Abstract

Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) may experience greater risk of sexually transmitted infections, higher rates of sexual abuse, and decreased sexual health knowledge, emphasizing the need for accessible, comprehensive sexual health education. The purpose of this scoping review was to identify the extent and nature of sexual health education interventions among individuals with I/DD ages 15–24 years. Six studies were included in the review. They investigated sexual health interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder and mild I/DD, covered a wide range of topics (e.g. puberty, healthy relationships), included multiple learning activities (e.g. illustrations, activity-based learning), and measured behavior and sexual health knowledge outcomes. Future research is needed in this area to assess intervention effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) include pediatric-onset disabilities. Intellectual disability (ID) is characterized by delays and difficulties in adaptive behavior and intellectual functioning with an age of onset before 18 years [1]. The prevalence of ID in the United States and across the world is about 1% [2]. Developmental disability (DD) is a long-term disability that can impact intellectual functioning, physical functioning, or both, and the delay must occur before the age of 22 years in order for an individual to receive this diagnosis [1]. The prevalence of DD is approximately 15%, impacting 1 in 6 children in the United States from 2006 to 2008 [3].

Individuals with I/DD often experience difficulties accessing postsecondary educational opportunities [4]. One content area in which individuals with I/DD may lack access is sexual health education, as evidenced by studies that show that, although parents and support workers feel it is important for individuals with I/DD to receive this information, mothers of children with I/DD held more cautious attitudes about contraception, learning about sexual health, and decisions about intimate relationships than mothers of children without I/DD [5]. The mothers of children with I/DD also emphasized that schools should be providing comprehensive sexual health education (SHE), showing an even greater preference than parents of children without I/DD [5]. In spite of a desire for schools to provide sexual health education to children with I/DD, evidence points to a lack of adequate sexual health education for school-age children with I/DD. Wilson and Frawley [6] found that many adults with I/DD in a transition to work program had not yet received sexual health education and employees often had to address these concerns and provide sexual health information [6]. Not surprisingly, since individuals with I/DD have difficulty accessing SHE, they also demonstrate decreased understanding of sexual and reproductive health information [7,8,9]. Specifically, individuals with I/DD demonstrate decreased levels of knowledge regarding sex-related topics such as masturbation, pregnancy, safe sexual intercourse, reproductive health, and same-sex relationships [7, 8], which can increase their risks of poor sexual health.

The lack of knowledge about sexual and reproductive health information may put individuals with I/DD at increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and sexual abuse or assault. In fact, one cross-sectional study using special education and Medicaid data for the calendar year 2002 found that males with a learning disability, such as ADHD, had a 36% increase in the odds of having an STI and females with I/DD had a 37% increase likelihood of having an STI [10]. Interestingly, an analysis of privately insured individuals with I/DD did not find an increased risk of STI [11]. In fact, I/DD appeared to be protective of STIs among those whom are privately insured [11]. This may reflect the impact of health disparities, health care access, or health system differences on sexual health and requires further investigation [11]. Decreased sexual health knowledge may also increase the likelihood of experiencing sexual abuse or assault. Individuals with I/DD are anywhere between four and seven times more likely than their peers without I/DD to experience sexual abuse [12,13,14].

Sexual education is designed to help adolescents understand sexuality and sexual health, as well as gain the information to make safe decisions currently and in the future [15]. Effective sexual health education increases sexual knowledge, while decreasing rates of STIs [16] and preventing sexual abuse [15]. Currently, there is no legislation requiring sexual education to be provided in school systems nationwide; instead, the type of sexual education available depends on state legislation or school policies. Recently, recommendations were developed for sexual health education for the general school-aged population by the Sexuality Information Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), which comprised several stakeholders including teachers, medical and public health professionals, and adolescents [17]. Recommendations from SIECUS include seven components within comprehensive sexual health education: anatomy and physiology, puberty and adolescent development, identity, pregnancy and reproduction, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV, healthy relationships, and personal safety [17]. Anatomy and physiology includes concepts such as body part identification and labeling. Puberty and adolescent development covers concepts surrounding changes in individuals’ bodies, emotions, mood, and interests. This also involves education surrounding masturbation, menstrual hygiene, and overall bodily hygiene. Identity refers to gender identification, sexual orientation, and sexual expression. Pregnancy and reproduction comprises information about how one becomes pregnant, the developing fetus, birth, and parenthood. This also may include preventing unwanted pregnancies and contraception. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS covers education surrounding infections, preventing infections, and condom use. The component of healthy relationships entails healthy friendships and intimate relationships, but also includes information about boundaries and different types of relationships (i.e. familial, friendship, intimate relationships, and coworkers). Finally, personal safety is defined as identifying and preventing harassment, bullying, violence, and abuse, including sexual abuse [17]. These types of comprehensive education programs are an effective strategy to help adolescents delay their initiation of sexual intercourse, reduce the frequency of intercourse, reduce the number of sexual partners, and increase condom or contraceptive use [16].

The purpose of this review was to answer the question: What is the scope of sexual health education interventions used with adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 years with I/DD? This age range was determined based on the high rates of STIs among the general population within this age group [18]. The objectives of this study are to (1) identify and describe the common, available, and/or effective sexual health education interventions used with adolescents and young adults with I/DD and (2) determine how these interventions align with the recommendations developed by SIECUS. To this end, a scoping review was utilized to examine the extent and nature of what is currently being done in the area of sexual health education for individuals with I/DD and to identify gaps in the literature for future research.

Methods

This scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [19]. Eligibility criteria included adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 years with I/DD, including intellectual disability, developmental disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cerebral palsy (CP), Down syndrome, Spina Bifida, Prader Willi, and fetal alcohol syndrome disorders. The search strategy was conducted in August 2018 and consisted of the following databases: ERIC, CINAHL, Medline, and PsychInfo. The search strategy utilized included: ((cerebral AND palsy) OR cp OR (down AND syndrome) OR (trisomy AND 21) OR (fetal AND alcohol AND syndrome) OR autism OR asd OR (autism AND spectrum AND disorder) OR (spina AND bifida) OR (prader-willi AND syndrome) OR intellectual OR (developmental AND disability)) AND (adolescents OR teenagers OR (young AND adults)) AND ((sexual AND health AND education)) OR ((sexual AND health AND program)) AND (knowledge OR attitude OR behavior OR communication). This search was limited to academic journals and peer reviewed articles published between the years 2000–2018.

Two authors screened all of the titles and abstracts, full-text articles, and completed data extraction, while a third author was consulted to determine the status of conflicting reviews. Articles were excluded if they did not analyze an intervention, if they did not include any of the seven components of comprehensive sexual health education recommended by SIECUS [17], if there were no outcomes reported, or if they were not within the age range specified in the inclusion criteria. All levels of evidence were included in this study. The authors used Covidence [20], a review management software, to organize and manage screening, full text reviews, data extraction, and bias assessments. Data were compiled into an extraction table including study design, population (i.e. inclusion criteria and sample), measures, and results and summarized in an evidence table (Table 1). Study results in the evidence summary included quantitative analyses (e.g. p values, means, and standard deviations) and qualitative analyses. Authors categorized qualitative results into three categories: knowledge improved, unchanged, or knowledge decreased. Risk of bias was assessed according to the Cochrane guidelines (Table 2).

Thematic and numeric analyses were also completed (Table 3). The strength of evidence in Table 3 was determined using the American Occupational Therapy Associations revised strength of evidence based on the guidelines of the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force [27, 28]. A concept map was created to identify the overarching themes and their subthemes (Supplementary Figure 1) and further thematic analyses were completed and agreed on by two authors. Numeric analysis included the number of articles in which themes identified above appeared, based on the concept map, which was color coded to quantify how often each theme and subtheme appeared within the literature. Finally, to understand the extent to which interventions provided comprehensive sexual health education (per SIECUS recommendations), data were extracted to identify which components of comprehensive sexual health education were covered. These analyses were integrated with the thematic analysis and are described in Table 3.

Results

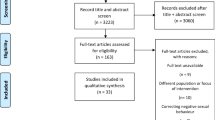

This search yielded 1463 studies and 56 duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). From the titles and abstracts that were screened, 24 were included for full text review. Of the 24 articles, six were ultimately included. The study summaries and risk of bias assessments can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. The study design, population, interventions, measures, and results were extracted from each study and summarized in an evidence table (Table 1).

Studies included in this analysis described sexual health interventions conducted in an individual setting [21, 24] or in a group setting [22, 23, 25]. Interventions were primarily adolescent- and young adult-centered, but two included a parent education training [25, 26] and one provided structured contact reports to keep parents informed [21].

Thematic analyses are depicted in Table 3 and in the concept map (Supplementary Figure 1). The following themes describe the nature and scope of the interventions: sample, intervention modalities, educators and outcomes.

Sample

Only one study included an intervention designed specifically for individuals with ID [23]. Garwood and McCabe [23] compared two interventions, one of which included three men ages 12–25 years with mild ID [23]. No studies assessed the effects of sexual health interventions for individuals with moderate to profound ID. The remaining five studies were designed for adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Specifically, three studies were designed for all adolescents (age range from 9 to 20 years) [21, 24, 26], one study was designed specifically for early and middle adolescents (12–16 years) [25], and one study was designed for older adolescents (ages 15–17 years) [22]. Two of these studies included young adults with ASD (ages 19–20 years) [24, 26]. Of the five studies that were designed specifically for individuals with ASD, two did not include details about severity [21, 26], two reported inclusion criteria geared towards individuals with mild ASD [24, 26], and only one included individuals with mild to severe ASD [22].

Educators

A range of professionals with education, training, and/or experience in fields supporting individuals with I/DD provided the sexual health interventions. These included researchers [26], therapeutic staff [22], behavioral specialists and psychology doctorate students [25], certified trainers of the Tackling Teenage Training Program [24], professionals with a bachelor’s or master’s degree in psychology or social services [21] or organizations serving individuals with disabilities [23]. One study reported the educator that provided the parent component had experience working with children with ASD [25] and an additional two studies reported requiring at least 3 years of experience working with this population [21, 24].

There was also an additional training component identified across several studies [21, 22, 24]. One study required educators to undergo a 40-hour training [22] and two studies required a 2-day training before implementing the sexual health intervention [21, 24]. Additionally, several studies required educators document their adherence to the intervention protocol using either meetings to check in [22] or self-report [21, 24].

Intervention Modalities

Each intervention used a multimodal approach with various combinations. The most common intervention modalities included illustrations (i.e. pictures and videos) [21, 23,24,25], didactic teaching [21, 23,24,25], and activity-based learning [21, 23,24,25], which included active experiential learning through role play, modeling, and video modeling. Other interventions included behavioral interventions such as immediate redirection and positive reinforcement [22], clear instructions [25], feedback (i.e. corrective feedback, prompting, and repeated practice) [25], structured routines [21, 22], experiential take-home assignments [21, 24], and tests or quizzes [21, 24]. One study did not report the modalities that were utilized to teach the content of their sexual health education program [26].

Outcomes

Several intervention outcomes were assessed across the studies, including changes in behavior, sexual health knowledge, and interpersonal boundaries. Several studies assessed multiple outcomes. Three studies examined behavioral outcomes, one study used the problem behavior checklist and odd sexual behavior checklist [26], one study used the sexual behavior scale [25], and one used a parent-reported scale to measure behavioral outcomes [21]. Five studies examined psychosexual knowledge, one study used a curriculum-based measure [22], three studies used an adolescent questionnaire [21, 24, 25], one also used a parent questionnaire of adolescent knowledge [25], and one used the Sexual Knowledge, Experience, Feelings and Needs Scale for people with Intellectual Disability (Sex KEN-ID) [23]. Only one study examined interpersonal boundaries [21].

Components of Comprehensive Sexual Health Education

As previously described, SIECUS recommends including seven components within comprehensive sexual health education [17]. Each intervention was analyzed to determine whether they described including information from each of these components in Table 4.

Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to examine the scope of sexual health education interventions with adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 years with I/DD. Overall, the literature lacks high quality studies evaluating the effects of sexual health education interventions for individuals with I/DD; specifically, only one study conducted a randomized control trial. This is an important gap in our understanding of the most effective way to provide sexual health education to individuals with I/DD, and points to a critical need for larger, more rigorous work in this area. However, while the quality of these studies is low, the majority of the studies demonstrated improvement in sexual health knowledge and all of the studies that included behavioral outcomes reported improvements. This consistency across studies is important and suggests that commonalities in the design and delivery of these interventions should be identified and studied further. Several common characteristics of these studies may provide important direction and insights into designing larger efficacy and effectiveness trials.

The studies included in this review utilized multimodal approaches to sexual health education interventions including didactic teaching, illustrations, and activity-based learning with individuals with ASD. This aligns with best practices for interventions targeting social skill development among individuals with ASD [29]. The majority of these interventions were conducted in a group setting led by professionals with experience working with this population and with training about the program content. This is common among interventions designed for individuals with I/DD, specifically in the area of interventions to improve employment skills, outcomes, and social skills [30, 31]. Although there is a current trend to expand medically accurate sexual health education through the internet and social media, classroom or community-based group settings are the most common platform in the United States at this time [32]. The content described in these interventions most commonly included healthy relationships, anatomy and physiology, and puberty and adolescent development. These topics are relevant to the I/DD population, as individuals with intellectual disabilities find it difficult to initiate and maintain sexual relationships and friendships, and demonstrate decreased knowledge of sexual and reproductive health, including body part identification and puberty [7,8,9, 33,34,35]. In addition, evidence points to the need for further emphasis on pregnancy, STIs and HIV, and personal safety. In particular, women with I/DD are more likely to smoke during pregnancy, less likely to receive prenatal care during the first trimester, and are at an increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes [36]. Also, individuals with a learning disability are more likely to have STIs and individuals with I/DD are more likely to experience sexual abuse than their peers without I/DD [10, 12,13,14]. The current literature also points to the importance of starting sexual health education earlier in adolescents, since individuals in early and middle adolescents demonstrated the greatest improvements in sexual health knowledge [21, 24]. These characteristics may represent the active ingredients of successful sexual health interventions, which can be assessed in further trials.

Several key features of comprehensive sexual health education were not addressed in these studies and represent important additions to future intervention studies. The majority of these studies included content on personal safety, however it is unclear as to whether it was included in a comprehensive manner and the majority of studies did not include information about STIs and HIV/AIDS. Given the vulnerability of young adults in this population [10, 12,13,14], it is critical that sexual health education includes and measures this content.

Another key finding was that, while most of the included studies measured both knowledge and behavioral outcomes, there was a lack of consistency in the selection and rigor of study assessments. The measures used to assess sexual health knowledge varied significantly across studies and only one study utilized a questionnaire with established psychometric properties. The variance and lack of standardization of outcome measures prevents meaningful comparisons across studies and affects confidence in the study findings.

Another knowledge gap identified by this review was our understanding of sexual health education for individuals with ID. The majority of the studies implemented sexual health education interventions for individuals with ASD; only one study included individuals with ID specifically. What we understand from these studies is that for individuals with mild ASD, the following approaches seem to improve sexual health knowledge and behavior: multimodal interventions including illustrations, didactic teaching, activity-based learning, structured routines, take-home assessments, tests and quizzes. Tailoring the intervention to individuals with ASD ensures that content important for these young adults is covered. For example, individuals with ASD experience difficulties with social skills, which may explain why the Healthy Relationships component was included in all of these studies. However, individuals with other disabilities may have different needs, requiring more content in other domains or different intervention modalities to ensure effective learning. For example, an individual with fine motor delays may not want to participate in activity-based learning using worksheets where writing is required, and may need a different intervention modality to learn best. Because the current literature emphasizes education for individuals with ASD, few conclusions can be drawn about what works for individuals with other diagnoses.

A similar need exists for individuals with I/DD who have moderate to severe disability. This body of work provided insights into the type of educational modalities and learning activities that seem to work for individuals with mild impairments. As outlined above, approaches such as illustrations, didactic teaching, and activity-based learning were used in these interventions and all studies reported improvements in sexual health knowledge. Only one of the six studies included individuals with moderate to severe I/DD [22]. This is problematic because individuals with moderate to profound I/DD are at a greater risk of experiencing sexual abuse [12,13,14] and are less likely to receive sexual health education in the school setting [37]. Moving forward, it will be important for the field to design and test high quality interventions for all individuals with I/DD, but particularly for those with more significant disability.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with the scoping review process. Specifically, all levels of evidence were included in this review, which included low quality evidence with small samples and increased risk for biases. However, this scoping review utilized the PRISMA scoping review guidelines to improve quality, and the overall purpose was not to determine the effectiveness of these interventions, but instead to describe the nature of recent research on sexual health education for adolescents and young adults with I/DD.

Future Directions

Future programs should include all seven components of comprehensive sexual health education; specifically, STIs and identity need to be incorporated into current interventions. As previously described, comprehensive sexual health education programs were found to be more effective than other programs among the general population [16]. Additionally, one study found increased rates of STIs among those receiving special education services when compared to peers without disabilities [10]. Also, individuals with disabilities are as likely, or more likely, to experience gender differences [38] or identify with any sexual orientation [39], which emphasizes the importance of including identity in sexual health education interventions.

Future research is needed to better understand the effectiveness of these multimodal interventions and to identify the best combination of interventions for each population. Specifically, there is a need for larger trials, studies in individuals with diagnoses other than ASD, and studies of individuals with moderate and severe disability. Additionally, studies should include standardized outcome measures with established psychometric properties. Sexual health education intervention programs utilized in research should be adequately described, including but not limited to duration, components included, materials utilized, and protocol, in order to duplicate findings.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC (2013)

Maulik, P.K., Mascarenhas, M.N., Mathers, C.D., Dua, T., Saxena, S.: Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 32(2), 419–436 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.018

Boyle, C.A., Boulet, S., Schieve, L.A., Cohen, R.A., Blumberg, S.J., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Visser, S., Kogan, M.D.: Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US Children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics 127(6), 1034–1042 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2989

Plotner, A.J., Marshall, K.J.: Postsecondary education programs for students with an intellectual disability: facilitators and barriers to implementation. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 53(1), 58–69 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-53.1.58

Pownall, J.D., Jahoda, A., Hastings, R.P.: Sexuality and sex education of adolescents with intellectual disability: mothers’ attitudes, experiences, and support needs. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 50(2), 140–154 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.2.140

Wilson, N.J., Frawley, P.: Transition staff discuss sex education and support for young men and women with intellectual and developmental disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 41(3), 209–221 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1162771

Abbott, D., Howarth, J.: Still off-limits? Staff views on supporting gay, lesbian and bisexual people with intellectual disabilities to develop sexual and intimate relationships? J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 20(2), 116–126 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00312.x

Bowman, R.A., Scotti, J.R., Morris, T.L.: Sexual abuse prevention: a training program for developmental disabilities service providers. J. Child Sex. Abuse. 19(2), 119–127 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/10538711003614718

Dukes, E., McGuire, B.E.: Enhancing capacity to make sexuality-related decisions in people with an intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53(8), 727–734 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01186.x

Mandell, D.S., Eleey, C.C., Cederbaum, J.A., Noll, E., Katherine Hutchinson, M., Jemmott, L.S., Blank, M.B.: Sexually transmitted infection among adolescents receiving special education services. J. Sch. Health 78(7), 382–388 (2008)

Schmidt, E.K., Hand, B.N., Simpson, K.N., Darragh, A.R.: Sexually transmitted infections in privately insured adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Comp. Eff. Res. (2019). https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2019-0011

Jones, L., Bellis, M.A., Wood, S., Hughes, K., McCoy, E., Eckley, L., Bates, G., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T., Officer, A.: Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet 380(9845), 899–907 (2012)

Spencer, N., Devereux, E., Wallace, A., Sundrum, R., Shenoy, M., Bacchus, C., Logan, S.: Disabling conditions and registration for child abuse and neglect: a population-based study. Pediatrics 116, 609–613 (2005)

Sullivan, P.M., Knutson, J.F.: Maltreatment and disabilities: a population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse Negl. 24(10), 1257–1273 (2000)

Barger, E., Wacker, J., Macy, R., Parish, S.: Sexual assault prevention for women with intellectual disabilities: a critical review of the evidence. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 47(4), 249–262 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-47.4.249

Kirby, D., National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (U.S.): Emerging Answers, 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, Washington, DC (2007)

Future of Sex Education Initiative. National sexuality education standards: core content and skills, K-12 [a special publication of the Journal of School Health]. Retrieved February 20, 2018, from http://www.futureofsexeducation.org/documents/josh-fose-standards-web.pdf (2012)

Torrone, E., Papp, J., Weinstock, H. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14–39 years—United States, 2007–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2014, September 26)

Tricco, A.C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K.K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M.D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Straus, S.E.: PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169(7), 467 (2018). https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved November 2018, from https://www.covidence.org (2019)

Visser, K., Greaves-Lord, K., Tick, N.T., Verhulst, F.C., Maras, A., van der Vegt, E.J.M.: A randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of the Tackling Teenage psychosexual training program for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58(7), 840–850 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12709

Pask, L., Hughes, T.L., Sutton, L.R.: Sexual knowledge acquisition and retention for individuals with autism. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 4(2), 86–94 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1130579

Garwood, M., McCabe, M.P.: Impact of sex education programs on sexual knowledge and feelings of men with a mild intellectual disability. Educ. Train. Mental Retard. Dev. Disabil. 35, 269–283 (2000)

Dekker, L.P., van der Vegt, E.J.M., Visser, K., Tick, N., Boudesteijn, F., Verhulst, F.C., Maras, A., Greaves-Lord, K.: Improving psychosexual knowledge in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: pilot of the tackling teenage training program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45(6), 1532–1540 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2301-9

Corona, L.L., Fox, S.A., Christodulu, K.V., Worlock, J.A.: Providing education on sexuality and relationships to adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. Sex. Disabil. 34(2), 199–214 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-015-9424-6

Banerjee, M., Ray, P., Panda, A. Role of sex education on odd sexual and problem behavior: a study on adolescents with autism. Community Psychology Association of India (2013)

American Occupational Therapy Association Press. Guidelines for systematic reviews. Retrieved April 2019, from: https://ajot.submit2aota.org/journals/ajot/forms/systematic_reviews.pdf (2017)

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Grade definitions. Retrieved April 2019, from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions (2012)

Ke, F., Whalon, K., Yun, J.: Social skill interventions for youth and adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 88(1), 3–42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317740334

Gilson, C.B., Carter, E.W., Biggs, E.E.: Systematic review of instructional methods to teach employment skills to secondary students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res. Pract. Pers. Severe Disabil. 42(2), 89–107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796917698831

Reichow, B., Steiner, A.M., Volkmar, F.: Social skills groups for people aged 6 to 21 with autism spectrum disorders [ASD]. Cochrane Libr. 7, 1–50 (2013)

Hall, K.S., McDermott Sales, J., Komro, K.A., Santelli, J.: The state of sex education in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 58(6), 595–597 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.032

Schaafsma, D., Kok, G., Stoffelen, J.M., Curfs, L.M.: Identifying effective methods for teaching sex education to individuals with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J. Sex Res. 52(4), 412–432 (2014)

Abbott, D., Burns, J.: What’s love got to do with it? Experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people with intellectual disabilities in the United Kingdom and views of the staff who support them. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy J. NSRC 4(1), 27–39 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2007.4.1.27

Miller, H.L., Pavlik, K.M., Kim, M.A., Rogers, K.C.: An exploratory study of the knowledge of personal safety skills among children with developmental disabilities and their parents. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 30, 290–300 (2017)

Mitra, M., Parish, S.L., Clements, K.M., Cui, X., Diop, H.: Pregnancy outcomes among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 48(3), 300–308 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.032

Barnard-Brak, L., Schmidt, M., Chesnut, S., Wei, T., Richman, D.: Predictors of access to sex education for children with intellectual disabilities in public schools. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 52(2), 85–97 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-52.2.85

Janssen, A., Huang, H., Duncan, C.: Gender variance among youth with autism spectrum disorders: a retrospective chart review. Transgend. Health 1(1), 63–68 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0007

Gilmour, L., Schalomon, P.M., Smith, V.: Sexuality in a community based sample of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism. Spectr. Disord. 6(1), 313–318 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.06.003

Funding

There was no funding for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Ms. Schmidt has intramural research grants from the Ohio State University to support a study analyzing the opinions of health care providers, educators, parents, and individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities regarding sexual health education and to develop interactive learning activities to facilitate effective education. She also has received honorariums to present on the need for effective sexual health education among individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities for the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy and ContinueEd.com.

Human and Animal Rights

This review did not consist of human subjects research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, E.K., Brown, C. & Darragh, A. Scoping Review of Sexual Health Education Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities. Sex Disabil 38, 439–453 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-019-09593-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-019-09593-4