Abstract

In a 2015 contribution to Sex Roles’s Feminist Forum, Bay-Cheng argued that contemporary social evaluations of young women hinge not only on their apparent adherence to gendered moralist norms of sexual activity, but also on their performance of a neoliberal script of sexual agency. We used a mixed method approach to test this proposal, specifically its alignment with the evaluative dimensions of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM; Fiske 2013). We asked 186 U.S. adults (aged 19–64) to imagine four “sexual types” of young heterosexual women: sexually active and agentic Agents; sexually abstinent and agentic Virgins; sexually active but not agentic Sluts; and Losers, who are sexually abstinent and not agentic. Qualitative analysis of open-ended responses and quantitative analysis of personality attribute ratings indicated that participants evaluated the types differently and in ways that often mapped onto the SCM. We also conducted post-hoc inductive thematic analysis of the qualitative data, finding meaningful differences among participants’ impressions of the types in relation to their sociability, femininity, and vulnerability. Alongside signs of progress toward the affirmation of young women’s sexual agency, we also found that social evaluations of young women continue to hinge on their sexuality and traditionally gendered norms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

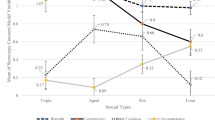

Sexual agency figures prominently in contemporary depictions and discussions of young women’s sexuality, whether in seemingly unfettered sexual self-expression or conscious celibacy (see Fahs and McClelland 2016; Lamb and Peterson 2012). In 2015, Bay-Cheng (2015a, b) proposed that young women’s performance of sexual agency has emerged as a critical metric in appraisals of them. She argued that an Agency Line measuring young women’s apparent control over their sexual experiences now joined the long-standing Virgin-Slut Continuum, which differentiates young women based on their supposed sexual behavior (i.e., ranging from abstinence to activity). The intersection of these evaluative dimensions created a matrix with four different “sexual types” of young women occupying its quadrants (see Fig. 1): sexually active Agents and agentically abstinent Virgins sit above the Agency Line (and on opposite ends of the Virgin-Slut Continuum), whereas involuntarily abstinent Losers and uncontrollably sexual Sluts fall below it. Although Bay-Cheng (2015a) identified these dimensions and resulting sexual types by reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, her proposal did not include tests of the model’s salience and validity. Our aim in the current mixed method study was to take an initial step in this direction by examining U.S. adults’ perceptions of young heterosexual women at different intersections of sexual activity and sexual agency, specifically whether they see them as characteristically distinct types and whether they feel differently about those types.

Virgin-Slut Continuum x Agency Line (Bay-Cheng 2015a)

A crucial point is that the model was not meant to capture young women’s actual or felt sexual agency. Just as others place young women on the Virgin-Slut Continuum according to claims and speculation, the position of young women in relation to the Agency Line is based on perception and performance of a neoliberal script of agency (Bay-Cheng 2015b). In this sense, neoliberal agency functions as an injunctive or prescriptive norm. In keeping with the premise of sexual scripts theory that cultural scenarios exist as master narratives rather than as reflections of actual sexual interactions (Gagnon and Simon 1973/Gagnon and Simon 2005; Simon and Gagnon 1986), the sexual types occupying the model’s quadrants and to which we refer in the current study should be understood as cultural figments or caricatures, not labels subsuming actual young women or their lived experiences. We use the designations of “Slut” and “Loser” to echo popular discourse and to draw attention to these as stigmatized statuses. Loser, in particular, incisively evokes both the common framing of sexual interactions as a game (e.g., “scoring,” “players”) and the competitive injunction at the core of neoliberalism. It has also gained rhetorical traction and potency in the United States since the popular ascendancy of Donald Trump (Estepa 2017). “Agent” and “Virgin” are less blatantly derogatory terms, but we are no less critical of them and their foundation in neoliberal ideology and gendered moralism.

Casting Young Women into Sexual Types

An irony of dominant constructions of female sexuality is that even though women are supposed to have relatively insignificant sexual drives, their sexual behavior carries significant weight in assessments of their character and worth. The imagined virtue of virgins and deviance of sluts are assumed to be proxies for qualities beyond the sexual domain (Valenti 2010). Gendered sexual statuses are also thoroughly raced and classed, meant to reflect and reinforce one’s location in existing social hierarches. “Slut,” for instance, takes on different inflections depending on its target (e.g., animalistic African American women; hot-blooded Latinas; exotic Asian American women; immoral and “trashy” low-income women; Armstrong et al. 2014; Attwood 2007; Bettie 2014; Fasula et al. 2014; García 2009; Reid and Bing 2000; Stephens and Phillips 2003), just as “virgin” conjures images of White, blonde, healthy, and well-groomed (i.e., affluent) young women.

The treatment of a young woman’s sexuality as a totalizing feature of her personhood is a cornerstone of Bay-Cheng’s (2015a) proposed matrix and the four sexual types occupying its quadrants. Agentic young women, whether sexually active Agents or sexually abstinent Virgins, are unified by their presumed savvy as well as their self-focused and strategic approaches to sexuality. Their experiences are conscious and self-determined, and they remain in unfailing control of themselves and their situations. Just as sexually active Agents’ consent is read as enthusiastically self-serving rather than an other-pleasing concession, agentically abstinent Virgins’ refusal should not be taken for meekness or subordination to others (e.g., religious and/or parental prohibitions). Instead, their abstinence is as much a product of independent, willful, and self-promoting calculations as Agents’ sexual activity is.

According to Bay-Cheng’s (2015a) summary, those below the Agency Line are typified by their deficiencies in assertiveness, self-discipline, independence, savvy, and control (over themselves, others, their circumstances, or some combination thereof). Losers may be either too socially inept or sexually undesirable to attract opportunities for sexual relationships or interactions. Therefore, their abstinence is a matter of circumstance rather than choice. Contemporary studies of young women’s sexual stigmatization indicate that “slut” is deployed as a slur not against young women who are simply sexually active, but against those whose sexual presentation (regardless of actual partnered behaviors) is interpreted as impulsive, reactive, or indiscriminate rather than strategic, self-determined, and discerning (Charles 2010; Farvid et al. 2017; Miller 2016; Wilkins and Miller 2017). Given the alignment of sexual stigmatization with racist and classist inferences about hypersexuality and/or immorality, racially and/or socioeconomically marginalized young women are especially prone to being cast as Sluts (Armstrong et al. 2014; Attwood 2007; Bettie 2014; Stephens and Phillips 2003). A Slut’s sexual activity leaves her at the wrong ends of both the moralist Virgin-Slut Continuum and the neoliberal Agency Line. As in the case of the Agents and Virgins above the Agency Line, appraisal as a Slut has wider characterological implications. Sluts’ lack of control manifests in domains beyond sexual relationships, including excessive drinking (Griffin et al. 2013) and insufficient ambition, self-regard, and even personal hygiene (Armstrong et al. 2014; Miller 2016; Wilkins and Miller 2017). In her formulation of the Agency Matrix and its attendant types, Bay-Cheng also speculated that Losers and Sluts, both unable to control themselves or their circumstances, were likely seen as victims-to-be: vulnerable to their own poor judgment and to others’ exploitative behavior.

Sexual Types and the Stereotype Content Model

In introducing the Agency Line and its consequent matrix, Bay-Cheng (2015a) alluded to its alignment with Fiske and colleagues’ (Cuddy et al. 2008; Fiske 2013; Fiske et al. 2002) studies of dehumanization and their formulation of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM). The SCM posits that individuals continually and universally assess others along two dimensions: (a) competence and (b) warmth. Evaluations of competence allow us to gauge how effective and beneficial someone might be as an ally whereas evaluations of warmth pertain to whether and to what degree someone poses a threat. These two dimensions intersect to create four quadrants into which we group and respond affectively to others. First are those we like and respect, whom we see as members of an appealing and competent in-group and who elicit feelings of affinity and shared pride (i.e., the beloved). Agentically abstinent Virgins meet these criteria: young women who are likable and non-threatening (given their adherence to accepted gendered sexual conventions) and whose abstinence we admire as a sign of control and discipline.

In contrast, constituents of the other three quadrants are all dehumanized as insufficiently competent, likable, or both. For example, studies of the SCM find that Asian Americans, wealthy White Americans (i.e., WASPs), and feminists are often regarded as highly competent yet unappealing—a combination that produces feelings of envy or resentment (Cuddy et al. 2008; Fiske 2013; Fiske et al. 2002). Those who are begrudgingly or coolly respected might be acknowledged for their achievements but nevertheless disliked (e.g., perceptions of Hillary Clinton as skillful but not relatable). Falling into this quadrant may be sexually active Agents, young women acknowledged as in control and powerful (perhaps even empowered), but who do not engender feelings of warmth. As Ringrose and Walkerdine (2007, p. 13) pointed out, “the successful but mean supergirl” may be capable, but she is neither perceived as caring nor particularly cared for.

Occupying the likable but incompetent quadrant of the SCM are individuals and groups whom we pity as harmlessly inept (e.g., people who are young, elderly, or with certain disabilities). This echoes the condescension toward young women who are virgins by circumstance rather than choice (i.e., Losers), unable to attract men’s attention and pitied as a result (e.g., those deemed “little girls” and “invisible ones” by adolescent women participating in Bay-Cheng et al.’s 2011, focus groups). SCM-based research highlights how presumptions of passivity, compliance, and innocence are requisite elements of the warmth directed toward this quadrant. As Fiske (2013, p. 61) noted in her summary of related research: “…pity is not entirely benign, as it depends on the pitied person remaining low status and incompetent, not high status, autonomous, and agentic.” Those who are seen as somehow at fault or deserving of their low status or who contest their subordination (e.g., older adults who do not cede positions and resources to younger individuals; disability rights activists) evoke cool rather than warm feelings, moving them from being pitied to being either resented (as described previously) or disdained (as described in the following).

Last and least in the SCM’s formulation of dehumanization are those considered neither competent nor likable and who elicit feelings of disgust and contempt (Fiske 2013). Studies of the SCM show African Americans and homeless individuals to be two of the groups often cast into this irredeemable category of the disdained. The intensity and depth of this dehumanizing contempt has been borne out across multiple studies. Those deemed incompetent and unlikable are perceived as lacking the emotional and mental capacities of other humans and, in brain imaging studies, are less likely to be registered, neurologically speaking, in the same way that other humans are (for reviews and details of relevant studies, see Fiske 2013; Haslam and Loughnan 2014). The figure of the Slut falls squarely into this unequivocally reviled group as young women who lack discipline and control (over themselves and their circumstances) and whose licentiousness poses a threat to others, especially women who abide by gendered and moralist sexual codes.

Although we frame sexual typecasting of young women as a form of gender policing and widespread hegemonic practice, it is also possible that some individuals and groups engage in it more than others do. Indeed, gender and sexual norms are hardly static or uniformly endorsed (Petersen and Hyde 2010; Wilke and Saad 2013). Bay-Cheng (2015a) speculated about a possible cohort effect: that younger adults, who had grown up with popular discourse saturated by neoliberal ideology, may be more inclined to rely on neoliberal conceptions of agency in evaluating women’s sexuality. (For a theoretical framing of the impact of social context and discourse on development, see Stewart and Healy 1989.) Taking the endorsement of a sexual double standard as an analogous example, some studies find evidence of gender differences. In some cases, men have been found to impose a sexual double standard more often (Milhausen and Herold 2001) whereas others have found the opposite, with women judging other women more harshly than men (Jonason and Marks 2009; for a review, see Sakaluk and Milhausen 2012). Studies of slut-shaming of young women by other women show that it serves multiple purposes, whether shoring up group boundaries (e.g., class distinctions; Armstrong et al. 2014), defending against other stigma (e.g., homophobia; Payne 2010), or boosting one’s standing or sense of self (Farvid et al. 2017; Miller 2016). Given the complex and contested literature regarding how men and women enforce gendered sexual norms, we planned to explore gender differences in participants’ views of different sexual types but without posing a priori hypotheses.

Overview of the Current Study

We conducted a mixed method study to examine if different sexual types of young women are imagined and distinguished from one another as Bay-Cheng (2015a) suggested. We hoped this initial study would stake out ground for further study and understanding. We focused our analyses on the parallels to the SCM, posing three hypotheses. First, we expected participants to evaluate the four types according to the SCM dimensions of competence and warmth, with Virgins being predominantly beloved, Agents coolly respected, Losers pitied, and Sluts disdained (Hypothesis 1; we also tested for possible age and gender effects). Second, we expected participants to attribute characteristics to the four types of young women in ways that conform to the SCM categories (Hypothesis 2; we again tested for possible age and gender effects). Finally, we studied participants’ open-ended responses to gain a fuller picture of how participants imagined the four types beyond the SCM dimensions. Given the exploratory nature of this, we operated with a general hypothesis that inductive thematic analysis will reveal underlying thematic connections and distinctions among participants’ descriptions of the four types (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Participants

Participants were 186 U.S. adults between the ages of 19 and 64 (M = 34.32, SD = 9.76). A majority (106; 57%) of participants were women, 78 (42%) were men, one (.5%) was transgender, and one (.5%) declined to select a gender identity. The sample was predominantly White (146; 78.5%). Among the racial minorities, 14 (7.5%) participants identified as Black, 14 (7.5%) as Asian American, seven (4%) as Latina/o, four (2%) as multiracial, and one (.5%) identified as Native American. Fully 159 (86%) participants identified as heterosexual, 17 (9%) as bisexual, six (3%) as gay or lesbian, two (1%) as queer, one (.5%) as questioning, and one (.5%) declined to select a sexual identity. Most participants had pursued post-secondary education: 83 (45%) had earned at least a Bachelor’s degree and another 53 (28.5%) had some college education. Participants reported a median income between $40,000 and $49,000 (range = less than $20,000/year–$200,000/year or more).

Procedure and Measures

We recruited participants through the crowdsource labor service, Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). To be eligible, “Turkers” must have been at least 18-years-old, U.S. residents, and have a minimum 98% approval rating for previously completed MTurk assignments, as recommended for social science research (Berinsky et al. 2012). The recruitment post on MTurk described the study as an anonymous online survey about norms and attitudes regarding young women’s sexuality that would take approximately 20 min to complete and for which participants would be paid $3 through the MTurk system. Those interested could follow a link to the consent and survey on Survey Monkey. Fully 292 Turkers consented and began the survey; 186 (64%) provided complete data.

Sexual Type Profiles

We asked participants to imagine and characterize four hypothetical young women, each exemplifying one of the four intersections of sexual activity and sexual agency proposed by Bay-Cheng (2015a): Agents; Virgins; Sluts; and Losers. After providing demographic information about themselves, we introduced this task to participants through the following preface:

Next, you’ll be asked about four different sexual “types” of young women. Think of them all as heterosexual and in their early 20s. We’ll provide just a few other pieces of information for each and then ask you to imagine and fill in details about what you think of each of them and how they are perceived by others. There are no right or wrong answers. We’re trying to understand whether ideas and norms about young women’s sexuality are changing and your responses will help us with this.

Participants were then shown one of the four types below. Each type was identified by a letter and defined as follows (boldface in original):

“Young Woman C is sexually experienced: she has been sexual with different partners, not only in long-term romantic relationships. She is also sexually autonomous: she seems in charge and in control of her sexual experiences.” [Agent]

“Young Woman M is sexually inexperienced: she has not had any kind of sex (oral, anal, or vaginal) with a partner. She is also sexually autonomous: she seems in charge and in control of her sexual experiences.” [Virgin]

“Young Woman T is sexually experienced: she has been sexual with different partners, not only in long-term romantic relationships. She is not very sexually autonomous: she does not seem to be in charge and in control of her sexual experiences.” [Slut]

“Young Woman Z is sexually inexperienced: she has not any kind of sex (oral, anal, or vaginal) with a partner. She is not very sexually autonomous: she does not seem to be in charge and in control of her sexual experiences.” [Loser]

Following the description of a particular type, participants were prompted to: (a) give her a name; (b) describe her personality; (c) describe “how she acts when it comes to sex and relationships”; (d) paste hyperlinks to publicly available, non-pornographic online images of what the woman might look like; and (e) share “other ideas or impressions” about the specified type.

Participants then rated the young woman described using semantic differential items. These consisted of 20 bipolar pairs of characteristics (listed in Table 1) selected by the first author based on methods used in other semantic differential studies (Beckmeyer et al. 2017; Kervyn et al. 2013; Pierce et al. 2003). Participants rated the type on a 5-point scale according to which of the two adjectives was most fitting and to what degree. For example, response options for the semantic differential item, “Is she seen as more ambitious or unmotivated?,” ranged from 1 (she’s seen much more as ambitious), through 2 (she’s seen more as ambitious), 3 (she’s seen as in between ambitious and unmotivated), 4 (she’s seen more as unmotivated), to 5 (she’s seen much more as unmotivated). The valence of the pairs varied such that the more socially desirable of the characteristics alternated between the left or right anchor. For analyses, we recoded the semantic differential pairs so that higher scores corresponded to socially desirable characteristics.

The prompts for descriptions and images and the set of semantic differential items were repeated for each of the remaining three types. In order to reduce order effects, we randomized the sequence in which the types were presented to each participant as well as the listing of the separate semantic differential items.

Analysis Strategy

Hypothesis 1

We tested our first hypothesis through a content analysis of participants’ descriptions of the four sexual types of young women. All of a participant’s open-ended responses regarding an imagined young woman (i.e., her personality, her sexual/relationship conduct, and any additional comments) were considered together as a single unit of data. We followed a multi-stage analytic process to bolster the credibility of the findings. This began with defining a priori codes based on the SCM dimensions of competence and warmth. Each unit of data was assigned one code based on the type’s perceived competence (Yes, competent; No, incompetent; or Indeterminable competence) and a second code based on whether the type was regarded with warmth (Yes, warm; No, cool; or Indeterminable warmth). The two authors separately reviewed all data using the original draft of the codebook. This initial round of coding yielded 75% agreement. The two authors conferred to refine code definitions and distinctions and revise the codebook accordingly.

As a second step, we invited a postdoctoral qualitative researcher in the field of feminist and critical sexuality studies to serve as an auditor. She was unaware of the study’s design, objectives, and hypotheses and only had access to the open-ended data submitted for coding. Using the revised codebook, the auditor and two coauthors separately coded a random sample of 11% of the data for each type (i.e., data from 20 participants × 4 sexual types = 80 units of data). The three coders (i.e., the two authors and the auditor) convened to discuss discrepancies and to clarify coding rules and definitions. The first author integrated these revisions into the final codebook (see Table 1 for code definitions, categories, and examples). The three coders used this codebook to analyze another 13% of the data for each type (i.e., 25 participants × 4 sexual types = 100 units of data). The first author computed interrater reliability on this subset of finalized codes using Krippendorff’s alpha (Kalpha; Hayes and Krippendorff 2007); Kalphas for competence and for warmth within each type all exceeded .86.

The two authors each coded separate halves of the full dataset using the final codebook. As a final code check, the auditor coded a random subset of 20% of the data coded by the first author and 20% of the data coded by the second author. The auditor’s codes were compared with those of the authors to verify that codes had been applied consistently and without apparent bias over the course of analysis. Calculated Kalpha statistics on this random sample of final codes were all above .83.

Codes were used to categorize each type description into one of the SCM quadrants: a type was categorized as beloved if the attendant description of her indicated both competence and warmth; a type was categorized as respected if she was regarded as competent but also coolly; a type was categorized pitied if she was regarded as incompetent but with warmth; and finally, a type was categorized as disdained if she was described as incompetent and regarded coolly (i.e., neither competent nor warm). Responses coded as “indeterminable” with regard to competence or warmth, 219 (29.2%) in total, were not categorized into the SCM quadrants. We used Chi-square tests to identify significant differences in the SCM category frequencies among the four sexual types. In separate analyses, we also tested for differences according to participants’ age and participants’ gender.

Hypothesis 2

We initiated quantitative analysis of Hypothesis 2 with an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the semantic differential items to identify latent constructs and to create parsimonious, conceptually coherent factors. We used these factors in repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) to identify differences among the four sexual types’ imagined characteristics. We also explored possible interaction effects of sexual type with participants’ age and participants’ gender, respectively.

Hypothesis 3

We expected to find thematic differences among participants’ descriptions of the four sexual types, however, we did not identify themes a priori. In contrast to the theoretically-driven content analysis of Hypothesis 1, the two authors inductively explored the open-ended data (Braun and Clarke 2006). We initiated our thematic analysis by individually noting recurrent and/or outstanding themes in the data, including key phrases and words. After discussing our respective observations, the first author developed an overarching code scheme based on the themes we agreed were most salient. We both separately reviewed the dataset again using the codebook, discussing all discrepancies until reaching consensus.

Results

Hypothesis 1

Hypothesis 1 predicted that participants’ evaluations of the four types will correspond with the SCM. A priori theoretical coding of participants’ open-ended descriptions of each type generally confirmed our hypothesis regarding the categorization of the four sexual types according to the SCM’s intersection of competence and warmth. A Chi-square test on the 527 units of codeable data indicated significant differences among the frequencies (see Table 2). The largest proportion of those categorized as beloved (i.e., high warmth and competence) were Virgins, whom participants depicted as equally strong and endearing (e.g., “[Susan] is confident, outgoing and athletic. She is socially connected and has strong, authentic relationships with friends and family”; “[Wendy] knows what she wants but isn’t super aggressive, she is very stable and level-headed, sweet but not naïve”). The largest proportion of those who were coolly respected (i.e., low warmth, high competence) were Agents. A participant’s description of “Naomi” captures this ambivalence: “Hot and she is confident, she is beautiful, and likes to be in the center of everything. She knows what she likes and she always asks for what she likes. She is self-centered.” Losers formed the largest proportion of the pitied (i.e., high warmth, low competence; e.g., “[Ludia] is a quiet and timid woman who is still searching to find herself. She lacks self-confidence in areas that she feels she will be a failure, even though she is smart and caring.”). Sluts formed the largest proportion of the disdained (i.e., low warmth, low competence), such as “Stacy”: “She is reckless and wild, often drinking and doing drugs to excess and not caring about the consequences. She is not good at maintaining her friendships or family ties.”

The crosstabulated data also showed patterns that did not simply or unequivocally confirm our hypothesis. For instance, although Agents were the largest proportion of those falling into the respected SCM quadrant (i.e., over 60%), reading the tabular data by columns shows that the majority of participants (98; 70%) regarded Agents as both warm and competent (i.e., beloved). This frequency is close to the frequency of Virgins categorized as beloved (98 compared to 106). Furthermore, Sluts composed the largest proportion of those categorized as disdained, but almost half of the participants (58; 46.4%) described them in sympathetic, pitying terms. For example, one participant described “Amy” as doing “what’s expected and what men want, not necessarily what she wants,” and then added, “I worry about her.”

We conducted a series of ANOVA for the SCM categorizations of Agents, Virgins, Sluts, and Losers to identify differences based on participant age; all tests were non-significant. We also examined possible gender effects. We excluded two participants from these analyses: one who identified as transgender and one who declined to select a gender. Chi-square tests of participants’ gender by SCM categorization of the sexual types were all non-significant.

Hypothesis 2

Hypothesis 2 predicted that participants will attribute distinct characteristics to the four sexual types. To analyze the quantitative ratings, we opted to first reduce the data through exploratory factor analysis. (Readers interested in analyses of the individual attributes can find a summary of these results, presented in text, Table 1s, and Fig. 1s, in the online supplement.) We first used exploratory factor analysis as a data reduction technique. We conducted separate analyses for each of the four sexual types to determine the factor structures underlying the 20 semantic differential items. We used principal axis factoring with direct oblimin rotation. For each type, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was above .90 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < .001. We compared two- and three-factor solutions. For each type, the scree plots had distinct elbows at the third factor. The three factors were conceptually consistent across the types, interpretable, and aligned with other results and theoretical models, including Kervyn et al.’s (2013) examination of the SCM and Osgood et al.’s (1957) classic semantic differential dimensions of evaluation, potency, and activity. The three factors had eigenvalues over 1.0 among the Virgins and Losers. However, eigenvalues for the third factors among Agents and Sluts were .95 and .97, respectively. Despite being slightly lower than the conventional cutoff of 1.0 (as per the Kaiser criterion; Kaiser 1960), we judged there to be empirically sufficient and conceptually compelling grounds to proceed with a three-factor solution.

Table 3 shows the factor loadings for each sexual type and the percent of variance explained by each factor. The three factors accounted for a total of 61.75% of the variance among Agents, 61.00% among Virgins; 64.03% among Sluts; and 64.04% among Losers. An adjective was included on a factor if its loading was greater or equal to .50. In the interest of using consistent factors across each type in analyses, we created composite variables for each factor based only on those items that loaded across each of the types. Potency consisted of four items (confident, strong, active, and powerful) with Cronbach’s alphas between .82 (Agents) and .88 (Losers). Competence was also formed using four items (ambitious, hardworking, successful, capable), resembled Osgood et al.’s (1957) “activity” semantic differential dimension, and had Cronbach’s alphas ranging between .83 (Virgins) and .87 (Losers). The third factor, Warmth, aligned with the “evaluation” dimension of other semantic differential studies. It comprised only two items: thoughtful and caring. We evaluated internal consistency using the Spearman-Brown coefficient, which ranged from .76 (Agents and Losers) to .82 (Virgins).

Next, we used these three factors in separate repeated-measures ANOVA to formally test Hypothesis 2. As detailed in Table 4, analyses indicated significant differences among the sexual types. Agents were assigned the highest ratings of potency, followed by Virgins. Participants assigned Sluts and Losers comparably low ratings on potency. The factors of competence and warmth bear particular relevance to the hypothesized relation to the SCM. We found significant differences among all the types on ratings of competence, with Virgins rated as most competent, followed in descending order by Agents, Losers, and Sluts. Virgins and Losers were regarded as equivalently warm, with Sluts significantly less so and Agents as least warm of the four types.

In two separate analyses, we examined participants’ age and participants’ gender as demographic covariates. Tests incorporating participants’ age did not indicate any significant effects. For the purposes of testing for gender effects and as in the case of Hypothesis 1, we excluded the two participants who did not identify as either women or men. The analysis did not indicate any significant interaction effects.

Hypothesis 3

Hypothesis 3 explored thematic differences among the sexual types. We identified three themes that captured key commonalities and distinctions among participants’ descriptions of the sexual types: sociability; femininity; and vulnerability. Each of these thematic elements itself had multiple facets, reflecting participants’ complex and ambivalent perceptions of young women. We did not detect any response patterns based on participants’ age or gender.

Sociability

Participants noted social competence as a distinct strength of Agents and social awkwardness as a distinct weakness of Losers. Two-thirds of participants remarked on Agents’ active social lives and popularity: how they were “fun,” “extraverted,” the “life of the party,” and most commonly, “outgoing” (used by 34% of participants to describe the Agents they imagined). In comparison, sociability figured into only 30% of the participants’ impressions of Sluts, 11% of their impressions of Virgins, and 3% of Losers. Some participants (18%) who characterized Agents as extraverted and charismatic paired these with less endearing qualities. These participants felt that Agents could come off as “annoying,” “attention-seeking,” and “self-centered.” As one participant put it, “[Kelli] can be great at parties, but not good at friendships or relationships.” Another expressed her hypothetical distrust of “Laura,” the “very social, outgoing, and extroverted [sic]” Agent she imagined, adding “I wouldn’t want her around my significant other.” This participant included a link to a webpage entitled “Celebrities Who Celebrate Being Promiscuous” when prompted for representative images.

At the other end of the sociability spectrum, a large majority (80%) of participants characterized Losers as socially awkward or withdrawn. Much smaller minorities of participants described Virgins (22%), Sluts (13%), or Agents (2%) in these terms. Losers were most commonly described as “shy,” “timid,” “quiet,” and “awkward.” In contrast to the “party animal” and “social butterfly” Agent, a Loser might be portrayed as a “bookworm” or “wallflower.” One participant’s description of a young woman captures not only this contrast in sociability, but also the ramifications thereof, specifically one’s vulnerability (which we explore in a later section):

Donna is very shy and timid. She is socially awkward and socially anxious. She prefers quiet nights at home in her bedroom reading a book rather than a party or a club full of people. People tend to take advantage of her because she likes to avoid confrontations and has a hard time saying “no.” Donna is mousy and is usually left out of social events by her peers and coworkers. (emphasis added)

Femininity

Another thematic distinction among the various sexual types pertained to femininity. Reflecting the characteristics attributed to them using the semantic differential measure, Virgins were associated with many more feminine virtues than Agents were. We noted that 21% of participants invoked the affiliative aspect of traditional femininity (i.e., caring for others) when describing Virgins, whereas only 5% did so when describing Agents. In addition to general references to being “nice” and “kind,” 19 (10%) participants explicitly referred to Virgins’ family orientation, inclination to help others, and community involvement. For example, one participant described “Lyndsay” as “quiet, intelligent, confident, ambitious and caring. She is very family oriented and is very busy with school, work and volunteering” and selected as a representative image a young White woman looking upward and with a daisy in her hair. Only two participants mentioned Agents’ family or community ties. Tapping into a vein of feminine guilelessness, 12 (6%) participants described Virgins as “sweet” or “cute.” In comparison, only one participant referred to an Agent as “sweet,” but also suggested this might be overlooked because, “Michelle could be slightly intimidating to other people due to her high level of self-awareness.”

Some participants (15%) also referred to the kindness and caring of Losers. However, these traits’ concurrence with the type’s predominant introversion left a different impression than Virgins’ easy affiliation with others. This was illustrated by one participant’s imagining of a Loser: “Kayla is very shy and socially awkward. She wants relationships with others, but her personality often times turns people away. […] [S]he is a very caring and loving person who is often times misunderstood” (emphasis added). Only 13 (7%) participants described the Slut type in positive, traditionally feminine terms (e.g., being nice or kind). Furthermore, the majority of them (8 of 13; 62%) interpreted these as liabilities rather than strengths. This was the case of “Erica,” whom a participant characterized as “friendly and kind,” a “good hearted person,” and “having close friends,” but also “unsure of herself and prone to being unwillingly manipulated. She enjoys the company of others and her sexual partners, but sometimes she lets herself get taken advantage of by the wrong people.” Indeed, 50% of participants associated Sluts with seeming pitfalls of traditional femininity, including being “submissive,” “needy,” a “pleaser,” or a “follower.” One participant offered the following description:

[Amanda] is rather outgoing, but not intelligent. The lack of intelligence leads her to be easily manipulated and hurts her sexual autonomy. She is very nice, but kind of spacey. Has kind of low self-esteem. She finds it easy to meet men, and has a hard time saying “no” to them if they are attractive. She even has a hard time saying “no” if they aren't that attractive. She isn't very responsible, and is overly kind. This leads her to have sex with tons of people. Not intelligent, but wants to please everyone.

Vulnerability

In Amanda’s case, the confluence of gullibility, insecurity, irresponsibility, sociability, lack of intelligence, and eagerness to please creates an impression of her as sexually vulnerable. Half of participants (51%) linked such personal weaknesses to Sluts’ consequent relational or sexual vulnerability. This was typically framed in terms of being “manipulated,” “easily led,” or “taken advantage of,” as in the cited examples of Erica and Amanda or of “Alice,” who “easily gets pressured into having sex because she thinks that men will like her more that way.” The majority of these participants (70%) saw these young women as especially prone to unwanted sexual experiences because they prioritized pleasing a partner over their own interests: “[Amy] does what’s expected and what men want, not necessarily what she wants. I worry about her.”; “[Heather] tends to have sex even when/with people she might not want to, out of a desire to please.” A small number of participants (7%) speculated that these young women struggled with “trust issues,” substance abuse, or past trauma (e.g., “Tonya seems to look for love in all the wrong places. She is almost desperate. She had a bad childhood and seems to attract men that take advantage of her”; “[Sarah] has had a lot of tragedy in her life. She lives in fear and doesn’t know herself or how to set boundaries with others”). We found it notable that so many participants viewed the Slut through a lens of vulnerability and only 32% depicted them in terms traditionally tied to slut stigma (i.e., being impulsive, irresponsible, immoral, or hedonistic).

Only 6% of participants framed Losers as vulnerable, but they offered some vivid depictions thereof. They worried that ignorance, neediness, and passivity (“June” was described as a “doormat”) would lead these young women into detrimental relationships: “[Brenda’s] partner may end up emotionally hurting her”; “[Karen] will likely get swept into an unhappy marriage, one in which a man has too much control over her”; and “[Candice] is easily mislead and manipulated and may end up being trapped in an abusive relationship.” Fourteen (7%) participants also attributed Losers’ vulnerability to being sheltered and stunted: “[Daniela] never dated before because her parents wouldn’t allow it, and she dare not disobey them. […] She doesn’t feel capable of consenting since her parents control so much of her life”; “Ashley,” who is “very unsure of herself and scared, never given a proper sexual education and is full of misinformation and fallacies.”

In contrast to the supposed vulnerability of those lacking control, especially Sluts, majorities of participants attested to the seeming invincibility of Agents and Virgins. They frequently articulated this in terms of a woman’s self-awareness and self-direction. Over half (51%) of participants described Agents as knowing what they wanted and/or as unmoved by broader norms or others’ influence. This is illustrated in the description of “Chrissy”: “Fun, outgoing, easy to get along. Knows what she wants and isn’t afraid to ask for it. Doesn’t take crap from anyone.” These sentiments were echoed in 62% of the descriptions of Virgins, including “Megan”: “In control, doesn’t worry about other’s [sic] opinions, happy. Knows what she wants and will wait for it. Has a good time and is happy with herself.” The exact phrase, “knows what she wants,” was often repeated in participants’ descriptions of both Agents and Virgins (31% and 16%, respectively), albeit with substantively different endings, as in the previous examples of Chrissy (Agent), who “knows what she wants and isn’t afraid to ask for it,” and Megan (Virgin), who “knows what she wants and will wait for it” (emphasis added). This self-assured knowledge translated into the ability to ward off sexual vulnerability, as captured by “Shelly”:

She is sweet but in control. She knows what she wants and is a strong person who cannot be forced into things. She is sure of what she wants. She is able to say yes and no. She knows the boundaries she wants in a relationship and doesn't allow them to be crossed.

Only three participants suggested that Agents might be vulnerable: one referred to sexually transmitted infections; a second implied “Shawn’s” vulnerability because she is “promiscuous and takes a lot of risks”; and a third participant warned that “Cindy” “uses men for money and thinks too highly of herself. She’s the type that could be in risk of getting seriously hurt if she doesn’t change her ways.” Only one participant’s description of a Virgin, “Fayth,” suggested a degree of relational vulnerability, but not necessarily in terms of sex:

She wants to wait to have sex until marriage. She is very passionate about her choices and has a very committed boyfriend. She experiments with other acts of sex… She’s very committed to her family and traditional ways of life. She is probably a Republican. She probably bends to the wishes of her boyfriend. She is wishy washy. (emphasis added)

Discussion

We prompted participants to imagine young heterosexual women with differing sexual activity and sexual agency to understand how these factors shape perceptions and evaluations of young women. Based on Bay-Cheng’s (2015a) conceptualization of the intersection of the Virgin-Slut Continuum and the Agency Line, we expected that participants would imagine substantively distinct types about whom they would also feel differently. Confirming our first and second hypotheses, participants’ impressions of the four sexual types often aligned with the SCM (Cuddy et al. 2008; Fiske 2013; Fiske et al. 2002). This was reflected in both the open-ended descriptions and quantitative ratings of the types’ personalities. Most participants cast Virgins in a wholly favorable light, beloved as both competent and warm. The pairing of competence and warmth also resonated with our exploratory thematic analysis, through which we found Virgins characterized as effective in defending against sexual coercion and manipulation and also embodying the most positive aspects of femininity. In accordance with Bay-Cheng’s original speculations, quantitative ratings of the Agents indicated that they were perceived as the most potent and highly competent (second to Virgins), but they were also regarded with the least warmth of all the types. This was also evident in content analysis, which found that Agents were the most likely of all the types to be regarded with cool respect: acknowledged as sociable and confident, qualities that also emerged from our thematic analysis, but also as self-serving.

Akin to Agents, participants’ impressions of Losers were ambivalent. They were described in endearing terms and were rated most highly on attributes indicating interpersonal warmth. However, these favorable characterizations were mitigated by open-ended descriptions of them as ineffectual, especially in their peer and (potentially) sexual relationships, and by quantitative ratings of them as impotent and significantly less competent than Virgins and Agents. Participants’ views of Sluts were often unequivocally dim: They comprised the largest proportion of young women regarded with disdain (i.e., as neither competent nor likable); they were rated as least the competent of all the types, as impotent as Losers, and as significantly less warm than Virgins and Sluts; and thematic analyses indicated they were viewed as acutely vulnerable to negative sexual experiences.

Each analytic approach to the data (content, qualitative, and thematic analyses) confirmed our general hypotheses, yet we also observed unanticipated and complicated findings. For instance, although Agents were rated as least warm of all the sexual types and accounted for the largest proportion of those regarded with cool or qualified respect, far more participants depicted Agents as beloved. We take this as a sign that young women’s sexual activity and expression are often and perhaps increasingly fully embraced, as long as they are accompanied by apparent sexual agency. This possibility aligns with growing support for women’s agency in other domains (e.g., careers; Diekman and Goodfriend 2006) and warrants deeper, broader, more systematic, and replicated analyses.

The prospect that support of Agents is attributable to a receding sexual double standard is tempered by some of our other findings, namely the far stronger affirmation of agentically abstinent Virgins. In their open-ended responses and personality attributions, participants clearly favored agentically abstinent Virgins above all others. This resembles related research using role congruity theory, including Diekman and Goodfriend’s (2006) finding that women’s agency garners the most support when it is accompanied by aspects of traditional femininity (e.g., caretaking). In our study, young women seen as choosing abstinence as a matter of independence, responsibility, and ambition strike an uncanny balance between hegemonic femininity and neoliberal ideology. They somehow meet traditional expectations that they be affiliative and pleasing (i.e., Brown and Gilligan’s 1992, p. 53, “tyranny of nice and kind”) while also answering the charge of self-interested ambition. By meeting these seemingly contradictory dictates, the figure of the Virgin serves multiple purposes. A young woman who chooses abstinence as a means of self-advancement remains within the bounds of two normative comfort zones: her sexual behavior adheres to conventional femininity while her self-interested rationale implies unencumbered choice. She appears neither compelled nor constrained, relieving us from worrying either about sexism as an enduring force or about our complicity with it. Instead, she allows us to see her and ourselves as free and fair-minded individuals living in a just system.

Whether sexually active or abstinent, both Agents and Virgins were described as knowing sexual subjects (including the recurring literal phrase of “she knows what she wants”) who were well-positioned to negotiate sexual relationships. To the contrary, Losers were painted as unknowing and ill-equipped, whether in terms of inherent traits, social skills, or external supports (e.g., parents, sexuality education). The combination of their ineptitude and harmlessness places them squarely in the SCM’s category of the pitied, in need of help and protection. A meaningful deviation from our hypotheses is that so many Sluts were also regarded with sympathy. Despite being associated most strongly with socially undesirable characteristics and forming the largest proportion of those in the disdained category (i.e., neither competent nor warm), participants’ open-ended descriptions of Sluts were not predominantly or unilaterally contemptuous. Instead, participants most commonly expressed worry and concern on behalf of those who were sexually active but not sexually autonomous. This manifested in the open-ended data as well as personality quality ratings, in which Sluts were rated as warmer than Agents.

Concern about Sluts seemed to stem from their defenselessness against unwanted, unsafe, and unwise sexual interactions (similar to Losers and in sharp contrast to Agents and Virgins). Although “slut” as a stigma traditionally signifies being oversexed and/or undisciplined, the current study’s participants described young women rendered vulnerable not by their own appetite or lack of will but by their inability to ward off others’ (i.e., men’s) appetites and wills. This echoes the stories of sexual bullying told by Miller’s (2016, p. 732) participants who recalled that high school classmates who were stigmatized as sluts had been seen as “complacent to guys” and who “let boys use them.” Paralleling Miller’s findings, our participants’ descriptions of women who are “easily led” or “let guys take advantage” implied that some degree of coercion by men is to be expected and accepted as a matter of fact. This formulation conforms not only to an “antagonistic” model of heterosexuality in which men and women are pitted against each other (Elliott 2014), but also the patriarchal discourse of an irrepressible and entitled male sex drive, one that naturalizes sexually exploitative, if not predatory, behavior by men (Gavey 2005; Sakaluk et al. 2014; Tolman et al. 2016). That this cornerstone of “toxic masculinity” went uncritiqued (implicitly or explicitly) is especially noteworthy given how some participants were critical of Sluts’ embodiment of key shortcomings of femininity (in contrast to Virgins’ expression of the best parts of femininity), such as passivity, neediness, and gullibility.

Furthermore, just as female sexuality is often defined in solely reactive terms (i.e., women’s sexuality is a matter of refusing or complying with interactions initiated by men), participants seem to conceive of women’s sexual autonomy as revolving around men’s behavior insofar as it entails not only directing one’s own behavior, but also anticipating and deflecting others’. This reactive or defensive construction of autonomy was also reflected in participants’ praise of Agents and Virgins for setting and maintaining clear limits, for being women who “cannot be forced” (see the example of Shelly). What differentiates Sluts and provokes participants’ concern for them is not simply their lack of self-control, but their lack of control over others (i.e., men). Those without the ability or will to counter men’s sexual drives are left vulnerable to the whims of male partners.

Other aspects of the seeming sympathy afforded to Sluts should be interpreted cautiously and critically. As exemplified by one of Miller’s (2016, p. 735) participants recalling a high school classmate who had been stigmatized as a slut, pity and blame are not mutually exclusive: “[on] some levels I feel really bad for her. But at the same time, on some level, I want to believe that she deserved it.” Some of the charitable depictions of Sluts in our study might have stemmed more from social desirability bias than compassion. As “slut shaming” and “victim blaming” are increasingly criticized in popular discourse, including by media outlets such as the Huffington Post (e.g., Tanenbaum 2015) and major organizations such as the NFL (National Football League 2017), people may feel compelled to distance themselves from these practices, whether in their actual thinking or only in their outward expression. The tenets of Fiske’s (2013) SCM also put sympathetic responses to Sluts in important context: although not as overtly harsh or hostile as disdain (or disgust, as in the SCM), pity is nevertheless dehumanizing through its condescension. Occupants of that SCM quadrant are regarded warmly insofar as they are harmless, but they are not regarded as competent and fully-fledged, either. Part of the critical value of the SCM is that it reminds us not to mistake pity as a lesser evil when it comes to dehumanization; instead, it is simply a different one. Furthermore, pity quickly converts into disdain and contempt if someone issues a challenge to dominant norms and hierarchies.

Limitations and Future Directions

Ours is the first known attempt to test Bay-Cheng's (2015a) proposal that neoliberal agency has emerged as an evaluative dimension in appraisals of young women’s sexuality. As such, it is a preliminary study with certain limitations to be corrected and built on in future studies. For instance, there were some fundamental flaws in the study’s design and measures. We aimed to be parsimonious in describing each type, but our phrasing may have primed participants to see the types in favorable or unfavorable lights. We opted to use “autonomy” to denote agency because we believed the former was more likely to be similarly comprehended and consistently interpreted by the broadest range of participants. However, participants may have had variable understandings of the word. We also have no information about participants’ own attitudes about “normal” sexual behavior for young women and therefore could not control for resulting variations in their impressions of the types.

Our randomization of the order in which the types were presented to participants and the order of the semantic differential items helped reduce possible order effects, but did not eliminate these completely. We were unable to track the sequences of prompts to participants (i.e., the order in which the types and semantic differential items were presented), meaning we could not account for order effects, either. We did not use an established set of semantic differential items, nor did we systematically select them from a larger pool tested on another sample. This may explain why only two semantic differential items loaded onto the Warmth factor. Our lack of an established or systematically derived pool of attributes also precludes our ability to probe these and the factor analysis results more extensively. We plan to correct this in future work by using the current study’s results to guide the systematic refinement of the semantic differential item pool (see recommendations of Verhagen et al. 2015). For instance, the prominence of sociability in participants’ open-ended descriptions and the recurrence of specific phrases (e.g., “outgoing,” “shy,” “awkward”) indicates that these constructs warrant inclusion in future work.

There are also sample-related limitations. Sexuality-related studies often draw participants who are more comfortable thinking about and discussing sexuality and who hold more liberal attitudes toward it than the general population (Strassberg and Lowe 1995). Reflecting this bias, it is possible that our sample was more favorably disposed toward the sexually active types (i.e., Agents and Sluts). Turkers are also a specialized group who do not represent a larger population. Off-setting its curtailed generalizability is growing evidence that MTurk is a viable and valuable means of data collection (Goodman et al. 2013; Paolacci and Chandler 2014) and that Turkers are especially attentive research participants (Hauser and Schwarz 2016). Indeed, many participants in the current study offered detailed responses to open-ended questions, suggesting their thoughtful engagement with the study and consequent quality of the dataset. Aside from its basis in MTurk, the size and composition of our sample certainly affected our findings, often in ways that we are unable to discern more fully. For instance, the small size and wide spread of participants’ ages in the dataset prevented us from a more careful analysis of possible age and cohort effects. In addition, our findings are filtered through the predominantly White, heterosexual lens of our participants.

Another of Bay-Cheng’s (2015a) claims was that evaluations of young women’s sexuality would echo racist and classist biases. Although we did not detect this in the textual data, the images provided by participants for each sexual type hold tremendous promise for detecting implicit perceptions and attitudes. We have initiated a systematic content analysis of the images, scanning for trends in poses (e.g., reclining, standing), settings (e.g., outdoors, at a party), props (e.g., books, alcohol), and appearance (e.g., body size, apparent race). Among the study’s hypotheses is our expectation, based on the documented codependence of racial and sexual stigmatization of Women of Color (Bettie 2014; Fasula et al. 2014; García 2009; Stephens and Phillips 2003), that images of Sluts will include more Women of Color, particularly those who appear Black or Latina.

Practice Implications

Those invested in gender and sexual equality should be encouraged by some aspects of our findings, particularly the generally favorable portrayals of Agents. Increasing young women’s sexual assertiveness, along with others’ support for sexually assertive young women, has been a key objective of feminist researchers, practitioners, and advocates (Lamb 2010a). However, these same stakeholders should also be cautious about how sexual agency is defined for and by young women. In our findings, even descriptions of strident sexual agency and independence often revolved around preempting and repelling male sexual coercion (e.g., being too smart, too savvy, too strong to be taken advantage of). Policies, programs, and public awareness campaigns should beware of construing sexual agency in terms that continue to saddle young women with sexual gatekeeping.

Critical discourse and action against “rape culture” represent the effort to shift interventions away from changing young women’s individual skills or behavior (e.g., increasing sexual assertiveness) and toward altering the systemic conditions of their sexual lives so that coercion and manipulation are not treated as mainstays of heterosexual interactions. This includes counteracting traditional gender socialization, norms, and practices through formal, institutional efforts (e.g., sexuality education; Berglas et al. 2014) as well as spontaneous, socially networked challenges (e.g., digital consciousness-raising campaigns such as #metoo and #yesallwomen; e.g., Keller et al. 2018). These efforts could be bolstered even further by offering new models of sexual socialization, such as Lamb’s (2010b) incorporation of ethics into sexuality education, and alternative conceptualizations of agency, such as Pham’s (2013) distinction between responsibility and response-ability. Practices aimed at system change must disrupt not only the ways in which young women’s sexual agency is circumscribed or young women are typecast, but also the roles and scripts available to young men. Indeed, although the costs of hegemonic gendered sexual norms may vary between men and women (e.g., Bay-Cheng et al. 2018), the former are no less constrained by gendered sexual scripts and may be motivated to reform the foundations of intimate relationships (Casey et al. 2016; Smiler 2008).

Conclusion

It is exciting and appealing to see signs that things are getting better for young women; not only that they are able to exercise greater freedom over their sexual lives, but also that others endorse their right to do so. Nevertheless, we must consider any apparent progress thoroughly. For instance, we are encouraged by the predominantly favorable impressions of Agents, although we also note that this was tinged with ambivalence and that Virgins remain the most wholeheartedly embraced. An implicit thread through participants’ characterizations of the types, especially Virgins, Agents, and Sluts, is how much their inferred agency hinged on their self-protection and defense against men. We see this as a recapitulation of the long-standing paradox that so much of a young woman’s perceived character and social worth is derived from her sexuality, yet so much of her sexuality is dependent on her ability to control men’s. Findings such as ours indicate that gendered sexual norms that impinge on and stigmatize young women’s sexualities are being shifted rather than lifted completely. This reinforces Bay-Cheng’s (2015a) claim that young women are still judged and situated within a normative space based on their (perceived) sexualities, with some viewed more favorably than others. Participants saw the types differently (i.e., as having distinct personality qualities) and also felt differently toward them (i.e., in terms of competence and warmth), indicating that sexuality continues to drive our judgment and in some cases, degradation, of young women’s worth and personhood.

References

Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L. T., Armstrong, E. M., & Seeley, J. L. (2014). “Good girls”: Gender, social class, and slut discourse on campus. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77, 100–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272514521220.

Attwood, F. (2007). Sluts and riot Grrrls: Female identity and sexual agency. Journal of Gender Studies, 16, 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230701562921.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2015a). The agency line: A neoliberal metric for appraising young women’s sexuality. Sex Roles, 73, 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0452-6.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2015b). Living in metaphors, trapped in a matrix: The ramifications of neoliberal ideology for young women's sexuality. Sex Roles, 73, 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0541-6.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Livingston, J. A., & Fava, N. M. (2011). Adolescent girls’ assessment and management of sexual risks: Insights from focus group research. Youth Society, 43, 1167–1193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X10384475.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Maguin, E., & Bruns, A. E. (2018). Who wears the pants: The implications of gender and power for youth heterosexual relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 55, 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1276881.

Beckmeyer, J. J., Ganong, L. H., Coleman, M., & Markham, M. S. (2017). Experiences with Coparenting scale: A semantic differential measure of postdivorce coparenting satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 38, 1471–1490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X16634764.

Berglas, N. F., Angulo-Olaiz, F., Jerman, P., Desai, M., & Constantine, N. A. (2014). Engaging youth perspectives on sexual rights and gender equality in intimate relationships as a foundation for rights-based sexuality education. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 11, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-014-0148-7.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com's Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20, 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr057.

Bettie, J. (2014). Women without class: Girls, race, and identity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brown, L. M., & Gilligan, C. (1992). Meeting at the crossroads: Women's psychology and girls' development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Casey, E. A., Masters, N. T., Beadnell, B., Wells, E. A., Morrison, D. M., & Hoppe, M. J. (2016). A latent class analysis of heterosexual young men’s masculinities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1039–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0616-z.

Charles, C. E. (2010). Complicating hetero-femininities: Young women, sexualities and “girl power” at school. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23, 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390903447135.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 61–149.

Diekman, A. B., & Goodfriend, W. (2006). Rolling with the changes: A role congruity perspective on gender norms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00312.x.

Elliott, S. (2014). “Who’s to blame?” Constructing the responsible sexual agent in neoliberal sex education. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 11, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-014-0158-5.

Estepa, J. (2017, May 23). Donald Trump calls Manchester bomber (and many, many other people) ‘losers’. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2017/05/23/other-people-besides-manchester-bomber-trump-has-called-losers/102047624/.

Fahs, B., & McClelland, S. I. (2016). When sex and power collide: An argument for critical sexuality studies. Journal of Sex Research, 53, 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1152454.

Farvid, P., Braun, V., & Rowney, C. (2017). ‘No girl wants to be called a slut!’: Women, heterosexual casual sex and the sexual double standard. Journal of Gender Studies, (5), 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1150818.

Fasula, A. M., Carry, M., & Miller, K. S. (2014). A multidimensional framework for the meanings of the sexual double standard and its application for the sexual health of young Black women in the U.S. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.716874.

Fiske, S. T. (2013). Varieties of (de)humanization: Divided by competition and status. In S. J. Gervais (Ed.), Objectification and (de)humanization (pp. 53–71). New York: Springer.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.878.

Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (2005). Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality (2nd ed.). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers (Original work published 1973).

García, L. (2009). Now why do you want to know about that?: Heteronormativity, sexism, and racism in the sexual (mis)education of Latina youth. Gender and Society, 23, 520–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243209339498.

Gavey, N. (2005). Just sex? The cultural scaffolding of rape. New York: Routledge.

Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., & Cheema, A. (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1753.

Griffin, C., Szmigin, I., Bengry-Howell, A., Hackley, C., & Mistral, W. (2013). Inhabiting the contradictions: Hypersexual femininity and the culture of intoxication among young women in the UK. Feminism & Psychology, 23, 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353512468860.

Haslam, N., & Loughnan, S. (2014). Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 399–423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045.

Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods, 48, 400–407. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z.

Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1, 77–89.

Jonason, P. K., & Marks, M. J. (2009). Common vs. uncommon sexual acts: Evidence for the sexual double standard. Sex Roles, 60, 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9542-z.

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116.

Keller, J., Mendes, K., & Ringrose, J. (2018). Speaking ‘unspeakable things’: Documenting digital feminist responses to rape culture. Journal of Gender Studies, 27, 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1211511.

Kervyn, N., Fiske, S. T., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2013). Integrating the stereotype content model (warmth and competence) and the Osgood semantic differential (evaluation, potency, and activity). European Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1978.

Lamb, S. (2010a). Feminist ideals for a healthy female adolescent sexuality: A critique. Sex Roles, 62, 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9698-1.

Lamb, S. (2010b). Towards a sexual ethics curriculum: Bringing philosophy and society to bear on individual development. Harvard Educational Review, 80, 81–105. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.80.1.c104834k00552457.

Lamb, S., & Peterson, Z. D. (2012). Adolescent girls’ sexual empowerment: Two feminists explore the concept. Sex Roles, 66, 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9995-3.

Milhausen, R. R., & Herold, E. S. (2001). Reconceptualizing the sexual double standard. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 13, 63–83.

Miller, S. A. (2016). How you bully a girl: Sexual drama and the negotiation of gendered sexuality in high school. Gender and Society, 30, 721–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243216664723.

National Football League. (2017, August 16). Statement from Joe Lockhart, NFL Executive Vice President of Communications. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/NFLprguy/status/897863415313698816.

Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Paolacci, G., & Chandler, J. (2014). Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414531598.

Payne, E. (2010). Sluts: Heteronormative policing in the stories of lesbian youth. Educational Studies, 46, 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131941003614911.

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504.

Pham, Q. N. (2013). Enduring bonds: Politics and life outside freedom as autonomy. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 38, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375412465676.

Pierce, W. D., Sydie, R. A., Stratkotter, R., & Krull, C. (2003). Social concepts and judgments: A semantic differential analysis of the concepts feminist, man, and woman. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27, 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00114.

Reid, P. T., & Bing, V. M. (2000). Sexual roles of girls and women: An ethnocultural lifespan perspective. In C. B. Travis & J. W. White (Eds.), Sexuality, society, and feminism (pp. 141–166). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ringrose, J., & Walkerdine, V. (2007). What does it mean to be a girl in the twenty-first century? Exploring some contemporary dilemmas of femininity and girlhood in the West. In C. A. Mitchell & J. Reid-Walsh (Eds.), Girl culture: An encyclopedia (Vol. 1, pp. 6–16). Westport: Greenwood Press.

Sakaluk, J. K., & Milhausen, R. R. (2012). Factors influencing university students' explicit and implicit sexual double standards. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 464–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.569976.

Sakaluk, J. K., Todd, L. M., Milhausen, R., Lachowsky, N. J., & Undergraduate Research Group in Sexuality URGiS. (2014). Dominant heterosexual sexual scripts in emerging adulthood: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.745473.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1986). Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 15, 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01542219.

Smiler, A. P. (2008). “I wanted to get to know her better”: Adolescent boys’ dating motives, masculinity ideology, and sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.006.

Stephens, D. P., & Phillips, L. D. (2003). Freaks, gold diggers, divas, and dykes: The sociohistorical development of adolescent African American women’s sexual scripts. Sexuality and Culture, 7, 3–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03159848.

Stewart, A. J., & Healy, J. M. (1989). Linking individual development and social changes. American Psychologist, 44, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.1.30.

Strassberg, D. S., & Lowe, K. (1995). Volunteer bias in sexuality research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541853.

Tanenbaum, L. (2015). The truth about slut-shaming [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/leora-tanenbaum/the-truth-about-slut-shaming_b_7054162.html.

Tolman, D. L., Davis, B. R., & Bowman, C. P. (2016). “That’s just how it is”: A gendered analysis of masculinity and femininity ideologies in adolescent girls’ and boys’ heterosexual relationships. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31, 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415587325.

Valenti, J. (2010). The purity myth: How America’s obsession with virginity is hurting young women. Berkeley: Seal Press.

Verhagen, T., van den Hooff, B., & Meents, S. (2015). Toward a better use of the semantic differential in IS research: An integrative framework of suggested action. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 16, 108–143.

Wilke, J., & Saad, L. (2013, June 3). Older Americans’ moral attitudes changing: Moral acceptance of teenage sex among the biggest generational divides. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/162881/older-americans-moral-attitudes-changing.aspx.

Wilkins, A. C., & Miller, S. A. (2017). Secure girls: Class, sexuality, and self-esteem. Sexualities. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460716658422.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julie M. Maier for her assistance with analyses. The first author thanks Ella Ben Hagai for the opportunity to present a version of this work in September 2017 as part of Bennington College’s Society, Culture, & Thought colloquium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was approved by the University at Buffalo’s Institutional Review Board. This is original work that has not been previously published and is not under consideration at another journal. This research was not supported through external funds. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 57 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bay-Cheng, L.Y., Bruns, A.E. & Maguin, E. Agents, Virgins, Sluts, and Losers: The Sexual Typecasting of Young Heterosexual Women. Sex Roles 79, 699–714 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0907-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0907-7