Abstract

The present study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a Sex Education Intervention on sexual knowledge in a group of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities. This research was conducted in a pretest-posttest design with a control group. The sample included 30 female adolescents with intellectual disabilities that were selected through convenience sampling and randomly divided into two groups: an experimental group and a control group (15 participants in each group). The experimental group received 18 sessions of a Sex Education Intervention while the control group did not receive this intervention. Assessment of Sexual Knowledge in Adolescents (ASKA) was used to measure sexual knowledge of the adolescents. The results showed that Sex Education Intervention improved general sexual knowledge and subscales like parts of the body, public and private parts and places, puberty, relationships, social sexual boundaries, safe sex practices, and sex and the law in the experimental group. However, no effect of the intervention was observed in subscales of masturbation and sexuality. The present research emphasizes the importance of Sex Education Intervention in increasing sexual knowledge in female adolescents with intellectual disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People with intellectual disabilities have sexual desires despite delayed sexual development, which may put them at risk of sexual abuse [29, 19]. It has been reported that people with intellectual disabilities do not have enough information about sex and sexuality [32], [38] and their sexual knowledge is less than their peers with typical development [21], [35] showed that sexual knowledge is positively correlated with cognitive function. That is, the more cognitive ability a person possesses, the more sexual knowledge that person achieves from a variety of sources. Therefore, having adequate knowledge about sexuality and sexual health through education is so important [36]. The sexual edication is especially important for people with disabilities, as they are more at risk of sexual abuse than people without disabilities by relatives, friends, caregivers, and even family members [8].

Sex education is an efficient method to increase the sexual knowledge of people with intellectual disabilities [20]. A Sex Education Intervention is a curriculum based on teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical, and social aspects of sexual activity, which aims to empower children and adolescents with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values. The Sex Education Intervention leads to an understanding of health, well-being, and human dignity, the respectful development of social and sexual relationships, and the understanding and protection of individual rights throughout life [42]. Ketting and Ivanova [18] believe that Sex Education Interventions support the all-round development of children and adolescents. He also believes that Sex Education Interventions aim to help young people achieve a positive view of sex and the right knowledge to make health-based decisions about their sex lives.

The effectiveness of Sex Education Intervention has been shown in different studies. For example, Tshomo et al. [40] reported that after a Sex Education Intervention, the knowledge, attitudes, and sexual function of the participants were enhanced. Fernandes and Junnarkar [10] showed that Sex Education Interventions reduce abortion, and pregnancy, delay sexual initiation and promote safe sex in adolescents. Pownall et al. [27] found that mothers of adolescents with intellectual disabilities gave less sex education to their adolescents than mothers of adolescents without intellectual disabilities. In fact, mothers of adolescents with intellectual disabilities give sex education to their children with delay and in less detail. This is because they think that adolescents with intellectual disabilities are less inclined to have sex. According to Miles [24], families of adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Pakistan prefer teachers, older siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins to educate the adolescents informally about issues like changes due to puberty, personal hygiene, and appropriate relationships with the opposite sex.

In Iran, several studies have been conducted on sexual health and behavior in people with intellectual disabilities, including the experiences of parents of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities regarding sexual health and fertility [11], behavioral and sexual problems among people with intellectual disabilities [1], sexual health challenges of females with intellectual disabilities [13], assessment of sexual maturity among females [34], the effects of two educational methods on mothers’ knowledge, attitude and self-efficacy about the sexual health care of adolescents with intellectual disabilities [12], and the relationship between self-esteem and sexual self-concept in people with physical disabilities [33]. Note to say that although sex education has not been neglected in Islam [3], sex is a taboo in Iranian society.

Despite ample research on sexual health and behavior of people with intellectual disabilities in Iran, no study yet evaluated the effect of Sex Education Intervention on sexual knowledge of adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Like their peers with normal development, people with intellectual disabilities have sexual desire and experience sexual intercourse (see Kijak [19], Ramage [29]). But, due to a lack of sexual knowledge, they are at risk to unprotected sex and unwanted pregnancies [32]. In addition, due to cultural taboos in Iran, cognitive limitations, and poor communication and social skills (Ramaj, 2015), adolescents with intellectual disabilities do not receive adequate sex education. Therefore, sex education that corresponds to their cognitive abilities is very important in people with intellectual disabilities. The present research aimed to study the effectiveness of a Sex Education Intervention on the sexual knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities to answer the following questions:

Does Sex Education Intervention affect the total score of sexual knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities?

Does Sex Education Intervention affect the subscales of sexual knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities?

Method

Population, Sample, and Sampling Method

The population included all 13- to 18-year-old female adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Shiraz, studying under the auspices of the special education organization in 2020–2021. The sample included 30 female adolescents with intellectual disabilities that were selected through convenience sampling and randomly divided into two groups: an experimental group and a control group (15 participants in each group). Before starting the Sex Education Intervention, a sexual knowledge pre-test was administered to both groups. Following the administration of the Sex Education Intervention to the experimental group, both groups completed again the sexual knowledge test. It should be noted that after the end of the post-test, and to comply with research ethics, the Sex Education Intervention was also provided to the participants in the control group for 18 sessions.

Sex Education Intervention

We developed a Sex Education Intervention based on prior research by Reynolds [2], [6], [22] and [30]. So, we used an adapted Sex Education Intervention based on prior research in this field and Iranian-Islamic culture. This sex program was taught in 18 sessions and each session took 50 min. Table 1 shows the summary of Sex Education Intervention that used in this study.

Instrument

We used the Assessment of Sexual Knowledge in Adolescents (ASKA) that was developed by [31] in order to assess the sexual knowledge of participants. The questionnaire has 76 items and 9 subscales that assess sexual knowledge in the subfields of: parts of the body, public and private parts and places, puberty, masturbation, relationships, social sexual boundaries, sexuality, safe sex practices, and sex and the law. The scoring method of the questionnaire is based on the three-point Likert scale. Items were scored 0 for incorrect, 1 for partially correct (where applicable), and 2 for correct. The maximum score for the scale is 152. Face validity and content validity of this tool have been approved by 9 experts. The measure has split-half reliability that ranges from 0.70 to 0.94. Test-retest coefficients were reported as follow: (1) Parts of the body 0.93, (2) Public and private parts and places 0.89, (3) Puberty 0.89, (4) Masturbation 0.88, (5) Relationships 0.97, (6) Social-sexual boundaries 0.92, (7) Sexuality 0.96, (8) Safe sex practices 0.94, (9) Sex and the law 0.97. Test-retest coefficient for total ASKA questionnaire was reported 0.99. As test-retest coefficients over 0.80 indicated a good reliability, it means that the ASKA has a good (0.87, p = 002) to excellent stability (0.99, p = .000) over time [31]. The original English version of the ASKA was translated to Persian and then back-translated to English by an expert Iranian English professor. The back-translation was edited by a native English speaker and then retranslated to Persian. This latter version was used for the validity and reliability study in Iran. The researchers measured the reliability of the ASKA on a 100 sample of adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Shiraz obtaining a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91. Thus, the ASKA indicates a high degree of internal reliability. The content validity of the ASKA also was verified by six professors of psychology. Note to say that the reliability of the questionnaire was also calculated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total score was 0.73. It should be noted that the participants individually completed the paper and pencil version of ASKA. The questionnaire took between 20 and 35 min to complete (depending on the individual’s cognitive ability, mood, and rapport with the examiner).

Ethical Considerations

Parents gave consent for participation of their adolescents in this study. The parents were aware of the purpose of the study and their adolescents had the right to leave the study at any time. They were assured that all their information would remain confidential. The ethical review board of the regional special education organization approved the study.

Results

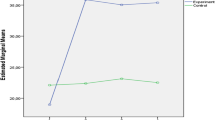

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of the scores of sexual knowledge in the experimental and control groups in the pre-test and post-test.

As shown in the Table 2, in the pre-test stage, the mean scores of an experimental group and the control group were almost equal regarding total score of sexual knowledge and the subscales of sexual knowledge (such as parts of the body, public and private parts and places, puberty, masturbation, relationships, social sexual boundaries, sexuality, safe sex practices, sex, and the law). However, the scores were higher in the experimental group following the intervention. To determine whether the changes were statistically significant, a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to answer the research question of whether the Sex Education Intervention affected the total score of sexual knowledge in female adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Note that before the ANCOVA was performed, its assumptions were examined, and the results showed that the condition of using an ANCOVA is met. Table 3 shows the results of ANCOVA.

The results showed that the Sex Education Intervention significantly increased the total score of sexual knowledge in the experimental group over the control group (p < .01). The ETA coefficient was 0.745, which means that 75% of the post-test score can be explained by the Sex Education Intervention.

Multiple t-tests with a Bonferroni adjustment were used to answer the research question of whether the Sex Education Intervention impacts on the subscales of sexual knowledge in female adolescents with intellectual disabilities. The results of Wilk’s lambda test showed that the effect of the group on the linear composition of the dependent variables was significant (F = 13.319, p < .001). Table 4 shows the results of multiple t-tests with a Bonferroni adjustment for the subscales of sexual knowledge in female adolescents with intellectual disabilities.

As shown in the Table 4, the main effect of group in the subscales of sexual knowledge for the following subscales were statistically significant: parts of the body (t = 3.86, p < .001), public and private parts and places (t = 7.38, p < .001), puberty (t = 2.98, p < .001), relationships (t = 6.80, p < .001), social sexual boundaries (t = 5.16, p < .001), safe sex practices (t = 8.61, p < .001)), and sex and the law (t = 5.74, p < .001). However, results showed no significant effect of Sex Education Intervention on masturbation (t = 2.75, p = .010) and sexuality (t = 2.53, p = .017).

Discussion

The aim of this research was to study the effectiveness of Sex Education Intervention on the sexual knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Iran. Findings showed that Sex Education Intervention has a significant effect on the total score of sexual knowledge in female adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Our finding is in line with [14] which showed the efficiency of the Sex Education Intervention for people with intellectual disabilities. This is because Sex Education Intervention teaches skills such as distinguishing normal sexual behavior from abnormal behavior, the appropriate approach to issues related to sexual behavior, age-appropriate behaviors, how sexual identity is formed, puberty, communication with peers, etc., that help adolescents with intellectual disabilities to increase their sexual knowledge, better understanding of sexual information, and easily adopt appropriate behaviors [41].

The results also showed that Sex Education Intervention has a significant effect on the subscales of parts of the body, public and private parts and places, puberty, relationships, social sexual boundaries, safe sex practices, sex, and the law in female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, but no effect was observed on masturbation and sexuality.

Regarding the effect of Sex Education Intervention on the parts of the body, the Sex Education Intervention, by providing correct information, increases the subjects’ knowledge about the good and bad touch of sexual organs and increases knowledge and awareness of sexual organs leads to protection against sexual harassment occurs [16], [44] showed that Sex Education Intervention for Chinese adolescents with disabilities is effective to familiar students with sexual issues, especially awareness of sexual organs.

To explain the effect of Sex Education Intervention on the public and private parts and places of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, the Sex Education Intervention improved the knowledge and skills related to public and private sexual places which result in adolescents making autonomous and informed decisions and take responsibility for the sexual well-being of themselves and others at the community level [5]. Similarly, Treacy et al. [39] showed that sexual health education was effective in people with intellectual disabilities.

In explaining the effect of Sex Education Intervention on the puberty of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, the Sex Education Intervention increases adolescents’ knowledge about sexual identity and gender roles and provides appropriate information about the physical, cognitive, social, emotional, and cultural aspects of sexual issues, reproduction, abortion, contraception, pregnancy, sex relationship, participation in an open and respectful social environment for sexual desire, provide sexual information about sexual maturity to adolescents with intellectual disabilities [17]. Coleman and Murphy [7] also showed that the Sex Education Intervention is a facilitating education to familiarize people with intellectual disabilities with sexual issues, especially their sexual maturity.

Regarding the effect of Sex Education Intervention on the subscale of relationships knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, the Sex Education Intervention promotes knowledge about healthy sexual relations and promotes safe sex at the right time by delaying the onset of sexual relationships and helping teens have a positive outlook on proper sex [10]. Similarly, Penny and Chataway [26] showed that the Sex Education Intervention helps the sexual competence of people with intellectual disabilities which improve the knowledge of these people in their sexual relations.

To account for the effect of Sex Education Intervention on the knowledge of the social-sexual boundaries of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, it can be stated that the goals of Sex Education Intervention depend on three main dimensions such as knowledge, attitude, and skill. Sex Education Intervention in the dimension of knowledge and attitude by teaching concepts such as recognizing the physical and sexual differences between females and males, recognizing sexual restraint, recognizing sexual norms and values accepted by society, recognizing the dimensions of sexual abuse and sexual violence, recognizing ways and sources of help getting information from others, recognizing gender equality, recognizing relationships, sexual dialogue and interests, recognizing gender roles and sexual identity, and learning to express useful feelings and needs, presents useful information and knowledge about social-sexual boundaries to female adolescents with intellectual disabilities [25]. Pownall et al. [27] also showed that Sex Education Intervention for adults with mental disabilities changes their attitudes, experiences, and the sexual support that they need.

In explaining the effect of Sex Education Intervention on the knowledge of safe sex practices of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, it can be mentioned that step-by-step Sex Education Intervention give adolescents correct information, skills, and values, and with this new knowledge and skills, they can improve their sexuality knowledge in order to experience safe sex at the right time [9]. In line with the above finding, the prior research showed that the Sex Education Intervention is a useful program to increase knowledge and understanding of people with mental disabilities regarding their sexual issues [28], [37].

Regarding the effect of Sex Education Intervention on sex and the law of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, it can be said that adolescents with intellectual disabilities learn during the process of Sex Education Intervention to control their sexual desires and express them according to human laws. That they do not express their sexual desires anywhere and anytime, maintain the sanctity of incest, and follow the rules of society in satisfying their sexual desires. In other words, through Sex Education Intervention, adolescents with intellectual disabilities learn to express their sexual behavior and sexual desires in a way that is acceptable to society [15]. In addition, Hayashi et al. [15] showed that Sex Education Intervention is efficient and useful in increasing social skills related to sexual issues of Japanese people with intellectual disabilities.

To account for the ineffectiveness of Sex Education Intervention on the masturbation of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, it can be stated that different cultures and religions have different values for marriage, long-term commitment, living together, sex, and related issues such as masturbation. In other words, a person’s cultural and religious values play an important role in sexual decision-making [42]. Masturbation is inappropriate in Iranian culture and is forbidden according to Islam. Probably for these reasons, Sex Education Intervention did not have a significant effect on the masturbation subscale.

Regarding the ineffectiveness of Sex Education Intervention on the sexuality of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, it can be mentioned that the negative attitude of society, family, and school about the sexual abilities of adolescents with intellectual disabilities makes adolescents unable to express their sexual desires. In addition, expressing sexual desire is an unacceptable behavior in Iranian society.

It should be noted that this study was performed only on female adolescents with intellectual disabilities, so conducting research with the participation of male adolescents with intellectual disabilities can help to generalize the findings. Sex education in Iran is accompanied with restrictions and regulations that have definitely affected the research process in this study.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that Sex Education Intervention is an effective program in improving the sexual knowledge of female adolescents with intellectual disabilities. The findings of the present research emphasize the importance of Sex Education Intervention for adolescents with intellectual disabilities.

References

Akrami, L., Davudi, M.: Comparison of behavioral and sexual problems between intellectually disabled and normal adolescent boys during puberty in Yazd, Iran. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci 8(2), 68–74 (2014)

Asagba, K., Burns, J., Doswell, S.: Sex and relationships education for Young people and adults with intellectual disabilities and Autism. Pavilion Publishing, Shoreham by Sea (2019)

Ashraah, M.M., Gmaian, I., Al-Shudaifat, S.: Sex education as viewed by Islam education. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 95(1), 5–16 (2013)

Berdychevsky, L.: Sexual health education for young tourists. Tour. Manag. 62, 189–195 (2017)

Bonjour, M., van der Vlugt, I.: (2018) Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Knowledge File. Utrecht: Rutgers International: For Sexual and ReproductiveHealth and Rights Availableonline: http://www.Rutgersinternational/sites/rutgersorg/files/PDF/knowledgefiles/20181218knowledge%20file_CSE.Pdf

Brown, F.J., Brown, S.: When Young People with Intellectual Disabilities and Autism Hit Puberty: A Parents’ Q&A Guide to Health. Sexuality and Relationships. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, USA (2016)

Coleman, E.M., Murphy, W.D.: A survey of sexual attitudes and Sex Education Interventions among facilities for the mentally retarded. Appl. Res. Ment. Retard. 1(3–4), 269–276 (1980)

Eastgate, G., Scheermeyer, E., Van Driel, M.L., Lennox, N.: Intellectual disability, sexuality and sexual abuse prevention: a study of family members and support workers. Aus. Fam. Physician 41(3), 135–139 (2012)

Eisenberg, M.E., Bernat, D.H., Bearinger, L.H., Resnick, M.D.: Support for comprehensive sexuality education: perspectives from parents of school-age youth. J. Adolesc. Health. 42(4), 352–359 (2008)

Fernandes, D., Junnarkar, M.: Comprehensive Sex Education: holistic Approach to biological, psychological and social development of adolescents. Int. J. School Health. 6(2), 1–4 (2019). doi: https://doi.org/10.5812/intjsh.63959

Goli, S., Noroozi, M., Salehi, M.: Parental experiences about the sexual and Reproductive Health of adolescent girls with intellectual disability: a qualitative study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 25(3), 254–259 (2020)

Goli, S., Noroozi, M., Salehi, M.: Comparing the effect of two educational interventions on mothers’ awareness, attitude, and self–efficacy regarding sexual health care of educable intellectually disabled adolescent girls: a cluster randomized control trial. Reproductive Health. 18(54), 1–9 (2021)

Goli, S., Noroozi, M., Salehi, M.: Sexual Health Challenges of the iranian intellectually disabled adolescent girls: a qualitative study. Int. J. Pediatr. 10(3), 15630–15639 (2022)

Gonzálvez, C., Fernández-Sogorb, A., Sanmartín, R., Vicent, M., Granados, L., García-Fernández, J.M.: Efficacy of Sex Education Interventions for people with intellectual disabilities: a meta-analysis. Sex. Disabil. 36(4), 331–347 (2018)

Hayashi, M., Arakida, M., Ohashi, K.: The effectiveness of a sex education intervention facilitating social skills for people with intellectual disability in Japan. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 36(1), 11–19 (2011)

Jin, Y., Chen, J., Jiang, Y.: Evaluation of a sexual abuse prevention education program for school-age children in China: a comparison of teachers and parents as instructors. Health Educ. Res. 32(4), 364–373 (2017)

Keogh, S.C., Stillman, M., Awusabo-Asare, K., Sidze, E., Monzón, A.S., Motta, A., Leong, E.: Challenges to implementing national comprehensive sexuality education curricula in low- and middle-income countries: case studies of Ghana, Kenya, Peru and Guatemala. PLoS One. 20(2), 119–137 (2018). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1625762

Ketting, E., Ivanova, O.: Sexuality education in Europe and Central Asia: State of the art and recent developments. An Overview of 25 Countries, Cologne: BZgA. https://www.bzga Sexuality Education in Europe and Central Asia-State of the Art and Recent Developments (an Overview of 25 Countries) Federal Centre for Health Education, BZgA. (2018)

Kijak, R.J.: A Desire for Love: considerations on sexuality and sexual education of people with intellectual disability in Poland. Sexuality and Disability Journal. 29(1), 65–74 (2011)

Lafferty, A., McConkey, R., Simpson, A.: Reducing the barriers to relationships and sexuality education for persons with intellectual disabilities. Intellect. Disabil. 16(1), 29–43 (2012)

Langdon, P.E., Talbot, T.J.: Locus of control and sex offenders with an intellectual disability. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 50(4), 391–401 (2006)

Lindsay, W.R.: The Treatment of sex Offenders with Developmental Disabilities: A Practice Workbook. John Wiley & Sons, UK (2009)

McKenzie, K., Milton, M., Smith, G., Ouellette-Kuntz, H.: Systematic review of the prevalence and incidence of intellectual disabilities: current trends and issues. Curr. Dev. Disorders Rep. 3(2), 104–115 (2016)

Miles, M.: Walking delicately around mental handicaps, sex education, and abuse in Pakistan. Child Abuse Rev. 5, 263–274 (1996)

Gougeon, N.A.: Sexuality education for students with intellectual disabilities, a critical pedagogical approach: outing the ignored curriculum. Sex Educ. 9(3), 277–291 (2009)

Penny, R.E.C., Chataway, J.E.: Sex education for mentally retarded persons. Aus. New Zealand J. Develop. Disabil. 8(4), 204–212 (1982)

Pownall, J.D., Jahoda, A., Hastings, R.: Sexuality and sex education of adolescents with intellectual disability: mothers attitudes, Experiences, and support needs. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 50(2), 140–154 (2012)

Quesado, A., Vieira, M., Quesado, P.: Effects of a sexual education program for people with intellectual disability. Millenium-Journal of Education, Technologies, and Health. 17, 97–105 (2021)

Ramage, K.: Sexual health education for adolescents with intellectual disabilities: A literature review.The Saskatchewan Prevention Institute,1–36. (2015)

Reynolds, K.E.: What Is Sex? A Guide for People with Autism. Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, UK (2021)

Richards, S.: Exploring sexual knowledge and risk in the assessment and treatment of adolescent males with intellectual developmental disorders who display harmful sexual behaviour. University of Nottingham (2018)

Rutman, S., Taualii, M., Ned, D., Tetrick, C. (2012) Reproductive health and sexual violence among urban American Indian and Alaska Native young women Select findings from the National Survey of Family Growth (2002). Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16: 347–352.

Salehi, M., Tavakol, K., Shabani, H., M., Ziaei, T.: The relationship between self-esteem and sexual Self-Concept in people with physical-motor disabilities. Iran. Red Crescent Med J. 17(1), 1–7 (2015)

Mirzaee, H.S., Mosallanejad, A., Rabbani, A., Setoodeh, A., Abbasi, F., Sayarifard, F., Memari, A.H.: Assessment of sexual maturation among girls with special needs in Tehran, Iran. Iran. J. Pediatr. 26(5), 1–5 (2016)

Sinclair, J., Unruh, D., Lindstrom, L., Scanlon, D.: Barriers to sexuality for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a literature review. Educ. Train. autism Dev. Disabil. 50, 3–16 (2015)

Verhoef, M., Barf, H.A., Vroege, J.A., Post, M.W., Van Asbeck, F.W., Gooskens, R.H., Prevo, A.J.: Sex education, relationships, and sexuality in young adults with spina bifida. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86(5), 979–987 (2005)

Stein, S., Kohut, T., Dillenburger, K.: The importance of sexuality education for children with and without intellectual disabilities: what parents think. Sex. Disabil. 36(2), 141–148 (2018)

Timma, S.: Adolescent sex offenders with mental retardation literaturereview and assessment considerations, aggression and violent behavior. J. Intellect. Disable Res. 10(4), 35–39 (2002)

Treacy, A.C., Taylor, S.S., Abernathy, T.V.: Sexual health education for individuals with disabilities: a call to action. Am. J. Sexuality Educ. 13(1), 65–93 (2018)

Tshomo, U., Sherab, K., Howard, J.: Bhutanese trainee teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices about sex and sexual health: exploring the impact of intervention programmes. Sex Educ. 20(6), 627–641 (2020)

Turnbull, T., Schaik, P.V., Wersch, A.V.: A review of parental involvement in sex education: the role for effective communication in british families. Health Educ. J. 67(3), 182–195 (2008)

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Digital Library:. Facing the Facts: The Case for Comprehensive Sexuality Education. (2019). http://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/MINEDU/6618. 1–15

Vasiliki, D., Οurania, T., Νikolaos, M., Kyriakos, P.: Adolescents with intellectual disability and sexuality matters: opinions, experiences, and needs. Dev. Adolesc. Health. 2(1), 15–21 (2022)

Wu, J., Zeng, S.: Sexuality education for children and youth with disabilities in Mainland China: systematic review of thirty years. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 116, 105197 (2020)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hemati Alamdarloo, G., Moradi, S., Padervand, H. et al. The Effect of Sex Education Intervention on Sexual Knowledge of Female Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities. Sex Disabil 41, 663–676 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09777-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09777-z