Abstract

The heightened mobility of resources, ideas, and cultural practices across national borders—commonly known as “globalization”—entails changes in the contexts in which US research universities operate. We draw on recent developments in neo-institutional theory to understand these changes and their implications for the ways in which US universities compete for international doctoral students. Quantitative analyses of university-level data from 1990 to 2006 identify significant predictors of growth in this field, including state appropriations and state-supported research expenditures for public universities and net tuition receipts and number of full-time faculty members for private universities. We also highlight the ways in which returns have intensified, declined, or held relatively constant over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globalization processes have had a substantial effect on higher education around the world including in the United States (US) (Altbach 2011; Altbach and Knight 2007; Frank and Meyer 2007; King et al. 2011; Meyer and Schofer 2009; Pusser et al. 2012; Rhoads and Szelényi 2011; Rhoads and Torres 2006; Schofer and Meyer 2005; Slaughter and Leslie 1997; Szelényi and Rhoads 2007; Taylor et al. 2013). These processes have increased the extent and intensity of social and economic interconnections across the world (Held and McGrew 2007). As such, globalization has changed the conditions in which US universities operate.

One dimension of globalization is the rapid growth in international students enrolled in US universities. During the 2011–2012 academic year more than 750,000 international students enrolled in the US, an increase of five percent from the year before (Institute of International Education [IIE] 2012). Many of these students enrolled in graduate programs, and the number of PhDs earned by international students also has increased rapidly. Across all fields, more than 223,000 temporary residents earned doctorates from US universities between 1989 and 2009 (National Research Council 2012, Tables 2–11). Much, though by no means all, of this growth is concentrated in the sciences. Between 2000 and 2009, the number of science and engineering (S&E) doctorates earned by international students increased from slightly more than 8,000 per year to more than 13,500 (NRC 2012, Figs. 2–21).

The purpose of this paper is to understand growth and consolidation in the field of international doctoral education among US universities. We understand growth in the number of PhDs earned by international students as a consequence of environmental changes that reflect globalization processes. These processes denote changes in the worldwide channels through which universities pursue status (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a), resources (Slaughter and Cantwell 2012), and highly skilled labor (Cantwell and Taylor in press, 2013b; Stephan 2012). We contend that these processes entail changes for organizations and the individuals who work within them. In other words, we understand changes both in the operations of particular universities and in the field of international doctoral education as intimately related to processes of globalization.

Scholars of higher education often use neo-institutional theory to understand the ways in which US universities respond to environmental conditions (e.g., Bastedo and Bowman 2011, 2010; Bowman and Bastedo 2009, 2011; Hartley and Morphew 2008; Morphew 2002, 2009; Morphew and Hartley 2006; Morphew and Huisman 2002; Wilkins and Huisman 2012). The environment in which similar organizations are embedded is described as the institutional field. In this theoretical account, universities reflect the dominant norms and practices in their fields. We draw on three recent theoretical innovations within the neo-institutional tradition to frame our study. First, we employ the macrosociological work of John Meyer and colleagues (e.g., Meyer 2010, 2009; Meyer et al. 2006; Schofer and Meyer 2005), which contends that universities operate as nodes in a “world society” in which certain cultural forms exert increasing authority. This account explains growth and expansion of the field of international doctoral education, much like education enrollments generally (Meyer and Schofer 2009), as a dimension of globalization. Second, we consider the “microfoundations” of social institutions (Colyvas and Powell 2006; Powell and Colyvas 2008) as a means of specifying the motivations of individuals for recruiting and supporting international doctoral students. This perspective provides a theoretical account of individual-level demand for international doctoral students as a means of recruiting skilled workers for research projects. Finally, we draw on Fligstein and McAdam’s (2011, 2012) meso-level “theory of fields,” and especially their concept of “strategic action fields” (SAFs). Fligstein and McAdam highlight the ways in which fields change over time in response both to “macroevents” such as globalization and to micro-level strategic action undertaken by individuals nested within organizations. In this account, a rapidly growing field such as international doctoral education is dynamic, receptive to ideas and participants from other fields, and characterized by a fluid hierarchy. Over time, however, the field’s rules and hierarchy become more settled as the field consolidates.

Collectively, these distinct iterations of neo-institutional theory frame our analysis both of the ways in which the field of international doctoral education reflects globalization processes, and of the ways in which actors within US research universities respond to these environmental changes. We express these interests in the following research question:

-

1.

What university-level characteristics predict the number of PhDs earned by international students at a particular US research university?

Because neo-institutional approaches generally emphasize convergence of organizational forms and strategies over time, we also ask:

-

2.

How have the predictors of the number of PhDs earned by international students at US research universities changed over time?

Theory and Literature

Our theoretical approach casts universities as organizations that compete with one another in social fields. We define a “field” as a social space that contains agents who are engaged in a common activity, who compete with one another for resources, and who face similar opportunities and constraints (Fligstein and Dauter 2007). Unlike business firms for which profits and losses are the ultimate arbiters of success, finances are only one factor determining university status. Universities also compete for faculty, students, and a variety of other inputs (Weisbrod et al. 2008). The universities that regularly prevail in these competitions come to occupy a privileged position within a highly stratified field (Bastedo and Bowman 2010, 2011; Pusser and Marginson 2013; Winston 1999, 2004). This suggests that “success” in the field may have relatively little to do with economic efficiency (Fligstein 2001). Indeed, the universities considered to be the most successful, such as Dartmouth and Yale, are often among the most economically inefficient (Archibald and Feldman 2008). As a result, it is important to understand the broader social conditions in which both universities and their fields of activity are situated (Drori and Krücken 2009).

Globalization, Institutionalization, and “World Society”

Neo-institutional theory explains why status does not always reflect efficiency, and why organizations may come to reflect one another even when convergence does not improve performance. This account casts organizations as members of fields characterized by similar opportunities and constraints, and then identifies mechanisms of organizational change such as the flow of ideas, habits, and personnel within the field (DiMaggio and Powell 1983, 1991; Meyer and Rowan 1977). The dominant cultural practices of the field therefore shape individual-level decisions by informing both taken-for-granted norms and resource allocation patterns (Friedland and Alford 1991; Jepperson 1991; Jepperson and Meyer 1991). By extension, success reflects increased compliance with the conditions of the field rather than economically efficient operations (Fligstein 2001; Meyer et al. 1981).

John Meyer, a founder of the neo-institutional tradition, and his colleagues address globalization processes through the development of “world society” theory (Meyer 2010; Meyer et al. 2006; Schofer and Meyer 2005). This account, while “distinctively institutionalist” (Drori and Krücken 2009, p. 6), differs from its antecedents. Where many neo-institutional accounts place the cause of organizational change in field-level conditions (e.g., DiMaggio and Powell 1983), world society theory emphasizes the ways in which fields themselves have changed in response to globalization processes. This transformation generally follows a process of homogenization driven by cultural forms. The resulting fields reflect the logics of western civilization, a phenomenon seen in the emphasis on English-language publications in rankings of “global research universities” (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a). These profound changes result neither from individual choices nor from coercion, but from the expanding authority of social institutions and cognitive models across national borders (Drori and Krücken 2009; Meyer 2009).

Many recent studies in higher education suggest the merits of the world society account. In higher education, globalization has created transnational fields of competition (King et al. 2011; Marginson 2007). Global rankings systems allow universities to vie for status and resources (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a; Pusser and Marginson 2013, 2012). International doctoral students represent a second plane on which such competition could occur. Indeed, international student enrollments have risen steadily, and university competition for these students has increased notably (Altbach et al. 2009). Universities that aspire to be “world class” may compete for doctoral students on what is approaching a global basis.

One of the most salient indicators of the emergence and expansion of world society is the rapid diffusion of western science across national borders (Drori et al. 2009; Meyer and Schofer 2009). While undergraduate education remains nationally patterned (Marginson 2006), there is an emerging global field of advanced scientific training and research (Marginson 2014). Cross-national mobility is becoming normal among career PhD students and postdoctoral fellows (Franzoni et al. 2012). Publication data collected by the National Research Council (2012) show astonishing growth in the absolute number of “indexed” S&E papers produced in counties such as China, Brazil, and Turkey. The share of all papers that are co-authored by scientists working in different countries also has risen sharply. In short, advanced scientific training and research increasingly reflect a “one world” model (Marginson 2014).

On the organizational level, the global spread of science is embodied as an emphasis on S&E research. Global rankings such as the Shanghai Jiao Tong Academic Ranking of World Universities emphasize R&D outputs more heavily than instructional or service-related activities (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a; Pusser and Marginson 2013, 2012). Universities that are eager to improve their positions in various rankings, then, tend to emphasize research to the exclusion of other aspects of faculty work (Gonzales 2014, 2013). This implies that the growing numbers of international doctoral students may be related in part to the spread of science across national boundaries, and to the resources and status that universities pursue through S&E research.

Microfoundations and Demand

World society theory highlights the salience of changes in the macro environment. However, organizational and field changes do not simply happen, but are initiated by actors. Accordingly, recent neo-institutional theorists have given attention to the microfoundations of institutionalized fields, positing that new fields such as international doctoral education originate in individual-level action. In this “microfoundational” iteration of neo-institutional theory (Colyvas and Powell 2006; Powell and Colyvas 2008), individuals who work within organizations face new and complex problems that demand solutions. These individual responses reflect what Fligstein and McAdam (2012) term “social skills,” meaning “the ways in which skilled actors use empathy and the capacity to fashion and strategically deploy shared meanings and identities” (p. 53). If individuals’ responses to social problems appear to be correlated with organizational success, they are likely to be routinized as common responses to the set of conditions to which they respond (Colyvas and Powell 2006). In other words, what we perceive as organizational behavior is actually caused by individual-level actions.

Patterns in the enrollment and support of international doctoral students suggest that the micro-level source of demand for these students resides with faculty members. Whereas 23.7 % of domestic doctoral students in 2010 paid tuition to pursue graduate work, only 4.2 % of international doctoral students relied on their own funds. By contrast, in 2010, 92.3 % of international doctoral students were supported by institutional or external sources including teaching assistantships (21.7 %), research assistantships (49.8 %), and grants and fellowships (20.8 %) (NSF 2011). These figures suggest that most universities seek international doctoral students not as a source of tuition revenue, but as contributors to the research projects overseen by individual faculty members.

Increased enrollment of international doctoral students predicts an increase in the number of patent applications filed by US universities (Chellaraj et al. 2005). The relationship between international doctoral enrollments and patents may reflect the fact that these students are highly concentrated in the academic fields in which patenting activity is most intense (Fiegener 2010). International students now account for nearly 50 % of all PhD degrees awarded in S&E fields (Stephan 2012, p. 187). International doctoral students also appear to write more research papers than do their domestic counterparts (Corley and Sabharwal 2007), suggesting their overall value to academic R&D (Black and Stephan 2010). For their part, faculty members prefer to pursue students whom they believe will be more productive because outputs from funded projects are important indicators of the success of securing future funding (Stephan 2012). Thus, while growth in the field of doctoral education may originate in macrosocial conditions such as the emergence of world society, the mechanisms by which this growth occurs may be individual scientists.

Strategic Action Fields and Responses to Discontinuity

While the causal mechanism of organizational change resides on the individual level, we hasten to note that individuals’ actions tend to be geared toward securing resources and status from organizations and fields. “Social skill,” Fligstein and McAdam (2012) note, primarily reflects an individual’s ability to identify shared meanings, and to deploy these common understandings in the strategic pursuit of particular goals. The world society account offers an even stronger variation of this insight, contending that “actorhood” itself is a socially constructed category (Drori and Krücken 2009; Drori et al. 2009; Meyer 2009). Such an approach does not deny the primacy of individual agency, but does argue that the activities that individuals undertake and the manner in which others interpret these actions are deeply enmeshed with social conditions. As such, micro-level action may be causal, but cannot be understood without reference to social context.

World society theory offers a clear account of the origins and diffusion of the processes associated with globalization. An acknowledged limitation of this approach, however, is its relative lack of attention to specific national contexts, which are often assumed to be passive receptacles into which global norms diffuse (Drori and Krücken 2009). Indeed, Meyer and Schofer (2009) explicitly state that “focus on national-level factors …. will obviously not serve well to account for endemic worldwide growth” of higher education (p. 355). While acknowledging the important insights of this approach, we instead posit that universities are simultaneously global, national, and local entities (Marginson and Rhoades 2002). This suggests that field-level conditions are an important consideration for our analysis.

The field of US higher education changed dramatically during the 1990s and 2000s as direct state support waned, reliance on external revenues grew, and universities shifted employment away from traditional faculty roles and toward more flexible workforces (Ehrenberg 2012; Slaughter and Rhoades 2004; Taylor et al. 2013). These changes prove particularly salient for our study because of the ample evidence, cited above, that international doctoral students are closely related both to externally derived revenues and to the production of research outputs.

Given the salience of changing field-level conditions, we theorize the interaction between organizations and their environments using the SAF concept, which highlights the ways in which fields become destabilized, and then mature and move toward a new consolidation (Fligstein and McAdam 2012, 2011). This account contends that the actors within a field are arranged in a steep hierarchy. While fields generally prove durable, various forcesFootnote 1 may destabilize both hierarchies and the practices that legitimate them. Echoing the world society approach, Fligstein and McAdam (2011, 2012) posit that “macroevents” such as globalization processes may reposition actors, reallocate resources, and rewrite protocols. These events can dramatically alter hierarchies and practices within the field. Alternately, one field may collide with another, allowing activities in other fields to shape the SAF of international doctoral education. In the context of globalization, this implies that university decision-makers may strategically use resources secured nationally (e.g., federal research grants) or locally (e.g., state appropriations) to compete for international doctoral students (see Marginson and Rhoades 2002).

Summary of Theoretical Framework

We draw on three distinct strains of neo-institutional theory in order to understand the ways in which US universities compete for international doctoral students. From the world society approach, we understand US universities as responding to globalization by responding to dominant cultural practices such as the institutionalization of academic science, the heightened emphasis on research, and the enrollment of large numbers of international students. Microfoundational accounts provide a theoretical mechanism for explaining demand by conceptualizing patterns in the decisions of individual PIs. Finally, SAF explains the ways in which macro-level globalization processes and micro-level actors such as individual faculty members interact in complex fields of activity. Because these two phenomena meet at the level of the organization, we focus our quantitative analysis on the activities of US universities. This prompts our first research question.

-

1.

What university-level characteristics predict the number of PhDs earned by international students at a particular US research university?

Given that neo-institutional theory emphasizes organizational responses to environmental changes, we expect to see change over time in university behavior. This prompts our second research question.

-

2.

How have the predictors of the number of PhDs earned by international students at US research universities changed over time?

Methods

Data and Sample

We utilize data from three sources. First, NSF surveys, made public through the “WebCASPAR” portal, supply data on R&D expenditures (“NSF Survey of Research and Development Expenditures at Universities and Colleges”), S&E graduate students (“NSF-NIH Survey of Graduate Students and Postdocs in Science and Engineering”), and standardize data on doctoral degrees collected by the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) of the National Center for Education Statistics. Second, the Voluntary Support of Education, an annual survey conducted by the Council for Aid to Education (CAE), supplies information on universities’ total gifts and donations (hereafter, “gifts”) and endowment holdings. Finally, IPEDS provides figures for net tuition and fees, state appropriations, and the count of full-time faculty members.

These national datasets provide information about the population of US universities over time. However, our use of NSF data entails an important limitation. Multi-campus organizations such as Rutgers University and the University of Colorado occasionally report research expenditures to NSF as a system rather than as individual campuses. Such data are not compatible with IPEDS and CAE figures that report campus-level information (Jaquette and Parra 2014). However, NSF data provide the most consistent source of information on R&D expenditures and graduate students in S&E fields. These data are crucial to our analysis due to the close relationship between research funding (NSB 2012), R&D activities (Chellaraj et al. 2005; Corley and Sabharwal 2007; Stephan 2012), and international doctoral students. Because NSF data are both theoretically necessary and irreconcilable with other data sources, we have no basis from which to impute missing values. We therefore dropped institutions whose identifiers in the two data sets could not be reconciled. As a result, our sample broadly, though not exactly, parallels available data on the population of universities. We argue that the benefits of a better-specified model—that is, one including the range of variables that result in some missing values—exceed those of a less well-specified model that samples a greater number of observations. Nonetheless, we caution that results reflect only universities included in the sample.

With this exception, our sample includes all universities identified as “high research activity” or “very high research activity” by the Carnegie Classification of 2005. While many additional colleges and universities also confer doctorates, sampled universities conduct the highest levels of research of any group of higher education organizations in the US, and so in aggregate enroll the majority of doctoral students. Moreover, these are the organizations that are most closely associated with broad academic research enterprises, a substantively important sampling criterion given that international doctoral students are associated with increases in R&D productivity (Chellaraj et al. 2005; Corley and Sabharwal 2007; Stephan 2012). Finally, because our interest is a field of social activity rather than a process of academic production, it is particularly important to ensure that sampled cases are included in the field of international doctoral education. This narrower focus reduces the likelihood that our results reflect sample heterogeneity rather than quantitative relationships that extend and refine social theory.

Due to the deletions noted above, our sample includes 112 (of 126) public and 53 (of 59) private research universities. We observe these universities annually from 1990 through 2006. These years span the “era of globalization” in higher education (St. John et al. 2013), and so prove an appropriate temporal sample given our substantive interests.

Variable Selection

This paper conceptualizes international doctoral education as a field of social activity. Accordingly, we choose a dependent variable, PhDs earned by international students, that indicates a university’s level of activity in that field. While we believe that our dependent variable constitutes a reasonable proxy for a university’s success at recruiting and retaining international students, it is clearly not the only metric by which to measure activity in the field. A more complete analysis also would consider the number of international doctoral students applying to and enrolled at a particular university. Unfortunately, such data are not publicly available. A joint NSF-NIH “Survey of Graduate Students and Postdocs in Science and Engineering” reports the total number of international graduate students enrolled at a particular university in a given year, but neither distinguishes between masters and doctoral students nor includes students in fields outside of S&E. Accordingly, we view these data as less suitable than doctorates conferred for our analysis.

We predict the dependent variable with three broad categories of variables drawn from our theoretical framework. First, we consider variables that reflect the microfoundation of our theoretical model. In this account, faculty members seek international doctoral students as contributors to research projects. We include doctoral degrees earned by US citizens and permanent residents to account for the possibility that the size of one element of the doctoral enterprise may reflect the extent of another. We also consider a university’s emphasis in various fields of study. Science is closely associated with globalization in the world society account, and approximately 60 % of international doctoral students in the US enroll in S&E fields (NRC 2012). We therefore include the share of total PhDs conferred in S&E fields as a measure of a university’s S&E emphasis. Because the majority of doctoral students are supported by research grants (Stephan 2012), we also add measures of R&D support from many sources. We include funds for R&D derived from federal, state, and industry sources alongside an institution’s own contributions. Additionally, we include the count of full-time faculty members because international doctoral students often work on externally supported research projects (NSF 2012), which in turn are associated with the composition of a university’s faculty (Zhang and Ehrenberg 2010). Finally, we include the number of international students enrolled in graduate programs in S&E fields. While these data are not ideally suited to our area of interest—as noted previously—they nonetheless provide an important measure of a university’s overall efforts in the area of international graduate education. As such they are akin to, but by no means equivalent to, an “exposure” term in Poisson regression (Long 1997).

Second, we acknowledge that universities reap benefits—including “world-class” status (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a) and indirect cost recoveries (Stephan 2012)—from improved faculty research productivity. These benefits may incentivize campus decision-makers to prioritize activities in the field of international doctoral education, much as administrative decisions contributed to the birth of research commercialization as a field of academic activity (Colyvas and Powell 2006). Accordingly, we include several independent characteristics that are not proximate to the field of international doctoral education, but which might be reallocated by campus decision-makers into this field. We include net tuition and fees revenues for all sampled universities. We also add revenues from state appropriations for public universities, and endowment holdings and total annual donations for private universities. These variables allow us to explore the possibility of strategic participation in the field, in a manner consistent with the SAF concept (Fligstein and McAdam 2012).

Third, we include a group of variables that account for potential changes over time. “Time” can be operationalized as a variable in several different ways (Carter and Signorino 2010). A linear time trend is a variable in which the first year of the temporal sample is set equal to zero. Subsequent years raise the value of this measure by one. This approach offers the benefit of ready interpretation because the coefficient for the variable of interest represents the “main effect” in year zero, while the interaction term represents the amount that the main effect intensifies or wanes with each passing year. This benefit is offset, however, by a generous assumption about the scale of time’s importance. Because the measure grows from zero (in year one) to one (in year two), and so on, a linear time trend assumes that the effect of time during the 11th year of a sample (10) is 10 times as great as the effect of time during the second year (1). This assumption can grant an outsized explanatory role to time. To address this concern about variable scaling, we use a log-linear time trend. Here, we set the first year of our sample equal to year one, the second to year two, and so on. We then log the linear variable. This preserves the interpretive ease of having a “main effect” for the first year of the sample because the log of one is zero. However, the resulting curve is much less steep than in the linear time trend, meaning that the problem of scale is less acute with the log-linear measure. As we note when interpreting regression results, this approach yields predicted values of the dependent variable that are unlikely to fall outside the “convex hull” of observed values.

Because our theoretical approach highlights growth and consolidation over time, we also interact our independent variables with the log-linear time trend. Interaction terms allow us to chart movement within the field by highlighting the changing returns to various measures over time. Although we present both results that include only “main effects” (i.e., no temporal interaction variables) and those that include all measures, for reasons of space we limit ourselves to a discussion of the results from regressions that include all variables.

We transform variables in two ways. First, we control all finance figures for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”). Second, we log several variables. We log all counts, including the dependent variable, in order to minimize the influence of high-leverage outliers. We log finance figuresFootnote 2 to account for diminishing returns to scale, assuming that a university expends its first dollar differently than its kth dollar. We interpret results for logged variables as elasticities, meaning that coefficients represent the expected percent change in the dependent variable due to a 1 % change (rather than a one-unit change) in X (Gujarati 2003).

Analytic Strategy

The dependent variable in our analysis, the logged count of PhDs earned by international students, is a continuous measure that is appropriate for ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression. Because we observe universities annually from 1990 through 2006, our research questions require techniques that adapt OLS regression analysis for panel data that include multiple observations of a single university at different points in time. Cross-sectional regression can be inappropriate in such cases because it assumes that all cases are independent of one another (Zhang 2010). We address this concern through the inclusion of fixed university-level effects (“FE”) (Cameron and Trivedi 2010). We therefore interpret estimated results as “within-university” predictions, meaning that a change in X predicts a change in Y for a particular university rather than across the entire sample (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2012).

We also acknowledge that doctoral students require many years in order to complete their programs. A doctoral student’s average number of years to degree increased slowly from approximately 6.5 in the late 1970s to about 7.5 by 1998. The figure then held constant at this level through the end of the study period (Hoffer and Welch 2006). Accordingly, we lag all independent variables by 7 years.

Because our dataset contains multiple observations of the same universities over time, standard errors are likely to be biased by the structure of the data. Serial correlation, meaning the non-independence of one observation with preceding observations of the same university, is a common problem in such datasets (Angrist and Pischke, 2009). We use Drukker’s (2003) implementation of Wooldridge’s test, which indicates serial correlation could bias estimates in both public and private university subsamples (p < 0.01). Following Baum (2006), we also conduct robust tests for equality of variances among groups of universities. These tests significantly (p < 0.01) reject the hypothesis that groups were similar whether comparisons were made at the mean or the median. Based on these results, we followed other recent studies in higher education (e.g., Toutkoushian and Hillman 2012) and clustered standard errors by university.

Finally, we note that few private universities receive direct state appropriations (Desrochers and Wellman 2011). Accordingly, the inclusion of this variable for public universities requires that we conduct separate regression analyses of public and private subsamples. This approach is consistent with recent research (e.g., Desrochers and Wellman 2011; Ehrenberg 2012; Leslie et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2013) on the growing differences between public and private research universities.

Limitations

Our analysis faces an important limitation in the availability of suitable data. A more robust analysis would consider predictors of international doctoral applicants and enrollments, and not simply completions. Unfortunately, as noted previously, such data are not publicly available. Even within the analysis that we do conduct, we acknowledge the limitations of available data. For example, we are unable to include a measure of retention and completion as a predictor of the number of PhDs earned by international students. A measure is widely available for 2-year and 4-year undergraduate degree programs, but no comparable figure for completion among doctoral students is widely calculated and publicized.Footnote 3 We believe that the use of fixed university-level effects provides a helpful safeguard against this concern. Assuming that the relationship between enrollments and completions at any given university proves relatively stable over the study period—assuming, that is, that the effect of “being Harvard” or “being the University of Kentucky” on retention is approximately fixed, net of specified model characteristics—our results should not reflect a misspecified model. This assumption seems reasonable, but we acknowledge that no assumption provides a perfect safeguard against the lack of precise data.

A second limitation relates to the scope of our argument. Our theoretical model, coupled with our review of extant scholarship, indicates that international doctoral students are desirable as sources of prestige and research production for PIs and universities. Because universities are multi-product organizations (Leslie et al. 2012), however, this should not be taken to imply that international doctoral students are per se more important than other students or other fields of activity.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The average number of doctoral degrees earned by international students at sampled universities from 1990 through 2006 is presented in Fig. 1. This figure also reported the percentage of total doctorates earned by international students. Consideration of this measure allowed for the possibility that PhDs earned by international students increased as a function of growing graduate emphasis rather than as a response to globalization. The count of PhDs is indexed to the left-hand y-axis, while the percent of PhDs is indexed to the right-hand axis.

Although we analyzed public and private universities separately, the two lines tracked one another closely. This parallel suggested that the two groups of universities participated in the field of international doctoral education in approximately equal measure. Both subsamples witnessed a plateau in the number of doctorates earned by international students for approximately the first decade of our temporal sample. Both then entered a period of rapid growth in the late 1990s (privates) and early 2000s (publics). The percentage of PhDs earned by international students followed a similar pattern. This indicated that, on average, the number of PhDs earned by international students increased more rapidly than did the number earned by domestic students. This result suggested that growth in the number of PhDs earned by international students was not primarily a function of expanded emphasis on graduate education overall. Instead, these results implied that sampled universities expanded doctoral education for international students more rapidly than for domestic students.

Figure 2 reproduced Fig. 1, but for international students who are enrolled in graduate programs in S&E fields rather than for doctorates earned. As noted in our methods section, this variable is an imperfect measure for our purposes. Because our dependent variable is also an imperfect proxy, however, consideration of this alternate measure yielded a fuller portrait of the phenomenon of interest. Changes over time in this measure followed a similar pattern to those described for earned doctorates. Such a finding suggested that the patterns depicted in Fig. 1 did not simply represent an artifact of variable selection. Notably, however, the period of rapid growth began several years earlier for enrollments than it did for completions. The early growth period for international S&E graduate enrollments confirmed our strategy in two ways. First this indicated the appropriateness of using time lags in our regression models. Second, while the number of international students enrolled in S&E graduate programs is an acknowledged imperfect control variable, it was likely a suitable measure of student “inputs” who might earn PhDs.

Descriptive statistics for all variables included in our regression model are presented in Table 1. While this table proved useful for understanding the overall distribution of each of these variables, it ignored the temporal dimension of our panel dataset. As such, we disaggregated descriptive statistics for selected years in Table 2.

Descriptive figures indicated that, while sampled public and private universities may have participated in this field in approximately equal measures (see Fig. 1), the two subsamples differed in several important respects. Public universities, on average, were larger than their private counterparts, as measured by full-time faculty members employed. Private universities on average conferred a greater share of PhDs in S&E fields than did public universities. Moreover, the average private university drew more R&D support both from the federal government and from industry than did the average public university. Public universities, by contrast, on average drew more research funding from states and spent more of their own funds on R&D than did privates. Given both these notable differences and prior research indicating the different ways in which public and private universities secured and expended funds (e.g., Leslie et al. 2012), we conducted separate regression analyses based on institutional control.

Public Research Universities

Regression results for the public university subsample are presented in Table 3. As noted above, we discuss only results including main effects and interaction terms, but present a model that omits temporal interactions for reasons of transparency. Because interaction terms must be interpreted in the context of both of the elements of the interaction—in this case, an independent variable of interest and a time trend—the results of a series of F tests also are included in this table. These tests indicated whether the two variables were jointly significant, and so provided a better guide to interpretation than did p-values for individual coefficients.

State-supported R&D proved a significant and positive predictor of the number of PhDs earned by international students. Net of other factors, a 1 % increase in state-funded research expenditures in the first year of our temporal sample predicted a 0.11 % increase in the dependent variable 7 years later. As indicated by the interaction term, however, this relationship attenuated over time.

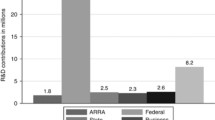

A graph of the declining returns to state-funded R&D over time is presented in Fig. 3. This figure summarized a series of predictions in which we set all variables equal to their observed values (including the fixed effects) excepting the time trend and its interaction with state-supported R&D. These predictions indicated that, absent variation in other characteristics, the declining return to state-supported R&D would have reduced the number of doctorates earned by international students by more than 50 % at 75th percentile and median universities. The decline for universities at the 25th percentile proved less steep, which is appropriate given the lower bound of zero degrees.

Institution-supported R&D also proved a significant predictor of PhDs earned by international students. All else equal, a 1 % increased in institution-funded research expenditures predicted a 0.02 % increase in the dependent variable. In contrast to the declining relationship between state-supported R&D and PhDs earned by international students, the estimated effect of institutional R&D appeared to intensify over time. However, this statistically significant relationship did not prove substantively meaningful. Predictions like those presented in Fig. 3, which we omit for reasons of space, traced three virtually flat lines. We therefore concluded that this measure attained statistical significance, but netted a constant return in practical terms.

While the relationship between institutionally funded R&D and the dependent variable appeared small, it is important to interpret the coefficient in the context of observed values. As reported in Table 1, sampled public universities on average drew a larger share of R&D support from institutional coffers than from the state. Moreover, as indicated in Table 2, sampled public universities made increasingly large contributions to R&D over time. This suggested that the driver of growth in the number of PhDs earned by international students was not an increasing return per dollar over time, but an increase in the number of discretionary dollars spent on research. Put more directly, the relationship between institutional R&D and PhDs earned by international students appeared to reflect the expanding scale of self-funded research rather than intensifying relationship between the two variables.

Further support for this contention may be found in the positive and intensifying relationship between state appropriations and the number of PhDs earned by international students. Net of other factors, a 1 % increase in state appropriations predicted a 0.5 % increase in the dependent variable. Further, as indicated by the temporal interaction term, this relationship grew stronger over the study period. Where institutional spending on research has increased notably over time, however, direct state support for sampled universities has declined nominally in constant dollars (see Table 2). This suggests that the emphasis on research generally has intensified in a way that has led to the reallocation of finite general funds toward R&D activities and graduate education.

Private Research Universities

Regression results for the private university subsample are presented in Table 4. As indicated in this table’s final column, net tuition receipts began the period as a negative predictor of the dependent variable, but reversed course over time. Net of other factors, a 1 % increase in net tuition income predicted a 0.31 % decrease in the dependent variable in the first year of our temporal sample. However, this relationship abated over time, becoming neutral between the seventh and eighth year and positive thereafter.

A second variable, the number of full-time faculty members, demonstrated the opposite relationship to the number of PhDs earned by international students. This measure proved a positive predictor early in the sample, but the relationship diminished over time. Net of other factors, a 1 % increase in the number of full-time faculty members predicted a 0.33 % increase in the dependent variable in the first year of our sample. The projected attenuation of this relationship is depicted in Fig. 4. Diminution for universities predicted to be near the 75th percentile or the median proved notable, with an anticipated decline of more than 50 % in PhDs earned by international students. The decline at the 25th percentile proved slightly flatter, in part because—as in Fig. 3 above—the dependent variable is lower-bounded by zero.

Discussion

This paper conceptualizes international competition for graduate students as one area in which universities have responded to an increasingly globalized environment. We draw on existing research and three variants of neo-institutional theory to frame our quantitative analyses. World society theory suggests that globalization prompts the institutionalization of academic science on a worldwide basis. As such, we would expect growing international student enrollments. We pair these insights with SAF theory, which posits that US universities will respond strategically to changing field conditions, and microfoundational neo-institutional theory, which casts the individual faculty member as the causal mechanism undergirding these strategic responses. Put succinctly, we understand PIs as seeking skilled apprentice researchers, and universities as securing status and resources via this individual-level mechanism, in response to globalization processes.

Our analysis confirms the results of many previous studies indicating that globalization processes (Meyer and Schofer 2009; Schofer and Meyer 2005), the institutionalization of academic science (Drori et al. 2009), and the spread of competition across national borders (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a) increasingly characterize US research universities. Table 1 indicates that, on average, public and private research universities in the US conferred more PhDs on international students by the end of the temporal sample (2006) than they had earlier in the study period. This growth in the number of PhDs earned by international students did not simply reflect the general expansion of graduate education during this period; the share of doctorates earned by international students also increased. Similar patterns emerged in Fig. 2 depiction of international S&E graduate student enrollments. Taken together, these descriptive results imply that global competition for doctoral students may have become both normalized and normative.

Neo-institutional theory, in its many variants, posits that organizational responses to environmental conditions converge over time. Regression analyses that employed temporal interaction terms charted the nature of this convergence. Sampled public universities, on average, relied more heavily on state-funded R&D early in the study period. As the return to these dollars waned over time, however, state appropriations began to play an increasingly prominent role. Institutional spending on R&D also contributed to growth in the dependent variable, although this heightened prominence reflected not an improved rate of return but the growing scale of institutional spending on research activities (see Table 2). For their part, private universities initially witnessed negative returns to net tuition receipts in 1990, only to see this relationship reverse itself over time. As the relationship between net tuition and the number of PhDs earned by international students increased, the return to the number of full-time faculty members—initially a positive relationship—attenuated, as depicted in Fig. 4.

Implications

While regression analyses unearthed avenues of convergence in keeping with the world society perspective, it is notable that the public and private university subsamples demonstrated distinct relationships. This suggests that, although globalization processes confront all US research universities, universities respond to these macro-level conditions from different positions and in different ways. Such an interpretation proves consistent with previous theoretical insights (e.g., Marginson and Rhoades 2002) indicating that universities remain rooted in national and local conditions. Among these conditions, institutional control appears to remain salient.

To that end, our paper contributes to a growing body of research (e.g., Ehrenberg et al. 2007; Leslie et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2013) indicating that private universities typically respond more quickly to market-like pressures that do their public counterparts. PhDs earned by international students at public universities prove closely associated with measures of the research enterprise. At private universities, by contrast, net tuition income—which is not intuitively related to the R&D enterprise—grows in importance over time. This result suggests that private university decision-makers enjoy greater latitude than do their public counterparts when responding to environmental conditions. Accordingly, as new fields emerge, private universities may be able to reallocate resources strategically in a manner that hastens participation and consolidates position relative to their public peers.

Cast in terms consistent with our theoretical framework, the relationship between tuition and fees revenue and doctoral degrees awarded to international students strongly suggests strategic action within universities wherein resources derived in one field of activity are drawn upon in order to bolster organizational position in another field of activity. Such strategic behavior may help to explain why US private universities, net of other factors, tend to achieve higher status in world rankings systems such as the ARWU league tables than do their public counterparts (Cantwell and Taylor 2013a). Private universities, it seems, increasingly prioritize global efforts. This emphasis on global-scale competition is also apparent in staffing patterns. PhDs earned by international students were once closely associated with full-time faculty members at private universities. However, this relationship attenuates over time, suggesting that, for private universities, global competition is not as closely associated with traditional academic roles (i.e., the full-time faculty member) as was once the case.

On balance, then, our analysis suggests that universities do not passively respond to the norms of a single field of activity, but instead actively compete in multiple fields. Private university decision-makers, in this account, sometimes draw resources from one field to buttress their competitive position in another. This supports recent research that casts universities as multi-purpose organizations that re-allocate resources internally (Leslie et al. 2012). It also extends such findings by showing that resources derived in fields that are primarily national or local may be repurposed for competition in global fields.

In this sense, at least, the influence of global-level competition proves sufficiently strong that it motivates the use of locally derived resources. This simultaneously highlights the merits and limitations of world society theory for our analysis. On the one hand, as suggested by Meyer and Schofer (2009), our results indicate that the contemporary university cannot be understood fully without explicit attention to globalization processes and the convergence of organizational forms in response to global competition. On the other hand, as implied in Fligstein and McAdam’s (2011, 2012) account of field competition, our results suggest that responses to these shared pressures may be informed by local differences and conditions. The resulting university landscape demands close attention because the interplay of global, national, and local conditions resists tidy generalizations.

Limitations and Future Research

Our methods section details several important limitations related to the quality of data used in this study. To these concerns, we add that our research design casts the organization as the unit of analysis. As a result, we can offer only theory-informed suggestions on the nature of within-organization processes. For instance, it may be that private university decision-makers earmark some “general fund” monies derived from tuition to support outstanding doctoral students across the university. Individual departments may employ a strategy of securing these fellowships by recruiting the “best and brightest” students in their field on a global basis. Alternatively, in the central reallocation of tuition and fee revenue, individual colleges or departments may simply choose to use part of their share in order to support international doctoral students. Only in-depth case study can identify the mechanisms by which resources are allocated from one field to another.

A second limitation is our reliance on microfoundational neo-institutional theory (Colyvas and Powell 2006) to posit individual-level causal mechanisms. These theoretical insights provide a plausible mechanism for demand in the form of PIs’ desire for skilled graduate students to work on research projects. This demand is well supported by relevant literature. At the same time, however, we acknowledge that this mechanism is conceptual rather than empirical. Much as previous work has done with postdoctoral researchers (e.g., Cantwell 2011), future research could focus on individual faculty members to highlight their strategies for attracting and supporting international doctoral students.

Broad environmental changes, such as globalization processes, affect all universities. However, field-level explanations cannot alone fully account for the often-heterogeneous ways in which universities respond to these changes. Because our subject of interest is university behavior, we also call for more detailed research on within-university processes. As Leslie et al. (2012) acknowledge, it is impossible to assess internal resource allocation from university-level data. As that paper also notes, however, the data that are available imply that such allocations typically happen in highly patterned ways, with decision-makers shifting funds toward activities likely to win prestige and resources. Future research could employ internal campus documentation or qualitative analysis to further illuminate this theme. Only then will the relationships between heightened competition, globalization, and within-university work be more fully understood.

Notes

Fligstein and McAdam (2011, 2012) posit a third mechanism by which fields may change. “Invasion,” such as an investment group’s hostile takeover of an industrial firm, can destabilize the field’s hierarchy by bringing new cultural practices and material resources into the field. Because such events are rare in a field dominated by public and nonprofit actors, we focus instead on macroevents and field collisions.

One minor exception to this rule is variables on which a university reports a value of $0. For example, several private universities indicate that they received $0 in state-supported R&D expenditures for a particular year. In these cases, we substitute $1 for $0 because the natural logarithm of zero is undefined. By contrast, the natural logarithm of one is zero, which accurately expresses the value of this variable for the case in question.

While the Council of Graduate Schools (2008) provides data on sector-wide averages, these data are neither disaggregated to the level of individual campuses nor available in a panel format that would facilitate their use in our analysis.

References

Altbach, P. G. (2011). The research university. Economic and Political Weekly, 46(16), 65–73.

Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2007). Higher education’s landscape of internationalization: Motivations and realities. In S. Krishna (Ed.), Internationalization of higher education: Perspectives and country experiences (pp. 13–17). Hyderabad: IFCAI University Press.

Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., & Rumbley, L. E. (2009). Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. Paris, France: UNESCO.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Archibald, R. B., & Feldman, D. H. (2008). Graduation rates and accountability: Regressions versus production frontiers. Research in Higher Education, 49(1), 80–100.

Bastedo, M. N., & Bowman, N. A. (2010). US News & World Report College rankings: Modeling institutional effects on organizational reputation. American Journal of Education, 116(2), 163–183.

Bastedo, M. N., & Bowman, N. A. (2011). College rankings as an interorganizational dependency: Establishing the foundation for strategic and institutional accounts. Research in Higher Education, 52(1), 3–23.

Baum, C. F. (2006). Stata tip 38: Testing for groupwise heteroskedasticity. The Stata Journal, 6(4), 590–592.

Black, G. C., & Stephan, P. E. (2010). The economics of university science and the role of foreign graduate students and postdoctoral scholars. In C. T. Clotfelter (Ed.), American universities in a global market (pp. 129–161). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bowman, N. A., & Bastedo, M. N. (2009). Getting on the front page: Organizational reputation, status signals, and the impact of U.S. News and World Report on student decisions. Research in Higher Education, 50(5), 415–436.

Bowman, N. A., & Bastedo, M. N. (2011). Anchoring effects in world university rankings: Exploring biases in reputation scores. Higher Education, 61(4), 431–444.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconometrics using Stata. College Station: Stata Press.

Cantwell, B. (2011). Transnational mobility and international academic employment: Gatekeeping in an academic competition arena. Minerva, 49(4), 425–445.

Cantwell, B., & Taylor, B. J. (in press). The rise of the postdoctorate and the restructuring of academic research. The Journal of Higher Education.

Cantwell, B., & Taylor, B. J. (2013a). Global status, inter-institutional stratification, and organizational segmentation: A time-dynamic Tobit analysis of ARWU position among US universities. Minerva, 51(2), 195–223.

Cantwell, B., & Taylor, B. J. (2013b). A demand-side approach to the employment of international postdocs in the US. Higher Education, 66(5), 551–567.

Carter, D. B., & Signorino, C. S. (2010). Back to the future: Modeling time dependence in binary data. Political Analysis, 18, 271–292.

Chellaraj, G., Maskus, K. E., & Mattoo, A. (2005). The contribution of skilled immigration and international graduate students to US innovation. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (3588).

Colyvas, J. A., & Powell, W. W. (2006). Roads to institutionalization: The remaking of boundaries between public and private science. Research in Organizational Behavior, 27, 305–353.

Corley, E. A., & Sabharwal, M. (2007). Foreign-born academic scientists and engineers: producing more and getting less than their U.S.-born peers? Research in Higher Education, 48(8), 909–940.

Council of Graduate Schools. (2008). Ph.D. completion and attrition: Analysis of baseline program data. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Desrochers, D. M., & Wellman, J. V. (2011). Trends in college spending, 1999–2009. Washington, DC: Delta Cost Project.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The ‘iron cage’ revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 1–40). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Drori, G. S., & Krücken, G. (2009). World society: A theory and a research program in context. In G. S. Drori & G. Krücken (Eds.), World society: The writings of John W. Meyer (pp. 3–35). New York: Oxford University Press.

Drori, G. S., Meyer, J. W., Ramirez, F. O., & Schofer, E. (2009). World society and the authority and empowerment of science. In G. Krücken & G. S. Drori (Eds.), World society: The writings of John W. Meyer (pp. 261–279). New York: Oxford University Press.

Drukker, D. (2003). Testing for serial correlation in linear panel-data models. The Stata Journal, 3, 168–177.

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2012). American higher education in transition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(1), 193–216.

Ehrenberg, R. G., Rizzo, M. J., & Jakubson, J. H. (2007). Who bears the growing cost of science at universities? In P. Stephan & R. G. Ehrenberg (Eds.), Science and the university (pp. 19–35). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Fiegener, M. K. (2010). Numbers of doctorates awarded continue to grow (NSF 11-305). Washington, DC: NSF.

Fligstein, N. (2001). The architecture of markets. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fligstein, N., & Dauter, L. (2007). The sociology of markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 105–128.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2011). Toward a general theory of strategic action fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1–26.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Frank, D. J., & Meyer, J. W. (2007). University expansion and the knowledge society. Theory and Society, 36(4), 287–311.

Franzoni, C., Scellato, G., & Stephan, P. (2012). Foreign-born scientists: Mobility patterns for 16 countries. Nature Biotechnology, 30, 1250–1253.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. A. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). Chicago: University of Chicago.

Gonzales, L. D. (2013). Faculty sensemaking and mission creep: Interrogating institutionalized ways of knowing and doing legitimacy. The Review of Higher Education, 36(2), 179–210.

Gonzales, L. D. (2014). Framing faculty agency inside striving universities: An application of Bourdieu’s theory of practice. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(2), 193–218.

Gujarati, D. (2003). Basic econometrics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hartley, M., & Morphew, C. C. (2008). What’s being sold and to what end? A content analysis of college viewbooks. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(6), 671–691.

Held, D., & McGrew, A. (2007). Globalizatoin/anti-globalization: beyond the great divide (2nd ed.). London: Polity Press.

Hoffer, T. B., & Welch, V. (2006). Time to degree of US research doctorate recipients. National Science Foundation, Directorate for Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences (InfoBrief 312). Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Institute of International Education. (2012). Open doors, 2011. Retrieved from: http://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors.

Jaquette, O., & Parra, E. E. (2014). Using IPEDS for panel analyses: Core concepts, data challenges, and empirical applications. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 29, pp. 467–533). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Jepperson, R. L. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects, and institutionalism. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 143–163). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jepperson, R. L., & Meyer, J. W. (1991). The public order and the construction of formal organizations. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 204–231). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

King, R., Marginson, S., & Naidoo, R. (2011). Handbook on globalization and higher education. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Leslie, L. L., Slaughter, S., Taylor, B. J., & Zhang, L. (2012). How do revenue variations affect expenditures within research universities? Research in Higher Education, 53(6), 614–639.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. San Francisco: Sage.

Marginson, S. (2006). Dynamics of national and global competition in higher education. Higher Education, 52(1), 1–39.

Marginson, S. (2007). Global position and position taking: The case of Australia. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(1), 5–32.

Marginson, S. (2014). The global construction of higher education reform. In K. Mundy, A. Green, R. Lingard, & A. Verger (Eds.), (forthcoming) Global Policy and Policy-Making in Education. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

Marginson, S., & Rhoades, G. (2002). Beyond national states, markets, and systems of higher education: A glonacal agency perspective. Higher Education, 43(3), 281–309.

Meyer, J. W. (2009). The European Union and the globalization of culture. In G. Krücken & G. S. Drori (Eds.), World society: The writings of John W. Meyer (pp. 344–354). New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, J. W. (2010). World society, institutional theories, and the actor. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 1–20.

Meyer, J. W., Ramirez, F. O., Frank, D. J., & Schofer, E. (2006). Higher education as an institution. Palo Alto: Center on Democracy, Development and Rule of Law working paper, #57, Stanford University.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Meyer, J. W., & Schofer, E. (2009). The university in Europe and the world: Twentieth century expansion. In G. S. Drori & G. Krücken (Eds.), World society: The writings of John W. Meyer (pp. 355–372). New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, J. W., Scott, R. W., & Deal, T. E. (1981). Institutional and technical sources of organizational structure: Explaining the structure of educational organizations. In H. D. Stein (Ed.), Organization and the human services (pp. 45–67). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Morphew, C. C. (2002). A rose by any other name: Which colleges became universities. The Review of Higher Education, 25(2), 207–224.

Morphew, C. C. (2009). Conceptualizing change in the institutional diversity of U.S. colleges and universities. Journal of Higher Education, 80(3), 243–269.

Morphew, C. C., & Hartley, M. (2006). Mission statements: A thematic analysis of rhetoric across institutional type. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(3), 456–471.

Morphew, C. C., & Huisman, J. (2002). Using institutional theory to reframe research on academic drift. Higher Education in Europe, 27(4), 491–506.

National Research Council. (2012). Science and engineering indicators. Washington, DC: NSF.

National Science Foundation. (2011). Table 35. Doctorate recipients’ primary source of financial support, by broad field of study, sex, citizenship, and race/ethnicity: 2010. Survey of Earned Doctorates. Washington, DC: NSF.

Powell, W. W., & Colyvas, J. A. (2008). Microfoundations of institutional theory. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 276–298). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pusser, B., Kempner, K., Marginson, S., & Ordorika, I. (2012). Introduction and Overview. In B. Pusser, K. Kempner, S. Marginson, & I. Ordorika (Eds.), Universities and the public sphere: Knowledge creation and state building in the era of globalization (pp. 1–25). New York: Routledge.

Pusser, B., & Marginson, S. (2012). The elephant in the room: Power, politics, and global rankings in higher education. In M. Bastedo (Ed.), The organization of higher education (pp. 86–118). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Pusser, B., & Marginson, S. (2013). University rankings in critical perspective. Journal of Higher Eduation, 84(4), 544–568.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata. College Station: Stata Press.

Rhoads, R. A., & Szelényi, K. (2011). Global citizenship and the university: Advancing social life and relations in an interdependent world. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Rhoads, R. A., & Torres, C. A. (2006). The university, state, and market: The political economy of globalization in the Americas. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Schofer, E., & Meyer, J. W. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 70(6), 898–920.

Slaughter, S., & Cantwell, B. (2012). Transatlantic moves to the market: The United States and the European Union. Higher Education, 63(5), 583–606.

Slaughter, S., & Leslie, L. (1997). Academic capitalism. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

St. John, E. P., Daun-Barnett, N., & Moronski-Chapman, K. M. (2013). Public policy and higher education. New York: Routledge.

Stephan, P. (2012). How economics shapes science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Szelényi, K., & Rhoads, R. A. (2007). Citizenship in a global context: The perspectives of international graduate students in the United States. Comparative Education Review, 51(1), 25–47.

Taylor, B. J., Cantwell, B., & Slaughter, S. (2013a). Quasi-markets in US higher education: Humanities emphasis and institutional revenues. Journal of Higher Education, 84(5), 675–707.

Taylor, B. J., Webber, K. L., & Jacobs, G. J. (2013b). Internationalization, growth, and competition: The role of institutional researchers. In A. Calderone & K. L. Webber (Eds.), New directions for institutional research issue, 157 (pp. 5–22). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Toutkoushian, R. K., & Hillman, N. (2012). The impact of state appropriations and grants on access to higher education and outmigration. The Review of Higher Education, 36(1), 51–90.

Weisbrod, B. A., Ballou, J. P., & Asch, E. D. (2008). Mission and money: Understanding the university. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilkins, S., & Huisman, J. (2012). The international branch campus as transnational strategy in higher education. Higher Education, 64(5), 627–645.

Winston, G. C. (1999). Subsidies, hierarchy and peers: The awkward economics of higher education. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(1), 13–36.

Winston, G. C. (2004). Differentiation among U.S. colleges and universities. Review of Industrial Organization, 24(4), 331–354.

Zhang, L. (2010). The use of panel data methods in higher education policy studies. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, 25 (pp. 309–347). New York: Springer.

Zhang, L., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (2010). Faculty employment and R&D expenditures at research universities. Economics of Education Review, 29(3), 329–337.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Grant from the American Educational Research Association which receives funds for its “AERA Grants Program” from the National Science Foundation under NSF Grant #DRL-0941014. Opinions reflect those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies. The authors also thank Sondra Barringer for her invaluable assistance with IPEDS data, and Jim Hearn and two anonymous reviewers for their astute comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, B.J., Cantwell, B. Global Competition, US Research Universities, and International Doctoral Education: Growth and Consolidation of an Organizational Field. Res High Educ 56, 411–441 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9355-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9355-6