Abstract

Although the problem of sexual harassment can be approached from a variety of perspectives, the present research focused on the role played by individuals’ perceptions, specifically those that may differ between men and women. We examined whether perceived sexual harassment would vary depending on observers’ gender, on gender of the harasser and of the victim, and on whether and what type of sexual harassment definition was provided to observers. In doing so, we attempted to update and clarify inconsistent results from prior studies. Results from 413 young adult U.S. MTurk participants responding to an online survey revealed fairly large effects for participants’ gender, such that women perceived a wider range of situations as sexual harassment than did men. In addition, the dyad of a man harassing a woman was construed as more definitely involving sexual harassment than other dyads. Surprisingly, these gender differences were smaller for situations judged as comprising sexual harassment to a lesser extent (i.e., those involving derogatory attitudes and nonsexual physical contact). Results are discussed in relation to prior findings and their legal implications, especially as they relate to a psychological assumption of the so-called “reasonable woman” standard used in U.S. courts, that women perceive sexual harassment to a greater degree than men. The results are also relevant for those wishing to curtail harassment within organizations and for those counseling victims of sexual harassment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What the American Psychological Association (APA) noted in 1993 about sexual harassment—that it is a problem with a long past and a short history—seems true even in more contemporary times. As a testament to its winning Time’s person of the year award in 2017, the #MeToo movement has made it clear that sexual harassment has not disappeared with the passage of time and perhaps more progressive social attitudes (Zacharek et al. 2017). For example, a large and recent nationally representative survey found that 81% of U.S. women over the age 18 reported having experienced some form of sexual harassment (Chatterjee 2018). In 2017, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) received 6696 claims of workplace sexual harassment (U.S. EEOC 2018). Perhaps in part because of greater willingness to report offenses, in the following year sexual harassment charges increased 13.6%, federal sexual harassment lawsuits increased more than 50%, reasonable cause findings increased more than 23%, and the EEOC recovered nearly $70 million for sexual harassment victims, a gain of more than 22% from 2017. Although causes and preventive remedies to sexual harassment exist on many levels, the current research focused on the role played by individuals’ perceptions, specifically differing perceptions between men and women.

Perceptions of Sexual Harassment

Excluding quid pro quo cases of sexual coercion and others involving obviously bad intent, to some degree the problem of sexual harassment results from the problem of differing perceptions of sexual harassment. That is, in some undetermined proportion of sexual harassment cases, the offender is operating with different criteria than the victim about the offensiveness of various behaviors. In the end, what is relatively innocuous to one individual is not perceived that way by another. Inhabiting a social universe in which different actors have different thresholds for what constitutes sexual harassment inevitably leads to disputes and negative emotions experienced by victims and in some cases harassers who may genuinely believe they have done nothing inappropriate. Beliefs about what qualifies as sexual harassment matter at every stage of a harassing incident, which as the prior statistics denote, in some cases evolve into formal complaints and even civil lawsuits.

In the first place, actors face decisions about whether to engage in a certain behavior, targets in turn face decisions about how to interpret that behavior, confidants make decisions about how to advise the target, supervisors within an organization make decisions about how a potential complaint is handled, and judges and juries make decisions ultimately about how to adjudicate the matter. Each of these decisions involves a series of judgments by different individuals, each informed by subjective perceptions of what constitutes sexual harassment and the degree to which the behavior in question meets this personal standard. Of chief concern here is the possibility that personal standards, in addition to being influenced by individuating factors unique to each person, may also be shaped by one’s gender. In particular, we adopt a relatively novel approach in examining how perceptions of sexual harassment may be shaped by perceivers’ gender, harassers’ gender, and targets’ gender.

Definitions and Legal Standards

To combat the relativistic sense that sexual harassment should be what each person interprets it to be, and to clearly delineate broad classes of inappropriate behavior for both potential offenders and those asked to judge offenders, interested parties have developed formal definitions of sexual harassment. According to the EEOC (1980), sexual harassment in the United States is defined as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature when…such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with…or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment” (emphasis added). This standard definition, however, does not eradicate the problem of perceptions; many social science researchers have found it vague and difficult to operationalize in part because it focuses on the subjective experience of hostility and offensiveness, not on objective behaviors (Williams 2018). It is decidedly silent on whose perspective should be adopted to evaluate whether conduct unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.

U.S. courts have typically asked jurors to consider how a “reasonable person” in similar circumstances would respond (Harris v. Forklift Systems Inc., 1993). Under this decree, if the challenged conduct would not substantially affect the work environment of a reasonable person, no violation should be found. This standard aims to avoid the potential for parties to claim they suffered harassment when most individuals would not find such instances offensive if they themselves were the subjects of such treatment. The problem of perception looms, however: Who is this reasonable person, and who is qualified to make this evaluation of what someone else thinks? Is it possible to render this judgment without considering one’s own assessment of the situation?

The reasonable person standard is also decidedly noncommittal on whether the offended party is a reasonable man, woman, or (n)either. Although this standard has long been accepted by most U.S. courts as the correct measure for evaluating allegedly culpable conduct, most notably in negligence cases, a number of courts have recently challenged its applicability in cases of sexual harassment. Instead, some courts have interpreted the circumstances surrounding a case from the perspective of a “reasonable woman” (Ellison v. Brady, 1991). In adopting a reasonable woman standard, the courts have assumed that the reasonable person standard does not account for the divergence between most women’s views of appropriate sexual conduct and the views of men. Specifically, in Ellison v. Brady (1991), the court noted that “conduct that many men find unobjectionable may offend many women.” Thus, in maintaining the reasonable person standard and excluding a woman’s perspective, the court assessed that it ran the risk of “reinforcing the prevailing level of discrimination” (Ellison v. Brady, 1991).

There are two assumptions underlying the reasonable woman standard: one psychological and one normative. The first premise, necessary for the second to have relevance, is that men and women differ in their judgments of what specific behaviors constitute sexual harassment. The second premise of the reasonable woman standard contains the value assessment that viewing a wider range of behaviors as sexual harassment is desirable and more correct, meriting the court’s endorsement. Although the normative question is beyond the scope of the present research, the first question forms the essence of it. Centrally, we examine the foundational assumption of the reasonable woman standard, that relative to men, women would rate higher on a continuous scale the degree they estimate sexual harassment to have occurred in various behaviors.

There have been dozens of published studies examining perceptions of sexual harassment, and many analyze differences based on gender of the perceiver. Blumenthal (1998) conducted a meta-analysis of 83 independent effect sizes over 34,350 participants and 111 studies. In another meta-analysis that shortly followed, Rotundo, Nguyen, and Sackett (2001) identified 145 articles, from which they selected 62 studies using 33,164 participants as meeting their criteria for inclusion. The central effect in these meta-analyses was that women were more likely than men to define a broader range of behaviors as more harassing. Because the effect sizes were not large though, ranging from d = .30 (Rotundo et al. 2001) to d = .35 (Blumenthal 1998), the results are typically interpreted as only lending minimal support for the assumptions underlying the reasonable woman standard—at least the psychological one that many women are offended by conduct many men would find inoffensive.

However, predictions by Rotundo et al. (2001) that gender differences would be larger for more ambiguous or less extreme behaviors was partially supported. Specifically, gender differences were larger for behaviors that involved hostile work environment than the more blatant cases of quid pro quo harassment (i.e., sexual coercion), for which there was relatively greater agreement. Within the hostile work environment criteria, more ambiguous and less extreme categories such as dating pressure and derogatory attitudes led to greater gender disagreement than the more blatant category of sexual propositions. Contrary to predictions, gender differences were not significantly larger for the more ambiguous cases of harassment between those of equal status. Blumenthal (1998) found that more recent studies relative to older ones and those using a written scenario compared to those not revealed larger gender differences in perceived sexual harassment.

Beyond the Man Harasser-Woman Victim Dyad

The studies examined in these meta-analyses almost universally involve one type of harasser-target dyad: a man as harasser and woman as victim (hereafter referred to as “man-woman harassment,” with the harasser’s gender listed first and the victim’s gender second). That sexual harassment can apply to other dyads (i.e., man-man, woman-man, woman-woman) is not even mentioned by either Blumenthal (1998) or Rotundo et al. (2001). This bias is understandable given that most instances of sexual harassment involve man-woman harassment and that this gender composition involves the greatest imbalance of power, but it leaves a large lacuna in understanding how much sexual harassment individuals perceive to have occurred in other scenarios. That is, there is almost no evidence examining the psychological assumptions of the reasonable woman standard outside the typical situation of a man harassing a woman.

Although the law has not always recognized these alternative types of sexual harassment, including same-sex harassment (see Carlucci and Golom 2016; Foote and Goodman-Delahunty 2005; Garcia v. Elf Atochem North America 1994), a recent, nationally representative survey found that 43% of men reported experiencing sexual harassment (Chatterjee 2018), and the percentage of charges filed by men increased 15.3% from 1997 to 2011 (Quick & McFayden, 2017). Fully 21% of men and 3% of women employed by the federal government have reported experiencing sexual harassment from same-gender harassers (U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board 1981, 1995), although these figures greatly underestimate incident rates because as many as 94% of victims do not report being harassed, in part because the majority of those who do experience retaliation upon reporting their harassment (EEOC 2016).

To date, we are aware of four studies that have examined perceived sexual harassment in harasser-target dyads outside of the traditional man-woman scenario. Katz et al. (1996) presented participants with hypothetical interactions featuring man-woman or woman-man harassment. Overall, men perceived more harassment when the perpetrator was a man and the victim a woman than vice-versa, but women perceived similar amounts of harassment in both conditions. On the other hand, Marks and Nelson (1993) found that male professors shown potentially sexual harassing a female student in a 90-s videotape were judged as acting no more inappropriately than a female professor shown potentially sexually harassing a male student.

Bitton and Shaul (2013) varied both the gender of the harasser and gender of target in a full factorial design and asked participants to estimate whether sexual harassment occurred in a series of vignettes. Women perceived two cases of behavior as sexual harassment more than men: woman-man and man-man. Complicating the interpretations though, this study suffered from several methodological issues: (a) participants were exposed to all types of dyads, which could have made them more sensitive to gender composition differences; (b) perceptions of sexual harassment were measured less sensitively in the form of dichotomous yes/no judgments for each vignette, potentially losing important distinctions perceived among the vignettes; and (c) the statistical analysis did not report tests of the full-fledged interactive model, instead only reporting post-hoc comparisons; therefore the reader cannot ascertain whether there were main effects for harasser gender, target gender, or an interaction, which ultimately makes it hard to compare with results from other studies. Incidentally, it does not appear that ratings for man-woman scenarios exceeded ratings for other scenarios.

Finally, Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) were the first to present participants with scenarios capturing the four combinations of harasser gender and victim gender. Across all participants, they found highest ratings of sexual harassment for man-woman harassment (and tests of an interaction were not provided). For women, this effect was slightly nuanced because the cross-gender combinations were given significantly higher sexual harassment ratings than either of the same-gender combinations.

In summary, these studies examining perceived sexual harassment in a range of dyads have produced highly inconsistent results. In Runtz and O’Donnell (2003), man-woman harassment was perceived as constituting the most harassment. In Katz et al. (1996), this outcome only held for participants who were men. In Marks and Nelson (1993), there was no difference between man-woman and woman-man harassment. Finally, in Bitton and Shaul (2013), it does not appear that these conditions differed, but statistical tests were not reported. Only two of the studies fully crossed gender of harasser and gender of victim, and neither reported tests of the statistical interaction.

The Impact of Sexual Harassment Definitions

Given these limitations, inconsistent findings, and that most of these studies are over 15 years old, it is warranted to re-examine how perceptions of sexual harassment vary across the gender of the harasser and gender of the victim. This approach helps evaluate the psychological assumptions of the reasonable woman standard across a fuller range of situations in which sexual harassment can occur. The present research also examined the impact that reading a definition of sexual harassment would have on subsequent judgments. There is some controversy in the best way to define sexual harassment (Quick and McFadyen 2017), which could be problematic because the way that sexual harassment is defined may affect the extent to which it is perceived.

Many organizations expose employees to their explicit sexual harassment policies in an attempt to curtail inappropriate behavior, but the impact of these practices is unclear. Tinkler et al. (2007), for example, found that exposure to a sexual harassment policy caused individuals to more greatly endorse male superiority on an implicit level. Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) varied whether participants were first given a definition of sexual harassment before rating vignettes containing questionable behavior. Judgments of men were sensitive to this manipulation, such that perceived sexual harassment was lower when given an EEOC-like definition of sexual harassment prior to rating the scenarios. To account for this unexpected finding, the authors speculated that the definition may have caused men to “reassess the ambiguous behaviors in light of their tendency to view the behaviors as normative gender-role prescribed behaviors” (p. 987).

This strikes us as one possible explanation among several. First, the definition manipulation was confounded with whether participants were asked to recount any personal experiences of being sexually harassed. Some men may have had difficulty imagining personal harassment, causing them to underestimate the prevalence and seriousness of sexual harassment when judging the scenarios. Alternatively, reading the definition may have in some men produced psychological reactance, an unpleasant arousal to rules or regulations that threaten specific behavioral freedoms (Brehm 1966). When rating subsequent vignettes, such men may have been motivated to underestimate sexual harassment because they felt that they were being lectured or preached to about appropriate behavior. A definition of sexual harassment may also implicitly suggest to men that they are superior to women, an explanation implied by the findings of Tinkler et al. (2007). Finally, on a cognitive level, the definition provided to men may have been more restrictive than their intuitive definition of sexual harassment, and thus, those without the definition were more inclusive in their judgments. In short, although the findings of Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) are noteworthy, the process by which the effects occurred is unclear because of the confounding variable and because participants were exposed to only one type of definition.

The Current Study

To identify the most appropriate explanation for why exposure to a definition lowered perceived sexual harassment among men in Runtz and O’Donnell (2003), the present research varied the definition of sexual harassment provided to participants before they judged the degree to which various behaviors constituted sexual harassment. Beyond a no definition control group, we contrasted the effects of receiving a more concrete definition with some criteria for what constitutes sexual harassment (i.e., the EEOC’s legal definition) with the effects of receiving an abstract definition lacking a clear description of problematic behaviors (i.e., an early, influential sociopsychological sexual harassment definition by legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon 1979). To the extent that the Runtz and O’Donnell’s (2003) findings reflect a confound, there should be no differences in perceived sexual harassment among the three definitional conditions. To the extent that a definition of sexual harassment triggers motivational pressures within men or implicitly suggests female inferiority, the two definition conditions should both result in a lower extent of perceived sexual harassment than the no definition control. To the extent that a prior definition cognitively changes men’s understanding of what constitutes sexual harassment, one may expect the more concrete definition (i.e., the EEOC) to result in a greater extent of perceived sexual harassment than the more abstract definition (i.e., MacKinnon 1979) and the control condition because a concrete definition facilitates greater awareness and understanding of how a given scenario meets the definition.

In addition to assessing the effects of sexual harassment definition, in the present research we sought to gain a contemporary understanding of the extent to which individuals perceive sexual harassment occurring across different harasser gender and victim gender dyads. Men and women were exposed to a number of vignettes, all representing instances of sexual harassment drawn from the literature and likely varying in their perceived severity. The harasser’s gender and victim’s gender were manipulated. We expected to replicate long-standing observed gender differences in perceived sexual harassment, with a main effect of women perceiving behaviors as reflecting a greater degree of sexual harassment than men (Hypothesis 1).

Our study also examined several other research questions without making clear a priori predictions. One question concerned whether gender differences would be larger for behavior that is judged sexual harassment to a lesser degree (i.e., a participant gender x sexual harassment category interaction). There is some reason to believe that smaller gender differences should emerge on behaviors judged as sexual harassment to a greater degree. Rotundo et al. (2001), for example, found smaller gender effects for sexual coercion and sexual propositions, typically seen as severe categories of sexual harassment. But they also found small effects for the relatively less severe category of non-sexual physical contact. Part of the difficulty in specifying which categories should produce the greatest gender disparity in perceptions is knowing in advance how severe various behaviors will be perceived. Both within psychological research and the law, the great majority of stimulus-based severity distinctions appear to be relatively arbitrary and sometimes potentially erroneous (see Fitzgerald et al. 1997). One way to arrange behaviors is to employ the three dimensions identified by Fitzgerald et al. (1997)—gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion (from least to most severe)—although these clusters were identified on the basis of self-reported frequency and not perceived severity, so it is unclear how helpful this distinction is in generating predictions.

We also raised a question about whether men and women would judge man-woman harassment as most definitely constituting sexual harassment relative to the other cases. There is mixed evidence from the literature about this possibility, but with exceptions, this gender dynamic is most emphasized as it relates to sexual harassment. We were unsure if such an effect would reveal itself as either two separate main effects of harasser gender and perceiver gender or a harasser gender x perceiver gender interaction, and whether this would vary for men and women as participants, because existing research has not fully reported such effects.

Method

Participants

Before data collection commenced, the present study was approved by the Bellarmine University Institutional Review Board for compliance with standards for the ethical treatment of human participants. Participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk-www.mturk.com/mturk/), an online labor market where requesters post jobs and workers choose which jobs to do for pay. A brief recruitment notice for a study on social perceptions was posted on MTurk along with a link to the survey monkey website hosting the survey. To control for age and nationality, we recruited U.S. participants between the ages of 18 and 25 years-old who were paid $.20 for their participation. The decision to restrict participants’ age to a relatively young adult sample was based on several factors. First, it facilitated comparisons with outcomes from the four prior studies assessing perceptions beyond the man harasser-woman victim context. It also answered a call by Quick and McFadyen (2017) for more sexual harassment research involving millennials. Finally, the decision was pragmatic, because the study design already included five independent variables, and it seemed excessive to manipulate a sixth variable in participants’ age.

Before beginning the survey, participants read an informed consent giving an overview of the study procedures including provisions for anonymity and their rights as participants. Upon completion of the study, each participant received a brief written explanation of the purpose of the study. This included the name and contact telephone number for the researcher. The survey was accessible from April 3, 2018 to April 7, 2018. During this period, 446 individuals responded to the survey. Thirty-three were excluded for inadequately answering the manipulation check (see below), leaving the final sample at 413. Of the total sample, 55% were women. The mean age of participants was 22.90 (SD = 1.76, range = 18–25).

Design

The study consisted of a 2 (Participant Gender: man, woman) × 2 (Harasser Gender: man, woman) × 2 (Victim Gender: man, woman) × 3 (Definition: EEOC, MacKinnon, none) between-subjects design, with Sexual Harassment Category (derogatory attitudes and nonsexual contact, objectification and dating pressure, sexual propositions, contact, and coercion—see subsequent preliminary analysis) as a within-subjects factor.

Procedure

Based on previous research, we created nine original brief vignettes depicting a workplace interaction, and we asked participants to decide the degree to which each situation involved sexual harassment. Participants were randomly assigned to one of 12 treatment conditions that varied (a) the gender of a hypothetical work supervisor (woman/man), (b) the gender of a subordinate employee (woman/man), and (c) the sexual harassment definition made available to participants (EEOC, MacKinnon, none). Each condition comprised approximately equal numbers of men and women.

In the EEOC definition condition, participants were asked to consider the following definition of sexual harassment when making judgments:

Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature when (a) submission to such conduct is made either explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual's employment, or (b) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as a basis for employment decisions affecting such individual, or (c) such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual's work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

In the MacKinnon definition condition, participants were asked to consider the following definition when making judgments: “Sexual harassment refers to the unwanted imposition of sexual requirements in the context of a relationship of unequal power.” In the no definition control condition, participants were not asked to consider any formal definition of sexual harassment when making judgments. For participants in the first two conditions, the definition was provided for 20 s before each vignette to help ensure attention to it.

Measures

Manipulation check

Those participants in the EEOC and Mackinnon definition conditions were asked to write the criteria on which they had been asked to make their judgments. Two judges coded these open-ended statements as either indicating that the participant had attended to the definition or had not, based on the presence of key terms and replicating the general meaning (interrater agreement reached 87%, and the disputed cases were resolved). Results from anyone not able to produce a fairly liberal approximation of the definition (n = 33) were excluded from the analysis; 67% (n = 22) of these individuals were in one of the EEOC conditions.

Sexual harassment

To facilitate comparisons with Rotundo et al. (2001), perceived sexual harassment was assessed in a continuous way by asking participants to rate the degree to which the behavior in each vignette reflected sexual harassment on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely is not sexual harassment) to 7 (definitely is sexual harassment), with a midpoint of 4 (unsure). The vignettes depicted nine categories of sexual harassment. Seven of the categories were derived from the category scheme created by Rotundo et al., developed after reviewing existing empirical research, legal cases, and discussions of legal precedent (for a thorough description of the process, see Rotundo et al. 2001). These behaviors included impersonal derogatory attitudes (negative attitudes directed toward women or men in general); personal derogatory attitudes (negative attitudes aimed specifically at the target person); unwanted dating pressure (repeated requests for a date or propositions of a nonsexual nature); sexual propositions (propositions that were explicitly sexual in nature); physical sexual contact (social-sexual behaviors in which the harasser actually made physical contact with the target); physical nonsexual contact (behaviors in which the harasser made nonsexual contact with the target); and sexual coercion (in which the harasser levied force or coercion against the target). From our own examination of prior research, we created two additional categories (i.e., non-verbal objectification—including staring, leering and other unspoken behaviors sexualizing the target and verbal objectification—including sexually inappropriate comments about the target’s physical appearance) to enhance the content validity of the construct. In short, our goal was to use accepted examples of sexual harassment from the literature and systematically examine how definitely each would be construed as sexual harassment.

Most of the categories constitute a hostile work environment whereas the last category (i.e., sexual coercion) involves quid-pro-quo sexual harassment. In terms of Fitzgerald et al.’s (1997) influential three-dimensional model of sexual harassment (i.e., gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion), derogatory attitudes are examples of gender harassment; verbal and nonverbal objectification, dating pressure, sexual propositions, and physical sexual contact represent unwanted sexual attention; and sexual coercion represents itself, with physical nonsexual contact not being represented in the model.

We present the exact vignettes in the following, using the man as harasser, woman as victim dyad as the default. (See the online supplement for all the other vignettes.) These names were reversed when the woman was depicted as the harasser and the man as the victim. Nine additional women’s names (i.e., Jennifer, Charlotte, Jessica, Rebecca, Kim, Elizabeth, Heather, Veronica, and Melissa) substituted for the men’s names when women were depicted as both harasser and victim, and similarly, nine men’s names (i.e., Jared, Lucas, David, John, Daniel, Matthew, Noah, Jacob, and Nolan) substituted for the women’s names when men were depicted as harasser and victim. The names were chosen because they are associated with one gender and help control for perceptions of ethnicity: We only used names that were rated as being “Caucasian” by greater than 90% of participants in pre-screening before the current study. Gender pronouns were adjusted appropriately depending on the gender composition of the dyad.

For a few of the vignettes, the actual content was changed when the victim was a man to make it more consistent with gender roles and stereotypes. Specifically, verbal objectification was changed to focus on muscles, as opposed to curves; derogatory attitudes (impersonal) was changed to an inability to fix automobiles as opposed to not cleaning; and derogatory attitudes (personal) focused on a lack of physical strength as opposed to not doing the laundry. We attempted to make the length and structure of the vignettes as similar as possible. For the unwanted dating pressure vignette only, the victim’s reaction (i.e., resistance and discomfort) was revealed to emphasize that the request had occurred repeatedly. The order of the vignettes was randomized for each participant, but here they are listed from those perceived as sexual harassment to a lesser extent to those perceived as sexual harassment to a greater extent, according to the study results.

Derogatory attitudes—impersonal, e.g., “Walter, the supervisor, is seated with a group of male coworkers for lunch when Barbara walks by. She overhears one of the men making a joke about how his wife has not been cleaning ‘like she should’ after which the other males chime in talking about the failures of their own wives to fulfill their ‘responsibilities as women.’”

Derogatory attitudes—personal, e.g., “Donna’s supervisor Joshua noticed she is wearing the same shirt for the third day in a row. He then makes the comment that she should be able to do laundry since she’s a woman, and that is her civil duty.”

Physical nonsexual contact, e.g., “Albert, Hannah’s supervisor, approaches Hannah’s desk and tells her he has an announcement to make. He tells the office that Hannah has been promoted. He then gives her a congratulatory hug.”

Verbal objectification, e.g., “George, the supervisor at the local refrigeration company, calls Mary, the receptionist into his office. They are casually discussing an invoice when George says to Mary, ‘That shirt fits you very nicely, it really accentuates your curves.’”

Nonverbal objectification, e.g., “Linda, the receptionist at the local refrigeration company got on the elevator leaving work one afternoon. As the elevator became crowded, she had to move to the back. She then noticed that her boss, Jeffrey was staring at her. Jeffrey seemed to get closer to Linda, even as people left the elevator. Then, Linda noticed Jeffrey was eyeing her body up and down and grinning.”

Dating pressure, e.g., “Sarah and her supervisor Jack were leaving a meeting when Jack, for the fourth time this week, blatantly asked Sarah to join him for drinks after work, ‘just the two of them.’ Sarah restated again that she was uninterested in the offer made by Jack. Jack challenged her response by reminding her that he is ‘such a nice guy and just wants to get to know her better.’”

Sexual propositions, e.g., “Bradley, Samantha’s supervisor, approaches Samantha’s desk and requests that she join him in his bed tonight, instead of being alone. He suggests that they will have an intimate time together, getting to know each other better on a personal and physical level.”

Physical sexual contact, e.g., “Rachel, the receptionist, is at the copy machine when her boss, Nathan, approaches her from behind. Nathan reached for the copies in the machine and ‘accidentally’ grabbed Rachel’s buttocks.”

Sexual coercion, e.g., “Eric, Kayla’s supervisor, calls her into his office, asking her to shut the door behind her. Once she sits down, Eric tells Kayla that if she is looking to be considered for a raise, she needs to get on her knees and beg for it. Kayla is confused, and Eric continues on to explain that if she wants the raise, she must perform the sexual acts ‘she knows’ he is alluding to.”

Results

Preliminary Analysis

To further investigate the number of constructs and structure of the sexual harassment categories, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis using a principal components analysis. Initial eigen values indicated a three-factor solution, explaining 30%, 20%, and 11% of the variance respectively. For the final stage, we conducted a principal components factor analysis of the nine items, using varimax and oblimin rotations, with the three factors explaining 60% of the variance. A varimax rotation provided the best defined factor structure. All items in this analysis had primary loadings over .50. None of the items had a cross loading over .30. The factor loading matrix for this final solution is presented in Table 1.

Internal consistency for each of the scales was examined using Cronbach’s alpha. The alphas were moderate: .75 for derogatory attitudes and nonsexual contact (3 items), .78 for objectification and dating pressure (3 items), and .65 for sexual propositions, contact, and coercion (3 items). Composite scores were created for each of the three factors, with higher scores indicating a greater perceived degree that sexual harassment had occurred. The three subscales differed in their ratings of the extent that sexual harassment occurred across the vignettes, F(2,377) = 1132.35, p < .001, ηp2 = .86. Derogatory attitudes and nonsexual contact (M = 2.70, SD = 1.06) were rated as harassment to a lesser extent than were objectification and dating pressure (M = 4.45, SD = 1.24), F(1,401) = 675.20, p < .001, ηp2 = .63, and sexual propositions, contact, and coercion (M = 6.21, SD = .86), F(1,401) = 2523.93, p < .001, ηp2 = 86. Perceptions in these latter two categories were also statistically different from one another, F(1,401) = 769.52, p < .001, ηp2 = .66.

Hypothesis 1: Gender Differences

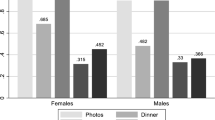

Table 2 presents means and standard deviations for treatment conditions, collapsed across sexual harassment definition, because this factor did not yield significant effects. Overall, there was a significant main effect for participant gender, F(1,378) = 72.51, p < .001, ηp2 = .16. In strong support of the first hypothesis and the psychological assumption of the reasonable woman standard, women (M = 4.69, SD = .72) perceived a greater degree of harassment than men (M = 4.15, SD = .67) across the nine behavioral categories.

Moderation by Sexual Harassment Category

The main effect of participant gender differed depending on sexual harassment category, F(2,377) = 4.07, p = .018, ηp2 = .02. Although the main effect for participant gender was significant within each sexual harassment category, the effect was weakest for the vignettes depicting derogatory attitudes and non-sexual contact. That is, gender differences for those vignettes depicting the lower rated derogatory attitudes and non-sexual contact, F(1,400) = 17.00, p < .001, ηp2 = .04, were smaller than differences in perceptions between women and men for vignettes depicting objectification and dating pressure, F(1,411) = 39.01, p < .001, ηp2 = .09, and depicting sexual propositions, contact, and coercion F(1,400) = 32.12, p < .001, ηp2 = .07 (see Table 2). This contradicts speculation that gender differences in perceptions would be larger for behavior that was perceived as sexual harassment to a lesser extent. To the contrary, behaviors judged as sexual harassment to a greater extent produced larger perceptual differences between men and women. (The online supplement includes this analysis conducted according to Fitzgerald et al.’s 1997, classification scheme rather than the factor structure reported here.)

Harasser-Victim Genders

Regarding the second research question, man-woman harassment (M = 4.92, SD = .67) was perceived as constituting sexual harassment to a greater degree than any other dyad: man-man (M = 4.30, SD = .66), t(198) = 6.57, p < .001, d = .93; woman-woman (M = 4.30, SD = .68), t(201) = 6.52, p < .001, d = .92; and woman-man (M = 4.35, SD = .80), t(181) = 5.22, p < .001, d = .77. Rather than two simple main effects, this outcome was driven by a significant harasser gender x victim gender interaction, F(1,378) = 24.73, p < .001, ηp2 = .06. When the victim was a woman, men as harassers were perceived as more sexual harassing than were women as harassers, F(1,201) = 42.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .18. When the victim was a man though, there was no difference in perceived sexual harassment between men as harassers and women as harassers, F(1,196) = .27, p = .602, ηp2 = .01 (see Table 2).

The two-way interaction was qualified by a participant gender x harasser gender x victim gender three-way interaction, F(1,378) = 12.97, p = .001, ηp2 = .06 (see Table 2). For men, the harasser gender x victim gender interaction was not significant, F(1,171) = 1.41, p = .237, ηp2 = .01. There were, however, main effects for harasser gender, F(1,171) = 10.20, p = .002, ηp2 = .05, and for victim gender, F(1,171) = 22.13, p < .001, ηp2 = .12. For men, man-woman harassment was perceived as constituting sexual harassment to a greater degree than any other dyad: man-man, t(80) = 4.01, p < .001, d = .89; woman-woman, t(94) = 3.12, p = .003, d = .66; and woman-man, t(81) = 5.14, p < .001, d = 1.14 (see Table 2a).

For women, however, the harasser gender x victim gender interaction was significant, F(1,222) = 38.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .15. Post hoc tests showed that when the victim was a woman, women perceived men as harassers as more sexually harassing than women as harassers, F(1,107) = 37.08, p < .001, ηp2 = .26 (see Table 2b). When the victim was a man though, the opposite pattern occurred, with women perceiving women as harassers as more sexually harassing than men as harassers, F(1,115) = 6.84, p = .010, ηp2 = .06. In short, as we suspected, behaviors in which men harassed women were judged as constituting sexual harassment to the greatest extent for both men and women. Interestingly, when men were victims, women perceived a greater extent of sexual harassment when women, not men, were the harassers.

Discussion

Consistent with expectations, women were overall more likely to judge the vignettes as involving sexual harassment to a greater extent than were men. Although the meta-analytic reviews (Blumenthal 1998; Rotundo et al. 2001) identified relatively small effects of responder gender on perceived sexual harassment, here the size of the gender difference was large (ηp2 = .16). The magnitude of gender differences varied according to the type of sexual harassment studied, but unlike prior literature (e.g., Rotundo et al. 2001), gender differences were not larger for behavior perceived as sexual harassment to a lesser extent. In fact, there was evidence that perceptions held by women and men were most discrepant when the offending behavior was more definitely construed as sexual harassment. Caution, however, should be exercised in comparing the present findings to prior meta-analytic work based exclusively on instances of man-woman dyads. The inclusion of a range of dyads may have accentuated overall gender differences.

The results suggest a three-tier structure of perceived sexual harassment severity: derogatory attitudes and physical nonsexual contact (interpreted as sexual harassment to a low degree); objectification and dating pressure (perceived as sexual harassment to a moderate degree perhaps because of the unwanted sexual attention these behaviors place on the victim); and sexual propositions (physical sexual contact and quid-pro-quo coercion, all intensifying the victim’s discomfort and perceived as sexual harassment to the greatest degree). This typology does not adhere strictly to the factor structure arising from the mostly widely used instrument to assess sexual harassment because in the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (Fitzgerald et al. 1995), sexual propositions and physical sexual contact are examples of unwanted sexual attention rather than coercion. An important difference is that in the current study participants rated the extent various behaviors reflected sexual harassment from an observer’s perspective rather than reporting on the frequency they personally experienced the behaviors. Future research is needed to clarify the issue of seriousness and how much the extent of perceived sexual harassment is based on the objective characteristics of certain stimuli and how much on individual differences in target characteristics and experiences.

One of the main purposes of the present research was to examine how individuals would perceive sexual harassment when occurring in a full combination of offender and victim genders. Although prior research has been limited on this topic and produced inconsistent results, the current findings reveal that the man-woman dyad elicits the strongest perception that sexual harassment has occurred, a result previously attained by Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) but contradicted by others.

Despite the consensus related to man-woman sexual harassment, there were important gender differences in perceived sexual harassment based on offender and victim genders. Men were not as sensitive to differences in various dyads as were women; for men, perceived sexual harassment was additive only. Women victims and men harassers elicited the strongest sexual harassment judgments, but the effect of harasser gender did not depend on victim gender. For women, however, this interaction was significant. When the victim was a woman, women perceived men harassers as more sexually harassing than women harassers, but when the victim was a man, the opposite pattern occurred. In this case, women harassers were perceived as more sexually harassing than men harassers. A similar finding was attained by Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) for women who first read an objective definition of sexual harassment before making judgments. This result stands out, then, as a unique instance when women harassers are perceived as more sexually harassing then men harassers. Whether these opposing outcomes for women can be explained by the same process is unclear. They may both represent, for example, a relative unwillingness in women to recognize same-gender sexual harassment or a heightened sensitivity to other-gender sexual harassment. Instead, women may be more sensitive to man-woman harassment for reasons rooted in history, power imbalances, and the deleterious impact of such harassment (see Berdahl et al. 1996; Cortina and Berdahl 2008) and less sensitive to man-man sexual harassment because it does not personally involve them.

Overall, relative to comparable research, the present results provide strong support for the psychological assumption behind the reasonable woman standard that women perceive sexual harassment to a greater degree than men. Some of this increased effect size may be attributable to the current study featuring several characteristics that Blumenthal (1998) found produced larger gender differences in perceived sexual harassment. Such features include having a status differential between harasser and victim, using relatively younger participants, and using written incidents/scenarios as opposed to legal cases or checklists.

Another possibility is that perhaps #MeToo or other cultural changes have heightened differences in the way that women and men perceive sexual harassment. Although purely speculative, women may be more sensitive than men to the contemporary movement confronting sexual harassment. This need not be a foregone conclusion; to the extent that men have been educated by #MeToo, one may have expected the gender effect to be smaller than prior studies or even non-existent. The present results harken back to Blumenthal (1998), who noted that despite increased awareness of sexual harassment implied in the more recent studies he analyzed, these studies found larger gender differences in perceived sexual harassment.

The impact of #MeToo may potentially be seen in the null findings for the impact of reading a sexual harassment definition before making judgments. Although Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) found that men’s estimates of sexual harassment were lower when first given a definition of sexual harassment, the present study found no such effects. Reading what defines sexual harassment did not seem to trigger any discernable motives or cognitive processes in our participants. One explanation is that #MeToo may have transformed the societal definition of what is acceptable behavior, and this new norm may differ somewhat or give context for the legal definition or interpretation of the legal definition. It is possible that the null findings regarding definitions of sexual harassment are most applicable to younger populations, who may rely on their intuitive understandings more generally and specifically for the case of sexual harassment, which has likely been more socialized into their consciousness than for older generations. That is, younger participants today, especially in light of #MeToo, may have been exposed to stories of sexual harassment to such a degree that they do not feel bound to follow a prescribed definition and instead evaluate potential harassment from their own intuitive understanding.

This speculation clearly needs further testing in samples involving comparisons with older populations and would benefit from explicitly measuring the degree to which participants are aware of, identify with, or participate in the #MeToo movement. Younger participants may also be more prone to rebuff the jargon and legalese contained in the definitions used in the present study, although this would seemingly have also been true in Runtz and O’Donnell (2003). Finally, there is the possibility that this is not a generational effect and that definitions of sexual harassment simply do not affect judgments of it. In this account, apparent male sensitivity to a definition in Runtz and O’Donnell (2003) was only caused by it being confounded with participants recalling their own experiences of being sexually harassed.

The #MeToo movement may also be relevant in explaining why, for both genders, the man-woman dyad was perceived as the typical case of sexual harassment. To the extent that #MeToo has primarily highlighted and emphasized examples in which women have been victimized by male harassers, this case may be even more strongly ingrained as the prototype for sexual harassment. Although clearly speculative, this view has more support than the alternative that the current movement would make individuals more aware of and sensitive to sexual harassment generally without consideration of the gender composition of the dyad. Irrespective of #MeToo, the man-woman dyad may also be construed as sexually harassing to the greatest extent in part because of the way that men as victims are perceived. Research on perceptions of sexual violence more generally has demonstrated, for example, that there is less empathy for and greater blame placed upon men as victims of sexual violence (e.g., rape) (Burt and DeMello 2002; Levy and Adam 2018; White and Robinson Kurpius 2002). Alternatively, rather than reflecting a bias, rating man-woman situations as harassment to the greatest extent may reflect reasons rooted in history and power imbalances that make such instances of sexual harassment victimization generally worse for women than men (Berdahl et al. 1996; Cortina and Berdahl 2008).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

That stated, there are other limitations to the current study which warrant further investigation. One of the largest constraints concerns the nature of the vignettes themselves. As alluded to earlier, the scenarios on which participants made sexual harassment judgments were very limited in detail. Unlike realistic incidents which may require lengthy explanations in court documents, the encounters described for current participants were merely a few sentences. In most circumstances, the questionable behavior occurred only once as a single incident lacking the chronic nature of some real-world sexual harassment. In a recent meta-analysis, Sojo et al. (2016) found that high frequency yet low intensity sexual harassment experiences were as detrimental as low frequency/high intensity forms of sexual harassment. By compressing the frequency of harassing actions, we may have, therefore, forced participants to only focus on the intensity of the problematic behavior.

Furthermore, our scenarios were non-interactive, in that the response of the victim was generally unknown and the response of the offender to that response unknown as well. The current vignettes were essentially templates containing the minimal amount of information to express the type of potentially offensive behavior. As such, we limited participants’ abilities to be biased processers of information (see Baumeister 1998, for a review), preventing them from critically scrutinizing and discovering flaws in disagreeable information, interpreting the meaning of ambiguous information to be favorable to their viewpoint, selectively searching through memory in a biased way, etc. It is difficult to know, therefore, whether the effects we found would be exacerbated in real-world examples with more information available to individuals or whether such information might overwhelm the current manipulations.

Additionally, participants were not directly involved in these incidents, merely reading them as second-hand observers without direct knowledge or acquaintanceship of the actors involved. Participants were only asked to make a global judgment about the extent to which sexual harassment occurred. Future studies may wish to explore subtle differences that could emerge from asking participants about their attitudes about the involved individuals, such as assigning responsibility for various behaviors. The setting itself was also intentionally restricted to include only a workplace situation, although sexual harassment is obviously possible in other settings such as a classroom or team environment. Finally, even though sexual harassment occurred within a workplace setting, participants were not actual employees and, thus, variables such as organizational and job gender context (see Fitzgerald et al. 1997) were excluded from influencing perceptions.

Practice Implications

These limitations aside, the present findings have potentially important implications for administrators, therapists, policymakers, courts, and researchers moving forward. Most directly, the results help establish that in contemporary times, men and women differ in their views of how much various behaviors constitute sexual harassment. This divergence of judgments may help explain some occurrences of sexual harassment in the workplace, particularly when a man behaves in a manner that offends another party without intending to do so. Administrators need to address this sexual harassment perception gap to curtail harassing incidents on the part of men but also to ensure that men as policymakers within the organization are not adjudicating harassment complaints based on their narrower understanding of sexual harassment. Definitions based on objective behaviors may serve decisionmakers, provided that they do not simply rely on their own intuitive understandings. Therapists need to realize that women clients who have been sexually harassed may encounter greater resistance from men in their lives who may be more apt to underestimate the severity of what has transpired.

Legally, this finding poses a bit of a conundrum. On the one hand, it supports the psychological assumptions underlying the implementation of a standard that relies on the viewpoint of a reasonable woman as opposed to a reasonable person. That is, women perceive a situation as involving man-woman sexual harassment to a greater degree than do men, and ultimately, it is up to the courts to decide whether a more inclusive or less inclusive position has more merit. However, the present results complicate this calculus and suggest that which standard should be adopted may not be a straightforward question with a consistent answer. For in cases involving an alleged male harasser and male victim, a reasonable woman standard would pose a higher threshold for the victim than in cases involving a female harasser and male victim.

What standard is adopted may depend not only on whose viewpoint is considered but also on the unique gender combination of harasser and victim. If one holds the view that the severity of sexual harassment is determined by the behavior itself, regardless of the gender composition of the harasser and victim, and that moral and legal judgments about it should be made independent of the involved genders, then the present results are troubling. The results suggest that victims in other dyads may be less willing to come forward because they do not believe their treatment to be as severe or fear that others will not. In this view, organizations need to train employees (as harassers and victims) and administrators making judgments about the merits of allegations that harassment need not follow the man-woman prototype, courts need to be aware of this bias when adjudicating harassment claims, and therapists need to be sensitive that victims outside the prototypical man-woman dyad may feel less support and possess even more ambivalence about the incident.

That said, it is possible to view our results as reflecting reality and to argue that changing the dyadic composition away from man-woman fundamentally changes the degree of harassment, given the history and power differences between men and women as well as the deleterious impact of such harassment on women (see Berdahl et al. 1996; Cortina and Berdahl 2008). Finally, our results suggest that gender harassment, as a form of harassment, is judged as sexual harassment to a far lesser extent than other forms of harassment. Although this likely reflects objective reality to some degree, these situations nonetheless constitute sexual harassment, yet are far less likely to be perceived that way. The same issues as we noted here, therefore, need to be considered by administrators, courts, and therapists in handling and counseling victims of gender harassment. The behavior is less likely to be curtailed, given legal protection, and met with empathy from others because of its consideration as outside the circle of legitimate sexual harassment.

Conclusion

Sexual harassment remains a persistent social problem, with formal complaints increasing in the wake of #MeToo. Beyond actions inspired by maliciousness and bad intent, sexual harassment may on occasions arise from differing perceptions about what constitutes sexual harassment. One source of difference in perceptions is gender (but not seemingly the definition of sexual harassment made available) because the present findings indicate that men perceive various behaviors as constituting sexual harassment to a lesser extent than do women. Both genders perceive situations with a man harassing a woman as sexual harassment to the greatest extent. Whether this is problematic may ultimately be a question for further psychological, philosophical, and legal inquiry, but it certainly does not adhere to a normative standard of judging behavior similarly irrespective of the gender of the actors. Stakeholders should note that men and women are not equivalent in the way they perceive harassment between other dyads outside the prototypical man-woman situation, potentially raising problems for those wishing to curtail sexual harassment, those wishing to counsel and assist victims, and those required to adjudicate complaints.

References

American Psychological Association. (1993). In the Supreme Court of the United States: Teresa Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc.: Brief for amicus curiae American Psychological Association in support of neither party. Washington, DC.

Baumeister, R. F. (1998). The self. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 680–740). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Berdahl, J. L., Magley, V. J., & Waldo, C. R. (1996). The sexual harassment of men?: Exploring the concept with theory and data. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(4), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00320.x.

Bitton, M. S., & Shaul, D. B. (2013). Perceptions and attitudes to sexual harassment: An examination of sex differences and the sex composition of the harasser-target dyad. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(10), 2136–2145. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12166.

Blumenthal, J. A. (1998). The reasonable woman standard: A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Law and Human Behavior, 22(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025724721559.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press.

Burt, D. L., & DeMello, L. R. (2002). Attributions of rape blame as a function of victim gender and sexuality, and perceived similarity to the victim. Journal of Homosexuality, 43, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v43n02_03.

Carlucci, M. E., & Golom, F. D. (2016). Juror perceptions of female-female sexual harassment: Do sexual orientation and type of harassment matter? Journal of Aggression. Conflict and Peace Research, 8(4), 238–246.https://doi.org/10.1108/jacpr-01-2016-0210.

Chatterjee, R. (2018). A new survey finds 81% of women have experienced sexual harassment. National Public Radio. Retrieved on October 18, 2018 from https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/02/21/587671849/a-new-survey-finds-eighty-percent-of-women-have-experienced-sexual-harassment.

Cortina, L. M., & Berdahl, J. L. (2008). Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. In J. Barling & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 469–497). Thousand Oaks: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200448.n26.

Ellison v Brady, 924 F.2d 872, 879 (9th Cir. 1991).

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (1980). Guidelines on discrimination because of sex (Sect. 1604. 11). Federal Register, 45(74), 676–74,677.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace. Retrieved from: https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/task_force/harassment/.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., & Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: a test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(4), 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.82.4.578.

Foote, W. E., & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2005). Evaluating sexual harassment: Psychological, social, and legal considerations in forensic examinations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10827-000.

Garcia v. Elf Atochem North America, 28 F.3d 446 (5th Cir. 1994), 18. (1994).

Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17 (1993).

Katz, R. C., Hannon, R., & Whitten, L. (1996). Effects of gender and situation on the perception of sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 34(1–2), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01544794.

Levy, I., & Adam, K. M. (2018). Online commenting about a victim of female-on-male rape: The case of Shia LaBeouf’s sexual victimization. Sex Roles, 79(9–10), 578–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0893-9.

MacKinnon, C. (1979). The sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination (No. 19). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Marks, M. A., & Nelson, E. S. (1993). Sexual harassment on campus: Effects of professor gender on perception of sexually harassing behaviors. Sex Roles, 28(3–4), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00299281.

Quick, J. C., & McFadyen, M. A. (2017). Sexual harassment: Have we made any progress? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000054.

Rotundo, M., Nguyen, D., & Sackett, P. R. (2001). A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 914–922. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.5.914.

Runtz, M. G., & O’Donnell, C. W. (2003). Students’ perceptions of sexual harassment: Is it harassment only if the offender is a man and the victim is a woman? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(5), 963–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01934.x.

Sojo, V. E., Wood, R. E., & Genat, A. E. (2016). Harmful workplace experiences and women’s occupational well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(1), 10–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346.

Tinkler, J. E., Li, Y. E., & Mollborn, S. (2007). Can legal interventions change beliefs? The effect of exposure to sexual harassment policy on men’s gender beliefs. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(4), 480–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250707000413.

U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission. (2018). Charges alleging sex-based harassment (charges filed with EEOC). Retrieved on July 5, 2018 from https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/sexual_harassment_new.cfm

U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. (1981). Sexual harassment in the federal workplace: Is it a problem? Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. (1995). Sexual harassment in the federal workplace: Trends, progress, and continuing challenges. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

White, B. H., & Robinson Kurpius, S. E. (2002). Effects of victim sex and sexual orientation on perceptions of rape. Sex Roles, 46, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019617920155.

Williams, C. L. (2018). Sexual Harassment in organizations: A critique of current research and policy. In R. Refinetti (Ed.), Sexual Harassment and Sexual Consent (pp. 20–43). New York: Routledge.

Zacharek, S., Dockterman, E., & Edwards, H.S. (2017, December). The silence breakers. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/time-person-of-the-year-2017-silence-breakers/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

I have read and am in compliance with the guidelines of the 6th edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, including the provisions about duplicate publications. No data from this research are being submitted or published elsewhere as a separate manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 35 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rothgerber, H., Kaufling, K., Incorvati, C. et al. Is a Reasonable Woman Different from a Reasonable Person? Gender Differences in Perceived Sexual Harassment. Sex Roles 84, 208–220 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01156-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01156-8