Abstract

Using large-scale longitudinal data, this study sought to examine factors influencing two important student development outcomes in students with disabilities attending 4-year colleges and universities. Informed by Astin’s Input-Environment-Outcome model and the interactional model of disability, this study investigated the effect of student characteristics (i.e., disability type, gender, mother’s education level) and environmental factors (i.e., faculty encouragement and engagement in political discussion) on the development of academic ability and intellectual confidence in students’ senior year of college. The comparison between two outcome models for students with learning disabilities and those with physical or sensory disabilities provided important educational implications. Results from the multiple regression analyses revealed that both student characteristics and environmental factors significantly affect student development, accounting for students’ academic ability and intellectual confidence upon entering college. Institutional policy implications and educational interventions for college students with disabilities were also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Students with disabilities represent 11% of college undergraduates (U.S. Department of Education 2015), although this number may underestimate their enrollment (Leake 2015). Despite their presence on nearly every higher education campus (Raue and Lewis 2011), evidence indicates that students with disabilities experience lower rates of college adjustment in comparison with peers without disabilities (Adams and Proctor 2010; Murray et al. 2014) and that these marginalized students may experience alienation, stigma, and discrimination that can undermine their developing confidence and academic success (Evans et al. 2017). While institutions of higher education have a responsibility to support the development of all enrolled students, they tend to address the needs of students with disabilities mainly from a perspective of legal compliance (Evans et al. 2017).

Grounded in the Disability Movement, both the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 provide civil rights protections for college students with disabilities and set forth mandates for higher education institutions, influencing the manner in which institutions in America serve college students with disabilities (Raines and Rossow 1994; Thomas 2000). Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act provides protection and alternatives for students with disabilities and applies to all institutions that receive federal dollars (Thomas 2000). While private institutions that do not receive federal funding are exempt from Section 504, the ADA extends civil rights protections to people with disabilities in “all aspects” of public life (Kimball et al. 2016). Thus, almost all institutions of higher education are required to provide students with disabilities equal access to all programs and services together with their classmates without disabilities.

Institutions of higher education are therefore responsible for promoting the development and success of students both with and without disabilities. Two characteristics that are critical to college success, self-concept and self-efficacy, have been shown to grow during students’ time in college (Mayhew et al. 2016). Self-concept refers to a person’s belief about him- or herself, in comparison with his or her peers (Marsh and Seaton 2012). Academic self-concept refers specifically to beliefs students hold about their own academic abilities in comparison to their peers, and is associated with college students’ academic success, including semester grades and achievement testing (Choi 2005; Lent et al. 1997). Self-efficacy, a related construct, refers to a person’s confidence in their own ability to be successful. Academic or intellectual self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their personal academic or intellectual capabilities and is associated with college GPA, persistence, and degree completion (Bong 2012; Vuong et al. 2010). Given evidence suggesting that students with disabilities are at risk for experiencing interactions that undermine academic self-concept (Baker et al. 2012; Hong 2015) and reporting lower levels of self-efficacy (Hen and Goroshit 2014), it is important for higher education institutions to understand the types of positive experiences, such as encouragement from and interactions with faculty or peers, that can foster the development of these characteristics in this minority student group.

To help institutions of higher education better understand how they can support collegiate success among students with disabilities, this study examines factors influencing two important student development outcomes—academic ability and intellectual self-confidence—in students with disabilities attending 4-year colleges and universities, using large-scale longitudinal data. We assume that self-reported academic ability would capture academic self-concept and academic growth, and that intellectual self-confidence measures capture self-efficacy and intellectural growth.

Theoretical Framework

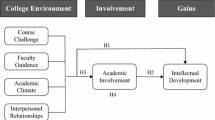

We draw on two theoretical perspectives, Astin’s (1991) model from the field of higher education and an interactional model of disability from the field of disability studies (Shakespeare 2014). Understanding how college affects educational outcomes is essential to improving institutions of higher education. Astin (1991) developed the Input-Environment-Outcome (I-E-O) model for this purpose. In this model, “input” variables refer to characteristics of students as they enter college. The “environment” refers to the college context, which can include institutional characteristics or student experiences while attending college. Finally, “outcome” refers to students’ experiences upon completing college. In the field of higher education, Astin’s I-E-O model is often used for analyzing longitudinal data and tends to be the basic frame of reference for the Higher Education Research Institute’s (HERI) freshman and senior surveys. It is hypothesized that, by accounting for students’ characteristics as they enter college (input), researchers can adequately measure the effect of the college environment on student outcomes.

Astin’s I-E-O model accounts for both individual and environmental influences on student outcomes. Similarly, scholars within the field of disability studies have examined how conceptualizations of disability as influenced by individual impairments or environmental barriers define models of disability that drive institutional policies and social responses. Often, disability is viewed using a medical model, whereby disability is seen as a negative characteristic or a deficit of an individual, and the goal is to intervene or “normalize” the functioning of the individual (Kimball et al. 2017). On college campuses, Offices of Disability Resources (ODRs), which are responsible for ensuring that students with disabilities receive the accommodations and services for which they are legally eligible, have been frequently categorized as representing a medical model of disability. To be deemed eligible for accommodations under the ADA or Section 504, “a person must first provide medical documentation of their physical or mental impairment” (Shallish 2017, p. 21). The social model, on the other hand, distinguishes between impairments (i.e., biological limitations in a person’s functioning) and disability (i.e., limitations in access and inclusion); in the social model, disability is socially constructed when the environment fails to meet the needs of an individual. Disability, therefore, is not caused by impairments but rather by society’s response to those impairments. The social model requires that society break down barriers that prevent people with disabilities from full inclusion (Oliver 2013).

Current policies and practices across higher education institutions often combine elements of a medical model and a social model of disability. While access to disability-related services often requires a medical diagnosis, some institutions are beginning to include disability in their conceptualizations of diversity, through reframing of diversity and inclusion statements or institutional initiatives (O’Neil Green et al. 2017). Arguing that neither the medical nor the social model fully captures the complexity of disability, Shakespeare (2014) developed the interactional model of disability. He stated that the experience of physical impairments cannot be separated from the experience of disability: “Limitations are always experienced as an inter-play of impairment with particular contexts and environments … ‘people are disabled by society and by their bodies’” (p. 75). Specifically, the interactional model of disability acknowledges that the impairment associated with a person’s disability (e.g., slower processing speeds experienced by a student with a learning disability) interacts with environmental contexts (e.g., high volume of reading in a required English class) to impose barriers to a person’s full participation in society. Thus, in developing an understanding of how to cultivate inclusive campus environments, it is important to account for both disability-related and environmental experiences.

Our perspective and analysis in this study are grounded by these interdisciplinary pragmatic models—Astin’s I-E-O model and an interactional model of disability. Although both models account for the influence of personal and environmental factors on students’ experiences and outcomes, it is important to note that each model uses a different yet complementary lens to conceptualize the relationships among these factors. Astin’s I-E-O model emphasizes a linear, longitudinal understanding, by which students arrive on campus with specific characteristics, the college environment promotes or negatively affects the development of some of those characteristics, and graduates depart from campus having grown in knowledge, skills, and those personal characteristics. On the other hand, the interactional model focuses on the influential and/or interactive relationship between a person’s impairment and the social or environmental context in which that impairment occurs. This model recognizes the importance of temporal influences as well as previous and ongoing experiences of stigma and discrimination. As a result, within this framework, the experience of disability is viewed as changing and iteratively influenced by external contexts. By accounting for different disability types within this I-E-O model, we can consider how students’ characteristics as incoming freshmen, including self-reported disability, interact with their experiences in the college environment to affect their outcomes as they complete college.

Student Characteristics

Both Astin’s I-E-O model and the interactional model of disability address the influence of a person’s disability on that individual’s experience. The I-E-O model accounts for student characteristics upon college enrollment, including disability type, gender, and the student’s socioeconomic status. According to the I-E-O model, students enter college with specific demographic characteristics, and these characteristics can affect a student’s experience on campus. Additionally, these experiences may interact to complicate students’ pursuit of college success. Although institutions of higher education often consider students with disabilities in aggregate, students with different disability types have varying needs and therefore experience differing barriers to postsecondary success and growth. Students with apparent disabilities (e.g., sensory disabilities, physical disabilities) and those with disabilities that are less apparent (e.g., learning disabilities) may face distinct challenges within a given college environment. For example, students who perceive their disability to be visible have reported better adjustment to college (Adams and Proctor 2010), but they may experience higher levels of stigma than students with disabilities that are not apparent (Martz 2003). Students with non-apparent disabilities, on the other hand, may prefer not to disclose their disability (Cole and Cawthon 2015) or may encounter faculty who question the student’s need for accommodations (Quinlan et al. 2012).

Learning disabilities are the most prevalent disability type on college campuses, accounting for 69% of students with disabilities (Newman and Madaus 2015). Eighty-four percent of private 4-year colleges and 97% of public universities report enrolling students with learning disabilities (Raue and Lewis 2011). Despite their strong presence in higher education, however, students with learning disabilities may encounter college environments and faculty unequipped to meet their needs. For example, some faculty find it more difficult to meet the needs of students with learning disabilities than those of students with physical disabilities (Ginsberg and Schulte 2008) and believe that students with learning disabilities are less likely to be successful in college than students with physical disabilities (Sniatecki et al. 2015).

In comparison to students with learning disabilities, students with physical disabilities represent only a small proportion (less than 10%) of college students with disabilities (Gelbar et al. 2015). While 90–93% of public universities report enrolling students with mobility or orthopedic disabilities, visual impairments, or those who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, only 50–68% of private 4-year colleges report enrolling students with those disability types (Raue and Lewis 2011). Given the nature of their disabilities, these students require accommodations for physical access to facilities and materials. As a result, students with physical disabilities may prioritize accessibility over programmatic considerations when deciding which college to attend (Wessel et al. 2015).

In addition to acknowledging the varying experiences of students with different types of disabilities, it is important to recognize the intersecting identities of students with disabilities. Within many institutions of higher education, a student registering with the institution’s ODR often becomes defined and identified by their disability (Evans et al. 2017). However, like their peers without disabilities, the experiences of college students with disabilities are also affected by characteristics such as gender identity and identification with a socioeconomic class.

Studies investigating the influence of gender on college participation among students with disabilities have resulted in mixed findings. While some research indicates that females with disabilities enroll in college at higher rates than males (Harvey 2002; Mamiseishvili and Koch 2011), other studies found that gender did not significantly predict college participation (Prince et al. 2018) or that females were less likely to attend 4-year colleges than males (Berry et al. 2012). Once enrolled in college, female students with disabilities require fewer semesters to graduate (Wessel et al. 2009) and graduate at higher rates than men (Jorgensen et al. 2005). Little research has addressed the experience of students with disabilities who identify with genders other than that assigned at birth (Evans et al. 2017).

Students’ socioeconomic status has also been shown to affect college participation among students with disabilities. The preponderance of evidence indicates students with disabilities whose families have higher incomes are more likely to attend college (Harvey 2002; Rojewski et al. 2013). First-generation students with disabilities, who are more likely to come from low-income families (Chen 2005), are significantly more likely to experience financial stress than continuing-generation students with disabilities (Lombardi et al. 2012), and financial concerns contribute to the decision of students with disabilities to discontinue their studies (Thompson-Ebanks 2014).

As suggested by the I-E-O and interactional models, students’ characteristics when they enter college—including disability type, gender, and socioeconomic status—are associated with their academic ability and performance. Given the influence of these characteristics on students’ collegiate experience, it is important that investigations account for such characteristics. The current study not only investigates the effect of disability type, gender, and socioeconomic status on college outcomes, but also accounts for these characteristics to better understand college-specific influences on students’ development.

Growth in Academic Ability

There are several reasons why college students with disabilities may be vulnerable to lower academic self-concept, including academic challenges and disability stigma. While enrolled in college, students with disabilities may have lower grade point averages (Adams and Proctor 2010) and take longer to graduate than their peers without disabilities (Wessel et al. 2009). Experiences of academic challenges may lead to weak academic integration, which is associated with lower intent to persist among students with disabilities (DaDeppo 2009). Disability stigma can also undermine students’ belief in their academic abilities, as students compare themselves to peers without disabilities. Students with disabilities who access disability-related supports and accommodations through an institution’s ODR tend to have higher academic achievement than those who do not make use of those resources (Kim and Lee 2016). However, students may choose not to access ODR services, or to delay access to those services, to avoid negative responses from faculty or peers (Hong 2015; Thompson-Ebanks 2014). An exploration of identity in students with learning disabilities found that those participants who had experienced the highest levels of stigmatization often felt their disability was a weakness that defined their academic sense of self (Troiano 2003). Students with disabilities that are not apparent may choose not to disclose their disability to their classmates, to avoid negative social reactions (Baker et al. 2012). Such experiences of disability stigma may negatively influence students’ perceptions of their personal academic abilities, as they compare their skills with those of their peers.

Academic self-concept is a critical focus in college student development, and, in general, students’ belief in their own academic abilities tends to grow over the course of their college experience (Pascarella and Terenzini 2005; Mayhew et al. 2016). The development of a strong academic self-concept is critical because it has been linked to college achievement (Marsh and Seaton 2012). However, students with disabilities are at risk for lower levels of achievement, making academic self-concept an important target for institutions and faculty supporting students’ success. Our review of related studies reveals a need to investigate factors that institutions of higher eduation can leverage to support the growth of college students’ academic abilities.

Growth in Intellectual Self-Confidence

Students’ confidence in their intellectual abilities is also related to their developing beliefs about their academic abilities. Confidence is closely related to the construct of self-efficacy, which refers to a person’s belief that she or he can accomplish a given task (Bandura 2012). Although the experiences of confidence and self-efficacy are informed by prior experience, evidence suggests that students with disabilities experience lower confidence in their academic abilities, even when they experience the same level of academic success as their peers without disabilities (Hall and Webster 2008). According to Anctil et al. (2008), students with disabilities describe how their accomplishments in college contribute to feelings of confidence and pride. However, self-doubt can also hinder their college success (Hong 2015) and ultimately contribute to decisions to withdraw from college (Thompson-Ebanks 2014). Given that self-efficacy has been associated with higher college graduation rates among students with disabilities (Fichten et al. 2014), it is important to understand how institutions and faculty can foster the development of students’ confidence in their intellectual capabilities. Existing studies have little information on influential factors related to the growth of intellectual self-confidence among students with disabilities.

College Environment and Experiences

While students enter college with a variety of backgrounds and characteristics, their college experiences influence their developing confidence and academic abilities, and students who have higher levels of engagement show greater benefit from their college experiences (Kuh 2007). Research investigating the college experiences of students with disabilities often focuses on the use of disability-related services and accommodations or students’ academic achievement (Kimball et al. 2017).

College students with disabilities engage in enriching college activities at rates similar to those of their peers without disabilities (Hedrick et al. 2010; Hendrickson et al. 2015), indicating a need to better understand how such experiences affect the development of students with disabilities. For example, among the general college student population, having discussions with peers about diversity or coursework is related to the development of habits of mind that support college success and lifelong learning (Hurtado and DeAngelo 2012). However, little is known about how the participation and engagement of students with disabilities in campus activities affects their growth and development.

Interaction with faculty is also a measure of student engagement that affects students’ college experiences. Evidence suggests that faculty can both facilitate and present barriers to the success of college students with disabilities (Scott 2019). Although quantitative studies focusing on the frequency of faculty interactions have found small to no effects on college persistence for students with disabilities (Mamiseishvili and Koch 2011), qualitative findings indicate that the quality of those interactions is critical (Thompson-Ebanks 2014). While most faculty report that they are accepting of students with disabilities and that their campus climate is positive (Baker et al. 2012; Murray et al. 2008; Sniatecki et al. 2015), students may not have the same perceptions. Students might interact with some faculty members who think that accommodations provided for students with disabilities constitute an unfair advantage (Stevens et al. 2018). Studies on college barriers reported that some participants had negative experiences with faculty members (Fleming et al. 2017; Hong 2015) and problems with faculty accommodation of their needs (Cole and Cawthon 2015).

Faculty and student affairs professionals may lack training and an understanding of how to effectively support students with disabilities (Kim and Williams 2012; Lombardi and Lalor 2017; Vaccaro and Kimball 2017). Surveys conducted at single institutions have indicated that 48–67% of university faculty and staff are unfamiliar with the ADA or Section 504 (Dallas and Sprong 2015; Murray et al. 2008). Fortunately, disability training of any intensity or delivery method (e.g., online) has been linked with promoting positive changes in faculty perceptions and knowledge (Lombardi et al. 2013). As Jenson et al. (2011) stated, “Instructors set the tone for learning and consequently highly influenced students’ confidence, motivation, anxiety, and stress—and ultimately—success” (p. 279). Yet despite qualitative evidence suggesting the importance of supportive faculty interactions in students’ college development, no large data-based quantitative study has investigated the effect of faculty encouragement on the growth of students with disabilities.

Together, the differing experiences of students with disabilities, the influence of the institutional environment, and the implications of college student outcomes suggest a need to better understand how these characteristics and environments contribute to the development of students’ academic ability and intellectual confidence. Research focused on students with disabilities is under-represented in influential journals of higher education (Peña 2014), and research published in journals dedicated to disability services in postsecondary education has been predominantly descriptive, with limited attention to the contribution of faculty or general college experiences to the development of college students with disabilities (Madaus et al. 2014). Additionally, there is a need for research that uses national data sets (Avellone and Scott 2017; Kimball et al. 2016), considering that many studies reflect experiences at a single institution. The current study addresses these identified gaps in the literature by using a large, national data set to investigate the effects of college engagement experiences on the development of academic ability and intellectual confidence among students reporting different disability types.

Data, Variables, and Methods

Considering our research purpose, the existing literature, and the research gaps, we sought to address the following research questions:

-

Research question 1. How do students with different demographic characteristics (e.g., disability type, gender) vary in perceived academic ability or intellectual self-confidence?

-

Research question 2. How do demographic characteristics and pretest measures predict and interact with perceived academic ability or intellectual self-confidence?

-

Research question 3. How do faculty’s encouragement to pursue graduate or professional study and students’ engagement with peers or others concerning politics affect their intellectual self-confidence or academic ability development?

Data and Sample

We conducted analyses using data from the HERI 2004 and 2006 freshman and senior surveys. We combined two longitudinal data sets—two freshman (i.e., Freshman Survey [TFS] 2004 and 2006) and follow-up survey data (i.e., College Senior Survey [CSS] 2008 and 2010). These surveys are based on students’ self-reports; this should be taken into consideration in the interpretation of the statistical results. The HERI data set, however, offers advantages over other national data because it is one of the longitudinal national data sets explicitly designed to investigate how college affects students, using Astin’s I-E-O model (HERI 2019).

We started this study using all available student cases, including all types of disabilities (N = 1533). Most participants identified as having a physical or sensory disability (N = 549), followed by those reporting a learning disability (N = 532), a health-related disability (N = 233), and other disability (N = 219). This study recognizes the heterogeneity of students with physical or sensory disabilities and those with learning disabilities, but students reporting health-related or other disabilities encompass an even broader range of disability characteristics. Therefore, we started statistical analyses with all disability groups and then decided to conduct the regression analyses with two collapsed categories. Given the variability of disability types that could be included among individuals with health-related or other disabilities, as well as the smaller sample sizes, we chose to focus on the 1081 respondents in the learning, physical, or sensory disability categories, particularly for bivariate and multiple regression analyses. Among students with learning, physical, or sensory disabilities in the HERI data, many more females (632) than males (449) reported having a disability, in contrast with data at the high school level—where 66% of students with disabilities are male (National Center for Education Statistics 2018). The distributions across gender categories were comparable for students with (a) physical or sensory disabilities and (b) learning disability (see Table 1).

Within this sample, students with disabilities generally attended smaller universities and colleges, with only 15% attending large universities and 85% attending smaller 4-year universities. However, it is important to note that the HERI data is national-scale but not a nationally representative sample. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether students with disabilities choose smaller colleges or if this finding represents the types of institutions electing to participate in this survey. However, it provides some insights into where students with disabilities can persist or graduate after 4 years.

To examine student development among students with disabilities (particularly between physical/sensory and learning disability groups), we applied the logic of Astin’s I-E-O model to the longitudinal data from HERI, defining input characteristics as those reflected on pretests upon college entry; students’ activities or experiences with their professors or other students are considered to reflect the college environment. Self-reported outcome measures in students’ senior year (i.e., responses on the 4-year follow-up survey) become the outcomes. We chose Astin’s I-E-O model as the conceptual framework for this study because it allowed for an understanding of disability that encompasses the interaction of personal characteristics and environmental factors.

Variables

Dependent Variables

Academic ability and intellectual self-confidence served as the dependent variables in this analysis and were measured during participants’ freshman and senior years (repeated after 4 years). These variables were operationally defined on the basis of participants’ responses to the following item: “Rate yourself on each of the following traits as compared with the average person your age. We want the most accurate estimate of how you see yourself.” Participants could rate themselves as: (1) among the lowest 10%; (2) below average; (3) average; (4) above average; or (5) among the highest 10%. Our univariate analysis shows that student responses tended to concentrate between three and four on the five-point scale. While the five-point, Likert-like scale is not continuous, we treated it like an interval scale to conduct the standard, multiple regression analysis with large data. We can see additional construct validity through strong correlation between college GPA and senior-year responses to academic ability on a Likert scale (r = 0.49; see the bivariate analysis section of results). Most studies based on HERI data were executed and presented in the same way (e.g., Astin 1991; Kim 2002).

Independent Variables

We included five student and environmental characteristics as independent variables. Student characteristics included disability type, gender, and mother’s education level; environmental characteristics included faculty interaction and student engagement variables. An important independent variable in the regression models was disability type (coded as learning = 2 vs. physical or sensory disability = 1). To ensure a sufficient sample size for analyses, we combined individuals reporting orthopedic or sensory disabilities into one sample of students with “physical or sensory disabilities.” Participants in the physical or sensory disability group could self-identify as having an orthopedic disability or a sensory disability (including d/Deafness, hearing impairment, blindness, or visual impairment).

About 3.8% of the total sample selected multiple disabilities. Participants in the learning disability and physical or sensory disabilities samples could report a co-occurring health-related or other disability. However, participants reporting a learning disability as co-occurring together with an orthopedic or sensory disability were excluded from this analysis to differentiate the effects between these groups.

As measured in the HERI data set, female was a dichotomous variable (coded as being female = 2 vs. being male = 1). Female status at the entrance stage was used as part of the multiple regression models and other bivariate analyses. It served to capture the intersectionality of marginalization (i.e., female and person with a disability) as well as helping to understand the interactions between being female and other variables. In the 2004 and 2006 TFS survey versions, participants were not given the option of selecting a gender identity other than that of male or female.

We included mother’s education level (similar to father’s education level) to account for students’ varying backgrounds and access to resources prior to beginning college. Participants responded to the question “What is the highest level of formal education obtained by your parents?” on a scale of one to eight (1 = grammar school or less, 2 = some high school, … 6 = college degree, 7 = some graduate school, 8 = graduate degree). Race (i.e., white vs. non-white) was not a contributing variable in any model; therefore we removed it.

Beyond the research synthesis (e.g., Pascarella and Terenzini 2005; Scott 2019), our practical experience suggests that faculty’s active support is important for students’ academic and intellectual growth. We included a related faculty variable (faculty’s encouragement to pursue graduate studies) in the regression models. The variable was measured on the 3-point scale (not at all = 1; frequently = 3).

Finally, student activity and/or involvement are important concepts for academic and other aspects of student growth (Astin 1996; Kuh 2007). Following the example of prior studies using HERI data (Hurtado and DeAngelo 2012), we included multiple student activity models in our exploratory analyses of the data and retained only the significant variables for our final models. In the current study, only students’ experience of “discussed politics” was retained, because the other survey items (e.g., student–faculty interaction, worked part-time, peer orientation) did not meet a threshold of p ≤ 0.20 after controlling for background characteristics and pretest measures. “Discussed politics” was part of student activities measures (i.e., “For the activities below, indicate which ones you engaged in during the past year”) in the survey and was measured on a three-point scale (1 = not at all; 2 = occasionally; 3 = frequently).

Limitations

Quantitative studies are rare on the topic of disabilities, and using the national longitudinal data is a strength of this study. Nonetheless, that strength can be a limitation of this study, particularly because HERI surveys are not tailored for students with various disabilities, and this study had to be designed within the available variables and scale of the variables. The use of longitudinal “combined” surveys (i.e., 2004 and 2006 freshman data) is also this study’s unique strength because it doubles the number of students, although some might criticize it for the differences between two entering student groups. Still, we believe that the strengths and merits exceed the student group differences. Additionally, in order to support our comparison of experiences, we included students who reported disabilities within two categories; therefore, results cannot be generalized to students with any disability type and may not reflect the experiences of students reporting both learning and physical or sensory disabilities. Future research may address some of these limitations. Finally, the above variable section suggested potential limitations regarding the three- to five-point scales of HERI data as a caveat for the reader’s interpretation.

Procedures

We began our analysis by examining the results of univariate analysis and bivariate correlation analysis, followed by multiple regression analysis. We present regression analyses to introduce different sets of variables to lead three different blocks and models, applying Astin’s simple I-E-O logic. Although the pretests (freshman survey responses of academic ability and intellectual self-confidence) can be part of inputs, we separated them from the rest of the demographic characteristics at the entering stage, which allowed us to understand the net effects of pretests or demographic characteristics such as disability types, being female, and mother’s education. For the multiple regression analyses, we included the same variables to support comparability of the models, although the models are capturing different constructs.

We used multiple regression analyses to answer the overarching research question:

How do student characteristics and college experiences predict the development (or senior-year self-evaluation) of academic ability and intellectual self-confidence among students with physical/sensory and learning disabilities during college?

For research questions 1 and 2 (related to demographic characteristics), we were particularly interested in differences between the experiences of students with “learning disabilities” and those with “physical or sensory disabilities.” We conducted analyses for a sample of students with self-reported learning disabilities and those reporting physical or sensory disabilities, using senior-year academic ability and intellectual self-confidence as our dependent variables or outcomes.

For each outcome (i.e., academic ability and intellectual self-confidence), we created three sub-models, using the same independent variables. Model 1 included three control variables: gender (female vs. male), mother’s education (parental SES indicator), and disability type (learning vs. physical/sensory disabilities). Model 2 included all the variables in Model 1 plus the pretest measure of the respective outcome variable in the student’s freshman year (4 years prior to the senior-year response). This allowed us to account for differences in academic ability or intellectual confidence beyond those reflected in students’ incoming status or perception. Finally, Model 3 was the full model, including variables reflecting both faculty support and student engagement (i.e., faculty’s encouragement to pursue graduate studies; discussed politics). The hypothesis testing was done at the p = 0.10 level. However, this study also presents the significance level at p = 0.05 and p = 0.01 levels for those who prefer to use more conservative p-levels.

Results

Bivariate Correlation Analysis

Some correlation coefficients reveal important information to this study. Learning disability (disability type) and being female had moderate negative correlations with both outcomes, while the correlation between mother’s education level and outcomes (the academic ability or intellectual self-confidence at the senior year) is relatively weak or minimal. (See Tables 2, 3 and 4) Interestingly, being female and having a learning disability (vs. a physical-sensory disability) had a zero correlation, a pattern consistent with Table 1, the numbers (ratios) of male vs. female students with learning disability vs. physical or sensory disability types. Virtually no gender distribution difference with these disability categories was observed in this HERI data set.

Not shown in the Tables, the correlation between the pretest and posttest of academic ability is 0.49, while the correlation between the pretest and posttest of intellectual confidence is 0.41. The correlation between the academic ability measure and the intellectual self-confidence measure, both at the senior year, is relatively strong (r = 0.43). The correlation between college GPA and the academic ability measure at the senior year is 0.49. This relatively strong correlation coefficient between GPA and perceived academic ability also suggests the validity of using self-reported academic ability, which can also be used as a growth indicator, especially due to the nature of longitudinal data. On the other hand, the correlation between intellectual self-confidence at the senior year and college GPA is weak (r = 0.15). Therefore, we assume that intellectual self-confidence captures a distinct construct.

Multiple Regression Analysis

The results of the multiple regression analyses are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Findings related to our specific research questions follow.

Research Question 1

How do students with different demographic characteristics (e.g., disability type, gender) vary in perceived academic ability or intellectual self-confidence?

Overall, students with learning disabilities appear to rate their academic ability and intellectual self-confidence as significantly different from the ratings that students with physical-sensory disabilities report in their senior year or after 4 years of college education in Model 1. However, the effect of disability type on intellectual self-confidence dramatically changed (the effect ceased to be significant and even showed a sign change from negative to positive) from Model 1 to Model 3, as shown in Table 4.

As described earlier, being female, disability type (learning vs. physical or sensory), and mother’s education level were established in the first sub-model (before the pretest was introduced). The results indicated that male students with disabilities showed higher levels of perceived academic ability and intellectual self-confidence as seniors than female students. Being female was a strong negative predictor for all sub-models of intellectual self-confidence; the significant coefficient drop in Model 2 suggests that the reason for the negative effect is largely attributed to females’ low self-confidence at the freshman stage or to the experience of gender difference prior to college. (See Tables 2, 3 and 4) Female students appear to have more barriers, or they are likely to have a slower growing experience during college.

Not shown in Tables, we conducted mean comparison tests (t-tests). Overall, students with a learning disability rated lower than those with a physical or sensory disability in both outcomes. The mean difference for academic ability at the senior year was significant (4.04 vs. 3.70, p < 0.01), and that for intellectual self-confidence was also significant (3.83 vs. 3.71, p < 0.05). However, the small difference (0.12) in intellectual self-confidence might not be practically significant. Notably, at the freshman year, the gaps between learning and physical or sensory disability were somewhat wider (4.08 vs. 3.58 for academic ability, p < 0.01; 3.75 vs. 3.47 for intellectual self-confidence, p < 0.01); on average, the gaps decreased over 4 years, owing especially to the average score improvement among the learning disability group. Similarly, female students with disabilities also rated lower than males on both outcome measures; the mean differences were statistically significant (3.99 vs. 3.86 for academic ability, p < 0.01; 3.93 vs. 3.69 for intellectual self-confidence, p < 0.01).

Research Question 2

How do demographic characteristics and pretest measures predict and interact with perceived academic ability or intellectual self-confidence?

Growth in Academic Ability

The regression analysis showed that student characteristics had an effect on academic ability development. Having a learning disability had a strong negative effect even when other demographic variables were held constant, but its effect decreased significantly when the freshman-year academic ability was held constant in Model 2. Its negative effect persisted throughout the models. (Note changes in beta from − 0.246, Model 1 to − 0.088, Model 2.)

The gender effect was shown in both academic ability and intellectual confidence models. However, for academic ability, the negative effect of being female dropped to insignificant when controlling for the initial academic ability rating, which suggests women students with disabilities might encounter more difficulties from their early schooling stage than their male counterparts. This suggests the necessity of early intervention efforts for female students with disabilities.

Additionally, the higher their mother’s education level, the more likely students with physical and learning disabilities are to develop their academic ability during college, even when controlling for the initial academic ability rating and other influential demographical and college experience factors. Table 3, presenting three models of academic ability outcome, notes that the coefficient size of mother’s education dropped continuously as more variables were included in Model 2 and Model 3, which suggests that mother’s education level might have a notable influence on students with disabilities and their learning activities and experiences. In the studies of general student populations, the father’s education tends to have a stronger effect than the mother’s. For this sample, father’s education level was not a significant predictor in any outcome. This unique effect of mother’s education implies some unexplained roles that mothers play for their children with disabilities, but further speculation on this result is beyond our data and research.

Growth in Intellectual Self-Confidence

Students with learning disabilities reported slower development of intellectual self-confidence than students with physical or sensory disabilities. Given that the diagnosis of a learning disability often involves the completion of intelligence tests (Weis et al. 2012), it is possible that the diagnosis process undermines the confidence students with learning disabilities have in their own intellect. While the differential effect or negative direction is not necessarily surprising, future studies should further investigate reasons for the differences.

The regression analysis also indicated that student characteristics affected participants’ growing intellectual self-confidence. As with findings regarding development of academic ability, results showed that females reported lower growth in intellectual self-confidence than males. The negative effect of being female is especially notable, particularly given that the higher proportion of the follow-up survey respondents was female. This indicates that female college students with disabilities begin college with lower intellectual self-confidence than their male peers, and this gap widens during the college years.

In contrast to the academic ability outcome, mother’s education did not predict intellectual self-confidence in Model 1. However, the b (or beta) coefficient of mother’s education changed from the insignificant level to the significant level upon the inclusion of pretest (Beta, from − 0.027 to − 0.061, p < 0.05 in Model 2), which suggests the relationships between mother’s education and the participants’ activities and experiences prior to and during college. There might be a suppressor effect needing further investigation in future studies.

Pretest Effects and Contributions

The pretest is the most powerful predictor for each outcome; the standardized b (beta) for intellectual self-confidence is 0.416 (p < 0.01) in Model 2, controlling for background characteristics, and that for academic ability is 0.461 (p < 0.01) in Model 2. For intellectual self-confidence, Model 2 (the addition of pretest) demonstrates 16% of change in the total variance. As for academic ability, Model 2 demonstrates 19% of change in variance. Both coefficients slightly dropped in Model 3 (academic ability, 0.387; intellectual confidence, 0.421), suggesting pretests’ shared predictability with two faculty and college experience variables.

Research Question 3

How do faculty’s encouragement to pursue graduate or professional study and student engagement with peers or others concerning politics affect their intellectual self-confidence or academic ability development?

Faculty and student activity variables are strong and notable. Both students’ engagement in discussions of politics and faculty’s encouragement to pursue graduate studies were positively related to academic ability and intellectual self-confidence variables. These two variables in Model 3 increased 4% of variance for intellectual self-confidence and 5% of variance for academic ability, controlling all other variables in each outcome model.

Growth in Academic Ability

The faculty factor, encouragement to pursue graduate study, is positive and significant (beta = 0.184, p ≤ 0.01 in Model 3) in students’ self-ratings on the development and status of academic ability. The same pattern is shown with students’ involvement in discussion of politics (discussed politics: beta = 0.112, p ≤ 0.01). Such discussions require substantial reading and reflection on politics, the world, and social orders and norms; this mental engagement might lead students with disabilities to be more intellectually competent and confident.

Growth in Intellectual Self-Confidence

Faculty’s encouragement (to pursue graduate or professional study) also mattered for students’ intellectual self-confidence (beta = 0.144). Discussion of political issues might have the effect of boosting intellectual development, subsequently developing more self-confidence (beta = 0.112, p ≤ 0.01).

Overall, no multicollinearity was found in any of the models, based on VIF and Tolerance tests, and all models fit relatively well. With only six independent or predictor variables in each outcome, the model explanations or fits are considered parsimonious, with 23% and 31% of total variance explained for intellectual self-confidence and academic ability, respectively.

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of student and environmental characteristics on the development of academic ability and intellectual confidence. Findings with regard to student characteristics revealed meaningful differences in the outcomes of students with differences in disability type, gender, or mother’s education level. At the same time, consistent with the logic of Astin’s I-E-O model and the interactional model of disability, the results of the regression analyses indicate that college environment factors, including encouragement from faculty and engagement in political discussions, can significantly affect students’ development of academic ability and intellectual self-confidence.

We sought to examine the differences between students with learning vs. physical and sensory disabilities in the growth of academic ability and intellectual self-confidence. Students reporting physical disabilities and those reporting sensory disabilities were similar in number to those reporting a learning disability. Consistent with previous findings (Newman and Madaus 2015), students with a learning disability constituted the largest proportion of college students with disabilities, as shown in Table 1.

The comparison between two outcome models for students with learning disabilities and those with physical or sensory disabilities provides important educational and practical implications. As shown in Table 3, learning disability seems to be a significant and negative predictor for the development of academic ability across all three sub-models, which might not be surprising, because the diagnostic measure of learning disability is directly related to prior school or academic performance before college. On the other hand, students with a learning disability tended to start with low self-confidence, but it was not a barrier to growth in intellectual confidence once their pretest confidence level was held constant, and the insignificant positive effect was maintained in both Models 2 and 3.

Model 1 in both outcomes shows that female students with disabilities may be at risk for arriving at campus with lower levels of belief in their academic ability and lower intellectual confidence. Being female was a negative predictor throughout the models in both outcomes, and its negative effect dropped significantly once the pretests were held constant. The negative effect of being female was statistically significant in their intellectual confidence after 4 years of college, although its negative effect ceased to be significant in academic ability. Being a female student with a disability might be a greater barrier on US campuses due to their multiple or cross-sectional minority status in terms of social stratification, barriers, and power, compared with males or students without diabilities. Perhaps interventions should begin at the high school level, and educators and administrators should consider various programs and support that can help these students build their confidence. In addition, it is unclear whether women’s lack of self-confidence results from disabilities or their limited opportunities. Because the higher proportion of respondents are female, it can be speculated that female students with disabilities might be more likely to persist in their education than male counterparts, and/or they might be more likely to respond to surveys. Prior research suggests that female students with disabilities are more likely than males to attend and persist in postsecondary studies (Jorgensen et al. 2005; Wessel et al. 2009). However, findings of this study indicate that female students may still be vulnerable to lower intellectual self-confidence. Therefore, future studies should further investigate gender differences, as well as the experiences of female students with different disabilities.

Findings about faculty’s encouraging pursuit of graduate school suggest that communicating high academic expectations for students with disabilities could not only enhance their confidence level, but could also promote their academic ability regardless of the types of disability. This faculty support variable has more unique and positive contributions to Model 3 for both outcomes than other variables, except for the pretest measures. This faculty encouragement variable has a negative correlation with students with learning disabilities (r = − 0.065, p ≤ 0.05, Table 2). Future studies should explore faculty support factors more thoroughly and encourage faculty’s direct involvement with students with learning disabilities outside of the classroom. Still, faculty’s encouraging pursuit of graduate school captures a very limited dimension of faculty support for college students, and future studies should look for more extensive faculty support data.

Related to findings on “discussed politics,” most college students begin exercising their voting right as adult citizens, and some students discover themselves or form their identity in the context of society and political discourse during college. Such discussions can evolve into intellectual dialogues and reflection—which can also be related to students’ engagement with their peers or with anyone regarding their views of the world and ideas, or debates on society and politics. Professors and administrators should be mindful of students’ identity formation as well as critical-thinking-skill development through students’ political debates and activities. They should also ensure opportunities for students with diverse disabilities to be actively involved in politics (e.g., voter registration, political speakers) and make sure student governance on campus is accessible to students with disabilities.

The overall patterns of predictors seem to be consistent with or similar to college impact studies in general (e.g., Pascarella and Terenzini 2005; Mayhew et al. 2016). Such findings have implications for the structure of higher education. As discussed previously, institutions of higher education often address the needs of students with disabilities from a perspective of legal compliance (Evans et al. 2017). DROs, tasked with upholding students’ rights to reasonable accommodations, operate in a silo and have limited interaction with other student engagement offices (Shallish 2017). The findings of the current study indicate that students with disabilities benefit significantly from the same types of experiences as their peers without disabilities, suggesting a need to challenge institutional structures that view students’ developmental needs primarily from the perspective of their disability. Faculty’s encouragement or student engagement in political discourse can help any student’s development of academic ability and intellectual confidence. Universities must take steps to ensure that such opportunities for engagement are accessible to students with disabilities, as well as to those without disabilities. For example, institutions should provide faculty training to combat disability-related stigmas and to support faculty professional development in effectively meeting the needs of their students (Lombardi et al. 2013). Further, when planning student engagement events, such as opportunities for political debate, institutions should consider the physical accessibility of the spaces where such events are held, ensuring that students with physical or sensory disabilities do not experience barriers to participation.

Despite the fact that these findings are consistent with college student development in general, this study involving students with disabilities makes several unique contributions. First, findings regarding female students’ lower confidence levels upon entering college highlight the complexity of students’ intersecting identities and potential multiple marginalizations. Furthermore, female and male students experienced different types of growth in confidence during their college years, and the gap did not close, indicating that more targeted developmental support is necessary for female students with disabilities.

Second, more generally, this study focusing on students with disabilities offers insights into how college environmental characteristics can support students’ experience and engagement to promote positive outcomes. In contrast with other student groups, students with disabilities can experience social and physical barriers to participation due to inaccessible spaces or the realities of living with a disability. Therefore, understanding the experiences that promote positive outcomes for this group of students, who may find themselves unable to participate in college experiences in the same ways as their peers, may inform our understanding of possible support for other marginalized student groups.

Some interesting patterns from our results warrant additional investigation. Given the design of this study, it was not possible to determine why the discussion of political topics was related with participants’ outcomes. The strong positive effect of engagement in the discussion of political topics might be linked to their academic disciplines or potentially limited social activities, compared with those of the general population of students or students without disabilities. Future studies should investigate these engagement or activity variables, considering academic majors and disability types.

It might not be surprising to see parental education level as a significant predictor for student academic outcomes. Nonetheless, during our modeling process, mother’s education level was a significant predictor for the growth in academic ability, but father’s education was not, adjusting for other factors in Model 1. It is possible that mothers spend more time and effort to aid their children’s learning than fathers, particularly among students with disabilities; this may be due to the critical role mothers play in advocating for their children with disabilities (Ryan and Runswick-Cole 2008). The b coefficient changes of mother’s education in both outcomes suggest that highly educated mothers are more likely to influence these students’ lives prior to and during college. While this change pattern might be intuitive to mothers who raise children with disabilities, it alerts the disability service professionals and faculty to further investigate mothers’ (parental) involvement, particularly for the academic growth and success of students with a disability. The effect of mother’s education indirectly suggests how parental socioeconomic status (SES) factors continue to play an important role in academic success of college students with disabilities.

According to Wessel et al. (2015), given the lack of universally available support for college students with disabilities, prospective students tend to choose an institution on the basis of the accessibility offered by large public universities rather than programmatic considerations. Eighty-five percent of participants in this study, however, attended relatively smaller institutions. Because of the nature of the longitudinal data, this pattern raises the question of whether students with learning, physical, and sensory disabilities might be more likely to persist and succeed in smaller institutions. It is possible that small colleges and universities are more receptive to providing students with disabilities with support and experiences to enhance their development, even though large institutions may be better equipped with physical and human resources. Future research should expand the study of academic and intellectual development (including other educational outcomes) among students with disabilities by investigating the institutional contextual factors such as size, location, various types and degrees of accommodation provision, and campus culture.

Conclusion

This study, using the longitudinal data from HERI, aimed to investigate student characteristics and environmental factors influencing the development of (a) academic ability and (b) intellectual self-confidence among college students with learning, physical, and sensory disabilities. Findings revealed both consistent and different patterns among the same set of independent variables between two outcome models, and discussed the different effects between learning disability and the combined category of physical and sensory disability, as well as the negative effect of being a female student with a disability.

Some of the findings are encouraging for educators and administrators in colleges and universities. In particular, the strong, positive effect of experiences with political discourse or faculty encouragement suggests that institutions of higher education and their faculty should make every effort to accommodate the needs of students with disabilities and encourage them to pursue their goals, including political debates, leadership opportunities, or graduate schools.

This study has raised questions that should be addressed in future research to inform theories and practices regarding students with disabilities in higher education. The “E” of Astin’s I-E-O model focuses attention on the college environment and experiences. In this study, however, the significant effect of mothers’ education level on students’ academic ability is notable even after accounting for incoming academic ability. This could suggest the necessity of paying special attention to first-generation students with disabilities or parental involvement in terms of broad policy perspective. This finding warrants additional discourse and investigation to better understand how variables outside of the college setting can also influence students’ experiences to yield positive or negative educational outcomes.

Finally, our regression analysis reveals that there is no difference in growth in self-confidence between learning disability and physical and sensory disability groups, once their difference at the entering stage is adjusted or removed. Building students’ confidence could mean that we are engaging in building the foundation of lifelong education. Although students with disabilities may enter college at risk for lower outcomes, colleges can cultivate environments in which students with disabilities develop their intellectual confidence and academic ability on an equal footing with their peers, allowing them to maximize their life skills, self-actualization, and personal quality of life.

References

Adams, K. S., & Proctor, B. E. (2010). Adaptation to college for students with and without disabilities: Group differences and predictors. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 22(3), 166–184.

Americans With Disabilities Act [ADA] of 1990, Public Law No. 101–336, 104 Stat. 328, (1990).

Anctil, T. M., Ishikawa, M. E., & Scott, A. T. (2008). Academic identity development through self-determination successful college students with learning disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 31(3), 164–174.

Astin, A. W. (1991). Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment and evaluation in higher education. New York: American Council on Education/Macmillan.

Astin, A. W. (1996). Involvement in learning revisited: Lessons we have learned. Journal of College Student Development, 37(2), 123–134.

Avellone, L., & Scott, S. (2017). National databases with information on college students with disabilities. NCCSD Research Brief, 1(1). Huntersville, NC: National Center for College Students with Disabilities, Association on Higher Education and Disability. http://www.NCCSDonline.org.

Baker, K. Q., Boland, K., & Nowik, C. M. (2012). A campus survey of faculty and student perceptions of persons with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 25(4), 309–329. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1647134

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44.

Berry, H. G., Ward, M., & Caplan, L. (2012). Self-determination and access to postsecondary education in transitioning youths receiving Supplemental Security Income benefits. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 35, 68–75.

Bong, M. (2012). Self-efficacy. In J. Hattie & E. Anderman (Eds.) International guide to student achievement. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Chen, X. (2005). First generation students in postsecondary education: A look at their college transcripts (NCES 2005–171). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Choi, N. (2005). Self-efficacy and self-concept as predictors of college students’ academic performance. Psychology in the Schools, 42(2), 197–205.

Cole, E. V., & Cawthon, S. W. (2015). Self-disclosure decisions of university students with learning disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(2), 163–179.

DaDeppo, L. M. (2009). Integration factors related to the academic success and intent to persist of college students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 24(3), 122–131.

Dallas, B. K., & Sprong, M. E. (2015). Assessing faculty attitudes toward Universal Design instructional techniques. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 46(4), 18–28.

Evans, N. J., Broido, E. M., Brown, K. R., & Wilke, A. K. (2017). Disability in higher education: A social justice approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fichten, C. S., Nguyen, M. N., Amsel, R., Jorgensen, S., Budd, J., Jorgensen, M., et al. (2014). How well does the theory of planned behavior predict graduation among college and university students with disabilities? Social Psychology of Education, 17(4), 657–685.

Fleming, A. R., Oertle, K. M., & Plotner, A. J. (2017). Student voices: Recommendations for improving postsecondary experiences of students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 30(4), 309–326.

Gelbar, N. W., Madaus, J. W., Lombardi, A., Faggella-Luby, M. N., & Dukes, L. (2015). College students with physical disabilities: Common on campus, uncommon in the literature. Physical Disabilities: Education and Related Services, 34(2), 14–31.

Ginsberg, S. M., & Schulte, K. (2008). Instructional accommodations: Impact of conventional vs. social constructivist view of disability. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 8(2), 84–91. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854849.pdf

Hall, C. W., & Webster, R. E. (2008). Metacognitive and affective factors of college students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 21(1), 32–41.

Harvey, M. W. (2002). Comparison of postsecondary transitional outcomes between students with and without disabilities by secondary vocational education participation: Findings from the National Education Longitudinal Study. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 25(2), 99–122.

Hedrick, B., Dizen, M., Collins, K., Evans, J., & Grayson, T. (2010). Perceptions of college students with and without disabilities and effects of STEM and non-STEM enrollment on student engagement and institutional involvement. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 23(2), 129–136.

Hen, M., & Goroshit, M. (2014). Academic procrastination, emotional intelligence, academic self-efficacy, and GPA: A comparison between students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(2), 116–124.

Hendrickson, J. M., Therrien, W. J., Weeden, D. D., Pascarella, E., & Hosp, J. L. (2015). Engagement among students with intellectual disabilities and first year students: A comparison. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 52(2), 204–219.

Higher Education Research Institute [HERI]. (2019). CIRP Freshman Survey. Retrieved from https://heri.ucla.edu/cirp-freshman-survey/

Hong, B. S. (2015). Qualitative analysis of the barriers college students with disabilities experience in higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 56(3), 209–226.

Hurtado, S., & DeAngelo, L. (2012). Linking diversity and civic-minded practices with student outcomes. Liberal Education, 98(2), 14–23. Retrieved from https://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/Linking-Diversity-and-Civic-Minded-Practices-with-Student-Outcomes.pdf

Jenson, R. J., Petri, A. N., Day, A. D., Truman, K. Z., & Duffy, K. (2011). Perceptions of self-efficacy among STEM students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24(4), 269–283.

Jorgensen, S., Fichten, C. S., Havel, A., Lamb, D., James, C., & Barile, M. (2005). Academic performance of college students with and without disabilities: An archival study. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 39(2), 101–117.

Kim, M. M. (2002). Cultivating intellectual development: Comparing women-only colleges and coeducational colleges for educational effectiveness. Research in Higher Education, 43(4), 447–481.

Kim, M. M., & Williams, B. C. (2012). Lived employment experiences of college students and graduates with physical disabilities in the United States. Disability & Society, 27(6), 837–852.

Kim, W. H., & Lee, J. (2016). The effect of accommodation on academic performance of college students with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 60(1), 40–50.

Kimball, E., Friedensen, R., & Silva, E. (2017). Engaging disability: Trajectories of involvement for college students with disabilities. In E. Kim & K. C. Aquino (Eds.), Disability as diversity in higher education: Policies and practices to enhance student success. New York: Routledge.

Kimball, E. W., Wells, R. S., Ostiguy, B. J., Manly, C. A., & Lauterbach, A. A. (2016). Students with disabilities in higher education: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. Switzerland: Springer.

Kuh, G. D. (2007). What student engagement data tell us about college readiness. Peer Review, 9(1), 4–8.

Leake, D. (2015). Problematic data on how many students in postsecondary education have a disability. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(1), 73–87.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Gore, P. A., Jr. (1997). Discriminant and predictive validity of academic self-concept, academic self-efficacy, and mathematics-specific self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44(3), 307.

Lombardi, A. R., & Lalor, A. R. (2017). Faculty and administrator knowledge and attitudes regarding diversity. In E. Kim & K. C. Aquino (Eds.), Disability as diversity in higher education: Policies and practices to enhance student success. New York: Routledge.

Lombardi, A., Murray, C., & Dallas, B. (2013). University faculty attitudes toward disability and inclusive instruction: Comparing two institutions. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26(3), 221–232.

Lombardi, A. R., Murray, C., & Gerdes, H. (2012). Academic performance of first-generation college students with disabilities. Journal of College Student Development, 53(6), 811–826.

Madaus, J. W., Lalor, A. R., Gelbar, N., & Kowitt, J. (2014). The journal of postsecondary education and disability: From past to present. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(4), 347–356.

Mamiseishvili, K., & Koch, L. C. (2011). First-to-second-year persistence of students with disabilities in postsecondary institutions in the United States. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 54(2), 93–105.

Marsh, H. W., & Seaton, M. (2012). Academic self-concept. In J. Hattie & E. Anderman (Eds) International guide to student achievement. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Martz, E. (2003). Invisibility of disability and work experience as predictors of employment among community college students with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 18(3), 153–161.

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., Bowman, N. A., Seifert, T. A., Wolniak, G. C., & Pascarella, E. T. (2016). How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works (Vol. 3). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Murray, C., Flannery, B. K., & Wren, C. (2008). University staff members' attitudes and knowledge about learning disabilities and disability support services. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 21(2), 73–90.

Murray, C., Lombardi, A., & Kosty, D. (2014). Profiling adjustment among postsecondary students with disabilities: A person-centered approach. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(1), 31.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). Children 3 to 21 years old served under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B, by age group and sex, race/ethnicity, and type of disability: 2017–18 (Table 204.50). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_204.50.asp

Newman, L. A., & Madaus, J. W. (2015). Reported accommodations and supports provided to secondary and postsecondary students with disabilities: National perspective. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 38(3), 173–181.

O’Neil Green, D., Willis, H., Green, M. D., & Beckman, S. (2017). Access Ryerson: Promoting disability as diversity. In E. Kim & K. C. Aquino (Eds.), Disability as diversity in higher education: Policies and practices to enhance student success. New York: Routledge.

Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability and Society, 28(7), 1024–1026.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research (Vol. 2). Indianapolis, IN: Jossey-Bass.

Peña, E. V. (2014). Marginalization of published scholarship on students with disabilities in higher education journals. Journal of College Student Development, 55(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2014.0006.

Prince, A. M., Hodge, J., Bridges, W. C., & Katsiyannis, A. (2018). Predictors of postschool education/training and employment outcomes for youth with disabilities. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 41(2), 77–87.

Quinlan, M. M., Bates, B. R., & Angell, M. E. (2012). ‘What can I do to help?’: Postsecondary students with learning disabilities' perceptions of instructors' classroom accommodations. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 12(4), 224–233.

Raines, J. B., & Rossow, L. F. (1994). The Americans with Disabilities Act: Resolving the separate-but-equal problem in colleges and universities. West's Education Law Quarterly, 3(2), 308–18. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ483372

Raue, K., & Lewis, L. (2011). Students with disabilities at degree-granting postsecondary institutions. (No. NCES 2011–018). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011018.pdf

Rojewski, J. W., Lee, I. H., & Gregg, N. (2013). Causal effects of inclusion on postsecondary education outcomes of individuals with high-incidence disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 25(4), 210–219.

Ryan, S., & Runswick-Cole, K. (2008). Repositioning mothers: Mothers, disabled children and disability studies. Disability & Society, 23(3), 199–210.

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Pubic Law No. 93–112, 87 Stat. 394, (1973).

Scott, S. (2019). Access and participation in higher education: Perspectives of college students with disabilities. NCCSD Research Brief, 2(2). Huntersville, NC: National Center for College Students with Disabilities, Association on Higher Education and Disability.https://www.NCCSDclearinghouse.org

Shakespeare, T. (2014). Disability rights and wrongs revisited (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Shallish, L. (2017). A different diversity? Challenging the exclusion of disability studies from higher education research and practice. In E. Kim & K. C. Aquino (Eds.), Disability as diversity in higher education: Policies and practices to enhance student success. New York: Routledge.

Sniatecki, J. L., Perry, H. B., & Snell, L. H. (2015). Faculty attitudes and knowledge regarding college students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(3), 259–275.

Stevens, C. M., Schneider, E., & Bederman-Miller, P. (2018). Identifying faculty perceptions of awareness and preparedness relating to ADA compliance at a small, private college in NE PA. American Journal of Business Education, 11(2), 27–40.

Thomas, S. B. (2000). College students and disability law. The Journal of Special Education, 33(4), 248–258.

Thompson-Ebanks, V. (2014). Personal factors that influence the voluntary withdrawal of undergraduates with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(2), 195–207.

Troiano, P. F. (2003). College students and learning disability: Elements of self-style. Journal of College Student Development, 44(3), 404–419.

U.S. Department of Education (2015). Digest of Education Statistics, 2015. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 2016–014). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=60