Abstract

Prejudicial attitudes and discrimination toward gay men is a common social problem in Turkey as it is in many other countries. It is important to understand the reasons behind the prejudice against gay men in a sexist and Muslim country, Turkey. The purpose of the study was to predict attitudes toward gay men with ambivalent attitudes toward men (hostility toward men, and benevolence toward men), questioning religion, and gender differences. Three hundred seventy-two (91 male and 281 female) heterosexual Muslim students from several universities in Ankara completed Attitudes toward Gay men Scale, Ambivalence toward Men Inventory, and Questioning Religion Scale. The mean age of the participants was 22.79 (SD = 3.07). Results, in general, demonstrated that gender differences, benevolence toward men, and questioning religion predicted attitudes toward gay men. Men were more prejudiced against gay men than women. Participants who scored high on benevolence toward men and low on questioning religion were also more prejudiced against gay men than those who scored low on benevolence toward men and high on questioning religion. Further, gender differences was a moderator variable for the association between hostility toward men and attitudes toward gay men. When the regression analyses were performed separately for female and male participants, it was seen that hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, and questioning religion predicted attitudes toward gay men for women whereas for men only benevolence toward men and questioning religion predicted attitudes toward gay men. Results were discussed in the light of relevant literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prejudice against gay men has been examined by many researchers in various countries for many years. Researchers have tried to find out the social constructs that predict attitudes toward gay men. Some of the most examined social variables are social contact with gay persons (e.g., Aguero et al. 1984 [the USA]; Herek and Capitanio 1996 [the USA]; Steffens and Wagner 2004 [Germany]), right wing authoritarianism (Johnson et al. 2011 [the USA]), sexism (e.g., Chonody et al. 2013 [the USA]), traditional gender roles (Wellman and McCoy 2014 [the USA]; Whitley 1987 [the USA]), and religion (Chonody et al. 2013 [the USA]; Ford et al. 2009 [the USA]). As it will be discussed in the next pages, it is well known in the literature that negative attitudes toward women are positively related with negative attitudes toward gay men (e.g., Chonody et al. 2013 [the USA]; Sakallı 2002 [Turkey]) but what about ambivalent attitudes toward men including hostility and benevolence toward men? How do these variables and their interaction with gender differences may predict attitudes toward gay men? In addition, how ambivalent attitudes toward religion, as questioning it, may expand prediction of attitudes toward gay men?

It is important to understand how these ambivalent attitudes (namely ambivalence toward men and questioning religion), and gender differences may influence prejudice against gay men in Muslim countries because even though Islam prohibits it, homosexuality exists in Muslim countries (Habib 2007; Siraj al-Haqq Kugle 2010). Prejudice and discrimination against gay men in social, economic and political areas are also important problems in Muslim countries. Studies on prejudice and discrimination toward gay men in Turkey have demonstrated that gay men are exposed to harassment and violence (Öztürk and Kındap 2011). Men are more prejudiced toward gay men than women (Sakallı and Uğurlu 2001). Gay men do not feel comfortable in letting their families and relatives to know about their sexual orientation, and they are scared of being fired from their job in the cases of coming out of the closet (Öztürk and Kozacıoğlu 1998). They also do not want to be identified as gay men (Özyeğin 2012), and experience internalized homophobia (Okutan et al. 2015). Consequently, studying attitudes toward gay men may be helpful to researchers and others wanting to better understand the causes of prejudice in order to decrease the prejudice and discrimination in predominantly Muslim country, Turkey. Further, theoretically, ambivalent attitudes toward men and religion may carry both positive and negative feelings, beliefs and tendencies about the attitude object (e.g., Fiske and Glick 1995), and consequently may result in different level of prejudice. Therefore, we aimed to explore how much these ambivalent attitudes, namely benevolence toward men, hostility toward men, and questioning religion predict attitudes toward gay men through regression analyses; and how gender differences may influence the association among benevolence toward men, hostility toward men, questioning religion and attitudes toward gay men in a Muslim culture through moderation analysis.

Ambivalence Toward Men

Glick and his colleagues (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1997; Glick et al. 1997) agreed that sexism includes the endorsement of traditional gender roles, but argued that the concept also consists of hostile and benevolent attitudes toward women. According to these researchers (see Glick and Fiske 1996 [the USA]), hostile sexism represents women as inferior and justifies male power and traditional gender roles. Benevolent sexism, however, idealizes women in traditional female roles and recognizes men’s dependence on women in interpersonal relationships. Later on these researchers (Glick and Fiske 1999 [the USA]) expanded the idea of sexism to include the concepts of ambivalence toward men which contains the hostility toward men, and benevolence toward men. It is these two more recent components of sexism that we focus on in this study as predictors of negative attitudes toward gay men.

According to Glick and his colleagues (Glick and Fiske 1999; Glick et al. 2004), hostility toward men consists of resentment of paternalism, compensatory gender differentiation, and heterosexual hostility. Resentment of paternalism is about feelings of anger and dislike toward the dominant group, men. It results from the beliefs that men have power over women, and men always fight for greater control in society. Compensatory gender differentiation reflects the attribution of some negative traits to men. It views men inferior in some ways in order to compensate for the negative stereotyping of women such as men would be lost without women to guide them. Heterosexual hostility, however, covers to the resentment of men’s sexual aggressiveness and control over women in romantic relationships. It represents the beliefs that when in position of power, men sexually harass women (Glick and Fiske 1999).

On the contrary, benevolence toward men includes beliefs that accept more traditional gender roles and power relations. The beliefs suggest that women admire men and women are weaker than men. These beliefs stem from three sources; maternalism, complementary gender differentiation, and heterosexual attraction. Maternalism presumes a weakness in the other gender. It leads women to feel that men need their nurturance and protectiveness at home. Complementary gender differentiation presents the belief that that women are dependent, incompetent, less ambitious and less assertive than men (e.g., Deaux and Lewis 1984; Eagly and Steffen 1984 [the USA]). Each gender posseses a sets of strenghts and weakness. People balance them in a way that they feel good about their own group. For example, women may feel admiration toward men because of their higher status in society. Thus, masculine and feminine stereotypes are complementary (Jost and Kay 2005; Kay and Jost 2003 [the USA]). As shown by Jost and Kay (2005), exposure to complementary gender stereotypes may lead people to justify the current state of gender relations. Finally, heterosexual attraction is about women’s interdependence on men in romantic relationships. It suggests that a woman is incomplete without the love of a man. Consequently, benevolence toward men may serve functions as justifying the gender roles and heterosexual relationship; by allowing women to maintain a positive self-image as taking care of men who are not competent enough in domestic works, and by reducing women’s resistance to patriarchal system (Glick and Fiske 1999).

In short, hostility toward men only emphasizes the beliefs that men always have advantages relevant to power. However, benevolence toward men suggests acceptance of traditional gender roles, and consequently it indirectly supports sexism toward women because it helps both gender to justify the existing gender system. Benevolence toward men also offers the beliefs that men and women need each other for intimate relations (Glick and Fiske 1999). It seems that benevolence toward men as compared to hostility toward men consists of the beliefs that heterosexual relationship and romance between men and women are the appropriate ones. It suggests that the system of heterosexual relationship should be maintained. Consequently, people who are high on benevolence toward men may score higher on negative attitudes toward gay men because they may believe in that gay men are violating the rules in terms of traditional gender differentiation, and heterosexual attraction as suggested by earlier studies in the USA (e.g., Herek 1988). Because of these reasons, benevolence toward men may strongly predict prejudiced attitudes toward gay men, as compared to hostility toward men.

Questioning Religion

As well as benevolence toward men, religion may support the gender specific system and heterosexual intimacy. Religion is found to be related with gender role expectations in various countries (e.g., Burn and Busso 2005 [the USA]; Gaunt 2012 [Israel]; Mikolajczak and Pietrzak 2014 [Poland]; Taşdemir and Sakallı-Uğurlu 2010 [Turkey]), and with attitudes toward homosexuality (e.g., Ford et al. 2009 [the USA]; Saraç 2015 [Turkey]). Some studies (e.g., Hunsberger et al. 1999; James et al. 2011) have also focused on the association between being affiliated with Islam, and prejudice against gay men, but in these studies the participants were Muslim people who live in the USA and Europe as a sample. Similarly, empirical studies in Turkish culture have also shown that religiosity level is positively correlated with negative attitudes toward gay men (Gelbal and Duyan 2006; Saraç 2015). However, there is no study focusing on whether questioning religion may predict attitudes toward gay men in Muslim countries, Turkey.

Therefore, we plan to examine the association between attitudes toward gay men and how people perceive religion and whether they question it or not. As researchers (e.g., Herek 1988 [the USA]; Hojat et al. 1999 [using Iranian men and women in the United States and Iran]) argued, people may show prejudice and discrimination against gay men because they may think that gay men are violating their religion rules. However, if people do not accept their religion as it is and question the rules of their religion, their perception and attitudes toward gay men may differ. As research on quest orientation to religion has demonstrated quest orientation to religion is negatively associated with prejudice against homosexuals because quest oriented people are found to be flexible, nondogmatic, and open-minded in the USA (Bassett et al. 2005; Batson et al. 1999; Fulton et al. 1999; Hunsberger and Jackson 2005). Similarly, it is possible to expect that people who are more likely to question their religion may present less negative attitudes toward gay men in a Muslim country, Turkey.

At this point we should note that even though Turkey is a Muslim country where around 99.2 % of its population is indicated as Muslim (Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı 2014), it is a secular and democratic country since the establishment of Turkish Republic in 1923. As compared to other Muslim nations, Turkey has aimed to achieve a radical break with ottoman Islam by carrying out several reforms, initiated by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic (Wasti et al. 2000). Turkey seeks for modernization and joining in the European Union. Because of the secular and democratic view, some Turkish people may have a perception that it is possible to question their religion. In addition, some Turkish people may be under the influence of non-Muslim countries through the TV, social media, and social interactions, and so they may change their strict beliefs about religion and Islamic rules. They may question their religion.

Gender Differences

Finally, as many correlational and meta-analyses studies have demonstrated gender differences may reduce prejudice against gay men. Women show less prejudice against gay men (e.g., Kite 1984 [the USA]; Sakallı and Uğurlu 2001[in Turkey]). Considering its importance, gender differences is included in the present study to examine how gender differences may influence the association between hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, and attitudes toward gay men. As earlier findings on ambivalence toward men demonstrated, women scored lower on benevolence toward men and higher on hostility toward men than did men. Thus, women score more hostility toward men than do men, and men use more benevolence toward men than do women (Glick and Fiske 1999). The gender differences may also influence the associations among hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, and attitudes toward gay men because men would have lower hostility toward men. The present study aims at exploring the associations. It is possible that hostility toward men and benevolence toward men may function differently for women and men to explain their attitudes toward gay men.

The Aim and Hypotheses of the Present Study

In summary, the present paper aims at examining whether hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, and questioning religion predict attitudes toward gay men in a Muslim country, Turkey. In addition to the main variables, consistent with earlier studies (see Kite 1984), the study searches how gender of participants would predict attitudes toward gay men and further explores whether gender differences play a moderator role among independent variables and attitudes toward gay men.

Relying on the previous studies cited in the introduction, the hypotheses are

-

Hypothesis 1)- Benevolence toward men, which strongly justifies and supports heterosexual intimacy and gender roles (Glick and Fiske 1999), would predict attitudes toward gay men positively and strongly than hostility toward men, which covers the beliefs that men always have advantages relevant to power.

-

Hypotheses 2)-

-

a)-

In general, gender differences would predict attitudes toward gay men. Women would hold less negative attitudes toward gay men than men as consistent with earlier studies in the USA (e.g., Kite 1984) and Turkey (e.g., Sakallı and Uğurlu 2001).

-

b)-

Also, the current study explores whether gender differences can play a moderator role on the relationship between hostility toward men and attitudes toward gay men; and benevolence toward men and attitudes toward gay men.

-

a)-

-

Hypothesis 3)- Questioning religion would predict attitudes toward gay men negatively for both women and men.

In order to test these hypotheses, regression analyses were performed. First of all, all independent variables were entered into equation to predict attitudes toward gay men. Then, a moderation analysis was conducted and separate regression analyses were computed for women and men.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample of the study consisted of 378 (284 females and 94 males) college students from several universities in Turkey. Four students who indicated that they did not have any religion affiliations, and two students who did not answer religion affiliation question were excluded from the data. The final sample was 372 (281 females and 91 males) heterosexual Muslim students. The mean of the participants was 22.79 (SD = 3.07). The range of age is between 18 and 30. The mean ages for women and men were 22.70 (SD = 3.08) and 23.05 (SD = 3.05) respectively. No other demographic data was available.

Data was collected through an online survey system. The survey link was send to staffs of Introduction to Psychology and Introduction to Social Psychology courses in Middle East Technical University, Ankara University and Hacettepe University, which were located in Ankara, the capital city of Turkey. The participants were ensured that their responses would be confidential and used only for research purposes. After completing the questionnaire, participants were provided with a written debriefing form. Students from Middle East Technical University and Ankara University were given credit for their participation since these universities use bonus system in their elective courses. The remaining Turkish students willingly participated in the study without any bonus.

Measures

Attitudes Toward Gay Men Scale

Five items from Herek’s (1988, 1998) Attitudes toward Lesbians and Gay Men was used. The scale was adapted into Turkish by Duyan and Gelbal (2004). Attitudes toward gay men included the following five items “Sex between two men is just plain wrong,” “I think that male homosexuals are disgusting,” “Male homosexuality is a natural expression of sexuality in men,” “Male homosexuality is a perversion,” and “Male homosexuality is merely a different kind of lifestyle that should be not be condemned.” (You may see the Turkish wording of the scale in the Appendices).

Items were rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores on these measures were transformed so that higher scores represented more negative attitudes toward gay men. Cronbach’s alpha was .78 for attitudes toward gay men for the present study.

Ambivalence Toward Men Scale

Ambivalence Toward Men Scale (Glick and Fiske 1999) consists of two subscales that assess hostility toward men and benevolence toward men. The scale was adapted into Turkish by Sakallı-Uğurlu (2008). Few examples of hostility toward men are as following: “Men will always fight to have greater control in society than women,” and “Most men sexually harass women, even if only in subtle ways, once they are in a position of power over them.” Few examples of benevolence toward men are “Women are incomplete without men,” and “A woman will never be truly fulfilled in life if she doesn’t have a committed, long-term relationship with a man.” (You may see the whole scale and the Turkish wording of it in the Appendices).

Items were rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores on these items were transformed so that higher scores represented more sexist attitudes toward men. Cronbach’s α for hostility toward men and benevolence toward men were .84 and .86 respectively for the present study.

Questioning Religion Scale

Questioning religion was measured with the following six items: “I cannot accept my religion the way it is presented without questioning,” “I question the rules of my religion and practice the religion according to my own understanding,” “As I grow and change, my religion also grows and changes with me,” “No system of religious belief is valid for everyone or can provide absolute rules,” “As a believer, I think religious rules can be changed and adapted to current times,” and “I think that being skeptical about my religion helps me to expand my horizons.” (You may see the Turkish wording of the scale in the Appendices). These items were chosen from a pool of items which consists of several items from published religious orientation scales (e.g., Öner-Özkan 2007 [Turkey]). After conducting several factor analyses on the item pool, it was decided that the six items measured the examined variable the best. Factor analysis for the six items showed that 46.76 % of variance was explained by the data. Loadings ranged from .57 to .75. Cronbach’s alpha was .75 for the sample.

Items were rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores on these measures were transformed so that higher scores represented more questioning religion.

Demographic Information Form

Participants were asked to indicate their gender, age, religious affiliation, and sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual). Only self-described heterosexuals and Muslim were included in the present study.

Results

Gender Differences on Study Variables

A one-way MANOVA was performed to test gender differences in hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, questioning religion and attitudes toward gay men. The analysis demonstrated a significant gender effect, F (3, 368) = 66.86, p < .001, Wilks’ Lambda = .647. Results showed significant gender differences in attitudes toward gay men, F (1, 370) = 30.31, p < .001, partial eta squared = .076, in hostility toward men, F (1, 370) = 51.15, p < .001, partial eta squared = .121, and in benevolence toward men F (1, 370) = 41.09, p < .001, partial eta squared = .100 (see Table 1). Specifically, men (M = 3.77) scored higher than women (M = 3.24) on attitudes toward gay men. Similarly, men (M = 3.86) scored higher than women (M = 3.19) on benevolence toward men, whereas men (M = 3.53) scored lower than women (4.18) on hostility toward men. Finally, men (M = 3.68) scored lower than women (M = 4.23) on questioning religion.

The results supported the expectation (Hypotheses 2a) that women would present less negative attitudes toward gay men than men as consistent with earlier studies in the USA (e.g., Kite 1984) and Turkey (e.g., Sakallı and Uğurlu 2001).

Correlates of Attitudes Toward Gay Men

Table 1 also reports zero-order correlations among the variables, computed separately for women and men. Results showed that hostility toward men and benevolence toward men were moderately positively correlated for men (r = .35) and women (r = .53). As it is seen, the value of the correlation was higher for women. In addition, benevolence toward men was positively and significantly correlated with attitudes toward gay men for both men (r = .25) and women (r = .37), whereas hostility toward men was only statistically significant with attitudes toward gay men for women (r = .30). Interestingly, for men, hostility toward men was not significantly correlated with attitudes toward gay men. Finally, questioning religion was negatively and significantly correlated with attitudes toward gay men for both women (r = −.29) and men (r = −.22). Questioning religion was also negatively correlated with benevolence toward men for women (r = −.25, see Table 1 for these correlations).

Predicting Attitudes Toward Gay Men with Benevolence Toward Men, Hostility Toward Men, Questioning Religion, and Gender of the Participants

First of all, we checked for potential multicollinearity among the predictors by calculating Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). As a rule of thumb, multicollinearity does not pose a threat to multiple regressions if the VIF is less than 10 (O’Brien 2007) or, more conservatively, less than 5 (Alauddin and Son Ngheim 2010). Results showed that there were no multicollinearity problems because VIF values were between 1.03 and 1.53.

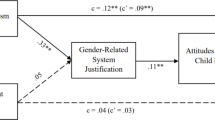

In order to test three hypotheses (that benevolence toward men, gender of the participants, and questioning religion would predict attitudes toward gay men), a standard multiple regression analysis was performed. Results indicated that benevolence toward men (β = .27, t = 4.69, p < .01), questioning religion (β = −.21, t = −4.33, p < .01), and gender of the participants (β = .17, t = 3.04, p < .01) significantly predicted attitudes toward gay men, R 2 = .22, F (4, 367) = 27.54, p < .01. Hostility toward men (β = .09, t = 1.58, ns) did not predict attitudes toward gay men. The results supported the expectations (Hypotheses 1, 2a, and 3).

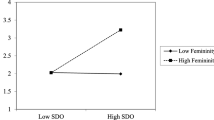

Then, in order to explore the moderator effect of gender differences on the relationship among predictors and dependent variable (including hypotheses 2b), a hierarchical regression was computed in which centered versions of all predictors (hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, questioning religion) and participants’ gender (female = 0, male = 1) were simultaneously entered at Step 1 to predict attitudes toward gay men. Step 2 added two-way interactions between participant’s gender and each of the predictors (hostility toward men, benevolence toward men, and questioning religion). As presented in the previous paragraph, at Step 1, the regression revealed the above values (see also Table 2). Step 2 results showed that the only significant interaction was gender differences X hostility toward men (ß = −.39, p < .01). The other interactions were not statistically significant (for gender differences X benevolence toward men ß = .08, ns, gender differences X questioning religion ß = .03, ns, see Table 2).

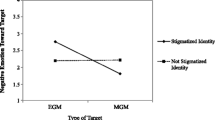

The significant gender differences X hostility toward men interaction showed that there is a gender moderation effect on the relationship between hostility toward men and attitudes toward gay men. To better understand the interactive effect of gender differences X hostility toward men, we conducted separate regressions for male and female participants (see Table 3). For women, all predictors were significant. For men, however, benevolence toward men and questioning religion remained significant predictors of attitudes toward gay men, whereas hostility toward men did not. The regressions demonstrated that women’s attitudes toward gay men were influenced by the level of hostility toward men. Women who had lower scores on hostility toward men scored lower on negative attitudes toward gay men than those women who had higher scores on hostility toward men.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to search whether ambivalent attitudes toward men (as hostility toward men and benevolence toward men), gender of the participants, and questioning religion predict attitudes toward gay men in a sample of heterosexual Muslim participants in Turkey. The findings of the descriptive calculations demonstrated that participants scored 3.37 on attitudes toward gay men on a 6 point scale, suggesting that they had slightly negative attitudes toward gay men. As it will be discussed later, results also showed that men scored higher than women on attitudes toward gay men. Men also scored higher than women on benevolence toward men, whereas women scored higher than men on hostility toward men. The results supported the argument of Glick and Fiske (1999) that women presented more hostility but less benevolence toward men, but men showed ingroup bias (less hostility but more benevolence). Finally, women also scored higher than men on questioning religion.

In order to test main hypotheses of the present study, a regression analysis was performed. The results revealed that benevolence toward men, gender differences, and questioning religion significantly predicted attitudes toward gay men. However, hostility toward men did not predict attitudes toward gay men. The results supported hypothesis 1, 2a, and 3. As mentioned in the introduction part, benevolence toward men is about acceptance of traditional gender roles and of power relations. People who score high on benevolence toward men agree that intimacy and romance can be between men and women, and that men and women need each other. Believing in benevolence toward men ideologies, people may state that women and men should keep their existing gender roles, and that heterosexual relationship between men and women are the appropriate ones in their society. Thus, they justify the existing system about gender roles and heterosexual intimacy. They support the maintenance of the current gender role system as presented by Jost and Kay (2005). It is possible to argue that the system justification function of benevolence toward men may lead people to think that gay men violate the traditional gender differentiation, and heterosexual attraction and that gay men should not be approved or liked (e.g., Herek 1988).

Further, gender differences also predicted attitudes toward gay men. As expected by the hypothesis 2a, women scored lower on attitudes toward gay men than did men. This result was also consistent with earlier studies in the USA (Kite 1984) and Turkey (Sakallı 2002; Saraç 2015). As mentioned by Sakallı (2002), there may be a perception that homosexuals are usually men, not women. The perception might lead men to hold more negative attitudes toward gay men than did women because individuals in general tend to be less tolerant of homosexuals of their own sex (Milham et al. 1976; Whitley 1987). In a sexist (e.g., Kandiyoti 1988) and Muslim country, Turkish men might easily access an image of male homosexuals and therefore represent higher scores on negative attitudes toward gay men.

As stated in the hypothesis 2b, we also explored whether gender differences could be a moderator on the relationship between each predictors and dependent variable. Moderation analyses demonstrated that gender differences was not a moderator on the relationship between benevolence toward men and attitudes toward gay men. The results may suggest that for both gender benevolence toward men ideologies may be used to justify the existing gender roles and heterosexual relationship. Benevolence toward men may allow women to provide a positive ingroup identification and men to support the dominant position (Glick and Fiske 1999).

The gender differences X hostility toward men interaction was significant in the moderation analysis. The result showed that gender differences play a moderator role on the relationship between hostility toward men and attitudes toward gay men. Then, further separate regression analyses for women and men were conducted. Results revealed that as well as benevolence toward men and questioning religion, hostility toward men predicted attitudes toward gay men for women but not for men. Thus, for women, higher scores on hostility toward men were associated with more negative attitudes toward gay men. As stated earlier, hostility toward men mainly focuses on the issues that resentment of paternalism (e.g., men have the power in societies), compensatory gender differentiation (e.g., men are weak for domestic works), and heterosexual hostility against men (e.g., men can easily harass women). It seems that men did not relate the hostility toward men beliefs with attitudes toward gay men. They also scored lower on hostility toward men than women. However, for women, hostility toward men seems to be associated with attitudes toward gay men. As mentioned earlier, hostility toward men covers the beliefs that when in position of power, men sexually harass women. Women who are high on hostility toward men may also perceive that gay men’s sexual advances to other men may create problems of sexual harassment for heterosexual men. It is also possible to argue that women who approach men with heterosexual hostility may project their hostility to gay men. Future studies may be conducted to examine whether the same result can be replicated or not. Future studies may also use experimental methods to test whether hostility toward men or benevolence toward men may be the causes of attitudes toward gay men.

Furthermore, as expected in the hypothesis 3, questioning religion was an important predictor of attitudes toward gay men for both men and women. Participants who were questioning their religion more had lower scores on negative attitudes toward gay men. Thus, people who question the rules of their religion are more likely to be less prejudiced against gay men. It seems that the participants who question their religion tend to be skeptical about it and they are open to changes. Because of being open-minded and flexible, they may tend to show less negative attitudes toward gay men. The result from a Muslim country, Turkey, is consistent with earlier findings showing negative correlation between quest religiosity and prejudice against homosexuality in the USA (e.g., Bassett et al. 2005; Hunsberger and Jackson 2005). The present study demonstrated that even though Islam is very strict religion, people who question their religious beliefs and rules may resist religious dogma, and tend to adopt an analytic thinking style. In addition, the moderation analysis demonstrated that gender differences X questioning religion interaction was not statistically significant. Thus, gender differences did not play a moderator role on the relationship between questioning religion and attitudes toward gay men because for both gender questioning their religion showed similar effect. Questioning religious rules is correlated with being tolerant to gay men.

In summary, the present paper was the first attempt to study whether benevolence toward men, hostility toward men, and questioning religion predict heterosexual Muslim people’ attitudes toward gay men. A standard multiple regression analysis showed that benevolence toward men, questioning religion, and gender of the participants significantly predicted attitudes toward gay men. Separate multiple regressions for men and women demonstrated that as well as benevolence toward men and questioning religion, hostility toward men was a significant predictor of attitudes toward gay men for only women. The results, in general, suggest that there may be many beliefs that influence attitudes toward gay men but benevolence toward men and questioning religion are very important ones to focus on. Results of the study may support the argument that system justifying attitudes such as benevolence toward men (Glick and Fiske 2001), and system questioning attitudes such as questioning religion are the basic predictors of prejudice. Prejudice and discrimination against gay men may be reduced by changing both people’s benevolent attitudes toward men and people’s fundamentalist orientation to religion. As suggested by Zuckerman et al. (2013), resistance to religious dogma and adopting an analytic thinking style is positively correlated with education, and so educating people about social differences and sexual orientations is necessary. Learning about the damages of gender roles differentiation, and acceptance of religious dogma may be helpful to individuals to decrease prejudice and discrimination toward outgroups.

The study has also some potential limitations. First of all, only undergraduate students were used in the present study. Future studies should collect data from outside of universities to gather detailed information about how the independent variables predict attitudes toward gay men for non-student samples. In addition, different methods may be used to increase research validity. Finally, as mentioned at the beginning of the paper, Turkey is a secular and democratic Muslim country where there are not strict religious rules. Because of the characteristics of Turkey, it was possible to find students who may question their religion. The results of the present study may not be generalized to other Muslim countries where Islamic rules are strictly followed.

References

Aguero, J. E., Bloch, L., & Byrne, D. (1984). The relationships among sexual beliefs, attitudes, experience, and homophobia. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 95–107. doi:10.1300/J082v10n01_07.

Alauddin, M., & Son Ngheim, H. (2010). Do instructional attributes pose multicollinearity problems? An empirical exploration. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 49, 351–361. doi:10.1016/S0313-5926(10)50034-1.

Bassett, R. L., Hodak, E., Allen, J., Bartos, D., Grastorf, J., Sittig, L., & Strong, J. (2005). Homonegative Christians: Loving the sinner but hating the sin. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 19, 258–269.

Batson, C. D., Floyd, R. B., Meyer, J. M., & Winner, A. L. (1999). “And who is my neighbor?”: Intrinsic religion as a source of universal compassion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 38, 445–457. doi:10.2307/1387605.

Burn, S. M., & Busso, J. (2005). Ambivalent sexism, scriptural literalism, and religiosity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 412–418. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00241.x.

Chonody, J., Woodford, M. R., Smith, S., & Silverschanz, P. (2013). Christian social work students’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Religious teachings, religiosity, and contact. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 32, 211–232. doi:10.1080/15426432.2013.801730.

Deaux, K., & Lewis, L. L. (1984). Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 991–1004. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.991.

Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı [Presidency of Religious Affairs]. (2014). Türkiye’de dini yaşam araştırması [Research on religious life in Turkey]. Ankara: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı.

Duyan, V., & Gelbal, S. (2004). Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gays (LGYT) Scale: Reliability and validity study. Turkish Journal of HIV/AIDS, 7, 106–112.

Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. (1984). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 735–754. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.735.

Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (1995). Ambivalence and stereotypes cause sexual harassment: A theory with implications for organizational change. Journal of Social Issues, 51, 97–115. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01311.x.

Ford, T. E., Bringall, T., VanValey, T. L., & Macaluso, M. J. (2009). The unmaking of prejudice: How Christian beliefs relate to attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48, 146–160. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01434.x.

Fulton, A. S., Gorsuch, R. L., & Maynard, E. A. (1999). Religious orientation, antihomosexual sentiment, and fundamentalism among Christians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 38, 14–22. doi:10.2307/1387580.

Gaunt, R. (2012). “Blessed is he who has not made me a woman”: Ambivalent sexism and Jewish religiosity. Sex Roles, 67, 1323–1334. doi:10.1177/01461672972312009.

Gelbal, S., & Duyan, V. (2006). Attitudes of university students toward lesbians and gay men in Turkey. Sex Roles, 55, 573–579. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9112-1.

Glick, P., & Fiske, T. S. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491.

Glick, P., & Fiske, T. S. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119–135. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The ambivalence toward men inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 519–536. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00379.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109.

Glick, P., Diebold, J., Bailey-Werner, B., & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1323–1334. doi:10.1177/01461672972312009.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., … Wells, R. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713

Habib, S. (2007). Female homosexuality in the Middle East: Histories and representations. New York: Routledge.

Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25, 451–477. doi:10.1080/00224498809551476.

Herek, G. M. (1998). The attitudes toward lesbians and gay men (ATLG) scale. In C. M. Davis, W. H. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 392–394). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Herek, G. M., & Capitanio, J. P. (1996). “Some of my best friends”: Intergroup contact, concealable stigma, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 412–424. doi:10.1177/0146167296224007.

Hojat, M., Shapurian, R., Nayerahmadi, H., Farzaneh, M., Foroughi, D., Parsi, M., & Azizi, M. (1999). Premarital sexual, child rearing, and family attitudes of Iranian men and women in the United States and Iran. Journal of Psychology, 133, 19–31. doi:10.1080/00223989909599719.

Hunsberger, B., & Jackson, L. M. (2005). Religion, meaning, and prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 807–826. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00433.x.

Hunsberger, B., Owusu, V., & Duck, R. (1999). Religion and prejudice in Ghana and Canada: Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, and attitudes toward homosexuals and women. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 9, 181–194. doi:10.1207/s15327582ijpr0903_2.

James, W., Griffiths, B., & Pederson, A. (2011). The “making and unmaking” of prejudice against Australian Muslims and gay men and lesbians: The role of religious development and fundamentalism. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 21, 212–227. doi:10.1080/10508619.2011.581579.

Johnson, M. K., Rowatt, W. C., Barnard-Brak, L. M., Patock-Peckham, J. A., LaBouff, J. P., & Carlisle, R. D. (2011). A mediational analysis of the role of right-wing authoritarianism and religious fundamentalism in the religiosity-prejudice link. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 851–856. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.010.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498.

Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender and Society, 2, 274–290. doi:10.1177/089124388002003004.

Kay, A. C., & Jost, J. T. (2003). Complementary justice: Effects of “poor but happy” and “poor but honest” stereotype exemplars on system justification and implicit activation of the justice motive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 823–837. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.823.

Kite, M. E. (1984). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexuals: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 69–81. doi:10.1300/J082v10n01_05.

Mikolajczak, M., & Pietrzak, J. (2014). Ambivalent sexism and religion: Connected through values. Sex Roles, 70, 387–399. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0379-3.

Milham, J., San Miguel, C. L., & Kellogg, R. (1976). A factor-analytic conceptualization of attitudes toward male and female homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 2, 3–10. doi:10.1300/J082v02n01_01.

O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rule of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality and Quantity, 41, 673–690. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6.

Okutan, N., Büyükşahin Sunal, A., & Sakallı-Uğurlu, N. (2015). Comparing heterosexuals’ and gay men-lesbians’ EVLN responses and the effects of internalized homophobia on gay men-lesbians’ EVLN responses in Turkey. Journal of Homosexuality. In press.

Öner-Özkan, B. (2007). Future time orientation and religion. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 35, 51–62. doi:10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.51.

Öztürk, E., & Kozacıoğlu, G. (1998). Erkek eşcinsellerde (homoseksüellerde) anksiyete ve depresyon düzeylerinin değerlendirilmesi [Evaluating the levels of anxiety and depression in gay men]. IX. Ulusal Psikoloji Kongresi Bilimsel Çalışmaları. Ankara: Türk Psikologlar Derneği.

Öztürk, P., & Kındap, Y. (2011). Lezbiyenlerde içselleştirilmiş homofobi ölçeğinin psikometrik özelliklerinin incelenmesi [Turkish adaptation of the lesbian internalized homophobia scale: A study of validity and reliability]. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları [Turkish Psychological Articles], 14, 24–35.

Özyeğin, G. (2012). Reading the closet through connectivity. Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, 18, 201–222. doi:10.1080/13504630.2012.652845.

Sakallı, N. (2002). The relationship between sexism and attitudes toward homosexuality in a sample of Turkish college students. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 53–63. doi:10.1300/J082v42n03_04.

Sakallı, N., & Uğurlu, O. (2001). Effects of social contact with homosexuals on heterosexual Turkish university students’ attitudes towards homosexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 53–61. doi:10.1300/J082v42n01_03.

Sakallı-Uğurlu, N. (2008). Erkeklere ilişkin çelişik duygular ölçeği’nin Türkçe’ye uyarlanması [Turkish adaptation of ambivalence toward men]. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları [Turkish Psychological Articles], 11, 1–11.

Saraç, L. (2015). Relationships between religiosity level and attitudes toward lesbians and gay men among Turkish university students. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 481–494. doi:10.1080/00918369.2014.983386.

Siraj al-Haqq Kugle, S. (2010). Homosexuality in Islam: Critical reflection on gay, lesbian, and transgender Muslims. Oxford: Oneworld Publication.

Steffens, M. C., & Wagner, C. (2004). Attitudes toward lesbians, gay men, bisexual women, and bisexual men in Germany. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 137–149. doi:10.1080/00224490409552222.

Taşdemir, N., & Sakallı-Uğurlu, N. (2010). The relationships between ambivalent sexism and religiosity among Turkish university students. Sex Roles, 62, 420–426. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9693-6.

Wasti, A. A., Bergman, M. E., Glomb, T. M., & Drasgow, F. (2000). Test of the cross-cultural generalizability of a model of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 766–778. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.766.

Wellman, J. D., & McCoy, S. K. (2014). Walking the straight and narrow: Examining the role of traditional gender norms in sexual prejudice. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15, 181–190. doi:10.1037/a0031943.

Whitley, B. E. (1987). The relationship of sex-role orientation to heterosexuals’ attitudes toward homosexuals. Sex Roles, 17, 103–111. doi:10.1007/BF00287903.

Zuckerman, M., Silberman, J., & Hall, J. A. (2013). The relation between intelligence and religiosity: A meta-analysis and some proposed explanations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17, 325–354. doi:10.1177/1088868313497266.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

English Version of Attitudes Toward Gay Men Scale (ATG)

-

1)-

Sex between two men is just plain wrong.

-

2)-

I think that male homosexuals are disgusting.

-

3)-

Male homosexuality is a natural expression of sexuality in men.

-

4)-

Male homosexuality is a perversion.

-

5)-

Male homosexuality is merely a different kind of lifestyle that should be not be condemned.

Turkish Version of ATG

-

1)-

İki erkek arasındaki seks apaçık yanlıştır.

-

2)-

Erkek eşcinsellerin (geylerin) iğrenç olduğunu düşünüyorum.

-

3)-

Erkek eşcinselliği erkeklerdeki cinselliğin doğal bir dışavurumudur.

-

4)-

Erkek eşcinselliği bir sapkınlıktır.

-

5)-

Erkek eşcinselliği kınanmaması gereken sadece farklı bir yaşam tarzıdır.

English Version of Ambivalence Toward Men Inventory (AMI)

-

1)-

Even if both members of a couple work, the woman ought to be more attentive to taking care of her man at home.

-

2)-

A man who is sexually attracted to a woman typically has no morals about doing whatever it takes to get her in bed.

-

3)-

Men are less likely to fall apart in emergencies than women are.

-

4)-

When men act to “help” women, they are often trying to prove they are better than women.

-

5)-

Every woman needs a male partner who will cherish her.

-

6)-

Men would be lost in this world if women weren’t there to guide them.

-

7)-

A woman will never be truly fulfilled in life if she doesn’t have a committed, long-term relationship with a man.

-

8)-

Men act like babies when they are sick.

-

9)-

Men will always fight to have greater control in society than women.

-

10)-

Men are mainly useful to provide financial security for women.

-

11)-

Even men who claim to be sensitive to women’s rights really want a traditional relationship at home, with the woman performing most of the housekeeping and child care.

-

12)-

Every woman ought to have a man she adores.

-

13)-

Men are more willing to put themselves in danger to protect others.

-

14)-

Men usually try to dominate conversations when talking to women.

-

15)-

Most men pay lip service to equality for women, but can’t handle having a woman as an equal.

-

16)-

Women are incomplete without men.

-

17)-

When it comes down to it, most men are really like children.

-

18)-

Men are more willing to take risks than women.

-

19)-

Most men sexually harass women, even if only in subtle ways, once they are in a position of power over them.

-

20)-

Women ought to take care of their men at home, because men would fall apart if they had to fend for themselves.

Turkish Version of AMI

-

1.

Çiftlerden ikisi de çalısıyor olsa bile, kadın evde erkeğine bakma konusunda daha fazla sorumluluk üstlenmelidir.

-

2.

Bir erkek cinsel açıdan çekici bulduğu kadını yatağa atmak için ne gerekiyorsa yapmak konusunda tipik olarak hiç bir ahlaki değere sahip değildir.

-

3.

Acil durumlarda erkekler kadınlara göre daha düşük olasılıkla kendilerini kaybedeceklerdir.

-

4.

Erkekler kadınlara “yardım ediyor” gibi gözükürken, çoğunlukla kendilerinin kadınlardan daha iyi olduklarını kanıtlamaya çalışırlar.

-

5.

Her kadının kendisini el üstünde tutacak bir erkeğe ihtiyacı vardır.

-

6.

Eğer kendilerine yol gösterecek kadınlar olmasaydı erkekler dünyada kaybolurlardı.

-

7.

Eğer kadının bir erkekle uzun süreli, bağlılık içeren bir ilişkisi yoksa bu hayatta gerçek anlamda kendini tamamlamış sayılmaz.

-

8.

Erkekler hasta olduklarında bebekler gibi davranırlar.

-

9.

Erkekler toplumda kadınlardan daha fazla kontrole sahip olmak için her zaman çabalarlar.

-

10.

Erkekler temelde kadınlara maddi güvence sağlamak açısından yararlıdırlar.

-

11.

Kadın haklarına duyarlı olduğunu iddia eden erkekler bile aslında ev işlerinin ve çocuk bakımının çoğunu kadının üstlendiği geleneksel bir ilişki isterler.

-

12.

Her kadının hayran olduğu bir erkeği olmalıdır.

-

13.

Erkekler başkalarını korumak için kendilerini tehlikeye atmaya daha gönüllüdürler.

-

14.

Erkekler kadınlarla konuşurken genellikle baskın olmaya çalışırlar.

-

15.

Çoğu erkek kadınlar için eşitliği sözde savunur ama bir kadını kendilerine eşit olarak görmeyi kaldıramazlar.

-

16.

Kadınlar erkeksiz eksiktirler.

-

17.

Özüne bakıldığında, çoğu erkek gerçekten çocuk gibidir.

-

18.

Erkekler kadınlara oranla risk almaya daha gönüllüdürler.

-

19.

Çoğu erkek, kadınlar üzerinde güç sahibi oldukları bir pozisyonda bulundukları anda, üstü kapalı yolla bile olsa kadınları cinsel açıdan taciz ederler.

-

20.

Kadınlar evde erkeklerine bakmalıdırlar çünkü eğer erkekler kendi kendilerine bakmak zorunda kalırlarsa bunu beceremezler.

English Version of Questioning Religion Scale

-

1)-

I cannot accept my religion the way it is presented without questioning.

-

2)-

I question the rules of my religion and practice the religion according to my own understanding.

-

3)-

As I grow and change, my religion also grows and changes with me.

-

4)-

No system of religious belief is valid for everyone or can provide absolute truth.

-

5)-

As a believer, I think religious rules can be changed and adapted to current times.

-

6)-

I think that being skeptical about my religion helps me to expand my horizons.

Turkish Version of Questioning Religion Scale

-

1)-

Dini sorgulamadan sunulduğu gibi kabul edemem.

-

2)-

Dinin kurallarını sorgular ve kendi anladıklarıma göre uygularım.

-

3)-

Ben değiştikçe dini inançlarım da benimle birlikte değişip gelişir.

-

4)-

Hiçbir dini inanç sistemi herkes için geçerli değildir ve gerçek doğruyu sağlayamaz.

-

5)-

İnançlı bir kişi olarak dini kuralların günümüze göre uyarlanması taraftarıyım.

-

6)-

Dine şüpheci yaklaşmanın beni yeni açılımlara yönlendirdiğini düşünüyorum.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sakallı-Uğurlu, N., Uğurlu, O. Predicting Attitudes Toward Gay Men with Ambivalence Toward Men, Questioning Religion, and Gender Differences. Sex Roles 74, 195–205 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0571-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0571-0