Abstract

Social media have become primary forms of social communication and means to maintain social connections among young adult women. Although social connectedness generally has a positive impact on psychological well-being, frequent social media use has been associated with poorer psychological well-being. Individual differences may be due to whether women derive their self-worth from feedback on social media. The associations between reasons for social media use, whether self-worth was dependent on social media feedback, and four aspects of psychological well-being (including stress, depressive symptoms, resilience, and self-kindness) were assessed among 164 U.S. undergraduate women who completed an online questionnaire. Results indicated that having one’s self-worth dependent on social media feedback was associated with using social media for status-seeking. Women whose self-worth was dependent on social media feedback reported lower levels of resilience and self-kindness and higher levels of stress and depressive symptoms. Additionally, women whose self-worth was highly dependent on social media feedback and who were seeking social status in their online interactions reported higher levels of stress. The present findings suggest that women whose self-worth is dependent on social media feedback are at higher risk for poorer psychological well-being, which has implications for practice and policy regarding women’s mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social media use in the United States has emerged as one of the most common activities engaging the public today. Researchers have estimated that 69% of all Americans use social media and that the most common users are women and young adults (Pew Research Center 2018). Demographics show that 88% of adults between ages 18 and 39 use at least one social media site and 73% of women use at least one social media site compared to men at 65% (Pew Research Center 2018). Women are also more likely to use social media to build and maintain connections (Barker 2009).

Due to the increase in variety and accessibility of social media over the last few years, sharing information and maintaining social relationships via social media websites has become a way to manage one’s lifestyle and identity (Livingstone 2008). Social media provides individuals with an easily accessible means of communicating with others in their social networks. Young adult women tend to use social media, such as Facebook [for social networking] and Instagram [for photo sharing], more than men (Duggan 2015), and as such, some women may be vulnerable to feedback that they receive online from others in their social networks. Furthermore, examining social media use provides an avenue for understanding how gendered values and norms shape women’s well-being. On average, college women report higher collective self-esteem among their online social networks and are more likely to use online social networks to communicate with their peers (Barker 2009).

However, young adult women face pressure to present their bodies in objectified images that emphasize the performativity of their femininity, with significant impact on women’s mental health (Moradi and Huang 2008) as well as health-related behaviors, such as eating habits, exercise, and smoking behavior (Harrell et al. 2006; Melbye et al. 2007; Tylka and Sabik 2010). Young adult women who endorse the ideal body type report engaging in social comparison after viewing social media (Lewallen and Behm-Morawitz 2016), and viewing inspirational fitness images was associated with a decrease in state body satisfaction and increased negative mood among young women (Prichard et al. 2018). Further, upward appearance comparisons on social media were associated with worse appearance satisfaction and mood among college-age women (Fardouly et al. 2017). The constellation of pressures, messages, and images online shape women’s self-concept and self-perceptions, and they have consequences for women’s health behaviors and psychological well-being.

Although social media use has been linked to psychological well-being, the findings have been equivocal. For example, social media use has been associated with increased social capital and engagement among college students (Valenzuela et al. 2009), and communicating with others online has been associated with a decrease in depression and loneliness as well as an increase in self-esteem and social support among this population (Shaw and Gant 2004). However, frequent social media use has also been associated with higher stress and depression among college-age adults (Brooks 2015; Lin et al. 2016), and more information is needed about what individual factors may account for differences in this association. One key factor that my account for these differences is whether individuals feel that their self-worth depends on the feedback they receive on social media. This factor may account, in part, for differences in reasons for social media use, as well as psychological well-being as a result of social media use. The present paper is the first known to examine whether self-worth is dependent on social media feedback and if this dimension of self-worth is associated with psychological well-being.

Contingencies of Self-Worth

The concept of contingencies of self-worth posits that people base their self-esteem on various aspects of life, such as feeling attractive, loved, competent, powerful, and virtuous (Crocker et al. 2003). According to Crocker and colleagues (Crocker et al. 2003), individuals’ self-esteem may be threatened by a setback or failure in a particular domain on which their self-worth is dependent. Self-esteem is a term generally used to describe a person’s self-worth (Galanakis et al. 2016), and thus the terms self-esteem and self-worth are often used interchangeably. A considerable body of work has explored contingencies of self-worth across various domains and populations (Crocker and Knight 2005; Sanchez and Crocker 2005), however little attention has been given to self-worth in relation to social media use and feedback. One study found that among college-aged adults, individuals who felt their self-worth was tied to public-based contingencies (e.g., approval, appearance, and competition) shared more photos online, and this association was stronger for women than for men (Stefanone et al. 2011). In addition, women in their study spent more time managing their online profiles. Additionally, private contingencies of self-worth (e.g., family, virtue, and God’s love) were associated with spending less time online, although those higher in these contingencies were also more likely to share photos online (Stefanone et al. 2011).

Although contingencies of self-worth have been associated with social media use, previous work has examined contingencies in other domains (e.g., appearance, approval, virtue) and did not examine whether social media itself as a domain in which self-worth may be contingent. To address this gap, we propose that self-worth may be dependent on the feedback that an individual receives on social media. Given how ubiquitous social media use has become in the United States, along with the importance of forming and maintaining social relationships, it is likely that many people derive some of their feelings of worth from the feedback they receive through their online social interactions. This may, in part, account for the mixed findings regarding self-esteem and social media use in previous studies.

Previous research has found that high collective self-esteem was associated with using social networks to communicate with friends, and that this was more common among women (Barker 2009). However, individuals who feel disconnected from their peer group were more likely to turn to social network interactions for social compensation and to seek gratification from their social group (Barker 2009). In a study of adolescents, researchers found that receiving positive feedback on one’s online profile was associated with increased self-esteem and well-being (Valkenburg et al. 2006). Although positive feedback online may boost self-perceptions, neutral or negative feedback may have a damaging effect. For example, one study found that college students with lower self-esteem who use social media as a venue for self-disclosure are disappointed when they do not receive positive feedback (Brooks 2015). This may be particularly relevant for young women because pressure to maintain social connections and to spend time managing online identity is high among this population. If a woman’s self-worth is highly contingent on the feedback she receives on social media, she may be more likely to experience poor psychological well-being if the feedback she receives is not satisfying.

Social Media and Self-Worth

Social media are a means for individuals to connect with others and to seek out social support and information. In particular, social media have been particularly important for young adults to establish and maintain relationships with peers (Ellison et al. 2014). Individuals rely on social connections and support because developing a sense of belonging impacts self-esteem, emotional well-being, self-efficacy, and self-worth (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Nadkarni and Hofmann 2012). Social media users have more social capital, including more acquaintances and interactions, as compared to individuals who do not use social media (Steinfield et al. 2008), and it is generally accepted that greater interpersonal activity may account for an increase in well-being (Pittman and Reich 2016).

However, not all social interactions online produce positive outcomes. For example, studies have found that frequent social media use may be associated with lower subjective well-being and increased depression (Kross et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2016). For young adults, a focus on strategic self-presentation behaviors online, such as posting photos and status updates, have been associated with negative aspects of personality, such as lower conscientiousness and higher neuroticism (Seidman 2013). Further, narcissism has been associated with young adults reporting that they believe others are interested in their online post as well as a desire to share this information online (Bergman et al. 2011). This discrepancy between the positive effects of a supportive social network and the negative aspects that may arise when cultivating online relationships raises a question about what accounts for whether an individual experiences positive or negative effects of using social media. One factor may be the extent to which a person bases their feelings of self-worth on the feedback that they receive—or fail to receive—when using social media.

The extent to which self-worth is dependent on social media feedback is likely linked to the reasons women are primarily using social media. Researchers have documented a variety of reasons that individuals use social media, and one approach, the uses and gratifications model, is a framework for examining media use (Sundar and Limperos 2013). This approach assumes that social media users are choosing what media to use and how to use it based on their specific needs (Pittman and Reich 2016). In particular, Park et al. (2009) identified four primary reasons that college students use social media: socializing, entertainment, status-seeking, and information. We expect that having self-worth contingent on social media feedback may be associated with some, but not all, of the reasons for social media use. In particular, we expect that women whose self-worth is contingent on social media feedback will be more likely to use social media for socializing and for status-seeking because these aspects of social media use are associated with feedback from peers. In addition, we expect that women who are seeking status through their posts on social media and whose self-worth is dependent on this feedback will be most vulnerable to poor psychological well-being, because seeking status may heighten vulnerability to feedback.

Psychological Well-Being

The present study focuses on key indicators of psychological well-being that may impact social media users and are frequently associated with contingencies of self-worth. First, not achieving in an area contingent for self-worth may result in greater stress and depressive symptoms. For example, feeling that one’s self-worth was dependent on external factors (e.g., approval from others, appearance, competition, and academics) have been associated with an increase in depressive symptoms among college students (Sargent et al. 2006). Further, low self-esteem, an indicator of self-worth, has been associated with greater stress (Galanakis et al. 2016) as well as seeking external contingencies of self-worth (Crocker 2002; Crocker and Knight 2005). Because we posit that social media is an external domain in which some individuals may seek to increase their self esteem, social media use may contribute to experiencing stress and depression.

Researchers have pointed out the paradox that social media use should be associated with an increase in psychological well-being due to increased connectivity, yet feelings of loneliness persist among college students for whom social media use is high (Pittman and Reich 2016). This pattern has been confirmed by studies that demonstrate that using the Internet to communicate with friends and family was associated with lower levels of depression, although the effect was small and this study did not focus specifically on social media use or feedback (Bessière et al. 2010). In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that frequent social media use may be associated with lower psychological well-being and increased depressive symptoms among young adults (Chou and Edge 2012; Kross et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2016). In addition, social media use has been positively associated with higher levels of stress related to technology (Brooks 2015). This higher level of stress has, in turn, led to lower happiness (Brooks 2015). However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether stress and depressive symptoms are associated with whether self-worth is contingent on social media feedback. We argue that having self-worth linked to this particular type of feedback may increase feelings of stress and depressive symptoms.

In addition to stress and depression, key positive factors have emerged as complementary yet distinct aspects of psychological well-being that are associated with contingencies of self-worth. In particular, resilience, which is the ability to “bounce back” from stress (Smith et al. 2008), and self-kindness, an aspect of self-compassion which encompasses self-directed emotional responses to challenges and failures (Neff 2016), may be protective factors that indicate that an individual is less likely to have her self-worth contingent on social media. Self-kindness is particularly relevant to feelings of self-worth because it refers to the tendency to be understanding with ourselves and to treat ourselves with kindness rather than with critical or judgmental evaluation (Neff 2011). Importantly, Neff (2011) points out that this differs from self-esteem, which is an evaluation of our worthiness as a person and reflects our perceived competence in certain domains. Neff (2011) notes that what is problematic is what people feel they need to do or achieve to maintain high self esteem, as per achieving in external contingencies of self-worth (Crocker and Park 2004). Self-kindness is not about achieving high self-esteem; rather, it is about accepting the fact that we are imperfect and not engaging in self-criticism. Thus, practicing self-kindness may lessen the impact of not achieving in areas contingent to self-worth. Indeed, research has demonstrated the positive effects of self-compassion on body image and mood (Slater et al. 2017), and it is likely this extends to other aspects of self-worth.

Resilience has also been associated with better self-esteem and psychological well-being. Researchers have found that resilience buffers against the development of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety (Sheerin et al. 2018), and adolescents with higher resilience also report greater self-esteem (Dumont and Provost 1999). In addition, self-compassion has been associated with increased emotional resilience (Neff 2011). Studies linking resilience to domains of contingent self-worth, such as academic achievement, have shown that people with high self esteem show more resilience than those with low self esteem when facing a failure in that domain (Park et al. 2007). The ability to bounce back from disappointment in an area where self-worth is contingent may differentiate between those who experience better or worse psychological well-being after a perceived failure. With regard to social media feedback, individuals who report that their self-worth is not dependent on social media feedback may be more resilient, may be less likely to report stress and depressive symptoms, and may be more likely to demonstrate self-kindness. In sum, resilient and self-compassionate individuals may be less invested in the feedback they receive through social media because this feedback might have less impact on their sense of self and psychological well-being.

The Current Study

Receiving positive feedback may boost self-esteem, particularly in domains that a person values or views as contingent to his or her self-worth (Crocker and Knight 2005). Research shows contingencies of self-worth determine people’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors (Crocker and Knight 2005). However, little is known about whether people feel that their self-worth is contingent on social media feedback or how this affects psychological well-being. To examine this possibility, we focus on assessing (a) whether there is an association between self-worth being highly contingent on social media feedback and using social media to seek social status and to socialize with others and (b) whether there is an association between having self-worth contingent on social media feedback and greater psychological distress, including higher depressive symptoms, higher self-reported stress, lower resilience, and lower self-kindness. In addition, we examine whether the association between having self-worth contingent on social media feedback and indicators of psychological well-being is moderated by using social media for seeking status.

We propose three hypotheses. (a) Having one’s self-worth linked to social media will be associated with why women use social media. In particular, we expect this will be associated with greater socializing and status-seeking (Hypothesis 1). (b) Women whose self-worth is contingent on social media feedback will have poorer psychological well-being, including higher depressive symptoms, higher self-reported stress, lower resilience, and lower self-kindness (Hypothesis 2). (c) The association between having self-worth contingent on social media feedback and indicators of psychological well-being (including depressive symptoms, stress, resilience, and self-kindness) will be moderated by using social media for seeking status (Hypothesis 3). That is, we expect that women whose self-worth is dependent on social media feedback who are also seeking status in their online interactions will report the poorer psychological well-being.

Method

Participants

Participants included 164 college-aged women recruited online in the United States who completed all of the questionnaires in the current study. 4 participants were excluded for incomplete responding. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 33 years-old, with an average age of 20.50 (SD = 2.67). A majority of participants identified as White (131, 79.9%), and small percentages identified as Hispanic or Latina (8, 4.9%), African American (5, 3.0%), Asian/Pacific Islander (6, 3.7%), or multiracial (9, 5.5%). A few participants (3, 1.8%) chose not to identify their ethnic group or reported “other.” A majority reported living in a suburban environment (112, 68.3%), with fewer participants living in an urban setting (33, 20.1%) or a rural setting (19, 11.6%). With regard to social media profiles, 26 (15.9%) reported that they keep all profiles public, 84 (51.2%) reported keeping all profiles private, and 54 (32.9%) reported a combination of private and public social media profiles.

Procedure and Measures

Participants were recruited through an online advertisement on social media and through announcements in introductory level courses at a mid-size U.S. public university on the east coast. Potential participants were directed to an online survey that was open for a 4-month period via a Survey Monkey URL link. The series of questionnaires took approximately 30 min to complete. All participants were given the option to submit their email address separately from the data collection to enter a drawing for a $10 (USD) amazon gift card, and ten participants were randomly selected to receive the incentive. Study materials and procedure were approved by the University IRB prior to data collection, and participants were treated according to the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association. Participants who visited the online survey first read a description of the study and agreed to participate by providing informed consent. Next, participants provided basic demographic information and then were presented with the following measures in the order they are listed here.

Self-Worth Dependent on Social Media

We developed the Self-Worth Dependent on Social Media (SWDSM) Scale to examine if an individual places value on the feedback received by their friends/followers on social media. We developed six questions assessing social media feedback by modifying questions from a widely used measure of contingencies of self-worth, which have reported alphas ranging from .82–.96 (Crocker et al. 2003). Questions from the social media feedback subscale include: “My self-esteem depends on how others respond to my social media posts,” “My self-esteem depends on how attractive others think pictures of myself are on social media,” and “My sense of self-worth suffers whenever I don’t receive positive feedback on social media.” (All items are available in the online supplement). Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with the mid-point being a neutral response. Items were averaged, with higher scores reflecting self-worth being more contingent on social media feedback. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .88. Data were also collected on the original measure, and analysis showed that having self-worth dependent on social media was positively correlated with a related subscale from the original measure assessing whether one’s self-worth is dependent on approval from others (r = .66, p < .001).

Frequency of Social Media Use

In order to assess how frequently social media was used, 13 items that measure behavior on and frequency of use on social media were assessed. Questions were developed by the research team and reflected on typical social media use on a daily basis. Example items include: “How often do you post a status on social media during an average week?” “How often do you post a status on social media during an average day?” and “How often do you comment on other individuals’ posts during an average day?” (All items are available in the online supplement.) The items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with higher scores indicating greater social media use. Items were averaged to create a scale score, and Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .90. On average, participants reported a moderate amount of social media use, and all participants reported engaging in some social media use (M = 3.10, SD = .60, range = 1.77–5.00).

Reasons for Social Media Use

The four-factor Social Media Uses and Gratifications scale (Park et al. 2009) measures the primary needs for participating on social networks. The four factors that the scale assesses reflect primary reasons people use social media, including socializing (5 items), entertainment (3 items), self-status-seeking (3 items), and information (3 items). Because two items (11 and 14) had a low item-total correlation (rs < .25), these were removed from analyses so that self-status-seeking and information each contained two items. The items are rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), and items are averaged to create a mean score for each participant for each subscale. Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for subscales in the present study ranged from .67 to .86, which indicates reliability is slightly lower than (for the socializing subscale) to comparable (for the remaining subscales) to the range reported by the scale developers, which ranged from .81–.87 (Park et al. 2009).

Perceived Stress Scale

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen and Williamson 1988) is a widely used psychological instrument to measure the perception of stress. The 10-item questionnaire asks participants to report the degree to which situations in one’s life are viewed as stressful during the last month. Example items include: “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?” and “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” The 10-items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) and are averaged to create a mean score, with higher scores reflecting greater overall stress. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

The Brief Resilience Scale

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (Smith et al. 2008) is designed to measure an individual’s ability to bounce back or recover from stress. The six-item measure instructs participants to indicate the extent they agree with the statements provided on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items include: “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” and “It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event.” Mean scores were calculated for study participants, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .92. Smith et al. (2008) reported alphas ranging from .84–.87 among samples of undergraduate students.

Depressive Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CES-D-R-10) (Andresen et al. 2013) is a ten-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. Items reflect how participants felt over the past week and are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (all of the time). Example items include: “I felt depressed” and “I thought my life had been a failure.” Items were averaged, with higher scores reflecting greater depressive symptoms. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .82, which is comparable to those reported by Andresen et al. (2013), with alphas ranging from .86–.88.

Self-Kindness

The self-kindness subscale of the Self-Compassion Scale (Neff 2003) was used to assess self-kindness. This subscale contains five items, such as “When I’m going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need” and “I’m tolerant of my own flaws and inadequacies.” Items were rated on a scale of 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Mean scores were calculated for study participants, with higher scores indicating greater self-kindness. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .85, which is similar to that reported by Neff (2003, α = .78).

Results

Data were screened for instances of participants “straight-lining” (giving the same answer throughout an individual questionnaire). No participants gave straight-line answers on any questionnaires that included reverse-scored items, indicating that appropriate attention was given to the questions. Fully 168 participants finished the survey, and of these, 164 had complete data on all study measures. An analysis of Little’s MCAR test indicated that missing data could be assumed to be randomly distributed, χ2(10) = 11.03, p = .355, thus all subsequent analyses were performed on participants with complete data. A post-hoc power analysis indicated that, with the five predictors in our model and a statistical power level of .80 and an alpha of .05, the sample size would be sufficient to detect an effect of approximately .08, which is considered to be between a medium and a small effect (Cohen 1988).

Correlations between reasons for social media use, whether self-worth was dependent on social media feedback, and aspects of psychological well-being including resilience, self-kindness, stress, and depressive symptoms are shown in Table 1. In addition, frequency of social media use and age were included to examine whether these were correlated with the study variables. Hypothesis 1 was partially supported. Having one’s self-worth depend on social media feedback was associated with using social media for status-seeking. However, having self-worth depend on social media feedback was not associated with other reasons for social media use, including seeking information, entertainment, or socializing. Because frequency of social media use and age were significantly associated with a number of study variables, subsequent analyses controlled for age and frequency of social media use. Correlations between having self-worth depend on social media feedback and indicators of psychological well-being showed support for Hypothesis 2. Women whose self-worth was dependent on social media feedback reported lower levels of resilience and self-kindness as well as higher rates of stress and depressive symptoms.

We ran four separate regression analyses modeling for moderating effects as described by Hayes (2013) using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23, with each focused on one of our four outcome variables: resilience, self-kindness, depressive symptoms, and stress. Continuous predictor variables were centered. The predictor (self-worth dependent on social media) and proposed moderator variable (status-seeking) were multiplied to create the interaction term. Graphs of significant interactions were plotted using mean values as well as estimates one standard deviation above and below the mean to probe significant interaction effects (Aiken and West 1991). The regression analyses showed mixed support for Hypothesis 3 (see Table 2).

The first regression analysis showed that having higher levels of self-worth dependent on social media feedback, as well as lower social media use, were associated with lower levels of resilience (see Table 2a). However status-seeking was not a significant predictor of resilience, nor was the interaction between having self-worth dependent on social media feedback and status-seeking. The second regression also found a main effect, with higher self-worth dependent on social media as a significant predictor of lower self-kindness (see Table 2b), but no other predictors or interactions had a significant association with the outcome variable. The third regression analysis showed that having higher self-worth dependent on social media feedback was a significant predictor of greater depressive symptoms, but no other significant predictors or interactions emerged from this analysis (see Table 2c).

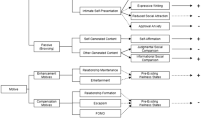

The fourth regression supported our hypothesis (see Table 2d). Both having self-worth contingent on social media feedback and status-seeking were significant predictors of stress, as was the interaction between these two variables. To explore the interaction, we conducted simple slopes analyses (see Fig. 1). We found that for women whose self-worth was less dependent on social media feedback (SWDSM Average and SWDSM Low), lower status-seeking was associated with lower levels of reported stress. The slope of the line for women with average dependence of self-worth on social media was significantly different from zero (p < .001, 95% CI [.08, .26]), and the same was true for women with low dependence of self-worth on social media (p < .001, 95% CI [.20, .43]). In contrast, for women with higher levels of having their self-worth dependent on social media feedback, there was not a significant relationship between their levels of status-seeking and stress (p = .731, 95% CI [−.11, .16]). In sum then, only for women who highly depend on social media feedback for their self-worth do we find high levels of reported stress independent of their status-seeking motives. For women with lower and average dependency on social media feedback for their self-worth, their status-seeking motives matter such that higher levels of status-seeking are associated with higher levels of stress.

The interaction between using social media for status-seeking and having self-worth dependent on social media feedback (SWDSM) on stress. For both predictor variables, low is graphed at −1 SD; average, at the mean; and high, at +1 SD. The slopes for both black lines (low and average SWDSM) are significant (p < .05) whereas the grey slope (high SWDSM) is not. Thus higher status-seeking is associated with greater stress, but only for women with lower and average levels of dependency on social media feedback for their self-worth

Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the effects of social media feedback on self-worth among women actively using social networking sites. Using the contingency of self-worth (CSW) model (Crocker et al. 2003), we developed a domain specifically related to feelings of self-worth and social media, which we used to determine the degree to which individuals place value on social media profiles and feedback. As we hypothesized, our results indicated that having one’s self-worth depend on social media feedback was associated with using social media for status-seeking. Furthermore, our study demonstrated significant associations between whether an individual linked their self-worth to the social media feedback they receive and all aspects of psychological well-being assessed in our study, including lower levels of resilience and self-kindness and higher rates of stress and depressive symptoms.

As we expected, having self-worth depend on social media feedback was associated with using social media for status-seeking. However, having self-worth depend on social media feedback was not associated with other reasons for social media use, including seeking information, entertainment, or socializing. This finding reflects that reasons for social media use are varied (Whiting and Williams 2013) and do not uniformly relate to mental health outcomes (Seabrook et al. 2016). Additionally, this finding builds on prior research demonstrating that among college students, individuals with low self esteem post more self-promotional content on social network sites (Mehdizadeh 2010). Understanding in more detail how and why individuals use social media will help clarify the mixed findings regarding the association between social media use and well-being.

Importantly, whether individuals linked their self-worth to the social media feedback they receive was associated with all aspects of psychological well-being assessed in our study. Women whose self-worth was dependent on social media feedback reported lower levels of resilience and self-kindness and higher rates of stress and depressive symptoms. These findings reflect broader patterns in the literature showing that low self-esteem has been associated with poorer mental health and that, for some people, using social media is associated with greater depressive symptoms (Pantic 2014). Specifically, negative interactions online and social comparison on social media sites have been associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety (Seabrook et al. 2016). Not all individuals are negatively affected by social media use, and it is becoming clear that how and why people engage with social media is an important determinant of the mental health outcomes assessed. Having one’s self-worth dependent in a particular domain may come at a high cost because people react to threats in that domain in ways that can be detrimental to mental health (Crocker and Park 2004). In particular, having self-worth dependent on social media feedback may make individuals more vulnerable to engaging in social comparison, which may negatively impact mental health, and further research in this area is needed to better characterize this association. Because there are significant individual-level differences in the outcomes associated with social media use (e.g., not all social media users experience lower self-esteem or poorer mental health), further research is warranted to investigate the reasons that individuals use social media and the impact this has on their mental health.

Both having self-worth depend on social media feedback and status-seeking were significant predictors of stress, as was the interaction between these two variables. A graph of this interaction showed that women who reported that their self-worth was dependent on social media feedback were relatively higher on stress overall, regardless of whether they were seeking status in their online interactions. However, women who demonstrated average or low self-worth dependent on social media feedback and who were less focused on status-seeking in their online interactions reported lower levels of stress. These findings mirror comparable results demonstrating the negative impact of social media use on self-worth and body image. For example, research has shown that among female adolescents, basing one’s self-worth on appearance was associated with more frequent photo-sharing on popular social media networking sites (Meier and Gray 2014). Further, because women tend to internalize media images of beauty ideals, social comparison to other people’s bodies have been shown to intensify the association between viewing idealized images and negative body image outcomes, such as self-objectification and disordered eating (Holland and Tiggemann 2016).

Practice Implications

As social media becomes part of daily life for many young adults, there are important implications for how this work can inform professionals working in the field to improve policies and tools to address these issues. According to our results, women whose self-worth is dependent on social media feedback are likely to report lower levels of resilience and self-kindness as well as higher levels of stress and depressive symptoms. Considering these findings, counselors and therapists working with women experiencing significant levels of depressive symptoms or stress who also have high frequency of social media use should incorporate an element of managing or monitoring social media use into assessment and treatment plans. Addressing directly whether women feel they are linking their self-worth to this feedback and limiting social media engagement have the potential to reduce these negative associations. Furthermore, when designing interventions to improve psychological well-being among this population, identifying individuals who use social media frequently may help, and a targeted approach focused on those who feel their self-worth is tied to social media feedback is critical.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are a number of limitations that should be taken into consideration when considering the results from the current study. First, the results from the current study are correlational, and they do not address causation between study variables. In addition, it should be noted that the socializing subscale of the social media uses and gratifications measure had a low alpha. While it is possible that having self-worth depend on social media feedback leads women to experience worse psychological well-being, it may also be that for some individuals, poor psychological well-being (e.g., higher stress and depressive symptoms; lower resilience and self-kindness) create a vulnerability toward social media feedback. As such, future research should employ both experimental methods to examine immediate responses to the effect of social media feedback on feelings of self-worth and psychological well-being as well as longitudinal designs to track how these factors may develop and interact over time. In particular, young women who are growing up using social media may be more vulnerable to online feedback, particularly bullying and peer pressure (Mishna et al. 2012; Snell and Englander 2010; Wingate et al. 2013). This type of online social interaction may lead to worse psychological well-being at critical developmental periods (Lin et al. 2016), and identifying risk factors for poor mental health related to social media use is of importance for this population.

The current study focused only on women’s experiences of social media use, feedback, and well-being, and men may have different experiences. It is critical to examine gender differences in these patterns because men and women may have different expectations due to stereotypes about gender roles. In addition, other socio-demographic factors (e.g., socio-economic status, race/ethnicity, and age) may lead to different associations between the constructs in the current study. The sample represented in our research is fairly homogeneous with regard to these demographic characteristics, and future research should explore whether similar patterns hold for other groups.

Given the often visual and self-focused nature of the content shared on social media, further research in this area should consider aspects of body image and self-objectification as other areas that can be affected by social media use and the feedback received (Grogan et al. 2017; Prieler and Choi 2014; Ramsey and Horan 2017). Self-focused content in particular may leave women whose self-worth is linked to social media feedback feeling more negatively about themselves and at higher risk for poor psychological well-being. Problematic social media use has been associated with lower self-esteem as well as poorer body image and eating disorder symptoms (Santarossa and Woodruff 2017). Future research linking having self-worth contingent on social media and body image processes and outcomes is warranted to further probe the nature of contingent self-worth and women’s body image. Additional research in this area will add to the ways in which we address components of psychological and physiological health of women in the future.

Conclusion

Social media use is common among U.S. college-age women, and feeling that one’s self-worth is tied to the feedback received online is a significant predictor of reasons for social media use and for psychological well-being. Women whose self-concept is vulnerable to feedback face challenges in terms of managing stress, viewing oneself in a positive light, and experiencing depressive symptoms. A critical examination of how women engage with social media is needed to address mental health among this population. As new forms of social media continue to be developed and used with great regularity, it is important that we understand how the feedback received affects well-being so that we can effectively interrupt negative patterns and intervene when appropriate to reduce negative outcomes associated with this behavior.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Andresen, E. M., Byers, K., Friary, J., Kosloski, K., & Montgomery, R. (2013). Performance of the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for caregiving research. SAGE Open Medicine, 1, 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312113514576.

Barker, V. (2009). Older adolescents' motivations for social network site use: The influence of gender, group identity, and collective self-esteem. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0228.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.117.3.497.

Bergman, S. M., Fearrington, M. E., Davenport, S. W., & Bergman, J. Z. (2011). Millennials, narcissism, and social networking: What narcissists do on social networking sites and why. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.022.

Bessière, K., Pressman, S., Kiesler, S., & Kraut, R. (2010). Effects of internet use on health and depression: A longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(1), e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1149.

Brooks, S. (2015). Does personal social media usage affect efficiency and well-being? Computers in Human Behavior, 46, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.053.

Chou, H.-T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others' lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0324.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. The social psychology of health (pp. 31–67). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Crocker, J. (2002). The costs of seeking self–esteem. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00279.

Crocker, J., & Knight, K. M. (2005). Contingencies of self-worth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 200–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00364.x.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392.

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., & Bouvrette, A. (2003). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 894–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894.

Duggan, M. (2015). Mobile messaging and social media. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/mobile-messaging-and-social-media-2015/. Accessed 10 Oct 2018.

Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(3), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021637011732.

Ellison, N. B., Vitak, J., Gray, R., & Lampe, C. (2014). Cultivating social resources on social network sites: Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 855–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12078.

Fardouly, J., Pinkus, R. T., & Vartanian, L. R. (2017). The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women’s everyday lives. Body Image, 20, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002.

Galanakis, M. J., Palaiologou, A., Patsi, G., Velegraki, I.-M., & Darviri, C. (2016). A literature review on the connection between stress and self-esteem. Psychology, 7(05), 687–694. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2016.75071.

Grogan, S., Rothery, L., Cole, J., & Hall, M. (2017). Posting selfies and body image in young adult women: The selfie paradox. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(1), 15–36.

Harrell, Z. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Pomerleau, C. S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2006). The role of trait self-objectification in smoking among college women. Sex Roles, 54(11–12), 735–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9041-z.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008.

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., … Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One, 8(8), e69841. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069841

Lewallen, J., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2016). Pinterest or thinterest?: Social comparison and body image on social media. Social Media+ Society, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116640559.

Lin, L., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., … Primack, B. A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 323-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.01.016

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers' use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society, 10(3), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808089415.

Mehdizadeh, S. (2010). Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0257.

Meier, E. P., & Gray, J. (2014). Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(4), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0305.

Melbye, L., Tenenbaum, G., & Eklund, R. (2007). Self-objectification and exercise behaviors: The mediating role of social physique anxiety. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 12(3–4), 196–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9861.2008.00021.x.

Mishna, F., Khoury-Kassabri, M., Gadalla, T., & Daciuk, J. (2012). Risk factors for involvement in cyber bullying: Victims, bullies and bully–victims. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.032.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y.-P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Nadkarni, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Why do people use Facebook? Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x.

Neff, K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3.

Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(10), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0070.

Park, L. E., Crocker, J., & Kiefer, A. K. (2007). Contingencies of self-worth, academic failure, and goal pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(11), 1503–1517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207305538.

Park, N., Kee, K. F., & Valenzuela, S. (2009). Being immersed in social networking environment: Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 729–733. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0003.

Pew Research Center. (2018). Social media use in 2018. Retrieved from Pew Research Center: http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/. Accessed 28 Nov 2018.

Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084.

Prichard, I., McLachlan, A. C., Lavis, T., & Tiggemann, M. (2018). The impact of different forms of# fitspiration imagery on body image, mood, and self-objectification among young women. Sex Roles, 78(11–12), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0830-3.

Prieler, M., & Choi, J. (2014). Broadening the scope of social media effect research on body image concerns. Sex Roles, 71(11–12), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0406-4.

Ramsey, L. R., & Horan, A. L. (2017). Picture this: Women's self-sexualization in photos on social media. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.022.

Sanchez, D. T., & Crocker, J. (2005). How investment in gender ideals affects well-being: The role of external contingencies of self-worth. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00169.x.

Santarossa, S., & Woodruff, S. J. (2017). #SocialMedia: Exploring the relationship of social networking sites on body image, self-esteem, and eating disorders. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117704407.

Sargent, J. T., Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. K. (2006). Contingencies of self–worth and depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(6), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.6.628.

Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 3(4), e50. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5842.

Seidman, G. (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 402–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.009.

Shaw, L. H., & Gant, L. M. (2004). In defense of the internet: The relationship between internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support. Internet Research, 28(3), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493102753770552.

Sheerin, C. M., Lind, M. J., Brown, E. A., Gardner, C. O., Kendler, K. S., & Amstadter, A. B. (2018). The impact of resilience and subsequent stressful life events on MDD and GAD. Depression and Anxiety, 35(2), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22700.

Slater, A., Varsani, N., & Diedrichs, P. C. (2017). # fitspo or# loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image, 22, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.06.004.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.

Snell, P. A., & Englander, E. (2010). Cyberbullying victimization and behaviors among girls: Applying research findings in the field. Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 510–514. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2010.510.514.

Stefanone, M. A., Lackaff, D., & Rosen, D. (2011). Contingencies of self-worth and social-networking-site behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(1–2), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0049.

Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B., & Lampe, C. (2008). Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.07.002.

Sundar, S. S., & Limperos, A. M. (2013). Uses and grats 2.0: New gratifications for new media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(4), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827.

Tylka, T. L., & Sabik, N. J. (2010). Integrating social comparison theory and self-esteem within objectification theory to predict women’s disordered eating. Sex Roles, 63(1–2), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9785-3.

Valenzuela, S., Park, N., & Kee, K. F. (2009). Is there social capital in a social network site?: Facebook use and college students' life satisfaction, trust, and participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(4), 875–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01474.x.

Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J., & Schouten, A. (2006). Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents' well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584.

Whiting, A., & Williams, D. (2013). Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qualitative Market Research, 16(4), 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2013-0041.

Wingate, V. S., Minney, J. A., & Guadagno, R. E. (2013). Sticks and stones may break your bones, but words will always hurt you: A review of cyberbullying. Social Influence, 8(2–3), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2012.730491.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

We followed APA standards on ethical treatment of participants and the study design was reviewed and approved by the university’s institutional review board (IRB).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sabik, N.J., Falat, J. & Magagnos, J. When Self-Worth Depends on Social Media Feedback: Associations with Psychological Well-Being. Sex Roles 82, 411–421 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01062-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01062-8