Abstract

A primary focus among colleges implementing student success reforms has been to increase overall rates of completing any credential and to reduce racial and socioeconomic equity gaps in such completion rates. The focus on general completion may overlook inequities in the type of program students complete, which is particularly significant given the wide variety of credentials offered at community colleges and the resulting variation in labor market returns among completers. Our study examines racial/ethnic stratification among community college students as they enter and progress through programs leading to higher or lower opportunities in the labor market. Using a discrete-time survival analysis and longitudinal enrollment and transcript data. We track enrollment, completion, and transfer for up to 9 years. We also measure achievement of academic milestones (such as credit accrual) along educational pathways associated with higher rates of credential completion and transfer over the long term. Results suggest that a significant gap in the likelihood of bachelor’s degree completion between Black and White students emerges episodically, while the gap between Hispanic and White students develops earlier and remains consistent over time. Results also suggest that, while all students generally benefit from attainment of academic milestones, doing so disproportionately benefits Black and Hispanic students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Community colleges, which have open-access admissions policies, have long been instrumental in providing higher education for a diverse population of students, facilitating upward social mobility for those from groups that have been historically underrepresented among college graduates, including students of color, students with low socioeconomic status (SES), and first-generation college students (Ginder, 2018). Yet the promise of social mobility through community college remains unfulfilled for many, as program completion and transfer rates are low and equity gaps are persistent (Crisp & Nuñez, 2014; Shapiro et al., 2017). Even among students who successfully complete their programs, a growing body of research suggests there is substantial variation in the economic opportunity they gain based on the type of postsecondary award they earn at community college (such as transfer-oriented associate degree, workforce-oriented associate degree, or workforce-oriented certificate) and their field of study (Belfield & Bailey, 2011; Minaya & Scott-Clayton, 2017). The difference in earning potential between students who leave community college with a workforce entry- versus a transfer-oriented credential is substantial, but it is also the case that a transfer-oriented associate degree without an accompanying bachelor’s degree does not generally have that much labor market value (Bahr, 2016; Belfield & Bailey, 2017; Prince, 2015). Which programs students enroll in and whether they complete them is thus very consequential for their future earnings (Jenkins & Weiss, 2011).

Students from different backgrounds are not equally distributed across program enrollments and completions; they are instead stratified along racial/ethnic and socioeconomic lines (Jenkins & Weiss, 2011; Prince, 2015). In order to close equity gaps in program participation and outcomes along high-return pathways, it is critical to examine the points at which students’ trajectories diverge as they progress toward their educational goals (Attewell et al., 2012; Calcagno et al., 2007). We undertake such an examination in this study. Using data from an anonymous state with a large community and technical college system, we track how measures of “academic momentum” or the achievement of academic milestones including major declaration, program entry, credit accrual and gateway course completion contribute to transfer and program completion outcomes of more than 500,000 students who entered one of the state’s community colleges between 2009 and 2018. Specifically, this paper investigates: (1) When over the course of their educational trajectories are students most likely to leave pathways leading to certificates and degrees with higher post-graduation earnings opportunity? (2) How does the achievement of academic milestones contribute to the likelihood of credential completion or transfer? Does attainment of academic milestones have heterogeneous effects based on race/ethnicity? Results suggest that Black and Hispanic students’ trajectories diverge from White students’ trajectories at different time points. Achievement of a set of academic milestones benefited race/ethnicity subgroups differently, with disproportionately positive benefits for Black and Hispanic students in many cases.

The paper is organized as follows: We first discuss prior literature and the framework. We then present our methodological approach and the sample for this study. Finally, we describe our findings and discuss implications for improving postsecondary attainment for Black and Hispanic community college students.

Prior Literature: Labor Market Value of Community College Credentials and Factors Contributing to Completion

Labor Market Returns by Field and Credential Type

While bachelor’s degrees yield strong earnings benefits in general, labor market returns vary significantly by college major (Arcidiacono, 2004; Belfield & Bailey, 2017; Berger, 1988; Carnevale et al., 2017). Further, women, students from low-income backgrounds, and historically underrepresented students of color are more likely to enter majors that lead to lower-remuneration employment (Carnevale et al., 2016; Castex & Kogan Dechter, 2014; Zafar, 2013).

A growing body of research investigates labor market returns to sub-baccalaureate credentials, including the associate degrees and certificates commonly awarded by community colleges. While the earnings benefits are not typically as strong as those resulting from a bachelor’s degree, research has found positive earnings returns to most sub-baccalaureate credentials; the strongest and most enduring returns accrued to associate degrees, followed by long-term certificates (Bahr, 2016; Belfield & Bailey, 2011, 2017; Jepsen et al., 2014; Minaya & Scott-Clayton, 2017; Prince, 2015). In general, the more credits required for a degree, the higher the labor market returns, and researchers have found that earning even just a few community college credits without completing a credential yielded some labor market benefits (Bahr, 2016; Belfield & Bailey, 2017; Jepsen et al., 2014).

As with bachelor’s degrees, labor market returns to sub-baccalaureate credentials vary significantly by program or major. Across degrees and certificates, returns are higher for health, quantitative, and technical fields, and lower for humanities, education, social sciences, and other academic disciplines (Bahr, 2016; Belfield & Bailey, 2017; Holzer & Xu, 2019; Stevens et al., 2019). The type of credential and its relationship to transfer is also important. As mentioned just above, associate degrees generally confer more value in the labor market than certificates. Associate of science degrees—which are the typical structured-transfer-oriented degrees (that serve to establish a student with junior standing in a major at a 4-year college) conferred by community colleges—and associate of applied science degrees—the direct workforce-oriented degrees conferred by community colleges—often result in higher paying jobs than broad and general associate of arts degrees, which are academic in nature and designed for students intending to transfer, but in an unstructured fashion, without junior standing in a 4-year college program. In fact, associate of arts degrees have very little value on their own on the labor market and confer roughly the same earnings benefits as earning credits but no degree (Belfield & Bailey, 2017). Thus, students who complete transfer oriented degrees, but fail to transfer have postsecondary degrees with limited earning potential in the labor market.

Student Characteristics and Program Entry and Completion in Community Colleges

While there have been numerous studies of the effects of student characteristics on choice of major in bachelor’s programs, few studies have considered the relationship between race/ethnicity and program selection in community colleges. The relationship between student characteristics and program choice in community colleges appears to be more complex than in 4-year colleges. Not only do community colleges and 4-year institutions vary in terms of student demographic characteristics and majors offered, but community colleges also offer greater variation in the types of credentials that they award, including short- and long-term certificates, workforce-oriented degrees, and transfer-oriented degrees (Baker, 2016; Bailey et al., 2015). Bahr (2016) and Stevens et al. (2019) found a large amount of variation in labor market returns by community college credential field, the number of credits required to earn credentials, and student race/ethnicity and gender. Other studies have highlighted the fact that, similar to what is observed in 4-year institutions, earnings outcomes from community college credentials tended to reproduce patterns of social stratification. Prince (2015) found that Black, Hispanic, and Native American students were more likely than Asian and White students to choose career and technical education (CTE) programs that have low labor market returns and to opt for short-term certificates or leave college with no award at all. Jenkins and Weiss (2011) found that students from low-income backgrounds were less likely to enter a program of study of any kind; those who did enter a program were more likely to enter CTE, education, or childcare programs with low completion rates and low post-graduation earnings potential.

In addition to type of postsecondary credential, major or field of study, and student demographic characteristics, achieving early momentum of academic progress in college contributes to the likelihood that students will complete the credential programs that they begin and influences the types of postsecondary pathways that are accessible to them. In the next section, we discuss the literature on the relationship between the achievement of academic milestones and the likelihood of credential attainment and transfer in order to identify critical junctures when student trajectories toward high- or low-opportunity postsecondary outcomes first emerge.

Academic Milestones and the Likelihood of Credential Attainment and Transfer

Whether and when community college students achieve early academic milestones, such as accumulating credits, entering a program of study, completing remedial requirements, and passing introductory-level math and English courses, can affect their likelihood of graduating (Adelman, 1999, 2006; Attewell et al., 2012; Jenkins & Bailey, 2017; McCormick, 1999). McCormick (1999) argued that early credit accumulation provides a useful leading indicator of the likelihood that students will complete a college credential. In a study of 4-year college students, he found that those who earned 30 credits in their first year of enrollment were more than twice as likely to complete a degree than those who earned fewer than 20 credits in their first year. Adelman (1999, 2006) introduced the idea of “academic momentum,” which holds that students who complete college credits at a faster rate are more likely to graduate than similar students who complete credits more slowly. Attewell et al. (2012) used growth curve modeling to explore which milestones in Adelman’s (1999, 2006) model had the largest impacts on the likelihood of completing a degree, and found that delaying entry to college after high school and starting college with a lower course load lowered graduation rates, while taking summer courses increased the likelihood of graduation. Jenkins and Cho (2012) found that students who failed to enter a program of study in the first year of enrollment were less likely to ever enter a program of study, and consequently unlikely to earn any credential.

While achieving academic milestones is a good indicator of postsecondary momentum, the effects of achieving these milestones differ depending on student demographic characteristics including gender, SES, academic preparedness, and age (Attewell et al., 2012; Calcagno et al., 2007; Holzer & Xu, 2019; Jenkins & Weiss, 2011). Calcagno et al. (2007) used a discrete time hazard model to estimate when, during a 17-term period, younger or older students were more likely to earn a degree or certificate. Controlling for prior academic performance, the authors found that older students were more likely to complete degrees or certificates at every time point. Additionally, to explore causes of the gender gap in STEM occupations, Speer (2019) identified when during STEM trajectories in college female students were most likely to exit. Although women exited in some numbers throughout the duration of the STEM pathways—from high school through post-college job entry—Speer found that the periods associated with STEM readiness in high school and major choice in college were the biggest loss points, and thus also represented the most promising intervention opportunities to increase female entry into and persistence in STEM.

Further, it is not the behaviors or characteristics of individual students alone that influences the rate of academic momentum; the type of program students enter, and the administrative structures of such programs can also support or discourage faster achievement of milestones. Enrollment in programs in certain fields was associated with higher rates of credential attainment (Jenkins & Weiss, 2011). Holzer and Xu (2019) found that entry to certain programs of study in community colleges—including health and applied STEM associate degree programs—and credit accumulation in the first year of enrollment were associated with higher rates of degree attainment. The institutional structure and policies supporting a program also make a difference in graduation rates. Baker (2016) found that transfer-oriented associate degree attainment rates rose by 35% in community college departments in California that introduced structured transfer degrees and that standardized course-taking requirements and guaranteed admissions at 4-year institutions. Across programs, assignment to remedial or developmental courses, in which low-income and students of color are overrepresented, also limits academic momentum (Bailey et al., 2010). As scholars have identified the benefits of gaining early academic momentum, college leaders have translated these findings into a set of early momentum metrics (Belfield et al., 2019) in order to track their progress in implementing student success reforms.

Building on this research on academic milestones and momentum, our study conceptualizes academic momentum as including the following measures: major declaration, entry to a program of study, credit accumulation, and completion of introductory level math and/or English courses.

Framework for Classifying Community College Programs

With their varied purposes, lengths, and subject matters, categorizing community college programs by their likelihood of increasing opportunity for graduates is a messy and complicated endeavor. While some community college programs intend to prepare students for direct workforce entry, others are designed to prepare them for further education through upward transfer to bachelor’s degree programs. In contrast to bachelor’s degrees, whose market value is primarily determined by major, the value of community college sub-baccalaureate credentials varies by the length of the program as well as by field. For example, a graduate holding a short-term certificate to become a nursing assistant would not typically receive the same economic benefit as an otherwise similar graduate holding an associate degree in nursing. Defining the value of transfer degrees presents another dilemma, because these credentials are not intended to prepare students for direct entry into the workforce and indeed have relatively little immediate labor-market value alone (Belfield & Bailey, 2017). If the value of workforce credentials is career-path employment and earnings post-graduation, then the value of community college transfer programs is preparedness for success in bachelor’s programs. While a transfer-oriented associate degree may not confer much immediate labor-market value, completion of a bachelor’s degree has wide-ranging benefits for students, including higher earnings (Belfield & Bailey, 2017; Carnevale et al., 2017; Vuolo et al., 2016).

In this paper, we use a taxonomy for classifying programs that is based either on the market value upon completion of workforce programs or on whether they are designated as structured or unstructured transfer-oriented degree programs.Footnote 1 Specifically, we use earnings among students who complete workforce programs to classify workforce programs as leading to relatively low-, mid-, or high-remuneration employment. The groupings of the workforce programs in this study are based on a state education agency analysis that used state unemployment insurance wage records and earnings among recent graduates to categorize programs. Table 1 shows the average hourly wages among students in each of the workforce categories, as well as which programs in each category (including transfer-oriented programs, discussed just below) students in our study enrolled in most frequently.

We categorize transfer programs based on whether or not they are structured or unstructured. Colleges and universities design structured transfer programs to provide students with junior standing in a group of majors or a specific major upon transfer into a 4-year institution. These structured transfer programs typically require students to clarify an intended broad field of study for their bachelor’s degree program (e.g., business transfer) or a specific bachelor’s degree major at a university (e.g., biology transfer at flagship university). In contrast, unstructured, general transfer programs are not designed to prepare students for specific bachelor’s degree majors and/or university transfer destinations; instead they allow students to choose from a wide range of courses that fulfill broad, lower division, “general education” requirements. There is evidence that unstructured transfer programs may contribute to students taking courses at community colleges that they do not need for their bachelor’s degrees; these students must often take additional credits at the 4-year college before they qualify to enter a major at that institution (Monaghan & Attewell, 2015; Xu et al., 2018).

Lastly, we are unable to confidently categorize every program into one of the aforementioned groups. We cannot identify the value of some programs in our sample, either because program information was not reported consistently or because some programs do not lead to enough graduates to assess the post-completion opportunities they lead to.Footnote 2 These programs include English as a Second Language, Parent Education, and some high school diploma completion programs.

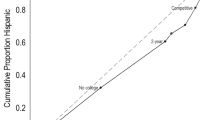

Using the categories of our taxonomy of programs, Fig. 1 shows how initial enrollments and credential completions are distributed among first-time credential-seeking students who entered a community college between 2009 and 2011.

Empirical Model and Data

Method

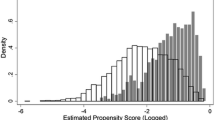

To examine stratification in the completion of higher- and lower-return programs, we employ a discrete-time survival analysis methodology following a similar strategy employed by Calcagno et al. (2007). Unlike the traditional logistic regression that examines outcomes at a discrete moment in time—such as when students start college or after a certain number of years from entry—survival analysis is designed to analyze the length of time until an eventFootnote 3 or outcome of interest occurs. For this reason, survival analysis is able to capture time-varying factors caused by the changes in enrollment patterns. Further, and more importantly for the current study, using a survival analysis allows us to dynamically estimate the impact of enrollment pathways and the achievement of academic milestones on students’ final outcomes. More specifically, we use the model to estimate the probability of mid- or high-market value credential attainment, transfer to 4-year institutions, and bachelor’s degree completion in each term of enrollment for Black, Hispanic, and White students. Then we examine whether, and if so, how, the achievement of the aforementioned set of educational milestones differentially affects the likelihood of credential completion and transfer by race/ethnicity.

In order to facilitate the use of survival analysis techniques, we converted student-level records to a person-period dataset with a maximum of 37 observations per student (one for each term in which the student was enrolled). Students were observed for up to 9.25 academic years from entry (37 terms, four terms per year). Unlike discrete estimation models, survival analysis measures each student’s probability or “risk” of achieving a certain outcome of interest in each term; students are observed or “at risk”Footnote 4 until they achieve a given outcome, at which point they are dropped from the dataset. Therefore, for each outcome/event—transfer, bachelor’s degree completion, and mid- or high-market valued credential completion—we employ a separate discrete-time hazard model. For example, in the model using transfer as the outcome, we consider a student “at risk” of transferring to a 4-year college before they transferred. Once a student has transferred, we discard their observations in the later terms; the student does not reenter the risk set. Our final datasets also include a combination of static, time-invariant variables, such as students’ demographic characteristics, which remain constant for each person in each period, and dynamic, time-varying variables, such as students’ program/course enrollment, transfer, and completion, which take on different values to indicate whether a student experienced a change in these variables in any given term.

Another benefit of our sample is that it can effectively mitigate endogenous data censoring in the survival analysis, which occurs when self-selected individuals enter the dataset later and achieve an outcome of interest after the period of observation. As a preview, our data include students who entered community colleges in a state between 2009 and 2018, meaning we observe students for different lengths of time. Because we track all students up until 2018, regardless of when they entered the community college, students who started at earlier dates had more time to achieve any outcome of interest than students who entered later. The students from the later cohorts are more likely to be censored due to the shorter tracking period. Thus, the censoring time in our study is solely determined by the availability of the most current administrative dataset, and the censoring date is non-informative or independent of outcomes. In other words, whether a student experienced an event prior to or after the censoring date is only dependent on when they enrolled and whether the length of the tracking period is long enough to track the outcomes.Footnote 5The likelihood of experiencing the outcome of interest in a given term would not be impacted by whether the censor occurs. All individuals who remain in college after the censoring date (the end of data collection) are representative of those who would have remained if the censoring had not occurred.

Our discrete-time model examines the risk of completing the outcome in each term, or the hazard of student i of outcome y in term j:

The conditional probability that a student would experience the event y in term j, given that he/she did not experience this event in the earlier term (i.e., the student was still in the risk set), is determined by a vector of time-invariant covariates and a vector of time-varying intermediate milestones. Specifically, G is a vector of time-invariant variables for student race/ethnicity, X includes indicators for other time-invariant student characteristics, and Z reflects the time-varying intermediate milestones that will be specified in the result section. To write the algebraic equation, we use the logistic regression and take the logit of the hazard to transform the relationship to the linear function:

where \({D}_{j}\) denotes the series of dummy variables for each term and \(\alpha \) is a vector of coefficients reflecting the odds of experiencing the event in each term. In other words, our discrete-time model does not restrict how time affects the probability of experiencing the event. The advantage of a nonparametric model that assumes no functional form of the time components is that it allows the model to capture the effect of time-varying enrollment patterns. This is useful because any unobservable factors affecting enrollment patterns, like seasonal enrollment fluctuation, are reflected in the term dummy variables and thereby controlled for in the model. Although nonparametric model complexity grows with higher numbers of observations, given the large size of our sample, the addition of 37 dummy variables for each term does not significantly impact the degrees of freedom of the estimation. Finally, the model includes cohort and institutional fixed effect to control the cohort based and institutional differences.

We also analyze differences in student behaviors at key academic milestones across different races/ethnicities. To do so, we add in a race/ethnicity and milestone interaction term \({(G}^{{\prime}}\times {Z}^{{\prime}})\) in Eq. (3), which measures whether there is a difference in the impact of milestones on the probability of experiencing the event in any given term across races/ethnicities.

Estimates calculated using Eq. (3) are expressed in odds ratios, where \(\partial \) equal to 1 indicates that there is no difference between two groups and \(\partial \) larger than 1 means that the benefit of earning the specific milestone is \(\partial \) times larger than the benefit of the baseline group.

Data

Our study uses administrative records of first-time, credential-seeking community college students in an anonymous state with more than 20 community colleges. We track 573,806 students who entered any of the state’s community colleges between 2009 and 2018. The dataset includes student enrollment and transcript records for the entire period, so students in the earliest cohort are followed for up to 9 years. In addition to information on community college course-taking and completion, the administrative records include information on student characteristics such as race/ethnicity, gender, age, SES, disability status, and enrollment in developmental education courses, and the earnings tertiles measured in the 3rd quarter after exit. In addition, we merge the administrative data with the data from National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) to track students’ transfer to and graduation from 4-year institutions.

State Contexts

The sampled state ranks in the top quintile in terms of median household income in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). The proportion of Black and Hispanic students at the sampled community colleges is lower than the national average (American Association of Community Colleges, 2021). The average cost of attending community colleges in the state is at the national average level. Several community colleges of the state offer both associate degree and bachelor’s degree in some high-demanding fields. The state higher education governance structure includes a statewide coordinating board, which is responsible for dispersing statewide financial aid and coordinating with independent coordinating boards or associations representing different educational sectors in the state. There are separate statewide associations representing public 4-year institutions, private nonprofit 4-year institutions, and public community colleges. These entities regularly cooperate through statewide councils, and the state has established numerous statewide associate degree articulation agreements to help students transfer from community colleges to 4-year colleges and universities. There are two types of associate degree to meet students’ different transfer intentions—unstructured and structured transfer degree. As introduced in the second section, “unstructured” or general transfer degrees prepare students to fulfill the general education credits and provide them the flexible transfer pathways, while “structured” or major-specific transfer degrees enable students complete many of the major-related prerequisites before transfer and provide students with junior standing in 4-year institutions. Other than the transfer-oriented degrees, which comprise about 40 percent of awards conferred by community colleges in the state each year, the community colleges in the sampled state also offer a wide variety of professional and technical degrees and certificates.

Table 2 summarizes the key outcomes and characteristics of the students in our sample by racial/ethnic group. In our analyses, we focus on comparisons between Black and Hispanic students and White students.Footnote 6In our final sample, 57% of students were White, 6% were Black, 3% were Hispanic, and 34% were other races/ethnicities.Footnote 7 In our sample, compared to White students, Black and Hispanic students were more likely to be eligible for need-based financial aid. In addition, Black students were more likely than White or Hispanic students to enroll in developmental coursework.

In our sample, there are substantial differences in long-term outcomes and major milestone completion rates across racial/ethnic groups. First, of all the student groups considered, Black students were the most likely to stop out for more than four terms (equivalent to 1 academic year in the state of interest). Additionally, compared to White students, relatively more Black students and relatively fewer Hispanic students declared a major during the time of observation. Black students enrolled in programs leading to field-specific transfer degrees and workforce degrees with medium or high market value at moderately higher rates than their White counterparts. However, Black students completed these degrees at low rates, on average. 16% and 33% of Black students enrolled in a structured transfer program or a program leading to a credential associated with medium or high wages, respectively; however, only 1.5% of Black students completed a structured transfer degree program, and only 7.3% completed a mid- or high-paying workforce credential program.

In comparison to White and Black students, fewer Hispanic students entered either transfer programs (structured and unstructured) or workforce programs that lead to mid- or high-paying employment. However, the differences in degree completion between White and Hispanic students are smaller than those in program enrollment; for example, 12% of both Hispanic students and White students completed an unstructured transfer degree program (which exceeds the proportion of Black students who completed such a program). In addition, compared to other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic students are overrepresented in certificate attainment.

We also consider “early momentum” credit indicators. By examining these metrics, we can see if a student makes timely progress toward program completion. In this study, we consider five credit milestones for program completion: earning 6, 12, and 24 college-level semester-equivalent credits, and earning any credits in college-level math or English courses. Previous research shows that these indicators are associated with higher degree completion rates over a longer term (Belfield et al., 2019).

On all five measures, the White-Black gap is larger than the White-Hispanic gap. For example, on average about half of the White students and 47% of the Hispanic students in our sample earned 24 credits, while only 39% of Black students did so. A similar pattern emerges with college-level math completion: 39% of White students and 34% of Hispanic students earned at least one credit in college-level math, while just 27% of Black students ever did so.

Results

First, we estimate the basic hazard model of Eq. (2) for a simple baseline model for all three outcomes. Table 3 presents the odds ratios and standard errors of the logistic regression models. Model (1) tracks student transfer for up to six academic years.Footnote 8 In general, in any given period, Black student are 0.93 times as likely as White students (baseline group) is to transfer to a 4-year university; Hispanic students are only 0.71 times as likely as White students to transfer to a 4-year university. On attainment of a bachelor’s degree,Footnote 9 the inequity is more severe for Black students: Black students are only 0.65 times as likely as White students are to attain a bachelor’s degree, while the difference between Hispanic and White students is not statistically significant. Black and Hispanic students are also less likely than White students to complete a workforce credential with medium or high market value. Their likelihood of completing a workforce program that leads to mid- or high-paying employment is 0.74 and 0.82 times that of White students, respectively.

When Do Gaps in Attainment of Outcomes Emerge?

Next, we use the term dummy variables in the models to depict the estimated hazard probabilities of experiencing completion of three events/outcomes of interests in the study—medium- or high-paying workforce credentials, transfer, or bachelor’s degree attainment for Black, Hispanic, and White students. To better present the achievement gaps and the differences in the White-Black and White-Hispanic gaps, we separate the hazard probability chart by white and black only and white and Hispanic only. First, Fig. 2 shows the hazard probability of transfer by terms for White, Black and Hispanic students. After term 15 (approximately 4 years), the hazard probability of transfer is very low, suggesting that the likelihood of transfer is small if students enroll in community colleges for more than four years, regardless of race/ethnicity. There is a clear difference between the Black–White gap and the Hispanic–White gap in transfer. Specifically, the disparity between Black and White students in transfer emerges most significantly around the ninth term, which is approximately how long it takes a student enrolled full-time to complete an associate degree. In contrast, the Hispanic-White gap emerges mostly in the first five terms. These different patterns may imply that lower rates of transfer for Black students are driven by disparities in program completion, while lower rates of transfer for Hispanic students are driven by inequities that arise in the beginning of the program.

Second, Fig. 3 illustrates the same hazard probability chart for the outcome of bachelor’s degree attainment across terms. Like the findings of the analysis on transfer, substantial gaps in attainment arise between White students and both Black and Hispanic students around the 16th, 20th, and 24th terms (approximately 4th, 5th, and 6th years), though the gaps are larger for Black students. For Hispanic students, the gap in bachelor’s degree attainment also emerges earlier, in the eighth term (approximately 2nd year).

Finally, the odds of earning a mid- or high-value workforce credential are low overall for students in each racial/ethnic group; few students in the sample earned these awards. Hazard probability graphs in Fig. 4 show that gaps in rates of attainment of mid- and high-paying workforce credentials between White and both Black and Hispanic students begin to emerge in terms 5 and 6. Overall the probability of earning these awards for any student is small and the patterns of degree completion are noisy.

Leakage Points From Program Pathways: Where Do Students Go?

The analysis so far shows that the leakage points along the pathways to student success are sometimes different for Black and Hispanic students, but questions remain regarding where students who leave pathways toward transfer, bachelor’s degrees, and mid- or high-value workforce credentials ultimately go. As shown in the descriptive summary in Table 2, the degree completion rate is relatively lower while the drop-out rate is relatively higher for Black students, compared to their White counterparts. It implies that one major leakage point for Black students is incompletion. Similarly, we suspect that Hispanics students leave the higher-opportunity pathway due to their low major declaration rate and high low market value degree attainment rate. Thus, we use the same strategy to study two possible leaking channels: low-market-value workforce credentials and dropout. By replacing the more beneficial outcomes in the model with earning a low market value workforce credential and with stop out,Footnote 10 respectively, we observe the paths students take to these two alternative outcomes for Black, Hispanic, and White students. Figure 5 shows that Hispanic students are more likely than White students to earn low-value workforce credentials in the first several terms after entry. This confirms that one of the major leakage points from high-value programs for Hispanic students may be through earning low-value workforce credentials. In contrast, Black students generally do not exit because they are earning low-value workforce credentials. Though Black students’ completion of such programs in the first two terms is slightly higher than that of White students, a gap in the other direction then emerges and is sustained in later terms. The dropout hazard estimates in Fig. 6 echo that early stop out is the major leakage point for Black students.

Achievement of Academic Milestones

We analyze the importance of reaching the key academic milestones and their effects on Black and Hispanic students. To do so, we estimate Eq. (3), where each regression focuses on a specific milestone. We present the coefficient for each milestoneFootnote 11 and for the interaction between the milestone and the race/ethnicity dummy. As discussed earlier, the interaction term indicates whether there is a difference between the impact on White students and the impact on Black or Hispanic students. To estimate the impact of milestones that are specific to Black or Hispanic students, we can use the coefficient on the milestone and the interaction term to compute the joint impact. Next, we present how this computation is conducted.

Tables 4 and 5 report estimates for the milestones and the interaction terms as odds ratios. Each column represents separate regressions with each specific milestone. In the first row, we show the baseline impact, or the effect on White students, of reaching each academic milestone on specific student outcomes. For example, in Table 4 the first row of column 1 presents the baseline impact of enrolling in a structured transfer program on the likelihood of transferring to a 4-year college. On average, the odds a White student who enrolls in a structured transfer program transfers to a 4-year college in any given term are 1.68 times those of a White student who does not achieve this milestone.

The second and third rows of Tables 4 and 5 list a relative ratio that indicates whether enrolling in a structured transfer program benefits Black, Hispanic, and White students differently. As shown in Table 4, we find that the relative impact of enrolling in a structured transfer program on transfer for a Black student is 0.94, suggesting that, though the difference is not statistically significant, Black students benefit less from this milestone completion than White students (Note it does not mean that there is no benefit for Black students to complete this milestone). In contrast, the probability that a Hispanic student enrolled in a structured transfer program transfers to a 4-year institution is 1.25 times greater than the odds that a White student enrolled in a similar program does so, though the difference is only marginally significant (p < 0.1).

We can also use these results to calculate the impact of enrollment in structured transfer programs on Black or Hispanic students specifically by multiplying the baseline impact on White students (row 1) and the interaction (row 2 or 3). The results of this exercise are presented in rows 4 and 5 of the same tables. Our results show that a Black student who enrolled in a structured transfer program is 1.58 times as likely to transfer as a Black student who did not enroll in such a program, and a Hispanic student who enrolled in a structured transfer program is twice as likely to transfer than their counterfactual who did not enroll in a structured transfer program, though the results are not statistically significant.

We apply the same calculation to all the milestones and outcomes and summarize the coefficients of milestones for race/ethnicity subgroups in Table 6. Overall, for White students, the biggest effects on transfer rates are from completing either a structured or unstructured transfer associate degree (which increases the likelihood of transfer by 7.2–7.7 times), generating credit and gateway course momentum (by 2.7–4.8 times), and enrolling in a transfer program (by 1.7 times). For Black and Hispanic students, completing a transfer associate degree and reaching credit/gateway course momentum milestones are disproportionately positive predictors of likelihood to transfer. Reaching the credit and gateway course momentum milestones are especially beneficial for Hispanic students (5.8–10.6 fold increases in likelihood of transferring, compared to 2.7–4.8 fold increases for White students), whereas Black students experience similar benefits as White students.

The associations of milestone completion on the odds of bachelor’s degree attainment are similar to the effects of milestone completion on the odds of transfer, though the magnitudes of the coefficients for bachelor’s degree attainment are smaller. With respect to White students, completing a transfer-oriented associate degree, enrolling in a transfer program, and generating credit/gatekeeper momentum all increase the odds that students complete a bachelor’s degree (by 3.8, 1.3–1.4, and 1.6–2.9 times, respectively). Many of these milestones have disproportionately positive benefits on bachelor’s degree attainment for Black and Hispanic students, as compared to White students.

Results by Gender and Income Within Racial/Ethnic Groups

Thus far, we have described average results for students in certain racial/ethnic subgroups, but this may overlook differences within racial/ethnic subgroups along gender and socioeconomic lines. In results presented in the Online Appendix, we replicate our analysis for combinations of race/ethnicity, gender, and whether or not students were ever eligible for need-based financial aid and summarize the primary findings below.

Degree/Credential Attainment and Transfer

Within racial/ethnic groups, women had higher rates of transfer and completion of credentials, as well as higher rates of completing academic milestones (e.g., credit momentum and gateway math and English). Black and White need-based aid eligible students had lower rates of transfer and bachelor’s degree completion than need-based aid ineligible Black and White students; there was more parity on these outcomes among need-based aid ineligible versus need-based aid eligible Hispanic students. Importantly, we find that gaps by race/ethnicity in likelihood of transfer even exist among students who are ineligible for need-based financial aid.

Impact of Academic Milestones

We further examine the impact of key academic milestones on student outcomes. With regard to the transfer-related outcomes (transfer to a 4-year university and completion of a bachelor’s degree), we observe that although all groups of students benefited to some extent from completing academic milestones, benefits were especially strong for need-based aid eligible students, Hispanic students, men, and students whose identities span multiple groups (i.e., Hispanic men and need-based aid eligible Hispanics).

In summary, the results by gender and income within racial/ethnic groups suggest that (1) race/ethnicity is a bigger driver of inequitable outcomes than income or gender; (2) groups of students with the lower possibility of transfer or completion benefit more from completing key academic milestones.

Discussion

This study highlights the importance of examining timing and disaggregating data to show the various paths that students who enter community colleges take to transfer and to earn degrees and certificates with higher or lower economic value. At specific periods in their trajectories, students from different demographic groups experience distinct barriers to completing programs leading to higher post-graduation workforce opportunity. As shown in our hazard probability graphs (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), racial/ethnic equity gaps emerge and accumulate over time, and to some extent, they compound during those terms when students typically reach certain outcomes. For example, it is most common for students to earn bachelor’s degrees during the terms at the end of their fifth, sixth, and seventh years, and indeed these are also the terms when we observe the largest racial/ethnic equity gaps. Charting when gaps emerge may help policymakers and education leaders working to mitigate disparities to create targeted strategies that provide students with support when they need it most. In addition to insights on when equity gaps emerge, this study points to a set of academic milestones that we find are linked to an increased likelihood of completing credentials that confer higher earning potential.

We find disproportionately positive benefits for Black and Hispanic students who entered and completed associate degree programs designed to prepare students for upward transfer. Completing either a structured or unstructured transfer degree substantially increased the odds of transfer and bachelor’s completion for all students, including significantly greater effects on the likelihood that Black and Hispanic students would do so. These findings are underscored by our analysis examining outcomes by gender and economic status among Black and Hispanic students. We find both stratification along race/ethnicity, gender, and economic status, and particularly strong benefits of completion of academic milestones for some subgroups (e.g., Hispanic men). This finding adds a racial equity perspective to existing research demonstrating the value of pre-transfer associate degree programs to bachelor’s degree completion (Kopko & Crosta, 2016). Similar to Crisp and Nuñez (2014), who found that students enrolled in vocational programs were less likely to transfer than students enrolled in transfer programs, we find that completing a certificate decreased the odds that students across subgroups transfer or complete a bachelor’s degree. However, while we find negative baseline effects of the completion of any workforce credentials on eventual bachelor’s degree completion and upward transfer, we find that, for Black students, completing any workforce degree modestly increased the odds of transfer (by 1.2 times) and increased the odds of bachelor’s degree completion (by 2.3 times).

We find that completion of any transfer-oriented associate degree had a strong and positive effect on the likelihood of transfer and bachelor’s degree attainment for all students, and disproportionately so for Black and Hispanic students. However, in contrast to previous research (Baker, 2016), our results do not indicate a large difference in the effects of structured versus unstructured transfer programs for White and Black students (and indeed show a much more positive effect of unstructured versus structured programs for Hispanic students). One explanation could be that structured programs were only recently introduced in the state, so a relatively small number of students in our sample actually entered or completed them. Indeed, in our sample, the vast majority of students completing transfer programs were completing those categorized as unstructured.

Broadly, this research provides additional evidence supporting the predictive value of early academic milestones for assessing the likelihood of degree attainment and transfer (Adelman, 1999, 2006; Attewell et al., 2012; Belfield et al., 2019; Calcagno et al., 2007). We find that completion of academic milestones is associated with increased likelihood of success in the long term, with additive effects for Black and Hispanic students. For example, our findings indicate that Black and Hispanic students who achieved milestones, such as gaining credit and gateway course momentum or completing transfer-oriented associate degrees, experienced stronger benefits in terms of transfer and bachelor’s degree attainment than White students. Yet fewer Black and Hispanic students reached these milestones compared to White students. For example, we find that completing a transfer-oriented associate degree increased the likelihood of bachelor’s degree completion by 5.1–6.4 times for Black students, compared to 3.8 times for White students. However, Black students earned transfer associate degrees at about half the rate of White students in our sample. Taken together, these findings suggest a potential strategy for college leaders working to eliminate racial/ethnic equity gaps in long-term outcomes like transfer and bachelor’s completion: focusing efforts on eliminating equity gaps in the completion of academic milestones.

Implications for Research

While our findings extend upon prior early academic momentum research by documenting the additive benefits of momentum for Black and Hispanic students, further research is needed both to test the robustness of our findings across other state contexts as well as for other subgroups of students who have been disproportionately impacted by inequitable educational systems. Further research on the benefits of structured transfer pathways on student outcomes could better contextualize our studies findings by testing for the impact of these programs on other outcomes such as improving the degree-applicability of transfer credits. And, since our measures of early momentum were general in nature– that is, agnostic to students’ program of study– additional research is needed to better capture students’ early momentum in a specific program of study. Wang (2017) argued that a more holistic view of student momentum would take into account students’ aspirations, motivation, and sense of purpose for attending college. Yet, research on how to measure program momentum and its benefits for students is limited, particularly for transfer-intending students who are commonly grouped into generic transfer programs (Fink et al., 2021). Researchers have operationalized program momentum metrics as accumulating credits in the same subject area (Jenkins & Cho, 2012) or by identifying program foundational coursework based on statewide transfer agreements (Fink et al., 2021), yet this is still a nascent area of research on early academic momentum worthy of additional research.

Implications for Practice

Racial/ethnic gaps in postsecondary attainment are well documented. While important, the focus on structural causes of inequitable postsecondary outcomes—including poverty, racial and socioeconomic neighborhood segregation, and mass incarceration—may lead community colleges to overlook causes at the institutional level that they have the power to change (Billings et al., 2014; Duncan et al., 2011). Community colleges need support to move from an awareness of gaps in degree attainment by race/ethnicity on their campuses to identifying mechanisms contributing to these gaps and formulating appropriate strategies to intercede. By highlighting when student trajectories begin to diverge, this research points to possible mechanisms giving rise to inequities in outcomes and indicates important junctures when students need support. Because the achievement of key academic milestones disproportionately benefits Black and Hispanic students, allocating resources to help students achieve those milestones will likely contribute to narrowing equity gaps in degree attainment. As one example, creating support structures in the first year of enrollment that support Black and Hispanic students to explore available programs and career interests, and choose and enter a program of study early, such as first-year experience courses or exploration embedded in introductory level coursework, may help more students achieve early milestones. Further, currently many community colleges lack information on what programs their students are pursuing. An important first step in helping all students enter, progress through, and complete programs leading to careers that generate family-sustaining wages is that community colleges put structures in place to know which programs students are enrolled in and the average earnings of graduates in each program.

Conclusion

There is a great deal of variation in post-completion labor market opportunity based on what credential students earn, and this study highlights equity issues implicit in that spectrum. It is important to keep in mind that students may choose to enter a program of study for many reasons, of which the earning potential of the resulting credential is just one. Students may choose a program because they are passionate about the subject, or they may feel that a particular degree or certificate will position them to make a meaningful contribution to their community. Given the implications of program choice on prospects for economic mobility, though, it is important that community colleges make students aware of the potential economic consequences of particular programs and types of credentials.

Notes

Due to data availability, the post-completion value of degrees/certificates is classified by students’ immediate post-completion earnings in the six to nine months after exit. Thus, while transfer degrees may lead to high market-valued employment once students transfer and earn bachelor’s degrees, transfer degrees after completion have low immediate market value.

We use a state-wide degree code to identify the transfer-oriented degrees and workforce-oriented degrees, then link them with student program enrollment (degrees and programs share the same CIPs). When some programs are not designated to graduate students with credentials or are unable to link to the specific credentials due to the CIP code errors, the linkage between programs and credentials is missing, making us unable to categorize every program based on the degree code.

In the typical survival analysis, an event is an outcome of interest, such as death, disease occurrence, or recovery. In the survival analysis employed in educational research, an event is usually an educational outcome, such as graduation, transfer, or stop out.

In survival analysis, being "at risk" means that the subject has not experienced an event before time t and is not censored before or at time t.

We include cohort fixed effects in the model to control the cohort-based difference in terms of outcomes.

Despite steadily rising rates of completion, Hispanic students still have low levels of postsecondary attainment; nationally, Black students exhibit lower rates of first-year persistence and higher dropout rates than White students (Espinosa et al., 2019).

In other races/ethnicities, 46% students are Asian, 29% are two or more races, the remaining includes American Indian (7%), Pacific Islander (2%), Native Hawaiian (1%), Alaska Native (less than 1%), and unknown race (17%).

Since very few students transferred or obtained workforce degrees after 6 years, the probability of transfer or completing medium- or high-paying workforce programs becomes extremely small for all racial/ethnic groups. We present the results of transfer and workforce outcomes for only 6 years.

Because the hazard probability of transfer/associate degree completion after 6 years remains statically low, we only track transfer/associate degree completion for 6 years while track students’ bachelor’s degree outcomes for up to 9.25 years.

We define stop out as not being enrolled at any institution for four consecutive terms (1 year). We also use two and three terms as alternatives; the results are robust.

We focus on the outcomes of transfer and BA completion in this section since the share of students completing mid- or high-paying workforce program credentials is small and the results are noisy. Impacts of milestone completion on attaining mid- and high-value workforce credentials are positive for all racial/ethnic subgroups, but we do not observe disproportionate impacts. The full results for the mid- or high-paying workforce degrees are presented in the Appendix.

References

Adelman, C. (1999). Answers in the tool box: Academic intensity, attendance patterns, and bachelor's degree attainment. U.S. Department of Education, National Institute on Postsecondary Education, Libraries, and Lifelong Learning. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED431363

Adelman, C. (2006). The toolbox revisited: Paths to degree completion from high school through college. U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/toolboxrevisit/toolbox.pdf

American Association of Community Colleges. (2021). DataPoints: Enrollment by race/ethnicity. Retrieved from https://www.aacc.nche.edu/2021/12/02/datapoints-enrollment-by-race-ethnicity/

Arcidiacono, P. (2004). Ability sorting and the returns to college major. Journal of Econometrics, 121(1–2), 343–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2003.10.010

Attewell, P., Heil, S., & Reisel, L. (2012). What is academic momentum? And does it matter? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373711421958

Bahr, P. R. (2016). The earnings of community college graduates in California (CAPSEE Working Paper). Columbia University, Teachers College, Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment. https://capseecenter.org/the-earnings-of-community-college-graduates-in-california/

Bailey, T. R., Jaggars, S. S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: A clearer path to student success. Harvard University Press.

Bailey, T., Jeong, D. W., & Cho, S. W. (2010). Referral, enrollment, and completion in developmental education sequences in community colleges. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 255–270.

Baker, R. (2016). The effects of structured transfer pathways in community colleges. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(4), 626–646. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373716651491

Belfield, C. R., & Bailey, T. (2011). The benefits of attending community college: A review of the evidence. Community College Review, 39(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552110395575

Belfield, C. R., & Bailey, T. (2017). The labor market returns to sub-baccalaureate college: A review (CAPSEE Working Paper). Columbia University, Teachers College, Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment. https://capseecenter.org/labor-market-returns-sub-baccalaureate-college-review/

Belfield, C. R., Jenkins, D., & Fink, J. (2019). Early momentum metrics: Leading indicators for community college improvement. Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/early-momentum-metrics-leading-indicators.html

Berger, M. C. (1988). Predicted future earnings and choice of college major. ILR Review, 41(3), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.2307/2523907

Billings, S. B., Deming, D. J., & Rockoff, J. (2014). School segregation, educational attainment, and crime: Evidence from the end of busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 435–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt026

Calcagno, J. C., Crosta, P. M., Bailey, T., & Jenkins, D. (2007). Stepping stones to a degree: The impact of enrollment pathways and milestones on community college student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 775–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-007-9053-8

Carnevale, A. P., Fasules, M. L., Porter, A., & Landis-Santos, J. (2016). African Americans: College majors and earnings. Georgetown University, Center for Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/AfricanAmericanMajors_2016_web.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., Fasules, M. L., Bond Huie, S., & Troutman, D. R. (2017). Major matters most: The economic value of bachelor’s degrees from the University of Texas System. Georgetown University, Center for Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/UT-System.pdf

Castex, G., & Kogan Dechter, E. (2014). The changing roles of education and ability in wage determination. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(4), 685–710. https://doi.org/10.1086/676018

Crisp, G., & Nuñez, A. M. (2014). Understanding the racial transfer gap: Modeling underrepresented minority and nonminority students’ pathways from two-to 4-year institutions. The Review of Higher Education, 37(3), 291–320. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2014.0017

Duncan, G. J., & Murnane, R. J. (Eds.). (2011). Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. Russell Sage Foundation.

Espinosa, L. L., Turk, J. M., Taylor, M., & Chessman, H. M. (2019). Race and ethnicity in higher education: A status report. American Council on Education. https://www.equityinhighered.org/resources/report-downloads/

Fink, J., Myers, T., Sparks, D., & Jaggars, S. (2021). Toward a Practical Set of STEM Transfer Program Momentum Metrics (CCRC Working Paper No. 127). Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/stem-transfer-momentum-metrics_1.pdf

Ginder, S. (2018). Enrollment and employees in postsecondary institutions, fall 2017; and financial statistics and academic libraries, fiscal year 2017: First look (National Center for Education Statistics, 2015-0021). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Statistics.

Holzer H. J., & Xu, Z. (2019). Community college pathways for disadvantaged students (IZA Discussion Paper No. 12319). IZA Institute of Labor Economics. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3390308

Jenkins, D., & Bailey, T. (2017). Early momentum metrics: Why they matter for college improvement (CCRC Brief No. 65). Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/early-momentum-metrics-college-improvement.html

Jenkins, D., & Weiss, M. J. (2011). Charting pathways to completion for low-income community college students (CCRC Working Paper No. 34). Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/charting-pathways-to-completion.html

Jenkins, P. D., & Cho, S. W. (2012). Get with the program: Accelerating community college students' entry into and completion of programs of study (CCRC Working Paper No. 32). Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/accelerating-student-entry-completion.pdf

Jepsen, C., Troske, K., & Coomes, P. (2014). The labor-market returns to community college degrees, diplomas, and certificates. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(1), 95–121. https://doi.org/10.1086/671809

Kopko, E. M., & Crosta, P. M. (2016). Should community college students earn an associate degree before transferring to a 4-year institution? Research in Higher Education, 57, 190–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9383-x

McCormick, A. C. (1999). Credit production and progress toward the bachelor’s degree: An analysis of postsecondary transcripts for beginning students at 4-year institutions (NCES 1999-179). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=1999179

Minaya, V., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2017). Labor market trajectories for community college graduates: New evidence spanning the Great Recession (CAPSEE Working Paper). Columbia University, Teachers College, Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment. https://capseecenter.org/labor-market-trajectories-community-college-graduates/

Monaghan, D. B., & Attewell, P. (2015). The community college route to the bachelor’s degree. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 70–91. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373714521865

Prince, D. (2015). Labor market results of workforce education students (Research Report 15–1). Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges. https://www.sbctc.edu/resources/documents/colleges-staff/research/workforce-research/resh-rpt-15-1-labor-market-results-of-wf-students.pdf

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P., Yuan, X., Nathan, A., & Hwang, Y. A. (2017). Completing college: A national view of student attainment rates by race and ethnicity—fall 2010 cohort (Signature Report No. 12b). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/signaturereport12-supplement-2/

Speer J. (2019, November 9). Bye by Ms. American Science: Women and the leaky STEM Pipeline [Panel paper]. Meeting of the Association of Public Policy Analysis and Management, Denver, CO. https://appam.confex.com/appam/2019/webprogram/Paper31669.html

Stevens, A. H., Kurlaender, M., & Grosz, M. (2019). Career technical education and labor market outcomes evidence from California community colleges. Journal of Human Resources, 54(4), 986–1036.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Table H-8. Median Household Income by State. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html

Vuolo, M., Mortimer, J. T., & Staff, J. (2016). The value of educational degrees in turbulent economic times: Evidence from the Youth Development Study. Social Science Research, 57, 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.12.014

Wang, X. (2017). Toward a holistic theoretical model of momentum for community college student success. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (vol. 32, pp. 259–308). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48983-4_6

Xu, D., Jaggars, S. S., Fletcher, J., & Fink, J. E. (2018). Are community college transfer students “a good bet” for 4-year admissions? Comparing academic and labor-market outcomes between transfer and native 4-year college students. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(4), 478–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1434280

Zafar, B. (2013). College major choice and the gender gap. Journal of Human Resources, 48(3), 545–595. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.48.3.545

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the foundation. We are grateful for excellent feedback from Davis Jenkins, Kevin Dougherty, Elizabeth Kopko, Hana Lahr, and attendees of the 2020 Association for Education Finance Policy Annual Conference and 2021 American Educational Research Association Annual Conference. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the funder or any state entity. Any errors are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Fay, M.P. & Fink, J. Stratified Trajectories: Charting Equity Gaps in Program Pathways Among Community College Students. Res High Educ 64, 547–573 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-022-09714-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-022-09714-7