mathematics (but not reading/language arts) grades but expressing higher levels of emotional engagement in school.

Our finding that mothers’ endorsements of gender-typed activities was not associated with increases in female adolescents’ reading/language arts grades was unexpected. Two plausible interpretations of this findings are that first, the cultural stereotype associating femininity with language-based capacities may be diminishing over time, and there is some evidence to support this speculation (Evans et al. 2011; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2004). Second, although the feminine-language stereotype may still be culturally embedded, the stereotype that women and girls are deficient in math may be more persistent, strong, and detectable within our data.

Our finding that mothers’ endorsement of traditional gender beliefs was not associated with their sons’ mathematics grades but was associated with lower levels of male adolescents’ emotional engagement in school was similarly unexpected. This finding aligns with evidence on the feminization of effort and engagement in school (Heyder and Kessels 2013), but contradicts the notion that mothers who endorse more stereotypic beliefs would have sons who perform higher in subjects associated with maleness. Considering this finding and our finding that mothers’ gender-typed activity endorsements and their daughters’ language grades were not associated, it is possible that mothers’ gender beliefs have stronger predictive power when the primary stereotype held by the larger culture is negative. According to this possible interpretation, mothers’ may be more likely to socialize stereotypes about academic domains or capacities that are contrary to their adolescents’ gender. Thus, mothers’ may more actively socialize the negative stereotype that their adolescent daughters are “bad at math” and their adolescent sons “don’t care” about school rather than the positive stereotypes that male adolescents are “good at math” and female adolescents are skilled in reading and writing.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution, however, in that they do not reflect causal links between mothers’ gender-typed beliefs and their daughters’ and sons’ academic outcomes. Yet it is important to consider that, given that predictive models include robust adjustments for racial/ethnic background, family structure, and prior academic performance, the link between mothers’ gender-typed beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes merits attention. Our findings seem to align with Eccles’ (1993) expectancy value model in which parents’ beliefs predict parents’ behaviors, which in turn affect adolescents’ motivation, thereby shaping adolescents’ behaviors and outcomes. According to this model, mothers who believe that their children should engage in gender-typed and not gender-atypical activities will actually provide activities for their children that correspond to these beliefs (e.g., giving boys, and not girls, toys that aid in the development of the visual-spatial skills that provide a foundation for mathematics learning: Martin and Dinella 2002). Furthermore, these experiences lead to greater or lesser motivation to develop the skills promoted or precluded by their mothers’ behaviors.

During adolescence, most youth spend time in numerous contexts, and they are likely influenced by the beliefs and behaviors of siblings, teachers, peers, and others in addition to mothers and fathers. These more proximal socialization agents are also only part of adolescents’ larger cultural socialization through media and the broader sociocultural ideologies of their cultures and contexts. In terms of connections between gendered expectations in the macro-culture and adolescents’ microsystems, it may be that mothers are not directly communicating to sons that lower levels of engagement in school are appropriate or to daughters that mathematics is likely to be difficult. Rather the fact that mothers communicate expectations for gender-typed expectations in less controversial domains (e.g., dress or social behavior) may reinforce adolescents’ perceptions of other more pernicious gendered expectations (e.g., that their daughters are indeed more likely to struggle in mathematics).

Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to consider our findings in light of a few limitations. First, as we discussed, although we adjust for other factors that have been shown to be linked with adolescents’ outcomes, the associations provide better evidence than bivariate relations, but are nonetheless correlational in nature. It is possible that rather than mothers’ beliefs driving adolescents’ outcomes, that adolescents’ academic outcomes play a role in mothers’ beliefs or that a third variable not included here is linked to both mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes. Second, although we include mothers and children from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds, our sample size is small and not representative of Latinx-American, ChineseAmerican, Black, and White mothers and adolescents more generally. The overwhelming paucity of gender socialization studies that include families from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds necessitates that future studies continue to expand knowledge in this area among diverse groups (Else-Quest and Hyde 2016).

Although our study is unique in its ability to begin to capture this area of research among ethnically diverse families, we only collected data on mothers’ beliefs. Fathers’ influence on child development is critical and should not be ignored (Cabrera et al. 2018), making the study of the associations between fathers’ gender beliefs and adolescents’ academic outcomes an important area of future research. Finally, although we detail the social learning mechanisms proposed by past scholars, our data are unable to pinpoint the mechanism or mechanisms that connect mothers’ gender-typed beliefs to adolescents’ academic outcomes. Future studies should include multiple mediators that model the pathways through which mothers’ beliefs are associated with adolescents’ outcomes (Simpkins et al. 2012).

Practice Implications

Our findings suggest that mothers’ gender beliefs may be a potential target for interventions designed to promote gender equality in the school setting. Although many mothers in our study actively rejected gender beliefs in terms of gender-typed values, mothers’ endorsements of gender-typed activities may be a particularly rich area of intervention for counselors, teachers, and researchers to develop. It may be the case that even if mothers are aware of traditional gender expectations, they may not be as acutely aware of how these beliefs can be communicated implicitly through their approval or disapproval of their adolescent’s gender typical or atypical choice in activities. Finally, mothers (or both parents, although our study does not speak to the involvement of fathers’ gender socialization) may not be familiar with gender stereotypes about the feminization of engagement in school, whereas stereotypes about girls and math are more widely known. Our work underscores the link between gender beliefs and unequal, gendered expectations for adolescents’ engagement in school, making it a particular imperative for interventionists committed to awareness raising. Ultimately, intervention work may be able to disrupt the pathways through which mothers’ gender beliefs are conveyed to their adolescents and then manifested in their academic engagement and performance.

Conclusions

Scholars examining the role of gender in development have identified the need for studies that connect conceptions of gender in the macro-culture to the socialization of gender occurring in children’s microsystems (Leaper 2002; Best and Puzio 2019). Despite this identified need, few studies have been able to access the pathways through which gendered expectations in American culture at large (e.g., “girls aren’t good at math”) filter through to adolescents’ actual functioning and performance. Mothers’ socialization of gender is thought to be one of these important pathways, although empirical evidence demonstrating this link among adolescents is scarce.

The current study contributes to the literature on gender socialization by providing an initial look into differences in mothers’ beliefs across racial/ethnic groups. It also underscores that despite variations, mothers are similar in their endorsement of egalitarian beliefs in terms of gender-typed values. However, there are gendered expectations in terms of children’s activities, and we show that these expectations have implications for adolescents across racial/ethnic groups. We demonstrate that mothers’ gendered beliefs are indeed multifaceted and complex, and traditional gender expectations appear to have mostly negative associations with adolescents’ academic functioning depending on the interplay of type of belief, academic domain, and adolescents’ gender. Gender beliefs can only be understood within a context of the gendered expectations that exist within the macro-culture. From this perspective it becomes clear that traditional gender beliefs hurt both sons and daughters, but in different ways.

References

Abrams, J. A., Javier, S. J., Maxwell, M. L., Belgrave, F. Z., & Nguyen, A. B. (2016). Distant but relative: Similarities and differences in gender role beliefs among African American and Vietnamese American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000038.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-98423-000.

Best, D. L., & Puzio, A. (2019). Gender and culture. In D. Matsumoto (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 235–291). New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190679743.003.0009.

Bian, L., Leslie, S. J., & Cimpian, A. (2017). Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science, 355(6323), 389–391. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah6524.

Bigler, R. S. (1997). Conceptual and methodological issues in the measurement of children’s sex typing. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00100.x.

Bronstein, P. (2006). The family environment: Where gender role socialization begins. In J. Worell & C. D. Goodheart (Eds.), Handbook of girls’ and women’s psychological health: Gender and well-being across the lifespan (pp. 262–271). New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170621807.

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106(4), 676–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676.

Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12275.

Carlson, D. L., & Knoester, C. (2011). Family structure and the intergenerational transmission of gender ideology. Journal of Family Issues, 32(6), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10396662.

Chatterji, M. (2006). Reading achievement gaps, correlates, and moderators of early reading achievement: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS) kindergarten to first grade sample. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.489.

Cole, E. R., & Zucker, A. N. (2007). Black and white women's perspectives femininity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.1.

Crouter, A. C., Whiteman, S. D., McHale, S. M., & Osgood, D. W. (2007). Development of gender attitude traditionality across middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 78(3), 911–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01040.x.

Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12(3), 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00347.

Denner, J., & Dunbar, N. (2004). Negotiating femininity: Power and strategies of Mexican American girls. Sex Roles, 50(5–6), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000018887.04206.d0.

DiPrete, T. A., & Jennings, J. L. (2012). Social and behavioral skills and the gender gap in early educational achievement. Social Science Research, 41(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.09.001.

Eccles, J. S. (1993). School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self-perceptions, and activity choices. In R. Dienstbier (Series Ed.) & J. E. Jacobs (Vol. Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (Vol. 40, pp.145–208). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-98639-004

Egan, S. K., & Perry, D. G. (2001). Gender identity: A multidimensional analysis with implications for psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 37(4), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.451.

Else-Quest, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316629797.

Endendijk, J. J., Groeneveld, M. G., van Berkel, S. R., Hallers-Haalboom, E. T., Mesman, J., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2013). Gender stereotypes in the family context: Mothers, fathers, and siblings. Sex Roles, 68(9–10), 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0265-4.

Endendijk, J. J., Groeneveld, M. G., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Mesman, J. (2016). Gender-differentiated parenting revisited: Meta-analysis reveals very few differences in parental control of boys and girls. PLoS One, 11(7), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159193.

Entwisle, D. R., Alexander, K. L., & Olson, L. S. (2007). Early schooling: The handicap of being poor and male. Sociology of Education, 80(2), 114–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070708000202.

Epstein, M., & Ward, L. M. (2011). Exploring parent-adolescent communication about gender: Results from adolescent and emerging adult samples. Sex Roles, 65(1–2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9975-7.

Evans, A. B., Copping, K. E., Rowley, S. J., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (2011). Academic self-concept in black adolescents: Do race and gender stereotypes matter? Self and Identity, 10(2), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2010.485358.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191 https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-11814-002.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2018). America’s children in brief: Key national indicators of well-being 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office https://www.childstats.gov/pdf/ac2018/ac_18.pdf.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Children's competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male-sex-typed domains. Developmental Psychology, 38(4), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.4.519.

Freeman, N. K. (2007). Preschoolers’ perceptions of gender appropriate toys and their parents’ beliefs about genderized behaviors: Miscommunication, mixed messages, or hidden truths. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-006-0123-x.

Galambos, N. L., Almeida, D. M., & Petersen, A. C. (1990). Masculinity, femininity, and sex role attitudes in early adolescence: Exploring gender intensification. Child Development, 61, 1905–1914. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb03574.x.

Gaskins, S. (2015). Childhood practices across cultures: Play and household work. In L. Jenson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human development and culture (pp. 185–197). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199948550.013.12.

Gerson, K. (2009). The unfinished revolution: Coming of age in a new era of gender, work, and family. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2014.994262.

Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., & Cohen, L. (1996). Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 32(6), 999–1007. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.999.

Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). The role of parents and teachers in the development of gender-related math attitudes. Sex Roles, 66(3–4), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9996-2.

Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (1999). Financial strain, parenting behaviors, and adolescents’ achievement: Testing model equivalence between African American and European American single- and two-parent families. Child Development, 70(6), 1464–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00106.

Halpern, H. P., & Perry-Jenkins, M. (2016). Parents’ gender ideology and gendered behavior as predictors of children’s gender-role attitudes: A longitudinal exploration. Sex Roles, 74(11–12), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0539-0.

Halpern, D. F., Straight, C. A., & Stephenson, C. L. (2011). Beliefs about cognitive gender differences: Accurate for direction, underestimated for size. Sex Roles, 64(5–6), 336–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9891-2.

Heyder, A., & Kessels, U. (2013). Is school feminine? Implicit gender stereotyping of school as a predictor of academic achievement. Sex Roles, 69(11/12), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0309-9.

Heyder, A., Kessels, U., & Steinmayr, R. (2017). Explaining academic-track boys’ underachievement in language grades: Not a lack of aptitude but students’ motivational beliefs and parents’ perceptions? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12145.

Hill, J. P., & Lynch, M. E. (1983). The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In J. Brooks-Gunn & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives (pp. 201–228). New York: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0354-9_10.

Hoffman, L. W., & Kloska, D. D. (1995). Parents’ gender-based attitudes toward marital roles and child rearing: Development and validation of new measures. Sex Roles, 32(5/6), 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01544598.

Hughes, D., Del Toro, J., Harding, J. F., Way, N., & Rarick, J. R. (2016). Trajectories of discrimination across adolescence: Associations with academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. Child Development, 87(5), 1337–1351. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12591.

Hyde, J. S., Lindberg, S. M., Linn, M. C., Ellis, A. B., & Williams, C. C. (2008). Gender similarities characterize math performance. Science, 321(5888), 494–495. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1160364.

Jacklin, C. N., DiPietro, J. A., & Maccoby, E. E. (1984). Sex-typing behavior and sex-typing pressure in child/parent interaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 13(5), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541427.

Jacobs, J., & Bleeker, M. (2004). Girls’ and boys’ developing interests in math and science: Do parents matter? In H. Bouchey & C. Winston (Eds.), New directions in child and adolescent development (pp. 5–21). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.113.

Jones, M. K., Buque, M., & Miville, M. L. (2018). African American gender roles: A content analysis of empirical research from 1981 to 2017. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(5), 450–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798418783561.

Kagan, J. (1964). The child’s sex role classification of school objects. Child Development, 35(4), 1051–1056. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126852.

Kane, E. W. (2000). Racial and ethnic variations in gender-related attitudes. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.419.

Kessels, U., Heyder, A., Latsch, M., & Hannover, B. (2014). How gender differences in academic engagement relate to students’ gender identity. Educational Research, 56(2), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2014.898916.

Leaper, C. (2002). Parenting girls and boys. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting (Vol. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 127-152). Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum Associates. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-02629-007

Leslie, S. J., Cimpian, A., Meyer, M., & Freeland, E. (2015). Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines. Science, 347(6219), 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261375.

Littlefield, M. (2008). Gender role identity and stress in African American women. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 8, 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v08n04_06.

Lytton, H., & Romney, D. M. (1991). Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.267.

Ma, X., Shen, J., Krenn, H. Y., Hu, S., & Yuan, J. (2016). A meta-analysis of the relationship between learning outcomes and parental involvement during early childhood education and early elementary education. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 771–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9351-1.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing apart and coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-07493-00.

Martin, C. L. (1993). Theories of sex typing: Moving toward multiple perspectives. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1993.tb00389.x.

Martin, C. L., & Dinella, L. M. (2002). Children’s gender cognitions, the social environment, and sex differences in cognitive domains. In A. McGillicuddy-De Lisi & R. De Lisi (Eds.), Biology, society, and behavior: The development of sex differences in cognition (pp. 207–239). Westport, CT: Ablex https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-05754-008.

Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. N. (2010). Patterns of gender development. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100511.