Abstract

In many Western public primary school systems, the gender composition of the principals is more heterogenic than that of the teachers, but research on the effect of gender on social psychological processes related to school leadership is scarce. The present work aims to address this lacuna by exploring the effects of principal-teacher gender similarity in the Israeli public primary school system, where most teachers are women, on teachers’ trust in their principals and on organizational commitment. Data from 594 female public primary teachers working with male and female principals were analyzed. The results show that when the principal and teacher are of the same gender, both affective and cognitive trust in the principal are higher. Moderation analysis indicated that female teachers’ affective trust in male principals increases with relational duration. A second moderation effect that was found indicated that gender similarity and cognitive trust in principal have a negative interactive effect on teachers’ continued commitment to school, countering the positive effect of gender similarity on commitment. The results and their implications are discussed, and future research is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The influence of principals on teachers’ work-related attitudes, such as trust in the principal and organizational commitment, has been widely explored and documented (Bogler and Somech 2004; Hoy and Tschannen-Moran 2007; Hulpia and Devos 2010; Wahlstrom and Louis 2008). Educational administration researchers have contended that principals’ behaviors exert a powerful influence on teachers’ attitudes at work (Hallinger 2003; Leithwood and Jantzi 2005). Such behavioristic focus, however, often ignores fundamental characteristics, such as gender, that shape principal-teacher interactions.

The educational literature contains only a handful of works dealing with the role and the effects of gender on principal-teacher relations. But studies have shown that gender is a key variable that requires attention when theorizing and exploring leadership (Ayman and Korabik 2010; Bolman and Deal 1992; Eagly et al. 1992; Ely et al. 2011; Vinkenburg et al. 2011). Studying leadership without the inclusion of gender can limit the results in two ways: (a) at the practical level, because gender and the dynamics it generates create issues that need to be addressed, and (b) at the basic scientific level, because failure to include gender limits the generalizability of theories and findings (Ayman and Korabik 2010).

These lacunae are particularly prominent when bearing in mind the fact that in some educational settings gender is a highly visible aspect, to the point where it becomes a characteristic of the system itself. Teachers in public primary schools in many Western countries are predominantly women. For example, 89% of the teachers in public primary schools in the United States (NCES 2013a) and 88% in the United Kingdom (Paton 2013) are women. By contrast, only 64% of public primary school principals in the United States (NCES 2013b), and 65% of head teachers in the primary state system in the United Kingdom (O'Conor 2015) are women. This creates an organizational array in which principal-teacher gender similarity and dissimilarity are highly noticeable.

The present study seeks to understand how principal-teacher gender similarity in an overwhelmingly feminine public primary school system affects school leadership-related outcomes, specifically teachers’ trust and commitment. The study is situated in the Israeli public primary system. A majority of the primary schools in Israel are publicly funded, operated, and managed. The present research focuses on the Jewish sub-system, in which for decades the percentage of female teachers has been around 85% (The World Bank 2017). At the same time, about two thirds (67%) of principals in the Israeli public primary system are women (IISL 2012).

Principal-Teacher Gender Similarity and Teachers’ Trust

Relational demography theory, which originated in social psychology research, suggests that demographic variables such as gender, race, education level, and socioeconomic status are central in promoting important work outcomes (Sacco et al. 2003). According to this theory, homophily is a key human inclination, so that similar individuals in the workplac, sense some type of interpersonal attraction fueled by the desire to define one’s self-concept as part of a social group (Goldberg et al. 2010). Relational demography research shows that demographic similarity between individuals at work is associated with individuals perceiving work as a supportive environment (Avery et al. 2008). Supervisor-employee gender similarity has been shown to influence employees’ work attitudes. Gender similarity between supervisors and employees is said to directly enhance a sense of interpersonal trust.

The classic definition of interpersonal trust conceptualizes it as “one’s willingness to be vulnerable to another based on the confidence that the other is benevolent, honest, open, reliable and competent” (Tschannen-Moran 2004, p. 17). Accumulated empirical evidence indicates that the success of schools is contingent upon trust among stakeholders (Bryk and Schneider 2002; Forsyth et al. 2011), in particular upon teachers’ trust in the principal (Handford and Leithwood 2013; Moye et al. 2005; Tarter and Hoy 1988). Interpersonal trust is said to have two bases: cognitive and affective (McAllister 1995). Cognitive trust in the leader reflects the employee’s inclination to view the leader as competent and reliable; affective trust in the leader reflects the employee’s sense of connection and care in exchanges with the leader (Yang et al. 2009).

Several studies in the educational literature have acknowledged the possibility of an effect of principal-teacher gender similarity on teachers’ trust in the principal. Addressing principal-teacher relations, Price (2012, p. 51) contended that “persons are more likely to build trusting relationships with others of similar gender.” Reflecting on the limitations of his study, which was based on a sample of 166 male primary school principals and 449 teachers (55.6% female), Zeinabadi (2014, p. 401) recently speculated that principal-teacher gender match influences trust in the principal: “perhaps male teachers rate their trust in their male principals more favorably than when they rate their trust in their female principals.” Empirical evidence on the effects of leader-follower gender similarity on trust in the leader is limited, but it is possible to infer it from parallel findings. For example, Foley et al. (2006) found that supervisors provided more family support to subordinates of the same gender than to those of the other gender. Additional relevant findings are reported in research on the quality of leader-member exchanges (LMX), which are often viewed as equivalent to interpersonal affective trust (Bauer and Green 1996). Liden et al. (1993) explored American universities and found a significant positive association between leader-follower gender similarity and LMX. It is likely that principal-teacher gender similarity promotes teachers’ trust in their principal, particularly affective trust. Therefore, I hypothesize that teachers’ trust in their principal will be higher in the context of principal-teacher similarity than dissimilarity (Hypothesis 1).

Duration of Relationship as a Moderator of Gender Similarity

Scholars have argued that the element of time can be a key variable in moderating the effects of demographic similarity in relationships because relationships develop over time. For example, Duck’s (1977) filter theory suggests that as a relationship develops and more detailed and multifaceted information becomes available, an individual’s attention shifts from superficial, easily accessible characteristics of the partner to deeper ones. Harrison et al. (1998) study of hospital units and employees of deli-bakeries found that gender diversity correlates negatively with group cohesion in groups with shorter, but not in groups with longer, job tenure. The researchers concluded that time is a “conduit” of information that enables “richness of interactions” (Harrison et al. 1998, p. 104). Turban et al. (2002) examined how gender similarity affects doctoral students’ perceptions of mentoring received in faculty advisor-student dyads, and they found that the duration of the relationship moderated the effect of gender similarity. Therefore, I hypothesize that the relationship between principal-teacher gender similarity and trust in the principal will be moderated by the duration of principal-teacher relations such that the positive effects of principal-teacher gender similarity are stronger for shorter relations (Hypothesis 2).

Gender Similarity as a Moderator of Teachers’ Trust

Organizational commitment is defined as “a psychological link between the employee and his or her organization that makes it less likely that the employee will voluntarily leave the organization” (Allen and Meyer 1996, p. 252). Two types of organizational commitment appear repeatedly in theoretical conceptualizations (Meyer and Allen 1991, 1997): (a) continuance commitment, which manifests in awareness of possible costs of leaving the organization, and (b) affective commitment, which manifests in emotional bond and identification with the organization. According to the organizational literature, employees’ trust in a leader promotes a range of desired work attitudes and behaviors, including employees’ organizational commitment (Dirks and Ferrin 2002). The connection between teachers’ trust in the principal and their organizational commitment can be partly explained by the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960). In a high-trust relationship, teachers may receive or perceive themselves as receiving desired benefits from the principal. This situation is likely to create a sense of obligation to reciprocate (Gouldner 1960) because teachers feel more indebted to the principal and, indirectly, to the organization.

For example, Zeinabadi and Salehi (2011) suggested that principals’ and teachers’ relations are social exchanges that lead to teachers’ commitment to school. A meta-analysis indicates that trust in a leader is moderately related to followers’ organizational commitment (Dirks and Ferrin 2002). In a study of 72 secondary schools in the United States, Tarter et al. (1989) found that principals’ openness, a component frequently associated with trust, correlated significantly with teachers’ organizational commitment. In their study of Iranian public primary school teachers, Zeinabadi and Salehi (2011) found a weak correlation between generalized trust in principals and teachers’ affective commitment. Their sample was composed from 131 male principals and 652 teachers, 54% of them female.

The literature suggests that demographic similarity may serve as a contextual variable with a significant moderating effect. This idea is derived from social categorization theory, which argues that individuals classify the self and others into social groups based on noticeable characteristics and use these categories to define their social identities (Turner et al. 1987). Gender is considered a key visible demographic characteristic that is likely to induce social categorization in leadership processes (Sanchez-Hucles and Davis 2010). Based on social categorization theory, Carter et al. (2014) proposed that supervisor-subordinate demographic differences, including gender, can influence subordinates’ attitudes and actions. It is possible that the effect of demographic matching as a moderator correlates not only with demographic similarity, reaffirming one’s social identity, but also with demographic dissimilarity, threatening one’s social identity.

Research shows that demographic dissimilarity in the workplace is related to psychological threats to individuals’ gender-based identity and therefore produces anxiety (Avery et al. 2013). A situation of gender dissimilarity might cause uncertainty among employees, whether or not they enjoy approval or have doubts about their status. Threats to individuals’ self-worth cause them to be more preoccupied with their own welfare and embrace a preventive, self-regulatory attitude that limits possible psychological harm (Johnson et al. 2010). Empirical evidence from educational research provides partial support for these claims. For example, Lee et al. (1993), who explored 300 secondary schools (public, Catholic, and private) in the United States, found that working with female principals, female teachers felt empowered, whereas male teachers experienced themselves as being less powerful. Similarly, Chusmir’s (1990) review of empirical findings indicates that male teachers reported perceiving a low level of approval from their female administrators. In other words, in cases of gender dissimilarity, teachers are likely to report a weaker perception of trust in their principal, possibly because dissimilarity triggers a subconscious warning mechanism that continually signals to teachers that their social status in the organization is uncertain. Therefore, I hypothesize that-teacher gender similarity will moderate the effects of teachers’ trust in their principal on teachers’ commitment, that is, in case of principal-teacher gender dissimilarity, the effects of teachers’ trust in their principal on teachers’ commitment will be weaker (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Sample and Procedure

The data in the present research originate from a dataset on school leadership. The data were collected using random sampling of state primary schools in the Jewish sector by using a list provided by the Ministry of Education. School recruitment rate was 64%, and the research team contacted teachers on site, asking them to voluntarily participate in the survey and guaranteeing anonymity. The original dataset contained data from 655 Israeli state primary school teachers. The gender composition of teachers in the dataset was overwhelmingly female (92%, n = 594), somewhat similar to the gender composition of the state primary education system (85.29% in 2014; The World Bank 2017). For the purpose of the present study, and to ease the interpretation of the findings in the discussion section, 61 male teachers were omitted from the data.

The analyses in the present study were performed on data that included 594 female teachers. Most of the teachers (407, 68.5%) held B.A. degrees, 115 (19.4%) held M.A. degrees, and the remaining 72 (12.1%) held professional certification degrees. Their teaching experience ranged from one to 39 years (M = 17.07, SD = 9.61), and the duration of their relationship with the principals ranged from one to 30 years (M = 7.09, SD = 5.36).

The teachers reported on their principals, of whom 74% (n = 51) were female—a similar ratio of women-to-men to that of the state primary system in general (IISL 2012). The growing proportion of male principals in the Israeli primary education system is partly linked with a shortage of principals and a difficulty in attracting candidates for principalship from within the public system. For example, the Israeli ministry of education reported that only 4–5 candidates compete for each principal’s position (Valmer 2012). Proactive attempts to address the shortage of principals has led, among others, to approaching individuals outside the public education system who are seeking a second career. These individuals often lack relevant educational background, and many of them are men (Barkol 2005).

Measures

Teachers’ Trust in the Principal

Trust in the principal was measured on two-subscales proposed by McAllister (1995): affective trust (5 items) and cognitive trust (6 items). Sample items are: “If I shared my problems with the principal, I know he/she would respond constructively and caringly” (affective) and “The principal approaches his/her job with professionalism and dedication” (cognitive). Participants provided their answers on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using a maximum likelihood estimator (ML) was conducted in the AMOS structural equation modeling software to explore the structure of the data. The theorized two-factor measurement model demonstrated a good fit (CFI, NFI, GFI and TLI values above .95 and RMSEA values below .06 represent good fit; Byrne 2010; Hu and Bentler 1999): χ2(33) = 95.65, p < .001, CMIN/ DF = 2.89, CFI = .98, NFI = .98, GFI = .97, and TLI = .97, RMSEA = .05. Therefore, the present CFA results support the findings of earlier literature about the two-factor structure of the scale (McAllister 1995). The original scale was reported to be valid and reliable, with the two subscales of affective and cognitive trust described as having excellent Cronbach’s alphas (.89 and .91 respectively; McAllister 1995). In the present study, internal consistency reliabilities were similar: .88 for affective trust and .92 for cognitive trust. Item responses were averaged across each subscale so that higher scores indicated greater trust.

Teachers’ Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment was assessed using Porter et al. (1974) two subscales of affective commitment (9 items) and continuance commitment (6 items). Representative items are: “This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me” (affective) and “I feel very little loyalty to this organization” (reversed item; continuance). Teachers marked their responses on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). The Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) scale was originally validated in series of studies (Mowday et al. 1979; Mowday et al. 1982), and its two-factor structure was supported in factor analyses (Koh et al. 1995; Tetrick and Farkas 1988). The present CFA results reconfirmed the earlier reports of the two-factor structure of the scale. The two-factor model demonstrated a good fit: χ2(85) = 218.81, p < .001, CMIN/ DF = 2.57, CFI = .96, NFI = .95, GFI = .95, and TLI = .96, RMSEA = .05. The literature reports internal consistency reliabilities of .88 for the affective commitment factor and of .72 for the continuance commitment factor (Angle and Perry 1981). In the present research, Cronbach’s alpha was .88 for affective commitment and .80 for continuance commitment. Item responses were averaged across each subscale so that higher scores indicated stronger commitment.

Principal-Teacher Similarity and Relationship Duration

First, the teachers’ and their respective principals’ genders were dummy-coded for all respondents (0 = male, 1 = female). Next, principal-teacher gender similarity was calculated based on absolute differences between the principals’ and teachers’ genders. Results were transformed, so that in the final index a value of 1 indicates gender similarity between principal and teacher and a value of 0 gender dissimilarity. The duration of teacher-principal acquaintance was determined by a survey question asking teachers to state the length of their relationship with their principal in years.

Covariates

Teachers’ demographics were used as control variables: teaching experience (in years) and education (1 = professional certification degree, 2 = B.A., and 3 = M.A.). Experience is part of on-the-job socialization, therefore it encourages one’s trust in peers (Moreland and Levine 2002); by contrast, higher education stimulates one’s critical thinking (Pithers and Soden 2000). Teachers’ experience and education are likely to influence commitment to school. The literature notes that professional commitment increases with experience, which in turn is considered to promote organizational commitment (Sheldon 1971), whereas highly educated individuals tend to be less committed to the organization (Steers 1977).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables are presented in Table 1. The table provides some preliminary support for the study hypotheses. The average trust levels suggest that teachers’ trust in their principal was higher in gender-similar relationships than in gender-dissimilar ones. The correlations between the duration of principal-teacher relations and the two trust types, in particular with affective trust, were stronger under gender dissimilarity. Finally, the correlations between teachers’ cognitive trust and both types of teachers’ commitment were stronger in gender-similar relationships.

Hypothesis Testing

First, as part of the exploration of Hypothesis 1, which predicted higher teachers’ trust in similar than in dissimilar relationships, I performed a MANOVA analysis to investigate the differences in affective trust and cognitive trust in the principal by principal-teacher similarity. The multivariate analysis of variance was significant, Wilk’s Λ = .976, F(2, 591) = 7.19, p = .001, ηp2 = .024. The means of affective trust, F(1, 592) = 14.11, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .34, and of cognitive trust, F(1, 592) = 4.38, p = .037; d = .20, in the principal were higher for teachers in the case of principal-teacher similarity than in the case of principal-teacher dissimilarity (see Table 1). Thus, consistent with Hypothesis 1, the differences in trust by gender similarity were found to be significant but small in effect size.

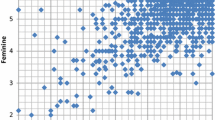

Next, I performed hierarchical regression analyses to explore the moderation effect of duration of principal-teacher relations on the link between principal-teacher gender similarity and trust in the principal (Hypothesis 2). As shown in Table 2, the interactions between duration of relationship and principal-teacher similarity did not significantly predict cognitive trust in the principal (see Table 2b), but they did significantly predict affective trust (see Table 2a). Thus, only the latter moderation effect provided support for Hypothesis 2. The positive main effect of gender similarity on teacher’s affective trust in the principal was approximately two-third of the size of the negative interaction effect, therefore the correlation between the effect of gender similarity on affective trust and the duration of relationship is largely negative. The significant interaction was plotted following Aiken and West’s (1991) recommendation for reducing biases by calculating high and low levels of a continuous variable as one SD above and below the variable mean. As can be seen from the simple slope effects in Fig. 1, the interaction was such that the association between duration of the relationship and affective trust in the principal was positive under principal-teacher dissimilarity (dashed line; B = .063, t = 3.97, p < .001), and positive but non-significant under principal-teacher similarity (solid line; B = .011, t = 1.21, p = .228).

Lastly, I used hierarchical regression analyses to test Hypothesis 3, which predicted that principal-teacher gender similarity moderates the effects of teachers’ trust in the principal on teachers’ commitment. Table 3 shows that teachers’ affective trust in the principal did not interact significantly with principal-teacher gender similarity to have an effect on teacher’s affective (see Table 3a) or continuance (see Table 3b) commitments to school. Additionally, teacher’s cognitive trust in the principal did not interaction with gender similarity to affect teacher’s affective commitment to the school (see Table 4a).

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, however, the interaction between teacher’s cognitive trust in the principal and principal-teacher gender similarity on teacher’s continuance commitment to school was significant (see Table 4b). Specifically, the positive main effect of principal-teacher gender similarity on teacher’s continuance commitment to school was found to be roughly the same size as the negative interaction effect (see Table 4b), so that the effect of gender similarity on continuance commitment is cancelled out by negative cognitive trust in principal. As shown in Fig. 2, the analysis of the simple slopes revealed that teachers’ cognitive trust in the principal affected their continuance commitment to school more positively under principal-teacher gender dissimilarity (dashed line; B = .643, t = 10.31, p < .001) than under gender similarity (solid line; B = .430, t = 11.79, p < .001).

Discussion

The present study is part of a limited body of knowledge in educational leadership research that focuses on gender and the understanding of its effects on aspects of organizational psychology. The study sheds light on the effects of principal-teacher gender similarity in the female-dominated primary education system in Israel with regard to teachers’ trust in the principal and teachers’ commitment. I explored three hypotheses to describe the effects of principal-teacher gender similarity on teachers’ trust in the principal and on the relationships between teachers’ trust in the principal and their organizational commitment.

The findings support the notion that gender is important in educational leadership research, and principal-teacher gender similarity was found to affect teachers’ work-related attitudes. First, I proposed that principal-teacher gender similarity influences levels of teachers’ trust. The results support the theoretical assumption of both affective and cognitive trust bases, consistent with relational demography theory (Sacco et al. 2003). Whereas the difference in affective trust in the principal is more likely to be the result of gender difference between teacher and principal, the difference in cognitive trust requires some explanation. Cognitive trust in a leader is not only about perceived credibility but also about perceived capability (McAllister 1995). Therefore, it is possible that gender dissimilarity leads to attributing a low perceived person-role fit (i.e., the match between one’s attributes and job demands; DeRue and Morgeson 2007) to male principals, possibly because the role of a principal in the female-dominated primary school system is viewed by female teachers as demanding feminine attributes.

Second, it has been suggested that the duration of relationship plays a role in moderating the link between principal-teacher gender similarity and trust in the principal. My analysis supports this hypothesis with regard to affective trust in the principal, but not to cognitive trust. The positive effect of principal-teacher gender similarity on teacher’s affective trust is largely countered by the duration of relationship so that a great part of the homophilic socio-psychosocial effect diminishes as the length of relationship increases. One explanation for this finding is linked with Duck’s (1977) filter theory, which argues that time enables individuals to shift their attention from superficial characteristics to deeper ones and, consequently, real-life experiences replace pre-existing gender-related assumptions. Another explanation is that new male principals at first adopt formal conduct, which becomes more personalized over time. Thus, because female teachers are more familiar with male principals’ authentic personalities, affective trust may be bolstered.

Third, I proposed that principal-teacher gender similarity moderates the associations between trust in the principal and teachers’ organizational commitment. The results indicate the presence of only one significant interactive effect: Under male principals, it was female teachers’ cognitive trust in principals that predicted more positively teachers’ continuance commitment. The positive effect of principal-teacher gender similarity on teachers’ continuance commitment was found to be contradicted by cognitive trust; thus, it seems that the homophily effect on continuance organizational commitment weakens with the strengthening of perceptions of managers as competent and reliable. This finding contrasts somewhat with the work of Carter et al. (2014), who found that gender dissimilarity did not have a moderating influence on the effects of supervisors’ transformational leadership on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors. Their study, however, used a sample of supervisors and employees from a range of industries that likely included more mixed-gender or masculine compositions.

The second interactive effect between principal-teacher gender similarity and teachers’ affective trust emerged as non-significant. This finding appears at odds with prior research, indicating that women tend to have more intimate relationships (Lowenthal and Haven 1968) and that they tend to ascribe more supportive meaning to interpersonal behaviors (Stokes and Wilson 1984; Vaux 1985). Therefore, it may be beneficial to further explore this interaction in the future to reconcile the contradiction.

Limitations and Future Research

My study has several limitations. First, data were collected in a system that espouses a certain educational policy. Forrester (2005) suggested that viewing primary school culture as feminine and characterized by mothering and nurturing values may be obsolete because of neoliberal policy changes. Since the early 2000s, Israel has embraced neoliberal evaluation governance and has integrated mandatory annual national testing into primary schools (Berkovich 2014). Blackmore (1996) indicated that market-oriented education reforms alter school roles and the fabric of principal-teacher relations, as well as may have different meanings for men and women. Therefore, explaining the way in which neoliberal policies influence the effects of principal-teacher gender similarity is important.

Second, my study is situated in a given cultural setting. Some scholars suggest that no discussion of gender is complete without taking into account national culture (Ayman and Korabik 2010). Because of historical traditions and contemporary security challenges, masculinity is dominant in Israeli society (Klein 1999). Moreover, within multicultural societies, such as Israel, multiple cultural groups subscribe to substantially different value systems and norms (e.g., liberal vs. conservative; religious vs. secular) (Yonah 2005). Culture is therefore likely to play a fundamental part in how gender identities are shaped, experienced, and enacted in the context of work relations and, for this reason, it is recommended that researchers replicate my study in other cultural settings.

Third, my study did not investigate principals’ and teachers’ gender roles (e.g., masculine, feminine, or androgynous orientations; see Hoffman and Borders 2001) or the gendered content of their identities (e.g., external indicators and behaviors; see Kelan 2010). These aspects deserve focused exploration because they may mediate some of the effects of gendered interactions uncovered in the present work. Fourth, my study focused on the primary education system. It is not clear to what extent my findings can be generalized to the secondary education system, in which the gender composition and culture are different.

Fifth, future work may benefit from taking into account additional variables, such as the age and career stage of the teachers, principals, or both. For example, prior research suggested that younger managers may ascribe less importance to trust (Barnett and Karson 1989), and that masculine- or feminine-typed managerial styles may change in the mid-career renewal process (Oplatka 2001). Finally, the researcher’s identity as a heterosexual male may have affected the choice of variables of interest. For example, the concept of organizational commitment touches upon masculine conceptions of “sacrificing” for the job, which together are responsible for the “glass ceiling” for women in organizations (Guillaume and Pochic 2009). Expanding the scope of the outcomes explored with reference to the effect of principal-teacher gender similarity is therefore advised.

Practice Implications

Leadership research on gender and on the dynamics it generates is required for producing practical knowledge about leadership (Ayman and Korabik 2010). The present findings are generally consistent with prior ones on gender similarity, but extend these to the setting of a primary education system that employs overwhelmingly female teachers. The findings have several practical implications. First, the insights of the study can be used to educate and mentor new male principals. Men in female-dominated occupations have been found to differ in their traits and values from those working in more traditional jobs (Chusmir 1990). But gender is known to influence men’s actions in nontraditional jobs where they tend to reconstruct the job in a manner that enhances its masculine aspects (Cross and Bagilhole 2002; Simpson 2004). This coping strategy assists men in gaining a dominant position and maintaining their masculine identity, which is challenged by their stigmatized association with a feminine occupation (Alvesson 1998). This type of reactive conduct, not always conscious, can lead to even lower trust in the principal and can harm teachers’ commitment to their school.

Second, my paper and findings can be used as material for team discussions in schools led by male principals. Such discussions can be expanded to encompass gendering practices (e.g., “said and done” versus “saying and doing”; see Martin 2003) and even work-life balance (see Smithson and Stokoe 2005). Third, the insights of my study can contribute to policymaking. A shortage of principals has become a policy problem in many Western counties (Barty et al. 2005; Papa Jr. and Baxter 2005; Williams 2001). This situation has encouraged policymakers to become more proactive and attract external applicants, often men, for the position of principal to fill the shortage and enhance the status of the profession. For example, in Israel retired military officers, mostly men, often start a second career as school principals (Schneider 2004). The scope of the phenomenon is unknown, but the present findings raise questions about whether this phenomenon is beneficial, particularly in primary schools. In the military, demographic similarity has been found to relate only weakly to employees’ satisfaction with their supervisor and with their continued work (Vecchio and Bullis 2001); as we have seen, in education its effect is different. Whereas the military is a male-dominated environment, in both gender composition and culture, primary education is a female-dominated environment (Allan 1994). Therefore, importing candidates for principalship, particularly men without any experience in a feminine or educational work setting, may have an adverse effect.

Conclusion

The present work is part of the stream of critical organizational psychology that regards individuals not as objective entities but as subjective potentials (Islam and Zyphur 2008; Rogers 2003). Therefore, the manner in which reality is socially constructed affects considerably the way in which individuals enact their identities (e.g., their external expressions, attitudes, and behaviors). My findings support the value of critical psychological exploration of educational leadership, specifically with regard to gender. It is puzzling why gender continues to be an overlooked issue in educational administration research. Perhaps it has to do with male dominance in educational administration research, which shapes the androcentrism of the field (Shakeshaft 1989). Consequently, not much is known about how gender affects the attitudes and actions of principals and teachers toward one another and toward the organization as a whole. This area of research is greatly underexplored and, at the same time, highly relevant to better understand leadership in education systems worldwide.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Allan, J. (1994). Anomaly as exemplar: The meanings of role-modeling for men elementary teachers. Dubuque: Tri-College Department of Education, Loras College.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1996). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(3), 252–276. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1996.0043.

Alvesson, M. (1998). Gender relations and identity at work: A case study of masculinities and femininities in an advertising agency. Human Relations, 51(8), 969–1005. doi:10.1177/001872679805100801.

Angle, H. L., & Perry, J. L. (1981). An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(1), 1–14. doi:10.2307/2392596.

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2008). What are the odds? How demographic similarity affects the prevalence of perceived employment discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 235–249. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.235.

Avery, D. R., Wang, M., Volpone, S. D., & Zhou, L. (2013). Different strokes for different folks: The impact of sex dissimilarity in the empowerment-performance relationship. Personnel Psychology, 66(3), 757–784. doi:10.1111/peps.12032.

Ayman, R., & Korabik, K. (2010). Leadership: Why gender and culture matter. American Psychologist, 65(3), 157–170. doi:10.1037/a0018806.

Barkol, R. (2005). Management of a school as a second career: The case of (retired) IDF officers- from command to management in the education system. In I. Kupferberg & E. Olshtain (Eds.), Discourse in education (pp. 306–331). Tel Aviv: The Mofet Institute. (Hebrew).

Barnett, J. H., & Karson, M. J. (1989). Managers, values, and executive decisions: An exploration of the role of gender, career stage, organizational level, function, and the importance of ethics, relationships and results in managerial decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(10), 747–771. doi:10.1007/BF0038377.

Barty, K., Thomson, P., Blackmore, J., & Sachs, J. (2005). Unpacking the issues: Researching the shortage of school principals in two states in Australia. The Australian Educational Researcher, 32(3), 1–18. doi:10.1007/BF03216824.

Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1996). Development of a leader-member exchange: A longitudinal test. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1538–1567. doi:10.2307/257068.

Berkovich, I. (2014). Neo-liberal governance and the “new professionalism” of Israeli principals. Comparative Education Review, 58(3), 428–456. doi:10.1086/676403.

Blackmore, J. (1996). Doing “emotional labour” in the education market place: Stories from the field of women in management. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 17(3), 337–349. doi:10.1080/0159630960170304.

Bogler, R., & Somech, A. (2004). Influence of teacher empowerment on teachers’ organizational commitment, professional commitment and organizational citizenship behavior in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(3), 277–289. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2004.02.003.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1992). Leading and managing: Effects of context, culture, and gender. Educational Administration Quarterly, 28(3), 314–329. doi:10.1177/0013161X92028003005.

Bryk, A., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Carter, M. Z., Mossholder, K. W., Feild, H. S., & Armenakis, A. A. (2014). Transformational leadership, interactional justice, and organizational citizenship behavior: The effects of racial and gender dissimilarity between supervisors and subordinates. Group & Organization Management, 39(6), 691–719. doi:10.1177/1059601114551605.

Chusmir, L. H. (1990). Men who make nontraditional career choices. Journal of Counseling & Development, 69(1), 11–16. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01446.x.

Cross, S., & Bagilhole, B. (2002). Girls’ jobs for the boys? Men, masculinity and non-traditional occupations. Gender, Work and Organization, 9(2), 204–226. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.00156.

DeRue, D. S., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Stability and change in person-team and person-role fit over time: The effects of growth satisfaction, performance, and general self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1242–1253. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1242.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611.

Duck, S. W. (1977). The study of acquaintance. Farnborough: Saxon House.

Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Johnson, B. T. (1992). Gender and leadership style among school principals: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly, 28(1), 76–102. doi:10.1177/0013161X92028001004.

Ely, R. J., Ibarra, H., & Kolb, D. M. (2011). Taking gender into account: Theory and design for women’s leadership development programs. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(3), 474–493. doi:10.5465/amle.2010.0046.

Foley, S., Linnehan, F., Greenhaus, J. H., & Weer, C. H. (2006). The impact of gender similarity, racial similarity, and work culture on family-supportive supervision. Group & Organization Management, 31(4), 420–441. doi:10.1177/1059601106286884.

Forrester, G. (2005). All in a day’s work: Primary teachers “performing” and “caring.” Gender and Education, 17(3), 271–287. doi:10.1080/09540250500145114.

Forsyth, P. B., Adams, C. M., & Hoy, W. K. (2011). Collective trust: Why schools can't improve without it. New York: Teachers College Press.

Goldberg, C. B., Riordan, C., & Schaffer, B. S. (2010). Does social identity theory underlie relational demography? A test of the moderating effects of uncertainty reduction and status enhancement on similarity effects. Human Relations, 63(7), 903–926. doi:10.1177/0018726709347158.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. doi:10.2307/2092623.

Guillaume, C., & Pochic, S. (2009). What would you sacrifice? Access to top management and the work–life balance. Gender, Work & Organization, 16(1), 14–36. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00354.x.

Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(3), 329–352. doi:10.1080/0305764032000122005.

Handford, V., & Leithwood, K. (2013). Why teachers trust school leaders. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(2), 194–212. doi:10.1108/09578231311304706.

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., & Bell, M. P. (1998). Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 96–107. doi:10.2307/256901.

Hoffman, R. M., & Borders, L. D. (2001). Twenty-five years after the Bem Sex-Role Inventory: A reassessment and new issues regarding classification variability. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(1), 39–55. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2001-06272-004.

Hoy, W. K., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). The conceptualization and measurement of faculty trust in schools. In W. K. Hoy & M. F. DiPaola (Eds.), Essential ideas for the reform of American schools (pp. 87–114). Greenwich: Information Age.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hulpia, H., & Devos, G. (2010). How distributed leadership can make a difference in teachers’ organizational commitment? A qualitative study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 565–575. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.08.006.

IISL. (2012). School principals: Situation report and future trends. Jerusalem: Israel Institute for School Leadership [In Hebrew].

Islam, G., & Zyphur, M. J. (2008). Concepts and directions in critical industrial/organizational psychology. In D. Fox, I. Prilleltensky, & S. Austin (Eds.), Critical Psychology: An Introduction (2nd ed., pp. 110–135). London: Sage Publications.

Johnson, R. E., Chang, C.-H., & Rosen, C. C. (2010). “Who I am depends on how fairly I’m treated”: Effects of justice on self-identity and regulatory focus: Justice and motivation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(12), 3020–3058. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00691.x.

Kelan, E. K. (2010). Gender logic and (un)doing gender at work. Gender, Work & Organization, 17(2), 174–194. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00459.x.

Klein, U. (1999). “Our best boys”: The gendered nature of civil-military relations in Israel. Men and Masculinities, 2(1), 47–65. doi:10.1177/1097184X99002001004.

Koh, W. L., Steers, R. M., & Terborg, J. R. (1995). The effects of transformational leadership on teacher attitudes and student performance in Singapore. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(4), 319–333. doi:10.1002/job.4030160404.

Lee, V. E., Smith, J. B., & Cioci, M. (1993). Teachers and principals: Gender-related perceptions of leadership and power in secondary schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 15(2), 153–180. doi:10.3102/01623737015002153.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2005). A review of transformational school leadership research 1996–2005. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 177–199. doi:10.1080/15700760500244769.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Stilwell, D. (1993). A longitudinal study on the early development of leader-member exchanges. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 662–674. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.662.

Lowenthal, M. F., & Haven, C. (1968). Interaction and adaptation: Intimacy as a critical variable. American Sociological Review, 33(1), 20–30. doi:10.2307/2092237.

Martin, P. Y. (2003). “Said and done” versus “saying and doing”: Gendering practices, practicing gender at work. Gender & Society, 17(3), 342–366. doi:10.1177/0891243203017003002.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59. doi:10.2307/256727.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc..

Moreland, R. L., & Levine, J. M. (2002). Socialization and trust in work groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 5(3), 185–201. doi:10.1177/1368430202005003001.

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism and turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224–247. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1.

Moye, M. J., Henkin, A. B., & Egley, R. J. (2005). Teacher-principal relationships: Exploring linkages between empowerment and interpersonal trust. Journal of Educational Administration, 43(3), 260–277. doi:10.1108/09578230510594796.

NCES. (2013a). Characteristics of public and private elementary and secondary school teachers in the United States: Results from the 2011–12 schools and staffing survey. Washington: U.S. Department of Education, NCES.

NCES. (2013b). Characteristics of public and private elementary and secondary school principals in the United States: Results from the 2011–12 schools and staffing survey. Washington: U.S. Department of Education, NCES.

O'Conor, L. (2015, February 11). Where are all the female headteachers? The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com.

Oplatka, I. (2001). ‘I changed my management style’: The cross-gender transition of women headteachers in mid-career. School Leadership & Management, 21(2), 219–233. doi:10.1080/13632430120054781.

Papa Jr., F., & Baxter, I. A. (2005). Dispelling the myths and confirming the truths of the imminent shortage of principals: The case of New York State. Planning and Changing, 36(3/4), 217–234. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ737684.

Paton, G. (2013, February 5). Teaching in primary schools ‘still seen as a woman’s job.’ The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk.

Pithers, R. T., & Soden, R. (2000). Critical thinking in education: A review. Educational Research, 42(3), 237–249. doi:10.1080/001318800440579.

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5), 603–609. doi:10.1037/h0037335.

Price, H. E. (2012). Principal–teacher interactions: How affective relationships shape principal and teacher attitudes. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(1), 39–85. doi:10.1177/0013161X11417126 .

Rogers, W. S. (2003). Social psychology: Experimental and critical approaches. Maiddenhead: Open University Press.

Sacco, J. M., Scheu, C. R., Ryan, A. M., & Schmitt, N. (2003). An investigation of race and sex similarity effects in interviews: A multilevel approach to relational demography. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 852–865. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.852.

Sanchez-Hucles, J. V., & Davis, D. D. (2010). Women and women of color in leadership: Complexity, identity, and intersectionality. American Psychologist, 65(3), 171–181. doi:10.1037/a0017459.

Schneider, A. (2004). Transforming retired military officers into school principals in Israel (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Leicester, Leicester, England.

Shakeshaft, C. (1989). The gender gap in research in educational administration. Educational Administration Quarterly, 25(4), 324–337. doi:10.1177/0013161X89025004002.

Sheldon, M. E. (1971). Investments and involvements as mechanisms producing commitment to the organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(2), 143–150. doi:10.2307/2391824.

Simpson, R. (2004). Masculinity at work: The experiences of men in female dominated occupations. Work, Employment and Society, 18(2), 349–368. doi:10.1177/09500172004042773.

Smithson, J., & Stokoe, E. H. (2005). Discourses of work-life balance: Negotiating “genderblind” terms in organizations. Gender, Work and Organization, 12(2), 147–168. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2005.00267.x.

Steers, R. M. (1977). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(1), 46–56. doi:10.2307/2391745.

Stokes, J. P., & Wilson, D. G. (1984). The inventory of socially supportive behaviors: Dimensionality, prediction, and gender differences. American Journal of Community Psychology, 12(1), 53–69. doi:10.1007/BF00896928.

Tarter, C. J., & Hoy, W. K. (1988). The context of trust: Teachers and the principal. The High School Journal, 72(1), 17–24. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40364817?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Tarter, C. J., Bliss, J. R., & Hoy, W. K. (1989). School characteristics and faculty trust in secondary schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 25(3), 294–308. doi:10.1177/0013161X89025003005.

Tetrick, L. E., & Farkas, A. J. (1988). A longitudinal examination of the dimensionality and stability of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 48(3), 723–735. doi:10.1177/0013164488483021.

The World Bank. (2017, July 12). Primary education, teachers (% female), 2014: Israel. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.TCHR.FE.ZS?locations=IL.

Tschannen-Moran, M. (2004). Trust matter: Leadership for successful schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Turban, D. B., Dougherty, T. W., & Lee, F. K. (2002). Gender, race, and perceived similarity effects in developmental relationships: The moderating role of relationship duration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(2), 240–262. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1855.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Hoboken: Blackwell.

Valmer, T. (2012, July 25). 15 minutes and you got the job: This is how school principals are choose. YNET. (Hebrew). Retrieved from http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-4259494,00.html.

Vaux, A. (1985). Variations in social support associated with gender, ethnicity, and age. Journal of Social Issues, 41(1), 89–110. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01118.x.

Vecchio, R. P., & Bullis, R. C. (2001). Moderators of the influence of supervisor–subordinate similarity on subordinate outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 884–896. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.884.

Vinkenburg, C. J., van Engen, M. L., Eagly, A. H., & Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C. (2011). An exploration of stereotypical beliefs about leadership styles: Is transformational leadership a route to women’s promotion? The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 10–21. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.003.

Wahlstrom, K. L., & Louis, K. S. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: The roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 458–495. doi:10.1177/0013161X08321502.

Williams, T. R. (2001). Unrecognized exodus, unaccepted accountability: The looming shortage of principals and vice principals in Ontario public school boards. Toronto: Ontario Principals' Council.

Yang, J., Mossholder, K. W., & Peng, T. K. (2009). Supervisory procedural justice effects: The mediating roles of cognitive and affective trust. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(2), 143–154. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.01.009.

Yonah, Y. (2005). Israel as a multicultural democracy: Challenges and obstacles. Israel Affairs, 11(1), 95–116. doi:10.1080/1353712042000324472.

Zeinabadi, H. (2014). Principal-teacher high-quality exchange indicators and student achievement: Testing a model. Journal of Educational Administration, 52(3), 404–420. doi:10.1108/JEA-05-2012-0056.

Zeinabadi, H., & Salehi, K. (2011). Role of procedural justice, trust, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) of teachers: Proposing a modified social exchange model. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1472–1481. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.387.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berkovich, I. Effects of Principal-Teacher Gender Similarity on Teacher’s Trust and Organizational Commitment. Sex Roles 78, 561–572 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0814-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0814-3