Abstract

We focus on the relationship between internationalization choices and performance of Italian firms during the first period of the financial crisis (2007–2010). Making use of a new firm-level database, we build a six-class taxonomy of firms’ internationalization activities; then we estimate firms’ performance as a function of internationalization forms, also estimating propensity score and Heckman selection models in order to control for endogeneity and sample selection bias. Over the period 2007–2010, Italian firms moved (on average) towards more complex forms of internationalization. Empirical analysis finds that these upward changes are related with positive effects on firms’ (labour) productivity, also in a period characterized by the 2009 trade collapse. These findings put additional emphasis on the issue of the diversification of both products and markets as a goal to be pursued by firms, even in times of crisis, to remain competitive and make profits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Following the sharp fall in 2009, the recovery of international trade largely benefited those countries most ready to exploit opportunities provided by the external demand, in a framework where domestic demand was sluggish or decreasing. The issue of the faster growth of the firms characterized by an advanced degree of internationalization came up again lately, as competitiveness stood out as a key factor for the adjustment in the Euro area (Altomonte et al. 2012).

The aim of this paper is to investigate the relationship between Italian firms’ internationalization choices and their performance during the first phase of the financial crisis, characterized by the trade collapse and the consequent recovery. It follows that we refer to the literature regarding both (i) the relationship between firm’s performance and internationalization and (ii) the nature of the crisis and its impact on firm’s behaviour.

As for the first issue, the economic literature highlighted the existence of a positive relationship between competitiveness and the degree of internationalization at the firm level. Better firm’s performance, in term of productivity and profitability, is usually associated, on average, with more complex internationalization strategies (Altomonte et al. 2012). Moving towards most advanced forms of internationalization could therefore strengthen firm competitiveness and, ultimately, countries’ economic growth potential. This aspect seems further more relevant during a recession, when the domestic demand languishes.

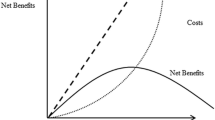

Competitiveness, performance and internationalization are strictly linked to firms’ productivity. On the theoretical ground, differences in firms productivity are at the heart of several models developed since the seminal work by Melitz (2003), according to which only more productive firms can cover the sunk costs required to profitably operate in the international markets (see Melitz and Ottaviano 2008; Chaney 2008; Bernard et al. 2011). On the empirical ground, several micro-econometric empirical studies focused on the determinants of efficiency differential between exporters and non-exporters. In their influential paper, Bernard and Jensen (1995) document a significant exporter productivity premium in US manufacturing industries. Moreover, the self-selection issue (foreign markets entry costs represent a barrier that less productive firms are not able to overcome), the learning-by-exporting hypothesis (knowledge flows from international buyers and competitors help to improve the post-entry performance of exporters) and the relationship between importing and productivity have been widely investigated (Castellani et al. 2010; Altomonte and Békés 2010; Muuls and Pisu 2009).

Common findings from this literature are the following. First, two-way traders (firms that both export and import) are the most productive type of internationalized firms, followed by only importers and exporters (namely one-way traders), while firms operating only in the domestic market come last (see Wagner 2012 for a detailed survey). In some cases, the availability of firm-level data on foreign direct investment allows for the inclusion of multinational firms as a more complex category of internationalization (i.e. firms that have a foreign participation or that are controlled by a foreign owner, see Altomonte et al. 2012). This latter group is usually at the top of the productivity ranking. Second, an evidence of self-selection seems to emerge: only the firms showing higher productivity levels in the years before starting to export can afford fixed entry costs of selling abroad. Third, firms of different countries show common features as regards their structural characteristics: internationally active firms are usually bigger (in terms of number of employees), show higher turnovers, larger capital stock and sell a wider range of goods with respect to both domestic firms and enterprises which adopt less complex form of internationalization.

As for the second issue, the 2007 financial crisis had important consequences on firms export performance and their internationalization strategies. The crisis, originated in the US sub-prime mortgage lending market, rapidly spread from the USA to the rest of the world via financial markets, hitting the EU hard in mid-September 2008, after the Lehman Brothers collapse. Access to capital was limited, and the survival of many banks became uncertain and the equity markets tumbled. As a result, bank loans to business shrank, and the contagion spread to the real economy, which was severely affected. Trade financing dried up, and export volumes fell by almost 15 per cent over the subsequent two quarters, an unprecedented downturn in EU. Consumer confidence fell to record lows in the Eurozone and households held back on discretionary spending. Monetary and fiscal policies became supportive. As financial stress abated and the expansive economic policies filtered through, business activity slowly responded during the second part of 2009 and the Eurozone economic growth for 2010 experienced an expansion of 2 %, after the collapse of 2009 (−4.5 %).

Both lack of demand and credit shock affected trade flows and impacted on firms internationalization activities. Some studies argue that credit shocks were responsible for a significant fraction of the decrease in trade flows in 2008–2009 (Chor and Manova 2012; Paravisini et al. 2011), while other studies find that the trade collapse was largely due to demand factors (Eaton et al. 2011; Levchenko et al. 2010).

The post-Lehman trade collapse largely inspired the literature on financial shocks and trade, especially in the context of models with heterogeneous firms with credit constraints (Chaney 2005; Greenaway et al. 2007; Muuls 2008; Bellone et al. 2010; Manova 2013; Minetti and Zhu 2011). Exporters are more vulnerable to financial market shocks than domestic producers (Amiti and Weinstein 2011; Feenstra et al. 2014). Shocks originating from the bank lending channel are potentially relevant for firms’ trade activity. In particular, studies using firm-level data find that during the crisis, larger declines (in terms of trade, sales or their ratio) have been experienced by more financially vulnerable exporters (Bricongne et al. 2012; Coulibaly et al. 2011; Egger and Kesina 2014).

A growing number of empirical papers looked at the links between financial constraints and export activities using firm-level data. Studies that deal with the direction of this link usually report that less constrained firms self-select into exporting, but that exporting does not improve financial health of firms (for a recent survey see Wagner 2014).

Our paper concerns the Italian firms. Italy is an interesting case to study: it is an export-oriented economy, with a strong manufacturing base and close trade integration with several countries. It is characterized by a large number of manufacturing exporting firms (nearly 200.000 in 2013) with a low average size (in 2013, exporting firms employing <20 employees were around 72 %). However, exporters account for a large share of value added of the Italian business system (82 % in 2013). Moreover, Italian financial system is largely bank-driven. Distortions in credit supply may therefore have a more sizable impact on trade in comparison to other countries.

As for the relationship between firm internationalization and performance, empirical evidence for Italy seems to confirm the results found for other countries. On the one hand, exporting firms are generally larger, more productive, more innovative. They show higher profitability, and they are more capital-intensive than non-exporters and pay higher wages; on the other hand, firms involved in more “complex” forms of internationalization (e.g. offshoring, exporting on a global scale) are in general more efficient than firms involved in “simple” forms (e.g. exporting without importing or vice versa). The formers are characterized, on average, by a higher propensity to R&D and innovation, they tend to adopt better management practices, they are more likely to hire skilled workers, and they have the financial strength to invest in capital and new technologies (Castellani et al. 2010; Benfratello and Razzolini 2008).

Firm size is an important condition for operating in foreign markets. The role of size becomes increasingly important with the degree of sophistication of international activities, starting from exports, the simplest form, to commercial agreements, technical and production agreements and, finally, foreign direct investment (Bugamelli et al. 2000). Larger firms are usually more efficient and productive having, ceteris paribus, a higher propensity to R&D and innovation, tending to adopt better management practices and having easier access to capital markets to invest in new technologies (Amatori et al. 2011).

Finally, as for the years of financial crisis, there are recent researches comparing Italian firm results and business strategies in according to different modes of internationalization (Cristadoro and D’Aurizio 2015; Fabiani and Zevi 2014). Common evidence seems to emerge: after an initial downturn, firms operating on foreign markets have recovered more rapidly the higher was their degree of internationalization.

Cristadoro and D’Aurizio (2015) find that Italian MNEs, already in the first phase of the crisis, performed better even compared to both exporters and domestic firms in terms of profits, sales, employment. Fabiani and Zevi (2014) show that the limited but significant transition of firms towards a stronger presence on the international markets was associated with a better seal of the turnover and employment in the years after 2009, with faster growth in the average level of nominal wages (though at least partly explained by reduced employment in low skill occupations), with higher productivity and average spending on R&D. On the opposite, a significant share of firms has reduced its presence in foreign markets, both in the intensive and extensive margins, being facing the greatest difficulties. These results seem of great interest for the purpose of our work.

As for the role played by credit shock during the crisis, Del Prete and Federico (2014)’s main finding is that the credit shock faced by exporters in the aftermath of the Lehman Brothers’ collapse was mainly due to a diminished availability of ordinary loans rather than to specific constraints in trade finance. This might be related to the short-term and low-risk nature of export and import loans.

Although the relationship between internationalization forms and productivity of Italian firms has been widely analysed, our contribution to this strand of literature is twofold. Firstly, using rich micro-level information taken from several ISTAT databases, we are able to describe in a detailed way the different internationalization choices of Italian businesses. In particular, we use an innovative database resulting from the integration of both statistical surveys and administrative data. The dataset refers to two non-consecutive years (2007 and 2010), which corresponds to the periods, respectively, before and after the first hit of the global financial crisis. It includes observations for over 90,000 Italian internationalized companies. Using the wide range of information of this dataset, a detailed taxonomy of the modes of internationalization of the Italian firms is defined, according to their degree of engagement in external trade activities. The structural characteristics of firms belonging to each class are described; furthermore, the empirical analysis is devoted to infer the relationship between the adoption of a given internationalization form and firm’s performance, measured in terms of the dynamics of labour productivity (value added per employee).

Secondly, in analysing the behaviour of Italian internationalized firms during a phase characterized by the trade collapse, we are able to answer to the following questions: did the crisis affect the relationship between firms’ internationalization model and performance? Does the way Italian firms participate in the international competition changed during the first stage of the crisis? If so, how did it change? How these changes affected the firm performance between 2007 and 2010?

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the taxonomy of internationalization forms of Italian firms, their distribution across the internationalization strategies and their structural characteristics, the changes of internationalization modes during the crisis. The econometric strategy is presented in Sect. 3. Section 4 reports and comments the results of the estimates. Final remarks are in Sect. 5. A detailed description of the dataset is presented in the Appendix.

2 Italian firms and internationalization: some descriptive evidence

2.1 Taxonomy of internationalization of Italian firms

Following Altomonte et al. (2012), we provide a taxonomy of internationalization strategies of Italian firms consisting in six mutually exclusive classes, each indicating a different mode of operating in foreign markets. Five classes are related to the trade internationalization, and the other one is related to the internationalization of production.

Moving from the most complex form of international activity to the basic one, the first class (“MNE”) includes both Italian firms that have foreign subsidiaries and those controlled from abroad. In the second class (“global”), firms exporting to at least five extra-EU areas are considered. The third class includes firms that both import and export (“two-way traders”), while firms carrying on only import activity are included in the fourth class (“only importers”). The fifth class (“only exporter”) includes firms essentially exporting towards EU markets and/or up to four extra-EU areas (i.e. neither importing nor undertaking any kind of productive internationalization). Finally, the sixth class includes the so-called marginal exporters, namely the firms exporting less than 5 % of their overall turnover. As long as these latter are “only exporters”, they are barely distinguishable from domestic enterprises. Therefore, this group is considered as a proxy for domestic firms and included in the descriptive analysis for the sake of comparison. It will also be taken as a benchmark group in the econometric strategy.

For each year, every firm is assigned to a single class. If a firm has more than one characteristic among those selected for the assignment along the scale of internationalization, it is attributed to the higher class (e.g. if a firm is controlled from abroad, does not have any import activity and only exports towards EU Member States, then it is allocated to the “foreign control” class, rather than being included among “only exporters”).

On the basis of the taxonomy described above, in the next Section we analyse the relationship between participation in foreign markets and firm’s performance; moreover, we investigate the changes occurred in the internationalization strategies between 2007 and 2010.

2.2 Internationalization and firm’s performance during the crisis

Different forms of internationalization are related to different performance (Tables 1 and 2). In 2010, the internationalized firms in our sample are mostly “two-way traders” (32.9 %) and “only exporters” (24.4 %), while most advanced forms of internationalization account for a very limited share of firms: the enterprises controlled by a foreign owner and the Italian MNEs represent 3.4 % of the total. This group, however, shows a larger average size in terms of employees (208.1 on average), compared to the significantly lower average size (9.7 employees) of “only exporters”. Furthermore, the MNEs export a wider range of goods and serve on average a larger number of markets. It can also be noted that labour productivity—measured in terms of value added per employee—increases as we move from the simplest forms of internationalization to the most complex ones. By contrast, the share of export turnover—a proxy for the firm’s degree of openness to the international activity—is higher for the global firms than for MNEs. In 2010, firms characterized by a more complex forms of internationalization show a pronounced diversification of production, measured in terms of the number of exported goods. At the same time, these companies are neither the most profitable nor those with the greatest degree of openness in international trade. Finally, “marginal exporter” firms are more numerous (and slightly more productive) than “only exporters” ones and show a very limited participation in the international competition both in terms of the range of exported products (about 2) and average sectors (67 sectors at 2-digit NACE classification level) where each of them exports (less than 2 sectors).

The internationalization strategies of the Italian firms changed somewhat during the crisis. A first clue of these transformations can be assessed in terms of the movements between the internationalization classes as reported in the transition matrix (Table 3). Figures in the main diagonal indicates the number of firms remaining in the same internationalization class between 2007 and 2010, while the values above (below) this diagonal show the number of firms moving towards less (more) complex categories. In particular, more than 56,000 firms are present in the sample both in 2007 and in 2010. Of these, about 67 % do not change internationalization strategy between the 2 years.

The degree of persistence rises as we move towards the most advanced classes of the taxonomy. Furthermore, also the changes of status are significant: 19.3 % of the sample (around 11,000 firms) moved upwards between the 2 years, especially from the “only exporters” and “only importers” classes to “two-way traders” (about 1775 and 2998 units, respectively). On the contrary, about 7500 firms (13.3 % of the sample) shifted downwards, mostly from “global” to the “two-way trader” status.

Moreover, about 1600 firms changed their status from “marginal exporters” to “two-way traders”, and around 1200 shifted from “marginal exporters” to “only exporters”. It is to be noted, however, that for “marginal exporters” would be possible to become “two-way traders” just by starting importing, and to pass to the “only exporter” group just increasing their share of exports on total turnover to more than 5 %.

All in all, these evidences show that in the years of the Great Recession the Italian internationalized firms accounted for a positive “net movement” towards more complex forms of presence in international markets: this amounts to 6.0 percentage points (3.5 excluding marginal exporters) and is statistically significant at the 1 % confidence level.

For the small- and medium-sized firms, the “net movement” (except marginal exporters) is estimated to be equal to 3.6 percentage points (statistically significant at the 1 % significance level). Therefore, small and medium-sized firms appear well positioned in the scale of internationalization: a large number of companies of this type lie in the intermediate category of the two-way traders.Footnote 1 We also argue that a sub-sample of firms moved towards more complex forms of internationalization over the period 2007–2010 as an attempt to contain the effects of the crisis.

These findings may be considered as a first empirical insight on a positive relationship between the degree of participation in international trade and overall firm’s performance. Whether or not the upwards (downwards) shifts determined positive (negative) effects on firms’ performance is a matter to be addressed on an empirical ground.

3 Empirical analysis: econometric strategy

The aim of this section is to verify whether the shifts (or persistence) had an impact on firm performance, here measured in terms of firm labour productivity (value added per employee) growth. We deal with this issue firstly estimating an OLS model, and successively, “correcting” for possible endogeneity and self-selection bias, by applying both propensity score matching and Heckman correction procedures.

3.1 OLS

For each cell of Table 3, we estimate the following OLS model (1),

where i (i = 1…n) denotes the firm; Y i is the firm’s performance variable (the change in value added per employee at firm level between 2007 and 2010); X i is the (logarithm of) level of the dependent variable in 2007; Z ij (j = 1, … ,16) is a set of dummy variables indicating changes or persistence in firm’s internationalization form; W ik (k = 1, 2, 3) are dummy variables indicating, respectively, whether firm i-th is small, medium or large sized; Q ir (r = 1, 2, 3, 4) are dummy variables indicating the location of the firm by NUTS1 Region (North-West, North-East, Centre, South, respectively); K i is a proxy of firm credit constraint; R is (s = 1, … ,42) are industry-specific dummy variables (Nace.Rev.2, 2-digit).

The high reliance of Italian firms on bank credit supply may have played a sizable role on trade and firm performance in a period characterized by a credit shock like that experienced during 2008 crisis. Exporting firms activity can be differently affected by credit crisis depending on their exposure on bank credit and, more in general, on external financing. To take into account this issue, following Rajan and Zingales (1998) and Chor and Manova (2012), we build a proxy of firm credit constraint. The external financial dependence (Extfin) is measured as the fraction of total capital expenditure that is not financed by internal cash flows from operations; a proxy for firms’ long-term needs for external finance is defined as

where capexp is capital expenditures, cf is the cash flow, and s denotes the firm industrial sector (at 2-digit NACE level).Footnote 2 This variable measures the portion of capital expenditures not financed by internally generated cash. Higher values of this variable are related to higher financial external dependence.

Firm’s internationalization decisions are non-random, and the outcomes of choices not made are never observable. Therefore, this kind of analyses is typically affected by selection bias. There are two sources of possible bias. “Selection bias due to observables” arises from sample differences that researchers can observe but fail to control (like firm size and growth). “Selection bias due to unobservables”, in turn, arises from the unobservable and thus uncontrolled sample differences that affect firms’ decisions and their consequences. In both cases, OLS estimates are definitively biased. We apply two econometric tools developed in the literature to overcome this problem: the propensity score matching (PSM) method—to mitigate selection bias due to observables—and the Heckman inverse-Mills-ratio (IMR) method, to address selection bias due to unobservables.

In our case, we are interested in studying the export behaviour of Italian firms during the first phase of the crisis, characterized by exceptional events like world trade collapse and the drying up of financial flows. In this context, we can suppose that unobservable firm’s characteristics (e.g. firm management ability to cope with crisis, financial stability and structure, financing needs etc.), other than observable ones, could have affected the internationalization choices and the probability to switch across different form of selling abroad. For this reason, we present results from both PSM and Heckman procedures as a sensitivity check to verify the robustness of OLS results (sign, statistical significance, quantification and direction of bias correction), though we are especially interested in Heckman results.

3.2 PSM

Firstly, we apply the propensity score matching (PSM) procedure.Footnote 3 As it is well known, this technique allows comparing an observable outcome—in our case: the firm’s performance after its shift across the taxonomy—with a non-observable one—i.e. the performance of the same firm if it had not shifted—by approximating this latter with the performance of an appropriate counterfactual.

The PSM matches shifting firms (the so-called treated group) with non-shifting companion firms which, on the basis of its observable characteristics, had a similar ex-ante probability of switching, but eventually did not (the “control” group). This set of firms is the counterfactual, the performance of the shifting group we compare to, so as to eventually measure the “average treatment effect on the treated” (ATT), i.e. the difference in the performance for firms shifting across taxonomy, had they not shifted.

More formally, the ATT is defined as follows:

where Y(1) is the outcome of a shifting firm i given it shifted (it is “treated”); Y(0) is the outcome of i given it did not shift; D = {0, 1} is the decision of shifting (D = 1) or not shifting (D = 0).

Since the term E[Y(0)| D = 1] is unobserved, the PSM procedure approximates it by identifying the control group. The PSM estimator for ATT is often defined as the mean outcome difference of treated and control firms matched by PSM. In other words, the counterfactual outcome in Eq. (1) is proxied by the average outcome of control firms selected by PSM.

The propensity scores matching estimator can generally be written as:

where P(X) is the propensity score, which is the probability of being treated. In our case, the propensity score is given by the following probit model:

where Int ij is a dummy variable which takes value 1 in the case of firm transition between the classes of internationalization j, value 0 in the case of persistence in the same class j (j = 1, …, 5); VALADD i is the (logarithm of) the level of value added per employee in 2007; W ik (k = 1, 2, 3) are dummy variables indicating, respectively, whether firm i-th is small (1–49 employee), medium (50–249) or large sized (over 250); Q ir (r = 1, 2, 3, 4) are dummy variables indicating the location of the firm by NUTS1 Region (North-West, North-East, Centre, South/Islands, respectively); K i is a proxy of firm credit constraint; R is (s = 1,…, 42) are industry-specific dummy variables (Nace.Rev.2, 2-Digit).

3.3 Heckman selection model

Heckman (1979) proposes a two-stage approach to evaluating programs for which the treatment choices are binary, and the program outcomes depend on a linear combination of observable and unobservable factors. His approach is to estimate the choice model in the first stage and add a bias correction term in the second-stage regression. After further restricting unobservables to multivariate normal distributions, the bias correction variable is derived in the form of inverse Mills ratio (IMR).

The application of the Heckman approach is feasible as we extend our dataset to include the firm-level information concerning a specific sub-sample of exporting firms: those who were exporting in 2007, but were no longer observed as exporting firms in 2010. We denote those firms as “exiting” companies, and we assume they represent the share of internationalized firms which was not so resilient to the effects of international crisis so to exit from the international markets.

As a result, this sub-sample of enterprises is only observed in just 1 year of the 2 years of the considered time span and, specifically, in 2007 i.e. at the beginning of time interval. The sub-sample of exiting enterprises consists of about 20,500 firms, with an average size of 16 employees.

In both stages of the Heckman model, we have the same covariates in the choice model and the treatment outcome regression. However, in order to identify the model and perform the estimates, the Heckman sample selection model requires an exclusion restriction assumption, i.e. that the choice model (selection equation) includes at least one variable to be correlated with the probability of being selected (in our case: of being shifted along the taxonomy) but exogenous relative to the outcome variable. It is excluded from the outcome equation, so that the impact of the excluded variable on the outcome is restricted to be indirect through the selection equation. We use the (logarithm of) firm age at 2007 (Lage), expressed in terms of the number of years from its born (up to 2007), as additional exogenous variable in the selection equation.

Ceteris paribus, we assume that an older (younger) firm should have more probabilities to shift upward (downward) along internationalization modes because they are generally more (less) productive. This is mainly due to learning effects related to increases in the knowledge and know-how of an organization, to investment in research and development (leading to product or process innovations), to investment in human capital (attention for human resource management practices in general, and firm-provided training in particular, see Paauwe 2004).

In the first stage, we estimate the following probit model, similar to (5):

but with Lage as an additional regressor.

The second stage consists in carrying out an OLS regression similar to that in Eq. (1) but augmented with the inverse Mills ratio obtained from (6) as an additional explanatory variable to take account of the selection bias:

This equation needs to be explained a little more in detail. It says that the regression line for Y on X will be biased upward when ρ is positive and downward when ρ is negative, since the inverse Mills ratio is always positive. The size of the bias depends on the magnitude of the correlation, the relative variance of the disturbance σ, and the severity of the truncation.

4 Empirical analysis: results and comments

Regressors in Eq. (1) are generally statistically significant and show the expected sign. In particular, change in labour productivity between 2007 and 2010 is positively affected by its level in 2007 and negatively by higher financial external dependence.

The more interesting results (the effect of a shift or a persistence in a internationalization class on firm performance) are reported in Table 4, ordered by decreasing value of OLS coefficients (first column). All the estimates are expressed in terms of difference from the class of “marginal exporters”, taken as a benchmark. The following effects emerge. Firstly, upwards shifts are generally associated with positive and significant effects on performance: firms moving towards more advanced forms of internationalization increased their labour productivity. At the same time, downward shifts tend to be associated with a decrease in value added per employee. In general, among the results statistically significant, the larger is the shift across internationalization classes, the larger is the effect on performance, both for upward and downward moves.

It is worth noticing that firms that experienced a downgrade performed worse than the firms that during the same period remained “marginal exporters” (i.e. exported less than 5 % of their total turnover in both years). This can be explained looking at the dynamics of the Italian business cycle: between 2007 and 2010 exports shrank by 11.6 % (and in the same period imports decreased by 6 %), while domestic demand decreased much less (−3.2 %).Footnote 4 Therefore, the first part of the crisis hit more severely the firms more exposed to the international trade.

Secondly, the persistence in the same internationalization class between 2007 and 2010 is generally accompanied by a better performance in terms of labour productivity, except for the case of persistence in one of the least advanced form of international activity (“only exporter”). This is incidentally consistent with the fact that during the harsher years of the crisis, an upgrade of the internationalization mode was virtually a way for the firms to preserve their competitiveness.

However, as mentioned earlier, in this type of analyses the OLS estimates are inevitably biased and sensitive procedures are necessary in order to check and correct the selection bias. In this respect, the last two columns in Table 4 report the results of both PSM and Heckman estimates for the labour productivity changes associated to shifts across different internationalization models between 2007 and 2010.

PSM and Heckman estimates show that a self-selection problem does affect the relationships between the firm’s internationalization choice and its performance during the first phase of the financial crisis. However, due to the presence of bias derived from unobservable factors, the Heckman estimates are more suitable to capture the “true” effects associated to shifts across the internationalization forms.

As for the Heckman first stage estimates, Lage is always statistically significant and with expected sign: positive in the cases of upward shifts, negative in the case of downward shifts. According to the empirical evidence, in the case of an upgrade shift, unobservables in the selection model are positively correlated with the outcome variable, thus causing estimates to be biased upwards without controlling for self-selection. The reverse applies when enterprises shift downwards. In the majority of cases, the correlation coefficient takes the expected sign and is statistically significant. The significance of the effects revealed by OLS is always confirmed by Heckman estimates (except in the case of downward moves from “Global” to “Only exporters” status). The Heckman correction has also the expected direction, both for upgrades (the effect of upward shift across internationalization modes on firms’ performance is revised downward) and downgrades (the effect of downward shift across internationalization modes on firms’ performance is revised upward).

More in detail, the OLS estimates tend to overstate the effects of internationalization upgrades: in 2007 older firms—that generally show a better performance—had a higher probability to shifts towards more complex forms of internationalization. At the same time, a share of younger exporting firms—likely those somewhat weaker—left international markets as a consequence of the effects of international crisis. As those firms are not observed in 2010, OLS estimates are upward biased due to the fact that the sample of firms is selected towards surviving and more efficient enterprises. We control for this selection bias by considering the characteristics of “exiting” companies in 2010: as a consequence, the “true” effects of the upgrades on the firms performance in 2007–2010, as measured by the coefficients of the Heckman model, are lower. On the opposite, when downward shifts are considered across internationalization modes, the OLS estimates tend to underestimate the effects of the internationalization downgrades: in 2007 the younger (and weaker) firms had a higher probability of shifting downwards across the taxonomy. Also in this case, selection bias is controlled for the subsample of exiting firms. The estimated ρ parameter regarding those transitions is generally significant and negative, so that the “true” effects of the downgrades are revised upwards compared to OLS estimates.

However, the differences in magnitude of coefficients between OLS and Heckman estimates are very low, so revealing that the self-selection bias itself is statistically significant but quantitatively modest. A possible explanation for this relies on the exceptionality of the period considered: the 2008–2009 trade collapse, which followed the financial crisis, acted as a virtually exogenous shock for all firms operating internationally.

As far as the magnitude of the effects is concerned, the Heckman estimates confirm an important result: upward shifts foster firms’ performance and their effects are larger the longer are the “jumps” across the internationalization classes. The most remarkable contributes to the dynamics of firms’ productivity between 2007 and 2010 are due to the movements from “Only importer” to “MNE” (over 20 % on average with respect to “marginal exporters”), from “Two-way trader” to “Global (+18 %), and from “Global” to “MNE” (+17 %). On the contrary, shrinking one’s own degree of internationalization caused a decrease in the labour productivity, especially when a firm shifted from “Global” to “Only exporter” (−5 %), and from “Two-way trader” to “Only exporter” (−4 %).

It is also noteworthy that maintaining the internationalization form unchanged had a positive effect especially when the internationalization form is relatively “complex”, such as the persistence as a “MNE” (+12 % in value added per employee on average with respect to remaining “marginal exporter”), “Global” (+10 %) and “Two-way traders” (+10 %). Contrarily, firms that between 2007 and 2010 persisted in the “Only exporter” class experienced a −0.2 % fall in the dynamics of productivity with respect to the change in productivity of marginal exporters. In other terms, this choice led firms to perform even worse than the units whose activity remained basically confined in the domestic market.

4.1 Firm size effects

However, these effects could have been different for firms of different size. There is a relationship between firm size and internationalization activity (see Sect. 1). Empirical literature clearly showed that more complex forms of foreign activity are usually related to larger firm size; this stylised fact is confirmed also in the case of Italy (see Table 1). Furthermore, the average size is positively correlated to labour productivity: in 2010, smaller firms showed lower productivity by one-third compared to larger firms. Lastly, it is well known that Italian firms are characterized by a small size and the distribution of firm in our sample confirms this evidence (around 87 % of total firm are included in this class; see Table 5).

For all these reasons, we are interested in checking whether a gain (or a loss) of productivity due to a change of internationalization form has been different for firms of different size. To estimate this effect, the Heckman model (7) is augmented with the interaction between the variables Zij (dummy variables indicating changes or persistence in firm’s internalization form) and Wik (firm size dummy variables). Results are reported in Table 6.

First of all, it is worth noticing that smaller firms show slightly higher productivity gains than average effects reported in Table 4. This result can be due to the fact that smaller firms are usually less productive than larger firms: it follows that an upgrade in the internationalization forms is more effective for this class of firms, helping to bridge the gap with respect to larger firms.

Secondly, gains or losses in productivity due to change in internationalization modes are not statistically significant for medium and large firms in comparison to smaller firms. In the few cases where this difference is significant, it is found to be negative. In the case of larger firms, this occurs for the upgrade from “only importer” to “MNE”, and the downgrade from “MNE” to “Two-way traders”. Both these shifts probably involve corporate “events” (such as mergers, acquisitions and spin-offs) that might negatively affect firm’s productivity (for example, because of reorganization processes).

4.2 Regional heterogeneity

Due to the well-known remarkable heterogeneity that characterizes Italian macro-regions in terms of economic performance, the effects of the internationalization choices of the Italian firms may be different depending on the localization choices of the enterprise.Footnote 5 Indeed, the firms’ distribution and firm’s performance vary across Italian regions (Table 7): in 2010, internationalized units in North-Western and North-Eastern regions account for more than 70 % of overall firms in the sample, and they are more productive than firms located, respectively, in the Centre or South/Island. The labour productivity for firms located in the North-West is 35 % higher than for the South-located units. Firms in the North-West and in the Centre are denoted by larger average size (51.6 and 57.3 employees, respectively) and higher turnover relative to the firms located elsewhere.

In the light of such a geographical heterogeneity, it is relevant to assess whether the effect of the shifts in firms’ internationalization models reflects regional heterogeneity and changes depending on firms’ localization. To do so, the Heckman model (7) is augmented with the interaction between the dummy variables Z ij (indicating a change or a persistence in firm’s internalization form) and W ik (indicating the firm’s location). Results are reported in Table 8.

For almost all the considered transitions, firms located in the North-West of Italy show an effect on productivity slightly higher than the overall average.

Only in few cases, a significantly different effect for firms located in the other macro-regions is found: in all of them, the sign of the effect is negative and its magnitude is considerably higher for firms located in the South than in the Centre or North-East. It follows that the effects on productivity of internationalization choices have a geographical dimension, with a disadvantage for historically weaker Italian regions. In some of these cases, the lack of statistically significant overall effect (reported in Table 4) might hide the existence of noticeable local heterogeneity, like it occurs for the transitions from “global” to “only importer” or from “MNE” to “only exporter”.

5 Concluding remarks

This work lies in the wake of the recent empirical literature that studies the relationship between internationalization forms and firm’s performance. The analysis is carried out with a new database that covers the universe of Italian firms trading abroad; the observation period consists of two non-consecutive years (2007 and 2010), including the effects of the global financial crisis. Following the suggestions coming from literature, we present a taxonomy of classes of internationalization, ranging from the basic strategies (“marginal exporters” and “only exporters”) to the more complex forms (internationalization of production).

Descriptive analysis shows that firms featuring more complex form of internationalization present higher levels of productivity, as well as a more pronounced diversification of production measured in terms of the variety of exported goods. Indeed, the internationalization strategies of Italian firms changed during the period of the financial crisis in order to implement defensive strategies aimed at curbing the real effects of the recession. Over the period 2007–2010 firms changed their presence on foreign markets moving (on average) towards more complex forms of internationalization.

Econometric analyses confirm that these changes helped firms preserve their competitiveness during the harsher years of the crisis. Firms that moved upward along the modes of internationalization between 2007 and 2010 performed better (in terms of dynamics of labour productivity) than firms only focused on domestic market, also in a period characterized by a sharp fall of external demand. Also a persistence in the more complex internationalization classes has been accompanied by a better performance (except in the case of “only exporters” class) while downward shifts tend to be associated to a decrease in competitiveness. Overall, to be a “global” enterprise would increase the likelihood to remain competitive, make profits and survive even in times of crisis. These results seem strictly in line with the main findings of the empirical literature on the Italian case (e.g. Cristadoro and D’Aurizio 2015; Fabiani and Zevi 2014). Furthermore, our results confirm the negative role of credit shock during the period 2007–2010 and its negative impact on firms’ internationalization activities.

Due to the peculiarities of Italian economy, which is characterized by an overwhelming presence of small-sized enterprises and heterogeneity in firms’ performance across macro-regions, we also analyse how the overall effects of firms’ internationalization choices on productivity vary depending on both the size and localization of enterprises. Our results point out that the first part of the crisis did not impact in a very different way on firms’ productivity when firm size and localization are taken into account. However, in the crisis period, we find that the effect of international choices on labour productivity was slightly higher for the small-sized enterprises and the firms located in the North-Western regions.

Our analysis is limited to the first period of the financial crisis, characterized by trade collapse (Italian GDP dropped by −5.5 % in 2009) and the subsequent recovery. In subsequent years, however, Italy has experienced a new and unexpected recession (a “double dip”) triggered by the sovereign debt crisis, which led to 3 years of consecutive decline in GDP (from 2012 to 2014). The contraction in domestic demand and credit factors have affected even more deeply firms behaviour and performance. Furthermore, the employment levels, which in 2007–2010 were fairly stable, subsequently reduced when the prolonged recession undermined the confidence of households and businesses. All these elements can therefore have played an important role, in affecting the internationalization choices of Italian firms, which might be partially different with respect to the period analysed here. The dynamics of internationalization and its effects on post-2010 firm performance should therefore be the subject of further research once micro data will be available.

More in general, the issue of the potential growth of Italian firms associated with an increased degree of internationalization comes up again, especially in the current phase, as a crucial issue to the chances of recovery for Italian economy. The diversification of both products and markets, therefore, should be an objective to be pursued.

Notes

Net movements of small and medium sized firms along internationalization classes are tested as follows: firstly, we calculate the transition matrix of Table 3 for small and medium sized firms; then, we run two-sample test of the incidence of SMEs across internationalization forms. The empirical evidence shows that the transitions of SMEs between 2007 and 2010 are statistically significant in the case of two-way traders (as an increase) and only importer classes (as a decrease). Results are available on request.

Cash flow is defined as the sum of funds from operations, decreases in inventories, decreases in receivables, and increases in payables.

Moreover, according to the confidence indicators, on the one hand most entrepreneurs thought that the recession would be transitory, so that in the aftermath of the crisis most of them reacted by trying to maintain the current employment level, also using the instruments provided by the Italian labour law (e.g. the “Cassa Integrazione Guadagni”). On the other hand, households kept their consumption levels basically unchanged, also decreasing their saving rates. For a detailed analysis on these developments see ISTAT (2011).

In what follows, a caveat must be bore in mind: following the assumptions of the Italian business register, a firm is localized according to the region where it has its headquarters, even if some units (especially the larger-sized ones) may have plants located in several regions. Therefore, any consideration on the geographical effects of firms’ internationalization refers to the region where that firm has its headquarters.

The world market is divided into 11 areas: European Union 27; non-EU European countries, North Africa, other African countries, North America, Central and South America, Middle East, Central Asia, East Asia, Oceania, Other territories and destinations.

The number of products is computed according to the 8-digit code of the Combined Nomenclature (CN), the classification system adopted in the COE database.

References

Altomonte, C., Aquilante, T. & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2012). The triggers of competitiveness: The EFIGE cross-country report. Bruegel Blueprint n.17.

Altomonte, C. & Békés, G. (2010). Trade complexity and productivity. CeFiG Working Papers 12, September.

Amatori, F., Bugamelli, M. & Colli, A. (2011). Italian firms in history: Size, technology and entrepreneurship economic history. Working Papers n.13, October, Banca d’Italia.

Amiti M. & Weinstein D.E. (2011) Exports and Financial Shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Oxford University Press, 126(4), 1841–1877. DOI: 10.1093/qje/qjr033.

Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Schiavo, S. (2010). Financial constraints and firm export behaviour. The World Economy, 33(3), 347–373. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01259.x.

Benfratello, L. & Razzolini, T. (2008). Firm’s productivity and internationalisation choices: Evidence from a large sample of Italian firms. Development Studies Working Papers n. 236, Centro Luca D’Agliano.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (1995). Exporters, jobs and wages in U.S. manufacturing: 1976–1987. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Microeconomics, 1, 67–119. doi:10.2307/2534772.

Bernard, A. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2011). Multi-product firms and trade liberalization. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(3), 1271–1318. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr021.

Blundell, R. & Costa Dias M. (2002). Alternative approaches to evaluation in empirical microeconomics. Cemmap Working Paper 10/02.

Bricogne, J. C., Fontagne, L., Gaulier, G., & Taglioni, D. (2012). Firms and the global crisis: French exports in the turmoil. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 134–146. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.07.002.

Bugamelli, M., Cipollone, P., & Infante, L. (2000). L’internazionalizzazione delle imprese italiane negli anni ‘90. Rivista Italiana degli Economisti, SIE—Società Italiana degli Economisti, 5(3), 349–386.

Caliendo M. & Köpeinig S (2005) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. IZA Discussion Paper 1588.

Castellani, D., Serti, F., & Tomasi, C. (2010). Firms in international trade: Importers’ and exporters’ heterogeneity in the Italian manufacturing industry. The World Economy, 33(3), 424–457. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01262.x.

Chaney T. (2005). Liquidity constrained exporters, mimeo.

Chaney, T. (2008). Distorted gravity: The intensive and extensive margins of international trade. American Economic Review, 98, 1707–1721. doi:10.1257/aer.98.4.1707.

Chor, D., & Manova, K. (2012). Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 117–133. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.04.001.

Coulibaly, B., Sapriza, H., & Zlate, A. (2011). Trade credit and international trade during the 2008–09 global financial crisis (p. 1020). International Finance Discussion Papers: Federal Reserve Board, no.

Cristadoro, R. & D’Aurizio, L. (2015). Le caratteristiche principali dell’internazionalizzazione delle imprese italiane. Quaderni di economia e Finanza, n.261, Marzo, Banca d’Italia.

Del Prete S. & Federico S.(2014). Trade and Finance: is there more than just “trade finance”? Evidence from matched bank-firm data. Temi di Discussione Banca d’Italia, n.948, January.

Eaton J., Kortum S., Nieman B. & Romalis J. (2011). Trade and global recession. Working paper Research 196, National Bank of Belgium.

Egger, P., & Kesina, M. (2014). Financial constraints and intensive and extensive margins of firm exports: Panel data evidence from China. Review of Development Economics, 18(4), 625–639. doi:10.1111/rode.12107.

Fabiani, S. & Zevi, G. (2014). L’esposizione internazionale e l’evoluzione delle imprese manifatturiere italiane negli anni della crisi. Mimeo, Banca d’Italia.

Feenstra, R. C., Li, Z., & Yu, M. (2014). Exports and credit constraints under incomplete information: Theory and evidence from China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(4), 729–744. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00405.

Greenaway, D., Guariglia, A., & Kneller, R. (2007). Financial factors and exporting decisions. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 377–395. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.04.002.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161. doi:10.2307/1912352.

ISTAT (2011). Rapporto Annuale. Rome.

Levchenko, A., Lewis, L., & Tesar, L. (2010). The collapse of international trade during the 2008–2009 crisis. In search of the smoking gun. IMF. Economic Review, 58(2), 214–253. doi:10.1057/imfer.2010.11.

Manova, K. (2013). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms and international trade. The Review of Economic Studies, 80, 711–744. doi:10.1093/restud/rds036.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

Melitz, M. J., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2008). Market size, trade, and productivity. Review of Economic Studies, 75(1), 295–316. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937X.2007.00463.x.

Minetti, R., & Zhu, S. C. (2011). Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of International Economics, 83(2), 109–125. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2010.12.004.

Muuls M. (2008), Exporters and credit constraints. A firm-level approach, National Bank of Belgium Working Papers, no. 139.

Muuls, M., & Pisu, M. (2009). Imports and exports at the level of the firm: Evidence from Belgium. The World Economy, 32(5), 692–734. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01172.x.

Paauwe, J. (2004). HRM and performance; achieving long term viability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Paravisini D., Rappoport V., Schnabl P. & Wolfenzon D. (2011). Dissecting the effect of credit supply on trade: Evidence from matched credit-export data. NBER Working Paper No. 16975.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148, 235–267. doi:10.1007/s10290-011-0116-8.

Wagner, J. (2014). Credit constraint and export; A survey of empirical studies using firm-level data. Industrial and Corporate Changes, 23(6), 1477–1492. doi:10.1093/icc/dtu037.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Dataset description

Appendix: Dataset description

Our dataset is obtained through the integration of four firm-level datasets. The reference statistical source is given by the ISTAT structural business statistics surveys (SBS), providing information on firms’ structure (e.g. size, sectors, value of production, turnover, value added). Currently, they include all the companies with at least 100 employees (the so-called SCI survey) and a large “rotating” sample of firms with less than 100 employees (PMI). PMI datasets essentially includes the variables appearing in the firm’s income statement but not those from the balance sheet statement.

Firm-level trade data are drawn from custom trade statistics (COE). COE is a census type statistics (based on administrative data) and represents a harmonized source of data about imports, exports and trade balance. It collects information on firms operating in Italy and tracks the value and quantity of goods traded by Italian firms with both EU (intra-EU trade) and non-EU operators (extra-EU trade). Specifically, for each firm and time period, COE contains information on the value and the volume of goods traded (exported and imported) by each pair of product/destination market.

We manage this information as follows. First, origin/destination markets are grouped into 11 geographical areas.Footnote 6 Second, export/import flows by firm/destinations/origin are aggregated with respect to firm’s scope, so that only the information on the number of products by firm/destination/origin market is retained.Footnote 7 Overall, the revised structure of COE dataset is as follows: (i) firm-level exports/imports towards/from 11 specific destination/origin areas are available; (ii) the number of product exported is provided for each pair of firm/destination markets.

Information about multinational firms is provided by FATS database, that reports firm-level data on both the foreign-controlled enterprises operating in Italy (inward FATS statistics) and Italian non-resident foreign affiliates (outward FATS statistics). It is worth noticing that, merging FATS and COE datasets, we include in our dataset only multinational firms located within national boundaries, i.e., Italian firms with foreign affiliates and foreign-owned branch operating in Italy.

The firm-level matching of the information contained in the above statistical sources is achieved using the ISTAT Business Register (BR) that present a unique association between the ISTAT “company code” and firm’s VAT code.

The dataset used for the empirical analysis consists of matched firm-level information for two separate periods, 2007 and 2010, denoting, respectively, the beginning of the global financial crisis and a temporary recovery of the business cycle. For each year, it includes more than 90.000 statistical units. According to 2010 sample data, enterprises employed about 4.4 million workers and exported goods for about 293 billion of euros (over 85 % of total Italian exports).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, S., Pappalardo, C. & Vicarelli, C. Internationalization choices and Italian firm performance during the crisis. Small Bus Econ 48, 753–769 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9799-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9799-5