Abstract

Despite decades of research on women’s human rights and empowerment across several academic disciplines, inequities between women and men persist at alarming rates across the globe. The current study employs an in-depth exploration of how programs intended for empowering purposes impact individual women’s lives, focusing on the transformation promoted at multiple ecological levels. More specifically, the present study assesses how women involved in a feminist organization in rural Nicaragua were affected by their participation in the organization. Via analysis of qualitative interviews with 14 women, we identify aspects of the organization most associated with actualizing transformative change and assess how involvement in the organization affected women’s sense of self and lived experience. Specifically, we identify and explicate two themes: (a) moving forward, which details aspects of the organization that facilitated positive changes for women, and (b) feminist autoconocimiento, which involved developing an understanding of oneself as capable of offering valuable contributions to their homes and communities. Findings have implications for promoting empowering contexts for women, with a focus on ensuring that desired empowering change is occurring for the women involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite the development of an abundant literature on women’s human rights and empowerment across several disciplines, gendered inequities persist at alarming rates across the globe (Cornwall and Eade 2011; United Nations 2016). Implicated in the disconnect between research, practice, and transformative change for women is the watering down of empowerment discourses (Batliwala 2007). Where the notion of women’s empowerment was once reserved for radical efforts to transform power relations between women and men in the promotion of gender equity, empowerment discourses have become mainstream to the extent that they are utilized by organizations such as the World Bank to promote wealth accumulation, all the while neglecting root sources of inequity (Cornwall 2016). In a global context of increasing awareness of gender inequities, matched with the proliferation of neoliberal tactics for change (Bay-Cheng 2015; Dutt and Kohfeldt 2018; Harvey 2007), there is a growing need for researchers to identify mechanisms that create substantive transformation in women’s lived experience. Consequently, in the present paper we examine how empowering processes are facilitated for and by women, as well as are linked to actualized change in women’s lived realities and sense of self.

Although psychology is relatively underrepresented among the academic disciplines focused on identifying pathways to promote women’s empowerment globally, theoretical and methodological tools developed within psychology can serve as an important asset in studying processes of women’s empowerment (Grabe 2010, 2012). Psychologists have contributed to empowerment theory by emphasizing that empowerment is a psychosocial processes through which marginalized individuals gain mastery and control over their environment and gain greater ability to make decisions that affect their lives (Cattaneo and Chapman 2010; Grabe 2012; Rappaport 1987; Zimmerman 1995). Additionally, psychologists have critiqued the individualistic focus of empowerment and the neglect of values such as concern for the collective (Dutt 2018; Kurtiş et al. 2016; Riger 1993). Noting these critiques, in depth exploration of how programs intended for empowering purposes influence women’s lives in multiple ways can yield deeper insight into processes and outcomes associated with change. More specifically, through a critical exploration of individual women’s lives we can explore how social and political realities, in addition to the structures and components of an empowering intervention, are filtered through and expressed in individual women’s experiences in their homes, communities, and own self-perceptions. The focus of the current study is to assess how women involved in a feminist organization in rural Nicaragua were affected by their participation in an empowering setting. We specifically focus on identifying aspects of the organization most associated with actualizing transformative change and on assessing how involvement in the organization influenced women’s sense of self, with empowering implications.

Xochilt Acalt and Empowering Settings

Previous research in community psychology suggests that involvement in empowering settings can facilitate positive outcomes for the individuals involved (Dutt 2018; Maton 2008; Maton and Salem 1995). Empowering settings are organized spaces that are developed with the intention of supporting marginalized community members to gain greater control over their lives, resources, and environment (Maton and Salem 1995). Although previous research outlines components of empowering settings (Maton 2008; Maton and Salem 1995), as well as illustrates positive outcomes associated with involvement including increased well-being and involvement in activism (Dutt 2018; Watts et al. 2003), less is known about the actual process of transformation that individuals experience while involved in these spaces.

In the current study we explore how a specific feminist organization, Centro de Mujeres Xochilt Acalt [The Xochilt Acalt Women’s Center], directly influences women’s interpretations of their experiences and sense of self. In many ways Xochilt Acalt serves as an empowering setting for women in Malpaisillo, Nicaragua (Dutt 2018). The organization was founded with the goal of improving women’s health and well-being. It began as a mobile health clinic in 1992, but has expanded over the past 25 years with the aim of cultivating more empowered realities for women in multiple domestic and societal contexts. Expansion has involved developing various educational and justice-oriented workshops designed to increase women’s knowledge about their rights and the availability of community and legal resources. Additional created programs center on skill development, including programs in which women get training on landownership, raising livestock, and farming techniques that promote environmental sustainability.

The overarching design of the organization was developed in the tradition of Paulo Freire’s (1970) theories of social change, and thus focuses on increasing women’s knowledge about rights and their ability to contribute to social change through a consciousness-raising process. Through the different workshops and programs offered by the organization, women communally discuss and reflect upon topics including gender roles and identity, sources and consequences of poverty, violence against women, gender inequality, and issues that arise within the community (Montenegro and Cuadra 2004). Additionally, information about opportunities for women to participate in political decision-making, reproductive rights, economic rights, and traditional academic topics such as literacy are shared and discussed. In this way, Xochilt Acalt seeks to promote reflection and action related to addressing inequities and sources of hardship in multiple contexts that shape women’s lives.

The approach to promoting women’s empowerment in multiple contexts is consistent with growing calls for more complex and interconnected models of empowerment in academic literatures. For example, theoretical models of empowerment described in the literature include multiple levels: the macro, including the broad sociopolitical context; the meso, reflecting the ways in which empowerment is supported or deterred in relational contexts; and the micro, referring to a person’s own beliefs and actions (Huis et al. 2017). Despite that scholars in the area of women’s empowerment have described a multidimensional model in which multiple levels of society play integrated roles in promoting women’s empowerment (Grabe 2012; Huis et al. 2017; Kabeer 2012), there remains limited empirical support assessing multidimensional models. In the following sections we review literatures that aid in understanding the multiple contexts and processes that influence women’s empowerment at each level. Specifically, we integrate information on the context of the current study with literatures on societal narratives, liberation psychology, and identity to provide insight into the potential societal, relational, and individual influences shaping women’s lived experience. We then provide additional background on the qualitative methodology used for our research before describing the current study.

Macro Context

Feminist psychologists have long fought to illuminate the ways in which sociopolitical contexts shape women’s experiences. In Nicaragua, specifically, a social revolution emerged in 1979 when the Frente Sandanista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN; Sandanista National Liberation Front) overthrew the standing dictator. The political context stemming from the revolution provides a context for considering the relationship between the sociopolitical situation and women’s experiences. Although feminist thought and action existed in Nicaragua prior to the revolution, gendered inequities occurring in the context of the revolution gave rise to the country’s women’s movement, the Movimiento Autonomo de Mujeres (MAM; Autonomous Women’s Movement; Molyneux 2001; Randall 1994). In fact, previous research in psychology connects the experiences women had as members of the socialist revolution to their identification of gender injustice and consequent desire to work for equitable change (Grabe 2016; Grabe and Dutt 2015). More specifically, despite women’s critical and committed involvement during the revolution, concerns regarding women’s rights were largely marginalized by male leaders (Kampwirth 2004; Molyneux 1985). As a result, women began to separate from the socialist party and formulate their own political agendas based on the rights of women (Randall 1994). By 1992, Nicaragua had the largest, most pluralistic, and most autonomous feminist movement in Latin America (Grabe 2016; Kampwirth 1996).

In the decades since the emergence of MAM, feminist discourses have continued to influence Nicaraguan policy and society, albeit not without setbacks and discord. At the national level, for example, law 779 was passed in 2012 criminalizing violence against women and providing avenues for women to seek justice in cases of violence. One year later, law 846 was passed to reform 779, utilizing a family values narrative that encourages mediation between wives and husbands rather than jail time for those who commit violence. Many feminists in the country, including leaders of MAM, rejected this change because it promoted perpetrators’ impunity, and it downplayed the manner in which gender inequity leaves women more susceptible to experiencing violence (Jubb 2014). These conflicting positions and policies reflect alternative political narratives regarding idealized roles for women (i.e., as one who should hold her family together at all costs vs. one who is entitled to a life without violence; Jubb 2014). Moreover, they have psychological implications as individual women construct their own identities in the midst of conflicting narratives.

Previous research in political psychology suggests that individuals internalize both dominant and alternative narratives, and they use these narratives to make sense of the world and their place in it (Andrews 2007; Hammack and Pilecki 2012; Kerrick and Henry 2017; Toolis 2017). This means that individuals listen to the political messages to which they are exposed and incorporate at least some of the values and beliefs that undergird these messages into their understanding of who they are. For example, Hammack (2011) illustrated that both Palestinian and Israeli youth incorporated themes of the longstanding political conflict between the two groups when describing their own individual life history. Similarly, research on what compels individuals to engage in activism in a variety of contexts globally highlights the role of connection with political narratives, often involving the rejection of dominant narratives and connection with alternative narratives (Dutt and Grabe 2014; Frederick and Stewart 2018). Consequently, the narratives articulating the sociopolitical context of women’s status in Nicaragua likely influence women’s understanding of who they are and what is possible in their lives, and thus they are important to consider when exploring avenues toward greater empowerment.

Meso Context

The meso context can both serve as an intermediary between the macro and micro contexts and is a site of empowering or disempowering influence in its own right. The meso context involves community, familial, and other relationships that occur locally (Huis et al. 2017). The people and institutions with which an individual interacts in this context can express the narratives of the macro context through ideology in conversations, actions, institutional policies, and so on. Simultaneously, the ways people and institutions portray and treat women can play an important role in shaping individual women’s sense of self. Consistent with this notion, previous research illustrates the role of community relationships in shaping activists’ identities (Andrews 2007; Grabe et al. 2014; Savaş and Stewart 2018). Through community relationships individuals can identify patterns of inequity that compel interest in working for change.

Theories stemming from liberation psychology are particularly valuable for assessing how community contexts can serve as a site to promote more empowered realities for women. Theorists of liberation psychology assert that a central component of empowering processes is the deconstruction of ideologies that foster injustice and the increased understanding of how these ideologies influence individuals’ lives in local contexts (Burton and Kagan 2005; Grabe and Dutt 2015; Martín-Baró 1994; Montero 2012). For example, through collective discussion about violence individual women experience in their homes, women can come to recognize that their subordinated status makes women, as a group, more vulnerable to domestic violence. In other words, through processes that involve identifying the structural and collective roots of injustice, individuals can develop a critical understanding of existing social conditions and reject ideologies and practices that contribute to inequity (Dutt and Grabe 2017; Dutt et al. 2016; Grabe 2016; Montero 2007; Stake 2007). Rather than remaining complicit with inequitable policies, structures, and community practices, this realization can facilitate a mobilization process with the aim of seeing both concrete and ideological transformations within societies (Montero 2007). This can occur through a process of conscientización. Conscientización is a process in which individuals develop a critical consciousness surrounding their social and political realities and through multiple iterations, it evokes both analysis and action to repeatedly seek more just realities (Burton and Kagan 2005; Freire 1972; Martín-Baro, 1994). Importantly, the catalyzing and continuing efforts to create change often occur in collective spaces and involve both relational antecedents and outcomes.

Researchers have demonstrated across diverse samples how a process of conscientización is associated with increasing an awareness and intolerance of injustice and engaging in efforts to see these injustices rectified within one’s community (Brodsky et al. 2012; Grabe et al. 2014; Moane 2011; Montero 2007). In one example, researchers analyzed interviews with members of a group of Afghan women mobilized within a revolutionary organization (i.e., the Revolutionary Association of Women in Afghanistan), finding that processes involving conscious awareness, intention, and action all contributed to forming a community supportive of women’s rights and well-being (Brodsky et al. 2012). In a different context, Moane (2010, 2011) demonstrated how Irish students enrolled in courses on women and social class developed greater ability to identify patterns and sources of oppression in society, gained greater understanding of how structural oppression shaped their own lives, and developed a desire to make changes in their lives to avoid the perpetuation of oppressions. These findings demonstrate the powerful role communal settings can play in facilitating individuals’ awareness and actions related to empowering change. Additionally, they highlight the value of allocating more focused attention to how these empowering communal experiences shape understandings of the self.

Micro Context

Exploring empowerment from the micro context involves focused analysis on individuals’ own belief, actions, and experiences. To date, most research on liberatory processes in psychology focused on the intellectual, interpretive, and action-oriented responses of individuals and groups engaged in these processes, and less research is available on the personal transformation a person experiences. For example, the majority of the research that exists on conscientización emphasizes why and how community members begin to engage in reflections and actions geared toward creating community and societal change (Brodsky et al. 2012; Grabe et al. 2014). Researchers working from the perspective of liberation psychology have long argued that the approaches will always involve both community action and personal transformation (Montero 2012). Additionally, researchers advocating for the use of liberatory approaches in psychotherapy suggest that doing so can evoke meaningful changes in one’s sense of self for those involved (Russell and Bohan 2007; Singh 2016). Nevertheless, the research that exists emphasizes the intellectual rather than embodied psychological shifts individuals may experience as a result of engaging in empowering processes, highlighting areas in need of more research.

Latin American clinical psychologists write about the concept of autoconocimiento, which is the outcome of a reflective process through which a person acquires a notion of who they are, including their qualities and characteristics (Sáiz-Manzanares and Pérez Pérez 2016; Vázquez Piatti 2008). The notion of autoconocimiento emphasizes learning to know and love oneself while working with one’s own strengths and weaknesses. The concept connects to its closest English translation—self-knowledge—in that it involves understanding that one exists as an individual apart from others and the environment, that this awareness develops through conscious experiences, and that the process of developing self-understanding is simultaneously universal and culturally specific (Neisser 1988; Wilson and Dunn 2004). However, autoconocimiento, as described by Latin American theorists, also involves developing compassion for one’s own strengths and weaknesses, as well as an appreciation for who one is in the world (Sáiz-Manzanares and Pérez Pérez 2016; Vázquez Piatti 2008).

Although the concept of autoconocimiento notes the role of culture in contributing to one’s sense of self (Vázquez Piatti 2008), there is little discussion of the role of social structure and cultural ideology in shaping how people view who they are in the world and what they are capable of accomplishing. Examining feminist ideology and autoconocimiento simultaneously holds the potential to offer deeper insight into the individual transformation that may occur for women engaged in feminist empowerment-oriented experiences. A feminist autoconcimiento would take into account the powerful processes that unfold through liberatory action and reflection, and it would allow for an understanding of the self in connection to community and social structure. Similar to the concept of feminist identity development (Downing and Roush 1985), feminist autoconcimiento would involve developing an understanding of how gendered social structure influence one’s life. However, it also emphasizes a developing respect and appreciation for the self as one grows to understand who they are in deep connection to the structures, contexts, and communities that have shaped one’s life experiences and world views. Thus, feminist autoconcimiento opens the opportunity for an increasingly empowered understanding of the self because it allows for a deeper understanding of how aspects of the self have been constructed based upon social structures and ideologies—and can therefore be reconstructed based upon more desirable and resonant ideologies.

Taken together, through examining construction of the self with a lens cast toward the contributions and influence of multiple ecological levels, we can better understand how more empowered realities for and by women are created and experienced. We offer the concept of feminist autoconocimiento to offer insight into how women’s sense of self may be transformed through involvement in a feminist empowering organization. With this focus we aim to aid in identifying constructs and perspectives that further enable researchers of women’s empowerment to promote transformative change for women.

The Current Study

In the current study we assessed how women’s lives were influenced by participation in a feminist organization in rural Nicaragua, placing focused attention upon empowering transformations for individual women that occur via connection to multiple ecological levels. To do so, we employed qualitative analysis of interviews that were conducted with women who participated in the organization, seeking to understand what aspects of the organization were related to meaningful transformation in women’s lived experience. Additionally, we sought to gain greater understanding of the impact organizational participation had on women’s sense of self as articulated in women’s own beliefs about their value, capabilities and self-expectations.

Narrative theorists suggest that how individuals develop a particular understanding of the self is recounted in narrative form (Josselson 2011; McAdams 1989). In other words, individuals share their understanding of who they are and what has influenced them through the conversations they have and the stories they tell (Crossley 2000; Sarbin 1986). Consequently, analysis of qualitative interviews designed to assess women’s interpretation of their influence by their organizational involvement creates opportunity to examine the ecological intricacies and interconnections shaping understandings of one’s life. Furthermore, by employing qualitative interviewing that left open opportunities for women to reflect upon and articulate their own ideas regarding how their lives had been influenced by involvement in the organization, our research prioritizes participants’ agency in accounting for what has been meaningful in one’s own experiences. To this end, we focus upon women’s own interpretation of their experience in our interviewing and analysis.

Method

Study Setting

Interviews were conducted with women residing in a rural community called Malpaisillo, in the department of León, Nicaragua, who were members of Xochilt Acalt. The organization emerged from the women’s movement in Nicaragua (MAM) in an effort to support women in the rural sector. The organization formed shortly after a conservative shift in presidential power in 1990 introduced several neoliberal structural adjustment policies that yielded severe cutbacks to public sector commitments. These policies were associated with weakening the already precarious government support for women’s rights. Within this context of decreasing social support from the national government, Xochilt Acalt was founded by a self-mobilized group of women in 1992 specifically to address high levels of ovarian cancer in the remote area in which they lived. Over the past two decades, the organization has expanded to address additional problems and demands from women that were arising within the community including: lack of food, illiteracy, lack of resources for family planning, high levels of gender-based violence, high rates of male migration for work, and a need to improve unequal power relations between women and men (Montenegro and Cuadra 2004). To date, the region remains one of the most impoverished areas in the country.

Participants

The current study is part of a larger, mixed-methods study on feminist transformation in rural Nicaragua. In the larger study, 304 women completed quantitative surveys that assessed specific outcomes (e.g., agency, sense of solidarity, civic participation) related to involvement in the feminist organization (see Dutt 2017, 2018 for additional details and findings on the larger study). IRB approval was obtained from the authors’ universities before beginning data collection. Women who completed the survey were asked if they were willing to be contacted for a follow-up interview on similar topics that were touched upon in the interview in which they would be given more time to expand upon their answers in a conversational manner. All but two of the participants who completed the survey portion agreed to be contacted for the follow-up interview. Each day after approximately 20 surveys had been completed, we randomly selected 2–3 women to be contacted for follow-up, resulting in 14 of the 304 women who completed the survey also participating in a qualitative interview. The interview included questions asking about what women’s daily life was like; their relationships with their partners, children, and neighbors; their involvement in Xochilt Acalt; changes they had seen overtime in the community; and their goals for their own lives and communities. (The full interview protocol is available in the online supplement.) All of these interviews were conducted by the first author (a multiracial, Indian and White, women from the United States), were administered in Spanish via simultaneous translatn with the aid of a bi-cultural female interpreter from Nicaragua, and occurred privately in women’s homes.

Prior to beginning the interviews, the interviewer explained that the purpose of this interview was to ask about women’s experiences and opinions about their lives and community, their relationships with other people in their community, and their experiences with Xochilt Acalt. Women were informed that the researchers did not work for Xochilt Acalt and that, although we would share the overall findings with the organization, everything they shared as individuals would be anonymous. All interviews lasted between 35 and 60 min and occurred privately in women’s homes. Following guidelines for achieving saturation, interviews ceased when a minimum of ten interviews had been conducted and three consecutive interviews had been completed with no new topics emerging (Francis et al. 2010). This was determined based upon the extensive notes the first author took about each interview soon after each was finished.

Interview Analysis

For the present paper, we utilized inductive, thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006) to analyze the interviews, with an overarching goal of identifying patterns in how women were influenced by participation in the organization. Specific hypotheses were not tested rather our focus was on identifying what women described and interpreted as being linked to meaningful change in their own lives and communities. Our analysis began with reading, re-reading, and taking detailed notes about the interviews in their entirety and noting overarching patterns as well as incongruences to develop a comprehensive framework that accounted for inconsistencies and differences in both the individual and collective narratives (Josselson 2011). The first author then randomly selected five interviews to complete line-by-line coding, and she develop initial coding categories. This involved going through each line of the interviews, writing down possible codes that are reflected in each portion of the text and noting any possible recurring themes that were expressed. Extensive notes were taken throughout, and a list of initial recurring codes were developed. Next, along with two trained undergraduate research assistants, we applied these codes to the remaining interviews. Through discussion and refinement, we ended up with a final list of seven codes with two overarching themes that we focus upon in the present study. The two overarching themes involve (a) exploring various factors in the organization that women articulated as being meaningful in improving their lives and (b) how involvement in the organization affected women’s own beliefs about their worth and capabilities. In both themes analysis centered on how the macro, meso, and micro levels—as well as their interconnections—influenced and manifested in empowering realities for women.

Upon developing the final coding scheme, consensus coding was used to analyze all the interviews (Ahrens 2006). This involved the first author and both research assistants independently coding each of the interviews and then meeting to compare results. Any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. Further validity of findings was sought via ongoing conversations regarding the fit of the interpretation to the research questions and interviews (Elliott et al. 1999; Madill et al. 2000).

Results

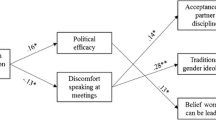

Table 1 provides information about each woman interviewed, including the programs in which she participated in at Xochilt Acalt. Note that each of the programs described involve multiple meetings over the course of several months on the specific topic (e.g., reproductive rights, land rights). The programs are led by women who have previously completed the same program and have received training on facilitation. The facilitators offer the programs in their own neighborhoods. They are free to organize them in a manner that best suits the community; however, they are always structured around fostering reflection, conversation, and action. The environmental promoters and community defenders are members of groups who have received additional training and are tasked with spreading awareness of environmental stewardship practices and supporting women experiencing violence, respectively. Table 2 provides an overview of each coded theme as well as the factors composing each theme and an example.

Theme 1: Moving Forward

The first theme explores aspects of the organization to which women frequently connected to facilitate of empowering outcomes in their own lives. Members of Xochilt Acalt often expressed a sense of “moving forward” [avanzamos….] in their descriptions of how they had been affected by participating in Xochilt Acalt. In doing so, women made clear that they felt being involved in Xochilt Acalt facilitated improvements in their own lives, their families, and their communities in a manner that enabled them to address barriers to their well-being and progress toward achieving their goals. The manner by which this was accomplished was not one-size-fits-all. Rather, women identified different factors within the organization, and often a combination of several factors, that enhanced their ability to overcome several adversities in their lives and communities. Importantly, the various aspects demonstrate the way factors connected to multiple ecological levels worked together to create an empowering context for women. What follows is a description of the four factors that were described most prominently in the interviews, detailing how involvement in Xochilt Acalt supported transformative changes in women’s lives.

Knowledge About Women’s Rights

In each interview women discussed how involvement in Xochilt Acalt led to gaining knowledge about women’s rights, illustrating connections between one’s understandings of the macro context and empowering possibilities. Women often explained that prior to their involvement in the organization they were not aware of the concept of women’s rights, and they had little reason to believe that their lives could be organized in a manner that reflected valuing women’s worth and perspectives as equal with men’s. In other words, prior to involvement, women had little to no exposure to feminist narratives that described women and men as having equal worth and value. Through discussions that occurred in Xochilt Acalt, women gained knowledge that they were entitled to be valued equally with men and, moreover, that there were sources of support to which they could turn when their rights were not upheld.

For example, when asked what she gained from being involved in Xochilt Acalt, one woman replied:

We learned how to identify our rights, how to speak without fear. When you are a person who is going through difficult times, when you are being mistreated, that you don’t have to go through that difficulty on your own, that there is help they [people at Xochilt Acalt] can provide. (P #40)

As this excerpt exemplifies, through involvement in the organization women learned that equitable treatment was not something simply to be hoped for, but rather was a right that could be demanded based on societal, or macro-level, understandings of human rights. In other words, the organization introduced new narratives about the worth of women related to the discourse on women’s human rights. The notion that women had rights and legal protections could shift women’s understanding of their own value through validation that they were worthy of just treatment. Additionally, the development of an alternative narrative highlights how the meso and macro contexts interact to create a community committed to actualizing women’s rights, thereby promoting empowering realties for women.

An interview with another woman specifically emphasized the transitions she and other women in her community experienced as a result of the knowledge they gained from being involved in Xochilt Acalt:

Respondent: Now we think differently, a better way, of who we are as women. We think that we should value ourselves…Before I thought that men were the ones who were bosses in the house, that they were the ones to make decisions about everything…Now I know that both men and women can make decisions, that we have the same rights, that we are both free to express ourselves.

Interviewer: What happens if a husband doesn’t agree, if he still thinks that he is in charge?

Respondent: For example, if one is being mistreated, they tell them that they can go to la comisaría [local law enforcement offices, specifically for women], or if their partner is not helping them with their children financially. (P #39)

This excerpt further illustrates how the macro, meso, and micro contexts were collectively contributing to possible improvements in women’s lived experience. The knowledge women gained about their rights via equitable narratives led to transformations in women’s understandings of their value, self-image, and capabilities (in their micro context). Importantly, women did not naïvely believe that, upon developing an understanding of their own rights, their husbands or others in the community would be in agreement and alter their treatment to show support for women’s rights. Instead, knowledge of meso-level community structures that were available to ensure women’s rights were upheld and shared, providing women with knowledge of actions in which they could participate to increasingly authenticate their own self-worth. Thus, gaining knowledge about women’s rights through involvement in Xochilt Acalt was a critical element in supporting women’s empowerment because it offered a legitimized narrative about the worth of women that served as a springboard for enhanced beliefs about women’s own worth. Moreover, although the introduction of new societal narratives primarily demonstrates empowering transformation of the macro context, the role of the organization in delivering the narrative and its impact on individual women’s understandings of possible actions they could take highlight interconnections among all three levels.

Community

A second factor that contributed to women’s ability to “move forward was belonging to a community with other women for comradery, as well as practical and emotional support. Thus, the collective experience of encountering empowering narratives about the worth and value of women promoted transformation in the meso context that further supported positive experiences and an enhancement in women’s sense of self. Several interviewees explained that the organization facilitated a space for women to develop connections and realize the reality of shared experiences with other women. Despite that many of the women had neighbors living nearby, several interviewees shared that they were unlikely to connect in meaningful ways with their neighbors prior to involvement in the organization, due in part to expectations that women should remain in their own homes and be devoted to their families. However, through involvement in Xochilt Acalt women felt more united with one another.

Through this sense of connectedness women felt encouraged and supported in seeking to create empowering changes in their lives. For example, one woman shared:

Respondent: I must say, before we didn’t really do anything together, but since we began to organize with [Xochilt Acalt], now we have unity among the women in the community here.

Interviewer: What were your relationships like with your neighbors before you were organized with Xochilt?

Respondent: Before, we didn’t really relate to each other that much. Everyone was in their individual homes, and we didn’t have much of a relationship with each other. But now we have relationships with each other, and we meet more also, to have all of us in the community move forward. (P #149)

Realizing a sense of shared experience and fate with other women through discussions that occurred in the organization encouraged women to feel as though they could rely on each other, reducing their feelings of isolation. Thus, these experiences highlight shifts at the meso-level that illuminate how changing perceptions of community relationships influenced women’s individual experiences. Although women could cite people to whom they would talk in times of hardship when they reflected on their lives prior to being involved in Xochilt Acalt, the shared experience of collective consciousness raising that occurred in the organization deepened women’s sense of connection to each other. Hardships then were less likely to be seen as individual problems, but rather as areas of collective concern to be addressed in order to advance the well-being of everyone in the community.

Having a sense of community also facilitated an understanding that women could unite with other women, and in doing so, they could collectively position themselves as more powerful and agentic than the way in which individual women were traditionally perceived. This realization meant that women could use their collective agency to evoke additional change in the meso context. For example, another woman made it clear that the benefits of having a community had practical implications when it came to ensuring that women’s rights were upheld:

Interviewer: So you earlier said that men respect women more when they’re involved in Xochilt--

Respondent: Yes, because there are some men that are machista [i.e., machismo, chauvanist], and I imagine they must be thinking, she is a woman who is a member of [Xochilt], she is a woman who maybe has support… they feel more fearful. (P #194)

Belonging to a community signaled to men that women were not alone and vulnerable. In this case, a woman who is organized through involvement in Xochilt Acalt has others who can support and defend her if needed. In other words, the meso context now reflects solidarity among women rather than isolation. In fact, most women responded that their husbands eventually began to express more respect toward their wives when they were involved in Xochilt Acalt.

Consistent with previous literature, having a sense of community can contribute to an empowering process because it reduces isolation and creates a context where women experience emotional and motivating support to seek change in their lives (Brodsky et al. 1999). Among the women interviewed for our study, belonging to the organization also provided a form of protection and respect when interacting with men who may otherwise have posed as a barrier to women’s well-being. In this way, we can see how the meso-level community relationships afforded through Xochilt Acalt could produce both ideological shifts and incentives for action, begetting a process of conscientización.

Space for Community Mobilization

A third factor, again primarily highlighting meso-level connections, that women described gaining from Xochilt Acalt was physical space to discuss issues that existed in the community, along with opportunities to explore ways to collaboratively address their problems. This space allowed women to share their perspectives on problems in the community and to strategize to address those problems. This factor is distinct from a sense of community because it involves setting aside literal time and space to specifically plan and execute community mobilization. In many cases having the space may have been necessary to create this sense of community. However, the two are distinct because women’s descriptions reflect separate gains: a sense of community provided meaningful and supportive relationships and a space for community mobilization provided time and location for strategizing pathways for change. Having this setting for discussion demonstrates additional transformative power of the meso-level in facilitating an empowering context because it afforded women opportunities to take charge in gaining resources and creating change for their community.

Illustrating the value of the space for mobilization, when asked what she talked about at Xochilt Acalt programs, one woman shared:

Respondent: Sometimes we talk about how there are things that are missing in these communities. For example, we talk about having a water tank because the one that we have is small. And we talk about the needs of the community. (P #187)

Shared discussion about the needs of the community is an essential component of working toward the empowerment of both individuals and communities because it allows people to come together to determine the goals they would like to achieve collectively and to deliberate about how they would like to see their own communities structured in the future. In our study, this discussion emphasized that women are capable of working to address their concerns. Furthermore, the communal discussion highlights women’s collective interests in transforming the meso-context. Equipped with knowledge of equal worth and value, women seek to identify sources of hardship that can be addressed.

Similarly, another woman explained some of the outcomes of collective resistance when she and other women who were organized through Xochilt pressured the mayor of the municipality to bring electricity into their community:

Interviewer: What do you think the mayor’s office thought when they saw a bunch of women coming in asking for electricity?

Respondent: At the beginning they would close the doors. They changed the place where they were having their sessions in the municipality, but we knocked on their doors until they answered us… That’s the way we did it, and we worked together on it until we got it. Eventually the engineer came and started measuring [in preparation to set up electricity] and we said, “Wow we got it.”

Interviewer: How did you keep each other motivated?

Respondent: In previous years we gave up, really, but that year we said we are going to do it, we are not going to give up…before we would have this knowledge but we just kept it as knowledge. But eventually we said, we have this knowledge, but if we don’t exercise this knowledge we are not going to get anything. We had rights as citizens. (P #149)

Again at the meso-level, the space provided for collective strategizing at Xochilt Acalt allowed women in the community to deliberate collaboratively and work as agents of change. Women learned strategies for enacting change, a sense of collective efficacy, and skills for perseverance. As demonstrated in the prior example, the space catalyzed a process of conscientización. In other words, the organization facilitated a space for reflection and action that encouraged collective involvement in challenging and transforming oppressive narratives and action to produce equitable change in the community. Thus, the space created by Xochilt Acalt to discuss community issues extended well beyond mere physical location and a list of topics to discuss.

Material Resources

The fourth factor stemming from involvement in Xochilt Acalt that women consistently connected to facilitating of positive changes in their lived experience was gaining material resources (e.g., livestock, seeds for planting) and training on how to use these materials. The combination of resources and training delivered to individual women provided insight into ways the organization worked to transform the micro-context by increasing women’s individual sense of agency. Gaining resources through the organization frequently made it possible for women to support themselves and their families, despite the very impoverished conditions in which these women lived.

For example, when asked why she became involved in Xochilt Acalt, one women explained:

I liked the project and the way they were doing things here in Nicaragua…They teach that it is important that we love ourselves, that we be self-sustainable. That we do not depend only on the men and on husbands. They supported us with a couple of cows, sheep and goats. It was like a revolving fund so that then we can support other women. And they supported us with fences for the animals, with infrastructure like wire, silos so that we can also store the harvests (P #139)

By emphasizing that she learned to love and value herself, this excerpt exemplifies how the organization incorporated transformation of the micro context in producing equitable change; women gained an understanding that they have value and ability and should be viewed in a loving manner. Additionally, the revolving fund meant that women could breed the animals they received and subsequently return one to the organization. This allows women to have an explicit role in contributing to the organization and supporting other women. To do otherwise would prevent a comprehensive restructuring of power relations and would not serve as an empowering setting for women.

The organizational culture of Xochilt Acalt was grounded in an understanding that the goal was to increase the self-sufficiency and self-determination of women in the communities. Thus, although the organization provided material resources, they were careful to do so without promoting the idea of the organization as benefactor, nor fostering a sense of dependency among the women who received the materials. Moreover, through the support and training on how to use material resources, women gained a greater understanding of their own individual capabilities and capacities to create change. Women were not merely the recipients of resources, but rather they were actively engaged in a process of transforming their own lives and promoting opportunities for others to do the same. In this way, the values that were shared about women’s capabilities allowed individual women’s actions (the micro context) to contribute to creating an increasingly transformative context for other women in the community (the meso context). Overall, the organization invoked the influence and interconnection of multiple ecological levels to foster empowering change for women.

Theme 2: Feminist Autoconocimiento

The second theme shifts the focus away from the setting, and instead it centers on women’s development of a sense of feminist autoconocimiento and how this was shaped by involvement in the organization. Throughout the interviews, women discussed how involvement in Xochilt Acalt lead women to view themselves as what they referred to as “organized women” [organizados]. The reference to being organized in this sense was not a reference to a behavioral trait (e.g., being tidy), but rather was a term pointedly used by women as a marker of their identity. As evidenced in the interviews, an organized woman was one who viewed herself as part of something larger—a collective working to create change—and as women capable of offering valuable contributions to their homes and communities. Identifying as an organized woman was therefore somewhat akin to identifying as a feminist, expressly including a commitment to mobilization and action with other women. Women’s explanations of what it meant to be organized illustrates the development of feminist autoconocimiento. This was demonstrated through the expression of three factors: (a) a commitment to asserting the worth of women, (b) a belief in one’s own capacity to contribute to change, and (c) the idea of one’s self as a promotora – a person who can and does carry out knowledge and support to women in the community. Consistently, women incorporated multiple ecological levels in the internalization of a more empowered understanding of the self.

Asserting Women’s Worth

All of the women interviewed for our study expressed a belief that women deserved to be treated well and have the opportunity to live without violence or harassment. Although women typically do not need involvement in an intervention to experience and express dissatisfaction with the inequitable treatment they face as women and wish for alternatives (Grabe et al. 2014), exposure to powerful and supportive narratives though Xochilt Acalt enhanced women’s commitment to asserting women’s worth by ensuring that the realization of women’s rights and worth were an unwavering priority.

A conversation with one woman about why she initially became a member of Xochilt Acalt illustrates this commitment:

Interviewer: Why did you first join Xochilt Acalt?

Respondent: Because I like the way they show you how to treat yourself. Sometimes, it’s like, they help you, awaken yourself. You learn about how you should be treated by your partner…There are men that hit women, but now we have less machismo, and I like it.

Interviewer: You said “awaken yourself” [despertarte]… what do you mean by that?

Respondent: You know my husband has never hit me, but in other ways he wouldn’t treat me well. In my case now, he doesn’t say those things anymore… if you allow them to humiliate you all your life, then it will not go away. (P #113)

This woman, like several others, initially joined the organization because she was interested in being involved in a space that was working to authenticate the worth of women. Involvement in the organization then promoted a consciousness that emphasized deconstructing the sources of diminished self-worth (e.g., violence and mistreatment by partners) and working toward their transformation. Discussing at the organization women’s rights to freedom from violence in their homes infused a commitment to authenticating the self-worth of women into each woman’s identity and equipped her with the confidence needed to work toward ensuring this belief was upheld in her relationships. In describing an experience of “awakening” [despertarte] and why women should not be humiliated, the prior respondent is explaining a transformation of the micro context, and an emergent process of feminist autoconocimiento.

Although most women spoke of the importance of speaking up for oneself or others when women’s rights were being violated, most interviewees also possessed an acute awareness of the limited situations that exist due to men’s controlling behavior. Rather than blaming women for the violence or other inequitable hardships they faced, women remained adamant about transforming beliefs about women’s value in their communities. Awareness of the existence of equitable narratives about women’s value and worth encouraged women to become carriers of this narrative, with the goal of supporting greater equity.

For example, another woman explained the process through which men came to realize the importance of respecting and valuing women:

Interviewer: Do you think that men respect women now because they fear them or do you think that they respect women more for other reasons?

Respondent: I think now they realize that women also have an equal value to them. Because before they used to always think they were more valuable than women, and now they see that we are just as capable as them to do things… That as well is why they value us a bit more. Because they see we have equal capacity to them. (P #139)

All 14 women similarly expressed an understanding that creating a context where women would be treated equitably required shifting the consciousness of men, as well as women’s, in order to achieve viable transformation. Upon incorporating narratives that authenticated women’s equal value and worth into one’s sense of identity, women sought to embody and become carriers of the narrative to promote broader acknowledgement of equitable narratives in the meso and macro domains. The extent to which Xochilt Acalt members understand that women have the same worth and capacities as men necessitates that changing beliefs about women’s value is an unwavering priority.

Capacity to Create Change

In addition to self-worth, women who were organized in Xochilt Acalt also expressed a belief that they were capable of accomplishing their goals and contributing to their homes and communities in a meaningful way. In doing so, women demonstrated a sense of personal efficacy by actively seeking changes in their lives and asserting their capabilities. This highlights the expression of an internalized equitable narrative, but also illustrates outcomes associated with transformations in the meso and micro contexts within the household. For example, rather than deferring to their husbands, women came to view themselves as equally capable agents in their homes. One woman described how her role with her husband and children changed after she became involved in the organization:

[Now] I see and I decide what is good for me. If there is work that is convenient for me, that is good for me, or that is not good for me, I decide. And I also make decisions about the kids. Because before the father made the decisions about the kids…he would say “No, the kid can’t go out” and now, if I think it is normal and fine, I say it’s not bad for him to go out…When I was growing up my mom would say that it was not good for an adult to talk about intimate things of woman… now I talked to [my daughter] about the good things and the bad things that can happen to a woman. And when I entered Xochilt I was always very quiet, very reserved. I was shy, to talk about of those things. But not anymore. (P #114)

As this quote demonstrates, women involved in Xochilt came to view themselves as active agents in their relationships. Women became increasingly able to assert their perspectives and impact the dynamics of their families, in addition to making decisions about their own lives. In doing so, women expressed and internalized a sense that they have the capacity to contribute equally and meaningfully in their homes.

In addition to disrupting norms that silence and marginalize women in the household, being involved in Xochilt Acalt also encouraged women to assert their opinions and perspectives in community spaces. For example, one woman described how she came to feel more capable of using her voice within the community from seeing other women do the same:

Interviewer: Can you tell me a bit about what your life was like before you were involved in Xochilt Acalt?

Respondent: I was very timid, very shy.

Interviewer: What changed for you?

Respondent: I said to myself, if they [other women organized in Xochilt] can do it, I can do it. I can do it the same way. I have not been able to study beyond the fifth year of school. But my words, they also can do something. The others used to say that I could not speak… and they said “Wow you were very quiet’,” so I said, “things change.” (P #146)

As this quote exemplifies, through connections with others at Xochilt Acalt, women can to understand how inequitable life experiences had limited women’s perception of their own capabilities. Viewing limitations through this structural lens then allowed women to see how they could change their actions in the community space—and with it beliefs about their own value. The organizational culture within Xochilt Acalt around prioritizing women’s participation encouraged women to view themselves as individuals with perspectives capable of, and worth, being shared. Thus the space evoked a sense that women could contribute to transforming their community context, further promoting a sense of feminist autoconocimiento. By incorporating a structural understanding of the conditions that shaped one’s life, women could identify actions to resist or transform limitations, and they increasingly participated in desired actions in the community and household.

Promotora

The third factor involved in developing an identity as an organized woman was viewing oneself as a promotora—a person who can and does carry out knowledge and support to other women. The notion of being a promotora extends beyond the English translation [promoter] because the women are not merely taking on a role of promoting women’s rights. Rather, women see it as part of their ingrained identity as people charged with spreading awareness of, and upholding, women’s rights. Engaging in activities that increase the well-being of women in the community becomes a primary goal for Xochilt Acalt participants because they become carriers of the values that are shared in the organization. Various examples of these efforts were shared in all of the interviews with Xochilt members and covered a range of activities and situations. Consistently they highlight how all three contexts—macro, meso, and micro—each contributed to creating a more empowered understanding of the self. Then in turn, these levels became avenues for women to enact further transformation for others.

For example, several women described situations where they worked to help women who experienced violence:

There was this couple who were dating, but then the man started talking really badly about the woman, saying really bad things to her. So, we went to the community defender [individuals trained to intervene in cases of domestic violence, including verbal abuse], and she helped them to go through a mediation and improve things for her. (P #40)

The women interviewed knew it was unacceptable for any woman to be mistreated, and they further saw themselves as individuals who could contribute to promoting better experiences for other women. Thus, women collectively sought to address inequities in the meso context, and they saw this as an important role with which they identified. Other Xochilt Acalt members described engaging in activities to create more systemic change for women in the community. For example, another woman shared her experience mobilizing as part of a health campaign through Xochilt Acalt to address issues related to women’s health in her community:

There was a concern about health in this area. We went house by house asking about the diseases, asking about some of the illnesses, we recorded everything... And it was very important because [as a result] a lot of the women went to the clinic, the health clinic, and were given free counsel. (P# 187)

The sense of capability and personal efficacy women gain and have validated through participation in Xochilt Acalt grew to become a belief about the capacity of women more broadly. Working to promote women’s rights and well-being thus became an important part of women’s identity because it was an expression of a deeply felt belief that women have the same capacities as men, deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, and should be given full opportunities to participate equitably in public spaces.

Cumulatively, throughout the interviews it was evident that becoming involved in the organization was not simply an activity in which women participated. Rather, it involved a personal transformation into developing an identity as an organized woman. The culmination of developing a commitment to asserting women’s worth, a belief that one could contribute to creating change, and viewing oneself as a promotora illuminates the development of feminist autoconocimiento (i.e., a sense of self understanding, untainted by the systems of power that devalue women). In summary, findings at multiple levels of analysis suggest that what women developed though participation in the organization was the knowledge and space to gain a sense that they were cable of creating and promoting change in their own lives and communities. We discuss the particular importance of our findings for creating transformative change in the area of women’s human rights in the following.

Discussion

Although theorizing about multiple levels of women’s empowerment has been ongoing for nearly 20 years (Huis et al. 2017; Kabeer 2012), there has been little empirical work, to date, identifying how mechanisms that operate at different levels are related in a manner that can lead to transformative changes relevant to the actualization of women’s human rights. Moreover, despite that issues of empowerment and participation in organizations that have been examined within the field of community psychology, most prior research has focused on individual psychological outcomes without adequate attention to community-based processes (Campbell and Jovchelovitch 2000). Through investigation of participation in a community organization in the current study, we identified mechanisms for change connected to multiple ecological levels that subverted the root sources of inequity (e.g., ideology, control over resources), rather than adopting a co-opted discourse of empowerment driven by outside interventions, often guided by a neoliberal agenda.

Our findings underscore the importance of local community-based processes in the development of women’s capabilities that may play a role in the actualization of women’s human rights. In particular, we found that macro-level access to knowledge about women’s human rights, provided by a community organization, shifted dominant narratives surrounding gender ideology thereby contributing to a transformation in women’s understandings of their value and capabilities. Moreover, meso-level community connections allowed for the development of solidarity relationships that influenced individual levels of capability (described as self-sufficiency and self-determination) and promoted opportunities for women to collectively position themselves for change. These results suggest that macro-, meso-, and micro-level outcomes are linked and overlapping and cannot be fully understood independently of each other.

Across disciplines, the importance of individual capabilities in the achievement of gender justice has long received critical attention (Nussbaum 2003; Sen 1995). In writing about women’s human rights, Nussbaum (2003) argued that capabilities are closely related to human rights and suggested that rights, despite being granted by law, are only effective if individuals are capable of politically exercising those rights. According to Nussbaum, (2003), thinking in terms of capabilities can provide a benchmark to consider what it actually means to secure rights to women. Although these ideas have been theorized by feminist economists for more than two decades, they have not been empirically examined in psychology. The findings from our study provide important insight into the mechanisms by which capabilities are supported.

In particular, women involved in the community organization described gaining greater control over their lives in four primary areas related to community-based processes: knowledge about women’s rights, sense of community, space for community mobilization, and material resources. Outcomes related to these factors at multiple levels contributed to equipping women with the capabilities to create desired changes in their own lives and their communities. More specifically, providing knowledge about rights and material resources were elements of the community organization that catalyzed empowering possibilities because they shifted dominant narratives and opportunities among women. In addition, having a space for the discussion of community mobilization, along with a solidarity network that supported women through the process, were key elements in changes that allowed women to protect their own or others’ rights (e.g., in areas of harassment or violence).

In addition to the factors we already discussed, another key finding was that community-level participation resulted in powerful processes whereby reflecting on knowledge of women’s rights, women’s equal value, and related liberatory action (e.g., participation in decision-making) led to expressions of feminist autoconocimiento. According to critical psychologist Martín-Baró (1994, p. 18), “[conscientización] joins the psychological dimension of personal consciousness with its social and political dimension, and makes manifest the historical dialectic between knowing and doing, between individual growth and community organization, between personal liberation and social transformation.” Expressions of feminist autoconocimiento demonstrated that through gender reflection processes initiated by the organization, women acquired a newfound sense of self-understanding that was rooted in an awareness of women’s rights and a capacity to authenticate the worth of oneself and other women.

Practice Implications

By itself, finding that social identities that challenge marginalization are linked to social action is not novel (Campbell and Jovchelovitch 2000). Indeed, some of the key elements of feminist autoconocimiento we report overlap with feminist identity development (Downing and Roush 1985), namely that knowledge can shift narratives and that solidarity can lead to action. However, the elements of feminist autoconocimiento related to individual capabilities differ from the development of feminist identity and offer new insight into how social identities become potent tools for social change. Specifically, as part of the development of feminist autoconocimiento, women in the current study described outcomes related to self-determination and self-sufficiency—capabilities that extended beyond individual identity and that were related to the actualization of women’s human rights. On the surface, capabilities may seem related to what Downing and Roush (1985) labeled active commitment; but, there is a difference between a commitment, however deep it may be, and acquiring the capability to effect change. Moreover, in their description of feminist identity development, Downing and Roush acknowledge that few women truly evolve to the active commitment stage. Our findings, in contrast, suggest that developing the capability for change is an integral part of feminist autoconocimiento. In sum, when investigating or attempting to implement processes of social change at multiple ecological levels, professionals would be well advised to consider the role of feminist autoconocimiento (i.e., a targeted focus on enhanced capabilities) in areas relevant to the actualization of women’s rights.

Outlining the ways the particular partnering organization, Xochilt Acalt, facilitated empowering transformation for women at multiple ecological levels underscores the power of seeking to address root sources of inequity that manifest at multiple and intersecting ecological levels. However, in regard to practice implications, we do not suggest that the findings imply a specific blueprint that should be followed to enhance equity and transformation. Particularly, given the histories of colonial and neoliberal exploitation impacting many disenfranchised communities, there should great incentive to facilitate contexts with a bottom-up priority whereby local women’s concerns and perspectives are encouraged. Nevertheless, researchers evaluating the success and reaches of empowering settings are encouraged to consider multiple ecological sites of transformation and to prioritize women’s own articulations of what meaningful change looks like, rather than approaching an assessment solely with a priori assumptions about what renders positive change.

Similarly, in the context of neoliberal economic policies that increasingly call on individuals to find solutions to their disenfranchisement, we want to take care that we are not suggesting that the burden of having rights recognized falls on the backs of individual women who have had their rights denied. Nor do we want to further support the proliferation of non-governmental organizations that have taken charge of social services that used to be upheld in the public sector in a manner that absolves States from the responsibility to support constitutional guarantees. Rather, the findings in the current study that fall in line with the capabilities approach would suggest that one route to change could involve governments considering what obstacles exist to women’s full and effective empowerment, devising measures that address these obstacles even if doing so requires a constitutional amendment (e.g., legislating equal political participation).

Limitations and Future Directions

Given the limitations of cross-sectional data, an oft asked question is, which came first: in this case women’s empowerment or their participation in the organization? Although we do not have data from our sample to directly answer that question, women’s own accounts of the transformation they experienced through involvement in the organization lends substantive credibility to the role of the organization in facilitating empowering change. Furthermore, previous research collected in the same communities, with women who also participated in Xochilt Acalt can lend additional insight. Grabe (2010) used structural equation models to examine the role Xochilt Acalt in empowerment processes that involved gender ideology, relationship power, and receipt of violence. Although it may be theorized that women who were already empowered are those who became involved in the organization, there was limited support for alternative path models that suggested such directionality (i.e., positioning progressive gender ideology as the predictor). Moreover, it was also reported that women involved in Xochilt Acalt had comparable levels of lifetime partner violence to women who were not participating, suggesting that the sample of women involved were not simply the women whose husbands would allow it.

Additionally, our findings suggest that it may be important to involve local community organizations in interventions that strategically deliver knowledge surrounding women’s rights. At the same time, we understand that the pathways whereby gender inequities impact women’s human rights are many and complex, with power differentials undermining women’s access to rights-related knowledge. As such, we recognize that our study was limited in assessing the full host of variables that undermine women’s access to knowledge and that these factors will vary community by community. Nevertheless, we believe that the role of community and networks of solidarity, however defined, have the potential to transmit knowledge and be a stock of resources, while holding the possibility to establish dialogue with the objective of social change.

The community-academic partnership in the current study helped advanced our understanding of processes related to the actualization of women’s human rights and has the potential to contribute to progressive social movements the world over that are rooted in understanding how multiple levels of society either interrupt or prohibit the advancement of women. In the current study, the community organization viewed women’s rights as a starting point. In contrast, if we were to use mainstream U.S.-based scholarship to understand processes related to women’s rights and empowerment, we would be limited because discourses and interventions in the United States do not view women’s concerns as rooted in a human rights framework (Grabe 2017). Synergy between social movements and scholarship allows us a window into realities that would not otherwise be represented in research produced in psychology. Scholar-activism is defined by Sudbury and Okazawa-Rey (2009, p. 3) as “the production of knowledge and pedagogical practices through active engagements with, and in the service of, progressive social movements.” Because there remains a paucity of research in psychology that examines women’s human rights and related activism, future investigators need to broaden the scope of research to consider how scholar-activism can contribute to movements aimed at women’s capabilities for change.

Conclusions

The findings from our study provide important insight into the mechanisms by which change on multiple ecological levels can subvert root causes of gender inequality in a manner that enhances women’s capabilities and the actualization of their rights. Although scholars and activists across disciplines have discussed these processes for decades, there has been sparse contribution on these topics from psychology to date. Sound feminist methodology surrounding the investigation of processes that impact women’s rights is imperative to understanding the obstacles women confront to actualizing their rights and implementing interventions that can contribute to transformative social change.

References

Ahrens, C. E. (2006). Being silenced: The impact of negative social relations on the disclosure of rape. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-006-9069-9.

Andrews, M. (2007). Shaping history: Narratives of political change. Cambridg0065, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Batliwala, S. (2007). Taking the power out of empowerment–an experiential account. Development in Practice, 17(4–5), 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469559.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2015). Living in metaphors, trapped in a matrix: The ramifications of neoliberal ideology for young women’s sexuality. Sex Roles, 73(7–8), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0541-6.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brodsky, A. E., O’Campo, P. J., & Aronson, R. E. (1999). PSOC in community context: Multi- level correlates of a measure of psychological sense of community in low-income, urban neighborhoods. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 659–679. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199911)27:6<659::AID-JCOP3>3.0.CO;2.

Brodsky, A. E., Portnoy, G. A., Scheibler, J. E., Welsh, E. A., Talwar, G., & Carrillo, A. (2012). Beyond (the ABCs): Education, community, and feminism in Afghanistan. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(1), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20480.

Burton, M., & Kagan, C. (2005). Liberation social psychology: Learning from Latin America. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 15(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.786.

Campbell, C., & Jovchelovitch, S. (2000). Health, community and development: Towards a social psychology of participation. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 10(4), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1298(200007/08)10:4<255::AID-CASP582>3.0.CO;2-M.

Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018854.

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women's empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3210.

Cornwall, A., & Eade, D. (Eds.). (2011). Deconstructing development discourse: Buzzwords and fuzzwords. Oxford, UK: Oxfam GB Practical Action Publishing.

Crossley, M. L. (2000). Narrative psychology, trauma and the study of self/identity. Theory & Psychology, 10, 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354300104005.

Downing, N. E., & Roush, K. L. (1985). From passive acceptance to active commitment: A model of feminist identity development for women. The Counseling Psychologist, 13(4), 695–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000085134013.

Dutt, A. (2017). Civic participation, prefigurative politics, and feminist solidarity in rural Nicaragua. In S. Grabe (Ed.), Women’s human rights: A social psychological perspective on resistance, liberation, and justice (pp. 151–178). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dutt, A. (2018). Feminist organizing in rural Nicaragua: Assessing a psycho-social process to promote empowered solidarity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61, 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12247.

Dutt, A., & Grabe, S. (2014). Lifetime activism, marginality, and psychology: Narratives of lifelong feminist activists committed to social change. Qualitative Psychology, 2, 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000010.

Dutt, A., & Grabe, S. (2017). Gender ideology and social transformation: Using mixed methods to explore the role of deideologization in the promotion of women's human rights in Tanzania. Sex Roles, 77, 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0729-4.

Dutt, A., & Kohfeldt, D. (2018). Towards a liberatory ethics of care framework for organizing social change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 6(2), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v6i2.909.

Dutt, A., Grabe, S., & Castro, M. (2016). Exploring links between women's business ownership and empowerment among Maasai women in Tanzania. Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy, 16, 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12091.

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782.

Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalizing data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology and Health, 25, 1229–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015.

Frederick, J. K., & Stewart, A. J. (2018). “I became a lioness”: Pathways to feminist identity among women’s movement activists. Psychology of Women Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318771326.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.