Abstract

This paper details a unique data experiment carried out at the University of Amsterdam, Center for Digital Humanities. Data pertaining to monographs were collected from three autonomous resources, the Scopus Journal Index, WorldCat.org and Goodreads, and linked according to unique identifiers in a new Microsoft SQL database. The purpose of the experiment was to investigate co-varied metrics for a list of book titles based on their citation impact (from Scopus), presence in international libraries (WorldCat.org) and visibility as publically reviewed items (Goodreads). The results of our data experiment highlighted current problems related citation indices and the way that books are recorded by different citing authors. Our research further demonstrates the primary problem of matching book titles as ‘cited objects’ with book titles held in a union library catalog, given that books are always recorded distinctly in libraries if published as separate editions with different International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs). Due to various ‘matching’ problems related to the ISBN, we suggest a new type of identifier, a ‘Book Object Identifier’, which would allow bibliometricians to recognize a book published in multiple formats and editions as ‘one object’ suitable for evaluation. The BOI standard would be most useful for books published in the same language, and would more easily support the integration of data from different types of book indexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For research assessments across the humanities and in some fields within the social sciences (SSH), journal citation indices are inadequate (Archambault et al. 2006; Nederhof 2006; Ossenblok et al. 2012; Sivertsen and Larsen 2012; van Leeuwen 2013). Some scholars suggest that a special European database could be developed or that national repositories might provide a solution to this problem (Hicks and Wang 2009; Martin et al. 2010; Moed et al. 2009); while others have given attention to Google Books, Google Scholar (Kousha and Thelwall 2009, 2011), and the potential of using a union library catalog to evaluate holding counts (Linmans 2010; Torres-Salinas and Moed 2009). With monographs, the holding count, or lib-citation has potential to serve as a new indicator of ‘perceived cultural benefit’ (White et al. 2009; Zuccala and White 2015). This is a useful measure, particularly when citation counts to books are difficult to obtain, or have to be mined as non-sourced items from journal indices (see Hammarfelt 2011).

Now, with the introduction of the Thomson Reuters Book Citation Index (BKCI) (Adams and Testa 2011) we can look forward to new assessment opportunities. Torres-Salinas et al. (2014) and Gorraiz et al. (2013) have thoroughly examined this resource, and although both research teams convey a positive outlook, researchers are still warned about specific limitations. For instance, errors in citation counts imply that data accuracy is an issue for books. Conceptual problems need to be resolved concerning annual review volumes versus regular books, new or multiple monograph editions, and translated monographs (i.e., Should the latter two document types be recorded as separate entities?). Also, with an overemphasis on English language books, the BKCI is not as comprehensive as it could be. New studies based on this index risk providing insights that are relevant solely to an over-concentration of English-language publishers.

When a single database is considered inadequate or limited, one possibility is to retrieve publication and citation data from multiple resources and transfer the data to an alternative system, designed to facilitate interoperability [e.g., a Structured Query Language (SQL) relational database system]. The transfer of data and development of datasets is perhaps common within bibliometrics, yet many of the challenges associated with this practice are rarely emphasized. In this paper, we will give more attention to this issue, and present some of the difficulties that our research team encountered during a data matching and integration experiment carried out the University of Amsterdam, Center for Digital Humanities.

The aim of our experiment was to find a new approach to evaluating the impact and visibility of monographs, by amalgamating and linking bibliographic data extracted from three autonomous resources: Scopus, WorldCat.org and Goodreads. From Scopus, we obtained citation counts to monographs as they appeared as non-sourced items in the cited reference lists of journal articles. The WorldCat.org union library catalog was used to obtain publisher information, ISBNs for the cited monographs, and library holding counts. With Goodreads we used both the ISBNs extracted from WorldCat.org and the titles of the cited monographs to obtain public reader rating and review counts. Bibliometric studies related to our experiment have previously been published (Zuccala et al. 2014, 2015; Zuccala and White 2015); hence for the present paper a results section is excluded in order to focus exclusively on the data challenges.

System interoperability and the ‘utopian’ ideal for monographs

While the logical unification of autonomous data stores is referred to as data integration, the term interoperability is said to be the “magic word that (allows) heterogeneous systems to talk to each other and exchange information in a meaningful way” (Parent and Spaccapietra 2000). There are in fact two types of interoperability: (1) syntactic interoperability and (2) semantic interoperability, with the former serving as a pre-requisite for the latter. Syntactic interoperability begins with specified data formats that can allow two or more systems to communicate and exchange data; while semantic interoperability allows two systems not only to communicate, but to also automatically interpret data so that accurate and meaningful results are produced based on a common model of exchange.

Bibliometricians are familiar with the transfer of data files from one system to another, but this is not exactly how interoperability works. For instance, a file format from the Web of Science Citation Index, generally a text (.txt) file, can be exported and saved in a folder on a personal computer and imported to a software tool like VosViewer (Van Eck and Waltman 2010) for bibliometric mapping. In this case there is a one-directional transfer of data, since the VOSViewer system does not automatically communicate with the Web of Science system for the extraction of this data. The user has to extract the file and import it deliberately for the mapping exercise, and a reverse operation is also not possible: VOSViewer files are not used as input to the Web of Science Citation Index.

Interoperability, which is clearly more than file sharing, is relevant to bibliometrics, but in the absence of technical progress in this field, much can be learned from the broader field of Library and Information Science (LIS). Library and Information Science researchers have had a much longer history of focusing on metadata standards for the interoperability of digital libraries (e.g., Alemu et al. 2012; Alipour-Hafezi et al. 2010; Fox and Marchionini 1998; Godby et al. 2003; McDonough 2009; Suleman and Fox 2002). What bibliometricians might achieve with a similar protocol are systems that can exchange and interpret data for the development of new comprehensive sets of metric indicators. The drawback is that with all technical and semantic elements leading to interoperability, the most challenging aspect is the socio-political: “the need for individuals and groups with vested interests to attempt to understand all points of view and then agree” (Fox and Marchionini 1998, p. 30).

At present, database interoperability is merely a utopian ideal for the bibliometrician. However, if Scopus, WorldCat.org, and Goodreads were to become interoperable, the exchange of data between all three systems would allow researchers to determine how international library holding counts, citation counts, and public review ratings for monographs co-vary. More precisely, it would enable researchers to identify how books are perceived to be of cultural benefit, the extent to which they have achieved a measure of scholarly impact, and how visible they are amongst readers using social media. The difficult reality is that stakeholders of different bibliographic data systems have competing interests. Elsevier’s primary interest with Scopus is commercial, but WorldCat.org and Goodreads are public platforms. WorldCat.org is an interoperable union library of many international libraries. Goodreads, by comparison, is a privately owned company. As a unique social-networking platform, Goodreads is partnered with many different information providers (e.g., Google, Yahoo!, Amazon, Microsoft, EasyBib), and it is also now partnered with WorldCat.org. Public reviews from Goodreads are now available via links from the WorldCat.org catalog of book records (OCLC 2012).

In Table 1, we first present some brief information about the three autonomous data resources used in our data experiment. Sections 3–4 of our paper examines how information pertaining to a monograph is currently recorded in each system, how this affects the potential for data matching, and how record keeping might be improved for future data integration procedures.

The bibliometric reality: working with unstandardized data

To evaluate the citation impact of monographs, a citation index with complete metadata is needed, including citation counts from all potential bibliographic sources (i.e., articles, monographs, and book chapters). At the time of our experiment, we did not have access to the Thomson Reuter’s Book Citation Index, so we were limited to using a small dataset that was granted to us from the 2012 Elsevier Bibliometrics Research Program (http://ebrp.elsevier.com/).

The dataset for our experiment consisted of close to 6 million cited documents (n = 5,633,782) from the Scopus journal index. All of the cited documents appeared in 494 different history journals, 419 literary theory journals, and 110 journals that had been classified in both fields. The data also covered two distinctly requested time periods: (1) 1996–2000 and (2) 2007–2011. Our first procedure was to filter out all sourced documents from our list of cited references (i.e., journal articles with a Scopus ID), so that we would be left with reserved list of records without an internal Scopus ID: documents that were ‘potentially’ a book title.

To determine if each non-sourced Scopus title was a book, we had a computing specialist conduct an automated selection procedure based on the presence (or absence) of three criteria. The first criterion was that the title had to appear only once in the cited source_title column or appear in duplicate in both the cited source_title column as well as the cited article_title column from the Scopus dataset. The second criterion was that a volume number had to be absent (because it would have indicated a serial), and the third criterion was that the assigned Scopus document_type column (i.e., re = review; ar = article; cp = conference proceeding; le = letter) had to be either a null value or possess a book (bk) tag for the small number of book titles that had already been included in the early stages of the Scopus book index.

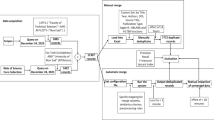

A total of 5,334,683 non-sourced ‘book’ titles were identified from the original set of 5,633,782 cited documents. The titles were then separated into a core dataset used for a matching procedure using both WorldCat.org and Goodreads. With Goodreads, our research focused specifically on titles that were cited in Scopus history journals between the years of 2007–2011 (Zuccala et al. 2014). Table 2 (below) lists the metadata tags used in the development of our interoperable database, and Fig. 1 presents an illustration of this database, comprised of linked tables. In Fig. 1, the most important links that support the interoperability of our autonomous datasets appear as ‘links’ between primary keys, but links are also present between specific table fields without a primary key. For example:

-

(A)

Table PUBLICATION_PUBLICATION has foreign-primary key constraints towards table PUBLICATICATION (one-to-many)

-

Publication_ID in PUBLICATION_PUBLICATION = ID in PUBLICATION

-

CitedPublication_ID in PUBLICATION_PUBLICATION = ID in PUBLICATION

-

This means that a specific published document can be identified and retrieved through an SQL query as a giver of a citation or as a receiver of a citation. Another example:

-

(B)

Table SOURCE has foreign-primary key constraints towards table PUBLISHER

-

Publisher_ID in SOURCE = ID in PUBLISHER

-

In this case, there is another one-to-many link because one publisher may be linked to many different books. In the Table SOURCE all book titles were given their own ID to identify them separately from journals, given that journals could already be identified according to their SCOPUS_JID.

Citation counts to non-sourced book titles in Scopus

Collecting citation counts to book titles from the Scopus journal index is problematic. This problem is shown in Table 3, where we can see multiple cited variations of the title The Past Within Us:

-

1.

The Past Within Us/The Past within Us (excluding a subtitle in rows 1–6).

-

2.

The Past Within Us: An Empirical Approach to Philosophy of History

-

3.

The Past within Us: An Empirical Approach to Philosophy of History

-

4.

The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History

-

5.

The Past within Us: Media, Memory, History

-

6.

The Past within Us: Media, History, and Memory

Since the full set of over five million ‘book’ titles (including author names and publication dates) was too difficult to standardize (i.e., we did not have the time or the resources to complete a full standardization procedure), the simplest approach to working with title variations was to aggregate those based on conclusive similarities. An SQL query command was used therefore to generate an initial register of citation counts (CITE_COUNT) by combining all repeated CITEDPUBLICATION_IDs. Note from Table 3, that the same CITEDPUBLICATION_ID’s for rows 8 and 9, as well as rows 11–17 resulted in aggregate citation counts of 2 and 7 respectively.

Matching Scopus book titles with titles held in WorldCat.org

To enhance our new database (Fig. 1) we collected further information for each book title using an Application Programming Interface (API) with WorldCat.org. The API query enabled us to match specific titles recorded in Scopus with the same corresponding title held in WorldCat.org. For each successful match we extracted an Online Computer Library Center accession number (OCLCID), a publisher name (NAME), place of publication (LOCATION) and International Standard Book Number (ISBN).

Author names were sometimes used in the matching procedure, but queries using author names do not work very well—i.e., they have the same problem as titles with regards to misspellings, abbreviations, standards, etc.—because a small error from a very short text string almost always resulted in a non-match. An initial query was carried out using titles only, but if there was a noted ambiguity related to titles that were highly similar, a second refined query was conducted including author names.

Table 4 (below) presents a revised count of citations for all title variations of The Past Within Us based on amalgamated OCLCIDs and ISBNs. Note that row 1 indicates a matching error with WorldCat.org (The Past Within Us: Media, History, and Memory does not exist as a real title), while rows 2, 6, and 7 contain inconclusive data. At row 6 the OCLCID is not associated with the correct PUBYEAR and at row 7 the absence of a publication year (PUBYEAR) fails to confirm which of the two listed title options is correct. If any part of the API query resulted in an unsuccessful or inconclusive match we excluded the record from our bibliometric analysis. Table 5 shows the final aggregate citation counts for The Past within Us: An Empirical Approach to Philosophy of History and for The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History.

WorldCat.org International Library Accession Numbers (OCLCIDs)

The API title-matching query with WorldCat.org supported the retrieval of only one OCLC accession number (OCLCID) per book title. This was problematic because each OCLC accession number is linked to a different edition of the same book, including a distinct library holding count for every edition. Note from Table 6 that for The Past within Us: Media, Memory, History the count of all citations from journal articles (CITE_COUNT) was matched to only one accession number (OCLCID) as a result of the API, even though WorldCat.org presents a total of nine accession numbers for the same book. The library holding count (LIB_CITE) was highest for the OCLCID = 56404917, yet in failing to retrieve all accession numbers with the API, there was a loss of holding counts attached to eight more print editions.

Matching titles and ISBNs with titles in Goodreads

The API query conducted with Goodreads was more precise than the procedure used for WorldCat.org, since it was possible to use both the ISBNs (extracted from WorldCat) and title strings (from Scopus). Table 7 indicates the total count of citations (CITE_COUNT) from Scopus, the lib-citation count (LIB_CITE) from WorldCat.org, and the average reader ratings, ratings count, and reviews count (Avg_rating; Ratings_count; Reviews_Count) from Goodreads for The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History. For this particular book, only ONE edition was recorded in Goodreads, but like WorldCat.org, multiple editions can be registered (see Fig. 2). In contrast to WorldCat.org, Goodreads does not present distinct ratings or reviews per book edition. Every monograph is treated similar to a citation in that it is the general ‘work’ itself that receives public attention and not the precise edition.

Overview of Scopus, WorldCat.org, and Goodreads data matching

Figure 3 illustrates the full process that was used to obtain a useful dataset, first by identifying all ‘book’ titles in Scopus, then using an API query for matching titles in WorldCat.org, and then matching a small selection of book titles that had been registered in Goodreads (see Zuccala et al. 2015).

At the later stages of data collection it was easiest to manage further duplicates and/or errors that were previously undetected (see Fig. 3). For instance, some of the title matches in WorldCat.org were not to scholarly books, but to other ‘monograph-like’ records, such as novels, dictionaries, manuals, or editions of the bible. Since these records were easier to recognize in a smaller dataset, we used a combination of manual and automated data cleaning. In the data refinement stage, the Dewey Decimal Classification scheme (History and Geography = 900) was particularly useful for obtaining a distinct list of cited monographs published specifically in the field of History. Historians cite many different books in their research articles, even books from outside their research field, thus isolating a particular non-sourced subset (e.g., a scholarly monograph versus a historical novel versus an archive document) would not have been possible without the use of additional metadata tags (i.e., classifications) resulting from matches in WorldCat.org.

Concluding discussion

Data standardization is an aspect of bibliometrics that assists with the development of new performance indicators. It helps to ensure that statistical indicators can be computed accurately and done so in a stable way over time. Studies pertaining to books are still at an experimental stage, because bibliographic datasets either possess relatively inconsistent standards for record-keeping (as in the case of Scopus or Thomson Reuters), or currently employ metadata standards for a unique purpose (i.e., for cataloging in WorldCat.org). In the case of monographs, we are trying to improve our understanding of scholarly impact and cultural or public visibility; hence it is necessary to identify datasets that work together to confirm this broad picture; if not in an ‘interoperable’ capacity, then at least in an integrated capacity using an alternative data management system.

A few points of discussion arise from our unique data matching and integration experiment. The first relates to metadata standards for cataloging monographs in LIS, where books are recorded as distinct items if re-printed in different formats (e.g., e-book or print) or re-published as different editions. For bibliometricians this raises the question of whether or not different formats and/or editions should or should not also be counted as distinctly cited items. The dilemma rests with the way that librarians view monographs versus how they are viewed by citing authors: “by using authors’ references in compiling [a] citation index, we are in reality using an army of indexers, for every time an author makes a reference he is in effect indexing that work from his point of view” (Garfield 1955, p. 110).

Librarians catalog books according to machine-readable cataloging (MARC) standards. Scholarly authors, on the other hand, may choose a specific style for referencing a monograph (e.g., American Psychological Association manual of style), yet there is still no international ‘standard’ for translating a reference into a metadata record for a citation index. Metadata standards for recording journal article references also do not exist in citation indexes, but articles are rarely re-printed like a monograph, so it is fair to ask the following: Does a newly published edition of a monograph possess revised elements that make its content different from the original printed version, or is it essentially the same as the previous one?

If a specific book is printed once, it is given an International Standard Book Number (10-digit and/or 13-digit). If the same title is re-printed by the same publisher it will usually possess the same ISBN. In our study of “The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History” Table 5 indeed shows that multiple re-prints of this monograph, collected and held by different libraries, have all been recorded with the same ISBN. Note; however, that a re-print by the same publisher is not categorically similar to what we mean when we say that a book is published as a new edition. If the same book is published as a new edition, it may have been printed and distributed by a different publisher. In this case, it will definitely have a different ISBN. When the book is published by a different publisher and in a different language, again the ISBN is unique, but we can also say that it possesses a revised element pertaining to content. Many books that have been translated to another language are presented with a revised title. A useful example is the monograph published by Bod (2012), which appeared first in Dutch as De vergeten wetenschappen (The Forgotten Sciences): Een geschiedenis van de humaniora by Uitgeverij and later by Oxford University Press with a new English title: A new History of the humanities. The search for principles and patterns from antiquity to the present (Bod 2013). How much of Bod’s history of the Humanities as the “Forgotten Sciences” is different to the reader of Dutch versus those reading his book in English? This we have not established, but it does encourage us to think more about how much ‘sameness’ is required when evaluating a monograph’s scholarly and public performance.

Currently, Thomson Reuters Book Citation Index (BKCI) and Scopus both now include an ISBN in their sourced book records. This ‘standard number’ does not serve as an accurate or useful identifier because it is not possible to know for certain if the indexed book with only one ISBN is the edition that different scholars have chosen to cite and reference. We simply cannot say that one designated ISBN matters when computing a book’s performance, particularly at the level of the citation. For many new journal articles we now have a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), which can help with the one-to-many relationship (i.e., one DOI aligns with different formats of the same article). A book can also have a DOI, but only if it is published as a digital object. Moreover, the DOI format for a book is sometimes derived from what is called the ISBN-A, or ‘actionable’ ISBN which adds a part of the ISBN to the book’s DOI (DOI Factsheet 2015). Linking a DOI to the ISBN-A seems to compound the problem of ISBNs in general; hence we suggest that scholarly books might be registered with a more specialized identifier called a “BOI”. The standard for the BOI could be that if the book is re-printed in different editions (i.e., with different publishers and ISBNs) in the same language, it can still be recognized as ‘one object’ suitable for evaluation. The BOI would be the most useful way of linking information from different types of book databases or indexes.

Goodreads, in comparison to Scopus and WorldCat.org, is what we refer to as the ‘in-between’ database. Since 2012 it has been building a registry of books based on information that it receives from WorldCat.org; thus similar to the international union library catalog, the Goodreads alerts its users to multiple monograph editions. However, all reviews and ratings that a monograph receives from readers across many facets of the general public are linked to only one record of that monograph, and not to distinct editions. Here the view of a public reviewer is essentially the same as the citing author. Again a ‘BOI’ for the book would be a valuable addition to the Goodreads database, as well as Scopus and WorldCat.org because it would unite different editions printed in the same language as one ‘object’ for evaluation under one unique identifier.

References

Adams, J., & Testa, J. (2011). Thomson Reuters book citation index. In E. Noyons, P. Ngulube, & J. Leta (Eds.), The 13th conference of the international society for scientometrics and informetrics (Vol. I, pp. 13–18). Durban: ISSI, Leiden University and the University of Zululand.

Alemu, G., Stevens, B., & Ross, P. (2012). Towards a conceptual framework for user-driven semantic metadata interoperability in digital libraries: A social constructivist approach. New Library World, 113(1/2), 38–54.

Alipour-Hafezi, M., Ali Shiri, A. H., & Ghaebi, A. (2010). Interoperability models in digital libraries: an overview. The Electronic Library, 28(3), 438–452.

Archambault, E., Vignola-Gagne, E., Cote, G., Lariviere, V., & Gingras, Y. (2006). Benchmarking scientific output in the social sciences and humanities: The limits of existing databases. Scientometrics, 68, 329–342.

Bod, R. (2012). De vergeten wetenschappen: Een geschiedenis van de humaniora. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker.

Bod, R. (2013). A new history of the humanities. The search for principles and patterns from antiquity to the present. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

DOI Factsheet. (2015). DOI® system and the ISBN system. Retrieved December 1, 2015 from https://www.doi.org/factsheets/ISBN-A.html.

Fox, E. A., & Marchionini, G. (1998). Toward a worldwide digital library. Communications of the ACM, 41(4), 29–32.

Garfield, E. (1955). Citation indexes for science—new dimension in documentation through association of ideas. Science, 122, 108–111.

Godby, C. J., Smith, D. & Childress, E. (2003). Two paths to interoperable metadata. Paper presented at the 2003 Dublin Core conference DC-2003: Supporting Communities of Discourse and Practice—Metadata Research & Applications. Seattle, Washington (USA). Retrieved November 20, 2015 from http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2003/godby-dc2003.pdf.

Gorraiz, J., Purnell, P., & Glänzel, W. (2013). Opportunities and limitations of the book citation index. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(7), 1388–1398.

Hammarfelt, B. (2011). Interdisciplinarity and the intellectual base of literature studies: Citation analysis of highly cited monographs. Scientometrics, 86(3), 705–725.

Hicks, D. & Wang, J. (2009). Towards a bibliometric database for the social sciences and humanities. A European Scoping Project (Appendix 1 to Martin et al., 2010). Arizona: School of Public Policy, Georgia University of Technology.

Kousha, K., & Thelwall, M. (2009). Google book citation for assessing invisible impact? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(8), 1537–1549.

Kousha, K., & Thelwall, M. (2011). Assessing the citation impact of books: The role of Google Books, Google Scholar, and Scopus. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(11), 2147–2164.

Linmans, A. J. M. (2010). Why with bibliometrics the humanities does not need to be the weakest link. Indicators for research evaluation based on citations, library holdings, and productivity measures. Scientometrics, 83(2), 337–354.

Martin, B., Tang, P., Morgan, M., Glänzel, W., Hornbostel, S., Lauer, G., et al. (2010). “Towards a bibliometric database for the social sciences and humanities—A European scoping project” a report produced for DFG, ESRC, AHRC, NWO, ANR and ESF. Sussex: Science and Technology Policy Research Unit.

McDonough, J. (2009). XML, interoperability and the social construction of mark-up languages: the library example, Digital Libraries Quarterly, 3(3). Retrieved October 28, 2015 from http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/3/000064/000064.html.

Moed, H. F., Linmans, J., Nederhof, A., Zuccala, A., López Illescas, C., & Moya Anegón, F. (2009). Options for a comprehensive database of research outputs in social sciences and humanities (Version 6, 2009). http://www.dfg.de/download/pdf/foerderung/grundlagen_dfg_foerderung/informationen_fachwissenschaften/geisteswissenschaften/annex_2_en.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2015.

Nederhof, A. J. (2006). Bibliometric monitoring of research performance in the social sciences and the humanities: A review. Scientometrics, 66(1), 81–100.

OCLC. (2012). Goodreads and OCLC work together to provide greater visibility for public libraries online. https://www.oclc.org/news/announcements/2012/announcement44.en.html. Accessed Nov 11, 2015.

Ossenblok, T. L. B., Engels, T. C. E., & Sivertsen, G. (2012). The representation of the social sciences and humanities in the Web of Science—a comparison of publication patterns and incentive structures in Flanders and Norway (2005–9). Research Evaluation, 21(4), 280–290.

Parent, C. & Spaccapietra, S. (2000). In M. P. Papazolglou, S. Spaccapietra, Z. Tari (Eds.), Advances in object-oriented data modeling (pp. 1-31), Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Sivertsen, G., & Larsen, B. (2012). Comprehensive bibliographic coverage of the social sciences and humanities in a citation index: An empirical analysis of the potential. Scientometrics, 91(2), 567–575.

Suleman, H., & Fox, E. (2002). The open archives initiative. Journal of Library Administration, 35(1–2), 125–145.

Torres-Salinas, D., & Moed, H. F. (2009). Library catalog analysis as a tool in studies of social sciences and humanities: An exploratory study of published book titles in economics. Journal of Informetrics, 3(1), 9–26.

Torres-Salinas, D., Robinson-Garcia, N., Cabezas-Clavijo, A., & Jimenez-Contreras, E. (2014). Analyzing the citation characteristics of books: edited books, book series and publisher types in the Book Citation Index. Scientometrics, 98(3), 2113–2127.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538.

van Leeuwen, T. N. (2013). Bibliometric research evaluations, Web of Science and the social sciences and humanities: A problematic relationship? Bibliometrie-Praxis und Forschung, 2, 8-1–8-18.

White, H., Boell, S. K., Yu, H., Davis, M., Wilson, C. S., & Cole, F. T. H. (2009). Libcitations: a measure for comparative assessment of book publications in the humanities and social sciences. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(6), 1083–1096.

Zuccala, A. A., & White, H. D. (2015). Correlating libcitations and citations in the humanities with WorldCat.org and Scopus Data. In A. A. Salah, Y. Tonta, A. A. Akdag Salah, C. Sugimoto, & U. Al (Eds.), Proceedings of the 15th international society for scientometrics and informetrics (ISSI), Istanbul, Turkey, 29th June to 4th July, 2015 (pp. 305–316). Bogazici University.

Zuccala, A., Guns, R., Cornacchia, R., & Bod, R. (2014). Can we rank scholarly book publishers? A bibliometric experiment with the field of history. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 65(11), 2248–2260.

Zuccala, A. A., Verleysen, F., Cornacchia, R., & Engels, T. (2015). Altmetrics for the humanities: Comparing Goodreads reader ratings with citations to history books. Aslib Proceedings,. doi:10.1108/AJIM-11-2014-0152.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zuccala, A., Cornacchia, R. Data matching, integration, and interoperability for a metric assessment of monographs. Scientometrics 108, 465–484 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1911-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1911-8