Abstract

Traditional gender stereotypes encompass (typically masculine) agency, comprising task-related competence, and (typically feminine) communion or warmth. Both agency and communion are important for successful performance in many jobs. Stereotypes of gay men include the perception that they are less gender-typed than their heterosexual counterparts are (i.e., more gay-stereotypical and less masculine). Using a German sample, Experiment 1 (n = 273) tested whether gay men at the same time appear higher in communion, but lower in agency than heterosexual men and whether a trade-off in hireability impressions results between both groups if jobs require both agency and communion. We measured participants’ willingness to work together with applicants, in addition to hireability, as dependent variables, and we assessed as mediators perceived masculinity, how gay-stereotypical male targets were judged, as well as perceived communion and agency. Findings showed that gay men appeared more gay-stereotypical, less masculine, and more communal than heterosexual men, but no difference in agency was observed. The direct effects of sexual orientation on willingness to engage in work-related contact and on hireability were not significant. Instead, both positive and negative indirect effects of sexual orientation on hireability/contact were found. Experiment 2 (n = 32) replicated the findings pertaining to agency, communion, and masculinity and demonstrated that a gay applicant appeared better suited for traditionally feminine jobs, whereas a heterosexual applicant appeared better suited for traditionally masculine jobs. We discuss who is discriminated under which conditions, based on gender-related stereotypes, when men’s sexual orientation is revealed in work contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In work contexts, people form impressions of individuals who are members of different social groups. For example, qualifications of different applicants, some of them being men and some women, need to be assessed. If people’s sexual orientations are known, it may also happen that, for example, qualifications of a gay and a heterosexual man are compared when deciding who is best suited for a given job. Much research in social psychology has demonstrated that as a rule, it is hard to ignore group membership when judging individuals, even though people may try to arrive at impressions of individuals that are unbiased by social-group membership (for a review, see Steffens and Viladot 2015). In other words, effects of group stereotypes are hard to avoid.

Gender bias in work-related impression formation is a well-established phenomenon: All else being equal, women have appeared better-suited for traditionally feminine jobs and men for traditionally masculine jobs (Davison and Burke 2000). Similar to ethnicity (e.g., Galinsky et al. 2013), sexual orientation intersects with gender: Heterosexual men are perceived to be more gender-typed than gay men are. Thus, if identical information is presented about a gay and a heterosexual man, it is possible that people still arrive at different gender-related impressions of them (e.g., Whom do they consider more team-oriented? Who would be the better car mechanic?). The aim of the present analogue experiments, carried out in Germany, was to test how far information on a man’s sexual orientation leads to differences in job-related impressions, based on the “big two” dimensions in social judgment: (typically masculine) agency and (typically feminine) communion.

Agency, Communion, and Lack of Fit

The stereotype content model postulates that warmth and competence are the central dimensions in social judgment (Fiske et al. 2002). In other words, it posits that it is informative to regard each stereotyped group in terms of the warmth and competence attributed to them (which are then associated with specific emotions, see Cuddy et al. 2007). Warmth corresponds to communion or expressiveness and can be described as a concern for other people and for one’s social relations whereas competence is one central aspect of the broader concept agency (Eagly 1987). Agency can be defined as instrumentality or as a concern for one’s own interests, comprising assertiveness, competitiveness, and dominance in addition to job-related competence. In all studies reported in the following, we measured either competence or the competence aspect of agency (e.g., not dominance); henceforth, we refer to agency throughout.

Together, communion and agency have been described as the “big two” in social judgment (Abele and Bruckmüller 2011, but also see Koch et al. 2016). These dimensions have particularly been applied to women and men: According to traditional gender stereotypes, women are higher in communion than men whereas men are higher in agency than women (Diekman and Eagly 2000). In fact, the dimensions have been referred to as masculinity and femininity, and the items “masculine” and “feminine” have previously been included in respective instruments such as the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI, Bem 1974). However, factor analyses have shown that the items masculinity/femininity loaded on a third, separate factor (with opposite loadings) than the other items in the BSRI (for a review, see Choi and Fuqua 2003). This finding has also been observed in Germany where the present research was conducted (Niedlich et al. 2015). Choi and Fuqua (2003) concluded that the items masculinity/femininity are more closely related to biological than to psychological gender differences. We follow Kachel and colleagues (Kachel et al. 2016) in conceiving of masculinity as a “core concept” from which gender stereotypical traits, gender roles, occupations, physical characteristics (Deaux and Lewis 1984), and the like are inferred, and we measure masculinity and agency separately in the studies we report here.

How do group stereotypes pertaining to communion and agency influence judgments of individuals? When people form impressions of individuals, for example when reading resumes or during job interviews, information provided on those individuals is combined with group stereotypes (Fiske and Neuberg 1990). In other words, the stereotype of the group may affect judgments about an individual group member. In particular, this should be the case if the presented information is ambiguous, that is, if little information is present, if its interpretation is unclear, or if there is little time or capacity to form individual impressions (Heilman 2012). Both perceived agency and communion determine hireability judgments, particularly in gender-neutral job contexts (Rudman and Glick 1999, 2001; Steffens et al. 2009). The lack-of-fit model (Heilman 1983) as well as role congruity theory (Eagly and Karau 2002) postulate that a major criterion for personnel selection is the perceived fit of an applicant for a given position. If the perceived fit is high, successful job performance is expected. Traits attributed to women in general do not seem to fit the requirements of a traditionally masculine position. A female applicant, although she may have identical qualifications as a male applicant, would thus be less likely to be hired because she is perceived as less suitable based on the application of stereotypical knowledge.

However, group stereotypes of agency and communion are not applied to all group members alike. For example, women who were pregnant, particularly attractive, or wore feminine clothing were perceived as particularly gender-stereotypical (for a review, see Eagly and Karau 2002)—in other words, high in communion and low in agency. In contrast, several studies found that negative female stereotypes were applied to heterosexual women, but not to lesbians (Niedlich et al. 2015; Peplau and Fingerhut 2004). Similarly, high agency and low communion should not be ascribed to all men alike.

Stereotypes of Gay Men and Job-Related Discrimination

On the most general abstract level, the stereotype of gay men is that they are less masculine and more feminine than heterosexual men are (Kite and Whitley Jr 1996; but different substereotypes exist in the U.S., see Clausell and Fiske 2005). Regarding communion and agency, gay men in general are stereotyped as higher in communion, but lower in agency than heterosexual men both in Germany and in the United States (Asbrock 2010; Clausell and Fiske 2005). In other words, on this abstract level, stereotypes could be similar in both cultural contexts: Western Europe and North America. Thus, given identical, but little information about an individual gay man and a heterosexual man, the gay man may appear higher on communion, whereas the heterosexual man may appear higher on agency. On this basis, different patterns of lack-of-fit should be expected for different jobs.

Existing findings regarding job-related discrimination on the basis of men’s sexual orientation are mixed (for a review, see Steffens et al. 2016). Discrimination of gay as compared to heterosexual applicants was found in a field experiment in Canada some time ago (Adam 1981). However, because attitudes toward gay men have become more positive, both in Europe and North America, across the last decades (Kuyper et al. 2013; Smith 2011; Yang 1997), this finding could be outdated. A more recent field experiment reported no hiring bias against gay men in major U.S. cities (Bailey et al. 2013). Similarly, no discrimination against gay couples was found on the German housing market (Mazziotta et al. 2015).

Findings are still mixed if we take into account how gender-typed jobs are. A study in Belgium found no hiring bias against gay men for a traditionally masculine job (Van Hoye and Lievens 2003). However, because the selection professionals who rated the applications had received detailed information about the applicant, effects of group stereotypes could have been overshadowed by that information (see Heilman 2012). Other field experiments have shown discrimination of gay men in traditionally masculine jobs, both in Sweden and in the United States (Ahmed et al. 2013; Tilcsik 2011). Whereas field experiments have particularly high external validity, a drawback is that the mechanisms underlying judgments cannot be investigated; for example, if callback rates are higher for one applicant than for another, it remains unclear why.

To more closely investigate the processes underlying hiring discrimination, several analogue experiments have presented the same information about a fictitious job applicant, manipulating sexual orientation (Horvath and Ryan 2003; Pichler et al. 2010). All studies reported in the following were U.S.-based except that two were from Germany (Kranz et al. 2017; Niedlich and Steffens 2015) and one was from Italy (Fasoli et al. 2017). Regarding communion ratings, several studies found that gay men were rated higher than heterosexual men were (Barrantes and Eaton 2018; Niedlich and Steffens 2015), whereas another study found this pattern only for women as raters (Everly et al. 2016).

These female participants also regarded gay men as more hireable than heterosexual applicants, whereas the opposite pattern was found for male participants (Everly et al. 2016). A possible reason for this gender difference could be a confound of gender with political orientation: In another recent study, only politically conservative participants evaluated a gay applicant more negatively than the heterosexual applicant on a compound competence/hireability measure (Hoyt and Parry 2018). Looking at different jobs, a recent study demonstrated that a heterosexual applicant appeared more hireable for a traditionally masculine than a traditionally feminine job, whereas a gay applicant appeared equally suited for both types of jobs (Clarke and Arnold 2018). Several other studies found that (White) heterosexual men were considered more suitable for leadership positions than gay men (Fasoli et al. 2017; Wilson et al. 2017), but others reported no difference in hireability (Niedlich and Steffens 2015), or findings depended on the type of leadership position (Barrantes and Eaton 2018).

Findings regarding agency perceptions are also mixed (Barrantes and Eaton 2018; Niedlich and Steffens 2015). Related evidence shows that, as compared to men described as agentic, men described as communal were judged to be gay with a higher probability (Kranz et al. 2017, conceptually replicating seminal work by Deaux and Lewis 1984). And ascriptions of more communal traits to gay than heterosexual men were found only if the gay man had demonstrated communal behavior and the heterosexual man, agentic behavior—not vice versa (Kranz et al. 2017). Taken together, several studies from the United States and from different European countries converge on the finding that higher communion may be ascribed to individual gay men over heterosexual men, but findings are mixed regarding agency perceptions and hireability ratings.

The Present Research

Do different job-related impressions of two men who are introduced as either gay or heterosexual result, even if all other information presented about them is identical? The aim of the present study was to use simulated hiring decisions to test this question. On the basis of stereotypes of gay men that comprise many positive traits typical of women, such as emotional intelligence and good taste (Morrison and Bearden 2007), being creative and artistic (see Clausell and Fiske 2005), as well as fashion-savvy (Cotner and Burkley 2013), gay men should appear more communal than heterosexual men do (Asbrock 2010). This ascribed communality should be an asset for traditionally feminine jobs as well as gender-neutral jobs requiring both communion and agency. In contrast, we assume that a heterosexual male applicant appears more masculine than a gay male applicant, and based on that assumption, he is perceived as more agentic, which should be an asset for traditionally masculine jobs as well as for gender-neutral jobs. Taken together, we predict that a gay male applicant and a heterosexual male applicant will appear about equally suited for a gender-neutral job because of a trade-off in lower communion and higher agency attributed to the heterosexual as compared to the gay applicant; in contrast, the gay male applicant should appear more hireable for traditionally feminine jobs, due to higher perceived communion, and the heterosexual male applicant should appear more hireable for traditionally masculine jobs due to higher perceived agency. We conducted two experiments to test these predictions.

Experiment 1

The aim of Experiment 1 was to test how far impressions of gay versus heterosexual male applicants differ in simulated hiring decisions if a job appears to require both agency and communion. Participants read a short excerpt from a fictitious job interview either with a gay male or with a heterosexual male applicant. The interview contained questions pertaining both to agency and communion; thus both dimensions should be considered important for hireability judgments.

Hireability ratings have previously been referred to as formal discrimination. Some research on applicants’ sexual orientation has found that formal discrimination was absent, but at the same time, indicators of interpersonal discrimination were observed (Hebl et al. 2002). For example, there was less eye contact and shorter interactions with apparently gay or lesbian than with heterosexual applicants. Based on these findings, we complemented a hireability scale with a scale measuring the willingness to engage in work-related contact with an applicant. First, we argue that hireability ratings are quite abstract and general and that asking participants to think about concrete scenarios may yield more valid responses. Second, it appears easy to tick “yes” on such a hireability scale because it does not imply any personal consequences. Less abstract questions focusing on the need to interact with the applicant in the future could be better suited to indicate individual prejudice and thus the willingness to have or avoid personal contact. On this basis, we were interested in participants’ more self-relevant, concrete willingness to work together with the applicant as a colleague. For the present experiment, we developed a scale measuring willingness to engage in work-related contact. We argue that both perceived agency and perceived communion should be related to the willingness to engage in work-related contact because they are required from successful co-workers.

We argue that learning about a man’s sexual orientation activates the social category gay man versus heterosexual man, which is associated with both sexual-orientation and masculinity stereotypes (for similar reasoning regarding women, see Niedlich et al. 2015). Translated to work-related impressions, gay stereotypicality should lead to high communion ratings, and masculinity should lead to high agency ratings. Similar to what we postulated regarding work-related contact, both perceived communion and agency should be directly related to hireability judgments (Rudman and Glick 1999, 2001). Taken together, we expected serial mediations that we detail in the hypotheses.

We tested the following hypotheses: Gay men should appear more gay-stereotypical than heterosexual men (Hypothesis 1), and they should be ascribed more communion (Hypothesis 2), but less masculinity (Hypothesis 3), and less agency (Hypothesis 4). Both communion and agency should determine willingness to engage in work-related contact (Hypothesis 5) and hireability (Hypothesis 6). We then tested the following serial mediations. More gay stereotypicality (of the gay as compared to the heterosexual applicant) should result in higher perceived communion, which should be related to more willingness to engage in work-related contact. In contrast, lower masculinity ratings should be related to lower agency impressions, which should in turn be related to less willingness to engage in work-related contact. Taken together, we predicted two opposite indirect effects of applicant sexual orientation on willingness to engage in work-related contact (Hypothesis 7). Similarly, we predicted two opposite indirect effects of applicant sexual orientation on hireability judgments (Hypothesis 8): More positive gay stereotypes (applied to the gay man vs. the heterosexual man) should result in higher perceived communion, which should be related to higher hireability judgments, whereas lower masculinity ratings (of the gay man vs. the heterosexual man) should be related to lower agency impressions, which should in turn be related to lower hireability judgments. In the same mediation models, we explored whether there is also an effect of masculinity on perceived communion, as well as an effect of gay stereotypicality on perceived agency.

Method

Participants

The research sample consisted of 273 German-speaking participants (148 female, 107 male, 18 non-responses). Their age ranged from 16 to 73 years-old (M = 25, SD = 12). In order to arrive at a diverse and large sample and thus increase generalizability of findings and statistical power, participants were recruited using several strategies. Specifically, we recruited participants online via social networks (n = 104), in a vocational school (n = 98), and in the city center of a small town in the southwest of Germany (n = 71), the latter either online or using paper-and-pencil according to their preference. They were invited to take part in a study on “personnel selection.” Psychology students were invited to participate in exchange for course credit; participants recruited in the city center were offered €3 in exchange. The other participants received no compensation.

All patterns of statistical findings (i.e., significance) reported here remain identical if manner of data collection is used as a covariate in the analyses. Most participants reported to be Catholics (149, 55%) or Protestants (68, 25%); another 25 (9%) were atheists, 15 (6%) reported other faiths, 16 (6%) did not respond; however, average reported religiousness was quite low, M = 2.75 (SD = .1.68; scale: 1–6, “not at all” to “very”). This appears typical of the population in the southwest of Germany. Regarding their sexual orientation, 242 (88%) reported to be heterosexual, 21 (8%) did not respond, 6 (2%) were bisexual and 4 (2%) were gay/lesbian. When asked whether they had gay/lesbian friends, 160 (59%) responded yes, 100 (37%) responded no, and 13 (5%) did not respond. Neither gay/lesbian nor heterosexual participants were excluded from analyses; but excluding the few gay/lesbian participants would not alter the pattern of significant findings.

Design

The experiment had a one-factor between-subjects design, using the male applicant’s sexual orientation (gay vs. heterosexual) as the independent variable. Dependent variables were ratings on gay stereotypicality, communion, masculinity, agency, the willingness to engage in work-related contact, and hireability. Participants were randomly assigned to conditions. An a priori power analysis indicated that to detect medium-size main effects of f = .25 of target sexual orientation with α = .05 and a probability of 1 – β = .95, at least 210 participants were needed (Cohen 1977; Faul et al. 2007).

Materials

All ratings were done on 6-point Likert-type scales (anchored 1 to 6), and surveys were conducted in German. Agency of the applicant was measured averaging five items (translations: self-confident, ambitious, determined, assertive, successful; Cronbach’s α = .84). Communion of the applicant was measured averaging four items (trustful, likeable, fair, empathic; α = .80). Both scales ranged from 1 (I totally disagree) to 6 (I fully agree) and were taken from previous research (Rudman and Glick 1999, 2001). Hireability included three averaged items ranging from 1 (not at all likely) to 6 (extremely likely). It was assessed by asking the participants to indicate the probability that (a) they would personally interview the applicant for the job, (b) the applicant would be hired for the job, and (c) they would personally hire the applicant for the job (α = .86) (Rudman and Glick 1999, 2001) (German versions, Steffens and Mehl 2003). All items have been used often, possess high face validity, and yielded expected findings, but to the best of our knowledge, no formal studies to corroborate their validity have been published.

We developed six items that were averaged to measure participants’ willingness to engage in work-related contact (e.g., “I would like to share an office with Mr. Hofer.”, “I would like to spend my lunch-break with Mr. Hofer.”; α = .80, see the online supplement for all items), using the same response options as above, from 1 (I totally disagree) to 6 (I fully agree). A factor analysis indicated that all items loaded on one factor that explained 50% of the variance (eigenvalue >1, inspection of the screeplot corroborated extraction of one factor; all factor loadings > .62).

One direct item was used to assess how masculine the applicant was perceived (for discussion, see Kachel et al. 2016). Because ascribing femininity to men may be subject to socially desirable responding, we instead developed a five-item scale to reveal perceived gay stereotypicality and used only statements that were positively toned. Participants were asked to indicate for example, whether the applicant “is dressed tastefully,” or “is a good dancer” (see the online supplement for all items). A factor analysis indicated that all items loaded on one factor that explained 46% of the variance (eigenvalue >1, inspection of the screeplot corroborated extraction of one factor; this was true also if separate analyses were done for each condition; all factor loadings > .57). Scores were averaged to obtain an index of gay stereotypes such that higher scores indicate greater stereotyping. Regarding both scales, items were generated and revised until total consensus among the authors was reached. In a pilot study, 15 psychology students agreed that each item was easy to understand and had adequate face validity. No formal study to corroborate the scale’s validity has been done yet.

Procedure

Either participants completed the questionnaire online or they were handed a paper-and-pencil version. After signing informed consent, participants read a short introduction. They were asked to imagine they were an employee in a medium-sized company in which a position was available and they were asked by their supervisor to give a second opinion regarding one of the applicants. After this introduction, an extract of a hypothetical job interview in written form was presented (modified from Niedlich et al. 2015). The interview contained four questions with the applicant’s answers: “Have you ever worked in a similar company?,” “Why did you leave your previous job?,” “Do you prefer working in a team or alone?,” and “How do you react in stressful situations?” The two conditions differed only in the applicant’s response to the second question “Why did you leave your previous job?” Corresponding answers revealed information about the sexual orientation of the applicant, mentioning that he and his male/female partner (in German: “Mein Lebensgefährte”/“Meine Lebensgefährtin”) had moved because they wanted to live in this area. With regard to the other questions, the applicant’s responses were rather vague to indicate intermediate qualifications.

After reading the extract of the job interview, participants first rated the applicant regarding willingness to engage in work-related contact and gay stereotypes. Then, projected communion and agency of the applicant were measured in an intermixed fashion. The projected masculinity item followed, embedded among several filler traits that were not analyzed. On a subsequent page, participants rated the applicant’s hireability. The experiment ended with the manipulation check that asked participants to indicate the applicant’s sexual orientation, and demographic data were collected. On the final page, participants were debriefed. Materials and data have been stored in a public repository (https://osf.io/sy4mf/).

Results

In all analyses in the present article, significance tests were conducted with p < .05. Preliminary analyses tested whether participant gender should be included as a factor in all analyses, but only one non-significant interaction emerged. Briefly, female as compared to male participants indicated more willingness to work together with gay applicants (for details, see the online supplement). The manipulation check showed that most participants remembered the applicant’s sexual orientation (85% correct responses). Excluding participants because of their responses to the manipulation check would compromise random assignment to conditions, therefore, all data were analyzed. Supplementary analyses in which participants were excluded who failed the manipulation check showed that all patterns of statistical findings (i.e., significance) remained identical.

Table 1 shows bivariate correlations between all variables in Experiment 1, separately for the gay male and the heterosexual male applicants. All correlations were positive and almost all were statistically significant, indicating that participants had general response tendencies to rate an applicant more positively or more negatively. The pattern of correlations largely corresponds to expectations: Hireability and work-related contact were closely related; agency and communion correlated highly both with hireability and with work-related contact; and gay stereotypes showed the highest correlation with communion.

Gay Stereotypes, Communion, Masculinity, and Agency

Table 1 shows average ratings by applicant’s sexual orientation. As expected in Hypothesis 1, a one-way ANOVA showed that gay men were indeed ascribed higher positive gay stereotypes than were heterosexual men, F(1,271) = 8.11, p = .005, ηр2 = .03. In addition and in line with the stereotype that gay men transgress gender roles, the ANOVA on communion showed that gay applicants were rated higher than heterosexual applicants were, F(1,271) = 6.38, p = .012, ηр2 = .02. This finding corroborates Hypothesis 2. With regard to masculinity our assumption was also confirmed. Gay applicants were rated significantly less masculine than were heterosexual applicants, F(1,271) = 6.43, p = .012, ηр2 = .02, which is in line with Hypothesis 3. Not yielding any evidence for Hypothesis 4, gay and heterosexual men were rated similar in agency (F < 1), and the gay applicant was descriptively rated a bit higher. With regard to willingness to engage in work-related contact and hireability, heterosexual and gay men were not rated differently; in other words, no direct effects of sexual orientation could be observed on work-related contact and hireability (both Fs < 1).

Regression Analyses

As indicated in the hypotheses, we expected communion and agency to determine willingness to engage in work-related contact and hireability. The impressions based on the correlations in Table 1 were confirmed in two regression analyses with work-related contact and hireability as dependent variables. Communion and agency were concurrently used as independent variables. The overall regression model on willingness to engage in work-related contact was statistically significant, F(2,270) = 89.50, p < .001, R2 = .40. Communion (B = .54, SE = .05, β = .52) determined work-related contact more than agency (B = .20, SE = .05, β = .21) did. This finding supports Hypothesis 5. The overall regression model on hireability was also statistically significant, F(2,268) = 84.22, p < .001, R2 = .39. Communion (B = .48, SE = .07, β = .37) and agency (B = .44, SE = .06, β = .38) similarly contributed to hireability, corroborating Hypothesis 6. These findings also confirm that as intended, the job was perceived to require agency and communion to similar degrees.

Mediation Analyses

Next, mediation analyses tested whether there were indirect effects of sexual orientation on (a) work-related contact and (b) hireability, serially mediated by gay stereotypes and communion on the one hand as well as masculinity and agency on the other. To reiterate (see Fig. 1 for illustration), we assumed that gay men appear more gay stereotypical than heterosexual men (which we found in the prior analyses), and gay stereotypicality should be related to higher communion ratings, which should in turn be related to more willingness to work together with an applicant and higher hireability ratings. In contrast, heterosexual men should be perceived as more masculine than gay men (see prior finding), and masculinity should increase agency, which should increase the willingness to work together with an applicant and hireability ratings. At the same time, we allowed relations between gay stereotypicality and agency on the one hand, and masculinity and communion on the other, for exploratory reasons.

Unstandardized regression coefficients of the mediation analyses testing indirect effects of sexual orientation on a work-related contact (upper panel) and on b hireability (lower panel) mediated by gay stereotypes and communion as well as by masculinity and agency. Coefficients of grey dotted paths are not significant. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

We used the Latent Variable Analysis (LAVAAN) package in R to concurrently estimate several indirect effects, each with two serial mediators (Rosseel 2012). Standard errors were estimated using bootstrapping (with 1000 bootstraps). Findings indicated an indirect effect of sexual orientation (−1 = heterosexual, 1 = gay) on work-related contact, mediated by gay stereotypes and communion (see Fig. 1a). In detail, findings are in line with the idea that gay applicants were ascribed more gay stereotypes, gay-stereotyped applicants were perceived as more communal, and higher communion was related to more willingness to engage in work-related contact (indirect effect via both mediators: B = .04, SE = .01, z = 2.62, p < .01, 95% CI [.01; .06], standardized effect size: .04). The separate indirect effects for gay stereotypes and communion were not significant. Whereas Fig. 1a shows that the separate paths from sexual orientation to masculinity, from masculinity to agency, and from agency to work-related contact were also significant, the indirect effect was not statistically significant in a two-tailed test (B = −.01, SE = .01, z = −1.68, p = .09, 95% CI [−.01; .01], standardized effect: −.01). Only the indirect effect of sexual orientation on work-related contact mediated by masculinity was statistically significant (B = −.03, SE = .01, z = −2.20, p = .03, 95% CI [−.05; −.01], standardized effect: −.03), which is in line with the interpretation that heterosexual men were perceived as more masculine than gay men, which increased willingness to engage in work-related contact with them (and thus reduced the positive effect of a gay sexual orientation on willingness to engage in work-related contact mediated by gay stereotypes and communion).

There was no indirect effect mediated by agency, and the direct effect of sexual orientation on work-related contact was also not significant. Unexpectedly (see Fig. 1a), we also found significant effects of perceived gay stereotypicality on perceived agency and of perceived masculinity on perceived communion. In contrast, the respective indirect effects were not observed (i.e., no effect of sexual orientation, serially mediated by gay stereotypicality and agency, on work-related contact; nor an effect of sexual orientation, serially mediated by masculinity and communion, on work-related contact). Taken together, a considerable proportion of the variance in work-related contact could be explained by the variables in the model, R2 = .40.

We tested next the same set of regression models for the dependent variable hireability. The findings are shown in Fig. 1b and support Hypothesis 8. Data are in line with the following idea: Gay applicants were ascribed more gay stereotypes, and applicants ascribed more gay stereotypes were perceived as more communal, which in turn led to higher hireability judgments (indirect effect serially mediated by both mediators: B = .04, SE = .01, z = 2.48, p = .01, 95% CI [.01; .06], standardized effect: .03). The indirect effects mediated by the single mediators were not significant. Additionally, data were in line with the hypothesis that masculinity and agency mediated the relationship between sexual orientation and hireability: Gay applicants were ascribed less masculinity, and applicants ascribed less masculinity were perceived as less agentic, which was related to lower hireability judgments (indirect effect mediated by both mediators: B = −.02, SE = .01, z = −2.35, p = .02, 95% CI [−.03; −.01], standardized effect: −.02). Separate examinations showed there were no significant indirect effects via masculinity nor agency, and the direct effect of sexual orientation on hireability also was not significant.

Again (see Fig. 1b), we unexpectedly found significant effects of perceived gay stereotypicality on perceived agency and of perceived masculinity on perceived communion. This time, we also found a small, albeit significant indirect effect of sexual orientation, serially mediated by gay stereotypicality and agency, on hireability (B = .02, SE = .01, z = 2.29, p = .02, 95% CI [.01; .03], standardized effect: .02). In contrast, the indirect effect of sexual orientation, serially mediated by masculinity and communion, on hireability was not observed. Also for hireability, a considerable proportion of the variance could be explained by the variables in the model (R2 = .35). When we explored the reverse serial mediations, no statistically significant indirect effects were obtained (i.e., with communion/agency used as the first mediators and gay stereotypicality/masculinity as the second mediators).

Discussion

In a job context in which both agency and communion appeared relevant, gay men were ascribed higher gay stereotypicality than heterosexual men were and at the same time, gay male applicants were perceived as less masculine than heterosexual men were. Only partly confirming the predictions we made on the basis of the stereotype content model, gay men appeared higher in communion, but they were judged similar to heterosexual men regarding agency. We found no direct effects of applicant sexual orientation on participants’ willingness to engage in work-related contact with the applicant nor on hireability, but opposite indirect effects. Specifically, heterosexual men’s strength was seen in masculinity (and indirectly in agency), and gay men were regarded as more gay stereotypical and thus communal. Regarding work-related contact, findings are in line with the idea that two opposite indirect effects cancelled each other out. On the one hand, the gay man was seen as more gay stereotypical than the heterosexual man was, which positively affected communion ratings, which in turn positively affected willingness to engage in work-related contact. On the other hand, the heterosexual man was seen as more masculine than the gay man was, which also affected willingness to engage in work-related contact positively, but for the other applicant.

Because hireability in the present job context equally depended on perceived agency and communion, there was also a trade-off between these “qualification profiles.” Replicating the positive indirect effect of a gay sexual orientation that we found for work-related contact, the gay male applicant was ascribed more gay stereotypes, and applicants ascribed more gay stereotypes were perceived as more communal, which in turn led to higher hireability judgments. Interestingly, we also observed two indirect effects mediated via agency: The gay applicant was judged more gay stereotypical than the heterosexual applicant, which positively affected agency perceptions and, in turn, hireability judgments. In contrast, the heterosexual applicant was judged more masculine than the gay applicant, which also positively affected agency perceptions and, in turn, hireability judgments. Taken together, for hireability, two positive indirect effects of a gay sexual orientation were cancelled out by one negative one.

The opposite indirect effects we found on hireability when both communion and agency were required for the job suggest discrimination of the gay applicant in a traditionally masculine job context and discrimination of the heterosexual applicant in a traditionally feminine job context. It is a limitation of Experiment 1 that our findings cannot be generalized to such job contexts. Extending our findings to traditionally masculine and feminine job contexts was a major aim of Experiment 2.

Why did we not find lower agency perceptions of the gay than heterosexual man? As one possible explanation, an inspection of Table 1 shows positive correlations among all measured variables, indicating that participants formed rather general positive impressions of an applicant (alternatively, rather general negative impressions). Possibly, the fact that we administered communion and agency items in an intermixed fashion reduced the discriminant validity of the scales. Alternatively, in hindsight, some of the agency ratings could depend more on the content of the interview than on other aspects of the applicant. For example, the gay applicant came out during the job interview, and negative ratings on two of the items could have been avoided by that: His coming-out could have increased his perception as self-confident and assertive. In Experiment 2, we avoided both of these procedural aspects. Whereas the findings pertaining to gay stereotypes and to the willingness to engage in work-related contact with an applicant largely conformed to expectations, both scales were developed in Experiment 1 and still need to be validated. They were therefore omitted in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 had two aims. First, we wanted to directly test the previously noted implication that the heterosexual applicant is preferred in traditionally masculine job contexts and the gay applicant in traditionally feminine job contexts. Second, we wanted to conceptually replicate two patterns of findings from Experiment 1: first, that a heterosexual applicant is regarded as more masculine than a gay applicant, but less communal, whereas no significant difference in agency is observed; and second, for traditionally masculine jobs, an indirect effect of masculinity on hireability is mediated by agency. Because agency should play less of a role for traditionally feminine jobs, no comparable mediation is expected.

In contrast to Experiment 1, we asked participants to directly compare two applicants (Heilman and Okimoto 2008) regarding trait ascriptions and hireability for a range of different jobs. Participants first saw at the same time the short profiles of two fictitious male applicants, a gay and a heterosexual one. Sexual orientation was manipulated by presenting information on the family status instead of coming-out during a job interview. Participants were then asked to compare the applicants regarding different ratings (i.e., judgments indicated relative preferences for one or the other applicant).

A secondary aim of Experiment 2 was to test how much implicit associations of masculinity/femininity with gay/heterosexual men predict biased impressions of the applicants by using an implicit association test (Greenwald et al. 1998). In fact, implicit associations of gay/feminine and heterosexual/masculine were descriptively related to higher communion and lower agency ratings of the gay applicant, but not to hireability ratings. Because they contribute little to the overall aim of this paper, the method and findings are reported in an online supplement.

We tested the following hypotheses: Gay men should be ascribed higher communion than heterosexual men are (Hypothesis 1), but less masculinity (Hypothesis 2). If we replicate the pattern found in Experiment 1, we should observe no difference in agency ratings (Hypothesis 3). Across all jobs, we expect no discrimination of either the gay or the heterosexual applicant (Hypothesis 4). However, a closer look should reveal that hireability ratings for traditionally masculine jobs are relatively higher for heterosexual than gay male applicants (Hypothesis 5), whereas hireability ratings for traditionally feminine jobs should be relatively higher for gay than heterosexual male applicants (Hypothesis 6). Hireability ratings for traditionally masculine jobs should depend more on agency than on communion ratings (Hypothesis 7), whereas hireability ratings for traditionally feminine jobs should depend more on communion than agency ratings (Hypothesis 8). If we conceptually replicate those mediation findings of Experiment 1 that we could test in Experiment 2, then agency ratings should mediate the relationship between masculinity ratings and hireability for traditionally masculine jobs (Hypothesis 9).

Method

Participants

Participants were 32 female students (Mage = 22.25 years, SD = 2.59, range = 18–29) of different majors (education: 18, psychology: 10, other: 4) who participated in individual cubicles in the lab. Among them, 29 (91%) indicated being heterosexual, one bisexual, one other, and one did not respond. Average political attitude (1 = very left-wing, to 7 = very right-wing) was 3.13 (SD = 1.01) and was not related in a statistically significant way to any of the dependent variables in the present experiment. Participants were invited to take part in two studies taking 30 min altogether in exchange for either course credit or a cafeteria voucher worth €2.50. (Study 2 is irrelevant to the present purposes and will not be mentioned further.)

Design

The experiment had a within-subject design. It was counterbalanced whether Applicant A was presented as gay and Applicant B as heterosexual, or vice versa. Applicants were given common German names (Michael Wagner, Andreas Kästner). Dependent variables were relative ratings (e.g., “applies more to Michael W.”) on communion, masculinity, agency, hireability for traditionally masculine jobs and hireability for traditionally feminine jobs. An a priori power analysis indicated that, given the within-subject design, to detect a medium-size effect (f = .25) of target sexual orientation with α = .05 and a probability of 1 – β = .80 in a two-tailed t-test, 34 participants were needed (Cohen 1977; Faul et al. 2007). However, in the regression and mediation analyses reported below, only large effects could be detected with sufficient statistical power.

Materials

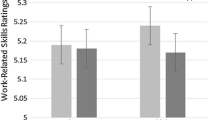

All ratings used 7-point Likert-type scales, and scores were again averaged. Similar to Experiment 1, we measured perceived masculinity (1 item), communion (3 items: warm, team-oriented, likeable, Cronbach’s α = .62), and agency (2 items: competent, efficient, r = .49; competitive had to be excluded because of otherwise insufficient scale reliability). Scale reliabilities were relatively low due to the brevity of the scales, but none of the reported nonsignificant findings were significant for single items; therefore, it is more informative to report the averaged findings.

In contrast to Experiment 1, because two applicants were presented, we collected comparative ratings (e.g., team-oriented: 1 = “applies clearly more to Michael W.” to 7 = “applies clearly more to Andreas K.,” with 4 indicating equal applicability). Then, participants rated who appears better suited for six different traditionally masculine jobs (roofer, car mechanic, police officer, power plant manager, investment banker, qualified IT specialist: 1 = “I think Michael W. is clearly better suited”, to 7 = “Andreas K. is clearly better suited”, α = .87) and six traditionally feminine jobs (flight attendant, choreographer, nurse, arts and music teacher, perfume manufacturer, kindergarten teacher; α = .78). Jobs were presented on one page in an inter-mixed fashion. All variables were (re)coded such that higher scores indicate “the gay applicant more than the heterosexual applicant.”

Procedure

After signing informed consent, participants received instructions on the computer screen. They learned that we were interested in their first impressions of two applicants based on very limited information. Then, they saw two short profiles of applicants: one on the left, the other on the right of the computer screen. Profiles contained names (Andreas Wagner, Michael Kästner—common German names with similar stereotypes regarding age, agency, and communion, Rudolph et al. 2007); profiles also showed e-mail-addresses, two comparable home towns (both in Bavaria in southeast Germany: Erlangen, Würzburg), language proficiencies, and (rather common) hobbies. Current job and education were masked. Sexual orientation was manipulated by presenting “family status: married with husband Matthias [wife Kathrin] Wagner/Kästner.” That way, a coming-out during the job interview that might be perceived as agentic was avoided. Family status is often included in resumes in Germany. Sexual-orientation information was counterbalanced between the left and right profiles. All information was provided in German.

On the next page, participants were asked to compare the qualifications of Michael W. and Andreas A. To avoid confusion, the name belonging to the profile that had been presented on the left was used as the left anchor of the scale; the name on the right as the right anchor. Participants were asked to indicate which traits apply more to which applicant. Agency traits were presented first, followed by communion, followed by masculinity. On the next page, they were asked to indicate which applicant they would rate as better suited for which job. The final page contained the manipulation check, using two open questions regarding the sexual orientation of each applicant. Subsequently, the IAT was administered (see the online supplement for details and findings; bivariate correlations of the IAT effect with the other variables are reported in Table 1s). Demographic information was collected in Study 2, including political orientation (Hoyt and Parry 2018). Finally, participants were debriefed. Materials and data have been stored in a public repository (https://osf.io/sy4mf/).

Results

The manipulation check showed that all participants correctly remembered that the applicant married to a woman had been heterosexual and the applicant married to a man had been gay (resp. bisexual). Table 2 shows means and bivariate correlations between all variables in Experiment 2. Again, all correlations between masculinity, agency, and communion were positive, indicating that participants had general response tendencies to rate one applicant, relative to the other, more positively or more negatively. Masculinity, agency, and hireability for traditionally masculine jobs were closely related, whereas communion played a smaller role for hireability for traditionally masculine jobs, as predicted in Hypothesis 7. In contrast, communion was descriptively more strongly related than agency to hireability for traditionally feminine jobs, as predicted in Hypothesis 8. Hireability for traditionally masculine and traditionally feminine jobs correlated negatively in a nonsignificant way.

Communion, Masculinity, and Agency

As shown in Table 2 and as expected, t-tests against the scale midpoint (4) showed that more communion was attributed to the gay than to the heterosexual applicant (Hypothesis 1), t(31) = 2.87, p = .007, d = .50, and the heterosexual applicant was rated more masculine than the gay applicant (Hypothesis 2), t(31) = 4.34, p < .001, d = .77. Also replicating the finding from Experiment 1 (Hypothesis 3), both were rated equally agentic (t < 1).

Hireability

Across all 12 jobs, neither the gay nor the heterosexual male applicant received higher ratings, t(31) = 1.07, p = .29, in line with the idea that there is no general hiring bias against one or the other applicant (Hypothesis 4). However, in line with expectations, the gay applicant was rated better suited for traditionally feminine jobs (Hypothesis 5), t(31) = 4.46, p < .001, d = .79, and the heterosexual applicant for traditionally masculine jobs (Hypothesis 6), t(31) = 2.34, p = .03, d = .41. In fact, Ms > 4.37 were obtained for each of the six traditionally feminine jobs, indicating higher hireability of the gay applicant, whereas Ms < 3.88 were obtained for each of the traditionally masculine jobs, indicating higher hireability of the heterosexual applicant.

Regression Analyses

As indicated in the hypotheses, we expected communion and agency to determine hireability for traditionally feminine and traditionally masculine jobs to different degrees. The impressions from Table 2 were tested in two separate regression analyses. Communion and agency were concurrently used as independent variables. The overall regression model on hireability for traditionally masculine jobs was statistically significant, F(2,29) = 14.33, p < .001, R2 = .50. Agency determined hireability ratings (B = .93, SE = .20, β = .70), but communion did not (B = .01, SE = .19, β = .01). This pattern supports Hypothesis 7. The overall regression model on hireability for traditionally feminine jobs was not statistically significant with the present sample size, F(2,29) = 2.12, p = .14, R2 = .13. The effect of communion missed the pre-set criterion of statistical significance (B = .40, SE = .20, β = .41, p = .053) and the negative effect of agency was nonsignificant (B = −.30, SE = .21, β = −.29, p = .17). In other words, Hypothesis 8 was not supported in the regression analysis.

Mediation Analysis

Next, a mediation analysis tested whether there was an indirect effect of masculinity on hireability for traditionally masculine jobs, mediated by agency. To test this simple mediation model we used PROCESS (Model 4, Hayes 2013). The first regression equation corroborated the significant effect of masculinity on agency (B = .65, SE = .14, t = 4.69, p < .001). In the second regression equation, two predictors, masculinity (B = .32, SE = .14, t = 2.36, p = .03) and agency (B = .40, SE = .14, t = 2.90, p = .007) were included and were both related to hireability for traditionally masculine jobs. Analyses of direct and indirect effects were in line with the idea that the effect of masculinity on hireability for traditionally masculine jobs is partly mediated by agency (Hypothesis 9) (indirect effect: B = .26, SE = .11, using 5000 Bootstrap re-samples 95% CI [.07; .50]; direct effect: B = .32, SE = .14, 95% CI [.04; .60]).

No indirect effect was obtained when communion was used as the mediator in the same model (95% CI [−.08; .21]). Similarly, there were no indirect effect of masculinity on hireability for traditionally feminine jobs mediated by agency (95% CI [−.08; .21]) and no statistically significant indirect effect of masculinity mediated by communion on hireability for traditionally feminine jobs (95% CI [−.01; .24]).

Discussion

Experiment 2 used a different study design that included relative judgments of the gay versus heterosexual applicant. Using an all-female student sample, we replicated the finding that gay applicants are ascribed more communion and less masculinity but similar agency, as compared to heterosexual applicants. The lack of effect found on agency in Experiment 1 thus does not appear to be due to the coming-out during the job interview nor due to the fact that agency and communion were measured concurrently. Both procedural aspects were avoided in Experiment 2. We return to the lack of effect on agency in the General Discussion.

Overall, as predicted, replicating Experiment 1, no hiring bias was found: Across all jobs, both applicants appeared similarly suited. Extending the findings of Experiment 1, ratings of masculinity and agency predicted which applicant is considered suitable for which type of job: The heterosexual applicant appeared better suited for traditionally masculine jobs than the gay applicant, whereas the gay applicant appeared better suited for traditionally feminine jobs than the heterosexual applicant. Higher communion ratings of the gay as compared to the heterosexual applicant were descriptively related to his appearing more suited for traditionally feminine jobs, but this effect was not statistically significant with the present sample size. In contrast, higher agency ratings of the heterosexual as compared to the gay applicant were related to his appearing more suited for traditionally masculine jobs, and mediation analysis showed an indirect effect of masculinity on hireability mediated by agency, but also a direct effect, indicating partial mediation.

Whereas the present sample was small, due to the comparative ratings of the gay versus heterosexual applicant, it was clearly sufficiently large to detect the expected main effects. The nonsignificant effect on agency would not be obtained with a larger sample, either, because descriptively, the gay applicant was rated a bit more agentic than the heterosexual applicant, similar to Experiment 1. The sample size was more problematic for testing the expected relations between constructs. The nonsignificant effect of communion on hireability for feminine-typed jobs cannot be interpreted in favor of the null hypothesis because of its substantial effect size (β = .41), so basically, no conclusions can be drawn from this null finding, and the hypothesis awaits replication with a larger sample. Generally, the presented findings cannot be extended to male participants.

Whereas the findings of Experiments 1 and 2 cannot directly be compared because different paradigms and scales were used, we want to point out that descriptively, the relation observed between communion ratings and hireability ratings was much larger in Experiment 1. It is possible that other considerations, in addition to applicant suitability, played a role for the relative ratings in Experiment 2. For example, participants may have assumed that a gay man could be more interested in traditionally feminine jobs than a heterosexual man, and vice versa for traditionally masculine jobs. Another indicator for the idea that other considerations in addition to perceived communion and agency played a role is the finding that there was only a partial mediation of perceived masculinity mediated via agency on hireability for traditionally masculine jobs: Partial mediation suggests that other mediators are at work, too.

Experiment 2 collected comparative ratings. In that way, we had hoped to avoid socially desirable responding by giving participants the opportunity to judge one applicant as better suited than the other for some jobs, and vice versa for others. However, this procedure created some ambiguity in the obtained ratings because a mid-scale rating of “4” could imply that both applicants appear low, or that both appear high regarding, for instance, team-orientation. Possibly, this is a reason why the obtained correlations were smaller than in Experiment 1.

General Discussion

Sexual orientation stereotypes intersect with gender stereotypes: Heterosexual men are perceived to be more gender-typed than are gay men. The aim of the present experiments was to test the consequences of these perceptions in simulated hiring decisions. Findings with two samples from Germany showed that indeed gay men were perceived as higher in gay stereotypicality than heterosexual men were (Experiment 1). As we expected, gay applicants were also perceived as less masculine than heterosexual men were in both experiments. Partly confirming the predictions we made on the basis of the stereotype content model, gay men appeared higher in communion (Experiments 1 and 2), but they were judged similar to heterosexual men regarding agency (Experiments 1 and 2). These different impressions affected hireability ratings: Whereas a gay and a heterosexual applicant appeared equally hireable for a job that required communion and agency to similar degrees (Experiment 1), the gay applicant appeared more hireable for traditionally feminine jobs than the heterosexual man, who, in contrast appeared more hireable for traditionally masculine jobs than the gay applicant (Experiment 2). Both experiments converged on the finding that the heterosexual male applicant appearing higher in masculinity, and in turn in agency, as compared to the gay male applicant, positively affected perceived hireability for traditionally masculine and gender-neutral jobs. Whereas Experiment 1 showed that at the same time, perceived hireability of the gay as compared to the heterosexual male applicant was positively affected by his perceived gay stereotypicality and, in turn, communion, Experiment 2, with a smaller sample, could not corroborate the positive effect of the gay male applicant’s perceived higher communion on hireability for traditionally feminine jobs, compared to the heterosexual male applicant.

A first substantial finding of the present study is that gay men were more associated with gay stereotypes than heterosexual men were (e.g., “being a good listener”), and, transferred to constructs that are important in work contexts, they were also judged higher in the “typically female” strength, which is communion (e.g., team-oriented). This corroborates previous findings on group stereotypes (Asbrock 2010; Clausell and Fiske 2005). Along with other recent research from the United States and Germany (Clarke and Arnold 2018; Everly et al. 2016; Kranz et al. 2017; Niedlich and Steffens 2015), our findings show that gay men have an advantage over heterosexual men in application processes in which communion-related traits are of particular importance (e.g., traditionally feminine jobs). Future studies could also investigate hiring decisions in which team building processes and efficient teamwork are particularly relevant. Moreover, possible negative consequences of the apparently positive stereotypes treated here should be examined (also see Kranz et al. 2017). As a side note, we are not implying that apparently positive stereotypes cannot have detrimental effects for social equality (on the contrary, see Glick and Fiske 2001; Sidanius and Pratto 1999). Nevertheless, we believe it is important to examine the (positive and negative) consequences of positive and negative aspects of group stereotypes because they may have real-life implications.

A second substantial finding is that participants perceived gay applicants to be less masculine than heterosexual applicants. Taken together, mere group membership thus led to different impressions of targets in spite of the fact that the same individualized information about them was presented, corroborating the influence of group stereotypes on impressions of individuals (Fiske and Neuberg 1990). However, we should note that the reported effects would be classified as small effects. Nevertheless, one should not underestimate their practical significance if such distortions in work-related impressions of individuals occur on a daily basis (“mountains are molehills, piled one on top of the other”; Valian 2007, p. 35).

Both experiments converged on finding no differential ascription of agency to the heterosexual versus gay male applicant. Experiment 1 used items measuring instrumentality, whereas Experiment 2 assessed competence more narrowly. Using similar items as we did in Experiment 1, another experiment from Germany even reported that the gay male applicant was rated higher than a heterosexual man (Niedlich and Steffens 2015). Along with studies reporting that men were no longer ascribed higher agency than women, both from the United States and from Germany (Diekman and Eagly 2000; Ebert et al. 2014; Wilde and Diekman 2005), this suggests that the stereotype “male = agentic” is eroding. Our finding that masculinity was more ascribed to the heterosexual than to the gay male applicant, whereas there was no difference in agency, supports the distinction between masculinity and agency (Kachel et al. 2016).

In Experiment 1, no direct effects of sexual orientation on work-related contact and hireability were found because of indirect effects that were offset by reverse effects. Similarly, in Experiment 2, no overall effect of sexual orientation on hireability across 12 jobs was found. Instead, the gay male applicant appeared more hireable for the traditionally feminine jobs, whereas the heterosexual male applicant appeared more hireable for the traditionally masculine jobs. Taken together, these findings show that the qualification profiles participants ascribed to heterosexual and gay men differed, with heterosexual men’s perceived strength in masculinity, and gay men’s strength in communion. If hireability equally depended on perceived agency and communion, there was a trade-off between these “qualification profiles.” Similar reasoning applied to work-related contact (Experiment 1): People were not only interested in working together with nice colleagues, but also with competent ones.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

A limitation of Experiment 1 is that the causal chain hypothesized in these serial mediations was not experimentally demonstrated. Also, these path analyses demonstrated unexpected effects. Perceiving a male applicant as high in masculinity did not only increase agency perceptions, which we had expected, but also increased perceptions of communion. Similarly, perceiving a male applicant as gay stereotypical did not only increase perceptions of communion, which we had expected, but also increased agency perceptions. The path analysis also showed an indirect effect that suggests the following interpretation: Because gay men are perceived as higher in gay stereotypicality than heterosexual men are, they are also perceived as higher in agency, and in turn, this increases hireability judgments. These effects were small and they were not hypothesized; thus they need to be replicated. Still, along with several others, our findings suggest that agency and communion in person perception are correlated rather than independent or inverse. For example, we observed positive correlations between all traits we measured, suggesting that an applicant who appears communal is expected to be agentic, too. Similar positive correlations have been observed in impression formation studies in other contexts (see Hansen et al. 2017, for ethnicity). A basis for this could be that communion is considered the primary dimension of the “big two” (Abele and Bruckmüller 2011) because communal traits are other-profitable, which means that it matters more to a given person whether a target is communal or not than whether the target is agentic or not (agency, in contrast, is considered self-profitable). However, note that there is evidence for a curvilinear relationship between agency and communion, with the highest communion ratings observed at intermediate agency (Imhoff and Koch 2017), whereas we found high communion ratings co-occurring with relatively high agency ratings.

When interpreting our findings from Germany, the cultural context needs to be considered. Everly and colleagues (Everly et al. 2016) recently reported a positive hiring bias towards gay men (and lesbians) among their U.S.-based female participants, but a negative bias among their male participants. Those findings stand in contrast to the present ones in which hardly any effects of participants’ gender were found (but see the online supplement). A reason for this discrepancy could be cultural differences between Germany and the United States, with anti-gay attitudes being less widespread in Germany (for discussion and a similar pattern of findings in Germany, see Kranz et al. 2017). We need to point out that, more generally, findings regarding gender stereotypes cannot be generalized across time and culture. For example, a recent correspondence test even found different patterns of lesbian discrimination in two different German cities (Munich and Berlin; Weichselbaumer 2015). Possibly, a reason for this difference is that employers in Munich, where lesbian discrimination was observed, are more conservative than in Berlin, where no discrimination was found (see Hoyt and Parry 2018, but also see the present Experiment 2). And the stereotype that gay men transgress gender roles could itself be waning in several cultures (see Clarke and Arnold 2018, for discussion). Similarly, it is a limitation of our study that the average age of our participants was 25 years or younger, so they are part of the cohort with the most positive attitudes toward gay men as compared to other age groups in Germany (see Steffens and Wagner 2004). Findings cannot be generalized to age groups with more negative attitudes.

Several other limitations of the present research should be mentioned. First, all our outcome variables were measured in the context of simulated hiring decisions. Participants did not judge applicants in real-life situations in which power relations, promotion opportunities, and status may provoke others’ discrimination for own benefits and interests. In a simulated hiring decision showing positive stereotypes and particularly positive emotions for one specific discriminated group could overshadow own career strategies that are important in real life. However, simulated hiring decisions are a good addition to field experiments because the latter may show discrimination, but they cannot investigate underlying processes as well as lab experiments can.

A second weakness of our study is that we did not ask participants whether they were experienced in personnel selection and we assume most were not. However, several studies have shown comparable findings in simulated hiring decisions, whether participants were Human Resource professionals or students (Everly et al. 2016; Heilman and Okimoto 2008; Steffens and Mehl 2003). Also, our findings converge with a recent U.S.-based study in which adults with experience in hiring were recruited (Clarke and Arnold 2018). Both their experiment and ours can be interpreted as demonstrating that heterosexual men are perceived as more gender-typed than gay men are.

A third limitation is that the scale measuring willingness to engage in work-related contact used in Experiment 1 was not validated by previous research, but rather developed for the current study, as was the scale on gay stereotypes. The expected findings and the high correlations between hireability and willingness to engage in work-related contact can themselves be considered indicators of validity. Still, we think it would be worthwhile for future research to validate a scale on willingness to engage in work-related contact that can be used across different job contexts.

A final limitation is that the way in which sexual orientation is signaled may affect research findings (for discussion, see Tilcsik 2011; Weichselbaumer 2015). Different findings could result if sexual orientation was signaled in a different way, for example, by activism in a gay association that may lead to discrimination against activists. In Experiment 1, sexual orientation was revealed voluntarily by the applicant during the job interview. Whereas we had speculated that this may have increased agency perceptions, in the absence of the coming out, agency findings were replicated in Experiment 2. We recommend future research to signal sexual orientation by using a different manipulation (for discussion, see Steffens et al. 2016).

In addition to the task-competence and instrumentality aspects of agency that we measured in our research, an important aspect of agency is dominance (Glick et al. 2004). Women’s dominant behavior has been found to be particularly proscribed and punished (Rudman et al. 2012). An extension of the current research would be to introduce applicants who differ in sexual orientation and show dominant behavior: It is possible that gay men, perceived to be members of the category “men,” are more entitled to show dominant behavior than (heterosexual) women are. It is also possible that lesbians, who are regarded as deviating from traditional female gender roles (Niedlich et al. 2015; Peplau and Fingerhut 2004), are perceived to be more entitled to behave dominantly than heterosexual women are. In any case, when interpreting the present findings, it needs to be born in mind that the heterosexual and gay male applicants we introduced appeared comparable with regard to task-competence and instrumentality, but that we did not assess perceived dominance.

Practice Implications

Using simulated hiring decisions, we demonstrated that (young) people (in Germany) arrive at different impressions of a gay and a heterosexual man even though the same information is provided about both of them. Based on group stereotypes, gay men are assumed to be high in communion (e.g., team-oriented, empathic), whereas heterosexual men are assumed to be masculine. Put differently, a gay applicant needs to demonstrate his masculinity, which is taken for granted for a heterosexual male applicant, whereas a heterosexual male applicant needs to demonstrate that he can work in a team, possesses social sensitivity, and the like. Interestingly, regarding task-competence and instrumentality (e.g., ambitious, determined), similar impressions were formed regardless of sexual orientation. No discrimination was observed on hireability for jobs requiring both agency and communion nor on the willingness to work together with an applicant (in other words: the gay and the heterosexual man received comparable ratings). For traditionally feminine jobs, gay men were preferred over heterosexual men. Conversely, for traditionally masculine jobs, gay men had worse chances than heterosexual men did.

In a nutshell, we found discrimination of individuals based on group stereotypes. It depended on the job context which pattern of discrimination was observed. In other words, each social group gets their share: either the gay man was discriminated, or the heterosexual man was discriminated, or neither of them. Equal treatment is often included in laws, but it is hard to obtain when people form impressions of individuals because group stereotypes exist. Human Resource professionals, job counsellors, and others (e.g., therapists) should make sure that the impressions they form of individuals are unbiased by social group membership. They should take the time to collect individual information instead of relying on stereotypes. Individuals, in particular if they belong to minorities, should be aware that they may be stereotyped. They should make sure to provide unambiguous information pertaining to their skills and competencies, which has been demonstrated to mitigate effects of group stereotypes in other contexts (e.g., Aranda and Glick 2014).

Conclusion

Much evidence attests to the discrimination of gay men. Only a few studies have found that gay men may have an edge over heterosexual men (but see Steffens and Jonas 2010, for the finding that gay male couples are preferred as adoptive parents for teenage girls). As we showed, the typically female strength, communion, is ascribed more to an individual gay than to a heterosexual man, whereas masculinity is ascribed more to a heterosexual than to a gay man. Previous studies have demonstrated that gender stereotypes are applied to some women more than to others. Extending that pattern at the intersection of gender with sexual orientation, the present study demonstrates that gender stereotypes are also applied to some men more than to others. Consequently, depending on the job in question and the skills required for it, at times, either the gay man was discriminated in hireability judgments or the heterosexual man was.

References

Abele, A. E., & Bruckmüller, S. (2011). The bigger one of the 'Big Two': Preferential processing of communal information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 935–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.028.

Adam, B. D. (1981). Stigma and employability: Discrimination by sex and sexual orientation in the Ontario legal profession. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 18, 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.1981.tb01234.x.

Ahmed, A. M., Andersson, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2013). Are gay men and lesbians discriminated against in the hiring process? Southern Economic Journal, 79, 565–585. https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-2011.317.

Aranda, B., & Glick, P. (2014). Signaling devotion to work over family undermines the motherhood penalty. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 17, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430213485996.

Asbrock, F. (2010). Stereotypes of social groups in Germany in terms of warmth and competence. Social Psychology, 41, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000011.

Bailey, J., Wallace, M., & Wright, B. (2013). Are gay men and lesbians discriminated against when applying for jobs? A four-city, internet-based field experiment. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 873–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.774860.

Barrantes, R. J., & Eaton, A. A. (2018). Sexual orientation and leadership suitability: How being a gay man affects perceptions of fit in gender-stereotyped positions. Sex Roles. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0894-8.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215.

Choi, N., & Fuqua, D. R. (2003). The structure of the Bem Sex Role Inventory: A summary report of 23 validation studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 872–887. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403258235.

Clarke, H. M., & Arnold, K. A. (2018). The influence of sexual orientation on the perceived fit of male applicants for both male- and female-typed jobs. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 656. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00656.

Clausell, E., & Fiske, S. T. (2005). When do subgroup parts add up to the stereotypic whole? Mixed stereotype content for gay male subgroups explains overall ratings. Social Cognition, 23, 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.23.2.161.65626.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (revised ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cotner, C., & Burkley, M. (2013). Queer eye for the straight guy: Sexual orientation and stereotype lift effects on performance in the fashion domain. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 1336–1348. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.806183.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631.

Davison, H. K., & Burke, M. J. (2000). Sex discrimination in simulated employment contexts: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1711.

Deaux, K., & Lewis, L. L. (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 991–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.991.

Diekman, A. B., & Eagly, A. H. (2000). Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: Women and men of the past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1171–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200262001.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573.

Ebert, I. D., Steffens, M. C., & Kroth, A. (2014). Warm, but maybe not so competent? – Contemporary implicit stereotypes of women and men in Germany. Sex Roles, 70, 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0369-5.

Everly, B. A., Unzueta, M. M., & Shih, M. (2016). Can being gay provide a boost in the hiring process? Maybe if the boss is female. Journal of Business Psychology, 31, 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9412-y.

Fasoli, F., Maass, A., Paladino, M. P., & Sulpizio, S. (2017). Gay-and lesbian-sounding auditory cues elicit stereotyping and discrimination. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1261–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0962-0.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.