Abstract

Women leaders in the workforce are adversely affected by two sets of stereotypes: women are warm and communal but leaders are assertive and competent. This mismatch of stereotypes can lead to negative attitudes toward women leaders, however, not all individuals will be equally sensitive to these stereotypes. Men and women characterized by a need for cognitive closure (the desire for stable and certain knowledge) should be particularly sensitive to these stereotypes because they can be stable knowledge sources. We hypothesized that (a) negative attitudes toward women leaders in the workforce would vary with individuals’ need for closure, independent of their gender, and that (b) binding moral foundations (a concern for the larger group and its norms and standards) would mediate this association. In two studies, MTurk workers completed measures of negative attitudes toward women managers (Study 1, n = 149), stereotyped beliefs of women as not wanting or deserving high status positions in the workforce (Study 2, n = 207), as well as need for cognitive closure, moral foundations, social desirability, gender, and political orientation. Our results were consistent with our hypotheses and suggest that attitudes toward woman managers can reflect acceptance of pre-existent norms. If these norms can be changed, then changes in attitudes could follow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Women face systematic difficulties achieving, and remaining in, leadership roles, even though there is no evidence that these difficulties are caused by a lack of ability (Baker 2014). There is a readily apparent cause for this problem: There exist stereotypes of women (e.g., warm, comforting) that are incompatible with stereotypes of leaders (e.g., competent, assertive). Women who violate the stereotypes of women in order to fulfill their role as leader are much more likely to consequentially receive negative evaluations (Eagly and Karau 2002; Fiske et al. 1999). They are more likely to be on the receiving end of backlash in the workplace, for instance, in both the hiring process (Rudman and Glick 2001) and when they hold leadership roles (Rudman et al. 2012). This issue is not shared by their male colleagues for whom leadership roles do not introduce stereotype mismatch.

That many people perceive a mismatch between women and leadership is supported by research that leadership has been traditionally construed in masculine terms (Koenig et al. 2011; Schein 1975). There is evidence for these stereotypes of women in many nations (e.g., China, Chili: Javalgi et al. 2011; Pakistan: Güney et al. 2013), in both governments (Brooks 2017) and business (Graham 2017; McKinsey and Company 2016), that they have been stable across the past three decades (Haines et al. 2016), and that they are highly accessible (Eagly and Karau 2002). These beliefs likely reflect a commonly-held shared reality that women are unsuitable for high status positions.

There is very strong evidence that women are adversely affected by the mismatch between stereotypes of women and stereotypes of leaders (for a review see Eagly and Karau 2002) but this assumes that individuals who have access to these stereotypes are affected by them in the same way. We instead propose that some individuals will be more affected than others and that there are some other factors that help explain negative attitudes and beliefs toward women leaders. Specifically, we propose that individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure, or a desire for epistemic certainty (Kruglanski 1996a), will be more likely to accept these stereotypes. Thus, individuals with a higher need for cognitive closure will be more likely to support stereotypes and schemas that influence their negative attitudes and beliefs toward women leaders. We further propose that the relationship between need for cognitive closure and negative attitudes toward women leaders will be mediated by individuals’ support of the binding moral foundations, which generally reflect supportive attitudes and judgments toward predominant cultural standards—including those that view women as inappropriate for leadership (Graham et al. 2009). In the following sections we briefly summarize the relevant literatures on need for cognitive closure and the binding moral foundations and present our research and hypotheses.

Need for Cognitive Closure and Prejudice

Need for cognitive closure helps explain how individuals approach new knowledge, and it can be thought of as both an individual difference and as a result of situational factors. That is, some individuals tend to have a higher need for cognitive closure across situations but there are also features of environments (e.g., time pressure) that can temporarily induce a need for cognitive closure (Kruglanski 1996b; Roets et al. 2015). Whenever an individual is presented with a question to which they do not have an answer (e.g., “Can women be good leaders?”), they open an epistemic process. When the individual either finds an answer or gives up his or her quest for one, the epistemic process is closed; need for cognitive closure describes how individuals navigate this process. An individual with either a chronic or an acute high need for cognitive closure has the desire for knowledge that is stable both in the present and into the future—or as long as they can be characterized by this need—and this influences how they approach new knowledge.

This approach underlies two motivational tendencies: the tendencies to “seize” and “freeze” on preexisting or otherwise accessible judgmental cues instead of elaborately processing new information. These tendencies reflects the desire of higher need for closure individuals to reach closure urgently and to keep it permanently (Kruglanski and Webster 1996). Under a seizing motivation, individuals are motivated to quickly grasp knowledge that can provide certainty; under a freezing motivation, they are motivated to defend their existing knowledge against alternative viewpoints. Once they have stable knowledge on a given topic, they are less likely to consider alternative opinions—as long as they can still be characterized by a need for cognitive closure.

Previous researchers have argued that gender roles (e.g., men, not women, are leaders) could be relied upon more under conditions consistent with a need for cognitive closure (see Eagly and Karau 2002, p. 578). Indeed, recent research has already identified the need for cognitive closure as a key antecedent of sexist attitudes toward women. Roets et al. (2012) found that Belgian men and women characterized by a higher dispositional need for cognitive closure also had higher levels of hostile sexism (i.e., a negative attitude toward women in nontraditional roles) and benevolent sexism (i.e., a seemingly positive attitude toward women in traditional roles); there was no evidence of an interaction of need for cognitive closure by respondents’ gender.

More generally, a higher need for cognitive closure has been found to be positively and significantly associated with factors associated with prejudice. This includes an increased reliance on readily-available schemas (Pierro and Kruglanski 2008), including not only stereotypes (Dijksterhuis et al. 1996) but also a dislike of change in established environments (Livi et al. 2015), a view of racial outgroups as uniform (Roets and Van Hiel 2011), the expression of intolerance and system-justifying attitudes (Jost et al. 1999) and, relevant for the present research, the manifestation of group-centric attitudes and behaviors (Kruglanski et al. 2006). We return to this specific point in the following sections.

Stereotypes can be seen as particularly attractive to individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure. Although stereotypes can obviously be very harmful, they also serve as stable sources of knowledge; if an individual believes in particular stereotypes (e.g., women are warm and comforting but leaders are competent and assertive) then this can guide their attitudes in an increasingly complex social world. There is nothing in a desire for stable knowledge that would inevitably lead one to the acceptance of specific stereotypes; however, the mismatch of stereotypes between women leaders is readily available and so this can be attractive to individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure. As a result, we would expect to see more negative attitudes toward women leaders because they violate their gender stereotype.

The association between need for cognitive closure and acceptance of negative attitudes toward women that was uncovered by Roets et al. (2012) can be better understood with the epistemic role occupied by stereotypes: Individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure may be more likely to seize upon, and freeze to, stereotypes because they provide stable knowledge and, consequentially, they should show higher levels of prejudice that is rooted in these stereotypes. A desire for epistemic certainty is not harmful in and of itself, but instead it creates an environment in which these views can be accepted and held with confidence. It is also possible that a higher need for cognitive closure can lead individuals to accept positive and non-stereotypical sources of knowledge (e.g., both women and men can be good leaders); we will consider this point in our discussion section. However, given the existence in many cultures of harmful stereotypes that affect women in leadership roles, we propose that individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure will be more likely to hold stereotypical and negative attitudes toward these women.

We further propose a mechanism that connects the need for cognitive closure with negative attitudes toward women in leadership roles: the tendency of individuals to endorse binding to accessible and ubiquitous norms and standards, including (but not limited to) those that view women as inappropriate for leadership. This can be conceived within moral foundations theory (Graham et al. 2009), briefly presented in the following section.

What Are the Moral Foundations?

Moral foundations theory claims that moral and political values are underlied by five basic intuitions or foundations (Graham et al. 2009). These five factors are Respect/Authority (i.e., a concern for the maintenance of masculine leadership and social hierarchies), In-group/Loyalty (i.e., a concern for faithfulness toward the ingroup), Purity/Sanctity (i.e., a concern with potential social but also physical contamination), Harm/Care (i.e., a concern for the well-being of individuals) and Fairness/Reciprocity (i.e., a concern toward individuals receiving what they deserve). The first three foundations can be described as the binding foundations because they can represent an overall concern for the dominant culture. Individuals who score higher on these foundations should be more likely to desire close-knit groups and to punish both threatening outgroup members and ingroup dissenters. The latter two foundations can be described as the individualizing foundations because they represent an overall concern for the well-being of the individual.

There are intriguing differences between individuals who score higher on the binding foundations versus those who score higher on the individualizing foundations. For instance, liberals generally score higher on the individualizing, but not binding, foundations, whereas conservatives generally score higher on both (Haidt and Graham 2007, but see Baldner et al. in press). Individuals who score higher on the binding foundations also typically endorse more conservative political views on a host of topics, even after controlling for political orientation (e.g., abortion, capital punishment; Koleva et al. 2012).

There is a debate over what precisely the moral foundations represent. They have been described as ostensibly innate intuitions, in the sense that they are organized in advance of experience (Marcus 2004), and thus are available to even very young children across cultures. According to Haidt and Joseph (2007), these intuitions are not virtues per se, but instead guide children and adults to develop culturally-appropriate virtues. If this view is correct then, properly speaking, need for cognitive closure could predict the binding foundations but it could not cause them. However, there are reasons to oppose this strict view of the moral foundations. Gray and his colleagues (Gray and Schein 2012; Gray et al. 2014) have argued that perceptions of immorality are linked to perceptions of implicit or explicit harm; their conclusion is consistent with previous research (Van Leeuwen and Park 2009) that has found that a perception of the world as dangerous predicted increased support of the binding foundations. Gray and colleagues argued that when an immoral act is not explicitly linked to an agent causing harm to a victim (as when someone murders an innocent person) then the perceiver of this act will instead perceive an implied agent causing harm to an implied victim. According to moral foundations theory, individuals who oppose women leaders could perceive them as violating the binding foundations, perhaps the Respect/Authority foundation. On the other hand, according to Gray’s theory these individuals could perceive women leaders as causing harm to traditional gender roles, whereas individuals who favor women leaders would not perceive any harm.

This debate is critical for the current research. If general perceptions of immorality are fundamentally tied to general perceptions of harm, then the five moral foundations are merely attitudes and judgments that develop across the life-span. Our research treats the moral foundations in this way. These foundations could very well be influenced by innate features of humanity (e.g., the existence of the binding foundations could be a consequence of the human need for social groups) but there are likely more proximal psychological features that influence individuals’ moral attitudes and judgments. We propose that the need for cognitive closure is one such feature and that it could predict beliefs that protecting groups is a moral imperative, as measured by the binding foundations.

Although there is a wide literature on the outcomes of the moral foundations, this work largely focuses on how they can predict explicit political beliefs (e.g., attitudes toward abortion; see Koleva et al. 2012). However, there is some research on how the moral foundations predict attitudes toward women. Vecina and Piñuela (2017) found a role for the moral foundations in sexist attitudes in a sample of Spanish men convicted of domestic violence; the Fairness/Reciprocity foundation negatively predicted whereas the Respect/Authority foundation positively predicted sexist attitudes. To our knowledge, there is not a wide published literature on the effects of the moral foundations on forms of prejudice; the studies we present here begin to fill this gap in the literature.

Binding Moral Foundations as Mediators

The studies we present here are based on research in two areas. First, need for cognitive closure has been found to be positively and significantly associated to the expression of group-centric attitudes and behaviors (Kruglanski et al. 2006; Makwana et al. 2017). Even more relevant for our purposes is research that has explicitly found an association between need for cognitive closure and the binding, but not the individualizing, foundations (Federico et al. 2016). Higher need for closure motivates individuals to enhance the “groupness” of their collectivity to create a firm shared reality that can serve as a base for stable knowledge; this can be manifested in endorsement of the binding moral foundations. Second, as Vecina and Piñuela (2017) found, the moral foundations can predict negative attitudes toward women.

We combined the results of these two areas of research by proposing that the binding moral foundations would mediate the association between need for cognitive closure and negative attitudes toward women leaders. Assessing the mediating role of the binding moral foundations can extend Roets et al.’s (2012) finding—that higher need for cognitive closure is associated with these types of attitudes—and consequentially advance our knowledge on why women face difficulties in leadership positions.

Conceptually, this process could work as follows: Individuals—both men and women—who desire epistemic certainty will turn to sources—for instance, the norms of the dominant culture—that can provide it. Given the accessibility of divergent stereotypes of women and leaders, men and women who are characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure should be more likely to support norms and traditions—represented by the binding foundations—which are consistent with these stereotypes and, as a result, hold stereotypical and negative attitudes toward women leaders in the workforce.

Hypotheses

From the literature we reviewed we propose that higher need for cognitive closure will be associated with more negative attitudes toward women in high status positions in the workforce and that this relationship will be observed in both men and women. Moreover, we propose that higher need for cognitive closure will be associated with more negative attitudes toward women managers (Study 1) and stereotyped beliefs that women do not want or deserve high status positions in the workforce (Study 2); we expect that that these relationships will be mediated by the binding foundations. The individualizing foundations may also predict positive attitudes toward women in leadership roles, although we do not hypothesize an explicit role for these factors in the mediational model. In other words, we expect that the association between need for cognitive closure and two forces that act against women leaders will be mediated by the binding foundations, controlling for covariates that include participants’ gender and political orientation.

Both men and women have available to them stereotypes, perceptions of gender roles, or schemas of women as incompatible with leadership roles. Not all men and women who are aware of these schemas will internalize them; instead we propose that those men and women who are characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure will be more prone to use them because they represent sources of stable—and desired—knowledge. Consequentially, we propose that they will be more likely to be concerned with maintenance of the shared reality of the dominant culture and its particular norms—represented by the binding foundations—as a form of group-centric attitudes. As a result, these individuals should also have more negative attitudes toward women leaders. In the following studies we will also control for participants’ political orientations; this control is critical because recent research (Jost and Amodio 2012) has found that need for cognitive closure is associated with right-wing political ideologies.

Study 1: Negative Attitudes toward Women Managers

Method

Participants

Fully 149 workers (Mage = 36.93, SD = 11.94, range = 19–67) recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk took part in our study. We consulted the research of Fritz and MacKinnon (2007) in order to arrive at our sample size. The majority of participants identified as male (89, 59.7%). Participants identified as White (82, 55.0%), Asian American (56, 37.6%), African American (5, 3.4%), and Latinx (4, 2.7%); 2 participants, or 1.3%, indicated their ethnic group as “Other.” The majority of participants had completed at least some university (114, 76.4%); the remainder were at least high school graduates.

Need for Cognitive Closure

Participants responded to the Revised Need for Closure Scale (Rev NfCS; Pierro and Kruglanski 2005). This scale constitutes a brief 14-item self-report instrument designed to assess stable individual differences in the need for cognitive closure (e.g., “Any solution to a problem is better than remaining in a state of uncertainty”). Participants responded to these items on 6-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree). A composite need for cognitive closure score was computed by summing across responses to each item. In the present sample, reliability of the Rev. NfCS was satisfactory (α = .85). We also conducted a Maximum Likelihood Exploratory Factor Analysis with an oblimin rotation. An investigation of the Scree Plot (see Costello and Osborne 2005) suggested that a single factor should be retained. This factor accounted for 31.6% of the extracted loadings. Thirteen of the fourteen items had factor loadings above .30; ten had loadings above .40. (These results are presented in Table 1s of the online supplement.)

Moral Foundations

Participants responded to the 30-item Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ-30; Graham et al. 2008). This questionnaire measures the five factors of morality: Harm/Care, Fairness/Reciprocity, In-group/Loyalty, Authority/Respect, and Purity/Sanctity. The MFQ-30 consists of two parts. In Part 1, participants respond to 15 items that measured the perceived relevance of different kinds of information for making moral judgments (e.g., “Whether or not someone suffered emotionally”). Participants responded to the items on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all relevant) to 5 (Extremely relevant). In Part 2, participants responded to an additional 15 items that measured agreement with statements about morality (e.g., “Compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial virtue”). Participants responded to the items on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Both Parts 1 and 2 measure each of the five moral foundations; a score for each foundation can be computed by taking the mean of all items across both parts. The Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity foundations together reflect individualizing foundations, whereas the In-group/Loyalty, Authority/Respect, and Purity/Sanctity foundations together reflect binding foundations. The internal consistency reliabilities for the aggregate individualizing (α = .78) and binding moral foundations (α = .92) were acceptable. A recent confirmatory factor analysis has supported the proposed factor structure (Davies et al. 2014).

Political Orientation

Participants responded to a single item (i.e., “How would you describe your political views?”) to assess their political orientation. They responded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (Very liberal) to 7 (Very conservative). This item was previously used by Koleva et al. (2012). The average score in the current sample was 3.27 (SD = 1.53). There was a unimodal distribution and no evidence of a noticeable skew (Skew = .121, SE = .199). We conducted a one-sample t-test which contrasted this score against the scale midpoint. Results revealed that the average political orientation score was significantly below the midpoint, t(148) = −5.83, p < .001). Consequentially, our participants tended toward being liberal.

Attitudes toward Women Leaders

Participants completed the 21-item Women As Managers Scale (WAMS; Peters et al. 1974); this scale was designed to assess the general (non)acceptance of women as managers (e.g., “The possibility of pregnancy does not make women less desirable managers than men”). Participants respond to items on a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Responses were averaged such that higher scores indicted more negative views toward women. Internal consistency reliability was high in this sample (α = .94). There is debate over the factor structure of the WAMS (Cordano et al. 2003). An issue is that the WAMS can produce multiple factors that produce more than one eigenvalue (i.e., the Kaiser criterion). However, this has been found to be an ineffective method (Costello and Osborne 2005); an investigation of the Scree Plot is a time-efficient method for factor retention. We conducted a Maximum Likelihood Exploratory Factor Analysis with an oblimin rotation; as with past research (e.g., Cordano et al. 2003) we found three factors with an eigenvalue over one. However, an investigation of the Scree Plot strongly suggested a single factor, which accounted for 50.2% of the extracted loadings. Twenty of the 21 items had factor loadings above .40, supporting our decision to used a single composite score. (These results are presented in Table 3 s of the online supplement.)

Results

Descriptive statistics, overall and for men and for women, along with correlations within participants’ gender are presented in Table 1. We first investigated any differences between men and women in the variables of interest (need for cognitive closure, the aggregate and individual binding and individualizing moral foundations, and attitudes toward women managers). We found that men had more negative attitudes toward women mangers than did women, F(1, 147) = 19.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .11 There were no other significant differences.

In order to begin testing our hypothesis we first analyzed the patterns of results from the bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics. Although we hypothesized that elevated scores on the binding foundations would serve as a mechanism for the effect of need for cognitive closure, the level of support for the individualizing foundations was higher than support for than the binding foundations. We conducted two paired samples t-tests, one each among men and women, in order to assess the significance of these differences. We found a significant difference between the scores on the binding and individualizing foundations among both men, t(88) = 6.57, p < .001, and women, t(59) = 6.42, p < .001) (see Table 1).

However, a higher need for cognitive closure was significantly associated with more negative attitudes toward women leaders among both women and men (see Table 1). Further, a higher need for cognitive closure was significantly associated with higher scores on the binding foundations among both men and women. On the other hand, the correlations between need for cognitive closure and the individualizing foundations were not significant—again among both men and women. Finally, higher scores on the binding foundations were associated with more negative attitudes toward women managers; lower scores on the individualizing foundations were instead associated with more positive attitudes toward women managers.

In order to elucidate the associations between need for cognitive closure with negative attitudes toward women leaders, we regressed these variables on need for cognitive closure, gender (contrast coded: Women = −1; Men = 1), age, and political orientation. In order to see if men and women responded in different ways, we also assessed the interaction effect of need for cognitive closure and gender. We previously standardized all variables, and the interaction term was based on this standardized score. There was a significant main effect for need for cognitive closure (β = .37, p < .001) on negative attitudes toward women leaders, controlling for all other covariates; a higher need for cognitive closure was associated with more negative attitudes. There were also significant main effects for gender (β = .33, p < .001), age (β = −.19, p = .005), and political orientation (β = .26, p < .001). Participants with a higher need for cognitive closure, men, younger participants, and those with more conservative political attitudes held more negative attitudes toward women leaders. The need for cognitive closure x gender interaction was not significant (β = .08, p = .254).

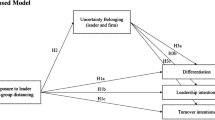

We then tested the indirect effects of need for cognitive closure on negative attitudes toward women leaders through the aggregate binding and individualizing foundations, controlling for political orientation, age, and gender. All variables were standardized prior to analysis. Results are presented in Fig. 1. This multiple mediation model was assessed through the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013), Model 4. Bias corrected confidence intervals were created with 5000 bootstrap samples. As can be seen in Fig. 1, binding and individualizing moral foundations are, respectively, positively and negatively related to (negative) attitudes toward women managers. More importantly, we found evidence for an indirect effect of need for cognitive closure on attitudes toward women managers through the aggregate binding foundations (Effect = .15, SE = .04, 95% CI [.07, .25]), but not through the individualizing foundations (Effect = −.04, SE = .03, 95% CI [−.12, .01]). The effect of need for cognitive closure remained significant—at a reduced level—after controlling for the mediators (see Fig. 1).

In light of Vecina and Piñuela’s (2017) finding that the Respect/Authority and Fairness/Reciprocity foundations were particularly important, we also conducted mediations through each aggregate and individual moral foundation, entered separately. As with the aggregate binding and individualizing foundations, there were only indirect effects through the individual binding foundations. The effects of the individual binding foundations were roughly equal: Respect/Authority (Effect = .06, SE = .02, 95% CI [.02, .15]), In-group/Loyalty (Effect = .06, SE = .02, 95% CI [.02, .15]), and Purity/Sanctity (Effect = .08, SE = .02, 95% CI [.03, .17]). However, we should note that the foundations were highly intercorrelated and had nearly identical correlations with both need for cognitive closure and attitudes toward women leaders. It is likely that none of the binding foundations had a unique relationship with either variable of interest.

Discussion

Our hypotheses that higher need for cognitive closure would be associated with more negative attitudes toward women managers and that this would be mediated by the binding foundations were supported. Of importance, we did not find evidence that there were any differences between men and women who were characterized by a higher need for closure. Although we found that the individualizing foundations predicted positive attitudes toward women managers, it was not associated with need for closure and consequentially it did not have a role in the meditational model. On the other hand, we found evidence that each of the three binding foundations also mediated the relationship between need for closure and negative attitudes toward women managers; it appears that each of these foundations helped drive the mediation model.

Study 2: Stereotyped Beliefs Toward Women

Although we were encouraged by Study 1’s results, there were limitations, and we designed a second study to test three limitations in particular. First, as with all studies, it requires replication by further research. Second, we used a different dependent variable: stereotyped beliefs that women do not want, or deserve, high status roles in the workforce. This measure is critical for our theory. Because we theorized that men and women with a higher need for closure would be more likely to hold more negative stereotypes of women, we need an actual assessment of stereotypes. As with Study 1, we expect that the binding, but not the individualizing, foundations would also mediate the effect on these beliefs. Third, we included a measure of social desirability.

Method

Participants

Fully 207 workers (Mage = 36.41, SD = 11.01, range = 19–68) recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk took part in the study. As with Study 1, we consulted Fritz and MacKinnon (2007) for our sample size. The majority of participants identified as female (121, 58.5%). Participants identified as White (148, 71.5%), Asian American (16, 7.7%), African American (24, 11.6%), and Latinx (8, 3.9%); 11 participants, or 5.3%, indicated their ethnic group as “Other.” 37 participants, or 17.7%, were current university students.

Need for Cognitive Closure, Moral Foundations, and Political Orientation

Participants responded to the same Revised Need for Closure Scale that we used in Study 1. In the present sample, reliability of the Rev. NfCS was satisfactory (α = .70). Participants responded to the same Moral Foundations Questionnaire that we used in Study 1. The internal consistency reliabilities for the aggregate individualizing (α = .73) and binding moral foundations (α = .83) were acceptable. Participants responded to a single item (i.e., “How would you describe your political views?”) that was similar to the item used in Study 1. In the present sample, participants responded on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (Very liberal) to 6 (Very conservative); this scale lacked a midpoint. The average score in the current sample was 3.18 (SD = 1.50). As with Study 1, there was a unimodal distribution and no evidence of a noticeable skew (Skew = .158, SE = .169). We conducted a one-sample t-test which contrasted this score against the scale midpoint. Results revealed that the average political orientation score was significantly below the midpoint, t(206) = −7.85, p < .001. Our participants again tended toward being liberal.

Gender Stereotyped Beliefs

Stereotyped beliefs of women as not wanting or deserving high status positions in the workforce were measured by a seven-item scale developed by McCoy and Major (2007). Similar to the WAMS used in Study 1, each statement implied that men are more suited to, and deserving of, higher status than women are (e.g., “On average, men are more likely than women to make important sacrifices to further their careers”). Items were rated on an 7-point Likert scale from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). Internal consistency reliability was adequate in our sample (α = .76). We conducted a Maximum Likelihood Exploratory Factor Analysis with an oblimin rotation. An investigation of the Scree Plot very strongly suggest a single factor. This factor explained 41.4% of the extracted loadings, and six of the seven items had factor loadings above .40. (These results are presented on the in Table 2s of the online supplement.)

Social Desirability

We used the SDS-17 (Stöber 2001) in order to assess our participants’ tendency to present themselves in an overly favorably light. The SDS-17 consists of 16 statements rated on a True/False scale (coded 1/0). Items include: “In conversations I always listen attentively and let others finish their sentences” and “Sometimes I only help because I expect something in return” (reverse scored). Internal reliability was fairly adequate in this sample (Kuder-Richardson’s coefficient = .59). Responses were summed across items such that higher scores indicate higher social desirability.

Results

As with Study 1, we first investigated any differences between men and women in the variables of interest (need for cognitive closure, the aggregate and individual binding and individualizing moral foundations, and attitudes toward women managers). We found that women had higher scores than men on the Harm/Care foundation, a member of the Individualizing Foundations, F(1, 205) = 3.98, p =. 047, ηp2 = .01 (see Table 2). There were no other significant differences.

As can be seen in Table 2, the results for men and women were fairly similar. As with Study 1, we first explored the patterns of results from the bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics. The level of support for the individualizing foundations was higher than support for the binding foundations; we conducted two paired samples t-tests, one each among men and women, in order to assess the significance of these differences. We found a significant difference between the scores on the binding and individualizing foundations among both men, t(85) = 6.71, p < .001, and women, t(120) = 8.89, p < .001).

As in Study 1, a higher need for cognitive closure was significantly associated with more stereotypes that women do not want nor deserve high status positions (see Table 2). Further, a higher need for cognitive closure was significantly associated with the binding foundations among both men and women. The correlations between need for cognitive closure and the individualizing foundations were not significant for both men and women. Higher scores on the binding foundations were associated with higher levels of these stereotypes among men, although this correlation did not reach established levels of significance among women. There was not a significant association between the individualizing foundations and these stereotypes.

As in Study 1, we first tested if men and women characterized by higher need for closure responded differently to our measure of stereotyped belief toward women. To this end, we assessed the interaction effect of need for cognitive closure and gender on gender stereotyped belief. All variables were standardized prior to our regression analysis. Controlling for all other covariates, there was a significant main effect for need for cognitive closure (β = .190, p = .005) on gender stereotyped beliefs, such that participants with a higher need for cognitive closure were more likely to have more stereotyped beliefs toward women. Again, as in Study 1, the need for cognitive closure by gender interaction was not significant (β = .094, p = .163).

We then tested the indirect effects of need for cognitive closure on stereotyped beliefs toward women through the aggregate binding and individualizing foundations, controlling for political orientation, age, gender, and social desirability. All variables were standardized prior to analysis. Results are presented in Fig. 2. As with Study 1, the multiple mediation model was assessed through the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013), Model 4 and bias corrected confidence intervals were created with 5000 bootstrap samples. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the binding, but not the individualizing, moral foundations are positively related to gender stereotyped belief. We also found evidence for an indirect effect of need for cognitive closure on gender stereotyped belief through the aggregate binding foundations (Effect = .03, SE = .01, 95% CI [.006, .08]), but not through the individualizing foundations (Effect = .005, SE = .01, 95% CI [−.007, .03]). The effect of need for cognitive closure remained significant—at a reduced effect—after controlling for the mediators (see Fig. 2). When entered separately, the aggregate binding (Effect = .029, SE = .018, 95% CI [.004, .08]) and individualizing (Effect = .004, SE = .008, 95% CI [−.005, .03]) foundations remained significant and nonsignificant, respectively. The mediated effect through each of the single binding foundations ranged from .12 to .22; as in Study 1, there was not a noticeable difference between the binding foundations.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 generally support those from Study 1, using a different measure and controlling for social desirability in addition to political orientation, gender, and age. In both Studies 1 and 2, the binding, but not the individualizing, foundations mediated the relationship between need for closure and some kind of belief and attitude toward women in the workforce. However, there were interesting differences between the results we found in Studies 1 and 2.

First, although neither study found a mediating role for the individualizing foundations, there was an effect of these foundations on the outcome in Study 1, but not in Study 2. Further research can investigate when, and why, the individualizing foundations have an effect on different types of positive attitudes and beliefs toward women. Second, the results on the mediating role of the binding foundation were weaker in Study 2. In part this could have been caused by the weaker correlations between need for cognitive closure and the binding foundations that we observed in Study 2 relative to Study 1. The correlations from Study 1 are fairly consistent with past research (Giacomantonio et al. 2017, Study 2). In this case, unexpectedly low correlations in Study 2 could be the cause of the lower effect. In addition, this could have been caused by the results among women: The correlation between the binding foundations and the gender stereotypes was not significant for women whereas it was for men. Future research can investigate if either of these explanations are generally correct.

General Discussion

We argued that that men and women who are characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure are more susceptible to the mismatch between stereotypes of women and stereotypes of leaders; consequentially, they would be more likely to hold negative attitudes toward women in leadership positions. Neither the existence of negative stereotypes about women nor the need for cognitive closure should be individually sufficient to explain the difficulties faced by women leaders. Even though these negative stereotypes exist, not everyone will accept them; there is nothing explicit in a desire for epistemic certainty that makes viewing women leaders in a negative light inevitable. Instead, we proposed that a higher need for cognitive closure makes an environment more likely in which these stereotypes, and the resulting attitudes, can be accepted and held with confidence.

Our mediation model was built on past research—on the role of need for cognitive closure on moral foundations (Federico et al. 2016) and on the role of the moral foundations on negative attitudes toward women (Vecina and Piñuela 2017)—in order to help explain the relationship between need for cognitive closure and attitudes toward women (Roets et al. 2012) and, consequentially, to help explain the difficulties faced by women leaders. We theorized that individuals characterized by a need for cognitive closure would be more likely to support binding moral foundations, which include norms of masculine leadership. Consequentially, these individuals would be more likely to hold negative attitudes women leaders, as a representation of women in nontraditional social roles. We tested this model in two studies.

Our results were consistent with our hypotheses. In Study 1, we found that higher need for cognitive closure was associated with more negative attitudes toward women leaders, controlling for participants’ gender and political orientation. Although political conservatives and men were more likely to hold negative attitudes toward women managers, we found that women and liberals could also hold these attitudes when they also had a need for cognitive closure. We also found an indirect effect of need for cognitive closure on negative attitudes through the binding foundations. This was an important finding in light of the association between need for cognitive closure and right wing political attitudes.

One issue with Study 1 is that we theorized that individuals who are characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure would be more receptive to gender stereotypes. We did not explicitly assess this linkage in Study 1, but we entered work-related gender stereotypes as the outcome in Study 2. Our results were largely the same as in Study 1: Higher need for cognitive closure was associated with more negative stereotypes toward women, controlling for participants’ gender, political orientation, and social desirability scores. As with Study 1, this association was mediated by the binding foundations. Although we did not expect the individualizing foundations—Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity—to have a role in the mediational model, we suspected that they could be negatively associated with negative attitudes toward women leaders. This suspicion was supported in Study 1, but not in Study 2. Future research can investigate how, when, and why these foundations can promote positive attitudes toward women in nontraditional roles. From these studies we thus have evidence that individuals who are characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure are more accepting of gender stereotypes and negative attitudes toward women leaders. These results cannot be explained by participants’ political orientation or their gender.

As with every significant result, there are alternative explanations for why women face difficulties in leadership roles. We will briefly go over two. According to Fiske et al.’s (Fiske et al. 2002) stereotype content model (SCM), women, like other low status groups, are judged to be warm but not competent whereas men, like other high status groups, are judged to be competent but not warm. Women who take on leadership roles—or other roles stereotypically held by men—can lose their perceived warmth. We know of no previous research that has explicitly combined need for cognitive closure with the SCM; however, as we have attempted to show, individuals with a higher need for closure can be more perceptive of these stereotypes.

Makwana et al. (2017) have recently assessed a similar model in which need for cognitive closure predicts an outcome related to gender attitudes—in their case, transphobia. They hypothesized, and found, that this association was mediated by Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA; i.e., a syndrome of submission to superior ingroup members, dominance of inferior ingroup members, and hostility to threatening outgroups; Altemeyer 1988) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO; i.e., a strong preference for ingroup enhancement at the expense of outgroups; Pratto et al. 1994). SDO and RWA, like the binding foundations, reflect positive attitudes toward dominant groups, and it is possible that we could have found similar effects if we had replaced the binding foundations with the former factors. However, we reached a slightly different conclusion. Makwana et al. argued that individuals with a higher need for closure desired stability that could be satisfied by right-wing beliefs, represented by the RWA and SDO. We agree with this point but urge caution in linking the need for closure too closely with right-wing politics. Many researchers have found this association (e.g., Graham et al. 2009; see also the correlations from Study 2 from the current research), however there is nothing explicit in the need for cognitive closure that would inevitably lead individuals to accept right-wing politics. Instead, it should lead individuals to accept any set of attitudes that can provide them with knowledge. If need for cognitive closure is associated with right-wing beliefs then we have evidence, albeit indirect, that these types of beliefs can provide stable knowledge in a sample of U.S. participants. However, we do not think that this will always be the case; there should be right-wing beliefs that do not provide stable knowledge and non-right-wing beliefs that do.

Future Directions and Limitations

Our research provides an interesting first step in the understanding of how need for cognitive closure can influence how individuals think about nontraditional “others.” Indeed, this general pattern—individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure seize and freeze upon available stereotypes and thus follow accessible norms and consequentially engage in prejudice—should hold in any context in which stereotypes are applicable to these norms. For instance, if there is a stereotype that immigrants “steal” the jobs of natives that is applicable to a norm to protect the rights of natives, then we would expect that higher need for cognitive closure would be associated with more anti-immigrant prejudice.

Our research also provides a number of intriguing future directions specific to research on attitudes toward women leaders. We argued that individuals characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure seize and freeze upon stereotypes toward women and leaders. The existence of these stereotypes was the “hidden” and unmeasured factor in Study 1 and the outcome in Study 2. If there generally exist stereotypes that negatively affect women leaders in many areas of the world, then it are these stereotypes that will be seized and frozen upon. The “groups” that provide a stable belief can vary tremendously in size: It can be represented by a culture that is spread throughout the world but it can be as small as a community or an organization. If instead a particular culture (e.g., a nation, region, community, organization) has stereotypes that positively affect women leaders, then these will instead provide the “grist” for need for cognitive closure. The measure of stereotyped beliefs we used in Study 2 is not a good instrument for this specific task: Participants could disagree with negative stereotypes of women, but this is not necessarily the same as agreeing with positive stereotypes. In this case, need for cognitive closure would act as a protective factor for positive attitudes toward women leaders. Likewise, it is possible that women leaders in stereotypically feminine fields (e.g., health care, education) could also benefit from stereotypes of women, and need for cognitive closure could enhance this effect.

Previous research also suggests two future lines of research on how anti-women leader prejudice could be reversed, even in the presence of stereotypes that negatively affect women leaders. Gordon Allport (1954) argued that negative attitudes toward an outgroup could be reversed through positive intergroup contact. If individuals seize and freeze upon stereotypes that negatively affect women leaders, then they would likely perceive women leaders as a type of outgroup. Individuals who have positive contact with women leaders may then be able to look past these stereotypes, or else form new attitudes of women leaders and/or leaders in general. This could be particularly strong among individuals characterized by need for cognitive closure, especially so if they are in the seizing phase. Similarly, Echterhoff et al. (2017) found that although individuals typically form shared realities with members of their own ingroup, they also can form shared realities with outgroup members when they are viewed as epistemic authorities. If individuals characterized by a need for cognitive closure view women leaders as epistemic authorities on a topic that is relevant to their leadership, then they could form a shared reality with them and, consequentially, come to hold positive attitudes toward women leaders. In both cases, need for cognitive closure shifts from a risk factor to a protective factor. For there to be transformational effects from either positive intergroup contact or shared realities it is necessary that individuals not limit their positive attitude to one particular women leader, but instead use this information to shape how they generally view women leaders.

Our research also had a number of limitations that can be addressed in future research. The strength of our conclusions is limited by the correlational nature of our methods. Although there are not reliable standardized methods to experimentally induce the moral foundation, there are such methods for need for cognitive closure (see Kruglanski 1996b, p. 269). Using these methods would help demonstrate that there is a causal path that originates from need for cognitive closure and that could lead to interventions to improve individuals’ attitudes toward women leaders.

Other limitations include the specific variables we included in our models. Although we focused on attitudes toward women leaders in the workforce, we expect that this result should hold in other leadership domains. For instance, women are on the receiving end of stereotypes and prejudice in the political arena (Sensales et al. 2018). In addition, we found only a partial mediation effect in both studies, so there are clearly other factors at play which should be investigated in future research.

Participants from both studies were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk; this allowed us to recruit a sample that is more diverse, in at least age, relative to a university student sample. Our participants, in both studies, were also fairly diverse in their political orientation. We do not think it is very likely that our women participants typically perceive women leaders as representatives of an outgroup. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out this possibility and future research can explore this topic. Additionally, although the combined sample was fairly large, each individual sample could have been larger. This is particularly necessary considering that this specific model has not yet been tested.

Finally, Bastian and Haslam (2006) found that essentialist beliefs (i.e., beliefs that individuals’ personal characteristics are biological, stable, and clearly defined) predicted an aggregate measure of stereotype acceptance. They did not find an effect of need for cognitive closure on their stereotype measures. Future research can assess the role of essentialist beliefs on specific stereotypes with other measures of need for cognitive closure.

Practice Implications

There are at least two major practice implications from our results: the identification of at-risk situations for women leaders and suggestions for how these attitudes can be reversed. First, the need for cognitive closure can be represented as both an individual difference and as an outcome of specific environments (e.g., time pressure). High-pressure environments can induce this need, even if the individuals in these environments are not typically characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure. These types of environments should be a particular concern for anyone who is interested in the status of women leaders. Second, individuals who are chronically or acutely characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure desire stable knowledge, and they will support sources that can provide it. If these sources maintain that women are unsuitable for leadership positions, then they are more likely to hold negative attitudes toward women. If these sources instead maintain that women and leadership roles are compatible, then need for cognitive closure could shift from a risk factor into a protective factor. These sources of knowledge can be as small as a local organization and can represent a good target for attitude change.

Conclusions

In our research, we assessed the roles of need for cognitive closure, or the desire for epistemic certainty, and the binding moral foundations, or the concern for the maintenance of dominant groups, on two different outcomes related to negative attitudes toward of women leaders. In Study 1, we found an indirect effect of need for cognitive closure, through the binding foundations, on negative attitudes toward women managers; in Study 2, we found evidence for a similar model in which acceptance of stereotypes of women as not wanting or not deserving leadership positions was entered as the outcome. There was no evidence for a difference between men and women. Conceptually, we expect that both men and women who are characterized by a higher need for cognitive closure to be more likely to accept the norms and standards of the dominant culture—which still include norms of masculine leadership—because this is a source of stable knowledge. Partially as a result of this process, these individuals are more likely to have negative views of women leaders.

References

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Baker, C. (2014). Stereotyping and women's roles in leadership positions. Industrial and Commercial Training, 46(6), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-04-2014-0020.

Baldner, C., Pierro, A., Chernikova, M., & Kruglanski, A. W. (in press). When and why do liberals and conservatives think alike? An investigation into need for cognitive closure, the binding moral foundations, and political perception. Social Psychology.

Bastian, B., & Haslam, N. (2006). Psychological essentialism and stereotype endorsement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(2), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.03.003.

Brooks, J. (2017). Four women leaders share thoughts on gender and security. Retrieved from https://www.dvidshub.net/news/236338/four-women-leaders-share-thoughts-gender-and-security.

Cordano, M., Scherer, R. F., & Owen, C. L. (2003). Dimensionality of the women as managers scale: Factor congruency among three samples. The Journal of Social Psychology, 143(1), 141–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309598436.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9.

Davies, C. L., Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis of the moral foundations questionnaire: Independent scale validation in a New Zealand sample. Social Psychology, 45(6), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000201.

Dijksterhuis, A. P., Van Knippenberg, A. D., Kruglanski, A. W., & Schaper, C. (1996). Motivated social cognition: Need for closure effects on memory and judgment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32(3), 254–270. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1996.0012.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.109.3.573.

Echterhoff, G., Kopietz, R., & Higgins, E. T. (2017). Shared reality in intergroup communication: Increasing the epistemic authority of an out-group audience. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(6), 806–825. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000289.

Federico, C. M., Ekstrom, P., Tagar, M. R., & Williams, A. L. (2016). Epistemic motivation and the structure of moral intuition: Dispositional need for closure as a predictor of individualizing and binding morality. European Journal of Personality, 30(3), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2055.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878.

Fiske, S. T., Xu, J., Cuddy, A. C., & Glick, P. (1999). (dis) respecting versus (dis) liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00128.

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x.

Giacomantonio, M., Pierro, A., Baldner, C., & Kruglanski, A. (2017). Need for closure, torture, and punishment motivations. Social Psychology, 48(6), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000321.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2008). The moral foundations questionnaire. Retrieved from http://MoralFoundations.org.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015141.

Graham, L. (2017). Women take up just 9 percent of senior IT leadership roles, survey finds. CNBC.com. Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/22/women-take-up-just-9-percent-of-senior-it-leadership-roles-survey-finds.html.

Gray, K., & Schein, C. (2012). Two minds vs. two philosophies: Mind perception defines morality and dissolves the debate between deontology and utilitarianism. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 3, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-012-0112-5.

Gray, K., Schein, C., & Ward, A. F. (2014). The myth of harmless wrongs in moral cognition: Automatic dyadic completion from sin to suffering. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 1600–1615. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036149.

Güney, S., Gohar, R., Akıncı, S. K., & Akıncı, M. M. (2013). Attitudes toward women managers in Turkey and Pakistan. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-015-1903-5.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z.

Haines, E. L., Deaux, K., & Lofaro, N. (2016). The times they are a-changing… or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983–2014. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316634081.

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How five sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In P. Carruthers, S. Laurence, & S. Stich (Eds.), The innate mind (Vol. 3, pp. 367–391). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Javalgi, R. R. G., Scherer, R., Sánchez, C., Pradenas Rojas, L., Parada Daza, V., Hwang, C. E., & Yan, W. (2011). A comparative analysis of the attitudes toward women managers in China, Chile, and the USA. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 6(3), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/17468801111144067.

Jost, J. T., & Amodio, D. M. (2012). Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence. Motivation and Emotion, 36(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9260-7.

Jost, J. T., Kruglanski, A. W., & Simon, L. (1999). Effects of epistemic motivation on conservatism, intolerance and other system-justifying attitudes. In L. L. Thompson, J. M. Levine, & D. M. Messnick (Eds.), Shared cognition in organizations: The management of knowledge (pp. 91–116). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023557.

Koleva, S. P., Graham, J., Iyer, R., Ditto, P. H., & Haidt, J. (2012). Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.006.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1996a). Motivated social cognition: Principles of the interface. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 493–520). New York: Guilford Press.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1996b). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychological Review, 103(2), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.2.263.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: '“Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychological Review, 103, 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.2.263.

Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., Mannetti, L., & De Grada, E. (2006). Groups as epistemic providers: Need for closure and the unfolding of group-centrism. Psychological Review, 113(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.84.

Livi, S., Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., Mannetti, L., & Kenny, D. A. (2015). Epistemic motivation and perpetuation of group culture: Effects of need for cognitive closure on trans-generational norm transmission. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 129, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.09.010.

Makwana, A. P., Dhont, K., Akhlaghi-Ghaffarokh, P., Masure, M., & Roets, A. (2017). The motivated cognitive basis of transphobia: The roles of right-wing ideologies and gender role beliefs. Sex Roles, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0860-x.

Marcus, G. (2004). The birth of the mind. New York: Basic Books.

McCoy, S. K., & Major, B. (2007). Priming meritocracy and the psychological justification of inequality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.04.009.

McKinsey & Company. (2016). Women in the workplace 2016. San Francisco, CA: Author. Retrieved from https://womenintheworkplace.com.

Peters, L. H., Terborg, J. R., & Taynor, J. (1974). Women as managers scale (WAMS): A measure of attitudes towards women in management positions. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 2, 66 (Ms. no. 153).

Pierro, A., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2005). Revised need for Cognitive Closure Scale (unpublished manuscript). Università di Roma La Sapienza, Roma, Italia.

Pierro, A., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2008). “Seizing and freezing” on a significant-person schema: Need for closure and the transference effect in social judgment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(11), 1492–1503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208322865.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741.

Roets, A., Kruglanski, A. W., Kossowska, M., Pierro, A., & Hong, Y. Y. (2015). The motivated gatekeeper of our minds: New directions in need for closure theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 221–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.01.001.

Roets, A., & Van Hiel, A. (2011). Allport’s prejudiced personality today: Need for closure as the motivated cognitive basis of prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(6), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411424894.

Roets, A., Van Hiel, A., & Dhont, K. (2012). Is sexism a gender issue? A motivated social cognition perspective on men's and women's sexist attitudes toward own and other gender. European Journal of Personality, 26(3), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.843.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Perspective gender stereotypes and backlash towards agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00239.

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Nauts, S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 48(1), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2011.10.008.

Schein, V. E. (1975). Relationships between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among female managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076637.

Sensales, G., Areni, A., & Baldner, C. (2018). Politics and gender issues: At the crossroads of sexism in language and attitudes. An overview of some Italian studies. In G. Sáez Díaz (Ed.), Sexism: Past, present and future perspectives. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Stöber, J. (2001). The social desirability Scale-17 (SDS-17): Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and relationship with age. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.17.3.222.

Van Leeuwen, F., & Park, J. H. (2009). Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 169–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.017.

Vecina, M. L., & Piñuela, R. (2017). Relationships between ambivalent sexism and the five moral foundations in domestic violence: Is it a matter of fairness and authority? The Journal of Psychology, 151(3), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1289145.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors did not use any external funding sources, nor did they have any conflicts of interest to report. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 33.3 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baldner, C., Pierro, A. The Trials of Women Leaders in the Workforce: How a Need for Cognitive Closure can Influence Acceptance of Harmful Gender Stereotypes. Sex Roles 80, 565–577 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0953-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0953-1