Abstract

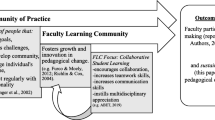

In this paper, I explain variation in the adoption of student-centred teaching practices among college faculty members in a program designed to promote K-20 instructional reform. I analyze data from a qualitative study of a Math and Science Partnership in order to understand why some faculty members had undergone extensive changes to their practices whereas others had not, even though both groups had demonstrated changes in their beliefs. Findings show that when collective identities focused on reform become more salient than the role identities associated with their teaching positions, faculty members are able to persist through the loss of self-efficacy that results from struggles with new student-centred practices. This study demonstrates how professional communities can enhance “collective efficacy”, thereby affecting whether the cognitive dissonance that accompanies professional development leads to instructional change rather than disengagement from reform initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, there have been numerous initiatives advocating reform in science and math education, many of which have focused on increasing the use of student-centred instructional practices such as inquiry or problem-based learning. Teachers’ use of inquiry approaches can enhance students’ ownership of knowledge (Siry 2013) and help students develop scientific explanations (Wu and Wu 2011). Yet overall, initiatives to increase inquiry-based instruction have had limited success (e.g. Van Driel et al. 2001). Understanding why instructional reform in science and math has not taken hold in many K-12 schools has been the focus of numerous research studies and theoretical papers (e.g. Roehrig and Luft 2004; Wallace and Kang 2004). However, considerably fewer studies have focused on college teaching reform. Yet in order to promote change in K-12 education, it is important that college professors also use student-centred practices in their classrooms, particularly when working with future K-12 teachers (Morrell et al. 2004).

College teaching tends to rely on lecture rather than student-centred approaches (Mulryan-Kyne 2010; Walczyk and Ramsey 2003). Kindfield and Singer-Gabella (2010) wrote, “undergraduate science courses typically immerse students in a flood of detail, offering little sense of the conceptual connections or lines of inquiry—much less the norms of practice—in which such details gain significance” (p. 59). The prevalence of lectures in math and science college courses has an influence on K-12 instruction, since how teachers are taught is a strong predictor of their practices (e.g. Battista 1994; Zeichner 1999). Because of this connection, some researchers have recommended changes in college instruction in order to emphasize the use of inquiry-based instruction and other student-centred approaches (Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research Universities 1998; Morrell et al. 2004).

While schools and universities differ in terms of the institutional factors that influence reform implementation, there are still many similarities in the processes of instructional change for both college faculty members and K-12 teachers. Some researchers have highlighted the necessity for both teachers and faculty to undergo some form of cognitive dissonance or doubt in order to provide the incentive for changing instructional practices (e.g. Gess-Newsome et al. 2003). Their arguments emphasize the importance of educatorsFootnote 1 questioning their own beliefs, as they experience discrepancies between their ideas about good teaching and student outcomes or between previously held ideas and new ideas. Educators then have the incentive to seek new ideas and enact instructional changes in order to reduce the discrepancies.

In this paper, I refer to this type of model for the process of instructional change as a “cognitive dissonance framework”. However, in the education research literature, there are many related terms, including “disequilibrium”, “doubt” (Wheatley 2002), “conceptual change” (Gess-Newsome et al. 2003), and “pedagogical discontentment” (Southerland et al. 2011). While these terms vary somewhat in their meaning and use, at a general level, they imply a process by which teachers come to view their current practices as inadequate through some type of dissonance-inducing experience.

These frameworks for teacher change have some explanatory power yet require elaboration in order to be both theoretically coherent and practically useful in planning for instructional reform. On a practical level, one issue is that there are numerous possible responses to cognitive dissonance, which include not only moving in the direction of reform efforts, but also avoiding new ideas, rationalizing current approaches or making surface changes that reduce dissonance (Festinger 1957). However, surface changes may not necessarily support reform initiatives. An approach to instructional change based on cognitive dissonance should be able to explain and predict this variation in outcomes. With an understanding of the variation, reformers would have more guidance in how to promote a “change” outcome of cognitive dissonance, rather than “avoidance” or “rationalization” outcomes.

On a more theoretical level, it is important to resolve some of the contradictory aspects of cognitive dissonance frameworks as they relate to teacher self-efficacy and education reform. One issue is that teacher self-efficacy has been shown to have a positive outcome on teacher and student performance (e.g. Midgley et al. 1989) and can support both motivation and persistence (Bandura 1995). Inducing cognitive dissonance in ways that reduce teachers’ self-efficacy could have a negative effect, as teachers might avoid implementing reforms due to lack of confidence in their ability to do so successfully (Zimmerman 2006). It takes confidence to undergo extensive changes in one’s practice. Yet teacher efficacy may not always be desirable, since if teachers feel too efficacious they may be unable to see flaws in their current approaches (Settlage et al. 2009; Wheatley 2002).

An understanding of the role of cognitive dissonance in education reform needs to account for this seeming discrepancy regarding the roles of both efficacy and doubt in contributing to effective teaching. On a practical level, reformers need to know if they should be promoting efficacy or doubt. If the answer is “it depends”, it is important to increase understanding of when teachers’ sense of their own efficacy should be cultivated, when teacher doubt should be encouraged, and the types of efficacy and doubt that would facilitate the desired outcome: teachers who are aware of the shortcomings of their current practices yet are also confident in their ability to enact reforms.

In this paper, I apply insights from identity theory and the sociology of emotions in order to elaborate on approaches to instructional change that draw from cognitive dissonance frameworks. In order to do so, I review how cognitive dissonance frameworks are used in the education research literature, with a focus on reform in college science teaching. I then discuss how insights from the sociology of emotions and identity theory can be used to further develop these frameworks. Next, I integrate ideas on cognitive dissonance and identity theory in order to analyze data from a study of instructional change among college faculty participating in a K-20 Math and Science Partnership.

Research Questions

In this study, I focus on the affordances and impediments to college-level instructional change by examining the participation of college professors who were recruited to work with a Math and Science Partnership (MSP). I investigate the following questions:

-

1.

What types of cognitive dissonance did faculty members experience through their MSP participation?

-

2.

What impact did this dissonance have on their beliefs and actions related to reform efforts?

-

3.

What accounts for differences between faculty members in their responses to dissonance and the extent of their instructional change efforts, both in their work with teachers and in their own college classrooms?

-

4.

How can efforts towards reform be more successful at promoting a change outcome of cognitive dissonance, rather than avoidance or rationalization outcomes?

Setting

The MSP program that is the focus of this paper began in 2005 with the goal of improving secondary mathematics and science education throughout the metropolitan area of an east coast city in the USA. Participants included secondary schools in 46 districts and science, mathematics, and education faculties of 13 colleges and universities. While there were 21 faculty members involved when I collected data on the project from 2005 to the 2007, this paper focuses on the experiences of 11 faculty members, eight in science and three in math. These 11 were chosen as focal faculty members for this paper because I observed each of them in a variety of interactions with teachers and they attended most of the MSP professional learning sessions. Therefore, the variation in the degree of change of these faculty members’ beliefs and practices could not be attributed to the extent of their MSP involvement, since all of them were deeply involved.

The participating faculty members varied both in types of institutions and experiences with the student-centred approaches advocated in science and math reform initiatives, ranging from one faculty member who has been using problem-based learning in her science classes for years to many others who described their prior practices as traditional or lecture-based.

In order to address the possibility of faculty members promoting traditional rather than student-centred practices in their work with K-12 teachers, part of the MSP program entailed having faculty members participate in learning communities with teachers and attend workshops on research-based instructional approaches. The hope was that the faculty members’ involvement in the MSP would not only help bring about reform in K-12 schools but would also have a positive impact on their college teaching.

The MSP adopted a facilitative “core connector” model in which it sought to build connections among participating individuals and institutions and support emerging efforts at collaboration. Disciplinary faculty member roles in secondary schools included presenting at in-service days for teachers, conducting week-long summer institutes, collaboratively designing high school courses with teachers, participating in disciplinary symposia during which teachers and faculty members discussed topics of mutual interest, and serving as resources during professional development sessions for teachers.

Previous Research

In this section, I discuss two areas of research literature: (1) self-efficacy and cognitive dissonance in education and (2) identity theory. These frameworks were chosen later in the study in order to illuminate initial patterns in the data that showed that the faculty members who exhibited a change response rather than an avoidance or rationalization response to cognitive dissonance were those who had greater confidence in their ability to implement reforms successfully despite their initial experiences with struggle and self-doubt. After recognizing this pattern, I explored literature on the relationship between confidence/efficacy and cognitive dissonance.

In the analysis of the data, the question remained as to why some faculty members seemed to have a strong sense of efficacy even as they experienced failures in their attempts to implement reforms. The second section of the review, which focuses on identity theory, emerged during the course of the study in response to patterns in the data that showed that faculty members who had developed identities as advocates for reform within their universities and had particularly strong social connections associated with reform efforts were able to cope with cognitive dissonance in ways that did not undermine their belief in their own efficacy. I therefore used this section of the literature review in order to integrate identity theory and the sociology of emotions with ideas of cognitive dissonance and self-efficacy in order to better understand the varied outcomes for faculty members regarding their commitment to reform.

Cognitive Dissonance vs. Self-Efficacy

An important question for reformers is how to promote change without undermining teachers’ self-efficacy. To gain an understanding of the relationship between “efficacy” and doubt, in this section, I explore research literature related to each of these concepts, particularly as they relate to reform in science education.

There has been a substantial body of research linking teacher self-efficacy to various positive outcomes, including student learning. According to Bandura (1995), self-efficacy can be described as “the belief in one’s abilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations” (p. 2). However, Wheatley (2002) argues that an overemphasis on efficacy is problematic since disequilibrium, which refers to the experience of student outcomes contradicting teachers’ beliefs and/or expectations, is an essential component in inducing changes in instructional practices. Without experiencing self-doubt, teachers will be satisfied with their current practices and disinclined to change.

Arguments such as Wheatley’s, which emphasize the importance of doubt in supporting instructional reform, can be broadly grouped under the category of cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance refers to the situation of holding contradictory ideas at the same time, which leads to a drive to reduce the dissonance through either changing ideas or behaviours, or engaging in a process of rationalization (Festinger 1957). In a broader sense, dissonance can exist not only between conflicting ideas, but also between one’s beliefs and actions.

While the term cognitive dissonance is not widespread in the science and math education reform literature, similar ideas, such as doubt (Wheatley 2002), have been applied to understanding the role of teacher beliefs and thinking in mediating change. For example, Spillane (1999) argues for the importance of teachers’ questioning their understandings of teaching, learning and content as a precursor to constructing alternative practices.

Studying reform at the college level, Gess-Newsome et al. (2003) emphasize the importance of unlearning prior knowledge and undergoing conceptual change to support successful engagement in reform efforts. Based on their findings, they argue that reform can only take place if there is change in the professors’ “personal practical theories” (Feldman 2000), which include images of teaching and learning, purposes of instruction, and ideas about teacher and student roles. Similar to Spillane’s (1999) argument, their argument emphasizes the importance of unlearning prior knowledge and undergoing conceptual change to support successful engagement in reform efforts. They argue for the importance of pedagogical dissatisfaction, which results when “one recognizes the mismatch between stated teaching beliefs, goals, instructional practices, and student learning outcomes” (p. 762). Similarly, Woodbury and Gess-Newsome (2002) have highlighted the importance of teacher uncertainty in leading to change.

Further supporting the importance of doubt, some researchers argue that too much self-efficacy prevents awareness of what needs to be changed in one’s own practices. For example, Korthagen (2004) discusses how not only overly negative self-concepts, but also overly positive self-concepts, can inhibit teachers from making changes. Settlage et al. (2009) found that when new teachers began their jobs with a strong sense of self-efficacy, rather than attending to the impact of their own race, class and gender, “their confidence blinded them to the self-doubt that might advance them professionally” (p. 199).

One potential criticism of cognitive dissonance theory is that it does not adequately account for the role of social context. The emphasis tends to be on an individual actor who works to resolve contradictions between different ways of thinking or between beliefs and direct experiences. As applied to education reform, actors may decide to make changes when their trusted pedagogical approaches do not lead to the desired learning outcomes in students or are in conflict with new beliefs. Yet decision-making is not only based on individual reflection, as it also has a strong social component.

There have been some studies in which researchers utilizing a cognitive dissonance framework have attended to the role of social context, emphasizing that change depends on the evolving conceptions and practices of the group (e.g. Coburn 2001; Spillane 1999). Coburn and Stein (2006) argue for the importance of teacher communities of practice (Wenger 2000), which entail joint enterprise, shared practices and negotiation of meaning that occurs when new initiatives are introduced. However, questions still remain regarding how exactly these social networks influence individual practice.

Another issue requiring further exploration is that the existence of a strong sense of teacher community does not necessarily support the interest of reform. For example, teachers could believe that changing their own practices might negatively impact their social relations with colleagues (Zimmerman 2006).

Overall, the question of whether professional development should cultivate doubt or efficacy among teachers is not yet resolved, since depending on the circumstances, either one can be useful for promoting effective teaching. Wheatley (2002) wrote, “At present, the best hypothesis may be that teacher efficacy faith and teacher efficacy doubt are both necessary, in unknown combinations, to move along the complex and uncertain path towards reformed teaching” (p. 19). In terms of future research, Wheatley continued, “Research is needed to explore the effects of teacher efficacy doubts on teacher development and reform in particular teaching contexts. Especially needed is examination of when such doubts are debilitating, and when they are energizing” (p. 20). In this paper, I engage in some theoretical work, grounded in an empirical study of college teacher change, in order to discuss how, why and when doubt can be at times debilitating and at times energizing.

One of the ways in which I approach this issue is by rethinking the dichotomy of efficacy/doubt as end goals for teachers and highlighting the role of community and social context. I argue that the main factors that drive reform (or lack of reform) are the following: (1) educators’ drive for solidarity with others in the workplace and (2) educators’ drive for a match-up between self-perceptions (identities) and situational meanings (participants’ experiences of events and the meanings they ascribe to these experiences). I describe how a framework based in identity theory can help illuminate when doubt can be productive for instructional reform and when it just serves to undermine efficacy without actually leading to positive change.

Identity Theory

Stryker and Burke (2000) describe identities as “parts of the self composed of the meanings that persons attach to the multiple roles they typically play in highly differentiated contemporary societies” (p. 284). For example, people who hold the identity of “faculty member” at a college might expect of themselves to be good teachers, competent researchers and experts in their field. Once recruited to work with a MSP, they might also hold new meanings associated with that role, such as serving as “content experts” for K-12 teachers, acting as an agent for reform and continually improving their own teaching.

Stryker (1968) describes how people’s actions are shaped by the drive to experience the positive emotions that occur when having their identities verified and to avoid contradictions between identities and self-relevant situational meanings. Inconsistency between self-perceptions and actual events leads to identity conflict and negative emotions. While people tend to choose actions in order to increase coherence with identity standards, identity standards can also change to increase coherence with actions, but this is a slower process.

In any situation, there are numerous identities that could be relevant in making decisions. While sometimes the actions associated with two particular identities cohere, other times they conflict. Stryker (1968) addresses the process by which people make choices regarding which identities to perform, describing how there is a “salience hierarchy” among identities. Salience depends on the quantity and strength of the relationships associated with that identity, which he terms “commitment”. Building on this idea, Lawler (2001) describes how “repetitive exchange among the same actors enhances their commitment to one another over time” (p. 142). Just as identities emerge through ongoing social interaction and shift depending on the setting (e.g. Carlone and Johnson 2007), salience hierarchies change over time as well.

The work of the sociologist Collins (2004) can help illuminate the micro-level processes by which commitment in Stryker’s (1968) conception (quantity and strength of relationships) leads to the salience of the associated identity. Collins argues that people choose groups with which to identify based on whether they have experienced solidarity-building interaction rituals (IRs) with this group. He describes IRs as characterized by bodily co-presence, a build-up of mutual focus, the development of a common mood, an “entrainment” or coordination of body movements and speech, shared experience between participants on both an emotional and cognitive level, and boundaries to outsiders. Outcomes are feelings of solidarity with the group and the symbols that are circulated.

Collins’ (2004) approach provides insight as to why conceptual change or cognitive dissonance is not sufficient to explain instructional reform without considering social context. His work suggests that regardless of the content of teacher meetings and the conceptual change that takes place within them, their effectiveness in contributing to reform depends on whether these meetings lead to positive emotional energy for the participants, who then are driven to seek future interactions with this group. In combining Stryker’s and Collins’ insights, the emotional attachment that comes from frequent, positive interactions leads to greater commitment for the associated identity, which in turn leads to that identity becoming more salient than others. If the identity is more salient, then it is more likely to inform choices of actions to take, such as whether to engage in the hard work of changing instructional practices.

Particularly strong emotions associated with participation in a community of practice may lead to group affiliations being emphasized rather than the individual identities that are associated with role expectations. Lawler (2001) writes that identities can be categorized as either “collective identities”, which entail identification with a group, or “role identities”, which are identities focused on the individual. He argues that collective identities develop when

“1) the interaction entails a joint task in which actors have difficulty separating or distinguishing their individual contributions or responsibilities for its success or failure; 2) the social interaction affirms actors’ self-efficacy entwined with collective efficacy; 3) the interaction generates positive or negative global feelings, and actors’ interpretations of these feelings generates specific emotions (e.g. pride and gratitude) directed at self and other. Overall, if actors interpret their individual emotions in terms of what they share or have in common, a collective identity becomes more salient” (p. 144).

One important aspect of collective identities is that actors perceive a jointness of task in which pride in self and gratitude to the other go together. If only the role identity is salient, the pride in self is strong, yet the gratitude towards the other is weak.

Methods

This qualitative study was designed to obtain an in-depth view of the role of faculty members’ experiences in the MSP program, including recruitment, training, placement and changes in beliefs and practices. As a researcher on the project, I attended professional learning sessions for faculty members and teachers, summer institutes for teachers, planning meetings, special events, in-service days, sessions in which faculty members and teachers worked together to develop K-12 curricula, disciplinary symposia and other MSP events in which faculty members and teachers interacted.

The methodology drew on Guba and Lincoln’s (1989) criteria for validity and authenticity in ethnographic research, which entail fairness, an emphasis on increasing understandings of others’ perspectives and working with participants towards positive change in local settings. Therefore, data from this project were continually used to help improve the MSP program for both the teacher and faculty member participants. Guba and Lincoln’s criteria also entail an iterative relationship between data and theory, which entails frameworks being chosen and developed based on patterns in the data.

From initial investigation of the third research question, there appeared to be a relationship between faculty members’ persistence through cognitive dissonance, their identities as reformers and the types of social interactions they had with other faculty members. I therefore applied ideas from identity theory (Stryker and Burke 2000), the salience hierarchies of identities (Lawler 2001) and interaction ritual theory (Collins 2004) in order to understand why dissonance and doubt led to a reform response for some faculty members, yet an avoidance response for others.

Data Sources

This paper focuses on the following data sources, though more were collected throughout the study:

-

1.

Interviews of the faculty members

-

2.

Videotapes of five professional development sessions in which faculty members worked with teachers

-

3.

Transcriptions of ten meetings between faculty members and MSP staff in which inquiry-based instruction and reform were among the issues discussed

-

4.

Field notes from four professional development sessions on student-centred instructional practices conducted by MSP staff for participating faculty members

-

5.

Field notes and transcriptions from five sessions of a seminar designed for faculty members and teachers with a focus on formative assessment

-

6.

Field notes from observations of eight sessions of summer institutes for teachers that were either conducted by faculty members or co-planned between a faculty member and high school teacher

-

7.

Field notes from five disciplinary symposia for faculty members and teachers, led by faculty members

-

8.

Email correspondence between participants

-

9.

Logs and journals from the faculty members in which they discussed their teaching practices and their experiences with MSP participation

-

10.

Results of an end-of-project survey in which faculty members were asked to rate their teaching practices on a traditional–reform continuum, rate their changes in beliefs and practices throughout their participation in the MSP, and describe the degree of collaboration with colleagues in their department and with other MSP faculty members

Data Analysis

In the initial examination of the data, I addressed the first question: “What types of cognitive dissonance did faculty members experience through MSP participation?” Dissonance and doubt can take many forms, and I coded for any expressions of self-questioning, discomfort and conflict as they participated in MSP projects, worked with teachers and attempted changes to their practices. In addition, I developed codes for the perceived causes of self-doubt, for example, whether the faculty members were expressing dissatisfaction with their own teaching practices or whether their dissatisfaction came from their interactions with teachers in the MSP program or with their own students. Data was coded using NVIVO software (QSR International 2006), which allows for the organization and analysis of qualitative data and linkages by theme, code and/or participant between data sources.

In order to address the question “What is the relationship between dissonance and faculty members’ beliefs and actions related to reform efforts?” I examined the connections between faculty members’ statements that expressed dissonance or self-doubt and their statements and actions related to their concerns. For example, if one faculty member said, “I want to do project-based instruction in my own classroom, but I cannot because my students do not like it and it does not fit with the subject matter”, I would look at his/her actions. Did the faculty member stop going to workshops on this topic and report that s/he was not using project-based instruction? This would suggest that the discrepancies between beliefs and experiences likely had an impact on their actions. However, if the faculty member expressed doubts about the reform working in their classroom and their ability to implement it yet went ahead and persisted with it, that would show that the dissonance had little effect on restraining their efforts towards increasing their use of these practices.

Information about the changes in faculty members’ practices over time came from a combination of self-report data and observations of their work with teachers as part of the MSP project. In these observations, logs and interviews, I coded the teaching practices reported and demonstrated, such as noting when they used lecture, discussion, experimentation or problem-based learning.

In terms of the third question, “What accounts for differences between faculty members in their responses to dissonance and the extent of their instructional change efforts?” I examined patterns regarding which faculty members persisted through dissonance-inducing experiences, changed their beliefs and implemented student-centred reforms in their teaching. Given the emerging importance of collective identity development, I investigated the role of social interaction and identity in mediating reactions to cognitive dissonance. I recoded the data based on constructs such as salience, commitment, emotional expression such as pride and gratitude, and identity conflict. I looked for pairs of pride/gratitude, which would indicate a collective identity as salient and shame/anger, which would indicate a stronger role identity (Lawler 2001).

I also examined participants’ affective responses to events and the circulating symbols associated with student-centred instruction, which provided insight into the levels of emotional energy associated with particular concepts. In analyzing videos of partnership-related events, I specifically focused on the micro-level of interactions in order to look for evidence of successful and unsuccessful interaction rituals, including an examination of dialogue, body language, gaze direction, rhythm of speaking, gestures and synchrony or asynchrony in movements and facial expressions. By slowing videos to the tenth of a second, I observed when teacher and faculty members’ movements and gaze direction became coordinated, which provides evidence of the development of mutual focus and common rhythm. By transcribing and analyzing some of the dialogue, I examined patterns involving whether talk was characterized by overlap, pauses, interruptions, changes in volume, participants finishing each other’s sentences and synchronous or asynchronous timing between the ending of one participant’s utterance and the beginning of another’s. Although coordination and anticipation of others’ movements and utterances provide evidence of the build-up of entrainment and solidarity, lack of coordination, such as pauses, hesitation and asynchronous movement, suggests a lack of entrainment.

I triangulated observations of synchrony with participants’ statements in transcripts and interviews that addressed whether group cohesion was emphasized or whether there was a lack of cohesion. For example, when observations of synchrony in vocalizations and body language from video analysis were accompanied by statements in interviews such as “I felt we were working together as team”, this provided evidence that there was a build-up of entrainment and solidarity that took place during that event, since the self-reports cohered with the observations of synchrony.

In discussing the results, I draw on interviews that are illustrative of patterns that occurred throughout the data. In the next section, I describe the categories of faculty responses that emerged. I develop an explanation rooted in identity theory that shows how aspects of the social structure, in particular professional community, influenced the different outcomes for participating faculty members regarding instructional change.

Results

Types of Cognitive Dissonance

-

1.

What types of cognitive dissonance did faculty members experience through MSP participation?

For many of the faculty members, cognitive dissonance arose when they contemplated or began replacing traditional lecture-based approaches with student-centred practices in their classrooms. All but the few faculty members who were already active in reform efforts experienced the following types of dissonance:

Student-Centred Practices Were Superior to Current Traditional Approaches

A common theme in interviews was that attending MSP professional development experiences led faculty participants to believe that the student-centred practices were superior to approaches that entailed mostly lectures or lectures with some labs. This can be seen as a conflict between their emerging beliefs about teaching and aspects of their current practices. In order to resolve this type of dissonance, faculty members could either reject the new beliefs in favour of current practices or work to bring their practices into greater alignment with these new beliefs.

Students and/or Colleagues Did Not Respond Positively to Their Reform Efforts

This type of cognitive dissonance occurred when faculty members began to implement student-centred practices into their teaching but struggled considerably. For example, one of the faculty members, Troy, reported: “This problem-solving approach is a good idea but is not working for me”. Another faculty member, Michael, stated: “I like it in theory but my students just want to be told the answer”. In these cases, faculty members experienced a conflict between their beliefs about the benefits of the reforms and their actual experiences of failure when trying to implement the reforms. Reframed as identity conflict, they experienced a contradiction between their view of themselves as reform advocates and their view of themselves as competent professors. This type of dissonance has the potential to lead to an avoidance response if faculty members prioritize maintaining the “competent professor” identity. In order to lead to instructional changes, faculty members would need to instead persist through these negative experiences in their classrooms and eventually develop the skills that would facilitate success with teaching approaches that are more student-centred.

Interestingly, expressions of dissonance and doubt seemed to be present for almost all of the participants. Rather than variation in the expressions of dissonance, there was more variation in their subsequent actions. The next section focuses on why some faculty members began avoiding changes, whereas others persisted.

Effects of Cognitive Dissonance on Reform Efforts

-

2.

What impact did this dissonance have on their beliefs and actions towards reform efforts?

-

3.

What accounts for differences between faculty members in their response to dissonance and the extent of their instructional change efforts both in their work with teachers and in their own college-level classrooms?

Throughout their participation in the MSP, many of the faculty members’ beliefs began to show greater coherence with the research-based best practices advocated in the workshops. However, there was considerable variation in the extent to which faculty members demonstrated these practices both in their work with teachers and, based on self-report, in their own college classrooms.

A conceptual change framework alone was not adequate in explaining the faculty members’ different degrees of reform implementation. For example, while many faculty members demonstrated conceptual change in their interviews and comments during meetings, some of these science and math faculty members subsequently changed their practices, whereas others did not change much. Of the latter group, some described how they attempted to implement changes but were not successful. Others reduced their participation in the MSP program altogether. Still others described themselves as having changed their ideas about best practices towards a more student-centred approach yet, when observed interacting with teachers, continued to model traditional rather than student-centred reform approaches.

In analyzing the qualitative data using identity theory, it became apparent that cognitive dissonance in various forms contributed to identity conflicts for most of the faculty members. These conflicts remained problematic for some faculty members’ sense of efficacy, in that they did not believe that they could implement instructional reform successfully. However, the identity conflicts became less important for others. What differed in the experiences of these faculty members is whether the identity conflicts that arose throughout their partnership work were mitigated by the development of collective identities focused on reform.

In this next section, I briefly describe the categories of faculty members’ responses to cognitive dissonance and identity conflict. These categories emerged from coding the interview, journal and survey data. I created data matrices (Miles and Huberman 1994) that listed each of the faculty members, statements that they made about reforms, statements about their own teaching, statements that suggested doubt or some form of cognitive dissonance, survey responses and notes on their teaching and interactions with K-12 teachers. The categories emerged from grouping faculty members based on similarities in their initial practices, the degree of changes they made in their practices and their expressions of cognitive dissonance and identity conflict. After creating these categories, I examined the data for factors that might have led to similarities in their reactions, which led to a focus on the role of the reform-oriented communities in which they participated.

Categories of Faculty Member Response

Reformer

For the very few faculty members in this category, identity conflict was less than for the other faculty members. Research-based student-centred practices were consistent with prior beliefs about teaching, and involvement with the MSP supported further changes in their practice. For example, one of the faculty members, Nora, already used inquiry-based approaches in her classroom before starting her work with the MSP. However, the MSP did have an impact on her teaching, as she began to incorporate formative assessment techniques and became more active in sharing her knowledge with colleagues and teachers.

Another faculty member in this category, Daniel, rated changes in his practices due to the MSP as a 4, with 6 representing “extensive changes”. While MSP participation did not change his teaching much, it did help him to be more of a change agent. Daniel wrote in the survey comments, “While my teaching has not changed in a huge way (since I used many such techniques before) my conviction regarding my beliefs have solidified to a much greater extent. As a result I am far more likely to “proselytize” with my colleagues (full and part time) to try to encourage them to incorporate similar approaches”.

For the faculty members in this category, levels of commitment (quality and extent of relationships) (Stryker 1968) were high for both MSP and faculty member identities when engaged in reform efforts. Engagement in reform efforts fostered strong and frequent positive interactions for these faculty members both within their own departments and when working with the MSP. Therefore commitment to both faculty member identities and MSP identities was strengthened. For example, Nora’s descriptions of her experiences with reform practices cohered with observations of high levels of entrainment and solidarity in her interactions with both teachers and colleagues when engaged in reform-oriented activities.

Innovator

Faculty members who fell in this second category were mainly using traditional methods of instruction such as lecture and laboratory in their classrooms before their involvement in the MSP. A few were beginning to try student-centred approaches. During their participation in the MSP, these faculty members altered both their beliefs and their practices. In the process, they also experienced several forms of cognitive dissonance. Towards the beginning of their participation in the MSP, they came to view some of their current practices as flawed. Later, they experienced a form of doubt when their actions to implement new reforms did not always work out. Viewed through the lens of identity conflict, their role identities as “good teachers” frequently came into question.

However, faculty members in this group did not get discouraged due to the ensuing identity conflicts and remained engaged with the MSP and with the process of instructional reform. Based on patterns in the data regarding their statements about themselves and their interactions with colleagues, I argue that a mediating factor that encouraged the change response to cognitive dissonance is that they adopted identities as “reform advocates” which were supported by colleagues in their departments. Therefore, rather than an avoidance response, they worked to bring their actions in greater alignment with reform advocate identities. In an end-of-project survey, this group had the highest ratings for both changes in beliefs and changes in practices, with 5 and 6 in both categories, with 1 representing no changes and 6 representing extensive changes. The average from all surveys was a “4”.

Inconsistent

This category refers to the MSP faculty members who had changed their beliefs about good science teaching, yet changes in practices were neither extensive nor consistent. For example, one of the faculty members, Troy, became an advocate of research-based best practices in curriculum development work with teachers, yet he used considerable amounts of lecture in his own courses and in conducting workshops for teachers. In response to the question, “On the scale below, please rate your approach to teaching approximately six years ago in terms of traditional (lecture based) vs. reform”; he rated his prior practices as a “2” and his current practices as a “4”. Faculty members in this category reported that they found the MSP workshops useful and underwent some changes in their practices, yet they did not fully integrate the student-centred instructional approaches from the workshops into their own teaching.

Conflicted

Faculty members in this category showed changes in some of their beliefs, yet they either reduced their participation in the MSP over time or did not implement extensive changes in their own practices. For example, one of the faculty members, Laura, had expressed a strong interest in pedagogy prior to starting the program. She also had some experience working with teachers. She reported, “I was teaching teachers who had a mix of backgrounds in technology, a wide range. I enjoy pedagogical discussions, on teaching rather than research”. However, she expressed dissatisfaction with the level of content she could convey to teachers and reduced her participation over time. Further, while she enjoyed the workshops, she did not think that they had a great influence on her teaching. She rated her changes in both beliefs and practices as “2” on a scale of 1–6, where 1 is no changes and 6 is extensive changes. Her participation in the MSP was negatively impacted because she did not have opportunities to bring the identity standard of “content provider” and the situational meanings in which she was positioned as a learner into greater coherence.

Factors that Mitigated Identity Conflict

In this section, I explore why identity conflicts became more problematic for some faculty members than for others, therefore impacting the level of change in their instructional practices. I argue that a key issue influencing the degree of change is whether faculty members experienced a sense of professional community focused on instructional reform within their own departments. For some of the faculty members, these professional communities facilitated the salience of collective identities as reform advocates. These collective identities led to some faculty members ending up as “innovators” even if they did not have extensive prior background in instructional reform. However, most of the faculty members in the “inconsistent” or “conflicted” categories faced a lack of commitment (quantity and strength of the relationships) associated with being a reform advocate, as they were the only faculty member in their college at their particular stage in the process of change (Table 1).

In comparing the experiences of faculty members who had similar responses to cognitive dissonance and identity conflict, patterns emerged regarding social interactions related to the implementation of reforms, particularly in how they described their contact with colleagues. An analysis of the data indicated that change as opposed to an avoidance response to cognitive dissonance depended on the frequency and intensity of social and emotional support for their collective identities as reformers within their departments. In the next sections, I describe the types of support for these collective identities and the impacts on the participants.

Connections with Teachers

For one of the faculty members, Nora, her identity as “reformer” was already tied to a collective identity forged through work with teachers, as demonstrated by her work with teachers being highlighted on her professional web page. This was not the case for the vast majority of college science and math faculty members, who displayed publications and grants on their web pages rather than their service activities in schools. In interviews, journals and emails, Nora’s talk suggested what Lawler (2001) refers to as a collective identity in that she attributed success to both herself and others and conveyed both pride and gratitude. For example, when evaluating a 1-day workshop for teachers on college and workplace preparedness for their students, she described, “I think the success was a result of the combination of people and events…. Teachers reflected on their learning experiences causing all of us to think a little about what we do in the class room”.

In another evaluation of an event, she described, “I think that the teachers may benefit from another sharing session—professors and teachers get together by discipline and share things that have worked for them. Each participant is on the same level—each sharing. I can adapt ideas from the high school teacher and they can use and adapt some of the things that I do”. In these and other comments, Nora’s reform advocate identity was linked to a sense of a collective endeavour with teachers.

While Nora’s extensive prior work with teachers was unusual, some of the comments by other MSP faculty members also supported the importance of teacher-faculty member community in fostering their involvement in partnership work and their interest in instructional reform. In terms of retention in the partnership, some of the faculty members indicated in interviews and logs that the positive experiences working with teachers kept them in the program. Other comments suggested that contact with teachers supported their own reform efforts. For example, one of the faculty members in the innovator category, Ellen, described her experience in a meeting with biology teachers, “instead of me changing what they do, seeing them frees me up and gives me ideas for my teaching”.

One interesting finding was that the experience of working closely with teachers on collaboratively planning new high school curricula or summer institutes was rated higher by faculty members in terms of being productive, engaging and having an impact on their own teaching than formats such as the disciplinary symposia. In addition, video analyses of these planning sessions showed teacher and faculty member participants huddled over materials together, completing each other’s sentences and coordinating their movements, all signs that indicate high degrees of entrainment and the development of solidarity.

Both disciplinary symposia and planning sessions involved teachers and faculty members coming together to discuss content and pedagogy. However, planning sessions led to more frequent successful, solidarity-building interactions, perhaps because there was a clearly defined end goal of a new course to create and implement. This outcome supports Collins’ (2004) idea of the importance of mutual focus as a precursor to successful interaction rituals. A more clearly defined mutual focus led to more entrainment, solidarity and a sense of group membership and identity between faculty members and teachers.

Coburn and Stein (2006) argue that communities of practice can be in “any place individuals opt into relationships with each other” (p. 27). In this study, the connections with teachers enabled a sense of community that spanned several institutions (schools and universities). Through these communities, collective identities as reform advocates could be supported. However, in this study, the importance of the faculty member-teacher community in supporting reform in college teaching was only suggestive. There were only some instances that directly connected faculty members’ experiences sharing ideas with teachers with specific changes in their classroom instruction. There was considerably more evidence concerning the importance of participation within a community of reform-oriented faculty members in order to support substantial changes.

Community of Faculty Members Focused on Reform

The MSP program was in some ways able to facilitate a community of practice that extended beyond physical location. Many of the MSP faculty members cited the connections that they forged with faculty members from other institutions during meetings as a source of “inspiration” and sharing ideas. For example, in a 2006 interview, Rachel described her initial experience with the MSP by saying, “I liked to meet math and science faculty at other schools at which I did not have contacts. It is useful to meet other people. I think we need to do more problem-based learning and in some cases I don’t know that I necessarily have the tools”. These types of connections developed not only during meetings and events, but also when faculty members from different institutions worked together on curriculum development or on developing disciplinary symposia.

Yet the faculty members who were most successful in instituting changes in their own instructional practices were those who had a local professional community within their departments focused on reform in college teaching. In particular, the presence of colleagues in their department who were also attempting to change their practices at the same time was the factor that differed between the inconsistent faculty members, who were highly involved in the MSP yet had difficulty changing their lecture approaches, and the innovators who reported extensive changes. Most of the faculty members who fell into the inconsistent category reported not only that they did not change much, but also that they were the only one in their departments undergoing these types of changes and/or that they had infrequent conversations with others in their department about pedagogy. In contrast, the innovators reported frequent interactions with colleagues focused on pedagogy, such as sharing ideas, collaborating on planning courses, critiquing each other’s courses and attending workshops together. While having contact with faculty members from different institutions helped in the exchange of ideas and provided an additional incentive for faculty members to participate in MSP projects, it was not as successful as departmental communities in supporting extensive changes in practices.

As one example of the importance of a departmental professional community, there was a group of three science faculty members recruited to the MSP (Rachel, Tori and Sally) from the same department who underwent extensive changes over the course of 2 years. Each of them had mostly employed lecture approaches in their classrooms prior to their work with the MSP. In interviews and logs, they describe that through participation in the workshops and in their work with schools, they experienced considerable changes in knowledge, beliefs and practices. Rather than just claiming that they changed, they often recounted specific instances in which they employed new instructional practices or developed new projects for their courses. For example, Rachel described how after participating in a formative assessment seminar, she implemented the technique of “using laminated letters ABC and D and then asking a question to see if they are getting the concept”. Similarly, the other faculty members described specific changes, including implementing formative assessment techniques and problem-based learning.

Each of them, in a similar manner, described the interactions with their colleagues as characterized by positive emotions. For example, Tori discussed their meetings in this way:

“The positive energy and enthusiasm. As a junior faculty member…I was so happy to work with others at different levels and with different expertise, but all with a common goal. So for mentoring possibilities too. It was all about learning as a process, about making subtle changes and about being an effective teacher…. And it was good for me to see that others much more senior than I are still learning, that learning about teaching is a process that never stops…. Sometimes for me, you’re in your own field and thinking you’re doing the best teaching you can, but when I meet others I see ways to improve what I am doing. And it benefits not just the education majors but all my students to have this way of teaching and learning modelled for them”.

The positive emotional terms such as “energy” and “enthusiasm” that she associated with the difficult task of reform suggest a high level of commitment and salience of collective identities.

Tori’s quote also references the importance of a “common goal”, indicating what Lawler (2001) refers to “inseparability” in that she sees her success as tied to those of her colleagues and students. Her discussion of her MSP participation was not in cognitive dissonance terms, such as “the workshops made me question my approaches”, or even in any type of cognitive terms, such as describing particular information that she found convincing. Rather, in her own reporting about her experiences, she prioritized the emotions accompanying the learning and a pride/gratitude pairing with regard to the role of her colleagues. Through these types of emotional experiences emerging from frequent social interaction, some of the MSP participants developed collective reform advocate identities that became stronger than the individual role identities that were involved in identity conflicts.

There were many other examples from interviews and logs that showed a pride/gratitude pairing indicative of collective identities (Lawler 2001) as reform advocates. Rather than just credit themselves or the workshops for their changes, the faculty members expressed gratitude towards each other. For example, immediately after describing her implementation of a particular formative assessment technique, Rachel said,

“It is not only me, but also two other ladies in my department. And another lady and I—Sally and I—are developing problem based learning and also POGIL. I had never heard about process oriented guided instructional learning…Having been exposed to it a couple of times, we are now designing some of these POGIL activities for our classes. Mainly no books or anything, for chemistry. These meetings have given us some ideas. There are three of us, me, Sally and Tori”.

In comments such as this one, there is evidence of attributing success to both their own and their colleagues’ efforts.

Similarly, in an interview in which the question was “Describe your experience at the workshop”, Sally discussed the importance of her colleagues in supporting her efforts towards change. For example, she stated, “This workshop was not the first time I’ve heard about pedagogy for conceptual change, but this helped with ‘how do you do this?’ So now I can contact people and ask for help”. Sally credited her colleagues, affirming a collective reformer identity:

“I have Tori and Rachel here and they are senior faculty who are gung-ho about this, and it is great, too, to bounce ideas off of each other…we knew each other before, but it has been nice bonding and developing the mentoring relationship because we have the same goals…. We are much more effective as three than singly. We are all doing different courses and trying to improve them. It is a great confidence builder”.

Her language of bonding and relationships connotes solidarity and the emotional outcome of “confidence”, which is related to pride. In the interviews, she explicitly described how the new approaches were not successful initially with her students and had to be altered. However, her subsequent comments suggested that frequent interactions with colleagues mitigated the risk and struggle. For example, she described in an interview early on in the project: “Tori and I tried a few activities that are interactive and inquiry-based with students to get their feedback. It’s great not to have to do this all by yourself”.

Although it seems like it would be hard to see one’s individual classroom teaching as a “joint endeavour”, in this study, the faculty members who were innovators indicated that they did view change within their departments, or within K-20 education as a whole, as a joint endeavour. Like the other MSP faculty members, these faculty members’ interviews referenced some identity conflict, but they focused mostly on altered practices and positive experiences of working with each other. Their identities as reform advocates came with high levels of commitment, in that they saw each other on an almost daily basis. The salience of these collective identities helped provide the incentive for each of these faculty members to enact changes and risk the identity conflicts that can ensue when new practices fail in the classroom. Through this process, rather than “learner” being associated with identity conflicts due to new approaches failing or not fulfilling a content provider role, "learner" became associated with the collective goal of instructional reform within their departments.

Another faculty member, Len, also fell into the innovator category. He became very active both in partnership work in schools and in reforming his courses. Unlike Tori, Sally and Rachel, he did not have colleagues within his department involved in the MSP. However, he did have a colleague within his department with whom he worked closely in changing one of the introductory courses. Len described, “I have completely done away with the textbooks. My colleague has done the same. We designed the new course together, and work to improve it each year”. In interviews, he discussed the benefits of collaborating with this colleague in both designing the course and in advocating for changing the way his department teaches science.

In contrast, the inconsistent faculty members did not have the support of their colleagues for classroom changes. For example, Troy teaches science at a 4-year college and described his teaching initially as involving both lecture and inquiry. He discussed how the MSP workshops were useful in affirming his beliefs and providing new information about how people learn. Troy seemed to have undergone conceptual change as a result of his MSP participation, based on his discussions of student-centred practices in interviews. He explained how he had always thought it was important to involve students, but the workshops gave him justification for doing so, as well as providing him with new ideas.

However, although he enjoyed the workshops, he had a difficult time implementing some of the suggested changes. In response to an interview question in the first year of the program, “Have you gotten other ideas or added other approaches to your pedagogy?” he replied, “No, nothing new. I’m always looking for new ideas, but the course in which I could best apply the new ideas would be a course which I’m not even teaching right now…I can’t do that kind of hands-on way to teach the course I am teaching now”. In addition, his summer institutes for teachers contained considerable amounts of lecture. While he introduced more student-centred activities into his courses over time and, on a survey, he described how he had worked to “get away from lecturing and involve the students in the class”, he still had not made the same level of changes that some of the other faculty members reported.

It is not the purpose of the paper to explore why practices are more difficult to change than beliefs. Other researchers have explored issues that make practices difficult to change, such as teachers’ habits (McWilliam 2008), the resistance of students to inquiry (Wenning 2005), threats to teachers’ social relations (Greenberg and Baron 2000), lack of administrative support (Atar 2007) and difficulty with adapting general reforms to specific contexts (Hudson et al. 2006). It is certainly understandable that changing approaches to instruction is a slow process. Still, the extent of Troy’s advocacy for reform instruction in secondary schools, the positive relationships he established with teachers and the considerable time and effort that he put into several of the MSP projects did not match with the difficulty he had making changes in his own classroom.

One could argue that perhaps it was not so important for him to focus on his own classroom practices, since he still had a positive influence on improving secondary school science education through his MSP work. However, when giving workshops for teachers, he spent a considerable amount of the time lecturing, suggesting that in some ways he perpetuated traditional practices. Understanding the factors that contributed to his “inconsistencies” could inform efforts to better prepare faculty members to consistently use reform approaches when working with teachers, as well as to help facilitate changes in college instruction.

One similarity between Troy and other faculty members who fell in the inconsistent category was that the colleagues that they saw on a daily basis were not engaged in reform. For example, when Troy responded to an interview question in 2007, “Have your department colleagues or students felt any effects as a result of your MSP involvement?” Troy replied, “I talk to them and discuss what I’m doing…but I’m the youngest faculty member in an older department, and most of the older faculty members are set in their ways”. He cited the biggest challenge facing the MSP is “finding people willing to change…whereas most professors just stand up and lecture in their classes. MSP’s efforts at change, really, are needed at colleges too”.

When seen in terms of identity theory, Troy’s seeming inconsistency makes sense. Although Troy believed student-centred approaches were superior to some of his current practices, he was concerned they “would not work” with what he was teaching and he did not always try to integrate them. Seen through the lens of identity theory, changes in instructional practices can threaten the stability of role identities, since new approaches may fail, thereby leading to inconsistencies between self-perceptions and situational meanings. Unlike the innovators, it was not possible for Troy to develop a collective identity as reformer in relation to his own college classroom, since his colleagues were not involved in changing their practices. There were no solidarity-building interactions around reform in his department and therefore little commitment (strength of relationships) to a collective identity associated with change. For Troy and others in this category, within their own colleges, role identities were more salient than collective identities, and there was not much incentive to risk identity conflict by making extensive changes in college courses. However, within Troy’s MSP work, he experienced relatively high levels of commitment, as his projects involved working closely with teachers and faculty members from other colleges.

Similarly, another faculty member in the inconsistent category, Brett, reported that after the initial MSP workshops, he was “convinced that concrete interactive activities are needed for long-term retention”, suggesting that he experienced some form of conceptual change through MSP participation. Yet throughout his involvement, he did not change his own practices much. His evaluation comments reflected the difficulties he faced implementing reform even when he agreed with the ideas: “It was generally interesting to learn the pedagogical principles, and definitely affected my thoughts on my teaching, though I found it much harder to incorporate the ideas effectively than I expected. Many of my tries to use the ideas in my classroom did not work so well”. At different times in interviews and journals, he reflected on the particular difficulties he was having, indicating that he was trying new approaches without experiencing a sense of success. For example, he described,

“I knew already that it is good not to just lecture, but it is very hard to do things that are hands-on. I find that students don’t understand the question and go off on tangents you could not have predicted. So you need to know what you’ll do and plan out the hands-on lessons and rehearse them, which means you need to plan out lessons way in advance…. It is hard to plan interactive lessons, especially if it is the first time you are teaching a class. I did try to do hands-on stuff more, though, because of attending these workshops”.

Throughout his time in the MSP, his beliefs reflected the research-based, student-centred best practices, yet he reiterated the struggle he had bringing about changes in his own classroom. On the survey administered after the project ended, he rated his changes in beliefs as a 4 on a scale of 1–6, yet changes in practices were only rated a 3. His comments on the survey expressed hesitation due to uncertainty regarding how to address the failures and struggles that continually emerged.

While the inconsistent faculty members found the risk of failure discouraging, for the innovators, the failures that occurred when instituting new approaches were less of a threat to their role identities. Their collective reform advocate identities were more salient, as they were associated with high levels of commitment due to the emotional effects of frequent social interaction within their college departments. When new activities failed, they could achieve a sense of solidarity through discussing these “failures” with colleagues and planning for improvements. Further, their success was tied to each other’s success, as they attributed their positive emotions to pride/gratitude; conversely, when they failed, it was not just seen as an individual failure, but an opportunity to discuss the incident with colleagues in order to generate ideas that would help attain collective goals.

Conclusions

In this study, most faculty members experienced some type of cognitive dissonance associated with their adopting new ideas, questioning their own practices, and working in partnership with K-12 teachers in support of student-centred science and math instruction. However, only some of them made substantial changes in their own classroom practices. This study showed how the path from their cognitive dissonance to changes in instructional practices was mediated by identity conflicts that were a by-product of the dissonance. In terms of the research question, “What accounts for differences between faculty members in their response to dissonance and the extent of their instructional change efforts in their own college-level classrooms?”, these differences can best be explained by the relative salience of role identities and collective identities.

Role identity conflict might be an inevitable outcome of instructional reform efforts, since educators trying new approaches are unlikely to experience success initially. Even minor failures or difficulties can then lead to a loss of confidence and an inclination to avoid engagement in reform efforts. In this study, as faculty members encountered new ideas and attempted to implement them, their role identities as competent instructors and providers of content knowledge were brought into question. However, for some of the faculty members, collective identities became more salient than role identities, contributing to a “collective efficacy” that reduced the importance of identity conflict and contributed to persistence.

An understanding of the relationship between identity conflict, social interaction and instructional change can help in planning for reform efforts, which addresses the fourth research question, “How can efforts towards reform be more successful at promoting a change outcome of cognitive dissonance, rather than avoidance or rationalization outcomes?” Based on this study, I argue that one way to mitigate identity conflict and promote instructional change is to establish conditions so that collective identities focused on reform are likely to become more salient than the role identities involved in conflict. Through the emphasis on collective identities, cognitive dissonance can lead to change without a loss of self-efficacy.

Local reform-oriented communities in which participants share a common goal may be vital to promoting these collective identities. In this study, collaboration centred on reform within change-oriented departments led to positive interactions associated with high levels of emotional energy and a sense of solidarity. Even failures within faculty members' own classrooms could be a focus for solidarity-building interactions with colleagues when planning for change. Because some faculty members’ collective identities as reformers were associated with emotional energy and commitment, these identities became more salient than their individual role identities as instructors. They then had the incentive to take the risks involved in changing their practices, since these changes would further their ability to participate in these communities.

Overall, the results of this study can inform other projects striving to promote productive collaborations between faculty members and teachers in the interest of K-20 instructional reform. In this study, the MSP’s “core connector model”, which promoted a sense of community between faculty members at different institutions and between faculty members and teachers, was effective in fostering retention in the program, exchange of ideas and a collaborative approach to MSP projects. However, these distance communities were less effective in promoting innovation in faculty members’ own teaching practices. The faculty members who experienced the most changes in their own practices were those who had frequent, face-to-face contact with colleagues also engaged in reform efforts within their own departments. Based on these results, one strategy that could support instructional change would be recruiting in teams from departments and setting up departmental projects that entail shared goals, thereby developing local professional communities. Increasing the salience of the relevant collective identities can support collective efficacy, which can lead to persistence through struggles to bring actions and beliefs about instructional reform into greater alignment.

On a more theoretical level, the results of this study suggest the need to rethink conceptual change frameworks for reform that mainly privilege cognitive processes such as changing educators’ individually held beliefs. In this study, the emotional and social outcomes seemed to better predict change than the degree to which faculty members embraced new ideas at a cognitive level, and viewed their own teaching as flawed. When faculty members were isolated within their departments, even extensive changes in beliefs were not able to facilitate changes in practice. However, within reform-oriented departments, the sense of solidarity and emotional engagement provided the basis for the formation of collective identities, collective efficacy and the incentive for change. This study therefore suggests the need to integrate social, emotional and identity-related components into models of reform that are based on cognitive dissonance or conceptual change.

Notes

Throughout the paper, I use the term “educators” to refer to both teachers and faculty members.

References

Atar, H. (2007). Investigating inquiry beliefs and nature of science (NOS) conceptions of science teachers as revealed through online learning. Doctoral dissertation, The Florida State University.

Bandura, A. (1995). Perceived self-efficacy. In A. S. R. Manstead & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Blackwell encyclopaedia of social psychology (pp. 453–454). Oxford: Blackwell.

Battista, M. T. (1994). Teacher beliefs and the reform movement in mathematics education. Phi Delta Kappan, 75(6), 462–463.

Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University. (1998). Reinventing undergraduate education: blueprint for America’s research universities. Stony Brook: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(8), 1187–1218.

Coburn, C. E. (2001). Collective sensemaking about reading: how teachers mediate reading policy in their professional communities. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(2), 145–170.

Coburn, C. E., & Stein, M. K. (2006). Communities of practice theory and the role of teacher professional community in policy implementation. In M. I. Honig (Ed.), New directions in education policy: confronting complexity (pp. 25–46). Albany: SUNY.

Collins, R. (2004). Interaction ritual chains. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Feldman, A. (2000). Decision making in the practical domain: a model of practical conceptual change. Science Education, 84(5), 606–623.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston: Row and Peterson.

Gess-Newsome, J., Southerland, S. A., Johnston, A., & Woodbury, S. (2003). Educational reform, personal practical theories, and dissatisfaction: the anatomy of change in college science teaching. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 731–767.

Greenberg, J., & Baron, R. A. (2000). Behavior in organizations (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury: Sage.

Hudson, P., Miller, S., & Butler, F. (2006). Adapting and merging explicit instruction within reform based mathematics classrooms. American Secondary Education, 35, 19–32.

Kindfield, A. H., & Singer-Gabella, M. (2010). Inscriptional practices in undergraduate introductory science courses: a path toward improving prospective K-6 teachers’ understanding and teaching of science. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(3), 58–88.

Korthagen, F. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 77–97.

Lawler, E. J. (2001). Interaction, emotion, and collective identities. In P. J. Burke, T. J. Owens, R. Serpe, & P. A. Thoits (Eds.), Advances in identity theory and research. New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

McWilliam, E. (2008). Unlearning how to teach. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 45(3), 263–269.

Midgley, C., Feldlaufer, H., & Eccles, J. S. (1989). Change in teacher efficacy and student self- and task-related beliefs in mathematics during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 247–258.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Morrell, P. D., Wainwright, C., & Flick, L. (2004). Reform teaching strategies used by student teachers. School Science and Mathematics, 104(5), 199–213.

Mulryan-Kyne, C. (2010). Teaching large classes at college and university level: challenges and opportunities. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), 175–185.

QSR International. (2006). NVivo (version 7.0) [computer software]. Melbourne: QSR International.

Roehrig, G. H., & Luft, J. (2004). Constraints experienced by beginning secondary science teachers in implementing scientific inquiry lessons. International Journal of Science Education, 26(1), 3–24.

Settlage, J., Southerland, S. A., Smith, L. K., & Ceglie, R. (2009). Constructing a doubt-free teaching self: self-efficacy, teacher identity, and science instruction within diverse settings. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46(1), 102–125.

Siry, C. (2013). Exploring the complexities of children’s inquiries in science: knowledge production through participatory practices. Research in Science Education, 43(6), 2407–2430.