Abstract

Women with spinal cord injury (SCI) often experience sexual dysfunction, however, it is underassessed and undertreated in clinical settings. This purpose of this scoping review was to characterize, synthesize and evaluate the current evidence on sexuality, sexual function, and sexual wellness among women with SCI in order to inform care practices, highlight gaps in knowledge, and guide the development of interventions to improve sexual health and well-being. The scoping review methodological framework and the PRISMA extension were used to guide the search strategy, study selection, data collection, and reporting. Searched articles related to SCI and sexuality and sexual health from 1980 to 2022. The study team synthesized the information extracted from eligible studies both descriptively and thematically. Sixty-five articles met inclusion criteria. The majority of research was conducted in high income, Western countries, and explored sexual dysfunction for women with SCI. Few studies described the development and dissemination of interventions aimed at improving sexual function or quality of life, and 91% of the studies were observational. In this 40-year period, the field of research has established a solid foundation connecting SCI with sexual dysfunction. It is time to progress the field into developing and disseminating behavioral interventions to complement devices and drugs. These interventions may seek not only to improve sexual function, but also increase sexual self-efficacy and well-being, improve relationship satisfaction, increase self-advocacy, and provide access to educational resources and therapeutic aids that can improve sexual satisfaction and sexual quality of life for women with SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a life-altering event and is associated with deficits in both motor, sensory, and autonomic abilities, often resulting in sexual dysfunction. This can include physical responses like genital arousal, lubrication, and orgasm, as well as psychosocial impacts on sexual desire, perceived attractiveness, self-esteem, and relationship status. As the majority of SCIs occur in younger males who are typically in their reproductive years [1], there is paucity of literature that examines sexual health and functioning in women with SCI. However, sexual health and function, healthy intimate relationships, and sexuality are important aspects of women’s wellness and quality of life while living with SCI. In the most recent North American Spinal Cord Injury Consortium Report from the 2020 SCI Panel and Consumer Survey, the majority of survey respondents agreed that restoring sexual function is important to them [2]. Despite the importance of sexual health, there is an unmet need for sexual health support and resources in clinical and research settings, particularly for women with SCI.

The prevalence and experience of sexual dysfunction in women with SCI is arguably unique from men due to anatomical, endocrinological and physiological differences, but also due to differing social roles, life experiences, societal influences and stigma. Despite the acknowledged importance of sexual rehabilitation, sexual well-being is underassessed and poorly treated in clinical settings. To map the field of research, identify gaps, and to better support clinicians as they address this important topic in women with SCI, we conducted a scoping review of literature on sexuality for women with SCI. Thus, the goal of this review was to characterize, synthesize and evaluate the current evidence on sexuality, sexual function, and sexual wellness among women with SCI in order to inform care practices, highlight gaps in knowledge, and guide the development of interventions to improve sexual health and well-being in this patient population.

Methods

We used the scoping review methodological framework which allows for a diversity of literature and study designs to be included, enabling a broader conceptual range of inquiry [3, 4]. We used the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Scr) [5] to guide the search strategy, study selection, data collection, and reporting in this review.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility assessment of each abstract was performed using a standardized form and single reviewer. Articles were included in the review if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) focused on women with SCI exclusively or included them as part of a subsample; (2) a minimum of at least five or more women with SCI were included in the sample; (3) conducted in adult (18+) human subjects; (4) data collection used a quantitative study design (observational or interventions) or mixed-methods (qualitative and quantitative); and (5) addressed an aspect of sexual function or sexual health. Qualitative studies, including case reports, case series, reviews, editorials, and other types of articles, were excluded.

In this review, SCI was broadly defined to include traumatic and non-traumatic causes occurring from external forces or disease processes. Conditions such as spinal compression, vertebral fracture, cervical myelopathy, cervical spondylosis, or demyelinating diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis were excluded.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Data Sources: The databases used in this search were PUBMED (1966 – Present), EMBASE (1947 – Present), SCOPUS (1960 – Present), and Web of Science (1900 – Present). The final search was performed on July 26, 2022. In addition, the research team manually searched reference lists of articles that underwent full text review. We used the following relatively broad search terms to search all databases: spinal cord injuries; females; women; sex; gender; humans; adults. Full search syntax for each database is given in Table 1.

Data Elements

Data elements were partially based on reporting guidelines for observational studies (STROBE) [6] and interventional trials (CONSORT) [7] to capture key aspects of study design, sample characteristics, methodology, and analysis. Data elements also captured information about SCI, such as injury level and severity and time since injury to characterize the samples. We were also interested in the extent to which women with SCI were compared to men with SCI, women without SCI, and other non-SCI samples.

Data Extraction

Once eligibility was determined, each article was assigned to pairs of reviewers to review each article independently. REDCap was used for data collection; Excel was used to identify and resolve discrepancies between reviews.

Synthesis of Results

To map the broad field of literature on sexuality and SCI and to provide a more in-depth perspective [3, 4], we synthesized the information extracted from eligible studies both descriptively and thematically. The lead author (MN) developed, defined, and assigned the themes after a first review of articles; the second author (MB) reviewed the themes and assignments. More than one theme could be applied to an article, and themes were refined through this iterative process between authors. We also examined the articles by study design, population, world region (World Health Organization [WHO] world regions) and income level (World Bank income classification), publication dates, and outcome measures.

Results

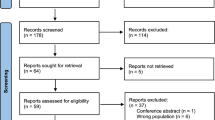

From the search, 362 records were identified in the electronic databases and another 6 records were identified through a manual reference search. After duplicates were removed, 239 citations were reviewed based on their title and abstract. Of these, 174 were excluded with a final set of 65 studies included in the review (see Fig. 1).

Characteristics of Included Studies

The review spanned 40 years of research, starting in 1982, with only two articles published in that decade. In the 1990s there was an increase in research on sexuality and women with SCI, with 17 articles published in that decade. There continued to be a gradual increase over time with 19 articles published from 2000 to 2010, and 23 from 2010 to 2020. Studies were conducted in all WHO world regions, with the majority conducted in the Region of Americas (46.2%) and the European Region (30.8%), and in World Bank classified high income countries (73.8%).

More than half of all reviewed studies used a cross-sectional design (57%), followed by case-control studies (29.2%), randomized control trials (9.2%), and cohort studies (9.2%). Sample sizes ranged from 5 to over 1,000 participants. The majority were conducted in samples of only women with SCI (46.2%), followed by studies comparing outcomes in women with SCI to women without SCI (29.2%), and 24.6% of studies examined outcomes of both women with SCI and men with SCI. Only two articles included participants with other physical disabilities, like multiple sclerosis and post-polio syndrome [8, 9], and one study recruited married couples where at least one partner had SCI [10]. More than half of the articles involved community-based participants (59.1%), 27.7% recruited participants from inpatient SCI rehabilitation centers, and 15.4% recruited from national registries, the SCI Model Systems, or used large cohort datasets.

Reporting of demographic data was limited in the articles. Eighteen (27.7%) studies only reported age and no other demographic characteristics (e.g., employment, income, education, marital status or living arrangement, urbanity, etc.), while seven (10.8%) studies reported no descriptive statistics at all. Only eight studies (12.3%) reported race and/or ethnicity characteristics of their sample; seven of these were from studies conducted in the US, and one was conducted in Malaysia. While only six (9.2%) studies reported on sexual orientation, and all of these studies were conducted in the US or Australia. Reporting of disability characteristics was slightly better, with 33.8% of studies reporting injury level through ASIA scores (n = 19) or Frankel scores (n = 3). However, 80% of studies (n = 52) provided some descriptive data on other disability characteristics, such as duration of time since injury, completeness of SCI, and/or etiology of injury.

The review identified six intervention studies. Two studies conducted drug trials of sildenafil [11, 12], one conducted a device trial to improve sexual function for women with SCI [8], one examined different modalities of self-stimulation on arousal response [13], and two studies tested health education/counseling interventions [10, 14]. Characteristics of studies, such as the distribution of study design, WHO region and World Bank income classifications is summarized in Table 2.

Study outcomes and measurement tools spanned many domains including sexual function (the body’s ability to get into positions for sexual activity and experience arousal and/or orgasm), sexual satisfaction (one’s satisfaction with their sexual life), quality of life and life satisfaction, depression and anxiety, sexual distress (including frustration, anxiety, and worry regarding one’s sexual activity [15, 16]), body image, and physiological measures (i.e., blood pressure, heart rate, body composition, vaginal pulse amplitude). When standardized measures were used to assess sexual function, most used the Female Sexual Function Inventory (FSFI) [17] (20%), or the Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DFSI) [18] (6.2%). The FSFI is a 19-item self-report measure to quantify sexual dysfunction within the domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. It has been translated and validated into more than 20 languages [17, 19, 20]. The DFSI is a 254-item self-report measure to quantify sexual function across ten domains (e.g., sexual drive, attitudes, psychological symptoms, body image, and sexual satisfaction). While both of these measurement tools are validated and demonstrate reliability in the general population, neither the FSFI or DFSI are disability specific measures of sexual function. Additionally, more than a third of studies utilized outcome measures that were developed by their research team, which primarily evaluated aspects of sexual function. Other outcome measures included sexual attitudes, interests, expression, and needs; marital satisfaction; quality of relationship; intimacy; and independence. Outcome measures are described in Table 3.

Major Theme Areas

Results of the studies were thematically analyzed by the authors. Six major themes and 18 sub-themes were identified across the 65 studies and are summarized in Table 4.

Over the past 40 years, the field of research on sexuality and women with SCI has predominantly focused on exploring Physical Function related to sexual activity (engaging in sexual contact or activities of a sexual nature, alone or with partners). The majority of studies assessed sexual dysfunction (n = 46), impaired arousal response or sexual desire (n = 35), and other physiological factors affecting function (n = 3).

Studies were also characterized by topics that explored women’s experiences of Sexuality After Injury (n = 51). This theme included studies that reported frequency and quality of sexual activity (n = 24), as well as sexual adjustment (n = 13) (“post-injury sexual views of the self” [21]). Few articles explored important topics related to sexuality after an acquired SCI, such as the use of therapeutic aids and adaptations for sex (n = 2), experiences of disability stigma (n = 2), women’s experiences in rehabilitation programs (n = 5), or barriers to sexual health (n = 3). Studies reported that women with SCI desired information about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) after injury, but were often not provided SRH information in rehabilitation settings or from their clinicians [22,23,24]. Women with SCI felt that social issues beyond physical factors negatively affected their sexual function and activity, such as environmental barriers, stigma, and lack of support and resources were noted as more detrimental [25]. Furthermore, studies reported that the use of therapeutic aids improved satisfaction with sex [9, 26].

Almost half of the studies examined Sexual Satisfaction and Sexual Quality of Life (n = 31), which included satisfaction with sexual activity, arousal or orgasm, and quality of sexual life. Many of these studies reported decreased sexual satisfaction and greater impairment related to arousal or orgasm when compared with individuals with no SCI or compared to sexual satisfaction prior to injury [27,28,29,30,31,32]. In several studies, aging was identified as contributing to self-reports of poorer sexual function and lower sexual satisfaction [27, 33, 34].

The theme of Intrapersonal and Emotional Response related to sexuality was also frequently addressed (n = 23), with almost half of these studies assessing depression, anxiety, and distress related to sexuality and sexual activity for women with SCI (n = 11). These studies also examined women’s perceptions and feelings about body image (n = 8), and sexual confidence or self-esteem (n = 4). Results demonstrated that sexual function and satisfaction were related to affect [9, 25], and that many women experienced negative changes in body image, greater distress, and lower sexual self-esteem after SCI [26, 28, 35, 36]. However, resilience of psychosocial constructs, such as self-esteem, personal control, and optimism, may be predictive of better sexual adjustment outcomes [21].

Sexual Information and Education (n = 21) was characterized by studies that measured women’s knowledge around sexual health and sexuality, or identified barriers and gaps when seeking sexual health information. Participants in these studies described the environmental and attitudinal barriers to accessing sexual health information and care (n = 15), and the types of SRH education they would like to see available (n = 4). These studies emphasized a need for relevant and timely SRH counseling, education, and support, and highlighted the overwhelming lack of SRH resources for women with SCI globally [14, 22]– [25, 32, 36]– [38].

Relationships and Intimacy (n = 14) included studies that examined partner/marital satisfaction, perceptions of partner’s satisfaction with sex life, relationship quality, and satisfaction with intimate relationships. The findings from these studies were mixed; while some results showed increased satisfaction with intimacy and with partners in some couples after SCI [35], other studies showed greater dissatisfaction with intimate life post-injury [38,39,40,41]. Results suggested that greater dissatisfaction may be related to age, duration of time with injury, sociocultural expectations, and stigma.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to characterize, synthesize and evaluate the current evidence on sexuality, sexual function, and sexual wellness among women with SCI to inform care practices, highlight knowledge gaps, and inform the development of interventions to improve sexual health and well-being. Although the scientific literature began exploring sexual health in women with SCI in the 1980s, the progression of research has been slow to advance to higher stages of research, such as linking health behaviors to outcomes or developing and disseminating interventions.

Additionally, the types of studies conducted were concentrated; 95% were observational, primarily cross-sectional and case-control. While these study designs are appropriate for describing attributes of a condition or population, future research on sexual well-being and SCI will need to include more rigorous study designs, such as randomized control trials, to advance the science and in particular, the development and testing of interventions. The few intervention-based studies in this review primarily focused on drug or stimulation device trials to improve arousal and orgasm, with only two interventions targeting sexual education or counseling programs [10, 14]. Expanding study outcomes beyond physical and biological response to sexual function, such as aiming to improve sexual self-efficacy, sexual well-being, or knowledge of adaptations for satisfying sex, will be critical for continued growth in the field. For example, women with physical disabilities have expressed a desire and need for accessible sexual health interventions and educational materials relevant to sexuality and disability [42].

Because the majority of the studies focused on sexual dysfunction, most outcome measures evaluated sexual function and arousal, with far fewer evaluating important factors associated with sexual well-being, such as satisfaction, affect, and sexual quality of life [42]. This review also highlights that more than a third of studies used outcome measures that the research team developed for their studies rather than using established measures demonstrated to be psychometrically sound, clinically relevant, and validated for use in populations with SCI, such as the International SCI Basic Data Sets for Female Sexual and Reproductive Function [43]. Because there were many instances of researchers developing their own measures for use in SCI populations, future studies may consider exploring if the existing validated measurement tools do not adequately capture relevant or comprehensive aspects of sexual health, or if these measures are not suitable for use in populations with SCI. Future studies should use, as much as possible, measures validated for use in populations with SCI that accurately reflect the unique experience of sexuality at the intersection of disability [42].

Our assessment of the distribution of SCI and sexuality research worldwide, and with regard to economic development, indicate an obvious wealth gap in the geographical location of where these studies were conducted. Close to 75% of the articles published were from high income countries, primarily the Americas (46.2%) and European Region (30.8%). This results in an overemphasis on predominantly white and western perspectives on sexuality. Studies conducted in lower to middle income countries (as defined by the World Bank Income Classification) will help to identify sexual concerns related to differing societal roles and cultures beyond Western cultures. Moreover, there was limited information provided on demographic or descriptive characteristics of the study samples, such as race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, employment status, relationship status, education, or income. Even in studies that did provide descriptive data, no meaningful analyses or results were presented related to demographics other than injury characteristics. As researchers and clinicians strive to understand intersectionality, or how the layering of identity and social categorizations impacts health outcomes and experiences, it is important for studies to collect and describe their populations in greater detail and examine how these intersections contribute to discrimination and health inequity.

We assessed the primary themes in each study to gain a clearer understanding of the focus of research on sexuality and SCI. While physical functioning was the most prevalent theme investigated by the articles in this review, many articles also explored psychosocial themes, such as affect, sexual adjustment, and disability stigma. These articles elucidated issues beyond function to describe how societal and intrapersonal factors impact the experience of sexuality and satisfaction with sex. Many studies explored adjusting to sexuality after acquiring an SCI, which included comparing how sexual activity or frequency of sexual activity changes; how women utilize therapeutic aids and adaptive equipment or positioning; experiences with sexual health counseling and educational resources in rehabilitation centers; environmental and attitudinal barriers to sexuality and sexual health; and stigma that women with disabilities face when dating or entering intimate relationships. This demonstrates that while sexual function is a very important part of sexuality, other factors, such as accessible environments, societal stigma, access to patient-centered healthcare, intra and interpersonal factors, and sexual self-efficacy contribute to their perceptions of sexual well-being [42].

Mapping the literature on women’s sexual health and SCI allows us to clearly see the gaps and lack of evolution of this field of research. In their initial stages, fields of research often begin by gathering data on a condition and describing health outcomes for a population. From here, measurement tools are developed and validated. Studies then evolve to explore factors that influence behavior, theories of behavior emerge, and theories and frameworks are tested. The field of research finally progresses to developing interventions, disseminating health promotion programs, and translating research into practice [44]. While the studies in this review span four decades, they have not adequately evolved to reach these higher stages of research (See Fig. 2). The field of sexuality for women with SCI remains largely in this initial phase of documenting physical function and describing related health outcomes, with only six studies in the past 25 years describing any intervention attempts. Sexual dysfunction has been well demonstrated, but women still have few resources, educational tools, or programs to support healthy sexuality.

While the literature in this review clearly identifies a critical need for disability-relevant, holistic sexual wellness support as sexuality and sexual wellness change after injury and across the lifespan, few accessible resources exist. These studies have contributed to a strong foundational knowledge on sexual dysfunction for women with SCI. In order to progress not only the body of work in this area, but also to meet the sexual health needs of women with SCI, future research must develop and disseminate educational resources and health promotion programs and translate research into practice. Additionally, future studies should aim to recruit more diverse samples that reflect the demographics of women impacted by SCI. This will allow researchers to explore health inequity related to intersectionality. For example, this can include expanding the regions of the world where sexual health research for women with SCI is being conducted, and exploring how sexuality and disability intersect for individuals in the LGBTQIA + community or those of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Implications for Future Research

The literature included in this scoping review establishes a solid foundation connecting SCI with sexual dysfunction among women, and highlights the need to broaden the scope of the research being conducted to develop and disseminate behavioral interventions to complement devices and drugs. This can begin with engaging communities of women with SCI in the development and implementation of these interventions, and to ensure programs are accessible and relevant to their unique needs. The extant literature suggests that interventions for women with SCI have the potential to improve sexual function, increase sexual self-efficacy and well-being, improve relationship satisfaction, increase self-advocacy, and provide access to educational resources and therapeutic aids that can improve sexual satisfaction and sexual quality of life.

Limitations

This scoping review is intended as a synthesis of research on sexual health and wellness in women with SCI. While our search terms were extremely broad, this does not guarantee that all relevant studies were included in the review. With respect to generalizability of the findings, the vast majority of studies to date have been conducted in the Americas and Europe, and thus mostly high-income countries. While this is representative of the literature, it is also a caveat for generalizing these findings to women who live in lower- and middle-income countries in other regions of the world. Gaps in interventions and education found in high income countries suggests that unmet needs are amplified in regions where resources are scarce and other needs are likely to be prioritized. Nevertheless, these findings are a call to the field to continue work to reach women with SCI across the world to understand their context-specific needs and concerns. Moreover, given most of the literature to date represents a Western experience of sexual health and wellness, understanding the experience and needs of women living in non-Western cultures is an important area for development.

Conclusion

This review synthesizes the current literature on sexual health and wellness in women with SCI. In doing so, it highlights what topics have and have not been studied pertaining to sexual health in women with SCI and identifies areas where future research is needed. It is the largest and most up to date review on the topic and provides support for advancing the field towards development and dissemination of interventions. The review shines a much needed light on an important but largely neglected area of research that is important to women’s overall quality of life, and reveals that after 40 years of research, the field has done little to address the sexual health and well-being of women with SCI with few studies focusing efforts to develop intervention to enhance sexual health. We recommend clinicians and researchers work together to continue to make advancements in addressing the sexual health needs of women with SCI because a comprehensive and integrated approach to advancing the topic of sexual dysfunction is necessary.

References

NASCIC Report of SCI 2020 Panel and Consumer Survey, North American Spinal Cord Injury Consortium:, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2022. [Online]. Available: (2019). https://nasciconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Final-report-SCI-2020-panel-and-survey-results-NASCIC.pdf

Facts and Figures at a Glance:, University of Alabama at Birmingham, National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, Birmingham, AL, 2020. Accessed: Jun. 20, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts%20and%20Figures%202020.pdf

Arksey, H., O’Malley, L.: Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Social Res. Methodology: Theory Pract., 8, 1, (2005)

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., O’Brien, K.: Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5, 69 (2010)

Tricco, A., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Straus, S.: PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Res. Report. Methods. (2018). https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

von Elm, E., Altman, D., Egger, M., Pocock, S., Gøtzsche, P., Vandenbroucke, J.: The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61(4), 344–349 (2008)

Moher, D., et al.: Explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63(8), e1–e37 (2010)

Alexander, M., Bashir, K., Alexander, C., Marson, L., Rosen, R.: Randomized Trial of Clitoral Vacuum Suction Versus Vibratory Stimulation in Neurogenic Female Orgasmic Dysfunction. Archives Phys. Med. 99(2), 299–305 (2018)

Smith, A., Molton, I., McMullen, K., Jensen, M.: Sexual function, satisfaction, and Use of Aids for sexual activity in Middle-aged adults with long-term physical disability. Top. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 21(3), 227–232 (2015)

Kim, M., Kim, S., Choi, Y.: The effect of sexual education program on spinal cord injured couples on disability acceptance, self-esteem, and marital relationship enhancement. Biomed. Res. 29(20), 3737–3741 (2018)

Alexander, M., Rosen, R., Steinberg, S., Symonds, T., Haughie, S., Hultling, C.: Sildenafil in women with sexual arousal disorder following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 49(2), 273–279 (2011)

Sipski, M., Rosen, R., Alexander, C., Hamer, R.: Sildenafil effects on sexual and cardiovascular responses in women with spinal cord injury. Urology. 55(6), 812–815 (2000)

Komisaruk, B., Gerdes, C., Whipple, B.: Complete’ spinal cord injury does not block perceptual responses to genital self-stimulation in women. Arch. Neurol. 54(12), 1513–1520 (1997)

Rezaei-Fard, M., Lotfi, R., Rahimzadeh, M., Merghati-Khoei, E.: Effectiveness of sexual counseling using PLISSIT model to promote sexual function of women with spinal cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Article. Sex. Disabil. 37(4), 511–519 (2019)

Derogatis, L., Rosen, R., Leiblum, S., Burnett, A., Heiman, J.: The female sexual distress scale (FSDS): Initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J. Sex. Marital Ther. 28, 317–330 (2002)

Lief, H.: Satisfaction and distress: Disjunctions in the components of sexual response. J. Sex. Marital Therapy. 27, 169–170 (2001)

Rosen, R., et al.: The female sexual function index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the Assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 26(2), 191–208 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278597

Derogatis, L., Mellisaratos, N.: The DSFI: A multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. J. Sex Marital Ther. 5, 244–281 (1979)

Sand, M., Rosen, R., Meston, C., Brotto, L.: The female sexual function index (FSFI): A potential ‘gold standard’ measure for assessing therapeutically-Induced change in female sexual function. Fertil. Steril. 92(S129) (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.1173

Sánchez-Sánchez, B., Navarro-Brazález, B., Arranz-Martín, B., Sánchez-Méndez, O., de la Rosa-Díaz, I., Torres-Lacomba, M.: The female sexual function index: Transculturally Adaptation and Psychometric Validation in Spanish Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(3) (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030994

Mona, L., Krause, J., Norris, F., Cameron, R., Kalichman, S., Lesondak, L.: Sexual expression following spinal cord injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 15(2), 121–131 (2000)

Amjadi, M., Simbar, M., Hoseini, S., Zayeri, F.: Evaluation of sexual reproductive health needs of women with spinal cord injury in Tehran, Iran. Sex. Disabil. 40(1), 91–104 (2022)

Celik, E., Akman, Y., Kose, P., Arioglu, P., Karatas, M., Erhan, B.: Sexual problems of women with spinal cord injury in Turkey. Spinal Cord. 52(4), 313–315 (2014)

Ferreiro-Velasco, M., Barca-Buyo, A., de la Barrera, S., Montoto-Marques, A., Vazquez, X., Rodriguez-Sotillo, A.: Sexual issues in a sample of women with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 43(1), 51–55 (2005)

Lubbers, N., Nuri, R., van Brakel, W., Cornielje, H.: Sexual health of women with spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Asia Pac. Disabil. Rehabilitation J. 23(3), 6–23 (2012)

Kreuter, M., Taft, C., Siosteen, A., Biering-Sorensen, F.: Women’s sexual functioning and sex life after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 49(1), 154–160 (2011)

Black, K., Sipski, M., Strauss, S.: Sexual satisfaction and sexual drive in spinal cord injured women. J. Spinal Cord Med. 21(3), 240–244 (1998)

Fisher, T., Laud, P., Byfield, M., Brown, T., Hayat, M., Fielder, I.: Sexual health after spinal cord injury: A longitudinal study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 83(8), 1043–1051 (2002)

Kettl, P., et al.: Female sexuality after spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 9(4), 287–295 (1991)

Jörgensen, S., Hedgren, L., Sundelin, A., Lexell, J.: Global and domain-specific life satisfaction among older adults with long-term spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 42(2), 322–330 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2019.1610618

Sale, P., Mazzarella, F., Pagliacci, M., Agosti, M., Felzani, G., Franceschini, M.: Predictors of changes in sentimental and sexual life after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93(11), 1944–1949 (2012)

Sipski, M., Alexander, C.: Sexual activities, response and satisfaction in women pre- and post-spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 74(10), 1025–1029 (1993)

Tzanos, I., Tzitzika, M., Nianiarou, M., Konstantinidis, C.: Sexual dysfunction in women with spinal cord injury living in Greece. Spinal Cord Ser. Case. 7(1), 41 (2021)

Valtonen, K., Karisson, A., Siosteen, A., Dahlof, L., Viikari-Juntura, E.: Satisfaction with sexual life among persons with traumatic spinal cord injury and meningomyeloce. Disabil. Rehabil. 28(16), 965–976 (2006)

Kreuter, M., Siosteen, A., Biering-Sorensen, F.: Sexuality and sexual life in women with spinal cord injury: A controlled study. J. Rehabil. Med. 40(1), 61–69 (2008)

Charlifue, S., Gerhart, K., Menter, R., Whiteneck, G., Scott Manley, M.: Sexual issues of women with spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 30(3), 192–199 (1992)

Maasoumi, R., Zarei, F., Merghati-Khoei, E., Lawson, T., Emami-Razavi, S.: Development of a sexual needs Rehabilitation Framework in Women Post-spinal Cord Injury: A study from Iran. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 99(3), 548–554 (2018)

Singh, R., Sharma, S.: Sexuality and women with spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 23(1), 21–33 (2005)

Salmani, Z., Khoei, E., Aghajani, N., Bayat, A.: Sexual matters of couples with spinal cord injury attending a sexual health clinic in Tehran, Iran. Archives Neurosci., 6, 2, (2019)

White, M., Rintala, D., Hart, K., Fuhrer, M.: Sexual activities, concern, and interests of women with spinal cord injury living in the community. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 72(6), 372–378 (1993)

White, M., Rintala, D., Hart, K., Fuhrer, M.: A comparison of the sexual concerns of men and women with spinal cord injuries. Rehabilitation Nurs. Res. 3(2), 55–61 (1994)

Nery-Hurwit, M., Kalpakjian, C., Kreschmer, J., Quint, E., Ernst, S.: Development of a conceptual Framework of sexual well-being for women with physical disability. Women’s Health Issues. 32(4), 376–387 (2022)

Alexander, M., Biering-Sorensen, F., Elliott, S., Krueter, M., Sonksen, J.: International spinal cord injury female sexual and reproductive function basic data set. Spinal Cord. 49, 787–790 (2011)

Sallis, J., Owen, N., Fotheringham, M.: Behavioral epidemiology: A systematic framework to classify phases of research on health promotion and disease prevention. Ann. Behav. Med. 22(4), 294–298 (2000)

Lombardi, G., Mondaini, N., Macchiarella, A., Popolo, G.D.: Female sexual dysfunction and hormonal status in spinal cord injured (SCI) patients. J. Androl. 28(5), 722–726 (2007)

Whipple, B., Gerdes, C., Komisaruk, B.: Sexual response to self-stimulation in women with complete spinal cord injury. J. Sex Res. 33(3), 231–240 (1996)

Whipple, B., Richards, E., Tepper, M., Komisaruk, B.: Sexual response in women with complete spinal cord injury. Sex. Disabil. 14(3), 191–201 (1996)

Civici, N., Yilmaz, B., Guzelkucuk, U., Goktepe, A., Tan, A.: Sexual function in female patients with spinal cord Injury. Turkish J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation. 60(60), S1–S10 (2014)

Anderson, K., Borisoff, J., Johnson, R., Steins, S., Elliott, S.: Spinal cord injury influences psychogenic as well as physical components of female sexual ability. Spinal Cord. 45(5), 349–359 (2007)

Othman, A., Engkasan, J.: Sexual dysfunction following spinal cord injury: The experiences of Malaysian women. Sex. Disabil. 29(4), 329–337 (2011)

Sramkova, T., et al.: Women’s sex life after spinal cord Injury. Sex. Med. 5(4), 255–259 (2017)

Westgren, N., Hultling, C., Levi, R., Seiger, A., Westgren, M.: Sexuality in women with traumatic spinal cord injury. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 76(10), 977–983 (1997)

Sharma, S., Singh, R., Dogra, R., Gupta, S.: Assessment of sexual functions after spinal cord injury in Indian patients. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 29(1), 17–25 (2006)

Kreuter, M., Sullivan, M., Siösteen, A.: Sexual adjustment after spinal cord injury-comparison of partner experiences in pre- and postinjury relationships. Paraplegia. 32, 759–770 (1996)

Komisaruk, B., et al.: Brain activation during vaginocervical self-stimulation and orgasm in women with complete spinal cord injury: fMRI evidence of mediation by the Vagus nerves. Brain Res. 1024(1–2), 77–88 (2004)

Sipski, M., Alexander, C., Rosen, R.: Orgasm in women with spinal cord injuries: A laboratory-based assessment. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 76(12), 1097–1102 (1995)

Tas, I., Yagiz On, A., Altay, B., Özdedeli, K.: Sexual dysfunctions and their associations with neurological level in spinal cord injured patients. Turkiye Fiziksel Tip ve Rehabilitasyon Dergisi. 52(4), 143–149 (2006)

D’Andrea, S., et al.: Metabolic syndrome is the key determinant of impaired vaginal lubrication in women with chronic spinal cord injury. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 43(7), 1001–1007 (2020)

Merghati-Khoei, E., Aghajani, N., Sheikhan, F.: Development, validity and reliability of sexual health measures for spinal cord injured patients in Iran. Sex. Disabil. 39(1), 55–65 (2013)

Harrison, J., Glass, C., Owens, R., Soni, B.: Factors associated with sexual functioning in women following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 33(12), 687–692 (1995)

Moreno-Lozano, M., Durán-Ortiz, S., Pérez-Zavala, R., Quinzaños-Fresnedo, J.: Sociodemographic factors associated with sexual dysfunction in Mexican women with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 54(9), 746–749 (2016)

Hajiaghababaei, M., et al.: Female sexual dysfunction in patients with spinal cord injury: A study from Iran. Spinal Cord. 52(8), 646–649 (2014)

Leyson, J.: Electromyographic (EMG) urodynamic anal probe as a diagnostic tool in the management of sexual dysfunctions in female spinal cord injured patients. J. Am. Paraplegia Soc. 6(4), 79–80 (1983)

Matzaroglou, C., Assimakopoulos, K., Panagiotopoulos, E., Kasimatis, G., Dimakopoulos, P., Lambris, E.: Sexual function in females with severe cervical spinal cord injuries: A controlled study with the female sexual function index. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 28(4), 375–377 (2005)

Merghati-Khoei, E., et al.: Psychometric properties of the sexual Adjustment Questionnaire (SAQ) in the Iranian population with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 53, 807–810 (2015)

New, P., Currie, K.: Development of a comprehensive survey of sexuality issues including a self-report version of the International spinal cord Injury sexual function basic data sets. Spinal Cord. 54(8), 584–591 (2016)

Merghati-Khoei, E., et al.: Measuring sexual performance: Development and Psychometric properties of the sexual performance questionnaire in Iranian people with spinal cord Injury. Sex. Disabil. 39(1), 55–65 (2021)

Sipski, M., Rosen, R., Alexander, C.: Physiological parameters associated with the performance of a distracting task and genital self-stimulation in women with complete spinal cord injuries. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77(5), 419–424 (1996)

Sipski, M., Alexander, C., Rosen, R.: Physiologic parameters associated with sexual arousal in women with incomplete spinal cord injuries. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 78(3), 305–313 (1997)

Sipski, M., Alexander, C., Rosen, R.: Sexual response in women with spinal cord injuries: Implications for our understanding of the able bodied. J. Sex Marital Ther. 25(1), 11–22 (1999)

Sipski, M., Rosen, R., Alexander, C., Hamer, R.: A controlled trial of positive feedback to increase sexual arousal in women with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation. 15(2), 145–153 (2000)

Sipski, M., Alexander, C., Rosen, R.: Sexual arousal and orgasm in women: Effects of spinal cord injury. Ann. Neurol. 49(1), 35–44 (2001)

Sipski, M., Rosen, R., Alexander, C., Gomez-Marin, O.: Sexual responsiveness in women with spinal cord injuries: Differential effects of anxiety-eliciting stimulation. Arch. Sex Behav. 33(3), 295–302 (2004)

Sipski, M., Alexander, C., Gomez-Marin, O., Grossbard, M., Rosen, R.: Effects of vibratory stimulation on sexual response in women with spinal cord injury. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 42(5), 609–616 (2005)

Lysberg, K., Severinsson, E.: Spinal cord injured women’s views of sexuality: A Norwegian survey. Rehabilitation Nurs. 28(1), 23–26 (2003)

Zwerner, J.: Yes we have troubles but nobody’s listening: Sexual issues of women with spinal cord injury. Sexuality Dsiability. 5(3), 158–171 (1982)

New, P., Seddon, M., Redpath, C., Currie, K., Warren, N.: Recommendations for spinal rehabilitation professionals regarding sexual education needs and preferences of people with spinal cord dysfunction: A mixed-methods study. Spinal Cord. 54(12), 1203–1209 (2016)

Rezaei, M., et al.: Frequently asked questions of individuals with spinal cord injuries: Results of a web-based consultation service in Iran. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases, 4, 50, (2018)

Bassett, R., Ginis, K., Buchholz, A.: A pilot study examining correlates of body image among women living with SCI. Spinal Cord. 47(6), 496–498 (2009)

Biering-Sorensen, I., Hansen, R., Biering-Sorensen, F.: Sexual function in a traumatic spinal cord injured population 10–45 years after injury. J. Rehabil. Med. 44(11), 926–931 (2012)

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant no. R01 HD082122), a Diversity Supplement Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Mara Nery-Hurwit and Maryam Berri. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Mara Nery-Hurwit and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

As this is a scoping review and no participants were recruited, no ethical approval was required.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nery-Hurwit, M.B., Berri, M., Silveira, S. et al. A Scoping Review of Literature on Sexual Health and Wellness in Women with Spinal Cord Injury. Sex Disabil 42, 17–33 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-024-09834-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-024-09834-1